Abstract

Gastritis is a common but a serious disease with a potential risk of developing carcinoma. Helicobacter pylori infection is reported as the most common cause of gastritis, but other genetic and genomic factors exist, especially single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Association studies between SNPs and gastritis disease are important, but results on epistatic interactions from multiple SNPs are rarely found in previous genome-wide association (GWA) studies. In this study, we performed computational GWA case-control studies for gastritis in Korea Associated Resource (KARE) data. By transforming the resulting SNP epistasis network into a gene-gene epistasis network, we also identified potential gene-gene interaction factors that affect the susceptibility to gastritis.

Keywords: gastritis, genome-wide association study, KARE, mutual information, relevance network, single-nucleotide polymorphism

Introduction

Gastritis is a common disease in Korea. There is a report that 9.9% of Koreans have gastritis [1]. Gastritis is associated with the potential risk of developing gastric cancer or peptic ulcer disease [2]. A common cause of gastritis is Helicobacter pylori infection [3]. However, in addition to the cause, other genetic and genomic factors have been examined for gastritis. Human leukocyte antigen class II allele is an important risk factor for chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoma in Koreans [4]. Moreover, many studies have reported that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including rs1143627 in interleukin-1 beta (IL1B), rs4073 in interleukin 8 (IL8), rs4986790 in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and rs16260 in cadherin-1 (CDH1), are associated with susceptibility to gastric diseases, especially gastric cancer [5, 6, 7, 8].

The results from SNP studies show the importance of research for the association between SNP and disease, based on the association and functional relationship between gastritis and gastric carcinoma [9]. In other words, a casual SNP in one disease may be a genetic factor for another disease. However, previous studies only targeted the effect from each single variation; results have been rarely obtained for high-order genetic interactions in gastritis from genome-wide association (GWA) studies to date.

In this study, we performed a GWA case-control study for gastritis using SNP genotype data of the Korea Associated Resource (KARE) project [10]. Our study was focused on detecting significant epistatic SNP-SNP interactions and the resulting gene-gene interactions that are putative causal factors in gastritis. A validation and functional analysis of the result was performed on the obtained relevance gene-gene epistasis network.

Our network construction method is based on the previous relevance network approach [11]. To measure the strength of the association between a pair of SNPs and gastritis, we used the mutual information that has shown to be effective in detecting epistasis in case-control GWA studies [12, 13]. An efficient permutation scheme was adopted to extract significant interaction pairs, and we also approximated the p-values by exploiting the relationship between the mutual information value and the χ2 value [14]. We further transformed this SNP network into a relevant gene-gene epistasis network to validate the biological significance of our findings. A functional analysis was performed on the gene-gene network, and the topological properties of the network were also investigated.

Methods

Pre-processing for KARE data

The KARE genotype data we used in the study initially consisted of 352,228 SNPs and 8,842 samples after the screening by genotype calling and quality control performed [10]. We performed the following additional stages of pre-processing. First, we selected case-control samples based on the survey of the disease history of the patients, which was carried out in the KARE project. In the first stage, we collected 1,885 patients who self-reported that they had gastritis in the past as cases. We also found 4,117 individuals who self-reported that they had no history of having gastritis or any other diseases. Among those patients, we randomly selected 1,885 individuals as controls to avoid bias in the study.

After the selection of case-control patients, we filtered out SNPs that corresponded to the following conditions: minor allele frequency <0.01 in each group [15], pairwise linkage disequilibrium r2 > 0.8 [16], and SNPs in the X chromosome. PLINK [17] was used for the calculation of these values. The resulting dataset consisted of 185,426 SNPs and 3,770 samples for the case-control study.

Mutual information

We used mutual information measures to assess the strength of the association between a pair of SNPs and the disease status of gastritis. Mutual information has been widely used to measure dependence or independence between two random variables [11, 12, 18, 19]. It is a non-parametric measure and is able to detect both linear and non-linear associations [14]. This measure is based on Shannon's entropy, H(X) = Σx∈X - p(x)log(p(x)), which shows the uncertainty of the random variable X. Mutual information I(X;Y) between random variables X and Y is defined by the composition of entropy as follows:

| I(X;Y) = H(X) + H(Y) - H(X,Y). |

H(X), H(Y) denote entropies for the random variables X, Y, and H(X,Y) denotes the joint entropy of the two random variables as follows:

| H(X,Y)=Σx∈XΣy∈Y - p(x,y)log(p(x,y)). |

A high mutual information value indicates a strong association between two random variables. The measure can also be extended to assess the strength of association between a pair of SNPs and a phenotype. The extended version of mutual information is as follows:

| I(X1,X2;Y) = H(X1,X2) + H(Y) - H(X1,X2,Y), |

where X1 and X2 are random variables for two SNPs, and Y denotes random variables for the disease. In our recent work [12], we have shown that this measure could identify high-order epistatic interactions both with and without marginal effects by using simulation models, such as in Culverhouse et al.'s [20] and Velez et al.'s studies [21].

As the genotype and disease status are represented as discrete values, it is more convenient to consider the random variables as a partition of the combination of the genotypes and disease status. Then, the entropy of a random variable X can be represented in terms of the partition as follows:

where X = {A1, A2,…, An} is a partition on the set of samples S = {A1∪A2∪…∪An}, and no intersections exist between elements in the partition. The joint entropy of two random variables for the partition of S, X = {A1, A2,…, An} and Y = {B1, B2,…, Bm} is defined as follows:

The entropy also can be extended to the joint entropy of multiple random variables (e.g., 3 or 4 SNPs) naturally.

Extraction of statistically significant epistatic interactions

As mentioned above, mutual information is a non-parametric measure, and the distribution of values from the population is unknown; therefore, it is difficult to show the statistical significance of values calculated by this measure. Rather than doing the computationally too-expensive permutation tests for every pair of SNPs, which causes severe multiple testing issues when applied to GWA studies, we adopted the alternative permutation scheme proposed [11]. First, we replicated 30 permutations for disease status in case-control samples. For every possible pair of given SNPs, we calculated mutual information of SNPs with the permutated disease status labels and obtained the average value from 30 replications. θ denotes the maximum value of the averages. If a mutual information value between SNPs and the phenotype from real data is higher than θ, then we consider that the pair of SNPs shows a more significant association with gastritis than a random association.

To further assess the statistical significance of the identified SNP pairs, we approximated the p-values of the SNP pairs by exploiting the following relationship between χ2 value and mutual information [14]:

| χ2 ~ 2Nln2·I(X1,X2;Y), |

where N denotes the number of patients in the study.

Relevance network construction and assessment of significance

Network analysis is a powerful tool to understand biological systems. Given the significant epistatic interactions between SNP pairs and disease status detected by the permutation scheme, we constructed SNP-SNP epistatic interaction networks, where SNP represents the node and the significant interaction between SNP pairs represents the edge. However, it is difficult to assess the biological significance of the interaction networks directly because of the lack of interaction databases for SNPs.

To overcome this limitation, we directly mapped these networks into a gene-gene relevance network.

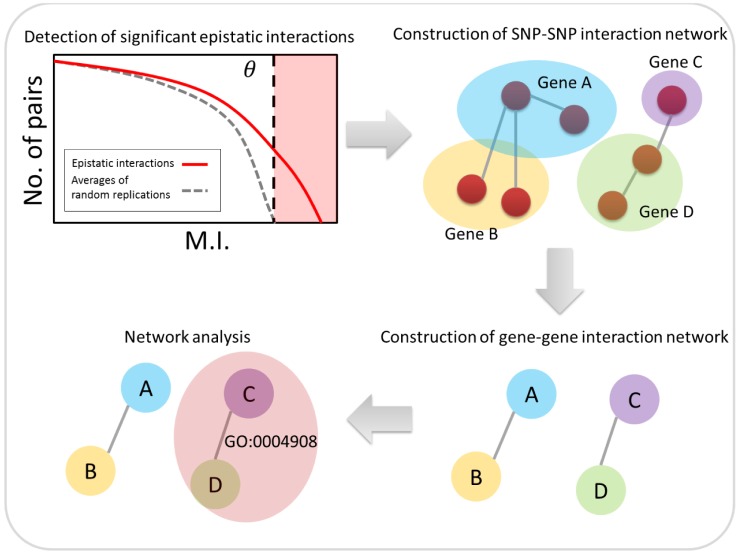

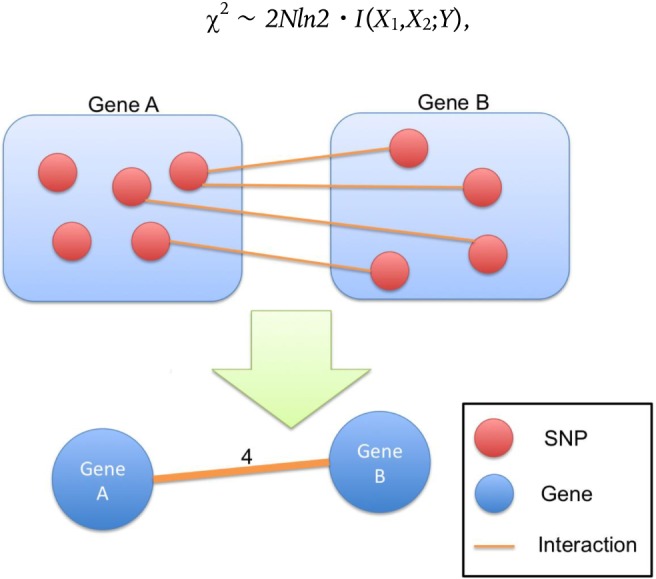

Fig. 1 represents a brief scheme of how to map the network. Suppose that some SNPs map directly to genes A and B, and there are at least two SNPs that have significant interactions for disease status. If one SNP maps to gene A and another SNP maps to gene B, then we consider that genes A and B have a unidirectional edge. The weight of the edge is defined by number of the interacting SNP pairs. For example, in Fig. 1, there are four SNP interactions between gene A and gene B. Thus, we consider that gene A and gene B have an edge, the weight of which is 4 in the gene-gene network. Finally, the top 5% edges having the largest edge weights are used in the biological validation and topological investigation.

Fig. 1.

Scheme for mapping the SNP-SNP interaction network onto the gene-gene epistasis network. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

We constructed a gene-gene network for each chromosome showing intra-chromosome interactions. We measured the network topologies of each network using Cytoscape [22] and also ran a gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for sets of genes in the network. We used DAVID [23] to validate the biological significance of the networks.

Fig. 2 illustrates the overall analysis scheme used in this study.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the network construction method. GO, gene ontology; M.I., mutual information; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Results

Statistically significant epistatic interactions in each chromosome

We ran the permutation method for each individual chromosome separately. As a result, we obtained SNP pairs that were non-randomly associated with the status of gastritis for the given patients.

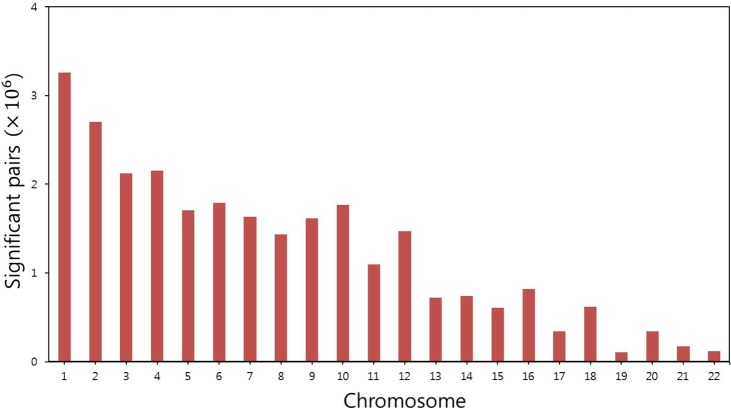

Fig. 3 shows the number of such SNP pairs for each chromosome. We found that there were approximately 2%-4% associated pairs among all possible pairs in the chromosomes.

Fig. 3.

Number of significant single-nucleotide polymorphism pairs for each chromosome.

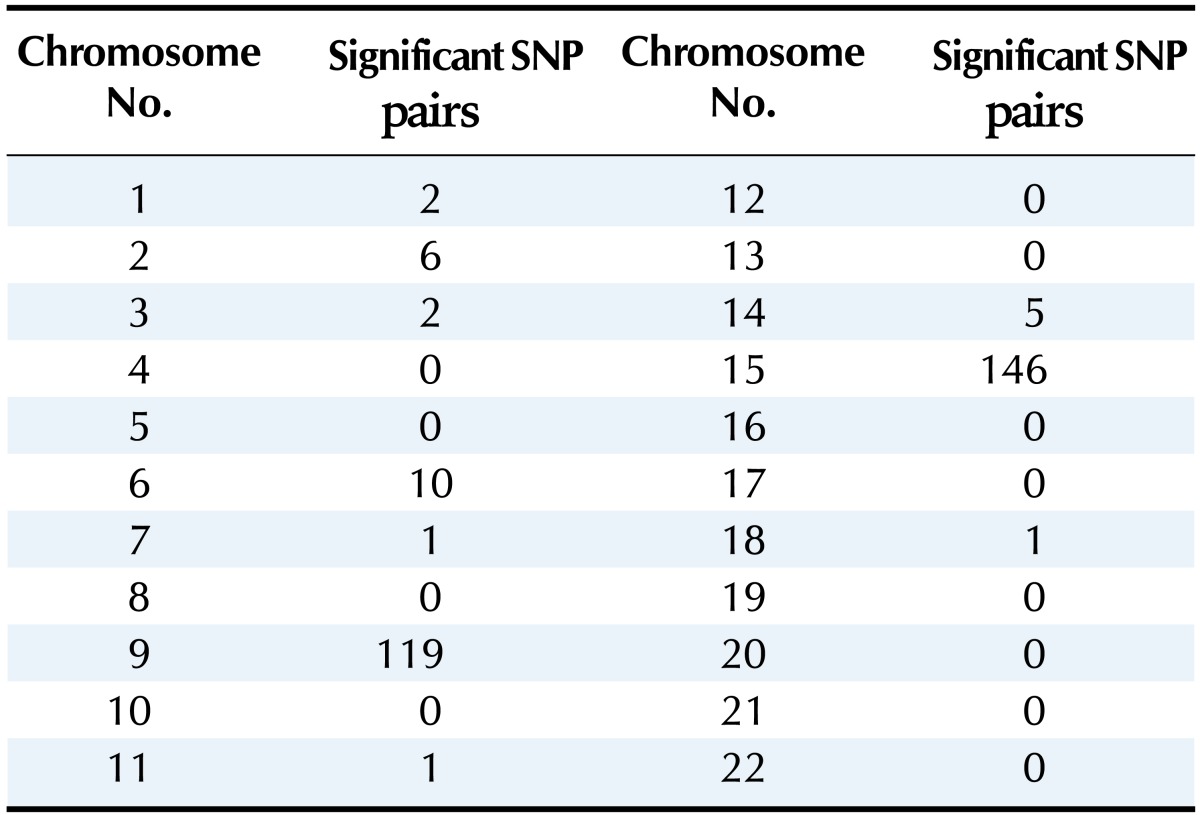

We then calculated the p-value for each SNP pair by using the approximation scheme [14] and under Bonferroni correction [24]. Table 1 shows the number of statistically significant SNP pairs within each chromosome. Significant SNP pairs and p-values are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In total, 293 SNP pairs showed statistical significance in the study. Chromosomes 9 and 15 had many significant pairs, but many of those pairs included SNPs with marginal effects (rs169730 in chromosome 9, rs493971 in chromosome 15). There were few significant SNP pairs within the chromosomes, and these pairs were not found in previous studies of gastric disease; therefore, further investigation of the pairs is needed to assess their biological significance.

Table 1.

Number of significant SNP pairs in each chromosome

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

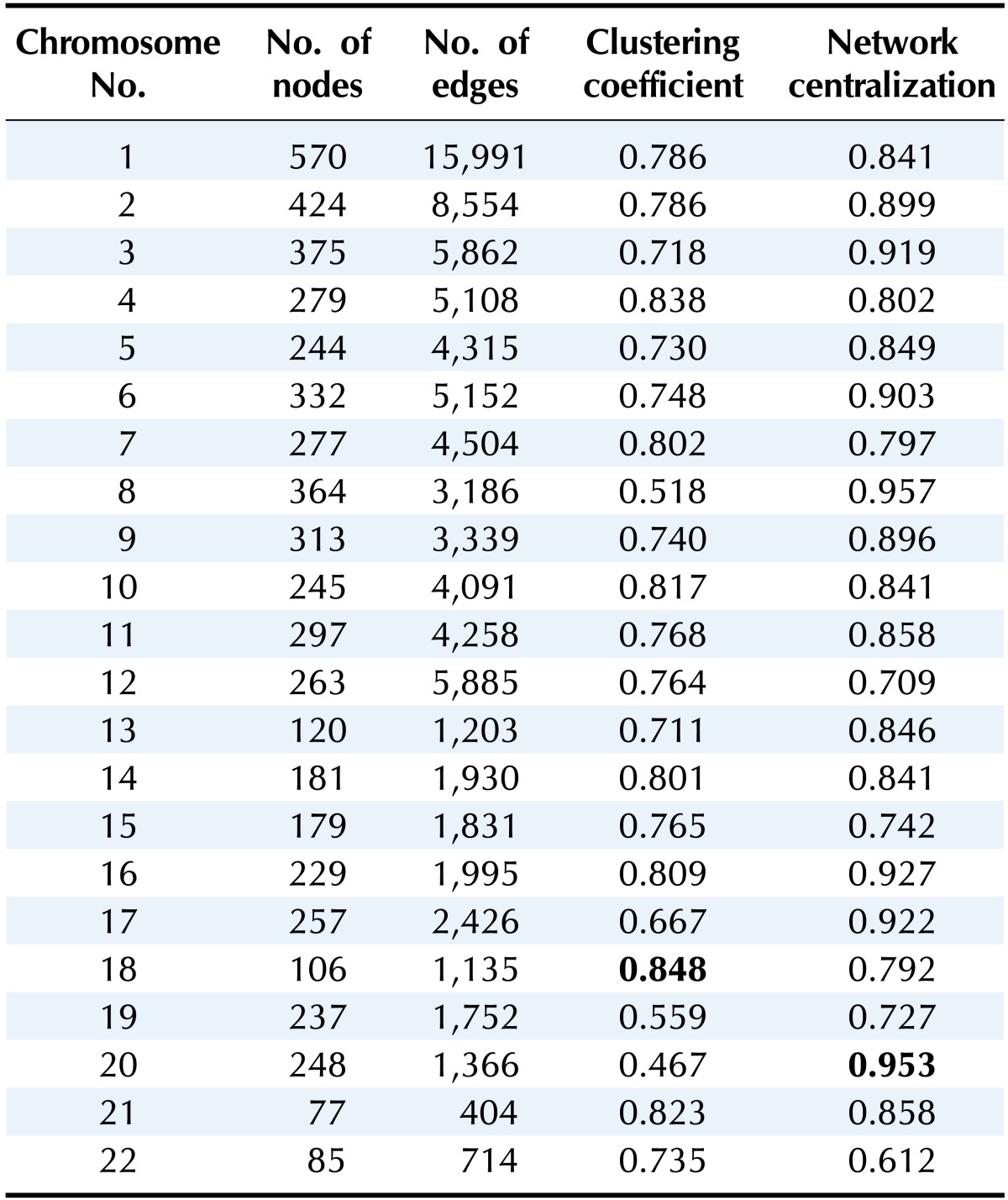

Network topologies

Table 2 summarizes the results of the network topology measures (number of nodes and edges, clustering coefficient, and network centralization) for the gene-gene interaction network for each chromosome. The table shows that all chromosomes showed similar properties: the number of edges is 10-30-fold higher than the number of nodes, and the measurements reveal high clustering coefficients and network centralization.

Table 2.

Network topologies for gene-gene interaction networks for each chromosome

Additionally, every network from each chromosome consisted of only one component.

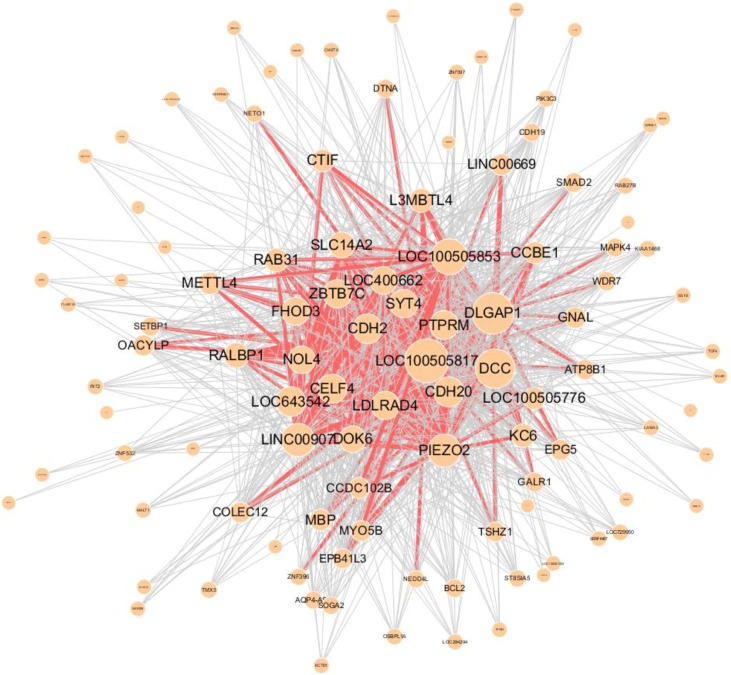

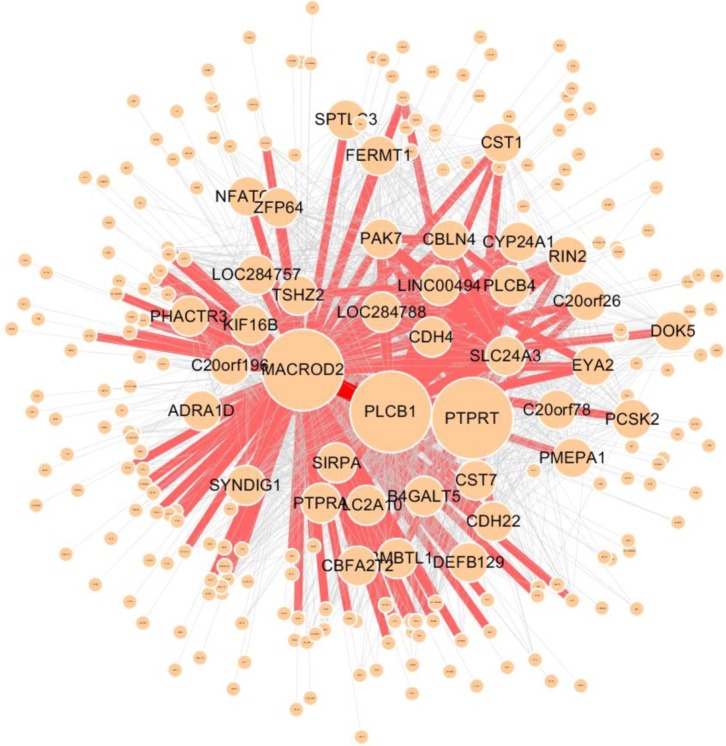

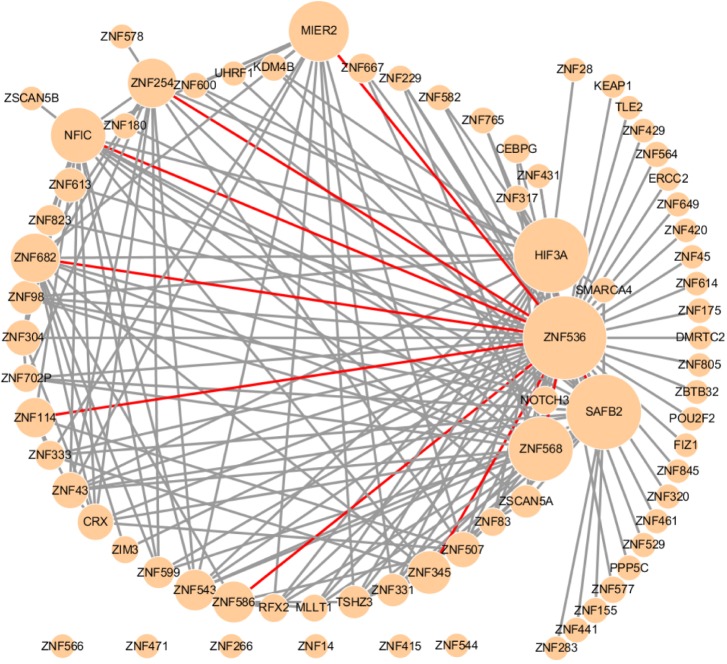

Figs. 4 and 5 present the structure of networks showing the highest values for the measures, especially the clustering coefficient and network centralization.

Fig. 4.

Graphical visualization of the gene-gene interaction network in chromosome 18, which shows the highest clustering coefficient (0.848). Red edges represents frequent SNPSNP interactions between two genes (>100). SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Fig. 5.

Graphical visualization of gene-gene interaction network in chromosome 20, which shows the highest network centralization (0.953). Red edges represent frequent SNPSNP interactions between two genes (>100). SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

In the real world, many biological networks show high average clustering coefficients [25]. The network in chromosome 18 showed the highest clustering coefficient, and we found some hub genes in the network that were reported to be associated with gastric disease. For example, Uchino et al. [26] reported frequent loss of heterozygosity at the deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) locus in gastric cancer.

Higher network centralization values show that hub genes highly affect the network [27]. In other words, if the hubs are removed, then the network may divide into several components. The network in chromosome 20 showed the highest value for the centralization measure. In the network receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase T (PTPRT), one of the hub genes was reported to be one of 15 genes in CpG islands showing significant differential methylation in gastric carcinoma [28].

From the results, we determined that there were many close gene-gene interactions derived from SNP-SNP interactions for gastritis and that if a gene had a high degree in the network, then this gene was connected to other genes with which it had frequent SNP-SNP interactions. We also found this tendency in most chromosomes.

Enrichment analysis

We ran an enrichment analysis of the gene-gene interaction network for GO using DAVID [23].

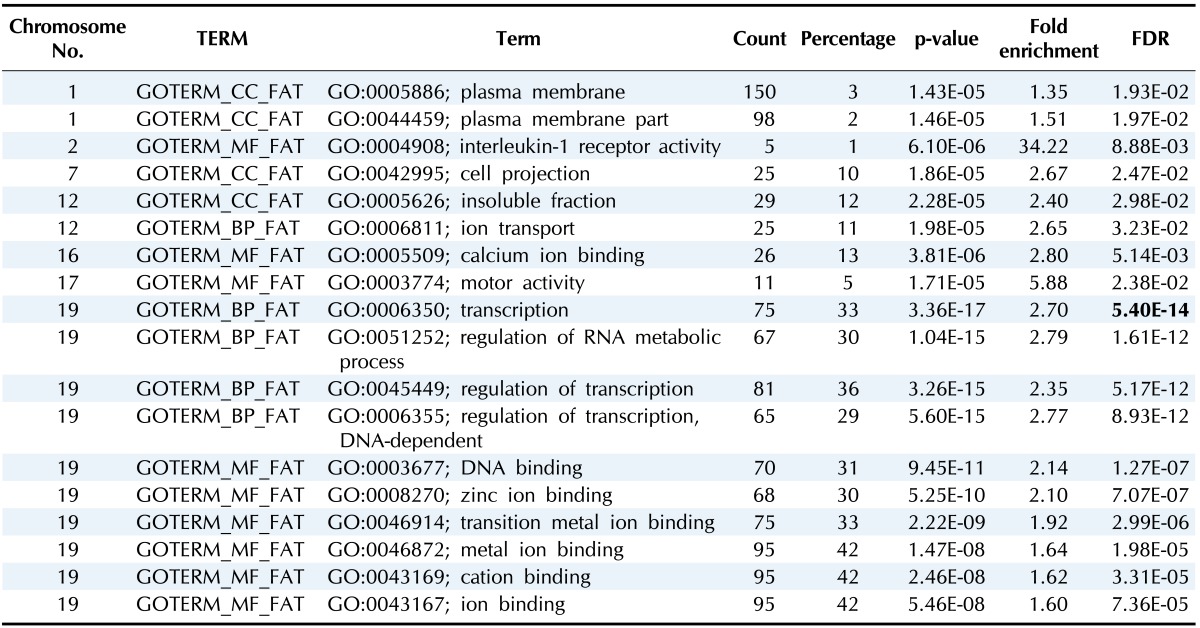

Table 3 summarizes the significantly enriched terms from DAVID. Every term that was annotated in the table was significant under a false discovery rate (FDR)-based correction (p < 0.05 after adjustment).

Table 3.

Significantly enriched GO terms for each chromosome

GO, gene ontology; FDR, false discovery rate.

Chromosome 19 had the most enriched terms among chromosomes, and these terms were related to regulation (biological process) and binding (molecular function).

Fig. 6 presents the internal structure of the sub-network for transcription (GO:0006350) in chromosome 19. This network has many zinc finger (ZNF) family genes. Taniuchi et al. [29] reported that zinc-binding protein-89 (ZBP-89), which is related to the ZNF gene family and is a Krüppel-type zinc finger protein, is overexpressed in gastric cancer patients.

Fig. 6.

Graphical visualization of the internal structure of the sub-network, which consists of genes related to transcription (GO:0006350). Red edges represent frequent SNP-SNP interactions between two genes (>100). GO, gene ontology; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

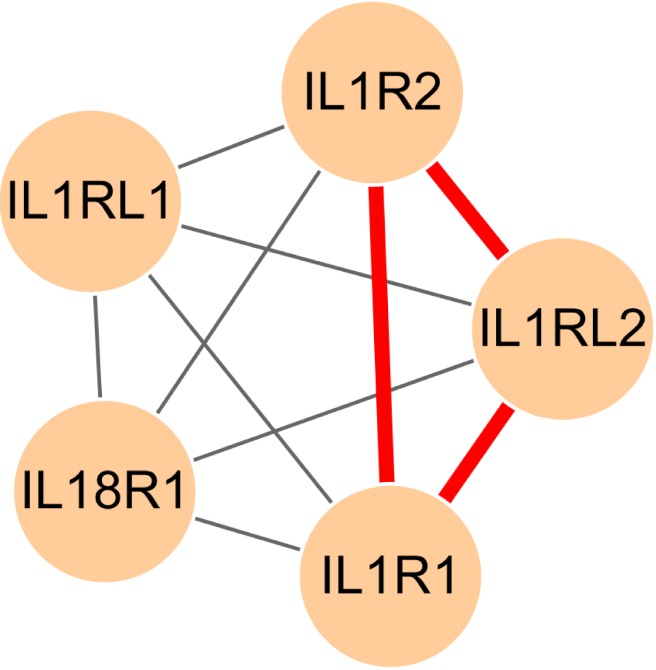

Additionally, interleukin-1 receptor activity (GO:0004908) was significantly enriched in chromosome 2.

Fig. 7 presents the internal structure of the gene-gene relevance network for the GO terms. As mentioned in the introduction, interleukin family genes and intra-SNPs were reported [5, 7]; therefore, these genes and SNPs are associated with the susceptibility to gastric cancer. Genes that were enriched in the GO terms were not connected in the relevance gene-gene network; still, these genes had few SNP-SNP interactions with every other gene (weight equal or less than 11).

Fig. 7.

Graphical visualization of the internal structure of the sub-network, which consists of genes related to interleukin-1 receptor activity (GO:0004908). Red edges represent frequent SNP-SNP interactions between two genes (>10). GO, gene ontology; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

We also ran an enrichment analysis for the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway [30], but no terms were significant under FDR-based adjustment.

Discussion

In this study, we applied a simple but powerful method to detect epistatic interactions that distinguish gastritis patients from controls. We found several putative SNP-SNP interactions using the mutual information measure. Additionally, relevance gene-gene interaction networks that are derived from epistatic interactions show high clustering coefficients and centralization.

We found that some sub-networks in the recovered network had biological significance for gastric disease from the GO enrichment analysis. However, we did not find these results to have direct associations with gastritis, because gastritis has been less extensively studied than other gastric diseases, such as gastric cancer or ulcer. We expect that future studies on gastritis will be necessary to validate the results from our study.

In this study, only intra-chromosome interactions were considered. We expect that if we extend the method to inter-chromosomal analyses, this could increase the chances of finding novel sub-networks that are enriched in pathways for gastritis. However, this extension will impose a computational burden and increase the type I error; therefore, the development of a more flexible framework is needed to resolve this issue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Republic of Korea (4845-301, 4851-302, 4851-307), and a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant, funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2010-0028631).

Supplementary material

Supplementary data including one table can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-12-216-s001.pdf.

List of significant SNP pairs and their p-values

References

- 1.Park KS. How much amount of socioeconomic loss is caused by digestive diseases? Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:297–299. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.58.6.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corvalan AH, Carrasco G, Saavedra K. The genetic and epigenetic bases of gastritis. In: Mozsik G, editor. Current Topics in Gastritis. Rijeka: InTech; 2013. pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HW, Hahm KB, Lee JS, Ju YS, Lee KM, Lee KW. Association of the human leukocyte antigen class II alleles with chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoma in Koreans. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuzhalin A. The role of interleukin DNA polymorphisms in gastric cancer. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:1128–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zendehdel K, Bahmanyar S, McCarthy S, Nyren O, Andersson B, Ye W. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase genes GSTP1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:2031–2038. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue H, Liu J, Lin B, Wang Z, Sun J, Huang G. A meta-analysis of interleukin-8 -251 promoter polymorphism associated with gastric cancer risk. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Oliveira JG, Silva AE. Polymorphisms of the TLR2 and TLR4 genes are associated with risk of gastric cancer in a Brazilian population. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1235–1242. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho YS, Go MJ, Kim YJ, Heo JY, Oh JH, Ban HJ, et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nat Genet. 2009;41:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ng.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butte AJ, Kohane IS. Mutual information relevance networks: functional genomic clustering using pairwise entropy measurements. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2000:418–429. doi: 10.1142/9789814447331_0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leem S, Jeong HH, Lee J, Wee K, Sohn KA. Fast detection of high-order epistatic interactions in genome-wide association studies using information theoretic measure. Comput Biol Chem. 2014;50:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu T, Sinnott-Armstrong NA, Kiralis JW, Andrew AS, Karagas MR, Moore JH. Characterizing genetic interactions in human disease association studies using statistical epistasis networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goebel B, Dawy Z, Hagenauer J, Mueller JC. An approximation to the distribution of finite sample size mutual information estimates; 2005 IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2005 May 16-20; Seoul. Seoul: ICC 2005; 2005. pp. 1102–1106. Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong KW, Kim SS, Kim Y. Genome-wide association study of orthostatic hypotension and supine-standing blood pressure changes in two korean populations. Genomics Inform. 2013;11:129–134. doi: 10.5808/GI.2013.11.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim JE, Oh B. Allelic frequencies of 20 visible phenotype variants in the korean population. Genomics Inform. 2013;11:93–96. doi: 10.5808/GI.2013.11.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang KC, Wang X. Gene regulatory network reconstruction using conditional mutual information. EURASIP J Bioinform Syst Biol. 2008:253894. doi: 10.1155/2008/253894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolin AA, Nemenman I, Basso K, Wiggins C, Stolovitzky G, Dalla Favera R, et al. ARACNE: an algorithm for the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks in a mammalian cellular context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culverhouse R, Suarez BK, Lin J, Reich T. A perspective on epistasis: limits of models displaying no main effect. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:461–471. doi: 10.1086/338759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velez DR, White BC, Motsinger AA, Bush WS, Ritchie MD, Williams SM, et al. A balanced accuracy function for epistasis modeling in imbalanced datasets using multifactor dimensionality reduction. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:306–315. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cline MS, Smoot M, Cerami E, Kuchinsky A, Landys N, Workman C, et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2366–2382. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavlopoulos GA, Secrier M, Moschopoulos CN, Soldatos TG, Kossida S, Aerts J, et al. Using graph theory to analyze biological networks. BioData Min. 2011;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1756-0381-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchino S, Tsuda H, Noguchi M, Yokota J, Terada M, Saito T, et al. Frequent loss of heterozygosity at the DCC locus in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3099–3102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun J, Zhao Z. A comparative study of cancer proteins in the human protein-protein interaction network. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(Suppl 3):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-S3-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Zhang J, Gao Y, Pei L, Zhou J, Gu L, et al. Large-scale characterization of DNA methylation changes in human gastric carcinomas with and without metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4598–4612. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taniuchi T, Mortensen ER, Ferguson A, Greenson J, Merchant JL. Overexpression of ZBP-89, a zinc finger DNA binding protein, in gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:154–160. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D199–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of significant SNP pairs and their p-values