Abstract

In the last decade, the emergence of high throughput screening has enabled the development of novel drug therapies and elucidated many complex cellular processes. Concurrently, the mechanobiology community has developed tools and methods to show that the dysregulation of biophysical properties and the biochemical mechanisms controlling those properties contribute significantly to many human diseases. Despite these advances, a complete understanding of the connection between biomechanics and disease will require advances in instrumentation that enable parallelized, high throughput assays capable of probing complex signaling pathways, studying biology in physiologically relevant conditions, and capturing specimen and mechanical heterogeneity. Traditional biophysical instruments are unable to meet this need. To address the challenge of large-scale, parallelized biophysical measurements, we have developed an automated array high-throughput microscope system that utilizes passive microbead diffusion to characterize mechanical properties of biomaterials. The instrument is capable of acquiring data on twelve-channels simultaneously, where each channel in the system can independently drive two-channel fluorescence imaging at up to 50 frames per second. We employ this system to measure the concentration-dependent apparent viscosity of hyaluronan, an essential polymer found in connective tissue and whose expression has been implicated in cancer progression.

I. INTRODUCTION

Recent advances in imaging technology and computational analysis have facilitated large-scale quantitative biology studies through the development of high throughput screening (HTS). In the last decade, the impact of HTS on biology has been significant1 in enabling the development of novel drug therapies,2–4 and elucidating complex cellular processes including differentiation,5 division,6 and migration.7 Concurrently, the mechanobiology community has developed tools and methods to show that the dysregulation of biophysical properties and biochemical mechanisms that control them contribute significantly to many human diseases such as arthritis,8,9 atherosclerosis,10 cystic fibrosis,11,12 blood coagulopathies,13,14 and cancer.15–17 Despite these findings, a complete understanding of the connection between biomechanics and disease will require advances in instrumentation that enable parallelized, high throughput assays capable of probing complex signaling pathways, studying biology in physiologically relevant conditions, and capturing specimen and mechanical heterogeneity. Such a system would transform the state of the art, placing the onus of experimental design on the targeted hypothesis, rather than on the methodology, workflow, and the time needed to execute such a complicated experiment.

Traditional biophysical instruments and methodologies are unable to provide parallelized, high throughput investigation of biomechanical systems. For example, bulk rheological devices like cone and plate (CAP) require large sample volumes and long duration testing and therefore lack scalability to parallelized, high throughput studies. Similarly, even small volume techniques such as atomic force microscopy and optical and magnetic tweezers use designs that acquire data on samples in a serial fashion. Thus, although providing great detail, these techniques are limited in the number of treatments or conditions that can be measured before losing specimen viability. Compounding these issues is the uncontrollable heterogeneity commonly found in single cell or material measurements18,19 which demands not only intellectual attention20 but also imposes the challenge of collecting sufficient data for generating statistically sound conclusions. Recent efforts to increase the throughput of mechanical measurements21–23 have addressed the need of capturing specimen and mechanical heterogeneity, but still acquire data across experimental conditions serially.

In the present work, building on our previous technology,24 we present an array high throughput (AHT) microscopy system that enables parallelized, high throughput mechanical measurements of cells and biomaterials. The AHT system implements passive microrheology—a well-established technique that has been successful in characterizing the mechanical properties of a wide range of biological specimens, including mucus,25 fibrin,26 and cells,27,28 and in particular, the soft intracellular cytoplasm of cells.29,30 Additionally, passive microrheology has been noted for holding promise as a high throughput methodology.31 Here, we first describe the AHT system design, including discussion of the imaging and mechanical subsystems and associated custom software. We then demonstrate that the AHT system can accurately measure the viscosity of Newtonian fluids. Finally, we use the AHT microscope to study the rheology of hyaluronan (HA) solutions as a function of concentration. Given the role of HA in cancer biology,32–34 measurements such as these may be useful in studying the biophysical steps in tumor progression and metastasis. The functionality of the AHT system is parallelized across twelve independent objectives and imaging channels through barrier synchronization, and automated microscopy events such as light-emitting diode (LED) illumination and camera triggering are tightly synchronized within a channel by a custom operating system. The AHT system can evaluate the biophysical properties of soft materials almost two orders of magnitude faster than conventional instruments.

II. ARRAY MICROSCOPE: DESIGN, HARDWARE, AND SOFTWARE

The AHT system was designed to implement passive microrheology, a well-established methodology that uses the thermal deflection of micron-scale particles by energy kT (where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature of the molecular environment) to estimate the mechanical response functions for the surrounding material.35 By measuring the displacement of fluorescent particles that have been embedded in a material, the mean-squared displacement (MSD) is calculated using

| (1) |

where τ is the time lag, or timescale. The mechanical response is quantified as the complex, frequency-dependent shear modulus G∗(ω) = G′(ω) + iG″(ω), where G′(ω) and G″(ω) correspond, respectively, to the elastic and viscous contributions of the viscoelastic material. Using the ensemble averaged MSD, the linear mechanical response of a material is given by the generalized Stokes-Einstein relation (GSER)35

| (2) |

where a is the particle radius, ℑ denotes the Fourier transform, and ω is the angular frequency, related to the timescale through ω = 1/τ. The complex shear modulus G*(ω) is related directly to the complex viscosity as .

The AHT system is composed of several hardware and software subsystems: an optics and imaging block (Sec. II A), XYZ mechanical translation (Secs. II B and III A), event synchronization (Sec. II C), and parallel-enabled data collection and analysis (Sec. II D).

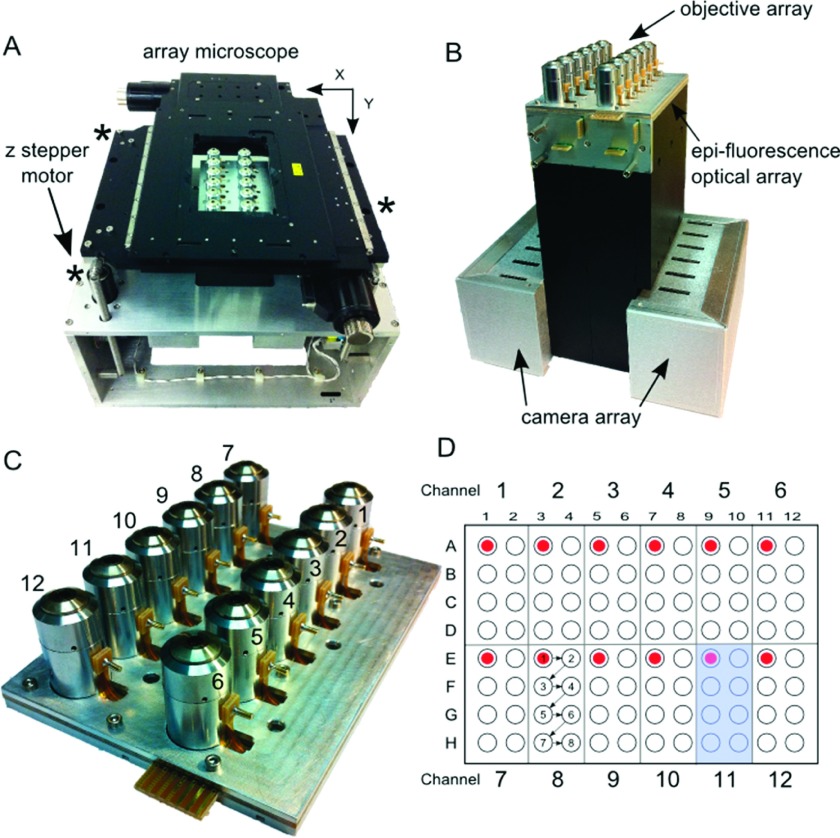

Motivated by the need for parallelized, high throughput characterization and time-course mechanical measurements, we engineered the AHT system to comply with the Society for Biomolecular Screening (SBS) standard geometry for high throughput multiwell plates.36 To lie within a multiwell plate footprint, twelve independent optical systems were arranged in a 2 × 6 array, each containing a 40 X objective (Universe Kogaku America) with an estimated NA of 0.45 and a maximum working distance of 650 μm, two epi-fluorescence illumination modes, and a remote-head camera (Point Grey, Inc.) (Figures 1(a)–1(c)). To enable each optics channel to have independent control over its plane of focus at the expense of lower numerical aperture, we retrofitted a liquid lens (Parrot Varioptic)33 into each objective, an aspect of the system we will address more fully in a future publication. A commercially available translation stage (Ludl Electronic Products Ltd.) drives the plate in XY around the stationary optics and imaging subsystem, traversing an entire 96-well plate in seven steps (Figure 1(d)). Stepper motors provide z-translation of the multiwell plate, and also serve to neutralize plate tilt and mechanical bow inherent to commercial plates (Figure 1(a)). To enable precise control over hardware across the AHT system, a unique and custom-designed operating system manages a multifunctional synchronization framework that coordinates events across multiple hardware domains with ∼100 μs resolution. Packaged together, the AHT system employs a fully autonomous pipeline that acquires video for a full 96-well plate within 10 min and outputs mechanical information for each well within an hour.

FIG. 1.

The AHT microscope. (a) System: In the center of the photo are the 12-objective lenses that sit beneath a 96-well multiwell plate (not shown). The objectives are surrounded by the XY-positioning stage. Three individually controlled stepper motors (marked by asterisks) drive the XY stage and multiwell plate in Z and compensate for tilt. The entire system is about the size of a breadbox. (b) The AHT imaging block. Beneath the 12-objectives are 5 printed circuit boards that supply voltage to the liquid lenses and current to the amber and blue LEDs that provide epi-fluorescence illumination. At the bottom of the imaging block are the control boards for the 12 cameras. (c) The objective array. The objectives are anchored between a support plate and an objective clamping plate. Each objective has a pin that supplies voltage to its liquid lens. (d) This schematic of a multiwell plate shows the neighborhood of wells visited by each of the 12 imaging channels (example shadowed in blue for channel 11). In a typical experiment, each channel starts in the upper-left corner of its neighborhood and follows the sequence shown in the figure for imaging channel 8.

A. Optics and imaging block

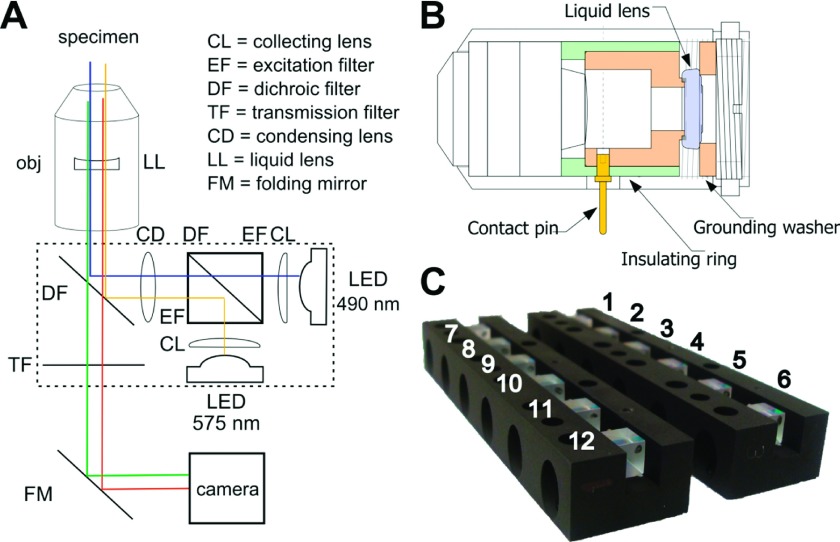

The AHT microscope contains twelve independent optical and imaging subsystems. In order to work within the physical footprint of SBS standard multiwell plates, we designed a compact optical hub for epi-fluorescent imaging (Figure 2). Each optical channel features two LED light sources, each centered at wavelengths that correspond to traditional choices in fluorescence microscopy: the “blue” channel, centered around 490 nm, allows for standard Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) illumination, while the “amber” channel, centered around 575 nm, provides rhodamine and Texas red illumination. Control of these LEDs is managed by LEWOS, our custom operating system detailed in Sec. II, and the LEDs are activated in sequence, not simultaneously.

FIG. 2.

(a) Schematic of the optical path through the epi-fluorescence optical hub. The “blue” channel emits LED light centered around 490 nm for standard FITC and EGFP illumination. The “amber” channel emits LED light centered around 575 nm and provides rhodamine and Texas red illumination. (b) Technical drawing showing the retrofitted objective (rotated 90°). The liquid lens, shaded in purple, sits between custom-built brass pieces (orange), one of which makes electrical contact with the contact pin (yellow) while the other serves as case ground. The insulating ring (green) isolates the applied voltage from ground. (c) Epi-fluorescence optical hubs that direct excitation light for both illumination modes in all 12-channels of the AHT.

The light emitted by both LEDs is gathered by its own collection lens (CL) (Edmund Scientific). To properly filter and transmit the excitation light from both fluorescent LEDs, appropriate excitation filters (EF) and a dichroic filter (DF) were contract manufactured as a custom-designed optical cube (Edmund Scientific) and installed in the optical hub (Figure 2). The surface along the diagonal of the optical cube serves as a dichroic, passing the shorter wavelength excitation light from the blue channel, and reflecting the longer wavelength excitation light from the amber channel. An anti-reflective (AR) coating applied to the last surface of the optical cube minimizes light scattering within the cube (Figure 2(a)). Outside the optical cube, a condensing lens concentrates light which is then sent through the objective to the specimen via reflection from a second dichroic filter (Figure 2(a)), designed to block the excitation light from both blue and amber LEDs.

The AHT microscope uses a 40 X objective to collect and focus emission light (Figure 2(a)). To allow each imaging channel to independently focus in z, we retrofitted the objective with an electrically controllable liquid lens (LL), where applying sufficient voltage to the contact pin changes its electrowetting properties and thus the objective’s plane of focus (Figure 2(b)). The DF and transmission filter (TF) at the end of the optical hub ensure that only emission light passes successfully to the camera (Figure 2(a)). Once emission light leaves the optical hub, a folding mirror relays the light to the camera. In order to meet the space constraints dictated by the footprint of standard multiwell plates, we chose the remote-head version of the Dragonfly camera which offers 50+ frames per second (fps) at video graphics array (VGA) resolution, satisfying the desire to collect short timescale mechanical measurements from thermal diffusion of particles. The AHT microscopy system generates sufficient signal to noise to enable successful tracking of 200 nm beads at 15 fps and 500 nm (and larger) beads at 50 fps.

At this time, the AHT system does not provide temperature control. In order to meet the spatial constraints of the SBS plate standard, a significant number of power-dissipating electronic circuits had to share space within the completed optics subsystem. Due to confined space, the heat generated from these electronics raised the operating temperature of the system from an ambient 23 °C to 29 °C. Future enhancements already planned for the system include a temperature control subsystem that will allow for measurements at room temperature as well as the more physiologically relevant 37 °C.

B. Z-tilt adjustment of XY translation stage

For the rheology experiments discussed here, the twelve objective lenses of the AHT microscope are kept at the same focus value for the duration of the experiment. Therefore, the height and orientation of the specimen plate must be calibrated to ensure clear images of the specimen in every channel. Most SBS standard multiwell plates we tested had an inherent bow of 250–300 μm (center lower than edges). To maximize the system’s ability to image and collect data across a standard multiwell plate, it became necessary to quantify the amount of bow in each plate as well as level it with respect to the objective array. To accomplish this, we added coarse z-translation with three custom-designed digitally controlled fine adjustment stepper-motors (Hayden-Kerk) on which the XY-translation stage rests (Figure 1(a)). Each motor provides 1.5 microns of z-translation per tick and accommodates a total translation range of 12.7 mm. Additionally, each stepper-motor has an accompanying “home” switch that identifies the origin of the z-coordinate system, defined as the highest point in the range. These measures allowed us to subtract the tilt from the system, but did nothing to address the inherent bow of 300 μm. Our inclusion of the liquid lens provides us the means to compensate for the bow by sweeping through the z-space of each channel individually and independently. Such compensation is necessary for work with cells near the substrate. However, for the purposes of the experiments addressed in this work, we did not use the liquid lenses to independently alter focus, opting instead to use the system at its maximum working distance (650 μm), and lowering the entire stage so that all channels measured a plane of focus within each well’s sample volume.

In order to satisfy both height and orientation constraints, we implemented a method that automatically uses the microscope stage to obtain three-dimensional data about a given plate’s shape and location in space. We labeled the bottom surface of the multiwell plate with 1 μm diameter fluorescent beads and loaded the plate onto the XY stage, which then translated the plate to place the imaging objectives at specific locations between wells. The AHT system acquired images at successive heights as the z-control motors lowered the stage from its initial maximum height. The algorithm analyzed the images to find the height at which the beads at the bottom of the plate were at best focus. To convert these values to relative heights, we subtracted each value from the lowest point on the plate. The relative heights, combined with the x and y coordinates of the plate locations relative to the stage, provided the 3-dimensional shape data.

Since specimen plates are non-planar in general, we employed a method based on principle component analysis (PCA) to find the plane that best represents the plate’s location and orientation. First, the mean of all the points in the plate shape data is calculated. If there are N data points and Xj is the vector position of the jth point, then

is the vector position of the mean for all points. Next, the covariance matrix M of the points is found by

The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of this matrix are then calculated using an implementation of the Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm. Since the data are 3-dimensional, we obtain three eigenvector and eigenvalue pairs. The eigenvectors corresponding to the two largest eigenvalues then lie in a plane that best represents the plate as they correspond to orthogonal directions of maximum variation in the data. The normal to the plane is calculated as a cross product of these eigenvectors. Once the plane representing the plate is calculated, the constraints mentioned previously are satisfied by calculating the angles required to orient the plane parallel to the focal plane of the objectives, which is assumed to be the horizontal plane. Once oriented this way, the plate’s height is adjusted to satisfy the other constraint.

C. Launching events with optimal synchronization (LEWOS) operating system enables parallelization of functionality

At system architecture design time, no commercial-off-the-shelf control hardware or software provided the level of timing synchronization that was necessary for coordinating the system’s 200+ real-time signals. The architectural signals, all of which were implemented but not all presently used, consist of 48 current-controlled LED drivers, 12 modulated high voltage sinusoids for liquid lens focus control with 12 digitized voltage feedback signals, 48 bits of digital camera control of which 12 provide frame triggers, 48 bits of uncommitted output control signals, and 24 bits of uncommitted input signals. Architecturally, and in hardware, these signals are all synchronizable to within a microsecond. The presently implemented LEWOS software provides synchronization to within one millisecond.

To successfully meet these synchronization requirements, the hardware of the AHT system is controlled by a custom designed operating system: LEWOS. This architecture provides a language to communicate time-dependent instructions to an array of microcontrollers that then control LED illumination (for three sets of LEDs), focal plane adjustment via the voltage tunable liquid lenses, and camera triggering for image acquisition through barrier synchronization. The system runs on a set of thirteen microcontrollers (Texas Instruments Piccolo TMS320F28035), one for each of the twelve imaging and input-output (I/O) channels called receivers, and a thirteenth (master) that is tasked with scheduling and issuing commands to the twelve I/O channels. The master channel communicates via USB to the master control computer, and receives commands via Ethernet for each of its channels from the 12 imaging computers.

LEWOS organizes the microcontroller receivers into a global domain and a number of local domains. The global domain has time bases and events that are accessible to all local domains, and every domain (including the global domain) also has its own set of time bases and events. Instructions are sent from an external computer into the LEWOS system and reports are sent back. This lets the relative timing of all events in the system be specified down to the microsecond level, enabling cooperative parallel (high throughput) experiments on all channels at once.

To provide flexibility and rapid response, LEWOS includes a macro capability that enables sequences of operations to be specified and allows these to be triggered based on system events or to be run at a specific time. This lets the control computers pre-load a specific sequence of commands that define a specific experiment modality (change focus, start camera exposure, turn on LED, turn off LED, send camera result) with explicit inter-event timing for each and then execute the set of commands multiple times with a single call. The flexibility of event sequences and synchronization across channels of the AHT system shows the capacity of LEWOS to enable automation and parallelization of many traditional microscopy experiments—where passive microbead rheology, discussed here, is just one “mode.”

D. Parallel data collection and analysis

Where the AHT microscope system uses the LEWOS platform for all hardware control, a computing cluster handles the actual data collection and subsequent analysis. The cluster contains a total of thirteen computers, one for each of the twelve channel/cameras (control computers), and a thirteenth that serves in a supervisory capacity. The Message-Passing Interface (MPI) protocol37 launches the parallel job (list of instructions for executing a particular experiment) and synchronizes operations among the thirteen computers by sending messages between them during parallel execution. A shared Network File System (NFS) drive contains the program code and shared configuration files. During each experiment, a local drive on each control computer collects and stores its own experiment-derived data.

Each control computer uses a Firewire connection to collect images from the cameras and then stores them to the local disk. A networked LEWOS link and the Virtual Reality Peripheral Network (VRPN) protocol38 provide system access for each control computer to its specific camera microcontroller. The VRPN connection sends—and LEWOS executes—precisely timed sets of microcontroller instructions to strobe the LEDs, adjust focus, and trigger its camera. Together, the LEWOS and Firewire connections enable barrier synchronized event control and data collection for each channel of the AHT system; channels operate independently to execute a series of instructions, and then, in synchrony, move together to execute the next set of instructions.

Once data collection is complete, each control computer uses Video Spot Tracker (VST) software (cismm.org) and an nVidia Quadro 5000 graphics processing unit (GPU) to track particle trajectories from the generated videos in parallel. We use a GPU-accelerated tracking algorithm that is capable of roughly estimating particle localization in real-time, but requires more computation time to achieve the level of accuracy needed to reach the mechanical noise floor. Because the total collected video for a single rheology experiment can occupy up to a terabyte of disk space, each control computer implements a custom designed, lossless compression algorithm that reduces required disc space by up to 99% (manuscript under review). As the technology matures, we expect that real-time tracking may become more realistic given the aforementioned constraints. Even so, the compression algorithm will be useful since storing the video allows for subsequent analysis of data. For example, the local context of the bead, as revealed by the image, may be useful for understanding specimen heterogeneity. Also, improvements in tracking algorithms may allow a re-tracking of the original data, and to check the original tracking against systematic errors.

After data collection and tracking, the metadata, tracking data, and compressed videos are moved from each control computer to the supervisory computer for analysis and reporting. A suite of custom MATLAB scripts completely automates the process of: 1. reading in VST-generated tracker position time-series data for each video (one video for each field of view (FOV) in every well and channel); 2. FOV-specific dead-zone filtering and center-of-mass drift removal; 3. computing the MSD for individual particles in a given video (appropriately scaled by the length scaling for given channel); 4. aggregating MSDs for replicate wells on the plate; 5. computing the en semble sample-weighted average MSD; 6. determining the material properties of the specimen by transforming the average MSD into complex moduli via Eq. (2); 7. plate-wide analyses via heatmaps of material properties, MSD data, bead counts, and accuracy relative to expected values; and 8. generation of an HTML page for data organization, visualization, and reporting.

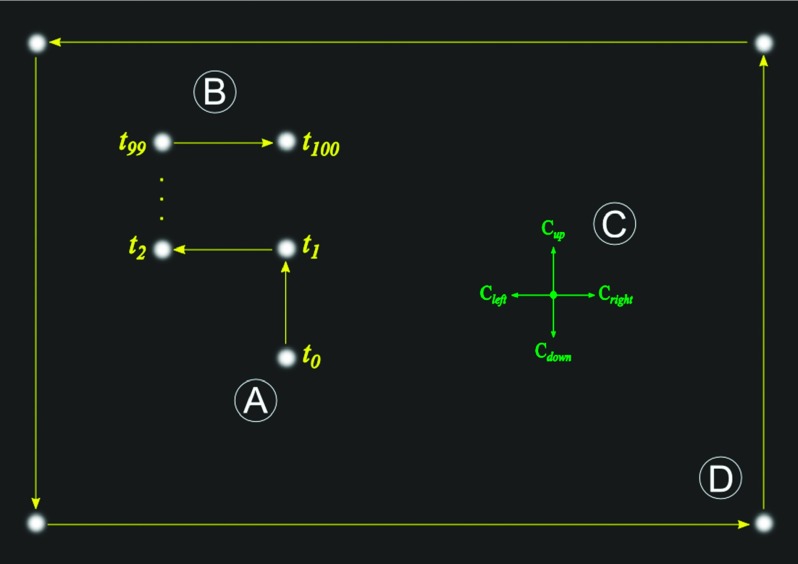

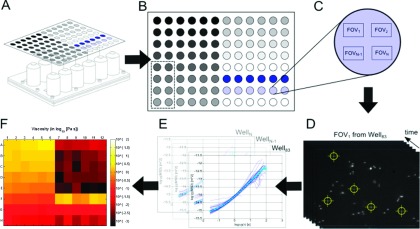

The workflow of an AHT experiment including data collection and analysis is shown in Figure 3.

FIG. 3.

Data collection and analysis workflow for AHT microscope experiment. (a) Schematic of a specimen-loaded multiwell plate above the 12-channel objective array. (b) Layout of a specimen plate for a “concentration sweep” type rheology experiment. The grey-scale gradient represents increasing concentration of a polymer solution (see Sec. IV and application to HA). The dashed rectangle partitions the wells accessed by the 7th objective in the array (see Figure 1(c)). (c) Blow-up of a well within the multiwell plate. After video is collected in each of the 8 wells accessed by the objective array, additional passes through the wells can be made. This schematic shows multiple locations, or FOV, for video collection within the given well. (d) Video data acquisition and single particle tracking. Once data are collected, the video for each FOV is tracked using particle tracking software (cismm.org) to generate time-series position measurements. (e) The MSD is computed for each particle (blue curves) using Eq. (1) and the ensemble sample-weighted average is computed (cyan curve). (f) The average MSD is transformed into the complex modulus using Eq. (2) and visualized in a heatmap at a particular timescale. Here, the experiment described in Sec. IV is shown in terms of the magnitude of the complex viscosity, at the 1 s timescale (see Figure 7(a)).

III. RESULTS

A. XY length-scale calibration

To measure the displacement of microbead trajectories in physical units, we calibrated the length-scale occupied by each pixel for each optical channel of the AHT system. To accomplish this, we suspended 1 μm fluorescent beads into polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and cured the polymer directly inside the wells of a multiwell plate, providing in-focus beads across a wide range of available focal planes. For the purposes of the experiments here, we applied no voltage to the liquid lenses.

For a given optical channel, the algorithm searches for a bead that is in focus. To avoid losing the tracking lock, the bead cannot be near image boundaries nor have any other beads nearby. Once the system finds a bead candidate, it instructs the XY stage to translate a locked distance of 3 μm (60 stage: “ticks”) in a random direction selected from +X, −X, +Y, and −Y (Figure 3(a)). The algorithm repeats the process for a total of 100 translations and tracks the target bead in image-space during the entire process (Figure 3(b)). Combining the reported translation of the stage with the tracked displacement generates four micron-to-pixels conversions, one for each axis direction (Figure 3(c)). With these conversions, the algorithm can move the bead to any desired position in the full field of view without losing the tracking lock. The algorithm then refines the conversions by displacing the target bead across the full field of view, visiting the bottom-right, top-right, top-left, and bottom-left corners in sequence (Figure 3(d)). The four conversion values are updated every time the bead gets back to its starting position and the measurement repeats until the algorithm cannot move the bead to a desired position more accurately. The length scale is determined by averaging the four direction conversions.

Executing this algorithm in each imaging channel in succession resulted in a total range of length scale calibrations from 145 to 151 nm/pixel. Using the mean, 149 nm/pixel, contributes up to 1.8% error in the determination of displacement and ultimately 3.7% error in the MSD and derived viscoelastic parameters. To remove this source of error, each channel carries its own calibration factor.

B. Static and dynamic localization error of the AHT microscope

The fidelity at which we can measure the diffusion profiles of any particle relies on the static and dynamic localizationerrors for the AHT system.39 The static localization error (SLE) measures the instrument noise floor and consists of intrinsic tracking error (particle tracking software) and system resolution limit due to noise sources. Our characterization includes estimations for both of these and provides some insight into the origin of the noise sources, namely, pixel-sampling and image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

To test the tracking software used in the AHT system, we used a method similar to that used in Ref. 39. Briefly, a set of images were constructed that contained simulated microspheres as Gaussian spots. Added to this image field was signal-independent Gaussian noise. Over the course of the simulated video, the simulated beads were translated across the field of view in sub-pixel displacements from an oversampled sub-image. The tracking software was made to track the simulated spots and the measured trajectories comparable to the known displacement function used to move the beads in the movie. For noise-levels compared to those found in the AHT, the software tracking routine predicts 0.03 pixel accuracy in position, or 4 nm, when scaled to the AHT optical system, demarcating our absolute best possible tracking resolution given conditions that provide the lowest camera noise.

To assess the noise floor of our AHT microscope, we dosed each well of a multiwell plate with 1 μl of 1 μm diameter beads in a 1:50 dilution with anhydrous ethanol and allowed the beads to evaporate onto the bottom of the specimen plate. The effective bead displacement of these fixed beads over one minute was measured using VST particle tracking software as described above (cismm.org). This procedure yields a minimum MSD value of 10−16.5 m2 at 50 fps, which corresponds to a particle tracking resolution of 5.7 nm for 1 μm diameter beads (Figure 4), a reasonable value relative to the tracking error described above. When we use a smaller, 500 nm bead diameter with a signal to noise ratio similar to the 1 μm beads, the SLE increases to 7.4 nm, an expected result due to a smaller number of camera pixels reducing the effectiveness of the tracking lock. For the even smaller 200 nm beads, the SLE increases further to 22 nm for a maximum effective 300 ms exposure time, this time because of the lower SNR.

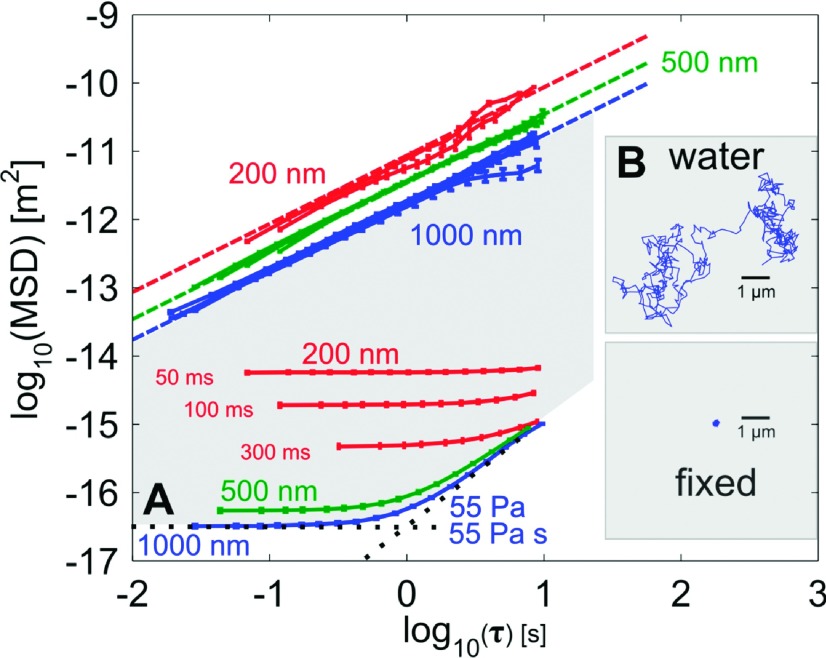

FIG. 4.

(a) The algorithm starts by locating a bead close to the center of the field of view. (b) Next, the XY stage translates the bead in a random direction (+X, −X, +Y, −Y) for a total of 100 steps at 60 stage ticks each. (c) These translations provide four separate calibration factors, one for each direction of motion. (d) The final calibration routine uses large translations across the entire field of view and is repeated until the accuracy limit is reached.

The previous noise values define the minimum SLE for each bead size, but at the expense of higher dynamic localization error (DLE), defined as an additional error in the assessment of particle position due to its motion while the camera’s shutter is open.39 Consequently, shortening the exposure time reduces the DLE by reducing the amount the particle travels in a single video frame. To establish whether such sources of error would confound our measurements, we tracked each bead size (1 μm, 500 nm, and 200 nm diameters) in water and calculated the resulting viscosity using Eq. (2), comparing the returned value with the expected value for water at the appropriate temperature. The two larger bead sizes, 500 nm and 1 μm, returned errors less than 10%, within the acceptable value for microrheology measurements. To get the lowest DLE for the smallest 200 nm beads, the exposure time had to be reduced from the 300 ms that minimized SLE. When the exposure time was reduced to 50 ms, the DLE decreased to less than 20%, but not without increasing the SLE from 22 nm to 76 nm. This challenge of maintaining the integrity of the data collected by the AHT microscope is why we include fluids of standard viscosity on each experimental plate.

C. Limits of microrheology measurements using the AHT microscope

With the system mechanical noise floor characterized, we can define the upper and lower limits of passive microrheology measurements in the AHT microscope. To define these instrumentation limits, we assume that linear viscoelastic materials follow the Maxwell model, such that a constant shear modulus, G, dominates at short timescales, and that a constant viscosity, η, dominates at long timescales. Measuring the microrheology properties of any material using video microscopy involves recording images with a video subsystem and tracking the diffusion of embedded particles.

Thus, three instrumental quantities constrain our passive microrheological measurements of G and η: maximum video frame rate, maximum video duration, and particle tracking resolution. The maximum video frame rate defines the smallest timescale for MSD measurements. In our system, the maximum frame rate for each channel’s camera, when capturing full frames (648 × 488 pixels), is 50 fps, which constrains the smallest timescale for mechanical measurement to be τmin = 20 ms. The largest timescale, for most measurable materials, is limited by the storage space needed for the acquired video data. For the AHT system, this is on the order of an hour, setting the long timescale to τmax = 3600 s. It should be noted that the largest accessible timescale for mechanical measurements of materials close to the mechanical noise floor will be constrained more than this limit. The particle tracking resolution is determined empirically by measuring the motion of fixed particles at full frame rate and estimating the resolution from the calculated MSD. Using the procedure discussed in Sec. III B, the tracking resolution of the AHT system is 5.7 nm.

To predict the maximum G we can measure in our AHT microscope, we use Eq. (2) and assume the slope of the MSD is approximately zero for a particle embedded in a purely elastic material. For a 1 μm beads translating on the order of our tracking resolution, we determine the maximum limit of G to be 55 Pa. This range provides us the ability to probe the moduli of various soft biopolymer systems.

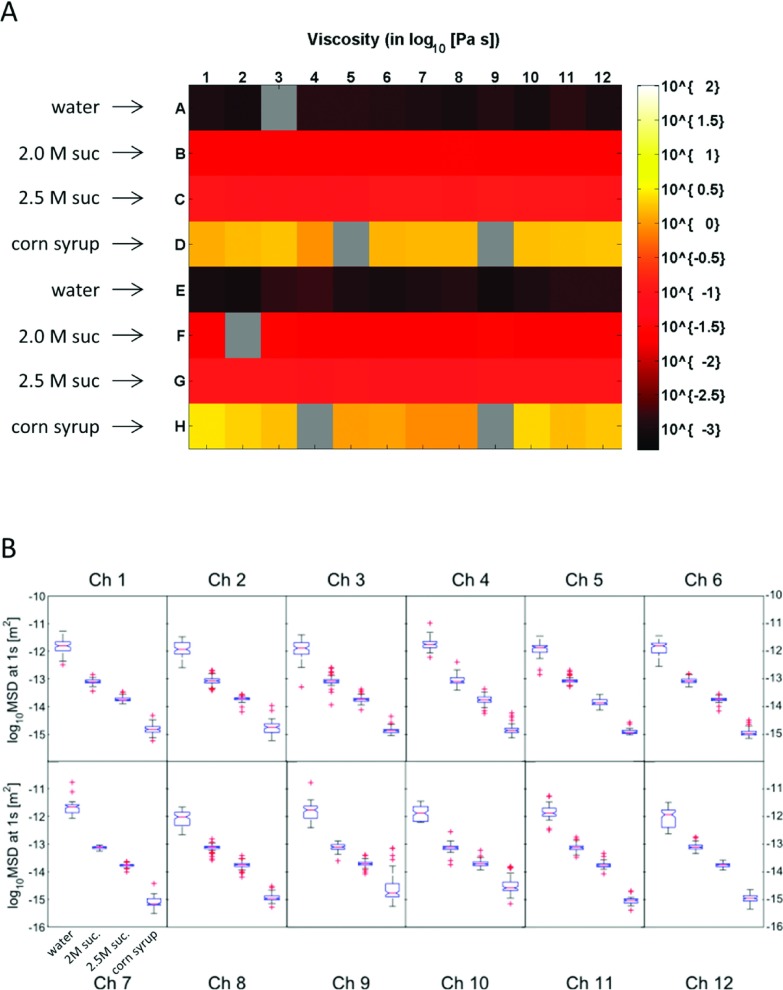

D. AHT system validation and viscosity accuracy characterization

To test AHT system function and accuracy, we evaluated a multiwell plate that contained four Newtonian fluids: water, 2.04 M sucrose, 2.5 M sucrose, and corn syrup. The materials were dosed with 1 μm fluorescent beads at a concentration of 0.004% (1:500) and characterized on a CAP rheometer at T = 29 °C, the working temperature of the AHT system; The CAP-determined viscosities were 2.04 M sucrose (η = 20.0 mPa s), 2.5 M sucrose (η = 83.1 mPa s), and corn syrup (η = 2840 mPa s). The viscosity of water at T = 29 °C was determined as η = 0.84 mPa s from Ref. 40. The materials were then loaded in alternating rows of the multiwell plate (50 μl/well) such that each imaging channel of the AHT system (Figure 1(d)) received two replicates of each fluid. The AHT system assayed the test plate, according to the workflow shown in Figure 3, yielding viscosity measurements in 90 of 96 wells for timescales τ from 0.03 s to as long as 120 s, depending on the material viscosity. These data are shown in Figure 6. A plate-wide heatmap of the measured viscosity at the τ = 1 s timescale is shown in Figure 6(a).

FIG. 6.

Characterization of standard Newtonian fluids using the AHT microscope. (a) Viscosity heatmap for alternating rows of water, 2.04 M sucrose, 2.5 M sucrose, and corn syrup. The materials were dosed with 1 μm fluorescent beads and a 50 μl volume was loaded into each well of a 96-well plate. Five 2 min videos at 34 fps were taken at different FOVs in each well. The viscosity at the 1 s timescale is plotted, obtained using the workflow shown in Figure 4. Gray wells indicate positions where the AHT system collected no data, which happens randomly and with low probability. (b) Boxplots of the fluid-aggregated MSD distributions at the 1 s timescale by channel (each channel was loaded with two wells of each fluid). For each distribution, the boxes denote the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles, whiskers extend to non-outlier data defined by Q3 + 1.5∗(Q3 − Q1) and Q1 − 1.5∗(Q3 − Q1) and symbolized with (+). An ANOVA test was performed on the MSD distributions of each fluid. Results indicated that each channel could statistically distinguish each fluid (p ≪ 0.0001).

Distinguishability of the four materials by the AHT system was tested at the channel level by aggregating replicate wells of each fluid within a channel and performing an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test against the 4 specimens on the value of the MSD at the 1 s timescale. Results of this analysis showed that each channel measured statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001) between the 4 fluids (Figure 6(b)).

Accuracy of the AHT system relative to the material characterization by CAP or Ref. 40 was then evaluated for each well. To minimize the effect of low sampling at long time scales, the ensemble sample-averaged MSD for each well was contracted by 1 decade at long τ. Since short timescale estimations of corn syrup routinely challenged the system noise floor (indicated by slopes that approached zero in log MSD vs log τ space), timescales before 1 s were contracted for the aggregated MSD in these wells. The viscosity measurement η for a given fluid in a particular well was then obtained by performing a sampling-weighted fit of the average MSD data to the Stokes-Einstein relation (Eq. (2) applied to Newtonian fluids)

Finally, the plate-level viscosity accuracy of a given fluid was determined by taking a bead-weighted average across wells (and hence across channels or imaging systems) of the given fluid. We find that the AHT system measures water with 4.3% error, 2.04 M sucrose with 5.2% error, 2.5 M sucrose with 3.6% error, and corn syrup with 35.6% error.

IV. APPLICATION: PASSIVE MICROBEAD RHEOLOGY OF HYALURONIC ACID

The motivation for our development of the AHT system was to enable the parallel, high throughput characterization of biomaterials in parameter spaces—spanning small molecule, siRNA, and loss and gain of function libraries—previously inaccessible to investigation. In order to first compare the biophysical output of the AHT system to that of other characterizations in the community, we examine a suite of concentrations of hyaluronan.

HA is a linear, high molecular weight biopolymer found in the extracellular matrix of vertebrate tissue and is composed of two repeating saccharide derivatives, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucuronic acid, linked by glycosidic bonds. Recent studies with the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) suggest that ultra-high molecular weight HA may be responsible for the low cancer incidence reported in the species.34

The rheological properties of HA have been studied using different techniques, including CAP41 and laser interferometry (laser trap).42 Here, we used the AHT microscopy system to make similar measurements of HA by preparing a series of 12 solutions that ranged in concentration from 0.5 mg/ml to 15 mg/ml. Because HA is a charged polyelectrolyte, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as the solution buffer, placing all solutions in the high-salt limit. Each solution was dosed with 1 μm beads to a final 0.004% w/v concentration. Each solution concentration occupied 6 replicate wells occupying one half of one row in the plate (see Figure 7(b)). The last three half-rows served as viscosity controls and as such contained the same standard viscosity solutions used earlier to qualify the AHT system.

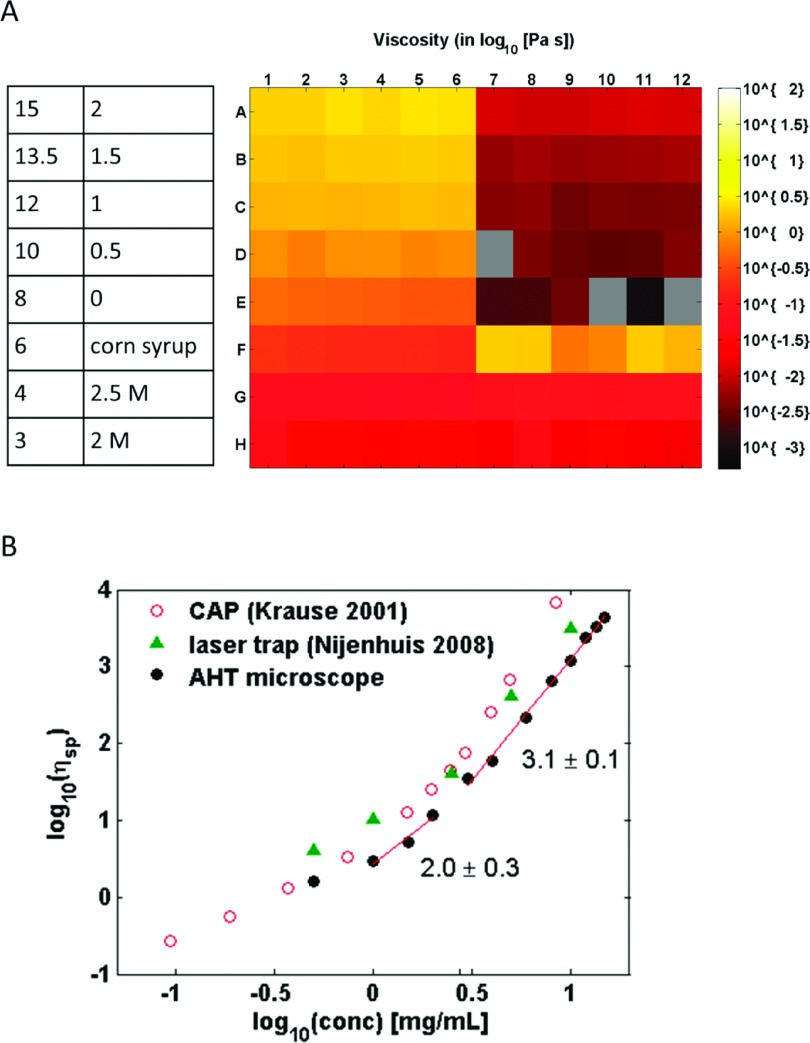

FIG. 7.

High-throughput passive microbead rheology of HA: (a) Viscosity heatmap for a multiwell plate that contained a HA concentration sweep with 6 replicate wells (concentrations shown in table on left). Well locations that are gray contain no data. Viscosity standards are shown in the bottom-right of the heatmap. The reported viscosity for the HA solutions decreases with a corresponding decrease in concentration. (b) Plotting the specific viscosity of HA as a function of its concentration reveals power-law relationships similar to those found in previous literature using different rheological methods.

The workflow used to run this experiment is shown in detail in Figure 5. The system collected videos at 35 frames per second for a duration of 120 s. A total of 10 FOV were selected by the AHT system, where each FOV had an average of 4 trajectories. Aggregating data across all fields of view and replicates resulted in an average of 200 trajectories for each condition. The analysis subsystem computed the MSDs for each trajectory and the ensemble average MSD was transformed to G′ and G″ using the generalized Stokes-Einstein equation (Eq. (1)).35

FIG. 5.

Limits of measure for the AHT microscope shown as MSDs for different bead sizes in water or attached to the substrate of the multiwell plate. Bead sizes are labeled according to color: blue (1 μm), green (500 nm), and red (200 nm). (a) The lowest noise floor corresponds to 55 Pa maximum G′ and a 55 Pa s maximum η′ for a 1 μm bead diameter due to high signal and larger pixel sampling. The shaded region corresponds to the measurement space available to the AHT with a 1 μm bead. The 500 nm bead shows a slightly higher noise floor for a similar SNR because of the lower pixel sampling. Three different exposure times are shown for the 200 nm bead diameter, showing how the lower SNR degrades the noise floor and raises the SLE. (b) Shown are data from all bead sizes diffusing through water. The dashed lines indicate the expected MSD for water at the appropriate temperature. All bead sizes sampled for the exposure times shown in the figure exhibit low dynamic localization error (<10%) except for the 200 nm beads at 50 ms exposure time which was <20%. To increase the exposure time for the 200 nm bead would further reduce the SLE and result in a correspondingly higher DLE. Inset: Example trajectories for a 1 μm bead diffusing through water, or fixed to the plate substrate.

Figure 7(a) shows a heat map representation of the resulting 96-well plate, where the color corresponds to apparent viscosity measured at one second timescales, i.e., ηapparent = |η∗(f = 1 Hz)|. We identify wells that collected no data as slate gray in color. Except for the corn syrup, which challenged our noise floor, the standard sucrose solutions returned values with <10% error from the expected value, consistent with the qualifying standards plate shown in Figure 6. The apparent viscosity for the HA solutions decreases as the concentration decreases.

In Figure 7(b), we plot the specific viscosity returned by the AHT system as a function of HA concentration. The data collected from the 96-well plate span almost 2 decades in concentration. To compare our results with literature values, we calculated the specific viscosity as ηsp = (η − ηs)/(ηs), where ηs is the viscosity of the solvent, in this case, PBS (identified on the plate as 0 mg/ml HA). Previous studies of HA rheology at this molecular weight (1.5 MD) have shown power law behaviors that correspond to the semidilute-unentangled and semidilute-entangled regimes. We find a breakpoint in the power-law slope at 2.8 mg/ml HA concentration, similar to observations seen by Krause et al. (2.4 mg/ml) using a macroscale cone-and-plate rheometer, and by Nijenhuis et al. (2.9 mg/ml) using laser interferometry.41,42

Our data from the semidilute, entangled regime had a power law slope of 3.1 ± 0.1, a value that agrees well with the empirical data collected by Nijenhuis et al., but is lower than expected by theory (3.75), and lower still than data collected by Krause (4.1 ± 0.2). The lower slope in our data could be caused by the slightly higher operating temperature (29 °C) than that used in other studies, but is most likely caused by the higher concentrations challenging the noise floor of the AHT system.

V. CONCLUSIONS

We have presented the novel technology of a parallel, high throughput microscopy system, and have validated its use by determining the mechanical properties of Newtonian fluids and a soft biomaterial (HA). Our system generates parallel and high throughput assay capacity by integrating twelve independent but barrier synchronized optical and imaging systems, automating video data acquisition, utilizing rapid and accurate particle tracking software, implementing a novel lossless compression algorithm, and automating rheological analysis. The end result is high fidelity biophysical measurements generated almost two orders of magnitude faster than convention techniques once an assay plate is loaded. We find that the system at present can measure elastic moduli (G′) and viscosities up to 55 Pa and 55 Pa s, respectively. These biophysical limits encompass a useful range of biomaterials such as soft tissues, cervical and lung mucus, and the cytoplasm of cells.

Future work to characterize and calibrate the liquid lens in the AHT will provide the means to scan through sample volumes and select a focal plane of interest. This new functionality will allow us to use locating algorithms to automatically focus on beads attached to or engulfed by cells or, in the case of microrheology experiments, the focal plane that has the highest number of beads in coincident focus. Collecting data over a range of heights for complex biomaterials like mucus will empower us to better study its spatial heterogeneity, a property studied for its influence on mucociliary clearance.20

Future investigations include using the AHT system to examine the biophysical properties of cells, HA, and other soft biomaterials that are treated by small molecule or genetic knockdown libraries. Large scale studies enabled by the AHT system hold promise of elucidating the connection between biomechanics and disease progression, and could identify candidate biomarkers to be targeted therapeutically.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering through Grant Nos. 5-P41-EB002025 and NCI R33-CA155618. JC, ETO, RT, and RS hold equity stake in, and RS serves as consultant on the board of directors of Rheomics, Inc., that has a license to the array microscope technology that is evaluated in the study of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macarron R., Banks M. N., Bojanic D., Burns D. J., Cirovic D. A., Garyantes T., Green D. V. S., Hertzberg R. P., Janzen W. P., Paslay J. W., Schopfer U., and Sittampalam G. S., “Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 10(3), 188–195 (2011). 10.1038/nrd3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffy K. J., Darcy M. G., Delorme E., Dillon S. B., Eppley D. F., Erickson-Miller C., Giampa L., Hopson C. B., Huang Y., Keenan R. M., Lamb P., Leong L., Liu N., Miller S. G., Price A. T., Rosen J., Shah R., Shaw T. N., Smith H., Stark K. C., Tian S. S., Tyree C., Wiggall K. J., Zhang L., and Luengo J. I., “Hydrazinonaphthalene and azonaphthalene thrombopoietin mimics are nonpeptidyl promoters of megakaryocytopoiesis,” J. Med. Chem. 44(22), 3730–3745 (2001). 10.1021/jm010283l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorr P., Westby M., Dobbs S., Griffin P., Irvine B., Macartney M., Mori J., Rickett G., Smith-burchnell C., Napier C., Webster R., Armour D., Price D., Stammen B., Wood A., and Perros M., “Maraviroc (UK-427, 857 ), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49(11), 4721–4732 (2005). 10.1128/aac.49.11.4721-4732.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao M., Nettles R. E., Belema M., Snyder L. B., Nguyen V. N., Fridell R. A., Serrano-Wu M. H., Langley D. R., Sun J.-H., O’Boyle D. R., Lemm J. A., Wang C., Knipe J. O., Chien C., Colonno R. J., Grasela D. M., Meanwell N. A., and Hamann L. G., “Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect,” Nature 465(7294), 96–100 (2010). 10.1038/nature08960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desbordes S. C., Placantonakis D. G., Ciro A., Socci N. D., Lee G., Djaballah H., and Studer L., “High-throughput screening assay for the identification of compounds regulating self-renewal and differentiation in human embryonic stem cells,” Cell Stem Cell 2(6), 602–612 (2008). 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke C., Liu M., Britton W., Triccas J. A., Thomas T., Smith A. L., Allen S., Salomon R., and Harry E., “Harnessing single cell sorting to identify cell division genes and regulators in bacteria,” PLoS One 8(4), e60964 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0060964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson K. J., Selfors L. M., Bui J., Reynolds A., Leake D., Khvorova A., and Brugge J. S., “Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach,” Nat. Cell Biol. 10(9), 1027–1038 (2008). 10.1038/ncb1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Conor C. J., Leddy H. A., Benefield H. C., Liedtke W. B., and Guilak F., “TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction regulates the metabolic response of chondrocytes to dynamic loading,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111(4), 1316–1321 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1319569111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Adams J., Leddy H. A., McNulty A. L., O’Conor C. J., and Guilak F., “The mechanobiology of articular cartilage: Bearing the burden of osteoarthritis,” Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 16(10), 451 (2014). 10.1007/s11926-014-0451-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins C., Osborne L. D., Guilluy C., Chen Z., O’Brien E. T., Reader J. S., Burridge K., Superfine R., and Tzima E., “Haemodynamic and extracellular matrix cues regulate the mechanical phenotype and stiffness of aortic endothelial cells,” Nat. Commun. 5, 3984 (2014). 10.1038/ncomms4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kater A., Henke M. O., and Rubin B. K., “The role of DNA and actin polymers on the polymer structure and rheology of cystic fibrosis sputum and depolymerization by gelsolin or thymosin beta 4,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1112, 140–153 (2007). 10.1196/annals.1415.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin B. K., “Mucus structure and properties in cystic fibrosis,” Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 8(1), 4–7 (2007). 10.1016/j.prrv.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pezold M., Moore E. E., Wohlauer M., Sauaia A., Gonzalez E., Banerjee A., and Silliman C. C., “Viscoelastic clot strength predicts coagulation-related mortality within 15 minutes,” Surgery 151(1), 48–54 (2012). 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nystrup K. B., Windeløv N. A., Thomsen A. B., and Johansson P. I., “Reduced clot strength upon admission, evaluated by thrombelastography (TEG), in trauma patients is independently associated with increased 30-day mortality,” Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 19(1), 52 (2011). 10.1186/1757-7241-19-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swaminathan V., Mythreye K., O’Brien E. T., Berchuck A., Blobe G. C., and Superfine R., “Mechanical stiffness grades metastatic potential in patient tumor cells and in cancer cell lines,” Cancer Res. 71(15), 5075–5080 (2011). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plodinec M., Loparic M., Monnier C. A., Obermann E. C., Zanetti-Dallenbach R., Oertle P., Hyotyla J. T., Aebi U., Bentires-Alj M., Lim R. Y. H., and Schoenenberger C.-A., “The nanomechanical signature of breast cancer,” Nat. Nanotechnol. 7(11), 757–765 (2012). 10.1038/nnano.2012.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osborne L. D., Li G. Z., How T., O’Brien E. T., Blobe G. C., Superfine R., and Mythreye K., “TGF-β regulates LARG and GEF-H1 during EMT to impact stiffening response to force and cell invasion,” Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3528 (2014). 10.1091/mbc.e14-05-1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkham S., Sheehan J. K., Knight D., Richardson P. S., and Thornton D. J., “Heterogeneity of airways mucus: Variations in the amounts and glycoforms of the major oligomeric mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B,” Biochem. J. 361, 537–546 (2002). 10.1042/0264-6021:3610537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Callaghan R., Job K. M., Dull R. O., and Hlady V., “Stiffness and heterogeneity of the pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx measured by atomic force microscopy,” Am. J. Physiol.: Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 301(3), L353–L360 (2011). 10.1152/ajplung.00342.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellnik J., Vasquez P. A., McKinley S. A., Witten J., Hill D. B., and Forest M. G., “Micro-heterogeneity metrics for diffusion in soft matter,” Soft Matter 10(39), 7781–7796 (2014). 10.1039/C4SM00676C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed J., Frank M., Troke J. J., Schmit J., Han S., Teitell M. A., and Gimzewski J. K., “High throughput cell nanomechanics with mechanical imaging interferometry,” Nanotechnology 19(23), 235101 (2008). 10.1088/0957-4484/19/23/235101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu P.-H., Hale C. M., Chen W.-C., Lee J. S. H., Tseng Y., and Wirtz D., “High-throughput ballistic injection nanorheology to measure cell mechanics,” Nat. Protoc. 7(1), 155–170 (2012). 10.1038/nprot.2011.436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gossett D. R., Tse H. T. K., Lee S. A., Ying Y., Lindgren A. G., Yang O. O., Rao J., Clark A. T., and Di Carlo D., “Hydrodynamic stretching of single cells for large population mechanical phenotyping,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109(20), 7630–7635 (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1200107109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spero R. C., Vicci L., Cribb J., Bober D., Swaminathan V., O’Brien E. T., Rogers S. L., and Superfine R., “High throughput system for magnetic manipulation of cells, polymers, and biomaterials,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79(8), 083707 (2008). 10.1063/1.2976156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill D. B., Vasquez P. A., Mellnik J., McKinley S. A., Vose A., Mu F., Henderson A. G., Donaldson S. H., Alexis N. E., Boucher R. C., and Forest M. G., “A biophysical basis for mucus solids concentration as a candidate biomarker for airways disease,” PLoS One 9(2), e87681 (2014). 10.1371/journal.pone.0087681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spero R. C., Sircar R. K., Schubert R., Taylor R. M., Wolberg A. S., and Superfine R., “Nanoparticle diffusion measures bulk clot permeability,” Biophys. J. 101(4), 943–950 (2011). 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman B. D., Massiera G., Van Citters K. M., and Crocker J. C., “The consensus mechanics of cultured mammalian cells,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103(27), 10259–10264 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0510348103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massiera G., Van Citters K. M., Biancaniello P. L., and Crocker J. C., “Mechanics of single cells: Rheology, time dependence, and fluctuations,” Biophys. J. 93(10), 3703–3713 (2007). 10.1529/biophysj.107.111641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wirtz D., “Particle-tracking microrheology of living cells: Principles and applications,” Annu. Rev. Biophys. 38, 301–26 (2009). 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hale C. M., Sun S. X., and Wirtz D., “Resolving the role of actoymyosin contractility in cell microrheology,” PLoS One 4(9), e7054 (2009). 10.1371/journal.pone.0007054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breedveld V. and Pine D. J., “Microrheology as a tool for high-throughput,” J. Mater. Sci. 8, 4461–4470 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seluanov A., Hine C., Azpurua J., Feigenson M., Bozzella M., Mao Z., Catania K. C., and Gorbunova V., “Hypersensitivity to contact inhibition provides a clue to cancer resistance of naked mole-rat,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106(46), 19352–19357 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0905252106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim E. B., Fang X., Fushan A. A., Huang Z., Lobanov A. V., Han L., Marino S. M., Sun X., Turanov A. A., Yang P., Yim S. H., Zhao X., Kasaikina M. V., Stoletzki N., Peng C., Polak P., Xiong Z., Kiezun A., Zhu Y., Chen Y., Kryukov G. V., Zhang Q., Peshkin L., Yang L., Bronson R. T., Buffenstein R., Wang B., Han C., Li Q., Chen L., Zhao W., Sunyaev S. R., Park T. J., Zhang G., Wang J., and Gladyshev V. N., “Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat,” Nature 479(7372), 223–227 (2011). 10.1038/nature10533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian X., Azpurua J., Hine C., Vaidya A., Myakishev-Rempel M., Ablaeva J., Mao Z., Nevo E., Gorbunova V., and Seluanov A., “High-molecular-mass hyaluronan mediates the cancer resistance of the naked mole rat,” Nature 499, 1–6 (2013). 10.1038/nature12234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason T. G., “Estimating the viscoelastic moduli of complex fluids using the generalized Stokes-Einstein equation,” Rheol. Acta 39(4), 371–378 (2000). 10.1007/s003970000094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.S. for B. screening footprint dimensions for microplates. society for biomolecular screening, 2006.

- 37.Pacheco P. S., Parallel Programming with MPI (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, San Francisco, California, 1997), p. 418. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor II R. M., Hudson T. C., Seeger A., Weber H., Juliano J., and Helser A. T., “VRPN : A device-independent, network-transparent VR peripheral system,” in Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology (2001), pp. 55–61 10.1145/505008.505019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savin T. and Doyle P. S., “Static and dynamic errors in particle tracking microrheology,” Biophys. J. 88(1), 623–638 (2005). 10.1529/biophysj.104.042457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin C., Greenwald D., and Banin A., “Temperature dependence of infiltration rate during large scale water recharge into soils,” Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67, 487–493 (2003). 10.2136/sssaj2003.4870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krause W. E., Bellomo E. G., and Colby R. H., “Rheology of sodium hyaluronate under physiological conditions,” Biomacromolecules 40, 65–69 (2001). 10.1021/bm0055798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nijenhuis N., Mizuno D., Schmidt C. F., Vink H., and Spaan J. A. E., “Microrheology of hyaluronan solutions: Implications for the endothelial glycocalyx,” Biomacromolecules 9(9), 2390–2398 (2008). 10.1021/bm800381z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]