Abstract

A constitutive activation of protein kinase B (AKT) in a hyper-phosphorylated status at Ser473 is one of the hallmarks of anti-EGFR therapy-resistant colorectal cancer (CRC). The aim of this study was to examine the role of cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α) on AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and cell proliferation in CRC cells with mutation in phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 was resistant to EGF stimulation in CRC cell lines of DLD-1 (PIK3CAE545K mutation) and HT-29 (PIK3CAP499T mutation). Over-expression of cPLA2α by stable transfection increased basal and EGF-stimulated AKT phosphorylation and proliferation in DLD-1 cells. In contrast, silencing of cPLA2α with siRNA or inhibition with Efipladib decreased basal and EGF-stimulated AKT phosphorylation and proliferation in HT-29. Treating animals transplanted with DLD-1 with Efipladib (10 mg/kg, i.p. daily) over 14 days reduced xenograft growth by >90% with a concomitant decrease in AKT phosphorylation. In human CRC tissue, cPLA2α expression and phosphorylation were increased in 63% (77/120) compared with adjacent normal mucosa determined by immunohistochemistry. We conclude that cPLA2α is required for sustaining AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and cell proliferation in CRC cells with PI3K mutation, and may serve as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of CRC resistant to anti-EGFR therapy.

Keywords: Cytosolic phospholipase A2α, AKT, Colorectal cancer, Efipladib

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females worldwide with over 1.2 million new cases annually [1]. Due to the lack of effective treatment for metastatic CRC, there are approximately 600,000 deaths annually [1]. Despite the improvement in the clinical outcome following the development of molecular targeted therapy against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [2], CRC with mutations of BRAF, RAS, PI3K or PTEN are resistant to anti-EGFR therapy [3, 4]. RAS and PIK3CA mutation increased protein kinase B (AKT) phosphorylation at Ser473 [5]. Phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 is required for tumor progression in colon cancer [6]. Therefore, a constitutive activation of AKT in a hyper-phosphorylated status at Ser473 is one of the hallmarks of anti-EGFR therapy-resistant CRC [7]. Hence, identification of pathways that are required for maintaining AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 in CRC is of clinical importance.

Previous studies have shown the involvement of prostaglandin and its producing enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) in CRC [8, 9]. The enthusiasm for the effectiveness of COX-2 inhibitor is hampered by its side effect due to the selective inhibition of COX enzymes. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) is a family of enzymes that catalyse the hydrolysis of fatty acid at the sn-2 position of glycerophospholipid on cell membranes [10]. Of the family members, cytosolic PLA2α (cPLA2α) is the only enzyme that catalyses the specific hydrolysis of arachidonic acid (AA) [10]. The cleaved free AA is converted to eicosanoids by the COX and lypoxygense (LOX) enzymes [10]. As the inhibition of cPLA2α reduces the supply of AA to both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, it may avoid the side effect of selective COX-2 inhibitors. Moreover, 5-LOX is over-expressed in CRC compared with normal colonic mucosa [11]. Blocking 5-LOX reduces CRC cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo [11]. Hence, we have evaluated the potential using cPLA2α as a therapeutic target for treatment of CRC. This paper describes the effect of ectopic expression, genetic silencing or pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α on AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo of CRC cells with constitutive activation of AKT due to gain-of-function mutations in PI3K, as well as cPLA2α expression and activation in human CRC tissues.

RESULTS

Over expression of cPLA2α elevates basal and EGF-stimulated phospho-AKT levels at Ser473 with parallel increase in proliferation of CRC cells with PIK3CAE545K mutation

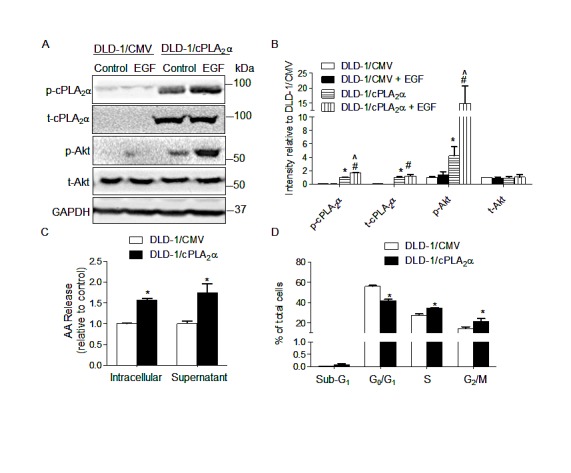

To determine the effect of over expression and activation of cPLA2α on AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and cell proliferation, DLD-1 cells (PIK3CAE545K) were stably transfected with cPLA2α-coding vector (DLD-1/cPLA2α) or empty vector (DLD-1/CMV). The ectopically expressed cPLA2α led to an increase in total (t-cPLA2α) and phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 (p-cPLA2α, Figure 1A and 1B), with a concomitant increase in arachidonic acid levels in the intracellular and extracellular (medium) compartments (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Overexpression of cPLAα increases p-AKT and cell proliferation in DLD-1 cells.

(A) Immunoblot in DLD-1 cells stably transfected with cPLA2α (DLD-1/cPLA2α) or empty vector (DLD-1/CMV) with or without EGF treatment (20 ng/mL, 30 min). (B) Densitometry quantification of (A). *P<0.05 vs. DLD-1/CMV, #P<0.05 vs. DLD-1/CMV+EGF, ^P<0.05 DLD-1/cPLA2α vs. DLD-1/cPLA2α+EGF, n=3. (C) Arachidonic acid concentration in intracellular compartments and the supernatant measured by Mass Spectrometer. *P <0.05 vs. DLD-1/CMV. (D) DNA content analysis by PI-Flow cytometry. *P <0.05 vs. DLD-1/CMV, n=3. All data was expressed as Mean ± SD.

Basal and EGF (final concentration 20 ng/mL, 30 min) stimulated p-AKT at Ser473 was increased 3.2-fold (Figure 1A: DLD-1/cPLA2α without EGF vs. DLD-1/CMV without EGF) and 9.5-fold (DLD-1/cPLA2α with EGF vs. DLD-1/CMV with EGF), respectively in DLD-1/cPLA2α compared with DLD-1/CMV cells (both P<0.001, Figure 1B). Levels of p-AKT at Ser473 were unchanged in the presence or absence of EGF stimulation in DLD-1/CMV cells (Figure 1A: DLD-1/CMV without EGF vs. DLD-1/CMV with EGF). However, the same dose of EGF elicited a distinct increase in p-AKT in DLD-1/cPLA2α cells (DLD-1/cPLA2α without EGF vs. DLD-1/cPLA2α with EGF, P<0.05). Levels of t-AKT were unaffected in both cell lines in the presence or absence of EGF stimulation. It is interesting to note that, similar to p-AKT at Ser473, p-cPLA2α at Ser505 levels remained unchanged in DLD-1/CMV cells in response to EGF stimulation (Figure 1A). However, EGF elicited a marked increase in p-cPLA2α at Ser505 in DLD-1/cPLA2α cells (P<0.05, Figure 1A and 1B), while the levels of t-cPLA2α remained unchanged. Cell cycle phase distribution analysis showed that the proportion of G1/G0 was lower, whereas S and G2/M were higher, in DLD-1/cPLA2α than DLD-1/CMV cells (all P<0.05, Figure 1D), with no significant change in the proportion of cells in sub-G1 phase.

Silencing of cPLA2α decreases EGF-stimulated phospho-AKT at Ser473 levels and proliferation in CRC cells with mutant PIK3CAP499T

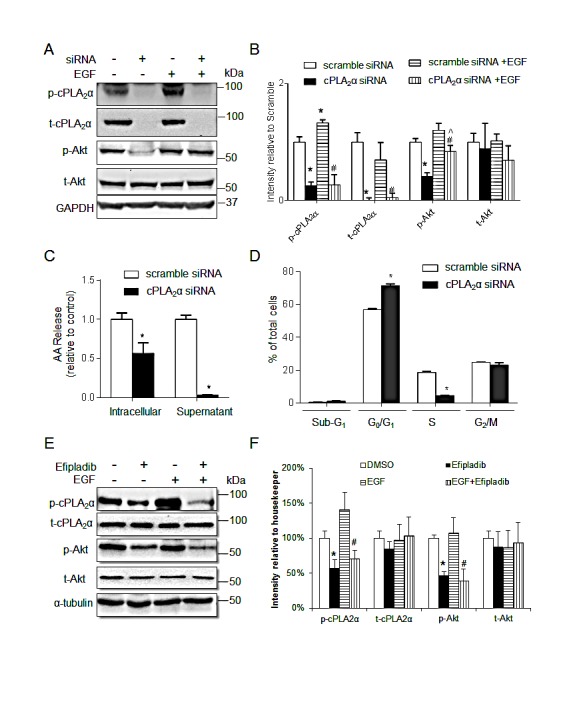

We next determined the effect of genetic silencing of cPLA2α with siRNA on p-AKT levels and cell proliferation. Transfection of HT-29 (PIK3CAP499T) with cPLA2α siRNA abolished the t-cPLA2α and p-cPLA2α protein levels (all P<0.001, Figure 2A and 2B), and significantly decreased both intracellular and extracellular content of arachidonic acid (both P<0.001, Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Silence of cPLAα decreases EGF-stimulated p-AKT and cell proliferation in HT-29 cells.

(A) immunoblot and (B) quantification of cPLA2α and AKT in cells transfected with cPLA2α siRNA or scramble control (10 nM for 72 h) with or without EGF treatment (20 ng/mL, 30 min). *P <0.05 vs. cells transfected with scramble control without EGF; #P <0.05 vs. cells transfected with scramble control with EGF. ^P <0.05 cPLA2α siRNA vs. cPLA2α siRNA+EGF. (C) Arachidonic acid concentration in the intracellular and supernatant compartments measured by Mass Spectrometry. *P <0.05 vs. cells transfected with scramble control. (D) DNA content analysis by PI-Flow cytometry. *P <0.05 vs. cells transfected with scramble control.; (E) Immunoblot of HT-29 cells treated with 25 μM Efipladib for 72 h and/or 20 ng/mL EGF for 30 min before harvesting. (F) Densitometry quantification. *P <0.05 vs. DMSO, #P <0.05 vs. DMSO+EGF, n=3. All data expressed as Mean ± SD.

Levels of p-AKT remained unchanged in response to EGF stimulation (final concentration 20 ng/mL, 30 min) in HT-29 (Figure 2A:scramble siRNA with EGF vs. scramble siRNA without EGF). However, Knockdown of cPLA2α deceased both basal and EGF stimulated p-AKT levels by 59% (Figure 2A: cPLA2αsiRNA without EGF vs. scramble siRNA without EGF) and 30% (cPLA2α siRNA with EGF vs. scramble siRNA with EGF), respectively, compared with the scrambled control (all P<0.05, Figure 2B). The levels of t-AKT were unchanged with or without EGF stimulation in the presence or absence of cPLA2α siRNA. It indicates that the constitutively-activated AKT as the results of PIK3CAP499T mutation could be inhibited by knockdown cPLA2α expression. Again, EGF treatment elicited an increase in p-cPLA2α (P<0.05) without affecting t-cPLA2α when endogenous cPLA2α was unperturbed (Figure 2A and 2B).

Next, we assessed the effect of transient knockdown of cPLA2α on cell cycle distribution. There was a clear increase in G1/G0 and corresponding decrease in S phase (all P<0.05, Figure 2D), with no significant change in the proportion of cells in sub-G1 phase following genetic silencing of cPLA2α. We then examined whether Efipladib (a new indole derived cPLA2α inhibitor [12, 13]) mimics the impact of cPLA2α siRNA and exerts the same action on AKT phosphorylation in HT-29 cells. Incubation of HT-29 cells with Efipladib (25 μM, 72 h) indeed decreased basal and EGF-stimulated p-AKT levels without affecting t-AKT (both P<0.05, Figure 2E and 2F). Taken together, targeting cPLA2α by genetic silencing or pharmacological inhibition supresses EGF-resistant AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and also inhibits cell proliferation in HT-29 cells harbouring mutation in PIK3CAP499T.

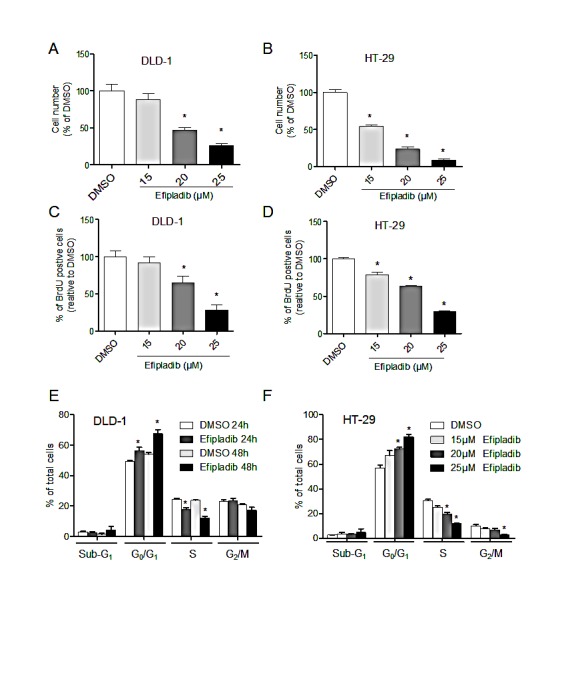

Pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α decreases cell proliferation in both DLD-1 and HT-29 cells

Since pharmacological blockade of cPLA2α with Efipladib effectively reduced basal and EGF-stimulated AKT phosphorylation, we determined the effect of Efipaldib on cell proliferation in unmodified parental DLD-1 (PIK3CAE545K) and HT-29 (PIK3CAP499T) cells. Inhibition of cPLA2α with Efipladib reduced cell number (P<0.05, Figure 3A and 3B) and BrdU incorporation (P<0.05, Figure 3C and 3D) in a dose-dependent manner in both DLD-1 and HT-29 cells. Efipladib treatment for 24-48 h blocked DLD-1 cell cycle progression as indicated by an accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 phase with a decrease in the proportion of cells in S phases (all P<0.05, Figure 3E). The decreased G2/M phase, however, did not reach statistical significance at 48 h. A similar effect on G0/G1 phase and S phases was noted in HT-29 cells treated with increasing dose of Efipladib after 72 h (all P<0.05, Figure 3F). The fraction of cells in G2/M was also decreased at the highest concentration of Efipladib (25 μM, P<0.05). We found no significant change in cell viability in the presence of Efipladib as assessed by sub-G1 (Figure 3E and 3F) and Trypan Blue exclusion (data not shown). Hence, consistent with effect of genetic silencing of cPLA2α, pharmacological blockade of cPLA2α resulted primarily in a cytostatic effect on CRC cells with PIK3CAE545K or PIK3CAP499Tmutations.

Figure 3. Pharmacological blockade of cPLAα by Efipladib results in decreased cell proliferation.

DLD-1 (A) or HT-29 cells (B) were plated in 96-well plates and treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or Efipladib for 72 h. The viable cell number was determined by the MTS assay. DLD-1 (C) or HT-29 (D) cells were plated in 6-well plates and treated with control (DMSO) or Efipladib for 72 h. BrdU was added for 3 h prior to harvesting. BrdU incorporation was determined by immunocytochemistry. Percentage of BrdU positive cells was determined as the average of 10 high-power fields (X40) per sample. *P <0.05 vs. vehicle-treated control, n=3. (E) DLD-1 cells were treated with Efipladib at 25 μM for 1 or 2 days, followed by staining with PI and subsequent analysis with flow cytometry. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle-treated control, n=3. (F) HT-29 cells were treated with Efipladib at indicated doses for 3 days, followed by PI-staining and DNA content analysis. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle-treated control, n=3. All data expressed as Mean ± SD.

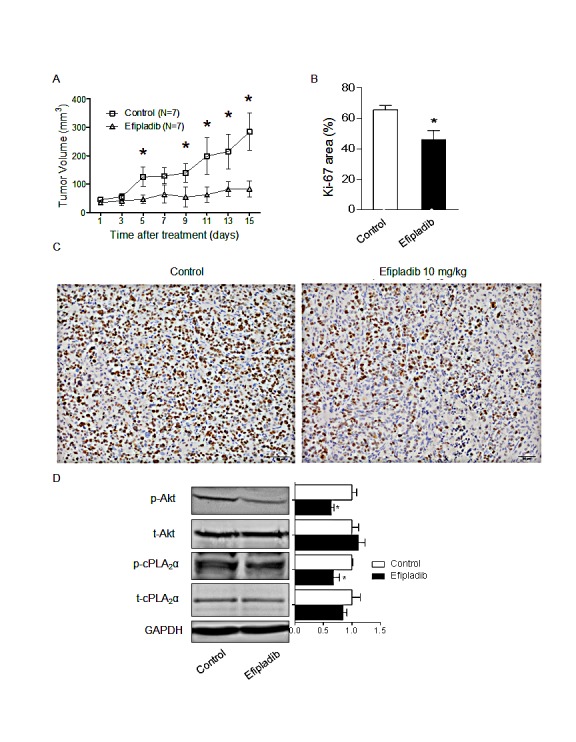

Pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α reduces p-AKT levels and xenograft growth in mice transplanted with DLD-1 cells

To determine if the marked decrease in p-AKT and cell proliferation in response to Efipladib can be recapitulated in animal, we treated mice carrying unmodified parental DLD-1 xenografts with Efipladib. In vehicle-treated control mice tumour volume increased 4.5-fold at day 14 compared to the day 1 (Figure 4A), but in the Efipladib–treated mice, there was only a 1.4-fold increase over 14 days (P<0.001 by two way ANOVA with repeat measurements). Further analysis at each time point revealed a significant difference in tumour volume as early as day 5 of Efipladib treatment (P<0.05, Figure 4A). Mouse body weights did not differ between the two groups. The percentage of Ki-67 positive cells and the levels of p-AKT and p-cPLA2α in xenografts were significantly reduced in Efipladib-treated mice compared with the vehicle-treated controls (all P<0.05, Figure 4B-D). The levels of t-AKT and t-cPLA2α remained unchanged. Hence, consistent with the in vitro effect of Efipladib on suppressing p-AKT and proliferation, pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α in vivo reduces markedly p-AKT levels and DLD-1 xenograft growth compared with vehicle-treated controls.

Figure 4. Pharmacological blockade of cPLAα by Efipladib impedes the growth of DLD-1 xenografts and decreases p-AKT levels in vivo.

(A) DLD-1 cells were inoculated into the flanks of nude mice. When xenograft tumours had reached 50 mm3 in volume, mice were randomised to control (n=7) or Efipladib treatment (7 mice/group) at a dose of 10 mg/kg i.p. daily for 14 days. Inhibition of tumour growth in the Efipladib-treated mice compared with the controls (p<0.001 by two way ANOVA with repeat measurement). *p<0.05 vs. control at the same day. (B) The fraction of Ki-67 positive cells was determined from the average number of positive cells in 10 high-power fields (×40). *p < 0.05 vs. control. (C) Xenografts were harvested, fixed and paraffin-embedded, and stained for Ki-67 by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 50 μm, magnification 200×. (D) Immunoblot of DLD-1 xenograft tumour and densitometry quantification. *p<0.05 vs. control, n=3. All data expressed as Mean ± SD.

The levels of cPLA2α and phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 are increased in colon cancer tissues

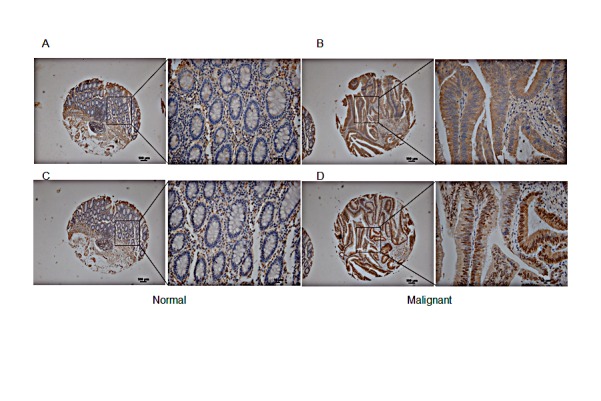

To determine the potential of cPLA2α as a therapeutic target, we examined cPLA2α protein levels in CRC specimens by immunohistochemistry. Compared with adjacent normal epithelial cells, an increase in the extent and/or intensity of immune reactive total cPLA2α in malignant epithelial cells was observed in 77/120 cases (64.2%, P<0.001, Figure 5A and 5B). Total cPLA2α was mainly located in the cytoplasm in both normal and cancer cells. Although total cPLA2α was also present in mesenchymal cells, there was no difference between normal and cancer tissues. Among the clinical parameters analysed, total cPLA2α levels were correlated with poor tumour differentiation (p=0.029, Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical analysis of total and phospho-cPLAα at Serin human CRC tissue array.

Inset AC: normal colon mucosa exhibited relatively low levels of total cPLA2α (A) and phospho-cPLA2α (C). Inset BD: CRC tissue had stronger total cPLA2α (B) and phospho-cPLA2α (D) in malignant epithelial cells. Low magnification 100×. Scale bar = 100 μm. High magnification 400×. Scale bar = 10 μm.

cPLA2α also contains several conserved serine residues as phosphorylation sites. Ser505 is the most studied and recognised site for phosphorylation of cPLA2α. Although phosphorylation is not necessary for basal enzyme activity, phosphorylation at Ser505 has shown to augment arachidonic acid release [14]. Immune reactive phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 was located in nucleus and cytoplasm in both normal and cancer cells, which is consistent with previous reports in other cell types [15, 16]. An increase in the extent and/or intensity of phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 was observed in malignant epithelial cells compared with adjacent normal epithelial cells in 76 out of 120 cases (63.3%, P<0.001, Figure 5C and 5D). Phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 was also present in mesenchymal cells but not significantly different between normal and cancer. There was no association between phospho-cPLA2α and any tumour characteristics (Supplemental Table 1). Taken together, cPLA2α expression and activation are increased in nearly two thirds of CRC compared with normal mucosa.

DISCUSSION

We provide three lines of evidence supporting the advantages of targeting cPLA2α in colorectal cancer.

Firstly, we have systematically investigated the role of cPLA2α in regulation of AKT phosphorylation by ectopic expression, genetic silencing and pharmacological inhibition in CRC cell lines with a constitutive action of AKT at Ser473 both in vitro and in vivo. Ectopic expression of cPLA2α increases basal and EGF-stimulated p-AKT levels. It is interesting to note that without manipulation of cPLA2α, AKT phosphorylation does not increase in response to EGF stimulation in both CRC cell lines. This is consistent with the report that constitutively-activated AKT renders cancer cells resistant to manipulation by growth factors [17]. However, a marked increase in AKT phosphorylation following EGF stimulation is noted when cPLA2α levels are increased by ectopic expression in DLD-1 cells. In contrast, genetic silence or pharmacological blockade of cPLA2α decreases basal and EGF-stimulated p-AKT levels in HT-29, which is another CRC cell line harbouring PI3K mutations. Same as DLD-1, p-AKT levels in HT-29 cells are resistant to EGF stimulation. Together with the effect of efipladib on p-AKT in vivo, these findings suggest that cPLA2α contributes to basal and EGF-stimulating AKT phosphorylation in CRC cells containing PI3K mutations. It is interesting to mention that we have shown recently that genetic silence or pharmacological blocking of cPLA2α decrease phospho-AKT at Ser473 in prostate cancer cells [18]. Hence, the link of cPLA2α to AKT appears to be a phenomenon not just limited to colon cancer cell lines.

The mechanism(s) by which cPLA2α exerts its action on AKT phosphorylation remains to be elucidated. Based on the significant change in AA concentration in response to cPLA2α manipulations, cPLA2α may exert its action on AKT via AA and/or its product eicosanoids [19]. Eicosanoid receptors can connect to PI3K-AKT pathway via heterotrimeric G proteins [20]. PGE2 may also be able to transactivate EGFR in CRC cells including HT-29 [21, 22]. As the decrease in proliferation of HT-29 cells by EGFR inhibitor could be abolished in the presence of PGE2 [23], the possible action site downstream of EGFR cannot be excluded. Furthermore, COX-2 inhibitor has been shown to increase in PTEN expression [24], which could be another mechanism for impinging on AKT. Further study is also needed to determine if cPLA2α can affect basal and EGF stimulated other oncogenic pathways such as ERK/MAPK.

Another interesting finding from our study is the phosphorylation of cPLA2α at Ser505, which is known to increase the AA-releasing activity [14, 25]. Previous studies have shown an increase in cPLA2α phosphorylation in mammalian cells by EGF [26, 27]. We found in the present study that EGF treatment increases phosphorylation of cPLA2α at Ser505 in both DLD-1 and HT-29 cells. Activation of RAS signalling by mutation or over-expression has been shown to induce PGE2 secretion in colon cancer [22, 28, 29]. We reported recently that AKT plays a role in stabilising cPLA2α protein in prostate cancer cells [30]. Hence, it appears that a self-perpetuating loop consisting of AKT and cPLA2α is present in CRC and maybe other type of cancer cells.

Secondly, the present study has provided evidence for the first time that pharmacological blockade of cPLA2α decreases cell proliferation of CRC cell lines with PI3K mutation both in vitro and in vivo. The presence of somatic PI3K mutations causing constitutive activation of AKT have been regarded as one of the predictive markers of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy [3, 4]. Therefore inhibition of constitutive activated AKT could be one of the strategies to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Our results suggest that in addition to inhibiting AKT phosphorylation at Ser473, targeting cPLA2α by siRNA or inhibitor can also retard cell-cycle progression and inhibit cell proliferation in CRC cells harbouring PI3K mutations. Similar to Efipladib (an inhibitor of fatty acid cleavage), Cerulenin (a fatty acid synthase inhibitor) decreased AKT phosphorylation at Ser473, enhanced antitumor activity of oxaliplatin in human colon cancer cells [31], and suppressed liver metastasis of colon cancer in mice [32]. However, it is worth to mention that two published in vivo studies of cPLA2α in intestine or colon tumor have yielded inconsistent results. While cross-breeding of Apcmin/+ mice with cPLA2α knockout suppresses intestine tumorigenesis [33], knockout of cPLA2α enhances azoxymethane-induced tumorigenesis in colon [34]. Hence, it is likely that azoxymethane-induced CRC may involve signalling pathways that are different from those in Apcmin/+ mice and DLD-1 cell xenograft. The prospective of targeting cPLA2α is further encouraged by the report that cPLA2α knockout mice exhibit a relatively normal phenotype [35].

Thirdly, cPLA2α protein is over-expressed and hyper-phosphorylated at Ser505 in ~60% of colon cancer cases. The mRNA and protein levels of cPLA2α have been examined in CRC specimens previously. RT-PCR [36, 37], immunoblot [38] or immunohistochemistry [39-41] revealed an increased cPLA2α in CRC specimens, except two studies conducted by the same group reported a low cPLA2α expression in CRC compared to normal mucosa by immunohistochemistry [42, 43]. In the present study, we examined for the first time the levels of phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505. Although phosphorylation at Ser505 is not necessary for basal enzyme activity, phosphorylation at Ser505 has shown to augment AA release [14, 25]. In correlation with total cPLA2α, phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 was clearly increased in near two-thirds of the 120 CRC specimens compared with adjacent normal mucosa. As both total and phospho-cPLA2α have increased in CRC, it is possible that the increase in phospho-cPLA2α results from the increase in total cPLA2α expression. Consistent with reports that activated cPLA2α translocates to the nucleus following stimulation with calcium ionophore or leukotriene D4 in CRC cells [44], we notice that the phospho-cPLA2α is present in nucleus as well, whereas total cPLA2α is confined in cytoplasm.

Our study suggests that poorly differentiated tumours, which is associated with unfavourable prognosis [45], are more likely having high cPLA2α expression. Two studies have shown that the expression of cPLA2α in CRC is correlated with VEGF expression but fail to predict disease-free survival and overall survival [40, 41]. cPLA2α gene polymorphisms has been shown to be associated with patients of familial adenomatous polyposis [46]. Since prognostic data of the TMA used in our study are not available, further studies are needed to determine the prognostic value of cPLA2α in CRC.

In summary, cPLA2α plays a critical role in regulation of AKT phosphorylation and cell proliferation in colon cancer cells in which PIK3CA has a gain-function mutation. We propose that the cPLA2α is a potential therapeutic target for treatment of colon cancer that are resistant to anti-EGFR therapy in the results of constitutive activation of AKT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and Reagents

The human colon cancer cell lines DLD-1 (Cat. #: CCL-221, PIK3CAE545K,) and HT-29 (Cat. #: HTB-38, PIK3CAP499T) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), and maintained in RPMI 1640 and DMEM, respectively, at 37°C in a humidified environment of 5% CO2. The medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS, ICN Biomedical, Irvine, CA) and all experimental cells were mycoplasma-negative. The expression plasmid pCMV6 carrying a full-length cPLA2α cDNA was purchased from Origene Technologies (Rockville, MD). Analytically pure Efipladib was synthesized at Sanmar Chemical, India. Antibodies against cPLA2α (Cat. #: SC-454) and phospho-cPLA2α at Ser505 (Cat. #: SC-34391), AKT (Cat. #: SC-8312) and phospho-AKT at Ser473 (Cat. #: SC-7985) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX); Anti-Ki-67 (Cat. #: RM-9106) was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Scoresby, VIC, Australia); Human EGF (Cat. #: E9644), BrdU (Cat. #: B5002), propidium iodide (Cat. #: P4170), antibody against BrdU (Cat. #: B8434) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). MTS (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay) was from Promega (Madison, WI).

Ectopic expression and genetic silence of cPLA2α

Expression vector containing pCMV-cPLA2α or empty vector was stably transfected into DLD-1 cells using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). After 1 day of transfection, media was replenished with fresh medium containing selection antibiotic G418 at 1 mg/mL and cells were allowed to grow for 10 days. Isolated colonies were cultured in the presence of G418 (400 μg/mL). Two clones (Clone 15 and 18) were used for this study. Both show an increase in p-AKT. cPLA2α siRNA (TTG AAT TTA GTC CAT ACG AAA) and scramble control (GAA TTT CAA ACT CGA TAT AGT) were transfected into cells (10 nM siRNA duplexes) using HiPerfect Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN, Santa Clarita, CA) as described previously [16].

Arachidonic acid release assay

Fatty acids were extracted from isolated cell pellets or culture media as described by Norris and Dennis [47]. A Xevo-Triple quadruple mass spectrometer (Waters, Micromass, UK) coupled to a Phenomenex Kinetex 1.7 μm C18 100A (2.1×150 mm) was used for arachidonic acid analysis. Standard curves were constructed using linear regression of the normalised peak areas of the analyte over internal standard (heptadecanoic acid) against the corresponding nominal concentrations of the arachidonic acid (See Supplemental method).

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3 carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) assay

CRC cells were plated in triplicate in 96 well plates. After 24 h, cells were incubated with Efipladib or DMSO (vehicle control) in 10% FCS-containing medium for 72 h prior to MTS assay. Stably transfected DLD-1 cells were grown in 10% FCS-containing RPMI 1640 for up to 4 days followed by MTS assay. The MTS assay was conducted as described previously [16]. Cell viability was independently monitored by Trypan Blue (Sigma-Aldrich) exclusion in parallel experiments.

Cell cycle analysis

CRC cells were plated in triplicate in 6-well plates. After 24 h, cells adherent to plates were exposed to the indicated treatments. Cells were harvested, fixed in 70% v/v ice-cold ethanol, and incubated with propidium iodide (20 μg/mL) and RNase A (100 μg/mL) for 1 h in 37°C incubator. Cells containing propidium iodide-stained DNA were then assessed using FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Australia), and the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle was analysed using Flowjo v8.0 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

BrdU incorporation

CRC cells were incubated with BrdU at 10 μM in culture medium for 3 h before harvesting. Cells were then trypsinized, fixed in 10% v/v formalin, clotted in agarose gel, and processed for paraffin blocks. Sections of 5 μm thickness were cut and incubated at 60°C for 1 h, deparaffinized in xylene, re-hydrated in graded ethanol and distilled water, and subjected to antigen retrieval in Tris–EDTA solution using a microwave oven. Thereafter, the sections were treated with 2N HCl, blocked with 10% v/v house serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with anti-BrdU antibody overnight at 4°C. After being rinsed in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20, the sections were sequentially labelled with a biotinylated secondary antibody and a Vectastain ABC kit from Vector Laboratories. Thereafter, the immunolabelling was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride from Dako. Sections were scanned and analysed with an automated cellular imaging system (ACIS III, Dako, Denmark). The number of both BrdU-positive and negative cells over 10 randomly selected fields was determined and expressed as a percentage of positive cells in total number of cells.

Xenografts assay

DLD-1 cells (2×106) were implanted s.c. in the right flanks of 6 week male nude mice. Mice were randomly distributed into two groups once the tumour size reached 50 mm3 (7 mice/group). One treated with 200 μL of 20% v/v DMSO in PBS i.p. daily (as vehicle control); the other treated with Efipladib (10 mg/kg, i.p. daily) dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in PBS. Tumour growth was assessed every other day by caliper measurement of tumour diameter in the longest dimension (L) and at right angles to that axis (W). Tumour volume was estimated by the formula, L ×W ×W/2. Mice were sacrificed after 14 days of treatment and tumours were excised and the tissue distributed in two halves designated for Ki-67 immunostaining and immunoblotting. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Shanghai Jiao-Tong University).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer-1 (20 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1% v/v/Triton X-100, 2.5 mmol/L sodium PPi, 1 mmol/L h-glycerolphosphate), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete, Roche Diagnostics, Australia). Xenografts were excised from the hosts, homogenised in RIPA buffer-2 (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 1% w/v sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% w/v SDS) supplemented with the same protease inhibitor. Protein concentration was quantified using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cell lysates (50-100 μg protein) were separated on 8-10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane; membranes were blocked with 5% w/v low fat skim milk in PBS containing 0.1% v/v Tween 20 for 1 h. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C, followed by washing then probing with appropriate secondary antibodies coupled with peroxide and detected by enhanced chemiluminesence (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Gel-pro analysis v6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used for densitometric scanning and quantification.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue arrays were obtained from Outdo Biotech (Shanghai, China) with 120 individual cases of CRC and adjacent non-cancerous colon tissue from the same individual. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using a DAKO EnVision+ System HRP as described previously [48]. An antibody raised in rabbit against cPLA2α (SC-438, 1:400 v/v) was left overnight at 20°C, an antibody in rabbit against phospho-cPLA2α (SC-34391-p, 1:150 v/v) was applied at 37°C for 2 h. For Ki-67 immunostaining in xenograft recovered from mice, anti-Ki-67 was applied at 37°C for 2 h and purified rabbit-IgG (Dako, 1:60 v/v) was used as an isotype control.

Imaging evaluation

cPLA2α immunostaining was assessed in a blinded manner using a light microscope (Olympus BX-50). The extent of staining was graded as 0 (<1%), 1 (1–20%), 2 (20–50%), 3 (50-75%) and 4 (>75%) in at least three independent fields using the same sample. The intensity of staining was assessed as: 0 (no staining), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), and 3 (strong). The final score (range from 0 to 12) was obtained by multiplying the extent of staining with the intensity, and were defined as negative (0-3), + (4-6), ++ (7-9) and +++ (10-12). The images were acquired by software NIS-Elements F 3.0 (Nikon). The proportion of Ki-67 positive cells was quantified with ImageJ v4.2 (NIH).

Statistical analysis

The statistical software SPSS version 14.0 was used for analysis. The scores of total and phospho-cPLA2α levels in CRC tissue were analysed by Wilcoxon signed rank test. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to test whether the levels of cPLA2α and phospho-cPLA2α differ in gender, age, or M stage. Gamma regression was used to test the relationship between cPLA2α and T, N, TNM stage or differentiation. In vitro data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests. Xenograft growth was compared between groups by fitting a repeated measures covariate model, where the actual time measurements were viewed as a covariate. Two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL AND TABLE

Acknowledgments

Dr. Paul Witting (Department of Pathology, University of Sydney) is kindly thanked for his careful reading of the manuscript prior to submission. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81172324, No.81101585, No.81101649, No.91229106, No.81272749), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No.10jc1411100, No.09DZ1950100, No.09DZ2260200, No.12XD1403700, and No.12PJ1406300), Chinese Scholar Council (Z. Zheng), Sydney Medical School Foundation, The University of Sydney (Q. Dong) and The University of Western Sydney Internal Research Grant (Q. Dong).

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviation

- AA

arachidonic acid

- AKT

protein kinase B

- cPLA2á

cytosolic phospholipase A2á

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu E. An update on the current and emerging targeted agents in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Fiore F, Sesboue R, Michel P, Sabourin JC, Frebourg T. Molecular determinants of anti-EGFR sensitivity and resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(12):1765–1772. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankaran V, Obel J, Benson AB., 3rd Predicting response to EGFR inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer: current practice and future directions. Oncologist. 2010;15(2):157–167. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oda K, Okada J, Timmerman L, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Stokoe D, Shoji K, Taketani Y, Kuramoto H, Knight ZA, Shokat KM, McCormick F. PIK3CA cooperates with other phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway mutations to effect oncogenic transformation. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):8127–8136. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh N, Semba S, Ito M, Takeda H, Kawata S, Yamakawa M. Phosphorylation of Akt/PKB is required for suppression of cancer cell apoptosis and tumor progression in human colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94(12):3127–3134. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scartozzi M, Giampieri R, Maccaroni E, Mandolesi A, Biagetti S, Alfonsi S, Giustini L, Loretelli C, Faloppi L, Bittoni A, Bianconi M, Del Prete M, Bearzi I, Cascinu S. Phosphorylated AKT and MAPK expression in primary tumours and in corresponding metastases and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients receiving irinotecan-cetuximab. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eberhart CE, Coffey RJ, Radhika A, Giardiello FM, Ferrenbach S, DuBois RN. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenhough A, Smartt HJ, Moore AE, Roberts HR, Williams AC, Paraskeva C, Kaidi A. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(3):377–386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh M, Tucker DE, Burchett SA, Leslie CC. Properties of the Group IV phospholipase A2 family. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45(6):487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melstrom LG, Bentrem DJ, Salabat MR, Kennedy TJ, Ding XZ, Strouch M, Rao SM, Witt RC, Ternent CA, Talamonti MS, Bell RH, Adrian TA. Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase in colon polyps and cancer and the effect of 5-LOX inhibitors in vitro and in a murine model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(20):6525–6530. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKew JC, Lee KL, Shen MW, Thakker P, Foley MA, Behnke ML, Hu B, Sum FW, Tam S, Hu Y, Chen L, Kirincich SJ, Michalak R, Thomason J, Ipek M, Wu K, et al. Indole cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51(12):3388–3413. doi: 10.1021/jm701467e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKew JC, Lee KL, Shen MW, Thakker P, Foley MA, Behnke ML, Hu B, Sum FW, Tam S, Hu Y, Chen L, Kirincich SJ, Michalak R, Thomason J, Ipek M, Wu K, et al. Indole cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha inhibitors: discovery and in vitro and in vivo characterization of 4-{3-[5-chloro-2-(2-{[(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)sulfonyl]amino}ethyl)-1-(dipheny lmethyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]propyl}benzoic acid, efipladib. J Med Chem. 2008;51(12):3388–3413. doi: 10.1021/jm701467e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker DE, Ghosh M, Ghomashchi F, Loper R, Suram S, John BS, Girotti M, Bollinger JG, Gelb MH, Leslie CC. Role of phosphorylation and basic residues in the catalytic domain of cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha in regulating interfacial kinetics and binding and cellular function. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9596–9611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807299200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorovetz M, Baekelandt M, Berner A, Trope CG, Davidson B, Reich R. The clinical role of phospholipase A2 isoforms in advanced-stage ovarian carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;103:831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel MI, Singh J, Niknami M, Kurek C, Yao M, Lu S, Maclean F, King NJ, Gelb MH, Scott KF, Russell PJ, Boulas J, Dong Q. Cytosolic phospholipase A2-alpha: a potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(24):8070–8079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalaany NY, Sabatini DM. Tumours with PI3K activation are resistant to dietary restriction. Nature. 2009;458(7239):725–731. doi: 10.1038/nature07782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua S, Yao M, Vignarajan S, Witting P, Hejazi L, Gong Z, Teng Y, Niknami M, Assinder S, Richardson D, Dong Q. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 sustains pAKT, pERK and AR levels in PTEN-null/mutated prostate cancer cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2013;1831(6):1146–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linkous A, Yazlovitskaya E. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 as a mediator of disease pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12(10):1369–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castellone MD, Teramoto H, Williams BO, Druey KM, Gutkind JS. Prostaglandin E2 promotes colon cancer cell growth through a Gs-axin-beta-catenin signaling axis. Science. 2005;310(5753):1504–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo IL, Pavelka M, Baatar D, Tarnawski AS. Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8(3):289–293. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Salihi MA, Ulmer SC, Doan T, Nelson CD, Crotty T, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM, Topham MK. Cyclooxygenase-2 transactivates the epidermal growth factor receptor through specific E-prostanoid receptors and tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. Cell Signal. 2007;19(9):1956–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisslov L, Hadad N, Rosengraten M, Levy R. HT-29 human colon cancer cell proliferation is regulated by cytosolic phospholipase A(2)alpha dependent PGE(2)via both PKA and PKB pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(9):1224–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu EC, Chai J, Tarnawski AS. NSAIDs activate PTEN and other phosphatases in human colon cancer cells: novel mechanism for chemopreventive action of NSAIDs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320(3):875–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das S, Rafter JD, Kim KP, Gygi SP, Cho W. Mechanism of group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A(2) activation by phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(42):41431–41442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin LL, Lin AY, Knopf JL. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is coupled to hormonally regulated release of arachidonic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(13):6147–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Weng YI, Simonyi A, Krugh BW, Liao Z, Weisman GA, Sun GY. Role of PKC and MAPK in cytosolic PLA2 phosphorylation and arachadonic acid release in primary murine astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2002;83(2):259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CH, Shih YW, Chang CH, Ou TT, Huang CC, Hsu JD, Wang CJ. EP4 upregulation of Ras signaling and feedback regulation of Ras in human colon tissues and cancer cells. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84(9):731–740. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smakman N, Kranenburg O, Vogten JM, Bloemendaal AL, van Diest P, Borel Rinkes IH. Cyclooxygenase-2 is a target of KRASD12, which facilitates the outgrowth of murine C26 colorectal liver metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vignarajan S, Xie C, Yao M, Sun Y, Simanainen U, Sved P, Liu T, Dong Q. Loss of PTEN stabilizes the lipid modifying enzyme cytosolic phospholipase A(2)alpha via AKT in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5(15):6289–6299. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiragami R, Murata S, Kosugi C, Tezuka T, Yamazaki M, Hirano A, Yoshimura Y, Suzuki M, Shuto K, Koda K. Enhanced antitumor activity of cerulenin combined with oxaliplatin in human colon cancer cells. International journal of oncology. 2013;43(2):431–438. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murata S, Yanagisawa K, Fukunaga K, Oda T, Kobayashi A, Sasaki R, Ohkohchi N. Fatty acid synthase inhibitor cerulenin suppresses liver metastasis of colon cancer in mice. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(8):1861–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong KH, Bonventre JC, O'Leary E, Bonventre JV, Lander ES. Deletion of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) suppresses Apc(Min)-induced tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(7):3935–3939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051635898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilsley JN, Nakanishi M, Flynn C, Belinsky GS, De Guise S, Adib JN, Dobrowsky RT, Bonventre JV, Rosenberg DW. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 deletion enhances colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 2005;65(7):2636–2643. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niknami M, Patel M, Witting PK, Dong Q. Molecules in focus: Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2009;41(5):994–997. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dimberg J, Samuelsson A, Hugander A, Soderkvist P. Gene expression of cyclooxygenase-2, group II and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in human colorectal cancer. Anticancer Research. 1998;18(5A):3283–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osterstrom A, Dimberg J, Fransen K, Soderkvist P. Expression of cytosolic and group X secretory phospholipase A(2) genes in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Letters. 2002;182(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soydan AS, Tavares IA, Weech PK, Tremblay NM, Bennett A. High molecular weight phospholipase A2: its occurrence and quantification in human colon cancer and normal mucosa. Advances in Experimental Medicine & Biology. 1997;400A:31–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5325-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panel V, Bo, x00Eb, lle P-Y, Ayala-Sanmartin J, Jouniaux A-M, Hamelin R, Masliah J, lle, Trugnan G, Fl, x00E, jou J-F, ois, Wendum D. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 expression in human colon adenocarcinoma is correlated with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and contributes to prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Letters. 2006;243(2):255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo YS, Lim SC, Kim KJ. Prognostic significance of cytosolic phospholipase A2 expression in patients with colorectal cancer. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80(6):397–403. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.80.6.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim SC, Cho H, Lee TB, Choi CH, Min YD, Kim SS, Kim KJ. Impacts of cytosolic phospholipase A2, 15-prostaglandin dehydrogenase, and cyclooxygenase-2 expressions on tumor progression in colorectal cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(5):692–699. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.5.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong M, Guda K, Nambiar PR, Rezaie A, Belinsky GS, Lambeau G, Giardina C, Rosenberg DW. Inverse association between phospholipase A2 and COX-2 expression during mouse colon tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24(2):307–315. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong M, Johnson M, Rezaie A, Ilsley JN, Nakanishi M, Sanders MM, Forouhar F, Levine J, Montrose DC, Giardina C, Rosenberg DW. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 levels correlate with apoptosis in human colon tumorigenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(6):2265–2271. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parhamifar L, Jeppsson B, Sj, x00F, lander A. Activation of cPLA2 is required for leukotriene D4-induced proliferation in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 1988;26(11):1988–1998. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park YJ, Park KJ, Park JG, Lee KU, Choe KJ, Kim JP. Prognostic factors in 2230 Korean colorectal cancer patients: analysis of consecutively operated cases. World J Surg. 1999;23(7):721–726. doi: 10.1007/pl00012376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umeno J, Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Kukita Y, Tahira T, Yanaru-Fujisawa R, Nakamura S, Arima H, Hirahashi M, Hayashi K, Iida M. Impact of group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 gene polymorphisms on phenotypic features of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(3):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0808-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norris PC, Dennis EA. Omega-3 fatty acids cause dramatic changes in TLR4 and purinergic eicosanoid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(22):8517–8522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200189109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuen HF, Chan YP, Chan KK, Chu YY, Wong ML, Law SY, Srivastava G, Wong YC, Wang X, Chan KW. Id-1 and Id-2 are markers for metastasis and prognosis in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(10):1409–1415. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.