Abstract

Activation and inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels are critical for proper electrical signaling in excitable cells. Pyrethroid insecticides promote activation and inhibit inactivation of sodium channels, resulting in prolonged opening of sodium channels. They preferably bind to the open state of the sodium channel by interacting with two distinct receptor sites, pyrethroid receptor sites PyR1 and PyR2, formed by the interfaces of domains II/III and I/II, respectively. Specific mutations in PyR1 or PyR2 confer pyrethroid resistance in various arthropod pests and disease vectors. Recently, a unique mutation, N1575Y, in the cytoplasmic loop linking domains III and IV (LIII/IV) was found to coexist with a PyR2 mutation, L1014F in IIS6, in pyrethroid-resistant populations of Anopheles gambiae. To examine the role of this mutation in pyrethroid resistance, N1575Y alone or N1575Y + L1014F were introduced into an Aedes aegypti sodium channel, AaNav1-1, and the mutants were functionally examined in Xenopus oocytes. N1575Y did not alter AaNav1-1 sensitivity to pyrethroids. However, the N1575Y + L1014F double mutant was more resistant to pyrethroids than the L1014F mutant channel. Further mutational analysis showed that N1575Y could also synergize the effect of L1014S/W, but not L1014G or other pyrethroid-resistant mutations in IS6 or IIS6. Computer modeling predicts that N1575Y allosterically alters PyR2 via a small shift of IIS6. Our findings provide the molecular basis for the coexistence of N1575Y with L1014F in pyrethroid resistance, and suggest an allosteric interaction between IIS6 and LIII/IV in the sodium channel.

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels are responsible for the rapidly rising phase of action potentials (Catterall, 2012). Because of their critical role in membrane excitability, sodium channels are the primary target site of a variety of naturally occurring and synthetic neurotoxins, including pyrethroid insecticides (Catterall et al., 2007). Pyrethroids promote activation and inhibit inactivation of sodium channels, resulting in prolonged opening of sodium channels (Vijverberg et al., 1982; Narahashi, 1996). Pyrethroid insecticides possess high insecticidal activities and low mammalian toxicity and represent one of the most powerful weapons in the global fight against malaria and other arthropod-borne human diseases. However, the efficacy of pyrethroids is undermined as a result of emerging pyrethroid resistance in arthropod pests and disease vectors. One major resistance mechanism is known as knockdown resistance (kdr), which arises from mutations in the sodium channel (Soderlund, 2005; Rinkevich et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2014).

The pore-forming α-subunit of the sodium channel is composed by four homologous domains (I–IV), each having six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) connected by intracellular and extracellular loops. The S1–S4 segments in each domain serve as the voltage-sensing module, whereas the S5 and S6 segments and the loops connecting them function as the pore-forming module. In response to membrane depolarization, the S4 segments move outward, initiating conformational changes that lead to pore opening and subsequent inactivation of sodium channels. Short intracellular linkers connecting S4 and S5 segments of sodium channels, L45, transmit the movements of the voltage-sensing modules to the S6 segments during channel opening and closing. Fast inactivation is achieved by the movement of an inactivation gate formed mainly by the IFM motif in the short intracellular linker connecting domains III and IV, which physically occludes the open pore.

In recent years, using X-ray structures of a bacterial potassium channel KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998), the mammalian voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.2 crystallized in the open state (Long et al., 2005) and a bacterial sodium channel, NavAb, crystallized in the closed state (Payandeh et al., 2011) as templates, homology models of eukaryotic sodium channels have been developed to predict binding sites of sodium channel neurotoxins (Lipkind and Fozzard, 2005; O’Reilly et al., 2006; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2007, 2012; Du et al., 2013). Mutational analyses coupled with computer modeling show that pyrethroids bind to two analogous receptor sites. Pyrethroid receptor site 1 (PyR1) is formed by residues from helices IIL45, IIS5, and IIIS6 (O’Reilly et al., 2006), whereas pyrethroid receptor site 2 (PyR2) is formed by residues from helices IL45, IS5, IS6, and IIS6 (Du et al., 2013). Binding of pyrethroid molecules at the two sites is believed to effectively trap the sodium channel in the open state, resulting in the prolonged opening of sodium channels (Du et al., 2013).

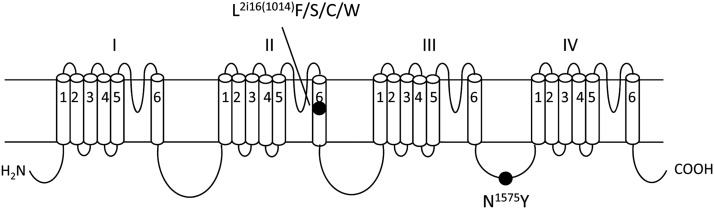

The most frequent kdr mutation in arthropod pests and disease vectors is a leucine to phenylalanine (L1014F in the house fly sodium channel) in IIS6, which is also known as L2i16F using the nomenclature that is universal for sodium channels and other P-loop ion channels (Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004; Du et al., 2013) (Fig. 1). The L2i16(1014)F mutation has been detected in the malaria vector Anopheles mosquito species in many regions around the world (Martinez-Torres et al., 1998; Enayati et al., 2003; Karunaratne et al., 2007). Recently, a new sodium channel mutation N1575Y was reported in the malaria mosquito, An. gambiae, in Africa (Jones et al., 2012). The N1575Y mutation is located in the intracellular cytoplasmic loop connecting domains III and IV (LIII/IV) (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, the N1575Y mutation was only found in conjunction with L2i16(1014)F: no mosquito individuals were detected harboring only the N1575Y mutation (Jones et al., 2012). Interestingly, pyrethroid bioassays indicate that mosquitoes carrying the double mutations L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y are more resistant to permethrin than mosquitoes carrying only the L2i16(1014)F mutation (Jones et al., 2012). However, whether the N1575Y mutation confers pyrethroid resistance has not been functionally confirmed yet. In this study, we conducted site-directed mutagenesis, functional analysis in Xenopus oocytes, and computer modeling to investigate the role of N1575Y in pyrethroid resistance.

Fig. 1.

The topology of the sodium channel protein indicating the position of L2i16(1014)F/S/C/W and N1575Y mutations. The sodium channel protein consists of four homologous domains (I–IV), each formed by six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) connected by intracellular and extracellular loops. Residue positions L1014F and N1575Y correspond to the housefly sodium channel (GenBank accession numbers: AAB47604 and AAB47605). L2i16F is labeled using the nomenclature that is universal for P-loop ion channels, in which a residue is labeled by the domain number (1–4), segment type (k, L45 linker; i, inner helix, i.e., S6; o, outer helix, i.e., S5), and the relative number of the residue in the segment.

Materials and Methods

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Because sodium channels from An. gambiae have not been successfully expressed in the Xenopus oocyte expression system for functional characterization, we used a mosquito sodium channel (AaNav1-1), from Aedes aegypti to generate all mutants used in this study. The kdr mutations that are explored in this study are located in regions that are highly conserved between sodium channels from An. gambiae and Ae. aegypti (Supplemental Fig. 1). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by polymerase chain reaction using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutagenesis results were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression of AaNav Sodium Channels in Xenopus Oocytes.

The procedures for oocyte preparation and cRNA injection are identical to those described previously (Tan et al., 2002b). For robust expression of AaNav1-1 sodium channels, cRNAs were coinjected into oocytes with Ae. aegypti TipE cRNA (1:1 ratio), which enhances the expression of sodium channels in oocytes.

Electrophysiological Recording and Analysis.

The voltage dependence of activation and inactivation was measured using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique. Methods for two-electrode recording and data analysis were identical to those described previously (Tan et al., 2002a).

The voltage dependence of sodium channel conductance (G) was calculated by measuring the peak current at test potentials ranging from −80 to +65 mV in 5 mV increments and divided by (V − Vrev), where V is the test potential and Vrev is the reversal potential for sodium ions. Peak conductance values were normalized to the maximal peak conductance (Gmax) and fitted with a two-state Boltzmann equation of the form:

in which V is the potential of the voltage pulse, V1/2 is the voltage for half-maximal activation, and k is the slope factor.

The voltage dependence of sodium channel inactivation was determined by using 100 millisecond inactivating prepulses ranging from −120 to 10 mV in 5 mV increments from a holding potential of −120 mV, followed by test pulses to −10 mV for 20 milliseconds. The peak current amplitude during the test depolarization was normalized to the maximum current amplitude and plotted as a function of the prepulse potential. Data were fitted with a two-state Boltzmann equation of the form:

in which I is the peak sodium current, Imax is the maximal current evoked, V is the potential of the voltage prepulse, V1/2 is the half-maximal voltage for inactivation, and k is the slope factor. Sodium current decay was analyzed by fitting the decaying part of current traces with a single exponential function.

Measurement of Tail Currents Induced by Pyrethroids.

The method for application of pyrethroids in the recording system was identical to that described previously (Tan et al., 2002a). The effects of pyrethroids were measured 10 minutes after their application. The pyrethroid-induced tail current was recorded during a 100 pulse train of 5 millisecond step depolarizations from −120 to 0 mV with 5 millisecond interpulse intervals (Vais et al., 2000). The percentage of channels modified by pyrethroids was calculated using the following equation (see Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994):

where Itail is the maximal tail current amplitude, Eh is the potential to which the membrane is repolarized, ENa is the reversal potential for sodium current determined from the current-voltage curve, INa is the amplitude of the peak current during depolarization before pyrethroid exposure, and Et is the potential of step depolarization.

Molecular Modeling.

We used the Kv1.2-based model of the open AaNav1-1 channel with deltamethrin bound into PyR2 (Du et al., 2013) as a starting point to generate models of mutants with deltamethrin. Because pyrethroids preferably bind to sodium channels in the open state, the X-ray structure of the open potassium channel Kv1.2 (Long et al., 2005) was used as a template in this study and also in previous models of insect sodium channels with pyrethroids (O’Reilly et al., 2006, 2014; Du et al., 2013). The selectivity-filter region, which is substantially different between potassium and sodium channels, was not included in the models because it is far from the pyrethroid receptors (O’Reilly et al., 2006; Usherwood et al., 2007). Homology modeling and ligand docking were performed using the ZMM program (www.zmmsoft.com). Monte Carlo minimization protocol (Li and Scheraga, 1987) was used for energy optimization as described in Du et al. (2013) and Garden and Zhorov (2010). The complexes were visualized with the PyMol (Molecular Graphics System, Version 0.99rc6; Schrödinger, New York).

Chemicals.

Deltamethrin was kindly provided by Bhupinder Khambay (Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, United Kingdom). Deltamethrin was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide. The working concentration was prepared in ND96 recording solution immediately prior to experiments. The concentration of dimethylsulfoxide in the final solution was <0.5%, which had no effect on the function of sodium channels.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was determined by using one-way analysis of variance with Scheffe’s post hoc analysis, and significant values were set at P < 0.05.

Results

N1575Y Does Not Alter the Gating Properties of AaNav1-1 Channels.

The N1575Y mutation is located in LIII/IV, which is important for fast inactivation of sodium channels (Catterall, 2002; Goldin, 2003). To determine whether the N1575Y mutation alters inactivation kinetics, we introduced this mutation into AaNav1-1 and expressed both AaNav1-1 and mutant channels in Xenopus oocytes. As with AaNav1-1, the mutant channel produced sufficient sodium currents for functional analysis (Fig. 2). AaNav1-1 and N1575Y channels had similar rates of sodium current decay over the entire range of voltages examined, indicating that the mutation did not alter the kinetics of fast inactivation (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the mutation did not alter the voltage dependence of either activation or inactivation (Table 1).

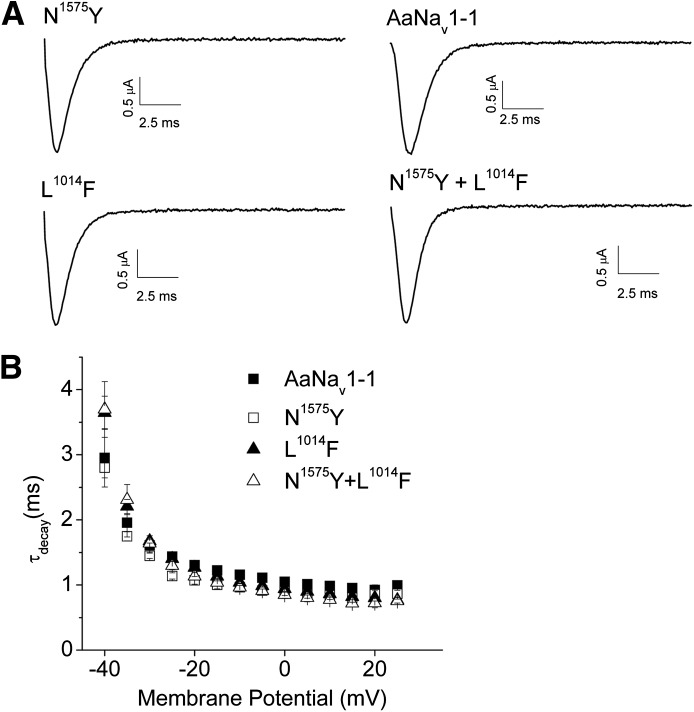

Fig. 2.

N1575Y does not alter inactivation kinetics. (A) Representative current traces. The sodium currents were elicited by a 20-millisecond depolarization to 0 mV from the holding potential of −120 mV. (B) Voltage dependence of the sodium current decay. Time constant of sodium current decay was calculated by fitting the decaying part of current traces, elicited by a series of depolarizing voltages, with a single exponential function.

TABLE 1.

Voltage dependence of activation and fast inactivation of AaNav1-1 and its mutants.

The voltage dependence of conductance and inactivation data were fitted with two-state Boltzmann equations, as described in the Materials and Methods, to determine V1/2, the voltage for half-maximal conductance or inactivation and k, the slope for conductance or inactivation. Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M.

| Activation | Fast Inactivation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

V1/2 |

k |

V1/2 |

k |

n |

|

| mV | mV | ||||

| AaNav1-1 | −33.6 ± 1.1 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | −53.7 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 19 |

| N1575Y | −32.3 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | −56.5 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 20 |

| L2i16(1014)F | −31.3 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | −49.6 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 10 |

| L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y | −28.6 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | −51.1 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 27 |

| L2i16(1014)S | −36.3 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | −50.0 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 11 |

| L2i16(1014)S + N1575Y | −33.8 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | −51.5 ± 0.7 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 10 |

| L2i16(1014)W | −30.2 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | −50.3 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 6 |

| L2i16(1014)W + N1575Y | −29.8 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | −53.2 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| L2i16(1014)G | −31.5 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | −48.9 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 7 |

| L2i16(1014)G + N1575Y | −34.2 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | −52.3 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 9 |

| L2i16(L1014)C | −37.5 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | −51.8 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| V2i18(1016)G | −33.0 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | −51.8 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 6 |

| V2i18(1016)G + N1575Y | −35.4 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | −52.1 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 7 |

| L1i18G | −30.1 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | −49.2 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| L1i18G + N1575Y | −32.5 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | −50.0 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 6 |

| L1i18F | −29.7 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | −42.9 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| L1i18F + N1575Y | −30.7 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | −44.2 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 7 |

| L1i18W | −29.0 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | −48.4 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| L1i18W + N1575Y | −28.2 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | −53.3 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| S1i29A | −33.2 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | −51.2 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| S1i29A + N1575Y | −32.0 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | −50.2 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 6 |

Because the N1575Y mutation coexists with the L2i16(1014)F mutation in An. gambiae (Jones et al., 2012), the N1575Y change was also introduced into AaNav1-1 carrying the L2i16(1014)F mutation, which was generated in a previous study (Du et al., 2013), to create a double mutation construct L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y. Similarly, L2i16(1014)F and L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y channels exhibited similar fast inactivation kinetics compared with AaNav1-1 (Fig. 2). The voltage dependences of activation and inactivation of both mutant channels were also similar to those of the AaNav1-1 channel (Table 1).

N1575Y Enhances L2i16(1014)F-Mediated Resistance to Pyrethroids, but Does Not Confer Pyrethroid Resistance Alone.

To examine the effect of the N1575Y mutation on the sensitivity of AaNav1-1 channels to pyrethroids, we compared the sensitivities of AaNav1-1, N1575Y, L2i16(1014)F, and L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y channels to both a type I pyrethroid, permethrin, and a type II pyrethroid, deltamethrin. The percentage of sodium channel modification by pyrethroids was determined by measuring pyrethroid-induced tail currents upon repolarization in voltage-clamp experiments. The effect of permethrin on the N1575Y channel was similar to that on AaNav1-1 (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the permethrin-induced tail current was reduced by the L2i16(1014)F mutation and more drastically by L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y double mutations (Fig. 3, B–D). Furthermore, analysis of the dose-response curves of modification of AaNav1-1 and the three mutant channels by permethrin and deltamethrin showed that the L2i16(1014)F mutant channel was about 8-fold more resistant to permethrin than the AaNav1-1 channel (Fig. 3E) and the L2i16(1014)F channel was 14-fold more resistant to deltamethrin than the AaNav1-1 channel (Fig. 3F). Remarkably, the L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y channel was 80-fold more resistant to permethrin and 53-fold more resistant to deltamethrin than the wild-type channel. Therefore, the N1575Y mutation increased resistance to permethrin and deltamethrin by 9.8- and 3.4-fold, respectively, when combined with the L2i16(1014)F + N1575Y mutation. However, the N1517Y mutation had no effect on channel sensitivity to either pyrethroid.

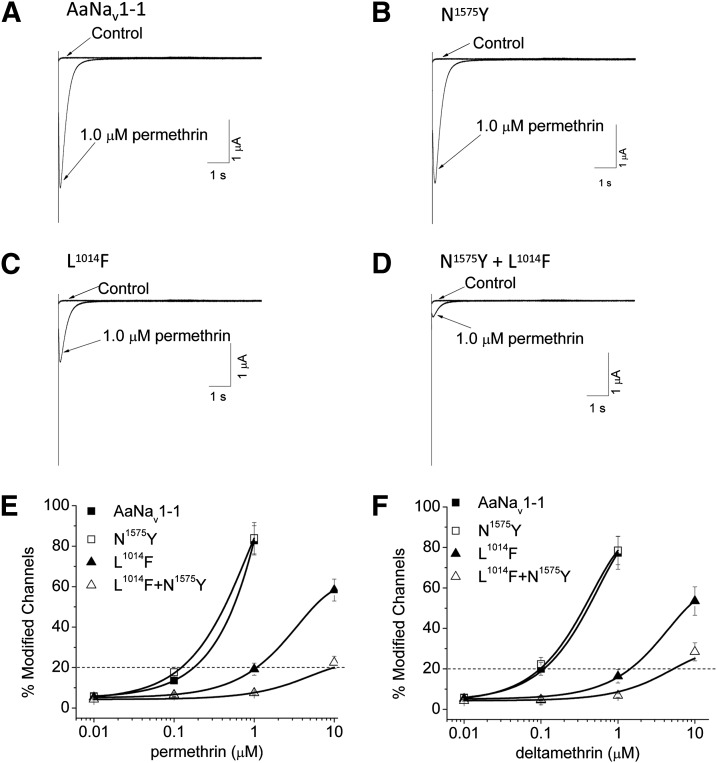

Fig. 3.

The L1014F + N1575Y double mutation reduced the sensitivity of AaNav1-1 channels to permethrin and deltamethrin. (A–D) Tail currents induced by permethrin (1 µM) in AaNav1-1 (A), N1575Y (B), L1014F (C), and L1014F + N1575Y (D) channels. (E and F) Percentage of channel modification by permethrin (E) and deltamethrin (F) of wild-type and mutant channels. Percentage of channels modified by pyrethroids was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods. The values of EC20 for permethrin were 0.12, 0.18, 1.0, and 9.8 µM for AaNav1-1, N1575Y, L1014F, and L1014F + N1575Y channels, respectively. The values of EC20 for deltamethrin were 0.1, 0.11, 1.4, and 5.3 µM for AaNav1-1, N1575Y, L1014F, and L1014F + N1575Y channels, respectively. The number of oocytes for each mutant construct was >5. Each data point indicates mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the AaNav1-1 channel as determined by using one-way analysis of variance with Scheffe’s post hoc analysis, and significant values were set at P < 0.05.

N1575Y Enhances Pyrethroid Resistance Caused by L2i16(1014)S/W Mutations.

Our aforementioned results indicate that the N1575Y mutation imposes a synergistic effect on pyrethroid resistance caused by the L2i16(1014)F mutation. To see whether such synergism extends to pyrethroid resistance caused by other kdr mutations identified in pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes, we examined three additional kdr mutations, L2i16(1014)S/C/W, which have been reported in various mosquito species (Ranson et al., 2000; Lüleyap et al., 2002; Stump et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2007; Kawada et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2010; Verhaeghen et al., 2010; Kasai et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). These mutations did not affect the voltage dependence of activation or inactivation of AaNav1-1 channels either alone or in conjunction with the N1575Y mutation (Table 1). Consistent with results from a previous study (Du et al., 2013), the L2i16(1014)S channel was 6.7- and 9-fold more resistant to permethrin and deltamethrin, respectively, than the AaNav1-1 channel (Fig. 4, A and B). The L2i16(1014)S + N1575Y double mutant channel was 58- and 32-fold more resistant to permethrin and deltamethrin, respectively, than the AaNav1-1 channel (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, the L2i16(1014)W mutant channel was more resistant to permethrin and deltamethrin than the AaNav1-1 channel by about 9.7- and 7-fold, respectively (Fig. 4, C and D), and introduction of N1575Y mutation into the L2i16(1014)W channel caused additional 10.5- and 13-fold resistance to permethrin and deltamethrin (101.8- and 91-fold resistance to permethrin and deltamethrin versus wild-type), respectively (Fig. 4, C and D). Another kdr mutation at the same position, L2i16(1014)C, also caused 3.5- and 4.2-fold reduction in AaNav1-1 sensitivity to permethrin and deltamethrin, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2). However, the L2i16(1014)C + N1575Y double mutant did not produce sufficient sodium currents in oocytes for further functional analysis.

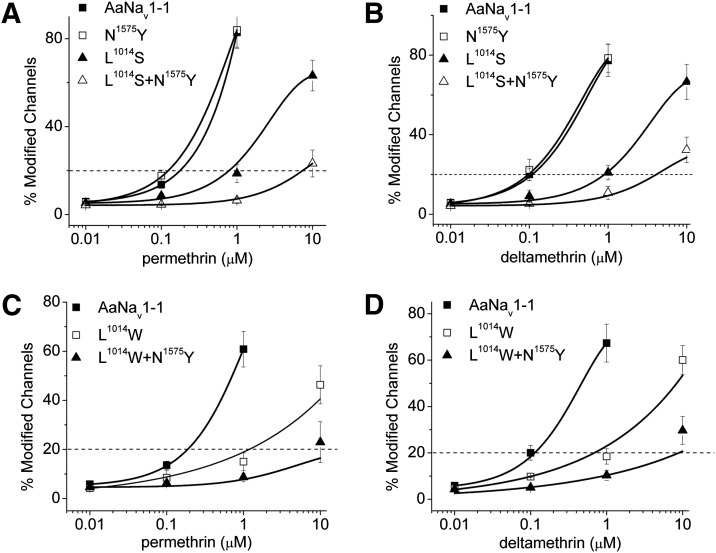

Fig. 4.

N1575Y enhanced resistance to pyrethroids caused by L1014S/W. Effects of L1014S/W (A, B and C, D, respectively) mutations on the sensitivity of AaNav1-1 channels to permethrin (A and C) or deltamethrin (B and D). Percentages of channel modification by permethrin or deltamethrin were determined using the method described in the Materials and Methods. The number of oocytes for each mutant construct was >5. Each data point indicates mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the AaNav1-1 channel as determined by using one-way analysis of variance with Scheffe’s post hoc analysis, and significant values were set at P < 0.05.

N1575Y Did Not Enhance Pyrethroid Resistance Caused by Another kdr Mutation in IIS6.

Next, we examined another kdr mutation in IIS6, V2i18(1016)G, which is detected in pyrethroid-resistant populations of Ae. aegypti (Saavedra-Rodriguez et al., 2007). Although all located in IIS6, L2i16(1014)F/S/W and V2i18(1016)G belong to PyR2 and PyR1, respectively (Du et al., 2013). We introduced the N1575Y mutation into the V2i18(1016)G channel construct, which was available from a previous study (Du et al., 2013). Consistent with the finding from the previous study, the V2i18(1016)G mutation significantly reduced AaNav1-1 channel sensitivity to both permethrin and deltamethrin (Fig. 5, B and C), but the addition of the N1575Y mutation did not further enhance the level of resistance to pyrethroids (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5.

N1575Y did not enhance pyrethroid resistance caused by other mutations examined in this study. (A) The positions of the mutations in the sodium channel protein. The amino acid sequence of the linker connecting domains III and IV is shown below the topology, The MFMT motif, which is critical for fast inactivation, is underlined. The N1575Y mutation is marked in bold. Residue P1596 in this linker, whose leucine substitution was previously confirmed to increase pyrethroid potency, is also shown in bold. (B and C) Effects of N1575Y on the sensitivity of AaNav1-1 wild-type and mutant channels to 1 μM permethrin (B) and 1 μM deltamethrin (C). The number of oocytes for each mutant construct was >5. Each data point indicates mean ± S.E.M. The percentage of channel modification for all mutant channels except N1575Y was significantly different from that of the AaNav1-1 channel, but with no significant difference between the double mutants and their respective singles, as determined by using one-way analysis of variance with Scheffe’s post hoc analysis, and significant values were set at P < 0.05.

N1575Y Did Not Enhance Pyrethroid Resistance Caused by Other Mutations in PyR2.

Many kdr mutations are located within the two pyrethroid-binding sites and/or are involved in regulating channel kinetics and voltage-dependent gating (Dong et al., 2014). N1575Y is not located in either of the pyrethroid receptor sites and does not affect inactivation kinetics or channel gating (Fig. 2; Table 1). Therefore, we hypothesize that N1575Y exerts its effect by allosterically altering one of the pyrethroid binding sites. The alteration per se must be small because N1575Y alone does not affect the action of pyrethroids except in the presence of another resistance-associated mutation at L2i16(1014). Since the N1575Y mutation enhances the effect of mutations at L2i16(1014), but not at V2i18(1016)G, we then focused on residues in PyR2 to determine the extent of the N1575Y-mediated synergism. In the PyR2 model (Du et al., 2013), the side chain of L2i16(1014) is directed toward the pyrethroid-sensing residue L1i18 in IS6 (Fig. 6A). Consistent with previous findings (Du et al., 2013), L1i18G reduced AaNav1-1 channel sensitivity to permethrin and deltamethrin. However, the double mutation L1i18G + N1575Y was not more resistant to pyrethroids than the single mutant, L1i18G or S1i29A (Fig. 5, B and C). Furthermore, we introduced two additional substitutions, L1i18F and L1i18W, into both the AaNav1-1 and N1575Y channels. As with L1i18G, both substitutions reduced the action of pyrethroids (Fig. 5, B and C) and the N1575Y mutation did not enhance pyrethroid resistance caused by either mutation (Fig. 5, B and C). In addition, S1i29 at the C end of IS6 is predicted to approach the α-cyano group of deltamethrin and favorably contribute to ligand-channel interactions (Fig. 6, A and B). Here, we showed that S1i29A decreased channel sensitivity to pyrethroids (Fig. 5, B and C), further supporting the PyR2 model. However, the S1i29A + N1575Y channel was not more resistant to both pyrethroids than the single S1i29A mutant. Collectively, these results suggest that the modification of the receptor site by N1575Y may be L2i16(1014) specific. It is possible that unfavorable interactions of the hydrophobic ligand with large aromatic substitutions L2i16(1014)F/W or hydrophilic substitution L2i16(1014)S were enhanced by N1575Y. Thus, we examined a glycine substitution of L2i16(1014), i.e., L2i16(1014)G, for pyrethroid sensitivity. As with L2i16(1014)F/S/W, the L2i16(1014)G substitution reduced the AaNav1-1 channel sensitivity to permethrin and deltamethrin. However, the L2i16(1014)G + N1575Y double mutant channel was as sensitive as the L2i16(1014)G channel to both permethrin and deltamethrin (Fig. 5, B and C). These results suggest that the effect of N1575Y on pyrethroid binding, potentially causing a small conformational shift in IIS6, is sensitive to the nature of the residue at position 2i16 (1014).

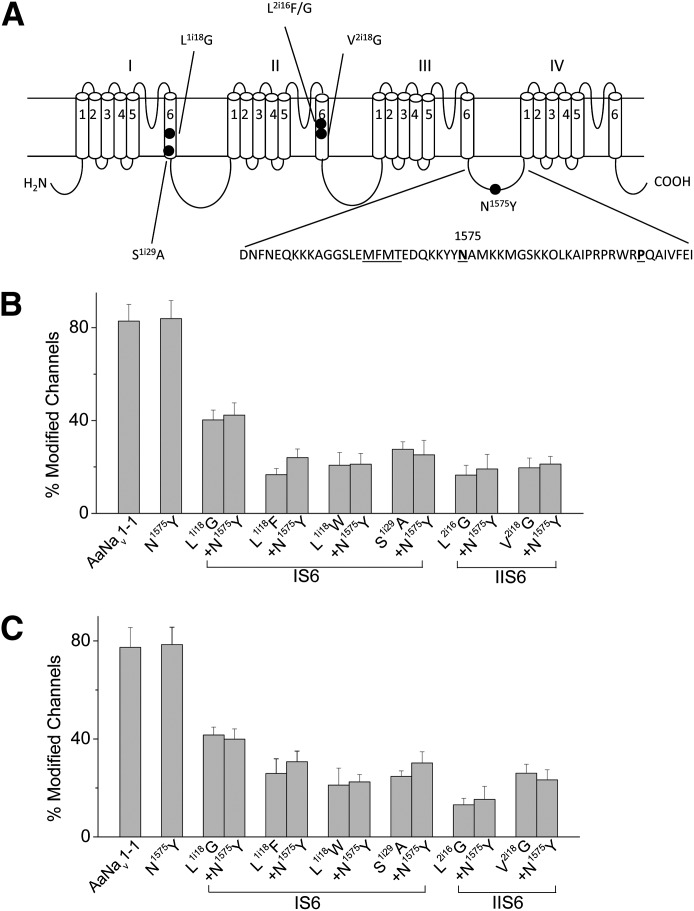

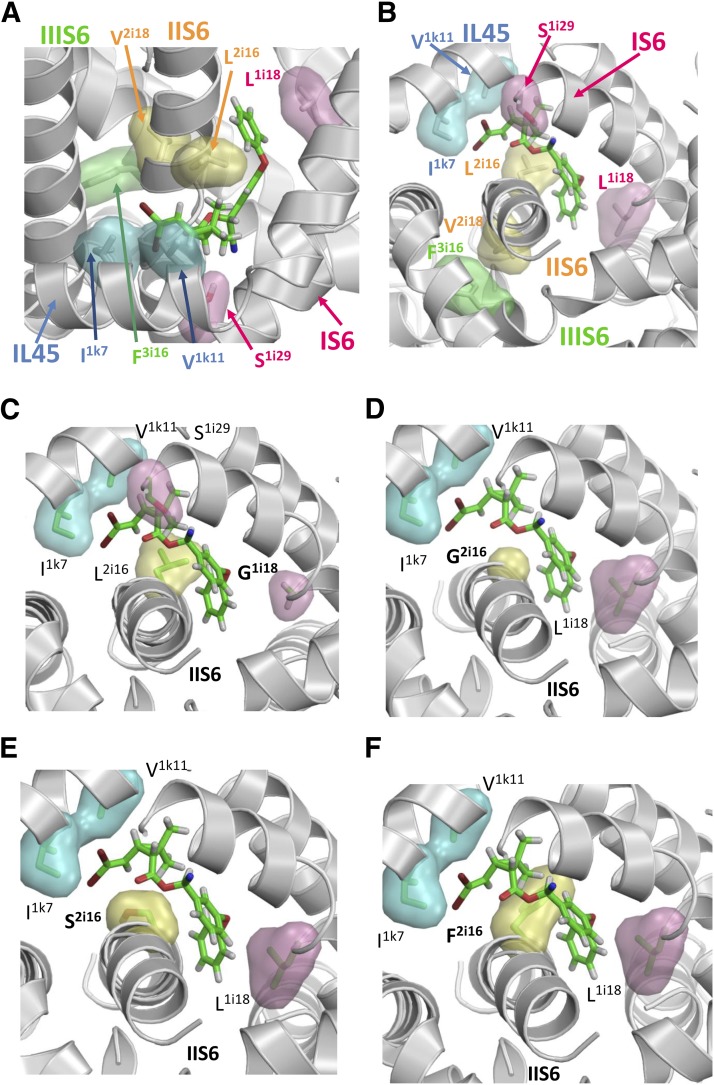

Fig. 6.

Kv1.2-based model of the open AaNav1-1 channel with deltamethrin bound to PyR2. Side (A) and cytoplasmic (B) views. Deltamethrin is shown by sticks with green carbons, red oxygens, gray hydrogens, and brown bromine atoms. Semitransparent cyan, pink, yellow, and green surfaces show pyrethroid-sensing residues in helices IL45, IS6, IIS6, and IIIS6, respectively. Note that helix IIS6 contributes residue L2i16 to PyR2 and may contribute residue V2i18 to PyR1, which contains F3i16 in helix IIIS6. (C–F), Cytoplasmic view along helix IIS6 of models of AaNav1-1 mutants L1i18G (C), L2i16G (D), L2i16S (E), and L2i16F (F) of the open AaNav1-1 channel with deltamethrin bound in the pyrethroid receptor PyR2. The long flexible side chain of L2i16 in the L1i18G mutant (C) and the wild-type channel (B) favorably interact with the ligand and a small shift of helix IIS6 upon mutation N1575Y would have little effect on this interaction. The ligand potency in the L2i16G mutant (D) would also have low sensitivity to the IIS6 shift because the tiny side chain of G2i16 is located rather far from the ligand. However, the IIS6 shift would deteriorate unfavorable interactions of the hydrophilic S2i16 with the hydrophobic ligand (E) or would cause an unfavorable clash of deltamethrin with the big and inflexible F2i16 (D).

Possible Mechanism of Synergy between N1575Y and L2i16(1014)F/S/W Mutations.

To explore how N1575Y enhances pyrethroid resistance of AaNav1-1 channels when combined with the L2i16(1014)F/S/W mutations, but not in wild-type or with the L2i16G mutation, we compared the model of deltamethrin binding in PyR2 of the wild-type open AaNav1-1 channel and the mutants (Fig. 6). PDB format files for the AaNav1-1 channel models are provided in the Supplemental Material. In the wild-type channel, deltamethrin favorably interacts with the long flexible side chain of L2i16(1014) (Fig. 6A). Comparison of deltamethrin binding models in the wild-type channel and mutants L1i18G (Fig. 6C) and L2i16G (Fig. 6D) suggests two consequences of the glycine substitutions. First, the favorable interactions of the hydrophobic ligand with the large hydrophobic pyrethroid-sensing residues are lost. Second, there is significantly more space in the pyrethroid binding site following mutation of L2i16 to G. Models of deltamethrin binding in the L2i16S and L2i16F mutants show unfavorable interactions between the hydrophilic S2i16 or the large and inflexible F2i16 with the hydrophobic ligand (Fig. 6, E and F). Therefore, we suggest that enhancement of pyrethroid resistance in the presence of the L2i16(1014)F/S/W mutations occurs as a result of a slight shift of IIS6. The shift does not affect either the favorable interaction of pyrethroids with L2i16 or the less sterically constrained interactions of deltamethrin with the L2i16G mutation. In contrast, the slight shift of IIS6 likely further deteriorates the energetically unfavorable interactions of deltamethrin with L2i16(1014)F/S/W, enhancing pyrethroid resistance in the double mutant.

Discussion

Identification of naturally occurring mutations in the sodium channel that confer kdr to pyrethroids has greatly advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of kdr and the molecular details of pyrethroid receptor sites (Dong et al., 2014). Emerging evidence suggests that binding of pyrethroids to two distinct pyrethroid receptor sites, PyR1 and PyR2, at two analogous domain interfaces is necessary to trap sodium channels in the open state, which leads to prolonged opening of sodium channels and the toxic effects of pyrethroids in vivo. Importantly, many, but not all, kdr mutations that cause pyrethroid resistance are located within the two pyrethroid receptor sites (Dong et al., 2014), and it is not clear how kdr mutations beyond the receptor sites affect pyrethroid sensitivity of sodium channels. In this study, we investigated the role of a pyrethroid resistance-associated mutation, N1575Y, which is located in the intracellular loop connecting domains III and IV (outside of PyR1 and PyR2) in pyrethroid resistance. We found that this mutation alone has no effect on the action of pyrethroids on sodium channels, but it enhances pyrethroid resistance caused by the L2i16(1014)F/S/W mutations. Based on further mutational analysis and computer modeling, we hypothesize that N1575 induces a small shift of the transmembrane helix IIS6, resulting in slight deformation of PyR2, which enhances the energetically unfavorable interactions between deltamethrin and the L2i16(1014)F/S/W mutations, but does not affect the energetically favorable interactions between pyrethroids and L2i16(1014). These results provide a satisfying explanation for the concurrent existence of N1575Y and L2i16(1014)F in pyrethroid-resistant mosquito populations.

BLAST searches show that the asparagine residue (equivalent to N1575 in An. gambiae) in the LIII/IV loop sequence is highly conserved among voltage-gated sodium channels. However, N1575Y has no effect on the kinetics of fast inactivation, implying that this mutation does not interfere with the docking of the inactivation particle (the motif MFMT in LIII/IV) to its receptor site, which is composed of residues in the linkers connecting S4 and S5 of domains III and IV (Goldin, 2003). Our molecular modeling (Fig. 6) predicts that a slight shift of helix IIS6 in the N1575Y channel could explain the synergism on pyrethroid resistance between N1575Y and specific mutations at L2i16(1014)F in IIS6, which is also supported by our mutational analysis (Figs. 3–5). However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of the N1575Y/L2i16(1014)F double mutation causing an allosteric effect on the action of pyrethroids without directly involving IIS6.

How a mutation in the intracellular loop between domains III and IV (LIII/IV) can shift helix IIS6 carrying the L2i16(1014)F mutation remains speculative. In X-ray structures of both open and closed ion channels, the cytoplasmic parts of the S6 helices approach each other to form the activation gate, and cytoplasmic linkers may also approach each other. We speculate that the asparagine side chain in LIII/IV is involved in specific contacts (likely, an H-bond) with LII/III. Replacement of a small asparagine with a much bigger tyrosine in N1575Y could cause a change in the mutual disposition of the two linkers, which, in turn, would shift helix IIS6. This predicted small shift in IIS6 by N1575Y apparently only alters the action of pyrethroids on L2i16(1014)F/S/C/W channels, but not on L2i16G and V2i18(1016)G channels. This may be because a small distortion of PyR2 upon the N1575Y mutation does not affect a weak pyrethroid interaction with a glycine residue, which has a single hydrogen atom in the side chain.

Besides N1575Y, there are several other sodium channel mutations within LIII/IV that have been reported to be associated with pyrethroid resistance (Rinkevich et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2014). The frequent occurrence of mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance in this linker supports the allosteric interactions between IIS6 and LIII/IV in the sodium channel. For example, L1596P was found to be associated with pyrethroid resistance in Varroa mites (Fig. 5) (Dong et al., 2014). Although this mutation has not been functionally examined using Varroa mite sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes, insect sodium channels possess a proline at the corresponding position and the leucine substitution of proline in the cockroach sodium channel renders the cockroach sodium channel more sensitive to pyrethroids (Liu et al., 2006). Therefore, the L1596P mutation is predicted to make the Varroa mite sodium channel more resistant to pyrethroids. Since L1596P alone could confer pyrethroid resistance, P1596, located at the C-terminus of LIII/IV, likely has a more drastic allosteric effect on pyrethroid binding (to PyR1 and/or PyR2) than N1575Y.

The involvement of other intracellular linkers in pyrethroid resistance has also been reported. E435K and C785R, in the linker connecting domains I and II (LI/II), were identified in pyrethroid resistant German cockroach populations (Liu et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2014). As with N1575Y, E435K or C785R alone did not reduce sodium channel sensitivity to pyrethroids. However, concurrence of either E435K or C785R mutation with the kdr mutations, V1i19(410)M in IS6 or L2i16(1014)F in IIS6, significantly increases pyrethroid resistance (Liu et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2002b). A mechanism similar to that for N1575Y could explain the role of E435K or C785R in pyrethroid resistance. Another example is G1111 (in the cockroach sodium channel) in the second intracellular linker connecting domains II and III (LII/III), which is selectively involved in the response of sodium channels to type II pyrethroids, such as deltamethrin (Du et al., 2009). Deletion of G1111 (due to alternative splicing of cockroach sodium channel transcripts) makes cockroach sodium channels more resistant to type II pyrethroids. Interestingly, although the overall sequence of the intracellular linker is quite variable, the amino acid sequence around G1111 is highly conserved among insect sodium channels. Two conserved lysine residues K1118 and K1119 downstream from G1111 are also critical for the action of type II pyrethroids (Du et al., 2009). Neutralization of K1118 and K1119 confers resistance to type II pyrethroids. The precise mechanism through which these mutations selectively alter the interaction of sodium channels with pyrethroids remains unclear. It is possible that they alter the binding site for type II pyrethroids by an allosteric mechanism.

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the mechanism by which the N1575Y mutation enhances pyrethroid resistance and explains the molecular basis of the concurrence of N1575Y and L2i16(1014)F in pyrethroid-resistant mosquito populations. Furthermore, our findings provide evidence for possible allosteric, cross-domain interactions between transmembrane segments and intracellular loops of the sodium channel in mediating the action of pyrethroids on sodium channels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kris Silver for critical review of the manuscript. Computations were performed using the facilities of the Shared Hierarchical Academic Research Computing Network (www.sharcnet.ca).

Abbreviations

- AaNav

mosquito sodium channel

- kdr

knockdown resistance

- LIII/IV

cytoplasmic loop linking domains III and IV

- PyR

pyrethroid receptor site

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Wang, Zhorov, Dong.

Conducted experiments: Wang, Du, Nomura.

Performed data analysis: Wang, Du, Nomura.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Wang, Du, Liu, Zhorov, Dong.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medicine [Grant R01-GM057440]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [Grant R21-AI090303]; and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada [RGPIN-2014-04894].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Catterall WA. (2002) Molecular mechanisms of gating and drug block of sodium channels. Novartis Found Symp 241:206–218, discussion 218–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. (2012) Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol 590:2577–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Cestele S, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, Scheuer T. (2007) Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49:124–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K, Du Y, Rinkevich F, Nomura Y, Xu P, Wang L, Silver K, Zhorov BS. (2014) Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 50:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. (1998) The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Lee JE, Nomura Y, Zhang T, Zhorov BS, Dong K. (2009) Identification of a cluster of residues in transmembrane segment 6 of domain III of the cockroach sodium channel essential for the action of pyrethroid insecticides. Biochem J 419:377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Nomura Y, Satar G, Hu Z, Nauen R, He SY, Zhorov BS, Dong K. (2013) Molecular evidence for dual pyrethroid-receptor sites on a mosquito sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:11785–11790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enayati AA, Vatandoost H, Ladonni H, Townson H, Hemingway J. (2003) Molecular evidence for a kdr-like pyrethroid resistance mechanism in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Med Vet Entomol 17:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden DP, Zhorov BS. (2010) Docking flexible ligands in proteins with a solvent exposure- and distance-dependent dielectric function. J Comput Aided Mol Des 24:91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin AL. (2003) Mechanisms of sodium channel inactivation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13:284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Liyanapathirana M, Agossa FR, Weetman D, Ranson H, Donnelly MJ, Wilding CS. (2012) Footprints of positive selection associated with a mutation (N1575Y) in the voltage-gated sodium channel of Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:6614–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunaratne SHPP, Hawkes NJ, Perera MDB, Ranson H, Hemingway J. (2007) Mutated sodium channel genes and elevated monooxygenases are found in pyrethroid resistant populations of Sri Lankan malaria vectors. Pestic Biochem Physiol 88:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai S, Ng LC, Lam-Phua SG, Tang CS, Itokawa K, Komagata O, Kobayashi M, Tomita T. (2011) First detection of a putative knockdown resistance gene in major mosquito vector, Aedes albopictus. Jpn J Infect Dis 64:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada H, Higa Y, Komagata O, Kasai S, Tomita T, Thi Yen N, Loan LL, Sánchez RAP, Takagi M. (2009) Widespread distribution of a newly found point mutation in voltage-gated sodium channel in pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti populations in Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Baek JH, Lee W-J, Lee S-H. (2007) Frequency detection of pyrethroid resistance allele in Anopheles sinensis populations by real-time PCR amplification of specific allele (rtPASA). Pestic Biochem Physiol 87:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Scheraga HA. (1987) Monte Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:6611–6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA. (2005) Molecular modeling of local anesthetic drug binding by voltage-gated sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol 68:1611–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tan J, Huang ZY, Dong K. (2006) Effect of a fluvalinate-resistance-associated sodium channel mutation from varroa mites on cockroach sodium channel sensitivity to fluvalinate, a pyrethroid insecticide. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 36:885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tan J, Valles SM, Dong K. (2002) Synergistic interaction between two cockroach sodium channel mutations and a tobacco budworm sodium channel mutation in reducing channel sensitivity to a pyrethroid insecticide. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Valles SM, Dong K. (2000) Novel point mutations in the German cockroach para sodium channel gene are associated with knockdown resistance (kdr) to pyrethroid insecticides. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 30:991–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. (2005) Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science 309:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüleyap HU, Alptekin D, Kasap H, Kasap M. (2002) Detection of knockdown resistance mutations in Anopheles sacharovi (Diptera: Culicidae) and genetic distance with Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) using cDNA sequencing of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene. J Med Entomol 39:870–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Bergé JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D. (1998) Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol 7:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. (1996) Neuronal ion channels as the target sites of insecticides. Pharmacol Toxicol 79:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly AO, Khambay BPS, Williamson MS, Field LM, Wallace BA, Davies TGE. (2006) Modelling insecticide-binding sites in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochem J 396:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly AO, Williamson MS, González-Cabrera J, Turberg A, Field LM, Wallace BA, Davies TG. (2014) Predictive 3D modelling of the interactions of pyrethroids with the voltage-gated sodium channels of ticks and mites. Pest Manag Sci 70:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. (2011) The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 475:353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH. (2000) Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol 9:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich FD, Du Y, Dong K. (2013) Diversity and convergence of sodium channel mutations involved in resistance to pyrethroids. Pestic Biochem Physiol 106:93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra-Rodriguez K, Urdaneta-Marquez L, Rajatileka S, Moulton M, Flores AE, Fernandez-Salas I, Bisset J, Rodriguez M, McCall PJ, Donnelly MJ, et al. (2007) A mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene associated with pyrethroid resistance in Latin American Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol 16:785–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh OP, Dykes CL, Das MK, Pradhan S, Bhatt RM, Agrawal OP, Adak T. (2010) Presence of two alternative kdr-like mutations, L1014F and L1014S, and a novel mutation, V1010L, in the voltage gated Na+ channel of Anopheles culicifacies from Orissa, India. Malar J 9:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM. (2005) Sodium channels, in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science (Gilbert LI, Iatrou K, Gill SS, eds) pp 1–24, Elsevier, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Stump AD, Atieli FK, Vulule JM, Besansky NJ. (2004) Dynamics of the pyrethroid knockdown resistance allele in western Kenyan populations of Anopheles gambiae in response to insecticide-treated bed net trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg 70:591–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Liu Z, Nomura Y, Goldin AL, Dong K. (2002a) Alternative splicing of an insect sodium channel gene generates pharmacologically distinct sodium channels. J Neurosci 22:5300–5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Liu Z, Tsai TD, Valles SM, Goldin AL, Dong K. (2002b) Novel sodium channel gene mutations in Blattella germanica reduce the sensitivity of expressed channels to deltamethrin. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32:445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan WL, Li CX, Wang ZM, Liu MD, Dong YD, Feng XY, Wu ZM, Guo XX, Xing D, Zhang YM, et al. (2012) First detection of multiple knockdown resistance (kdr)-like mutations in voltage-gated sodium channel using three new genotyping methods in Anopheles sinensis from Guangxi Province, China. J Med Entomol 49:1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi H, Narahashi T. (1994) Differential mechanism of action of the pyrethroid tetramethrin on tetrodotoxin-sensitive and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS. (2007) Sodium channels: ionic model of slow inactivation and state-dependent drug binding. Biophys J 93:1557–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS. (2012) Architecture and pore block of eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channels in view of NavAb bacterial sodium channel structure. Mol Pharmacol 82:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood PNR, Davies TGE, Mellor IR, O’Reilly AO, Peng F, Vais H, Khambay BPS, Field LM, Williamson MS. (2007) Mutations in DIIS5 and the DIIS4-S5 linker of Drosophila melanogaster sodium channel define binding domains for pyrethroids and DDT. FEBS Lett 581:5485–5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vais H, Williamson MS, Goodson SJ, Devonshire AL, Warmke JW, Usherwood PNR, Cohen CJ. (2000) Activation of Drosophila sodium channels promotes modification by deltamethrin. Reductions in affinity caused by knock-down resistance mutations. J Gen Physiol 115:305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen K, Van Bortel W, Trung HD, Sochantha T, Keokenchanh K, Coosemans M. (2010) Knockdown resistance in Anopheles vagus, An. sinensis, An. paraliae and An. peditaeniatus populations of the Mekong region. Parasit Vectors 3:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijverberg HP, van der Zalm JM, van der Bercken J. (1982) Similar mode of action of pyrethroids and DDT on sodium channel gating in myelinated nerves. Nature 295:601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZM, Li CX, Xing D, Yu YH, Liu N, Xue RD, Dong YD, Zhao TY. (2012) Detection and widespread distribution of sodium channel alleles characteristic of insecticide resistance in Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in China. Med Vet Entomol 26:228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov BS, Tikhonov DB. (2004) Potassium, sodium, calcium and glutamate-gated channels: pore architecture and ligand action. J Neurochem 88:782–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.