Abstract

Portal hypertension causes portosystemic shunting along the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in gastrointestinal varices. Rectal varices and their bleeding is a rare complication, but it can be fatal without appropriate treatment. However, because of its rarity, no established treatment strategy is yet available. In the setting of intractable rectal variceal bleeding, a transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunt can be a treatment of choice to enable portal decompression and thus achieve hemostasis. However, in the case of recurrent rectal variceal bleeding despite successful transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunt, alternative measures to control bleeding are required. Here, we report on a patient with liver cirrhosis who experienced recurrent rectal variceal bleeding even after successful transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunt and was successfully treated with variceal embolization.

Keywords: Ectopic varices, Rectal varices, Transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunt, Embolization, Variceal bleeding

Core tip: In intractable rectal variceal bleeding, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been shown to be an effective method for hemostasis. However, in recurrent bleeding even after successful TIPS, no solid therapeutic approach is available, and various measures should be tried according to clinical conditions. This case report reviews the traditional role of TIPS in rectal variceal bleeding, but also implies the role of variceal embolization in recurrent rectal variceal bleeding even after successful TIPS.

INTRODUCTION

Portal hypertension is caused by various etiologies. Liver cirrhosis is the most common[1]; however, any other cause that can alter portal blood flow and increase resistance might be a contributing factor[2]. Portal hypertension involves the vascular system and causes varices in any part of the gastrointestinal tract as the result of dilated collateral veins[3]. In particular, rectal varices arise from communication between superior hemorrhoidal and the middle or inferior hemorrhoidal veins[4].

Rectal variceal bleeding is a rare complication in patients with portal hypertension and has the potential for massive life-threatening hemorrhage[5]. Currently, various treatment options are available for its management, including endoscopic intervention, surgery, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and angiographic embolization; however, no established therapy is recognized[1,3,6,7]. In the setting of intractable rectal variceal bleeding, TIPS has been reported as an effective method because hemostasis can be achieved by portal decompression[8-10]. First introduced by Katz et al[11], TIPS has achieved complete hemostasis without recurrence and is recommended for intractable rectal variceal bleeding.

However, in the case of recurrent bleeding even after successful TIPS, there is no standardized alternative therapeutic approach. Here we report a case of a woman who experienced recurrent rectal variceal bleeding after successful TIPS, but was successfully treated with variceal embolization.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old woman with alcoholic liver cirrhosis was first admitted to another hospital for hematochezia that had persisted for 2 wk. After a diagnostic workup, rectal variceal bleeding was identified, and TIPS was performed for hemostasis. However, bleeding continued even after successful TIPS, and she was referred to our institute for further management.

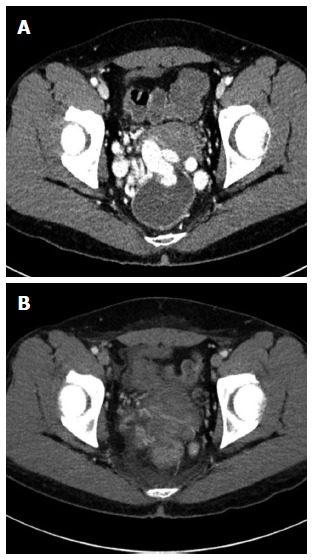

On arrival at the emergency room, she showed a pale conjunctiva and splenomegaly without hepatomegaly. Her heart rate was 88 beats/min and her blood pressure was 111/73 mmHg. Digital rectal examination showed fresh blood. Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin 8.1 g/dL, platelet 45000/μL, prothrombin time 1.28 international normalized ratio, aspartate/alanine aminotransferase 31/16 IU/L, total bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, and serum albumin 2.8 g/dL. Abdominal ultrasonography showed that TIPS was patent. Abdominopelvic computed tomography showed huge and tortuous rectal varices and a cirrhotic liver with splenomegaly (Figure 1A). After admission, rectal variceal bleeding continued, and the patient’s hemoglobin level decreased to 7.3 g/dL.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography. A: Abdominopelvic computed tomography. Huge rectal varices protrude into the rectum; B: Follow-up computed tomography at 5 d after variceal embolization. Obliteration of rectal varices is identified.

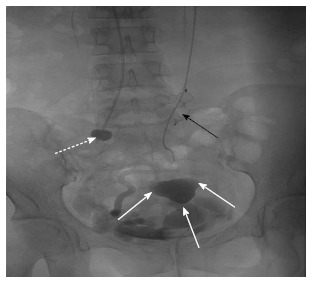

The patient underwent sigmoidoscopic examination, which showed rectal variceal bleeding without another focus of bleeding (Figure 2). Although endoscopic sclerotherapy or surgical removal of varices was initially considered for achieving hemostasis, the limited effects of these treatment methods were anticipated owing to large varices size and thrombocytopenia. Thus, interventional variceal embolization was attempted. Angiography via jugular approach revealed an enlarged inferior mesenteric vein with a hepatofugal flow. For interventional hemostasis, the right internal iliac vein was occluded using a 10-mm occlusion balloon (Boston Scientific, Watertown, MA), and a 20-mm vascular plug (St. Jude Medical, Saint Paul, MN) was applied to the inferior mesenteric vein to control the rapid venous flow. Afterward, a 4F glide catheter (Terumo, Somerset, NJ) was advanced to the rectal varices, and Gelfoam (Pharmacia and Upjohn Company, Kalamazoo, MI) embolization was successfully performed (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Sigmoidoscopic examination. Huge rectal varices protrude into the rectum, with bleeding.

Figure 3.

Angiography. After applying an occlusion balloon (white dotted arrow) and vascular plug (black arrow), variceal embolization was successfully performed using a Gelfoam pledget (white arrow).

After successful obliteration of the rectal varices, no further bleeding occurred, and after a transfusion of 2 U of red blood cells, the patient’s hemoglobin level stabilized at 9.5 g/dL. Follow-up computed tomography, which was performed 5 d after the procedure, showed successfully obliterated rectal varices (Figure 1B). At 3 mo’ follow-up, the patient’s hemoglobin level increased to 12.7 g/dL, and she reported no further rectal bleeding.

DISCUSSION

Portal hypertension is defined as increased hepatic venous pressure gradient of more than 5 mmHg[12]. It is most commonly caused by liver cirrhosis, although any other etiology that influences vascular resistance or blood flow might be a cause[2]. It eventually induces portosystemic shunt, leading to the formation of gastrointestinal varices. Among gastrointestinal varices, gastric and esophageal varices are the most common and are reported in up to 50% in patients with liver cirrhosis. However, gastrointestinal varices can occur in every part of the gastrointestinal tract and are referred as ectopic varices. This term was first used to describe dilated portosystemic collateral veins in unusual sites other than the esophagus and stomach[1,6].

Among ectopic varices, rectal varices refer to the dilation of portosystemic collateral veins in the rectum. Occasionally, the terms rectal varices and hemorrhoids are used indiscriminately; however, such a misdiagnosis could lead to fatal bleeding and should be diagnosed with caution[13]. Hemorrhoids arise from a prolapsed rectal venous plexus and are vascular cushions of venous and arterial anastomoses. In contrast, rectal varices are defined as variceal veins that are above the anal verge, larger than 4 cm, dark blue, and do not prolapse into the proctoscope during examination[14]. Rectal varices are associated with portal hypertension and are connections of the portal systemic and systemic circulation[6,15].

To date, the prevalence of rectal varices in patients with portal hypertension varies from 3.6% to 78%[7,16]. Its prevalence is increasing because of the development of various diagnostic techniques, including computed tomography imaging, endoscopy, and angiography. However, there is a wide disparity in rectal variceal diagnoses because of varying etiologies and interobserver variability[1]. Although rectal variceal bleeding accounts only for 1% to 5% of all variceal bleeding[1,6,17], it could be a life-threatening medical emergency that needs close attention and timely intervention[5,7,13]. Various approaches to treat rectal variceal bleeding have been suggested and are in practice, including medical, endoscopic, surgical, and angiographic intervention, and TIPS. However, because rectal varices are often difficult to locate and their incidence is low, no randomized controlled trial has compared efficacy among treatment modalities. Therefore, in the setting of rectal variceal bleeding, the standard therapeutic intervention is still a controversy, and treatment is mainly based on the physician’s experience[1,7].

Volume resuscitation and red blood cell transfusion should be an initial treatment step in rectal variceal bleeding. Medical treatment might then be attempted; however, unlike as in gastroesophageal or colonic variceal bleeding, no solid evidence is available for the routine use of somatostatin analogs, including octreotide[1,3]. For hemostasis of the primary bleeding lesion, some physicians prefer an endoscopic approach, including endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and endoscopic band ligation for initial management[18-20] because they are early applicable measures that can diagnose and treat at the same time. However, endoscopic treatment is not always applicable and often has potentially serious adverse effects, including a wide defect in the varix after band sloughing in endoscopic band ligation or incomplete obliteration resulting from sclerosant dilution in EIS, especially in large varices; as a result, an alternative approach should be used[3]. Surgical management, including portosystemic shunting, ligation, and underrunning suturing, could also be considered in patients with a preserved hepatic reserve and extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis[1,3,6]. However, surgery is associated with an increased operative risk from underlying liver disease and potential hepatic failure and so is not recommended in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis and deteriorated liver function.

In intractable rectal variceal bleeding, TIPS is currently recommended. Katz et al[11] first reported TIPS as an effective method to control intractable rectal variceal bleeding. Shibata et al[21] presented a series of 12 patients with ectopic variceal bleeding who achieved complete hemostasis after being treated with TIPS only. However, incomplete hemostasis after TIPS, mostly from shunt dysfunction, was also reported[9,22,23]. To minimize rebleeding after TIPS, concomitant variceal embolization during TIPS formation has been proposed by Vangeli et al[23] In their report, the authors reported that concomitant variceal embolization could reduce the risk of rebleeding because complete hemostasis could not be achieved in every individual undergoing TIPS. However, Vidal et al[22] and Kochar et al[9] suggested that routine variceal embolization should not be recommended because the risk of rebleeding after TIPS was not high and complete variceal obliteration was not always possible but potentially has an increased risk of inherent procedure-related complications.

Because endoscopic and surgical approaches have their own limitations in managing variceal bleeding from large rectal varices in patients with limited hepatic reserve, angiographic embolization has been attempted in several cases and is considered a relatively safe and effective method[8-10,24,25]. Table 1 summarizes case reports of successful variceal embolization of rectal variceal bleeding. Variceal embolization is usually performed via a transhepatic approach, but can be applied in accordance with clinical and anatomical situations and is feasible even in patients with poor liver function. Hemostasis by variceal embolization is achieved by occluding the vein that feeds the bleeder, and various embolization materials are used, including coils, Gelfoam, thrombin, collagen, autologous blood clot, and ethanol[1,3]. The advantage of hemostasis by variceal embolization is that diagnosis of the active bleeder and treatment can be done at the same time with minimal invasiveness.

Table 1.

Case reports of successful embolization for the hemostasis of rectal variceal bleeding

| Ref. | Publication year | Age (yr)/sex | History of rectal variceal bleeding | Previous treatment | Approach | Initial treatment | Complications |

| Hashimoto et al[26] | 2013 | 56/M | Yes | EIS, EVL, surgery | Paraumbilical vein | EVL, EIS, surgery | None |

| Arai et al[27] | 2013 | 70/M | None | None | Ileocolic vein | None | None |

| Okada et al[25] | 2012 | 77/F | Yes | None | Portal vein | EVL, surgery | None |

| Ibukuro et al[28] | 2009 | 65/M | None | None | Paraumbilical vein | None | None |

| Okazaki et al[24] | 2006 | 77/F | None | None | Portal vein | None | None |

| Kimura et al[29] | 1997 | 76/F | None | None | Femoral vein | None | None |

EIS: Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; EVL: Endoscopic varix ligation; F: Female; M: Male.

In our case, TIPS was performed as an initial measure to control intractable rectal variceal bleeding. However, TIPS insufficiently achieved complete hemostasis even with a patent shunt. Endoscopic and surgical approaches were not feasible because of the large rectal varices and limited hepatic reserve, but variceal embolization achieved successful hemostasis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report showing the usefulness and safety of variceal embolization for the successful hemostasis of recurrent rectal variceal bleeding, even after the successful TIPS. Further case series or meta-analyses are required to establish a standard treatment strategy for hemostasis of recurrent rectal variceal bleeding after TIPS by comparing the efficacy and safety of medical, surgical, and interventional approaches, including variceal embolization.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 39-year-old female with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis presented with hematochezia.

Clinical diagnosis

Pale conjunctiva and splenomegaly without hepatomegaly. Fresh blood in digital rectal examination.

Differential diagnosis

Hemorrhoid, lower or upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Laboratory diagnosis

Hemoglobin 8.1 g/dL, platelet 45000/μL, prothrombin time 1.28 international normalized ratio, aspartate/alanine aminotransferase 31/16 IU/L, total bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, and serum albumin 2.8 g/dL.

Imaging diagnosis

Abdominopelvic computed tomography scan showed huge and tortuous rectal varices and a cirrhotic liver with splenomegaly.

Treatment

The patient was treated with variceal embolization.

Related reports

Due to the rarity of intractable rectal variceal bleeding, the treatment is not very well understood and the treatment is mostly based on clinical situation and physician’s decision.

Term explanation

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is used for variceal bleeding and ascites. TIPS is done by creating a channel between the hepatic vein and the intrahepatic portion of the portal vein.

Experiences and lessons

This case report reviews the traditional role of TIPS in rectal variceal bleeding, but also implies the role of variceal embolization in recurrent rectal variceal bleeding even after successful TIPS.

Peer review

This case reviews the role of TIPS and variceal embolization in recurrent rectal variceal bleeding even after successful TIPS.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 26, 2014

First decision: June 18, 2014

Article in press: July 22, 2014

P- Reviewer: Watanabe M, Sohn JH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322–334. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-Pagán JC, Gracia-Sancho J, Bosch J. Functional aspects on the pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;57:458–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almadi MA, Almessabi A, Wong P, Ghali PM, Barkun A. Ectopic varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takagi S, Kinouchi Y, Takahashi S, Shimosegawa T. Hemodynamics of rectal varices. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:611–612. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1853-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khaliq A, Dutta U, Kochhar R, Chalapathi A, Singh K. Massive lower gastrointestinal bleed due to rectal varix. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7 Suppl 1:S57–S59. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154–1158. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshino K, Imai Y, Nakazawa M, Chikayama T, Ando S, Sugawara K, Hamaoka K, Inao M, Oka M, Mochida S. Therapeutic strategy for patients with bleeding rectal varices complicating liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:1088–1094. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fantin AC, Zala G, Risti B, Debatin JF, Schöpke W, Meyenberger C. Bleeding anorectal varices: successful treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) Gut. 1996;38:932–935. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.6.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kochar N, Tripathi D, McAvoy NC, Ireland H, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. Bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhosis: the role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:294–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ory G, Spahr L, Megevand JM, Becker C, Hadengue A. The long-term efficacy of the intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for the treatment of bleeding anorectal varices in cirrhosis. A case report and review of the literature. Digestion. 2001;64:261–264. doi: 10.1159/000048871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz JA, Rubin RA, Cope C, Holland G, Brass CA. Recurrent bleeding from anorectal varices: successful treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1104–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann RJ, Fisher RL, Conn HO, Atterbury CE, Glickman M. Portal pressure, presence of gastroesophageal varices and variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1985;5:419–424. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batoon SB, Zoneraich S. Misdiagnosed anorectal varices resulting in a fatal event. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3076–3077. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganguly S, Sarin SK, Bhatia V, Lahoti D. The prevalence and spectrum of colonic lesions in patients with cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1995;21:1226–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinshel E, Chen W, Falkenstein DB, Kessler R, Raicht RF. Hemorrhoids or rectal varices: defining the cause of massive rectal hemorrhage in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:744–747. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)91132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe N, Toyonaga A, Kojima S, Takashimizu S, Oho K, Kokubu S, Nakamura K, Hasumi A, Murashima N, Tajiri T. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: Results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biecker E. Portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding: diagnosis, prevention and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5035–5050. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojima T, Onda M, Tajiri T, Kim DY, Toba M, Masumori K, Umehara M, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, et al. [A case of massive bleeding from rectal varices treated with endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL)] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1996;93:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeniya A, Odashima M, Takahashi H, Ohkubo S, Masamune O. [A case of rectal varices treated with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;94:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boursier J, Oberti F, Reaud S, Person B, Maurin A, Cales P. [Bleeding from rectal varices in a patient with severe decompensated cirrhosis: success of endoscopic band ligation. A case report and review of the literature] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:783–785. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata D, Brophy DP, Gordon FD, Anastopoulos HT, Sentovich SM, Bleday R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1581–1585. doi: 10.1007/BF02236211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal V, Joly L, Perreault P, Bouchard L, Lafortune M, Pomier-Layrargues G. Usefulness of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:216–219. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vangeli M, Patch D, Terreni N, Tibballs J, Watkinson A, Davies N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding ectopic varices--treatment with transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) and embolisation. J Hepatol. 2004;41:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okazaki H, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Nakamura S, Wada T, Yamamori K, Machida A, Kadouchi K, Tamori A, Tominaga K, et al. Successful treatment of giant rectal varices by modified percutaneous transhepatic obliteration with sclerosant: Report of a case. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5408–5411. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i33.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada M, Nakashima Y, Kishi T, Matsunaga N, Ishikawa T, Tamesa T, Yonezawa T. Percutaneous transhepatic obliteration for massive variceal rectal bleeding. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:355–358. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto N, Akahoshi T, Kamori M, Tomikawa M, Yoshida D, Nagao Y, Morita K, Kayashima H, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, et al. Treatment of bleeding rectal varices with transumbilical venous obliteration of the inferior mesenteric vein. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:e134–e137. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828031ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arai H, Kobayashi T, Takizawa D, Toyoda M, Takayama H, Abe T. Transileocolic vein obliteration for bleeding rectal varices with portal thrombus. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000348761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibukuro K, Kojima K, Kigawa I, Tanaka R, Fukuda H, Abe S, Tobe K, Tagawa K. Embolization of rectal varices via a paraumbilical vein with an abdominal wall approach in a patient with massive ascites. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1259–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura T, Haruta I, Isobe Y, Ueno E, Toda J, Nemoto Y, Ishikawa K, Miyazono Y, Shimizu K, Yamauchi K, et al. A novel therapeutic approach for rectal varices: a case report of rectal varices treated with double balloon-occluded embolotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:883–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]