Abstract

The continued threat of worldwide influenza pandemics, together with the yearly emergence of antigenically drifted influenza A virus (IAV) strains, underscore the urgent need to elucidate not only the mechanisms of influenza virulence, but also those mechanisms that predispose influenza patients to increased susceptibility to subsequent infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Glycans displayed on the surface of epithelia that are exposed to the external environment play important roles in microbial recognition, adhesion, and invasion. It is well established that the IAV hemagglutinin and pneumococcal adhesins enable their attachment to the host epithelia. Reciprocally, the recognition of microbial glycans by host carbohydrate-binding proteins (lectins) can initiate innate immune responses, but their relevance in influenza or pneumococcal infections is poorly understood. Galectins are evolutionarily conserved lectins characterized by affinity for β-galactosides and a unique sequence motif, with critical regulatory roles in development and immune homeostasis. In this study, we examined the possibility that galectins expressed in the airway epithelial cells might play a significant role in viral or pneumococcal adhesion to airway epithelial cells. Our results in a mouse model for influenza and pneumococcal infection revealed that the murine lung expresses a diverse galectin repertoire, from which selected galectins, including galectin 1 (Gal1) and galectin 3 (Gal3), are released to the bronchoalveolar space. Further, the results showed that influenza and subsequent S. pneumoniae infections significantly alter the glycosylation patterns of the airway epithelial surface and modulate galectin expression. In vitro studies on the human airway epithelial cell line A549 were consistent with the observations made in the mouse model, and further revealed that both Gal1 and Gal3 bind strongly to IAV and S. pneumoniae, and that exposure of the cells to viral neuraminidase or influenza infection increased galectin-mediated S. pneumoniae adhesion to the cell surface. Our results suggest that upon influenza infection, pneumococcal adhesion to the airway epithelial surface is enhanced by an interplay among the host galectins and viral and pneumococcal neuraminidases. The observed enhancement of pneumococcal adhesion may be a contributing factor to the observed hypersusceptibility to pneumonia of influenza patients.

Keywords: Influenza, Pneumococcus pneumoniae, galectin, neuraminidase, airway A549 cells

1. Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) can cause highly pathogenic infections that significantly contribute to morbidity and mortality in humans as well as animal species worldwide. Despite continuously improved vaccination efforts, half a million people die yearly worldwide from seasonal influenza and associated complications. In United States, seasonal influenza outbreaks alone cause an annual average of 200,000 hospitalizations and from 5,000 to 49,000 deaths (Thompson et al. 2009). Influenza is commonly associated with a high risk of complications in children, the elderly, and adults with certain conditions such as asthma, diabetes, morbid obesity, and pregnancy (Barker and Mullooly 1980; Barker and Mullooly 1982; Singleton et al. 2004; Jain et al. 2009). Only recently has it been recognized that the majority of deaths following influenza infection result from ensuing bacterial superinfection, most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (Kash et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012; Weeks-Gorospe et al. 2012; Marzano et al. 2013; Stegemann-Koniszewski et al. 2013). In addition to pneumonia, this secondary bacterial infection can lead to disseminated infections, such as meningitis and septicemia (Cartwright 2002). The yearly occurrence of variant influenza strains due to antigenic drift, the sporadic emergence of influenza strains due to antigenic shift [such as A(H1N1)pdm09], and the continued threat of the pandemic potential of avian influenza viruses underscore the urgent need to elucidate not only the mechanisms of IAV virulence and transmission, but equally importantly those mechanisms that predispose IAV patients to increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial infection.

IAV has a negative stranded RNA genome, consisting of 8 segments that encode up to 12 proteins. Among these, the glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) play important roles in mediating interactions between the virion and the host cell surface glycans (von Itzstein 2008). Sialylated N-glycans on the epithelial cells lining the airways are targets for HA-mediated viral adhesion, and promote the subsequent clathrin-dependent or independent internalization of the virus (Lakadamyali et al. 2004; de Vries et al. 2011). The abundant sialylation of these glycans is dynamically regulated through the complementing activities of endogenous sialyltransferases (Harduin-Lepers et al. 2001) and sialidases (Monti et al. 2002; Schwerdtfeger and Melzig 2010). The viral NA cleaves the terminal sialic acid residues from both the newly synthesized virion glycoproteins as well as those from the host cell surface, enabling the cell-surface aggregated virion progeny to elute away from the host cell and spread the infection (von Itzstein 2007). Further, the NA activity on the airway epithelia dramatically alters the host cell surface glycosylation, modulating the local and systemic immune responses and potentially facilitating bacterial infections (Feng et al. 2013b). Among these, a severe pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae, a gram-positive bacterium, is the most frequently observed influenza-associated bacterial infection, which is particularly life threatening in children and the elderly (Cartwright 2002). Like in IAV, the surface glycans and carbohydrate-binding proteins of S. pneumoniae play key role(s) in infection and pathogenesis (Lu and Nuorti 2010; Nuorti and Whitney 2010; Sanchez et al. 2011). Once disseminated, S. pneumoniae induces multiple inflammatory responses, including uncontrolled cytokine synthesis and secretion that may lead to septic shock (Hogg and Walker 1995; Tuomanen et al. 1995; Bergeron et al. 1998; Manco et al. 2006; Brosnahan and Schlievert 2011). However, the detailed mechanisms responsible for the increased susceptibility of influenza patients to subsequent pneumococcal pneumonia are not well understood.

Glycans displayed on the host cell and microbial pathogen surfaces encode key information that can be modified by endogenous and exogenous glycosidases and glycosyltransferases, thereby modulating host-pathogen interactions and their downstream effects, including the host innate and adaptive immune responses (Hsu et al. 2000; Gauthier, L. et al. 2002; Fernandez et al. 2005; Perone et al. 2006; Rabinovich and Ilarregui 2009). For example, an array of glycans (polysaccharides, glycoproteins, or glycolipids) on the microbial surface can be recognized by the host through carbohydrate-binding proteins (or lectins) that function as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and convey information about the potential infectious challenge to the host cell, triggering signaling pathways that lead to immune activation (Barrionuevo et al. 2007; Jeon et al. 2010). Further, the host lectins are important not only in pathogen recognition and regulation of immune responses, but their functions can be subverted by microbial pathogens for adhesion and entry into the host cells (Kamhawi et al. 2004; Ouellet et al. 2005; Okumura et al. 2008; Vasta 2009; Yang et al. 2011). Among the various lectin families, galectins have recently been shown to function not only as immune recognition receptors and effector factors, but also as portals for viral, bacterial, and parasitic infection (Tasumi and Vasta 2007; Nieminen et al. 2008; Stowell et al. 2008; Vasta 2009; St-Pierre et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2011). Galectins are a family of soluble β-galactoside-binding proteins that are synthesized in the cytosol and may carry out their biological roles in the nuclear compartment, at the cell surface, or in the extracellular space. They are classified into three major structural types: (i) proto-type; (ii) chimera-type; and (iii) tandem-repeat-type galectins. Most galectins form oligomers that are either bivalent or multivalent and enable the recognition of multiple binding partners. Although initially described as involved in early development and embryogenesis, evidence has accumulated in recent years in support of key roles in immune homeostasis and microbial recognition (Rabinovich and Toscano 2009; Vasta 2009; Davicino et al. 2011). Desialylation of surface glycans on epithelial cells by both host endogenous neuraminidases (Neu1–4) and neuraminidases from both IAV and S. pneumoniae can unmask subterminal galactosyl moieties and expose them as potential ligands for secreted galectins. Thus, we hypothesized that upon influenza primary infection, the exposure of galactosyl moieties on the airway epithelia by the interplay of neuraminidases from IAV, S. pneumoniae, and the host, modulates the roles of galectins in innate/adaptive immune recognition, and contributing to the hypersusceptibility to pneumococcal infection observed.

In this study, we examined both in vitro and in vivo the possibility that upon IAV infection, galectins from the airway epithelial cells together with the activity of IAV and S. pneumoniae neuraminidases, might have a significant role in enhancing S. pneumoniae adhesion to the airway epithelium. Our results in a mouse model revealed that the murine lung expresses a diverse galectin repertoire, that selected galectins are released to the bronchoalveolar space, and that influenza and subsequent exposure to S. pneumoniae infections modulate galectin expression and release, as well as the glycosylation of the epithelial surface. In vitro studies on the airway cell line A549 were consistent with the observations made in the mouse model, and further revealed that selected galectins bind strongly to IAV and S. pneumoniae and that the neuraminidase treatment or infection with influenza virus increased galectin-mediated S. pneumoniae adhesion to the cell surface.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), trypsin, and neuraminidases from Arthrobacter ureafaciens (Linkage specificity: a2–3,−6,−8,−9), Clostridium perfringens (a2–3,−6,−8), and S. pneumoniae (α2–3) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), or QA-bio (Palm Desert, CA), respectively. Influenza neuraminidase N2, and anti-PR8 antibodies were obtained from BEI Resources (Manassas, VA). Xanthomonas manihotis galactosidase (p1–3) was purchased from New England BioLabs Inc (Ipswich, MA). Capsular pneumococcal polysaccharides type I and type XIV were purchased from MiraVista Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) from influenza A H1N1 (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934) was purchased from Sino Biological (Beijing, China). Antibodies against galectin-1 (Gal1) and galectin-3 (Gal3) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). FITC-labeled peanut agglutinin (FITC-PNA) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Antigen retrieval solution was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Protease inhibitor cocktail set I, β-mercaptoethanol, and 100X penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Dialysis tubing (MW:6–8000) was purchased from Spectrum Laboratories (Rancho Dominguez, CA). TRIzol was obtained from Invitrogen (Camarillo, CA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Cellgro (Manassas, VA). Prestained broad range protein markers and anti-HA tag antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-Streptococcus pneumoniae antibody was purchased from ProSci Inc. (Poway, CA). PD Mini Trap G10 was purchased from GE Healthcare (Pittsburgh, PA). Mini Protean TGX precast gels, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), resolving buffer, and stacking buffer were all purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). “One minute” western blot stripping buffer was obtained from GM Biosciences (Frederick, MD). Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was purchased from Millipore Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Western Lightning Plus-ECL was purchased from PerkinElmer, Inc, (Waltham, MA). Molecular biology grade agarose was purchased from Denville Scientific Inc (Metuchen, NJ). Dream Taq PCR master mix (2X) and Revertaid first strand cDNA synthesis kit were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Quality biological Inc (Gaithersburg, MD). Oligonucleotide primers for RT-PCR were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich. Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

2.2. Animals, and human airway epithelial cell primary cultures and cell lines

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). A549 cells (human alveolar type II epithelial cell line derived from a lung adenocarcinoma; ATCC: CCL-185, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS supplemented with 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin as described (Lillehoj et al. 2012). Human primary small airways epithelial cells (SAECs; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were a generous gift from Dr. S. E. Goldblum, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine. SAEC were cultured in predefined small airway growth medium (Lonza) containing hydrocortisone, human EGF, epinephrine, transferrin, insulin, retinoic acid, triiodothyronine, and fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin as described (Hyun et al. 2011).

2.3. Influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae

The A/PuertoRico/08/1934 (PR8) virus was originally from Dr. Pete Palese (Mt. Sinai Medical Schoo, NY), where it was grown in allantoic fluid of 10 day-old pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs, aliquoted and stored in −80 °C. The viral titers of the viral stock were determined as described (Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). The S. pneumoniae (ATTC; Manassas, VA) serotype III (Sp3) isolate was grown in Todd Hewitt broth at 37 °C plus 2% CO2 overnight, aliquoted into equal volumes of glycerol, and stored at −80 °C.

2.4. Expression, purification, carbamidomethylation, and biotinilation of recombinant human galectins

Recombinant human galectin-1 (rhGal1) and human galectin-3 (rhGal3) were expressed using the pT7 (ML-1) and pET30 Ek/Lic vectors in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen; Billerica, MA), with induction by 0.1 mM isopropyl D-thiogalactoside at 23 °C for 16 h in 3 liters of LB medium containing 100 µg/ml amphicilin and 30 µg/ml kanamycin. The bacteria were lysed with Bugbuster (Novagen) containing 1 mM PMSF and 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) for 30 min on ice, centrifuged, and the clear supernatant, which contained approximately 80% of the recombinant galectin, was collected. The supernatant was loaded onto a column packed with 4 ml of lactose-Sepharose. After washing the column thoroughly [for rhGal1: washing buffer; 1:10 PBS, 0.07% 2-ME (PBS (1:10)/2-ME; for rhGal3 washing buffer was 0.07% 2-ME in PBS (1X)], the rhGal1 was eluted with 0.1 M lactose in PBS (1:10)/2-ME and rhGal3 was with 0.1 M lactose in PBS (1X). From a 3-liter E. coli culture, approximately 17 mg of rhGal1 and 30 mg of rhGal3 were purified. Carbamidomethylation of the rhGal1 was performed as reported earlier (Feng et al. 2013a). The purified recombinant galectins (approximately 17 mg) were absorbed on a 1 ml of DEAE-Sepharose pre-equilibrated with PBS (1:10)/2-ME, and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with slow agitation. The resin was poured into a column and after extensive washing with PBS (1:10), the column was overlaid with 3 ml of 0.1 M iododacetamide/0.1 M lactose and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C in the dark. After washing the column with 50 mM lactose in PBS (1:10), the bound protein was eluted with PBS (1:10/0.5 M Nacl/0.1M lactose). Biotinylation of the recombinant galectins was performed according to the manufacturer instructions (Pierce).

2.5. In vitro and in vivo viral and bacterial infections

Animals were maintained in the UMB animal facility and viral or bacterial infections were performed under an approved IACUC protocol. Viral and bacterial infections in C57BL/6J mice were carried out as previously described (Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). Briefly, mice (6–8 week-old female) were anesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter; Deerfield, IL) prior to the deposition of 10–20 µl of challenge inoculum to a single nare. The inoculum was prepared one hour prior to challenge from frozen stocks of PR8 or Sp3 which were diluted to the desired challenge concentration, in sterile, endotoxin-free PBS (Biosource International, Rockville, MD). Each mouse was followed daily for weight and clinical scoring. Prospectively assigned mice were followed for survival or euthanized for tissue harvest, using sterile techniques. A549 cells grown to 60 % confluence were infected with PR8 to achieve a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Infected cells were cultured at 37 °C and the cythopatic effect (CPE) was monitored every 24 h.

2.6. Immunofluorescence analysis

Tissue sectioning and immunofluorescence staining

Immunohistochemical detection was performed on 5-µm-thick paraffin-embedded sections containing the most representative lung areas. In brief, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated through graded concentrations of ethanol and then with distilled water. Samples were heated in a microwave oven in Target Retrieval solution (according to the manufacture’s protocol), washed with PBS for 5 min and blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. Sections were incubated with FITC-PNA overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber, and examined under fluorescence microscope.

Quantification of immunofluorescence images

The fluorescence intensity of each tissue section was quantified by ImageJ version 1.39 (NIH). RGB composite images from experimental and control animals were created using AxioVision Rel. 4.6 and analyzed. Statistical analyses were carried out on the fluorescence intensity measured in five different areas.

2.7. RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultured cells or mouse tissues was extracted with TRIzol reagent. RNA was quantified in a Nanodrop Bioanalyzer at 260/280 nm. Complementary DNA was synthesized using Revertaid first cDNA synthesis kit from 1 µg of total RNA according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNAs were amplified using Dream Taq PCR Master Mix (2X) and the following primers: human galectin-1, forward, 5’-GGTCTGGTCGCCAGCAACCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGCCACACATTTGATCTTG-3′; human galectin-3, forward, 5′-CGCTCCATGATGCGTTATCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGGCACCACTCCCCCAGGC-3′; human β-actin, forward, 5′-CCGCGCTCGTCGTCGACAAC-3 ; reverse, 5 -GCTCTGGGCCTCGTCGCCC-3′; mouse galectin-1, forward, 5′-TCAAACCTGGGGAATGTCTC-3′; reverse, 5′-AGGCCACGCACTTAATCTTG-3′; mouse galectin-3, forward, 5′-GATCACAATCATGGGCACAG-3 ; reverse, 5-GCTTAGATCATGGCGTGGTT-3′; mouse β-actin, forward, 5′-GCCGGCTTCGCGGGCGACG-3′; reverse, 5′-ATGCCATGTTCAATGGGG-3′. The PCR products were fractionated on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

2.8. Enzyme treatments

Neuraminidase treatment of cultured cells

Cells were either treated with influenza N2 neuraminidase (Neu N2), S. pneumoniae neuraminidase (Neu Sp), C. perfringens neuraminidase, or a combination of equal parts of A. ureafaciens and C. perfringens neuraminidases (Neu K). Cultured A549 cells were subject to neuraminidase treatment (300 mU of neuraminidase per 1 × 106 cells in 200 µl) at 37 °C for 1 h in serum-free DMEM. After incubation, cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in serum-free DMEM for further FACS, ELISA or apoptosis assays.

Glycosidase treatment of influenza A virus hemagglutinin

Recombinant influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA; 2 mg/ml, final concentration) was incubated with C. perfringens neuraminidase (5 × 103 units /ml as final concentration in G2 buffer), X. manihotis β1–3 galactosidase (1 × 104 units /ml as final concentration in G2 buffer) or buffer only (G2 as control) at 37 °C for 1 h. In selected experiments, HA (0.2 mg/ml, final concentration) was incubated with PNGase F (20 × 103 units /ml as final concentration in G7 buffer), E. coli β1–3 galactosidase and S. pneumoniae β1–4 galactosidase (200 units /ml as final concentration in G2 buffer), or buffer only (as untreated control) at 37 °C for 16 h.

2.9. Galectin binding assay

A549 cells (6 × 106 cells) were collected in 10 mM EDTA, washed twice in 10 mM PBS buffer, pH 7.8 and treated with neuraminidase (C. perfringens, 300mU per 1 × 106 cells in 1ml) in serum free medium (DMEM) at 37 °C for 1 h. After removing the supernatant and washed three times with PBS, the control (mock treated cells) or neuraminidase treated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at RT, washed twice and resuspended in 1ml of PBS. Neuraminidase-treated and untreated cells were incubated with 15 µg/ml biotinylated rhGal1 or rhGal3 at 4°C overnight. 100 mM lactose was used as an inhibitor of Gal1 and Gal3 binding to A549 cells. Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 0.2 mg/ml Streptavidin -APC 1 h at 4 °C then washed and suspended in 500 µl of PBS pH 7.8 for flow cytometry analysis.

2.10. Apoptosis analysis

A549 cells were grown to 75% confluence in 6 well plates, then washed twice in 10 mM PBS buffer, pH 7.8 and treated with neuraminidase (Neu K; 300 mU per 1 × 106 cells, in 1ml) in serum free medium (DMEM) at 37 °C for 1 h. After removing the supernatant and washed three times with PBS, the control (mock-treated cells) or neuraminidase-treated cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM with rhGal1 or rhGal3 (15 µg/ml, final concentration) at 37 °C for 16 h. Apoptosis was quantitatively analyzed by flow cytometry using the APO-DIRECT Apoptosis Detection Kit (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry analyses were performed at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Service.

2.11. ELISA

A549 cells were grown on 96-well culture plates, and treated with neuraminidase as described in 2.8. The wells were saturated with superblock buffer followed by addition of 15 µg/ml of rhGals and/or PR8 or Sp3 particles (MOI 10). The binding of galectins or pathogens (PR8 or Sp3) to the cells was assessed using primary antibodies against galectins or pathogens followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and TMB substrate, measuring the developed color at 450 nm. To assess galectin-HA interactions, 96-well plates were coated with untreated or β-galactosidase-treated HA (10 µg/ml in PBS) for 3 h and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C and subsequently assayed for galectin binding as described above.

2.12. Western blot and galectin overlay assay

Cells were lysed with ice cold 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v Triton X, protease inhibitor (1:100), 0.1mM PMSF. The cell lysates were assayed for protein concentration at 280 nm using Nanodrop Bioanalyzer or BCA Protein Assay (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein were resolved by electrophoresis on commercial gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk and then probed with primary antibodies at 1:1000 dilutions. Next, membranes were washed in PBS-T followed by incubation with HRP-linked secondary antibody (1:3000) and the results were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents. For the galectin overlay, the membranes were blocked in 3% BSA then probed with either rhGal1 or rhGal3, with specificity controls in which the galectins had been pre-incubated with 200 mM lactose. After washed, the membranes were incubated with anti-galectin antibodies followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) and the results were visualized with ECL reagents.

2.13. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

Surface plasmon resonance measurements were carried out on a BIAcore T100 (Ge Healthcare) instrument at 25 °C. rhGal 1 and rhGal3 were immobilized on individual channel of CM5 chips until reaching 1000 response units by using amine coupling kit provided by the manufacturer. A reference channel was immobilized with ethanolamine. Binding analyses were performed by injecting a solution of analytes (HA or Sp capsular polysaccharides) over four cells at 2-fold increasing concentration in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.005% surfactant P20 at a flow rate of 20 µL/min for 120 seconds and allowed to dissociate for another 200 seconds. The surface was regenerated after each cycle by injecting 3 M MgCl2 solution for 3 min at a flow rate of 30 µL/min. Data were collected at the rate of 10 Hz. T-100 biacore evaluation software was utilized to subtract appropriate blank reference and to fit the sensorgram globally by applying a 1:1 Langmuir model. Mass transfer effects were checked by the tc values displayed by the T-100 biacore evaluation software. No significant mass transportation effects were observed. In case of SP polysaccharides, the binding points were collected at the end of the association phase and binding signals were plotted against the logarithm of analyte concentration and KD/EC50 value was calculated from the dose response curve using GraphPad Prism.

2.14. Bacterial adhesion to neuraminidase-treated or PR8-infected A549 cells

A549 cells grown on the 10 cm plates were infected with PR8 (MOI 5) for three days, or treated with neuraminidase (Neu K, Neu Sp, or Neu N2; 300mU per 1 × 106 cells in 1ml at 37 °C for 1 h. After the treatment, cells were washed three times with PBS then incubated in DMEM serum free medium with Sp3 (MOI 10) or with Sp3 preincubated with rhGals (15 µg/ml, final concentration). Bound bacteria were released in water then plated on 5% sheep’s blood agar plates. The colony forming units (CFU) were counted after 24 h.

2.15. Statistical analyses

The protein or gene expression results were quantified using Image J software. Statistical analyses were performed by the Student’s t test for comparison of non-paired samples. All results with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Our work and that of others showed that galectins can function as PRRs for microbial pathogens, but in some cases the host-pathogen co-evolutionary process has led to the subversion of the galectins’ PRR functions to facilitate microbial attachment and entry into the host (reviewed in Vasta 2009). In this study, we explored the possibility that galectins expressed in lung tissues might recognize the influenza virus and S. pneumoniae, and through their interactions with galectin ligands newly exposed on the airway epithelial cells by the activity of viral or bacterial neuraminidases, enhance pneumococcal adhesion.

3.1. IAV and pneumococcal infections modulate galectin expression and secretion in the murine lung

We first examined the expression of Gal1 and Gal3 in lung tissues and their secretion into the bronchoalveolar space in mice that had been exposed to a sublethal dose of PR8, followed by a sublethal Sp3 challenge, according to the protocol we reported elsewhere (Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). Changes in galectin transcripts and protein levels were assessed by RT-PCR and western blot, respectively, in both tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) collected from euthanized mice, and representative results are illustrated in Fig 1. Gal1 expression decreased to 40% during the early acute phase of PR8 infection (Fig.1A, PR8 3d) until the end of the recovery period (Fig.1A, PR8 7d-14d) compared to the placebo controls. The Gal1 transcript levels remained significantly lower by the end of the recovery period (Fig.1A, PR8 14d), and the Sp3 challenge at day 14 after PR8 infection significantly increased them within 1h post-challenge (Fig.1A, PR8 14d + Sp3 1h). In contrast, the Gal3 transcripts increased 25% during early acute phase of PR8 infection (Fig.1A, PR8 3d), followed by a retraction to the control levels throughout PR8 infection (Fig.1A, PR8 7d-14d). The Sp3 challenge resulted in a modest increase in Gal3 transcript levels (up to 20%), as compared to the control or influenza-recovered animals (Fig.1A, PR8 14d + Sp3 1h or 18h). The Gal1 protein levels in lung tissues, however, showed a more dramatic profile, with a significant reduction in the early acute infection that paralleled the reduction in Gal1 transcript levels, followed by up to a 5-fold increase during the maximum acute illness and early recovery periods (Fig.1B, PR8 7d and PR8 10d). This was followed by a sharp decline to the control level during full recovery time (Fig.1B, PR8 14d). The subsequent Sp3 challenge sharply increased the Gal1 protein levels up to 8-fold at 18 h post-Sp3 challenge (Fig.1B, PR8 14d + Sp3 18h). In contrast, the Gal3 protein levels increased sharply during the early PR8 infection (Fig.1B, PR8 3d), followed by a gradual retraction to the control levels at the end of the influenza recovery period (Fig.1B, PR8 14d). The subsequent Sp3 challenge yielded a rapid 6-fold increase in Gal3 (Fig.1B, PR8 14d + Sp3 1h) followed by a decline to the control levels within 18h of the bacterial challenge (Fig.1B, PR8 14d + Sp3 18h).

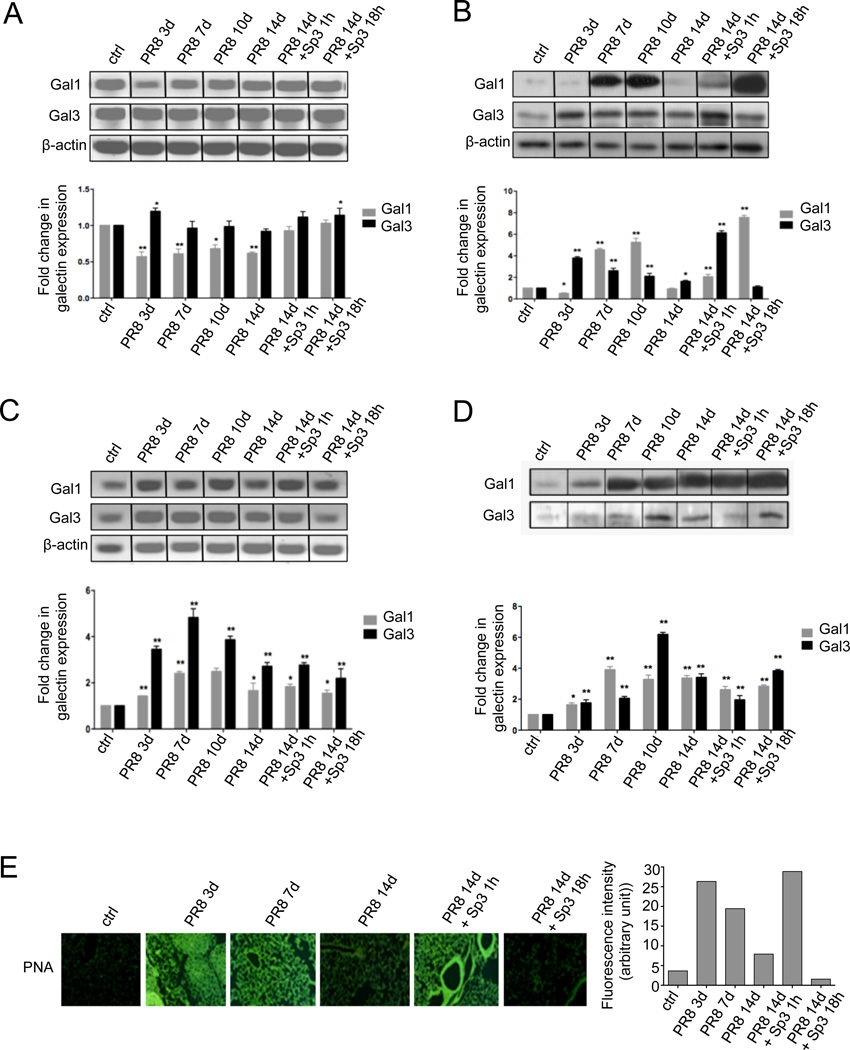

Fig. 1. Galectin expression and release, correlated with changes in glycosylation in the mouse lung during the progression of influenza (PR8) and pneumococcal (Sp3) infections.

The mice were infected with influenza strain PR8 followed by a secondary bacterial infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp3) after 14 days. Each group of mice, ranging from two to four animals, was euthanized according to the following schedule: 3 days post-PR8 (PR8 3d), 7 days post-PR8 (PR8 7d), 10 days post PR8 (PR8 10d), 14 days post PR8 without Sp3 challenge (PR8 14d), 14 days post PR8 and 1 hour post Sp3 challenge (PR8 14d + Sp3 1h), 14 days post PR8 and 18 hours post Sp3 (PR8 14d + Sp3 18h), ctrl: non-challenged mice. Transcript levels of galectin-1 (Gal1) and galectin-3 (Gal3) were assessed by RT-PCR in lung tissues (A) or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells (B). Protein levels of selected galectins (Gal1 and Gal3) were assessed by Western blot in lungs (C) or BAL fluid (D) collected from control (non-challenged) or challenged groups of mice. (E) Sialylation status of lung tissues was assessed by immunofluorescence with FITC-PNA, which revealed the exposed galactosyl moieties. Bar graphs represent fold change in galectin transcript or protein levels from challenged mice in comparison with unchallenged mice, normalized to β-actin Images and the bar graphs are representative data from at least two independent experiments. *p <0.05; **p<0.001, non-paired Student’s t test.

We also examined the presence of Gal1 and Gal3 in the airway environment by analyzing the cellular and soluble fractions of the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in the experimental and control animals. Analysis of the total RNA extracted from the BAL pellet for Gal1 and Gal3 revealed that in contrast with the lung tissues, transcripts for both galectins increased sharply upon PR8 challenge, and continued to increase (Gal1, 3-fold; Gal3, 5-fold) up to the end of the maximum acute illness (Fig.1C, PR8 7d) with Gal3 transcript levels consistently doubling those of Gal1. These levels decreased gradually during the influenza recovery period (Fig.1C, PR8 14d), but as compared to the controls they remained at least 2- and 3-fold higher for Gal1 and Gal3, respectively. Upon the Sp3 challenge, no major changes were observed, except for a modest decrease as compared to the full recovery period (Fig.1A, PR8 14d + Sp3 1h or 18h). The Gal1 protein levels in the BAL fluid showed a gradual increase during the PR8 infection period, with a peak (4-fold increase) at the maximum acute flu (Fig.1C, PR8 7d), declining thereafter to about 2-fold relative to the controls, and raising again (3-fold) at the 18h time point upon Sp3 infection. Although Gal3 also increased gradually in the BAL fluid upon PR8 infection, the protein levels peaked later (early recovery phase; Fig.1D, PR8 10d) and were comparatively higher (about 7-fold respect to the controls). Similar to Gal1, the Gal3 protein levels increased significantly 18h upon Sp3 challenge (Fig.1D, PR8 14d + Sp3 18h).

3.2 IAV and pneumococcal infections in the murine lung modify the cell surface glycosylation

Cell surface sialic acids in the airway epithelia are key to adhesion and dissemination of influenza virus (Air 2014; de Graaf and Fouchier 2014; Edinger et al. 2014). Viral and bacterial neuraminidases can cleave the terminal sialic acids on cell surface oligosaccharides thereby exposing subterminal galactosyl moieties, that are the preferred ligands for galectins, released not only by the airway epithelia but also by multiple cell types in the lung tissues. Thus, we examined the possibility that the viral neuraminidase could affect both the sialylation status of the epithelial cells and the expression of endogenous galectins. Changes in cell surface glycosylation were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with lectins that recognize galactosyl moieties (PNA) (Fig. 1E). In the lung tissues collected from the unchallenged (control) mice a very weak PNA signal was observed, revealing extensive sialylation of the surface galactosyl moieties (Fig.1E, ctrl). PNA staining was dramatically increased in the PR8 infected mice both during the early and maximum acute illness (Fig.1E, PR8 3d-7d). During the recovery period, the PNA staining patterns appeared to return close to that of the controls (Fig.1E, PR8 14d), suggesting re-sialylation of the cell surface glycans, and masking of the exposed galactosyl moieties. The Sp3 challenge of the influenza-recovered mice led to rapid and extensive desialylation (Fig.1E, PR8 Sp3 1h) similar to that observed upon PR8 challenge, which was only partially re-sialylated after 18h post SP3 challenge (Fig.1E, PR8 Sp3 18h).

3.3. The galectin repertoire of the human airway epithelial cell line A549 is similar to that of airway epithelial primary cells (SAEC), and murine lung tissue

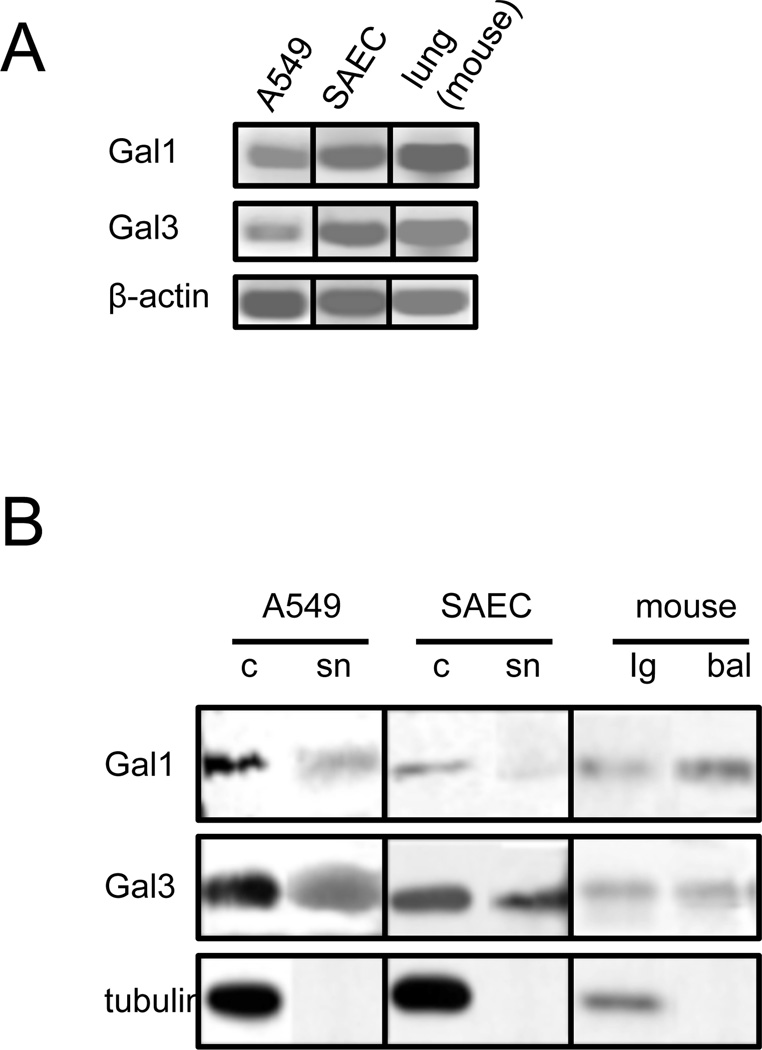

To enable in vitro experiments on epithelial cells that would allow us to examine in detail the above observations under controlled conditions, we examined the galectin repertoire of the airway epithelial cell lines A549, with particular focus on Gal1 and Gal3, and compared it with those from airway epithelial primary cells (SAEC) and lung tissues. The Gal1 and Gal3 transcript levels in the A549, SAEC, and mouse lung tissues were virtually identical (Fig.2A). Furthermore, the Gal1 and Gal3 protein levels in cells and lung tissue, and their secretion to the extracellular space (Fig.2B “sn” and “bal”) were also very similar, thereby validating the proposed A549 cell line as an in vitro model system.

Fig. 2. Expression of galectins in epithelial cell cultures and mouse lung tissue.

Transcript (A) or protein (B) levels of selected galectins (Gal1 and Gal3) were assessed with RT-PCR or Western blot, respectively, in lung carcinoma epithelial cells (A549), small airway epithelial cells (SAEC), or mouse lung tissues (lg). RT-PCR was performed with the total RNA extracted from A549, SAEC, or mouse lungs. Western blot was performed from cell lysate (c), culture supernatant (sn), lung tissue lysates (lg), or bronchoalveolar lavage (bal).

3.4. In vitro exposure of A549 cells to PR8 or neuraminidase modulates galectin expression and secretion

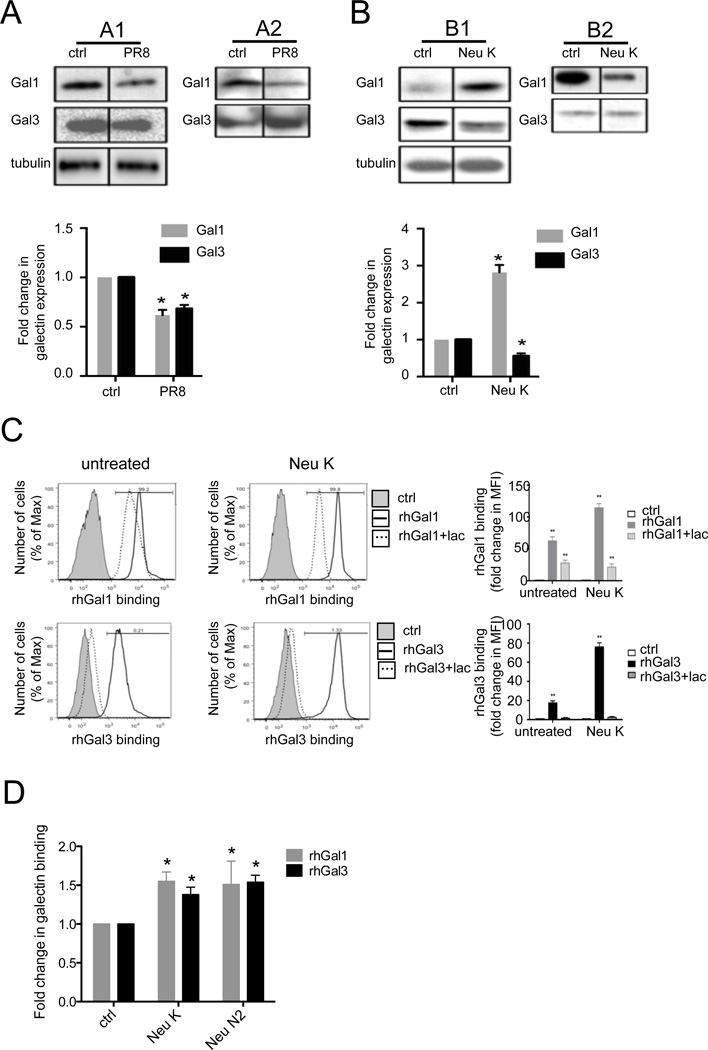

Based on the results above, we examined whether the in vitro PR8 exposure of the A549 cells had similar effects on galectin expression and secretion as that of PR8 infection in vivo (Fig. 3A). Infection of A549 cells with PR8 reduced expression of both Gal1 and Gal3 relative to the uninfected cells (Fig. 3A1). The reduced level of Gal1 in the culture supernatants was consistent with the reduction in the cell lysates, whereas in contrast, secretion of Gal3 was increased upon PR8 infection (Fig. 3A2). Based on the results of PR8 in vivo infection (Fig 1E) that showed an increase in PNA staining, suggestive of the cleavage of cell surface sialic acids, we examined in vitro the potential effects of a combination of two commercial bacterial neuraminidases from A. ureafaciens and C. perfringens (Neu K) on Gal1 and Gal3 expression and secretion by A549 cells, as a model for the activity of IAV or pneumococcal neuraminidase on the airway cell surface (Fig. 3B). Treatment of the cells with Neu K enhanced Gal1 expression, but decreased Gal3 expression relative to the unexposed controls (Fig. 3B1). However, secretion of Gal1 decreased in the neuraminidase-treated cells, whereas no detectable changes were observed for the secretion of Gal3 (Fig. 3B2).

Fig. 3. In vitro effect of PR8 and neuraminidase exposure of A549 cells on expression and binding of galectins to A549 cells.

Exposure of A549 cells to PR8 (A) or neuraminidase (B) modulates galectin expression (A1 and B1) and secretion (A2 and B2). A549 cells were infected with PR8 (MOI 5) for 72h (A), or treated with a bacterial neuraminidase cocktail (Arthrobacter ureafaciens and Clostridium perfringens; Neu K) (B). Galectin (Gal1 and Gal3) expression or secretion was assessed from cell lysates (A1 and B1) or culture supernatant (A2 and B2) with Western blot. Bar graphs show fold changes of galectin expression from PR8-infected or neuraminidase-treated cells (Neu K) in comparison with untreated cells (ctrl) normalized to tubulin. (C) Neuraminidase-treated (Neu K) or untreated (ctrl) cells were incubated with 15 µg/ml of biotinylated rhGal1, rhGal3, or galectins in the presence of lactose (0.1M) (Gal1+lac, Gal3+lac), followed by streptavidin-APC for flow cytometry analysis. The exogenous galectin binding to A549 cells was normalized to A549 cells without exogenous galectin (ctrl). (D) Effects of influenza viral neuraminidase (Neu N2) and bacterial neuraminidases (Arthrobacter ureafaciens and Clostridium perfringens; Neu K) on galectin binding to A549 cells. A549 cells grown in ELISA plates were subject to neuraminidase treatment (Neu K or Neu N2), followed by incubation with 15 µg/ml of exogenous rhGal1 or rhGal3. Galectin binding to the cells was assessed using primary antibodies against Gal1 or Gal3 followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The galectin binding levels to neuraminidase-treated cells were normalized to the binding to the untreated cells (ctrl). Data shown and the bar graphs are representative data from at least three independent experiments. *p <0.05; **p<0.001, non-paired Student’s t test.

3.5. Neuraminidase treatment of the A549 cells increases the carbohydrate-specific binding of rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the surface and modulates their apoptotic properties

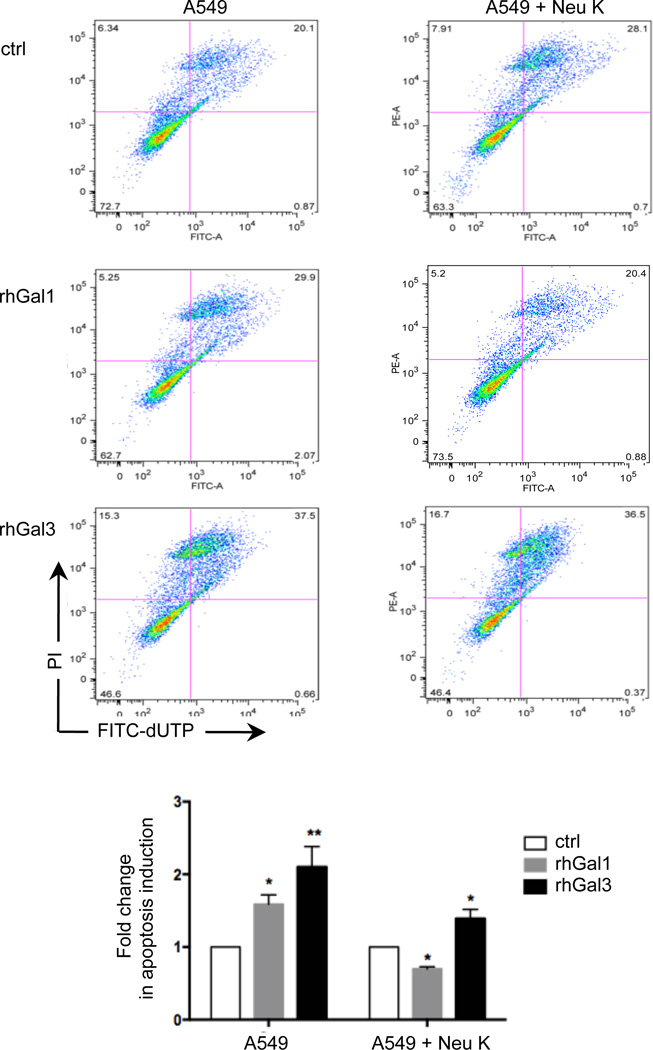

Under the possibility that the secreted galectins could bind to the newly exposed galactosyl moieties on the A549 surface by the neuraminidase activity, we quantitatively assessed by flow cytometry the potential effect of Neu K treatment on the binding of biotinylated rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the A549 surface. The specificity of the binding was examined by testing galectin binding in the presence of lactose. The in vitro exposure of the A549 cells to Neu K increased the binding of rhGal1 and rhGal3 by 2- and 4-fold respectively, and lactose (100mM) reduced the binding by at least 50% relative to the control values for Gal1 and nearly 100% for Gal3 (Fig. 3C). We subsequently tested the effects(s) of exposure of the A549 cells to influenza neuraminidase (Neu N2), to find out if its activity had similar effects on galectin binding to the A549 cell surface as we had observed with the bacterial Neu K that we used as a model. The results revealed that treatment of the A549 cells with either Neu N2 or Neu K increases the binding of both rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the A549 cells by approximately 1.5-fold over the untreated controls (Fig 3D). In light of these results we examined the possibility that their well-established pro-apoptotic activities upon binding to the cell surface could be also affected by the neuraminidase treatment. Both rhGal1 and rhGal3 displayed pro-apoptotic activity for the untreated A549 cells (Fig. 4). When the cells were pre-treated with Neu K, however, the activity of rhGal3 was reduced to about 30% relative to that for untreated cells, whereas the proapoptotic activity of rhGal1 was reversed to moderately anti-apoptotic (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Effect of neuraminidase treatment on the pro-apoptotic activity of galectin-1 and galectin-3.

A549 cells treated with bacterial neuraminidases (Arthrobacter ureafaciens and Clostridium perfringens; Neu K) and untreated controls were incubated with 15 µg/ml of exogenous rhGal1 or rhGal3 and analyzed by TUNEL assay in flow cytometry for apoptosis. The apoptosis percentage in A549 cells in the presence of rhGal1 or rhGal3 was normalized to A549 cells without exogenous galectin (ctrl). Data shown and the bar graphs are representative data from at least three independent experiments. *p <0.05; **p<0.001, non-paired Student’s t test.

3.6. Galectin-1 and −3 bind to selected glycoproteins of influenza virus

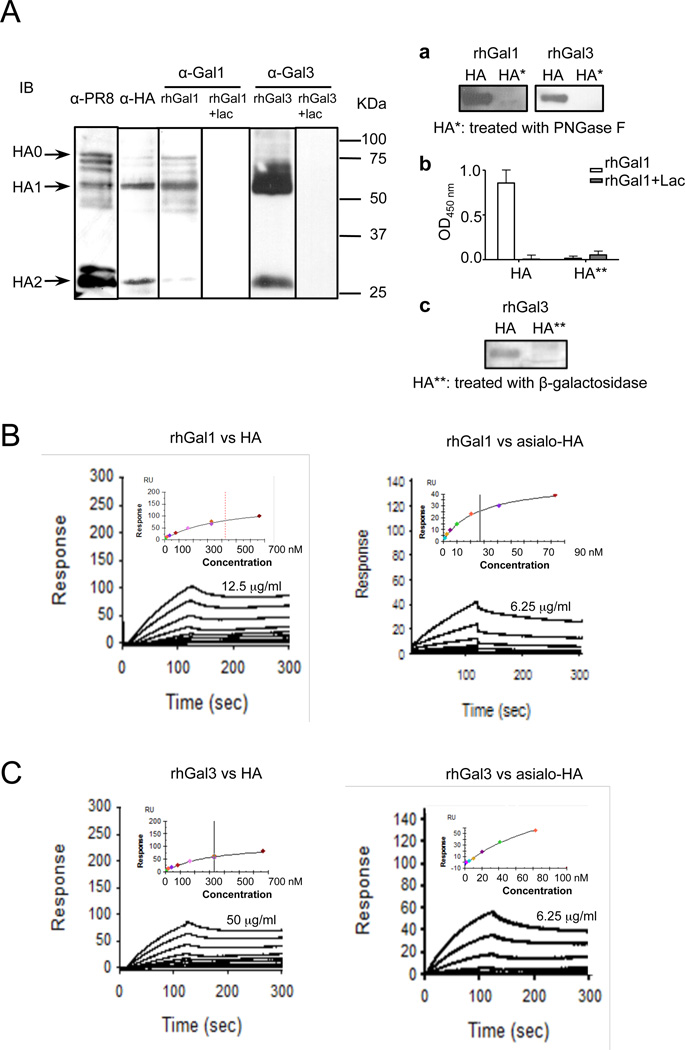

As the influenza neuraminidase enhanced galectin binding to the airway epithelial cell surface, we tested whether galectins secreted to the airway space could contribute to the adhesion of influenza virus to the airway epithelial cell surface by cross-linking of the pathogens to host cell glycans. Thus, we investigated whether rhGal1 and rhGal3 directly recognized and bound to PR8 glycoproteins that may be exposed on the viral surface. A preliminary capture ELISA, in which plates were coated with either rhGal1 or rhGal3, revealed that both galectins bound to the intact PR8 virions (results not shown). Subsequently, a Western blot with an anti-PR8 antibody and a galectin overlay western blot with the whole PR8 indicated that both rhGal1 and rhGal3 strongly recognized selected viral glycoproteins, which was abolished with lactose pre-incubation (Fig. 5A). Based on their electrophoretic mobility, one of the strongest viral ligands was identified as the HA (HA1 and HA2 subunits), and further confirmed by Western blot with anti-HA antibody (Fig. 5A). Removal of N-glycans from HA by PNGase F treatment (a), or galactosyl residues by β-galactosidase treatment (b and c), completely abolished galectin binding to HA (Fig. 5A, right panel a-c), thereby confirming the carbohydrate specificity of the galectin-HA interaction. To quantitatively assess the binding affinities of rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the intact and desialylated HA we used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Fig. 5B,C). Both galectins exhibited strong binding to HA (Gal1: Kd = 425 nM; Gal3: Kd = 331nM), which was further enhanced for the desialylated form (Gal1: Kd = 28 nM; Gal3: Kd = 119 nM). No binding of Gal1 and Gal3 to the PNGase F- or β-galactosidase-treated HA was observed (Not shown).

Fig. 5. Binding of galectins to influenza PR8 virion components and effect of neuraminidase exposure.

(A) Binding of rhGal1 and rhGal3 to influenza hemagglutinin (HA0, precursor HA containing a hydrophobic signal sequence; HA1 and HA2, subunits of HA). Lysates from PR8 virus were prepared and subjected to Western blot. The total viral proteins were revealed by an α-PR8 antibody, and the viral HA by an α-HA antibody. Galectin binding was performed by overlaying membrane with rhGal1, rhGal3, and the specificity of the binding assessed by preincubation of the galectins with lactose (0.2 M) (rhGal1+lac, rhGal3+lac), followed by anti-Gal1 or anti-Gal3 antibodies, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. To confirm the carbohydrate specificity of the galectin-HA interactions, HA was treated with PNGase F (HA* in a) or β-galactosidase (HA** in b or c) and subjected to lectin blot (a and c) as described above, or ELISA (b). (B) SPR sensogram of binding rhGal1 to HA. SPR was measured with immobilized rhGal1 and using HA (left panel) or desialylated HA (right panel) as analytes. HA starts at 12.5µg/ml, with 2-fold serial dilution; asialo-HA starts at 6.25 µg/ml. (C) SPR sensogram of binding of rhGal3 to HA. SPR was measured with immobilized rhGal3 and using HA (left panel) or desialylated HA (right panel) as analytes. HA starts at 50 µg/ml, with 2-fold serial dilution; asialo-HA starts at 6.25 µg/ml.

3.7. Galectin-1 and −3 increase S. pneumoniae (Sp) binding to the surface of airway epithelial A549 cells

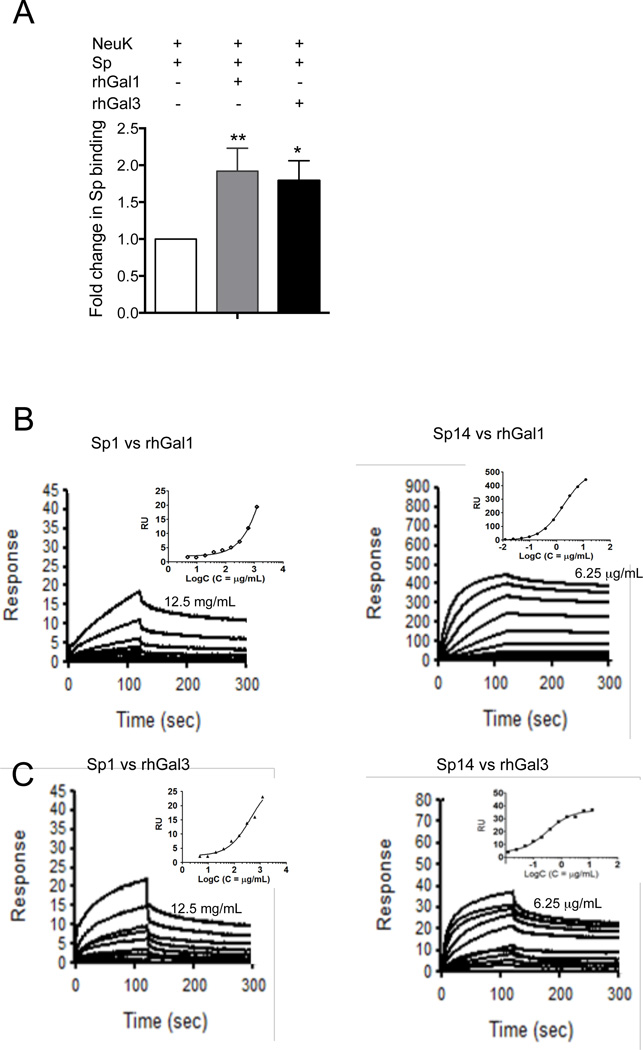

As Gal1 and Gal3 have been reported to bind to a variety of bacteria (reviewed in Vasta, 2009) such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (Mey et al. 1996), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (John et al. 2002), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gupta et al. 1997) and H. pylori (Fowler et al. 2006), and our results above indicated that after exposure to influenza neuraminidase these galectins strongly bind to the airway epithelial A549 cells, we tested whether exogenous rhGal1 or rhGal3 could bind to S. pneumoniae, crosslink the bacteria to the cell surface, and promote the adhesion of pneumococcus to neuraminidase-treated A549 cells and facilitate bacterial adhesion and infection in the lung. For this, we tested by ELISA the binding of S. pneumoniae type III (Sp3) to untreated and neuraminidase-treated A549 cells in the presence of either rhGal1 or rhGal3. The results revealed that either Gal1 or Gal3 can double the number of bacteria adhering to the A549 cell surface relative to the controls that received no exogenous galectin (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Galectin-mediated adhesion of S. pneumoniae to airway epithelial cells and binding to capsular polysaccharides.

A549 cells were grown in ELISA plates and treated with bacterial neuraminidase (Arthrobacter ureafaciens and Clostridium perfringens; Neu K). The cells were exposed for 1h to Sp3 (MOI 10) alone or Sp3 previously incubated with 15 µg/ml of rhGal1 or rhGal3. Bacterial binding to the cells was assessed using a primary anti-Streptococcus pneumoniae antibody, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The bacterial adhesion to cells in the presence of galectins was normalized to the bacterial adhesion in the absence of exogenous galectin. Data shown and the bar graphs are representative data from at least three independent experiments. *p <0.05; **p<0.001, non-paired Student’s t test. (B) SPR sensogram of binding rhGal1 and rhGal3 to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides type I and type XIV: rhGal1 and type I polysaccharide (Sp1) at starting concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, with 2-fold serial dilutions (left panel); rhGal1 and type XIV polysaccharide (Sp14) at starting concentration of 6.25 µg/ml with 2-fold serial dilutions (right panel). (C) rhGal3 and type I polysaccharide (Sp1) at starting concentration of 12.5 mg/ml with 2-fold serial dilutions (left panel); rhGal3 and type XIV polysaccharide (Sp14) at starting concentration of 6.25 µg/ml, with 2-fold serial dilutions (right panel).

3.8. Galectin-1 and −3 bind to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides

To identify the potential galectin ligands that may be responsible for the observation above, we examined whether exogenous rhGal1 and rhGal3 could bind to S. pneumoniae, and crosslink the bacteria to the cell surface. As the pneumococcal capsule polysaccharides are the most exposed glycans on the microbial surface, we tested the possibility that these could display the specific glycotopes recognized by Gal1 or Gal3. For this, we carried out a capture ELISA in which we assessed the binding of whole S. pneumoniae cells to rhGal1- or rhGal3-coated wells, and the results revealed binding to both S. pneumoniae type I (Sp1) and type XIV (Sp14), although the binding to the Sp14 was stronger than for Sp1 (results not shown). To quantitatively assess this observation we carried out SPR measurements of rhGal1 and rhGal3 binding affinities to the pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides types I and XIV. The results showed that both galectins preferentially recognized the type XIV over the type I. rhGal1 showed strong binding for the type XIV (KD = 1.8 µg/mL) whereas a weaker binding could be measured for type I (Fig. 6B). Similarly, rhGal3 showed weak binding for the type I polysaccharide (KD = 796 µg/mL), and higher affinity for the type XIV (KD = 0.4 µg/mL) (Fig. 6C).

3.9. Exposure of A549 cells to S. pneumoniae neuraminidase (Neu Sp) enhances binding of galectins to the cell surface

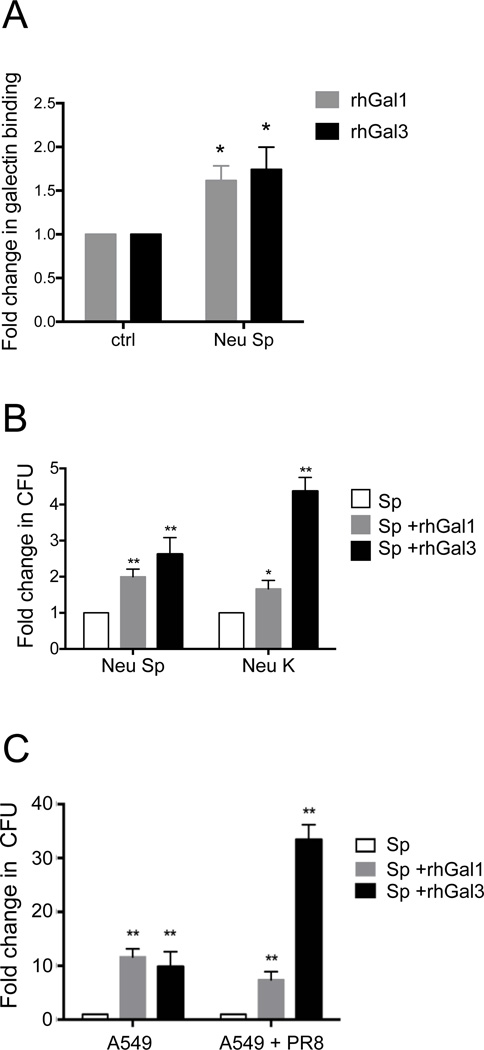

Since both influenza infection in vivo and the influenza neuraminidase treatment in vitro exposed galactosyl moieties on the airway epithelial cell surface and increased galectin binding, we tested whether upon exposure of the cells to S. pneumoniae neuraminidase (Neu Sp) could further increase galectin binding to the surface and potentially enhance adhesion of S. pneumoniae by cross-linking. The exposure of the A549 cells to Neu Sp increased the binding of both rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the cell surface by approximately 1.5- fold or above (Fig. 7A). This was similar to the increase in galectin binding observed with the treatment with Neu N2 and Neu K we had used as a model treatment (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the activity of the S. pneumoniae neuraminidase at the airway epithelial cell surface can further enhance the galectin-mediated microbial adhesion initiated by the influenza neuraminidase.

Fig. 7. Effect of S. pneumoniae neuraminidase and PR8 infection on galectin-mediated adhesion of S pneumoniae to A549 cells.

(A) A549 cells grown in ELISA plates were treated with S. pneumoniae neuraminidase (Neu Sp) or untreated (ctrl) followed by incubation with 15 µg/ml of exogenous rhGal1 or rhGal3. Galectin binding to the cells was assessed using primary antibodies against Gal1 or Gal3 followed by and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The galectin binding levels to the neuraminidase-treated cells were normalized to the untreated cells (ctrl). (B) A549 cells grown on the 10 cm plates were treated with bacterial neuraminidases (Arthrobacter ureafaciens and Clostridium perfringens; Neu K) or S. pneumoniae neuraminidase (Neu Sp), and subsequently incubated with S. pneumoniae (MOI 10) in the absence (Sp) or presence of 15 µg/ml of exogenous rhGal1 (Sp + rhGal1) or rhGal3 (Sp + rhGal3). The bound bacteria were released in water then quantified after 24h incubation on 5% sheep’s blood agar plates by counting colony forming units (CFU). The bar graphs represent the fold change of CFU from galectin-mediated Sp3 adhesion compared to the Sp3 adhesion in the absence of exogenous galectin. (C) A549 cells grown on the 10 cm plates were exposed to PR8 (MOI 5) for 72 h, then incubated with Sp3 (MOI 10) without (Sp) or with 15 ug/ml of exogenous rhGal1 (Sp + rhGal1) or rhGal3 (Sp + rhGal3) for bacterial adhesion. The colony forming units (CFU) released from bound bacteria were counted as described above. The bar graphs represent the fold change of CFU from galectin-mediated Sp adhesion compared to the Sp adhesion in the absence of exogenous galectin. Data shown and the bar graphs are representative data from at least three independent experiments. *p <0.05; **p<0.001.

3.10. Exposure of the A549 cells to pneumococcal neuraminidase enhances Gal1- or Gal3-mediated adhesion of S. pneumoniae

Since both the IAV Neu N2 and the Neu Sp increased the binding of rhGal1 and rhGal3 to the cell surface, we examined the possibility that upon exposure of the A549 cells to either the influenza or the S. pneumoniae neuraminidases (Neu N2 or Neu Sp, respectively) the secreted galectins could further enhance the binding of Sp3 to the host cell surface by cross-linking the bacterial capsular polysaccharides to the newly uncovered galactosyl moieties on the airway cell surface. The results (Fig. 7B) showed that both the Neu K and the Neu Sp enhanced the adhesion of Sp3 to the A549 cells, and that the bacteria remained viable upon adhesion. It was noteworthy that rhGal3 significantly increased pneumococcal adhesion from 20% to 150% more effectively than rhGal1 (Fig. 7B).

3.11. Extracellular Gal3 enhances pneumococcal adhesion to PR8-infected A549 cells

We then examined whether the PR8 infection of A549 cells could have a similar effect to the neuraminidase treatment in enhancing adhesion of S. pneumoniae to A549 cells by galectins present in the extracellular space. The results revealed that the presence of either rhGal1 or rhGal3 in the extracellular environment led to a 10-fold enhancement of Sp3 adhesion to the A549 cell surface. However, when the cells had been infected with influenza virus, while the rhGal1-mediated pneumococcal adhesion was similarly enhanced as in the uninfected cells, the presence of rhGal3 enhanced the adhesion above 30-fold (Fig 7C).

4. Discussion

Galectins modulate multiple aspects of both innate and adaptive immunity, including leukocyte chemotaxis, migration and activation (Stowell et al. 2007), B cell development (Gauthier, L. et al. 2002; Barrionuevo et al. 2007), T cell apoptosis (Hernandez and Baum 2002; Hsu et al. 2006), and other developmental and regulatory aspects of the immune responses (Rabinovich et al. 2002; Leffler et al. 2004; Vasta et al. 2004; Hsu et al. 2006; Barrionuevo et al. 2007; Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). More recently, it has become increasingly apparent that galectins can function as PRRs by binding glycans on the surface of potentially pathogenic microbes (Vasta 2009), and also as effector factors by killing potentially pathogenic bacteria (Vasta 2009). Therefore, galectins can regulate immune functions by binding to both endogenous (‘self’) glycans, and microbe-associated (‘non-self’) glycotopes. Functions of galectins as PRRs, however, can be subverted by some microbial pathogens for host attachment and entry (Rabinovich et al. 2007; Vasta 2009). In a previous study we established a mouse model as a faithful reproduction of human clinical scenario to examine the effects of innate immunity components in post-influenza secondary pneumococcal superinfection. In this model, the mice that recovered from a sub-lethal dose of influenza challenge are more susceptible to pneumococcal challenge than the naïve mice (Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). In the present study, we explored in the aforementioned mouse model and in an in vitro system the expression and secretion of Gal1 and Gal3 by the airway epithelial cells upon influenza infection and their potential contributions to pneumococcal adhesion to airway epithelial cells.

Assessment of Gal1 and Gal3 expression in mice that had been subject to PR8 and Sp3 infectious challenge following the established protocols (Chen, W. H. et al. 2012) revealed significant changes at both transcriptional and translational levels in the lung tissue, as well as in the secretion of galectins into the bronchoalveolar space. Gal1 and Gal3 protein levels in the BAL increased sharply from early to acute influenza illness, with a significant increase in Gal3 soluble protein observed post-pneumococcal challenge most likely secreted by the epithelial cells and the leukocytes that have reached the bronchoalveolar space. In addition to their expression by airway epithelia, galectins are also expressed in various cell types involved in innate and adaptive immune responses, including neutrophils, eosinophyls, lymphocytes, and macrophages that transmigrate into the bronchoalveolar space upon infectious challenge in the lung (Farnworth et al. 2008; See and Wark 2008; Rabinovich and Toscano 2009; Davicino et al. 2011; Tam et al. 2011; Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). Our results showed that Gal1 and Gal3 protein levels in the BAL supernatant reflected the changes in the transcript levels of Gal1 and Gal3 in the BAL pellet, consisting mostly of exfoliated epithelial cells, together with the innate and adaptive immune cells mentioned above (Farnworth et al. 2008; See and Wark 2008; Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). Both Gal1 and Gal3 can mediate protective functions during microbial infections (Farnworth et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2011). Gal3 can function as an adhesion molecule, and during airway infection it mediates neutrophil recruitment into the lung in an integrin-independent manner (Sato et al. 2002; Nieminen et al. 2008). In contrast, Gal1 directly inhibits hemagglutination activity and infectivity of influenza A virus by binding its envelope glycoproteins, and suppresses virus-induced cell death (Yang et al. 2011).

Pathogen-host interactions can be modulated by the cell surface glycosylation resulting from glycosyltrasferase or glycosidase activity. In turn, the pathogens can actively modify the exposed carbohydrate moieties on the cell surface to facilitate adhesion and entry into the host. For example, the cleavage of terminal sialic acid residues is one of the most important cells surface glycan alteration in modulating the adhesion of the pathogens to the host (Tong et al. 1999; Gubareva et al. 2000; Tong et al. 2001; McCullers and Bartmess 2003). In this regard, our glycotyping of histological sections of lung tissues during the course of experimental influenza and bacterial infection revealed substantial changes in the sialylation status. The unchallenged mice demonstrated extensive sialylation of the airway epithelial surface, whereas dramatic desialylation occurred in the PR8- and pneumococcal-infected mice, most likely as a result of the viral and bacterial neuraminidases respectively. The complementing activities of HA and NA play key roles not only for IAV adhesion and entry into the host cells, but also for virion release (de Vries et al. 2012). The influenza HA is a glycoprotein present on the viral surface that is responsible for virus binding to the sialic acid moieties on the host membrane (Kaverin et al. 2000; Matrosovich and Klenk 2003). The epithelium from upper respiratory tract and lung is heavily decorated with α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acids (Nelli et al. 2010), and the activity of microbial neuraminidase dramatically alters cell surface glycosylation, modulating microbial invasion and immune response. The influenza NA can cleave both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acids, with a marked preference for the non-human α2,3 linkage over the presumptive human receptor, α2,6-linked NeuNAc. (Gulati et al. 2005). While α2,3-sialyllactoside is a better substrate than α2,6-sialyllactoside for both human A(H3N2) and avian A(H5N2) neuraminidase (Pourceau et al. 2011), S. pneumoniae NA acts on both α2,3- and α2,6-sialyllactoside (Scanlon et al. 1989; Berry et al. 1996). During pneumonia infection in chinchilla, S. pneumoniae NA removes terminal sialic acids and exposes galactosyl and GlcNAc moieties in the airway (Tong et al. 2001). In the PR8-infected mice, the expression of galectins, in particular Gal1, was upregulated not only in the lung tissue but also in the cells present in the bronchoalveolar space. A similar increase in Gal1 expression had been observed in mice inoculated with influenza A/WSN/33 strain (Yang et al. 2011). The concurrent availability of galactosyl moieties unmasked by the viral neuraminidase activity on various cell surface glycoproteins and the upregulated expression and secretion of galectins suggests alternative modulatory dose-response effects on innate and adaptive immune responses, for example, blocking viral adhesion by masking viral receptors, preventing the release of the viral particle, or facilitating viral adhesion by crosslinking the virus to the cell surface(Gauthier, S. et al. 2008; Mercier et al. 2008; Vasta 2009) .

The observation that the expression and secretion of the galectin repertoire of the airway epithelial cell line A549 is similar to that of airway epithelial primary cells SAEC and the mouse lung tissue confirmed its suitability as a model for in vitro studies. The A549 cell line is derived from a human alveolar basal epithelial adenocarcinoma (Giard et al. 1973), grows as an adherent monolayer and has been used extensively as an airway epithelial cell model for physiological, molecular and pharmacological studies (Lieber et al. 1976; Jamaluddin et al. 1996; Chakrabarti et al. 2010)

In vitro exposure of A549 cells to PR8 moderately downregulated the expression of Gal1 and Gal3. Although the reduced level of Gal1 in the culture supernatant suggested that the downregulated expression was the cause of a decrease in Gal1 secretion, this was not consistent for the in vivo results on Gal1 for which increased secretion was observed upon PR8 infection. The increased Gal1 levels observed in vivo may originate in other cell types, such as macrophages, neutrophils, or lymphocytes, which migrated into intrapulmonary space during PR8 infection. The increased Gal1 levels in the BAL support this possibility, since in the infected lung numerous macrophages and neutrophils are present in the bronchoalveolar space (Perrone et al. 2008; Fukuyama and Kawaoka 2011). In contrast, the exposure of A549 cells to PR8 increased the secretion of Gal3. This was consistent with the in vivo results, in which levels of Gal3 remained high in the bronchoalveolar space throughout the PR8 infection and recovery periods.

The exposure of the A549 cells to either bacterial and viral neuraminidases significantly increased the specific binding of both Gal1 and Gal3 to the cell surface. The differential inhibition of the binding of Gal1 and Gal3 to the cell surface by lactose suggested that the stronger binding of Gal1 to cell surface glycotopes, most likely polylactosamines, cannot be fully outcompeted by the addition of soluble lactose as it occurs for Gal3 binding. The activity of neuraminidase on A549 cells also quali- or quantitatively modulated the apoptotic properties of the bound galectins. Gal1 exhibits anti-inflammatory activity protecting the cells from damaging events, whereas Gal3 exhibits a pro-inflammatory effect (Stowell et al. 2008), but in the extracellular space, both Gal1 and Gal3 display pro-apoptotic activity (Dhirapong et al. 2009; Chen, H. L. et al. 2014). Particularly noteworthy was the significant reduction of the proapoptotic activity of Gal1 for the neuraminidase-exposed cells, which could be due to the additional galactosyl moieties exposed by the neuraminidase treatment are cross-linked by Gal1, and triggers a quantitatively different signal, or by Gal1 binding to de novo glycotopes unmasked by the neuraminidase activity. From the functional standpoint, the host galectin-mediated pro-apoptotic responses can be considered as antiviral defense mechanisms aimed at limiting viral replication and dissemination (Upton and Chan 2014). Similarly, bacterial infections can trigger a signal for apoptosis in the host in order to prevent the spread of the infection (Schmeck et al. 2004). The neuraminidase treatment of A549 cells reduced the proapoptotic effect upon exposure to the exogenous rhGal1 and rhGal3, suggesting that the viral NA would counteract the abovementioned anti-viral mechanism by preventing apoptosis of the infected cells, and providing a stable cellular environment for viral replication.

Gal1 and Gal3 exhibited strong binding to the intact virions and to HA, the virus major surface glycoprotein that mediates viral adhesion to the host cell surface, particularly upon desialylation. The participation of galactosyl moieties on N-glycans from HA as targets of galectin recognition was verified by galactosidase and PNGase F treatments. These results suggested that galectins secreted by the epithelial airway cells can potentially crosslink the virus HA to galactosyl moieties on the cell surface, and these interactions are strengthened by viral NA activity that would further unmask additional galactosides on the cell surface glycans. Recognition of viruses by galectins has been described for HIV (Ouellet et al. 2005; St-Pierre et al. 2011) and Nipah virus (Levroney et al. 2005; Garner et al. 2010). It has been proposed that, the recognition of HIV by Gal1 in the lymph node microenvironment would cross-link the virions to the T cell surface and facilitate infection (Ouellet et al. 2005; St-Pierre et al. 2011). For the Nipah virus, Gal1 binds to specific N-glycans on viral glycoproteins and aberrantly oligomerizes NiV-F and NiV-G, reduces NiV-F mediated fusion of endothelial cells, and inhibits syncytia formation (Levroney et al. 2005; Garner et al. 2010). In contrast, the binding of Gal1 to IAV would have a protective role in influenza (Yang et al. 2011), although the virion glycan recognized by Gal1 was not identified. Our study has identified HA not only as the IAV ligand for Gal1, but also revealed that Gal3 can recognize the same viral glycoprotein. The IAV HA displays oligosaccharides with silayl moieties at the non-reducing end which are cleaved by the viral NA, together with the host’s cell surface sialic acids (Bottcher-Friebertshauser et al. 2014). Similarly to the Gal1-mediated HIV adhesion to T cells in the lymph node (St-Pierre et al. 2011), both Gal1 and Gal3 would facilitate IAV infection of the airway epithelia by cross-linking the viral HA to the galactosyl moieties of the cell surface. In this scenario, the viral NA would play a dual role, allowing release of the HA while strengthening the Gal1/3 mediated interactions. Thus, this interplay among galectins, HA, and NA at the airway epithelial surface would modulate the balance between adhesion and release of the newly produce influenza virions.

Gal1 and Gal3 bind to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides (reviewed in Vasta, 2009). Our results indicating that exposure A549 cells to influenza neuraminidase increases galectin binding, strongly suggested that either Gal1 or Gal3 could promote S. pneumoniae adhesion to the influenza-infected airway epithelial cells. Indeed, our results revealed that the presence of either rhGal1 or rhGal3 c double the number of bacteria adhering to the neuraminidase-exposed A549 cell surface. ELISA and SPR studies aimed at identifying the galectin ligands on the pneumococcal surface revealed that Gal1 and Gal3 could bind to intact pneumococcus and to selected capsular polysaccharides. The significant differences in affinity of the galectins for the types I and XIV polysaccharides, revealed a clear specificity for selected pneumococcal strains. The results also confirmed that extracellular galectins can crosslink the selected pneumococcal types (type III) to galactosyl moieties on the cell surface. The cell surface of S. pneumoniae plays an important role in pathogenesis, including the initial binding to the host cellular receptors or binding to extracellular matrix (Mook-Kanamori et al. 2011; Voss et al. 2012). The capsular polysaccharide and the bacterial adhesins modulate the defense mechanism of the host by inhibiting the pneumococcal clearance and promoting bacterial adhesion (Lu and Nuorti 2010; Nuorti and Whitney 2010; Sanchez et al. 2011). These interactions are involved in the disease process by colonization and translocation across the mucosal barrier leading to intracellular dissemination within the host. Once disseminated, the pathogen induces multiple inflammatory responses, including recruitment of leukocytes to infected lesions (Hogg and Walker 1995; Tuomanen et al. 1995; Bergeron et al. 1998). Removal of sialic acid from the pneumococcal targets promotes bacterial persistence in the respiratory tract and facilitate subsequent internalization (Hammerschmidt 2006). Our observation that the S. pneumoniae neuraminidase could enhance galectin binding by de novo exposure of galactosyl moieties on the airway epithelial cell surface, suggested that an initial enhancement of the galectin-mediated pneumococcal adhesion by the influenza neuraminidase, could be further strengthened or increased by the pneumococcal neuraminidase.

It was noteworthy, however, that pneumococcal adhesion to the PR8-infected airway epithelial cells was significantly enhanced (about 3-fold) by extracellular rhGal3, whereas no differences were observed for rhGal1, suggesting a unique role for rhGal3 in the bacterial superinfection subsequent to influenza. rhGal1 plays an important role in the host defense against IAV infections, and this is buttressed by the observation that the Gal1 knockout mice are more susceptible to influenza (Yang et al. 2011). During pneumococcal infections, Gal3 can also contribute to fight the bacterial infection by promoting integrin-independent neutrophil recruitment into lung (Sato et al. 2002; Nieminen et al. 2008) and neutrophil phagocytosis (Farnworth et al. 2008), and delaying neutrophil apoptosis (Farnworth et al. 2008). This has been supported by the observation that naïve Gal3−/− mice are more susceptible to pneumococcal pneumonia (Nieminen et al. 2008).

If the pneumococcal challenge takes place upon influenza infection, however, the outcome is very different. Survival of naïve mice challenged with S. pneumoniae is significantly higher than of those previously infected with influenza (McCullers and Rehg 2002; Chen, W. H. et al. 2012). In contrast with the protective functions of Gal1 in influenza (Yang et al. 2011), our results suggest that Gal3 enhances pneumococcal adhesion to the influenza-infected epithelia, possibly facilitating infection. Furthermore, the increased galectin levels remaining in the bronchoalveolar space during the recovery from influenza infection may disrupt the immune homeostasis in the lung. Thus, instead of the protective response by Gal3 observed upon pneumococcal infection (Nieminen et al. 2008), an uncontrolled cytokine release may result from the Gal3-mediated suppression of the Th17 response (Fermin Lee et al. 2013). Such breakdown of immune homeostasis by Gal3 has been also reported for Francisella infections, in which Gal3 can induce release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-6, and IFNγ, leading to sepsis (Mishra et al. 2013).

In summary, our observations provide the rational basis for the participation of galectins in facilitating pneumococcal adhesion to previously influenza-infected cells. The multivalency of galectins resulting from their oligomerization is not only key to their cooperative binding to complex carbohydrate ligands and their ability to crosslink surface glycans and form lattices (Vasta et al. 2004), but would also enable galectins to facilitate the attachment of pathogens to the cell surface (Ahmad et al. 2004; Nieminen et al. 2007; Rabinovich et al. 2007; Vasta 2009). This subversion of galectins functions as PRRs has already been reported for the galectin-mediated attachment of viruses (Ouellet et al. 2005; Garner et al. 2010; St-Pierre et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2011), bacteria (Okumura et al. 2008), and eukaryotic parasites (Kamhawi et al. 2004). Prior studies have provided evidence that the release of sialic acid by the activity of the IAV neuraminidase promotes the adhesion of S. pneumoniae to airway epithelial cells in the form of a biofilm, that makes the pathogen less accessible to host factors and antibiotics and facilitates host invasion (Trappetti et al. 2009). More recently, it has been shown that sialic acids released by IAV neuraminidase form the airway epithelial cells constitute a nutrient source that promotes the proliferation of S. pneumoniae on the airway surfaces (Siegel et al. 2014). By demonstrating that the release of sialic acid from the airway epithelial cells by the IAV neuraminidase promotes the ability of galectins to increase the adherence of S. pneumoniae to the epithelium, our results provide a key contributory factor consistent with both aforementioned observations, that may further enhance our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the bacterial superinfection upon influenza. Furthermore, as galectins are key regulators of immune homeostasis, our results suggest the existence of an immunoregulatory network in which galectins, together with viral and bacterial neuraminidases play synergistic roles in not only “preparing the ground” for the pneumococcal adhesion, but also may determine the intensity of the pneumococcal infection and the severity of its outcome as a consequence of the loss of immune homeostasis.

Highlights.

We studied the role of galectins in pneumococcal adhesion in the lung upon influenza

After influenza, galectin-1 and −3 levels are increased in the bronchoalveolar space

Viral and bacterial neuraminidases increase galectin binding to epithelial cells

Galectin-1 and −3 bind to glycans from the influenza virus and pneumococcus

Galectin-3 enhances pneumococcal adhesion to influenza-infected airway epithelium

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants 5R01GM070589-06 from the National Institutes of Health and grants IOS-0822257 and IOS-1063729 from the National Science Foundation to GRV, grant AI095569 to MBF, NCRR grant K12-RR-023250 to WHC, grant RO1 HL086933-01A1 to ASC, and grant R01 GM080374 to LXW. We thank Dr. F. Livak (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and Flow Cytometry Shared Service, Cancer Center, SOM, UMB) for performing the FACS analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad N, Gabius HJ, et al. Galectin-3 precipitates as a pentamer with synthetic multivalent carbohydrates and forms heterogeneous cross-linked complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(12):10841–10847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Air GM. Influenza virus-glycan interactions. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;7C:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker WH, Mullooly JP. Impact of epidemic type A influenza in a defined adult population. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(6):798–811. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker WH, Mullooly JP. Pneumonia and influenza deaths during epidemics: implications for prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(1):85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrionuevo P, Beigier-Bompadre M, et al. A novel function for galectin-1 at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity: galectin-1 regulates monocyte/macrophage physiology through a nonapoptotic ERK-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 2007;178(1):436–445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron Y, Ouellet N, et al. Cytokine kinetics and other host factors in response to pneumococcal pulmonary infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66(3):912–922. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.912-922.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry AM, Lock RA, et al. Cloning and characterization of nanB, a second Streptococcus pneumoniae neuraminidase gene, and purification of the NanB enzyme from recombinant Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(16):4854–4860. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4854-4860.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottcher-Friebertshauser E, Garten W, et al. The Hemagglutinin: A Determinant of Pathogenicity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/82_2014_384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnahan AJ, Schlievert PM. Gram-positive bacterial superantigen outside-in signaling causes toxic shock syndrome. FEBS J. 2011;278(23):4649–4667. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright K. Pneumococcal disease in western Europe: burden of disease, antibiotic resistance and management. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(4):188–195. doi: 10.1007/s00431-001-0907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti AK, Vipat VC, et al. Host gene expression profiling in influenza A virus-infected lung epithelial (A549) cells: a comparative analysis between highly pathogenic and modified H5N1 viruses. Virol J. 2010;7:219. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HL, Liao F, et al. Galectins and neuroinflammation. Adv Neurobiol. 2014;9:517–542. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1154-7_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WH, Toapanta FR, et al. Potential role for alternatively activated macrophages in the secondary bacterial infection during recovery from influenza. Immunol Lett. 2012;141(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davicino RC, Elicabe RJ, et al. Coupling pathogen recognition to innate immunity through glycan-dependent mechanisms. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(10):1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf M, Fouchier RA. Role of receptor binding specificity in influenza A virus transmission and pathogenesis. EMBO J. 2014;33(8):823–841. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries E, de Vries RP, et al. Influenza A virus entry into cells lacking sialylated N-glycans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(19):7457–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200987109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries E, Tscherne DM, et al. Dissection of the influenza A virus endocytic routes reveals macropinocytosis as an alternative entry pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(3):e1001329. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhirapong A, Lleo A, et al. The immunological potential of galectin-1 and −3. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(5):360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger TO, Pohl MO, et al. Entry of influenza A virus: host factors and antiviral targets. J Gen Virol. 2014;95(Pt 2):263–277. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.059477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnworth SL, Henderson NC, et al. Galectin-3 reduces the severity of pneumococcal pneumonia by augmenting neutrophil function. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(2):395–405. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Ghosh A, et al. The galectin CvGal1 from the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) binds to blood group A oligosaccharides on the hemocyte surface. J Biol Chem. 2013a;288(34):24394–24409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.476531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Zhang L, et al. Neuraminidase reprograms lung tissue and potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2013b;191(9):4828–4837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermin Lee A, Chen HY, et al. Galectin-3 modulates Th17 responses by regulating dendritic cell cytokines. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(4):1209–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez GC, Ilarregui JM, et al. Galectin-3 and soluble fibrinogen act in concert to modulate neutrophil activation and survival: involvement of alternative MAPK pathways. Glycobiology. 2005;15(5):519–527. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]