Abstract

Genetic variants of whole mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that predispose to exceptional longevity need to be systematically identified and appraised. Here, we conducted a case-control study with 237 exceptional longevity subjects (aged 95–107) and 444 control subjects (aged 40–69) randomly recruited from a “longevity town”—the city of Rugao in China—to investigate the effects of mtDNA variants on exceptional longevity. We sequenced the entire mtDNA genomes of the 681 subjects using a next-generation platform and employed a complete mtDNA phylogenetic analytical strategy. We identified T3394C as a candidate that counteracts longevity, and we observed a higher load of private nonsynonymous mutations in the COX1 gene predisposing to female longevity. Additionally, for the first time, we identified several variants and new subhaplogroups related to exceptional longevity. Our results provide new clues for genetic mechanisms of longevity and shed light on strategies for evaluating rare mitochondrial variants that underlie complex traits.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9750-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mitochondrial genome, Exceptional longevity, mtDNA variations, Private mutations, Subhaplogroups

Introduction

Exceptional longevity (EL) is a complex trait determined by environmental and genetic factors (Christensen et al. 2006). Among genetic factors, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variations have been highlighted for the central role of mitochondria in metabolism. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in numerous age-related traits, including degenerative diseases and aging (Wallace 2010). MtDNA spans approximately 16 kb and encodes 13 core units of OXPHOS, 2 rRNAs, and 22 tRNAs. Several studies analyzing mtDNA haplogroups reported that mtDNA contributes to EL and specifically identified several longevity-associated haplogroups, such as haplogroups J and H in Europeans (De Benedictis et al. 1999); D4a, D5, and D4b2b in Japanese (Alexe et al. 2007); and M9 in Chinese (our previous research) (Cai et al. 2009). The haplogroup analyses usually focused on hypervariable region sequences (HVS) and a limited number of sites at coding regions, while most mtDNA variants, including rare variants, were largely ignored.

Rare variants constitute the majority of human genetic variation and are thought to underlie a large proportion of the inherited susceptibility to human complex traits (Gibson 2011; Tennessen et al. 2012). With the advent of sequencing technology, many rare variants have been shown to be responsible for some complex traits (Schork et al. 2009), including the mtDNA rare variants that underlie some age-related traits (Lam et al. 2012; Tranah et al. 2012). For example, it was reported that a specific profile of mtDNA singleton variants might be implicated with the decline in energy expenditure in elderly persons (Tranah et al. 2012). Recently, the entire mtDNA of EL persons in several European populations were sequenced, suggesting that rare mtDNA variations might affect human longevity with the population specificity (Raule et al. 2014). However, the contributions of rare mtDNA variations to EL have not yet been explored in an Asian population with mtDNA genetic structures that differ from European populations (Wallace 2005).

In previous research, we genotyped 33 mtSNPs that defined 28 major East Asian haplogroups in a relative large sample size (including 463 ELs and 1389 individuals) in the Rugao population. We observed that M9 and several other common haplogroups were associated with EL (Cai et al. 2009). Subsequently, this study aimed to explore the spectrum of rare variants of the whole mitochondrial genome underlying longevity in a Chinese population. We sequenced the entire mitochondrial genome of 237 EL subjects and 444 control subjects recruited from Rugao, a ‘longevity town’ of China, using a next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform. Next, we systematically evaluated the subhaplogroups, private mutations, and mtDNA recurrent mutations underlying exceptional longevity in the Rugao population.

Materials and methods

Populations and samples

The subjects in this study were randomly sampled from the Rugao longevity cohort (Cai et al. 2009). There is a low probability of individuals in general populations surviving to extremely old ages (i.e., ≥95 years). Therefore, researchers universally use younger subjects (i.e., middle-aged people) as control groups. The Rugao longevity cohort is a population-based case-control design that was described in detail in our previous study (Cai et al. 2009). Briefly, 463 unrelated EL subjects (360 women and 103 men; age ranging from 95 to 107 years) were recruited in the Rugao longevity cohort. In addition, 926 unrelated subjects age 60 to 69 years (elderly group) and 463 subjects age 40 to 49 years (middle-aged group) were randomly recruited from the resident registry at the local government offices of Rugao as the control groups. The controls were gender-matched for the EL group.

For this whole mitochondrial genome sequencing study, 237 EL subjects were recruited (182 females and 55 males), including all 69 centenarians of the Rugao longevity cohort and 168 subjects randomly sampled from subjects aged 95 to 99 years. Controls include 221 elderly subjects (171 females and 50 males) and 223 middle-aged subjects (171 females and 52 males), who were randomly sampled from the aforementioned elderly group and middle-aged group. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or his/her authorized family member. The Human Ethics Committee of the Fudan University School of Life Sciences approved the research.

Genomic libraries preparation and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the method explained in a previous study (Cai et al. 2009). For each sample, the entire mtDNA genome was amplified using PCR, and 11 overlapping products were mixed in approximately equal mass after determining their concentration. The fragment libraries were prepared using an optimized method referring to Illumina and a literature-reported protocol (Cronn et al. 2008). Briefly, the whole mtDNA genome of subjects was sheared by DNase I, and the sheared fragments were purified and concentrated using a QIAquick PCR Purification spin column (QIAGEN Inc., Hilden, Germany). T4 DNA polymerase, T4 phosphonucleotide kinase, and the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase were used to fill 5′ overhangs and to remove 3′ overhangs of sheared fragments. Next, A-residues were added at 3′ terminal sides by using dATP and Klenow (3′-5′ exo-). The adaptors containing unique barcode sequences were then ligated to the fragments. The fragments ranging from 200 to 250 bp were harvested using an agarose electrophoresis platform, and the products were isolated adopting the QIAGEN MinElute Gel Extraction spin columns (QIAGEN Inc., Hilden, Germany). Then, each library was amplified using standard Illumina primers and running 15 PCR cycles. After those libraries had been purified again, the DNA concentration was quantified, with 30 ng for each pooled together. The oligonucleotide mix was sequenced on Illumina’s HiSeq 2000.

Whole mtDNA sequence assembly

Original sequencing reads were exported to FASTQ files, and BWA v0.5.7 (Li and Durbin 2009) was then used to align the reads to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence to generate binary sequence alignment/map (BAM) files of mtDNA genomes (Li et al. 2009). The duplicate reads were removed by MarkDuplicates, implemented in Picard v1.36, and the mtDNA sequences were locally realigned by GATK v1.2.59 (McKenna et al. 2010). Pileup files were generated by SAMtools v1.0.16 (Li et al. 2009). Consensus sequences were then obtained based on the pileup files, and indels were verified manually. Variations for haploid and missing sites were identified according to the previously used criteria (Zheng et al. 2011).

Quality control

With randomly blind sampling, 16 samples were repeated on the Illumina sequencing platform, and the mtDNA HVS-I regions of 20 samples were re-sequenced on the Sanger platform. The validated results were concordant with previous sequences.

Haplogroup assignment

Complete sequences were aligned to rCRS by MUSCLE v3.8.31 and manually verified; they were then assigned to the haplogroups according to PhyloTree Build 14. As in PhyloTree, positions 309.1C (C), 16182C, 16183C, 16193.1C (C), and 16519 were not used for haplogroup assignment because these positions were subject to highly recurrent mutations.

Data analysis

Unique characteristics of mtDNA such as strict maternal inheritance and lack of recombination make mtDNA variants occur in an orderly manner that could be phylogenetically tractable (Ballard and Rand 2005). Additionally, the high mutation rate and small genome size often lead to frequently recurrent mutations at the same sites in mtDNA (Pakendorf and Stoneking 2005). Thus, in case-control studies, the classical association analysis that compares the significantly different frequency of the mt-variants between case and control groups is inadequate, and the phylogenetic tree is essential for studying the pathogenic role of specific mtDNA variations (Kong et al. 2006). To explore the EL predisposition of variants across the entire mtDNA genome, we employed several strategies based on a high-resolution phylogenetic tree. A high-resolution mtDNA phylogeny tree is favorable for the determination of (1) recurrent mutations, (2) private mutations that are on the external branch in the mtDNA phylogeny, and (3) subhaplogroups that are specific to either cases or controls. In this study, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using 681 sequences from Rugao subjects (from this study) and an additional 4500 East Asian whole mtDNA sequences (including published data from the Phylotree database (van Oven and Kayser 2009) and unpublished data) using the maximum likelihood method (PhyML v3.0) (Guindon et al. 2010) and further confirmed by the median-joining method (Network v4.6) (Bandelt et al. 1999). The frequencies of major haplogroups and variations (excluding private mutations) were compared between ELs and controls. We grouped private mutations into genes or genome regions and then evaluated their contributions to EL using two comparisons: (1) the total number of private functional mutations in genes or regions were compared between two groups and (2) the ratios of nonsynonymous/synonymous (N/S) private mutations in protein-coding genes were compared between two groups. Recurrent mutations that occur multiple times independently in mtDNA haplogroups shared exclusively in ELs or in controls were searched along the phylogenetic tree. All comparisons were tested by the Pearson chi-square test or the Fisher exact test.

Results

We obtained 681 complete mtDNA sequences; the average coverage was 1084×, and the minimum coverage was 52×. Approximately 5 % of the subjects were re-sequenced for validation. Overall, 1974 mt-variants were called, and 115 variants had a minor allele frequency (MAF) greater than 5 %. We observed several major haplogroups in the Rugao population: D4 (16.4 %), F (13.1 %), B4 (12.3 %), M7 (9.1 %), N9 (6.9 %), D5 (7.1 %), A (7 %), and B5 (5.2 %). These haplogroups represent the common haplogroups in East Asians. For the major haplogroups, a significantly higher prevalence of M9 was observed in controls (2.03 %) than in ELs (0 %) (Supplementary Table S1). This finding was consistent with the results of our previous report in a large sample of Rugao subjects (463 cases vs. 1389 controls) (Cai et al. 2009), suggesting high concordance between the studies.

We observed several mtDNA variants that occurred exclusively in the EL group or in the control group that reached statistical significance (P < 0.05) (see Table 1). Using the phylogenetic tree, we could pinpoint the occurrence numbers of these variants and their associated haplogroups (listed in Table 1). T3394C, a nonsynonymous variant (T3394C, Y30H, ND1), presented exclusively in the control group in 12 subjects with four different subhaplogroups (P = 0.01 compared with EL subjects (Table 1)). We observed G12561A, T789C, C6386T, and G11447A exclusively in EL subjects, and this difference reached the level of statistical significance (P < 0.05). All four mtDNA variants are recurrent mutations, and two had potentially functional significance (T789C codes 16s rRNA, and G11447A induces valine changes to methionine in the ND4 gene).

Table 1.

MtDNA variants associated with exceptional longevity (EL) and their haplogroup occurrences

| Mutations | EL (n = 237) | Control (n = 444) | P value (Fisher) | Gene | Amino acid change | Recurrent mutation times | Related haplogroups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3394C | 0 | 12 | 0.01 | ND1 | Y30H | 4 | M9, Two haplogroups deriving from B4c1b2ca, Z3 |

| T14308C | 0 | 10 | 0.02 | ND6 | Syn | 2 | M9, F2a |

| A1041G | 0 | 9 | 0.03 | 12s rRNA | N/A | 1 | M9 |

| A2833G | 0 | 8 | 0.056 | 16s rRNA | N/A | 4 | A4, F4, D5b, B5b, |

| A153G | 0 | 8 | 0.056 | Control region | N/A | 2 | M9, F1a4 |

| T16325C | 0 | 8 | 0.056 | Control region | N/A | 6 | Y1, Ga1, A4d, B4c, M7b2, D4b2 |

| G12561A | 4 | 0 | 0.01 | ND5 | Syn | 2 | M7b2, F1a |

| T789C | 3 | 0 | 0.04 | 12s rRNA | N/A | 3 | D4a, D4b2, C7a1 |

| C6386T | 3 | 0 | 0.04 | Cox1 | Syn | 2 | C7, B5b |

| G11447A | 3 | 0 | 0.04 | ND4 | V230M | 2 | C7c, M7 |

N/A represents that the variant is not in the protein-coding regions

aTwo haplogroups were not previously reported. One haplogroup is B4c1b2c-T3394C-G7119A; another is B4c1b2c-G9575A-10493C-T16136C-T16249C-C16291T

A total of 1680 private mutations on the external branch of the mtDNA phylogeny were identified. We compared private functional mutations across 13 protein-coding genes, tRNA and rRNA genes between ELs and controls, observing a marginally significant difference in the COX1 gene (Supplementary Table S2). In a subsequent analysis stratified by gender, we observed a significantly higher load of private nonsynonymous mutations in the COX1 gene in female ELs than in female controls (P = 0.01). This difference was also found by using another algorithm that compared the ratio of nonsynonymous and synonymous mutations in EL and control females (P = 0.02) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The distributions of private mtDNA functional mutations in 13 protein-coding genes, rRNA, and tRNA genes in female EL and control subjects

| Region/gene | ELa

(n = 182) |

Control (n = 342) |

P value | ELb

(N/S) |

Control (N/S) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | 10 | 27 | 0.34 | 10/14 | 27/20 | 0.21 |

| ATP6 | 7 | 23 | 0.203 | 7/9 | 23/15 | 0.26 |

| ATP8 | 3 | 4 | 0.7 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 1 |

| COX | 26 | 30 | 0.08 | 26/36 | 30/68 | 0.14 |

| COX1 | 15 | 10 | 0.01* | 15/14 | 10/31 | 0.02* |

| COX2 | 4 | 6 | 0.74 | 4/13 | 6/17 | 1 |

| COX3 | 7 | 14 | 0.9 | 7/9 | 14/20 | 0.86 |

| Cytb | 10 | 26 | 0.4 | 10/22 | 26/32 | 0.21 |

| ND | 41 | 67 | 0.51 | 41/68 | 67/164 | 0.11 |

| ND1 | 11 | 16 | 0.52 | 11/10 | 16/27 | 0.25 |

| ND2 | 4 | 11 | 0.59 | 4/14 | 11/29 | 0.76 |

| ND3 | 4 | 3 | 0.25 | 4/2 | 3/10 | 0.13 |

| ND4 | 6 | 11 | 0.96 | 6/10 | 11/34 | 0.32 |

| ND4L | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0/3 | 1/4 | 1 |

| ND5 | 13 | 23 | 0.86 | 13/25 | 23/43 | 0.95 |

| ND6 | 3 | 2 | 0.33 | 3/4 | 2/17 | 0.1 |

| All proteins | 87 | 150 | 0.59 | 87/140 | 150/284 | 0.34 |

| 12s rRNA | 13 | 23 | 0.86 | – | – | – |

| 16s rRNA | 12 | 20 | 0.74 | – | – | – |

| rRNAs | 25 | 43 | 0.73 | – | – | – |

| tRNAs | 24 | 34 | 0.31 | – | – | – |

*P < 0.05

aTotal number of private nonsynonymous or functional mutations in genes and regions were compared between two groups

bNonsynonymous/synonymous ratios (N/S) of private mutations in protein-coding genes were compared between two groups

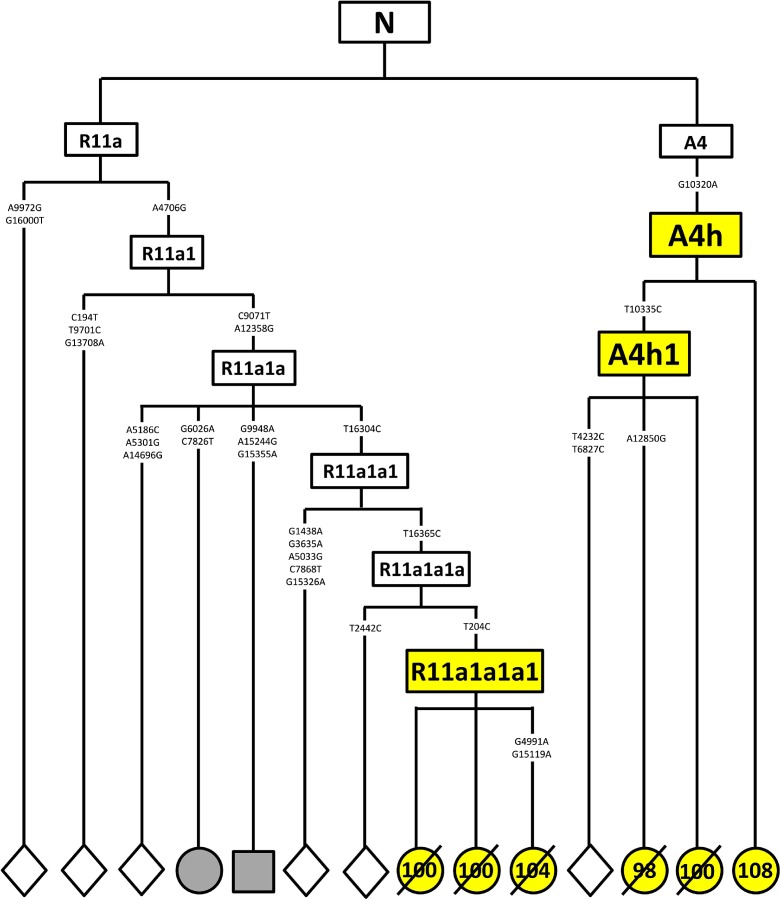

Considering the possibility of EL enrichment in some subhaplogroups, we tentatively searched for subhaplogroups that were specific to the EL group in the phylogenetic tree. We found three haplogroups (M7c2, A4h and R11a1a1a1) that presented exclusively in the EL group, indicating a marginal association with EL (P = 0.042). A4h and R11a1a1a1, which were found in females only, were newly discovered and named in this study (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Five of the six A4h or R11a1a1a1 carriers reached 100 years old, and a 108-year-old woman was still alive by 2013. In A4h, G10320A (V88I, ND3) is a missense mutation.

Fig. 1.

Novel haplogroups exclusively discovered in EL subjects in the Rugao population. (Yellow shadow) Rugao longevity subjects in which the numbers represent the ages (dashed objects mean death ages); (gray shadow) Rugao control subjects; (diamond) previously published sequences nonrelevant to our sample; (circle) female individual, (square) male individual

Table 3.

Novel haplogroups present exclusively in EL or control subjects

| Novel haplogroups | All subjects | P value (Fisher) | Functional mutations | AA changes | Genes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | Control | |||||

| (N = 237) | (N = 444) | |||||

| A4h | 3 | 0 | 0.04 | G10320A | V88I | ND3 |

| R11a1a1a | 3 | 0 | 0.04 | N/Aa | N/A | N/A |

aN/A represents that there were no potentially functional mutations defining the subhaplogroups

Discussion

Human life expectancy has been increasing in recent decades with improvements in nutrition, sanitation, and health care. However, few people are expected to survive to extremely old age (i.e., ≥95 years) (Vaupel 2010). According to the Fifth Population Census of China conducted in 2000 (Population Census Office of Rugao, 2000), more than 23,000 people in Rugao were ≥80 years, while only approximately 700 (∼0.65‰ of the Rugao population) were ≥95 years. Based on the average life expectancy of the Rugao population (75.58 years), EL people aged ≥95 years could be representative of the extreme longevity trait. Sequencing the mitochondrial genomes of the EL is an efficient strategy to identify rare mtDNA variants underlying longevity, as the attributed variants would be enriched (Cirulli and Goldstein 2010). In the present study, we sequenced the entire mtDNA of 237 EL subjects (including 69 centenarians) and 444 younger control subjects and then employed strategies based on a high-resolution phylogenetic tree to evaluate the contribution to EL of variants in the whole mitochondrial genome.

M9 was significantly less present in the EL group than in the control group in our previous haplogroup analysis by 33 mtSNPs genotyping (463 cases vs. 1389 controls) (Cai et al. 2009). However, in that type of haplogroup analysis, it is difficult to distinguish whether a single mutation, a set of mutations, or some deeper genetic structures in matrilineal backgrounds account for the association, which might result in inconsistent results in studies even in the same ethnic group. For example, haplogroup J has been reported to be significantly different between EL and younger individuals in northern Italy (De Benedictis et al. 1999), Ireland (Ross et al. 2001), and Finland (Niemi et al. 2003). However, this difference has not been detected in other European populations (Collerton et al. 2013; Dato et al. 2004; Pinos et al. 2012). The recent whole mtDNA genome study in 13 European populations detected that rare mtDNA variants rather than haplogroup J were associated with longevity (Raule et al. 2014). In this study, we found T3394C, A1041G, and T14308C, the variants of the motif of M9a, were significantly more prevalent in controls than in EL. One of these variants, T3394C, presented in 12 control subjects but was absent in the EL group and was found to occur independently in three other subhaplogroups based on the high-resolution phylogeny tree. Such recurrent mutations were usually considered to provide a crucial clue for the etiology of disorders (Montoya et al. 2009). Our observations of T3394C suggested that this mutation confers an increased risk against longevity. T3394C results in the substitution of a highly conserved tyrosine to histidine (Y30H) in the ND1 gene. This transition has long been known for its association with several diseases, such as Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), as well as with high-altitude adaptation for Tibetans (Ji et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2010). These associations indicate the importance of the mutation on NADH dehydrogenase functional maintenance. Furthermore, two recurrent mutations with potential function, T789C (in 12s rRNA) and G11447A (V230M in ND4), were first identified as exclusively occurring in EL subjects. Mutations in mtDNA rRNA genes were reported to be associated with hearing loss (Guan 2011) and some aging traits, such as nerve conduction velocity (Katzman et al. 2014) and Alzheimer’s disease (Tanno et al. 1998). Two of the point mutations in 16s rRNA with the age-associated T414G variant were identified as relating to bioenergetic change in a cybrid study (Seibel et al. 2008). The fundamental mechanism for the effect on longevity of T789C and other candidate variants in rRNA genes needs to be studied more.

The accumulation of rare mutations within genes or genomic regions may influence a phenotype in important ways (Schork et al. 2009). Evaluating the combined effect of rare mutations may reveal the potential mechanism underlying EL. In mitochondrial genomes, private mutations that are located in external branches are more likely than mutations in internal branches to affect protein function in mtDNA (Ruiz-Pesini et al. 2004). We explored the private nonsynonymous mutations of 13 protein-coding genes, tRNA and rRNA genes in EL. In all 681 subjects, no significance was observed in any gene and genomic region. However, in female subjects, the load of private nonsynonymous mutations in the COX1 gene was significantly higher in ELs (8.2 %) than in controls (2.9 %). The NS/S of private nonsynonymous mutations, which could represent the degree of functional conservativeness of a gene, also presented significantly higher in the COX1 gene in female ELs (1.07) than in controls (0.32). These results were not similar to those reported in a recent study conducted in Europeans. That study observed that the frequency of nonsynonymous mutations in protein-coding genes was higher in controls than in individuals aged 90 and above in Danish and southern European populations, while an opposite trend was observed in a Finnish population, suggesting that the effect of rare mtDNA mutations on longevity might be population specific (Raule et al. 2014). Our study identified a pattern of mtDNA variants underlying longevity in a Rugao population that differed from the pattern found in a European longevity population (Raule et al. 2014). Human mtDNA is characterized by a continent-specific distribution, which is considered to be a result of climate selection (Ruiz-Pesini et al. 2004) and genetic drift with long-term geographic isolation (Harpending et al. 1998). This phenomenon is probably one of the factors contributing to the population-specific effect of mtDNA on longevity. COX1 is one of the essential subunits of the catalytic core of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), which is the terminal enzyme of the respiratory chain and catalyzes the oxidation of cytochrome c by molecular oxygen (Soto et al. 2012). Complex IV is the only mitochondrial respiratory complex that shows an age-related decline in activity (Ferguson et al. 2005; Sohal et al. 1995). Nonsynonymous mutations in the COX1 gene might change the activity or the assembly stability of complex IV (Namslauer and Brzezinski 2009) and hence influence the efficiency of overall energy conversion and ROS producing, which might contribute to human aging and longevity.

Multiple factors might account for the absence of an association between private mutations and longevity in males. One possible explanation is the sex-specific effects of mtDNA variants. For many species, including human beings, the sex-specific effects of mtDNA variants are commonly observed in diseases, aging, and longevity (Frank and Hurst 1996; Tanaka et al. 2007; Wolff and Gemmell 2013). The underlying mechanism of such a sexual dimorphism was suggested to be the maternal transmission of mitochondrial genomes resulting in evolutionary dead ends for the mtDNA of males. Thus, mutations through females might be the only response to selection of mtDNA (Gemmell et al. 2004). Population genetic models and experiments in flies found that mtDNA mutations that were slightly deleterious, neutral, or even beneficial to females could be deleterious to males, indicating that mtDNA variations have more influence on male aging than female aging (Camus et al. 2012; Innocenti et al. 2011). This finding is largely similar to our observations of higher levels of nonsynonymous replacements in the COX1 gene in longevity females. Another possible explanation is that the significantly smaller sample size of male ELs than female ELs induced a lower power to test the significance. In many vertebrates, including humans, there are more female than male longevity individuals. This advantage of female longevity was also observed in the Rugao population, in which the female to male longevity ratio is 3.5:1.

Two new subhaplogroups with rare frequencies—A4h and R11a1a1a1—were observed to be significantly enriched based on a fine-scaled phylogenetic tree. Notably, most EL subjects belonging to A4h and R11a1a1a were female centenarians. A4h was characterized by G10320A, which leads to a substitution from valine to isoleucine in the ND3 gene. Interestingly, F3, another haplogroup carrying G10320A as a defining variant, was also reported to be associated with longevity in the Bama Chuang population in China (Feng et al. 2011).

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size (237 cases vs. 444 controls) was relatively small, making the power in genetic association studies was still low. Second, the high-resolution phylogenetic tree was reconstructed with approximately 5000 complete mtDNA sequences, but it still cannot cover all the deep lineages in the East Asian mtDNA pool. Lastly, no associations could meet the level of statistical significance after multiple comparisons adjustment in this study. However, there are several strengths to this study: (1) complete mtDNA sequences of exceptional longevity were first sequenced in a Chinese population; (2) several strategies based on a high-resolution phylogenetic tree were employed, allowing for systematic evaluation of the role of deep genetic structures including recurrent mutations, private mutations, and the subhaplogroups; and (3) the consistency was high between this study and our previous study.

In summary, we sequenced 237 exceptional longevity subjects and 444 control subjects using a next-generation sequencing platform. The variants in the whole mtDNA genome were evaluated systematically based on a high-resolution phylogenetic tree. We identified that T3394C may be a factor contributing to a risk against longevity, and we observed a higher load of private missense mutations in the COX1 gene predisposing to EL occurrence in the Rugao population of China. Furthermore, for the first time, we reported several variants and new subhaplogroups related to EL. Our results provide new information for the study of longevity and shed light on the strategies for evaluating rare mitochondrial variants underlying complex traits.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 71 kb)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (31171216), the National Basic Research Program (2012CB944600), the Ministry of Science and Technology (2011BAI09B00), and the Ministry of Health (201002007) of China.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interests were reported.

Footnotes

Lei Li and Hong-Xiang Zheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Li Jin, Phone: +86 21 65643714, Email: lijin.fudan@gmail.com.

Xiaofeng Wang, Phone: +86 21 65643714, Email: xiaofengautomatic@gmail.com.

References

- Alexe G, Fuku N, Bilal E, et al. Enrichment of longevity phenotype in mtDNA haplogroups D4b2b, D4a, and D5 in the Japanese population. Hum Genet. 2007;121:347–356. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO, Rand DM. The population biology of mitochondrial DNA and its phylogenetic implications. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2005;36:621–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.091704.175513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XY, Wang XF, Li SL, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups with exceptional longevity in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus MF, Clancy DJ, Dowling DK. Mitochondria, maternal inheritance, and male aging. Curr Biol CB. 2012;22:1717–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Johnson TE, Vaupel JW. The quest for genetic determinants of human longevity: challenges and insights. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:436–448. doi: 10.1038/nrg1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli ET, Goldstein DB. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:415–425. doi: 10.1038/nrg2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collerton J, Ashok D, Martin-Ruiz C, et al. Frailty and mortality are not influenced by mitochondrial DNA haplotypes in the very old. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(2889):e2881–e2884. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronn R, Liston A, Parks M, Gernandt DS, Shen R, Mockler T. Multiplex sequencing of plant chloroplast genomes using Solexa sequencing-by-synthesis technology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dato S, Passarino G, Rose G, et al. Association of the mitochondrial DNA haplogroup J with longevity is population specific. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:1080–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis G, Rose G, Carrieri G, et al. Mitochondrial DNA inherited variants are associated with successful aging and longevity in humans. FASEB J. 1999;13:1532–1536. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Zhang J, Liu M, et al. Association of mtDNA haplogroup F with healthy longevity in the female Chuang population, China. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M, Mockett RJ, Shen Y, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Age-associated decline in mitochondrial respiration and electron transport in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem J. 2005;390:501–511. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA, Hurst LD. Mitochondria and male disease. Nature. 1996;383:224. doi: 10.1038/383224a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell NJ, Metcalf VJ, Allendorf FW. Mother’s curse: the effect of mtDNA on individual fitness and population viability. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. Rare and common variants: twenty arguments. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;13:135–145. doi: 10.1038/nrg3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan MX. Mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutations associated with aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpending HC, Batzer MA, Gurven M, Jorde LB, Rogers AR, Sherry ST. Genetic traces of ancient demography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1961–1967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti P, Morrow EH, Dowling DK. Experimental evidence supports a sex-specific selective sieve in mitochondrial genome evolution. Science. 2011;332:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1201157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji F, Sharpley MS, Derbeneva O, et al. Mitochondrial DNA variant associated with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy and high-altitude Tibetans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202484109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman SM, Strotmeyer ES, Nalls MA, et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation associated with peripheral nerve function in the elderly. J Gerontol. 2014 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong QP, Bandelt HJ, Sun C, et al. Updating the East Asian mtDNA phylogeny: a prerequisite for the identification of pathogenic mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2076–2086. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam ET, Bracci PM, Holly EA, et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation and risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:686–695. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya J, Lopez-Gallardo E, Diez-Sanchez C, Lopez-Perez MJ, Ruiz-Pesini E. 20 years of human mtDNA pathologic point mutations: carefully reading the pathogenicity criteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namslauer I, Brzezinski P. A mitochondrial DNA mutation linked to colon cancer results in proton leaks in cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3402–3407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811450106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemi AK, Hervonen A, Hurme M, Karhunen PJ, Jylhä M, Majamaa K (2003) Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms associated with longevity in a Finnish population. Hum Genet 112(1):29–33. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0843-y [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pakendorf B, Stoneking M. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinos T, Nogales-Gadea G, Ruiz JR, et al. Are mitochondrial haplogroups associated with extreme longevity? A study on a Spanish cohort. AGE. 2012;34:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Census Office of Rugao (20000 Tabulation on the 2000 population census of Rugao City, Jiangsu Province. p. 8

- Raule N, Sevini F, Li S, et al. The co-occurrence of mtDNA mutations on different oxidative phosphorylation subunits, not detected by haplogroup analysis, affects human longevity and is population specific. Aging Cell. 2014;13:401–407. doi: 10.1111/acel.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross OA, McCormack R, Curran MD, Duguid RA, Barnett YA, Rea IM, Middleton D (2001) Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism: its role in longevity of the Irish population. Exp Gerontol 36:1161–1178. doi:10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00094-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Pesini E, Mishmar D, Brandon M, Procaccio V, Wallace DC. Effects of purifying and adaptive selection on regional variation in human mtDNA. Science. 2004;303:223–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1088434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schork NJ, Murray SS, Frazer KA, Topol EJ. Common vs. rare allele hypotheses for complex diseases. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibel P, Di Nunno C, Kukat C, et al. Cosegregation of novel mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene mutations with the age-associated T414G variant in human cybrids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5872–5881. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal RS, Sohal BH, Orr WC. Mitochondrial superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation, protein oxidative damage, and longevity in different species of flies. Free Radic Bio Med. 1995;19:499–504. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00037-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto IC, Fontanesi F, Liu J, Barrientos A. Biogenesis and assembly of eukaryotic cytochrome c oxidase catalytic core. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:883–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Fuku N, Nishigaki Y, et al. Women with mitochondrial haplogroup N9a are protected against metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2007;56:518–521. doi: 10.2337/db06-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno Y, Okuizumi K, Tsuji S. mtDNA polymorphisms in Japanese sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:S47–S51. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(98)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O’Connor TD, et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranah GJ, Lam ET, Katzman SM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation is associated with free-living activity energy expenditure in the elderly. BBA-Bioenergetics. 2012;1817:1691–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oven M, Kayser M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E386–E394. doi: 10.1002/humu.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel JW. Biodemography of human ageing. Nature. 2010;464:536–542. doi: 10.1038/nature08984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:440–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JN, Gemmell NJ. Mitochondria, maternal inheritance, and asymmetric fitness: why males die younger. Bioessays. 2013;35:93–99. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zhou X, Li C, et al. Mitochondrial haplogroup M9a specific variant ND1 T3394C may have a modifying role in the phenotypic expression of the LHON-associated ND4 G11778A mutation. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng HX, Yan S, Qin ZD, Wang Y, Tan JZ, Li H, Jin L. Major population expansion of East Asians began before neolithic time: evidence of mtDNA genomes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 71 kb)