Abstract

There have been significant advances in the understanding of the biology and treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) over the past few years. A number of molecularly targeted agents are in the clinic or in development for patients with advanced NSCLC (Table 1). We are beginning to understand the mechanisms of acquired resistance following exposure to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with oncogene addicted NSCLC. The advent of next generation sequencing has enabled to study comprehensively genomic alterations in lung cancer. Finally, early results from immune checkpoint inhibitors are very encouraging. This review summarizes recent advances in the area of cancer genomics, targeted therapies and immunotherapy.

Keywords: NSCLC, TARGETED THERAPIES, IMMUNOTHERAPY

1. MOLECULAR GENETICS OF HUMAN LUNG CANCER

Lung cancer has traditionally been classified by histologic subtype and immunohistochemical characteristics. However, this classification has been complicated by the recognition that several clinically actionable somatic genetic alterations can be identified in the distinct histologic subtype of lung cancer and that some of these alterations can be found in more than one histology. Through comprehensive genomic analysis it is known that all lung cancers carry high rates of somatic mutation, high levels of inter- and intra-chromosomal rearrangement and copy number alterations as compared to other tumor types.1 Exploitation of these genomic aberrations has become an attractive and efficacious treatment strategy and has underscored the need for multiplexed genetic testing as part of the routine care of patients with lung cancer. To stratify patients into clinically relevant subgroups, the combination of histomorphological, immunohistochemical and genetic analysis is now employed for routinely for patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer and is the standard of care in newly diagnosed adenocarcinoma in which Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) mutation and Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) rearrangement testing have been incorporated into standard treatment algorithms. Additionally many institutions are now routinely testing for alterations such as ROS, RET, BRAF, and HER2 which have shown initial promise in tailored cancer treatment.

1.1 Lung Adenocarcinoma

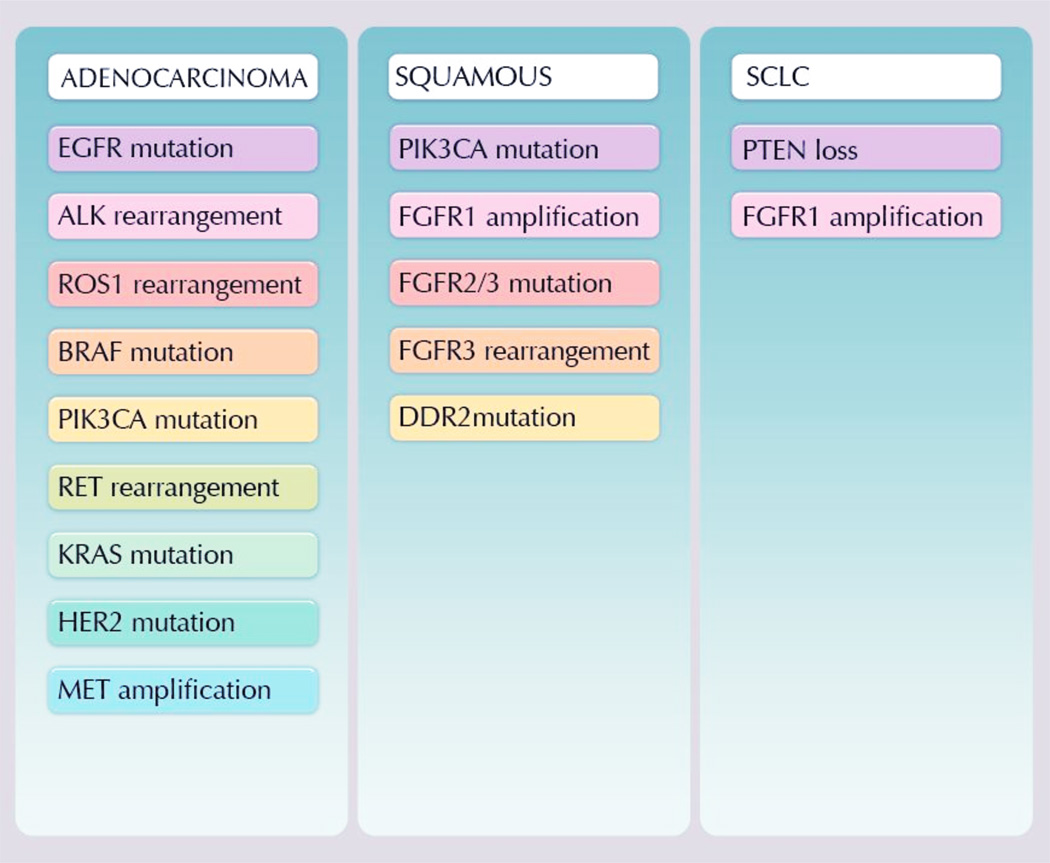

Lung adenocarcinoma is one of the best genetically characterized human epithelial malignancies and recent discoveries of targetable driver mutations have highlighted the impressive cadre of molecular alterations present in this disease. The identification of oncogenic activation of particular tyrosine kinases in some patients with advanced NSCLC most notably mutations in EGFR2–4 or rearrangements of the ALK gene5, has led to a paradigm shift and the development of specific molecular treatments for patients. These clinical successes have revolutionized the field and stimulated the investigation into additional, potential targetable, generation aberrations across all lung cancer histologies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Potential targetable oncogenes by histology subtype

For patients with lung adenocarcinoma the impact of genetic testing has led to changes in the standard diagnostic algorithms with recommendations from the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) and National comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) that newly diagnosed patients with advanced disease be tested for EGFR mutation and ALK fusion testing. Additionally many institutions are now routinely testing for alterations in genes such as ROS, RET, MET, BRAF, and HER2 which have shown initial promise in tailored cancer treatment.

The need to perform detailed molecular testing of lung cancers began with the correlation of EGFR mutations and sensitivity to gefitinib and erlotinib in lung adenocarcinoma, typically in patients with modest tobacco exposure EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are now the established first line therapy in patients with NSCLC known to have activating mutations in EGFR.6, 7 The majority of these tumors initially respond to EGFR TKIs, but subsequently develop resistance to therapy, with a median time to progression of 9 months.8 Recent work has demonstrated the value of additional molecular testing at the time of acquired resistance in EGFR TKI-responsive patients, as nearly half of patients with disease progression will carry a secondary EGFR mutation, such as T790M, which can now be successfully targeted with third generation EGFR TKIs such as AZD9291 and CO-1686.8, 9 Additional mechanisms of resistance to EGFR inhibitors have been defined in re-biopsy cohorts many of which are associated with a potential for response to other targeted agents or with response to other chemotherapies (small cell transformation).8

Receptor tyrosine kinase gene rearrangements, such as ALK, ROS and RET, are identified in 1–8% of lung adenocarcinomas.10 Patients’ whose tumors harbor ALK fusion, as well as ROS1 rearrangements demonstrate a response to crizotinib and other TKIs.11, 12 However, similar to their EGFR counterparts, these patients ultimately recur. This has led to molecular characterization of mechanisms of acquired resistance and the clinical use of ALK and ROS inhibitors with expanded mechanisms of action such as LDK378.

Interestingly, some of the most frequent genomic alterations in adenocarcinoma, such as mutations in TP53, KRAS, and STK11, have proven difficult to target and therapeutically exploit.13, 14 The mitogen activation pathway (MAPK) is often implicated in the development of lung adenocarcinoma however little success has been garnered therapeutically. The most common mechanism for MAPK activation is through substitutions mutations in 12th, 13th and 61st amino of KRAS. Activating KRAS mutations are observed in approximately 20 to 25% of lung adenocarcinomas in the United States and are generally associated with a history of smoking. The presence of a KRAS mutation appears to have at most a limited effect on overall survival (OS) in patients with early stage NSCLC, although some data have suggested that it was associated with inferior prognosis. Efforts to identify specific RAS inhibitors for KRAS-mutated lung cancer have proven challenging with the current focus of targeted therapeutics for patients with KRAS-mutated lung cancer is against downstream effectors of activated KRAS such as MEK1/MEK2, PI3K and AKT. Recent Phase II data examining combination use of selumetenib, an inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2 and docetaxel has been shown to have promising activity KRAS-mutant patient population.15 Additional work on downstream effectors in the KRAS mutant pathway is crucial and currently several clinical trials employing the inhibition of PI3KCA, MEK and PTEN are in progress.

1.2 Squamous Cell Lung Cancer

Genotyping alone has improved survival in patients who harbor a targetable mutation such as EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK fusions. However, there has been limited advancement in targeted approaches in squamous cell carcinoma until recently. Recent genomic profiling in squamous cell carcinoma has highlighted a number of new molecular targets including the FGFR family kinases. Fibroblast growth factor receptors are cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors that mediates cell survival and proliferation. Gene amplification of FGFR1 has been detected in 7 to 25% of squamous tumors, and extensive profiling has identified low-frequency activating mutations and copy number alterations in all of the FGF receptors.16–18 Small molecule inhibitors of FGFR1 are in clinical development and a case report of a NSCLC patient with tumor regression in response to the FGFR small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor BGJ398 has been presented.19 Additionally, a number of different mutations have been identified in FGFR2 and FGFR3, including a recurrent fusion of FGFR3 and TACC3, which provides much needed insight into the oncogenic pathways operating in SCC and makes a strong case for applying FGFR inhibitors in this disease.20–22 Targetable alterations in lung squamous cell carcinomas also include members of the PI3K pathway, DDR2 and potentially the NRF2/KEAP1/CUL3 antioxidant response pathway. In contrast to lung adenocarcinomas, there does not appear to be a substantial cohort of non-smokers with squamous cell lung cancer and the disease appears to be more genomically homogeneous.

1.3 Small Cell Lung Cancer

With the development of targeted agents, the treatment paradigm of NSCLC continues to evolve however the discovery of a clinically actionable mutation in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) remains elusive. SCLC remains an exceptionally aggressive malignancy with limited treatment options in the relapsed/refractory setting. SCLC has a high mutation rate, likely secondary to tobacco carcinogen exposure in this patient population. This high rate of mutation makes the identification of pathologically relevant driver mutations difficult. Genomic sequencing has confirmed a high prevalence of difficult to target TP53 and RB1 inactivation mutations. Next generation sequencing has been applied to the SCLC genome in hopes of identifying new therapeutic targets and recent work has showcased the identification of significantly mutated genes in SCLC cell lines. These aberrations include genetic alterations affecting histone modifying enzymes CREBPP, EP300, and LFF as well as PTEN mutations, FGFR1 and SOX2 amplification. Recent work on SOX2 demonstrates the prevalence of SOX2 amplification in SCLC cell lines with expression of SOX2 strongly correlated with increased gene copy number and clinical stage leading the authors to postulate if SOX2 is a genuine SCLC driver mutation.23, 24

2. EPIGENETIC THERAPY IN THE TREATMENT OF LUNG CANCER

The contributions of epigenetic dysregulation to carcinogenesis through aberrant DNA methylation and altered chromatin configuration continue to be expanded.25 The cancer epigenome contains a variety of tumor-specific alterations which define subgroups of disease, alter transcriptional patterns, and may reflect therapeutic sensitivities.26–28

Recent genomic sequencing efforts have further underscored the inextricable connections between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of carcinogenesis, including alternative mechanisms leading to loss of individual tumor suppressor gene function, as well as cooperation of defects affecting key signaling pathways. A signature example in lung cancer is the CDKN2A locus, encoding both the p16 tumor suppressor (a key regulator of cell-cycle progression from G1 to S-phase) as well as ARF (which can sequester MDM2, leading to stabilization of the tumor suppressor p53). Comprehensive genomic analysis of squamous cell lung cancers by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network has demonstrated CDKN2A loss of function in the large majority of cases, the most common mechanisms being homozygous deletion in 29%, site-specific promoter hypermethylation leading to gene silencing in 21%, and missense or truncating mutation in 18%.27

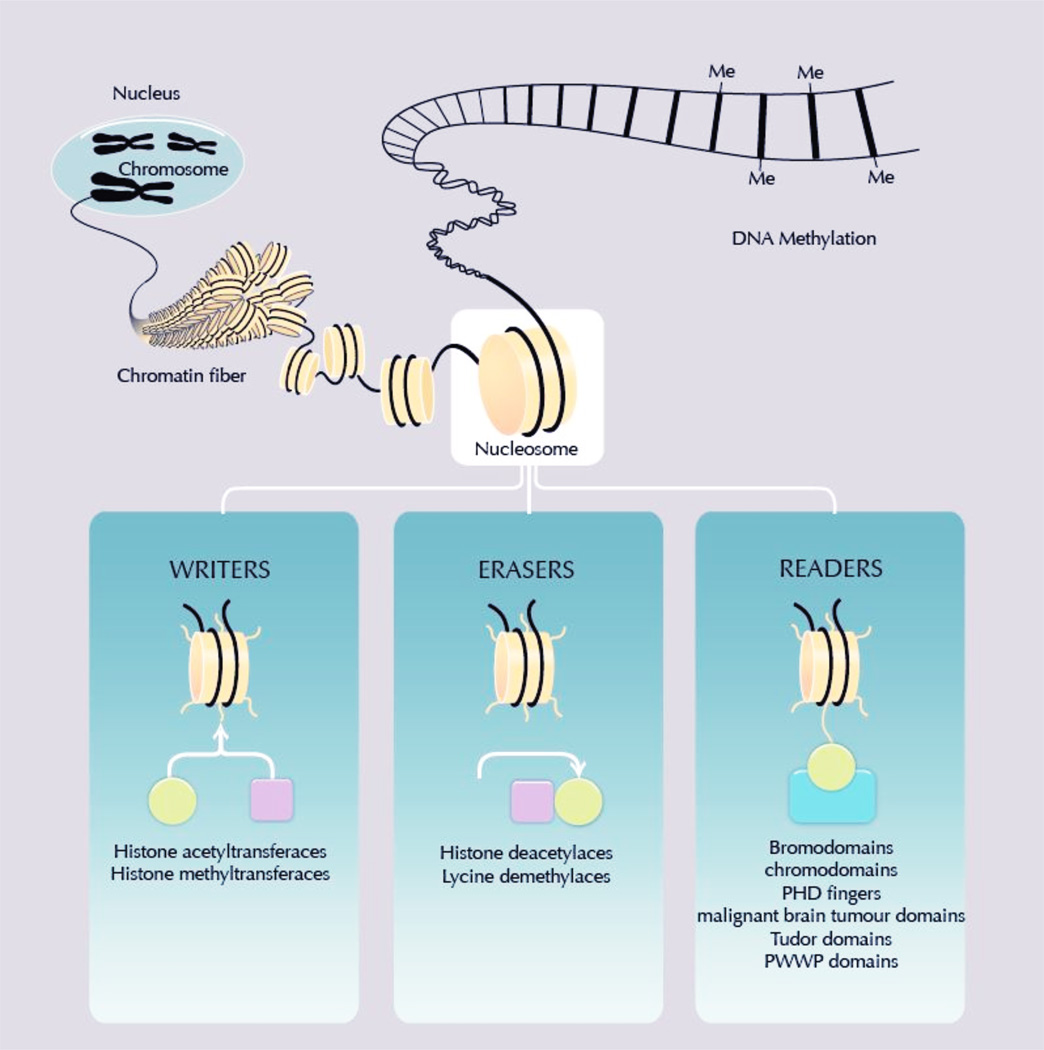

The TCGA has also demonstrated, across tumor types, high rates of genetic alterations in key epigenetic regulators. These include members of the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene family of histone methyltransferases, mutated in 20 and 18 percent of squamous and non-squamous lung cancers, respectively.29 Chromatin modifying enzymes which add and remove histone modifications, termed “writers” and “erasers”, affect the state of chromatin compaction of DNA making it more or less accessible for the transcription of genes which play various roles in a cancer cell’s transformation (Figure 2). Beyond the vast changes in DNA methylation which characterize cancer, these enzymes contribute to an altered landscape of transcriptional regulation not only in the hematologic malignancies for which epigenetic therapy has found early success, but also in a broad range of solid tumors including lung cancers.25, 29 Mutations of the isocitrate dehydrogenase genes, found across many tumor types, most notably gliomas and sarcomas but also including a small percentage of lung cancers, result in a CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) with therapeutic implications.29, 30 Multiple CIMP-like states have been described, and the molecular abnormalities responsible for these phenotypes are beginning to be defined; to date these include alterations in genes affecting the metabolism of methylated cytosines as well as mutations in DNA methyltransferases.30, 31

Figure 2.

Chromatin modifying enzymes

Historically, identification and demonstration of re-expression of individual tumor suppressor genes has provided the rationale for the clinical development of DNA hypomethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors in various hematologic malignancies.32 In fact, of course, hundreds of genes are affected by these therapies. Many of the described “hallmarks of cancer,” broad programs of normal cellular functions subverted during carcinogenesis, are altered by epigenetic reprogramming.33 Epigenetically directed therapies have the potential to concurrently affect multiple relevant pathways critical to cancer proliferation, survival, and metastatic capacity. Site-specific hypermethylation of promoters for genes controlling stem cell maturation has been implicated as a mechanism contributing to replicative immortality and clonogenic potential in cancer.34, 35 Promoter demethylation by DNA methyltransferase inhibitors such as azacitidine can markedly reduce replicative capacity in cancer cell ines, associated with reversal of a program of cancer-specific changes in methylation.36 Mutations in epigenetic regulators such as the polycomb-repressive complex protein BMI-1 and the histone methyltransferase EZH2 can enhance clonogenic potential of cancer cells.35 Additionally, genetic alterations of chromatin regulatory genes with established roles in proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis and senescence, and promotion of genomic instability, have been described.35

In addition to affecting key elements of carcinogenesis, epigenetic therapy may have a role in the treatment of acquired resistance to mutationally targeted therapy. For example, inhibition of the histone demethylase KDM5A has been shown to preferentially eliminate clonogenic survivors to EGFR tyrosine kinase therapy in EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines.37

While epigenetic therapy regimens employing DNA hypomethylating agents or histone deacetylase inhibitors have become standard-of-care therapies in myelodysplastic syndrome and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, these treatments have only begun to be clinically investigated in lung cancer or other solid tumors. Combinatorial epigenetic therapy consisting of the DNA hypomethylating agent azacitidine and the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat has been shown to result in rare objective responses in lung cancer.38 Data from this initial study suggest that combinatorial epigenetic therapy may prime lung cancers for improved responses to subsequent therapy, notably including immunotherapy. Preclinical models suggest that multiple pathways down-regulated in tumors as a mechanism of immune escape and evasion may be re-expressed in response to epigenetic therapy and may augment the effectiveness of PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade.39 Thus epigenetic therapy may prime tumors to respond to immunotherapeutic strategies by overcoming tumor mechanisms including increased antigen presentation, up-regulation of PD-L1 expression and augmentation of interferon and cytokine signaling within the tumor.40

In addition to next generation hypomethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors, there are a host of novel epigenetic therapies targeting chromatin modifying enzymes now being translated into clinical testing in lung cancer and other solid tumors. EZH2 inhibitors are currently in early phase clinical development, and may be of relevance in the treatment of lung cancers including small cell lung cancers, in which EZH2 appears to be frequently overexpressed. A DOT1L inhibitor is being developed for acute leukemias defined by alterations in MLL, a gene family of histone methyltransferases also commonly mutated or otherwise genetically altered in lung cancer. Beyond targeting chromatin modifying enzymes that write or erase histone marks, bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) histone binding proteins possess what may be termed a “reading” function focused on histone acetylation; trials of inhibitors of the protein-protein interaction have been initiated in small cell lung cancer.41–43 The evolving knowledge of the prevalence and array of identifiable defects in chromatin regulators and DNA-methylation phenotypes suggests a large number of potential targets and strategies for epigenetic therapy beyond those which have formed the basis of much clinical investigation of epigenetic therapies to date. Thoracic oncologists can expect an expanding portfolio of novel epigenetically targeted agents with potential for clinical application to lung cancer over the next several years.

3. EGFR MUTATION-POSITIVE NSCLC

The approach toward lung cancer therapeutics has undergone a major paradigm shift in the last ten years. The impetus to move toward larger and more frequent biopsies and perform upfront genotyping at the time of diagnosis came in large part with the recognition that between 10 and 20% of US lung cancer patients had tumors carrying an EGFR mutation, a biomarker of oncogene addiction that correlates strongly with response to EGFR TKIs.44 There are several subtypes of EGFR mutations, but the two most frequent, L858R and del19, comprise 90% of the cases and are also the most tightly associated with robust response to therapy.45 In this review, L858R and del19 mutations will be referred to collectively as “common mutations”. We will review the current treatment recommendations for EGFR-mutant patients and the pivotal studies that shape the basis for the recommendations.

3.1 Advanced Stage Disease: First-Line

When EGFR mutations were first discovered, several single arm phase 2 studies were quickly performed confirming that patients with advanced lung cancer and common EGFR mutations did very well with first-line gefitinib and erlotinib therapy, with response rates of 60–75% and median progression-free survival (PFS) of approximately 9–10 months.46–48 While these results were two-to-three fold better than what was achieved with the current standard-of-care platinum doublet chemotherapy regimens, there was still some skepticism about whether a randomized trial would favor an EGFR TKI or not, because EGFR-mutant patients seemed to do better on chemotherapy than EGFR wild-type patients. However, this debate was settled when the IPASS study was published.

IPASS was a large randomized trial of about 1200 patients done in Asia, where EGFR mutations are 2–3 times more common than in Western countries.6 All the subjects were non-smokers with adenocarcinoma, both of which are clinical features that have been associated with increased incidence of EGFR mutations. Patients did NOT have to have an EGFR mutation to enter the trial, but among the subset that had tissue available for EGFR mutation testing, about 60% were positive for common EGFR mutations. The IPASS design compared 1st-line gefitinib to 1st-line chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel for up to 6 cycles with a primary end-point of PFS. The results showed that in the overall intention-to-treat population gefitinib had an improved PFS compared to chemotherapy with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.74 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65–0.85 (Table 2). However, when examining the subset of patients with tissue available for genotyping, it became clear that the overall positive results for gefitinib were exclusively due to the contribution from the EGFR-mutant cohort of patients, who had an even more impressive PFS benefit from first-line gefitinib, HR= 0.48 (95% CI0.36, 0.46). Conversely, the EGFR wild-type patients showed that front-line EGFR TKI was a harmful strategy for them with HR = 2.85 (95% CI 2.1, 4.0). In addition to a PFS benefit, patients with EGFR mutations treated with gefitinib had an improved quality of life compared to those treated with chemotherapy.49 Hence, practice changed significantly with the IPASS publication in two major ways: 1) the importance of early genotyping was appreciated and giving 1st-line EGFR TKIs to patients with EGFR mutations became an accepted therapeutic strategy and 2) because the wild-type patients did so poorly with 1st-line gefitinib in lieu of chemotherapy, it became obvious that if one didn’t know the mutation status for a patient, then EGFR TKIs should not be given, at least in the 1st-line setting.

Table 2.

Summary of Randomized Trials Examining Genotype-Customized First-Line EGFR TKI Therapy

| Study | Treatment | N | Response Rate |

Median PFS, mo |

HR for PFS (95% CI) |

Median OS, mo |

HR for OS (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPASS 6, 54 | Gefitinib | 132 | 71% | 9.6 | 0.48 (0.36, 0.64) | 21.6 | 1.00 (0.76, 1.33) |

| Carbo/Pac | 129 | 47% | 6.3 | 21.96 | |||

| WJTOG 34057* | Gefitinib | 86 | 62% | 9.2 | 0.49 (0.35, 0.71) | NR | NR |

| Cis/doce | 86 | 31% | 6.3 | NR | |||

| NEJ 0028 | Gefitinib | 114 | 74% | 10.4 | 0.36 (0.25, 0.51) | 30.5 | No ratio provided P=0.31 |

| Carbo/pac | 114 | 31% | 5.5 | 23.6 | |||

| OPTIMAL*50 | Erlotinib | 83 | 83% | 13.1 | 0.16 (0.10, 0.26) | NR | NR |

| Carbo/gem | 82 | 36% | 4.6 | NR | |||

| EURTAC*51 | Erlotinib | 86 | 58% | 9.7 | 0.37 (0.25, 0.54) | 19.3 | 1.04 (0.65, 1.68) |

| Carbo or cis/gem or doce | 87 | 15% | 5.2 | 19.5 | |||

| Lux-Lung 352 | Afatinib | 230 | 69% | 11.1 | 0.58 (0.43, 0.78) | 28.2 | 0.88 (no CI provided) |

| Cis/pem | 115 | 44% | 6.9 | 28.2 | |||

| Lux-Lung 3: Afatinib arm, common mutations only* | 203 | 75% | 13.6 | 0.47 (0.34, 0.65) | 31.5 | 0.78 (0.58, 1.06) | |

| Lux-Lung 3: Cis/pem arm, common mutations only* | 104 | 43% | 6.9 | 28.6 | |||

| Lux-Lung 3: Afatinib arm, exon 19 del only56 | 112 | NR | NR | 0.28 (0.18, 0.44) | 33.3 | 0.54 (0.36, 0.79) | |

| Lux-Lung 3: Cis/pem arm, exon 19 del only | 57 | NR | NR | 21.1 | |||

| Lux-Lung 653 | Afatinib | 242 | 74% | 11.0 | 0.28 (0.20, 0.39) | 23.1 | 0.93 (no CI provided) |

| Cis/gem | 122 | 31% | 5.6 | 23.5 | |||

| Lux-Lung 6: Afatinib arm, common mutations only* | 216 | NR | 11.0 | 0·25 (0.18, 0.35) | 23.6 | 0.83 (0.62, 1.09) | |

| Lux-Lung 6: Cis/gem arm, common mutations only* | 108 | NR | 5.6 | 23.5 | |||

| Lux-Lung 6: Afatinib arm, exon 19 del only56 | 124 | NR | NR | 0·20 (0·13 0·33) | 31.4 | 0.64 (0.44, 0.94) | |

| Lux-Lung 6: Cis/gem arm, exon 19 del only | 62 | NR | NR | 18.4 | |||

Only L858R and del 19 mutants were included in this study; NR = no mature data reported

After IPASS, several other randomized trials were completed in rapid succession, each confirming similar benefits from first-line gefitinib or erlotinib, primarily for patients with common EGFR mutations (Table 2).7, 50–53 The EURTAC study was especially important from this collection of studies as it was the first such trial performed in a Western population.52 In EURTAC, Spanish and Italian EGFR mutant patients (common mutations only) treated with first-line erlotinib had improved PFS compared to investigator choice chemotherapy (either cisplatin/docetaxel or cisplatin/gemcitabine), HR = 0.37 (95% CI 0.25−0.54). None of the studies examining first-line gefitinib or erlotinib have demonstrated a survival advantage for the genotype-directed therapy, presumably because EGFR mutants have a very robust response rate and PFS when EGFR TKIs are given in the 2nd or later-line setting, thus allowing them to “catch up” to the benefit achieved with first-line therapy.

More recently, two randomized studies were completed with the 2nd-generation EGFR TKI afatinib as first-line therapy for EGFR mutation-positive patients.54, 55 In contrast to the 1st-generation drugs erlotinib and gefitinib, 2nd-generation EGFR TKIs are “irreversibly binding” meaning that instead of ATP-competitive binding at the receptor, the drug forms a direct chemical covalent bond with the EGFR receptor. In addition, afatinib binds all the ErbB receptors, not just EGFR. Lux-lung 3 was a global study comparing afatinib to cisplatin/pemetrexed and Lux-lung 6 was performed in China only, comparing afatinib to cisplatin/gemcitabine. Similar to the prior studies, the afatinib trials showed a superior PFS, response rate, and quality of life for genotype-directed treatment, particularly among the 90% of trial participants with common EGFR mutations. As a result, afatinb was FDA approved in 2013 as first-line therapy for patients with L858R and deletion 19 EGFR mutations. At the 2014 ASCO meeting, we also learned that among exon 19 deletion mutants, first-line afatinib appears to improve OS compared to first-line chemotherapy.56 Although these results were from a post-hoc subgroup analysis, the survival benefit was large (approximately one year), and was replicated in both Lux-lung 3 and Lux-lung 6 with highly significant p-values (Table 2). The L858R patients did not have a survival advantage with afatinib, similar to results from other studies with gefitinib and erlotinib.

Because of this collection of research, the current standard approach in the US is to test all patients with newly diagnosed advanced adenocarcinoma for EGFR mutations and, if positive for a common mutation, to treat with either afatinib or erlotinib.57 If patients are symptomatic from their cancer and cannot wait for the results of mutation testing to return, chemotherapy should be started as EGFR TKIs should only be given in the first-line setting to patients known to have an EGFR mutation. There are uncommon mutations that are still considered sensitizing to EGFR TKIs such as L861Q, G719X and S768I. However, it is important to note that the exon 20 insertion/deletion mutations are typically not sensitive to erlotinib, gefitinib and afatinib.58

3.2 Advanced Stage Disease: Special considerations for EGFR mutant patients

There are several considerations in the management of EGFR mutant patients that are unique compared to historical approaches for treating lung cancer: 1) When to start EGFR TKIs if chemotherapy was given prior to mutation test result availability, 2) Should EGFR TKIs be continued beyond progression and, 3) How to work-up EGFR mutation positive lung cancer with acquired resistance to the first EGFR TKI. There are no definitive randomized trials that give us direction about these issues, but clinical experience is now large and consensus recommendations are emerging. For patients that were unable to wait for EGFR mutation test results prior to starting first line chemotherapy, it is always difficult to know when and how to start an EGFR TKI after the mutation is discovered. Options range from beginning the TKI immediately after the test results returns to not until the patient progresses and 2nd-line therapy is indicated. One popular approach is to complete 4–6 cycles of the first-line chemotherapy (assuming the patient is tolerating therapy and is not progressing through it) and then switch to the EGFR TKI, similar to a maintenance approach, however no clinical trials have addressed this specific sitution.58

A more common question is under what circumstances to continue an EGFR TKI when the patient is progressing on therapy. The discussion arises because it has been observed that even when EGFR mutants are radiographically progressing through an EGFR therapy, removal of that therapy can hasten a clinically-significant flare in the disease in up to 25% of cases, leading to hospitalization and/or death in approximately one week in the initial publication.59 The disease flare is thought to be due to a mix of clones within the tumor, some of which are still sensitive to the EGFR TKI and remain under control even while other clones are growing. Removal of the suppressive TKI can allow many more cells to divide compared to keeping the suppressive TKI on board.

EGFR mutants have two distinctive patterns of progression not historically distinguished in lung cancer treatment paradigms: 1) progression in only one site while the rest of the disease remains stable, and 2) very slow and indolent progression in multiple anatomic locations. There is mounting evidence suggesting that if progression is only in one location then local treatment (surgery or radiation) followed by continued EGFR TKI therapy can yield good outcomes.60, 61 In one study using this approach, EGFR mutant patients had controlled disease for a median of 6 months after the locally-directed therapy before further progression was noted.60 In addition, clinical experience is accumulating supporting the notion that patients who are having slow and indolent progression while on an EGFR TKI can achieve significant additional time on therapy after meeting RECIST criteria for progression.62, 63 One single institution experience documented that 88% of EGFR patients received ongoing EGFR TKI beyond RECIST-defined progression and the median time until a change in therapy was necessary from that point was 10 months.63

Once a patient is progressing sufficient to demand a change in systemic therapy, there is an additional question of whether one should stop the EGFR TKI and switch to chemotherapy or continue the EGFR TKI along with adding chemotherapy. Again, the observation of a clinically-significant flare in disease if the EGFR TKI is stopped has fueled interest in this question. Prospective randomized studies are in process which will provide further guidance but retrospective studies suggest that response rates may be higher if the EGFR TKI is continued while chemotherapy is added.64

Considering a biopsy at the time of progression on the initial EGFR TKI is an emerging standard for EGFR mutants.56 Initially this was a maneuver primarily done for research purposes, in order to gain a better understanding of the range of molecular mechanisms of acquired resistance and to consider customizing clinical trial options for patients. It then became appreciated that a small portion of patients would have a transformation from adenocarcinoma harboring an EGFR mutation to small cell lung cancer with the same EGFR mutation as an escape mechanism from their EGFR TKI.65, 66 This transformation, although rare, facilitated broader clinical interest in repeat biopsies because the biopsy might indicate a new therapeutic direction. In the current era, data is rapidly accumulating that 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs may have high activity among those with acquired resistance by virtue of the T790M mutation in exon 20, the single mutation that accounts for 50–65% of acquired resistance, see below.67, 68 This provides yet an additional and compelling clinical indication for biopsy at the time of acquired resistance.

3.3 Treatment of Acquired Resistance

Even though initial therapy with an EGFR TKI is quite effective, acquired resistance still develops after 10–15 months. When the 2nd-generation EGFR TKIs were developed, there was great hope that these would be highly effective for patients with acquired resistance because laboratory studies showed these compounds had a high level of activity against T790M in vitro.69 Unfortunately, in clinical trials all three 2nd-generation EGFR TKIs tested (neratinib, afatinib and dacomitinib) have had disappointing results with response rates in the single digits.70–72 The explanation behind the discordant pre-clinical and clinical results is thought to be that the 2nd-generation drugs have a high degree of wild-type EGFR potency so dose escalation is limited by rash, diarrhea, and other side effects resulting from wild-type EGFR inhibition. Hence, in patients it appears difficult to achieve drug concentrations sufficient to inhibit T790M.

The first successful clinical trial for EGFR acquired resistance was a phase I trial examining the combination of afatinib and cetuximab.73 This trial expanded when activity was observed to ultimately include 93 patients. The response rate was 32%, significantly higher than the 7% observed with single agent afatinib. However, the toxicity of this regimen is not insignificant, with 18% of patients having grade 3 acneiform rash (rash that limits ADLs and covers >30% of the body surface area). Interestingly, the pre-clinical evidence for this combination suggested that T790M mutants would preferentially benefit,74 however the clinical observation has been that response is roughly equal regardless of T790M status.

A new class of 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs have recently entered clinical study.67, 68 These differ from the prior generations of EGRF TKIs because while they have potent inhibition of both activating EGFR mutations and T790M, wild-type inhibition is close to zero, allowing dose escalation to concentrations that can effectively overcome acquired resistance. Two compounds have had mature results presented in abstract form thus far, CO-1686 and AZD9291. Both have demonstrated response rates of about 60% among those with biopsy-proven T790M. Mature PFS is not yet available but responses appear to be durable for at least 6 months in most patients in the preliminary data. As suspected, rash and diarrhea are extremely uncommon during therapy with 3rd-generation EGFR TKIs. CO-1686 causes hyperglycemia, which is typically controlled with oral medications.

3.4 Early Stage Disease

Whenever there is a successful strategy for treating advanced stage disease, such as EGFR TKIs for patients with EGFR mutations, there is interest in moving the therapy from late stage disease to early stage disease with the hope of increasing cure rates. Studies are just beginning that will look at incorporation of EGFR TKIs into multi-modality therapy for stage III disease. However, two studies have been completed offering preliminary data about adjuvant erlotinib. The SELECT study was a single-arm multi-center study of 2 years of adjuvant erlotinib for patients with common EGFR mutations.75 One hundred patients were treated (stage I n=45, stage II n=27, stage III n=28) and the primary end-point of 2-year disease free survival was 89% (by stage: I - 96%, II - 78%, IIIA - 91%), which was significantly improved compared to the pre-defined historical control 2-year disease free survival for EGFR mutants followed with observation alone. In addition, after a median duration of follow-up of over 3 years, of the 29 patients that recurred, only 4 recurred while one erlotinib and 25 recurred after erlotinib was completed, raising speculation that duration of therapy may be important. The RADIANT study was a randomized study of 2 years of adjuvant erlotinib vs. placebo that enrolled a broader population of lung cancer patients among which 16% harbored EGFR mutations.76 Though the overall study was negative, the subgroup analysis of EGFR mutants suggested that erlotinib provided a disease-free survival advantage with HR = 0.61 (95% CI 0.38, 0.98) but no OS advantage in this preliminary study. A more definitive prospective randomized trial including only EGFR mutants and powered to examine OS is set to begin this year.

4. HER 2/3 POSTIVE NSCLC

4.1 The role of HER2 and HER3 in NSCLC

HER2 and HER3 (also known as ERBB2 and ERBB3, respectively) are members of the HER/ERBB receptor tyrosine kinase family, which also includes EGFR and HER4. Although these receptors all mediate cell proliferation and survival through downstream MAPK and PI3K pathways, they vary in regards to the ability to bind ligand and the presence of an active tyrosine kinase domain. For example, HER2 has no known high-affinity ligand and therefore utilizes homo- or hetero-dimerization for activation, and HER3 has no tyrosine kinase activity and relies on heterodimerization to induce downstream signaling. The most powerful signaling heterodimer is that of HER2 and HER3, which can function as an oncogenic unit.77

Oncogenic HER2 kinase domain mutations were first reported in NSCLC in 2004.78 Since that time, several studies have found the rate of kinase domain HER2 mutations in NSCLC to be approximately 2–4%.79–81 These mutations are most commonly in-frame insertions in exon 20 with duplication of amino acids YVMA at codon 775; infrequently, insertions in other codons or point mutations can be found that lead to constitutive activation of downstream pathways resulting in cell growth and survival. More recently, extracellular domain mutations were detected in HER2 and found to be oncogenic, including a S310F mutation in exon 8 detected in 1 of 188 lung adenocarcinomas,82 a S310Y mutation in 1 of 63 squamous cell lung cancers,83 and 1 S310F and 1 S310Y mutation in 258 lung adenocarcinomas sequenced by the Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Across these studies, the frequency of extracellular domain mutations appears to be <1%.

In contrast to HER2, there have been no reports of mutations in the HER3 gene. However, HER3 has been implicated as an escape mechanism for drugs that inhibit signaling through EGFR and HER2.84, 85 Attempts at therapeutically targeting both HER2 and HER3 are ongoing.

4.2 Clinical features of patients with HER2-mutated NSCLC

Patients with HER2-mutant NSCLC have distinct clinicopathologic characteristics, similar to those whose tumors harbor EGFR mutations. In the largest reported study to date of 65 patients with HER2-mutant NSCLC, the median age of diagnosis was 60.4 years (range 31–86), 69% were female, 52% were never-smokers, and all tumors were adenocarcinomas.81 Although HER2 mutations are relatively rare in lung cancer, the rate of detection can be enriched by testing never-smoker patients with adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous histology without an EGFR mutation, in which case the frequency is approximately 14%.79 HER2 mutations are mutually exclusive with point mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, MEK1 and AKT, as well as rearrangements in ALK.80

4.3 Preclinical and clinical data for therapeutics targeting HER2 and HER3

Both small molecular inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting HER2 are under investigation. Currently there is limited data for patients treated on prospective clinical trials, however preclinical studies and retrospective data from patients treated with off-label, commercially available agents show promise in targeting HER2 in those with HER2-mutant NSCLC. Below are several compounds under investigation.

4.4 Trastuzumab

In contrast to breast cancer, HER2 overexpression or amplification does not predict for benefit from trastuzumab in lung cancer. However, the presence of a HER2 mutation may be a predictive biomarker for response to trastuzumab in NSCLC. In a retrospective study of 16 patients with HER2-mutant NSCLC, a total of 22 anti-HER2 treatments were assessed.81 Of the patients who received trastuzumab-based regimens (trastuzumab combined with carboplatin, paclitaxel, carboplatin/paclitaxel, vinorelbine, or docetaxel), the response rate was 60% (9 out of 15 regimens tested) and disease control rate was 100%. One patient received trastuzumab alone and had a partial response (PR).

4.5 Afatinib

Afatinib is an irreversible small molecular inhibitor of EGFR and HER2 that is approved for use in the first-line setting for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. In lung cancer cell lines harboring a HER2 insertion mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain, afatinib was effective at inhibiting survival, whereas erlotinib was not.86 Interestingly, afatinib was also effective at inhibiting survival in cell lines transformed with the HER2 extracellular domain mutation.82 The clinical activity of afatinib in HER2-mutant NSCLC has been evaluated in the same retrospective study discussed above.81 Three patients who had progressed after receiving trastuzumab-based therapy were treated with afatinib, which resulted in 100% disease control rate (1 PR and 2 stable disease [SD]). In the only prospective study with afatinib in this population, 5 patients with NSCLC harboring a HER2 kinase domain mutation were treated with afatinib, followed by the option to add weekly paclitaxel at 80mg/m2 to afatinib at progression.87 Of the 3 patients evaluable for response (2 patients withdrew early due to toxicity), 2 had a partial response to afatinib alone and 1 had stable disease with afatinib and a PR once paclitaxel was added.

4.6 Dacomitinib

Dacomitinib is an irreversible pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor. A Phase II study in patients that included patients with NSCLC and HER2 amplification or mutation with any number of prior lines of therapy treated patients with dacomitinib 45mg or 30mg with the option to escalate to 45mg once daily.88 Of the 16 evaluable patients in the HER2 cohort, there were 2 with a partial response, both of whom had a HER2 mutation. Final results from this study are pending.

4.7 Neratinib

Preclinical mouse models of HER2-mutant lung cancer have demonstrated that HER2 inhibition plus mTOR inhibition results in significant tumor shrinkage over either alone.89 Based on this and other preclinical data, the combination of neratinib, an irreversible pan-HER small molecule inhibitor, and temsirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, was studied in a Phase I trial including patients with multiple tumor types.90 Six patients out of the 60 on the trial had HER2-mutant NSCLC. Among them, two had a PR (one of whom had prior trastuzumab) and the remainder had stable disease.

4.8 MM-111

MM-111 is a bispecific fully human antibody targeting HER2 and HER3. In preclinical studies of HER2-overexpressing cancer cells, MM111 inhibits cell proliferation, particularly when used in combination with other HER2 inhibitors such as trastuzumab.91 A Phase I trial in multiple tumor types with HER2 positivity is testing MM-111 combined with various HER2-targeted agents and chemotherapeutics to determine the maximally tolerated dose, safety and efficacy. This drug has not yet been tested in patients with HER2-mutant NSCLC.

4.9 MEHD 7945 A

In contrast to the previously discussed compounds, MEHD 7945 A does not target HER2, but instead is a dual-action human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets EGFR and HER3. In cell lines and xenograft models of tumors resistant to the EGFR inhibitors cetuximab or erlotinib, MEHD 7945 A was able to overcome resistance and inhibit tumor growth.92 Clinically, the safety and activity of MEHD 7945 A was studied in a Phase I trial in multiple tumor types.93 Nine patients with NSCLC were included, of which 2 had stable disease as their best response. The final report from this study is pending.

4.10 MM-121

Unique compared to the other drugs discussed here, MM-121 is a monoclonal antibody that only targets HER3. It is being developed in combination with other targeted agents or chemotherapeutics, which is not surprising given the lack of known alterations in HER3 in human cancers. Specifically, MM-121 is being tested in combination with erlotinib, with early signals of clinical benefit in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC and erlotinib resistance.94

5. ALK-POSITIVE NSCLC

Chromosomal rearrangements of ALK are present in 3–7% of NSCLC. The resulting ALK fusions, such as EML4-ALK, function as potent oncogenic drivers and lead to a state of oncogene addiction. In the clinic, this phenomenon underlies the marked responsiveness of ALK-positive tumors to small molecule ALK tyrosine kinase inhibition. Crizotinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) of ALK, ROS1 and cMET, was the first ALK inhibitor tested in the clinic and helped to establish ALK as a therapeutic target in NSCLC.12 To date, nine other ALK inhibitors have now entered clinical development, with promising early results in both crizotinib-naïve and crizotinib-resistant disease. Here we review the latest data on crizotinib and select next-generation ALK inhibitors in TKI-naïve patients with ALK-positive NSCLC.

5.1 Crizotinib

Phase 1 and 2 studies have shown that crizotinib is highly active in patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC. In the phase 1 trial (PROFILE 1001), the objective response rate among 143 evaluable patients was 61%, and median PFS was 9.7 months.95 Updated results from the phase 2 study of crizotinib (PROFILE 1005) were recently reported in the US FDA label. Among 765 patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC, the objective response rate was 48% and median duration of response was 11 months;96 the follow-up of these phase 2 patients was too short to evaluate PFS. Based on the response rates observed in the phase 1 and 2 studies, along with its favorable side effect profile, crizotinib was granted accelerated approval by the FDA in August 2011 for patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC. This approval occurred almost exactly 4 years after the first report of ALK rearrangements in NSCLC.97

Recently, the results of the first prospective, randomized phase 3 trial comparing crizotinib with standard chemotherapy in advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC (PROFILE 1007) were reported.11 In this study, 347 ALK-positive patients who had failed one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen were randomized 1:1 to receive either crizotinib as their second-line therapy, or pemetrexed or docetaxel chemotherapy. Compared with standard single-agent chemotherapy, treatment with crizotinib resulted in a significantly longer progression-free survival and a tripling of the objective response rate. The median progression-free survival with crizotinib was 7.7 months by independent radiology review, compared to 3.0 months with chemotherapy. Consistent with previous single-arm studies, the response rate with crizotinib was 65%, as opposed to 20% with chemotherapy, thus confirming the significant antitumor activity of crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive NSCLC.

In this study, crizotinib was more active than either pemetrexed or docetaxel chemotherapy in ALK-positive NSCLC.11 Consistent with previous studies in unselected patients with advanced NSCLC, the efficacy of second-line docetaxel in ALK-positive NSCLC was minimal, with a median progression free survival of 2.6 months and an objective response rate of 6.9%.98 In contrast, pemetrexed showed greater activity than expected based on previous second-line studies.99 Median progression free survival was 4.2 months in ALK-positive patients, as compared with 3.5 months in unselected NSCLC patients with adenocarcinoma histology. The response rate to pemetrexed was also higher in this study at 29.3%, as compared with 12.8% in the general population of lung adenocarcinomas.100 While these findings suggest that patients with ALK-positive NSCLC may be more responsive than average to pemetrexed-based chemotherapy, the benefit of pemetrexed appears to be less than that originally suggested by small retrospective studies,101, 102 and importantly, significantly less than that with crizotinib.

In a prespecified interim analysis, OS was found to be similar between the crizotinib and chemotherapy arms with a median OS of 20.3 and 22.8 months, respectively.11 This analysis was immature with a total of 96 deaths (40% of the required events) and censoring of over 70% of patients in either treatment arm. In addition, the analysis was likely confounded by the high crossover rate of patients in the chemotherapy group. Nearly 90% of patients who were treated with chemotherapy and had disease progression crossed over to receive crizotinib. This issue has similarly complicated the analysis of OS in multiple randomized phase 3 studies of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced EGFR mutant NSCLC. In these studies where the crossover rate from chemotherapy to targeted therapy ranged from 64% to 95%, no difference in OS was demonstrated despite substantial improvements in progression-free survival with the targeted therapy.

Several important issues regarding the role of crizotinib in ALK-positive NSCLC remain to be addressed. In many countries, crizotinib is an approved therapy for patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC with no requirement for prior treatment. As a result, crizotinib can be prescribed as first-line therapy. While the first-line use of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC has been established in multiple randomized phase 3 studies, there is limited data on the use of crizotinib in the first-line setting. In the original phase 1 study, there were 24 patients who received crizotinib as their first systemic therapy.95 In this small cohort, the objective response rate was 64% and median progression-free survival was 18.3 months, suggesting that first-line crizotinib may be at least equivalent if not more effective than crizotinib in the second-line setting and beyond. A randomized phase 3 trial comparing crizotinib with platinum/pemetrexed chemotherapy in newly diagnosed, advanced ALK-positive NSCLC (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01154140) has recently completed enrollment, and results may be reported at ASCO 2014. A similar phase 3 trial in Asia comparing first-line crizotinib to platinum/pemetrexed chemotherapy in ALK-positive NSCLC patients (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01639001) is ongoing.

5.2 Next-generation ALK Inhibitors: Alectinib and Ceritinib

Alectinib (RO5424802) is a highly potent and selective TKI targeting ALK, but not ROS1 or cMET.103 Alectinib was first evaluated in a phase 1/2 study in Japan and enrolled a total of 70 Japanese patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC who were crizotinib-naïve.104 In contrast to the PROFILE 1001/5/7 studies which used ALK FISH only, patients were identified as ALK-positive using ALK immunohistochemistry (IHC), followed by ALK FISH for confirmation. In the phase 2 portion of the study, the ORR with alectinib dosed at 300 mg twice daily was remarkably high at 94%. With a median follow-up of only 7.6 months, median PFS is not yet known, but durable responses exceeding 12 months have been reported.

Similarly, the next-generation ALK inhibitor ceritinib (LDK378) has also demonstrated high response rates in crizotinib-naïve ALK-positive NSCLC. In preclinical studies, ceritinib is also more potent and selective than crizotinib, targeting ALK and ROS1 but not cMET.105 In a global phase 1 study, ceritinib was highly active in patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC.106 Among 34 patients who had not received an ALK inhibitor and who received ceritinib at doses of 400 mg or higher, the ORR was 62%, and median PFS was 10.4 months. Of note, in contrast to the phase 1 study of alectinib, this study included both Asian and Caucasian patients. In addition, the ceritinib study required only ALK FISH testing to demonstrate ALK rearrangement, as opposed to both ALK IHC and ALK FISH. Thus, these two factors, ethnicity and diagnostic testing, could explain the differences in efficacy seen between alectinib and ceritinib in the TKI-naïve ALK-positive population.

6. ROS1, RET AND NTRK1 POSITIVE NSCLC

6.1 Biology

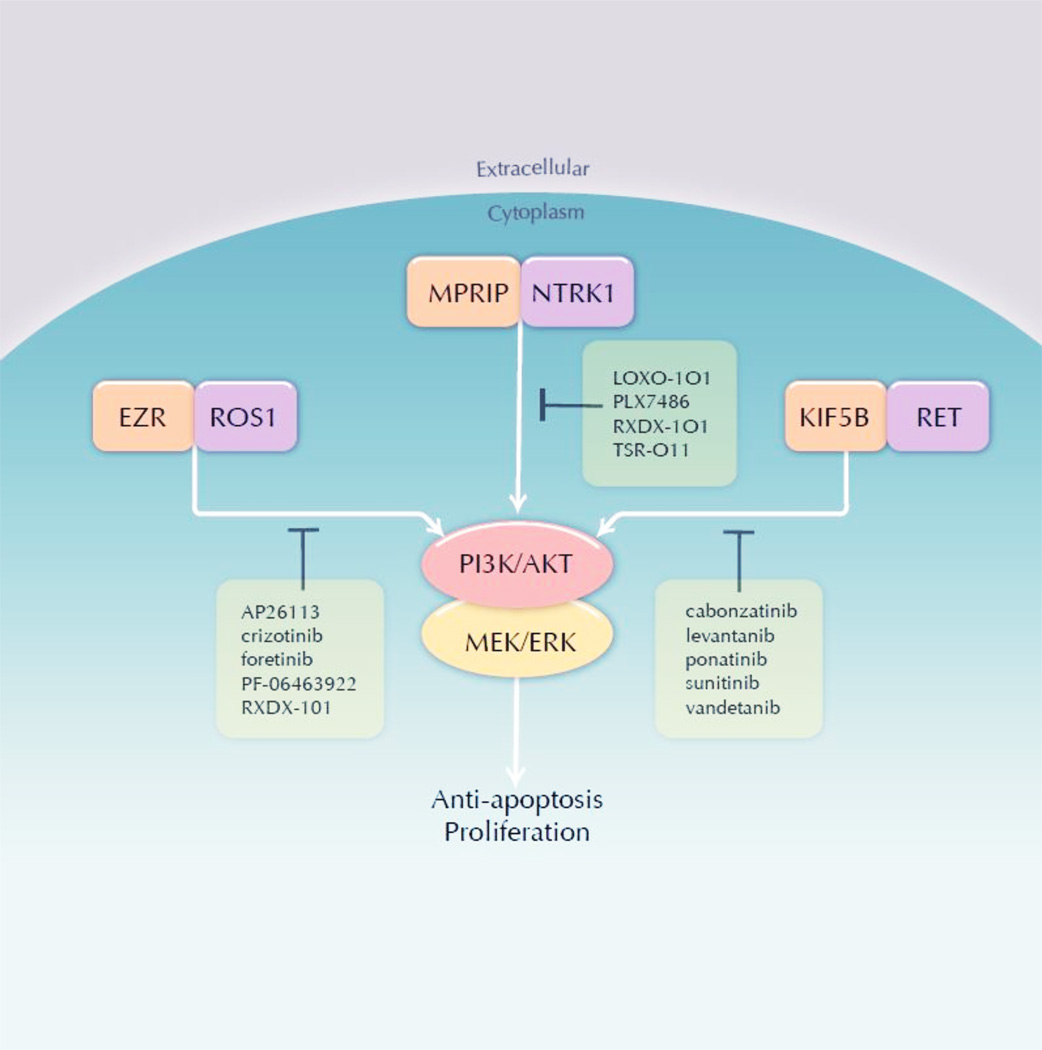

Gene fusions result from large-scale inter- or intra- rearrangements or chromosomal deletions that join pieces of two disparate genes and result in chimeric mRNA transcripts and proteins. The gene fusions described here contain sequences from the 5’ region of an unrelated partner gene and the 3’ region of genes encoding receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs): ROS1, RET, and NTRK1. These gene fusions always have an intact kinase domain encoded by the 3’ gene region, but contain varying 5’ sequences from other genes. These partner genes typically provide 2 critical components: a promoter that allows sufficient transcription of the novel gene and sequences that encode oligomerization domains. ROS1, RET, TRKA (encoded by the NTRK1 gene) are not highly expressed in most lung adenocarcinomas, but their upstream partner joins a promoter that drives sufficient expression in the tumor cell.108–110 The typical mode of activation for these RTKs cannot occur because they lack the extracellular domains harboring the ligand-binding domain; however, the oligomerization domain, for example coiled-coil domains encoded by the partners KIF5B, CCDC6, EZR, TPM3 and MPRIP facilitate dimerization of the fusion protein.97, 111, 112 It is currently unknown whether different fusion partners, which can target the fusion proteins to different cellular compartments, induce differential tumor behavior, including drug sensitivity.113 Activation of the kinase domain initiates a downstream signaling cascade that ultimately activates MAPK and AKT signaling, which leads to cellular proliferation among other tumorigenic properties.112, 114, 115 This dominant signaling role makes targeted inhibition of these oncogenes an attractive therapeutic strategy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ROS1, NTRK1 and RET inhibitors.

6.2 Incidence

Multiple studies have investigated the incidence of the oncogenic fusions using a variety of techniques, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), IHC, next generation sequencing (NGS) of RNA and DNA, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR); however, an approved companion diagnostic is not yet available for these oncogenes.108, 111, 112, 114, 116–118 Typically, these oncogene fusions do not overlap with other dominant oncogenes, but unbiased studies have demonstrated overlap of ROS1 fusions and EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF mutations, similar to dual oncogenes observed in ALK positive cases.117–122 The incidence of ROS1, RET, and NTRK1 gene fusions appears to be in the range of 1–3%, although in studies using enriched cohorts (i.e., negative for other oncogenes) the reported incidence is higher.108, 111, 112, 114, 116–118 Although associations have been drawn with age, sex, and smoking history, there is no reliable clinical selection for oncogenic fusions and thus these factors should not be used as criteria for selection of patients to undergo testing.111, 112, 114, 116, 123, 124 Although these gene fusions are widely associated with adenocarcinoma histology, this is not an ideal selection criteria as squamous cell and other histologies have been associated with ROS1, RET, and NTRK1 fusions.108, 116, 117, 125, 126

6.3 ROS1, RET and NTRK in other disease types

Although these oncogenic fusions occur infrequently in lung cancer, interest in these targets is bolstered by their occurrence in other malignancies. ROS1 has been detected in gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, Spitzoid neoplasms and numerous others.113, 119, 127, 128 RET fusions have long been identified in papillary thyroid cancer but have also been identified in CMML and others.128–130 An oncogenic NTRK1 fusion was first detected in a colorectal cancer specimen, later found to be prevalent in papillary thyroid cancers, and now identified in multiple other tumor types.128, 129, 131–133 Many TRKA inhibitors have activity against two homologous RTKs, TRKB (NTKR2) and TRKC (NTRK3). These genes are also involved in gene fusions across multiple cancer types, perhaps broadening the appeal of these pan-TRK inhibitors.134–137

Inhibitors of ROS1, RET and TRK

6.4 ROS1

Crizotinib (Pfizer) has been approved for use in ALK+ NSCLC. ROS1 has high homology to ALK and many ALK inhibitors also display ROS1 inhibition.113 An expanded phase I trial is the first trial to report clinical outcomes of ROS1+ NSCLC patients treated with crizotinib (NCT00585195). The most recent update of 35 patients demonstrated an objective response rate (ORR) of 60% and a 6-month PFS rate of 76%, very similar to studies of the same drug in ALK+ NSCLC patients.95, 138 Foretinib (XL-880, GlaxoSmithKline) is a multi-kinase inhibitor with activity against ROS1 (as well as RET, MET, AXL and other kinases) that has a planned ROS1 cohort in an upcoming clinical trial (NCT01068587).139 Ceritinib (LDK378, Novartis) is a potent second generation ALK inhibitor that displays weaker ROS1 inhibition;105 however, this drug is not currently in clinical trials enrolling ROS1+ NSCLC patients. AP26113 (Ariad) is currently in clinical trials for ALK+ NSCLC and also has activity against ROS1, but is currently not yet enrolling ROS1+ NSCLC patients (NCT01449461). PF-06463922 (Pfizer) is a next generation ALK/ROS1 inhibitor that is currently enrolling crizotinib-naïve or TKI-resistant ROS1 patients (NCT01970865).140

6.5 RET

Multiple RET inhibitors are undergoing clinical trials in RET+ NSCLC patients and many of these drugs are multi-kinase inhibitors. A clinical trial of cabozantinib (XL184, Exelixis), a RET inhibitor (in addition to MET and VEGFR2) is currently accruing RET+ NSCLC patients (NCT01639508). Early results from this trial demonstrated confirmed partial responses (PR) in 2 patients and prolonged stable disease (31 weeks) in a third patient demonstrating early clinical activity of this RET inhibitor in RET gene fusion positive patients.141 A phase II clinical trial of vandetanib (AstraZeneca), a dual RET and EGFR inhibitor, in RET+ NSCLC is currently accruing patients (NCT01823068). A patient treated off-protocol with vandetanib 300mg once daily showed a clinical response.142 An additional patient treated with off-protocol vandetanib showed prolonged stable disease 6 months on drug.143 Lenvantinib (E7080, Eisai) is multi-kinase inhibitor (VEGFR1–3, FGFR1–3, SCFR, and PDGFR) with activity against RET and is currently enrolling patients in a phase II clinical trial (NCT01877083).144 Clinical trials of ponatinib (AP24534, Ariad), a multikinase inhibitor with RET activity, in RET+ NSCLC are planned (NCT01935336).145, 146 Sunitinib (Pfizer) is another multikinase inhibitor currently in a phase 2 clinical trial of never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma and has a secondary endpoint to evaluate benefit in patient with RET gene fusions (NCT01829217).

6.6 TRK

LOXO-101 (Loxo) is a selective pan-TRK inhibitor (TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC) that is planned to shortly enter first in man phase I clinical trials. RXDX-101 (Ignyta) is a pan-TRK inhibitor that also has ALK/ROS1 activity with reported CNS penetration and is currently in phase I clinical trials. TSR-011 (Tesaro) is an ALK inhibitor with ~10 selectivity over the TRK family of RTKs and is currently in a phase I clinical trial (NCT0204848).147 PLX7486 (Plexxikon), a pan-TRK inhibitor with additional activity against Fms, is currently in clinical trials as a single agent and in combination with chemotherapy in patients with solid tumors (NCT01804530). This study will also evaluate cancer-related pain as TRKA signaling can modulate pain: Mutations in the NTRK1 gene are the cause of the autosomal recessive syndrome of congenital insensitivity to pain with anhydrosis (CIPA).148 A major focus of next generation ALK inhibitors has been to improve CNS penetration to more effectively treat the brain metastases that occur frequently in patients demonstrating disease progression on crizotinib;149 however, CNS penetration may not be a desired effect of pan-TRK inhibitors. Inhibition of TRKB has been linked to ataxia and other serious neurologic side effects, mimicking the phenotype of the mutant stargazer (stg) mice, which demonstrate ataxia and lack brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), the TRKB cognate ligand.150, 151

6.7 Resistance

Resistance mechanisms to cognate inhibitors of ROS1 are similar to mechanisms of drug resistance observed for tumors bearing ALK fusions or EGFR mutations. The first described mechanism of resistance was a patient with a ROS1 kinase domain mutation.152 This mutation, G2032R, is analogous to the ALK G1202R and adjacent to the D1203N and S1206Y mutation located at the solvent front; all of these mutations induce resistance to crizotinib.153–155 Preclinical data suggests that foretinib and PF-06463922 can inhibit ROS1 G2032R and that AP26113 can overcome the predicted ROS1 gatekeeper mutation, L2026M.139, 140, 156 Resistance mechanisms to RET inhibitors have yet to be described in NSCLC patients; however, ponatinib has demonstrated activity against oncogenic RET carrying substitutions at the predicted gatekeeper residue, V804.145, 146 TRKA harbors a bulky tyrosine residue at the conserved gatekeeper position perhaps making this position a less likely site of mutation to decrease inhibitor binding. Bypass signaling has also recently been described in a ROS1+ cell line model of drug resistance. The lung adenocarcinoma cell line with SLC34A2-ROS1, HCC78, with in vitro induced resistance to a ROS1 kinase inhibitor, switched oncogene dependence away from ROS1 to EGFR.157 This mechanism of resistant suggests the need for combination strategies to prevent or overcome resistance.

7. BRAF MUTANT NSCLC

BRAF, an oncogene encoding a RAS-regulated kinase that promotes cell growth, has generated recent interest in oncology.158, 159 The majority of BRAF mutations promote kinase activation, enhancing the kinase’s ability to directly phosphorylate MEK.159 The BRAF exon 15 mutation in which glutamine is substituted for a valine at residue 600 (V600E) destabilizes the inactive kinase conformation, leading to continual downstream phosphorylation in the MAPK signaling cascade. BRAF mutations are found in approximately 50% of melanomas, and treatment for metastatic melanoma using selectively targeted BRAF V600E inhibitors has elicited high response rates (RR).160 Yet, colorectal cancers harboring the same BRAF mutation rarely respond to BRAF inhibitor monotherapy.161 Clinical investigation targeting specific BRAF mutations in NSCLC is ongoing.

7.1 Prevalence of BRAF Mutations in NSCLC

In 2002, two studies identified BRAF mutations in 1.6–3% of NSCLC.159, 162 Based on these findings and improved genotyping techniques, a 2011 US study examined tissue from 697 patients with lung adenocarcinoma of which BRAF mutations in codons V600, D594 and G469 occurred in 3% of NSCLC cases.163 An analysis looking at the gene more broadly conducted in Italy in 2011 identified BRAF mutations in 4.9% of patient cases.164 In contrast to melanoma where 90% of BRAF mutations are V600E, approximately half of the BRAF mutations in the general NSCLC population are non-V600E.165 A comprehensive genomic study for squamous cell lung cancer identified BRAF mutations in 4% of cases, all of which were non-V600E.27 The V600E mutation has been associated with a more destructive tumor, with a poor prognosis (significantly shorter DFS and OS).164 V600E mutations have been reported as significantly more common in females than males (8.6% vs. 0.9%) and were less strongly associated with cigarette smoking.164 BRAF mutations in an Asian population were detected at a lower frequency (1.3%).166

7.2 Clinical data with BRAF inhibitors

Vemurafenib, a V600E BRAF inhibitor used in melanoma, has been associated with anti-tumor activity in NSCLC.167 Dabrafenib has been more rigorously evaluated. In an interim analysis of a single arm trial, the overall RR for single agent dabrafenib was 54%, and it was generally well-tolerated.168 As a result, the FDA granted breakthrough status to dabrafenib for V600E mutation-positive NSCLC in January 2014. During a clinical trial of the Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib for advanced NSCLC, a profound antitumor effect was seen in one patient, and that patient was subsequently found to have a kinase-inactivating non-V600E BRAF mutation, Y472CBRAF.169 When studying dasatinib in NSCLC cell lines with an endogenous inactivating BRAF mutation, the cell lines experienced senescence, which was reversed with transfection of active BRAF.169

7.3 Selected ongoing trials with BRAF inhibitors

Currently, a phase II, non-randomized, open-label study of dabrafenib as a monotherapy and in combination with trametinib, a mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, is recruiting stage IV NSCLC participants with BRAF V600E mutations (NCT01336634). A study evaluating dasatinib in subjects with advanced cancers harboring a DDR2 mutation or an inactivating BRAF mutation is currently enrolling (NCT01514864). A phase II, open-label second-line study of GSK1120212, which is closed to enrollment, compared trametinib with docetaxel in stage IV NSCLC with a mutation in KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, or MEK1 gene. (Clinicaltrials.gov No.: NCT01362296).

8. KRAS MUTANT NSCLC

8.1 Biology and Nomenclature

In lung cancer, KRAS (chromosome 12p12.1) is the principal member of the Ras family (which also includes HRAS [11p15.5] and NRAS [1p13.1]) involved in tumorigenesis. The HRAS and KRAS genes were initially identified from studies of two cancer-causing viruses, the Harvey sarcoma virus and the Kirsten sarcoma virus. These viruses were originally discovered in rats by Jennifer Harvey and Werner Kirsten, hence the name Rat sarcoma (Ras).170 NRAS is so named for its initial identification in human neuroblastoma cells. All RAS proteins undergo complex, multi-step post-translational modification including farnesylation, gerangylgerangylation, and palmitoylation.

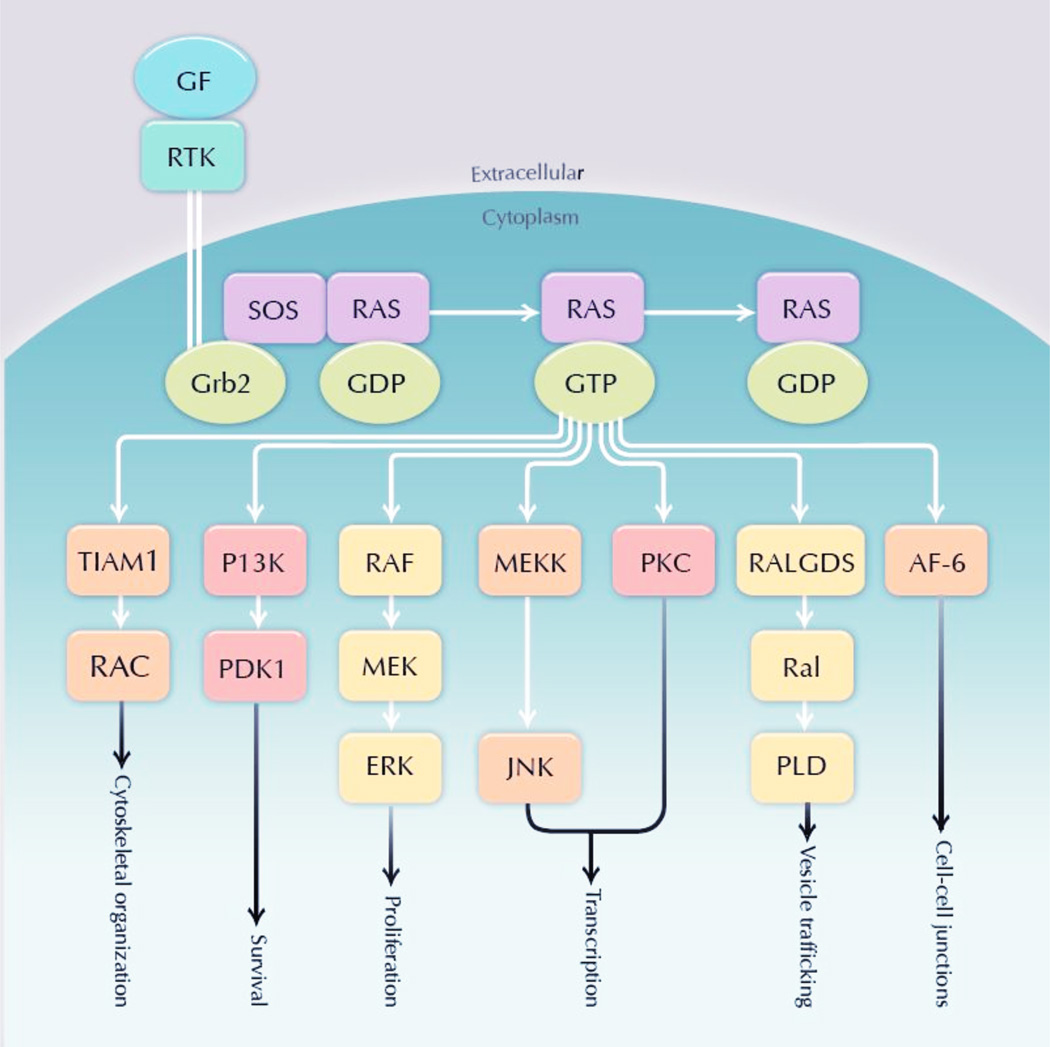

KRAS activation begins with stimulation of various upstream receptors, most EGFR in lung cancer. Adaptor proteins interact with the intracellular domain of EGFR and recruit guanine nucleotide exchange factors that interact with RAS to promote the exchange of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) for guanosine triphosphate (GTP). With binding of GTP, activated KRAS phosphorylates downstream signaling cascade proteins in until GTP is converted to GDP through a GTPase activity instrinsic to the Ras family enzymes. The end effect is that KRAS kinase and signaling capacity is higher when the enzyme is bound to GTP instead of GDP. Key downstream effectors include the RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade (controlling cellular proliferation), PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) cascade (controlling survival), and pathways affecting tumor invasion and vesicle trafficking (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

KRAS Mutations in NSCLC

8.2 Role in tumorigenesis

KRAS acquires tumorigenic properties when mutations arise that decrease its intrinsic GTPase activity. The resulting RAS proteins are locked in the GTP-bound conformation independent of upstream signals. This causes marked up-regulation of RAS kinase activity and downstream growth and mitotic signaling. Overall, RAS mutations occur in approximately 30% of all human cancers, with KRAS mutations the most common and best characterized.171 KRAS mutations result in single amino acid substitutions primarily at residues G12, G13, or Q61. In addition to lung cancer, KRAS mutations occur in 70–90% of pancreas cancer, 30–40% of colorectal cancer, 30% of biliary tract cancer, 20% of melanoma, 15% of endometrial cancer, and 15% of ovarian cancer.172

In lung cancer, KRAS mutations occur commonly at codon 12 (within exon 2) (>80%), occasionally at codon 13, and rarely at codon 61. Approximately 80% of codon 12 mutations are guanine/thymidine (G/T) (purine for pyrimidine) nucleotide transversions,173 which are considered the characteristic mutation related to tobacco smoke exposure. KRAS mutations in lung tumors from never smokers are typically G/A (purine for purine) transversions. The two most common mutations in NSCLC, G12C (approximately40% of cases) and G12V (~20%), arise from G/T transversions.174 Other principal mutations include G12D (17%), G12A (7%), and G12S (5%).175

8.3 Clinical significance

KRAS mutations occur in approximately 20–30% of NSCLC.176, 177 KRAS mutations occur predominantly in adenocarcinoma histology, have been reported rarely in squamous cell carcinoma, but have not been observed in small cell lung cancer.178, 179 In contrast to EGFR mutations and ALK and ROS1 mutations, KRAS mutations are associated with smoking.180 Among lifetime non-smokers with lung cancer, KRAS mutations occur only in 2–6% of cases.173, 181 KRAS mutations are mutually exclusive of EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 aberrations.

The prognostic role of KRAS mutations is not clear. In a meta-analysis of 24 studies incorporating various disease stages, treatments, and KRAS mutation detection methods, KRAS mutations were associated with worse survival (HR 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16–1.56).182 However, in a pooled analysis of 1,543 patients with resected early-stage NSCLC (of whom 300 had KRAS mutations); there was no difference in OS between KRAS mutant and KRAS wild type cases.173 No significant benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy was noted for wild-type cases or codon 12 mutations; among the 24 codon 13 mutation cases, adjuvant chemotherapy was deleterious (HR 5.78; 95% CI, 2.06–16.2).

In advanced NSCLC, KRAS mutations predict resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors.181 However, the mutual exclusivity of KRAS and EGFR mutations and the strong association between the latter and sensitivity to EGFR TKIs limit the clinical utility of KRAS mutations as a selection biomarker in current clinical practice. In contrast to colorectal cancer, in NSCLC KRAS mutations are not clearly associated with resistance to the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab.183

8.4 Treatment of KRAS mutant NSCLC

At the present time, there are no targeted therapies clinically available for NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations. High affinity binding to the GTP substrate has hindered the development of therapeutic agents that inhibit KRAS directly. In late 2013, initial reports of KRAS G12C inhibitors that bind to an allosteric site specific to the mutant molecule were published,184, 185 but such drugs are likely years away from clinical use.

Therapeutic strategies against KRAS mutant cancers that have been investigated clinically include inhibition of post-translational modification, inhibition of effector pathways, and synthetic lethality.

8.5 Post-translational modification

To date, this strategy has had little clinical efficacy. Farnesyl transferase inhibitors (FTIs) have failed to inhibit KRAS due to alternative prenylation by geranylgeranyl transferase. (GGTase).186 Combined FTI and GGTase inhibitor therapy has been associated with excessive toxicity.187

8.6 Effector pathway inhibition

Several clinical trials have evaluated MEK inhibition alone or in combination with other therapies for KRAS mutant lung cancer. In a phase 2 clinical trial of docetaxel ± the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244; AstraZeneca) for previously treated advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC, selumetinib was associated with improved PFS (5.3 v 2.1 mos; 80% CI, 0.42–0.79; P=0.14) and a trend toward improved OS (9.4 v 5.2 mos; 80% CI, 0.56–1.4; P=0.21).15 Another phase 2 trial randomizing patients to selumetinib alone or in combination with erlotinib has completed enrollment (NCT01229150). Other MEK inhibitors under study specifically in KRAS mutant NSCLC include MEK162 (Novartis) combined with erlotinib (NCT01859026) and trametinib (GSK1120212, GlaxoSmithKline) monotherapy (NCT01362296).

A possible benefit of BRAF inhibition in KRAS mutant NSCLC was suggested in the BATTLE (Biomarker-integrated Approaches of Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Elimination) trial. In that study, 11/14 (79%) patients with KRAS/BRAF mutations had disease control at 8 weeks with sorafenib.188 However, in preclinical models, BRAF inhibitors appear ineffective against RAS mutant cells, paradoxically potentiating RAF/MeK/ERK signaling.189 This phenomenon, which has been attributed to CRAF activation, is evident clinically in the development of KRAS mutant cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in melanoma patients treated with BRAF inhibitors.190, 191

A number of recent and ongoing clinical trials have focused on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade. Specific agents under investigation in KRAS mutant NSCLC include the mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus (IPI-504; Infinity Pharmaceuticals) (NCT00818675), the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in combination with the HSP90 inhibitor retaspimycin (NCT01427946), everolimus in combination with trametinib (NCT00955773), and the dual PI3K-mTOR inhibitor BEZ235 (Novartis) in combination with MEK162 (Novartis) (NCT01337765, NCT01363232).

The RHOA-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) axis has emerged as a critical mediator of RAS signal transduction. In transgenic and orthotopic mouse models of KRAS mutant lung adenocarcinoma, FAK inhibition resulted in inhibition of tumor growth and prolongation of survival,192 leading to an ongoing multicenter phase 2 trial of the FAK inhibitor defactenib (VS-6063; Verastem) in previously treated advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC (NCT01951690).

In a randomized phase 2 clinical of erlotinib ± the c-MET inhibitor tivantinib (ARQ-197; ArQule), an exploratory analysis revealed that the small cohort with KRAS mutations achieved a PFS HR of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.05–0.70).193 This benefit was hypothesized to be related to a putative feedback loop through which EGFR acts as a downstream mediator of KRAS signaling, interactions between hepatocyte growth factor (the MET ligand) and KRAS, or non-MET mediated pathways. A subsequent randomized phase 2 clinical trial of erlotinib + ARQ-197 versus single-agent chemotherapy in previously treated advanced KRAS mutant NSCLC (NCT0139578) has completed accrual.

8.7 Synthetic lethality

With synthetic lethality, KRAS-mutant cancer cells are selectively killed via inhibition of a second protein. In KRAS mutant cell lines, RNAi-based synthetic lethal screens have identified several potential targets. A number of these, including CDK4, STK33, TBK1, and PLK1, encode protein kinases and may therefore be amenable to small molecule inhibition.194

9. NSCLC WITH PI3K PATHWAY ALTERATIONS

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling plays important roles in metabolism, growth, survival, and motility. The Class IA PI3Ks are most clearly associated with human cancer and are activated by growth factor stimulation through receptor tyrosine kinases. Class IA PI3Ks are composed of a regulatory subunit and catalytic subunit. The regulatory subunit, p85, is encoded by PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3, while the catalytic subunit has three isoforms, p110α, p110β, p110δ, encoded by PIK3CA, PIK3CB, and PIK3D. Binding of p85 to phosphotyrosine residues on receptor tyrosine kinases releases the inhibition of p110 by p85 and causes localization of PI3K to the plasma membrane, where it can phosphorylate PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) to produce PIP3 which in turn propagates intracellular signaling via AKT and PDK1 and other PIP3 dependent signaling pathways. Phosphatase and tensin homology deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2, thus inhibiting PI3K-dependent signaling and acting as a tumor suppressor. PI3K can also be activated by RAS or by G-protein coupled receptors which bind directly to the catalytic subunit. PI3K-AKT signaling regulates multiple downstream pathways including the bcl2 family members, forkhead transcription factors, MDM2/p53, mTORC1/2, and NFKB pathways, to promote cell survival and inhibit apoptosis.195–197

9.1 Genetic Alterations in PI3K pathway

Genetic alterations of elements in the PI3K pathway have been described in lung cancer as well as other tumor types. PIK3CA encodes the gene for the p110α isoform of the catalytic subunit ofPI3K. Both copy number gains and mutations in PIK3CA have been identified in lung cancer. PIK3CA copy number gains occur in approximately 20% of lung cancers, with higher frequency in squamous cell carcinomas.198–200 Somatic mutations in PIK3CA have also been described and promote activation of the PI3K signaling pathway.201 Mutations in PIK3CA are clustered in two hotspot regions in exons 9 and 20 encoding the helical and kinase domains of the protein, respectively. These mutations lead to increased lipid kinase activity and constitutive PI3K-AKT signaling.201 The mechanism of action is different based on mutation type; for example, the helical domain mutants E545K and E542K interfere with the inhibitory interaction between the regulatory subunit p85 and the catalytic unit p110α, while the kinase domain mutant H1047R is located near the activation loop and leads to constitutive signaling through the kinase.195 PIK3CA mutations have been reported in 1–5% of NSCLC cell lines and tumors.198, 202 Kawano et al202 found PIK3CA mutations in 6.5 % of lung squamous cell carcinomas, and less often in lung adenocarcinomas (1.5%). PIK3CA mutations often do not exist in isolation, and coexistence with other mutations, such as KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and EGFR, is common.203–205 A study among patients with lung adenocarcinoma in the U.S. reported 70% of cases with PIK3CA mutation had a coexisting driver mutation, with the most frequent partner being KRAS.205

The tumor suppressor gene PTEN encodes a lipid phosphatase that negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT pathway, and loss of PTEN leads to constitutive PI3K-AKT signaling. Somatic PTEN deletions and mutations, and inactivation of PTEN by epigenetic mechanisms such as methylation or microRNA silencing, are seen in multiple cancers.206 PTEN mutations occur in approximately 5% of lung cancers and are significantly associated with squamous cell rather than adenocarcinoma histology (10.2% v 1.7%).207 Reduction or loss of PTEN expression has been reported in up to 70% of non-small cell lung cancer, both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell.208

Other mutations in elements of the PI3K pathway have also been reported. For example, a somatic mutation in AKT, E17K, constitutively activates the protein kinase.209 The AKT1 E17K mutation was found in 5.5% (2/36) squamous cell lung cancers, but not (0/53) in lung adenocarcinoma.210 PIK3R1 mutations causing truncations or in-frame deletions have also been reported and are thought to relieve the inhibitory effect of p85 on p110, thereby activating PI3K signaling.

9.2 Drug Development

There are multiple PI3K inhibitors in development, with specificity ranging from pan-PI3K inhibitors to isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors and dual PI3K/MTOR inhibitors. As a class, common adverse events have been hyperglycemia (which is thought to be due to the role PI3K plays in the insulin signaling pathway), maculopapular rash, and gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and stomatitis. In addition to the phase 1 studies of PI3K inhibitors that enrolled all tumor types, there are many ongoing trials with a focus on lung cancer, both as monotherapy and in combination with other agents. There have been multiple Phase 1/1b studies combining various PI3K inhibitors with MEK inhibitors which have enrolled expansion cohorts of patients with KRAS mutated lung cancer; efficacy results from these trials are awaited. In non-molecularly selected lung cancer populations, currently ongoing trials include GDC0941 in combination with carboplatin, paclitaxel, with or without bevacizumab, and BKM120 in combination with docetaxel or carboplatin/pemetrexed. BKM120 is also being tested singly and in combination with EGFR inhibitors in molecularly selected cohorts. GDC0032 is also being tested in combination with chemotherapy agents including docetaxel and paclitaxel.