Abstract

Background

Inhibition of breast cancer stem cells has been shown to be an effective therapeutic strategy for cancer prevention. The aims of this work were to evaluate the efficacy of koenimbin, isolated from Murraya koenigii (L) Spreng, in the inhibition of MCF7 breast cancer cells and to target MCF7 breast cancer stem cells through apoptosis in vitro.

Methods

Koenimbin-induced cell viability was evaluated using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Nuclear condensation, cell permeability, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cytochrome c release were observed using high-content screening. Cell cycle arrest was examined using flow cytometry, while human apoptosis proteome profiler assays were used to investigate the mechanism of apoptosis. Protein expression levels of Bax, Bcl2, and heat shock protein 70 were confirmed using Western blotting. Caspase-7, caspase-8, and caspase-9 levels were measured, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activity was assessed using a high-content screening assay. Aldefluor™ and mammosphere formation assays were used to evaluate the effect of koenimbin on MCF7 breast cancer stem cells in vitro. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was investigated using Western blotting.

Results

Koenimbin-induced apoptosis in MCF7 cells was mediated by cell death-transducing signals regulating the mitochondrial membrane potential by downregulating Bcl2 and upregulating Bax, due to cytochrome c release from the mitochondria to the cytosol. Koenimbin induced significant (P<0.05) sub-G0 phase arrest in breast cancer cells. Cytochrome c release triggered caspase-9 activation, which then activated caspase-7, leading to apoptotic changes. This form of apoptosis is closely associated with the intrinsic pathway and inhibition of NF-κB translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Koenimbin significantly (P<0.05) decreased the aldehyde dehydrogenase-positive cell population in MCF7 cancer stem cells and significantly (P<0.01) decreased the size and number of MCF7 cancer stem cells in primary, secondary, and tertiary mammospheres in vitro. Koenimbin also significantly (P<0.05) downregulated the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway.

Conclusion

Koenimbin has potential for future chemoprevention studies, and may lead to the discovery of further cancer management strategies by reducing cancer resistance and recurrence and improving patient survival.

Keywords: Murraya koenigii (L) Spreng, koenimbin, MCF7 breast cancer stem cells, nuclear factor kappa B, Wnt/β-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β

Introduction

Murraya koenigii (L) Spreng (known as Surabhinimba in Sanskrit), known locally as the curry leaf, is a member of the Rutaceae family and is widely distributed in South Asia.1 The leaves of M. koenigii are used in food products as a flavoring agent.2 Various parts of the plant are also used to treat dyspepsia, dysentery, chronic fever, mental disorders, nausea, dropsy, and diarrhea,1 as well as for the management of diabetes.3–5 Several carbazole alkaloids with significant biological activity have been isolated from M. koenigii.1,6,7

Established cell lines pave the way for new perspectives in genetic and biological investigations, drug resistance, and chemotherapeutic studies in which these cells more truly reflect the organs of origin and maintain many characteristics of the derived cancer tissue.8,9 Recent studies have indicated that phytochemicals have antioxidant, antiproliferative, and proapoptotic effects in leukemia and liver, lung, prostate, breast, colon, brain, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer, both in vitro and in vivo.10–19 The advantages of phytochemicals are that they are well tolerated and can be added to the diet. Moreover, phytochemicals can be taken on a long-term basis to inhibit primary tumor growth or reduce the risk of tumor recurrence.20

Recent evidence has shown that a subpopulation of tumor cells known as cancer stem cells (CSCs) are the origins of and maintain various types of cancer.21,22 Via consecutive self-renewal and differentiation, possibly regulated by signaling pathways similar to those of normal stem cells, this small population of CSCs gives rise to the bulk of the tumor.21–24 Additionally, identification of CSCs from blood and solid tumors25–33 is paving the way for future researchers to evaluate the efficacy of phytochemicals against CSCs. The Wnt/β-catenin, hedgehog, and Notch signaling pathways, among others, have been identified as key modulators of self-renewal of CSCs.23,34 Further, CSCs contribute to tumor resistance/relapse due to the inability of chemotherapy and radiation therapy to eradicate them.22,35,36

Several bioactive dietary compounds, including curcumin,37,38 quercetin, and epigallocatechin gallate,39 have been reported to potentially target the self-renewal pathways of CSCs and may provide an effective strategy to overcome tumor resistance and reduce the risk of relapse.21 The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a key role in promoting the self-renewal of breast CSCs.5 Cytoplasmic β-catenin translocates to the nucleus and is complexed with the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor, modulating the activation of Wnt target genes.21,40 Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3β, adenomatous polyposis coli, casein kinase 1α, and axin regulate intracellular β-catenin levels.41 GSK3β increases the degradation of β-catenin through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway via phosphorylation of three specific amino acids, ie, Ser33, Ser3, and Thr41.41 In this study, the efficacy of koenimbin against MCF7 breast CSCs was examined in vitro. Further, the ability of koenimbin to suppress the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

The compound koenimbin, isolated from the leaves of M. koenigii with a purity of 98.5%, was a kind gift from Mohamed Aspollah Sukari in the Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia. The chemical and physical properties of the koenimbin compound used in our work were in full agreement with previous reports.42 Cell culture medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were obtained from Gibco (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). Z-VAD-FMK, a pan caspase inhibitor, was sourced from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Cell culture

All American Tissue Culture Collection cells used in this study were a gift from Yeap Swee Keong at the Institute of Bioscience, Universiti Putra Malaysia. Cells were cultured in cell culture flasks and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. MCF7 human breast adenocarcinoma cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. MCF-10A, a non-tumorigenic epithelial cell line, was used as a control and maintained in mammary epithelial growth medium, supplemented with additives obtained from Clonetics Corporation (MEGM™ kit, catalog number CC-3150, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA). For experimental purposes, cells in the exponential growth phase of approximately 70%–80% confluence were used. The cells were routinely screened for Mycoplasma species using a GenProb detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MTT cell viability assay

The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was used to determine the viability of cells treated with koenimbin. Briefly, 1.0×104 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. On the following day, the cells were treated with various concentrations of the compound, and incubated further at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24, 48, and 72 hours. MTT solution was added at 2 mg/mL and after 2 hours of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. Dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The plates were then read using an Infinite® M200 Pro (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) at a 570 nm absorbance wavelength. Cell viability percentage after exposure to koenimbin for 24, 48, and 72 hours was calculated using a previously described method.43 The IC50 value was defined as the concentration of the compound required to reduce the absorbance of treated cells to 50% of the absorbance of dimethyl sulfoxide-treated control cells. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Isolation of candidate breast CSCs

Candidate MCF7 breast CSCs were isolated from MCF7 cells by sorting the CD44+/CD24−/low cell population using a catcher tube-based cell sorter in combination with a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur™, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cells were stained with 20 μL of the CD44 antibody and 20 μL of the CD24 antibody [CD44 mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody [clone MEM-85], fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] conjugate, CD24 mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody [clone SN3], phycoerythrin conjugate, mouse immunoglobulin G2b (FITC), mouse immunoglobulin G1 (R-phycoerythrin), all sourced from BD Biosciences] in a 5 mL tube at a concentration of 107 cells/mL. The tubes had been incubated in the dark at room temperature for 45 minutes. The CD44+/CD24−/low cell population was identified by quadrant analysis using CellQuest Pro software.

Non-adherent mammosphere formation assay

CSCs from MCF7 cells were plated in six-well ultralow attachment plates (TPP, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a density of 1,000 cells/mL of culture medium.44 The cells are able to grow and form spheres in serum-free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/F12 medium (Lonza), supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen), 1% antibiotic- antimycotic, 5 μg/mL insulin, 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 4 μg/mL gentamicin, 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Gibco), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Gibco). Every 2 days, fresh medium including the 1 mL supplements were added to each well. The primary culture of MCF7 CSCs was incubated with different concentrations of koenimbin (0, 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL) for mammosphere-forming conditions. The cells from koenimbin-treated primary mammospheres were then subcultured to secondary (second passage) and tertiary (third passage) cultures for each respective group in the absence of koenimbin. After 5–7 days in vitro, the number and size of the mammospheres were compared with the control, and images were acquired with MetaMorph 7.6.0.0 using an Eclipse TE2000-S microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Aldefluor enzyme assay

A cell population with high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ADH) activity was previously reported to enrich mammary stem/progenitor cells.23 An Aldefluor™ (StemCell Technologies, Herndon, VA, USA) enzyme assay was carried out using an ADH substrate, BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde (1 μmol/L per 106 cells), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, single MCF7 CSCs from cell cultures were incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the final result was then obtained using a flow cytometer.

Cell cycle analysis

MCF7 cells were seeded and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2, and then treated with 2.5, 5, or 10 μg/mL of koenimbin for 12 hours. The cells were then harvested, stained with a BD Cycletest Plus DNA reagent kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and subjected to cell cycle analysis using a Guava easyCyte 8HT benchtop flow cytometer (Merck, Whitehouse Station, TX, USA).

Multiple cytotoxicity assay

A Multiparameter Cytotoxicity 3 kit (Cellomics Technology, Halethorpe, MD, USA) was used to measure the six independent parameters simultaneously, including cell loss, nuclear size, morphological changes, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) changes, cytochrome c release, and changes in cell membrane permeability, as described elsewhere.45 Briefly, MCF7 cells were seeded and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2, and then treated with koenimbin for 24 hours. The MMP dye and cell permeability dye were then added to the MCF7 cells and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. MCF7 cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked with blocking buffer (1×) before probing with primary cytochrome c antibody and secondary DyLight 649-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G for 55 minutes each. Hoechst 33342 staining solution was used to stain the nucleus, and 1,000 stained cells were analyzed using the ArrayScan™ high-content screening system (Cellomics Technology). This system identifies stained cells and reports the intensity and distribution of fluorescence in individual cells. Images were acquired for each fluorescence channel by specific filters. Images and data pertaining to the intensity and texture of fluorescence within individual cells, as well as the average fluorescence of the cell population within the well was stored in the Microsoft SQL database and analyzed by ArrayScan II Data Acquisition and Data Viewer version 3.0 software (Cellomics Technology).

Bioluminescent assays for caspase activity

A dose-dependent study of caspase-7, caspase-8, and caspase-9 activity was carried out in triplicate using Caspase-Glo® assay kits (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) on a white 96-well microplate. A total of 1×104 cells per well was seeded and incubated with different concentrations of koenimbin for 24 hours. Caspase activity was investigated as previously described.45,46 Briefly, 100 μL of Caspase-Glo reagent was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The presence of active caspases from apoptotic cells cleaved the aminoluciferin-labeled synthetic tetrapeptide, thus releasing the substrate for the luciferase enzyme. Caspase activity was measured using an Infinite 200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan).

NF-κB translocation

Briefly, 1.0×104 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37ºC with 5% CO2. The cells were pretreated with different concentrations of the compound for 3 hours and then stimulated with 1 ng/mL of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α for 30 minutes. The medium was removed and the cells were fixed and stained with a nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plate was examined on an ArrayScan high-content screening reader. Calculation of the cytoplasmic and nuclear NF-κB intensity ratio was carried out using Cytoplasm to Nucleus Translocation BioApplication software. The average intensity of 200 cells per well was quantified, and the ratios were then compared with TNF-α-stimulated, treated, and untreated cells.47

Human apoptosis proteome profiler array

To investigate the pathways by which koenimbin induces apoptosis, we performed a determination of apoptosis-related proteins using a proteome profiler array (human apoptosis antibody array kit, Raybiotech, Norcross, GA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, the cells were treated with koenimbin 9 μg/mL for 24 hours, in which 300 μg of protein extract from each sample were incubated with the antibody array membrane for 12 hours. The membrane was quantified using a Biospectrum AC ChemiHR 40 system (UVP, Upland, CA, USA) and the membrane image file was analyzed using ImageJ analysis software.

Protein expression of apoptotic markers and the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway

MCF7 cells were treated in T-25 flasks with various concentrations of koenimbin. The protein extracts were lysed with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and 40 μg of protein extract was loaded onto a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system, then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane were then blocked using 5% non-fat milk in TBS-Tween buffer 7 (0.12 M Tris-base, 1.5 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 40 minutes at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with the appropriate primary antibody for 12 hours at 4°C and then washed with Tris-Buffered Saline and Tween 20 (TBST) buffer. The primary antibodies for detection of apoptotic markers,16,17 ie, β-actin (1:5,000), Bcl2 (1:1,000), Bax (1:1,000), and heat shock protein (HSP) 70 (1:1,000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The phospho β-catenin T41+S45 (1:1,000), phospho β-catenin S33+S37 (1:500), GSK3β (1:5,000), phospho GSK3β (1:500), and cyclin D1 (1:5,000) for detection of the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The membranes were then incubated for one hour at room temperature with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (i-DNA, Ocean, NJ, USA) at a ratio of 1:5,000 and then washed twice with TBST for 10 minutes on an orbital shaker. The blots were then developed using BCIP®/NBT solution (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for a period of 5–30 minutes to detect the target protein band as a precipitated dark-blue color.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions were checked. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) software. Statistical significance was defined at P<0.05.

Results

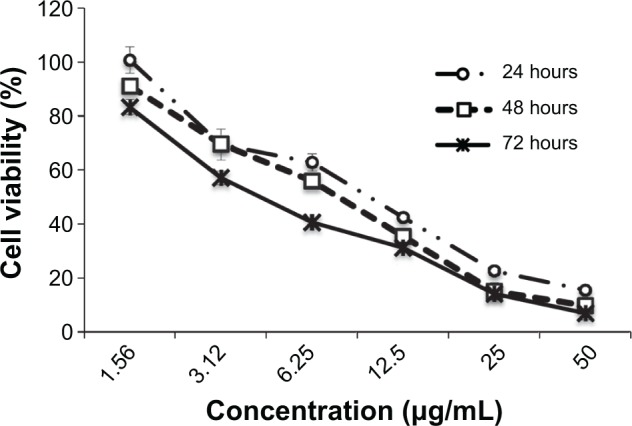

MTT cell viability assay

The effect of koenimbin on MCF7 and MCF-10A cells was evaluated using MTT assays in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1). IC50 values obtained for the MCF7 cells after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment with koenimbin were 9.42±1.05 μg/mL, 7.26±0.38 μg/mL, and 4.89±0.47 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1.

IC50 concentration of koenimbin

| Cell line | IC50 (μg/mL)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | 48 hours | 72 hours | |

| MCF7 | 9.42±1.05 | 7.26±0.38 | 4.89±0.47 |

| MCF-10A | 31±0.78 | 27±1.02 | 21±0.35 |

Note: Results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Growth curve for koenimbin-treated MCF7 cells at 24, 48, and 72 hours.

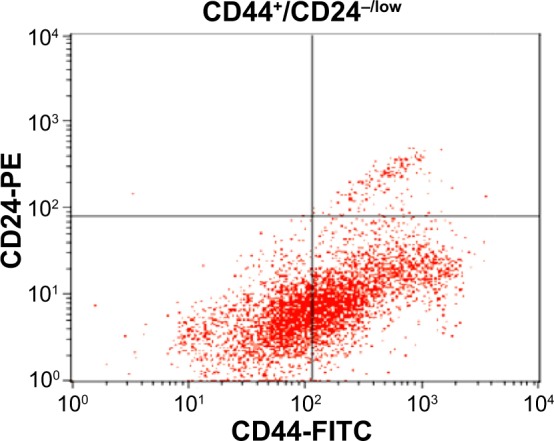

CD markers in breast CSCs

In this research, breast CSCs (CD44+/CD24−/low) were first isolated from MCF7 cells by sorting based on cell surface CD44+/CD24−/low marker expression (Figure 2). They were then cultured in mammosphere forming conditions. Breast CSCs from MCF7 were identified by expression of the cell surface marker CD44 and no or weak expression of CD24.

Figure 2.

MCF7 cancer stem cells were identified by expression of CD44+ and low expression of CD24−/low in quadrant analysis (CD44+/CD24−/low). Each experiment was performed three times (n=3).

Abbreviations: FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin.

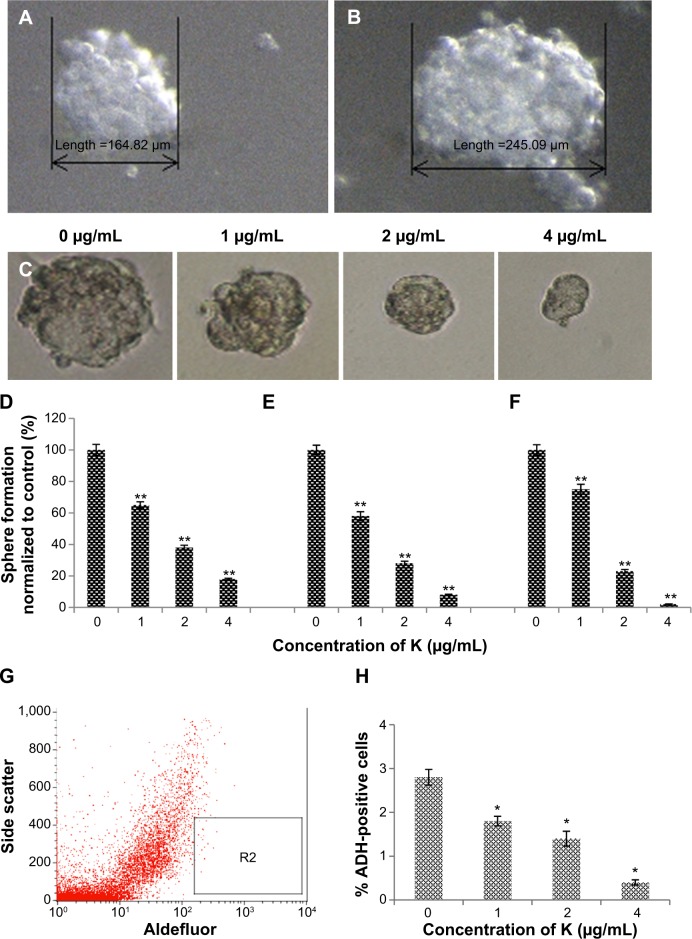

Inhibitory effect of koenimbin on mammosphere formation

Mammosphere cultures were carried out in serum-free medium. The mammospheres were photographed and the numbers of mammospheres were counted under a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S microscope. Photographs were acquired with MetaMorph 7.6.0.0 (Figure 3A and B). It has been shown that mammary stem/progenitor cells are enriched in non-adherent spherical clusters of cells, termed mammospheres.34 Hence, we exposed MCF7 CSC spheres to various concentrations of koenimbin to assess whether koenimbin could suppress the formation of mammospheres in vitro. According to our results, koenimbin inhibited non-adherent spherical clusters of breast CSCs in vitro, such that these cells were not capable of yielding secondary spheres and differentiating along multiple lineages. As shown in Figure 3C–F, koenimbin suppressed the formation of spheres, with the number of spheres declining significantly (P<0.01) with increasing concentrations of koenimbin.

Figure 3.

Mammosphere formation and Aldefluor™ assay of MCF7 cancer stem cells.

Notes: Size of mammospheres containing MCF7 cancer stem cells on day 5 (A) and day 7 (B). MCF7 cancer stem cells were cultured in mammosphere-forming conditions, and were incubated with koenimbin (0, 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL) for 7 days (magnification ×100) (C). Koenimbin reduced the size of the primary mammospheres. In the absence of drug, the second and third passages derived from koenimbin-treated primary mammospheres yielded smaller numbers of spheres in comparison with the control. The size of the mammospheres was estimated using V = (4/3)πR3. Koenimbin inhibits mammosphere formation and prevents self-renewal of (D) primary, (E) secondary, and (F) tertiary mammosphere-forming units. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). **P<0.01 versus control. (G) Aldefluor assay of MCF7 cancer stem cells. Single cells obtained from cell cultures were incubated for 50 minutes at 37°C in Aldefluor assay buffer containing an ADH substrate, BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde (1 μmol/L per 1×106 cells). A cell population (R2) with high ADH activity was reported to enrich mammary stem/progenitor cells. (H) Inhibitory effect of koenimbin on ADH-positive cell populations. MCF7 cancer stem cells were treated with koenimbin 1, 2, or 4 μg/mL for 4 days and subjected to Aldefluor assay and flow cytometry analysis. Koenimbin decreased the percentage of ADH-positive cells. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 versus control; **P<0.01 versus control.

Abbreviations: ADH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; K, koenimbin.

Inhibitory effect of koenimbin in an ADH-positive cell population

MCF7 breast cancer cell populations with high ADH activity, indicating enriched breast stem/progenitor cells and promoting self-renewal of MCF7 CSCs, were assessed using the Aldefluor assay (Figure 3G). As shown in Figure 3H, koenimbin concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL significantly diminished the ADH-positive population of MCF7 CSCs by over 25%, 50%, and 80%, respectively. This finding indicates that koenimbin reduced the breast MCF7 CSC population in vitro. An interesting observation is that koenimbin was able to inhibit MCF7 CSCs at concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 μg/mL, which hardly affected the bulk of the population of MCF-10A cells, implying that koenimbin probably has the capacity to preferentially target MCF7 CSCs.

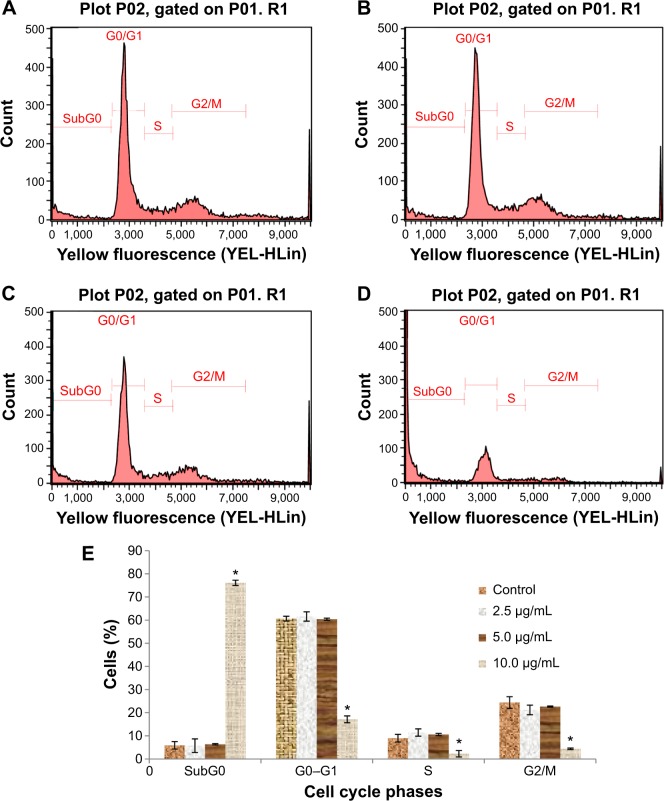

Cell cycle analysis

According to the cell cycle analysis, treatment with koenimbin 10 μg/mL was able to induce significant (P<0.05) alteration of all cell cycle phases (Table 2). A dramatic increase in the sub-G0 phase, which indicates DNA fragmentation, and reduction of the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases was observed in cells treated with koenimbin 10 μg/mL. However, no significant difference was observed in cells treated with koenimbin 2.5 or 5 μg/mL (Figure 4A–E). Therefore, the cell cycle analysis indicated significant cytotoxicity and cell inhibitory effects of koenimbin in MCF7 breast cancer cells.

Table 2.

Effect of koenimbin on cell cycle phases of MCF7

| Concentration | Sub-G0 | G0–G1 | S | G2/M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.92±1.62 | 60.65±2.94 | 9.00±0.30 | 24.43±1.15 |

| 2.5 | 5.75±1.06 | 61.60±2.02 | 11.45±0.46 | 21.20±1.47 |

| 5 | 6.38±1.65 | 60.40±1.58 | 10.57±0.49 | 22.65±1.38 |

| 10 | 76.12±2.49* | 17.17±2.08* | 2.29±0.24* | 4.42±0.32* |

Notes: Cells were exposed to koenimbin at various concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, or 10 μg/mL) and incubated for 24 hours. The table summarizes the percentages of cells in each phase of the cell cycle after treatment with koenimbin. Data in the same vertical column but different rows refer to the same phase of the cell cycle and different koenimbin concentrations.

Indicates a significant difference (P<0.05). Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

Figure 4.

Cell cycle histograms from analyses of MCF7 cells treated with 0 (A), 2.5 (B), 5 (C), and 10 μg/mL (D) of koenimbin for 12 hours. (E) Summary of cell cycle progression for control and koenimbin-treated MCF7 cells.

Notes: Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 versus control.

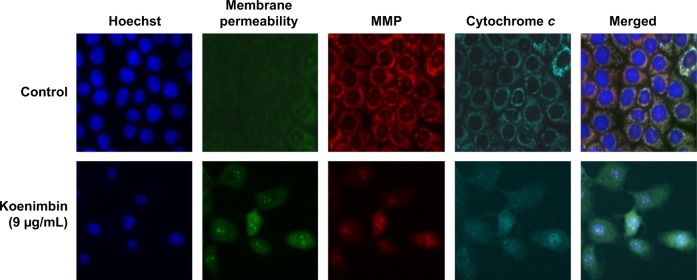

Effects of koenimbin on membrane permeability, MMP, and cytochrome c release

As the main source of cellular reactive oxygen species and adenosine triphosphate, the mitochondria play an important regulatory role in controlling the survival and death of cells. We used MMP fluorescent probes to examine the function of mitochondria in treated and untreated MCF7 cells. As shown in Figure 5, the untreated cells were strongly stained with MMP dye in comparison with cells treated with koenimbin 9 μg/mL for 24 hours. The reduction in MMP fluorescence intensity indicated that MMP was destroyed in the treated cells. A significant increase in cell membrane permeability was also observed in the treated cells after 24 hours of treatment with koenimbin. Twenty-four hours of exposure to koenimbin also resulted in an increase in cytochrome c in the cytosol when compared with the control.

Figure 5.

Representative images of MCF7 cells treated with medium alone and koenimbin 9 μg/mL, and stained with Hoechst for nuclear, cytochrome c, membrane permeability, and MMP dyes, and cytochrome c dye. The images from each row are obtained from the same field of the same treatment sample (magnification 20×).

Abbreviation: MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential.

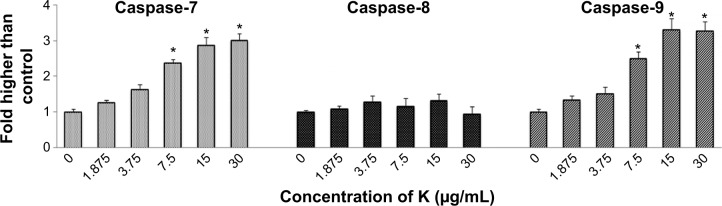

Bioluminescent assays for caspase activity

Excessive production of reactive oxygen species from the mitochondria and collapse of MMP may activate downstream caspase molecules, leading to apoptotic cell death. To examine this, we measured the bioluminescent intensities relating to caspase activity in the MCF7 cells treated with different concentrations of koenimbin for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 6, a significant dose-dependent increase in caspase-7 and caspase-9 activity was detected in the treated cells, while no marked change in caspase-8 activity was observed between treated and untreated cells. Hence, apoptosis induced by koenimbin in MCF7 cells is mediated via the intrinsic mitochondrial caspase-9 pathway and not the extrinsic death receptor-linked caspase-8 pathway.

Figure 6.

Relative bioluminescence expression of caspase-7, caspase-8, and caspase-9 in MCF7 cells treated with koenimbin at various concentrations.

Notes: The results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Statistical significance is expressed as *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: K, koenimbin.

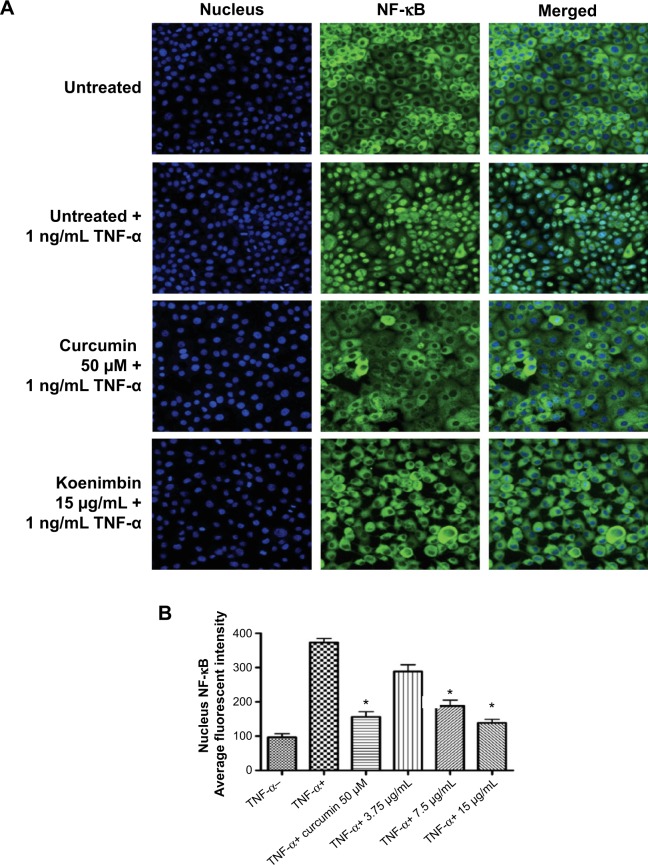

Translocation of NF-κB

NF-κB is a transcription factor critical for cytokine gene expression. Activation of NF-κB in response to inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, mediates nuclear migration to enable DNA-binding activity and facilitate target gene expression. As seen in Figure 7A, koenimbin suppressed the translocation of cytoplasmic NF-κB to the nucleus. The significant decline in nuclear NF-κB translocation in TNF-α-stimulated MCF7 cells treated with koenimbin as shown by the statistical analysis confirms the inhibitory activity of the compound against nuclear translocation of NF-κB (Figure 7A and B).

Figure 7.

(A) Photographs of intracellular targets in stained MCF7 cells treated with koenimbin for 3 hours and then stimulated for 30 minutes with TNF-α 1 ng/mL (NF-κB activation). (B) Representative bar chart indicating a significant decline in average fluorescent intensity of nuclei NF-κB, confirming that koenimbin inhibited TNF-α-induced translocation of NF-κB from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

Notes: Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 versus control.

Abbreviations: NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

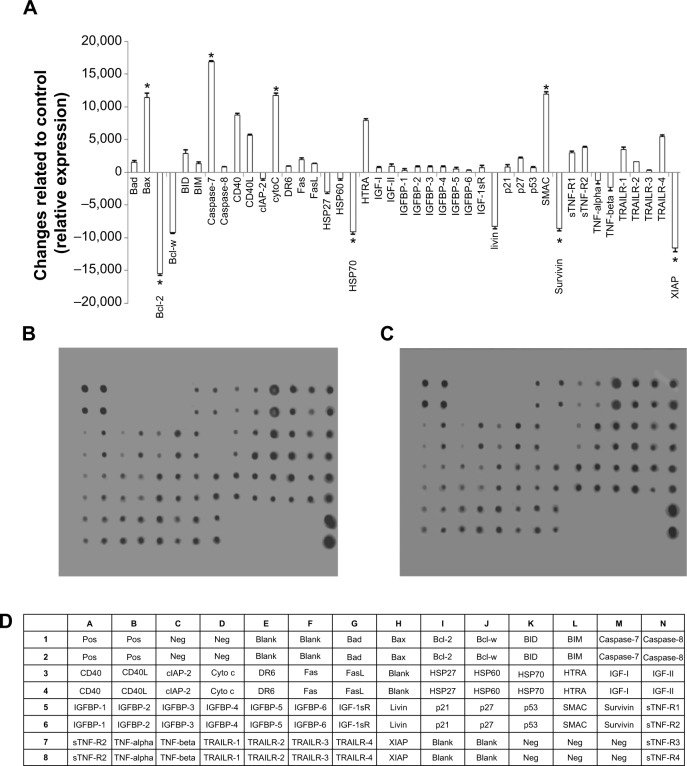

Effect of koenimbin on apoptotic markers

After exposure of MCF7 cells to koenimbin for 24 hours, the cells were lysed and apoptotic markers were examined using a human apoptosis protein array. In Figure 8A–D, the images represent the changes of apoptotic markers in treated and untreated cells. The most important markers involved in the apoptosis signaling pathway, such as Bax, Bcl2, caspase-7, and caspase-8, were induced, along with cytochrome c. HSP70, a significant chaperone involved in apoptosis, was also downregulated in this in vitro model.

Figure 8.

Quantitative analysis of the human apoptosis proteome profiler array in koenimbin-induced MCF7 cells. MCF7 cells were lysed and protein arrays were performed. Cells were treated with koenimbin 9 μg/mL for 24 hours and total cell protein was extracted. Equal amounts (300 μg) of protein from each control and treated sample were used for the assay. Quantitative analysis of the arrays showed differences in the apoptotic markers.

Notes: The graph shows the difference between treated cells as well as untreated control cells (A). Representative images of the apoptotic protein array are shown for the control (B), treated (C), and the exact protein name of each dot in the array (D). The results are shown as the mean ± standard deviation for three independent experiments. *Indicates a significant difference from control (P<0.05).

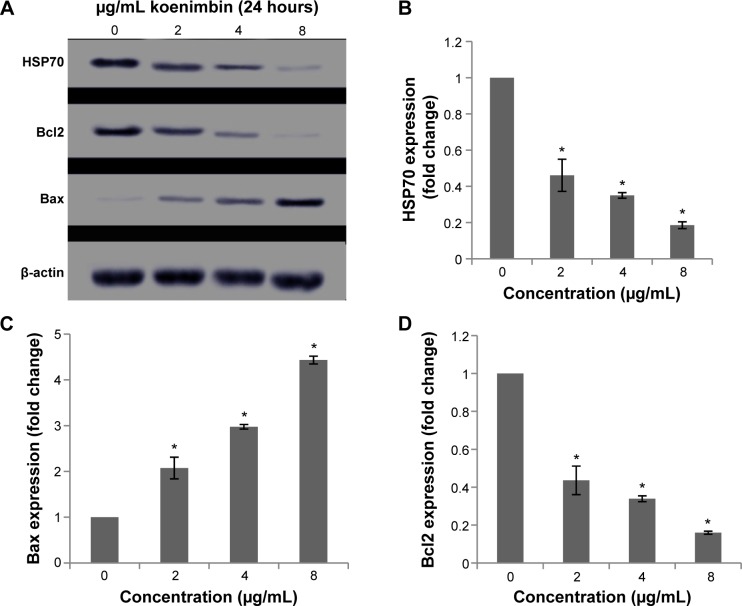

Protein expression of apoptotic markers and the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway

Although many proteins associated with apoptosis were observed to be upregulated or downregulated in the protein array, proteins such as Bax and HSP70 were significantly induced.

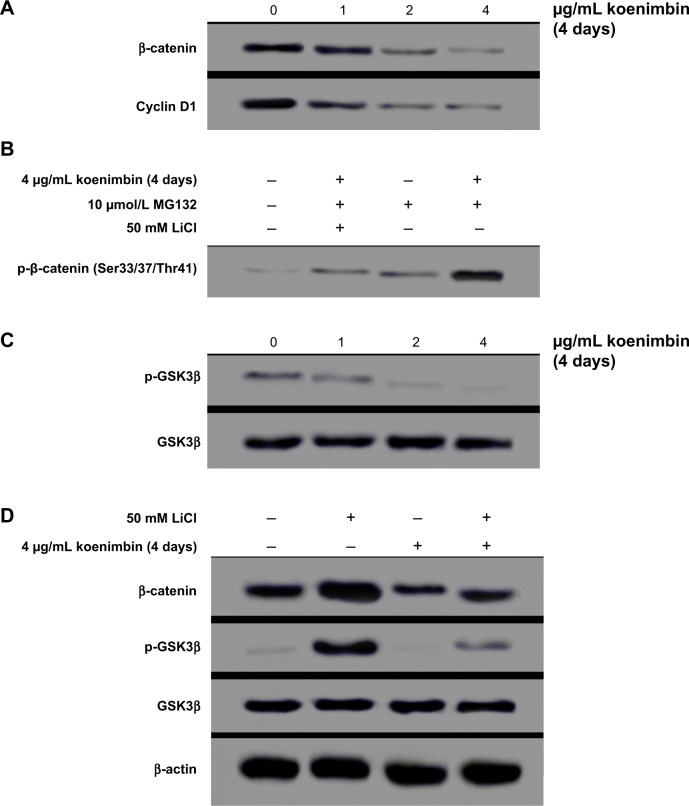

The role of the mitochondria in modulation of apoptotic markers at the protein level was examined, and expression of Bax, a proapoptotic protein, and Bcl2, an antiapoptotic protein, were increased and decreased, respectively, in koenimbin-induced MCF7 cells. Further, protein expression of HSP70 was downregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 9). Additionally, treatment of MCF7 cells with koenimbin decreased expression levels of β-catenin and cyclin D1 (Figure 10A), while the expression level of p-β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) increased (Figure 10B). In this study, MG132 was used to suppress proteasome functional activity and determine the status of p-β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) in response to koenimbin. Here, our result indicated reduced expression of p-GSK3β (Ser9) with increasing concentrations of koenimbin (Figure 10C). The koenimbin-induced β-catenin phosphorylation is reversed in the presence of LiCl, a GSK3β inhibitor (Figure 10D). As shown in Figure 10D, koenimbin has the ability to decrease LiCl-induced GSK3β phosphorylation and accumulation of β-catenin.

Figure 9.

Western blot analysis of koenimbin in selected apoptotic signaling markers.

Notes: The blot densities are expressed as fold of control (A). The HSP70 protein level was also downregulated, showing significant changes on treatment with koenimbin 4 and 8 μg/mL (B). The Bax (C) and Bcl2 (D) apoptotic markers were significantly elevated and reduced respectively, in a dose-dependent manner. The data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 versus control.

Abbreviation: HSP, heat shock protein.

Figure 10.

Western blot analysis of the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway in MCF7 cells treated with koenimbin. Koenimbin downregulated this pathway.

Notes: Koenimbin decreased protein expression levels of β-catenin and cyclin D1 in MCF7 cells (A). Koenimbin increased the phospho-β-catenin Ser33/Ser37/Thr41, whereas LiCl suppressed phosphorylation through inactivation of GSK3β (B). Koenimbin decreased the expression level of p-GSK3β, while the protein expression of total GSK3β was unchanged (C). Koenimbin decreased β-catenin and LiCl-induced GSK3β phosphorylation, while LiCl elevated the protein expression level of β-catenin through GSK3β phosphorylation (D). Each experiment was performed three times (n=3).

Abbreviation: GSK, glycogen synthase kinase.

Discussion

Apoptosis is associated with many biochemical changes in cells, including nuclear fragmentation, change in the MMP, and regulation of caspases.48 The present study is the first report on the in vitro effects of koenimbin, a natural compound derived from the plant M. koenigii (L) Spreng, against MCF7 cells and derived MCF7 stem cells/progenitors. Interestingly, koenimbin inhibited the growth of MCF7 cells and derived MCF7 stem cells/progenitors, while non-invasive MCF-10A cells were more resistant to koenimbin-mediated antiproliferative activity than the MCF7 cells and derived MCF7 CSCs. However, several chemotherapeutic drugs, including vincristine, vinblastine, and paclitaxel are derived from plants49 and affect normal cells.50

The cell morphology, cell membrane permeability, and nuclei area were significantly diminished by treatment with koenimbin. Due to their role in direct activation of the apoptotic program in cells, the mitochondria have been described as key players in the apoptotic process.51 Therefore, the complex role of the mitochondria in apoptosis of MCF7 cells was investigated by detection of changes in MMP, as it is assumed that its disruption is the onset of formation of the mitochondrial membrane transition pore.52 The high content analysis conducted in this research indicated that koenimbin may target the mitochondria, causing loss of MMP, and subsequently, leads to apoptotic changes. Apoptotic proteins, such as cytochrome c, are relocalized due to this reduction in MMP and permeability transition pore complex.53

The activation of caspase is a key regulatory factor in apoptosis.54 In the intrinsic pathway, release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytosol is a fundamental feature of apoptosome formation and downstream caspase-9 activation, leading to activation of effector caspases such as caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7.55–57 There is evidence that members of the Bcl2 protein family are key mediators of cytochrome c release in the context of apoptotic stimuli.58,59 Moreover, release of cytochrome c to the cytosol, loss of MMP, and induction of mitochondrial permeability transition events, occur as a consequence of movement of Bax into the mitochondria.60 The release of cytochrome c and the enzyme activity of caspase-7 and caspase-9 triggered by koenimbin clearly demonstrated that the apoptosis was via the intrinsic pathway. However, the extrinsic pathway of caspase activation involves signal transduction through cell death receptors such as Fas and TNF-α, resulting in caspase-8 activation, which in turn activates downstream effector caspases, such as caspase-3 and caspase-7.45,61 Caspase-8 activation is closely involved with apoptosis signaling via the extrinsic pathway,57 and may be interlinked with the mitochondrial pathway via cleavage of Bid to tBid.62 In agreement with previous studies,19,45,63 we observed significant translocation of cytoplasmic NF-κB to the nuclei, activated by TNF-α. Our study revealed the effectiveness of koenimbin on TNF-α-related apoptosis-inducing ligands in MCF7 cells by interfering with the NF-κB-induced antiapoptotic signaling pathway, release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol, sequential activation of caspase-7 and caspase-9, and involvement of the up-regulating Bax and down-regulating Bcl-2 protein expressions.

According to CSC theory, a variety of cancers are driven and preserved by a small proportion of CSCs, thus leading to new approaches involving target CSCs for the treatment and prevention of cancer.24,64 Previous studies have shown that CSCs can cause tumor resistance, relapse, and recurrence.65,66 A novel approach is required to specifically target the CSC population, due to the lack of efficacy of current chemotherapies with regard to cancer cells and CSCs. Thus, therapies directed against both cancer cells and CSCs may be advantageous in the treatment of cancer.24,67,68 Several dietary compounds, including curcumin37,38 and sulforaphane,69 have been shown to have chemopreventive effects against CSCs. Here, the anticancer activity of koenimbin against breast CSCs was investigated in vitro to identify the chemopreventive activity of koenimbin and the implications of CSC theory. However, we did not undertake a clinical trial of koenimbin in breast cancer patients in the present study.

Techniques such as mammosphere culture, cell surface markers, and ADH assays have been reported as part of the isolation and characterization of breast CSCs in vitro. Isolation and expansion of mammary stem/progenitor cells70 using mammosphere cultures are based on the failure of differentiated cells to survive and grow in serum-free suspension, compared to stem/progenitor cells.71 Consistent with previous studies72 showing that mammospheres are composed primarily of CSCs, our observations indicate that koenimbin significantly suppressed formation of breast stem cell mammospheres, suggesting that koenimbin may target breast CSCs from MCF7 cells. Another method for distinguishing between mammary stem/progenitor cells and differentiated cancer cells involves use of cell markers, eg, CD44+/CD24−/low and ADH positivity.26,71,73 It has been shown that as few as 500 ADH-positive cells can generate a breast tumor within 40 days, while 50,000 ADH-negative cells are unable to form tumors.73 ADH-positive cells and the CD44+/CD24−/low marker were identified as the highest tumorigenic capacity, generating tumors from as few as 20 cells.73 In contrast, ADH-positive cells without the CD44+/CD24−/low marker were able to produce tumors from 1,500 cells, whereas ADH-negative cells and 50,000 CD44+/CD24−/low cells could not.73 Therefore, Aldefluor assays were used to evaluate targeting of breast CSCs by koenimbin. According to our results, koenimbin could selectively inhibit ADH-positive cancer cells in vitro. Interestingly, the concentrations of koenimbin that effectively inhibited breast CSCs in both the non-adherent mammosphere formation assay and Aldefluor assay indicate the significant potential of koenimbin to target breast CSCs.

Curcumin has been shown to interfere with the Wnt and Notch self-renewal pathways in colonic and pancreatic cancer cells, respectively.37,38 Quercetin and green tea epigallocatechin gallate were described to regulate key mediators of the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways in human colon cancer cells.39 Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathways have emerged as having hallmark roles in chronic inflammation, immunity, development, and tumorigenesis. These two pathways independently initiate oncogenesis, and crossregulation between these two pathways influences development and carcinogenesis.74 It has been reported that β-catenin is downregulated in HeLa and HepG2 cells.75 Consistent with these studies, we showed that koenimbin was able to downregulate the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway and cyclin D1, in which the koenimbin-induced β-catenin at Ser33/37/Thr41 and degradation of the proteasome is possibly via GSK3β activation in breast cancer cells, as one of the possible mechanisms to target the MCF7 CSCs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, koenimbin is able to trigger apoptosis in breast cancer cells in vitro. Treatment of human MCF7 breast cancer cells with koenimbin resulted in apoptosis, with cell death-transducing signals regulating MMP by downregulating Bcl2 and upregulating Bax, thereby triggering release of mitochondrial cytochrome c to the cytosol. Upon entering the cytosol, cytochrome c activates caspase-9, then triggers activation of caspase-7, and consequently cleaves specific substrates leading to apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway. Additionally, koenimbin is able to target MCF7 CSCs as determined by the mammosphere formation assay and Aldefluor assay. Our study also identified downregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway as one of the possible mechanisms of action of koenimbin. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the therapeutic potential of koenimbin in the chemoprevention of breast cancer, and provides a strong rationale for clinical evaluation of this compound in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their utmost gratitude and appreciation to University of Malaya Research Grant (RG084-13BIO), IPPP grants (PG082-2013B and PG116-2014A), and BKP grant (BK020-2012) for providing financial support to conduct this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Nakamura S, Nakashima S, Oda Y, et al. Alkaloids from Sri Lankan curry-leaf (Murraya koenigii) display melanogenesis inhibitory activity: structures of karapinchamines A and B. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(5):1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Q, Tian J, Yang J, et al. Bioactive carbazole alkaloids from Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. Fitoterapia. 2013;87:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arulselvan P, Subramanian S. Effect of Murraya koenigii leaf extract on carbohydrate metabolism studied in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Int J Biol Chem. 2007;1(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinuthan M, Kumar VG, Narayanaswamy N, Veena T. Lipid lowering effect of aqueous leaves extract of Murraya koenigii (curry leaf) on alloxan-induced male diabetic rats. Pharmacogn Mag. 2007;3(10):112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arulselvan P, Subramanian SP. Beneficial effects of Murraya koenigii leaves on antioxidant defense system and ultra structural changes of pancreatic β-cells in experimental diabetes in rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;165(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao L, Ramalakshmi K, Borse B, Raghavan B. Antioxidant and radical-scavenging carbazole alkaloids from the oleoresin of curry leaf (Murraya koenigii Spreng.) Food Chem. 2007;100(2):742–747. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito C, Itoigawa M, Nakao K, et al. Induction of apoptosis by carbazole alkaloids isolated from Murraya koenigii. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(5):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdall SE, Hanby AM, Lansdown M, Speirs V. Breast cancer cell lines: friend or foe? Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5(2):89–95. doi: 10.1186/bcr577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamalidehghan B, Houshmand M, Kamalidehghan F, et al. Establishment and characterization of two human breast carcinoma cell lines by spontaneous immortalization: discordance between estrogen, progesterone and HER2/neu receptors of breast carcinoma tissues with derived cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2012;12(1):43. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmakar S, Banik NL, Ray SK. Molecular mechanism of inositol hexaphosphate-mediated apoptosis in human malignant glioblastoma T98G cells. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(12):2094–2102. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lev-Ari S, Vexler A, Starr A, et al. Curcumin augments gemcitabine cytotoxic effect on pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(6):411–418. doi: 10.1080/07357900701359577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichikawa H, Nakamura Y, Kashiwada Y, Aggarwal BB. Anticancer drugs designed by mother nature: ancient drugs but modern targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(33):3400–3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen JG, LeBlanc GA. Reversal of multidrug resistance in vivo by dietary administration of the phytochemical indole-3-carbinol. Cancer Res. 1996;56(3):574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paydar M, Kamalidehghan B, Wong YL, Wong WF, Looi CY, Mustafa MR. Evaluation of cytotoxic and chemotherapeutic properties of boldine in breast cancer using in vitro and in vivo models. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:719. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S58178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salim LZA, Mohan S, Othman R, et al. Thymoquinone induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in vitro. Molecules. 2013;18(9):11219–11240. doi: 10.3390/molecules180911219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muhammad Nadzri N, Abdul AB, Sukari MA, et al. Inclusion complex of zerumbone with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin induces apoptosis in liver hepatocellular HepG2 cells via caspase 8/bid cleavage switch and modulating Bcl2/Bax ratio. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:810632. doi: 10.1155/2013/810632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isa NM, Abdul AB, Abdelwahab SI, et al. Boesenbergin A, a chalcone from Boesenbergia rotunda induces apoptosis via mitochondrial dysregulation and cytochrome c release in A549 cells in vitro: involvement of HSP70 and Bcl2/Bax signalling pathways. J Funct Foods. 2013;5(1):87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbab IA, Abdul AB, Sukari MA, et al. Dentatin isolated from Clausena excavata induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells through the intrinsic pathway with involvement of NF-κB signalling and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest: a bioassay-guided approach. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145(1):343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibrahim MY, Hashim MN, Mohan S, et al. α-Mangostin from Cratoxylum arborescensdemonstrates apoptogenesis in MCF-7 with regulation of NF-κB and Hsp70 protein modulation in vitro, and tumor reduction in vivo. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:1629–1647. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S66105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal BB, Sethi G, Baladandayuthapani V, Krishnan S, Shishodia S. Targeting cell signaling pathways for drug discovery: an old lock needs a new key. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102(3):580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Dontu G, Wicha MS. Mammary stem cells, self-renewal pathways, and carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(3):86–95. doi: 10.1186/bcr1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. Regulation of mammary stem/progenitor cells by PTEN/Akt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(6):e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, Dontu G, Mantle ID, et al. Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6063–6071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367(6464):645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki BT, Hurt EM, Mistree T, Farrar WL. Targeting cancer stem cells with phytochemicals. Mol Interv. 2008;8(4):174–184. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, et al. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2006;445(7123):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrawala L, Calhoun T, Schneider-Broussard R, et al. Highly purified CD44+; prostate cancer cells from xenograft human tumors are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2006;25(12):1696–1708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allan AL, Vantyghem SA, Tuck AB, Chambers AF. Tumor dormancy and cancer stem cells: implications for the biology and treatment of breast cancer metastasis. Breast Dis. 2007;26(1):87–98. doi: 10.3233/bd-2007-26108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dontu G, Jackson KW, McNicholas E, Kawamura MJ, Abdallah WM, Wicha MS. Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):R605–R615. doi: 10.1186/bcr920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafee N, Smith CR, Wei S, et al. Cancer stem cells contribute to cisplatin resistance in Brca1/p53-mediated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3243–3250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hambardzumyan D, Squartro M, Holland EC. Radiation resistance and stem-like cells in brain tumors. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(6):454–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Notch-1 downregulation by curcumin is associated with the inhibition of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer. 2006;106(11):2503–2513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaiswal AS, Marlow BP, Gupta N, Narayan S. Beta-catenin-mediated transactivation and cell-cell adhesion pathways are important in curcumin (diferuylmethane)-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21(55):8414–8427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pahlke G, Ngiewih Y, Kern M, Jakobs S, Marko D, Eisenbrand G. Impact of quercetin and EGCG on key elements of the Wnt pathway in human colon carcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(19):7075–7082. doi: 10.1021/jf0612530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127(3):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, et al. Control of β-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell. 2002;108(6):837–847. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachibana Y, Kikuzaki H, Lajis NH, Nakatani N. Antioxidative activity of carbazoles from Murraya koenigii leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49(11):5589–5594. doi: 10.1021/jf010621r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gummadi VR, Rajagopalan S, Yeng LC, et al. Discovery of 7-azaindole based anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors: wild type and mutant (L1196M) active compounds with unique binding mode. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23(17):4911–4918. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponti D, Costa A, Zaffaroni N, et al. Isolation and in vitro propagation of tumorigenic breast cancer cells with stem/progenitor cell properties. Cancer Res. 2005;65(13):5506–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohan S, Abdelwahab SI, Kamalidehghan B, et al. Involvement of NF-κB and Bcl2/Bax signaling pathways in the apoptosis of MCF7 cells induced by a xanthone compound Pyranocycloartobiloxanthone A. Phytomedicine. 2012;19(11):1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng KB, Bustamam A, Sukari MA, et al. Induction of selective cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human T4-lymphoblastoid cell line (CEMss) by boesenbergin A isolated from Boesenbergia rotunda rhizomes involves mitochondrial pathway, activation of caspase 3 and G2/M phase cell cycle arrest. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arbab IA, Looi CY, Abdul AB, et al. Dentatin induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells via Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, survivin downregulation, caspase-9, -3/7 activation and NF-kB inhibition. Evid Based BMC Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:856029. doi: 10.1155/2012/856029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunter AM, LaCasse EC, Korneluk RG. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) as cancer targets. Apoptosis. 2007;12(9):1543–1568. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Preedy VR. Cancer: Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants. London, UK: Academic Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang C, Youle RJ. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zamzami N, Kroemer G. Apoptosis: mitochondrial membrane permeabilization–the (w) hole story? Curr Biol. 2003;13(2):R71–R73. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ajenjo N, Cañón E, Sánchez-Pérez I, et al. Subcellular localization determines the protective effects of activated ERK2 against distinct apoptogenic stimuli in myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(31):32813–32823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Ellerby LM, et al. Release of caspase-9 from mitochondria during neuronal apoptosis and cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(10):5752–5757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, et al. Mitochondrial release of caspase-2 and -9 during the apoptotic process. J Exp Med. 1999;189(2):381–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Z, Jo J, Jia J-M, et al. Caspase-3 activation via mitochondria is required for long-term depression and AMPA receptor internalization. Cell. 2010;141(5):859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green DR. At the gates of death. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(5):328–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275(5303):1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiang J, Chao DT, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX-induced cell death may not require interleukin 1β-converting enzyme-like proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(25):14559–14563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu Q, De Wang J, Xia HH, et al. Activation of the caspase-8/Bid and Bax pathways in aspirin-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(3):541–546. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ibrahim MY, Hashim NM, Mohan S, Abdulla MA, Abdelwahab SI, Kamalidehghan B, et al. Involvement of nF-κB and hsP70 signaling pathways in the apoptosis of MDa-MB-231 cells induced by a prenylated xanthone compound, α-mangostin, from Cratoxylum arborescens. Drug des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2193–2211. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S66574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 64.Kakarala M, Wicha MS. Implications of the cancer stem-cell hypothesis for breast cancer prevention and therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(17):2813–2820. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakariassen PØ, Immervoll H, Chekenya M. Cancer stem cells as mediators of treatment resistance in brain tumors: status and controversies. Neoplasia. 2007;9(11):882–892. doi: 10.1593/neo.07658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang C, Chua CL, Ang B. Insights into the cancer stem cell model of glioma tumorigenesis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36(5):352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lippman ME. High-dose chemotherapy plus autologous bone marrow transplantation for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(15):1119–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004133421508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams SD, Birch R, Einhorn LH, Irwin L, Greco FA, Loehrer PJ. Treatment of disseminated germ-cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(23):1435–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y, Zhang T, Korkaya H, et al. Sulforaphane, a dietary component of broccoli/broccoli sprouts, inhibits breast cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(9):2580–2590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS. Cancer stem cells in breast: current opinion and future challenges. Pathobiology. 2008;75(2):75–84. doi: 10.1159/000123845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grimshaw MJ, Cooper L, Papazisis K, et al. Mammosphere culture of metastatic breast cancer cells enriches for tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(3):R52. doi: 10.1186/bcr2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Du Q, Geller DA. Cross-regulation between Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathways. For Immunopathol Dis Therap. 2010;1(3):155–181. doi: 10.1615/ForumImmunDisTher.v1.i3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park SY, Kim GY, Bae S-J, Yoo YH, Choi YH. Induction of apoptosis by isothiocyanate sulforaphane in human cervical carcinoma HeLa and hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells through activation of caspase-3. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(1):181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]