Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells efficiently cytolyse tumors and virally infected cells. Despite the important role that interleukin (IL)-2 plays in stimulating the proliferation of NK cells and increasing NK cell activity, little is known about the alterations in the global NK cell proteome following IL-2 activation. To compare the proteomes of naïve and IL-2-activated primary NK cells and identify key cellular pathways involved in IL-2 signaling, we isolated proteins from naïve and IL-2-activated NK cells from healthy donors, the proteins were trypsinized and the resulting peptides were analyzed by 2D LC ESI-MS/MS followed by label-free quantification. In total, more than 2000 proteins were identified from naïve and IL-2-activated NK cells where 383 proteins were found to be differentially expressed following IL-2 activation. Functional annotation of IL-2 regulated proteins revealed potential targets for future investigation of IL-2 signaling in human primary NK cells. A pathway analysis was performed and revealed several pathways that were not previously known to be involved in IL-2 response, including ubiquitin proteasome pathway, integrin signaling pathway, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling pathway, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway and Wnt signaling pathway.

Keywords: NK cells, IL-2 signaling, Mass spectrometry pathways, Proteomics, Lab-free quantification, Multi-dimensional separation

1. Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes generated in bone marrow that make up 5–15% of the peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) [1]. NK cells mediate important innate immune responses that protect against viral infections and cancer. NK cells directly kill target cells by recruiting granzyme and perforin containing secretory granules to the immunological synapse with target cells and also release proinflammatory cytokines such as interferon gamma (INF-γ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). The immunologic activities of NK cells are controlled by intracellular signal transduction mediated by specific cytokines and a complex crosstalk between activating and inhibitory receptors [2].

IL-2, one of the first cytokines discovered, is a 15.5 kDa protein that stimulates the proliferation of T cells and NK cells [3]. In NK cells, IL-2 also augments cytotoxic function [4,5] (conventionally referred to as the Lymphokine-Activated Killer (LAK) cell activity) and induces IFN-γ production. IL-2 mediates its effects through interaction with a cell surface receptor complex consisting of IL-2Rα (CD25) and IL-2Rβ (CD122) and IL-2Rγc chain (CD132) [6]. Upon activation, IL-2Rβ and γc chain phosphorylate two Janus tyrosine-kinases (JAKs), JAK1 and JAK3, which are required for IL-2 signaling in T cells and NK cells [7–10]. Phosphorylation of JAK1 and JAK3 leads to recruitment and activation of Signal Transducers and Activators (STATs), a family of transcription factors that contribute to the diversity of cytokine responses. Following activation, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 translocate to the nucleus and activate target genes [11]. In addition to the JAK–STAT pathway, IL-2 also mediates signal transduction via protein kinase C (PKC), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and NF-κB [12]. Rapid activation of MAPK kinase (MKK)/ERK pathway by IL-2, for example, contributes to the generation of LAK activity, IFN-γ expression, and increased surface expression of CD26 and CD69 on NK cells [13]. Additionally, IL-2-mediated activation of NF-κB is responsible for up-regulation of perforin [14]. Recent studies have also shown that the non-apoptotic functions of caspases also contribute to the IL-2 mediated proliferation of NK cells [15].

All of these studies suggest that IL-2 initiates a multifactorial signaling response that collectively regulates the biological activity of NK cells. In-depth studies that utilize appropriate “omic” approaches will provide important strategies to identify the global molecular events triggered by IL-2 in human NK cells. Given the increasing use of immunotherapeutic strategies that rely on the IL-2-mediated activation of NK cells to target human cancers the impact of cutting-edge approaches to fully characterize IL-2 signaling could be especially relevant. Some IL-2 centered strategies have already been approved by the FDA for the treatment of metastatic melanoma [16] and renal cell carcinoma [17]. Intense research (basic, translational, and clinical) is also underway on the use of IL-2 and IL-2-antibody conjugates (immunocytokines) to boost the anti-cancer activities of NK [18–21]. Our initial studies on the characterization of the global proteome of naïve and IL-2-stimulated human NK cells reveal a large number of proteins exhibiting changes in expression levels upon IL-2 stimulation. Previous studies have conducted gel-based analysis of high abundance proteins from the membrane and secretory lysosome of NK cells [22–26]. The current study is the first to utilize a non-gel-based LC–MS/MS shotgun approach to carefully study the IL-2-induced changes in the global proteome of NK cells. More than two thousand proteins were identified from cell lysates of NK cells, representing the largest protein catalog reported to date. Label-free quantification by spectral counting was used to identify 383 NK cell proteins that were significantly up- or down-regulated in response to IL-2 stimulation.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Materials

Protein standards, bovine serum albumin (BSA), bovine cytochrome c (bCYC) and equine myoglobin (eMYG) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). RIPA buffer was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Urea and ammonium bicarbonate were from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Ammonium formate and iodoacetamide (IAM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dithiothreitol (DTT) and sequencing grade modified trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). High quality LC–MS grade and Optima grade solvents (ACN and water) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Recombinant human IL-2 was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

2.2. Sample collection

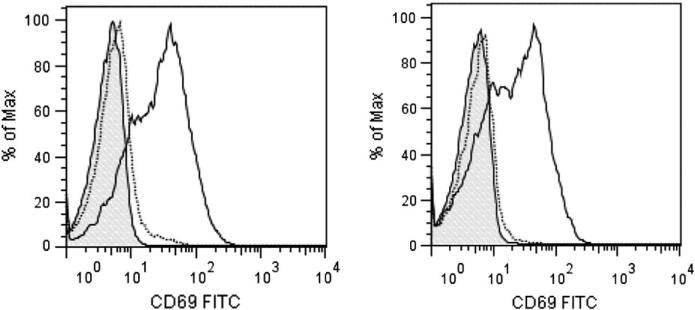

Human primary NK cells were isolated from three healthy donors. Informed consent was obtained from all three blood donors recruited and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. NK cells from the blood samples were isolated by negative selection. The RosetteSep NK cell isolation kit (Stem Cell Technologies) was used and NK cell purification was conducted according to the manufacturer's protocol and the purity of the isolated NK cells was determined by monitoring of CD3, CD16, CD56, and NKp46 expression via flow cytometry as described in our previous work [27–29]. The purified NK cells from each donor were divided equally into two groups. Each group was cultured in medium supplemented with or without IL-2 for 16 h. Following IL-2 (300 U/ml) stimulation, the activation status of NK cells was confirmed by monitoring elevation in CD69 expression (Fig. 1). NK cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 200 μL RIPA, sonicated for 20 s and incubated on ice for 20 min. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 16,100 ×g at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Acetone (chilled to −80 °C) was added gradually (with intermittent vortexing) to the protein extract to a final concentration of 80% (v/v). The solution was incubated at −20 °C for 60 min and centrifuged at 16,100 ×g for 15 min. The supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was carefully washed twice using cold acetone to ensure efficient removal of detergent. Residual acetone was evaporated at ambient temperature.

Fig. 1.

NK cell activation. NK cells isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors were stimulated for 16 h with IL-2. Activation status of the NK cells was determined by monitoring increase in the CD69 levels on the surface of the NK cells using flow cytometry. Data shown is for NK cells isolated from two different healthy donors. Control NK cells (dotted line) and IL-2 stimulated cells (solid line) were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD69 antibody. Shaded area depicts binding of non-specific murine IgG antibody.

2.3. Proteolysis

All protein samples were denatured with 8 M urea in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, and reduced by incubating with 50 mM DTT at 37 °C for 1 h. The reduced proteins were alkylated for 1 h in darkness with 100 mM iodoacetamide. The alkylation reaction was quenched by adding DTT to a final concentration of 50 mM. The samples were diluted to a final concentration of 1 M urea. Trypsin was added to the sample at a 30:1 protein to trypsin mass ratio. The sample was incubated at 37 °C overnight.

2.4. Off-line first dimension high pH RPLC

Tryptic digests (38 μg) from each sample were injected onto a Waters Alliance HPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) with a high pH-stable RP column (Phenomenex Gemini C18, 150 mm × 2.1 mm, 3 μm) at a flow rate of 150 μL/min. The peptides were eluted with a gradient from 5 to 45% solvent B over 45 min (solvent A: 100 mM ammonium formate, pH 10; solvent B: acetonitrile (ACN)). Fractions were collected every 2 min. Twenty fractions were collected from the first dimensional RPLC at pH 10, and then every two fractions with equal collection time interval were pooled, one from the early eluted section and the other from the later eluted section as previously described [30]. The ten pooled fractions were dried by Speedvac and reconstituted in 30 μL of 0.1% formic acid. 5 μL of each fraction was subjected to nanoLC–MS/MS.

2.5. LC–ESI ion trap mass spectrometry and MS/MS analysis

Ten pooled fractions collected from high pH RPLC were analyzed using amaZon ETD ion trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Billerica, MA) equipped with Waters nanoAcquity UPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). For the chromatographic separation, solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in ACN. 5 μL of each sample was injected onto a Waters Symmetry C18 5 μm 180 μm × 20 mm precolumn at a flow rate of 5 μL/min for 5 min at 95% A/5% B, followed by peptide separation performed on Waters BEH130 1.7 μm C18 100 μm × 100 mm analytical column using gradient from 0 to 45% solvent B at 300 nL/min over 90 min. Acquisition of precursor ions and MS/MS spectra was performed using the parameters as indicated below: Smart parameter setting (SPS) was set to 700 m/z and compound stability and trap drive level were set at 100%. Dry gas temperature, 125 °C; dry gas, 4.0 L/min; capillary voltage, − 1300 V; end plate offset, −500 V; MS/MS fragmentation amplitude, 1.0 V; and Smart fragmentation set at 30–300%. Data were generated in data-dependent mode with strict active exclusion set after two spectra and released after 1 min. MS/MS spectra were obtained via collision induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation for the six most abundant MS ions. For MS generation the ion charge control (ICC) target was set to 200,000; maximum accumulation time, 50.00 ms; one spectrometric average; rolling average, 2; acquisition range of 300–1500 m/z; and scan speed (enhanced resolution) of 8100 m/z s−1. For MS/MS generation the ICC target was set to 300,000; maximum accumulation time, 50.00 ms; two spectrometric averages; acquisition range of 100–2000 m/z; and scan speed (Ultrascan) of 32,000 m/z per second.

2.6. Database search

MS/MS spectra were converted into Mascot Generic Format (.mgf) files by DataAnalysis (Ver 4.0, Bruker Daltonics Billerica, MA). Deviations in parameters from the default Protein Analysis in DataAnalysis were as follows: intensity threshold, 1000; maximum number of compounds, 1E9; and retention time window 0.001 min. The resulting mgf files were then searched against a home-built Human SwissProt database (SwissProt_2011_12.fasta, 533,657 entries plus 3 standard proteins, BSA, bCYC and eMYG) with Mascot 2.3.02. The searching parameters and criteria were set as the following: tryptic digestion, maximum 2 missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation of cysteine as the fixed modification, oxidation of methionine as the variable modification, peptide mass tolerance of 1.2 Da, fragment mass tolerance of 0.6 Da, 2+, 3+ and 4+ chosen for charge state. In this study a simultaneous target-decoy search strategy (automatic decoy search) was adopted to facilitate false discovery rate (FDR) estimation. With simultaneous target-decoy search, a MS/MS spectrum is simultaneously searched against a protein sequence from the target database and its scramble version in decoy database. Therefore, FDR can be calculated from decoy hits and target hits. We applied Mascot Percolator to improve peptide and protein identification. Mascot Percolator has been well developed [31] and embedded into Mascot search engine. Mascot Percolator is a well performing machine learning method which constructs a support vector machine by using Mascot search parameters and results to re-rank peptide or protein identification. With Mascot Percolator, some low quality MS/MS spectra were re-searched to produce reliable peptide identification. We check “Percolator” option on Mascot results and control the resulting FDR at ~1%. Set “a bold red peptide required” for protein assembly. Since there were three technical replicates for each sample, only proteins identified in at least two out of three replicates were considered.

2.7. Protein quantification

Given the biological variation and technical variation across datasets, only a subset of identified proteins is qualified for quantification. It is important to select the appropriate amount of quantifiable proteins. Since we prepared three biological samples and each sample has three replicates, we set the following criteria to select quantifiable proteins: 1) a protein is quantifiable if it can be detected in at least two of three technical replicates; and 2) it can be detected in all three biological replicates. An additional complication results from protein sequence conservation. Thus in our analysis the spectral counts observed in the mass spectrometer included the tryptic peptides shared between proteins. To address this limitation we calculate the distributive normalized spectral abundance factor (dNSAF) for each quantifiable protein within a chromatographic run using the following formula [32]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where dSAF is the distributive spectral abundance factor for a given protein, μSpC is the spectral counts of unique peptides associated with this protein while sSpC is the spectral counts of shared peptides associated with this protein. M is the monoisotopic mass of protein. The definition of “unique” peptide is the peptide whose sequence matched only one protein whereas “shared” peptide means the peptide whose sequence is shared by multiple proteins. Another limitation of our approach is the variability in peptide detection between runs. In some cases a peptide may not be observed or identified in some runs resulting in a zero count value for that peptide in a particular run. The following method was used to impute spectral counts with zero value. First, if a protein had only one zero spectral count out of three technical replicates, we calculated the average value of spectral counts of this protein in all three replicates, and then replaced the zero spectral count with the average value. Next, in the case of zero spectral counts in all three replicates, we followed the method as previously described [33] to determine a fraction value within [0,1] to replace the zero spectral counts. An iterative process was used where zero spectral counts were replaced by a fraction of a spectral count between 0 and 1, and the normality of the resulting ln(dNSAF) distribution was evaluated by the Shapiro–Wilk test. It is advisable to use the smallest value in order not to change the total sum significantly. An in-house program written in Java was used to extract peptides from the database results obtained from Mascot Percolator, select quantifiable proteins and then calculate spectral counts and dNSAF values. R program is used to evaluate the normality of ln(dNSAF) distribution by Shapiro– Wilk test. p-Value > 0.05 indicates the distribution can be considered as Gaussian distribution.

2.8. Sample preparation and protein quantification of standard proteins

To validate our use of Mascot Percolator results in label-free spectral counting quantitation and dNSAF normalization we used an NKL cell lysate spiked with known amounts of commercially available proteins from other species. For this analysis NKL cell lysates were obtained from 10 million NKL cells using the same method as described in the “Sample collection” section. Both standard proteins and NKL cell lysates were digested by trypsin using the same protocol as described in the “Proteolysis” section. The amounts of tryptic digests of each protein standard spiked into 10 μg tryptic digests of NKL cell lysates were 4 μg, 1 μg, 0.25 μg, 62.5 ng, 15.625 ng, 3.91 ng of BSA, bCYC and eMYG, respectively. Each sample (300 ng) was injected onto a Waters nanoAcquity UPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) with an amaZon ion trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). Each sample was run in triplicate. For the chromatographic separation, solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in ACN. 5 μL of each sample was injected onto a Waters Symmetry C18 5 μm 180 μm × 20 mm precolumn at a flow rate of 5 μL/min for 5 min at 95% A/5% B, followed by peptide separation performed on Waters BEH130 1.7 μm C18 100 μm × 100 mm analytical column using gradient from 0 to 45% solvent B at 300 nL/min over 120 min parameters for the acquisition of precursor ions and MS/MS spectra were the same as that of described in the “LC–ESI ion trap mass spectrometry and MS/MS analysis” section. The methods for database search and protein quantification were the same as described above.

2.9. Real time PCR

RT-PCR was performed to evaluate levels of mRNAs for some of the proteins we identified as being differentially expressed in our proteomic approach. The untreated and IL-2 treated NK cells were homogenized in Trizol (Sigma, Cat No. T9424) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA using Omniscript RT kit from Qiagen (Cat. No. 205111). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR green chemistry (SsoFast Evagreen Supermix from BioRad, Cat. No. 172-5201) in a CFX96 real-time PCR detection system. The qPCR validated primers used to amplify PTP1B, CD97, and PCNA were obtained from SA Biosciences (real time PCR primers for Human PTP1B, Cat No. PPH00730C; CD97, Cat No. PPH07186A; PCNA, Cat No. PPH00216B and S27, Cat No. PPH17248B). The three step cycling conditions used were, 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of the denaturation at 95 °C for 1 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 5 s. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used for relative quantitation of gene expression. Data was analyzed using the BioRad CFX manager and GraphPad Prizm.

2.10. Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was employed to determine purity of the isolated NK cells (defined CD3−/CD16+/CD56+ cells), monitor their activation status after treatment with IL-2 by determining the expression level of CD69, and validate the differential expression CD48, CD56, CD11b, and CD11c. To determine purity NK cells were labeled with anti-CD3, -CD16, and -CD56 antibodies conjugated with PE, FITC, and APC, respectively, as described in our previous work [28,29]. CD69, CD48, CD11b, and CD11c antibodies used in the study were conjugated to either FITC or PE as denoted in the figures. Following labeling with the antibodies, the NK cells were washed and analyzed on LSR-II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. FlowJo® software was used to analyze the data.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification and quantification of proteins in naïve and IL-2-activated NK cells

In recent years, targeted MS-based approaches have been employed to analyze the proteome of human NK-like cell lines, YTS and NKL [22–26,34]. NK-like cell lines and primary NK cells differ, substantially in the expression of cell surface receptors and intracellular signal transduction proteins [34]. Therefore, primary human NK cells were predominantly used in the current study. We anticipated that the complexity of unfractionated cell lysates would make it difficult to identify less abundant proteins. We therefore employed an orthogonal chromatographic step to reduce sample complexity prior to MS analysis to improve overall protein identifications. We adopted a two-dimensional separation approach utilizing high-pH RPLC as the first dimension separation. Increasing the number of fractions collected during first dimension liquid chromatography typically results in better separation that allows improved protein identification by downstream LC–MS/MS analysis [35]. However, since greater number of fractions also results in increased overall analysis time it is important to minimize the numbers of fractions but still produce the best output for LC–MS/MS analysis. To address the limitation of fraction collection but at the same time improve the orthogonality of the 2D separation, we adopted a novel RP-RPLC approach reported by Zou and colleagues [30]. For this approach, 20 fractions were collected in the first dimensional RPLC. Every two fractions with equal collection time interval were pooled, one from the early eluted section and the other from a later elution section (fractions 1 and 11, 2 and 12, and so on). Through this combination only half the number of fractions was submitted to LC–MS/MS analysis, significantly reducing the overall analysis time.

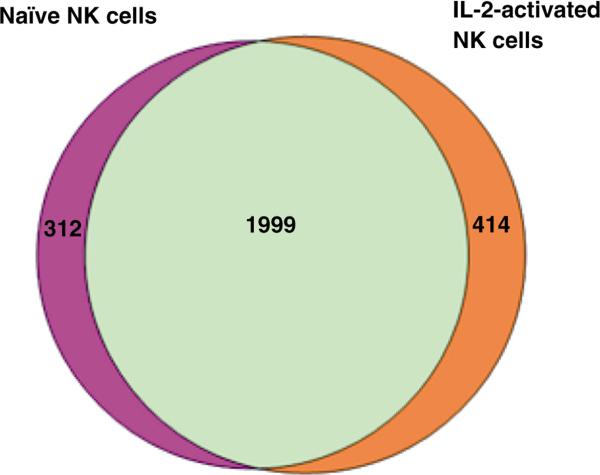

For the present work we applied Mascot Percolator which was embedded into the Mascot search engine to improve peptide and protein identifications. We compared the number of peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) identified with Mascot and Mascot Percolator at FDR = 0.1% and it was shown that more peptides could be identified by Mascot Percolator (data not shown). In total, 2311 proteins (≥1 unique peptide) were identified from three naïve NK cell samples, while 2413 proteins were identified from their IL-2 stimulated counterparts. The complete list of identified proteins from each donor is shown in the Supporting information (Table S1). Fig. 2 shows the Venn Diagrams of the numbers of proteins identified from naïve or IL-2 activated NK cells isolated from three healthy donors. There were 1999 proteins in common that were identified in both cells, whereas 312 proteins and 414 proteins were identified in only naïve or IL-2 activated NK cell, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Venn diagram depicting the total number of proteins identified in naïve or IL-2-activated NK cells. Human primary NK cells isolated from three healthy donors were cultured in medium supplemented with or without IL-2 for 16 h. Total proteins were extracted and digested by trypsin follow by 2D LC–MS/MS analysis. 2311 proteins were identified from naïve NK cell samples, while 2413 proteins were identified in IL-2-activated NK cells. 1999 proteins were commonly identified in both conditions.

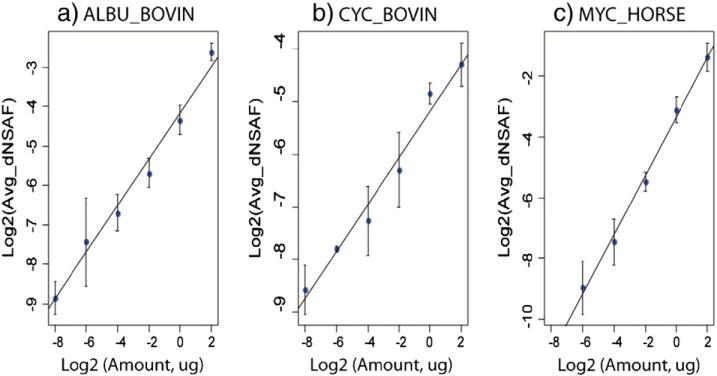

To assess differences between protein abundance in naïve NK cells and IL-2-activated NK cells, spectral counting, a label-free protein quantification method was used. To account for shared peptide sequences among protein isoforms and achieve better accuracy, we adopted the distributive normalized spectral abundance factor (dNSAF) strategy previously reported by Zhang et al. [32]. However, given that the application of Mascot Percolater in peptide and protein identification may affect the performance of this approach, we first confirmed its effectiveness and reproducibility by spiking known amounts of protein standards into complex mixture of NKL cell lysates. To estimate the dynamic range and determine whether there was a linear correlation between the known amount of protein and their measured dNSAF values, the tryptic digests of BSA, bCYC and eMYG were spiked into tryptic digests of NKL cell lysates where the amounts of three standard proteins distributed evenly over 3 orders of magnitude in logarithmic scale. After protein identification with Mascot Percolator, dNSAF values for all quantifiable proteins were calculated. dNSAF values for BSA, bCYC and eMYG in different samples were extracted. Fig. 3 shows the linear regression between dNSAF values and known protein amounts where log2-transformed dNSAF values were plotted as a function of log2-transformed protein amounts in micrograms. The results demonstrated acceptable performance as there was a linear correlation coefficient of >0.990 for all three protein standards (Fig. 3a–c). The linear dynamic range for BSA and bCYC are three orders of magnitude (1024) while the dynamic range for eMYG is two orders of magnitude (256), which is probably due to the poor detection at lower concentration, as the presence of heme stabilizes the structure of eMYG and makes it resistant to digestion [36]. Based on this result, we concluded that the application of Mascot Percolater for peptide and protein identification did not affect the accuracy of protein quantification by spectral counting used in the present work. The linearity of our quantification method is maintained between protein amounts and dNSAF values over a dynamic range of at least three orders of magnitudes.

Fig. 3.

Linear regression between dNSAF values and known amount of protein standards BSA (a), cytochrome C (b) and myoglobin (c). Log2-transformed dNSAF values were plotted as a function of log2-transformed protein amounts in micrograms.

We analyzed the proteomes from three donors (three biological replicates) where each biological replicate contained three technical replicates to account for the biological and technical variation across datasets prior to protein quantification. According to the criteria that a protein is quantifiable if it can be detected in at least two of three technical replicates in all three biological replicates, 1375 proteins identified from both naïve NK cells and IL-2 activated NK cells were selected for quantification analysis. The dNSAF value of each protein was calculated and compared between the two conditions (naïve vs. IL-2-activated NK cells). Fold-change was calculated as the ratio of dNSAF of protein in IL-2-activated NK cells over that of naïve NK cells. Threshold levels for significantly up- or down-regulated proteins were set to more than 2-fold or less than 0.5-fold with p ≤ 0.05 from Student t-test. Altogether, 436, 420 and 456 proteins exhibited significant abundance differences after IL-2 activation in NK cells isolated from the three donors, respectively. The complete list of up- and down-regulated proteins from each donor is shown in the Supporting information (Table S2). An overlap of 383 proteins was observed across all three donors and demonstrated similar trend of up or down-regulation (Table S2). While 301 proteins were up-regulated following IL-2 activation, 82 proteins were down-regulated (Table S2). In the discussion that follows, we focus on a select group of factors that, according to our proteomic analysis, are differentially expressed in the IL-2 stimulated human NK cells but have not been extensively studied in the IL-2-mediated modulation of NK cell responses.

3.2. Functional annotation of IL-2-regulated proteins identified by quantitative analysis

3.2.1. Activation of JAK–STAT pathway and cell proliferation

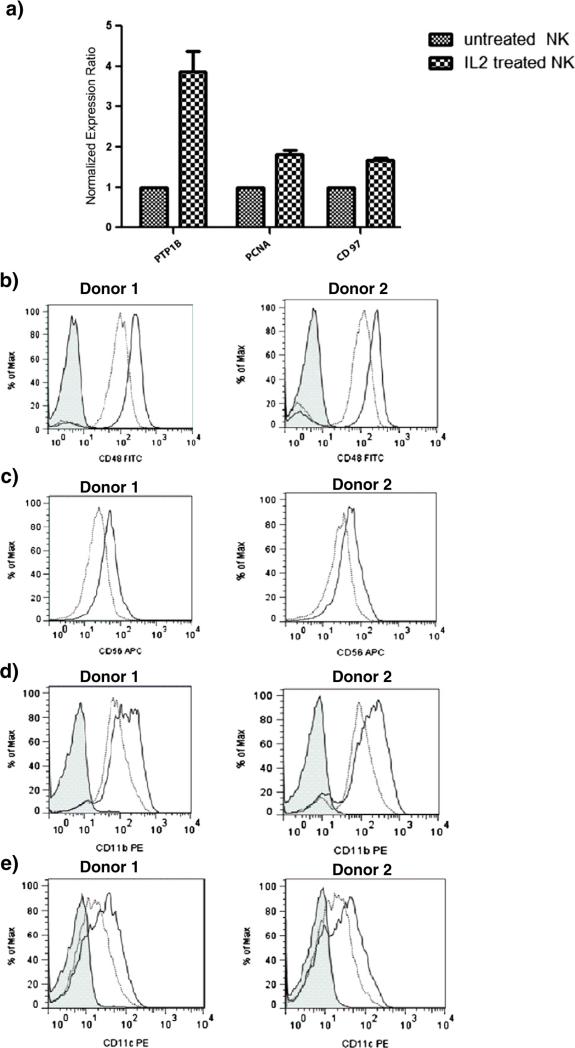

IL-2 critically regulates the proliferation and cytotoxicity of human NK cells. It is well known that IL-2 mediates its effects through the activation of the JAK–STAT pathway in which STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 are activated. In our analysis, three STAT molecules STAT1, STAT3 and STAT4 were found to be up-regulated upon IL-2 stimulation. While the participation and the role of STAT1 and STAT3 in IL-2 signaling have been well documented, the function of STAT4 is still under investigation. Wang et al. reported IL-2 induced STAT4 activation as an alternative to the well-established JAK– STAT pathway in primary NK cells but not in T cells [37], which may explain why IL-2 enhances cytoxicity in NK cells but not in T cells, even though both cells have identical JAK–STAT signaling pathway. Moreover, they investigated the effect of IL-2 on IL-12-activated signaling pathways in NK cells and demonstrated that pretreatment of IL-2 promoted expression of high level of STAT4 through which the response of NK cells to IL-12 was enhanced [38]. Given that the results of current clinical trials for immunotherapy using IL-2 or IL-12 alone were not shown to be quite as successful as expected [39,40], STAT4 may prove to be a target for the study of synergistic effect between IL-2 and IL-12 for developing more effective immunomodulatory strategies. Another important protein involved in JAK–STAT signaling pathway is protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), which was also shown to be up-regulated by IL-2 and confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 4a). PTP1B is an important phosphatase that plays both negative and positive roles in diverse signaling pathways. Although it has been extensively studied as a negative regulator of insulin and leptin signaling, and more recently as a positive factor in tumorigenesis, the role of PTP1B during immune cell signaling is not well characterized. PTP1B and T-cell PTP (TC-PTP) form the first non-transmembrane sub-family of PTPs [41]. While previous studies have identified JAK1 and JAK3 as TC-PTP substrates and implicated TC-PTP in the regulation of JAK–STAT signaling activated by IL-2, PTP1B was unable to bind JAK1 and JAK3 [42]. However, other studies demonstrated that after IFN stimulation PTP1B targets two other JAK family members, JAK2 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) [43]. Also, PTP1B has been implicated in the dephosphorylation of STAT5 in prolactin signaling [44]. Although PTP1B does not appear to be directly associated with the regulation of JAK–STAT activation, it might play an important role in IL-2 signaling through another mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Validation of selected factors differentially expressed in IL-2 stimulated NK cells. Real-time-PCR analysis (a) of mRNA level of PTP1B, PCNA, and CD97 in naïve NK cells and NK cells activated by IL-2 for 16 h. Flow cytometry was used to monitor differential expression of CD48 (b), CD56 (c), CD11b (d), and CD11c (e) on naïve NK cells (dotted line) and NK cells stimulated with IL-2 (solid line) for 16 h. For each factor, data obtained for NK cells isolated from two healthy donors is shown. Non-specific IgG control is (shaded histogram) is shown only for the CD48 data.

As expected, many proteins identified to be up or down-regulated are involved in DNA replication, translation initiation/ elongation/termination or the regulation of cell cycle since one of the known results of NK cell exposure to IL-2 is stimulation of cell proliferation. Three DNA replication licensing factor MCM2, MCM5 and MCM7 were found to be up-regulated. DNA replication licensing is the process of ensuring that chromosomes are duplicated once and only once during the cell cycle. The MCM proteins are required for DNA replication licensing and consist of a group of ten conserved factors functioning in the replication of the genomes of archae and eukaryotic organisms. Among these, MCM2–7 proteins are related to each other and form a family of DNA helicases at the initiation step of DNA synthesis. While the other MCM proteins were not detected in our analysis possibly due to their low abundance, the elevated expression of MCM2, MCM5 and MCM7 implicated that increased NK cell proliferation may be attributable to these proteins. Lymphocyte proliferation is often used to mark immune response following immunotherapy. Identifying proteins that improve monitoring of NK cell proliferation to determine the extent of the immune response may prove to be crucial for clinical decision-making during the immunotherapy in order to minimize the risk of toxicity in patients.

Another protein that is associated with the proliferation process of NK cells is proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) which is synthesized in early G1 and S phases of the cell cycle. Increased PCNA expression was also observed in our proteomic analysis. We validated our proteomic observations using real time PCR and confirmed that the level of PCNA mRNA expression was increased by 2-fold in NK cells after 16 h of stimulation by IL-2 (Fig. 4a). PCNA is a marker that can be used to detect early stage T-cell proliferation, as it was found that unstimulated human peripheral blood T-lymphocytes were PCNA negative and expression of PCNA in these cells increased after stimulation [45]. In the clinical setting, PCNA can be used as a marker to monitor T-cell function that reflects immune condition in patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy [46,47]. Such monitoring of PCNA would be crucial in reducing the risks and providing optimal immunosuppressive therapy for each transplant recipient [46–48]. Recently, PCNA mRNA level in the peripheral blood were measured by real-time RT-PCR to monitor patient's immune condition after renal transplantation [49]. Increased PCNA expression observed in our analysis suggest that monitoring the levels of this antigen may provide useful guidance of the NK cell proliferation status in patients treated with immunotherapies. PCNA is recruited to the NK cell immune synapse and via its interaction with the NKp44 receptor attenuates NK cell function. In this context PCNA expression allows cancer cells to escape NK cell attack. It remains to be determined if the increased expression of PCNA represents a compensatory mechanism to attenuate immuno-logical function of the IL-2-stimulated NK cells [50,51].

3.2.2. Cluster of differentiation (CD) molecules

In addition to changes in molecules that regulate cell proliferation and activation of cytotoxicity in NK cells, changes in cluster of differentiation (CD) molecules were also expected, as their functions are often closely tied to the immune system. While CD56, CD48, CD98, CD97, CD225, and CD300a showed increased expression in our analysis, notably, there were decreases in the levels of CD11b, CD11d, CD11c and CD43 after IL-2 stimulation. Flow cytometry assays were used to validate the increased expression of CD48 and CD56 on the IL-2 activated NK cells (Fig. 4b, c). CD48 is a glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol (GPI)-anchored protein expressed on the surface of NK cells and is known as a co-stimulatory factor and a high affinity ligand for natural killer cell receptor 2B4 [52,53]. 2B4/CD48 interactions in NK cells are required for the enhanced proliferation and the development of optimal cytolytic and secretory NK effector functions during IL-2 activation [54]. Increased expression of CD48 on the NK cells may allow this ligand to be presented to the 2B4 receptor on opposing NK, T or B cells, thereby priming the NK cells to express IL-13 in the presence of another co-stimulatory signal [55].

Human CD97 is a member of the EGF-TM7 family of adhesion class heptahelical receptors and was identified as an early activation marker for human lymphocytes [56]. We observed and validated increased CD97 level in response to IL-2 by real time RT-PCR (Fig. 4a) that was comparable with the results from Kop et al. [57].

CD98 is a transmembrane glycoprotein identified as a lymphocyte activation antigen [58,59]. Because the level of CD98 on cell surface was markedly increased in activated lymphocytes, CD98 has been mainly used as a T cell activation marker [58,59] and has been implicated for its role in regulating integrin signaling, amino acid transport and immune response [60,61]. Integrin–CD98 interaction acts as a co-stimulatory signal in T cells [62,63]. So far no studies have investigated the role of CD98 in NK cell activation.

CD300a is a cell surface inhibitory receptor that is expressed in all human NK cells and is known to down-regulate the cytotoxicity of NK cells [64]. Different studies have also evaluated the CD300a activity in immune regulation in other immune cells such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells [65], T cells [66] and neutrophils [67]. However, little is known about the functionality and the ligand of CD300a in NK cells so far and it was only recently that Nakahashi-Oda et al. identified phosphatidylserine (PS), which is exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of apoptotic cells, as a ligand for CD300a [68]. Alvarez et al. reported that inflammatory stimuli such as granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) could induce a significant increase in cell surface expression of CD300a in neutrophils and that the signaling through this receptor down-regulated neutrophil function [67]. Activation and regulation of CD300a by cytokines in NK cells have never been reported but our results and the research in other cell-types suggest that CD300a may play a critical role in NK cell responses. Further investigation is required to understand how CD300a is regulated by IL-2 and the physiological role of CD300a in NK cells.

CD225 is also known as interferon (IFN)-induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1) which is a member of the IFN-inducible transmembrane protein family [69]. It is known that the transcription of CD225 is induced by IFN-γ [70], and that CD225 can mediate IFN-γ-induced inhibition of cell proliferation and inhibit ERK activation [71]. CD225 has also been implicated in the control of cell growth, as it can arrest cell cycle progression in the G1 phase in a p53-dependent manner [71]. The role of CD225 in NK cell activation has never been reported. However, as an important factor for growth control, it is likely that CD225 mediates the negative regulation and plays an anti-proliferative role during NK cell activation.

Surprisingly, proteomic analysis indicated that IL-2 stimulation results in decreased expression of the integrin α subunits CD11b, CD11c and CD11d. Even CD43, which along with the CD11 molecules are described as NK cell maturation markers [72]. Flow cytometry analysis indicated that IL-2 stimulation results in increased expression of CD11b and CD11c on the NK cell surface (Fig. 4d, e). We are currently investigating if methodological issues resulting from the processing of the NK cell lysates or the generation of the tryptic peptides from these lysates contribute to the discrepancy in these results.

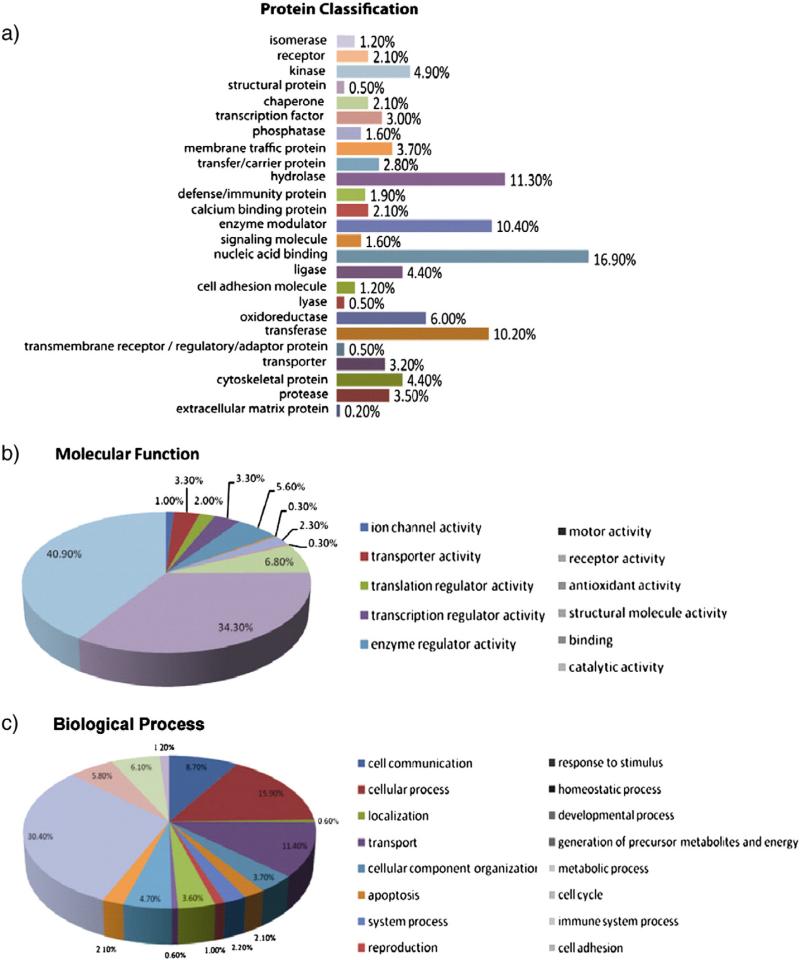

3.3. Gene ontology and pathway analysis

To obtain more information about the molecular function of IL-2 regulated proteins and to identify pathways possibly involved in IL-2 activation in NK cells, we performed gene ontology and pathway analysis using the PANTHER database (http://www.pantherdb.org/). Overall, 383 proteins that were found differentially expressed across all three donors could be classified into 25 categories of which the top four are nucleic acid binding proteins (17%), hydrolases (11.3%), enzyme modulators (10.4%), and transferases (10.2%) (Fig. 5a). This is in agreement with the fact that the activation of NK cells in response to cytokines requires protein regulators to bind to DNA and activate new protein synthesis for cell proliferation and enhanced cytotoxicity. An analysis of the molecular function of these proteins revealed that most of these proteins are involved in catalytic activities (41%) and binding (34%) (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, these proteins were found to be involved in various biological processes, of which the top three categories are: metabolic process (30.4%), cell process (15.9%) and transport (11.4%) (Fig. 5c). Taken together, the data from gene ontology analysis suggested that most of these proteins are involved in critical cellular events triggered by IL-2 in the NK cells.

Fig. 5.

Gene ontology analysis of up- and down-regulated proteins. (a) Protein functional classification. 383 proteins that were found differentially expressed across all three donors could be classified into 25 categories, of which the top four are nucleic acid binding proteins (17%), hydrolase (11.3%), enzyme modulator (10.4%), and transferase (10.2%). (b) Molecular function. More than 70% of IL-2 regulated proteins have molecular function related to catalytic activities (41%) and binding (34%). (c) Biological process. IL-2 regulated proteins were found to be involved in 16 biological processes, of which the top three categories are: metabolic process (30.4%), cell process (15.9%) and transport (11.4%). Gene ontology analysis was performed in PANTHER database (http://www.pantherdb.org/).

In search for novel pathways that might be involved in IL-2 signaling in NK cells, a pathway analysis was also performed in PANTHER database and a total of 90 pathways were found to be related to the IL-2 regulated proteins based on this study. In addition to the previously known pathways, such as JAK– STAT pathway, MAPK/ERK and NF-κB pathway, other pathways that are very likely to be associated with IL-2 signaling include: ubiquitin proteasome pathway, integrin signaling pathway, PDGF signaling pathway, EGFR signaling pathway and Wnt signaling pathway. Table 1 provides the names of IL-2 regulated proteins identified in our analysis that are known to be the components of these pathways. Although the roles of these pathways in promoting or regulating the function of NK cells have been investigated in the past, so far none of them have been directly linked to the activation of NK cells by IL-2, and therefore could be the new targets for future studies. Given the pleiotropic effects of IL-2 and diverse functions of IL-2-activated NK cells, there should be many possible downstream effectors that may be necessary to drive IL-2-induced effects.

Table 1.

Novel pathways that may be involved in IL-2 signaling in human primary NK cells and names of IL-2 regulated proteins that are known to be the components of these pathways.

| Ubiquitin proteasome pathway (11) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 (PSMD1) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 (PSMD3) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4 (PSMD4) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 7 (PSMD7) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11 (PSMD11) |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 12 (PSMD12) |

| NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 catalytic subunit (UBA3) |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 4 (PRS4) |

| Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L3 (UB2L3) |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L5 (UBP5) |

| SUMO-activating enzyme subunit 1 (SAE1) |

| Integrin signaling pathway (9) |

| Integrin beta-7 (ITB7) |

| Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MP2K1) |

| Integrin alpha-X (ITAX) |

| Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 3 (RAC3) |

| ADP-ribosylation factor 3 (ARF3) |

| Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoB (RHOB) |

| Actin, gamma-enteric smooth muscle (ACTH) |

| Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Fyn (FYN) |

| Integrin alpha-D (ITAD) |

| PDGF signaling pathway (8) |

| Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MP2K1) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta (STAT1) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) |

| Ras-related protein Rab-11B (RB11B) |

| Rho GTPase-activating protein 4 (RHG04) |

| Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoB (RHOB) |

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase alpha-3 (KS6A3) |

| EGF receptor signaling pathway (7) |

| Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MP2K1) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta (STAT1) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) |

| Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 3 (RAC3) |

| Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit beta isoform (PP2AB) |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MK14) |

| Wnt signaling pathway (6) |

| Beta-arrestin-1 (ARRB1) |

| Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit beta isoform (PP2AB) |

| Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) |

| C-terminal-binding protein 2 (CTBP2) |

| Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 2 (NFAC2) |

| Actin, gamma-enteric smooth muscle (ACTH) |

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have developed an effective method for the proteomic analysis in human primary NK cells. We successfully employed 2D LC to reduce the sample complexity prior to MS analysis. To improve protein identification, Mascot Percolator was employed, with 2311 and 2413 proteins being identified from naïve and IL-2-activated NK cells, respectively. Label-free quantitative analysis via spectral counting revealed a list of 383 proteins that were either up or down-regulated in IL-2 signaling. Functional annotation of IL-2 regulated proteins in the present work revealed several proteins with important functions related to IL-2 signaling that could potentially serve as targets for future investigation of IL-2 signaling in human primary NK cells. A pathway analysis was also performed and revealed several novel pathways not previously known to be involved in IL-2 signaling. The quantitative proteomic analysis in present work provided a comprehensive view of proteins that may be associated with IL-2 signaling. Further functional analysis of proteins of interests will improve our understanding of signaling transduction and biological processes involved in NK cell activation by IL-2.

Supplementary Material

Biological significance.

The development and functional activity of natural killer (NK) cells is regulated by interleukin (IL)-2 which stimulates the proliferation of NK cells and increases NK cell activity. With the development of IL-2-based immunotherapeutic strategies that rely on the IL-2-mediated activation of NK cells to target human cancers, it is important to understand the global molecular events triggered by IL-2 in human NK cells. The differentially expressed proteins in human primary NK cells following IL-2 activation identified in this study confirmed the activation of JAK–STAT signaling pathway and cell proliferation by IL-2 as expected, but also led to the discovery and identification of other factors that are potentially important in IL-2 signaling. These new factors warrant further investigation on their potential roles in modulating NK cell biology. The results from this study suggest that the activation of NK cells by IL-2 is a dynamic process through which proteins with various functions are regulated.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Department of Defense Pilot Award Grant (W81XWH-11-1-0181). LL acknowledges an H. I. Romnes Faculty Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2013.06.024.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;47:187–376. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–76. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caligiuri MA, Zmuidzinas A, Manley TJ, Levine H, Smith KA, Ritz J. Functional consequences of interleukin 2 receptor expression on resting human lymphocytes. Identification of a novel natural killer cell subset with high affinity receptors. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1509–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnema JD, Rivlin KA, Ting AT, Schoon RA, Abraham RT, Leibson PJ. Cytokine-enhanced NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Positive modulatory effects of IL-2 and IL-12 on stimulus-dependent granule exocytosis. J Immunol. 1994;152:2098–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karnitz LM, Abraham RT. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:147–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell SM, Johnston JA, Noguchi M, Kawamura M, Bacon CM, Friedmann M, et al. Interaction of IL-2R beta and gamma c chains with Jak1 and Jak3: implications for XSCID and XCID. Science. 1994;266:1042–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7973658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellery JM, Nicholls PJ. Alternate signalling pathways from the interleukin-2 receptor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston JA, Kawamura M, Kirken RA, Chen YQ, Blake TB, Shibuya K, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370:151–3. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson BH, Willerford DM. Biology of the interleukin-2 receptor. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:1–81. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank DA, Robertson MJ, Bonni A, Ritz J, Greenberg ME. Interleukin 2 signaling involves the phosphorylation of Stat proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7779–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Lora A, Martinez M, Pedrinaci S, Garrido F. Different regulation of PKC isoenzymes and MAPK by PSK and IL-2 in the proliferative and cytotoxic activities of the NKL human natural killer cell line. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0336-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu TK, Caudell EG, Smid C, Grimm EA. IL-2 activation of NK cells: involvement of MKK1/2/ERK but not p38 kinase pathway. J Immunol. 2000;164:6244–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Zhang J, Lichtenheld MG, Meadows GG. A role for NF-kappa B activation in perforin expression of NK cells upon IL-2 receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2002;169:1319–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ussat S, Scherer G, Fazio J, Beetz S, Kabelitz D, Adam-Klages S. Human NK cells require caspases for activation-induced proliferation and cytokine release but not for cytotoxicity. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith FO, Downey SG, Klapper JA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, et al. Treatment of metastatic melanoma using interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5610–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klapper JA, Downey SG, Smith FO, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, et al. High-dose interleukin-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of response and survival in patients treated in the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute between 1986 and 2006. Cancer. 2008;113:293–301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buhtoiarov IN, Neal ZC, Gan J, Buhtoiarova TN, Patankar MS, Gubbels JA, et al. Differential internalization of hu14.18-IL2 immunocytokine by NK and tumor cell: impact on conjugation, cytotoxicity, and targeting. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:625–38. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgado DC, Hank JA, Kolesar J, Lorentzen D, Gan J, Seo S, et al. Genotypes of NK cell KIR receptors, their ligands, and Fc gamma receptors in the response of neuroblastoma patients to Hu14.18-IL2 immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9554–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gubbels JA, Gadbaw B, Buhtoiarov IN, Horibata S, Kapur AK, Patel D, et al. Ab-IL2 fusion proteins mediate NK cell immune synapse formation by polarizing CD25 to the target cell-effector cell interface. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;60:1789–800. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang RK, Kalogriopoulos NA, Rakhmilevich AL, Ranheim EA, Seo S, Kim K, et al. Intratumoral hu14.18-IL-2 (IC) induces local and systemic antitumor effects that involve both activated T and NK cells as well as enhanced IC retention. J Immunol. 2012;189:2656–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lund TC, Anderson LB, McCullar V, Higgins L, Yun GH, Grzywacz B, et al. iTRAQ is a useful method to screen for membrane-bound proteins differentially expressed in human natural killer cell types. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:644–53. doi: 10.1021/pr0603912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Man P, Novak P, Cebecauer M, Horvath O, Fiserova A, Havlicek V, et al. Mass spectrometric analysis of the glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains of rat natural killer cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:113–22. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna J, Fitchett J, Rowe T, Daniels M, Heller M, Gonen-Gross T, et al. Proteomic analysis of human natural killer cells: insights on new potential NK immune functions. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna J, Gonen-Gross T, Fitchett J, Rowe T, Daniels M, Arnon TI, et al. Novel APC-like properties of human NK cells directly regulate T cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1612–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI22787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Casey TM, Meade JL, Hewitt EW. Organelle proteomics: identification of the exocytic machinery associated with the natural killer cell secretory lysosome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:767–80. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600365-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gubbels JA, Felder M, Horibata S, Belisle JA, Kapur A, Holden H, et al. MUC16 provides immune protection by inhibiting synapse formation between NK and ovarian tumor cells. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belisle JA, Gubbels JA, Raphael CA, Migneault M, Rancourt C, Connor JP, et al. Peritoneal natural killer cells from epithelial ovarian cancer patients show an altered phenotype and bind to the tumour marker MUC16 (CA125). Immunology. 2007;122:418–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patankar MS, Jing Y, Morrison JC, Belisle JA, Lattanzio FA, Deng Y, et al. Potent suppression of natural killer cell response mediated by the ovarian tumor marker CA125. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:704–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song C, Ye M, Han G, Jiang X, Wang F, Yu Z, et al. Reversed-phase-reversed-phase liquid chromatography approach with high orthogonality for multidimensional separation of phosphopeptides. Anal Chem. 2010;82:53–6. doi: 10.1021/ac9023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brosch M, Yu L, Hubbard T, Choudhary J. Accurate and sensitive peptide identification with Mascot Percolator. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3176–81. doi: 10.1021/pr800982s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Wen Z, Washburn MP, Florens L. Refinements to label free proteome quantitation: how to deal with peptides shared by multiple proteins. Anal Chem. 2010;82:2272–81. doi: 10.1021/ac9023999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zybailov B, Mosley AL, Sardiu ME, Coleman MK, Florens L, Washburn MP. Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2339–47. doi: 10.1021/pr060161n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt H, Gelhaus C, Nebendahl M, Lettau M, Watzl C, Kabelitz D, et al. 2-D DIGE analyses of enriched secretory lysosomes reveal heterogeneous profiles of functionally relevant proteins in leukemic and activated human NK cells. Proteomics. 2008;8:2911–25. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Orthogonality of separation in two-dimensional liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6426–34. doi: 10.1021/ac050923i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strader MB, Tabb DL, Hervey WJ, Pan C, Hurst GB. Efficient and specific trypsin digestion of microgram to nanogram quantities of proteins in organic-aqueous solvent systems. Anal Chem. 2006;78:125–34. doi: 10.1021/ac051348l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang KS, Ritz J, Frank DA. IL-2 induces STAT4 activation in primary NK cells and NK cell lines, but not in T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang KS, Frank DA, Ritz J. Interleukin-2 enhances the response of natural killer cells to interleukin-12 through up-regulation of the interleukin-12 receptor and STAT4. Blood. 2000;95:3183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyama S. Augmented human-tumor-cytolytic activity of peripheral blood lymphocytes and cells from a mixed lymphocyte/tumor culture activated by interleukin-12 plus interleukin-2, and the phenotypic characterization of the cells in patients with advanced carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123:478–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01192201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gollob JA, Mier JW, Veenstra K, McDermott DF, Clancy D, Clancy M, et al. Phase I trial of twice-weekly intravenous interleukin 12 in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma: ability to maintain IFN-gamma induction is associated with clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1678–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersen JN, Mortensen OH, Peters GH, Drake PG, Iversen LF, Olsen OH, et al. Structural and evolutionary relationships among protein tyrosine phosphatase domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7117–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7117-7136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simoncic PD, Lee-Loy A, Barber DL, Tremblay ML, McGlade CJ. The T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase is a negative regulator of Janus family kinases 1 and 3. Curr Biol. 2002;12:446–53. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers MP, Andersen JN, Cheng A, Tremblay ML, Horvath CM, Parisien JP, et al. TYK2 and JAK2 are substrates of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47771–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aoki N, Matsuda T. A cytosolic protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B specifically dephosphorylates and deactivates prolactin-activated STAT5a and STAT5b. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39718–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurki P, Lotz M, Ogata K, Tan EM. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)/cyclin in activated human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:4114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohler T, Nolting J, Kamar N, Gurragchaa P, Reisener K, Glander P, et al. Validation of immunological biomarkers for the pharmacodynamic monitoring of immunosuppressive drugs in humans. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:77–86. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318030a40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barten MJ, Tarnok A, Garbade J, Bittner HB, Dhein S, Mohr FW, et al. Pharmacodynamics of T-cell function for monitoring immunosuppression. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:50–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millan O, Benitez C, Guillen D, Lopez A, Rimola A, Sanchez-Fueyo A, et al. Biomarkers of immunoregulatory status in stable liver transplant recipients undergoing weaning of immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Immunol. 2010;137:337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niwa M, Miwa Y, Kuzuya T, Iwasaki K, Haneda M, Ueki T, et al. Stimulation index for PCNA mRNA in peripheral blood as immune function monitoring after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:1411–4. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a277bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosental B, Brusilovsky M, Hadad U, Oz D, Appel MY, Afergan F, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is a novel inhibitory ligand for the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44. J Immunol. 2011;187:5693–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosental B, Hadad U, Brusilovsky M, Campbell KS, Porgador A. A novel mechanism for cancer cells to evade immune attack by NK cells: The interaction between NKp44 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:572–4. doi: 10.4161/onci.19366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boles KS, Stepp SE, Bennett M, Kumar V, Mathew PA. 2B4 (CD244) and CS1: novel members of the CD2 subset of the immunoglobulin superfamily molecules expressed on natural killer cells and other leukocytes. Immunol Rev. 2001;181:234–49. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1810120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaidya SV, Stepp SE, McNerney ME, Lee JK, Bennett M, Lee KM, et al. Targeted disruption of the 2B4 gene in mice reveals an in vivo role of 2B4 (CD244) in the rejection of B16 melanoma cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:800–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim EO, Kim TJ, Kim N, Kim ST, Kumar V, Lee KM. Homotypic cell to cell cross-talk among human natural killer cells reveals differential and overlapping roles of 2B4 and CD2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41755–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinha SK, Gao N, Guo Y, Yuan D. Mechanism of induction of NK activation by 2B4 (CD244) via its cognate ligand. J Immunol. 2010;185:5205–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gray JX, Haino M, Roth MJ, Maguire JE, Jensen PN, Yarme A, et al. CD97 is a processed, seven-transmembrane, heterodimeric receptor associated with inflammation. J Immunol. 1996;157:5438–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kop EN, Matmati M, Pouwels W, Leclercq G, Tak PP, Hamann J. Differential expression of CD97 on human lymphocyte subsets and limited effect of CD97 antibodies on allogeneic T-cell stimulation. Immunol Lett. 2009;123:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haynes BF, Hemler ME, Mann DL, Eisenbarth GS, Shelhamer J, Mostowski HS, et al. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody (4 F2) that binds to human monocytes and to a subset of activated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;126:1409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moretta A, Mingari MC, Haynes BF, Sekaly RP, Moretta L, Fauci AS. Phenotypic characterization of human cytolytic T lymphocytes in mixed lymphocyte culture. J Exp Med. 1981;153:213–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan Y, Vasudevan S, Nguyen HT, Merlin D. Intestinal epithelial CD98: an oligomeric and multifunctional protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:1087–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deves R, Boyd CA. Surface antigen CD98(4 F2): not a single membrane protein, but a family of proteins with multiple functions. J Membr Biol. 2000;173:165–77. doi: 10.1007/s002320001017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warren AP, Patel K, Miyamoto Y, Wygant JN, Woodside DG, McIntyre BW. Convergence between CD98 and integrin-mediated T-lymphocyte co-stimulation. Immunology. 2000;99:62–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto YJ, Mitchell JS, McIntyre BW. Physical association and functional interaction between beta1 integrin and CD98 on human T lymphocytes. Mol Immunol. 2003;39:739–51. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cantoni C, Bottino C, Augugliaro R, Morelli L, Marcenaro E, Castriconi R, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of IRp60, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that functions as an inhibitory receptor in human NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3148–59. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3148::AID-IMMU3148>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ju X, Zenke M, Hart DN, Clark GJ. CD300a/c regulate type I interferon and TNF-alpha secretion by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulated with TLR7 and TLR9 ligands. Blood. 2008;112:1184–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark GJ, Rao M, Ju X, Hart DN. Novel human CD4+ T lymphocyte subpopulations defined by CD300a/c molecule expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1126–35. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alvarez Y, Tang X, Coligan JE, Borrego F. The CD300a (IRp60) inhibitory receptor is rapidly up-regulated on human neutrophils in response to inflammatory stimuli and modulates CD32a (FcgammaRIIa) mediated signaling. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakahashi-Oda C, Tahara-Hanaoka S, Honda S, Shibuya K, Shibuya A. Identification of phosphatidylserine as a ligand for the CD300a immunoreceptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:646–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deblandre GA, Marinx OP, Evans SS, Majjaj S, Leo O, Caput D, et al. Expression cloning of an interferon-inducible 17-kDa membrane protein implicated in the control of cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23860–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedman RL, Manly SP, McMahon M, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of interferon-induced gene expression in human cells. Cell. 1984;38:745–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang G, Xu Y, Chen X, Hu G. IFITM1 plays an essential role in the antiproliferative action of interferon-gamma. Oncogene. 2007;26:594–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Santo JP. Natural killer cell developmental pathways: a question of balance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:257–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.