Abstract

The human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ib gene, HLA-E, codes for the major ligand of the inhibitory receptor NK-G-2A, which is present on most natural killer (NK) cells and some CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. We have previously shown that gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induction of HLA-E gene transcription is mediated through a distinct IFN-γ-responsive element, the IFN response region (IRR), in all cell types studied. We have now identified and characterized a cell type-restricted enhancer of IFN-γ-mediated induction of HLA-E gene transcription, designated the upstream interferon response region (UIRR), which is located immediately upstream of the IRR. The UIRR mediates a three- to eightfold enhancement of IFN-γ induction of HLA-E transcription in some cell lines but not in others, and it functions only in the presence of an adjacent IRR. The UIRR contains a variant GATA binding site (AGATAC) that is critical to both IFN-γ responsiveness and to the formation of a specific binding complex containing GATA-1 in K562 cell nuclear extracts. The binding of GATA-1 to this site in response to IFN-γ was confirmed in vivo in a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Forced expression of GATA-1 in nonexpressing U937 cells resulted in a four- to fivefold enhancement of the IFN-γ response from HLA-E promoter constructs containing a wild-type but not a GATA-1 mutant UIRR sequence and increased the IFN-γ response of the endogenous HLA-E gene. Knockdown of GATA-1 expression in K562 cells resulted in a ∼4-fold decrease in the IFN-γ response of the endogenous HLA-E gene, consistent with loss of the increase in IFN-γ response of HLA-E promoter-driven constructs containing the UIRR in wild-type K562 cells. Coexpression of wild-type and mutant adenovirus E1a proteins that sequester p300/CBP eliminated IFN-γ-mediated enhancement through the UIRR, but only partially reduced induction through the IRR, implicating p300/CBP binding to Stat-1α at the IRR in the recruitment of GATA-1 to mediate the cooperation between the UIRR and IRR. We propose that the GATA-1 transcription factor represents a cell type-restricted mediator of IFN-γ induction of the HLA-E gene.

The nonclassical, or class Ib, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I genes include the human HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G loci, the mouse Qa-1b locus, the rat RT1-E locus, and the monkey MHC-E locus (1, 24, 31, 32). These nonclassical MHC class I genes share many features with the classical class I genes, including a homologous heavy chain structure, but with significantly reduced polymorphism (46). Instead of foreign peptides, HLA-E predominantly binds a very restricted subset of peptides (consensus, VMAPRTVLL) derived from the leader sequences of the HLA class Ia proteins (3, 9, 10). HLA-E is the major ligand for the inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A found on natural killer (NK) cells and some CD8+ T cells and functions to inhibit lysis of target cells via this interaction (1, 8, 25, 28, 34).

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) stimulates the MHC class I genes, as well as many other genes involved in immune responses, by activating the JAK-1/2 and Stat-1 signal transduction pathway associated with the IFN-γ receptor (4, 12, 33, 38). IRF-1, a transcription factor whose expression is stimulated by Stat-1, binds to a consensus DNA sequence now known as an interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE) found in the promoter proximal region of the MHC class Ia genes (17, 18, 27, 35). IFN-α/β also activates a JAK/Stat pathway, but this results in the formation of the ISGF-3 complex (Stat-1, Stat-2, and IRF-9) that can also bind the ISRE (26). The ISRE directly mediates responsiveness of HLA class I genes to IFNs, as evidenced by the reduced IFN-γ response through the variant ISRE in the HLA-A promoter (22, 40). Full activation of transcription induced by IFN-γ requires phosphorylation of serine-727 in Stat-1, which is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (20, 45).

The promoter of the HLA class Ib molecule HLA-E differs significantly from other class Ib and the HLA class Ia genes, as its putative ISRE site lacks the consensus sequence to the extent that it cannot mediate a transcriptional response to IFNs (21). Despite this fact, HLA-E is induced at a transcriptional level by IFN-γ through a unique interferon response region (IRR). The IRR consists of two half-sites, with one half-site having some homology to a canonical gamma activation sequence and the other corresponding to the variant ISRE, and it binds an activation complex (IRR-AC) that contains Stat-1α (21). Unlike the gp91phox gene promoter, which contains tandem gamma activation sequence and ISRE sites and in which Stat-1 dimers interact with adjacently bound IRF-1 to activate transcription in response to IFN-γ, IRF-1 does not bind the IRR of HLA-E (21, 23). These observations suggest that the regulation of HLA-E by IFN-γ differs significantly from that of other HLA class I genes in both mechanisms and components, providing potential targets for selective manipulation of HLA-E expression in the setting of cancer immunotherapy, antiviral immunity, and bone marrow transplantation.

The GATA family of transcription factors was first characterized by its involvement in the differentiation of hematopoietic cells. The first member of this family was simultaneously described as GF-1 and EryF-1 by two groups and later renamed GATA-1 (16, 37). There are currently six recognized family members, all of which bind the consensus DNA site WGATAR (reviewed in references 30 and 44). GATA-1, GATA-2, and GATA-3 are all associated with hematopoiesis, whereas GATA-4, GATA-5, and GATA-6 are implicated in cardiac development, embryonic foregut formation, and lung development and may, in addition to GATA-3, serve some roles in neurogenesis (19, 30). Despite their varied tissue distributions, all GATA family members share two related zinc finger motifs that mediate DNA binding. Of the two GATA zinc fingers, only the C-terminal motif is absolutely required for DNA binding, while both it and the N-terminal finger can interact with other proteins (7). Although they recognize the same consensus sequence, GATA family members are not always interchangeable. For example, although GATA-2 expression can mostly compensate for GATA-1 loss in proerythroblastic cell knockouts, forced GATA-1 or GATA-3 expression cannot compensate for GATA-2 loss in differentiating murine embryonic stem cells (11, 43). GATA-1 and other GATA family members act, at least in part, by recruiting the transcriptional coactivator p300/CBP via direct protein-protein interactions or in cooperation with other transcription factors (6).

In this report, a cell type-restricted enhancer of the IRR-mediated IFN-γ induction of HLA-E, designated the upstream interferon response region (UIRR), was localized to the 38 bp immediately 5′ to the IRR. The UIRR augmented IFN-γ induction in K562 cells, in which GATA-1 is expressed, but not in U937 cells, in which no GATA factors are expressed. Detailed mutagenesis identified a nonconsensus GATA binding site (AGATAC) that was critical to the function of the UIRR, as well as to the binding of specific complexes to a UIRR probe in gel electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). Expression of GATA family transcription factors in specific cell types correlated with UIRR functionality. Forced expression of GATA-1 under tetracycline-inducible control in U937 cells, which lack GATA expression, conferred a four- to fivefold increase in IFN-γ induction of transfected HLA-E promoter constructs containing the wild type but not a mutant UIRR and increased the IFN-γ responsiveness of the endogenous HLA-E gene. Moreover, knockdown of GATA-1 in K562 cells resulted in a four- to fivefold decrease in IFN-γ-mediated induction of the endogenous HLA-E gene. GATA-1 was confirmed to bind at or near the UIRR in IFN-γ-treated K562 cells in vivo by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP). Coexpression of adenovirus E1a (AdE1a) wild-type and mutant proteins that bind to and sequester p300/CBP completely inhibited the IFN-γ response through the UIRR, while a mutant that binds Rb but not p300/CBP had a minimal effect. These results suggest that GATA-1 is recruited to the UIRR by p300/CBP and cooperates with the nearby IRR-AC to mediate an enhanced induction of HLA-E in response to IFN-γ in a cell type-restricted manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture.

U937 (ATCC CRL 1593) and K562 (ATCC CCL 243) cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.)/ml. Cells were induced with IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) at 250 U/ml for the times indicated.

The cell line U937 tet-GATA-1, exhibiting tetracycline-inducible GATA-1 expression, was generated using the plasmid pFRT/LacZeo and the Flp-in T-Rex system (Invitrogen) according to the vendor's recommended protocol. Single-cell clones were screened for lines containing a single FRT integration site. A mouse GATA-1 cDNA insert, a 1.8-kb XhoI fragment from the plasmid pXMGATA-1 (kind gift from S. Orkin), was cloned into the plasmid pcDNA5/FRT/TO and then 10 μg of the resultant plasmid, pcDNA 5/FRT/TO/mGATA, was cotransfected into 107 U937 cells along with 100 ng of pOG44 plasmid DNA. Cells were then selected with hygromycin, and those cells with the lowest basal and highest tetracyline-induced GATA-1 levels were studied.

The cell line K562-Si-GATA-1 was generated by transfection of 107 K562 cells with 15 μg of the tet repressor expression plasmid pcDNA6/TR (Invitrogen) and selected with 5 μg of Blasticidin/ml. Progeny of single-cell clones were tested for tetracycline inducibility by transient transfection of the plasmid pcDNA5/FRT/TO/CAT. The most inducible clones were then transfected with the tetracycline-regulatable small interfering RNA (SiRNA) plasmid pSUPERIOR.neo (OligoEngine, Seattle, Wash.) into which the human GATA-1 19-bp cDNA sequence GGATGGTATTCAGACTCGA and its complement TCGAGTCTGAATACCATCC had been cloned. The resultant cells were selected in G418-containing medium, and clones were screened for tetracycline-inducible GATA-1 knockdown by Western blot assay.

Preparation of CAT reporter gene constructs.

Construction of the 5′ deletion plasmids pTKCAT, pE-386, pE-193, and pE-128 was described previously (21). The 5′ deletion mutant pE-231 was generated by PCRs using a primer corresponding to −231 to −210 of the HLA-E promoter, with the addition of a HindIII site at the 5′ end of the primer. This primer was used in conjunction with an internal primer corresponding to sequences in the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene and the pE-386 plasmid as a template. PCR products were gel isolated, digested with HindIII and PstI, gel isolated again, and ligated into a similarly digested and gel-isolated pE-386 plasmid.

The pIRR-TKCAT construct was generated by subcloning the HLA-E −193 to −146 promoter fragment upstream of the thymidine kinase (TK) promoter in the pTKCAT plasmid. The pUIRR-TKCAT and pUIRR+IRR-TKCAT constructs were generated by ligating synthetic oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) corresponding to −231 to −194 and −231 to −146 of the HLA-E promoter upstream of the TK promoter. The pUIRR-6-IRR-TKCAT construct was generated by first inserting a new polyclonal region of successive HindIII, NaeI, SphI, and KpnI sites upstream of the IRR in pIRR-TKCAT. Synthetic oligonucleotides with the UIRR sequence flanked by HindIII and KpnI overhangs were then ligated into the pIRR-TKCAT plasmid to generate a 6-bp spacing. Variants of the UIRR containing point mutations were synthesized and cloned upstream of the IRR-TKCAT construct in this fashion, including the GA-to-CC and TA-to-CC mutations for pUIRR-GAmut-IRR-TKCAT and pUIRR-TAmut-IRR-TKCAT and the mutation of the potential CCAAT enhancer binding protein-β (CEBP-β) site in pUIRR-CEBPmut-IRR-TKCAT. All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (Beverly, Mass.). All constructs were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method to verify endpoints and mutated sequences.

Transient transfection and reporter gene assays.

K562 and U937 cells were transfected as described previously (21) by pulsing with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) at 250 V and 950 μF. A total of 2 × 107 K562 cells in 2 ml of complete RPMI were divided into four replicate cuvettes, each of which contained 10 μg of reporter plasmid and 1 μg of control CMV-βGAL plasmid in 50 μl. CMV-βGAL refers to an internal control plasmid with the β-galactosidase (β-Gal) gene driven by a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. A total of 4 × 107 U937 cells in 2 ml of complete RPMI were transfected with 40 μg of reporter plasmid and 4 μg of CMV-βGAL. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and then left untreated or stimulated with 250 U of IFN-γ/ml. Cells were then incubated for 40 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and harvested as previously described, and CAT and β-Gal activities were assessed according to the Promega system protocols. CAT activity was normalized to the β-Gal activity to control for transfection efficiency.

For AdE1a cotransfections, K562 cells were transfected as described above with 10 μg each of a reporter construct and an E1a expression vector with the following modifications. Cells were allowed 24 h to recover after transfection to allow E1a expression to begin before stimulation with IFN-γ. Reporter constructs included the pE-193 (containing IRR only) and pE-386 (containing both IRR and UIRR) HLA-E promoter plasmids described above. E1a expression vectors were the kind gift of Anton Krumm and Mark Groudine and included the E1a 12S wild type, the pRb-binding-deficient mutant pE1a 12S Y/H 47/928, the p300-binding-deficient mutant Δ02-36, and the base vector pUC19. Data were statistically analyzed using Bartlett's test of homogeneity, parametric analysis of variance, and Dunnet's tests performed in series as appropriate.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and gel EMSAs.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described according to the method of Dignam et al. (15). Gel mobility shift assays were carried out as described previously with the following exceptions (21). Binding reaction mixtures (22) contained 10 μg of nuclear extract, 25 fmol of double-stranded DNA probe, and 3 μg of poly(dI-dC) in a binding buffer consisting of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol (vol/vol), 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min on ice and then separated on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in a buffer consisting of 5 mM Tris (pH 7.9), 45 mM boric acid, and 0.5 mM EDTA maintained at 8°C. Antibodies used in supershift analyses included GATA-6 (Geneka Biotechnology, Montreal, Canada) and C/EBP-β, GATA-1, GATA-2, GATA-3, GATA-4, and control-matched isotype immunoglobulin G (IgG) for mouse, rat, rabbit, and goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.).

The following DNA fragments and double-stranded oligonucleotides were used as probes or competitors in gel mobility shift assays (only the sequence of the top strand is shown, and mutations are underlined): UIRR, 5′-GAGTGTGCAGAGATACCGAAACCTAAAAGTTTAAGAAC-3′; C/EBP, 5′-GCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCAG-3′; UIRR-GATAmut, 5′-GAGTGTGCAGACTGCCCGAAACCTAAAAGTTTAAGAAC-3′; UIRR-CEPBmut, 5′-GAGTGTGCAGAGATACCACTCCCTAAAAGTTTAAGAAC-3′; ρGATA, 5′-TCTGTGCAAGGCTGCAGTGAGGACAGCAAGATAAGGGCTGCTGTGTCCGGAGCCGC-3′. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Invitrogen.

ChIP assay.

A ChIP assay was performed according to the Upstate Biotechnology protocol with some modifications. K562 cells were split to 5 × 105 cells/ml the day before the assay, and a total of 2 × 108 cells in 10 ml of complete RPMI were used for each sample. Cells were incubated for 1 h with or without IFN-γ at 37°C in 5% CO2 followed by treatment with 1% formaldehyde in tightly capped flasks for 10 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed in 5 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 10 μg of pepstatin A/ml and resuspended in 200 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 10 μg of pepstatin A/ml. After a 10-min incubation on ice, cells were lysed by five 10-s pulses at 30% on a sonicator fitted with a 2-mm tip. Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and diluted with 1,800 μl of ChIP dilution buffer. An 80-μl aliquot of a protein A-agarose-salmon sperm DNA slurry was added, and the samples were rotated for 1 h at 4°C to preclean the lysates. Samples were spun at 13,000 × g and 4°C for 2 min to pellet the debris, and 1 ml of supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −20°C to use as the input (IN) control. The remaining supernatant was removed to a new tube and mixed with 10 μg of an anti-GATA-1 monoclonal antibody or control IgG of the same isotype (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rotated for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were then mixed with 60 μl of the protein A-agarose-salmon sperm mixture and rotated overnight at 4°C.

Samples were spun at 13,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min, and the supernatant was reserved at −20°C as the unbound (UN) control. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of low-salt immune complex wash (Upstate Biotechnology) followed by two washes with 1 ml of Tris-EDTA (pH 6.5). Complexes were resuspended in 250 μl of elution buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), vortexed, and rotated for 15 min at room temperature. The elution was repeated, and the second supernatant was pooled with the first to make 500 μl of immunoprecipitated (IP) sample. Five hundred microliters of each group (IN, UN, and IP) was aliquoted to new tubes, supplemented with 33.3 μl of 3 M NaCl, and heated at 65°C for 4 h with frequent vortexing to reverse the cross-links. The IN and UN samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated using ethanol. The IP samples were adjusted to 10 mM Tris (pH 6.5), 1 mM EDTA, and 40 μg of proteinase K/ml and incubated another hour at 45°C with frequent vortexing. IP samples were then extracted with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated. All samples were spun down and air dried, and the pelleted DNA was resuspended in 500 μl of sterile water followed by phenol-chloroform extraction, chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. The IP samples were resuspended in 10 μl of sterile water, and the IN and UN samples were resuspended in 50 μl of sterile water. Samples were warmed at 37°C for 10 min, and 2 μl was used for quantitation on a UV spectrophotometer.

The amount of UIRR sequence present in each sample was determined by real-time PCR using the TaqMan system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). A control reaction was carried out using primer sets specific for 18S rRNA-genomic DNA. For the UIRR, the forward primer was 5′-CCTCCCAAAGTGCTGAGATTACA-3′, the reverse primer was 5′-CCCAGCAATCAGCAGTTCTTAA-3′, and the probe sequence was 5′-TCGGTATCTCTGCACACTCTTAGAAATTAGTCCTGG-3′. For the 18S rRNA-genomic control, the forward primer was 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′, the reverse primer was 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′, and the probe sequence was 5′-TGCTGGCACCAGACTTGCCCTC-3′. Samples were run in 96-well plates using the Applied Biosystems protocol and read on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). Standard curves were generated from the input sample, and all data are expressed as fold enrichment of bound sequence relative to the input control.

RNase protection assays.

RNase protection assay conditions and probes for determining HLA-E and triose phosphate isomerase expression levels were as previously described (21). Murine GATA-1 mRNA expression was assayed under the same conditions by using a probe derived by cloning a 328-bp EcoRI fragment of the plasmid pcDNA5/FRT/GATA-1, containing 278 bp that span exon 1 and exon 2 of the GATA-1 gene, into the vector pGEM3zf(+).

RESULTS

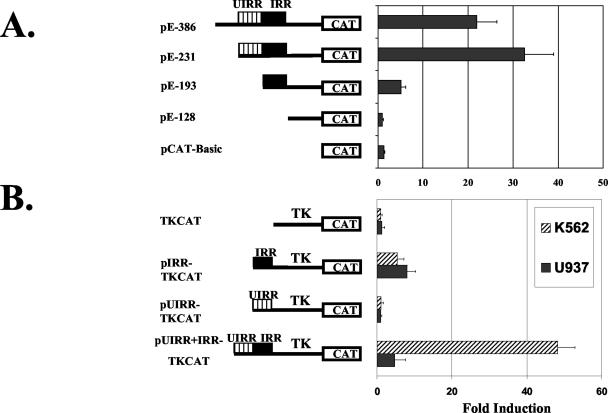

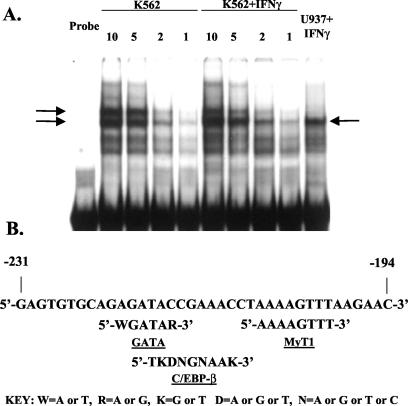

The initial characterization of the IRR of the HLA-E promoter was carried out in U937 cells (21). Investigation of the IFN-γ response in a different cell type, K562, revealed a second, upstream, IRR. This region, designated the UIRR, was further defined by promoter deletion analysis to consist of the 38 bp immediately 5′ to the IRR (Fig. 1A). The UIRR alone, unlike the IRR, was unable to confer IFN-γ inducibility to the heterologous TK promoter but was able to enhance the IRR-mediated IFN-γ induction of transcription through the TK promoter in K562 but not in U937 cells (Fig. 1B). Notably, the levels of induction through the TK promoter mediated by both the IRR and the UIRR plus IRR together were similar to that through the intact HLA-E promoter, validating the use of the TK promoter-reporter constructs for the study of the UIRR (21). However, all experiments using the TK-CAT constructs have been replicated using the intact HLA-E promoter. EMSA revealed several complexes of different mobilities that bound the UIRR, both in the presence and absence of IFN-γ in K562 cells (Fig. 2A). At least two of these were specific, as demonstrated by probe competition (data not shown) (see Fig. 5). U937 cell extracts formed only a single specific complex, similar in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (Fig. 2A). This single complex in U937 cells was of the same mobility as one of the specific complexes seen in K562 cells. There appeared to be several bands of greater mobility, but these were not competed by excess unlabeled UIRR, and so they likely represented nonspecific binding to the UIRR (data not shown) (see Fig. 5). The differential function and binding activities between K562 and U937 cells suggest a cell type-restricted factor(s) that mediates the UIRR enhancement of IRR-mediated IFN-γ induction of the HLA-E gene.

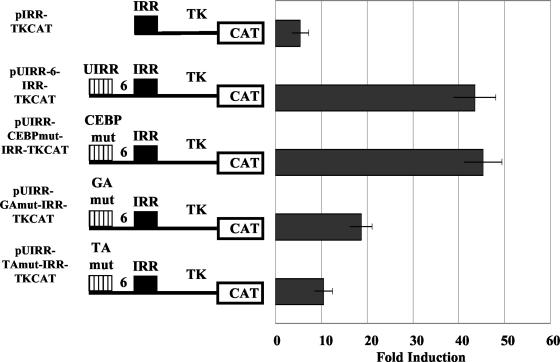

FIG. 1.

(A) Transient transfections in K562 cells with CAT reporter gene constructs containing the HLA-E promoter sequences indicated. The UIRR was localized to positions −231 to −194 relative to the transcription start site (n = 4). (B) Transient transfections of TK promoter-driven CAT constructs containing either no HLA-E sequences, the IRR sequence alone, the UIRR sequence alone, or both in K562 and U937 cells showed that the UIRR does not function in all cells and does not act as an IFN-γ response element by itself (n = 5). Data represent induction in response to IFN-γ and are displayed as the average ± the standard error of the mean.

FIG. 2.

(A) EMSA with 32P-labeled UIRR as probe and nuclear extracts from untreated and IFN-γ-treated K562 cells. Numbers above lanes refer to micrograms of nuclear extract used in the reaction mixture illustrated in that lane. Two specific complexes formed between the UIRR and extract from K562 cells (shown by arrows on left-hand side), but only one specific complex formed in U937 extracts (arrow on right side), as determined by competition with cold UIRR probe (data not shown) (see Fig. 5). (B) UIRR sequence alignment of known transcription factor consensus binding sequences motifs derived from TRANSFAC analysis. Only the MyT-1 site is a perfect match for the published consensus.

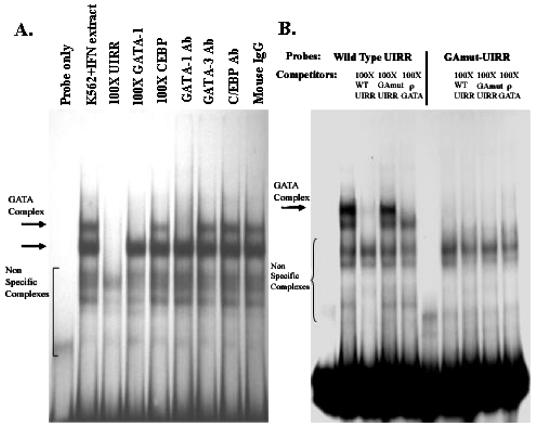

FIG. 5.

(A) EMSA with 32P-labeled UIRR probe and K562 nuclear extracts. As shown, a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled UIRR competes away two slow-moving complexes, indicated by the arrows, while excess GATA-1 sequence competes away only one of these complexes (arrow). Antibody to GATA-1 eliminates the complex, but antibodies to GATA-3, CEBP-β, or control mouse IgG have no effect. (B) EMSA with either a wild-type (WT) or a GATA mutant UIRR as probe with K562 nuclear extracts revealed that the specific complexes formed on the UIRR (indicated by arrows) require the GATA core consensus sequence. Specific competitors included wild-type UIRR and consensus GATA-1. In contrast, a UIRR probe containing a mutated GATA consensus sequence did not form any specific complex, as shown by the excess UIRR and GATA-1 cold competition at a 100-fold molar excess.

The MatInspector 2.2 computer algorithm with its predefined prediction matrices (47) was used to analyze the UIRR for known transcription factor binding sites (47). Three potential binding sites were identified, though only one was considered 100% consensus. These include sites for the GATA family transcription factors, CEBP-β, and myelin-related transcription factor-1 (MyT-1) (Fig. 2B). These families of transcription factors contain candidates for a cell type-restricted effect due to their restricted patterns of tissue distribution.

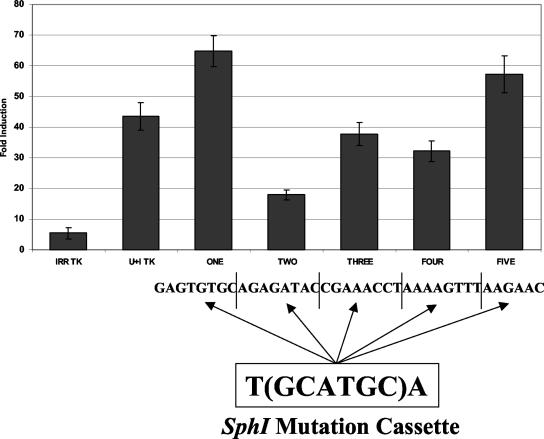

A series of linker scanning mutations were designed to test for functional regions within the UIRR. An 8-bp mutation cassette containing a core SphI restriction site was used to replace successive 8-bp segments of the UIRR, which were then cloned into the IRR-TKCAT reporter construct and used in transient transfections to screen for changes in function. Only one strong functional domain, in the second 8-bp segment containing the potential GATA binding site, was identified (Fig. 3). This region, LINKER TWO, demonstrated a 60% loss of UIRR enhancement. LINKER ONE demonstrated up to a 42% increase in UIRR enhancement over the wild type, but this was not statistically significant. Since no mutant resulted in the total loss of UIRR function, it may be that there is more than one functional domain. The promising region containing the potential GATA site was chosen for detailed analysis.

FIG. 3.

Transient transfections in K562 cells with CAT constructs containing UIRR linker scanning mutants. These constructs consisted of a UIRR mutated at the sequences indicated, a 6-bp spacer, and the IRR in front of the TK promoter. Data represent induction in response to IFN-γ and are displayed as the average of five experiments ± the standard error of the mean. Only one functional domain, at position −223 to −215, was shown to cause a twofold or greater effect on induction. *, P < 0.05.

Targeted mutations of both the GA and TA portions of the GATA core sequence were created and used in both the UIRR-IRR-TK and the native p386 HLA-E promoter contexts. Transient transfection with these mutations demonstrated that each of these dinucleotides was critical to the function of the UIRR. Mutation of the GA portion resulted in the reduction from about 44-fold induction to approximately 18-fold, while mutation of the TA portion resulted in a drop to approximately 10-fold induction (Fig. 4). Mutation of the CEBP-β consensus sequence had no effect on IFN-γ induction.

FIG. 4.

Transient transfections in K562 cells with CAT reporter constructs containing targeted mutations of the GATA and CEBP-β sites. Specific mutation of either the GA or TA half of the GATA core results in greater than twofold loss of function. Mutation of the CEBP-β core did not result in any significant change in inducibility in response to IFN-γ. Data represent induction in response to IFN-γ and are displayed as the average (n = 4) ± the standard error of the mean.

EMSA analysis was undertaken to investigate the binding of specific GATA family members to the UIRR. A synthetic oligonucleotide taken from the chicken ρ-globin gene promoter, which is known to bind GATA-1 avidly, was able to compete with complex formation on the UIRR in K562 cells, while an oligonucleotide containing a consensus CEBP-β site had no effect (Fig. 5A). Antibodies against GATA-1 were able to inhibit this same complex, while antibodies to GATA-3, CEBP-β, or control IgG were unable to bind to or inhibit any complex. In addition, mutation of the entire GATA sequence led to loss of all specific binding activities seen previously on EMSA, though several nonspecific complexes still formed on this mutant oligonucleotide (Fig. 5B). Since the UIRR GATA site is not a perfect consensus sequence (AGATAC versus WGATAR), competition with native UIRR sequence was compared to competition with the consensus ρ-globin GATA binding site. The ρ-globin GATA site competed away the putative UIRR GATA binding complex at a 25-fold molar excess compared to a 200-fold excess required for the UIRR itself (data not shown).

In order to confirm that GATA-1 associates with the endogenous UIRR in living cells, a ChIP assay was performed. There was a small but statistically significant enrichment of UIRR sequence in the anti-GATA-1 antibody IP fraction for unstimulated K562 cells compared to the input (Fig. 6). Cells treated with IFN-γ, however, showed an approximately five- to sixfold enrichment of UIRR sequence in the IP fraction compared to the IN DNA. Both unstimulated and stimulated cells also demonstrated a significant depletion of UIRR sequence in the UN fractions compared to the IN. The IgG control samples showed no significant change between IN and UN fractions, and almost no UIRR sequence was detectable in the IgG control precipitated fractions, regardless of the presence of IFN-γ. Although this assay can only localize the in vivo binding of GATA-1 to a 200-bp region containing the UIRR, the fact that there are no other minimal consensus GATA sites within the UIRR or within 400 bp in either the 5′ or 3′ direction strongly supports the conclusion that IFN-γ induces avid binding of GATA-1 to the UIRR in vivo. It is not unexpected that in in vitro EMSAs the amount of GATA-1-containing complex is equivalent in nuclear extracts from IFN-γ-treated and untreated control K562 cells, since the probe does not contain the IRR, which cooperates with and is absolutely required for the UIRR to function in transfected cells. Attempts to study binding to a probe containing both the UIRR and IRR sequences in EMSAs were technically not feasible, as is often the case with probes containing multiple factor binding sites.

FIG. 6.

ChIP in K562 cells using GATA-1-specific antibody reveals that GATA-1 associates with the UIRR in vivo after treatment with IFN-γ. IN DNA was derived from total soluble formaldehyde-cross-linked nucleosomal DNA before addition of antibody. Anti-GATA-1 or control mouse IgG of the same isotype was added, and the UIRR sequence or control 18S gene sequence content of IP chromatin fractions was analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as enrichment relative to an IN DNA value of UIRR sequence abundance set at 1.0 and are presented as the average of three experiments ± the standard error of the mean.

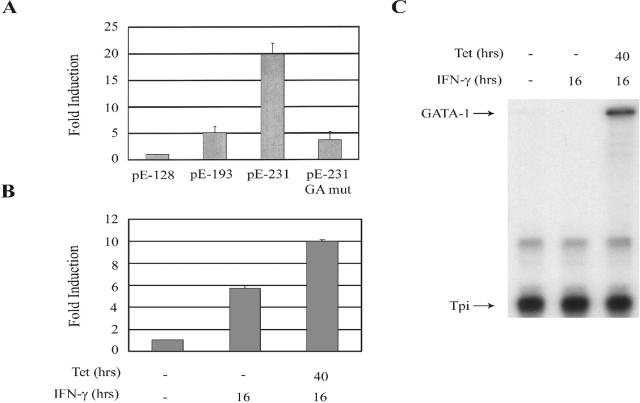

In order to confirm the importance of GATA-1 in the function of the UIRR, both gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments were carried out. U937 cells do not express amounts of GATA-1 readily detectable by RNase protection assay or Western blotting (data not shown) and do not support IFN-γ induction through the UIRR (Fig. 1). A U937 cell line which contains a GATA-1 gene under control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter was developed by utilizing the Flp-in cloning system (Invitrogen). As shown in Fig. 7, when GATA-1 was expressed in the U937 tet-GATA-1 cell line, an HLA-E promoter-driven construct containing a wild-type UIRR sequence mediated a four- to fivefold increased response to IFN-γ, compared to a construct differing only by an inactivating mutation of the core GATA sequence in the UIRR. Moreover, in U937 tet-GATA-1 cells treated with tetracycline and expressing increased GATA-1 as shown by RNase protection assay (Fig. 7C) and Western blotting (data not shown), the response of the endogenous HLA-E gene to IFN-γ was increased ∼2-fold. The diminished effect of tetracycline-induced GATA-1 expression on the IFN-γ response of the endogenous HLA-E gene compared with that of the transfected HLA-E promoter-driven CAT construct most likely reflects the fact that a small but detectable amount of GATA-1 is present in uninduced U937 tet-GATA-1 cells, in contrast to the parent U937 cell line. Since there are only two copies of the endogenous HLA-E gene per cell, while copy number quantitation showed in excess of 1,000 copies of transfected HLA-E promoter constructs per cell (data not shown), consistent with published copy number data from transient transfections (13), the small amount of GATA-1 in uninduced cells would be expected to be more limiting for the transfected gene constructs. It is also possible that differences in the chromatin associated with the endogenous compared to the transfected HLA-E promoter could account for the lesser effect of GATA-1 expression on IFN-γ induction of the endogenous gene.

FIG. 7.

GATA-1 gain of function confers enhancement of IFN-γ-mediated stimulation of HLA-E expression. (A) U937 tet-GATA-1 cells treated with IFN-γ and tetracycline were transfected with CAT reporter constructs driven by a minimal HLA-E promoter (pE-128) or HLA-E promoters that included only the IRR (pE-193), both the IRR and wild-type/UIRR (pE-231), or the IRR and a mutated UIRR (pE-231 GAmut). (B) Endogenous HLA-E expression in either untreated, IFN-γ-only treated, or IFN-γ-plus-tetracycline-treated cells was assayed by RNase protection assay and phosphorimaging quantitation. Results shown represent the average of three experiments with standard error indicated, with the control level set at 1. (C) RNase protection assay of GATA-1 expression from a representative experiment with the same control, IFN-γ-only, or IFN-γ-plus-tetracycline-treated U937 tet-GATA-1 cells shown in panel B.

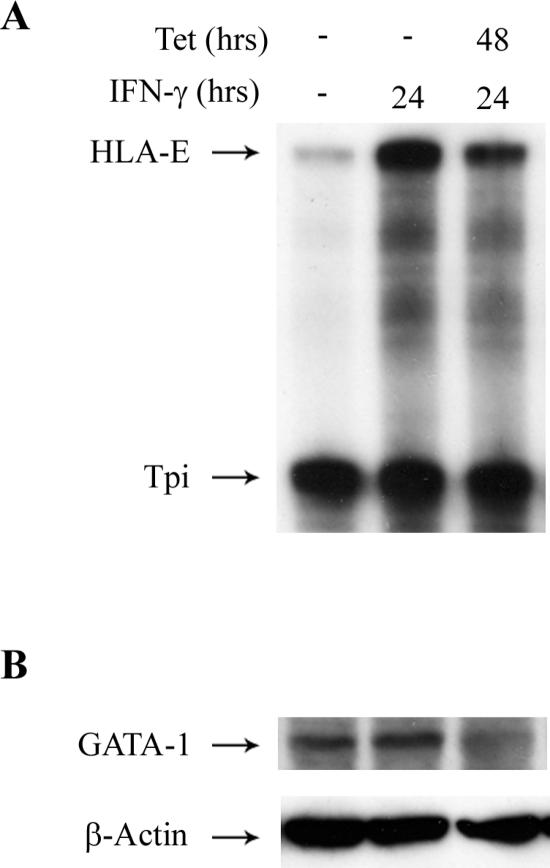

To demonstrate the effect of loss of GATA-1 on IFN-γ inducibility of the endogenous HLA-E gene, a tetracycline-inducible GATA-1 SiRNA-expressing cell line, K562 “K562 GATA-1” GATA-1, was generated. As shown in Fig. 8B, tetracycline induction of GATA-1 SiRNA resulted in a marked decrease in GATA-1, as detected by Western blotting. A concomitant fourfold decrease in IFN-γ induction of HLA-E mRNA is demonstrated in Fig. 8A and was quantitated by phosphorimager scans of corresponding RNase protection assays. The fold decrease in the IFN-γ response of the endogenous HLA-E gene in K562 cells in which GATA-1 was knocked down was about the same as the fold enhancement of the IFN-γ response mediated by the UIRR in HLA-E reporter constructs transfected into wild-type K562 cells (Fig. 1). This result suggests that, at least in the case of K562 cells, the effect of GATA-1 on the IFN-γ response is the same for transfected and endogenous HLA-E promoters.

FIG. 8.

GATA-1 knockdown in K562 cells diminishes IFN-γ response of the endogenous HLA-E gene. (A) RNase protection assay for HLA-E and triose phosphate isomerase expression in control, IFN-γ alone-, or IFN-γ-plus-tetracycline-treated K562 Si-GATA-1 cells, which are stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible GATA-1 SiRNA expression vector. (B) Western blot analysis of aliquots of the same cell treatment samples shown in panel A. The Western blot transfer membrane was first developed with α-GATA-1 antibody followed by washing and reaction with a β-actin control antibody, as indicated.

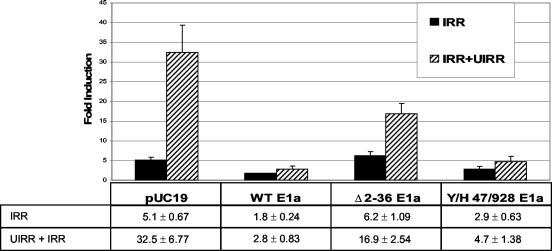

Members of the GATA family of transcription factors, including GATA-1, have been shown to bind to and transactivate through p300/CBP (6, 7). Likewise, Stat-1α is also known to bind p300/CBP, and this is believed to contribute to its ability to transactivate (48). In order to determine whether the p300/CBP coactivator is critical to the function of the UIRR, cotransfection experiments were carried out with eukaryotic expression plasmids containing either wild-type AdE1a coding sequence or a mutant, Y/H 47/98, which binds to p300/CBP but not to Rb (39), and a mutant, Δ02-36, which binds to Rb but not to p300. As shown in Fig. 9, cotransfection with either wild-type or Y/H 47/98 mutant AdE1a, but not blank expression vector, resulted in elimination of any statistically significant IFN-γ induction through the UIRR. Coexpression of the Rb-only-binding mutant, Δ02-36, resulted in a less-than-50% reduction in UIRR function and had no effect on the IRR. Coexpression of the Y/H 47/98 mutant resulted in loss of >90% of the IFN-γ induction through the UIRR, but only ∼40% of the effect through the IRR (Fig. 9). These results suggest that p300/CBP is absolutely critical to the function of the UIRR but not the IRR and further suggest that it therefore plays a key role in the cooperation between these two sequence elements that is critical for UIRR function. The data in Fig. 9 derived from cotransfection of the AdE1a mutant, Δ02-36, which binds Rb but not p300/CBP, also suggest a role for Rb in the IFN-γ response through the UIRR, albeit a less than twofold effect.

FIG. 9.

Transient cotransfection of wild-type or mutant AdE1a inhibits IFN-γ responsiveness mediated through the UIRR. For K562 cells cotransfected with empty vector, pUC19, the UIRR significantly enhanced the IFN-γ response, as shown in Fig. 1 (*, P < 0.05; n = 3). Cotransfection with wild-type E1a construct significantly decreased the IFN-γ response mediated by both the pE-386 promoter, which contains both the UIRR and the IRR, and the pE-193 promoter, which contains the IRR alone, compared to the pUC19 vector control response (**, P < 0.05; n = 3). Cotransfection with the AdE1a mutant construct, Y/H 47/928, which binds to p300/CBP but not to Rb, inhibited any statistically significant IFN-γ induction through the UIRR-containing promoter, but only partially blocked induction through the IRR-only promoter. In contrast, cotransfection with the AdE1a mutant construct Δ2-36, which binds to Rb but not to p300/CBP, did not affect IFN-γ induction through the IRR, though the UIRR response was diminished. Data represent induction in response to IFN-γ and are displayed as the average ± the standard error of the mean of three independent experiments.

It was observed in K562 cells that the uninduced levels of expression from constructs that included the UIRR were consistently lower than those constructs lacking the UIRR. This raised the possibility that the UIRR is operating, at least in part, by repressing transcriptional activity in untreated cells and that this repression is relieved by IFN-γ stimulation. CAT activities from the unstimulated pE-193 (IRR) and pE-231 (UIRR) constructs were normalized to pCAT Basic expression for comparison of the effects of the UIRR region on basal transcription from the HLA-E promoter. As shown in Table 1, basal transcription was reduced when the UIRR was included in the promoter of expression constructs in K562 cells, but it increased in U937 cells.

TABLE 1.

The UIRR mediates different effects on basal and IFN-γ-induced transcription in different cell typesa

| Cell line | Basal transcription (relative units)

|

IFN-γ-induced transcription (fold induction)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR only (pE-193) | IRR + UIRR (pE-231) | IRR only (pE-193) | IRR + UIRR (pE-231) | UIRR enhancement | |

| K562 | 29.2 ± 5.5 | 16.5 ± 3.0 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 32.5 ± 3.4 | 6.37* (32.5/5.1) |

| U937 | 25.7 ± 3.7 | 48.3 ± 4.8 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 7.9 ± 2.9 | 0.99 (7.9/8.0) |

For basal transcription, numbers represent relative units based on normalization to pCAT Basic expression levels and are presented as the average ± the standard error of the mean. UIRR-mediated enhancement of IFN-γ induction through the IRR is represented as the average increase over unstimulated samples ± the standard error of the mean. The far right column data represent the increase that the UIRR contributes to the IFN-γ response. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

The HLA-E gene is ubiquitously yet variably expressed at the mRNA level in different cell types (29, 42). Investigation in our laboratory has revealed a cell type-restricted variability in the IFN-γ inducibility of HLA-E promoter constructs. While the IRR element was found to function consistently across all cell types studied, the UIRR enhanced IFN-γ induction in one leukemic cell line (K562) but not another (U937). Extensive promoter deletion and mutation analyses identified a nonconsensus GATA binding site immediately upstream of the IRR as being crucial to the function of the UIRR, which requires the presence of the adjacent IRR to function. Extension of these transfection assays to a number of cell lines that either do or do not express one or more GATA factor family members has confirmed a close relationship between GATA expression and IFN-γ response through the UIRR (5).

In this report, it has been demonstrated that several nuclear complexes bind to the UIRR in vitro; most of these depend on the integrity of the GATA consensus sequence. One such complex in K562 cell nuclear extracts was identified as containing GATA-1 by antibody supershift and oligonucleotide competition assays. Interestingly, binding of the complex appeared to be equally strong in untreated and IFN-γ-treated nuclear extracts. Binding to the site in vivo was confirmed by ChIP assay, demonstrating that GATA-1 occupies the UIRR in living cells. Importantly, GATA-1 associates very strongly with the UIRR in vivo in the presence of IFN-γ. Given the observation that UIRR function in transfection assays is dependent on the presence of an adjacent IRR, these results suggest that there is cooperative binding of GATA-1 with Stat-1 and/or other factors in the nearby IRR-AC. This cooperativity would account for the requirement of the downstream IRR in order for the UIRR to function. It also would explain the marked increase in GATA-1 binding in vivo in IFN-γ-treated cells in which the Stat-1-containing IRR activation complex forms (21).

Based on studies with AdE1a proteins that sequester the transcriptional coactivator, p300/CBP, the major mechanism of action of the UIRR-mediated IFN-γ response, appears to involve enhanced recruitment of GATA-1 to the UIRR by p300/CBP. AdE1A species that sequester p300/CBP (Fig. 9) completely inhibited IFN-γ induction through the UIRR but only decreased the response through the IRR by ∼40%, supporting the notion that p300/CBP is critical to recruitment of GATA-1 binding to the UIRR. A recent report published during the course of these studies supports the finding that a cell type-restricted factor can modulate the response of a target gene to IFN-γ. The high-affinity receptor for IgG (Fc γRI) is constitutively expressed in myeloid cells, but its expression is rapidly induced by IFN-γ. This effect is mediated by the cooperative binding of Stat-1 and Pu.1 and their synergistic recruitment of the transcriptional coactivator p300/CBP (2). Thus, the cooperation between Stat-1 and one or more cell type-restricted transcription factors may represent a general mechanism to allow differential induction of specific genes in specific tissues by IFN-γ.

Analysis of a number of different cell lines has revealed that cells without GATA-1, but expressing other GATA factor family members, also support UIRR function. In particular, Tera-2 cells express both GATA-4 and GATA-6, both of which appear to bind the UIRR in EMSA supershift analysis (5). The observations that multiple GATA family members interact with the transcriptional coactivator p300/CBP and that Stat-1 homodimers also function, at least in part, by recruiting p300/CBP (6, 30, 48) provide a potential common framework through which these two DNA-binding factors could interact cooperatively in the HLA-E promoter in a variety of cell types. Detailed studies of the role of different GATA family members in the IFN-γ response through the UIRR in other cell types are under way.

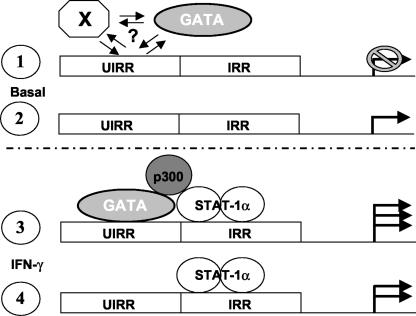

In K562 cells, it appears that in addition to the recruitment of GATA-1 to the UIRR, the mechanism of enhancement of IFN-γ-mediated induction of HLA-E transcription may involve relief of weak repression through the UIRR, as shown by basal expression of transfected HLA-E promoter-driven constructs. One possibility is that GATA-1 may compete with an as-yet-uncharacterized weak repressor factor(s) for binding to the UIRR at sequences overlapping with the GATA site. This competition would then be shifted in favor of GATA-1 binding when the immediately adjacent IRR activation complex forms in response to IFN-γ. An alternative possibility is that in K562 cells, GATA-1 binds weakly to the UIRR in the basal state and recruits a corepressor. The ability of GATA factors to interact with corepressors is well documented (14, 36, 41). Until the identity of the putative repressor is determined, this part of the mechanism remains somewhat speculative but testable. As predicted by this model, illustrated in Fig. 10, panels 1 and 3, K562 cells demonstrate basal repression and UIRR-mediated enhancement in response to IFN-γ (6.4-fold induction). In U937 cells, in which no GATA factor is expressed, there is no basal repression through the UIRR, and the total increase in transcription of the HLA-E promoter in response to IFN-γ is less, due to the lack of the cooperative interaction between GATA-1 bound to the UIRR and Stat-1α and p300/CBP bound at the IRR, as depicted in Fig. 10, panels 2 and 4.

FIG. 10.

Hypothetical model of the interactions between the UIRR-bound GATA factor(s) and IRR-bound Stat-1α in the HLA-E promoter in the presence or absence of IFN-γ. A putative negative regulator that may either bind sequences adjacent to or overlapping the GATA site or bind indirectly through the GATA factor is indicated by an X in panel 1 and represents cells in which the UIRR mediates weak repression of transcription in untreated cells. The depicted factor binding and expression patterns in panels 1 and 3 represent GATA factor-expressing cells, while panels 2 and 4 represent cells that do not express GATA factors.

The role of a GATA family factor in mediating a cell type-restricted transcriptional response in concert with constitutive factors reflects a recurrent theme of cooperativity among ubiquitous and cell type-restricted transcriptional factors in transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells. The nature of the IFN-γ response elements in the HLA-E gene promoter are illustrative of the importance of this type of cooperativity in determining the binding of both ubiquitous and restricted sequence-specific factors in transcription regulation. We have previously shown that the IRR avidly binds to two homodimers of Stat-1α in response to IFN-γ and mediates a strong transcriptional response, yet its binding of Stat-1α depends upon the presence of two half-sites, neither of which alone can bind Stat-1α in vitro and only the 5′ half-site of which confers even a very weak IFN-γ response in vivo (21). In this report, we demonstrate that a variant consensus GATA-1 binding site in the UIRR is essential for maximal IFN-γ-mediated transcriptional response of the HLA-E promoter, although the element binds only weakly to GATA-1 in vitro (∼10-fold less avidly than a canonical GATA-1 site) and mediates no response to IFN-γ in the absence of an adjacent IRR. In contrast, in the presence of the adjacent IRR, GATA-1 is recruited to the UIRR in vivo in response to IFN-γ and mediates a 6 to 7-fold increase in transcription. Since inspection of the sequences of any of the binding sites in the IRR and UIRR would not have predicted strong factor binding, it is notable that the cumulative IFN-γ transcriptional response through these two elements approaches 50-fold in some of the cell types examined.

In this report, it has been demonstrated that GATA-1 is required for a potent cell type-restricted enhancement of the transcriptional response of the HLA-E gene to IFN-γ. Preliminary studies suggest a similar role for other GATA family members, which are expressed widely in tumor cells as well as in embryonic tissues (5). HLA-E has been demonstrated to mediate negative regulation of both NK cell and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell function, and IFN-γ is frequently secreted by both NK and T cells during cellular immune reactions. The effect of IFN-γ is generally salutary to immune-mediated killing of tumor cells, in part through induction of HLA class Ia gene expression. However, recent evidence suggests that IFN-γ also can inhibit CD8+ T-cell killing of ex vivo tumor cells via induction of HLA-E (28). Therefore, GATA-1, and possibly other GATA factors, could serve as a cell type-restricted target for decreasing the relative levels of HLA-E gene expression in the presence of IFN-γ in the settings of transplantation, inflammatory states, and antitumor cellular immune therapy. Regardless of the feasibility of that specific strategy, to our knowledge this report documents the first example of differential IFN-mediated regulation of an HLA class I gene in a cell type-restricted fashion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R01-CA87496 from the National Cancer Institute to Gordon D. Ginder.

We are grateful for the assistance of Catharine W. Tucker in the preparation of the manuscript and James Roesser for providing a critical reading and helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, E. J., and P. Parham. 2001. Species-specific evolution of MHC class I genes in the higher primates. Immunol. Rev. 183:41-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aittomaki, S., J. Yang, E. W. Scott, M. C. Simon, and O. Silvennoimen. 2002. Distinct functions for signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and PU. 1 in transcriptional activation of Fcγ receptor 1 promoter. Blood 100:1078-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldrich, C. J., A. DeCloux, A. S. Woods, R. J. Cotter, M. J. Soloski, and J. Forman. 1994. Identification of a Tap-dependent leader peptide recognized by alloreactive T cells specific for a class Ib antigen. Cell 79:649-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach, E. A., M. Aguet, and R. D. Schrieber. 1997. The IFN-gamma receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:563-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett, D. 2003. Ph.D. thesis. Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

- 6.Bloebel, G. A., T. Nakajima, R. Eckner, M. Montminy, and S. H. Orkin. 1998. CREB-binding protein cooperates with transcription factor GATA-1 and is required for erythroid differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2061-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloebel, G. A., M. C. Simon, and S. H. Orkin. 1995. Rescue of GATA-1-deficient embryonic stem cells by heterologous GATA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:626-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braud, V. M., D. S. J. Allan, C. A. O'Callaghan, K. Soderstrom, A. D'Andrea, G. S. Ogg, S. Lazetic, N. T. Young, J. I. Bell, J. H. Phillips, L. L. Lanier, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors. Nature 391:795-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braud, V. M., D. S. J. Allan, D. Wilson, and A. J. McMichael. 1997. TAP- and tapasin-dependent HLA-E surface expression correlates with the binding of an MHC class I leader peptide. Curr. Biol. 8:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braud, V. M., E. Y. Jones, and A. J. McMichael. 1997. The human major histocompatibility complex class Ib molecule HLA-E binds signal sequence-derived peptides with primary anchor residues at positions 2 and 9. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1164-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briegel, K., K. C. Lim, C. Plank, H. Beug, J. D. Engel, and M. Zenke. 1993. Ectopic expression of a conditional GATA-2/estrogen receptor chimera arrests erythroid differentiation in a hormone-dependent manner. Genes Dev. 7:1097-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, E., R. W. Karr, J. P. Frost, T. A. Gonwa, and G. D. Ginder. 1986. Gamma interferon and 5-azacytidine cause transcriptional elevation of class I major histocompatibility complex gene expression in K562 leukemia cells in the absence of differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:1698-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper, M. J., M. Lippa, J. M. Payne, G. Hatzivassiliou, E. Reifenberg, B. Fayazi, J. Perales, L. J. Morrison, D. Templeton, R. L. Piekarz, and J. Tan. 1997. Safety-modified episomal vectors for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6450-6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deconinck, A. E., P. E. Mead, S. G. Tevosian, J. D. Crispino, S. G. Katz, L. I. Zon, and S. H. Orkin. 2000. FOG acts as a repressor of red blood cell development in Xenopus. Development 127:2031-2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans, T., and G. Felsenfeld. 1989. The erythroid-specific transcription factor Eryfl: a new finger protein. Cell 58:877-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman, R. L., and G. R. Stark. 1985. α-Interferon-induced transcription of HLA and metallothionein genes containing homologous upstream sequences. Nature 314:637-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita, T., Y. Kimura, M. Miyamoto, E. L. Barsoumian, and T. Taniguchi. 1989. Induction of endogenous IFN-alpha and IFN-beta genes by a regulatory transcription factor, IRF-1. Nature 337:270-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George, K., M. Leonard, M. Roth, K. Liew, D. Koussis, F. Grosveld, and J. D. Engel. 1994. Embryonic expression and cloning of the murine GATA-3 gene. Development 120:2673-2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh, K. C., S. J. Haque, and B. R. Williams. 1999. p38 MAP kinase is required for STAT1 serine phosphorylation and transcriptional activation induced by interferons. EMBO J. 18:5601-5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafson, K. S., and G. D. Ginder. 1996. Interferon-gamma induction of the human leukocyte antigen-E gene is mediated through binding of a complex containing STAT1-alpha to a distinct interferon-gamma-responsive element. J. Biol. Chem. 271:20035-20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakem, R., P. LeBouteiller, A. Jezo-Brem, K. Harper, D. Campese, and F. Lemonnier. 1991. Differential regulation of HLA-A3 and HLA-B7 MHC class I genes by IFN is due to two nucleotide differences in their IFN response sequences. J. Immunol. 147:2384-2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumatori, A., D. Yang, S. Suzuki, and M. Nakamura. 2002. Cooperation of STAT-1 and IRF-1 in interferon-gamma-induced transcription of the gp91phox gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9103-9111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurepa, Z., C. A. Hasemann, and J. Forman. 1998. Qa-1b binds conserved class I leader peptides derived from several mammalian species. J. Exp. Med. 188:973-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, N., M. Llano, M. Carretero, A. Ishitiani, F. Navarro, M. Lopez-Botet, and D. Geraghty. 1998. HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5199-5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy, D. E., D. S. Kessler, R. Pine, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1989. Cytoplasmic activation of ISGF3, the positive regulator of interferon-alpha-stimulated transcription, reconstituted in vitro. Genes Dev. 3:1362-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lew, D. J., T. Decker, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1989. Alpha interferon and gamma interferon stimulate transcription of a single gene through different signal transduction pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:5404-5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malmberg, K., V. Levitsky, H. Norell, C. de Matos, M. Carlsten, K. Schedvins, A. Moretta, H. Rabbani, A. Moretta, K. Soderstrom, J. Levitskaya, and R. Kiessling. 2002. IFN-gamma protects short-term ovarian carcinoma cell lines from CTL lysis via a CD94/NKG2A-dependent mechanism. J. Clin. Investig. 110:1515-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marin, R., F. Ruiz-Cabello, S. Pedrinaci, R. Mendez, P. Jimenez, D. Geraghty, and F. Garrido. 2003. Analysis of HLA-E expression in human tumors. Immunogenetics 54:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molkentin, J. D. 2000. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6: ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38949-38952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Callaghan, C. A., and J. I. Bell. 1998. Structure and function of the human MHC class Ib molecules HLA-E, HLA-F and HLA-G. Immunol. Rev. 163:129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersson, E., R. Holmdahl, G. W. Butcher, and G. Hedlund. 1999. Activation and selection of NK cells via recognition of an allogeneic, non-classical MHC class I molecule, RT1-E. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:3663-3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shuai, K., C. Schindler, V. R. Prezioso, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1992. Activation of transcription by IFN-gamma: tyrosine phosphorylation of a 91-kD DNA binding protein. Science 258:1808-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speiser, D. E., M. J. Pittet, D. Valmori, R. Dunbar, D. Rimoldi, D. Lienard, H. R. MacDonald, J. C. Cerottini, V. Cerundolo, and P. Romero. 1999. In vivo expression of natural killer cell inhibitory receptors by human melanoma-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 190:775-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark, G. R., I. M. Kerr, B. R. G. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and R. D. Schrieber. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svensson, E. C., G. S. Huggins, F. B. Dardik, C. E. Polk, and J. M. Leiden. 2000. A functionally conserved N-terminal domain of the friend of GATA-2 (FOG-2) protein represses GATA4-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20762-20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai, S. F., D. I. Martin, L. I. Zon, A. D. D'Andrea, G. G. Wong, and S. H. Orkin. 1989. Cloning of cDNA for the major DNA-binding protein of the erythroid lineage through expression in mammalian cells. Nature 339:446-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vegh, Z., P. Wang, F. Vanky, and E. Klein. 1993. Increased expression of MHC class I molecules on human cells after short time IFN-gamma treatment. Mol. Immunol. 30:849-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, H., Y. Rikitake, M. Carter, Y. Yaciuk, S. Abraham, B. Zerler, and E. Moran. 1993. Identification of specific adenovirus E1A N-terminal residues critical to the binding of cellular proteins and to the control of cell growth. J. Virol. 67:476-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waring, J. F., J. E. Radford, L. J. Burns, and G. D. Ginder. 1995. The human leukocyte antigen A2 interferon-stimulated response element consensus sequence binds a nuclear factor required for constitutive expression. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12276-12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watamoto. K., M. Towatari, Y. Ozawa, Y. Miyata, M. Okamoto, A. Abe, T. Naoe, and H. Saito. 2003. Altered interaction of HDAC5 with GATA-1 during MEL cell differentiation. Oncogene 22:9176-9184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei, X., and H. Orr. 1990. Differential expression of HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G transcripts in human tissue. Hum. Immunol. 29:131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss, M. J., G. Keller, and S. H. Orkin. 1994. Novel insights into erythroid development revealed through in vitro differentiation of GATA-1 embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 8:1184-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss, M. J., and S. H. Orkin. 1995. GATA transcription factors: key regulators of hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 23:99-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen, Z., Z. Zhong, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1995. Maximal activation of transcription by STAT1 and STAT3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell 82:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams, T. M. 2001. Human leukocyte antigen gene polymorphism and the histocompatibility laboratory. J. Mol. Diagn. 3:98-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wingender, E., X. Chen, R. Hehl, H. Karas, I. Leibich, V. Matys, T. Meinhardt, M. Pruss, I. Reuter, and F. Schacherer. 2000. TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:316-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, J., U. Vinkmeier, W. Gu, D. Chakravarti, C. Horvath, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1996. Two contact regions between Stat1 and CBP/p300 in interferon-gamma signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15092-15096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]