Abstract

Objectives

Total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) is a viable treatment for elderly patients with distal humerus fracture who frequently present with low grade open fractures. This purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of a protocol of serial I&D’s followed by primary TEA for the treatment of open intraarticular distal humerus fractures.

Methods

Seven patients (mean 74 years (range 56 – 86 years) with open (2 Grade I, 5 Grade 2) distal humerus fractures (OTA 13C) were treated between 2001 and 2007 with a standard staged protocol that included TEA were studied. Baseline DASH scores were obtained during the initial hospitalization, 6 and 12 month follow-up visits. Elbow ROM measurements were obtained at each follow-up visit.

Results

Follow-up averaged 43 (range 4–138) months. There were no wound complications and no deep infections. Complications included one case of heterotopic ossification with joint contracture, one olecranon fracture unrelated to the TEA, and two loose humeral stems. Average final ROM was from 21° (range 5°–30°) to 113° flexion (range 90°–130°). DASH scores averaged 25 at pre-injury baseline and 48 at the most recent follow-up visits.

Conclusions

TEA has become a mainstream option for the treatment of distal humerus fractures which are on occasion open. There is hesitation in using arthroplasty in an open fracture setting due to potential increased infection risk. The absence of any infectious complications and satisfactory functional outcomes observed in the current series indicates that TEA is a viable treatment modality for complex open fractures of the distal humerus.

Keywords: Trauma, Total Elbow Arthroplasty, Distal Humerus Fracture, Infection, Geriatric Trauma

Introduction

Total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) has become a viable treatment alternative for elderly patients with distal humerus fractures. Initially indicated for end stage arthritis of the elbow, the indications have expanded to include complex fractures of the distal humerus.1 Multiple previous studies have shown that TEA has equivalent or improved outcomes compared with open reduction and internal fixation for these fractures in select patient populations.2,3 Elbow arthroplasty after fracture is made more complicated by the fact that these patients, often elderly, may have very poor soft tissue coverage around the elbow, “paper-thin” skin, and not infrequently present with low-grade open fractures. In open fracture situations, theoretically, TEA has an increased risk of wound and deep infectious complications.4 Previous studies of TEA for fracture have included patients with low-grade open fractures, but to our knowledge no studies have evaluated infectious outcomes exclusively in patients with open fractures.1

Unlike distal humerus fractures, open fractures of the hip and proximal humerus are rare, yielding exceedingly little evidence for the safety of performing an arthroplasty in the setting of open fracture. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of a protocol of debridement followed by primary TEA for the treatment of open intraarticular distal humerus fractures in elderly patients.

Materials & Methods

Patients

A retrospective analysis was performed on eight patients with open distal humerus fractures who were treated between 2001 and 2009 with total elbow replacement (Figure 1). Total elbow arthroplasty was considered for physiologically elderly patients that also had fractures with articular comminution, poor bone quality such that stable fixation was compromised, or pre-existing elbow arthritis. One patient was head injured and lost to follow-up leaving a study group of two men and five women with a mean age of 74 years (range 56 – 86 years). All patients were older than 70 years of age except one 56 year old male who had TEA indicated for his fracture because of associated joint arthrosis from rheumatoid arthritis. The majority of patients (five) were injured in ground level falls, two were involved in motorcycle accidents and one had an approximate 12 foot fall from a ladder (Table 1).

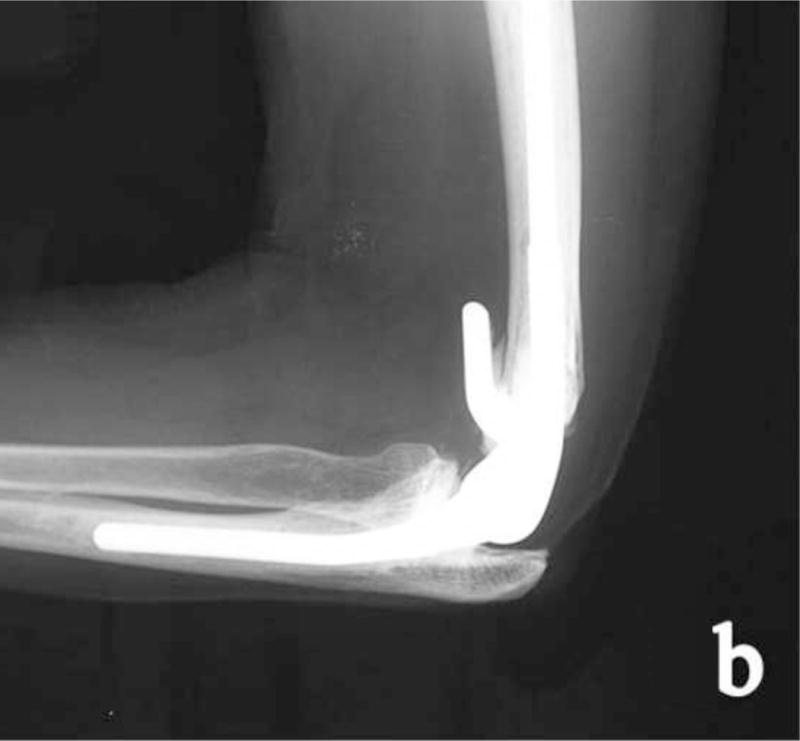

Figure 1.

Injury Radiographs depicting an interarticular distal humerus fracture, AP (a) and Lateral (b)

Table 1.

Demographic information on study patients

| Patient Age (Gender) | PMH | Mechanism | Number of I&D’s | Time from injury to TEA (Days) | Open Fracture Grade (Gustillo) | Follow Up (Months) | Complications | ROM at last FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86 M | Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia | Same Level Fall | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | None | 10–100 |

| 77 F | Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, hypothyroid | Same Level Fall | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | None | 10–125 |

| 76 F | Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, Macular Degeneration | Same Level Fall | 1 | 3 | 1 | 138 | Loosening, bushing wear at 11 years | 5–120 |

| 71 F | None | Motor Cycle Accident | 1 | 19 | 2 | 10 | Heterotopic Ossification | 30–130* (after contracture release) |

| 78 F | Hyperlipidemia, Osteoporosis | Same Level Fall | 1 | 2 | 2 | 121 | Olecranon Fx | 30–115 |

| 85 F | Hypertension, Atrial Fibrillation, Osteoporosis | Same Level Fall | 1 | 9 | 2 | 4 | Heterotopic Ossification | 30–90 |

| 56 M | Rheumatoid Arthritis, Hypertension, Previous Smoker | Ladder fall | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | Mild Heterotopic Ossification, loose at 1.5 years | 20–100 |

Fractures

The open fractures were classified with the Gustilo-Anderson system with 2 Grade I and 5 Grade II fractures.5 Radiographically, all distal humerus fractures were classified as 13C utilizing the OTA/AO system.6 The decision for treatment with total elbow arthroplasty was based on the perception that the degree of articular comminution or the bone quality would not allow for primary open reduction and internal fixation.

Treatment

All patients were treated with a standard protocol that included TEA (Coonrad-Morrey, Zimmer, Warsaw, IN). The protocol included emergent operative irrigation and debridement (I&D) upon presentation followed by repeat I&D and TEA when the wounds were stable. A previously described and standard operative technique for prosthesis implantation was followed (Figure 2).7

Figure 2.

Postoperative Radiographs after Total Elbow Arthroplasty, AP (a) and Lateral (b)

The average time from fracture until TEA was 6 days (range 2–19). Two patients with Grade II open fracture underwent I&D, definitive wound closure, hospital discharge and semi-elective TEA at 9 and 19 days after fracture, respectively. The other five patients had TEA within 4 days of injury during their index hospital admission. The timing for definitive internal fixation after low grade open fracture is generally immediate or within several days. The decision to perform total elbow arthroplasty followed this same rationale in the majority of cases. Open fractures were treated urgently with irrigation and debridement. Short delays to total elbow arthroplasty were primarily related to availability of surgeons experienced with total elbow arthroplasty. Longer delays in two patients were related to other logistical issues. For the two patients with semi-elective TEA, antibiotics were administered upon presentation and continued until 48 hours after wound closure. They also had peri-operative antibiotics surrounding their TEA (pre-op and continued 24 hours post-op). The other five patients had antibiotics administered upon presentation and continued until 48 hours after TEA. Elbows were splinted for 1 – 2 weeks after TEA to facilitate wound healing then physical therapy was initiated for ROM and strengthening.

Follow-up and Outcomes

Patients were evaluated with routine postoperative follow-up for an average of 43 (range 4–138) months. Baseline (pre-injury) functional outcome scores (DASH) were obtained during the initial hospitalization and again at the 6 and 12 month follow-up visits. Elbow ROM measurements were obtained at each follow-up visit. Complications, particularly infections, were extracted from the medical record.

Results

There were no wound complications and no deep infections. Other complications included one case of heterotopic ossification with joint contracture, one olecranon fracture and two loose humeral stems identified in long term follow up. The olecranon fracture occurred after a secondary fall, was minimally displaced and was successfully treated non-operatively. The patient with a contracture required formal operative capsular release. The first patient with a loose stem had rheumatoid arthritis and underwent successful revision arthroplasty at 2.5 years after index TEA. There was no evidence of infection on pre-operative labs and from intra-operative cultures. The patient had a well-functioning prosthesis at final follow-up 3 years after revision. The second presented at 11.5 years post-op with complaints of arm pain, had loosening diagnosed with radiographs, but was not revised due to patient preference. The average elbow range of motion at the most recent post-operative evaluation was 21° short of full extension (range 5°–30°) to 113° flexion (range 90°–130°). The average arc of motion was therefore 92°. DASH outcome scores averaged 25 at pre-injury baseline and 48 at the most recent follow-up visits.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of a protocol of debridement followed by primary TEA for the treatment of open intraarticular distal humerus fractures in elderly patients. In elderly patients with complex distal humerus fractures, TEA may be the best surgical option, however there may be hesitation in using arthroplasty in an open fracture setting due to potential increased infection risk. The high historical incidence of infection seen in elective TEA performed for joint arthropathy can be attributed to populations that were nearly one half patients with rheumatoid arthritis. These patients frequently are taking medications that increase their susceptibility to infection.8 In the current study, no infections occurred after open fracture debridement followed by TEA. The lack of infections seen in the present study is consistent with other studies that included smaller groups of patients with open fractures. McKee reported three open fractures in their study comparing open reduction with internal fixation of distal humeral fractures vs total elbow arthroplasty. They did not comment on complications specifically relating to the open fracture patients and only noted two infections in a total of 25 total elbow replacements.1 In a study by Cobb and Morrey, two of twenty one patients were noted to have low grade open fractures, but no open fracture specific complications were noted. There was only one superficial wound infection in the twenty one patients and it was not noted if this was in an open fracture case.7

In addition to lack of infectious complications, functional outcomes also determine whether a treatment is successful. The range of motion seen post-operatively in this study is comparable to similar patients with total elbow arthroplasty performed for closed fractures. While multiple studies have examined the outcomes of TEA following distal humeral fracture (Table 1), they have included few patients with open fractures. The average range of motion, complication rates and revision numbers seen in the current study are also similar to previously published data. Cobb and Morrey reported an average range of motion of 105 degrees, a 25% rate of complications and 5% rate of revisions with an average follow up of 3.3 years.7

There are limitations to the present study that should be considered. The small sample size may make identification of less common complications difficult and may make identification of common complications problematic. Past the initial healing phase, complications commonly seen with TEA include triceps insufficiency and late loosening.7 The rate of triceps in sufficiency is quite low and the size of our patient group may have limited our ability to observe this complication9. Humeral stem loosening is relatively rare with less than 10% seen at 25 year followup, which made the observed rate of loosening higher than reported in the literature. While our average followup was quite long, two patients, who followed up over ten years after their initial surgery, skewed the average. Without universal long term follow up, late implant failure is still a possibility upon further follow up.

Further studies with larger numbers of patients would help to identify both late complications and more rare complications. While no infections were noted in the patients that had late loosening, particular attention should be paid to ensure that implant failure is not due to infection.

The current study indicates that total elbow arthroplasty should not be considered contra-indicated for elderly patients with an open distal humerus fracture. The absence of any infectious complications and satisfactory functional outcomes observed in the current series indicates that TEA is a viable treatment modality for open fractures of the distal humerus.

Table 2.

| Study | # TEA | Mean Age | Fracture Type | Follow up | ROM (degrees) | Complications | Revisions | Open Fractures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobb and Morrey | 21 (20 pts) | 72 | B1 (2), B2 (5), C2 (5), C3 (6) | 3.3 (range, 3 mo–10 y) | 105 | 5 (25%) | 1 (5%) | 2 |

| Ray et al | 7 | 81.7 | C2 (1), C3 (3) | 2.7 | 110 | 1(14%) | 0 | 0 |

| Gambirasio et al | 10 | 84.6 | B (2), C (8) | 1.5 | 102 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Garcia et al | 16 | 73 | A3 (2), B3 (2), C3 (11) | 3 | 101 | 2(13%) | 0 | 0 |

| Kamineni and Morrey | 49 | 69 | A (6), B (5), C (38) | 7 | 107 | 14 (29%) | 10 (23%) | 0 |

| Lee et al | 7 | 73 | A (4), B (1), C (2) | 2.1 | 89 | 1 (14%) | 0 | 0 |

| McKee et al | 25 | 78 | C1 (6), C2 (2), C3 (12) | 2 | 120 | 18 (72%) | 3 (12%) | 3 |

| Ali et al | 26 | 72 | A3 (1), B2 (1), B3 (4), C3 (14) | 5 | 98 | 5 (19%) | 0 | 0 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McKee MD, Veillette CJ, Hall JA, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial of open reduction-internal fixation versus total elbow arthroplasty for displaced intra-articular distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery/American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2009;18:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamineni S, Morrey BF. Distal Humeral Fractures Treated with Noncustom Total Elbow Replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:940–7. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalidis B, Dimitriou C, Papadopoulos P, Petsatodis G, Giannoudis PV. Total elbow arthroplasty for the treatment of insufficient distal humeral fractures. A retrospective clinical study and review of the literature. Injury. 2009;40:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehlhoff TL, Bennett JB. Distal humeral fractures: fixation versus arthroplasty. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2011;20:S97–S106. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. The Journal of trauma. 1984;24:742–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schaftzken J. Comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. New York: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobb TK, Morrey BF. Total Elbow Arthroplasty as Primary Treatment for Distal Humeral Fractures in Elderly Patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79-A:826–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF. Total Elbow Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:121–5. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201102000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg SH, Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, King GJ, O’Driscoll SW, Cohen MS. Modes of wear after semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:609–19. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KT, Lai CH, Singh S. Results of total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of distal humerus fractures in elderly Asian patients. The Journal of trauma. 2006;61:889–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000215421.77665.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamineni S, Morrey BF. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2004;86–a:940–7. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia JA, Mykula R, Stanley D. Complex fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. The role of total elbow replacement as primary treatment. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2002;84:812–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b6.12911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gambirasio R, Riand N, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P. Total elbow replacement for complex fractures of the distal humerus. An option for the elderly patient. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2001;83:974–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b7.11867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray PS, Kakarlapudi K, Rajsekhar C, Bhamra MS. Total elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. Injury. 2000;31:687–92. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobb TK, Morrey BF. Total elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1997;79:826–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]