Abstract

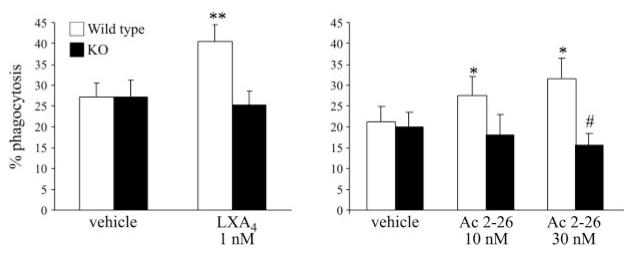

Lipoxins (LXs) are endogenously produced eicosanoids with well-described anti-inflammatory and proresolution activities, stimulating nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages. LXA4 and the glucocorticoid-derived annexin A1 peptide (Ac2–26) bind to a common G-protein-coupled receptor, termed FPR2/ALX. However, direct evidence of the involvement of FPR2/ALX in the anti-inflammatory and proresolution activity of LXA4 is still to be investigated. Here we describe FPR2/ ALX trafficking in response to LXA4 and Ac2–26 stimulation. We have transfected cells with HA-tagged FPR2/ALX and studied receptor trafficking in unstimulated, LXA4 (1–10 nM)- and Ac2–26 (30 μM)-treated cells using multiple approaches that include immunofluorescent confocal microscopy, immunogold labeling of cryosections, and ELISA and investigated receptor trafficking in agonist-stimulated phagocytosis. We conclude that PKC-dependent internalization of FPR2/ALX is required for phagocytosis. Using bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from mice in which the FPR2/ALX ortholog Fpr2 had been deleted, we observed the nonredundant function for this receptor in LXA4 and Ac2–26 stimulated phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. LXA4 stimulated phagocytosis 1.7-fold above basal (P<0.001) by BMDMs from wild-type mice, whereas no effect was found on BMDMs from Fpr2−/− mice. Similarly, Ac2–26 stimulates phagocytosis by BMDMs from wild-type mice 1.5-fold above basal (P<0.05). However, Ac2–26 failed to stimulate phagocytosis by BMDMs isolated from Fpr2−/− mice relative to vehicle. These data reveal novel and complex mechanisms of the FPR2/ALX receptor trafficking and functionality in the resolution of inflammation.

Keywords: resolution, inflammation

Lipoxins (LXs) are endogenously produced eicosanoids with well-described anti-inflammatory and proresolution activities (1–8). LXA4 and its positional isomer LXB4 are the principal LXs formed by transcellular metabolism in mammalian systems (1, 7, 8). The role for LXs as anti-inflammatory molecules include the inhibition of neutrophil and eosinophil recruitment and activation (9–14). In addition, LXA4 actively promotes the resolution of the inflammatory response, a feature also associated with the more recently described proresolving lipid mediators such as resolvins, protectins, and maresins (7, 15, 16). The resolution of inflammation includes the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic leukocytes from an inflammatory site by processes coupled to the release of specific mediators that are associated with a reparative phenotype (17, 18). LXs stimulate the nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages in vitro and in vivo (19–21) with a mechanism mediated by protein kinase C (PKC) and PI-3-kinase (19, 20). Furthermore, LXs prime macrophages for chemotaxis and phagocytosis, through myosin IIa assembly, reorganization of the cytoskeleton, promotion of cell polarization, and formation of actin filaments and pseudopodia (21, 22). Assembly of non-muscle myosin is coupled to serine dephosphorylation, a process stimulated by LXA4 by a mechanism likely to involve phosphatase activation (21, 23).

Several targets for LXA4 actions have been proposed; preeminent among these are members of the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. FPRs are a small group of 7-transmembrane domain, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) with an important role in host defense and inflammation (24, 25). There are three human FPRs; according to recent nomenclature, these are defined as FPR1, FPR2/ALX, and FPR3 (25). LXA4 was the first identified endogenous ligand for FPR2/ALX (26). The FPR2/ALX has been shown to bind endogenous and exogenous lipid and protein ligands (25), eliciting either proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory responses, indicating that FPR2/ALX can serve as a stereoselective yet multirecognition receptor in immune responses (24, 25, 27). Among the various ligands, one of particular interest is annexin A1, a glucocorticoid-inducible protein, and its N-terminal peptides (i.e., Ac2–26) that mediate many of the anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids in models of acute and chronic inflammation (28–31). Interestingly, annexin A1 and Ac2–26 promote phagocytosis of apoptotic cells with mechanisms similar to those observed for LXA4, (32, 33).

LXs have been shown to inhibit polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) chemotaxis, whereas they activate monocyte chemotaxis. In addition, LXs have been demonstrated to induce changes in the ultrastructure and actin reorganization in human monocytes and macrophages, but not in PMNs (22), which suggests the involvement of a possible different receptor such as FPR3.

Current understanding of the intracellular signaling pathways triggered on FPR2/ALX engagement remains incomplete. Accumulating evidence indicates that the binding of lipids and small peptides to the receptor occurs with different affinities and/or at discrete interaction sites, facilitating activation of different second messengers and downstream signaling pathways (24, 34, 35). However, evidence of the involvement of FPR2/ALX in the anti-inflammatory and proresolution activity of LXA4 is related only to in vitro studies that use a peptide antagonist for both FPR1 and FPR2/ALX, as no specific antagonists of FPR2/ALX or neutralizing antibodies are available (32, 36, 37). Given the primary importance of the role of LXs in the resolution of inflammation, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms that regulate the LX-receptor interaction and function. Recently, a novel mouse line in which the murine gene for Fpr2, the murine homologue of FPR2/ALX receptor, was generated (38), which gives an important tool to study the role of this receptor in the resolution of inflammation.

In the present study, we have defined the dynamics of the intracellular trafficking processes of FPR2/ALX on stimulation with LXA4 and Ac2–26. We show that FPR2/ALX receptor internalization is critical for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Furthermore, using macrophages from mice nullified for Fpr2, the murine ortholog of FPR2/ALX, we demonstrated unequivocally the functional link between activation of this specific GPCR and clearance of apoptotic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All cell culture reagents and secondary fluorescent antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA) LXA4 [5(S)-6(R)-15(S)-trihydroxy-7,9,13-trans-11-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid] was obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). The annexin A1 mimetic peptide Ac2–26 (acetyl-AMVSEFLKQAWFIEN EEQEYVQTV) was synthesized by Cambridge Bioscience (Cambridge, UK). HA-tagged FPR2/ALX or FPR3 (3xHA) were obtained from the Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (http://www.cdna.org). FuGENE 6 was from Roche Applied Science (Penzberg, Germany). PMA, wortmannin, and genistein were purchased from Sigma (Dublin, Ireland). The specific PKC inhibitor Bis1 (GF109203X) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-Ha antibody was obtained from Covance (Berkeley, CA, USA). Secondary gold-conjugated antibody was obtained from BBInternational (Cardiff, UK). Reagents were dissolved in DMSO or ethanol and further diluted in medium (final concentration, 0.1%). Equivalent concentrations of DMSO or ethanol were used as vehicle controls.

Cell culture

Hela cells were maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. THP-1 cells (leukemic, monocytic cell line) were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Salisbury, UK) and cultured as described previously (33, 37). THP-1 cells were differentiated to a macrophage-like phenotype by treatment with 10 nM PMA for 48 h at 37°C (33, 37).

Human PMNs were isolated from peripheral venous blood drawn from healthy volunteers, after informed written consent, as described previously (19, 32). Briefly, PMNs were separated by centrifugation on Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) followed by dextran sedimentation (Dextran T500; Pharmacia) and hypotonic lysis of red cells. PMNs were suspended at 4 × 106 cells/ml, and spontaneous apoptosis was achieved by culturing PMNs in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% autologous serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin for 20 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were on average 25–50% apoptotic with ~3% necrosis as assessed by light microscopy on stained cytocentrifuged preparations (19).

Cell transfection

Hela cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged FPR2/ALX or FPR3 using FuGENE 6 according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, Hela cells were grown to 60–75% confluence overnight in 60-mm plates, transfected with 4 μg of total DNA. At 24 h after transfection, Hela cells were transferred in 12- or 24-well plates onto poly-l-lysine (Sigma)-coated coverslips and allowed to attach overnight.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Hela cells were treated with vehicle (ethanol), LXA4, or Ac2–26 for the indicated times at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for another 30 min. Cells were incubated with the anti-HA antibody for 1 h at room temperature, washed in PBS, and incubated with the appropriate fluorescent secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Following counterstaining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylin-dole (DAPI; Sigma; 1 μg/ml, in H2O), coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Probing Antifade medium (Invitrogen). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 META scanning confocal microscope (×63 oil-immersion objectives) and analyzed by Zeiss LSM Imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

To evaluate the constitutive internalization of the receptor, Hela cells transiently expressing FPR2/ALX or FPR3 were prelabeled with anti-HA antibody for 1 h at 4°C. Under these conditions, only receptors present on the cell surface bind antibody (39). Cells were then washed and incubated in the absence or presence of LXA4 (1 nM) for 30 min at 37°C. After fixation with paraformaldehyde, the cells were stained with Oregon Green anti-mouse secondary antibody and visualized by the confocal microscope.

To determine the intracellular origin (recycling vs. newly synthesized receptors) of the receptors observed at the plasma membrane after internalization, the experiments were performed after pretreating the cells for a period of 4 h with cycloheximide at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml in serum-free medium. Cycloheximide at the same final concentration was then maintained for the duration of the experiment.

Electron microscopy

Cells for cryosectioning were grown in 60-mm tissue culture dishes. Transfected and nontransfected cells (negative control) were treated with vehicle or LXA4 (1 nM) for appropriate times. Cells were fixed for 45 min with 3.8% paraformaldehyde + 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), embedded in 10% gelatin in PB, and cryoprotected by infusion with 2.3 M sucrose in PB. Cryosections of 60 nm were obtained using a Leica EM FC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and picked up onto formvar/carbon-coated copper grids. Immunolabeling was performed according to Tokuyasu (40, 41). Briefly, sections were incubated with anti-HA antibody (1:400 dilution), followed by an anti-mouse 10-nm gold-conjugated antibody (1:40 dilution). Finally, sections were contrasted by incubation in 0.44% uranyl acetate in methyl cellulose. Sections were examined in a Tecnai 12 BioTwin transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) using an acceleration voltage of 120 kV and objective aperture of 20 μm. Digital images were recorded with a MegaView III camera (SIS, Münster, Germany).

Quantification of FPR2/ALX receptor internalization

Agonist-induced changes in cell surface receptor distribution were measured by ELISA. At 24 h after transfection with HA-FPR2/ALX, 2 × 105 cells were transferred to 24-well plates precoated with 0.1 mg/ml poly-l-lysine. On the following day, cells were washed with serum-free MEM and incubated with the appropriate stimuli. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed 3 times with PBS, and nonspecific binding was blocked for 45 min with 1% BSA in PBS. Cells were incubated with anti-HA specific antibody for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, and blocked again in PBS/BSA for 15 min prior to incubation with secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. A colorimetric alkaline phosphatase substrate (p-nitrophenyl-phosphate) was added, and plates were incubated at 37°C until adequate color development was visible. Reaction was stopped with 3 N NaOH, and the sample absorbance was read at 405 nm using a microplate reader. Nontransfected cells were studied concurrently to determine background. Results are shown as percentage of cell surface receptor loss, defined as percentage of internalization.

Agonist-induced redistribution of FPR2/ALX in human PMNs and in FPR2/ALX transfectants was investigated by FACS. Isolated human PMNs or HEK cells transfected with the FPR2 receptor (42) were seeded on 24-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml and incubated with vehicle, 10 μM of Ac2–26 or 1 nM LXA4, for the following time points: 15, 30, and 60 min. At the end of each point, further receptor movement was inhibited by using a metabolic inhibitor cocktail composed of 1 mM 2–4 dinitrophenol and 45 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose as described previously (43). PMNs or HEK cells were incubated with the metabolic inhibitor cocktail for 10 min, then washed twice with PBC (PBS+0.15% BSA) and seeded at a concentration of ~1 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well plate. Following incubation (40 min at 4°C) with a mouse monoclonal anti-human FPR2 antibody (clone: 6C7-3; kind gift of Dr. D Anderson, Astra Zeneca, Macclesfield, UK) or an isotype control (Serotec, Oxford, UK), cells were washed twice with PBC and incubated for another 30 min at 4°C with an anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (clone: Star 9B; Serotec). At least 10,000 events were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Surface protein expression was recorded as MFI units measured in the FL1 green channel.

Isolation of bone-marrow derived macrophages from wild-type and Fpr2−/− mice

Bone marrow macrophages were obtained from femurs and tibiae of 4–6 wk-old WT littermate controls and Fpr2−/− mice, as recently described (38). Briefly, the bone marrow was flushed from the bone with complete medium through a 25-gauge needle to form a single-cell suspension. Cells were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, 20% FCS, and L929 conditioned medium as a source of macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and cultured at 37°C. At d 5, the cells were harvested and seeded on 24-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/well.

Phagocytosis assay

Differentiated THP-1 cells (5×105 cells/well) or BMDMs isolated from wild-type and Fpr2−/− mice were exposed to the appropriate stimuli as indicated for 15 min at 37°C, before coincubation with apoptotic PMNs (1×106 PMNs/well) at 37°C for 2 h or 30 min, respectively. Noningested cells were removed by 3 washes with cold PBS. Phagocytosis was assayed by myeloperoxidase staining of cocultures fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. For each experiment, the number of THP-1 or BMDMs containing 1 or more PMNs in ≥5 fields (minimum of 400 cells) was expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells, and an average between duplicate wells was calculated.

Fluorescent-labeled zymosan (Invitrogen) was opsonized with the appropriate opsonizing reagent, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Differentiated THP-1 cells were exposed to the indicated stimuli before particles were added at a 5:1 ratio. After 2 h incubation, phagocytosis was quantified as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired Student’s t test, with P < 0.05 for n independent samples being deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

Internalization of FPR2/ALX: confocal studies

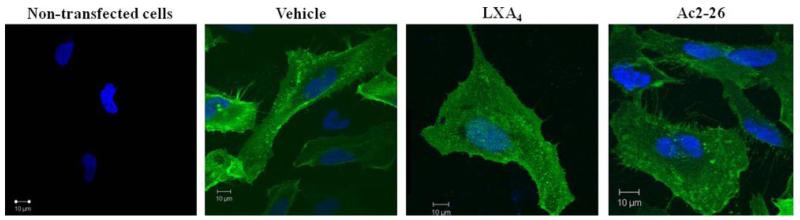

We investigated the internalization of transiently expressed FPR2/ALX receptor in response to LXA4 (1 nM) and Ac2–26 peptide (30 μM), well-described agonists of the receptor with anti-inflammatory and proresolution activity (7, 24, 25, 29, 31, 44). In unstimulated cells, FPR2/ALX was visualized primarily at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1A). On stimulation with LXA4 (15 min), the receptors were clustered on the membrane, and the increased receptor was visualized within the cytoplasmic compartment (Fig. 1B). Similarly, on treatment with Ac2–26, confocal images showed a loss of the receptor from the cell surface and trafficking inside the cell (Fig. 1C). These concentrations of agonists were chosen on the basis of previous data demonstrating Kd values for LXA4 of ~0.5–1 nM (26, 45) and 1.2 μM for Ac2–26 (31), and functional studies showing the efficacy of these concentrations in stimulating phagocytosis (19, 21, 32). We have also seen internalization of the endogenously expressed FPR2/ALX in LXA4-stimulated monocyte-derived macrophages (5).

Figure 1.

LXA4- and Ac2–26-induced internalization of FPR2/ALX: confocal microscopy. Hela cells transiently expressing HA-tagged FPR2/ALX plated on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips were treated with vehicle (EtOH), LXA4 (1 nM), or Ac2–26 (30 μM) for 15 min. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and subjected to detection of receptor using an anti-HA primary antibody, followed by a Oregon Green-conjugated secondary antibody. Confocal microscopy images representative of ≥5 experiments are shown. Image of untransfected cells is shown as negative control.

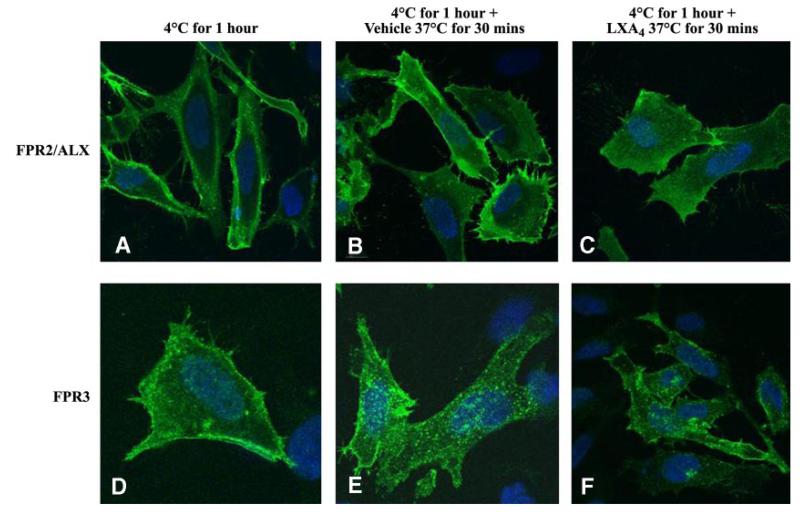

This agonist-dependent internalization of the FPR2/ALX contrasts with the constitutive internalization of the FPR3 receptor. Hela cells transiently expressing the HA-tagged receptors were incubated with the HA antibody at 4°C for 1 h before incubation at 37°C in the absence or presence of agonist, so that only the trafficking of the receptors initially present on the cell surface would be monitored (39). After agonist treatment, cells were permeabilized and the HA-epitope was visualized with fluorescent secondary antibody. After 1 h incubation at 4°C, the anti HA antibody was visualized at the cell membrane level (Fig. 2A for FPR2/ALX and Fig. 2D for FPR3). As shown in Fig. 2B, after treatment of cells with vehicle, FPR2/ALX is localized almost exclusively on the cell membrane, whereas the FPR3 receptor shows punctuate intracellular localization (Fig. 2E), which suggests that the FPR3 receptor undergoes constitutive internalization even in the absence of LXA4. On stimulation with LXA4 (1 nM for 30 min), distribution of the FPR2/ALX receptor is detected in punctuate, intracellular pattern (Fig. 2C). Agonist-induced internalization of the FPR3 receptor was difficult to assess because of the constitutive internalization, and treatment with LXA4 did not appear to produce changes in receptor localization (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Constitutive and agonist-dependent internalization of FPR2/ALX and FPR3. Hela cells transiently transfected with HA-tagged FPR2/ALX (A–C) or FPR3 (D–F) were labeled at 4°C for 1 h with anti HA primary antibody prior to incubate the cells at 37°C in the presence of vehicle (EtOh) or LXA4 (1 nM) for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde and receptor was stained with Oregon Green anti-mouse secondary antibody. Confocal microscopy images were acquired with an ×65 oil lens. Data are representative of ≥3 different experiments.

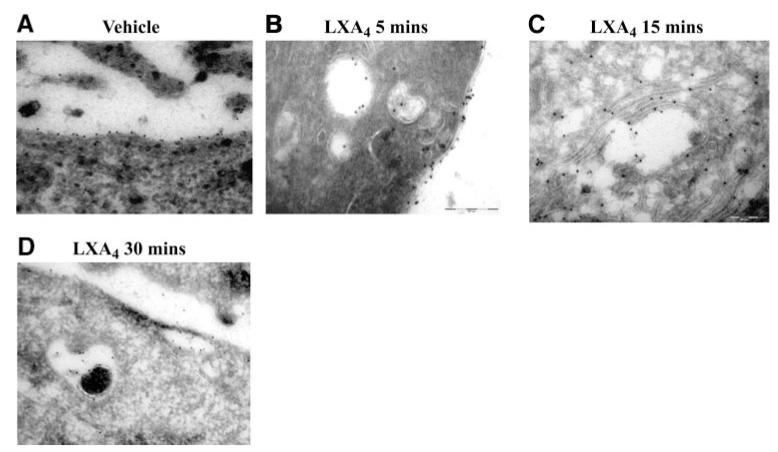

Internalization of FPR2/ALX: electron microscopy study

Cells transiently expressing FPR2/ALX were exposed to vehicle or to LXA4 (1 nM) for 5, 15, and 30 min. By transmission electron microscopy with cryosectioning, the receptor is identified exclusively on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in unstimulated cells (Fig. 3A). After 5 min of stimulation with LXA4, the receptor is present on both the inner and outer leaflets of the plasma membrane and, importantly, also in the early endosomes (Fig. 3B). After 15 min of the exposure to LXA4, the receptor is prominent in the tubercular region of the midlate endosome system (Fig. 3C), and finally after 30 min appears to be colocalized in late endosome and lysosome compartments (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Cryosectioning and immunogold labeling of FPR2/ALX. Hela cells transiently transfected with HA-tagged FPRL1/ALX were treated with vehicle (EtOH; A) or LXA4 (1 nM) for 5 min (B), 15 min (C), and 30 min (D). Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde and cryosectioned (60-nm sections). Sections were incubated with anti-HA antibody, followed by an anti-mouse 10-nm gold-conjugated antibody, and contrasted by incubation in uranyl acetate in methyl cellulose. View: ×65,000 (A, D); ×100,000 (B, C).

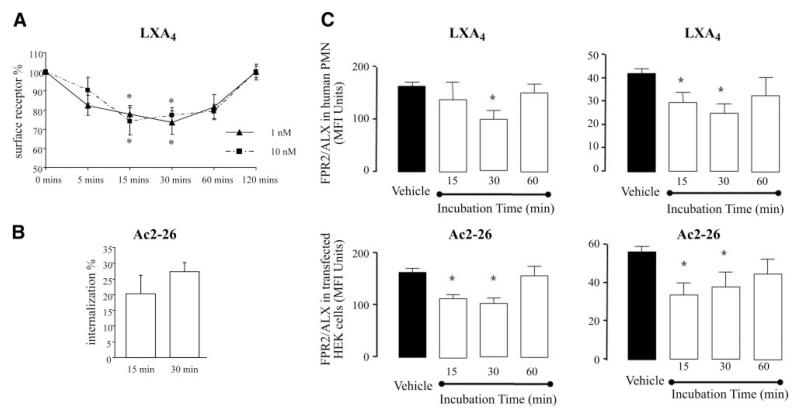

Quantitation of FPR2/ALX receptor internalization

We used an ELISA-based internalization assay to quantify the changes in the cell surface expression of HA-tagged FPR2/ALX in response to LXA4 and Ac2–26. The cells were exposed to LXA4 (1 nM) for times ranging from 0 to 60 min, and the amount of surface HA antigen was determined at each point. As shown in Fig. 4A, the receptor underwent a rapid internalization within the first 5 min, reaching a plateau within 15–30 min. After 120 min, the level of the receptor at the cell membrane was equivalent to that at basal level. The time course for LX-induced sequestration of the receptor was similar when a higher concentration of agonist (10 nM) was used. When cells were stimulated with Ac2–26, 25% of the receptor internalization was observed 30 min after stimulation (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Quantification of LXA4- and Ac2–26-induced internalization of FPR2/ALX by ELISA and FACS. A, B) Hela cells transiently expressing HA-tagged FPR2/ALX were stimulated for the indicated times with 1 nM LXA4 (A) or 30 μM Ac2–26 (B). The loss of cell surface HA expression, index of receptor internalization, was measured by ELISA, as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent means ±se; n = 4–6 *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle. C) Isolated human PMNs or HEK cells transfected with the FPR2 receptor were incubated with vehicle, 10 μM Ac2–26, or 1 nM LXA4 for the indicated times. At the end of each point, further receptor movement was inhibited. Following incubation with a mouse monoclonal anti-human FPR2 antibody or an isotype, control cells were washed and incubated for a further 30 min at 4°C with an anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. At least 10,000 events were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest software. Surface protein expression was recorded as MFI units measured in the FL1 green channel. Data are means ± se from ≥4 independent experiments for both PMNs and HEK cells.

To determine the intracellular origin (recycling vs. newly synthesized) of the receptors quantified at the plasma membrane after internalization, experiments were performed with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. The reappearance of the receptor on the plasma membrane after 30 and 60 min treatment with LXA4 was not significantly affected by cycloheximide (data not shown), which suggests that the receptor is trafficking from the intracellular space to plasma membrane, without involvement of de novo protein synthesis. A similar rate of internalization was observed when HEK293 cells stably transfected with HA-tagged FPR2/ALX were used, LXA4 producing 36.7 ± 5.2% internalization (15-min time point) (P<0.05 vs. vehicle; n=3).

Using FACS analysis, we investigated surface distribution of endogenous FPR2/ALX in human PMNs. We report that both LXA4 and Ac2–26 induced a loss of cell surface receptor detectable at 15 and 30 min, with an almost complete restoration detected at 60 min (Fig. 4C). These data were derived from PMN preparations from ≥4 individual donors. In FPR2/ALX transfected HEK cells, LXA4 and Ac2–26 produced a similar degree (~30–40%) of receptor internalization (Fig. 4C).

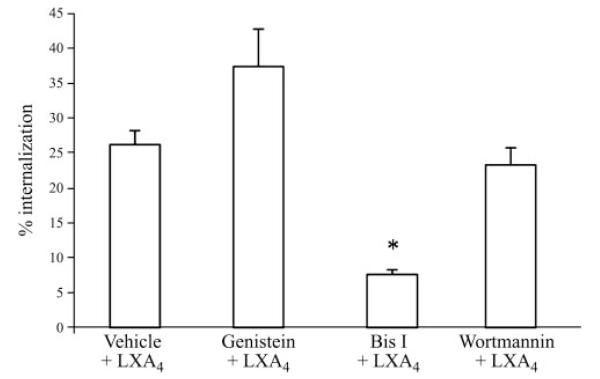

Involvement of PKC in the LXA4-induced internalization of FPR2/ALX

Previously, we reported a role for PKC in the mechanism of LX-stimulated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages (20), which suggests the involvement of PKC in LXA4-induced postreceptor signaling. To investigate whether PKC activity or other kinases were required for FPR2/ALX internalization, the effect of protein kinase inhibitors was tested using the ELISA protocol for quantification. None of the kinase inhibitors significantly altered cell surface receptor expression in unstimulated cells. Treatment of the cells with wortmannin or genistein failed to affect the magnitude of receptor internalization, which indicates a lack of involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase or tyrosine kinases, respectively, in regulating FPR2/ALX internalization (Fig. 5). A slight increase of the receptor internalization was observed when genistein was used; however, it was not statistically significant. On the contrary, the specific PKC inhibitor Bis1 (GF109203X) caused a significant inhibition of receptor internalization (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Protein kinase C is involved in the LXA4-induced internalization of FPR2/ALX. Hela cells transiently expressing HA-tagged FPR2/ALX were pretreated for 30 min with vehicle (Veh), BisI (10 μM), wortmannin (100 nM), or genistein (100 μM), and then stimulated with LXA4 (1 nM) for 15 min, and loss of cell surface receptors was assessed by ELISA (n=3). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

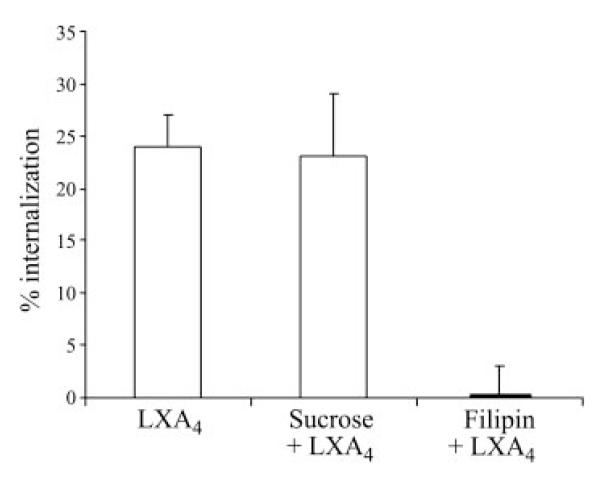

Effect of inhibitors of lipid rafts on LXA4-induced internalization of FPR2/ALX and LXA4-induced phagocytosis

Two principal pathways have been described for the internalization of GPCRs. One pathway uses clathrincoated pits and can be inhibited by pretreatment of the cells with sucrose. The second pathway depends on the formation of caveolae.

Here we demonstrate that cholesterol depletion from the plasma membrane with filipin, which disrupts caveolae and lipid rafts, completely inhibited LXA4-induced sequestration of the receptor. However, blocking the formation of clathrincoated vesicles by hyperosmotic sucrose pretreatment was without effect (Fig. 6). These data provide evidence that FPR2/ALX is internalized on LXA4 stimulation via a clathrin-independent mechanism and most likely involving lipid rafts. These data are consistent with previous reports in which we described association of FPR2/ALX with caveolae-enriched fractions in HEK293 cells stably transfected with the receptor (23).

Figure 6.

Disruption of lipid raft affected FPR2/ALX internalization. Hela cells transiently expressing HA-tagged FPR2/ALX were pretreated with sucrose (0.45 M) or filipin (5 μg/ml) for 30 min prior to treatment with LXA4 (1 nM) for 15 min. Loss of cell surface receptors was assessed by ELISA (n=3).

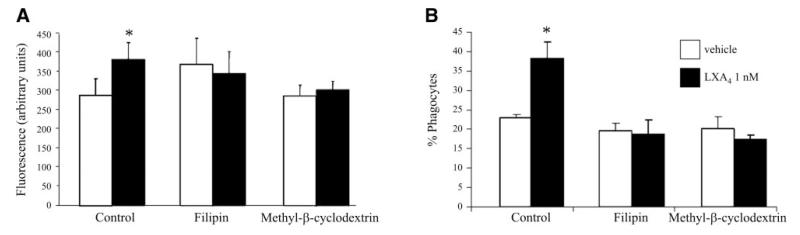

The functional significance of FPR2/ALX internalization to phagocytosis was investigated. LXA4 stimulated uptake of zymosan particles by differentiated THP-1 and was inhibited after disruption of lipid raft with filipin or methyl-cyclodextrin (Fig. 7A). More significantly, perturbation of lipid raft affected the ability of LXA4 to stimulate phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs by differentiated THP-1 (Fig. 7B), highlighting a correlation between FPR2/ALX trafficking and LXA4 functional responses in promoting the resolution of inflammation.

Figure 7.

Disruption of lipid raft affected LXA4-induced phagocytosis. Differentiated THP-1 cells were pretreated with filipin (5 μg/ml) for or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (10 mM) prior treatment with vehicle (EtOH) or LXA4 (1 nM) for 15 min. A) Opsonized fluorescent zymosan was added (ratio 1:5), and phagocytosis was allowed to proceed for 2 h. Internalized fluorescence associated with internalized zymosan was measured with a fluorescence plate reader. B) Apoptotic PMNs were added, and phagocytosis was allowed to proceed for 2 h. Phagocytosis was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as mean ± se percentage of phagocytosis (n=4). * P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages from Fpr2−/− mice show defective phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs

To directly address the requirement of FPR2/ALX for LXA4 and Ac2–26 stimulated phagocytosis, we used BMDMs isolated from WT or Fpr2−/− mice. BMDMs were exposed to vehicle, LXA4 (1 nM), or Ac2–26 (10–30 μM) before incubation with apoptotic PMNs. In basal condition, no difference was found in the percentage of phagocytosis between the experimental groups. As expected, LXA4 and Ac2–26 stimulated a significant increase in phagocytosis by BMDMs isolated from wild-type mice, confirming our previous data (20). However, both agonists failed to increase phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs by BMDMs isolated from Fpr2−/− mice (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

BMDMs from Fpr2−/− mice show defective phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs. BMDMs isolated from WT or Fpr2−/− mice were exposed to vehicle, LXA4 (1 nM) or Ac2–26 (10–30 μM) before incubation with human apoptotic PMNs. Phagocytosis was allowed to proceed for 30 min. Phagocytosis was quantified my microscopy after staining for myeloperoxidase as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as mean ± se percentage of phagocytosis (n=4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

DISCUSSION

Resolution of inflammation is an active process regulated by a recently described genus of mediators with anti-inflammatory and proresolving actions (6–8). An important role in this context is played by LXA4 and annexin A1, which exert their anti-inflammatory actions through a common GPCR, the FPR2/ALX. This receptor belongs to the FPR family, including also FPR1 and FPR3, whose members share significant sequence homology and are encoded by clustered genes (25). FPRs are expressed mainly by mammalian phagocytic leukocytes and are known to be important in host defense and inflammation. Accumulating evidence indicates that FPR2/ALX signaling is cell and agonist specific, activating different second messengers and downstream signaling pathways. FPR3 is not found in neutrophils. It is detected together with transcripts for FPR1 and FPR2/ALX in monocytes, although the expression pattern changes with monocyte differentiation (25). Because LXA4 shows inhibitory effects on PMN function but activate monocyte chemotaxis, it was suggested that FPR3 might regulate LX responses in macrophages.

LXA4 actively promotes the resolution of the inflammatory response, increasing phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages (19, 20), a feature also associated with other proresolving lipid mediators such as resolvins (16, 46). Resolvin D1 interacts with FPR2/ALX, and with an orphan receptor GPR32, suggesting that this receptor may be part of a cluster of receptors transducing proresolution signals with lipid mediators (16).

No specific antagonists or neutralizing antibodies for FPR2/ALX have been found, therefore evidence of the involvement of FPR2/ALX in the anti-inflammatory and proresolution activity of LXA4 is only related to in vitro studies using nonspecific peptide antagonists for the receptor. Given the primary importance of the role of LXs in the resolution of inflammation, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms that regulate the LX-receptor interaction and function. In this study we have established that LXA4 and Ac2–26 activation of the FPR2/ALX is critical for stimulating phagocytosis of apoptotic leukocytes.

We have defined, for the first time, the dynamics of the intracellular trafficking processes of FPR2/ALX on stimulation with LXA4 and Ac2–26 in cells transfected with HA-tagged FPR2/ALX plasmid. Confocal microscopy showed that under basal conditions, distribution of the FPR2/ALX on the cell membrane is diffuse. Stimulation with LXA4 induced a time-dependent internalization of the receptor from the plasma membrane to the intracellular space; the fraction of the receptor still present on the plasma membrane showed a focally punctuate distribution. ELISA quantitation studies showed that ≤30% of the receptor is internalized. In agreement with this, ultrastructural observations showed that the receptor is predominantly sited on the external leaflet of the plasma membrane in a diffuse pattern. Following stimulation with LXA4, a diminution of plasma membrane-bound signal, clustering of gold particles, and concomitant detection of FPR2/ALX in the cytoplasm was found. We have shown previously that in human-derived macrophages, FPR2/ALX after stimulation with LXA4 is distributed within the cytosol in a manner similar to the HA-tagged receptor (5).

Because of the difference of the activity of LXA4 between neutrophils and macrophages, it has been suggested that LXA4 may also bind to FPR3. Interestingly, we did not observe any agonist stimulated trafficking of FPR3. The FPR3 receptor was found predominantly within the intracellular compartments irrespective of ligand stimulation.

Cells use various internalization pathways to control cell-surface receptors, and this is crucial for regulating cell signaling, receptor turnover, and the magnitude, duration, and nature of signaling events. Clathrin and caveola/lipid raft mediated endocytosis remain the best characterized mechanisms of ligand-receptor internalization.

Here we demonstrate that internalization of FPR2/ALX is inhibited by pretreatment with filipin, which causes disassembly of cholesterol-rich rafts and caveolae, but not by pretreatment with sucrose, which interferes with clathrin. These data support our previous observation that the receptor colocalizes with caveolin-1 and flotillin-1 but not clathrin (23). In that study, we have also shown that dephosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase platelet-derived growth factor receptor by activation of SHP-2 in renal mesangial cells depends on the internalization of the ALX into a cholesterol enriched microdomain (23). Interestingly, here we demonstrate that disruption of lipid raft inhibits LXA4-induced phagocytosis of opsonized zymosan by differentiated THP-1, indicating the requirement of the internalization of FPRL1/ALXR in the mechanism of LXA4. Notably, we observe that that phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages requires receptor internalization.

LXA4 induces phagocytosis of apoptotic cells through actin rearrangement and polarization of macrophages, promoting serine dephosphorylation of the non-muscle myosin-II a isoforms (MYH9) and altering phosphorylation/activation of key components of cell polarization and phagocytosis (21, 22). MYH9 plays a key role also in the complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis to facilitate the formation of actin cup assembly (47). The association of FPR2/ALX in the lipid raft compartment could play a role in the assembly of actin and formation of phagosome; however, this hypothesis needs further investigation. The effect of LXs on phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs by macrophages can be blocked by antibodies to several macrophage surface proteins known to contribute to the recognition of apoptotic leukocytes, such as CD36, αvβ3, and CD11b/CD18 (19). We propose that the interaction between FPR2/ALX and phagocytosis could be related to the capacity of the receptor to form complexes with molecules/receptors involved in phagocytosis to facilitate internalization of the apoptotic cells analogous to the recent reports that FPR2/ALX can physically interact with the scavenger receptor MARCO in astrocytes and microglia, affecting the functionality of the receptor (48).

Previous studies have shown the FPR2/ALX undergoes clathrin-mediated and dynamin-dependent endocytosis and that it recycles in a slow pathway involving perinuclear recycling endosomes (49, 50). FPR2/ALX internalization was inhibited by either siRNA-mediated depletion of cellular clathrin or the expression of a dominant-negative mutant of dynamin in HeLa cells (49). Furthermore, in HEK293 cells cotransfected with FPR2/ALX and a β-arrestin-enhanced green fluorescent protein, the receptor was rapidly internalized after the addition of the synthetic agonist peptide WKYMVM (50). However, in these studies, the synthetic agonist peptide WKYMVM was used, explaining the difference in the data described in this study, using the anti-inflammatory ligands of the FPR2/ALX.

The internalization of the receptor is inhibited by pretreatment with PKC inhibitor. We have shown previously that PKC inhibition affected LXA4 activity in phagocytosis (20), which suggests that PKC plays an important role in the trafficking and functionality of FPR2/ALX. It has been shown that FPR2/ALX is phosphorylated in an agonist-dependent manner, but little is known about the nature of the kinases involved in the process. On the contrary, FPR3 displays a marked level of phosphorylation in the absence of stimulation (51). Because phosphorylation of these receptors is known to affect their internalization, it will be interesting to know whether constitutive phosphorylation of FPR3 is related to its cell surface expression pattern and correlated with the described constitutive internalization.

The availability of mice in which the FPR2/ALX ortholog mouse Fpr2 has been deleted (38) allowed us to fully characterize the role of this receptor in the patho-physiology of the resolution of inflammation. This recently generated colony helped in defining the role of this receptor in the anti-inflammatory effect of LXA4 and annexin A1, so that in absence of Fpr2, the agents were no longer able to inhibit PMN trafficking in response to local application of cytokines. Here we have generated cells from these mice demonstrating that both LXA4 and Ac2–26 could no longer stimulate phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs, whereas they stimulated clearance of these cells when macrophages generated from wild-type mice were used. This set of data provides strong proof-of-concept that Fpr2 is genuinely involved in the augmented phagocytosis elicited by LXA4 and Ac2–26, supporting further the findings generated with transfected cells and discussed above.

It is worth noting how no difference was found in the percentage of phagocytosis by bone marrow-derived macrophages isolated from wild-type or Fpr2−/− mice, indicating a lack of involvement of Fpr2 in the basal activity. Equally, it is unclear whether endogenous ligands for the receptor could be generated in these controlled and short-term in vitro settings. Of interest, WT and Fpr2−/− mice did not display any difference with respect to the extent of PMN migration elicited interleukin-1 (38); however, a clear difference was found with respect to susceptibility to the inhibitory properties of LXA4 and Ac2–26, similar to our in vitro observations on phagocytosis. Finally, Fpr2−/− mice showed a clear phenotype when a model of inflammatory arthritis (that lasts >2 wk) was applied, likely because endogenous agonists (with an evident anti-inflammatory profile) must be generated. This model is susceptible to the administration of apoptotic PMNs (52) so that when proresolving circuits are activated a genuine reduction of inflammation would ensue. It is intriguing to propose that the stimulating effect of LXA4 and Ac2–26 on apoptotic PMN phagocytosis would affect inflammatory arthritis, although this hypothesis would clearly require a separate and focused study. In conclusion, the data of this study elucidate the complex mechanisms of the FPR2/ALX receptor trafficking and functionality in the resolution of inflammation and provide a basis for the identification of novel therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Gareth Griffiths (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) for the helpful discussion. This work was supported by UCD Seed Funding (P.M., D.C.C.), Health Research Board, Ireland (C.G.), Science Foundation Ireland (C.G.), the EU FP6 EICOSANOX programme LSHM-CT-2004-00503 (P.M. and C.G.) and funded under the Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions (PRTLI), administered by the Higher Education Authority (P.M., D.C.C., T.T., C.G.). The support of the Wellcome Trust (086867/Z/08; M.P.) is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Serhan CN. Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxins are the first lipid mediators of endogenous anti-inflammation and resolution. Prostag. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2005;73:141–162. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maderna P, Godson C. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and the resolution of inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1639:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kieran NE, Maderna P, Godson C. Lipoxins: potential anti-inflammatory, proresolution, and antifibrotic mediators in renal disease. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1145–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon B, Godson C. Lipoxins: endogenous regulators of inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F189–F201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00224.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maderna P, Godson C. Taking insult from injury: lipoxins and lipoxin receptor agonists and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Prostag. Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2005;73:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:101–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maderna P, Godson C. Lipoxins: resolutionary road. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2009;158:947–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colgan SP, Serhan CN, Parkos CA, Delp-Archer C, Madara JL. Lipoxin A4 modulates transmigration of human neutrophils across intestinal epithelial monolayers. J. Clin. Investig. 1993;92:75–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI116601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TH, Horton CE, Kyan-Aung U, Haskard D, Crea AE, Spur BW. Lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 inhibit chemotactic responses of human neutrophils stimulated by leukotriene B4 and N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1989;77:195–203. doi: 10.1042/cs0770195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papayianni A, Serhan CN, Phillips ML, Rennke HG, Brady HR. Transcellular biosynthesis of lipoxin A4 during adhesion of platelets and neutrophils in experimental immune complex glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1295–1302. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papayianni A, Serhan CN, Brady HR. Lipoxin A4 and B4 inhibit leukotriene-stimulated interactions of human neutrophils and endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 1996;156:2264–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soyombo O, Spur BW, Lee TH. Effects of lipoxin A4 on chemotaxis and degranulation of human eosinophils stimulated by platelet-activating factor and N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine. Allergy. 1994;49:230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1994.tb02654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filep JG, Zouki C, Petasis NA, Hachicha M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin A(4) stable analogs are demonstrable in human whole blood: modulation of leukocyte adhesion molecules and inhibition of neutrophil-endothelial interactions. Blood. 1999;94:4132–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serhan CN, Yang R, Martinod K, Kasuga K, Pillai PS, Porter TF, Oh SF, Spite M. Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N, Yacoubian S, Lee CH, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1660–1665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907342107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat. Rev. 2002;2:965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godson C, Mitchell S, Harvey K, Petasis NA, Hogg N, Brady HR. Cutting edge: lipoxins rapidly stimulate nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;164:1663–1667. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell S, Thomas G, Harvey K, Cottell D, Reville K, Berlasconi G, Petasis NA, Erwig L, Rees AJ, Savill J, Brady HR, Godson C. Lipoxins, aspirin-triggered epilipoxins, lipoxin stable analogues, and the resolution of inflammation: stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in vivo. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:2497–2507. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000032417.73640.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reville K, Crean JK, Vivers S, Dransfield I, Godson C. Lipoxin A4 redistributes myosin IIA and Cdc42 in macrophages: implications for phagocytosis of apoptotic leukocytes. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1878–1888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maderna P, Cottell DC, Berlasconi G, Petasis NA, Brady HR, Godson C. Lipoxins induce actin reorganization in monocytes and macrophages but not in neutrophils: differential involvement of rho GTPases. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;160:2275–228323. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell D, O’Meara SJ, Gaffney A, Crean JK, Kinsella BT, Godson C. The Lipoxin A4 receptor is coupled to SHP-2 activation: implications for regulation of receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15606–15618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang N, Serhan CN, Dahlen SE, Drazen JM, Hay DW, Rovati GE, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T, Brink C. The lipoxin receptor ALX: potent ligand-specific and stereoselective actions in vivo. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:463–487. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009;61:119–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiore S, Ryeom SW, Weller PF, Serhan CN. Lipoxin recognition sites. Specific binding of labeled lipoxin A4 with human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16168–16176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang N, Fierro IM, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Activation of lipoxin A(4) receptors by aspirin-triggered lipoxins and select peptides evokes ligand-specific responses in inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1197–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim LH, Pervaiz S. Annexin 1: the new face of an old molecule. FASEB J. 2007;21:968–975. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7464rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perretti M, D’Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perretti M, Flower RJ. Annexin 1 and the biology of the neutrophil. J. Leuk. Biol. 2004;76:25–29. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perretti M, Chiang N, La M, Fierro IM, Marullo S, Getting SJ, Solito E, Serhan CN. Endogenous lipid- and peptide-derived anti-inflammatory pathways generated with glucocorticoid and aspirin treatment activate the lipoxin A4 receptor. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1296–1302. doi: 10.1038/nm786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maderna P, Yona S, Perretti M, Godson C. Modulation of phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by super-natant from dexamethasone-treated macrophages and annexin-derived peptide Ac(2–26) J. Immunol. 2005;174:3727–3733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scannell M, Flanagan MB, deStefani A, Wynne KJ, Cagney G, Godson C, Maderna P. Annexin-1 and peptide derivatives are released by apoptotic cells and stimulate phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. J. Immunol. 2007;178:4595–4605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflamma-tory circuitry: lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor ALX. Prostag. Leukot,. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2005;73:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano M, Recchia I, Recchiuti A. Lipoxin receptors. Sci. World J. 2007;7:1393–1412. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gavins FN, Yona S, Kamal AM, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Leukocyte antiadhesive actions of annexin 1: ALXR- and FPR-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Blood. 2003;101:4140–4147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Sullivan TP, Vallin KS, Shah ST, Fakhry J, Maderna P, Scannell M, Sampaio AL, Perretti M, Godson C, Guiry PJ. Aromatic lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 analogues display potent biological activities. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5894–5902. doi: 10.1021/jm060270d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dufton N, Hannon R, Brancaleone V, Dalli J, Patel HB, Gray M, D’Acquisto F, Buckingham JC, Perretti M, Flower RJ. Anti-inflammatory role of the murine formyl-peptide receptor 2: ligand-specific effects on leukocyte responses and experimental inflammation. J. Immunol. 184:2611–2619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parent JL, Labrecque P, Orsini MJ, Benovic JL. Internalization of the TXA2 receptor alpha and beta isoforms. Role of the differentially spliced COOH terminus in agonist-promoted receptor internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8941–8948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokuyasu KT. A technique for ultracryotomy of cell suspensions and tissues. J. Cell Biol. 1973;57:551–565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths G, McDowall A, Back R, Dubochet J. On the preparation of cryosections for immunocytochemistry. J. Ultra. Res. 1984;89:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(84)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayhoe RP, Kamal AM, Solito E, Flower RJ, Cooper D, Perretti M. Annexin 1 and its bioactive peptide inhibit neutrophil-endothelium interactions under flow: indication of distinct receptor involvement. Blood. 2006;107:2123–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perretti M, Wheller SK, Choudhury Q, Croxtall JD, Flower RJ. Selective inhibition of neutrophil function by a peptide derived from lipocortin 1 N-terminus. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995 Sep 28;50:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00238-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perretti M. The annexin 1 receptor(s): is the plot unravelling? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiore S, Maddox JF, Perez HD, Serhan CN. Identification of a human cDNA encoding a functional high affinity lipoxin A4 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:253–260. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwab JM, Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature. 2007;447:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olazabal IM, Caron E, May RC, Schilling K, Knecht DA, Machesky LM. Rho-kinase and myosin-II control phagocytic cup formation during CR, but not FcgammaR, phagocytosis. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandenburg LO, Konrad M, Wruck CJ, Koch T, Lucius R, Pufe T. Functional and physical interactions between formyl-peptide-receptors and scavenger receptor MARCO and their involvement in amyloid beta 1-42-induced signal transduction in glial cells. J. Neurochem. 113:749–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ernst S, Zobiack N, Boecker K, Gerke V, Rescher U. Agonist-induced trafficking of the low-affinity formyl peptide receptor FPRL1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:1684–1692. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huet E, Boulay F, Barral S, Rabiet MJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the formyl peptide receptor-like 1 internalization and signaling. Cell. Signal. 2007;19:1939–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Christophe T, Karlsson A, Dugave C, Rabiet MJ, Boulay F, Dahlgren C. The synthetic peptide Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-Met-NH2 specifically activates neutrophils through FPRL1/lipoxin A4 receptors and is an agonist for the orphan monocyte-expressed chemoattractant receptor FPRL2. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:21585–21593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gray M, Miles K, Salter D, Gray D, Savill J. Apoptotic cells protect mice from autoimmune inflammation by the induction of regulatory B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]