Abstract

Objective

To compare psychiatric in- and outpatient care during the 5 years before first delivery in primiparae delivered by caesarean section on maternal request with all other primiparae women who had given birth during the same time period.

Design

Prospective, population-based register study.

Setting

Sweden.

Sample

Women giving birth for the first time between 2002 and 2004 (n = 64 834).

Methods

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request (n = 1009) were compared with all other women giving birth (n = 63 825). The exposure of interest was any psychiatric diagnosis according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ninth revision, ICD–9, 290–319; tenth revision, ICD–10, F00–F99) in The Swedish national patient register during the 5 years before first delivery.

Main outcome measures

Psychiatric diagnoses and delivery data.

Results

The burden of psychiatric illnesses was significantly higher in women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request (10 versus 3.5%, P < 0.001). The most common diagnoses were ‘Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders and somatoform disorders’ (5.9%, aOR 3.1, 95% CI 1.1–2.9), and ‘Mood disorders’ (3.4%, aOR 2.4, 95% CI 1.7–3.6). The adjusted odds ratio for caesarean section on maternal request was 2.5 (95% CI 2.0–3.2) for any psychiatric disorder. Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request were older, used tobacco more often, had a lower educational level, higher body mass index, were more often married, unemployed, and their parents were more often born outside of Scandinavia (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request more often have a severe psychiatric disease burden. This finding points to the need for psychological support for these women as well as the need to screen and treat psychiatric illness in pregnant women.

Keywords: Caesarean section, maternal request, mental health, psychiatric diagnoses

Introduction

During the last decades there has been a steady increase in caesarean section rates in many countries. Changes in maternal characteristics such as higher body mass indexes, higher age and lower parity,1 as well as in the attitudes of midwives and obstetricians, partly explain this increase.2 Caesarean section on maternal request in the absence of any medical indication is another reason for the increase.1,3 This request might arise from a fear of childbirth (FOC),4–12 a previous negative or traumatic birth experience,4–7 and/or earlier obstetric complications, such as an emergency caesarean section.5,6

The increase in caesarean section on maternal request may reflect a true higher prevalence of FOC, or a greater tendency among women to express their fears and wishes. This possibility is, however, difficult to evaluate, as there are many ways to measure and estimate the prevalence of FOC.4–9,11,12 A meta-analysis and systematic review found the pooled global preference for a caesarean section to be 15.6%. The preference for caesarean section was most common among women in Latin America (24.4%) and least common in Europe (11%).13

The obstetrician's decision for a planned caesarean section is based on a combination of medical as well as psychological indications. A study conducted in 1999–2000 found that 30.5% of women preferring a caesarean section early in pregnancy subsequently gave birth by elective caesarean section. Of these, 48% were registered as caesarean section on maternal request.14 In studies by Wiklund et al.,15 primiparae who requested a caesarean section more often planned to have only one child, did not attend parenthood education, perceived their health to be less good than they would like, and were more often born outside of Sweden, compared with women giving birth vaginally. A nationwide study in Norway also found anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, a history of sexual abuse in childhood, and low satisfaction in relationship to partner to be associated with a preference for caesarean section.7

Fear of childbirth (FOC) is a frequently reported factor associated with caesarean section on maternal request, especially for primiparae.5,8 FOC seems to be more common among women with psychiatric diagnoses.16 Women with FOC also use psychiatric health care and psychotropic drugs to a greater extent.17 Hence, one can speculate that women requesting caesarean section may represent a group more vulnerable to psychiatric illness. This has led to the hypothesis that women requesting a caesarean section are more likely to have psychiatric illness than women preferring a vaginal delivery. The aim of this study with a large cohort from Swedish national registers was to determine whether psychiatric illness, defined as psychiatric in- and outpatient care in the 5 years before delivery, was more common among primiparae giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request.

Methods

Data collection

The Swedish medical birth register (MBR) contains information on all pregnancies leading to parturition in Sweden since 1973. Data on women's characteristics, pregnancies, deliveries, and newborns are reported. The validity of the MBR is high. It covers approximately 99% of all births in Sweden.18 The national patient register (NPR) has recorded public inpatient care since 1987, and public outpatient care since 2001. Date of admission, discharge, and visit, as well as diagnoses, can be retrieved from this registry. The quality of data from the inpatient care system is generally high, with 90–94.8% having a main diagnosis registered during the study period. The data from the outpatient care is less reliable, with a main diagnosis registered in 24.3–49.1% of records during the study period.19 The psychiatric diagnoses registered in NPR are made by a psychiatrist. The total population register (TPR) includes information on births, deaths, citizenship, and marital status, as well as migration and country of birth for Swedish residents born abroad.20 The causes of death register records information on all deceased persons registered in Sweden at the time of death since 1961.21 The education register records data on highest educational level and educational area.22 The multi-generation register is the part of the TPR that records kinship. By using this register, we could identify the parents of our study population. Since 1968 the register is considered to have good coverage.23

The study population consisted of all women born in 1973–1983 who were alive and still living in Sweden at 13 years of age, based on the TPR and the MBR (n = 500 245). Information from the other registers was gathered by using the women's unique personal identification number. Women with missing values on birthweight or gestational length were excluded (n = 3360). Women with extremely high or low birthweights compared with length of gestation were also excluded (n = 2193). From the final cohort (n = 494 692) we selected women giving birth for the first time between 2002 and 2004 (n = 64 834). Multiparae were excluded to avoid confounding because of previous negative birth experiences. Unfortunately, we had no further data on previous reproductive history: for example, legal abortion. Women were divided into cases and controls according to mode of delivery. Cases were women with a delivery diagnosis of O82.8 from the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD–10; n = 1009, 1.6%). O82.8 is labelled ‘caesarean section on psychosocial indication’ in Sweden, thereby not stating that the women requested a caesarean section; however, it is the diagnosis code applied for women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request. Controls were women giving birth on the basis of all other indications during the same time period (n = 63 847). Controls were divided into the following groups: vaginal delivery (n = 55 012, 84.9%); emergency caesarean section (n = 5826, 9%); and elective caesarean section for all reasons except O82.8 (n = 2859, 4.4%). For 128 (0.2%) women the diagnosis for mode of delivery was missing, and they were therefore treated as a ‘missing’ group. The exposure of interest was psychiatric in- and outpatient care during the 5 years before delivery (1997–2004). This was defined as any psychiatric diagnosis during a time period of 5 years before the date of first delivery in the NPR. The time period was determined by subtracting 5 years from the date of delivery and then searching for date of admission or date of visit registered together with a psychiatric diagnosis. This time period was considered appropriate because psychiatric illnesses can be transient or chronic.

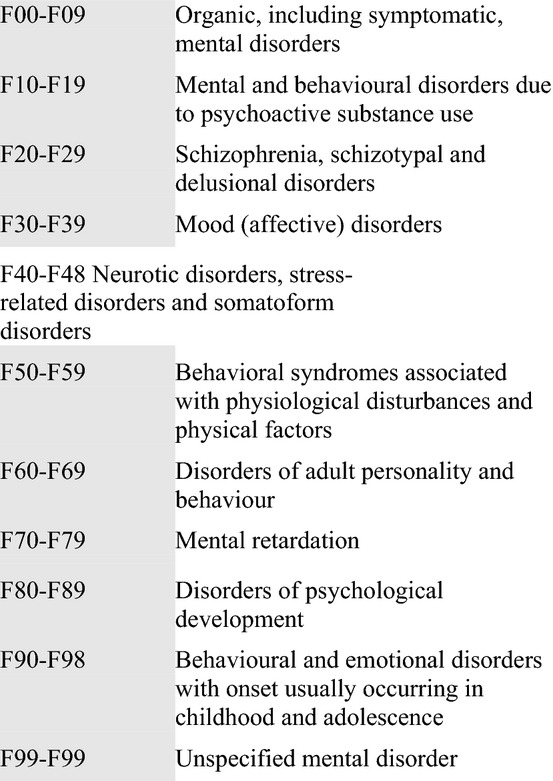

The diagnoses are based on the Swedish version of the ICD from the World Health Organization.24 In 1997 the healthcare system changed the ICD version used from ICD–9 to ICD–10. During this year, ICD–9 and ICD–10 were used interchangeably.25 Psychiatric diagnoses in ICD–9 and ICD–10 were identified as codes 290–319 and F00–F99, respectively.24 Therefore, we searched for both ICD–9 and -10 codes in 1997, and only for ICD–10 codes in 1998–2004. ICD–9 codes were translated to ICD–10 using a conversion table.26 Psychiatric disorders were divided into 11 categories according to ICD–10 (Figure 1).24

Figure 1.

Categories of psychiatric disorders.

The following background variables were registered at admission to antenatal care: age, body mass index (BMI), tobacco use, and somatic diseases. Age at first childbirth was categorised into <25 or >25 years old. BMI was divided into five categories (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, and ≥35 kg/m2). From the other registers we gathered information on parents’ country of birth, the women's marital status, highest educational level, and working status in 2004. Parents’ country of birth was categorised as born in or outside of Scandinavia. According to Statistics Sweden's definition of paid work in 2004, income >39 300 SEK per year was defined as employed and <39 300 SEK was defined as unemployed.

Statistical analyses

Pearson's chi-square test was used to test for univariate statistical differences on sociodemographic data, somatic diseases, as well as each psychiatric disorder between cases (caesarean section on maternal request) and controls (other modes of delivery). Pearson's chi-square test was also used to test for statistical differences on ‘mode of delivery’ and each psychiatric disorder.

Multiple logistic regression was used to estimate the risk for caesarean section on maternal request, where caesarean section on maternal request was considered the outcome, and psychiatric disorder, sociodemographic variables (age, BMI, parents’ country of birth, tobacco use, working status, educational level, and marital status), and somatic diseases (urinary tract infection, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes mellitus, and lung diseases) were considered the predictors. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were carried out in spss 19.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request differed from all other women giving birth during this period (Table 1). They were older, used tobacco more often, had a lower educational level, were more often unemployed, had a higher BMI, and had parents who were more often born outside of Scandinavia. In addition, women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request were more likely to have a somatic disease recorded in the MBR, compared with controls (n = 356, 35.3% versus n = 16 374, 25.7%; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data on the women of the two different study groups

| Mode of delivery caesarean on maternal request n (%) | Other delivery n (%)* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <25 years | 319 (31.6) | 22 543 (35.3) | 0.015 |

| >25 years | 690 (68.4) | 41 282 (64.7) | |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Yes | 185 (18.3) | 8281 (13) | <0.001 |

| No | 824 (81.7) | 55 544 (87) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Elementary | 161 (16) | 6433 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| High school | 600 (59.5) | 34 178 (53.5) | |

| University | 243 (24.1) | 23 026 (36.1) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.5) | 188 (0.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 365 (36.2) | 20 915 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Unmarried | 609 (60.5) | 42 027 (65.9) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 33 (3.3) | 790 (1.2) | |

| Working status | |||

| Employed | 875 (86.9) | 58 266 (91.4) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 132 (13.1) | 5469 (8.6) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 | 16 (1.8) | 1431 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 484 (56) | 34 400 (62.3) | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 213 (24.6) | 13 137 (23.8) | |

| 30.0–34.9 | 100 (11.6) | 4301 (7.8) | |

| ≥35 | 52 (6) | 1935 (3.5) | |

| Parents' country of birth | |||

| Both parents born in Scandinavia | 917 (90.9) | 60 013 (94) | <0.001 |

| One or both parents born outside of Scandinavia | 92 (9.1) | 3812 (6) | |

Other delivery, including ‘Vaginal’, ‘Emergency caesarean section’, ‘Elective caesarean section’, and ‘Mode of delivery missing’.

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request had more often been diagnosed with a psychiatric diagnosis, compared with controls (10 versus 3.5%, P < 0.001). Significant differences were found for all categories of psychiatric disorders, except ‘Mental retardation’ (0 versus 12 women, P = 0.663) and ‘Disorders of psychological development’ (1 versus 16 women, P = 0.234; Table 2). The most common diagnoses among the women were ‘Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders and somatoform disorders’, ‘Mood disorders’, and ‘Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances’ (Table 2). The prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was 10% in women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request, 3.4% in emergency caesarean section or vaginal delivery, and 4.4% in elective caesarean section (Table 3).

Table 2.

Psychiatric disorders among the women in the two study groups

| Mode of delivery caesarean section on maternal request n (%) | Other delivery n (%)* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any psychiatric disorder | |||

| Yes | 101 (10) | 2215 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 908 (90) | 61 610 (96.5) | |

| Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances | |||

| Yes | 21 (2.1) | 570 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 988 (97.9) | 63 255 (99.1) | |

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | |||

| Yes | 12 (1.2) | 182 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 997 (98.8) | 63 643 (99.7) | |

| Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | |||

| Yes | 14 (1.4) | 310 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 995 (98.6) | 63 515 (99.5) | |

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | |||

| Yes | 6 (0.6) | 34 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 1003 (99.4) | 63 791 (99.9) | |

| Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders, and somatoform disorders | |||

| Yes | 60 (5.9) | 999 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 949 (94.1) | 62 826 (98.4) | |

| Mood disorders | |||

| Yes | 34 (3.4) | 691 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 975 (96.6) | 63 134 (98.9) | |

| Mental retardation | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 12 (0) | 0.663 |

| No | 1009 (100) | 63 813 (100) | |

| Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders | |||

| Yes | 3 (0.3) | 20 (0) | 0.005 |

| No | 1006 (99.7) | 63 805 (100) | |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | |||

| Yes | 3 (0.3) | 48 (0.1) | 0.045 |

| No | 1006 (99.7) | 63 777 (99.9) | |

| Disorders of psychological development | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.1) | 16 (0) | 0.234 |

| No | 1008 (99.9) | 63 809 (100) | |

| Unspecific mental disorder | |||

| Yes | 4 (0.4) | 31 (0) | 0.002 |

| No | 1005 (99.6) | 63 794 (100) | |

Other delivery, including ‘Vaginal’, ‘Emergency caesarean section’, ‘Elective caesarean section’, and ‘Mode of delivery missing’.

Table 3.

Psychiatric disorders in relation to different modes of delivery

| Mode of delivery Vaginal delivery and emergency caesarean section n (%) | Elective caesarean section n (%) | Caesarean section on maternal request n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any psychiatric disorder | ||||

| Yes | 2084 (3.4) | 127 (4.4) | 101 (10) | <0.001 |

| No | 58 754 (96.6) | 2732 (95.6) | 908 (90) | |

| Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances | ||||

| Yes | 548 (0.9) | 22 (0.8) | 21 (2.1) | 0.001 |

| No | 60 290 (99.1) | 2837 (99.2) | 988 (97.9) | |

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | ||||

| Yes | 173 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | 12 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 665 (99.7) | 2850 (99.7) | 997 (98.8) | |

| Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | ||||

| Yes | 292 (0.5) | 18 (0.6) | 14 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 546 (99.5) | 2841 (99.4) | 995 (98.6) | |

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | ||||

| Yes | 33 (0.1) | 1 (0) | 6 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 805 (99.9) | 2858 (100) | 1003 (99.4) | |

| Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders, and somatoform disorders | ||||

| Yes | 935 (1.5) | 62 (2.2) | 60 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 59 903 (98.5) | 2797 (97.8) | 949 (94.1) | |

| Mood disorders | ||||

| Yes | 651 (1.1) | 38 (1.3) | 34 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 187 (98.9) | 2821 (98.7) | 975 (96.6) | |

| Mental retardation | ||||

| Yes | 9 (0) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0.007 |

| No | 60 829 (100) | 2856 (99.9) | 1009 (100) | |

| Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders | ||||

| Yes | 19 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 819 (100) | 2858 (100) | 1006 (99.7) | |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | ||||

| Yes | 43 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 0.018 |

| No | 60 795 (99.9) | 2854 (99.8) | 1006 (99.7) | |

| Disorders of psychological development | ||||

| Yes | 13 (0) | 9 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0.025 |

| No | 60 825 (100) | 2856 (99.9) | 1008 (99.9) | |

| Unspecific mental disorder | ||||

| Yes | 30 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 808 (100) | 2858 (100) | 1005 (99.6) | |

Having been diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder during the 5 years before delivery significantly increased the risk of giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request (aOR 2.5, 95% CI 2.0–3.2). The odds ratios were significant and increased for every psychiatric disorder, except ‘Mental retardation’ and ‘Disorders of psychological development’. The odds ratio for ‘Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders’ was non-significant after adjustment for the background variables listed in Table 1 and the prevalence of urinary tract infection, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes mellitus, and lung disease. The odds ratios decreased but remained significant for the other psychiatric disorders (Table 4). The largest confounding factor was age (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.4–1.9; data not shown). Adjustments were made because these variables differed significantly between cases and controls, and have previously been shown to be potential confounding factors.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for caesarean section on maternal request by psychiatric disorders

| Psychiatric disorder | Caesarean section on maternal request |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | aOR* | 95% CI | |

| Any psychiatric disorder | 3.1 | 2.5–3.8 | 2.5 | 2.0–3.2 |

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | 4.2 | 2.3–7.6 | 2.3 | 1.1–4.5 |

| Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | 2.9 | 1.7–5.0 | 2.6 | 1.4–4.8 |

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | 11.2 | 4.7–26.8 | 12.9 | 5.1–32.4 |

| Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders, and somatoform disorders | 4.0 | 3.0–5.2 | 3.1 | 2.3–4.2 |

| Mood disorders | 3.2 | 2.2–4.5 | 2.4 | 1.7–3.6 |

| Mental retardation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders | 9.5 | 2.8–32.1 | 6.0 | 1.3–27.1 |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | 4.0 | 1.2–12.7 | 1.9 | 0.4–8.0 |

| Unspecific mental disorder | 8.1 | 2.9–23.2 | 3.9 | 1.1–13.4 |

| Disorders of psychological development | 4.0 | 0.5–29.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances | 2.4 | 1.5–3.7 | 1.8 | 1.1–2.9 |

Adjusted for background variables: age, marital status, BMI, parents’ country of birth, working status, tobacco use, educational level, urinary tract infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and lung disease.

When comparing caesarean section on maternal request with vaginal delivery only, the results did not differ.

Discussion

Main findings

Psychiatric illness was found to be more common in primiparae giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request than among all other primiparae giving birth during this time period. The risk of giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request was significantly increased for women with almost all of the psychiatric disorders listed during the 5 years before delivery. All psychiatric disorders except ‘Mental retardation’, ‘Disorders of psychological development’, and ‘Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders’ increased the risk, but these diagnoses were rare.

The most common disorders among both cases and controls were ‘Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders and somatoform disorders’ (5.9 versus 1.6%), ‘Mood disorders’ (3.4 versus 1.1%). and ‘Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances’ (2.1 versus 0.9%). This is in line with earlier research in the general population,27 and among pregnant women.16 The prevalence of these disorders was significantly higher among cases than controls, and represents an increased burden of severe psychiatric illness among these women. Having been diagnosed with ‘Neurotic disorders, stress-related disorders and somatoform disorders’ increased the risk of giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request by 3.1, for ‘Mood disorders’ by 2.4, and for ‘Mental and behaviour disorder caused by use of psychoactive substances’ by 1.8, after adjusting for background variables.

As previous studies have indicated, FOC is associated with psychiatric illness, and may be the explanation for the higher prevalence of caesarean section on maternal request in women with severe psychiatric illnesses.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in our study population was lower than in earlier studies. A review of the 12–month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Europe found the estimated prevalence of anxiety disorders to be 14%, mood disorders to be 7.8%, and alcohol dependence to be 3.4%.27 A study conducted in Finland found the prevalence of psychiatric outpatient (9 versus 3.5%) and inpatient (5.2 versus 2%) care 5–12 years before pregnancy to be higher among women referred for FOC compared with women without FOC. They also found the percentage of women having had any psychiatric care 5–12 years before pregnancy to be 31.6% in women with FOC and 16.6% in controls.18 Andersson et al.16 found a similar percentage, with 14.1% of all pregnant women having a psychiatric diagnosis. In our study we found the prevalence of psychiatric outpatient care to be 5.9 versus 1.9%, and the prevalence of psychiatric inpatient care to be 6.2 versus 2%. The overall prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was 10% in women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request, and 3.5% in controls. These differences might be because Andersson16 used a questionnaire (PRIME–MD) to record psychiatric disorders, thereby including women with psychiatric disorders that had not necessarily been diagnosed, and therefore had not been registered in the NPR. The differences observed in the Finnish study might have arisen from a longer study period,18 and might also reflect the possibility that not all women with FOC give birth by caesarean section on maternal request. The study populations differed from ours in including multiparae and older women as well as immigrants. It is possible that psychiatric illness is more common in these groups.

It is difficult to compare the prevalence of psychiatric illness because studies use different definitions, such as 12–month prevalence, lifetime prevalence, and point prevalence. It is also difficult because studies define the women differently. Some studies have FOC as inclusion criteria, some define them by ‘preferred mode of delivery’, which might differ from actual mode of delivery, and some analyse all elective caesarean sections together, instead of isolating women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request.

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request also differed with respect to sociodemographic variables, which is in line with earlier research.4,5,7,15 Our study found these women to have higher BMIs and to more often be married, which has not been reported before. The women are also more often born outside of Sweden.15 These cultural differences were reflected in our study, as women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request more often had parents who were born outside of Scandinavia.

These women also gave birth at a younger age than the general population. The mean age of giving birth for the first time was 26 years, and the population mean during the same time period was 28 years. This was because we only included women born in 1973–1983, and giving birth during 2002–2004, thereby limiting the distribution of age.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. Our inclusion criteria limited the age distribution as well as excluding women born outside of Sweden. According to earlier studies women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request are more often older and born outside of Sweden.4,5,7,15 This might have limited our number of cases. These women might also represent a group with more psychiatric illness, making us underestimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Not all psychiatric disorders are treated and diagnosed in the psychiatric healthcare system, and are thereby not all registered in NPR. This renders our results primarily generalisable for women with severe psychiatric illness requiring care. The incomplete coverage of psychiatric care in NPR makes us underestimate the incidence of psychiatric disorders. The underestimation should be equally distributed among cases and controls, and should therefore not bias the results.

Another limitation is the lack of a clear definition for caesarean section on maternal request. We applied the diagnosis code O828 used in Sweden for women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request, labelled ‘caesarean section on psychosocial indication’; however, this could be a source of potential confounding because we have no information on whether the women actually requested a caesarean section. This difficulty applies for all data extracted from registers.

Strengths

A strength of this study is that we only investigated primiparae. In this way we avoided the potential influence of a previous negative birth experience, as well as the misclassification of caesarean section on maternal request in multiparae as ‘previous caesarean section’. By isolating women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request, as well as investigating the actual mode of delivery instead of the preferred mode of delivery, the results are valid for women who give birth by caesarean section on maternal request.

This was a register-based study with a nationwide sample. This is a major strength because we were able to investigate a large sample of women as well as link data from different registers with sociodemographic variables, psychiatric illness, as well as childbirth and pregnancy-related variables. The large sample of women as well as their nationwide distribution makes the results more generalisable.

Further studies should investigate a larger sample, thereby having more women with psychiatric disorders, and making it possible to draw conclusions for more subgroups. It should also include older women and women born outside of Scandinavia to make the results more generalisable.

Interpretation

This study adds to our knowledge about the characteristics of women giving birth by caesarean on maternal request. As previous studies have indicated, we have found evidence that these women suffer more often from severe psychiatric illness. This must be taken into account when deciding on mode of delivery; however, there is a lack of randomised controlled trials. Considering this, every woman must receive adequate support and be evaluated individually, especially regarding future reproduction, as this can be affected by having a caesarean section.28

Conclusion

Women giving birth by caesarean section on maternal request have a greater burden of psychiatric disease. Psychiatric disorders increased the risk of giving birth by caesarean section in the absence of medical indications. Our results highlight the complex factors associated with caesarean section on maternal request, and have important implications in a clinical setting.

Disclosure of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contribution to authorship

GS, EA, CL, and AJ had the original idea for the study. All authors planned the study. LM and MB analysed the data and drafted the article. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, revisions, and gave input at all stages of the study. All authors have approved the final version of the article for publication.

Details of ethics approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linkoping University, 2008-11-12. no. M 204–8.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from The County Council of Ostergotland, Sweden.

References

- 1.National Board of Health and Welfare,Centre for Epidemiology. 2005. Kejsarsnitt i Sverige 1990–2001 [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2005/2005-112-3]. Accessed 21 July 2013.

- 2.Gunnervik C, Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A, Ekholm Selling K, Josefsson A. Attitudes towards cesarean section in a nationwide sample of obstetricians and gynecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:438–44. doi: 10.1080/00016340802001711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florica M, Stephansson O, Nordström L. Indications associated with increased cesarean section rates in a Swedish hospital. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;92:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuglenes D, Aas E, Botten G, Øian P, Kristiansen IS. Why do some pregnant women prefer cesarean? The influence of parity, delivery experiences, and fear. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:45.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildingsson I, Radestad I, Rubertsson C, Waldenstrom U. Few women wish to be delivered by caesarean section. BJOG. 2002;109:618–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlström A, Nystedt A, Johansson M, Hildingsson I. Behind the myth – few women prefer caesarean section in the absence of medical or obstetrical factors. Midwifery. 2011;27:620–7. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kringeland T, Daltveit AK, Moller A. What characterizes women in Norway who wish to have a caesarean section? Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:364–71. doi: 10.1177/1403494809105027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieminen K, Stephansson O, Ryding EL. Women's fear of childbirth and preference for cesarean section–a cross-sectional study at various stages of pregnancy in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:807–13. doi: 10.1080/00016340902998436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldenstrom U, Hildingsson I, Ryding EL. Antenatal fear of childbirth and its association with subsequent caesarean section and experience of childbirth. BJOG. 2006;113:638–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiklund I, Edman G, Andolf E. Cesarean section on maternal request: reasons for the request, self-estimated health, expectations, experience of birth and signs of depression among first-time mothers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:451–6. doi: 10.1080/00016340701217913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiklund I, Edman G, Ryding EL, Andolf E. Expectation and experiences of childbirth in primiparae with caesarean section. BJOG. 2008;115:324–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG. 2009;116:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzoni A, Althabe F, Liu NH, Bonotti AM, Gibbons L, Sanchez AJ, et al. Women's preference for caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BJOG. 2011;118:391–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hildingsson I. How much influence do women in Sweden have on caesarean section? A follow-up study of women's preferences in early pregnancy. Midwifery. 2008;24:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiklund I, Edman G, Larsson C, Andolf E. Personality and mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1225–30. doi: 10.1080/00016340600839833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson L, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Wulff M, Bondestam K, åStröm M. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:148–54. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Gissler M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Mental health problems common in women with fear of childbirth. BJOG. 2011;118:1104–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. 2003. The Swedish medical birth register; a summary of content and quality [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10655/2003-112-3_20031123.pdf]. Accessed 24 September 2012.

- 19.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. 2009. Kvalitet och innehåll i patientregistret [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2009/2009-125-15]. Accessed 18 October 2012.

- 20.Statistics Sweden. A New Total Population Register System. More Possibilities and Better Quality. (Serial no. 2002:2) Örebro, Sweden: Statistics Sweden; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. 2012. Causes of death 2011 [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19001/2013-2-30.pdf]. Accessed 23 July 2013.

- 22.Statistics Sweden. 2005. Educational attainment of the population 2004 [ http://www.scb.se/statistik/UF/UF0506/2005A01/UF0506_2005A01_SM_UF37SM0501.pdf]. Accessed 22 July 2013.

- 23.Statistics Sweden. 2011. Multi-generation register 2010. A description of contents and quality [ http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/BE9999_2011A01_BR_BE96BR1102.pdf]. Accessed 22 July 2013.

- 24.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. 2010. The Swedish version of 10th revision of WHO's international classification of diseases [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-11-13]. Accessed 27 September 2012.

- 25.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. 2007. In-patient diseases in Sweden 1987–2006 [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/9326/2007-42-17_20074218.pdf]. Accessed 24 September 2012.

- 26.National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology. Translator ICD9 to ICD 10. [ http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/Documents/9TO10.pdf]. Accessed 21 October 2012.

- 27.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jonsson B, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–79. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Souza R, Arulkumaran S. To ‘C’ or not to ‘C’? Caesarean delivery upon maternal request: a review of facts, figures and guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:5–15. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]