Summary

Psychological wellbeing and health are closely linked at older ages. Three aspects of psychological wellbeing can be distinguished: evaluative wellbeing (or life satisfaction), hedonic wellbeing (feelings of happiness, sadness, etc), and eudemonic wellbeing (sense of purpose and meaning in life). We review recent advances in this field, and present new analyses concerning the pattern of wellbeing across ages and the association between wellbeing and survival at older ages. The Gallup World Poll, an ongoing survey in more than 160 countries, shows a U-shaped relationship between evaluative wellbeing and age in rich, English speaking countries, with the lowest levels of wellbeing around ages 45-54. But this pattern is not universal: for example, respondents from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe show a large progressive decline in wellbeing with age; Latin America also shows falling wellbeing with age, while wellbeing in sub-Saharan Africa shows little change with age. The relationship between physical health and subjective wellbeing is bidirectional. Older people suffering from illnesses such as coronary heart disease, arthritis and chronic lung disease show both raised levels of depressed mood and impaired hedonic and eudemonic wellbeing. Wellbeing may also have a protective role in health maintenance. In an illustrative analyses from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), we find that eudemonic wellbeing is associated with longer survival; 29.3% of people in the lowest wellbeing quartile died over the average follow-up period of 8.5 years compared with 9.3% of those in the highest quartile. Associations were independent of age, gender, demographic factors, and baseline mental and physical health. We conclude that the wellbeing of the elderly is an important objective for both economic and health policy. Current psychological and economic theories do not adequately account for the variations in pattern of wellbeing with age across different parts of the world. The apparent association between wellbeing and survival is consistent with a protective role of high wellbeing, but alternative explanations cannot be ruled out at this stage.

Introduction

People’s self-reports of their psychological wellbeing are becoming a focus of intense debate in public policy and in economics, and improving the wellbeing of the population is emerging as a key societal aspiration. The Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress initiated by the French government and chaired by Joseph Stiglitz argued that current measures of economic performance such as gross domestic product are insufficient as indicators of the progress of society, and that self-reported wellbeing should also be taken into account.1 In the UK, the Office for National Statistics is driving a national debate over measuring wellbeing,2 the Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index Poll interviews 1,000 US adults every day about wellbeing, and similar initiatives are taking place in other countries.3

Psychological wellbeing and health are closely related, and the link may become more important at older ages, if only because the prevalence of chronic illness increases with advancing age. As life expectancy increases and treatments for life-threatening disease become more effective, the issue of maintaining wellbeing at advanced ages is growing in importance. Studies of older people indicate that evaluations of quality of life are affected by the person’s state of health, but the frequent finding that average self-reported life evaluation in the population increases with age suggests that psychological wellbeing is affected by many factors other than health. These include material conditions, social and family relationships, social roles and activities, factors that also change with age. There is a growing research literature suggesting that psychological wellbeing may even be a protective factor in health, reducing the risk of chronic physical illness and promoting longevity. It has also been argued that psychological wellbeing should be addressed in measures of health valuation, and be considered in health care resource allocation.4 This article summarises the current state of evidence linking psychological wellbeing with health in an ageing population.

Measurement of psychological wellbeing

Within the construct of psychological wellbeing, there are at least three different approaches, each capturing a different aspect: life evaluation, hedonic wellbeing, and eudemonic wellbeing.5 (1) Life evaluation refers to peoples’ thoughts about the quality or goodness of their lives, their overall life satisfaction or sometimes how happy they are with their lives. Measurement uses such questions as the Cantril Ladder,6 wherein individuals are asked to place themselves on an 11-step ladder with ‘worst possible life’ representing the lowest rung and ‘best possible life’ the top rung. Instructions are usually vague about how the evaluation should be made. (2) Hedonic wellbeing refers to everyday feelings or moods such as experienced happiness (the mood, not the evaluation of life), sadness, anger, and stress, and is measured by asking respondents to rate their experience of several affect adjectives such as happy, sad, and angry.7 It is important to note that the negative adjectives are not simply the opposite of positive indicators of wellbeing – they carry unique information about peoples’ emotional states; in other words, hedonic wellbeing is not a simple unipolar dimension, but is composed of at least two modestly associated dimensions. Therefore, positive and negative adjectives are required for a reasonable assessment of hedonic wellbeing. (3) Eudemonic wellbeing focuses on judgments about the meaning and purpose of one’s life; because the construct is more diverse, several questionnaires tapping various aspects of meaning have been developed.8 An important distinction among the types of wellbeing is the level of cognitive processing required: feelings can be reported relatively directly, whereas life evaluations and meaning questions are likely to demand considerable reflection including aggregation over time and comparison with self-selected standards (e.g., my life compared to what, when, or whom?).

There is considerable debate about how the three types of measures fit into human wellbeing more broadly. Economic status, freedom, and physical health are all important for human flourishing, just as is mental health. Some scholars have argued that life evaluation questions capture everything that matters;9 others recognize its importance, without giving it any special status.10 For our purposes, we do not need to address these questions, let alone settle them. Instead, we describe patterns of aging in relation to evaluative and hedonic wellbeing in the next section, turning to eudemonic wellbeing at the end of the paper.

There has been a revolution in the assessment of hedonic wellbeing over the past decade. Conventionally, measures of hedonic wellbeing ask the respondent to reflect over the previous week or month which—given the inability of people to remember their affective states--is likely to induce an evaluative, not a hedonic response. The new approaches greatly reduce this problem by having individuals report about relatively brief and recent periods and thus more directly taps emotional states without the overlay of evaluation. Reporting periods for such assessments may range from the immediate moment through longer periods such as a day; to establish more reliable hedonic indices, multiple momentary ratings are usually averaged. Ecological momentary assessment11 —whereby subjects are randomly prompted to report affect—has many desirable features, but can be closely replicated by the Day Reconstruction Method9 —in which people remember episodes from the previous day, and associated feelings with them—or even, for large sample averages, by asking people about their feelings for the entire previous day (the procedure used in the Gallup-Healthways interview).

Wellbeing in older people

What is the association between wellbeing and age? The best information available is from large-scale international surveys that have asked about life evaluation, although more recent surveys have also included measurement of hedonic and eudemonic wellbeing. One recent study examined assessments of life evaluation (broadly-defined “happiness” with life or life satisfaction) in several European, American, Asian, and Latin American cross-sectional surveys over several time periods, and replicated prior findings of a U-shaped association between age and wellbeing with the nadir at middle age and higher wellbeing in younger and older adults.12 The U-shape of life evaluation is often taken to be a standard finding, and has recently been replicated in non-human primates,13 but there a number of studies with different results,14, and one analysis of longitudinal data from Britain, Germany, and Australia finds no such shape once individual fixed effects are incorporated.15 A study analysing a single year of data from the Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index in the US allowed for a comparison of life evaluation and hedonic wellbeing; hedonic wellbeing was assessed with ratings of yesterday’s emotions, and life evaluation with the Cantril Ladder. Striking differences in pattern of wellbeing over age were detected between the life evaluation and negative emotions.15 Life evaluation followed the U-pattern with a nadir in the mid-50s; however, the occurrence of ‘a lot of stress’ or ‘a lot of anger’ yesterday declined throughout life, more rapidly so after age 50. Worry remained elevated until age 50 and declined thereafter, whereas two positive emotions were similar in pattern to that of life evaluation. These findings are consistent with other results such as a recent study on income and wellbeing,16 and argue that hedonic and evaluative wellbeing are essentially different, so multiple indicators should ideally be assessed.

One particularly intensive study supports the finding of hedonic wellbeing improving with advancing age. Analyses of five momentary samples of affect (using the format ‘how are you feeling right now?’) per day recorded over seven days showed that the frequency of negative emotions decreased at middle age, although their intensity did not.17 The high density of affect recording enabled distinctions to be made between severity and frequency, a contrast that is not possible with ‘yesterday’ or longer reporting periods, providing new insight into the lives of older people and dispels the idea that the intensity of experiences diminishes with age.

The preeminent theory emerging from these and other results is socio-emotional selectivity theory,18 which posits that as people age they accumulate emotional wisdom that leads to selection of more emotionally satisfying events, friendships, and experiences. Thus despite factors such as the death of loved ones, loss of status associated with retirement, deteriorating health and reduced income – though perhaps also reduced material needs - older people maintain and even increase self-reported wellbeing by focusing on a more limited set of social contacts and experiences. Although the findings support this notion, it is notable that the theory only predicts higher wellbeing in older ages, but does not predict the U-shape pattern of life satisfaction or the flat and then decreasing pattern for stress. Yet it offers an explanation of how, in spite of declining health and income with age, psychological wellbeing may improve. By contrast, economic theory can predict the dip in wellbeing in middle-age; this is the period at which wage rates typically peak and is the best time to work and earn the most, even at the expense of current wellbeing, in order to have higher wealth and wellbeing in later life.

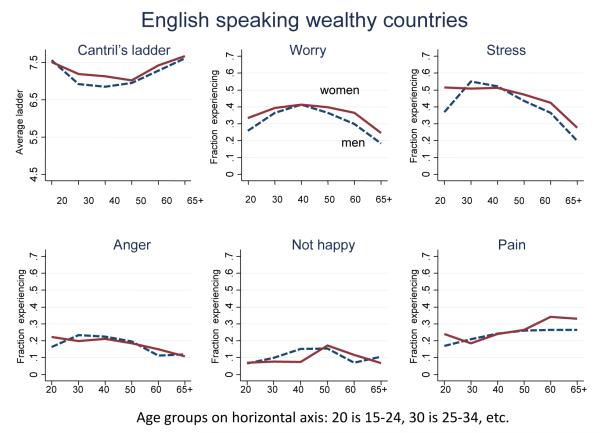

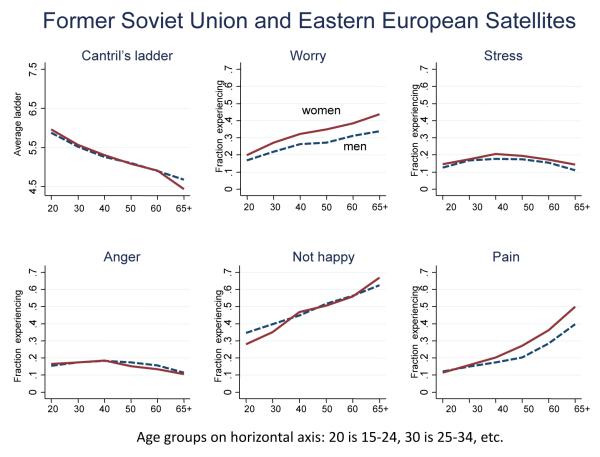

These findings suggest that older populations, although less healthy and less productive in general, may be more satisfied with their lives, and experience less stress, worry, and anger than do middle-aged people. However, our on-going research shows that these patterns of psychological wellbeing are not universal across populations. Gallup’s World Poll, which began in 2006, continually surveys residents in more than 160 countries, covering more than 98 percent of the world’s population, using random nationally representative samples, typically of 1,000 individuals in each country. Telephone interviews are used in rich countries, and face to face interviews elsewhere; Gallup pre-tested its questions for lack of mode bias, and even if this cannot be entirely excluded, it should not affect the age patterns within countries, though the institutionalized and disabled elderly populations will be largely missed in the telephone surveys. The surveys are conducted once a year, lasting two to four weeks, and the majority of countries have been covered every year. Here, we use the data from 2006 to 2010 to examine patterns of wellbeing with age in different regions of the world; we look at regions because examining results country by country is unwieldy, but note that this means that the sample sizes are different for each region, roughly proportional to the number of countries in each. The U-shaped pattern of life evaluation with age, with the elderly having the highest life evaluation, is most strongly evident in the rich, English speaking world, while in some other regions of the world — most notably the Middle East, the countries of the former Soviet Union, and sub-Saharan Africa — life evaluation declines steadily with age, at least in the period 2006-2010. Figures 1 and 2 show cross-sectional age profiles of life-evaluation and various hedonic experiences for the populations of two regions, Anglo (US, Canada, UK, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia), and the 29 countries of the former Soviet Union and former satellites in Eastern Europe. While the latter are diverse in their political and health experiences during the transition in social organisation following the collapse of communism, they have the transition itself in common, and serve to illustrate the diversity of aging experience around the world. To aid comparison, the scales are the same for both regions; for the ladder, we show life evaluation as the mean score on the Cantril ladder while for the hedonics, we show the fraction of the population who reported “a lot” of the emotion on the previous day except for experienced happiness, where we show the fraction who reported that they did not experience a lot of happiness. So for all the hedonic experiences, higher values are worse. In the transition countries, life evaluations were lower overall than in the Anglo countries, and the elderly do particularly badly, the opposite of the Anglo countries. Not being happy, which is uncommon in the Anglo countries, is quite common in the transition countries, particularly so among the elderly, where nearly 70 percent of those aged 65 and above did not experience happiness in the previous day. Worry increases with age in the transition countries, and decreases in the Anglo countries.

Figure 1. Life evaluation and hedonics and age in wealthy English speaking countries.

The Cantril ladder ranges from 0 (worst possible life) to 10 (best possible life), and the graph shows the average. The hedonic experiences are the fractions of each age group reporting that they experienced “a lot of” X in the previous day. Those aged 76 and above are excluded. The countries are United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. There are 13,762 observations for happiness, and a little less than 25,000 for the other measures. Means by age are first calculated for each country, and the regional average obtained by weighting by each country’s total population. Sample size is approximately proportional to the number of countries in the region. Happiness measures were not collected in all waves.

Figure 2. Life evaluation and hedonics and age in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

The countries are Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. There are 63,325 observations for happiness, and around 113,000 for the other measures. See also notes to Figure 1.

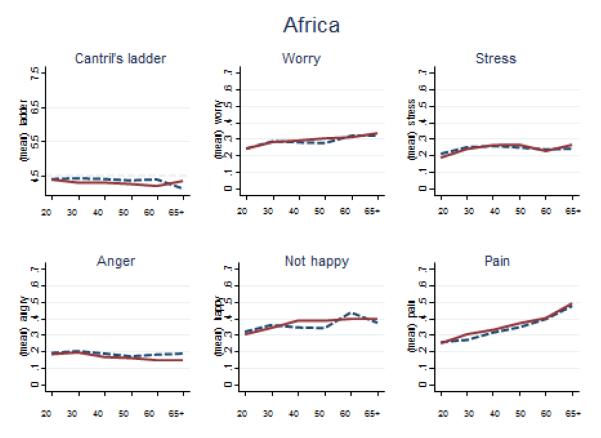

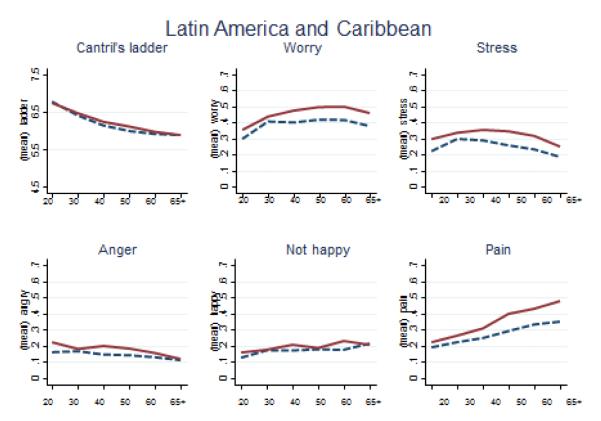

These features undoubtedly reflect the recent experiences of the region (cohort effects), and the distress these events have brought to the elderly, who have lost a system that, however imperfect, gave meaning to their lives, as well as, in some cases, their pensions and their healthcare. The results and patterns elsewhere testify to the lack of globally universal age patterns. In sub-Saharan Africa, Figure 3, life evaluation is extremely low at all ages (a reflection of the strong positive cross-country relationship between life evaluation and income19) but there is little or no variation with age. The prevalence of worry, stress, and unhappiness all rise mildly with age. The much richer region of Latin America and the Caribbean, Figure 4, is different yet again, with life evaluation falling with age— though not as sharply as in the Eastern European countries—while worry and stress peak in middle age, though the age-profile is not as marked as elsewhere. The differences between men and women are modest relative to the similarities in their age profile, though it is perhaps notable that elderly women in the transition countries report substantially more worry, pain, stress and pain than do elderly men, in spite of the fact that, in several of these countries, it is men’s health that has differentially suffered. Even so, the Cantril ladder measures of overall life evaluation are almost identical for men and women, another indication of the importance of distinguishing different aspects of wellbeing. A strength of these new results is that they use identical questions on different aspects of subjective wellbeing for random samples for a large number of countries. One possible weakness compared with earlier results 12,14,20—with which they are only partially consistent—is the lack of a time dimension, which cannot be realistically explored with only four years of data.

Figure 3. Life evaluation and hedonics and age in sub-Saharan Africa.

The countries are Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Brazzaville), Congo (Kinshasa), Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauretania, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somaliland, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe. There are 124,800 observations in all, with country sample sizes ranging from nearly 7,000 (Mauretania) to 1,000 for six countries. See also notes to Figure 1.

Figure 4. Life evaluation and hedonics and age in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The countries are Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela. There are 96,154 observations in all, with country sample sizes ranging from over 5,000 to 500. See also notes to Figure 1.

There are many remaining challenges in understanding the patterns of age and wellbeing around the world. A fundamental problem for this research area is obtaining funding for the continuation of worldwide polls, and this should not be underestimated, especially in fiscally difficult times. Concerns have been voiced regarding potential methodological problems including ensuring comparability in the sampling techniques and standardizing the interpretation of questions and response scales across countries. Finally, there is work to be done on understanding the reasons for the observed age patterns. Current theories are not yet adequately accounting for the age patterns and country differences. In spite of these and other challenges, we believe that over the last decade there has been significant progress in documenting age differences in self-reported wellbeing.

Psychological wellbeing as a determinant of physical health at older ages

The notion that impaired psychological wellbeing is associated with increased risk of physical illness is not new, since there is an established research literature linking depression and life stress with premature mortality, coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes, disability and other chronic conditions.21 What is new is the possibility that positive, psychological wellbeing is a protective factor.22 Prospective epidemiological studies suggest that positive life evaluations and hedonic states such as happiness predict lower future mortality and morbidity.23 Research of this type is susceptible to the well-recognised problems of observational epidemiology, including confounding – the possibility that wellbeing is coupled with other factors such as greater education that account for associations with health outcome - and reverse causality – the possibility that the person who reports poor wellbeing is already ill at the time of initial assessment. There is also the issue of publication bias, with evidence that studies showing a favourable impact of wellbeing on health are more likely to appear in print.23

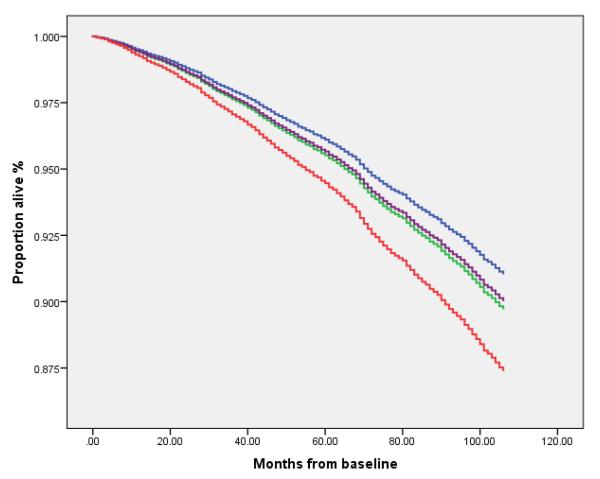

However, stronger evidence is beginning to emerge, using both retrospective questionnaire assessments of eudemonic wellbeing and momentary hedonic measures taken repeatedly over the day.24-27 To illustrate this pattern we have carried out new analyses relating eudemonic wellbeing to mortality in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA).28 9,050 core members of the cohort (mean age 64.9, standard deviation 10.0 years) were followed for an average of 8.5 years, and 1,542 dated fatalities were analysed. Eudemonic wellbeing was assessed with items from a standard questionnaire assessing autonomy, sense of control, purpose in life, and self-realisation (see online supplement). The cohort was divided into quartiles of wellbeing, and Cox proportional hazards regression was applied. The proportion of deaths was 29.3% in the lowest quartile, 17.5% in the second quartile, 13.4% in the third quartile, and 9.3% in the highest quartile. The regression analyses document the graded association between eudemonic wellbeing and survival (Table 1). Compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile of wellbeing was associated with a 58% (95%CI 50.7 - 63.8) reduction in risk after adjusting for age and gender. This effect was attenuated to a 30% (95%CI 16.7 – 41.7%) reduction in risk after sociodemographic factors including education and wealth, initial health status, measures of depression and health behaviours such as smoking, physical activity and alcohol consumption had been taken into account. Other independent predictors of mortality in the final model were older age, being male, less wealth, being unmarried, not being in paid employment, a diagnosis at baseline of cancer, coronary heart disease, diabetes, heart failure, chronic lung disease and stroke, reporting a limiting longstanding illness, smoking and physical inactivity (see supplementary Table 1 for the full model 5). Figure 5 shows a Kaplan-Meier plot of survival in relation to baseline eudemonic wellbeing in the fully adjusted model.

Table 1.

Eudemonic wellbeing and mortality: complete sample

| Model | Covariates | Eudemonic wellbeing |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartiles | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% C.I.) |

||

| Model 1 | Age, gender | 1 (lowest) | 1 |

| 2 | 0.620 (0.547 to 0.702) | ||

| 3 | 0.547 (0.475 to 0.629) | ||

| 4 (highest) | 0.422 (0.362 to 0.493) | ||

| Model 2 | Age, gender, + demographic factorsa | 1 (lowest) | 1 |

| 2 | 0.665 (0.586 to 0.754) | ||

| 3 | 0.613 (0.531 to 0.708) | ||

| 4 (highest) | 0.489 (0.417 to 0.574) | ||

| Model 3 | Age, gender, + demographic factorsa + health indicatorsb |

1 (lowest) | 1 |

| 2 | 0.746 (0.656 to 0.849) | ||

| 3 | 0.733 (0.631 to 0.852) | ||

| 4 (highest) | 0.624 (0.526 to 0.740) | ||

| Model 4 | Age, gender, + demographic factorsa + health indicatorsb + depressionc |

1 (lowest) | 1 |

| 2 | 0.761 (0.666 to 0.869) | ||

| 3 | 0.753 (0.644 to 0.881) | ||

| 4 (highest) | 0.643 (0.538 to 0.768) | ||

| Model 5 | Age, gender, + demographic factorsa + health indicatorsb + depressionc + health behaviors |

1 (lowest) | 1 |

| 2 | 0.780 (0.683 to 0.891) | ||

| 3 | 0.805 (0.688 to 0.942) | ||

| 4 (highest) | 0.697 (0.583 to 0.833) | ||

Reference group is lowest eudemonic well-being group. Deaths: 608/2078 in the lowest, 418/2388 in the second, 289/2151 in the third, and 227/2433 in the highest eudemonic well-being group.

Demographic factors: wealth, education, ethnicity, marital status, and employment status

Health indicators: limiting long-standing illness, cancer, CHD, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, and chronic lung disease

History of depressive illness and elevated scores on the CES-D depression scale

Health behaviors: smoking, physical activity, and alcohol intake

Figure 5. Eudemonic wellbeing and survival.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the four quartiles of eudemonic wellbeing in ELSA: highest wellbeing quartile (blue), second wellbeing quartile (purple), third wellbeing quartile (green), lowest wellbeing quartile (red). Survival in months from baseline is modelled after adjustment for age, gender, demographic factors, baseline health indicators, history of depressive illness and depression symptoms, and baseline health behaviours.

These results do not unequivocally demonstrate that eudemonic wellbeing is causally linked with mortality. There is a danger in overstating the evidence for a causal link, since people may feel that they are to blame for not seeing the meaning in life or perceiving greater control in the face of serious illness.29 The association may be due to unmeasured confounders, or eudemonic wellbeing may be a marker of underlying biological processes or behavioural factors that are responsible for the effect on survival. But the findings do raise intriguing possibilities about positive wellbeing being involved in reduced risk to health. They also raise the question of whether wellbeing-selective mortality can help explain the age patterns of wellbeing in the previous section. The US life table for 2008 shows a decadal mortality rate of 12.7% for 60 year-olds. If all this mortality came from those with the lowest life evaluation—which is the maximum possible effect—the average ladder rating would have risen from 6.78 at age 60 to 7.32 among the survivors, compared with an actual average at 70 of 7.10. Of course, we do not know the ladder scores of either survivors or decedents, but this calculation suggests that effects of selective mortality might be big enough to play a role. Against this, however, is the fact that mortality rates from age 60 are higher in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa than in the rich English speaking countries, which would lead to a stronger U, not the complete absence that we observe.

Progress is also being made in understanding the behavioural and biological correlates of positive psychological wellbeing. Among lifestyle factors, physical activity is probably the most important link between psychological wellbeing and health. Regular physical activity at older ages is already recommended for the maintenance of cardiovascular health, muscle strength and flexibility, glucose metabolism, and healthy body weight, and is also consistently correlated with wellbeing.30 At the biological level, positive wellbeing is associated with lower cortisol output over the day.31,32 This is potentially important, since elevated cortisol plays a role in lipid metabolism, immune regulation, central adiposity, hippocampal integrity and bone calcification. Positive affect has been related to reduced inflammatory and cardiovascular responses to acute mental stress, and is associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 in older women, and with higher levels of the steroid hormone dehydroepiandosterone sulfate.33 Interestingly, these effects are more robust when positive affect is measured by aggregating momentary estimates of affective states over the day than with questionnaire measures.34 The next step in this research agenda is to determine whether these processes are contributors to associations between positive self-reported wellbeing and sustained health in older people.

Physical illness as a determinant of impaired psychological wellbeing

Clinical and community studies show that a wide range of medical conditions are associated with raised levels of depression, including illnesses that are prevalent at older ages. A sizable proportion of individuals show increases in depressive symptomatology following diagnoses of diabetes, CHD, stroke, some cancers and chronic kidney disease,35-37 while collaborative care that focuses both on mental health and physical illness has beneficial effects on both.38 Ill-health is also associated with reduced positive wellbeing. For example, one recent study of 11,523 older men and women in ELSA showed that chronic illnesses were associated with lower hedonic and eudemonic wellbeing.39 The greatest effects were for stroke, chronic lung diseases and rheumatoid arthritis, with more modest but still significant impairments among individuals with diabetes and cancer. The reductions in happiness (assessed over the previous week) and eudemonic wellbeing increased progressively with number of comorbidities. These analyses were cross-sectional, so it is not known whether reduced self-reported wellbeing preceded or followed illness onset. Firmer conclusions must await prospective analyses of these associations. Additionally, shifts in responses on patient reported outcomes are known to take place as people adapt to illness, leading to lower levels of distress and impairment of quality of life (and possibly higher levels of happiness) than might be expected.40

The end of life is another setting where health clearly impacts psychological state, yet the medical establishment has struggled with ensuring optimal levels of wellbeing. High quality end-of-life care is crucial to a ‘good death’, but faces many institutional and financial barriers, particularly for individuals in long-term care.41 A primary focus of medical and palliative care is the relief of pain and suffering, but surveys indicate that unrelieved pain and poor management of dyspnea remain common in many types of nursing facility. Hospice care is associated with higher quality pain and symptom management, but aspects of wellbeing, such as a sense of dignity and relief of distress, are seldom addressed systematically. The application of standardised measures of quality of dying, usually completed by relatives or carers, may encourage more direct evaluations of the experiences promoting optimal psychological wellbeing.42 Analyses of population-based cohorts may also provide valuable information about the use of advanced directives and the extent to which fulfilment of preferences enhances wellbeing at the end of life.43 Additionally, short-term psychotherapy designed to enhance the dignity of end of life experiences may have beneficial effects.44

Conclusions

Research into psychological wellbeing and health at older ages is at an early stage. Nevertheless, the wellbeing of the elderly is important in its own right, and there is suggestive evidence that positive hedonic states, life evaluation, and eudemonic wellbeing are relevant to health and quality of life as people age. Health care systems should be concerned not only with illness and disability, but with supporting methods of improving positive psychological states. It is premature to contemplate large scale clinical trials to evaluate the effects of efforts to increase enjoyment of life on longevity; we do not yet know whether wellbeing is sufficiently tractable through psychological, societal or economic interventions to test effects on health outcomes. Much of our knowledge about psychological wellbeing at older ages comes from longitudinal population cohort studies, and sustained investment in these research resources is essential. Novel methods of assessing hedonic wellbeing and time use are enhancing our understanding of the processes underlying positive psychological states at older ages. Most of the studies involve high income and not low or middle income countries. However, cross-national surveys such as the Gallup World Poll, and longitudinal cohorts studies of ageing in China, India, South Korea, Brazil, and the WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) are beginning to redress the balance. The implications of this new knowledge about psychological wellbeing for economic and health policy have yet to be established.

Supplementary Material

Literature Search Statement.

We searched PubMed and Web of Science using the terms “happiness”, “positive wellbeing”, “life satisfaction”, “aging”, “health” and “mortality”. Our search covered articles published in English between Jan 1, 2000, and March 31, 2012. We identified additional reports from the reference lists of selected articles. Some important older publications are cited either directly or indirectly through review articles.

Key messages.

There have been major recent advances in measuring and interpreting subjective wellbeing

Different measures - life evaluation, hedonic experience, and meaningfulness - tap into different aspects of experience and have different correlates.

In rich, English speaking countries, life evaluation dips in middle age, and rises into old age, but this U-shaped pattern does not hold in other regions of the world.

There is a two-way relationship between physical health and subjective wellbeing

There is evidence that is consistent with psychological wellbeing being protective

Acknowledgements

AS is supported by the British Heart Foundation. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing was developed by a team of researchers based at University College London, the Institute of Fiscal Studies and the National Centre for Social Research. The funding is provided by the National Institute on Aging (grants 2RO1AG7644-01A1 and 2RO1AG017644) and a consortium of UK government departments coordinated by the Office for National Statistics. AD and AAS are supported by the National Institute on Aging through the National Bureau of Economic Research, Grants 5R01AG040629–02 and P01 AG05842–14, and by the Gallup Organization.

Funding US National Institute on Aging, British Heart Foundation, Office for National Statistics.

Footnotes

Contributors AS, AD and AAS were responsible for the article format and drafted the report. AS carried out analyses of ELSA, while AD and AAS carried out analyses of the Gallup World Poll. All authors contributed to revision and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interest AS declares he has no conflicts of interest. AD and AAS are Senor Scientists with the Gallup Organization.

Contributor Information

Andrew Steptoe, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, London, UK.

Angus Deaton, Woodrow Wilson School and Department of Economics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Arthur A. Stone, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Stiglitz J. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009 www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr.

- 2.Seaford C. Policy: Time to legislate for the good life. Nature. 2011;477(7366):532–3. doi: 10.1038/477532a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harter JK, Gurley VF. Measuring health in the United States. APS Observer. 2008;21:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan P, White MP. How can measures of subjective well-being be used to inform public policy? Persp Psychol Sci. 2007;2:71–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone AA. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science. 2004;306(5702):1776–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryff CD, Singer BH, Dienberg Love G. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1383–94. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Layard R. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. 2nd Edition Penguin; London: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen A. The Idea of Justice. Allen Lane; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1733–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss A, King JE, Inoue-Murayama M, Matsuzawa T, Oswald AJ. Evidence for a midlife crisis in great apes consistent with the U-shape in human wellbeing. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(49):19871–19872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212592109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frijters P, Beatton T. The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. J Econ Behav Organization. 82(102):525–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Deaton A. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(22):9985–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahneman D, Deaton A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(38):16489–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27(2):103–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deaton A. Income, health, and wellbeing around the world: evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(2):53–72. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulloa BFL, Møller V, Sousa-Poza A. How does subjective well-being evolve with age? A literature review. 2013 IZA DP No. 7328. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2250327.

- 21.Steptoe A, editor. Depression and Physical Illness. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–55. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(7):741–56. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson KW, Mostofsky E, Whang W. Don’t worry, be happy: positive affect and reduced 10-year incident coronary heart disease: the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(9):1065–70. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(4):655–691. doi: 10.1037/a0027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Enjoying life and living longer: A prospective analysis from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):273–5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Positive affect measured using ecological momentary assessment and survival in older men and women. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(45):18244–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Int J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sloan RP. Virtue and vice in health and illness: the idea that wouldn’t die. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):896–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Windle G, Hughes D, Linck P, Russell I, Woods B. Is exercise effective in promoting mental well-being in older age? A systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(6):652–69. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Marmot M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6508–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steptoe A, O’Donnell K, Badrick E, Kumari M, Marmot MG. Neuroendocrine and inflammatory factors associated with positive affect in healthy men and women: Whitehall II study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:96–102. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steptoe A, Demakakos P, De Oliveira C, Wardle J. Distinctive biological correlates of positive psychological well-being in older men and women. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(5):501–508. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f82c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steptoe A, Gibson EL, Hamer M, Wardle J. Neuroendocrine and cardiovascular correlates of positive affect measured by ecological momentary assessment and by questionnaire. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a Meta-Analysis. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5349–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Afshar M, Toto RD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. J Amer Med Assoc. 2010;303(19):1946–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meijer A, Conradi HJ, Bos EH, Thombs BD, van Melle JP, de Jonge P. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of 25 years of research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(3):203–16. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wikman A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Quality of life and affective well-being in middle-aged and older people with chronic medical illnesses: a cross-sectional population based study. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1507–15. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huskamp HA, Kaufmann C. Stevenson DG. The intersection of long-term care and end-of-life care. Med Care Res Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1077558711418518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. The quality of dying and death. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(9):912–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.