Abstract

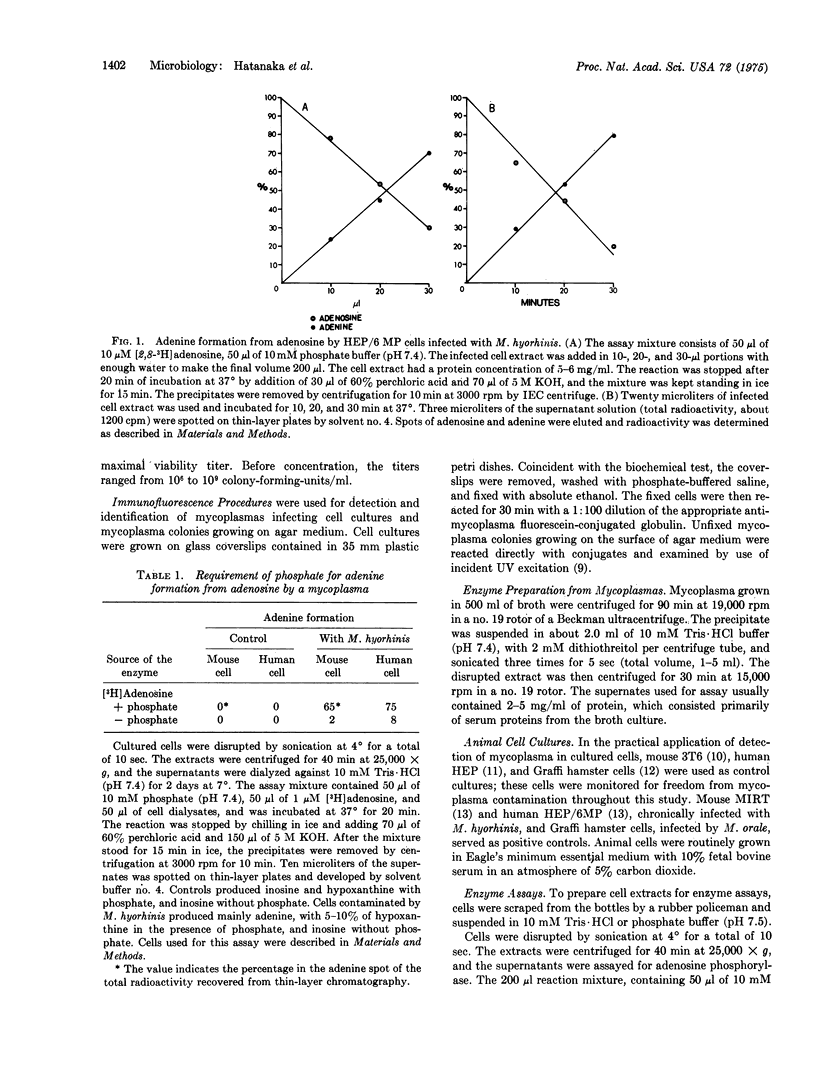

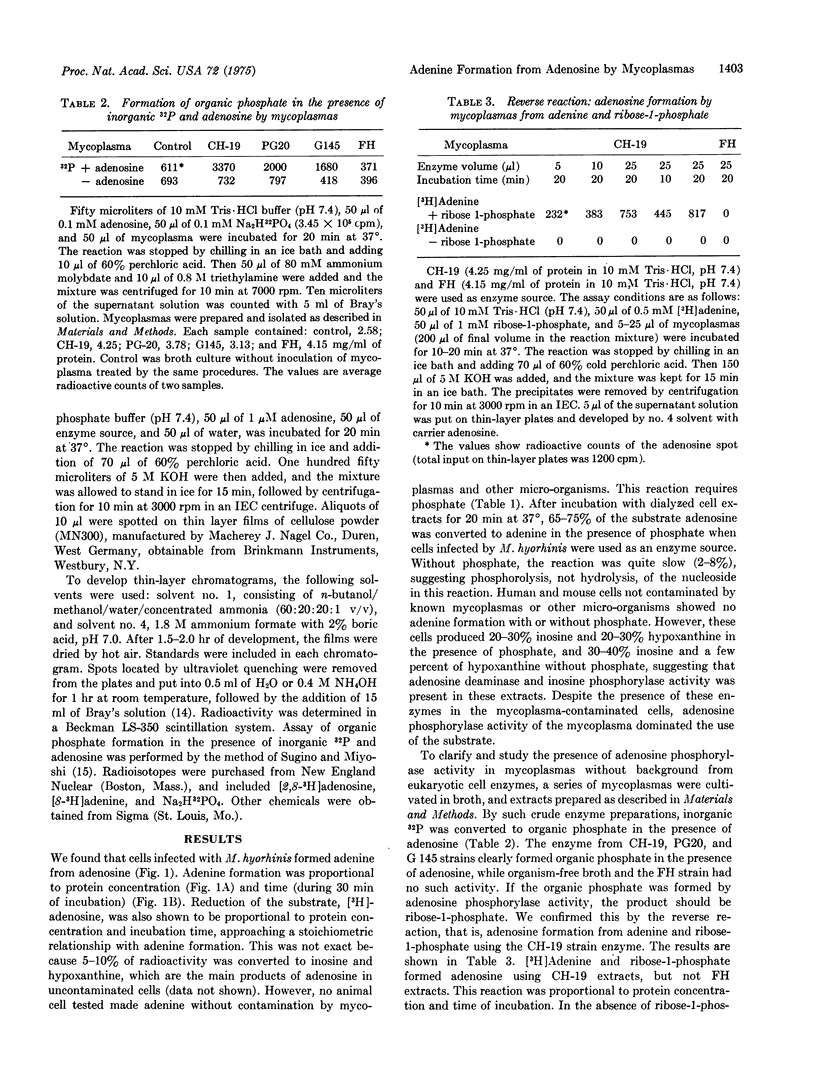

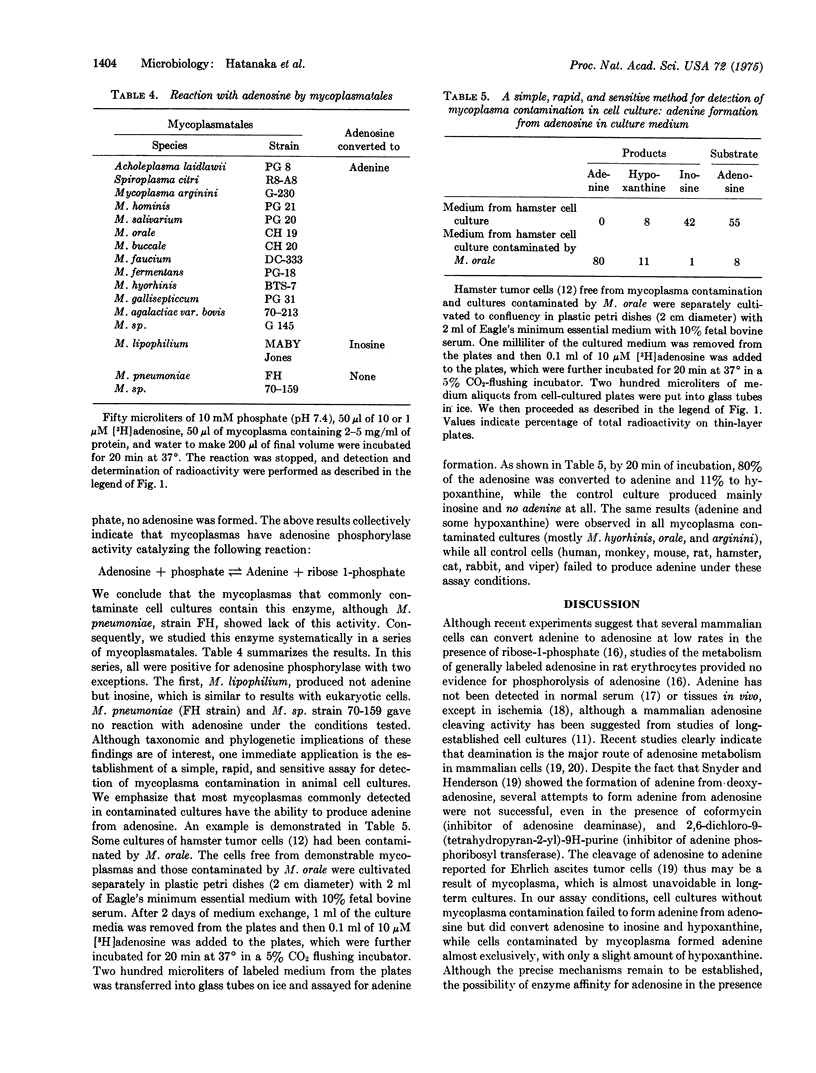

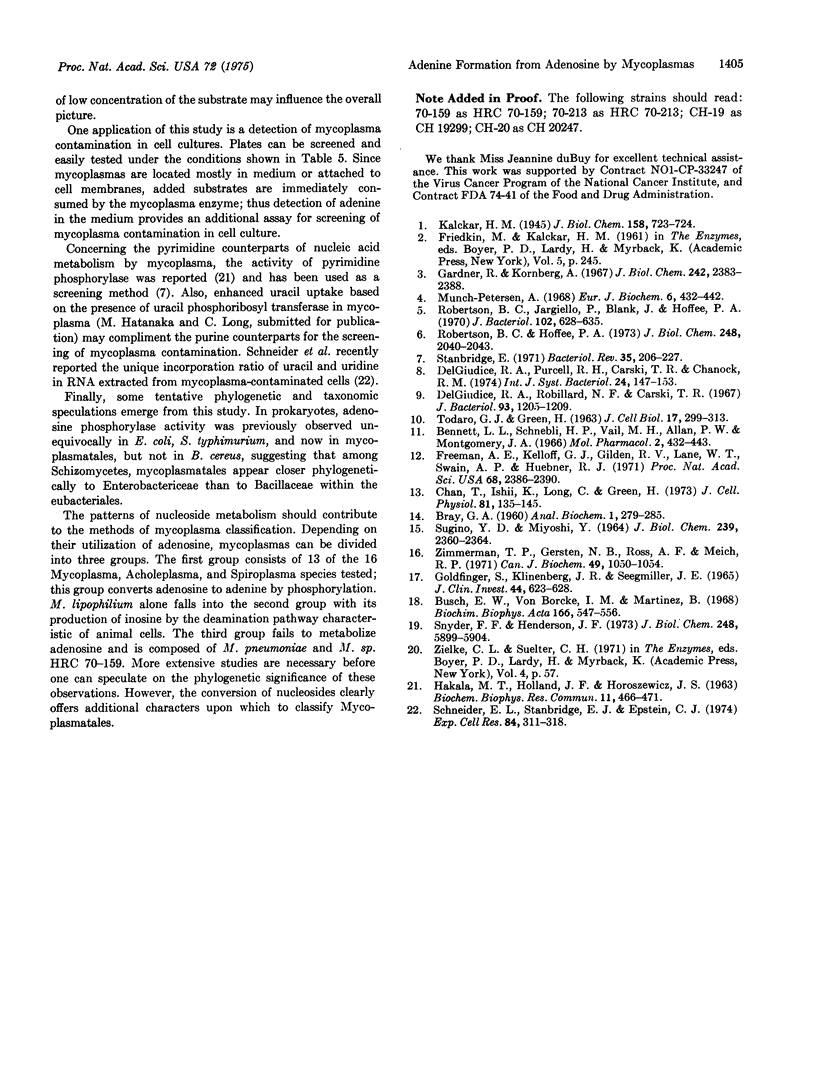

Mammalian cells have enzymes to convert adenosine to inosine by deamination and inosine to hypoxanthine by phosphorolysis, but they do not possess the enzymes necessary to form the free base, adenine, from adenosine. Mycoplasmas grown in broth or in cell cultures can produce adenine from adenosine. This activity was detected in a variety of mycoplasmatales, and the enzyme was shown to be adenosine phosphorylase. Adenosine formation from adenine and ribose 1-phosphate, the reverse reaction of adenine formation from adenosine, was also observed with the mycoplasma enzyme. Adenosine phosphorylase is apparently common to the mycoplasmatales but it is not universal, and the organisms can be divided into three groups on the basis of their use of adenosine as substrate. Thirteen of 16 Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, and Siroplasma species tested exhibit adenosine phosphorylase activity. M. lipophilium differed from the other mycoplasmas and shared with mammalian cells the ability to convert adenosine to inosine by deamination. M. pneumoniae and the unclassified M. sp. 70-159 showed no reaction with adenosine. Adenosine phosphorylase activity offers an additional method for the detection of mycoplasma contamination of cells. The patterns of nucleoside metabolism will provide additional characteristics for identification of mycoplasmas and also may provide new insight into the classification of mycoplasmas.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bennett L. L., Jr, Schnebli H. P., Vail M. H., Allan P. W., Montgomery J. A. Purine ribonucleoside kinase activity and resistance to some analogs of adenosine. Mol Pharmacol. 1966 Sep;2(5):432–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch E. W., von Borcke I. M., Martinez B. Abbauwege und Abbaumuster der Purinnucleotide in Herz-, Leber-, und Nierengewebe von Kaninchen nach Kreislaufstillstand. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968 Sep 24;166(2):547–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice R. A., Robillard N. F., Carski T. R. Immunofluorescence identification of Mycoplasma on agar by use of incident illumination. J Bacteriol. 1967 Apr;93(4):1205–1209. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.4.1205-1209.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A. E., Kelloff G. J., Gilden R. V., Lane W. T., Swain A. P., Huebner R. J. Activation and isolation of hamster-specific C-type RNA viruses from tumors induced by cell cultures transformed by chemical carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Oct;68(10):2386–2390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.10.2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDFINGER S., KLINENBERG J. R., SEEGMILLER J. E. THE RENAL EXCRETION OF OXYPURINES. J Clin Invest. 1965 Apr;44:623–628. doi: 10.1172/JCI105175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R., Kornberg A. Biochemical studies of bacterial sporulation and germination. V. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase of vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus cereus. J Biol Chem. 1967 May 25;242(10):2383–2388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAKALA M. T., HOLLAND J. F., HOROSZEWICZ J. S. Change in pyrimidine deoxyribonucleoside metabolism in cell culture caused by Mycoplasma (PPLO) contamination. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1963 Jun 20;11:466–471. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch-Petersen A. On the catabolism of deoxyribonucleosides in cells and cell extracts of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1968 Nov;6(3):432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B. C., Hoffee P. A. Purification and properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1973 Mar 25;248(6):2040–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B. C., Jargiello P., Blank J., Hoffee P. A. Genetic regulation of ribonucleoside and deoxyribonucleoside catabolism in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1970 Jun;102(3):628–635. doi: 10.1128/jb.102.3.628-635.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGINO Y., MIYOSHI Y. THE SPECIFIC PRECIPITATION OF ORTHOPHOSPHATE AND SOME BIOCHEMICAL APPLICATIONS. J Biol Chem. 1964 Jul;239:2360–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E. L., Stanbridge E. J., Epstein C. J. Incorporation of 3H-uridine and 3H-uracil into RNA: a simple technique for the detection of mycoplasma contamination of cultured cells. Exp Cell Res. 1974 Mar 15;84(1):311–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder F. F., Henderson J. F. Alternative pathways of deoxyadenosine and adenosine metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1973 Aug 25;248(16):5899–5904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbridge E. Mycoplasmas and cell cultures. Bacteriol Rev. 1971 Jun;35(2):206–227. doi: 10.1128/br.35.2.206-227.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TODARO G. J., GREEN H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963 May;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman T. P., Gersten N. B., Ross A. F., Miech R. P. Adenine as substrate for purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Can J Biochem. 1971 Sep;49(9):1050–1054. doi: 10.1139/o71-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]