Abstract

Background and Purpose

4-Phenylquinolin-2(1H)-one (4-PQ) derivatives can induce cancer cell apoptosis. Additional new 4-PQ analogs were investigated as more effective, less toxic antitumour agents.

Experimental Approach

Forty-five 6,7,8-substituted 4-substituted benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives were synthesized. Antiproliferative activities were evaluated using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliun bromide assay and structure–activity relationship correlations were established. Compounds 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e were also evaluated against the National Cancer Institute-60 human cancer cell line panel. Hoechst 33258 and Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assays were used to detect apoptosis, while inhibition of microtubule polymerization was assayed by fluorescence microscopy. Effects on the cell cycle were assessed by flow cytometry and on apoptosis-related proteins (active caspase-3, -8 and -9, procaspase-3, -8, -9, PARP, Bid, Bcl-xL and Bcl-2) by Western blotting.

Key Results

Nine 6,7,8-substituted 4-substituted benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (7e, 8e, 9b, 9c, 9e, 10c, 10e, 11c and 11e) displayed high potency against HL-60, Hep3B, H460, and COLO 205 cancer cells (IC50 < 1 μM) without affecting Detroit 551 normal human cells (IC50 > 50 μM). Particularly, compound 11e exhibited nanomolar potency against COLO 205 cancer cells. Mechanistic studies indicated that compound 11e disrupted microtubule assembly and induced G2/M arrest, polyploidy and apoptosis via the intrinsic and extrinsic signalling pathways. Activation of JNK could play a role in TRAIL-induced COLO 205 apoptosis.

Conclusion and Implications

New quinolone derivatives were identified as potential pro-apoptotic agents. Compound 11e could be a promising lead compound for future antitumour agent development.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| Enzymesa | Catalytic receptorsb |

| Aurora A kinase | DR4, death receptor 4 |

| Aurora B kinase | DR5, death receptor 5 |

| CDK1, cyclin dependent kinase 1 | Fas |

| ERK1/2 | TNFR1, TNF receptor 1 |

| JNK | TRAF2, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 |

| p38 | Tubulin |

| RIP, receptor interacting protein (kinase) |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Bid |

| Colchicine |

| TNFα |

| TRAIL |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 a,bAlexander et al., 2013a,b).

Introduction

Cancer is presently a worldwide health problem and the leading cause of death in the United States and other developed countries (Rastogi et al., 2004). Cancer is a formidable disease caused by disordered cell growth and invasion of tissues and organs. While various therapies and strategies have been developed to treat cancer, most of them have limitations. Thus, new anticancer drugs are continually needed. The main challenge facing clinical cancer therapy is to find a specific approach that kills malignant cells with no or few adverse effects on normal tissues and considerable attempts have been made to develop innovative, safe and effective methods to defeat cancer. While scientists have discovered many agents with cytostatic action against cancer cells (Liu et al., 2007; Folger et al., 2011), increasing understanding of the biological processes involved in cancer cell survival has led to the design and discovery of better targeted, novel therapeutic anticancer drugs. For several chemotherapeutic agents, a direct correlation has been found between antitumour efficacy and ability to induce apoptosis (Kaufmann and Earnshaw, 2000). Thus, approaches aimed at promoting apoptosis in cancer cells have gained importance in cancer research (Fesik, 2005; Fischer and Schulze-Osthoff, 2005).

Heterobicycles are indispensable structural units in compounds with a broad range of biological activities. Among various nitrogen-containing fused heterocyclic skeletons, quinoline and quinolone structures are important components prevalent in a vast array of biological systems. Compounds with a quinoline nucleus exhibit various pharmacological properties, including antioxidant (Chung and Woo, 2001; Zhang et al., 2013), anti-inflammatory (Baba et al., 1996; Mukherjee and Pal, 2013), antibacterial (Cheng et al., 2013), anti-human immunodeficiency virus (Freeman et al., 2004; Hopkins et al., 2004), antimalarial (Cornut et al., 2013; Pandey et al., 2013), antituberculosis (Lilienkampf et al., 2009), anti-Alzheimer's disease (Fiorito et al., 2013), anticancer (Wang et al., 2011; Abonia et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2012) activities. Accordingly, Solomon and Lee described quinoline-containing subunits as ‘privileged structures’ for drug development (Solomon and Lee, 2011). 2-Quinolone [quinolin-2(1H)-one], also called 1-aza coumarin or carbostyril, and 4-quinolone are structural isomers. The 2-quinolone skeleton is a fertile source of biologically active compounds, including a wide spectrum of alkaloids investigated for antitumour activity (Ito et al., 2004; He et al., 2005; Nakashima et al., 2012). In our previous investigation, 6,7-methylenedioxy-4-substituted phenylquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (4-phenylquinolin-2(1H)-ones; 4-PQs) were identified as novel apoptosis-inducing agents (Figure 1) (Chen et al., 2013b). Recently, Arya and Agarwal reported that 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives, prepared efficiently through microwave irradiation, showed strong photo-antiproliferative activity (Arya and Agarwal, 2007). Thus, we have directed our focus onto 4-PQ analogues as inducers of apoptosis. In our current study, we targeted the 2-quinolone structure as a basic scaffold of new derivatives with different substituents.

Figure 1.

The structures of some anticancer agents and the general structure of the target compounds (7a–e ∼ 15a–e).

Purine-based compounds such as olomoucine and roscovitine (Figure 1), which contain other heterobicyclic ring systems, are known ATP-binding site competitive inhibitors of cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) and are useful cell proliferation inhibitors in the treatment of cancer (Jorda et al., 2011). Structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies on CDK inhibitors demonstrated that a small hydrophobic group such as a non-polar benzyl group at the O6- or N6-position of the heterobicycle maximized CDK inhibition (Gibson et al., 2002; Zatloukal et al., 2013). In addition, numerous CDK inhibitor-related compounds that contain benzyl or aryl methyl groups on different core scaffolds, such as pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines (Paruch et al., 2007), quinazolin-4-amines (Mott et al., 2009), pyrimidine (Coombs et al., 2013) and aminopurine (Doležal et al., 2006) (Figure 1), have been studied. Furthermore, a series of 6-(benzyloxy)-2-(aryldiazenyl)-9H-purine derivatives were reported to act as prodrugs of O6-benzylguanine (O6-BG; Figure 1), which selectively targets O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) in hypoxic tumour cells (Zhu et al., 2013). The AGT protein plays a critical role in DNA repair, which can be exploited in chemotherapeutic treatment of neoplastic cells (Dolan and Pegg, 1997; Daniels et al., 2000). Alkylation of AGT with the benzyl group of O6-BG results in complete depletion of the alkyltransferase protein. Consequently, numerous O6-BG analogs have been developed as AGT inhibitors (Chae et al., 1995; Terashima and Kohda, 1998). Ruiz et al. (2008) reported that a family of quinolinone compounds acted as novel non-nucleosidic AGT inhibitors. These quinolinones could reach the critical catalytic residue Cys145 buried deep within the binding groove, occupy the catalytic cleft of human DNA repair AGT protein and act as substrate mimics of the O6-guanine moiety.

Furthermore, the activity of biologically proven anticancer pharmacophores can be enhanced by introducing appropriate substitutions on the chemical scaffolds. In medicinal chemistry, shortening or lengthening chain length is a useful tactic to improve the affinity of target binding. Some reports have demonstrated that the pro-apoptotic (anti-tumour) activity of certain compounds was dramatically improved by slightly changing the length and spacing of lateral branches, such as benzyl and other alkyl-aromatic side chains, on core skeletons (Al-Obaid et al., 2009; Font et al., 2011). Such exploration and utilization of chemical diversity relative to pharmacological space is an ongoing drug discovery strategy, referred to as privileged-substructure-based diversity-oriented synthesis (Oh and Park, 2011). Based on this strategy, as well as the structures shown in Figure 1, we proposed addition of a substituted benzyl (C ring) side chain linked at the O4-position of 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one (2-quinolone scaffold) as a possible strategy for discovering new leads with pro-apoptotic bioactivity. The flexibility of the benzyl moiety might provide better antitumour activity compared with our earlier 4-PQ derivatives (Figure 1). Therefore, we designed a series of 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one analogues 7a–e ∼ 15a–e, with the general structures of target compounds depicted in Figure 1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of 2-quinolone analogues bearing an O4-benzyl moiety against cancer. The goal of the current study was to discover more effective and less toxic antitumour agents and contribute to the SAR profile of 2-quinolones with anti-proliferative activity and pro-apoptotic activities in cancer cells.

Methods

Materials and physical measurements

All solvents and reagents were obtained commercially and used without further purification. The progress of all reactions was monitored by TLC on 2 × 6 cm pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 plates of thickness 0.25 mm (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The chromatograms were visualized under UV at 254–366 nm. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (Merck KGaA, particle size 0.063–0.200 mm). Melting points (mp) were determined with a Yanaco MP-500D melting point apparatus (Yanaco New Science Inc., Kyoto, Japan) and are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded on Shimadzu IR-Prestige-21 spectrophotometers (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) as KBr pellets. The one-dimensional NMR (1H and 13C) spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance DPX-200 FT-NMR spectrometer (Bruker Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) at room temperature. The two-dimensional NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance DPX-400 FT-NMR spectrometer (Bruker Corp.) and chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm, δ). The following abbreviations are used: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; dd, double doublet and m, multiplet. Mass spectra were performed at the Instrument Center of National Science Council at National Chung Hsing University (Taichung City, Taiwan) using a Finnigan ThermoQuest MAT 95 XL (EI-MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

General procedure for the synthesis of 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (5a–i)

4-Hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 5a–i were prepared by ‘one-pot’ cyclization in polyphosphoric acid (PPA). A mixture of the appropriate substituted aniline 1a–i (1 equiv) and diethylmalonate (2) (1.2 equiv) was heated with PPA (five to six times by weight) at 130°C for 2–6 h (TLC monitoring). Then, the mixture was cooled and diluted with water. A gum solidified upon standing overnight and the precipitate was filtered, washed with water and air-dried to provide 5a–i with sufficient purity for the next reaction. Physical and spectroscopic data for 5a are given in the succeeding text; the data for the remaining compounds are provided as Supporting Information.

4-Hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one (5a) (Mohamed, 1991; Nadaraj et al., 2006; Arya and Agarwal, 2007; Park et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008)

Compound 5a (3.48 g, 21.59 mmol) was obtained from aniline (1a) (3.82 g, 41.01 mmol) and diethylmalonate (2) (7.88 g, 49.20 mmol); yield: 53%; light-yellow solid; mp: 276–278°C; IR (KBr) ν (cm−1): 1660 (C = O); 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 5.77 (s, 1H, H–3), 7.12 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H–6), 7.26 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H–8), 7.47 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H–7), 7.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H–5), 11.28 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 98.56, 115.48, 115.63, 121.61, 123.11, 131.33, 139.55, 163.05, 164.18; MS (EI, 70 eV) m/z: 161.1[M]+; HRMS (EI) m/z: calculated for C9H7NO2: 161.0477; found: 161.0472.

General procedure for the synthesis of 6,7,8-substituted 4-substituted benyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (7a–e, 8a–e, 9a–e, 10a–e, 11a–e, 12a–e, 13a–e, 14a–e, 15a–e)

A mixture of 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 5a–i (1 equiv) and K2CO3 (2 equiv) in DMF (10–20 mL) was heated at 90°C for 1–2 h. The appropriate benzyl chloride or bromide (6a–e, 1–1.4 equiv) was added and the mixture was heated at 80–90°C for 1–6 h. Reaction completion was confirmed by TLC monitoring. The mixture was poured into ice water (200 mL) and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration and then washed with water. The residue was treated with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and purified by recrystallization. If no solid was formed after the addition of ice water, then the reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 before evaporation of solvent in vacuo. The residue was isolated by column chromatography (silica gel, EtOAc as eluate) and then recrystallized to give the corresponding pure products, 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 7a–e, 8a–e, 9a–e, 10a–e, 11a–e, 12a–e, 13a–e, 14a–e and 15a–e. Physical and spectroscopic data for 11e are given as examples; the data for the remaining compounds are provided as Supporting Information.

4-(3′,5′-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-6-methoxyquinolin-2(1H)-one (11e)

Compound 11e (0.70 g, 2.05 mmol) was obtained from 5e (1.12 g, 5.86 mmol) and 3,5-dimethoxybenzyl bromide (1.48 g, 6.40 mmol); yield: 35%; white crystal; mp: 217–219°C; IR (KBr) ν (cm−1): 1674 (C = O); 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 3.74 (s, 6H, 3′, 5′–OCH3), 3.76 (s, 3H, 6–OCH3), 5.20 (s, 2H, –O–CH2–), 5.94 (s, 1H, H–3), 6.47 (dd, J = 2.2,2.2 Hz, 1H, H–4′), 6.66 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H, H–2′, H–6′), 7.14–7.26 (m, 3H, H–5,7,8), 11.32 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 55.63 (2C), 55.78, 70.05, 98.71, 100.04, 104.17, 105.62 (2C), 115.50, 117.18, 120.50, 133.55, 138.76, 154.43, 161.07 (2C), 161.89, 163.23; MS (EI, 70 eV) m/z: 341.0 [M]+; HRMS (EI) m/z: calculated for C19H19NO5: 341.1263; found: 341.1257.

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliun bromide (MTT) assay for antiproliferative activity

Human tumour cell lines (HTCLs) of the cancer screening panel were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO®, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), penicillin (100 U·mL−1)/streptomycin (100 μg·mL−1) (GIBCO, Life Technologies) and 1% l-glutamine (GIBCO, Life Technologies) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Human hepatoma Hep 3B and normal skin Detroit 551 cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO, Life Technologies), penicillin (100 U·mL−1)/streptomycin (100 μg·mL−1) (GIBCO, Life Technologies) and 1% l-glutamine (GIBCO, Life Technologies) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Logarithmically growing cancer cells were used for all experiments. The HTCLs were treated with vehicle or test compounds for 48 h. Cell growth rate was determined by MTT reduction assay (Mosmann, 1983). After 48 h treatment, cell growth rate was measured on an elisa reader at a wavelength of 570 nm and the IC50 values of test compounds were calculated.

In vitro National Cancer Institute (NCI)-60 HTCL panel

In vitro cytotoxic activities were evaluated through the Developmental Therapeutic Program (DTP) of the NCI (Shoemaker, 2006). For more information on the anticancer screening protocol, please see: http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html.

Cell morphology and Hoechst 33258 staining

COLO 205 cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and then incubated with 50 nM of compound 11e for 12 to 48 h. Cells were directly examined and photographed under a contrast-phase microscope. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (bis-benzimide; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to detect chromatin condensation or nuclear fragmentation, features of apoptosis. After 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, 11e-treated cells were stained with 5 μg·mL−1 Hoechst 33258 for 10 min. After washing twice with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 10 min at 25°C. Fluorescence of the soluble DNA (apoptotic) fragments was measured in a Leica DMIL Inverted Microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 365 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm.

Apoptosis studies

Determination of apoptotic cells by fluorescent staining was carried out as described previously (van Engeland et al., 1998; Zhuang et al., 2013). The Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was obtained from Strong Biotech Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan). The COLO 205 cells (2 × 105 cells·per well) were fluorescently labelled for detection of apoptotic and necrotic cells by adding 100 μL of binding buffer, 2 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 2 μL of propidium iodide (PI) to each sample. Samples were mixed gently and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Binding buffer (300 μL) was added to each sample immediately before flow cytometric analysis. A minimum of 10 000 cells within the gated region was analysed.

Flow cytometric analysis for cell cycle

Compound 11e (final concentration 50 nM) was added to COLO 205 cells for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. Cells were fixed in 70% EtOH overnight, washed twice and resuspended in PBS containing 20 μg·mL−1 PI, 0.2 mg·mL−1 RNase A and 0.1% Triton X-100 in the dark. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, cell cycle distribution was analysed using ModFit LT Software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA) in a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Molecular modelling

The crystal structure of microtubules in complex with N-deacetyl-N-(2-mercaptoacetyl)-colchicine (DAMA-colchicine) was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB entry 1SA0: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do) (Ravelli et al., 2004). Docking studies were performed for proposed 11e in the colchicine-binding site of tubulin. The AutoDock Vina (The Scripps Research Institute, Molecular Graphics Lab., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to perform docking calculations (Trott and Olson, 2010). The final results were prepared with PyMOL (v. 1.3) (Schrödinger LLC., Shanghai Office, Shanghai, China) in Windows 7. After removing the ligand and solvent molecules, hydrogen atoms were added to each amino acid atom. The three-dimensional structure of compound were obtained from ChemBioDraw ultra 12.0 (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) followed by MM2 energy minimization. Docking was carried out by AutoDock Vina in the colchicine-binding pocket. Grid map in AutoDock 4.0 was used to define the interaction of protein and ligand in the binding pocket. For compound binding into the colchicine-binding site, a grid box size of 25 × 25 × 25 points in x, y and z directions was built and the grid centre was located in x = 116.909, y = 89.688 and z = 7.904.

Localization of microtubules

After treatment, cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, blocked with 2% BSA, stained with anti-tubulin monoclonal antibody, and then with FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. PI was used to stain the nuclei. Cells were visualized using a Leica TCS SP2 Spectral Confocal System (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Mitochondrial membrane potential analysis

Cells were plated (6 well plates) at 1.0 × 106 cells·per well and treated with 50 nM 11e for 6–24 h. Mitochondrial membranes were stained with 0.5 mL JC-1 working solution (BD MitoScreen Kit; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) added to each sample. Samples were incubated for 10–15 min at 37°C in the dark. Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using the BD FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Western blot assay

The treated cells (1 × 107 cells·10 mL−1 in 10 cm dish) were collected and washed with PBS. After centrifugation, cells were lysed in a lysis buffer. The lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 min. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were then determined using the Bradford assay. After adding a 5 × sample loading buffer containing 625 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 6.8, 500 mM dithiothreitol, 10% SDS, 0.06% bromophenol blue and 50% glycerol, protein samples were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoreactivity was detected using the Western blot chemiluminescence reagent system (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with anova followed by Tukey's test. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.001 was indicative of a significant difference.

Results

Chemistry

The synthetic procedures for the new 4-substituted benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones (7a–e ∼ 15a–e) are illustrated in Scheme 5. A general synthetic approach to the key intermediate 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one is the Knorr quinoline synthesis, which involves cyclization and dehydration of a transient β-ketoanilide, formed by condensation of a β-keto ester and aniline at relatively high temperature. More specific synthetic approaches include cyclization of N-acetylanthranilic acid derivatives (Buckle et al., 1975), condensation of malonates/malonic acid with anilines using ZnCl2 and POCl3 (Zhang et al., 2008; Priya et al., 2010), Ph2O (Ahvale et al., 2008) and cyclization of malonodianilides with PPA (Cai et al., 1996; Park et al., 2007; Moradi-e-Rufchahi, 2010), CH3SO3H/P2O5 (Kappe et al., 1988) and p-toluenesulfonic acid (Nadaraj et al., 2006). In our study, 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (5a–i) were synthesized by treatment of a substituted aniline (1a–i) with diethylmalonate (2) in one flask (Mohamed, 1991; Arya and Agarwal, 2007), followed by cyclization of the formed monoanilide (3a–i) or malondianilide (4a–i) precursors in the presence of PPA. The target 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 7a–e, 8a–e, 9a–e, 10a–e, 11a–e, 12a–e, 13a–e, 14a–e and 15a–e were synthesized by reaction of the intermediate 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 5a–i with various benzyl halide 6a–e in the presence of K2CO3 and DMF (Guo et al., 2009; Deng et al., 2010). All synthetic products were characterized by IR, 1H and 13C NMR and mass spectroscopy.

Figure 5.

Compound 11e induced time-dependent apoptosis in COLO 205 cells. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. (A) Compound 11e induced morphological changes in COLO 205 cells. (B) Fluorescent images of Hoechst staining showing 11e-induced cell death. The black arrowhead indicates an apoptotic nucleus and the white arrowheads indicate multinucleate cells. (C) Apoptosis induced by compound 11e was confirmed using annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry. The fraction of annexin V-positive COLO 205 cells was 5.5% prior to treatment and 7.6%, 12.7%, 20.9% and 21.8% after treatment with 11e for 12, 24, 36 and 48 h respectively. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Figure 15.

Scheme

Reagents and conditions: (A) 130°C with PPA. (B) K2CO3/DMF, 80–90°C.

The 2-quinolones have a minor tautomeric structure (2-hydroxyquinoline) because of protonation of the carbonyl oxygen (Lewis et al., 1991). Deprotonation of the 2-quinolone would cause ring resonance and electron shifting within the N-1, O-2, C-3 and O-4 positions of the 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (Figure 2A) (Pirrung and Blume, 1999). Consequently, earlier reports have indicated that 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones could be alkylated at the 1-NH, 2-OH, 4-OH or 3-CH position (Park and Lee, 2004; Ahmed et al., 2010; 2011). Therefore, we confirmed the structures of our synthesized compounds using NMR spectroscopic analyses. The 1H NMR spectrum of 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives 7a–e ∼ 15a–e featured a singlet for O-linked C(9)-H2 methylene protons between 5.13 and 5.27 ppm, a singlet for a C(3)-H proton between 5.80 and 6.09 ppm and a broad singlet for an exchangeable NH group between 10.47 and 11.54 ppm. The chemical shifts for the benzylic CH2 were consistent with O-alkylation rather than N-alkylation (Park and Lee, 2004). The 13C shifts for O-alkylated compounds are typically downfield (higher ppm value; 52.7–68.4) compared with N-alkylated compounds (lower ppm value; 28.6–45.0) (LaPlante et al., 2013). The 13C NMR spectra of 7a–e ∼ 15a–e included an O-linked methylene carbon between 65.74 and 70.74 ppm, which again indicated O-alkylation. Furthermore, regioselective alkylation at the 4-OH position was confirmed by two-dimensional NMR study via heteronuclear multiple-quantum correlation and heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) spectroscopy experiments that disclose the relationship between 1H and 13C coupling. In the case of compound 11e, as shown in Figure 2B, the 4-O-linkage was supported by observation of 3J-HMBC correlations between C(9)-H methylene protons (δH 5.20) on the 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy moiety with the carbon at C(4) position (δc 161.89) of the 2-quinolone core, which shows a further correlation with the C(5)-H proton (δH 7.14–7.26, overlapped). In other words, O4-alkylation was determined through the observation of H9/C4 and H5/C4 cross-peaks. These data proved that 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy moiety is attached to the 4-O-position of the 2-quinolone core structure. Furthermore, the IR spectra of 7a–e ∼ 15a–e possessed a characteristic absorption band for an amido C = O group (1633–1674 cm–1).

Figure 2.

Alkylation of 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones. (A) Tautomerism of 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives. (B) Key HMBC correlations (blue arrows) of 11e indicated alkylation at the 4-OH position.

Biological evaluation and SAR analysis

All newly synthesized target compounds (7a–e, 8a–e, 9a–e, 10a–e, 11a–e, 12a–e, 13a–e, 14a–e and 15a–e) were assayed for growth inhibitory activity against Detroit 551 cells (human normal skin fibroblast) and four cancer cell lines – HL-60 (leukaemia), Hep 3B (hepatoma), H460 (non-small-cell lung carcinoma) and COLO 205 (colorectal adenocarcinoma). Cells were treated with compounds for 48 h and cell proliferation was determined by MTT assay. The antiproliferative activity of each compound was presented as the concentration of compound that achieved 50% inhibition (IC50) of cancer cell growth. The results are summarized in Table 2012. Collectively, the present series of novel 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives exhibited a range of potencies against the four tested tumour cell lines. Among them, compounds 7e, 8e, 9b, 9c, 9e, 10c, 10e, 11c and 11e displayed high potency against HL-60, Hep3B, H460 and COLO 205 cells, with IC50 value less than 1 μM (Table 2012). Notably, 11e displayed the most prominent growth inhibitory activities against these four cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 14 to 40 nM. Moreover, none of the active compounds showed cytotoxicity (IC50 > 50 μM) towards Detroit 551 cells. These results suggested that this new series of 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives could effectively suppress tumour growth without causing toxicity to normal somatic cells.

Table 1.

Antiproliferative effects of compounds 7a–e ∼ 15a–e

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R | IC50 (μM)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL-60b | Hep 3Bb | H460b | COLO205b | Detroit 551b | |||||

| 7a | H | H | H | H | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 7b | H | H | H | 2′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 7c | H | H | H | 3′-OCH3 | 16.4 | >50 | >50 | 7.5 | >50 |

| 7d | H | H | H | 4′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 7e | H | H | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.42 | >50 |

| 8a | F | H | H | H | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 8b | F | H | H | 2′-OCH3 | 8.7 | >50 | >50 | 7.3 | >50 |

| 8c | F | H | H | 3′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 50 | >50 |

| 8d | F | H | H | 4′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 8e | F | H | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.39 | >50 |

| 9a | Cl | H | H | H | 4.5 | >50 | >50 | 9.8 | >50 |

| 9b | Cl | H | H | 2′-OCH3 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.41 | >50 |

| 9c | Cl | H | H | 3′-OCH3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.35 | >50 |

| 9d | Cl | H | H | 4′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 9e | Cl | H | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 0.0295 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.054 | >50 |

| 10a | CH3 | H | H | H | – | >50 | >50 | 8.2 | – |

| 10b | CH3 | H | H | 2′-OCH3 | – | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.0 | – |

| 10c | CH3 | H | H | 3′-OCH3 | – | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.36 | – |

| 10d | CH3 | H | H | 4′-OCH3 | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 10e | CH3 | H | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | – | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.06 | – |

| 11a | OCH3 | H | H | H | 8.5 | 27.0 | 51.7 | 8.8 | >50 |

| 11b | OCH3 | H | H | 2′-OCH3 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 3.3 | 5.0 | >50 |

| 11c | OCH3 | H | H | 3′-OCH3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.21 | >50 |

| 11d | OCH3 | H | H | 4′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 11e | OCH3 | H | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.04 | 0.028 | >50 |

| 12a | H | OCH3 | H | H | – | 9.55 | 17.3 | 14.2 | – |

| 12b | H | OCH3 | H | 2′-OCH3 | – | 4.02 | 7.1 | 6.4 | – |

| 12c | H | OCH3 | H | 3′-OCH3 | – | 3.23 | >50 | 8.2 | – |

| 12d | H | OCH3 | H | 4′-OCH3 | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 12e | H | OCH3 | H | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | – | 2.11 | 3.96 | 4.9 | – |

| 13a | H | H | OCH3 | H | >50 | >50 | >50 | 34.1 | >50 |

| 13b | H | H | OCH3 | 2′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 13c | H | H | OCH3 | 3′-OCH3 | 20.0 | 39.9 | 32.3 | 22.6 | >50 |

| 13d | H | H | OCH3 | 4′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 13e | H | H | OCH3 | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 | >50 |

| 14a | H | H | Cl | H | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 14b | H | H | Cl | 2′-OCH3 | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 14c | H | H | Cl | 3′-OCH3 | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 14d | H | H | Cl | 4′-OCH3 | – | >50 | >50 | >50 | – |

| 14e | H | H | Cl | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | – | 3.64 | 19.4 | 9.7 | – |

| 15a | H | H | CH3 | H | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 15b | H | H | CH3 | 2′-OCH3 | 20.0 | >50 | >50 | 41.5 | >50 |

| 15c | H | H | CH3 | 3′-OCH3 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 15d | H | H | CH3 | 4′-OCH3 | 10.0 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 15e | H | H | CH3 | 3′, 5′-(OCH3)2 | 0.72 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.6 | >50 |

| Etoposide | 5.48 | – | 1.0 | – | – | ||||

Human tumour cells were treated with different concentrations of samples for 48 h. Data are presented as IC50 (μM, the concentration of 50% proliferation-inhibitory effect).

Cell lines include leukaemia (HL-60), liver carcinoma (Hep3B), lung carcinoma (H460), colon carcinoma (COLO205) and normal skin fibroblasts (Detroit 551).

Based on the biological data obtained so far, SAR correlations were determined. Firstly, we evaluated the effects of methoxy substitution of the C-4 benzyloxy ring (C ring) on the cytotoxic activity. Generally, compounds with 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy side chain (7e–15e) showed the highest potency in their respective series (7–15). Among them, compounds 7e, 8e, 9e, 10e and 11e exhibited significant activity against Hep 3B, H460 and COLO 205 cancer cell lines (IC50 < 1 μM). These results indicated 3′,5′-dimethoxy-benzyloxy substitution is preferred relative to other benzyl substitution. Compounds 9b, 9c, 10b, 10c, 11b, 11c with a 2′- or 3′-methoxybenzyloxy side chain demonstrated moderate activity (IC50 0.2–5.0 μM), whereas compounds bearing side chains of benzyloxy or 4′-methoxybenzyloxy were inactive (IC50 > 50 μM) or exhibited only marginal activity (IC50 4.5–10 μM).

Next, we explored the SAR of the 2-quinolone A ring. Compounds with a substituted benzyloxy moiety at C-4 and various functional groups at C-6, -7 and -8 were studied and different anticancer effects were found. Regarding the C-6 substitution, compound 8e (6-fluoro), 9e (6-chloro), 10e (6-methyl) and 11e (6-methoxy) were more potent than 7e (no substitution). Moreover, compound 11e (IC50 0.014–0.04 μM) displayed the strongest growth inhibitory activity among the C-6 substituted compounds, suggesting that the C-6 methoxy group might play a pivotal role. Moving the methoxy group from C-6 to C-7 (12e, IC50 2.11–4.9 μM) or C-8 (13e, IC50 2.2–3.8 μM) dramatically decreased inhibitory activity. Activity also decreased when the C-8 methoxy of 13e was replaced with chlorine (14e), while activity was retained when the methoxy was replaced with methyl (15e). Thus, in this series of 4-benzyloxy-2-quinolones, optimal antiproliferative effects were found with a 6-methoxy group on the 2-quinolone ring.

In the present work, the earlier findings can be summarized in the following two SAR conclusions:

The in vitro anticancer activity of the substituted benzyloxy moiety (C ring) on the 4-position of 2-quinolone derivatives can be ranked in the following order of decreasing activity: 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy (7e–15e) > 3′-methoxybenzyloxy (7c–15c) ≧ 2′-methoxybenzyloxy (7b–15b) > benzyloxy (7a–15a) ≧ 4′-methoxybenzyloxy (7d–15d).

C-6 substituents on the 2-quinolone (A ring) resulted in better activity compared with C-7 and C-8 substituent. The following rank order of in vitro anticancer activity was found relative to the identity of the C-6 substituent: 6-methoxy > 6-chloro ≧ 6-methyl > 6-fluoro ≧ no substitution.

Anticancer drug screen panel of compound 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e against NCI-60 human cancer cell lines

We selected four potent compounds 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e and submitted them for screening against the NCI-60 HTCL panel assay through the US NCI DTP (Boyd and Paull, 1995; Shoemaker, 2006). The cell lines used in this assay represent nine tumour subpanels, leukaemia, melanoma and cancers of lung, colon, brain (CNS), ovary, kidney, prostate and breast. Initially, the compounds were added at a single dose (10 μM) and the culture was incubated for 48 h. End-point determinations were made with a sulforhodamine B assay. Results for each compound are given in Table 2010, with a negative value in the cell growth percentage indicating an antiproliferative effect against that cell line. Compound 9b displayed positive cytotoxic effects towards 11 out of 60 cell lines, and the positive cytotoxic proportions of 9c, 9e and 11e were 10/59, 18/60 and 26/57. Our prominent compound 11e exhibited inhibitory effects ranging from –59% to −0.80%. At the primary single high dose 10 μM (10−5 M), 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e showed greatest effects against colon carcinoma COLO 205 with cell growth percentage of −55, −57, −64 and −59 respectively. The melanoma MDA-MB-435 cell line was also sensitive to these compounds (growth percentages −46%, −43%, −43% and −41% respectively).

Table 2.

Growth percentages of selected compounds in the NCI in vitro 60-cell Drug Screen Program

| Panel/Cell line | Compounds/Growth percentage (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9b | 9c | 9e | 11e | |

| Leukaemia | ||||

| CCRF-CEM | 18.56 | 11.98 | 15.94 | −26.21b |

| HL-60(TB) | 9.64 | −9.34 | 7.37 | −32.61 |

| K-562 | 15.80 | 17.65 | 11.80 | 3.56 |

| MOLT-4 | 39.79 | 38.04 | 42.35 | 4.78 |

| RPMI-8226 | 19.77 | 17.87 | 15.90 | −6.67 |

| SR | 14.68 | 5.97 | 7.02 | −4.86 |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | ||||

| A549/ATCC | 29.44 | 21.67 | −22.24 | 7.15 |

| EKVX | 50.93 | 41.72 | 52.28 | – |

| HOP-62 | −18.38 | −22.55 | −27.19 | 24.70 |

| HOP-92 | 19.45 | 46.83 | 43.66 | 28.92 |

| NCI-H226 | 42.44 | 48.35 | 8.57 | 54.52 |

| NCI-H23 | 32.69 | 33.31 | 3.47 | −47.65 |

| NCI-H322M | 36.63 | 35.35 | 39.53 | 21.59 |

| NCI-H460 | 10.03 | 5.68 | 2.71 | 3.87 |

| NCI-H522 | 18.21 | 22.30 | −0.77 | −29.70 |

| Colon cancer | ||||

| COLO 205 | −55.40 | −57.40 | −64.41 | −59.50 |

| HCC-2998 | 23.46 | 27.86 | −12.73 | −32.77 |

| HCT-116 | 25.11 | 28.76 | 3.95 | 0.12 |

| HCT-15 | 24.78 | 19.69 | 17.60 | 7.24 |

| HT-29 | 7.13 | 2.57 | 0.32 | −27.36 |

| KM12 | 30.65 | 22.39 | 10.66 | 1.77 |

| SW-620 | 12.10 | 21.07 | 20.17 | 10.28 |

| CNS cancer | ||||

| SF-268 | 42.91 | 42.47 | 27.59 | 8.61 |

| SF-295 | 6.76 | 9.92 | −2.30 | −3.44 |

| SF-539 | 5.03 | −2.10 | −35.52 | −28.70 |

| SNB-19 | 28.95 | 30.82 | 19.73 | 48.02 |

| SNB-75 | −22.87 | −16.82 | −42.27 | – |

| U251 | 16.38 | 18.14 | −21.80 | 5.44 |

| Melanoma | ||||

| LOX IMVI | 14.48 | 17.90 | 2.15 | −6.75 |

| MALME-3M | 45.00 | 31.84 | 32.02 | 55.33 |

| M14 | 13.96 | 19.46 | 8.30 | −50.76 |

| MDA-MB-435 | −46.28 | −43.14 | −43.16 | −41.44 |

| SK-MEL-2 | 23.93 | 5.30 | 10.59 | −14.08 |

| SK-MEL-28 | −12.04 | 4.07 | −8.81 | 7.02 |

| SK-MEL-5 | −25.75 | −32.70 | 0.36 | −27.48 |

| UACC-257 | 24.32 | 21.96 | 19.86 | 34.86 |

| UACC-62 | −19.98 | 4.59 | 5.49 | −48.21 |

| Ovarian cancer | ||||

| IGROV1 | 45.21 | 39.68 | 46.14 | – |

| OVCAR-3 | 4.64 | 6.22 | −59.96 | −32.89 |

| OVCAR-4 | 34.25 | 42.73 | 29.48 | 40.39 |

| OVCAR-5 | 48.30 | 36.30 | 32.38 | 18.06 |

| OVCAR-8 | 33.86 | 24.06 | 6.15 | 9.94 |

| NCI/ADR-RES | 19.48 | 20.52 | 3.42 | −14.04 |

| SK-OV-3 | −17.68 | −27.16 | −27.00 | −0.80 |

| Renal cancer | ||||

| 786-0 | 33.73 | 39.62 | 3.94 | −2.61 |

| A498 | 21.88 | 16.02 | −2.40 | −8.21 |

| ACHN | 44.36 | 43.14 | 23.77 | 19.79 |

| CAKI-1 | 31.23 | 30.29 | 27.34 | 9.52 |

| RXF 393 | −14.00 | – | −25.73 | −11.48 |

| SN12C | 27.70 | 32.18 | 16.82 | 2.52 |

| TK-10 | 50.99 | 41.50 | −2.79 | 18.32 |

| UO-31 | 38.23 | 34.68 | 28.46 | 30.52 |

| Prostate cancer | ||||

| PC-3 | 21.26 | 23.95 | 27.74 | 20.50 |

| DU-145 | 16.06 | 14.85 | 20.65 | 1.31 |

| Breast cancer | ||||

| MCF7 | −5.90 | 1.34 | −35.96 | 13.94 |

| MDA-MB-231/ATCC | 29.63 | 40.04 | 5.25 | −2.71 |

| HS 578T | 9.12 | 21.68 | 21.06 | 31.90 |

| BT-549 | 42.21 | 48.16 | 30.87 | −19.04 |

| T-47D | −19.71 | −16.85 | 21.81 | 50.59 |

| MDA-MB-468 | 24.05 | −25.33 | −23.96 | −4.24 |

| Mean growth | 17.02 | 16.59 | 5.26 | 0.19 |

| Range of growth | −55.40 to 50.99 | −57.40 to 48.35 | −64.41 to 52.28 | −59.50 to 55.33 |

| The most sensitive cell line | COLO 205 (Colon cancer) | COLO 205 (Colon cancer) | COLO 205 (Colon cancer) | COLO 205 (Colon cancer) |

| Positive cytostatic effectc | 47/60 | 49/59 | 41/60 | 28/57 |

| Positive cytotoxic effectd | 11/60 | 10/59 | 18/60 | 26/57 |

aData obtained from NCI in vitro 60-cell screen programme at 10 μM. bNegative values represent compound proved lethal to the cancer cell line (cell death). cRatio between number of cell lines with percentage growth from 0 to 50 and total number of cell lines. dRatio between number of cell lines with percentage growth of <0 and total number of cell lines. The bold values indicate significant cytotoxicity toward cancer cell lines.

At the second evaluation stage, the selected compounds were evaluated at five different concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM) against the same NCI-60 HTCL panel. The outcomes were represented by three calculated response parameters (GI50, TGI and LC50) for each cell line through growth percentage inhibition curves (Holbeck, 2004; Holbeck et al., 2010). The GI50 value (growth inhibitory activity) corresponds to the concentration of compound causing 50% decrease in net cell growth, the TGI value (cytostatic activity) is the concentration of compound resulting in total growth inhibition (100% growth inhibition) and LC50 value (cytotoxic activity) is the lethal dose of compound causing net 50% death of initial cells. The calculated results are presented as log concentration (given in the Supporting Information), as shown in Table 2011. The NCI data revealed broad-spectrum sensitivity profiles for 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e towards all nine cancer subpanels with GI50 values less than 1 μM, and less than 0.01 μM (log GI50 < −8.0) against some cell lines for 9e and 11e. The anticancer effects of these compounds were comparable with those of fluorouracil (5-FU), which is widely used clinically for treating cancer (Longley et al., 2003). These screening results were in good agreement with the single dose results, showing broad anticancer spectra for 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e. Notably, compound 11e exhibited GI50 values ranging from 0.01 to 8.08 μM in 51 of the 56 cell lines, with GI50 values below 0.01 μM in five cell lines (leukaemia K-562 and SR, non-small-cell lung cancer NCI-H522, colon cancer COLO 205, melanoma MDA-MB-435).

Table 3.

In vitro antitumour activity (GI50 in μM), toxicity (LC50 in μM) and TGI data of selected compounds 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e

| Panel/Cell line | Compoundsa | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9b | 9c | 9e | 11e | 5-FUb | |||||||||||

| GI50 | TGI | LC50 | GI50 | TGI | LC50 | GI50 | TGI | LC50 | GI50 | TGI | LC50 | GI50 | TGI | LC50 | |

| Leukaemia | |||||||||||||||

| CCRF-CEM | 0.39 | 19.50 | >100 | 0.31 | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 10.00 | >100 | >100 |

| HL-60(TB) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 2.51 | >100 | >100 |

| K-562 | 0.08 | 11.60 | 92.50 | 0.03 | – | >100 | <0.01 | 1.67 | >100 | <0.01 | >100 | >100 | 3.98 | >100 | >100 |

| MOLT-4 | 0.51 | 32.50 | >100 | 0.33 | >100 | >100 | 0.05 | >100 | >100 | 0.07 | >100 | >100 | 0.32 | 50.12 | >100 |

| RPMI-8226 | 0.61 | 21.40 | >100 | 0.43 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.05 | 50.12 | >100 |

| SR | 0.20 | 0.89 | >100 | 0.03 | 0.95 | >100 | <0.01 | 0.08 | >100 | <0.01 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | 10.00 | >100 |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | |||||||||||||||

| A549/ATCC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.02 | >100 | >100 | 0.20 | 63.10 | >100 |

| EKVX | 0.46 | 40.70 | >100 | 0.22 | >100 | >100 | 0.24 | >100 | >100 | – | – | – | 63.10 | >100 | >100 |

| HOP-62 | 0.53 | 2.82 | 17.80 | 0.33 | – | >100 | 0.04 | 14.10 | 43.30 | 0.03 | 12.20 | 75.10 | 0.40 | >100 | >100 |

| HOP-92 | 1.09 | 5.18 | 31.80 | 1.42 | >100 | >100 | 11.90 | >100 | >100 | 0.02 | 10.80 | >100 | 79.43 | >100 | >100 |

| NCI-H226 | 2.24 | 41.00 | >100 | 3.25 | >100 | >100 | 10.20 | >100 | >100 | 2.80 | >100 | >100 | 50.12 | >100 | >100 |

| NCI-H23 | 0.93 | 12.00 | 69.40 | 0.51 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | 63.80 | >100 | 0.07 | 13.30 | >100 | 0.32 | 39.81 | >100 |

| NCI-H322M | 0.57 | 9.76 | >100 | 0.36 | >100 | >100 | 0.05 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | >100 | >100 | 0.20 | 7.94 | >100 |

| NCI-H460 | 0.39 | 3.87 | 37.10 | 0.05 | – | >100 | 0.03 | 23.90 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | 50.12 | >100 |

| NCI-H522 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 6.55 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 12.30 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | <0.01 | 0.03 | >100 | 7.94 | 63.10 | >100 |

| Colon cancer | |||||||||||||||

| COLO 205 | 0.39 | 2.45 | 60.80 | 0.22 | 1.89 | >100 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 2.48 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 63.10 | >100 |

| HCC-2998 | 1.04 | 12.40 | 61.10 | 0.30 | >100 | >100 | 0.12 | 31.60 | >100 | 0.05 | 1.98 | >100 | 0.05 | 39.81 | >100 |

| HCT-116 | 0.42 | 1.74 | 6.74 | 0.11 | – | – | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | 10.40 | >100 | 0.25 | 3.98 | 25.12 |

| HCT-15 | 0.54 | >100 | >100 | 0.29 | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | 18.90 | >100 | 0.10 | 50.12 | >100 |

| HT-29 | 0.30 | 0.85 | 11.50 | 0.04 | 0.41 | – | 0.03 | 0.08 | >100 | 0.01 | – | >100 | 0.16 | 63.10 | >100 |

| KM12 | 0.53 | 18.10 | >100 | 0.06 | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | 3.18 | >100 | 0.20 | 39.81 | >100 |

| SW-620 | 0.39 | 12.50 | >100 | 0.05 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.02 | >100 | >100 | 1.00 | >100 | >100 |

| CNS cancer | |||||||||||||||

| SF-268 | 0.68 | 20.60 | >100 | 0.49 | >100 | >100 | 0.05 | 75.20 | >100 | 1.08 | >100 | >100 | 1.58 | >100 | >100 |

| SF-295 | 0.24 | 0.74 | 5.10 | 0.09 | 0.77 | 4.63 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 24.90 | – | – | – | 0.25 | 3.98 | >100 |

| SF-539 | 0.60 | 2.77 | 14.00 | 0.39 | 2.21 | >100 | 0.04 | 1.20 | >100 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 58.70 | 0.06 | 79.43 | >100 |

| SNB-19 | 0.58 | 14.30 | >100 | 0.41 | 4.49 | >100 | 0.06 | 28.30 | >100 | 0.09 | >100 | >100 | 3.98 | 79.43 | >100 |

| SNB-75 | 0.30 | 1.40 | 14.80 | 0.24 | 0.95 | 13.50 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 36.90 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 26.70 | 79.43 | >100 | >100 |

| U251 | 0.45 | 10.50 | 46.80 | 0.42 | 3.57 | >100 | 0.05 | 16.00 | 56.60 | 0.04 | 12.00 | >100 | 1.00 | 79.43 | >100 |

| Melanoma | |||||||||||||||

| LOX IMVI | 0.59 | 3.58 | 32.70 | 0.51 | 2.78 | >100 | 0.07 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | 10.30 | >100 | 0.25 | 50.12 | 79.43 |

| MALME-3M | 0.32 | 10.30 | >100 | 0.11 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | 54.30 | >100 | – | >100 | >100 | 0.05 | 2.51 | >100 |

| M14 | 0.32 | 1.11 | 57.90 | 0.14 | 1.25 | >100 | 0.04 | 2.07 | >100 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 4.29 | 1.00 | >100 | >100 |

| MDA-MB-435 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 2.68 | 0.08 | 79.43 | >100 |

| SK-MEL-2 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 25.40 | 0.15 | 0.74 | >100 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 27.20 | – | >100 | >100 | 63.10 | >100 | >100 |

| SK-MEL-28 | 0.71 | 12.70 | >100 | 0.47 | >100 | >100 | 0.07 | >100 | >100 | 0.07 | >100 | >100 | 1.00 | 63.10 | >100 |

| SK-MEL-5 | 0.26 | – | 54.70 | 0.19 | – | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.02 | 1.85 | 7.08 | 0.50 | 39.81 | 79.43 |

| UACC-257 | – | >100 | >100 | – | >100 | >100 | – | >100 | >100 | 8.08 | >100 | >100 | 3.98 | 79.43 | >100 |

| UACC-62 | 0.45 | 4.25 | 30.80 | 0.35 | 8.90 | >100 | 0.04 | 51.60 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.50 | 39.81 | >100 |

| Ovarian cancer | |||||||||||||||

| IGROV1 | 0.56 | 6.57 | 48.60 | 0.35 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | 64.80 | >100 | 0.42 | >100 | >100 | 1.26 | 31.62 | >100 |

| OVCAR-3 | 0.38 | 1.36 | 7.54 | 0.24 | 1.17 | 5.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 7.79 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 28.60 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 50.12 |

| OVCAR-4 | 2.77 | 39.80 | >100 | 0.96 | >100 | >100 | 0.83 | >100 | >100 | 1.11 | >100 | >100 | 3.98 | 79.43 | >100 |

| OVCAR-5 | 2.01 | 22.80 | >100 | 1.90 | >100 | >100 | 0.32 | >100 | >100 | 0.09 | 69.50 | >100 | 10.00 | 50.12 | >100 |

| OVCAR-8 | 0.48 | 13.20 | 57.00 | 0.43 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | 28.30 | >100 | 0.05 | >100 | >100 | 1.58 | 31.62 | >100 |

| NCI/ADR-RES | 0.37 | 8.09 | 79.50 | 0.08 | – | >100 | 0.03 | 11.70 | >100 | 0.01 | 24.60 | >100 | 0.32 | 12.59 | >100 |

| SK-OV-3 | 0.50 | 2.30 | 11.70 | 0.35 | 2.10 | >100 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 96.90 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 64.20 | 19.95 | 63.10 | >100 |

| Renal cancer | |||||||||||||||

| 786-0 | 0.62 | 2.51 | 8.27 | 0.58 | – | >100 | 0.07 | 32.30 | >100 | 1.15 | 11.40 | >100 | 0.79 | 50.12 | >100 |

| A498 | 0.45 | 1.87 | 6.10 | 0.16 | 1.88 | >100 | 0.03 | 22.30 | >100 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 78.10 | 0.40 | >100 | >100 |

| ACHN | 0.73 | 4.47 | 31.40 | 0.61 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | >100 | >100 | 0.32 | 31.62 | >100 |

| CAKI-1 | 0.32 | 3.55 | 52.50 | 0.06 | – | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.02 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | 2.00 | >100 |

| RXF 393 | 0.47 | 2.58 | 13.70 | 0.41 | 3.14 | >100 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 36.30 | 0.02 | 0.08 | >100 | 2.51 | 31.62 | >100 |

| SN12C | 0.67 | 20.80 | >100 | 0.67 | >100 | >100 | 0.10 | >100 | >100 | 0.09 | >100 | >100 | 0.50 | 25.12 | >100 |

| TK-10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.05 | 75.80 | >100 | 1.26 | 79.43 | >100 |

| UO-31 | 0.39 | 2.36 | 15.50 | 0.16 | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | >100 | >100 | 1.58 | 50.12 | >100 |

| Prostate cancer | |||||||||||||||

| PC-3 | 0.89 | 24.10 | >100 | 0.71 | >100 | >100 | 0.06 | >100 | >100 | 0.02 | >100 | >100 | 2.51 | >100 | >100 |

| DU-145 | 0.56 | 13.70 | >100 | 0.33 | – | >100 | 0.04 | 29.30 | >100 | 0.04 | 16.00 | >100 | 0.40 | >100 | >100 |

| Breast cancer | |||||||||||||||

| MCF7 | 0.57 | 12.30 | 78.90 | 0.32 | >100 | >100 | 0.21 | >100 | >100 | 0.03 | >100 | >100 | 0.08 | 50.12 | >100 |

| MDA-MB-231/ATCC | 0.92 | 10.10 | 58.50 | 1.29 | >100 | >100 | 0.15 | 55.50 | >100 | 0.15 | 26.20 | >100 | 6.31 | 39.81 | >100 |

| HS 578T | 0.57 | 5.97 | >100 | 0.30 | 2.89 | >100 | 0.03 | 16.80 | >100 | 0.02 | 100 | >100 | 10.00 | >100 | >100 |

| BT-549 | 0.74 | 19.60 | >100 | 0.65 | >100 | >100 | – | 60.00 | >100 | 0.20 | 9.26 | >100 | 10.00 | >100 | >100 |

| T-47D | 0.51 | 7.23 | 38.20 | 0.38 | >100 | >100 | – | >100 | >100 | 0.04 | >100 | >100 | 7.94 | 50.12 | >100 |

| MDA-MB-468 | 1.73 | 6.13 | 29.70 | 0.29 | 1.03 | >100 | 0.21 | 0.61 | >100 | 0.05 | 0.41 | >100 | – | – | – |

aData obtained from NCI's in vitro disease-oriented human tumour cell lines screen. bNCI data for 5-FU: NSC 19893. (NCI Anticancer Screening Program; http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/docs/cancer/searches/standard_mechanism_list.html).

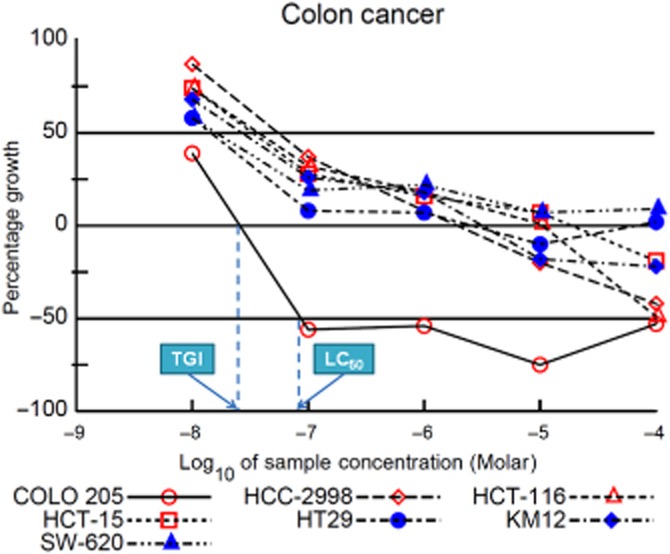

To further determine which cancer subtypes were more sensitive to these 4-benzyloxy-2-quinolones, we calculated subpanel-selectivity ratios based upon GI50 values. The calculated results are shown in Table 2008 and Figure 3. Selectivity ratios less than 3 were rated non-selective, ratios ranging from 3 to 6 were termed moderately selective and ratios greater than 6 were designated highly selective (Boyd and Paull, 1995; Noolvi et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2013a). With all ratios less than 3, compounds 9b and 9c were rated non-selective towards all nine subpanels. Interestingly, both 9e and 11e, which contain a 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy moiety, were much more selective than 9b and 9c (Figure 3). As shown in Table 2008, the average selectivity ratios of 9e and 11e (ratios = 6.51 and 4.05) were higher than those of 9b and 9c (ratios = 1.12 and 1.28). Compound 9e exhibited selectivity against leukaemia, colon cancer, CNS cancer, melanoma, renal cancer and prostate cancer. In terms of the total MID (an average sensitivity across all cell lines), compound 11e displayed significant activity (0.31 μM) and was moderately selective towards the breast cancer subpanel and highly selective against leukaemia, colon cancer and prostate cancer. Among the subpanels rated highly selective, colon cancer was extremely sensitive to compound 11e (NSC 764592; Figure 3). This compound showed exceptional potency against the individual cell line COLO 205 (LC50 0.09 μM, TGI 0.03 μM) (Table 2011). From the dose-response curves against six colon cancer cell lines (Figure 4), it is also obvious that 11e exhibited particular selectivity against COLO 205.

Figure 3.

Subpanel tumour cell lines selectivity ratios of selected compounds 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e.

Figure 4.

Dose-response curves of compound 11e against colon cancer cell lines.

Table 4.

Median growth inhibitory concentration (GI50, μM) and GI50 selectivity ratios of selected compounds in the NCI in vitro 60-cell Drug Screen Program

| Subpanel tumour cell lines | Compounds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9b (NSC 756950) | 9c (NSC 756949) | 9e (NSC 756951) | 11e (NSC 764592) | |||||

| Subpanel MIDb (μM) | Selectivity ratioc | Subpanel MIDb (μM) | Selectivity ratioc | Subpanel MIDb (μM) | Selectivity ratioc | Subpanel MIDb (μM) | Selectivity ratioc | |

| Leukemia | 0.36 | 1.74 | 0.23 | 1.86 | 0.06 | 7.56 | 0.04 | 7.36 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 3.22 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| Colon cancer | 0.52 | 1.21 | 0.15 | 2.75 | 0.05 | 9.09 | 0.03 | 10.42 |

| CNS cancer | 0.48 | 1.31 | 0.34 | 1.24 | 0.04 | 10.28 | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| Melanoma | 0.38 | 1.64 | 0.24 | 1.73 | 0.04 | 10.00 | 1.38 | 0.23 |

| Ovarian cancer | 1.01 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 2.22 | 0.25 | 1.27 |

| Renal cancer | 0.52 | 1.20 | 0.38 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 7.89 | 0.31 | 1.00 |

| Prostate cancer | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 8.57 | 0.03 | 10.42 |

| Breast cancer | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.15 | 2.86 | 0.08 | 3.83 |

| Total MIDa | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.31 | ||||

| Average selectivity Ratio | 1.12 | 1.28 | 6.51 | 4.05 | ||||

aTotal MID = average sensitivity of all cell line in μM. bSubpanel MID = average sensitivity of individual subpanel cell lines in μM. cSelectivity ratio: Total MIDa/Subpanel MIDb.

Morphological changes and apoptosis in COLO 205 cells induced by compound 11e

Based on the in vitro cytotoxicity data, 11e (NSC 764592), the most potent compound against COLO 205 cells was selected for further biological studies. Apoptosis is well known as a process of programmed cell death (Elmore, 2007). In our previous study, 4-phenyl-2-quinolone analogues (4-PQs) induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in both HL-60 and H460 cells (Chen et al., 2013b). In order to characterize the cellular basis for the antiproliferative effects of the selected derivative 11e, we investigated the ability of this compound to induce apoptosis in COLO 205 cells. Morphological analysis confirmed the cytotoxic effects of 11e in COLO 205 cells. As shown in Figure 5A, the apoptotic morphological changes included cell rounding and shrinkage after 24 h incubation with 50 nM of 11e (the black arrowhead indicates an apoptotic nucleus). To confirm the induction of apoptosis by 11e, COLO 205 cells were stained with Hoechst 33258, a fluorescent DNA-staining dye, and cell morphology was investigated using fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 5B, control cells exhibited uniformly dispersed chromatin, homogeneous blue fluorescence in the nuclei, normal organelles and intact cell membranes. In cells treated with 50 nM of 11e for 24, 36 and 48 h, the nuclei budded off into several fragments and nuclear condensation and fragmentation were observed (Figure 5B), indicating typical characteristics of apoptosis, including condensation of chromatin, shrinkage of nuclei and appearance of apoptotic bodies (the black arrowhead indicates an apoptotic nucleus).

Annexin V-FITC/PI double-labelling was used to detect phosphatidylserine externalization, a characteristic effect of apoptosis (van Engeland et al., 1998; Zhuang et al., 2013). In Figure 5C, populations of viable (annexin V–, PI–), early apoptotic (annexin V+, PI–), late apoptotic (annexin V+ , PI+) and necrotic (annexin V–, PI+) cells are found in quadrants (Q) 3, 4, 2 and 1 respectively. Cells incubated in the absence of 11e were undamaged and did not stain for annexin V-FITC and PI (Q3). After incubation with 50 nM of 11e, the number of early apoptotic cells stained positive by annexin V-FITC and negative with PI (Q4) increased significantly with incubation time, from 5.5% (control) to 7.7% after 12 h, 12.7% after 24 h, 20.9% after 36 h and 21.8% after 48 h incubation. The number of late apoptotic cells stained positive by annexin V-FITC and PI (Q2) also increased with incubation time, from 9.9% (control) to 10.2% after 12 h, 10.4% after 24 h, 8.6% after 36 h and 16.1% after 48 h incubation. Thus, when COLO 205 cells were stained with annexin-V/PI and analysed with flow cytometry, early and late apoptotic (annexin-V-stained) cells increased in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5C), which indicates that 11e can induce apoptosis.

Toxicity in COLO 205 cells induced by 11e

Exposure of COLO 205 cells to 11e for 48 h, followed by MTT metabolism assays, showed that 11e reduced COLO 205 cell viability in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 27.2 ± 1.4 nM (Figure 6B). Inhibition of COLO 205 cell growth was also dependent of the time of exposure (24-72h) (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Effects of 11e on the cytotoxicity of COLO 205 cells. (A) Chemical structure of 11e. (B) COLO 205 cells were exposed to different concentrations of 11e for 48 h. (C) COLO 205 cells were exposed to 0, 10, 25, 50, 75 and 100 nM 11e for 24, 48 and 72 h. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. The data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Cells without treatment served as a control. *P < 0.001 versus control.

11e induced apoptotic cell death and interfered with cell cycle distribution in G2/M phase arrest

COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 0, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, followed by flow cytometry analysis to determine the cell cycle distribution of treated cells, as well as to investigate the 11e-induced inhibition of COLO 205 cell growth by cell cycle arrest and apoptotic mechanisms. As shown in Figure 7A, 11e induced a time-dependent accumulation of cells at the G2/M phase.

Figure 7.

11e delays M phase progression and caused microtubule disassembly in cultured cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle distribution in COLO 205 colon cancer cell line treated with 50 nM of 11e for 0, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. (B) The effect of 11e on the microtubule formation in COLO 205 cells. Cells were incubated with 0.1% DMSO, 50 nM 11e, 1 μM colchicine or 1 μM taxol for 24 h. Immunofluorescence for α-tubulin (green) and PI nuclear staining (red). Cells were visualized using confocal microscopy.

11e inhibits microtubule polymerization in COLO 205 cells

COLO 205 cells were treated with 11e (50 nM) for 24 h and then visualized using confocal microscopy to investigate effects on microtubule function. As shown in Figure 7B, treatment with 11e resulted in microtubule changes similar to those induced by colchicine. Both compounds caused cellular microtubule depolymerization with short microtubule fragments scattered throughout the cytoplasm. In contrast, another anti-cancer drug, taxol, significantly increased tubulin polymerization.

Molecular modelling and computational studies

Using a molecular docking method and molecular mode of tubulin and DAMA-colchicine, 11e was docked into the colchicine-binding domain of tubulin. As shown in Figure 8A and B, 11e inserted deeply into the colchicine-binding pocket of α- and β-tubulin, very similar to the binding mode of DAMA-colchicine. Superimposition of compounds in the colchicine-binding site indicated that ring C and ring A are comparable pharmacophores between DAMA-colchicine and 11e (Figure 8C and D). As shown in Figure 8D, the 1-NH group of 11e overlapped with the acetamide-NH group of DAMA-colchicine. Moreover, the 1-NH of 11e formed a hydrogen bond with Thr179α as was also observed with the acetamide-NH group of DAMA-colchicine. The -O-CH2- group of 11e occupied a region in space in proximity to the C5 and C6 positions in the B-ring of DAMA-colchicine and was involved in hydrophobic interactions with Lys254β, Ala250β and Leu248β. The 3′,5′-dimethoxy of 11e overlapped with the 1,3-dimethoxy moiety in the C ring of DAMA-colchicine, the C ring was involved in hydrophobic interactions with Leu255β. Finally, the quinolin-2(1H)-one scaffold of 11e partly overlapped with the A ring of DAMA-colchicine and formed hydrophobic interactions with Asn258β and Lys352β.

Figure 8.

The docked binding mode of 11e is shown with the binding site of tubulin (PDB entry 1SA0). The figures were performed using PyMol. (A) The binding mode of DAMA-colchicine (red stick model) and tubulin. (B) The binding mode of 11e (yellow stick model) and tubulin. (C) DAMA-colchicine and 11e occupy similar binding space in tubulin (shown as surface of tubulin cavity). (D) The superimposition of DAMA-colchicine and 11e.

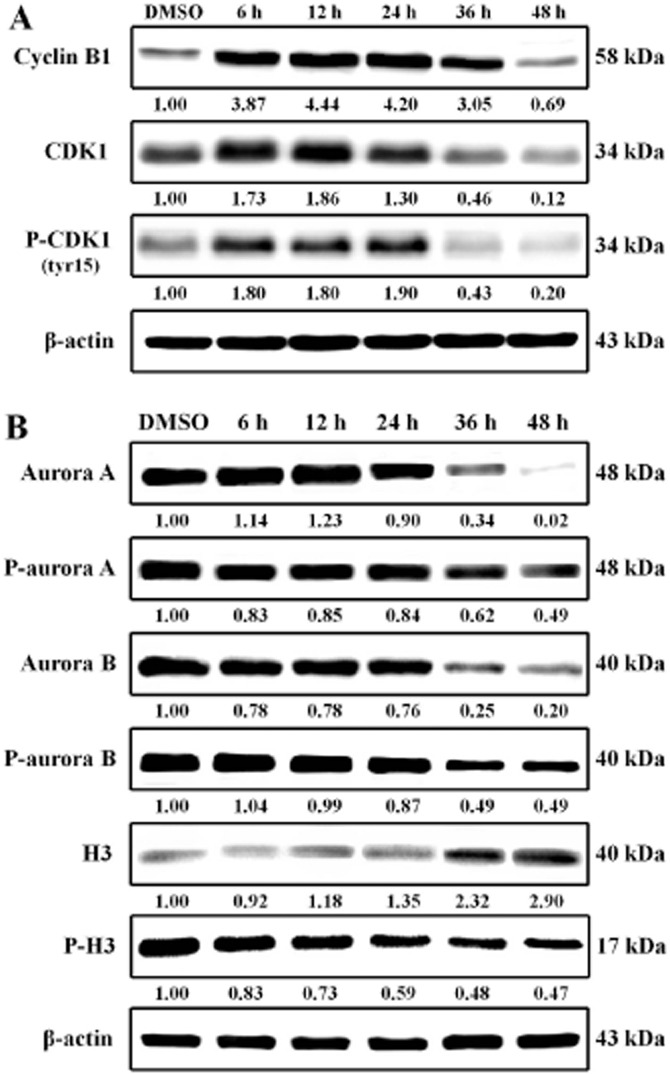

11e changes the expression and phosphorylation status of G2/M regulatory proteins in COLO 205 cells

Analysis of cell cycle-related protein expression explored the mechanisms by which 11e induces G2/M arrest. Firstly, COLO 205 cells treated with 50 nM of 11e showed increased cyclin B1 and CDK1 protein levels, which are markers for induction of mitotic arrest (Figure 9A). Secondly, given the importance of the aurora kinases in cancer cell mitosis and metastasis, the effects of 11e (50 nM in COLO 205 cells) on aurora kinase function were investigated. As shown in Figure 1B, 11e decreased aurora A, phospho-aurora A, aurora B and phospho-aurora B expression. Thirdly, we examined whether 11e inhibited phosphorylation of histone H3 in COLO 205 cells. Histone H3 is a substrate for aurora B kinase. During mitosis, aurora B is required for phosphorylation of histone H3 on Ser10, which might be important for chromosome condensation (Keen and Taylor, 2004). As shown by Western blot analysis, 11e decreased phospho-H3 expression after a 6 h treatment (Figure 9B). This finding suggests that inactivation of aurora kinases A and B is involved in 11e-induced G2/M arrest.

Figure 9.

Compound 11e increased G2/M phase checkpoint protein expression. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated time periods and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to cyclin B1, CDK1, phospho-CDK1 (A), aurora A, phospho-aurora A, aurora B, phospho-aurora B, H3, phospho-H3 (B) and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

11e-induced apoptosis associated with caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9 and PARP cleavage

To confirm the possibility that 11e-induced apoptosis is related to activation of the intrinsic or extrinsic signalling pathway, COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, and then the activities of caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 were determined using a Western blot assay. As shown in Figure 10, 11e induced significant caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity. Results from the Western blot assay also indicated that 11e induced PARP cleavage, which is an important apoptosis marker. PARP is cleaved by caspase-3 between Asp214 and Gly215 to yield p85 and p25 fragments.

Figure 10.

Compound 11e induced caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity in COLO 205 cells. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated times and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to caspase-9, caspase-8, caspase-3, PARP and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 11.

Compound 11e induced the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway in COLO 205 cells. (A) Effects of 11e on mitochondrial membrane potential in COLO 205 cells. Cells (1 × 106 cells·mL−1) were untreated or treated with 11e (50 nM, 6–48 h) to induce apoptosis. Cells were stained with JC-1 and analysed by flow cytometry. (B) COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated times and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to AIF, Endo G, Apaf-1, cytochrome c and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). (C) Compound 11e affected Bcl-2 family proteins in COLO 205 cells. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated times and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to Bid, Bax, Bad, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Intrinsic apoptotic pathway proteins are modulated during 11e-induced apoptosis

The mitochondria are key organelles in the control of apoptosis. Accordingly, we investigated whether 11e was capable of inducing depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) using JC-1, a lipophilic fluorescent cation that incorporates into the mitochondrial membrane. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, followed by staining with JC-1, to confirm apoptosis as the cause of decreased Δψm. As shown in Figure 1A, in healthy cells with high mitochondrial Δψm, JC-1 spontaneously formed complexes known as JC-1 polymer (P2), which showed intense red fluorescence (0 h). Over time, the percentage of cells with reduced red fluorescence (P3) showed a significant increase. This effect is indicative of a change in Δψm in the population in which apoptosis was induced (6–36 h). Moreover, it is well known that the dissipation of Δψm causes release of cytochrome c, Apaf-1, apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and Endo G into the cytosol, with consequent activation of the execution phase of apoptosis. In this study, we also demonstrated that mitochondrial cytochrome c, Apaf-1, AIF and Endo G were released into the cytosol during 11e-induced apoptosis (Figure 1B).

Bcl-2 family proteins are key regulators of mitochondrial-related apoptotic pathways (Zhai et al., 2008; Roy et al., 2014). Some of these proteins, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, are anti-apoptotic (prosurvival) proteins, whereas others, such as Bad, Bax and Bid, are pro-apoptotic proteins. The Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins are located in the outer mitochondrial membrane and are necessary for maintaining mitochondrial integrity. Furthermore, phosphorylation is a common characteristic of destabilized mitochondria. The balance of pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins influences the sensitivity of cells to apoptotic stimuli (Brunelle and Letai, 2009). Previous research has shown that an increase in the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 within a cell predisposes it to certain apoptotic stimuli. Bax and Bak induce the release of cytochrome c and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, whereas Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL inhibit these effects. Because 11e results in caspase-9 activation, which is also a mitochondria-mediated caspase, we sought to determine whether 11e would affect the protein levels of these Bcl-2 family members. To confirm the involvement of Bcl-2 protein activity in 11e-induced apoptosis, COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. As shown in Figure 1C, results indicated that 11e reduced anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL levels and increased proapoptotic Bax and Bad levels, leading to changes in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and the release of cytochrome c, which in turn activates cleavage of caspase-9 and activation of caspase-3. These results demonstrate that 11e-induced cell apoptosis involves the mitochondria-dependent pathway in COLO 205 cells.

Effects of 11e on death receptors and expression of their ligands

Upon binding to their ligands, death receptors trigger apoptosis by stimulating caspase-8 mediated caspase cascades. In this study, expression of several death receptors (Fas, DR4 and DR5) and their ligands (FasL and TRAIL) were detected in COLO 205 cells (Figure 2). Compound 11e treatment induced an increase in DR5, but did not alter Fas levels. These results suggest that DR5 up-regulation plays an important role in 11e-mediated apoptosis through the extrinsic signalling pathways in COLO 205 cells.

Figure 12.

Compound 11e-induced death receptor apoptosis pathways in COLO 205 cells. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated times and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to Fas, TNFR1, DR4, DR5 (A), FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL (B) and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

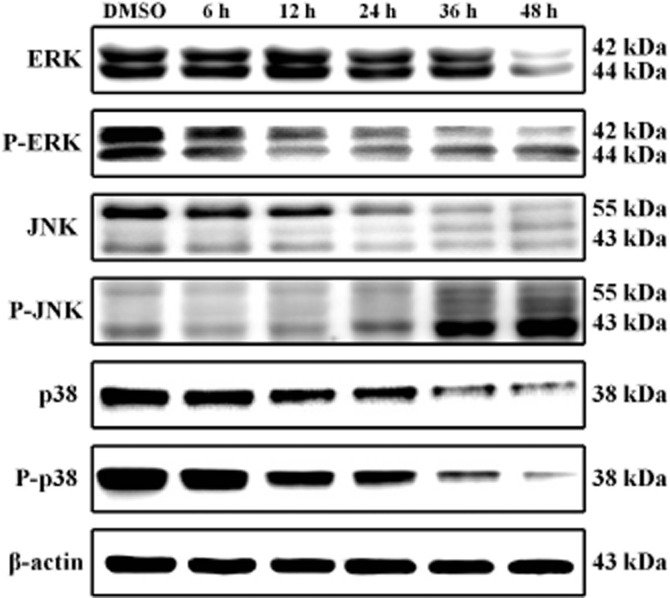

11e-induced apoptosis is mediated via JNK signalling pathway

MAPK respond to extracellular stimuli and regulate cellular activities, such as gene expression, mitosis, differentiation and cell survival/apoptosis. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM of 11e for 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h to investigate the effects of 11e on ERK1/2, JNK and p38 signalling pathways. As shown in Figure 3, 11e decreased phospho-ERK1/2, p38 and phospho-p38 expression and induced JNK phosphorylation after 12 h incubation. These observations suggest that JNK activation is involved in 11e-induced apoptosis.

Figure 13.

Expression of MAPKs in the 11e-treated COLO 205 cells. COLO 205 cells were treated with 50 nM 11e for the indicated times and lysed for protein extraction. Protein samples (40 μg protein per lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific to ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2, JNK, phospho-JNK, p38, phospho-p38 and β-actin (n = 3 independent experiments). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Discussion and conclusion

In our continuing investigations of 4-PQ, new 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-one derivatives (7a–e ∼ 15a–e) were designed and synthesized. In these novel molecules, the 2-quinolone central scaffold of 4-PQ is retained, but the linkage to the 4-phenyl aromatic ring has been extended by the addition of a CH2O moiety, making a more flexible bridge. Nine compounds (7e, 8e, 9b, 9c, 9e, 10c, 10e, 11c and 11e) displayed high potency against HL-60, Hep3B, H460 and COLO 205 cells (IC50 < 1 μM) without affecting normal human Detroit 551 cells (IC50 > 50 μM). Among them, 11e exhibited the highest potencies against these four tumour cell lines with IC50 values of 0.014, 0.035, 0.04 and 0.028 μM respectively. Notably, compound 11e exhibited improved cytotoxicity in comparison with 6,7-methylenedioxy-4-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)quinolin-2(1H)-one, the most potent 4-PQ analog previously reported (IC50 0.4, 1.0, 0.9 and 7.4 μM against the four tumour cell lines) (Chen et al., 2013b). SAR study on these new compounds revealed that a 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzyloxy moiety, linked at the 4-position of a 6-methoxy-2-quinolone backbone is most favourable for increased antiproliferative activity.

In the NCI-60 assay, compounds 9b, 9c, 9e and 11e showed broad-spectrum antitumour properties at the nanomolar level. In particular, compound 11e not only inhibited the growth of numerous cancer cell lines at the low micromolar range, but also exhibited high selectivity against COLO 205 (colon cancer). Furthermore, the preliminary biological studies indicated that compound 11e inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis in COLO 205 cells. Based on these results, compound 11e has been identified as a promising hit and candidate for future development.

Investigation of the anticancer activity of this novel 2-quinolone analogue provided data indicating that 11e exerted highly antiproliferative activity and cytotoxicity against COLO 205 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 6C), resulting in G2/M arrest and apoptosis (Figure 7A). Microtubules are important cellular targets for anticancer therapy because of their key role in mitosis (Perez, 2009). Microtubule-targeting agents, including the taxanes, Vinca alkaloids and colchicine, bind to different sites on tubulin and affect stabilization or destabilization of microtubule dynamics (Dumontet and Jordan, 2010). To clarify the molecular regulation of 11e in G2/M arrest, we first examined its influence on microtubules. Our data showed that 11e results in the depolymerization of microtubules in COLO 205 cells and disrupts intracellular microtubule networks in intact cells, as shown in the immunofluorescence studies (Figure 7B). Treatment of 11e for 24 h resulted in microtubule changes similar to those induced by colchicine. The docked conformation of 11e was selected as a working model (Figure 8), based on its similarity to the crystal structure of the bound conformation of DAMA-colchicine in tubulin. The superimposition of 11e and DAMA-colchicine based on A ring showed an extensive overlap of the 2-quinolone cores and C rings of both molecules had similar orientations. This result supports the hypothesis that the spatial arrangement of the aromatic A and C ring plays a crucial role in the activity and binding of compounds that bind to the main binding site of the colchicine domain on α- and β-tubulin. These findings characterize 11e as an antimitotic agent.

Previous investigations have reported that cyclin B1/CDK1 complexes are involved in the regulation of G2/M phase and M phase transitions (Peters, 2006; Yang et al., 2009). Our data showed increased levels of cyclin B1/CDK1 after 11e treatment within 6 to 24 h of treatment (Figure 9A). These results reveal that treatment with 11e not only directly contributes to disrupting microtubules in COLO 205 cells, but also induces accumulation of cyclin B1/CDK1. Aurora kinases also play important roles in chromosome alignment, segregation and cytokinesis during mitosis (Andrews, 2005; Fu et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007). Our data showed decreased aurora A, phospho-aurora A, aurora B, phospho-aurora B and phospho-H3 expression after 11e treatment (Figure 9B). Therefore, 11e inhibited the growth of COLO 205 cells and arrested cells at the G2/M phase through the inactivation of aurora kinases.

Apoptosis induced by antimitotic agents is known to be related to alterations of cellular signalling pathways (Bhalla, 2003; Jordan and Wilson, 2004). Compound 11e not only demonstrated broad-spectrum anticancer effects but also produced apoptosis, as shown by the findings of annexin V/PI in COLO 205 cells. Apoptosis regulators have been extensively studied and provide the basis for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at promoting tumour cell death (Lowe and Lin, 2000; Ghobrial et al., 2005). To investigate the involvement of apoptosis pathways in 11e-mediated cytotoxicity, we assessed the caspase cascades. The results showed that 11e induced significant caspase-3, caspase-8 and caspase-9 activities (Figure 10). Moreover, caspase 8 is one of the caspases involved in the extrinsic pathway, while caspase-9 acts in the intrinsic pathway.

The intrinsic pathway is initiated with loss of membrane potential in mitochondria and then the release of cytochrome c, AIF and Endo G from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cytochrome c in conjunction with Apaf-1 and procaspase-9 form an apoptosome. This complex promotes the activation of caspase-9, which in turn activates caspase-3, leading to apoptosis (Green and Reed, 1998; Dlamini et al., 2004; Eberle et al., 2007). Proteolytic degradation of PARP, a substrate of caspase-3, indicated that caspase activation was involved in 11e-induced apoptosis in COLO 205 cells (Figure 10B). To confirm that mitochondria-mediated intrinsic pathways were involved in 11e-mediated apoptosis, we further monitored the changes of mitochondrial membrane potential. Our data showed a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in cells treated with compound 11e (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows that compound 11e induce a time-dependent effect on cytochrome c, AIF and Endo G translocation from the mitochondria into the cytosol. The Bcl-2 family proteins largely mediate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. These proteins include proapoptotic members, such as Bax and Bad, which promote mitochondrial permeability, and anti-apoptotic members, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, which inhibit the proapoptotic protein effects or inhibit the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c (Antonsson et al., 1997; Bagci et al., 2006). Overexpression of Bcl-2 increases cell survival by suppressing apoptosis. Bax levels increase in conjunction with Bax inhibition of Bcl-2 and the cells undergo apoptosis (Gross et al., 1999; Vela et al., 2013). The present results showed that 11e treatment resulted in a decrease in the level of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 as well as an increase in the level of proapoptotic protein Bax and Bad (Figure 1C).

The extrinsic pathway is initiated by ligation of transmembrane death receptors (Fas, DR4/5 and TNFR1) with their respective ligands (FasL, TRAIL and TNFα) triggering the formation of a death-inducing complex to active caspase-8, which in turn cleaves and activates caspase-3 (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998; Thorburn, 2004). Enhanced TRAIL expression and stimulation of DR4- and/or DR5-induced apoptosis has been shown in certain types of cancers, including colon, ovarian, prostate, bladder and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (O'Flaherty et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2013). In the present study, we found that 11e treatment up-regulated the expression of the DR5 protein and influenced the expression of TRAIL (Figure 2). Caspase-8 is activated by the death receptor. Activated caspase-8 can cleave and activate downstream caspase-3. On the other hand, caspase-8 can induce Bid cleavage and the cleaved Bid causes cytochrome c efflux from mitochondria, then activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3. We showed that 11e induced the cleavage of full-length Bid producing truncated Bid (t-Bid, 17 kDa), which translocated to the mitochondria. These findings together suggest that 11e induced apoptosis by activating both intrinsic and extrinsic signalling pathways.

MAPKs, which belong to a large family of serine-threonine kinase, are critical mediators of the cell membrane to nucleus signal transduction in response to various extracellular stimuli (Pearson et al., 2001; Fang and Richardson, 2005). The three major subfamilies of MAPK include the ERKs, JNK and p38. Recent studies have shown that JNKs and p38 pathways are associated with increased apoptosis, whereas the ERK1/2 pathway is shown to suppress apoptosis. In our experiments, we observed that after 24 h incubation, 11e increased levels of phosphorylated JNK in COLO 205 cells (Figure 3). TRAIL can also activate JNK through the adaptor molecules TRAF2 and RIP (Lin et al., 2000) and JNK is activated by TRAIL in colon cancer cells (Mahalingam et al., 2009). In our study, 11e-activated JNK might play a mediated role in TRAIL-induced apoptosis in COLO 205 cells.

In summary, our present study has identified novel 4-benzyloxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones as potent inducers of apoptosis in a range of cancer cells. This new series of compounds could be further exploited to obtain analogues with higher activity for cancer chemotherapy. Figure 4 summarizes the molecular signalling pathways induced by 11e. We demonstrated that compound 11e exhibited broad-spectrum anticancer properties against several solid tumour cells and exerted potential anticancer activity against COLO 205 cells. Based on our mechanistic results, compound 11e caused tubulin depolymerization, aurora A and aurora B inactivation, G2/M phase arrest, polyploidy and subsequent apoptosis via both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. These findings suggest that compound 11e has potential use as a novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of human colon carcinoma.

Figure 14.

The signalling pathways of 11e-induced G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in human colon cancer COLO 205 cells.

Acknowledgments