Abstract

Long-term exposure to environmental oxidative stressors, like the herbicide paraquat (PQ), has been linked to the development of Parkinson's disease (PD), the most frequent neurodegenerative movement disorder. Paraquat is thus frequently used in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and other animal models to study PD and the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons (DNs) that characterizes this disease. Here, we show that a D1-like dopamine (DA) receptor, DAMB, actively contributes to the fast central nervous system (CNS) failure induced by PQ in the fly. First, we found that a long-term increase in neuronal DA synthesis reduced DAMB expression and protected against PQ neurotoxicity. Secondly, a striking age-related decrease in PQ resistance in young adult flies correlated with an augmentation of DAMB expression. This aging-associated increase in oxidative stress vulnerability was not observed in a DAMB-deficient mutant. Thirdly, targeted inactivation of this receptor in glutamatergic neurons (GNs) markedly enhanced the survival of Drosophila exposed to either PQ or neurotoxic levels of DA, whereas, conversely, DAMB overexpression in these cells made the flies more vulnerable to both compounds. Fourthly, a mutation in the Drosophila ryanodine receptor (RyR), which inhibits activity-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+, also strongly enhanced PQ resistance. Finally, we found that DAMB overexpression in specific neuronal populations arrested development of the fly and that in vivo stimulation of either DNs or GNs increased PQ susceptibility. This suggests a model for DA receptor-mediated potentiation of PQ-induced neurotoxicity. Further studies of DAMB signaling in Drosophila could have implications for better understanding DA-related neurodegenerative disorders in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress, i.e. the uncontrolled accumulation of reactive oxygen species, plays a central role in aging and major age-related human diseases such as cancer (1), heart failure (2), neurodegenerative syndromes (3,4) and, specifically, Parkinson's disease (PD) (5–8). Parkinson's disease is a multifactorial movement disorder resulting from the dysfunction and loss of dopaminergic neurons (DNs) in the midbrain substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) (9–11). No treatment is currently known that could halt or slow the progression of neurodegeneration in this disorder. Parkinson's disease and related diseases are generally sporadic, i.e. without obvious heritability, but familial cases have been described. Several of the ∼15 PARK genes whose mutations cause various forms of Parkinsonism were shown to be involved in mitochondrial quality control and oxidative stress pathways (7,12). Oxidation of dopamine (DA) itself, or of its metabolites, produces reactive radicals and quinones that can damage cells and interact with PD-related proteins (13–15). This combined with the physiological features of the SNpc DNs, including prominent Ca2+ entry through L-type channels, could account for the specific vulnerability of these cells in PD (6,16,17).

Human epidemiological studies showed that long-term exposure to environmental free-radical generators, such as the herbicide paraquat (PQ, 1,1′-dimethyl-4–4′-bipyridinium) or the insecticide rotenone, is a risk factor for the development of PD (18–21). Although the molecular mechanisms of cytotoxicity of PQ and rotenone appear distinct and have not been fully established in vivo (22–24), they are known to increase superoxide ion production by mitochondria and generate oxidative damage (23,25,26). These two neurotoxicants have thus been frequently used to mimic PD and study oxidative stress-induced motor deficits and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in animal models such as rodents (22,27–31) and Drosophila (32–38). Melatonin, a potent hydroxyl radical scavenger, efficiently protects the flies against these pesticides (32,39).

In Drosophila, DA is both an essential neuromodulator and a precursor of molecules required for hardening and pigmentation of the external cuticle (40,41). DA released from fly neurons interacts with specific G protein-coupled DA receptors, either of the D1 or D2 subtypes (42,43), including D1-like dDA1 and DAMB, which play key roles in arousal and memory (44,45). Here, we show that long-term overexpression of the DA-synthesizing enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the nervous system prolongs the survival of adult PQ-intoxicated flies, and we provide evidence that enhanced PQ resistance results from a down-regulation of the DAMB receptor. Moreover, an augmentation of DAMB expression appears to underlie the age-related increase in PQ susceptibility of young adult flies. This suggests that DA signaling modulates oxidative stress resistance in the Drosophila nervous system. From these and further results, we propose a model for PQ neurotoxicity in which CNS disturbance would result from the self-reinforcing effects of PQ-induced oxidative stress and a noxious intracellular Ca2+ signaling mediated by DA receptor overactivation.

RESULTS

Long-term TH overexpression protects against PQ neurotoxicity

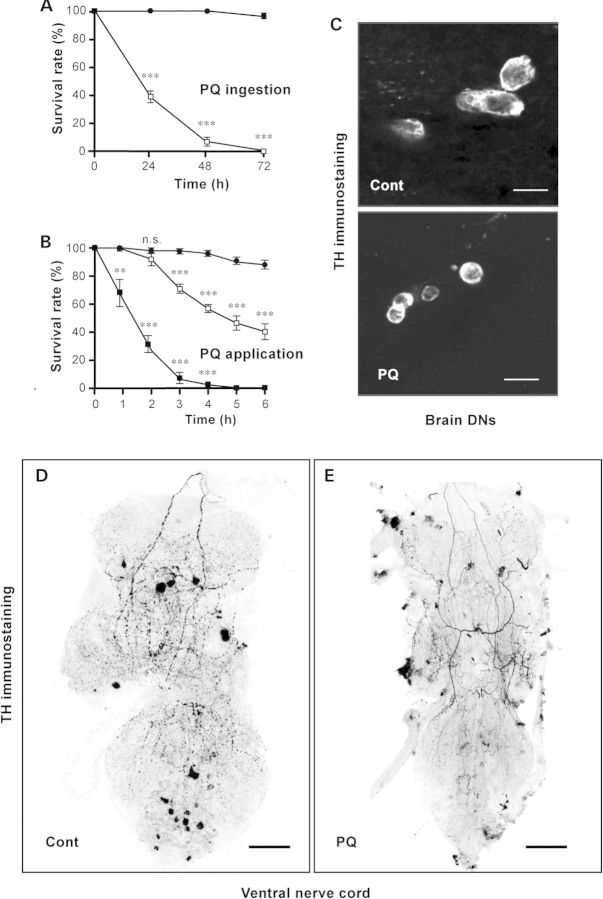

Survival of the wild-type female Drosophila fed with 20 mm PQ diluted in a 2% sucrose solution was at most 72 h, with ∼60% of the flies apparently dead after 24 h (Fig. 1A). Because dietary PQ strongly inhibits food intake in flies (46), we alternatively applied the drug directly onto the anterior notum of decapitated adult Drosophila, close to the ventral nerve cord (VNC), in order to bypass feeding and digestive tract absorption. Headless flies survive well up to 3 days when conserved in a moist environment at 25°C. They maintain a normal standing posture, a vigorous righting response, and they can respond to mechanical or pharmacological stimulations with grooming and coordinated locomotion (47–50). We observed that death occurred more rapidly when PQ was directly applied to the VNC, compared with oral ingestion. A single 5-s application of a drop of 20 or 80 mm PQ diluted in Ringer's solution killed 60–70% of the decapitated flies in ∼6 and 2 h, respectively (Fig. 1B). No significant difference in PQ vulnerability was observed among various control strains in these conditions (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Ingested PQ induced characteristic morphological alterations of brain DNs, whose cell bodies became smaller and rounded, suggestive of an entry of these cells into apoptosis, as shown in Figure 1C for the PPL2 cluster. Similar changes in neuronal morphology were previously described for the PAL, PPL1, and PPM2 clusters (33). Direct application of PQ also altered dopaminergic neuron structure in the VNC, leading, after 2 h, to a severe reduction or loss of their axonal varicosities, which are normally widespread in the ganglion neuropil of untreated flies (Fig. 1D and E).

Figure 1.

Paraquat-induced lethality and morphological alterations of Drosophila DA neurons. (A and B) Survival rate of wild-type Canton-S Drosophila either fed with a sucrose solution containing PQ (dietary ingestion) (A) or after a 5-s application of the drug diluted in Ringer's solution to the VNC of decapitated flies (direct application) (B). PQ concentrations were as follows: 0 (closed circles), 20 (open squares), or 80 mm (closed squares). (C) Structure of brain DNs from wild-type Drosophila fed for 24 h on a sucrose solution containing either no PQ (control, upper panel) or 20 mm PQ (lower panel). Brains were then dissected and stained with anti-TH antibodies. The pictures show part of the dorsolateral posterior protocerebral 2 (PPL2) neuronal cluster. Dopaminergic cell bodies of PQ-treated flies appeared smaller and rounder with shrunken nuclei. (D and E) Whole-mount VNC of decapitated Drosophila dissected 2 h after a 5-s application of either Ringer's alone (control) (D) or 80 mm PQ (E) and then immunostained for TH. Confocal projections were converted into negative images to improve visibility. DN axonal varicosities that are widespread in the VNC of control flies appear to be much reduced in size or lost (98.4 ± 0.005%) in PQ-treated VNC. Scale bars: (C) 10 µm, (D and E) 50 µm.

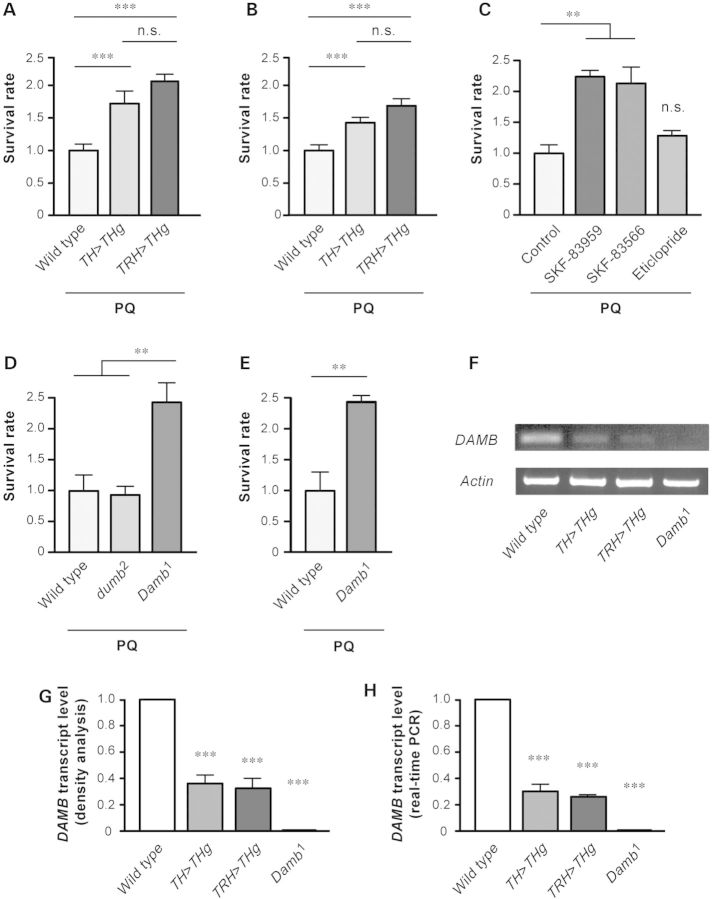

In Drosophila, as in mammals, the TH enzyme is specifically required for DA production in the CNS (41) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). To test for an effect of increased DA biosynthesis on PQ susceptibility, we overexpressed genomic Drosophila TH (DTHg) from the late embryonic stage and thereafter in DNs, under transcriptional control of the TH-GAL4 driver (51). Resistance of these TH>THg flies to PQ intoxication was significantly enhanced compared with the wild type, leading to increased survival rates at 24 h after drug ingestion and 2 h after direct application to the VNC (Fig. 2A and B). Because serotonergic neurons express dopa decarboxylase (Ddc), the second enzyme in the DA biosynthesis pathway (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), ectopic expression of DTHg can force these cells to produce DA. Surprisingly, TH expression selectively in serotonergic neurons with the TRH-GAL4 driver also resulted in significant protection against PQ (Fig. 2A and B). The survival rate of PQ-ingested TRH>THg flies at 24 h was double that of the wild type (Fig. 2A). Thus, enhanced PQ resistance in adult flies can result from a long-term increase in DA synthesis either in DNs or in serotonergic neurons, suggesting that a critical factor for neuroprotection is not the DA level in DNs but rather the amount of DA released in the CNS.

Figure 2.

Down-regulation of the DA receptor DAMB protects Drosophila against PQ-induced oxidative stress. (A) Survival rate of wild-type flies fed for 24 h with sucrose plus 20 mm PQ, compared with TH-GAL4; UAS-DTHg flies overexpressing TH in DNs (TH>THg), and TRH-GAL4; UAS-DTHg flies ectopically expressing TH in serotonergic neurons (TRH>THg). (B) Survival rate of decapitated flies of similar genotypes as in (A) 2 h after a 5-s application of 80 mm PQ dissolved in Ringer's to the VNC. (C) Effect of DA receptor antagonists. Survival rate of decapitated flies was monitored 1 h 30 min after brief application of a drop of Ringer's solution containing either PQ alone (control) or PQ plus D1 antagonists SKF-83959 or SKF-83566, or D2 antagonist eticlopride. Protection was observed with the D1-specific antagonists. (D) PQ susceptibility of decapitated D1-like DA receptor mutants. Whereas the survival rate of dumb2 is comparable with wild type, the Damb1 strain shows higher resistance to PQ. (E) Survival of intact Damb1 flies after PQ ingestion is similarly increased compared with wild type. In (A)–(E), values were normalized to the mean survival rate of wild-type controls. (F–H) TH overexpression decreases the DAMB transcript level in adult flies. (F) RT-PCR from head RNAs (30 cycles of amplification) showed reduced level of DAMB transcripts, compared with wild type, after long-term TH overexpression in dopaminergic (TH>THg) or serotonergic (TRH>THg) neurons, and their absence in the Damb1 mutant. Density analysis of RT-PCR products (G) or real-time PCR experiments (H) yielded similar quantitative results.

Enhanced PQ tolerance correlates with down-regulation of the DA receptor DAMB

Released DA interacts with specific membrane receptors. We tested whether this interaction plays a role in the control of PQ neurotoxicity. DA receptor antagonists were applied together with PQ to the nerve cord of decapitated Drosophila. Application of either SKF-83959 or SKF-83566, two specific antagonists of the D1 receptor subtypes, markedly enhanced resistance of the flies against PQ. Ninety minutes after PQ application, the survival rate of headless flies increased around twofold in the presence of these antagonists compared with controls treated with PQ alone (Fig. 2C). In contrast, eticlopride, a specific antagonist of D2 receptors previously shown to be effective in Drosophila (47), had no significant effect on PQ toxicity (Fig. 2C). Therefore, D1 DA receptor antagonists can efficiently protect against PQ poisoning in Drosophila.

Two D1-like receptors are known in Drosophila: dDA1 and DAMB. We determined the PQ resistance of Damb1, a viable null DAMB mutant, and dumb2, a hypomorphic dDA1 mutant (Fig. 2D). After 2 h of PQ poisoning, the survival rate of decapitated Damb1 flies was found to be ∼2.5 times higher than that of the wild-type Canton S (CS) flies. In contrast, survival of dumb2 flies was similar to CS. Damb1 flies were also much more resistant than the wild type when PQ intoxication was carried out by dietary ingestion (Fig. 2E). The comparable stress-protective effects of DAMB inactivation and long-term enhanced DA suggested that DAMB expression could be altered in a compensatory manner by TH overexpression. To test this hypothesis, we measured the DAMB transcript level in adult heads of flies overexpressing TH in dopaminergic or serotonergic neurons: these transgenic flies showed marked down-regulation of DAMB expression to ∼30% of the wild type, and no DAMB mRNA was detected in Damb1 mutants (Fig. 2F–H). Two independent sets of experiments using different techniques, i.e. density analysis of RT-PCR products (Fig. 2G) and real-time PCR (Fig. 2H), showed similar quantitative results. This strengthens the conclusion that DAMB is down-regulated in adult flies when TH is overexpressed in dopaminergic or serotonergic neurons and that the DAMB transcript is absent in Damb1 mutants (as also shown in Fig. 4B). Thus, various treatments or mutations that resulted in inactivation or down-regulation of DAMB, either application of D1 antagonists, DAMB mutation or long-term augmentation of DA synthesis, all led to the common effect of increased PQ tolerance. Therefore, DAMB signaling appears to contribute significantly to PQ-induced neurotoxicity in Drosophila.

Figure 4.

DAMB is expressed in GNs of the VNC. (A) Sketch of Glu- (green circles) and DA- (red circles) synthesizing cells in the VNC. The regions corresponding to the thoracic ganglia (tho) and fused abdominal neuromeres (abd) are marked. Circles represent neuronal cell bodies. The gray rectangle indicates the region magnified in panels (C) and (D), and the dashed rectangle does the same for panels (E) and (G). (B) RT-PCR experiment (40 cycles) showing that DAMB is expressed both in the head and thorax of wild-type Canton-S flies and is absent from both tissues in Damb1 mutant. (C) Presence of DAMB immunoreactivity in adult VNC of wild-type flies. DAMB is expressed particularly in neuronal cell bodies that may correspond to Glu-releasing motor neurons. (D) No DAMB immunoreactivity was detected in VNC of Damb1 mutant. (E–G) Double staining with anti-DAMB (magenta) and anti-GFP (green) antibodies in VNC of VGlut-GAL4; UAS-mCD8::GFP flies, (E) anti-DAMB, (F) merge and (G) anti-GFP. Large arrows show cell bodies of GNs expressing DAMB at various levels. Thin arrows indicate cells expressing DAMB and not GFP. (H–J) Double staining with anti-TH (magenta) and anti-GFP (green) antibodies in VNC of VGlut-GAL4; UAS-VGlut::GFP flies. (H) anti-TH, (I) merge and (J) anti-GFP. DN axonal varicosities and GN nerve endings are widely distributed and overlap in several regions of the VNC neuropil. (K–M) Magnification of the regions indicated by white rectangles in I. Examples of overlapping neuronal domains are marked (arrowheads). Scale bars: (C and D) 25 µm, (E–G) 5 µm, (H–J) 50 µm and (K–M) 20 µm.

Age-related decline in PQ resistance correlates with DAMB expression

Newly eclosed 1-day-old wild-type Drosophila have been reported to be more resistant to PQ exposure than 5- or 10-day-old flies, which were more sensitive to the toxin (52,53), despite no significant difference in food intake between PQ-treated 1- and 5-day-old flies (52). We, indeed, found that the PQ resistance of wild-type flies strongly decreased during the first 2 weeks of adult life: ∼95% of the 1-day-old flies survived 24 h after PQ exposure against only 8% of the 15-day-old flies (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, DAMB expression level was found to augment progressively during the same period, reaching twice as high in 15-day-old flies compared with newly eclosed flies (Fig. 3B and C). We therefore tested the evolution with age of PQ susceptibility in the Damb1 mutant. Strikingly, the mutant flies were strongly resistant at all ages between 1 and 15 days after eclosion (Fig. 3A). This suggests that DAMB is required for the progressively higher sensitivity of aging flies to PQ-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 3.

Age-related increase in Drosophila PQ susceptibility appears to be DAMB dependent. (A) Whereas newly eclosed (1-day-old) wild-type (w1118) Drosophila were quite resistant to PQ exposure, susceptibility markedly increased during the first 2 weeks of adult life. In contrast, resistance of w; Damb1 mutant flies after PQ ingestion was similarly high at all ages during this period. (B) RT-PCR experiments (30 cycles of amplification) demonstrated that DAMB expression progressively increased with age in wild-type flies during the first 2 weeks after adult eclosion. (C) Quantification of the RT-PCR products from 3 to 5 independent experiments by density analysis. The relative transcript abundance of the DA receptor in 15-day-old flies was found to be about twice as much as in 1-day-old flies.

DAMB inactivation in glutamatergic neurons alleviates PQ neurotoxicity

The DAMB receptor is known to be expressed in the mushroom bodies (45,54), a fly brain center involved in the regulation of associative learning and sleep. As described earlier, DAMB inactivation enhanced the resistance of PQ-fed Drosophila or of decapitated flies when PQ was applied to the nerve cord. We looked, therefore, for DAMB expression in the VNC as well. The structure of the VNC with the relative localization of Glu- and DA-releasing neurons is schematically depicted in Figure 4A. RT-PCR experiments showed that DAMB mRNA is detectable in both the head and thorax of adult wild-type Drosophila but not in the Damb1 mutant (Fig. 4B). Note that the DAMB signal appears stronger in this figure because 40 cycles of amplification were performed instead of 30 in Figures 2F and 3B, as described in Materials and Methods. DAMB-specific immunostaining confirmed that this receptor is widely expressed in the VNC, specifically in areas containing glutamatergic neurons (GNs) (Fig. 4C). No immunostaining was observed in the VNC of mutant Damb1 flies (Fig. 4D). We used the VGlut-GAL4 driver to express GFP selectively in GNs. Double staining for DAMB and GFP showed that DAMB could be detected in GNs (large arrows) and in other cells (thin arrows) in the VNC (Fig. 4E–G). Expression of a synaptic vesicle marker, VGlut::GFP, in GNs revealed that glutamatergic nerve endings are widely distributed in the VNC neuropil in regions that also contain dense dopaminergic arborizations (Fig. 4H–J, showing co-immunostaining against GFP and TH). Higher magnification demonstrates that dopaminergic projections and glutamatergic nerve terminals are often overlapping (Fig. 4K–M, arrowheads). Previous studies in Drosophila and other insects suggest that these glutamatergic terminals could originate from Glu-releasing CNS interneurons or, alternatively, from motor axon collaterals (55–57).

To determine whether DAMB signaling in GNs contributes to PQ-induced lethality, we inactivated DAMB selectively in GNs by targeted RNA interference (RNAi). This led to a significant increase in fly survival under PQ poisoning, by either dietary ingestion or after application of the drug to decapitated flies, compared with the control GAL4 and UAS-RNAi strains (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, expression of the double-stranded DAMB RNAi in DNs with TH-GAL4 had no effect on PQ susceptibility (Fig. 5C). Conversely, we overexpressed DAMB in GNs and this indeed caused a higher susceptibility of the flies to PQ lethal effects (Fig. 5D). We then tested the effect of DAMB overexpression on Drosophila survival in the absence of PQ. This led to contrasting results depending on the cell type. Overexpression either in GNs, where DAMB is normally expressed, in serotonergic neurons, or in glial cells was without effect. In contrast, DAMB expression in all neurons as well as in dopaminergic or cholinergic neurons resulted in fly death at the pupal stage (Table 1). However, we observed that panneuronal expression of dDA1, the other D1-like receptor in flies, did not alter Drosophila survival in any case. This suggests that DAMB signaling can be specifically neurotoxic, either when this receptor is overexpressed in certain neuronal subpopulations, leading to hampered fly development, or in the adult stage when its activation is combined with an exposure to pro-oxidant molecules such as PQ.

Figure 5.

DAMB inactivation in GNs enhances PQ tolerance. (A and B) Survival of decapitated (A) and intact (B) flies at 2 and 48 h, respectively, after PQ exposure. The survival rate is greater for VGlut-GAL4; UAS-DAMB-IR Drosophila (VGlut>DAMB-IR), which express DAMB interfering RNA (IR) in GNs compared with control flies carrying one copy of VGlut-GAL4 or UAS-DAMB-IR alone. (C) Survival of decapitated TH-GAL4; UAS-DAMB-IR flies (TH>DAMB-IR) that express DAMB IR in DNs is, in contrast, similar to controls. (D) PQ susceptibility of VGlut-GAL4; UAS-DAMB flies (VGlut>DAMB) that overexpress DAMB in GNs is significantly increased compared with controls. (E and F) Effect of in vivo stimulation of Glu- or DA-releasing neurons on PQ resistance. (E) Survival of decapitated VGlut-GAL4; UAS-dTrpA1 (VGlut>dTrpA1) Drosophila incubated for 2 h at 31°C in the presence of PQ is decreased compared with similarly treated control flies carrying one copy of either VGlut-GAL4 or UAS-dTrpA1 alone. (F) Same experiment as in D with TH-GAL4; UAS-dTrpA1 flies (TH>dTrpA1). Short-term stimulation of DNs also markedly increased PQ neurotoxicity. In all panels, values were normalized to the mean survival rate of respective UAS strain controls.

Table 1.

Lethal effect of DAMB expression in selective neuronal subpopulations

| Driver name | Driver pattern | Score of adult females |

Score of adult malesb | Phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cy | Cy+a | Cy | Cy+a | |||

| elav-GAL4b | All neurons | 35 | 0 (0) | 33 | 98 (74.8) | Lethal |

| repo-GAL4 | All glial cells | 17 | 11 (39.3) | 12 | 13 (52.0) | Not lethal |

| TH-GAL4 | Dopaminergic | 49 | 0 (0) | 63 | 0 (0) | Lethal |

| TRH-GAL4 | Serotonergic | 56 | 45 (44.5) | 48 | 27 (36.0) | Not lethal |

| Cha-GAL4 | Cholinergic | 71 | 0 (0) | 57 | 0 (0) | Lethal |

| VGlut-GAL4 | Glutamatergic | 26 | 38 (59.4) | 23 | 28 (54.9) | Not lethal |

Female UAS-DAMB/CyO flies were mated to male flies with hemizygous or homozygous insertions of the indicated GAL4 drivers. Survival was determined by scoring the relative number of Cy+ adult flies in the progeny. The DAMB receptor did not hinder Drosophila survival when it was expressed in either glial cells, or selectively in glutamatergic or serotonergic neurons. In contrast, DAMB expression in all neurons, or restricted to dopaminergic or cholinergic neurons, caused lethality prior to adult eclosion.

aPercent of Cy+ progeny are in italics.

bBecause elav-GAL4 is inserted on the X chromosome and male driver flies were used, only the female progeny of this cross inherited the GAL4 transgene.

Short-term stimulation of GNs or DNs increases PQ susceptibility

DAMB activation elevates intracellular cAMP and Ca2+ levels (58), which in turn could potentiate neuronal activity and neurotransmitter release. dTRPA1 is a cation-permeant thermal sensor channel that depolarizes neurons when the ambient temperature is raised above 25°C (59). We expressed dTRPA1 in GNs to assess whether the activity of these neurons can modulate PQ toxicity. Headless adult flies were treated with PQ or plain Ringer's solution and then incubated at 31°C for 2 h. We observed that the expression of dTRPA1 in GNs did not trigger paralysis of the flies at 31°C, indicating that neuromuscular junctions were still functional under this condition. In the absence of PQ treatment, most of the dTRPA1-expressing flies survived the 2 hours of neuronal overstimulation (80% compared with 93% for control flies that did not express dTRPA1). In contrast, the survival rate of PQ-intoxicated dTRPA1-expressing flies was reduced by half compared with that of the control flies containing UAS-dTRPA1 or VGlut-GAL4 alone (Fig. 5E). Similarly, overstimulation of DNs with dTRPA1 for 2 h heavily decreased the resistance of the flies against PQ (Fig. 5F): survival rate dropped to ∼5 times lower than the UAS-dTRPA1 and TH-GAL4 controls. This last result contrasts with the protective effect observed in adult flies after a long-term augmentation of DA biosynthesis in the CNS during development (see Fig. 2A and B). Although short-term stimulation of DNs in the adult fly CNS aggravates the detrimental effects of oxidative stress (Fig. 5F), a long-term increase in DA release compensates for this effect by constitutively down-regulating the DAMB receptor (Fig. 2F–H).

DAMB inactivation protects against DA neurotoxicity

After PQ exposure, DAMB could be overactivated by the large amounts of DA likely to be released from PQ-damaged DNs, thus impairing Drosophila survival under oxidative stress. As a further test of this hypothesis, we applied various dilutions of DA directly to the nerve cord of decapitated Drosophila in the absence of PQ. Interestingly, DA levels of >10 mm were found to be lethal in these conditions in a dose-dependent manner, with a median lifespan of ∼45 min at 50 mm DA (Fig. 6A). Here again, the Damb1 mutant strain was markedly more resistant than the wild type to DA toxicity (Fig. 6B): survival rate of Damb1 Drosophila 2 h after exposure to 35 mm DA was ∼1.7 times higher than that of similarly treated wild-type flies and close to the survival rate of the untreated wild type. Similar to the results of experiments conducted with PQ (Fig. 5A and B), we found that targeted inactivation of DAMB by RNAi in GNs and DAMB overexpression in GNs, respectively, increased and decreased the survival of headless Drosophila 2 h after DA exposure (Fig. 6C and D). This suggests that DA neurotoxicity in Drosophila in part results from DAMB overactivation in GNs.

Figure 6.

DAMB inactivation protects decapitated Drosophila against DA neurotoxicity. (A) Survival of decapitated wild-type (Canton-S) flies was monitored at various times (15, 30, 45 and 60 min) after a 5-s application of a drop of DA dissolved in Ringer's at the indicated concentration (10, 20, 50 or 100 mm). DA levels of >10 mm were found to be toxic in a dose-dependent manner under these conditions. (B) Survival rate of decapitated flies 2 h after a 5-s application of Ringer's solution alone (R) or 35 mm DA dissolved in Ringer's (DA). Damb1 mutants resist DA toxicity better than wild-type flies. (C) Survival of decapitated Drosophila 2 h after a 5-s exposure to 35 mm DA is significantly prolonged for VGlut-GAL4; UAS-DAMB-IR flies (VGlut>DAMB-IR) that express DAMB interfering RNA in GNs as compared with control flies carrying one copy of VGlut-GAL4 or UAS-DAMB-IR alone. (D) DA susceptibility of VGlut-GAL4; UAS-DAMB Drosophila (VGlut>DAMB) that overexpress DAMB in Glu neurons is markedly increased compared with controls. Values were normalized to the mean survival rate of UAS strain controls. Note that all experiments in this figure were performed in the absence of PQ.

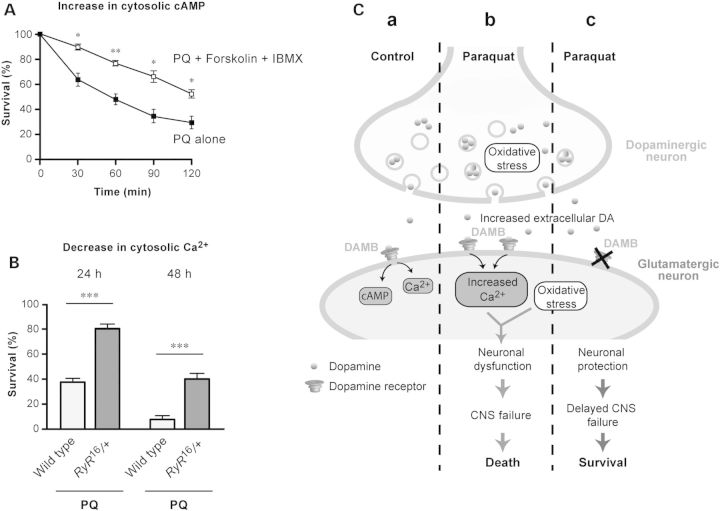

Decreased cytosolic Ca2+ protects against PQ neurotoxicity

As DAMB activation can elevate both cytosolic cAMP and Ca2+ levels, we tried to determine which of these second messengers could be involved in the detrimental effects induced by the DA receptor under oxidative stress. To raise the level of cAMP in cells, we applied PQ together with forskolin and IBMX to the trunk of decapitated flies. Compared with controls with PQ only, we found that the resistance of the flies with a higher level of cAMP was increased (Fig. 7A). This result agrees with the view that cAMP generally has a neuroprotective effect in the nervous system (38,60–62). This suggests that cAMP may not take part in the neurotoxic signaling triggered by the DAMB receptor.

Figure 7.

Mechanisms of DAMB-mediated potentiation of PQ susceptibility in Drosophila. (A) Survival of decapitated wild-type Drosophila was monitored at various times after a 5-s application of a PQ solution mixed (open squares) or not (closed squares) with forskolin plus IBMX, as described in Materials and Methods. Increased cAMP levels appeared to protect the flies against PQ neurotoxicity. (B) Heterozygous RyR16 mutants that have a reduced level of ryanodine receptor calcium channels survived in significantly higher numbers compared with wild-type flies either at 24 or 48 h after PQ ingestion. This suggests a primary role for cytosolic Ca2+ in the PQ toxicity pathway. (C) Proposed model of PQ neurotoxicity in flies. (a) In physiological conditions, DA release and DAMB-mediated signaling are not neurotoxic. (b) In naïve flies exposed to PQ, high amounts of DA released from oxidative stress-injured DNs would overactivate DAMB. Neuronal dysfunction would then result from two synergistic causes: on the one hand, elevated oxidative stress caused by PQ absorption, and on the other hand, aberrant DAMB activation leading to increased cytosolic Ca2+ through the ryanodine receptor. This would ultimately cause CNS failure and precipitate organism death. (c) In Damb1 mutants or in flies with constitutively higher DA synthesis, DAMB deficiency or DAMB down-regulation, respectively, alleviate PQ neurotoxicity, mediating CNS protection and prolonged Drosophila survival. Such a modulation of DAMB expression might be used in wild-type flies as an adaptive mechanism to increase oxidative stress tolerance.

As shown in Figure 5E and F, we have found that increasing the level of cations in neurons using the dTRPA1 channel made the flies more susceptible to PQ, arguing for a role of Ca2+ in PQ neurotoxicity. To test in reverse for an effect of reduced intracellular Ca2+, we determined the PQ resistance of a heterozygous mutant of the single ryanodine receptor (RyR) in flies, RyR16 (63). Ryanodine receptor channels are major mediators of activity-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (64,65), and the RyR16 mutation was previously shown to suppress Aβ neurotoxicity in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease (66). Interestingly, we found that the RyR16 mutant flies were markedly resistant to PQ exposure, to an extent comparable to that of the Damb1 mutants (Fig. 7B). This shows that RyR is a component of the PQ-induced cell death pathway and suggests that DAMB contributes to PQ toxicity at least in part by increasing the level of cytosolic Ca2+ in neurons.

DISCUSSION

Neuronal targets of PQ in Drosophila

Paraquat has long been used in Drosophila and other species to study mechanisms of oxidative stress resistance and to model aging or PD (26,33,39,53,67–73). Advantages of this compound include water solubility, its ability to cross the digestive and blood–brain barriers and its ability to quickly generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which cause oxidative damage. In Drosophila, PQ is generally administered by feeding for 1–2 days (74). However, this drug was previously shown to have a strong anorexigenic effect in flies (46). Here, we introduce an alternative technique for PQ exposure, i.e. its direct application onto the anterior notum of decapitated Drosophila. Such a behaviorally active preparation was used in previous works for pharmacological studies of biogenic amines (47–49,75,76). This method allows for PQ to diffuse rapidly into the VNC, thus avoiding the use of sucrose solution and digestive tract absorption and also minimizing the time for experiments because lethality occurs a few hours after the brief (5-s) drug application. A potential concern is that the brain and other parts of the CNS located in the head are also oxidatively damaged following PQ ingestion and are absent in decapitated flies. Although it is likely that the head tissues contribute to PQ susceptibility in entire flies, we always found qualitatively similar results in survival tests when comparing PQ ingestion and direct application to decapitated animals, as shown here in Figures 1, 2 and 5. This shows that both methods can be used with confidence to analyze PQ neurotoxicity effects.

Because PQ is an environmental risk factor for PD (18,77) that causes selective loss of SNpc DNs in animal models (78–80), it is essential to investigate the relationship between PQ-induced toxicity and the neural dopaminergic system. The selective susceptibility of SNpc neurons to PD factors is thought to arise in part from the pro-oxidant properties of DA and of its metabolites (13–15,17). This suggests that increasing DA levels in neurons should enhance PQ susceptibility. Intriguingly, a previous study in Drosophila showed that mutations that augment DA levels have the opposite effect, causing enhanced PQ tolerance, whereas mutations that diminish DA pools increase fly vulnerability (33). Here, we found that increasing DA synthesis in neurons, by overexpressing the TH gene during fly development, extended PQ tolerance both after ingestion and direct application of the toxin. PQ-induced neurotoxicity appears therefore to be a primary cause of death in Drosophila that precedes a slower systemic organ failure.

Surprisingly, a similar protective effect was observed when DA synthesis was increased either in dopaminergic or in serotonergic neurons, suggesting that a critical factor for DA-mediated neuroprotection is the amount of DA released over time in the extracellular space rather than the level of DA inside DNs. Consistent with this interpretation, it was reported that flies overexpressing throughout life the vesicular monoamine transporter in DNs, a genetic way to increase DA release, showed enhanced resistance to PQ (36). We subsequently gathered an array of evidence agreeing with this hypothesis and arguing for the involvement of a DA receptor in PQ susceptibility (Figs 2 and 3): (1) PQ tolerance is enhanced in the presence of DA receptor antagonists, (2) increased DA synthesis in neurons down-regulates the D1-like DA receptor DAMB, (3) DAMB-deficient mutants are more tolerant to PQ than wild-type flies, and (4) DAMB expression is required for the age-related decrease in PQ resistance that occurs during the first 2 weeks of adult life. This last observation suggests, quite interestingly, that the expression of a DA receptor underlies aging-associated changes in oxidative stress susceptibility in young adult flies. All together, these results lead to conclude that DAMB significantly contributes to PQ neurotoxicity and that the amount of DA released over the long term in the CNS controls Drosophila PQ resistance by modulating the expression of this receptor.

On the other hand, we also present evidence that a sudden increase in extracellular DA triggered by acute PQ intoxication in naïve flies directly contributes to fly death. PQ-induced DA release could not be demonstrated here because of the small size and low accessibility of the adult Drosophila CNS. However, it was demonstrated in mammals (see below) and suggested by the rapid morphological alterations of DNs in PQ-intoxicated flies (Fig. 1). Here, we provide two arguments in favor of this hypothesis. First, short-term stimulation of DNs by dTRPA1 activation in the adult fly CNS strongly aggravated the detrimental effects of PQ (Fig. 5F). Second, brief exposure of headless flies to DA levels of >10 mm, in the absence of PQ, was enough to induce progressive lethality in the following hours (Fig. 6A). These experiments show that a sudden increase in the extracellular DA level is neurotoxic in Drosophila. Interestingly, Damb1 mutant flies appear much less susceptible to DA toxicity than wild-type flies (Fig. 6B), as is the case with PQ susceptibility. This indicates that a significant portion of DA neurotoxicity results from the activation of DAMB. Therefore, PQ could primarily target DNs, causing abnormal extracellular DA, which would then aggravate oxidative damage by overactivating the DAMB receptors located on nerve terminals of neighboring neurons.

Because headless Damb1 mutants are also less susceptible to PQ toxicity, we searched for the presence of the DAMB receptor in the VNC. DAMB is indeed expressed in neuronal subtypes in this tissue, including glutamatergic motor neurons (Fig. 4C–G). We also find that glutamatergic projections are widespread in the VNC neuropil and often located close to dopaminergic varicosities (Fig. 4H–M), such that when large amounts of DA are released, diffusion could ensure that the DAMB receptors expressed in GNs are overactivated. Accordingly, we show that DAMB inactivation by RNAi targeted to GNs did partially protect the flies against both PQ- and DA-induced toxicity, indicating that DAMB activation in these cells contributes to the detrimental effects of those compounds (Figs 5A and B and 6C). This conclusion is strengthened by the fact that, in contrast, overexpressing DAMB in GNs increased susceptibility to either PQ or DA (Figs 5D and 6D). In accordance with these results, other reports demonstrated a central role for GNs in Drosophila PQ susceptibility. Thus, targeted expression of either the human superoxide dismutase, SOD1, or the mitochondrial heat shock protein, Hsp22, within glutamatergic motor neurons significantly increased Drosophila survival after PQ poisoning (68,81).

Mechanisms of DAMB-mediated potentiation of PQ susceptibility

How can DAMB overactivation trigger CNS failure and death under PQ exposure? It is known that increased cytosolic Ca2+ in neurons can mediate or potentiate the damaging effects of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity (82–84). One possibility, therefore, is that DAMB signaling in PQ-intoxicated flies abnormally elevates cytosolic Ca2+ and cAMP levels in neurons expressing the receptor, leading to aberrant release of Glu and other neurotransmitters and enhanced excitotoxic defects (85,86). Accordingly, we previously showed that flies with reduced Glu buffering capability are more susceptible to PQ exposure (85). This hypothesis also agrees with novel observations reported here, e.g. the localization of DAMB in GNs of the VNC, the enhanced PQ susceptibility of flies in which GNs are stimulated with the cation channel dTrpA1 (Fig. 5E) and the striking resistance of a ryanodine receptor mutant to PQ neurotoxicity (Fig. 7B). A raised level of cytosolic Ca2+ appears, therefore, to be an important component of the neurotoxic effects of PQ in Drosophila and could lead to aberrant Glu release. In contrast, an increase in cAMP level appears to be neuroprotective in the same conditions (Fig. 7A). However, more experiments are needed before we could conclude that DAMB-mediated activation of cAMP signaling does not play a role in PQ neurotoxicity. Finally, we also report that DAMB overexpression in all neurons or in specific neuronal subpopulations, i.e. dopaminergic or cholinergic cells, in the absence of PQ, arrests development of the flies during the final steps of metamorphosis (Table 1), indicating that DAMB signaling can be by itself potently neurotoxic. It can be noted that a comparable lethal effect was previously reported following panneuronal expression of the Drosophila adenosine receptor that also activates cAMP and calcium signaling (87). The reasons why DAMB overexpression in other cell types, such as GNs, serotonergic neurons and glial cells, has no detrimental effect on fly survival are still to be unraveled.

Further data from the literature support the excitotoxicity hypothesis of PQ action. In Drosophila, a hypomorphic mutant of methuselah (mth), a gene encoding a peptide-binding G protein-coupled receptor, has an increased average lifespan and enhanced resistance to various stress, including dietary PQ (53,88). Interestingly, evoked Glu release from motor neurons in this mth mutant is decreased by ∼50% owing to reduced synaptic area and synaptic vesicle density (89). Such a decrease in Glu release capability could be an advantage under oxidative stress conditions by delaying excitotoxic insults. In another system, i.e. the striatum of freely moving rats, it was demonstrated that PQ dose dependently elevates extracellular Glu and DA levels. The increase in extracellular DA level lasted for >24 h after the PQ treatment. Pharmacological evidence showed that PQ-stimulated Glu efflux initiates a cascade of excitotoxic reactions eventually leading to damage of striatal dopaminergic terminals (90).

A proposed model for PQ neurotoxicity

Overall, our results suggest that the activation state of a DA receptor contributes to oxidative stress susceptibility in Drosophila and lead to a proposed model for PQ neurotoxicity, schematically depicted in Figure 7C. Large amounts of DA released under acute oxidative stress in naïve flies would overactivate DAMB, triggering Ca2+ release in the cytosol through the ryanodine receptor, leading to neuronal dysfunction and finally causing nervous system failure. This hypothesis is supported by the following experimental evidence: extracellular DA is by itself lethal at high doses, short-term stimulation of DNs or GNs increases PQ susceptibility and, in GNs, DAMB inactivation and overexpression, respectively, protects against and sensitizes to, either PQ- or DA-induced toxicity. The fact that acute stimulation of specific neuronal subsets increased PQ susceptibility in flies importantly correlates neuronal activity and oxidative stress tolerance. In contrast, moderate and long-term augmentation of DA synthesis in the CNS down-regulate DAMB, leading to better resistance against oxidative stress.

We may infer from this model that modulating downstream DAMB signaling in response to a mild and prolonged oxidative stress exposure could elevate resistance in adult flies. Such an adaptive ‘hormetic’ effect might be used in Drosophila and other insects to survive under conditions of raised environmental stress. An adaptive increase in oxidative stress resistance was indeed recently demonstrated in Drosophila, and it was shown to depend on the induction of the Nrf2 antioxidant response pathway (91). A potential relation between DAMB signaling and the Nrf2 pathway remains to be investigated.

Parallel with human disease conditions

A role for postsynaptic D1 DA receptors in neuronal cytotoxicity is not restricted to Drosophila and has been previously reported in mammalian models in the case of striatal neurodegeneration, a symptom associated with major neurological disorders such as multiple system atrophy and Huntington's disease. The striatal GABAergic medium spiny neurons are indeed uniquely vulnerable to elevated extracellular DA levels (92,93). In these cells, D1 receptor stimulation potentiates Ca2+ influx via Glu receptors of the NMDA subtype (94,95) and stimulates the phosphorylated form of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK) via cAMP-dependent signaling (96). Both mechanisms contribute to the activation of cellular toxicity pathways, ultimately resulting in neuronal death. Such a toxic convergence of DA and Glu signals is quite similar to the mechanism of PQ neurotoxicity observed here. The Drosophila DAMB-expressing neurons and human striatal medium spiny neurons share the property of being potentially overloaded with cAMP and Ca2+ ions in conditions that abnormally increase extracellular DA levels. Further investigations on the DAMB-mediated neurotoxic pathways in Drosophila could thus lead to a better understanding of major DA-related disorders in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila culture and strains

Fly stocks were raised at 25°C on standard cornmeal-yeast-agar medium supplemented with methyl-4-hydroxy-benzoate as a mold protector, under 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle and ∼70% humidity. The following Drosophila strains were used: Canton S or w1118 as wild type; y, w for germ-line transformation; UAS-DTHg (40) to express the Drosophila TH gene; UAS-VGlut::GFP to express GFP fused to the Drosophila vesicular Glu transporter gene (VGlut), used as a synaptic vesicle marker (97); Cha-GAL4 (98), TH-GAL4 (51), TRH-GAL4 and VGlut-GAL4 that drive gene expression in cholinergic, dopaminergic, serotonergic and GNs, respectively; elav-GAL4 (99) that expresses in all neurons and repo-GAL4 (100) in all glial cells in adult flies; Damb1, a null mutant of the DopR2/DAMB receptor generated by P element imprecise excision (45,101); dumb2, a hypomorphic DopR/dDA1 allele (102); UAS-DAMB/CyO (provided by Kyung-An Han); UAS-dDA1 (50); UAS-DAMB RNAi (UAS-DAMB-IR) (Vienna Drosophila RNAi center, stock #v3391); RyR16, a mutant of the ryanodine receptor (63), UAS-dTrpA1 (59) (described in Result section), UAS-mCD8::GFP (103) and UAS-GFP-S65T (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center). Constructions of the TRH-GAL4, VGlut-GAL4 and UAS-VGlut::GFP transgenes used in this study are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods and in Supplementary Material, Figures S3 and S4.

PQ intoxication and survival score

Unless otherwise indicated, PQ treatment was performed on 7- to 10-day-old adult females, either by dietary ingestion or by direct application of the drug to decapitated flies. For dietary ingestion, ∼100 flies per condition were incubated at 25°C in 2-inch (5.2 cm) diameter Petri dishes (10 flies per dish) containing two layers of Whatman paper soaked with 600-µl PQ (methyl viologen, Sigma) diluted in 2% (wt/vol) sucrose or sucrose only for controls. To avoid dehydration, dishes were enclosed in a plastic box layered with moist paper. Survival was monitored after 24 or 48 h. Generally, 20 mm PQ was used in ingestion experiments, which yielded ∼40% survival after 24 h for wild-type flies (Fig. 1A).

For direct application, flies were anesthetized on ice for 10 min and their heads were cut off with 7-mm blade spring scissors (Fine Science tools). About 100 decapitated flies per condition were transferred to a 2-inch Petri dish (10 flies per dish) and allowed to recover for a few minutes until they stood on their legs. A 5-µl droplet of PQ diluted in Drosophila Ringer's solution (in mm: 130 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 Na2HPO4, 0.35 KH2PO4, pH 7.4 adjusted with 150 Na2HPO4) or Ringer's only for controls was applied for 5 s with a P10 Pipetman to the VNC at the anterior notum as described (47). The same droplet was successively used for 10 flies. Then, flies were incubated at 25°C in the same conditions as those intoxicated by ingestion. A concentration of 80 mm PQ was generally used that gave 30–40% survival with 7- to 10-day-old wild-type flies after 2 h (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Flies were considered as dead when they laid on the side or back and did not react to a light mechanical stimulus. Survival was monitored every 30 min, and graphs present survival at 2 h unless otherwise noted. A similar procedure was used to assay for DA toxicity.

DA receptor antagonists were purchased from Tocris and added to the PQ solution used for direct application at the following concentrations: SKF83959, 50 µm; SKF83566, 5 mm; eticlopride, 5 mm. To increase cAMP level in cells, 25 µm forskolin plus 100 µm 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) (both from Sigma–Aldrich) were similarly added to the PQ solution and controls received equivalent volumes of DMSO. For in vivo neuron activation, 30 decapitated Drosophila expressing dTrpA1 in neuronal subsets were intoxicated as usual at room temperature and then immediately incubated at 31°C for 2 h before fly survival was scored.

Survival rates were normalized to the mean value of internal controls, most often wild-type or UAS control strains. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey–Kramer or Student's t-test. Unless otherwise stated, errors bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM) of 9 or 10 independent determinations. Statistical significance in all figures: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, n.s. not significant.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted by the TrIzol (Invitrogen) method. Adult flies were anesthetized on ice and decapitated with a sterile scalpel. Twenty heads (or 5 thoraxes) were dissolved in 500 µl TriZol and kept at −80°C overnight. Remaining tissues were then crushed with a mini-Potter. The mixture was extracted with 100 μl chloroform and centrifuged at 2320g (5000 rpm) in an Eppendorf 5415 R microcentrifuge for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, mixed with 250 μl isopropanol, and stored for 30 min to 2 h at −20°C. After 15-min microcentrifugation at 2320g, the pellet was washed twice with 250 μl 75% (vol/vol) ethanol prepared with diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water followed by 4 min of microcentrifugation at 2320g. The dried pellet was suspended in 20 µl of RNAse-free water. One microliter of the solution was used to determine RNA concentration with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific).

Reverse transcription–PCR

For retrotranscription, 1 µg of total RNA was mixed with 0.5 µg of oligo(dT)15 (Promega) and 10 mm dNTP mix (Promega) in RNAse-free water. After heating at 65°C for 5 min, the tube was placed on ice and supplemented with 4 µl of 5× First-Strand Buffer (Invitrogen), 2 µl of 0.1 m DTT, and 1 µl of RNAsin (Promega). After 2 min pre-incubation at 42°C, 1 µl of SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase was added and the reaction mix (final volume: 20 µl) was incubated for 50 min at 42°C. The reaction was stopped by heating at 70°C for 15 min. PCR was performed as previously described (41) in a Techne TC-312 thermal cycler in 20 µl of final volume. The program included a cycle of 40 s of denaturation at 94°C, 40 s of annealing at 62°C and 40 s of elongation at 72°C, repeated 35 or 40 times. Alternatively, PCR was performed using PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara). In this case, the program included a cycle of 10 s of denaturation at 98°C, 10 s of annealing at 55°C and 30 s of elongation at 72°C, repeated 30 times only to allow comparison of transcript expression levels. Band density analysis of the PCR products was performed with the Fiji software, and data were normalized to the internal controls (either rp49 or actin). Results are mean ± SEM of 3–5 independent experiments. The following primers were used: for DAMB, sense: 5′ TTTGACTCCTCTGTCGCTCA, antisense: 5′ CAAAGAACGTAATGGAGGATG (amplicon: 232 bp); for rp49, sense: 5′ GACGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATC, antisense: 5′ AAACGCGGTTCTGCATGAG (amplicon: 126 bp); for Actin 5C, sense: 5′ CGACAACGGCTCTGGCATGT, antisense: 5′ TCCATTGTGCACCGCAAGTG (amplicon: 1094 bp).

Real-time PCR

For real-time PCR, RNA extracted from adult heads was cleaned from contaminant DNA prior to retrotranscription by treatment with RQ1 RNAse-free DNAse (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR was carried out in a MyiQ2 two-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) with the SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) in 96-well plates. Each well contained 2.5 µl of the retrotranscription product and 0.1 µm sense and antisense primers in 1× Syber Green Mix, in a final volume of 25 µl. The ribosomal gene rp49 was used as an internal control. The program was: 95°C denaturation for 10 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles (15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 55°C and 45 s at 60°C), and ended by 10-s ramping from 50 to 90°C to run a melting curve. The DAMB and rp49 primers were the same as those used for the RT-CPR experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Whole adult CNS was dissected at room temperature in Drosophila Ringer's solution and fixed for 2 h on ice in a watch glass in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS (130 mm NaCl, 7 mm Na2HPO4, 3 mm KH2PO4) before being transferred with Dumont #5 forceps to 24-well plates (5–10 brains per well). After three 20-min washes in 0.5 ml PBS plus 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (PBT), tissues were pre-incubated for 2 h in PBT + 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin as blocking solution, transferred again to 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 4°C with agitation in the presence of primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution (final volume: 100 µl). The primary antibodies used were: mouse monoclonal anti-TH (1:50; ImmunoStar), mouse anti-GFP (1:500; Invitrogen Molecular Probes), rabbit anti-serotonin (1:500; Sigma), rabbit anti-DAMB (1:100) (54) and rabbit anti-synaptotagmin (Syt-1) (1:100, generous gift of Hugo Bellen). After three 20-min washes in PBT, brains were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 0.5 ml of secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 555 anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes), or FITC anti-rabbit, TRITC anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted to 1:250. Tissues were washed three times again in PBT for 20 min and finally mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) or Mowiol 4–88 (Polysciences). Images were collected on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope and processed with ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop. The dopaminergic nerve-ending varicosities were quantified by measuring the respective area they covered in TH-immunostained whole VNCs as total pixel number using Adobe Photoshop.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation de France, Fédération pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau (FRC), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), ESPCI and CNRS to S.B. and NIH/NIMHHD 2G12MD007592 to K.A.H. The Association France-Parkinson, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) and Fondation Pierre-Gilles de Gennes provided post-doctoral salaries to T.Rie. Doctoral fellowships were provided by the Université Pierre-et-Marie Curie to M.C. and A.R.I., Université de la Méditerranée and FRM to H.C. and T.Riv.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Philippe Ascher, Daniel Cattaert, Baya Chérif-Zahar, Preeya Fozdar, Jay Hirsh and André Klarsfeld for helpful discussions and/or comments on the manuscript, Hugo Bellen for the kind gift of the anti-synaptotagmin antibody, and Marie LeBossé and Yu Yan for technical help in the early stages of this work.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reuter S., Gupta S.C., Chaturvedi M.M., Aggarwal B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsutsui H., Kinugawa S., Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–H2190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin M.T., Beal M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karbowski M., Neutzner A. Neurodegeneration as a consequence of failed mitochondrial maintenance. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou C., Huang Y., Przedborski S. Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease: a mechanism of pathogenic and therapeutic significance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:93–104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman J.N., Sanchez-Padilla J., Wokosin D., Kondapalli J., Ilijic E., Schumacker P.T., Surmeier D.J. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 2010;468:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature09536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schapira A.H.V., Gegg M. Mitochondrial contribution to Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011:159160. doi: 10.4061/2011/159160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang O. Role of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Exp. Neurobiol. 2013;22:11–17. doi: 10.5607/en.2013.22.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forno L.S. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996;55:259–272. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauer W., Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shulman J.M., De Jager P.L., Feany M.B. Parkinson's disease: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corti O., Lesage S., Brice A. What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson's disease. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91:1161–1218. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stokes A.H., Hastings T.G., Vrana K.E. Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of dopamine. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;55:659–665. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990315)55:6<659::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisaglia M., Greggio E., Beltramini M., Bubacco L. Dysfunction of dopamine homeostasis: clues in the hunt for novel Parkinson's disease therapies. FASEB J. 2013;27:2101–2110. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segura-Aguilar J., Paris I., Muñoz P., Ferrari E., Zecca L., Zucca F.A. Protective and toxic roles of dopamine in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 2014;129:898–915. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan C.S., Guzman J.N., Ilijic E., Mercer J.N., Rick C., Tkatch T., Meredith G.E., Surmeier D.J. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosharov E.V., Larsen K.E., Kanter E., Phillips K.A., Wilson K., Schmitz Y., Krantz D.E., Kobayashi K., Edwards R.H., Sulzer D. Interplay between cytosolic dopamine, calcium, and alpha-synuclein causes selective death of substantia nigra neurons. Neuron. 2009;62:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner C.M., Kamel F., Ross G.W., Hoppin J.A., Goldman S.M., Korell M., Marras C., Bhudhikanok G.S., Kasten M., Chade A.R., et al. Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson's disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:866–872. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang A., Costello S., Cockburn M., Zhang X., Bronstein J., Ritz B. Parkinson's disease risk from ambient exposure to pesticides. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011;26:547–555. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamel F. Epidemiology. Paths from pesticides to Parkinson's. Science. 2013;341:722–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1243619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pezzoli G., Cereda E. Exposure to pesticides or solvents and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80:2035–2041. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b3c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Przedborski S., Ischiropoulos H. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: weapons of neuronal destruction in models of Parkinson's disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:685–693. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramachandiran S., Hansen J.M., Jones D.P., Richardson J.R., Miller G.W. Divergent mechanisms of paraquat, MPP+, and rotenone toxicity: oxidation of thioredoxin and caspase-3 activation. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;95:163–171. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franco R., Li S., Rodriguez-Rocha H., Burns M., Panayiotidis M.I. Molecular mechanisms of pesticide-induced neurotoxicity: relevance to Parkinson's disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;188:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochemé H.M., Murphy M.P. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1786–1798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosamani R., Muralidhara Acute exposure of Drosophila melanogaster to paraquat causes oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 2013;83:25–40. doi: 10.1002/arch.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack A.L., Atienza J.G., Johnston L.C., Andersen J.K., Vu S., Di Monte D.A. Role of oxidative stress in paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell degeneration. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:1030–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren J.-P., Zhao Y.-W., Sun X.-J. Toxic influence of chronic oral administration of paraquat on nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in C57BL/6 mice. Chin. Med. J. 2009;122:2366–2371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somayajulu-Niţu M., Sandhu J.K., Cohen J., Sikorska M., Sridhar T.S., Matei A., Borowy-Borowski H., Pandey S. Paraquat induces oxidative stress, neuronal loss in substantia nigra region and Parkinsonism in adult rats: neuroprotection and amelioration of symptoms by water-soluble formulation of coenzyme Q10. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon J.R., Greenamyre J.T. Neurotoxic in vivo models of Parkinson's disease recent advances. Prog. Brain Res. 2010;184:17–33. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nisticò R., Mehdawy B., Piccirilli S., Mercuri N. Paraquat- and rotenone-induced models of Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011;24:313–322. doi: 10.1177/039463201102400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coulom H., Birman S. Chronic exposure to rotenone models sporadic Parkinson's disease in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10993–10998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2993-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhuri A., Bowling K., Funderburk C., Lawal H., Inamdar A., Wang Z., O'Donnell J.M. Interaction of genetic and environmental factors in a Drosophila Parkinsonism model. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2457–2467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4239-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayersdorfer F., Voigt A., Schneuwly S., Botella J.A. Dopamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila models of familial and sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;40:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosamani R., Ramesh S.R., Muralidhara Attenuation of rotenone-induced mitochondrial oxidative damage and neurotoxicty in Drosophila melanogaster supplemented with creatine. Neurochem. Res. 2010;35:1402–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0198-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawal H.O., Chang H.-Y., Terrell A.N., Brooks E.S., Pulido D., Simon A.F., Krantz D.E. The Drosophila vesicular monoamine transporter reduces pesticide-induced loss of dopaminergic neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;40:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam R., Yang L., Sah M., Kannan K., Anamani D., Vijayan C., Kwok J., Cantino M.E., Beal M.F., Fridell Y.-W.C. A neuroprotective role of the human uncoupling protein 2 (hUCP2) in a Drosophila Parkinson's disease model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;46:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang R.-D., Wiemerslage L., LaBreck C.J., Khan M., Kannan K., Wang X., Zhu X., Lee D., Fridell Y.-W.C. The neuroprotective effect of human uncoupling protein 2 (hUCP2) requires cAMP-dependent protein kinase in a toxin model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;69:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonilla E., Medina-Leendertz S., Villalobos V., Molero L., Bohórquez A. Paraquat-induced oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster: effects of melatonin, glutathione, serotonin, minocycline, lipoic acid and ascorbic acid. Neurochem. Res. 2006;31:1425–1432. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friggi-Grelin F., Iché M., Birman S. Tissue-specific developmental requirements of Drosophila tyrosine hydroxylase isoforms. Genesis. 2003;35:175–184. doi: 10.1002/gene.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riemensperger T., Isabel G., Coulom H., Neuser K., Seugnet L., Kume K., Iché-Torres M., Cassar M., Strauss R., Preat T., et al. Behavioral consequences of dopamine deficiency in the Drosophila central nervous system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:834–839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010930108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blenau W., Baumann A. Molecular and pharmacological properties of insect biogenic amine receptors: lessons from Drosophila melanogaster and Apis mellifera. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2001;48:13–38. doi: 10.1002/arch.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hearn M.G., Ren Y., McBride E.W., Reveillaud I., Beinborn M., Kopin A.S. A Drosophila dopamine 2-like receptor: Molecular characterization and identification of multiple alternatively spliced variants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14554–14559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202498299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebestky T., Chang J.-S.C., Dankert H., Zelnik L., Kim Y.-C., Han K.-A., Wolf F.W., Perona P., Anderson D.J. Two different forms of arousal in Drosophila are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1 receptor ortholog DopR via distinct neural circuits. Neuron. 2009;64:522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berry J.A., Cervantes-Sandoval I., Nicholas E.P., Davis R.L. Dopamine is required for learning and forgetting in Drosophila. Neuron. 2012;74:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ja W.W., Carvalho G.B., Mak E.M., la Rosa de N.N., Fang A.Y., Liong J.C., Brummel T., Benzer S. Prandiology of Drosophila and the CAFE assay. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8253–8256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702726104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yellman C., Tao H., He B., Hirsh J. Conserved and sexually dimorphic behavioral responses to biogenic amines in decapitated Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4131–4136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirsh J. Decapitated Drosophila: a novel system for the study of biogenic amines. Adv. Pharmacol. 1998;42:945–948. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60903-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torres G., Horowitz J.M. Activating properties of cocaine and cocaethylene in a behavioral preparation of Drosophila melanogaster. Synapse. 1998;29:148–161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<148::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andretic R., Kim Y.-C., Jones F.S., Han K.-A., Greenspan R.J. Drosophila D1 dopamine receptor mediates caffeine-induced arousal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20392–20397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806776105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friggi-Grelin F., Coulom H., Meller M., Gomez D., Hirsh J., Birman S. Targeted gene expression in Drosophila dopaminergic cells using regulatory sequences from tyrosine hydroxylase. J. Neurobiol. 2003;54:618–627. doi: 10.1002/neu.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neckameyer W.S., Weinstein J.S. Stress affects dopaminergic signaling pathways in Drosophila melanogaster. Stress. 2005;8:117–131. doi: 10.1080/10253890500147381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shukla A.K., Pragya P., Chaouhan H.S., Patel D.K., Abdin M.Z., Kar Chowdhuri D. A mutation in Drosophila methuselah resists paraquat induced Parkinson-like phenotypes. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:2419.e1–2419.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han K.A., Millar N.S., Grotewiel M.S., Davis R.L. DAMB, a novel dopamine receptor expressed specifically in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Neuron. 1996;16:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sombati S., Hoyle G. Glutamatergic central nervous transmission in locusts. J. Neurobiol. 1984;15:507–516. doi: 10.1002/neu.480150608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bicker G., Schäfer S., Ottersen O.P., Storm-Mathisen J. Glutamate-like immunoreactivity in identified neuronal populations of insect nervous systems. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2108–2122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-02108.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniels R.W., Gelfand M.V., Collins C.A., DiAntonio A. Visualizing glutamatergic cell bodies and synapses in Drosophila larval and adult CNS. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;508:131–152. doi: 10.1002/cne.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng G., Hannan F., Reale V., Hon Y.Y., Kousky C.T., Evans P.D., Hall L.M. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel dopamine receptor from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3925–3933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03925.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamada F.N., Rosenzweig M., Kang K., Pulver S.R., Ghezzi A., Jegla T.J., Garrity P.A. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X., Tang X., Li M., Marshall J., Mao Z. Regulation of neuroprotective activity of myocyte-enhancer factor 2 by cAMP-protein kinase A signaling pathway in neuronal survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16705–16713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silveira M.S., Linden R. Neuroprotection by cAMP: another brick in the wall. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;557:164–176. doi: 10.1007/0-387-30128-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang H., Wang H., Figueiredo-Pereira M.E. Regulating the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway via cAMP-signaling: neuroprotective potential. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013;67:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9628-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sullivan K.M., Scott K., Zuker C.S., Rubin G.M. The ryanodine receptor is essential for larval development in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5942–5947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110145997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McPherson P.S., Kim Y.K., Valdivia H., Knudson C.M., Takekura H., Franzini-Armstrong C., Coronado R., Campbell K.P. The brain ryanodine receptor: a caffeine-sensitive calcium release channel. Neuron. 1991;7:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90070-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kushnir A., Betzenhauser M.J., Marks A.R. Ryanodine receptor studies using genetically engineered mice. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1956–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Casas-Tinto S., Zhang Y., Sanchez-Garcia J., Gomez-Velazquez M., Rincon-Limas D.E., Fernandez-Funez P. The ER stress factor XBP1 s prevents amyloid-beta neurotoxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2144–2160. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phillips J.P., Campbell S.D., Michaud D., Charbonneau M., Hilliker A.J. Null mutation of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase in Drosophila confers hypersensitivity to paraquat and reduced longevity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:2761–2765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parkes T.L., Elia A.J., Dickinson D., Hilliker A.J., Phillips J.P., Boulianne G.L. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by overexpression of human SOD1 in motorneurons. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:171–174. doi: 10.1038/534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCormack A.L., Atienza J.G., Langston J.W., Di Monte D.A. Decreased susceptibility to oxidative stress underlies the resistance of specific dopaminergic cell populations to paraquat-induced degeneration. Neuroscience. 2006;141:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Magwere T., West M., Riyahi K., Murphy M.P., Smith R.A.J., Partridge L. The effects of exogenous antioxidants on lifespan and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006;127:356–370. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Legan S.K., Rebrin I., Mockett R.J., Radyuk S.N., Klichko V.I., Sohal R.S., Orr W.C. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase extends the life span of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:32492–32499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805832200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strub B.R., Parkes T.L., Mukai S.T., Bahadorani S., Coulthard A.B., Hall N., Phillips J.P., Hilliker A.J. Mutations of the withered (whd) gene in Drosophila melanogaster confer hypersensitivity to oxidative stress and are lesions of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT I) gene. Genome. 2008;51:409–420. doi: 10.1139/G08-023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Q., Niu Y., Zhang R., Guo H., Gao Y., Li Y., Liu R. The toxic influence of paraquat on hippocampus of mice: involvement of oxidative stress. NeuroToxicology. 2010;31:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rzezniczak T.Z., Douglas L.A., Watterson J.H., Merritt T.J.S. Paraquat administration in Drosophila for use in metabolic studies of oxidative stress. Anal. Biochem. 2011;419:345–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andretic R., Hirsh J. Circadian modulation of dopamine receptor responsiveness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1873–1878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marican C., Duportets L., Birman S., Jallon J.M. Female-specific regulation of cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis by dopamine in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:823–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Drechsel D.A., Patel M. Role of reactive oxygen species in the neurotoxicity of environmental agents implicated in Parkinson's disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:1873–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liou H.H., Chen R.C., Tsai Y.F., Chen W.P., Chang Y.C., Tsai M.C. Effects of paraquat on the substantia nigra of the Wistar rats: neurochemical, histological, and behavioral studies. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1996;137:34–41. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McCormack A.L., Thiruchelvam M., Manning-Bog A.B., Thiffault C., Langston J.W., Cory-Slechta D.A., Di Monte D.A. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;10:119–127. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peng J., Stevenson F.F., Doctrow S.R., Andersen J.K. Superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are neuroprotective against selective paraquat-mediated dopaminergic neuron death in the substantial nigra: implications for Parkinson disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29194–29198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morrow G., Samson M., Michaud S., Tanguay R.M. Overexpression of the small mitochondrial Hsp22 extends Drosophila life span and increases resistance to oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004;18:598–599. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0860fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bezprozvanny I. Calcium signaling and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pivovarova N.B., Andrews S.B. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial function and dysfunction in neurons. FEBS J. 2010;277:3622–3636. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nicholls D.G. Oxidative stress and energy crises in neuronal dysfunction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:53–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rival T., Soustelle L., Strambi C., Besson M.-T., Iché M., Birman S. Decreasing glutamate buffering capacity triggers oxidative stress and neuropil degeneration in the Drosophila brain. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Daniels R.W., Miller B.R., DiAntonio A. Increased vesicular glutamate transporter expression causes excitotoxic neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;41:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dolezelova E., Nothacker H.-P., Civelli O., Bryant P.J., Zurovec M. A Drosophila adenosine receptor activates cAMP and calcium signaling. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;37:318–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lin Y.J., Seroude L., Benzer S. Extended life-span and stress resistance in the Drosophila mutant methuselah. Science. 1998;282:943–946. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Song W., Ranjan R., Dawson-Scully K., Bronk P., Marin L., Seroude L., Lin Y.-J., Nie Z., Atwood H.L., Benzer S., et al. Presynaptic regulation of neurotransmission in Drosophila by the G protein-coupled receptor methuselah. Neuron. 2002;36:105–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00932-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shimizu K., Matsubara K., Ohtaki K., Fujimaru S., Saito O., Shiono H. Paraquat induces long-lasting dopamine overflow through the excitotoxic pathway in the striatum of freely moving rats. Brain Res. 2003;976:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pickering A.M., Staab T.A., Tower J., Sieburth D., Davies K.J.A. A conserved role for the 20S proteasome and Nrf2 transcription factor in oxidative stress adaptation in mammals, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:543–553. doi: 10.1242/jeb.074757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cyr M., Beaulieu J.-M., Laakso A., Sotnikova T.D., Yao W.-D., Bohn L.M., Gainetdinov R.R., Caron M.G. Sustained elevation of extracellular dopamine causes motor dysfunction and selective degeneration of striatal GABAergic neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11035–11040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831768100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cyr M., Sotnikova T.D., Gainetdinov R.R., Caron M.G. Dopamine enhances motor and neuropathological consequences of polyglutamine expanded huntingtin. FASEB J. 2006;20:2541–2543. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6533fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tang T.-S., Chen X., Liu J., Bezprozvanny I. Dopaminergic signaling and striatal neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:7899–7910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1396-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]