Abstract

Medical providers are trained to investigate, diagnose, and treat cancer. Their primary goal is to maximize the chances of curing the patient, with less training provided on palliative care concepts and the unique developmental needs inherent in this population. Early, systematic integration of palliative care into standard oncology practice represents a valuable, imperative approach to improving the overall cancer experience for adolescents and young adults (AYAs). The importance of competent, confident, and compassionate providers for AYAs warrants the development of effective educational strategies for teaching AYA palliative care. Just as palliative care should be integrated early in the disease trajectory of AYA patients, palliative care training should be integrated early in professional development of trainees. As the AYA age spectrum represents sequential transitions through developmental stages, trainees experience changes in their learning needs during their progression through sequential phases of training. This article reviews unique epidemiologic, developmental, and psychosocial factors that make the provision of palliative care especially challenging in AYAs. A conceptual framework is provided for AYA palliative care education. Critical instructional strategies including experiential learning, group didactic opportunity, shared learning among care disciplines, bereaved family members as educators, and online learning are reviewed. Educational issues for provider training are addressed from the perspective of the trainer, trainee, and AYA. Goals and objectives for an AYA palliative care cancer rotation are presented. Guidance is also provided on ways to support an AYA's quality of life as end of life nears.

Keywords: palliative care, education, training, adolescent, young adult

Introduction

Providing quality comprehensive care to adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer is an often complex and challenging, yet always meaningful task. Their medical providers are trained to investigate, diagnose, and treat cancer. Their primary goal is to maximize the chances of curing the patient, with less training provided on palliative care concepts and the unique developmental needs inherent in this population. Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life (QOL) for AYA patients and their families by controlling symptoms and alleviating physical, social, psychological, and spiritual suffering.1 However, palliative care is often not considered until curative treatment options are no longer available. As pain and symptom management is needed with varying intensity at different stages of disease, integration of palliative care at the time of diagnosis enables a supportive partnership with the medical team, with palliative care needs intensifying as the disease progresses. Early, systematic integration of palliative care into standard oncology practice represents a valuable, imperative approach to improving the overall cancer experience for AYAs.1 Just as palliative care should be integrated early in the disease trajectory of AYA patients, palliative care training should be integrated early in the professional development of trainees. The term “palliative care” is derived from the Latin word “palliare”, meaning “to cloak”. Sewing palliative care training in as a thread of technical skills in the preclinical years would tie nicely to bedside guidance during the clinical years, enabling didactic and experiential learning to be cohesively woven together. This article reviews unique epidemiologic, developmental, and psychosocial factors that make the provision of palliative care especially challenging in AYAs. Critical instructional strategies and educational issues for provider training are addressed from the perspective of the trainer, trainee, and AYA.

Epidemiology

An estimated 70,000 AYAs are diagnosed with cancer each year in the US.2 This group is treated across both pediatric and adult settings, and often lacks a focused group of health-care experts who address the unique changes in the types of cancer and subsequent responses to prescribed therapies.3–5 New cancers emerge in this group, which are relatively rare in younger patients. Such cancers include malignant epithelial neoplasms (eg, thyroid carcinoma, malignant melanoma)6,7 and malignancies involving reproductive organs (eg, testicular cancer, uterine, cervical, and breast cancer), which increase dramatically in this age group. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia exhibits less favorable cytogenics with a higher incidence of Philadelphia-positive chromosome and, overall, a worse prognosis than in younger children.8 The incidence of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) increases in late adolescence and emerging adulthood with a less favorable prognosis.8 Unfortunately, the overall survival rate for AYAs has not kept pace with individuals diagnosed with cancer under age 15 or over age 40.9 Furthermore, the 10- and 20-year survival rates dramatically decrease in AYAs. For example, the 20-year survival rate for individuals 15–29 years old diagnosed with AML is only 20%–27%.8

It has been nearly a decade since AYA disparities were initially reported.5 Disparities seen in this population have been linked to a number of factors including delays in diagnosis,10 ineffective access to care,11 lack of health insurance,10,12 lack of participation in clinical trials,13–15 inconsistent registration and/or classification of AYA cancers,16 inconsistent treatment and follow-up,17–20 problems with treatment adherence,21,22 and changes in AYA cancer biology,3 and AYA pharmacokinetics.4 It is increasingly evident that creative training is needed to address the disparities of this unique age group.

The need

A call for palliative care education to improve AYA care

Recent research has demonstrated improved number of days and QOL for adults referred early to palliative care practitioners.23,24 In response, the American Society of Clinical Oncology has developed a provisional clinical opinion stating that concurrent palliative care and standard cancer care should be considered early in the course of illness for patients with metastatic cancer or cancer with high symptom burden.25 Although the American Academy of Pediatrics also supports the integration of palliative components at diagnosis for patients aged 0–25 years regardless of the outcome (cure or death),26 the integration of palliative care for AYAs in clinical practice remains low.27

Quality cancer care for AYAs depends on access to palliative care professionals who are knowledgeable about the unique biomedical, psychosocial, and developmental needs of this population throughout the disease trajectory.28 In fact, AYAs living with cancer report that the “availability of health providers who know about treating young adults with cancer” is problematic, and rate this as the second most important care need.29 Similarly, more than half of subspecialty resident graduates find training in adolescent medicine inadequate for clinical practice.30,31 Furthermore, more than half of graduating medical students feel ill prepared for endof-life (EOL) interactions,32 which is not surprising given that the average medical school curriculum contains limited hours of formal palliative care training.33 Similar gaps in palliative care education are seen in physician-assistant and nurse practitioner programs. As a result of limited palliative training backgrounds and current curative-directed cultures, clinicians may be delivering cancer-directed care to AYAs with a low level of perceived competence or knowledge in the area of palliative care. The limited education provided in this area to future providers may reduce their sense of expertise,34 thereby making it difficult to comfortably approach the palliative care topic with patients and in turn reduce the patient/family benefit from these services. Although training programs for both adult and pediatric palliative care are expanding, training in AYA palliative care falls in a void between the adult and pediatric training domains. Medical trainees recognize the existence of a “hidden curriculum” in which the psychosocial processes of terminal illnesses and dying may be underaddressed and minimized rather than explicitly taught as educational objectives.35 Recognition of inadequate formal palliative training programs warrants urgent attention to early integration of palliative care as part of professional training.

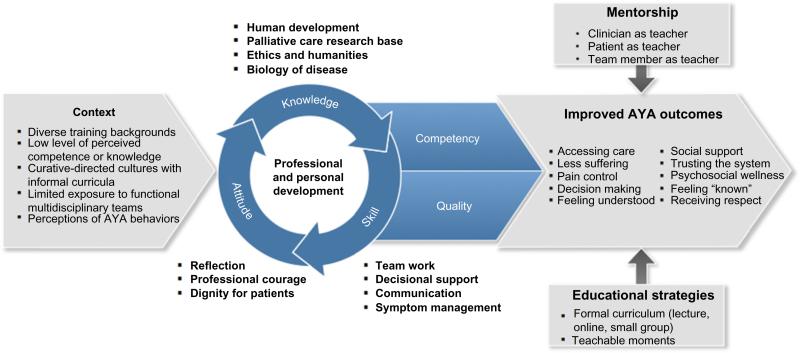

Inadequate education for clinicians, that is, one that does not “fit” the clinical and academic milieu of care, is a barrier to effective integration. An educational and conceptual model that recognizes contextual barriers, addresses the personal and professional development of learners, and teaches palliative care concepts in a strategic way has the potential to best improve AYA outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for adolescent and young adult palliative care education.

Abbreviation: AYA, adolescent and young adult.

The challenge

Who are AYAs? Developmental considerations

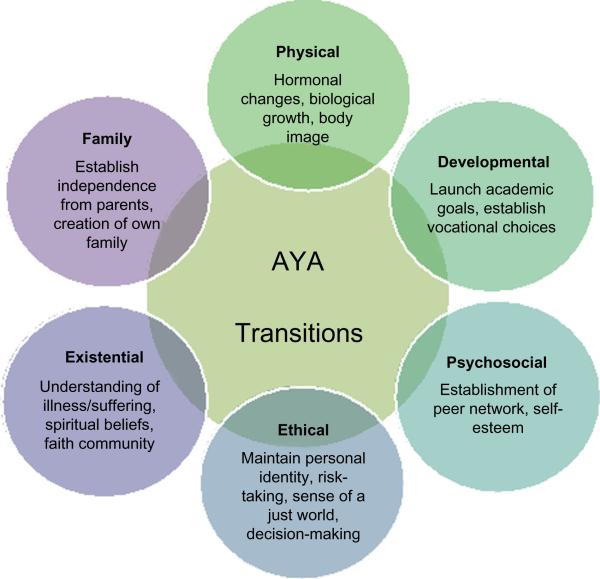

The priorities of palliative care are similar for AYAs and adults: ongoing assessment of goals of care, provision of expert pain/symptom assessment and management, appraisal of spiritual and emotional needs, sensitive communication (including advance care planning), and family bereavement care.36 However, the developmental, psychosocial, ethical, and existential differences in life stage of AYAs warrant specific training for palliative care clinicians (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Supporting quality of life at end of life: developmental considerations.

Abbreviation: AYA, adolescent and young adult.

The term “AYA” is not consistently defined.1 The AYA Oncology Progress Review Group refers to patients aged 15–39 years at the time of initial cancer diagnosis.5 The AYA age spans the gap between pediatric and adult health-care providers and centers.28 It also spans the developmental trajectory, and thus, health providers benefit from familiarity with normative development.37 For example, AYAs’ physical development may be delayed or expedited by the cancer diagnoses, depending on nutrition status, hormonal balance, and treatment influence. Emotional development may be altered in negative ways, such as learned decisional passivity because of overprotective parenting or social anxiety due to extended social isolation or a shrinkage in social network.38 Similarly, AYA patients may existentially mature faster than anticipated or reveal a premature wisdom from posttraumatic growth.39 Insight into behavior such as nonadherence to medication, risk-taking, or questioning of authority within the context of AYA identity can help in trainee interactions with AYAs.40 Younger AYAs often have a sense of immortality, which is sometimes reflected in their inconsistent treatment compliance.41 Younger AYAs may also engage in risky activities during treatment (eg, consumption of alcohol), often in an attempt to fit in with peers and counter feelings of rejection.42 Table 1 provides a developmentally informed perspective on supporting QOL at EOL with informed consideration of AYA developmental needs. As AYAs with cancer brave developmental transitions, so their clinicians should brave growing in knowledge of palliative care to transition toward earlier integration that is developmentally appropriate.

Table 1.

Supporting quality of life at end of life

| Issue #1 AYAs may still be able to engage in their usual activities such as work, study, and socializing. |

| Developmental factors |

| • Independence, autonomy, and social/peer networks are likely to increase determination to engage actively in these aspects of their life, even as their disease progresses. |

| Interventions |

| • Support AYAs to continue to engage in their usual activities as much as possible. |

| • Prioritize QOL concerns. This may require the provision of palliative medical treatment (eg, chemotherapy) to be delivered with an element of flexibility, involving “innovative therapeutic compromises,” where possible.64 For example, AYAs may wish to negotiate their attendance at hospital around important events like birthday parties, graduations, proms, and other important life events. |

| Trainee considerations |

| • Enabling continuation with usual activities may require trainees to alter any preconceived expectations they may have regarding “how” a patient “should” be spending their time as end of life nears. |

| Issue #2 AYAs’ wishes/requests (eg, attending sports events, going out to clubs, other forms of developmentally normative risk-taking) may conflict with medical opinion/advice. |

| Developmental factors |

| • This should not be interpreted as necessarily reflective of the young person being “in denial” regarding their disease status and physical vulnerability. |

| • AYAs tend to “yo-yo” between acceptance and preparation for death (eg, planning whom to give their belongings to), and what may appear like outright “denial” (eg, planning to move out of home, thinking about college). While some difficulty processing the reality of their own death and “mortality” may be developmentally normal,64 this “dual process” manner of reconciling one's self to great loss and grief is also seen across the life span.108,109 |

| • Contributing to society, forging an “identity,” and being remembered are developmental imperatives for AYAs.29 Being able to engage in behaviors/activities consistent with the AYAs’ sense of self/identity is likely to improve QOL during this stage. |

| Interventions |

| • Open, gentle conversations around the AYA's wishes can help explore how the AYA understands their current situation, and identify what is important and meaningful to them. Conversations can be guided by advance care planning guides, so that these important choices are documented.74 |

| • Assist AYAs to reconfigure their goals, focus on shorter-term activities that are still consistent with their values, and contribute to their sense of self-esteem and hope.110 |

| Trainee considerations |

| • Consider how important it is to feel as if your life “matters.” Think about Phase I trials in terms of the AYAs’ psychological needs as well as treatment outcomes. The crucial psychological need to be remembered and “to have mattered,” combined with AYAs’ altruism as a group, means that participating in research and clinical trials may form a part of legacy making for many AYAs.111,112 |

Abbreviations: AYAs, adolescents and young adults; QOL, quality of life.

Training interventions: instructional strategies

Essential components of AYA palliative care education include longitudinal access, reflection, mentorship, and purposeful teaching strategies. Longitudinal exposure enables trainees to follow a patient with a sense of personal responsibility, witness changing psychosocial dynamics, and engage in committed partnership.43 Personal reflection and team debriefings assure acquisition of professional assiduousness and emotional coping.44 Mentors who adopt “teachable moments” at the bedside enable trainees to witness skills and shared vulnerabilities in a real environment.45,46 Deliberate provision of written goals and real-time guides for palliative care trainees could legitimize topics as valid educational points. Teaching palliative domains requires variability within programs. For example, knowledge areas such as opioid conversion may be taught in calculation tutorials, whereas attitudinal areas such as truth-telling require theoretical teaching with mentored clinical exposure.47,48 In the setting of minimal protected curricular time and a shortage of palliative care providers, intentional exposure to diverse teaching modalities equips instructors with practical teaching tools and enables learners with an accessible knowledge base (Table 2). The reality of palliative care as a young and an understaffed field has led to the prioritization of educating trainees as palliative care champions to share their knowledge in local settings.

Table 2.

Instructional strategies

| Strengths | Challenges | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiential learning | Training experience in real-life settings or simulated bedside formats has potential to enhance real-life work | • Requires time during busy clinical/inpatient days | Simulated patient/video playback; structured home visits; mentored hospice visits; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center's Comskills |

| • Requires availability of qualified local providers | |||

| Group didactic opportunities | Foundational peer settings allow shared insight and learning experiences with one another (social and cognitive congruence) | • Requires curricular commitment of training center | Small-group EOL communication training sessions; palliative care rotations with peer discussion groups |

| Shared learning among care disciplines | Helps learners envision patient's experience within context of multiple needs; teaches learners to develop patient strategies for utilizing wide array of resources/support | • Requires availability of multidisciplinary team representation | Joint consultations; family meetings with multiple care teams present; interdisciplinary grand rounds; clinical teaching conferences |

| Bereaved family members as educators | Provides unique perspective as family members share “lived experience” to facilitate palliative care discussions | • Requires special attentiveness to minimize emotional burden to bereaved family member | Bereaved parent panels at conferences; single sessions with bereaved family members and limited staff members; bereavement reunions hosted by hospitals |

| EOL training programs | Enables access to a structured, modular curriculum with teaching grounded in evidence base | • Requires funding for programmatic development | American Association of Colleges of Nursing ELNEC train-the-trainer program; Integrating Palliative Oncology Care into DNP Education and Clinical Practice; EPEC program; Center to Advance Palliative Care leadership training; and global examples from Portuguese Catholic University, University of Cape Town, and Mildmay Program in Uganda |

| • Requires protected time for learners | |||

| Online learning | Expands access through flexible teaching formats, protects participants’ travel resources, allows learners to receive training at their own pace and location, adapts to a “social media” learning generation | • Requires access to Internet technology; ideally fosters ways for technology to translate into mentored patient care opportunities | International Children's Palliative Care Network's free eLearning modules |

| Learner networks | Expands trainee learning opportunities, networks, and collaborations, while minimizing programmatic redundancies | • Often requires access to blogging, document and resource sharing, eGroups, and listservs | Regional SIG; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization member-exclusive professional community; collaborative journal clubs; joint case study teaching seminars |

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ELNEC, End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium; DNP, Doctor of Nursing Practice; EPEC, Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care; SIG, Special Interest Groups.

Experiential learning

Establishing and maintaining a therapeutic alliance with an AYA requires attentiveness to the content and quality of communication, an approach most effectively realized through in-person training. A survey of clerkship directors revealed that lectures and small-group discussions were the most common palliative training modalities.49 However, residents and directors of pediatric residency programs have reported palliative care learning was best accomplished at the bedside (close to an actual encounter) and during rounds as experiential learning opportunities.45 Structured home visits and hospice rotations within palliative care curricula would enhance personal and professional trainee development.50

Didactic and day-to-day training opportunities

Medical students receiving formal didactic and day-to-day EOL training report being more comfortable with palliative care and have an improved knowledge base with measurably increased competence in delivering palliative care.51,52 Posttest assessments reveal that even short-duration interventions, such as a 2-week palliative care rotation for residents, lead to knowledge improvement.53 An ongoing question is whether empathy is innate and the role communication skills have in improving empathic care. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), residents’ communication skills and responses to patients’ emotions improved significantly after a 1-day EOL communication skills retreat.54 In an RCT, testing whether an empathy protocol could improve physician empathy, residents receiving the training modules were rated as more understanding, compassionate, and caring by patient reviewers than those not receiving the empathy modules.55 Inexpensive discussion-based seminar series can successfully provide pediatric residents with foundational information on EOL care and considerably increase their confidence when caring for seriously ill or dying patients.56 Peer-training formats recognize students share “cognitive and social congruence”, which may bridge generational gaps.57

Shared learning opportunities

To build a truly collaborative relationship, it is important for AYA care clinicians to engage with the palliative care team through a joint consultation with a member of the palliative care team or through periodic joint patient visits.58 These joint sessions model for trainees a practical way to ensure AYAs and families receive a strong message that the primary oncologist is not abandoning them, but rather that they are participating in providing comprehensive support within an interdisciplinary format.

Bereaved family members as educators

Bereaved parents have been utilized in educating health-care professionals in several settings, including being a part of a parent panel at conferences, or participating in facilitated, small-group discussions with staff.56,59–62 While most family members have been parents who have experienced the death of a child, grandparents and siblings have also participated. A study examining a program that utilized bereaved parents in an 8-week luncheon training series for health-care providers was evaluated to study motivations, expectations, challenges, benefits, and meaning-making.62 During the sessions, parents took an active role in the facilitated discussions surrounding topics relating to communication, family support, EOL support and care, and death. While the study sample was limited to one site, health-care professionals identified more benefits than burdens from bereaved parents’ participation in the care trainings.

Online learning

Strategies for palliative care teaching have included web-based learning modules.63 Since everyone cannot attend annual conferences, online immersive learning is an increasingly feasible option for expanding access through flexible teaching formats. Distance learning protects participants’ resources and allows them to receive training at their own pace and location. Online teaching formats recognize the technological strengths of this “social media” generation of learners by partnering self-paced learning with collaborative conversations on live web platforms. Ideally, providers should be able to combine live training interactions with distance-learning modules to translate knowledge obtained via technology into real-time patient care.

Networking

Professional communities provide the opportunity to connect, care, and share experiences specific to palliative care. National and regional palliative care special interest groups are increasing in prevalence and presence. Shared educational formats across institutions, such as collaborative journal clubs and case study teaching seminars, expand trainee learning opportunities, models collaboration, and minimize programmatic redundancies.

Educational domains – a triple-perspective

In training clinicians to provide more appropriate and integrated care for AYAs, eliciting trainee, trainer, and patient perspectives on valuable teaching content provides multi-viewpoint insight into essential education domains. Table 3 presents an overview of trainee, trainer, and patient learning priorities, and Table 4 provides an example of goals and objectives.

Table 3.

Trainee, trainer, and patient perspectives on AYA palliative care training/learning priorities

| Theme | Learner perspective |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trainee | Trainer | AYA patient | |

| Collaboration, roles, and models of care | The multidisciplinary team | Roles/boundaries | Flexibility and continuity of care |

| • Expose trainees to true collaboration modeled across fields.113 | • Observe trainees’ interactions with AYAs (intensity of interactions and relationships with AYA patients). | • Identify key “advocates” or “clinical champions” (eg, doctor, outreach clinical nurse, social worker, psychologist, child life specialist) critical to gold-standard care for AYAs. | |

| • Allocate time for learning perspectives and viewpoints of each team member. | • Monitor trainee for possibility of confronting own mortality due to similarity in age to AYA. | ||

| • Identify ways to include available experts for truly comprehensive AYA care.114 | • Mentor trainees in areas of role definition, professional boundaries, and transference. | • Maintain continuity of care with staff who know AYA and family well. | |

| • Tailor care to AYAs’ individual needs and concerns. | |||

| • Due to strong relationships that may develop, AYAs may be more vulnerable than patients of other ages to become distressed by staff/attending rotations. | |||

| Communication issues | Effective communication | Prognostic honesty | Introducing palliative care as an added support |

| • Present information about AYA diagnosis and treatments in a direct, age-appropriate, and comprehensible manner.69 | • Model honest conversations with AYAs around their illness.73 | • Introduce the palliative team in a way that implies neither giving up on nor abandoning the patient, but simply adding support.115 | |

| • Allow AYA adequate time to process their poor prognosis83 for greatest chance of resilience and “posttraumatic growth.” | |||

| • Investigate reliable, age-appropriate Web sources and online support groups. | • Educate trainees working with team to plan future care with options for EOL care planning. | • Words such as “We will continue to do everything possible to help treat your cancer. Our palliative care colleagues can work with us to make sure your symptoms are under good control and that you and your family are getting an extra layer of support” can be useful in communicating with AYAs.116 | |

| • Develop longitudinal relationships with AYAs to further learn about communication behaviors of their family and cultural influences on communication patterns. | • Support AYAs and their families to take control of the situation in whatever ways they find useful as a family. | ||

| • Encourage AYA and family to communicate around EOL issues (eg, death/dying, last wishes) “just in case” the cure they hope for does not eventuate. | |||

| • Conceptualize palliative care as a consistent, congruent part of the care paradigm, in order that transition to comfort care can have a gradual and intuitive presence rather than a jolting introduction.117 | |||

| • Due to strong relationships that may develop, AYAs may be more vulnerable than patients of other ages to become distressed by staff/attending rotations. | |||

| • The use of the word “cure” may lead to misunderstandings, particularly if patients and families selectively focus on that term, rather than other contextual information surrounding it. | |||

| • Phase 1 trials should be discussed and offered whenever possible. As even very unwell AYAs can show great altruism, and value the opportunity to participate in research, Phase 1 studies may be framed as a means of “giving back” or contributing to medical science so that future generations of AYAs with cancer may benefit.111,112 Given that even adult patients can perceive pressure from family members to participate in such trials,118 in younger, more vulnerable AYAs, it is critical that this decision-making process allows the AYA to discuss their options in detail with a clinician without their parents/family present, if desired. | |||

| Decision-making/disclosure | Decision-making/disclosure | Decision-making/disclosure | |

| • Incorporate EOL conversations as disease progresses to facilitate preparedness. | • Even when there is reassuring disease response to therapy or “good news” on imaging, encourage trainees to consider the “what ifs” with AYA patients to ensure goal-directed conversations are integrated early. | • Allow the AYA patient to decide who is or is not present for decision-making conversations. | |

| • Include training in early advanced care planning (supporting conversations important to AYA patients,116 such as place of death75 and how the patient wishes to be remembered73). | • Check in with AYA patients to determine best timing for decision-making conversations; provide advance warning early in the conversation that the content may be heavy or hard, and receive permission from the AYA patient to proceed with conversation at that time. | ||

| • Familiarize trainees with the social dimensions unique to each family for placement of AYA EOL care needs in the wider evidence base of palliative science. | |||

| • Ensure decisions and anticipated outcomes from decision options are communicated in a clear, honest, and compassionate manner. | |||

| • Present treatment options allowing sufficient opportunity for AYAs to express individual preferences for continued treatment or advance care planning. | |||

| Managing physical symptoms and psychological distress | Symptom management | Coping with loss | Assessing and managing psychological distress |

| • To respect the request of AYAs for transparency and information sharing,119 trainees should be well informed about each medication and its potential side effects in order to ensure clear communication before adjusting medications. | • Insufficient preparation, training, and competence in physical and psychosocial symptom management and communication skills can negatively affect the way providers manage a patient's death. | • The prevalence of psychological distress among AYAs with cancer varies over time after diagnosis but not by the type of cancer or the prognosis.120 | |

| • AYAs may feel burdened by the emotional responses of friends and family members, and those who have a family of their own may feel guilty about how disruptive and psychologically challenging the diagnosis can be for their partner or children. | |||

| • The trainee should be familiar with validated symptom reporting scales and skilled in recognizing symptoms. | |||

| • AYAs may also have a lower “mental health literacy” relative to older adults – that is, a less sophisticated understanding of types of psychological distress and how to recognize this in themselves and others.121 Consequently, it may be helpful to talk to the young person about the different types of distress common across the cancer trajectory, including within the EOL phase, such as anticipatory grief, separation anxiety, social/peer concerns, and worry about family and friends dealing with their death. | |||

| • AYAs’ developmentally normal concern around peers and body image may also lead to concerns around their physical appearance as their disease progresses and after death. The use of age-appropriate advance care planning guides can assist the AYA by providing a very specific, concrete “scaffolding” in which to discuss EOL concerns.74 | |||

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adult; EOL, end of life.

Table 4.

Learner goals and objectives for an AYA palliative care cancer rotation

| Goals | Objectives |

|---|---|

| Development | Describe the typical sequence of events in cognitive and psychosocial development from early adolescence through young adulthood |

| Describe physiologic changes normal for this population with recognition of developmental delay or early maturity | |

| Recognize discordant timing and tempo of psychosocial development (including formation of identity) secondary to cancer | |

| Describe protective factors that promote AYA development and describe risk factors for potential delay in AYA development | |

| Understand the normal range of AYA stress and the additional stress chronic illness imposes | |

| Evaluate the impact of cancer on developmental goals | |

| Decision-making and disclosure | Support the AYA in discovery of his/her core values and cultivate insight into self-awareness for AYA and family |

| Present options, consequences of options, and how personal/family values may be enabled in choices | |

| Consider the ethical principles involved in decision-making and disclosure | |

| Investigate how different cultural or religious backgrounds may impact decision-making or disclosure | |

| Determine AYA patient's decisional control preference (keep, share, defer) and preferences for inclusion in decision-making conversations (self, parents, peers, siblings, certain clinicians, team members) | |

| Provide opportunities for decision-making, beginning with simple choices toward greater complexity | |

| Encourage family to enable and support AYA decision-making | |

| Host advanced care planning meeting with the adolescent and his/her chosen proxy | |

| Support the AYA in discovery of his/her core values, and cultivate insight into self-awareness for AYA and family | |

| Symptom management | Assess for nausea and pain with plan for monitoring trends in medication use |

| Assess level of sedation | |

| Screen for sleep disorders such as insomnia or bad dreams that may be indicative of underlying emotional/existential distress | |

| Provide AYA and family with clear explanation of medication options and potential side effects as well as drug-alcohol interactions | |

| Communicate any medication changes with AYA | |

| Effective communication | Learn about AYA's information and communication preferences, and discuss role for communication proxy |

| Provide developmentally informed, direct, honest, compassionate communication approach | |

| Provide explanation of confidentiality, and ask for permission to share information with family members prior to sharing information | |

| Promote communication between AYA and his/her support network to the preferences of the AYA | |

| Discuss supportive goals for adherence and supportive needs and resources for enablement of treatment adherence and appointment attendance | |

| Psychosocial issues | Assess factors in AYA's home, school, religious center, and community that are associated with potentially helpful or harmful outcomes |

| Inquire about AYA and family school/vocational trajectories | |

| Discuss with AYA the support available as structural models (social networks) and functional models (perception of quality of relationships) | |

| Monitor changes in social environment, and assess these changes within the context of the AYA's strengths and vulnerabilities | |

| Provide family members with information about psychosocial support and counseling | |

| Supportive care | Provide AYAs with anticipatory guidance regarding nutrition and physical activity |

| Provide and incorporate family support for balanced nutrition and physical activity. Ensure nutritional advice and physical activity guidance are shared with the AYA and their family. | |

| Inquire about preferences for complemenary and alternative medicine | |

| Ask about drug and alcohol use, and provide appropriate counseling and referral as needed | |

| Existential | Inquire about spiritual or religious beliefs in a patient-sensitive manner |

| Refer AYAs who express existential struggle to resources or activities relevant to the AYA's personal preferences | |

| Peer support | Maintain a list of AYA online and in-person support groups and recreational programs |

| Evaluate changes in peer support, and offer ways to maintain healthy relationships | |

| Mental health | Screen for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk with appropriate management plans for AYA with mental health problems and mental health referral |

| Incorporate inquiries about sadness and fear into normal conversations with AYAs | |

| Reproductive health | Discuss intimacy, sexual development, and sexual identity |

| Discuss ways to be intimate aside from sexual intercourse | |

| Inquire about behaviors associated with the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, and provide patients with health guidance regarding sexual decision-making | |

| Consider topics of fertility, contraception, and adoption, and issues related to sexual dysfunction | |

| Genetic | Familiarize with resources on constitutional genetic syndromes and inherited cancer risk |

| Financial | Link to financial resources and legal resources/advocates for coverage for AYAs, as needed |

| Refer to transportation assistance programs, as needed | |

| Familiarize with health insurance policy coverage, and recognize gaps in coverage | |

| Learn about the transition for AYAs to separate insurance policy from parental policy | |

| Investigate the financial aspects of hospice qualification and enrollment | |

| Multidisciplinary care context | Explain the professional role of each palliative care team member |

| Attend consultation with a team member from each field to learn more about the perspective of that field | |

| Make referrals to team members, and learn about the referral process/outcome | |

| Therapeutic alliance | Express value of AYA in all interactions and respect the AYA's dignity |

| Strive to support meeting important goals as defined by the AYA | |

| Help AYA's family and friends respect AYA's autonomy while remaining a supportive network | |

| Empower AYA with skills to effectively communicate their autonomy, wants, and needs with their family and friends |

Abbreviation: AYA, adolescent and young adult.

Trainee

Multidisciplinary team

The fields of adolescent medicine, oncology, and palliative care recognize that the best care of patients occurs in the context of multidisciplinary teams with expertise in biological, emotional, psychosocial, sexual, educational, developmental, and practical issues related to AYA patients.64 Although trainees may have spent time with experts from other disciplines, treatment often uses a “parallel play” approach, with each team member bringing his or her knowledge niche rather than engaging in a truly meaningful, interdisciplinary interaction. Trainees benefit from structured exposure to the unique vocabulary, diverse skill sets, and common vision brought together by diverse members of palliative teams. Exposure of trainees to problem solving within teams, including the task of working through tensions as a respectful and functional unit, provides trainees with a valuable career foundation.65

Effective communication

AYA patients value communication styles that are respectful, clear, and nonjudgmental.66 Information should be provided in a time frame that allows adequate time to process and rediscuss.67 Compassionate, sensitive, and honest communication can reduce AYAs’ anxiety and fear while offering support.68 Trainees of the millennial generation may have the opportunity to update the palliative care team on new modes of information delivery, as AYAs have expressed a preference for electronic information in addition to written information.69 Association with AYA patients over longitudinal time periods allows trainees to develop open, communicative relationships with them, which is essential both for building patient trust and for trainee development.

Decision-making and disclosure

Most AYA patients want to be involved in decision-making,67,70 although the preferred timing of these conversations needs to be individualized.71 In order to support AYAs decision-making needs, trainees benefit from attentiveness to family contexts. Some AYAs live with their families of origin, while others live with partners and their own children, and yet some AYAs live with their own children and their own parents, revealing the complex nature of roles and decisional contexts in this age group. The extent of involvement and responsibility AYAs desire may differ not only according to their emotional maturity, but also according to the nature of the decision. Additionally, although most AYA patients are competent at making complex, life and death decisions,71–75 some are more comfortable deferring medical decisions to their parents. Further, while many AYAs report wanting sole responsibility for smaller, day-to-day decisions, such as symptom management or whether to attend social events while on treatment, they may report being happy to share or even relinquish decisions for more critical medical decisions to their parents.70 These processes may also change as they become more unwell. Given these dynamic considerations, open conversations with the AYA about their parents’ role are essential, at multiple time points.

The involvement of AYAs in EOL conversations is often underdocumented, with the conversation occurring too close to death to allow AYAs time to prepare psychologically.76 Formal training in the ethics of autonomy, truthfulness, and respect for people allows palliative care trainees to consider the “when” of disclosure and involvement of AYA patients in care decisions rather than the “if ” of these interactions. Keeping abreast of research in palliative communication enables trainees to view intense, emotionally charged family dynamics through a scientific and social lens. For example, if an AYA's mother insists on nondisclosure of the progression of terminal disease to her adolescent son, a trainee's education on the ethical principle of truthfulness, bereaved parental regret when death was not discussed,77 and recognition of direct communication78 with an AYA equips the trainee to guide the family toward trust and truthfulness.

Symptom management

Many AYAs experience distressing symptoms during cancer treatment including at the EOL stage.76 The systematic assessment of symptoms and management of side effects are essential skills for trainees. New knowledge about pharmacokinetics4 presented via didactic lessons should be supplemented with individualized symptom management in which trainees are taught to monitor patterns of symptom reporting. AYA patients may underreport mental health symptoms in order to maintain a sense of normalcy,66 requiring trainees to have insight about specific psychological assessments and referrals. With the perceived loss of control secondary to cancer, AYAs benefit from choices and direct input on symptom management.

Trainer

Role clarification and professional boundaries

Trainees may require specific mentorship on ways to foster the trust of AYA patients and a sense of connectedness while supporting the patient's nonmedical social network and maintaining professional boundaries.79,80 Working with AYAs with cancer may bring a trainee's first confrontation with mortality, an experience intensified by the developmental vibrancy of this age group and by the practical reality that some trainees are the same age as AYA patients.

Prognostic honesty and communication

Although most AYAs do not raise the issue of prognosis with their parents or health-care team, this does not mean that thoughts and worries about life expectancy and disease progression are not active concerns for AYAs.81 Clinicians may be uncertain as to when and to whom to address issues related to prognosis. A study with AYA patients with stage IV/disseminated cancer found 76% of patients received medically intensive EOL care, despite their EOL care preferences not being known.82 Studies have reported that AYAs are interested in developmentally appropriate advance care planning,73,74 and other research has indicated that being given more time in which to process a poor prognosis increases the chances of resilience in the face of death.83 These findings suggest the need for clinicians to communicate honestly and early about prognosis, serving as communication role models for trainees.84 Less is known regarding what AYAs with advanced cancer find to be the most helpful language or terminology to use. Given that studies show that parents can continue to maintain hope for their child's survival, even after being told that their death is certain,85 it is also likely that the use of ambiguous language will increase misunderstandings in AYA patients. Training in this area needs to support health-care providers to navigate the delicate balance between supporting ongoing hope and being clear that cure is no longer possible.86,87

The best approach appears to be for health-care providers to follow the AYA's lead, and adopt an attitude of hope, where the hope is no longer focused on cure but on other wishes the AYA may have.1,74 This has been described as an “insurance policy”–type approach, where the AYA and their family may be encouraged to “hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.”88 In supporting this approach, it may be important to address the role of integrative medicine including complementary and alternative medicines (eg, acupuncture, Reiki, massage, music therapy), other nonmedical approaches (eg, organic diets, vitamin C injections, etc), and/or experimental treatments that AYAs and their families may seek out in the palliative phase. Trainees may benefit from mentored teaching that introduces these options while gently supporting the AYA/family's autonomy. Where Phase I clinical trials are an option, the potential QOL-related advantages and disadvantages should be discussed in an honest manner with AYAs, who may not realize that Phase I trials do not aim to cure them.89 Table 5 provides suggestions for ongoing prognostic communication.

Table 5.

Guide for ongoing honest prognostic communication with adolescents and young adults

| Prognostic discussions | When, How, With Whom |

|---|---|

| Building therapeutic alliance | When? |

| Therapeutic relationships are built on trust. Start today by setting the ground rules, defining your roles, and establishing your commitment to honesty. | |

| How? | |

| Examples | |

| • There will be times during the course of your cancer treatment that we will have to discuss some difficult things. | |

| • We will need to talk about treatment options. We may need to talk about changes in your condition. Your input is important to me. | |

| • If you don't understand something, I am relying on you to teach me how to help you better understand. | |

| • I will be honest with you and tell you as much as you want to know. | |

| With Whom? | |

| Give the AYA choices around the decision-making process, and let them know that there can be flexibility according to how they feel, and the decision at hand. | |

| • Some young people tell us that they like to be involved in all decisions, while some young people prefer someone else to decide things for them. How you feel might also depend on the decision: for example, you might like to make the final decision about whether to take antinausea medication, but you might prefer Mom/Dad to help you decide about continuing treatment. Involve support person | |

| • Who would you like to have included in ongoing conversations about your treatment and care? | |

| • [If over 18]: Even though legally you will be making this decision, it is important to us that we include important support people in your life in the process according to your wishes (eg, partner, spouse, best friend, parent) If relevant, address the issue of legal decision-making status. | |

| • In [country, eg, USA] young people are not legally able to take responsibility for medical decisions until they are 18 years. So we need to include your parents/caregivers in these important medical decisions by law until then. However, it is still really important to us that you have a say in these decisions, and that you are comfortable with the options we are talking about. I want you to let me know if you want to discuss the reasons behind a particular decision more at any point. | |

| • When you are X age, we will need to [reconsent/revisit these discussions or decisions] to make sure you are still in full agreement with this. | |

| Disease progression | When? |

| Each time there is no response to prescribed therapy, it is important to communicate disease progression honestly and in a manner that is timely and understandable. | |

| How? | |

| • Your latest scan (test results) shows that your cancer has continued to spread. There is another option we can try that may still be effective in curing your disease. I would like to explain the potential benefits and the potential risks that may happen with this next treatment (Phase II clinical trial, procedure, surgery, etc). | |

| With Whom? | |

| Prior to discussions, verify AYA's preference for involving support person(s). | |

| Palliative care options | When? |

| Introduce palliative care with diagnosis of a life-threatening disease, such as cancer. | |

| How? | |

| • We have a great team of experts who will help us manage any symptoms you may be experiencing as you go through your cancer treatment. We will work together to make sure your pain and other symptoms are under control. The palliative care team is also very helpful in addressing some of your fears or concerns that are a normal part of having a life-threatening diagnosis such as cancer. We consult with them at diagnosis, and they are an important ongoing part of the team. | |

| With Whom? | |

| Arrange for consult with palliative care team. | |

| Advance care planning | When? |

| Time points when the AYA's wishes and goals are discussed. These conversations are best had when the patient is relatively stable and not in a state of crisis.104,105 | |

| How? | |

| “While we will continue to provide treatments that we hope will be effective against your disease, we have learned from other people your age that not suggesting that you give some thought to some difficult issues early on is irresponsible of us. For example, do you know who you would like to make medical decisions for you if you became very ill and were not able to do so on your own?” In fact, people your age helped create a guide called Voicing My CHOiCES so that they could put down on paper things that are important to them. If you would like, I can show you what the document looks like to see if it is something that might be useful to you.” Conversations should be tailored to the needs of the individual AYA and family.104 | |

| With Whom? | |

| Whom ever the AYA chooses to participate in decision-making. | |

| Processing Grief and Emotions or Existential and Spiritual Struggles/Concerns | When? |

| Monitor during active treatment and as disease progresses. | |

| How? | |

| • I would like to know how you are doing emotionally. If at any time you feel uncomfortable or you don't want to talk about these things, just say, “I don't want to talk about it” – and we will move on. | |

| • What sorts of things are weighing heavily on your mind right now? | |

| • What are some of your greatest fears? | |

| • How are you sleeping at night? Do your worries or fears interrupt your sleep? Are you having bad dreams? | |

| • Who is the person you feel most comfortable talking to about your hopes, your fears, or your struggles? | |

| • What spiritual or cultural beliefs have helped you in the past? | |

| With Whom? | |

| Arrange for psychosocial or spiritual support as needed. | |

| • Consult with social worker, clinical psychologist, chaplain, spiritual care service, art therapist, or music therapist. | |

| Verify support person(s) AYA wants involved in discussions. | |

| • Processing all this information is difficult to do alone. Would you like to set up a time when we can involve your parent(s) or spouse in some of the conversations? | |

| Goals – Hopes – Dreams | When? |

| Throughout active treatment and as disease progresses | |

| How? | |

| • What things would you like to do together with your family or friends? | |

| • Are there certain events you are looking forward to, or are concerned your illness may get in the way of you participating in? | |

| With Whom? | |

| • AYA and involve others the AYA chooses. | |

| Legacy – memory-making | When? |

| Monitor during active treatment and as disease progresses. | |

| How? | |

| • What are some of your best memories as a child? As a teenager? What about during this past year? | |

| • If the world could know one thing about you, what would you want that to be? | |

| • Many AYAs have shared that they wanted something positive to come from their suffering – for example, a way to help others who have the same disease as they have. Have you had similar thoughts as these? | |

| With Whom? | |

| • Consult with social work, psychology, music therapy, art therapy, child life specialist (at pediatric hospitals), spiritual counselors. | |

| Hospice – Phase 1 Clinical Trials | When? |

| Introduce when all curative options are exhausted. Some palliative at-home services are available while participating in Phase 1 clinical trials. | |

| How? | |

| • Despite our best efforts, your cancer has continued to advance. We are no longer able to cure your disease. However, we have other options that may slow down your cancer (eg, palliative chemo). There is also the option of hospice (or other at-home support teams). These experts focus on supporting you at home so that you can continue to do the things you want to do each day for as long as possible. The third option would be a Phase I clinical trial (include discussion of risks and noncurative benefits). | |

| With Whom? | |

| Verify support person(s) AYA wants involved in discussions. | |

| • Arrange for consult with Phase 1 Clinical Trial Team or Consult with Hospice. | |

| • May wish to involve social worker to coordinate at-home services. |

Abbreviation: AYA, adolescent and young adult.

Coping with loss

Loss is inherent and pervasive in cancer care. After a patient's death, clinicians not only have to put aside their grief and return immediately to work, but often also feel that they have no one to talk to about their experiences and are plagued by painful memories.34 Lack of training in managing loss can exacerbate a care team's stress and shape the quality of care provided. Moreover, clinicians with insufficient education, hands-on training, and support in the delivery of EOL care to AYAs are susceptible to increased stress and feelings of despair, inadequacy, failure, depression, and burnout. There is a pressing need to develop effective and lasting ways to help the health-care team acquire knowledge and skills about providing palliative care to AYAs at all stages of their career to foster a resilient and strengthened workforce.78 The Schwartz Center Rounds® program is an example of a model developed to enhance compassionate care by processing shared emotions. In contrast to traditional medical rounds, the focus of the Schwartz Rounds is on the human dimension of medicine. Interdisciplinary caregivers have an opportunity to share their experiences, thoughts, and feelings on challenging and thought-provoking topics drawn from actual patient cases. The premise of the program is that clinicians are better able to make personal connections with patients and colleagues when they have greater insight into their own responses and feelings (http://www.theschwartzcenter.org).

AYA patient

Introducing palliative care as added support

When upfront therapy is not successful, a provider's first inclination is often to deliver hope to the patient by addressing other potential treatments and clinical trials. If palliative care has not been previously discussed, this is an opportune time to openly and honestly describe what the palliative care service can offer. Often, AYAs and families can have quite negative associations with the term “palliative”,90 so it may also be helpful to use clear, understandable language to describe the role of the team and explain that members of this team have expertise in managing symptoms including pain. Research in adult settings indicates that even this slight shift, to framing the palliative care service as a “supportive care service”, leads to patients and families having a better understanding of what the service does, a higher degree of perceived future need for the service, and overall more favorable impressions of it.91

Patients’ motivation to meet members of the palliative care team may be leveraged by opening a discussion around the symptoms that cause them most concern or anxiety. Benefits of proactively introducing the palliative care team as early as possible should also be described clearly to the AYA, highlighting that inclusion of palliative care prevents unnecessary levels of pain and discomfort. During disease progression, the transition between curative and palliative intent may be filled with uncertainties, thus requiring a deeper cooperation between oncology and palliative providers as well as sensitive and proactive communication with the AYA and family.92

Assess and address psychological distress

Providers should be trained to systematically assess the level of psychological distress in patients and to make appropriate and prompt referrals for symptoms of depression and anxiety. One study found that 12 months after cancer diagnoses, 41% of AYA cancer patients reported an unmet need for counseling and other forms of psychosocial support.93 Comprehensive psychological care as part of standard cancer care provides opportunities for AYAs to individually meet with a psychologist and speak openly about concerns relating to their parents, family, and friends.

Relative to older adults, who may have more experience with allied and mental health professionals and psychological concerns, AYAs may benefit from more basic introductions to teach them about the roles of different professionals (eg, a social worker versus a clinical psychologist versus a chaplain) and the services each professional provides. Despite the high incidence of mental health issues in the AYA years, AYAs may have less insight into the types of distress that they may experience. Discussing various forms of distress that commonly occur may initiate conversations around AYAs’ concerns for others in their family and social circle, whose anticipatory grief may acutely affect AYAs. Such awareness may lead to efforts to conceal their distress in order to protect one another.94

Ensuring flexibility and continuity of medical care

Best-practice psychosocial care of AYAs across the cancer trajectory involves having a dedicated advocate/clinical champion28 to address their complex palliative care needs. As AYAs transition toward EOL, having the consistency of contact with this one key “advocate” may be critical to assisting the young person to navigate this psychologically challenging time. Palliative care for AYAs warrants a unique flexibility in care delivery depending on developmental stage, a flexibility not always innate for providers. For example, physician trainees may be routinely accustomed to prerounding early in the mornings, but may find that younger AYAs benefit from the later awakening to accommodate developmental stage-related patterns of sleep cycles.95 Similarly, flexibility in scheduling appointments can be beneficial in order to suit normalized teenage routines and to avoid missing important life events.96

In some instances, enabling continuity of care may require teams to extend more creative flexibility toward AYA patients, while maintaining appropriate boundaries.64 For example, clinicians might consider providing a dedicated AYA email or phone line (eg, work mobile number) for AYAs to text or email nonemergent questions or concerns. Similarly, in teams with rotating doctors “on call”, this may mean that in certain circumstances, clinicians make themselves available to a patient/family even when not “on service”. AYAs require a sense of partnership with their care providers in order to build trust and a therapeutic relationship over the course of treatment.38 Owing to the relational role of their developmental stage and their similar age to younger staff members, AYAs are more likely than older adults to form strong therapeutic relationships with their care teams,97 an alliance that can decrease the risk of adverse psychosocial outcomes when their medical team changes.98 AYAs and trainees benefit from mentored understanding of therapeutic relationships within the context of professional boundaries.

International initiatives and cost considerations

Incorporating palliative care services within oncologic care is receiving international recognition with notable benefits for patients and health-care systems. The introduction of comprehensive and community-based palliative care services in Canada resulted in increased palliative care service delivery and cost neutrality, primarily achieved through a decreased use of acute care beds.99 A multicenter study examining resource consumption and costs of palliative care in Spain revealed reduction in hospital stay duration, an increase in the death-at-home option, a lower use of hospital emergency rooms, and an increase in programmed care.100 This Spain-based study reported a total cost saving of 61% with greater efficiency and no compromise of patient care.100 Around the same time, two urban US hospitals compared costs of palliative care integration with those of usual care.101 Palliative care was associated with significantly lower likelihood of intensive care service use and lower inpatient costs compared with usual care.101 In three African countries, investment in palliative care community training as part of a public health model has improved access to services while reducing families’ perceived physical, financial, and emotional burdens.102 Each of these findings speaks to both a cost and quality incentive for hospitals to develop and foster palliative care programs.

This article describes the important role of education and training for all countries embracing earlier integration of palliative concepts into care practices. The Clinical Oncological Society of Australia (COSA) illustrates an ideal way for countries to engage in this process, beginning with a designated agency to oversee implementation. COSA supports the formation of a federally funded national palliative care agency charged with developing Australia's capacity to provide quality palliative care to all Australians in need of palliative care regardless of their life stage and care setting. They recognize the integration of palliative care as a fundamental part of cancer care including care provision, education, training, and research. This includes providing education in quality palliative care to general practitioners within the community, as well as financial incentives for time spent on palliative care training. This agency is responsible for overseeing palliative care standards, funding, access, education, and research in Australia by promoting the value of palliative care to the community and facilitating education of the health-care workforce in the practice of quality palliative care.103

Palliative care training requires upfront investment for curricular development and professional development programs, although these investments are recognized to be cost-saving in the long run. In the U.S., a state-sponsored palliative network depicted the upfront fees as “relatively low cost” as compared with long-term impact.104 Integration of staff trained in palliative care, such as placement of advanced practice palliative care staff at critical transitions, was described as a low-cost intervention with high-cost savings in assisting with home care transitions and minimizing intensive care admissions.105 Access to palliative trained providers via a 24-hour telephone service was labeled “economically viable” with presumed spared emergency room visits and significant improvement in family comfort.106 Palliative care training may be considered an upfront investment with multiplier impacts.

Conclusion

The importance of competent, confident, and compassionate providers for AYAs warrants the development of effective educational strategies for teaching AYA palliative care. As the AYA age spectrum represents sequential transitions through developmental stages, trainees experience changes in their learning needs during their progression through sequential phases of training. Seasoned general practitioners recognize palliative care as a skill set acquired through lifelong exposure and education.107 As Wein et al64 eloquently stated, “Incorporating AYAs into a single psychosocial group necessarily involves squeezing a heterogeneous population into a square box, though many similarities exist.” We envision palliative care education as a means of quilting together these varying fabrics – a sewing together of square boxes – for the provision of comforting, practical palliative care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research; ONS Foundation/Genentech, Inc.; and the Kids with Cancer Foundation Australia.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J. Palliative care for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults. 2013;3:41–48. doi: 10.2147/COAYA.S29757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes-Lattin B, Rosenberg R, Adams H, et al. Closing the Gap: A Strategic Plan Addressing the Recommendations of the Adolescent and Young Adult Progress Review Group. LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance; Austin, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(4):288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrc2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veal GJ, Hartford CM, Stewart CF. Clinical pharmacology in the adolescent oncology patient. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4790–4799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albritton K, Caligiuri M, Anderson B, Nichols C, Ulman D. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance; Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleyer A. The adolescent and young adult gap in cancer care and outcome. Curr Probl Pediatr AdolescHealth Care. 2005;35(5):182–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleyer A, Barr R. Cancer in young adults 20 to 39 years of age: overview. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):194–206. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattano L, Nachman J, Ross J, Leukemias SW. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15–29 Years of Age, Including Incidence and Survival. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1975–2000. 2006. (NIH Pub No 06-5767) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleyer A, Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR, Jr, Wang SJ. Relative lack of conditional survival improvement in young adults with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(5):460–467. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin S, Ulrich C, Munsell M, Taylor S, Lange G, Bleyer A. Delays in cancer diagnosis in underinsured young adults and older adolescents. Oncologist. 2007;12(7):816–824. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albritton KH, Eden T. Access to care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5 Suppl):1094–1098. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleyer A, Ulrich C, Martin S. Young adults, cancer, health insurance, socioeconomic status, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6018–6021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrari A, Montello M, Budd T, Bleyer A. The challenges of clinical trials for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5 Suppl):1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleyer A, Montello M, Budd T, Saxman S. National survival trends of young adults with sarcoma: lack of progress is associated with lack of clinical trial participation. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1891–1897. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downs-Canner S, Shaw PH. A comparison of clinical trial enrollment between adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology patients treated at affiliated adult and pediatric oncology centers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(12):927–929. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181b91180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollock BH, Birch JM. Registration and classification of adolescent and young adult cancer cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5 Suppl):1090–1093. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freyer DR, Kibrick-Lazear R. In sickness and in health: transition of cancer-related care for older adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2006;107(7 Suppl):1702–1709. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freyer DR, Brugieres L. Adolescent and young adult oncology: transition of care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5 Suppl):1116–1119. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood cancer: coming of age. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):211–231. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulrooney DA, Neglia JP, Hudson MM. Caring for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9(1):51–66. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent EE, Parry C, Montoya MJ, Sender LS, Morris RA, Anton-Culver H. “You’re too young for this”: adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(2):260–279. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.644396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatia S, Landier W, Shangguan M, et al. Nonadherence to oral mercaptopurine and risk of relapse in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2094–2101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser LK, Miller M, McKinney PA, Parslow RC, Feltbower RG. Referral to a specialist paediatric palliative care service in oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(4):677–680. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zebrack B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S, Alliance LYA. Quality cancer care for adolescents and young adults: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4862–4867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zebrack BJ, Mills J, Weitzman TS. Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(2):137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox HB, McManus MA, Diaz A, et al. Advancing medical education training in adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):1043–1045. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wender EH, Bijur PE, Boyce WT. Pediatric residency training: ten years after the Task Force report. Pediatrics. 1992;90(6):876–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser HC, Kutner JS, Pfeifer MP. Senior medical students’ perceptions of the adequacy of education on end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(3):337–343. doi: 10.1089/109662101753123959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickinson GE. A quarter century of end-of-life issues in US medical schools. Death Stud. 2002;26(8):635–646. doi: 10.1080/07481180290088347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248–1252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker M, Wrubel J, Rabow MW. Professional development and the informal curriculum in end-of-life care. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(3):444–450. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1752–1762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeely C. The Teen Years Explained: A Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development. Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nass SJ, Patlak M, editors. Identifying and Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arpawong TE, Oland A, Milam JE, Ruccione K, Meeske KA. Post-traumatic growth among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.3286. Epub April 2, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butow P, Palmer S, Pai A, Goodenough B, Luckett T, King M. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4800–4809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825–4830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Billings JA, Block S. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education. Status report and future directions. JAMA. 1997;278(9):733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anneser J, Kunath N, Krautheim V, Borasio GD. Needs, expectations, and concerns of medical students regarding end-of-life issues before the introduction of a mandatory undergraduate palliative care curriculum. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1201–1205. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker JN, Torkildson C, Baillargeon JG, Olney CA, Kane JR. National survey of pediatric residency program directors and residents regarding education in palliative medicine and end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):420–429. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bravender T. Teaching adolescent medicine in the office setting. Curr opin Pediatr. 2002;14(4):389–394. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacPherson A, Lawrie I, Collins S, Forman L. Teaching the difficultto-teach topics. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(1):87–91. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olthuis G, Dekkers W. Medical education, palliative care and moral attitude: some objectives and future perspectives. Med Educ. 2003;37(10):928–933. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaheen AW, Denton GD, Stratton TD, Hoellein AR, Chretien KC. End-of-life and palliative care curricula in internal medicine clerkships: a report on the presence, value, and design of curricula as rated by clerkship directors. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1168–1173. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steen PD, Miller T, Palmer L, et al. An introductory hospice experience for third-year medical students. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14(3):140–143. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellman MS, Rosenbaum JR, Cherlin E, Bia M. Effectiveness of an integrated ward-based program in preparing medical students to care for patients at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(1):18–23. doi: 10.1177/1049909108325437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacoby LH, Beehler CJ, Balint JA. The impact of a clinical rotation in hospice: medical students’ perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):59–64. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olden AM, Quill TE, Bordley D, Ladwig S. Evaluation of a required palliative care rotation for internal medicine residents. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(2):150–154. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]