Abstract

Evolution and design of protein complexes is almost always viewed through the lens of amino acid mutations at protein interfaces. We showed previously that residues not involved in the physical interaction between proteins make important contributions to oligomerisation by acting indirectly or allosterically. Here, we sought to investigate the mechanism by which allosteric mutations act using the example of the PyrR family of pyrimidine operon attenuators. In this family, a perfectly sequence-conserved helix that forms a tetrameric interface is exposed as solvent-accessible surface in dimeric orthologues. This means that mutations must be acting from a distance to destabilize the interface. We identified eleven key mutations controlling oligomeric state, all distant from the interfaces and outside ligand-binding pockets. Finally, we show that the key mutations introduce conformational changes equivalent to the conformational shift between the free versus the nucleotide-bound conformations of the proteins.

Introduction

Proteins diverge during the course of evolution and experience a continuous trade-off between selection for function and stability (1). Gould and Lewontin described how organisms adapt to different competing demands, while at the same time accumulating traits that occur either due to drift or correlations with selected features (2). This view can also be applied to proteins, where mutations of individual residues interact and determine fitness, similar to mutations in genes at the level of organisms (3). Selection is then determined by conditions, both internal (interactions with other macromolecules in the cell), and external (environmental variables, e.g. temperature or pH). Furthermore, due to the difference in the sizes of sequence and structure space, proteins can accumulate destabilizing mutations, as long as they remain stable enough at given conditions (4).

In previous work, we showed that mutations outside protein interfaces are as important for the evolution of quaternary structure/oligomeric state as mutations directly within interfaces (5). This raised the following question: by what mechanism do mutations outside interfaces affect their formation? The most likely hypothesis is that these mutations act by changing either protein conformation or conformational dynamics, analogous to the ways in which allosteric ligands introduce conformational change. Thus we referred to the indirect mutations as allosteric mutations.

Furthermore, the conformational dynamics of proteins enable functional features such as ligand binding, and also contribute to evolutionary plasticity, i.e. “evolvability”. Protein dynamics are essential for the functions of many proteins (6), and are more conserved at the superfamily level than sequence (7). Selection favours mutations of side chain interactions that promote acquisition of the folded state. In the same way, selection is stronger on functionally relevant conformations of the entire protein structural ensemble (8). Importantly, the conformation under strongest constraint is not the one with the lowest free energy, but rather the one most similar to the functional, often ligand-bound, state.

The protein family we study here is a group of pyrimidine attenuator regulatory proteins, PyrR, present in the Bacillaceae family as well as in some other bacterial species (9). The PyrR family shows clear evidence of mutations acting allosterically with respect to the protein interface. The change from homodimeric to homotetrameric family members is unmistakably brought about by allosteric mutations: homologues with different oligomeric states share a helix whose surface is 100% conserved in sequence. This helix forms the tetrameric interface in the homotetrameric family members, but is solvent-exposed in the dimeric family members.

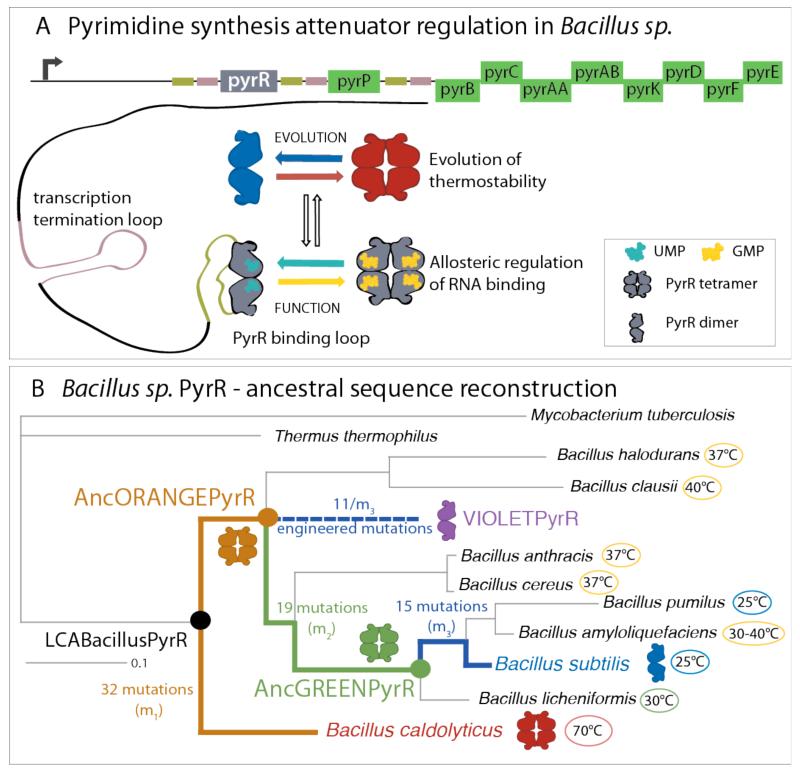

Bacillaceae live at a wide range of temperatures, to which the PyrR proteins have adapted. At the same time PyrR is constrained by the need to conserve its dsRNA-binding ability and allosteric regulation by nucleotides. PyrR binds to a stem-loop structure in the nascent mRNA of the pyr operon, which induces formation of the termination loop and attenuates transcription. UMP and GMP allosterically regulate binding of PyrR to RNA, reflecting the ratio between purines and pyrimidines in the cell (10, 11) (Figure 1). As the name suggests, excess pyrimidines as reflected in UMP binding attenuate further transcription of the pyr operon.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the pyrimidine operon attenuator system in Bacillus sp. Attenuator protein, PyrR, binds to the PyrR binding loop as a dimer. UMP allosterically promotes the binding of RNA, while addition of GMP decreases the affinity for RNA (11). Different Bacillus species live in different environments and are adapted to different optimal growth temperatures. (B) The phylogenetic tree of Bacillus PyrR proteins (inferred using Bayesian MCMC) shows the variety of optimal growth temperatures for different Bacillus species: Bacillus caldolyticus, lives at temperatures higher than 70 °C and, at room temperature, its PyrR is a homotetramer. Bacillus subtilis optimal growth temperature is 25 °C, and at room temperature, its PyrR is in equilibrium between a homodimer and a homotetramer (illustrated as just a dimer for simplicity). Analysis of the reconstructed ancestral sequences shows that the change from a tetramer to a dimer, occurred on the final (blue) branches of the tree, where 15 allosteric mutations (m3) turn a tetrameric AncGREENPyrR into a dimeric BsPyrR. A subset of eleven of those allosteric mutations (11/m3) also switches the oligomeric state in the context of the ancestral AncORANGEPyrR.

In this work we use ancestral sequence reconstruction to infer the allosteric mutations that changed the oligomeric state and thermostability in the PyrR family during the course of evolution. We identify eleven allosteric mutations that decrease thermostability in all PyrR proteins, but change the oligomeric state only in the context of inferred ancestral PyrR proteins, and not in thermophilic PyrR. We show how these mutations affect oligomeric state indirectly, and describe this allosteric mechanism: the same internal conformational switch in PyrR proteins is toggled both by an allosteric ligand (GMP), and by a small number of mutations.

Results and discussion

Close homologues of PyrR have conserved interface amino acids but different oligomeric states

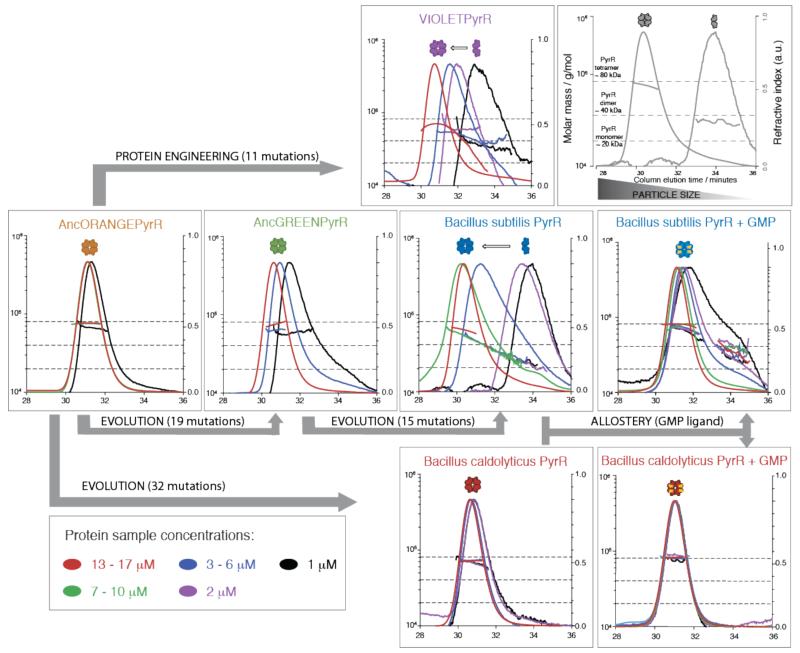

Using size-exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) at room temperature and velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) at 10 °C, we observed that the PyrR oligomeric state differs between B. caldolyticus and B. subtilis homologues, and is affected by allosteric regulators such as GMP (Figure 2). Bacillus caldolyticus has an optimal growth temperature of 72 °C, and its PyrR (BcPyrR) elutes as one peak corresponding to a tetramer (Figure 2). Velocity AUC experiments show that the majority of BcPyrR sediments as a tetramer with a minor monomeric species and no apparent dimeric species (Figure S4). Bacillus subtilis has an optimal growth temperature of 25 °C, and BsPyrR elutes from the size-exclusion column as a broad peak with a range of molecular masses between monomeric, dimeric and tetrameric oligomeric state (Figure 2). In the velocity AUC experiment for BsPyrR, two species were observed to sediment, calculated to have molecular masses corresponding to that of a PyrR dimer and tetramer respectively (Figure S4). Therefore, BsPyrR exists as a dimer in equilibrium with the monomeric and tetrameric species at low micromolar concentrations, which correspond to the physiological range, as the estimated average concentration of PyrR in B. subtilis cells is 0.4 μM (12).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of PyrR oligomeric states. Samples of AncORANGEPyrR, AncGREENPyrR, Bacillus subtilis PyrR (BsPyrR), BsPyrR + GMP, Bacillus caldolyticus PyrR (BcPyrR), BcPyrR+GMP, and VIOLETPyrR at varying concentrations were separated by size-exclusion chromatography prior to determination of the excess refractive index and multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) from which the molecular masses are determined. Horizontal dashed lines represent the expected masses for monomeric, dimeric and tetrameric PyrR species, respectively.

BcPyrR and BsPyrR have the highest sequence identity of all PyrR homologues of known 3D structure with different oligomeric states: 73% sequence identity over 180 residues, corresponding to 49 substitutions, most of which are on the solvent-exposed surface of the protein. Interestingly, the residues involved in the tetrameric (dimer-of-dimers) interface are 100% sequence-identical. These interface residues are also likely involved in RNA-binding (13), and hence under purifying selection (Figure S2).

A small number of allosteric mutations change the oligomeric state of PyrR

The PyrR protein is present in various Bacillus species with diverse optimal growth temperatures, as well as the distantly related bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Thermus thermophilus, as shown in the phylogenetic tree of this protein family (Figure 1B). In order to trace the mutations changing the oligomeric state between the thermophilic BcPyrR (red) and mesophilic BsPyrR (blue), we focused on the two internal nodes in the phylogenetic tree after the split of the BcPyrR from the last common ancestor of the Bacillus sp. PyrR (LCABacillusPyrR). We reconstructed the most likely ancestral sequences of the internal nodes (14). Please refer to the Methods for details. In analogy to the colour wheel, we named the two inferred ancestral proteins AncORANGEPyrR and AncGREENPyrR (Figure 1B)

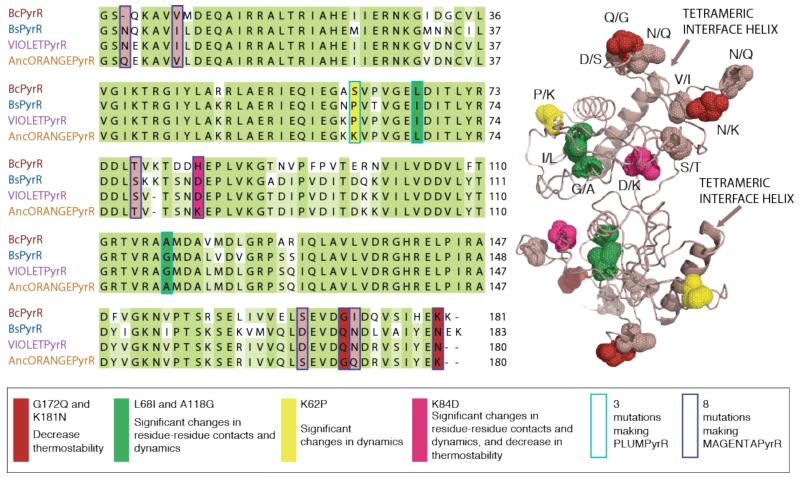

SEC-MALS revealed AncORANGEPyrR formed a stable tetramer, and AncGREENPyrR only showed a decrease in the average molecular mass at the lowest concentration (1 μM) from which we imply a presence of a low concentration of lower oligomeric state species (Figure 2). In AUC analysis, both ancestral proteins displayed similar distributions of sedimenting species, as seen for BcPyrR (Figure S4). Therefore, we infer that evolution of the dimeric state occurred toward the terminal branches of the PyrR phylogenetic tree, between AncGREENPyrR and BsPyrR. There are twelve substitutions and three insertions/deletions (a set of fifteen mutations we refer to as m3) between AncGREENPyrR and BsPyrR (Figure S19). As our goal is to identify the smallest subset of allosteric mutations that clearly change the oligomeric state we excluded four of these mutations: three insertions/deletions and one (E4Q) substitution which is a revertant to the same amino acid as in the tetrameric BcPyrR. Two of the insertions/deletions were at each of the termini, and the third one was in a flexible loop. We would not expect these three changes to have a significant effect on the structure. Eleven substitutions (11/m3) were different between BsPyrR and all the tetrameric PyrRs (BcPyrR, AncORANGEPyrR and AncGREENPyrR). In order to confirm their role in the shift of the oligomeric state, we inserted them into the stable PyrR tetramer AncORANGEPyrR, producing the engineered protein VIOLETPyrR (Figure 3). The eleven substitutions did indeed destabilize the AncORANGEPyrR tetramer: VIOLETPyrR has similar SEC-MALS and AUC profiles as BsPyrR (Figures 2 and S4). Thus, remarkably, these mutations, none of which are in the tetrameric interface, shift the oligomeric state through an indirect, allosteric mechanism.

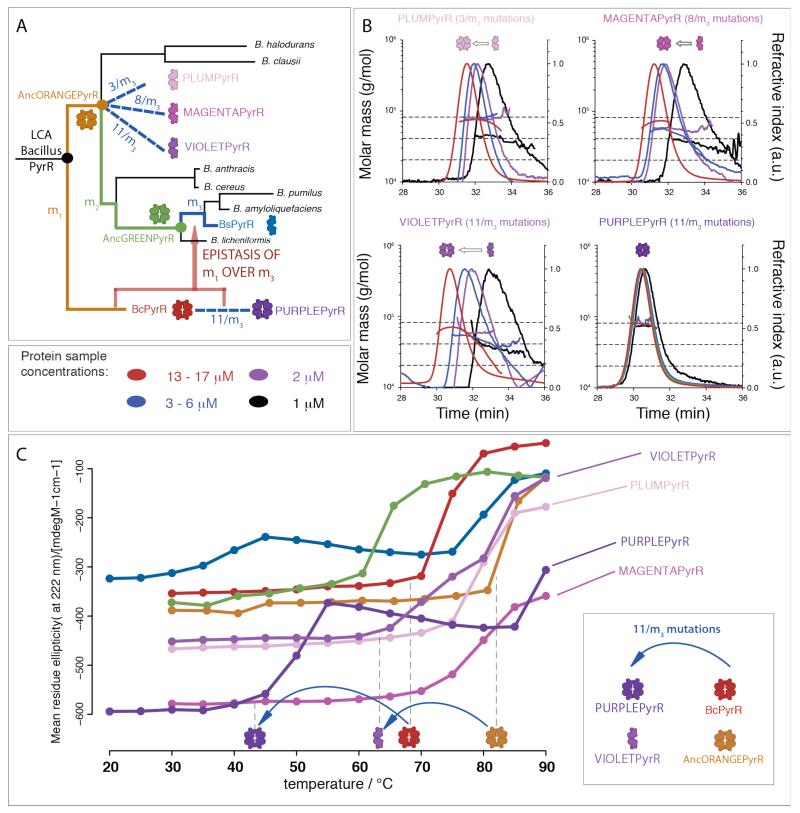

Fig. 3.

Allosteric mutations affect oligomeric state and thermostability. (A) Summary of the effects of allosteric mutations on oligomeric state along the PyrR phylogenetic tree. (B) Two non-overlapping subsets of the eleven allosteric mutations (3/m3 mutations (PLUMPyrR), and 8/m3 mutations (MAGENTAPyrR)) are enough to overcome the threshold and cause instability of the tetramer sufficient at 1 μM protein concentrations. All eleven allosteric mutations (11/m3) together (VIOLETPyrR) have a larger effect on the stability of the tetramer than the 3/m3 and the 8/m3 individual subsets of mutations. The eleven allosteric mutations change oligomeric state only in the context of AncORANGEPyrR (or AncGREENyrR), but not in the context of BcPyrR. This is due to the epistasis of (a subset of) m1 mutations over the m3 mutations. (C) Oligomeric state and thermostability are coupled in PyrR, but it is the thermophilic propensity of residues, not the oligomeric state that determines thermostability. Thermal unfolding of PyrR homologues, inferred from circular dichroism at 222 nm at temperatures ranging from 30 to 90 °C (from 20 to 90 °C for BsPyrR and PURPLEPyrR). Loss of CD signal at 222 nm is interpreted as the loss of helicity. The circular dichroism (CD) signal is plotted as the mean residue ellipticity corrected for protein concentration.

Do these mutations turn any PyrR homologue into a dimer? We grafted the eleven allosteric mutations into the tetrameric BcPyrR, forming the engineered protein PURPLEPyrR. Surprisingly, PURPLEPyrR remains tetrameric, even at lowest concentration (Figures 3B and S4). This implies that these eleven allosteric mutations have an epistatic interaction with the 32 m1 mutations that separate BcPyrR and AncORANGEPyrR. Epistasis between amino acid substitutions is known to be ubiquitous in proteins, as described in multiple recent publications (3, 15, 16).

In order to pinpoint the key oligomeric state-switching mutations, we further tested the effect of two non-overlapping sets of residues within the eleven allosteric mutations, represented by PLUMPyrR (3/m3) and MAGENTAPyrR (8/m3). We selected the three mutations in PLUMPyrR based on the proximity of these residues to the dimeric interface, expecting them to have the largest impact on the inter-subunit geometry. Both subsets of mutations had independent effects on the oligomeric state (Figure 3), as the equilibria of both PLUMPyrR and MAGENTAPyrR were shifted towards the dimeric state at the lowest protein concentrations in SEC-MALS, with the appearance of a dimeric species in AUC (Supp. Fig 4). This implies that these two small sets of mutations contribute to the oligomeric shift in a cumulative manner.

The eleven mutations that shift PyrR oligomeric state are part of a downhill adaptation to temperature

Members of the Bacillus genus live in dramatically different environments, the most notable difference being ambient temperature. Hobbs et al (17) have shown that the Bacillus species have adapted to different temperatures multiple times in evolution. B. subtilis (with the homodimeric BsPyrR) lives in soil with optimal growth at 25 °C, and B. caldolyticus (with the homotetrameric BcPyrR) in alkaline hot springs with the optimal growth at 72 °C (18).

We recorded the circular dichroism (CD) spectra at temperatures from 20 to 90 °C for all of our PyrR constructs (Figure 3C). Their thermal unfolding was irreversible, and all but BsPyrR and PURPLEPyrR unfolded in a single phase. This was sufficient to estimate the thermal stability of PyrR proteins along the evolutionary tree. BcPyrR shows no variation in the CD spectra up to 70 °C, when it suddenly unfolds cooperatively. BsPyrR however, exhibits changes in helicity at temperatures as low as 35 °C, finally unfolding completely at 75 °C. We could not determine from the CD spectra which of the secondary structure changes occur at low temperatures in BsPyrR. However, plotting ellipticity for different wavelengths suggests an exchange between α helical and β sheet structure (Fig. S5).

AncORANGEPyrR thermal unfolding follows the same pattern as that of BcPyrR, with unfolding taking place at 80 °C rather than 70 °C. This stabilization of 10 °C is most probably an artefact of ancestral protein sequence reconstruction, which has been suggested to overestimate protein stability due to a bias towards more stabilizing mutations in the evolutionary substitution models (19). Notably, VIOLETPyrR, which differs from AncORANGEPyrR by just the eleven mutations, unfolded at a significantly lower temperature than AncORANGEPyrR, while PLUMPyrR and MAGENTAPyrR have intermediate thermostability (Figure 3C).

This raises the question as to the mechanism for the thermal destabilizing effect of the eleven mutations. They could be affecting thermal destabilisation through the switch in oligomeric state, or by changing the polarity of the protein surface. Both residue composition and oligomeric state have been suggested to play a role in protein thermostability (20). A higher oligomeric state is proposed to increase thermostability by burying more residue surface area. It has also been repeatedly observed that thermophilic bacteria have more charged residues and fewer polar residues compared to mesophilic organisms. This bias is especially pronounced when only surface residues are taken into account (21).

To deconvolute whether it is the residue propensity or the oligomeric state that plays the main role in the differences in thermostability of PyrR, we took advantage of the engineered PURPLEPyrR, which has the eleven allosteric mutations, but is still tetrameric. Although all but the eleven allosteric residues of PURPLEPyrR are the same as in the thermophilic BcPyrR, the CD measurements show that tetrameric PURPLEPyrR has significantly decreased thermostability compared to that of BcPyrR. We thus infer that it is the change in thermophilic propensity of surface residues, and not the change in the oligomeric state, that plays a major role in the change of PyrR thermostability.

In order to dissect this in detail, we bioinformatically define the residue thermophilic propensity as the log ratio of amino acid frequencies between the solvent-exposed surfaces of proteins from thermophilic and mesophilic organisms (21). Thus we calculated how mutations along the PyrR tree change this thermophilic propensity. As expected, the mutations increase the thermophilic propensity on the branches from AncORANGEPyrR towards BcPyrR, and decrease towards BsPyrR. Moreover, the largest decrease in thermophilic propensity occurs between AncGREENPyrR and BsPyrR, the branch that also corresponds to the switch towards the dimeric state (Figure S6).

From this, we infer that the eleven allosteric mutations are part of a more general “downhill” adaptation to lower temperatures. Thus the switch in oligomeric state of free PyrR co-occurs with the evolutionary adaptation to lower temperatures of B. subtilis as compared to B. caldolyticus. How is this dimer/tetramer switch affected by mutations that are distant from all the inter-subunit interfaces? To answer this question, we investigated the oligomeric states during allosteric regulation by ligands in this protein family.

The allosteric regulators UMP and GMP control oligomeric state

Previous in vivo and biochemical experiments showed that the PyrR binding to the leader RNA sequence (PyrR binding loop) of the pyr operon is regulated by small molecules such as UMP and GMP (10, 11). In summary, higher concentrations of pyrimidines increase the affinity of PyrR for the PyrR binding loop, and in turn attenuate transcription of the pyrimidine synthesis operon. Higher concentrations of purines, on the other hand, decrease the affinity for the binding loop, which in turn increases the transcription of the pyrimidine synthesis operon (9) (Figure 1). As allosteric regulation usually affects conformational change, we wanted to investigate how GMP and UMP influence PyrR conformation and oligomeric state.

We analysed the oligomeric state of BsPyrR and BcPyrR by SEC-MALS upon addition of allosteric ligands, and observed that both UMP and GMP stabilize the tetrameric state of PyrR (Figures 2 and S3). This is especially prominent in the case of BsPyrR, where addition of nucleotides shifts the equilibrium towards a higher oligomeric state. The RNA-bound form of PyrR, not investigated here, is likely to be dimeric, based on analytical ultracentrifugation (11) and mutagenesis experiments (13).

This means that the effect of the eleven allosteric mutations is similar to that of RNA and opposite to the nucleotide ligands, which stabilize the tetrameric state. Interestingly, the eleven allosteric mutations are also allosteric with respect to the nucleotide-binding site: each of the eleven residues is 10 Å or more away from the bound GMP molecules.

Overall, while different ligand-bound and RNA-bound forms of the protein sample both dimeric and tetrameric states, the eleven mutations shift the free protein equilibrium towards the dimeric state in this landscape of different conformations.

Both mutations and ligands shift oligomeric state by changing inter-subunit geometry

In order to determine the structural changes that occur when the allosteric mutations switch the oligomeric state in the PyrR family, we solved four new X-ray crystal structures: AncORANGEPyrR, AncGREENPyrR, VIOLETPyrR, and BsPyrR+GMP (Table S2). We then compared these structures to those of BcPyrR and BsPyrR (22, 23).

In our previous work, we hypothesized that evolutionary changes in oligomeric state can arise from difference in inter-subunit geometry within a protein complex (5). If this were true for the PyrR family, we would expect the dimeric structures to have distinct inter-subunit geometries as compared to the tetrameric structures.

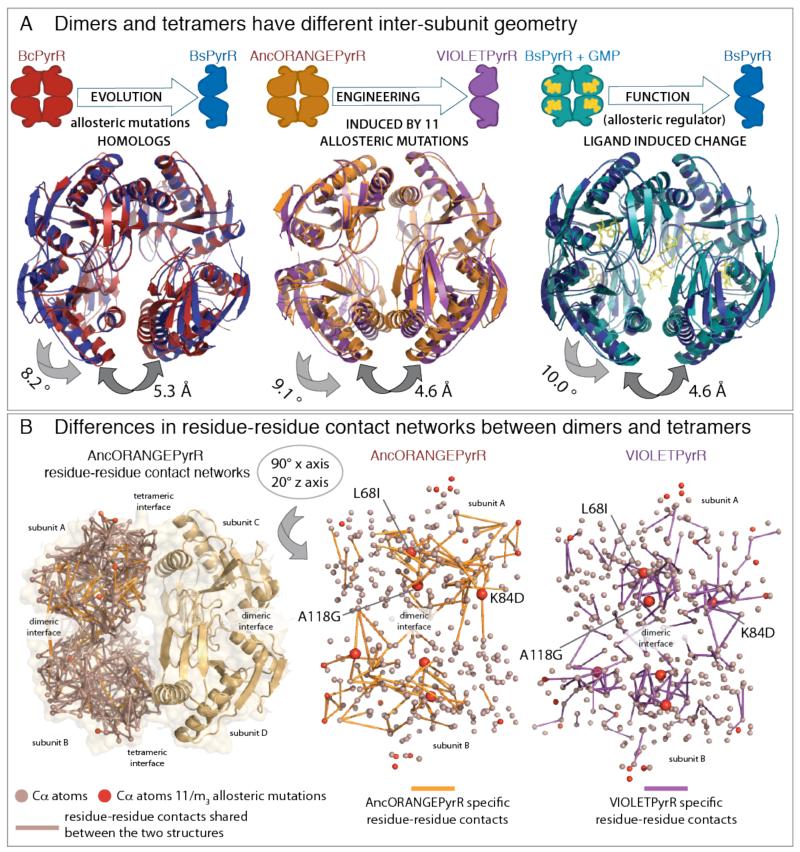

Superimposing the dimeric BsPyrR on the BcPyrR tetramer shows an 8° rotation around the dimeric interface (Figures 4A and S1). This conformation of BsPyrR is not compatible with the tetrameric oligomeric state, as the two helices that would form the dimer-of-dimers interface are pulled apart by more than 5 Å. The eleven mutations affect the same difference in conformation. Dimeric VIOLETPyrR, and tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR, which differ by the eleven mutations, exhibit the same relative rotations between subunits within the dimer (Figure 4). The subset of three allosteric mutations introduced into PLUMPyrR from AncORANGEPyrR leads to the same geometric change, where PLUMPyrR has a 9° inter-subunit rotation as compared to AncORANGEPyrR (Figure S8).

Fig. 4.

(A) Change in oligomeric state through evolutionary variation, functional allostery, or recapitulated by engineering is always coupled to the same difference in inter-subunit geometry. The three superimposed pairs of structures: (i) Bacillus subtilis PyrR (BsPyrR, pdb:1a3c) dimers superimposed on Bacillus caldolyticus PyrR (BcPyrR, pdb: 1non) tetramer; (ii) VIOLETPyrR dimers superimposed on AncORANGEPyrR tetramer; (iii) Bacillus subtilis PyrR (BsPyrR, pdb:1a3c) dimers superimposed on tetrameric Bacillus subtilis PyrR in complex with GMP. The inter-subunit geometry of free BsPyrR is incompatible with formation of the dihedral tetramer, however, GMP binding introduces a 10° inter-subunit geometric change and BsPyrR forms a tetramer. The VIOLETPyrR inter-subunit geometry is not compatible with the formation of the tetramer formed by AncORANGEpyrR, and this difference of conformation and oligomeric state is brought about by eleven allosteric mutations. (B) The tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR and dimeric VIOLETPyrR residue-residue contact networks differ by 15% of their contacts. Orientation of networks can be further explored in Supplementary Videos S1 and S2. L68I, K84D and A118G are central hubs and are involved in the majority of contact rewiring between the dimeric and tetrameric networks.

How does this compare to the difference between free, dimeric BsPyrR and tetrameric GMP-bound BsPyrR? Addition of GMP introduces a 10° rotation, changing the protein conformation into the one compatible with forming the dimer of dimers (Figure 4). The tetrameric GMP-bound BsPyrR structure is similar to the tetramers formed by free BcPyrR and AncORANGEPyrR (Figure S8). There is a subtle 3.6 ° subunit rotation around the dimeric interface between the GMP bound form of BsPyrR, and AncORANGEPyrR. However, their tetrameric interfaces superimpose almost perfectly, with an average atomic distance difference in the tetrameric interface helices of less than 1 Å.

In summary, homologous dimers all have a similar set of inter-subunit geometries, equally different from the inter-subunit geometries of tetramers. The tetramers exhibit limited variations in their geometries, all of which are significantly smaller than the differences between the dimers and tetramers. As the geometries of the dimers and tetramers are so clearly distinct from each other, we conclude that the eleven allosteric mutations affect oligomeric state in a manner almost identical to the allosteric ligand GMP.

How does this change in intersubunit geometry come about? This is not immediately evident by inspecting the individual monomeric subunits (Figure S9) or the dimeric interfaces (5) between the dimeric and tetrameric proteins, as they all superpose well. To look for the subtle structural differences that could account for the observed differences in conformation and oligomeric state, we used the residue - residue interaction network approach (24-27). With this approach, the protein structure is reduced to a network where each node represents a residue and each edge represents a physical interaction between two residues. This allows for an unbiased analysis of structures using graph theoretical methods, as illustrated in Figure S10.

The tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR and dimeric VIOLETPyrR contact networks differ in about 15% of their contacts, and these differences are non-uniformly distributed around the network (Figures 4B and S11). To estimate how much each residue contributes to the difference in residue-residue contacts, we determined the number of contact changes in two shells around the amino acid of interest. To maintain information on residue connectivity, which has been shown to determine residue evolvability (28), we used the absolute number of rewired residue contacts rather than normalizing by total number of contacts. This is because rewiring the contacts of a buried residue with a high connectivity will have a larger structural impact than rewiring a residue with lower connectivity.

Three out of the eleven allosteric mutations, L68I, K84D, and A118G, exhibit dramatic rewiring of contacts (Figure 4B). Specifically, when comparing AncORANGEPyrR with the dimeric structures (BsPyrR, VIOLETPyrR and PLUMPyrR), these residues rewire between one and two standard deviations more contacts than the average buried PyrR residue (Figure S12). L68 and A118 are completely buried in the protein interior, while K84 is in the more flexible part of the protein, changing its accessible surface area between different conformations.

Moreover, L68 and A118 are the two residues at the centre of the largest rewiring events in the transition from the dimeric BsPyrR to the tetrameric BsPyrR+GMP. This means that the structural changes due to the L68I and A118G mutations “mimic” the key residue rewiring events that occur upon GMP binding. Thus the evolutionary mutations and the allosteric ligand GMP share a common mechanism for achieving an identical inter-subunit rotation, leading to the same shift in oligomeric state.

The stability difference between PyrR tetramers is coupled to changes in the dynamics of dimeric units

Above, we observed that small differences, either via mutation or ligand binding, affect the wiring of residue contact networks. This suggests a small energy difference between the two main conformations of PyrR. Thus we might expect both these conformations to be sampled by the vibrational normal modes that describe the intrinsic dynamics of dimeric PyrR.

We compared the similarity of the intrinsic dynamics of different PyrR dimers (both the dimeric PyrRs and the halves of tetrameric PyrRs), by comparing their flexibility calculated using elastic network modeling (ENM) (29). ENM provides a distribution of fluctuations around the equilibrium conformation for each structure, and the overlap of these distributions between different structures can be described by the Bhattacharyya coefficient (BC). We have previously shown that the BC ranges between 0.85 and 1 for members of the same protein family (30). Accordingly, the differences between all PyrR proteins are in this range (between 0.83 and 0.98).

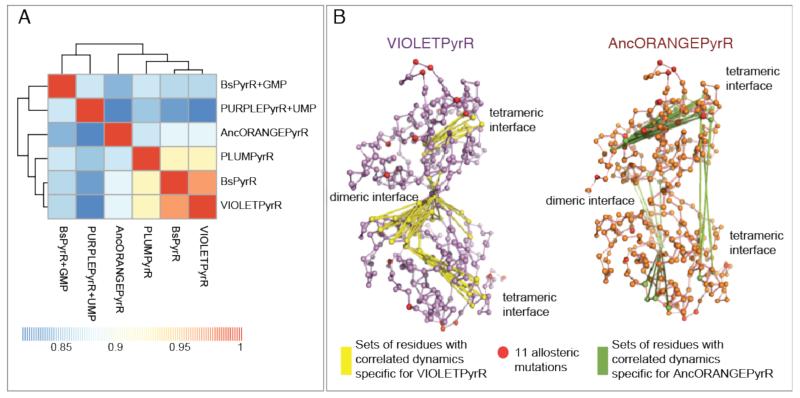

Furthermore, it is clear that the pattern of flexibility is more similar amongst the three dimers (BsPyrR, VIOLETPyrR, PLUMPyrR) than the three tetramers (AncORANGEPyrR, PURPLEPyrR+UMP, and BsPyrR+GMP) (Figure 5A). The BsPyrR dimer and BsPyrR+GMP tetramer had a similarity score of 0.87, while BsPyrR and other dimers (VIOLETPyrR and PLUMPyrR) had higher pairwise similarity scores reflecting more similar dynamics. Importantly, this illustrates that similarities in intrinsic dynamics amongst the PyrR proteins are not a simple function of sequence identity, given the fact that BsPyrR+GMP and BsPyrR have the same sequence and VIOLETPyrR is closer in sequence to AncORANGEPyrR than it is to BsPyrR. The clustering based on the BC score seen in Figure 5A matches the clustering based on their RMSD (Figure S14). While BC and RMSD compare different properties of structures, here the structures with the highest BC score also have lowest RMSD, which confirms that the structural changes are encoded in the intrinsic dynamics of these structures.

Fig. 5.

PyrR intrinsic dynamics and oligomeric state. (A) All PyrR proteins have a similar intrinsic dynamics, but the three dimeric proteins are more similar than the tetramers. This difference is most pronounced when comparing the sets of dimeric and tetrameric interface residues with correlated dynamics specific for the dimeric VIOLETPyrR or the tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR. (B) Both structures are represented by only their Cα atoms, connected by green or yellow edges if at least one of the residues is involved either in the dimeric or the tetrameric interface and only if the pair of residues is moving in a concerted, correlated manner either only in the dimeric VIOLETPyrR (yellow edges) or only in the tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR (green edges). The residues corresponding to the eleven allosteric mutations (11/m3) are coloured in red. The sets of residues with correlation differences shown here have a cluster size of more than three, and fall within the correlation difference threshold of 0.1. (Both threshold values were chosen for the sake of clarity; please see Figures S16 and S17 for a more exhaustive analysis of the correlation differences).

It has been repeatedly shown that the conformational difference, either between functional conformations or even homologues, can be sampled by a combination of a few low-frequency normal modes of the protein (31-35). We found that a few lowest frequency modes of PyrR proteins describe the transition between a tetramer and a dimer, both in the case of the transition being induced by allosteric ligands and by allosteric mutations.

In particular, the second lowest frequency mode of the BsPyrR+GMP protein also captured 44% of the transition from this tetramer to the dimeric BsPyrR structure. This mode is very similar to the three lowest frequency modes of tetrameric AncORANGEPyrR. The second lowest frequency mode of this tetramer also contributes most to the conformational change between AncORANGEPyrR and the dimeric VIOLETPyrR, which differ by just the eleven mutations (Figure S15C). For both tetramers, the transition to the dimer occurs via the low frequency normal modes that describe the same type of motions in the structure (Videos S3 – S5). This mode corresponds to the overall subunit rotation (and translation) required to go from one state to the other as described in Figure 4A.

The difference between correlations in residue motions between a dimer and a tetramer were particularly clear when comparing the correlations of dimeric and tetrameric interface residues between AncORANGEPyrR and VIOLETPyrR. In AncORANGEPyrR, the residues from the tetrameric interface exhibit correlations across the subunit and between the two tetrameric interface helices of the two subunits of a dimer, while in VIOLETPyrR the majority of the specific correlations are located close to the dimeric interface (Figures 5B and S16). Furthermore, we observed that the residues corresponding to the three out of the eleven allosteric mutations (K62P, L68I, and A118G) are within the largest regions that undergo a collective change in intrinsic dynamics from one oligomeric state to the other. The residue corresponding to the V8I mutation also experiences a notable gain in correlation in both tetramers, related to its proximity to the tetrameric interface and the overall difference seen in that region (Figure S16C). (Details of the statistical analysis of the correlated dynamics are described in the Supplementary Material and Figure S17.)

It is important to emphasize that the dynamics was calculated for the dimeric halves of the tetrameric PyrR structures. This means that the observed differences do not stem from the additional residue contacts in the tetrameric (dimer-of-dimers) interface, but are solely due to the conformational differences between the dimer and the equivalent half of the tetramer. Thus the conformational differences between different PyrR proteins are encoded in their intrinsic dynamics and, remarkably, relatively small effects, such as ligand binding or a small number of strategic mutations, can utilise these dynamics to toggle an intrinsic conformational switch and change the quaternary structure.

Conclusions

Reconstituting the PyrR sequences and analysing their biophysical properties enables us to recapitulate the evolutionary history of the family (Figure 1B). In one part of the phylogenetic tree, PyrR has adapted to remain stable and functional at extremely high temperatures (BcPyrR), while in the other part (after the AncGREENPyrR node) the organisms have adapted to life at lower temperatures (25 °C). It is known that many proteins maintain marginal stability, and one would thus expect the protein stability to reflect the differences in environmental temperatures. This can be explained by the simple fact that the selection pressure for increased stability is relaxed at mesophilic temperatures, meaning that proteins can accumulate destabilizing mutations until they reach marginal stability (4).

However, high stability can come at the expense of increased conformational rigidity, and a protein adapted to be stable at high temperatures may not be flexible enough to perform its function at a lower temperature (36). Whether it was adaptational or simply drift, in the case of PyrR, “downhill” mutations lowered thermostability, while at the same time selection for maintaining the RNA-binding site and allosteric regulation acted continuously throughout evolution. Interestingly, the accumulated “downhill” mutations caused small and cumulative changes sufficient to switch oligomeric state in the absence of mutations in the actual tetrameric interface. This change in the stability of the tetramer may have been an evolutionary by-product, demonstrating the power and importance of indirect and structurally allosteric mutations.

We have shown that the change in oligomeric state occurred through an interplay of mutations impacting residue contact networks, inter-subunit geometry, intrinsic dynamics and thermostability. At the same time, for six out of the eleven mutations, we were able to estimate their relative contributions to each of these properties (Figure 6). Interestingly, the K84D mutation, which is in the part of the structure that seems to be disordered in some of the conformations, is predicted to affect all three properties simultaneously. G172Q and K181N are mutations in surface residues, predicted to significantly contribute to the change in thermostability. L68I and A118G are mutations in buried residues at the centre of a large residue-residue rewiring event in the transition from dimer to tetramer, both in evolution and ligand binding. Both residues are also part of a region of the protein with highly correlated dynamics. K62P is a mutation in a surface residue, weakly connected to the rest of the structure, but part of a region with highly correlated motions where a change has a significant effect on protein dynamics.

Fig. 6.

Summary of mutational mechanisms. A small number of allosteric mutations are responsible for the evolutionary difference in oligomeric state, thermostability and dynamics of PyrR homologues. We show the mechanism(s) by which each mutation acts, and summarize similar mutations using the same colour.

Here we showed compellingly how mutations in residues outside the interface can introduce rearrangements that have a knock-on effect on the interface itself. We hope that the importance of mechanisms of allosteric mutations will become increasingly clear with the advancement of methods that accurately predict effects of mutations, as well as methods for engineering proteins with multiple functional conformations.

Methods

Ancestral sequence reconstruction

To reconstruct the ancestral PyrR sequences between the dimeric BsPyrR and the tetrameric BcPyrR we retrieved all the PyrR protein sequences from UniProtKB, including the sequences of two outliers: PyrR from M. tuberculosis and T. thermophilus. We used MUSCLE (37) to calculate a multiple sequence alignment of the PyrR proteins (Figure S18). We performed Bayesian inference with MrBayes version 3.1 (38). The evolutionary tree topology, branch lengths and the sequences of ancestral nodes were calculated from a PyrR protein alignment by using an estimated fixed-rate evolutionary model. The gaps in the ancestral sequences were determined using the F81-like model for binary data implemented in MrBayes (39). Please refer to the Supplementary Materials for more details.

Oligomeric state analysis by SEC-MALS

We resolved the protein samples on a Superdex S-200 10/300 analytical gel filtration column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated with 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT, at 0.5 ml/min. We performed the measurements using an online Dawn Heleos II 18 angle light scattering instrument (Wyatt Technologies Corp.) coupled to an Optilab rEX online refractive index detector (Wyatt Technologies Corp.) in a standard SEC-MALS format. We used the ASTRA v5.3.4.20 software (Wyatt Technologies Corp.) to determine the absolute molecular mass from the intercept of the Debye plot using Zimm’s model (40) and analysed the light scattering and differential refractive index. We determined the protein concentration from the excess differential refractive index based on dn/dc of 0.186 mg/ml. In order to determine the inter-detector delay volumes, band broadening constants and the detector intensity normalization constants for the instrument, we used BSA as a standard prior to sample measurement.

X- ray crystallography

All crystallisation trials were performed with 15-20 mg/ml of protein, and the sample buffer was supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2. AncPURPLE crystalised with 1.2 time excess UMP and BsPyrR with 2 time excess GMP. AncGREENPyrR and BsPyrR were additionally supplemented with 400 mM (NH4)2SO4 in order to obtain crystals. We set up 100 nl protein drop crystallisation trials with the in-house LMB screen (41). We collected the X-ray diffraction data at the Diamond Synchotron (Oxford, UK). The data were processed in the CCP4 suite (42). Please refer to Supplementary Material for details on crystallisation conditions and data processing. All the structures were solved using molecular replacement with Phaser (43), rebuilt with Coot (44), and refined with Refmac5 (45).

Structural superpositions and inter-subunit geometry comparisons

Inter-subunit geometries of all the PyrR structures (Figures 4 and S8) were compared as described previously in (5) and illustrated in Figure S1. We superimposed individual subunits using a sievefit approach, described by Arthur Lesk, and used notably in (46), and implemented more recently in the Bio3D package for R (47). With sievefit, subunits are structurally aligned using only residues that are superposable with an RMSD below 0.5 Å. These residues then define the structural core of the subunit with its corresponding centre of mass. We first sievefit only subunit A of the complex, and then re-sievefit the B subunit, noting how much the centre of mass needs to deviate from its original position (as an angle of rotation and vector of translation).

Normal mode analysis

We studied the intrinsic dynamics of all the PyrR proteins for which we had high quality structures (meaning solved to a high resolution and not having more than a few residues missing from the structure). These structures were: AncORANGEPyrR, VIOLETPyrR, PLUMPyrR, PURPLEPyrR with UMP, as well as the wild type B. subtilis PyrR with and without GMP. We performed the calculations using the Cα atom elastic network model implemented in the Molecular Modeling ToolKit (48), on the dimeric units (dimers and halves of tetramers). The GMP and UMP ligands were modelled into the B. subtilis PyrR and the PURPLEPyrR structures by placing dummy nodes at the C4′, N9, and N1 or C4′, N1, and C4 positions of the bound nucleotides in both subunits, respectively.

To compare the intrinsic dynamics of these structures, we used a structural alignment obtained from MUSTANG (49). The Bhattacharya coefficient (BC) (30, 50) was used as a measure of similarity in flexibility, with a score from 0 (completely dissimilar) to 1 (identical). Furthermore, the correlation matrices were calculated from the 100 lowest frequency modes (51). (For more details, refer to Supplementary Material.) The conformational overlap analysis of BsPyrR and BsPyrR+GMP, as well as AncORANGEPyrR with PLUMPyrR and VIOLETPyrR to obtain the modes that contribute to the transition from the tetrameric state to the dimeric state was done according to Reuter et al. (34). Here, we calculated overlaps between the modes of dimeric halves of tetramers and the structural difference vectors between the dimeric half of the tetramer and the corresponding dimer.

Thermostability

We estimated the thermostability of the PyrR proteins by measuring the circular dichroism (CD) 210-260 nm spectrum of each protein over a range of temperatures (from 20 to 90 °C). We heated the proteins gradually and continuously (0.2 °C per minute) and collected the spectrum every 5 °C. The proteins were measured at an approximate concentration of 5 μM. All the measurements were done on a Chirascan™ CD Spectrometer (AppliedPhotophysics). Mean residue ellipticity for each protein at each 5 °C temperature point was calculated as the degrees of CD corrected by exact protein concentration and the length of the protein (number of amino acids).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Prof. Robert L. Switzer (University of Illinois) for the cDNA of B. subtilis and B. caldolyticus PyrR. We thank Eviatar Natan and Dominika Gruszka for practical help, and Christine Vogel, Edvin Fuglebakk, and Nobuhiko Tokuriki for helpful discussions and insights. We thank Dr. Kiyoshi Nagai for generous access to his laboratory. We also thank Emmanuel Levy, Joseph Marsh, Roman Laskowski, Merridee Wouters and Boris Lenhard for feedback on the manuscript. YK was supported by Nakajima Foundation. XZ is supported by an Early Postdoc Mobility Fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF, Grant Number PBELP2_143538). JC is a Senior Wellcome Trust Research Fellow (grant number 095195). ST and NR are supported by Bergen Forskningsstiftelse. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, Lister Research Prize to SAT, and a Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellowship to TP.

Coordinates and structural factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (entry codes 4P80, 4P81, 4P82, 4P83, 4P84, 4P86 and 4P3K)

References

- 1.Tokuriki N, Tawfik DS. Stability effects of mutations and protein evolvability. Current opinion in structural biology. 2009 Oct;19:596. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gould SJ, Lewontin RC. The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1979 Sep 21;205:581. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaltenbach M, Tokuriki N. Dynamics and constraints of enzyme evolution. Journal of experimental zoology. Part B, Molecular and developmental evolution. 2014 Mar 13; doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taverna DM, Goldstein RA. Why are proteins marginally stable? Proteins. 2002 Feb 01;46:105. doi: 10.1002/prot.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perica T, Chothia C, Teichmann SA. Evolution of oligomeric state through geometric coupling of protein interfaces. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012 Jun 22;109:8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120028109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karplus M, Kuriyan J. Molecular dynamics and protein function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005 Jun 10;102:6679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408930102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maguid S, Fernandez-Alberti S, Parisi G, Echave J. Evolutionary conservation of protein backbone flexibility. Journal of molecular evolution. 2006 Oct;63:448. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juritz E, Palopoli N, Fornasari MS, Fernandez-Alberti S, Parisi G. Protein conformational diversity modulates sequence divergence. Molecular biology and evolution. 2013 Feb;30:79. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turnbough CL, Switzer RL. Regulation of pyrimidine biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria: repression without repressors. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2008 Jul 01;72:266. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonner ER, D’Elia JN, Billips BK, Switzer RL. Molecular recognition of pyr mRNA by the Bacillus subtilis attenuation regulatory protein PyrR. Nucleic acids research. 2001 Dec 01;29:4851. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.23.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jørgensen CM, et al. pyr RNA binding to the Bacillus caldolyticus PyrR attenuation protein. Characterization and regulation by uridine and guanosine nucleotides. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:655. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maass S, et al. Efficient, global-scale quantification of absolute protein amounts by integration of targeted mass spectrometry and two-dimensional gel-based proteomics. Analytical chemistry. 2011 May 01;83:2677. doi: 10.1021/ac1031836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savacool HK, Switzer RL. Characterization of the interaction of Bacillus subtilis PyrR with pyr mRNA by site-directed mutagenesis of the protein. Journal of bacteriology. 2002 Jun;184:2521. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.9.2521-2528.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harms MJ, Thornton JW. Analyzing protein structure and function using ancestral gene reconstruction. Current opinion in structural biology. 2010 Jul 01;20:360. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridgham JT, Ortlund EA, Thornton JW. An epistatic ratchet constrains the direction of glucocorticoid receptor evolution. Nature. 2009 Sep 24;461:515. doi: 10.1038/nature08249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong LI, Suchard MA, Bloom JD. Stability-mediated epistasis constrains the evolution of an influenza protein. eLife. 2013;2:e00631. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hobbs JK, et al. On the origin and evolution of thermophily: reconstruction of functional precambrian enzymes from ancestors of bacillus. Molecular biology and evolution. 2012 Mar 01;29:825. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinen UJ, Heinen W. Characteristics and properties of a caldo-active bacterium producing extracellular enzymes and two related strains. Archiv für Mikrobiologie. 1971 Jul 19;82:1. doi: 10.1007/BF00424925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams PD, Pollock DD, Blackburne BP, Goldstein RA. Assessing the accuracy of ancestral protein reconstruction methods. PLoS computational biology. 2006 Jul 23;2:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson-Rechavi M, Alibés A, Godzik A. Contribution of electrostatic interactions, compactness and quaternary structure to protein thermostability: lessons from structural genomics of Thermotoga maritima. Journal Of Molecular Biology. 2006 Mar 17;356:547. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuchi S, Nishikawa K. Protein surface amino acid compositions distinctively differ between thermophilic and mesophilic bacteria. Journal Of Molecular Biology. 2001 Jul 15;309:835. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chander P, et al. Structure of the nucleotide complex of PyrR, the pyr attenuation protein from Bacillus caldolyticus, suggests dual regulation by pyrimidine and purine nucleotides. Journal of bacteriology. 2005 Apr 01;187:1773. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1773-1782.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomchick DR, Turner RJ, Switzer RL, Smith JL. Adaptation of an enzyme to regulatory function: structure of Bacillus subtilis PyrR, a pyr RNA-binding attenuation protein and uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. Structure. 1998 Apr 15;6:337. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00036-7. (London, England: 1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amitai G, et al. Network analysis of protein structures identifies functional residues. Journal Of Molecular Biology. 2004 Dec 03;344:1135. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soundararajan V, Raman R, Raguram S, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Atomic interaction networks in the core of protein domains and their native folds. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013 Mar 14;494:185. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Perica T, Teichmann SA. Evolution of protein structures and interactions from the perspective of residue contact networks. Current opinion in structural biology. 2013 Jul 25; doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dellus-Gur E, Tóth-Petróczy A, Elias M, Tawfik DS. What Makes a Protein Fold Amenable to Functional Innovation? Fold Polarity and Stability Trade-offs. Journal Of Molecular Biology. 2013 Apr 28; doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinsen K, Petrescu AJ, Dellerue S, Bellissent-Funel MC, Kneller GR. Harmonicity in slow protein dynamics. Chemical Physics. 2000;261:25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuglebakk E, Echave J, Reuter N. Measuring and comparing structural fluctuation patterns in large protein datasets. Bioinformatics. 2012 Oct 01;28:2431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts445. (Oxford, England) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Echave J. Evolutionary divergence of protein structure: The linearly forced elastic network model. Chemical Physics Letters. 2008;457:413. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leo-Macias A, Lopez-Romero P, Lupyan D, Zerbino D, Ortiz AR. An analysis of core deformations in protein superfamilies. Biophysical journal. 2005 Mar 01;88:1291. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raimondi F, Orozco M, Fanelli F. Deciphering the deformation modes associated with function retention and specialization in members of the Ras superfamily. Structure. 2010 Apr 10;18:402. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.015. (London, England: 1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuter N, Hinsen K, Lacapère J-J. Transconformations of the SERCA1 Ca-ATPase: a normal mode study. Biophysical journal. 2003 Oct;85:2186. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74644-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tama F, Sanejouand YH. Conformational change of proteins arising from normal mode calculations. Protein engineering. 2001;14:1. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Závodszky P, Kardos J, Svingor, Petsko GA. Adjustment of conformational flexibility is a key event in the thermal adaptation of proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998 Jul 23;95:7406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:1792. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003 Aug 12;19:1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. (Oxford, England) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. Journal of molecular evolution. 1981;17:368. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimm BH. The Scattering of Light and the Radial Distribution Function of High Polymer Solutions. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1948 Dec;16:1093. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stock D, Perisic O, Löwe J. Robotic nanolitre protein crystallisation at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology. 2005 Jul;88:311. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011 May;67:235. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007 Aug 01;40:658. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004 Dec;60:2126. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011 May;67:355. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerstein M, Chothia C. Analysis of protein loop closure. Two types of hinges produce one motion in lactate dehydrogenase. Journal Of Molecular Biology. 1991 Jul 05;220:133. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90387-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant BJ, Rodrigues APC, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, Caves LSD. Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2006 Nov 01;22:2695. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461. (Oxford, England) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinsen K. The molecular modeling toolkit: A new approach to molecular simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2000 Feb 30;21:79. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konagurthu AS, Whisstock JC, Stuckey PJ, Lesk AM. MUSTANG: a multiple structural alignment algorithm. Proteins. 2006 Aug 15;64:559. doi: 10.1002/prot.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuglebakk E, Reuter N, Hinsen K. Evaluation of Protein Elastic Network Models Based on an Analysis of Collective Motions. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2013 Dec 10;9:5618. doi: 10.1021/ct400399x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichiye T, Karplus M. Collective motions in proteins: A covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins. 1991 Nov;11:205. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.