Abstract

Chromatin Assembly Factor I (CAF-I) plays a key role in the replication-coupled assembly of nucleosomes. It is expected that its function is linked to the regulation of the cell cycle, but little detail is available. Current models suggest that CAF-I is recruited to replication forks and to chromatin via an interaction between its Cac1p subunit and the replication sliding clamp, PCNA, and that this interaction is stimulated by the kinase CDC7. Here we show that another kinase, CDC28, phosphorylates Cac1p on serines 94 and 515 in early S phase and regulates its association with chromatin, but not its association with PCNA. Mutations in the Cac1p-phosphorylation sites of CDC28 but not of CDC7 substantially reduce the in vivo phosphorylation of Cac1p. However, mutations in the putative CDC7 target sites on Cac1p reduce its stability. The association of CAF-I with chromatin is impaired in a cdc28–1 mutant and to a lesser extent in a cdc7–1 mutant. In addition, mutations in the Cac1p-phosphorylation sites by both CDC28 and CDC7 reduce gene silencing at the telomeres. We propose that this phosphorylation represents a regulatory step in the recruitment of CAF-I to chromatin in early S phase that is distinct from the association of CAF-I with PCNA. Hence, we implicate CDC28 in the regulation of chromatin reassembly during DNA replication. These findings provide novel mechanistic insights on the links between cell-cycle regulation, DNA replication and chromatin reassembly.

Keywords: Chromatin Assembly Factor I (CAF-I), Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 8 (CDK8), Cell cycle, Dbf4-Dependent Kinase (DDK), Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA)

Abbreviations

- CAF-I

Chromatin Assembly Factor I

- CAC1

the largest subunit of CAF-I

- PCNA

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen, POL30

- PIP

PCNA Interaction Peptide

- CDK

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase

- Cdc28p

- DDK

Dbf4-Dependent Kinase, Cdc7p-Dbf4p

- TPE

Telomere Position Effect

Introduction

Chromatin Assembly Factor I (CAF-I) is a histone chaperone that plays a central role in the reassembly of nucleosomes after the passage of replication forks.1,2 It receives “old” H3/H4 histones from the disassembled nucleosomes plus newly supplied histones from another histone chaperone, ASF1. It is believed that the CAF-I/ASF1-mediated feedback from the “old” nucleosomes warrants the preservation of histone marks and the epigenetic transmission of the chromatin state.2

It is believed that CAF-I is recruited to replication forks via contacts with PCNA (Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen, POL30), the DNA replication sliding clamp.3-6 Mutations in POL30 or CAC1 (which encodes the largest subunit of CAF-I) that cripple their interaction in vitro also impair the assembly of chromatin in vitro3,7 and show gene silencing defects in vivo.7–10 However, the mechanisms that regulate the association of CAF-I with PCNA and with chromatin are poorly understood. Many PCNA-interacting proteins share a PIP (PCNA Interaction Peptide) consensus. Two PIPs are present in the largest CAF-I subunit in humans, but only one in S.cerevisiae.3 The S.cerevisiae PIP in Cac1p is required for the interaction with PCNA.7 An additional PIP is found in the Cac2p subunit of CAF-I in both species, but this PIP alone does not confer binding to PCNA.3

CAF-I is phosphorylated in vivo,11 however the identity of the kinases and the consequences of its phosphorylation are not certain. Inhibitors of Protein Phosphatase 1 or of CDK2 kinase reduce the CAF-I driven assembly of nucleosomes in human cell extracts, but these effects cannot be directly attributed to the phosphorylation of CAF-I.12 Another in vitro experiment has shown that the phosphorylation of the largest subunit of the human CAF-I (p150) by the Cdc7-Dbf4 kinase, but not by CDK2, promoted its binding to PCNA.6 It remains unclear if Cdc7-Dbf4 regulates the association of CAF-I with chromatin and PCNA in vivo. Therefore, the precise regulation of CAF-I by protein kinases remains poorly understood.

Two kinases, Cdc7p-Dbf4p (Dbf4-Dependent Kinase, DDK) and Cdc28p (a homolog of Cdk2, hereafter referred to as CDK), play distinct critical roles during S phase in S.cerevisiae.13 Both kinases are essential and regulate key events at the onset of DNA replication that coincide with the presumed loading of CAF-I on replication forks.14 In the present study we have embarked on a detailed investigation of the phosphorylation of Cac1p by these two kinases. Our results strongly suggest that CDK is the key Cac1p kinase and regulates the association of CAF-I with chromatin.

Results

CDK is the main Cac1p-kinase in vivo

To address the roles of DDK and CDK in the regulation of CAF-I, we analyzed the phosphorylation of Cac1p in wild type, cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 mutant strains, which harbor a MYC-tagged genomic copy of CAC1. Extracts were prepared by boiling the cells in 8 M Urea/4% SDS. The phosphorylation state of Cac1p was assessed by a PhosTagTM gel retardation assay.15,16 Briefly, in the presence of Mn2+ or Zn2+ the PhosTagTM ligand associates with phosphopeptides and retards their mobility in SDS-PAGE.16 In Fig. 1A (lanes 1–3) we show that the mobility of Cac1p shifts in the presence of PhosTagTM and that this shift is abolished by treatment with phosphatase. The PhosTagTM retardation assays showed no substantial differences between wild type (W303), cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 cells at the permissive temperature of 23°C (Fig. 1A, lanes 4–7). When cells were shifted to 37°C, the low-mobility Cac1p band disappeared in cdc28–1 cells, but remained unchanged in the cdc7–1 and wild type cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 8–11). While these results shed some doubt on whether Cdc7p phosphorylates Cac1p in vivo, they clearly suggested that Cdc28p could be such a kinase.

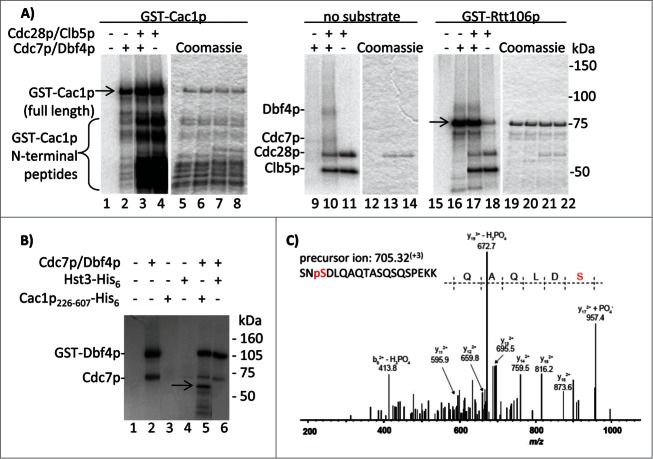

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of Cac1p in cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 mutants. (A) Cac1p-MYC18 was immunoprecipitated from wild type (W303) cell extracts. The samples were treated without (lanes 1, 2) or with lambda phosphatase (lane 3) and run on separate 6.5% SDS-50 μM PhosTagTM-polyacrylamide gels containing or not 100 μM MnCl2 as indicated. In the left-hand panel the cells shown above the lanes were grown at 23°C (lanes 4–7) and then shifted to 37°C for one hour (lanes 8–11) before extracts were prepared by boiling in Laemmli buffer. All samples were analyzed Western blotting with anti-MYC antibody. “- P-” indicates the mobility of the phosphorylated Cac1p-MYC. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Cells were arrested with α-factor for 3 hours at 23°C, moved to fresh YPD medium for 20 min and then split and grown for 30 min at 23°C and 37°C, respectively. Samples were taken out at the indicated times and analyzed by FACS. Cells arrested in M-phase with Nocodazole (M) show 2c content. Numbers 1–12 indicate the samples corresponding to the lanes in C. Left-pointing arrows highlight the 23°C and 37°C 30 min samples for comparison. (C) Samples were taken out from the cultures at the indicated time points after α-factor arrest, separated in SDS-7.5% polyacrylamide gels containing 60 μM PhosTagTM and 120 μM ZnCl2 and analyzed by Western blotting. Densitometry graphs of lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12 were acquired with ImageJ and are shown underneath the lanes. P and arrows indicate the phosphorylated Cac1p-MYC. One of 2 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown.

It is known that the exposure of both the cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 strains to 37°C leads to the accumulation of cells in G1/S phase.17,18 Hence, the lack of Cac1p phosphorylation in cdc28–1 could reflect the G1/S arrest and not necessarily the loss of the CDK activity. Conversely, the lack of effect in cdc7–1 cells could be due to slow progression through S phase,17 which could be past the point of Cac1p phosphorylation by DDK. To address these issues, we synchronized W303, cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 cells in G1 with α-factor for 3 hours, released them toward S phase and then shifted half of the cultures to 37°C for 30 min. This treatment is expected to inactivate DDK and CDK in S phase. Aliquots of the cultures were collected and analyzed by FACS (Fig. 1B) and by the PhosTagTM retardation assays (Fig. 1C). The samples from the G1-synchronized cells and the samples collected 20 min after the release displayed mostly unphosphorylated Cac1p (Fig. 1C). The samples that were incubated at 23°C for an additional 30 min displayed significant levels of Cac1p phosphorylation in all 3 strains (Fig. 1C, lanes 3, 7, 11). These results clearly show that Cac1p is not phosphorylated in G1 and that under permissive conditions the cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 alleles do not preclude its phosphorylation in S phase. Importantly, at 37°C there was an approximate 2-fold decrease in the phosphorylation of Cac1p in cdc28–1 as compared to wild type and cdc7–1 cells (Fig. 1D, lanes 4, 8, 12). It is unlikely that this decline in cdc28–1 at 37°C is caused by cell cycle effects because the cell cycle distribution of the cdc28–1 cultures at 23°C and 37°C is very similar (Fig. 1C, lanes 11–12). We concluded that the loss of Cac1p phosphorylation in cdc28–1 cells is caused by the inactivation of Cdc28p rather than an arrest in G1 phase.

Identification of CAF-I phosphopeptides

It has been demonstrated that the human homolog of Cac1p (p150) is a substrate of DDK.6 The persistence of Cac1p phosphorylation in cdc7–1 cells (Fig. 1B and D) raised the possibility that, unlike its human counterpart, the budding yeast Cac1p is not phosphorylated by DDK. Moreover, it is not known if the yeast Cac1p is phosphorylated by CDK. To resolve these questions we affinity-purified CAF-I as previously described.19 Using mass-spectrometry, we identified 6 phosphopeptides in this complex. Five of them were located in the Cac1p subunit (Fig. 2; Fig. S1). Some of these are also found as entries IN proteome databases (http://phosphopep.org). Unexpectedly, no phosphorylation site was found in Cac2p, the homolog of CAF-1 p60 that is extensively phosphorylated in humans (Fig. 2).12,20 Interestingly, 4 of the Cac1p phosphorylation sites identified in vivo conform to either CDK (SP) or DDK target sites (SD).

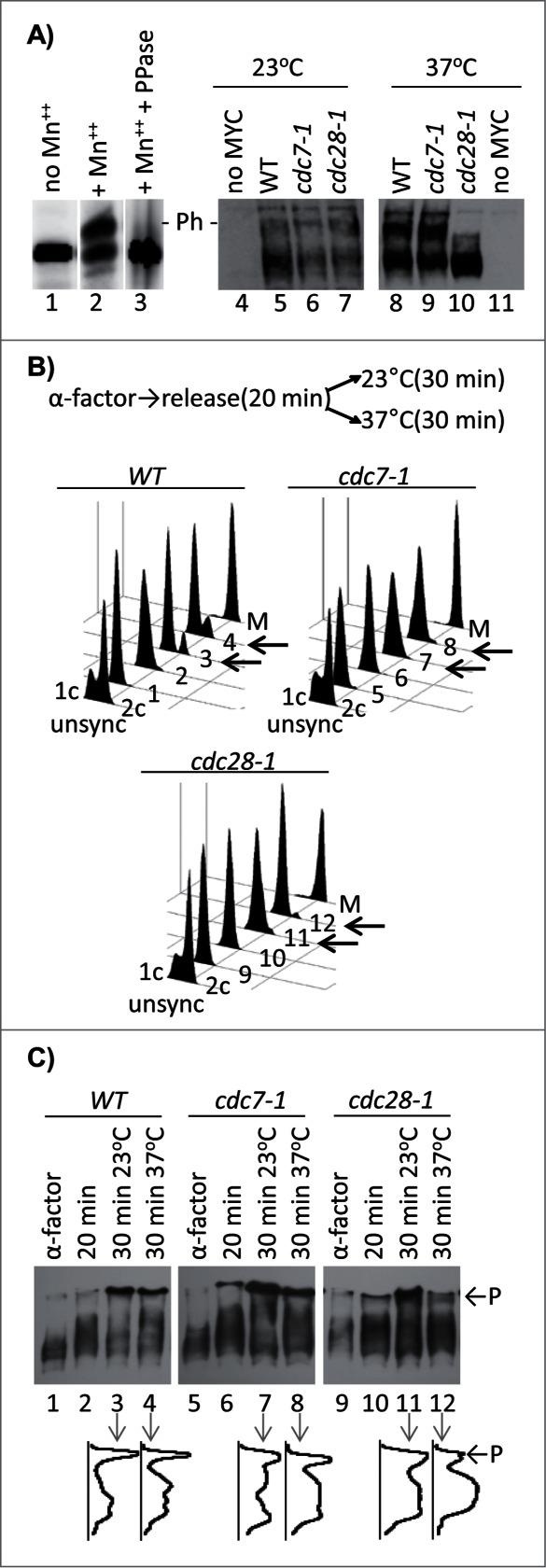

Figure 2.

Sequence coverage and phosphopeptides identified in the 3 polypeptide subunits of CAF-I. The amino acids in bold were all part of the sequence coverage. The identified phosphorylated residues are underlined. Although some peptides contain more than one phosphorylated residue, only singly phosphorylated peptides were identified.

In vitro phosphorylation of Cac1p by CDK and DDK

To test if Cac1p is directly phosphorylated by these kinases, we performed in vitro assays with recombinant DDK, CDK (Cdc28p-Clb5p) and GST-Cac1p. We chose Clb5p, as opposed to other cyclins, because the form of CDK containing Clb5p phosphorylates several proteins during S phase.21 Parallel reactions with GST-Rtt106p, which we have recently identified as a DDK target, were also conducted. The assays show that both kinases phosphorylate GST-Cac1p (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4) and that DDK and CDK do not cooperate on this substrate in vitro (Fig. 3A, lane 3) as previously shown for other substrates.22,23 Importantly, the 2 kinases exhibit distinct phosphorylation patterns on GST-Cac1p. Our preparations contain full length GST-Cac1p and several shorter peptides, which were presumably generated by C-terminal truncations 5 and were pulled out by the GST tag attached to the N-terminus (Fig. 3A, lanes 5–8). CDK efficiently phosphorylates many of these shorter peptides presumably because they retain the Cdc28p target sites. Consistent with this interpretation, one in vivo phosphorylated SP site on Cac1p is S94. In contrast, DDK clearly prefers the full-length protein. None of the shorter bands are products of auto-phosphorylation as they are not present in the kinase reactions lacking the substrate (Fig. 3A, lanes 9–11). GST-Rtt106p is phosphorylated by DDK, but to a far lesser extent by CDK (Fig. 3A, lanes 16, 18), further strengthening the notion that the observed activity of CDK is not caused by non-specific contaminating kinases. Hence, it is apparent that CDK phosphorylates Cac1p in its N-terminal segment, but other target sites closer to the C-terminus cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, it seems that DDK phosphorylates Cac1p at a position(s) away from its N-terminus. We revisited this issue by assays with a N-terminally truncated Cac1p226–606-His6 substrate. As shown in Fig. 3B, this fragment retains the DDK phosphorylation site(s). After repeating the kinase reactions with cold ATP, the products were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Consistent with the in vivo phosphorylation data (Fig. 2), a phosphopeptide corresponding to the phosphorylation of Cac1p-S503 was detected (Fig. 3C). The experiments in Fig. 3A and B were conducted with DDK that was prepared independently in 2 different laboratories. The fact that they agree on the site of phosphorylation being in the central/C-terminal portion of the protein adds to the credibility of our conclusion.

Figure 3.

In vitro phosphorylation of Cac1p by Cdc7p/Dbf4p and Cdc28p/Clb5p kinases. (A) GST-Cac1p or GST-Rtt106p were mixed with His6-Cdc7p/Dbf4p, GST-Cdc28p/Clb5p or both (indicated above the lanes) in the presence of 32P-γATP and the reaction products were resolved through 4–20% polyacrylamide gels. Full length GST-Cac1p and GST-Rtt106p are shown by arrows. The positions of His6-Cdc7p, Dbf4p, GST-Cdc28p and Clb5p are also indicated. One of 2 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown. (B) Cac1p226–606-His6 or Hst3-His6 were incubated with Cdc7p/Dbf4p in the presence of 32P-γATP. The reaction products were resolved through an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. The position of Cac1p226–606-His6 is shown by the arrow. The 2 radiolabeled bands in lane 2 (a kinase reaction with no substrate) are generated by auto-phosphorylation of Cdc7p/Dbf4p. (C) Cac1p226–606-His6 was incubated with Cdc7p/Dbf4p and cold ATP. Reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie. The Cac1p226–606-His6 band was digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The experimental and theoretical masses of the non-fragmented peptide are indicated. The y172+ + PO4− fragment at m/z = 957.4 demonstrates the presence of Cac1p phosphorylation at S503.

Mutations of the CDK-target sites of Cac1p preclude its in vivo phosphorylation and its association with chromatin

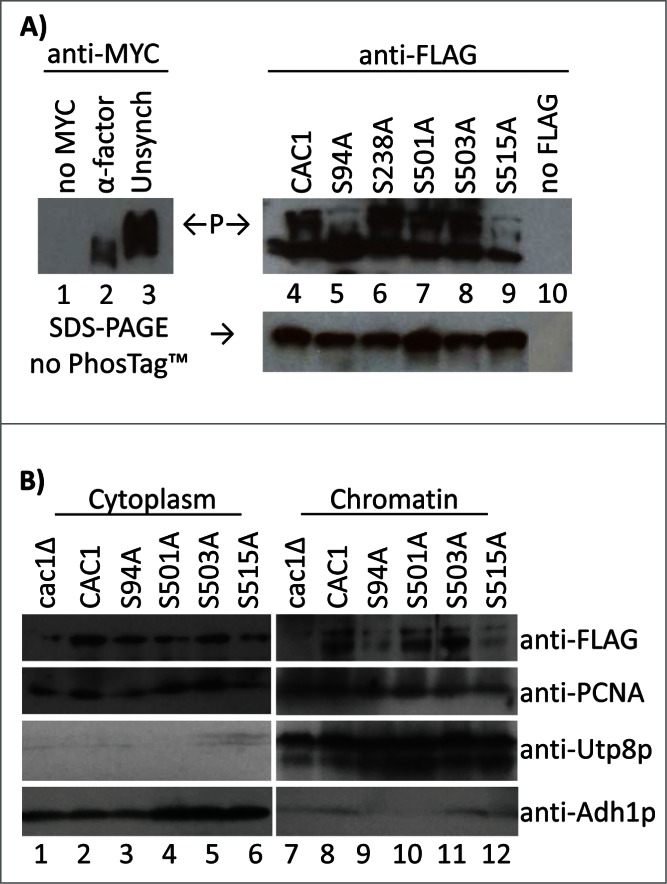

We tested the significance of the identified phosphorylation sites. S94 and S515 match the S/TP consensus for CDK while S238 and S503 conform to the DDK consensus site (S/T adjacent to D/E).22,23 S501 is not adjacent to P or D/E and the nature of its kinase is hard to predict. FLAG-tagged S→A point mutants at these positions were prepared and expressed from low copy pRS315 plasmids in cac1Δ cells. The introduction of the mutants caused no cell cycle disturbances in these cells as determined by FACS (not shown).

First, we employed the PhosTagTM assay to assess the contribution of these serines to the phosphorylation of Cac1p in vivo. The mobility of the FLAG-tagged proteins was compared to that of Cac1p-MYC in α-factor synchronized cells (unphosphorylated Cac1p) and to the slower moving forms in non-synchronised cells (Fig. 4A). Similarly to Cac1p-MYC in cdc28–1 cells at 37°C (Fig. 1B), the slowly migrating forms of Cac1p were substantially depleted in cells expressing either Cac1p-S94A or Cac1p-S515A (Fig. 4A). It is interesting that a mutation at either of these sites was sufficient to preclude the accumulation of slower bands. This observation suggests that the inability to phosphorylate one of these residues precludes the phosphorylation of the other. Alternatively, the phosphorylation of both S94 and S515 may be necessary for the retardation by PhosTagTM. This interpretation suggests that the PhosTagTM assay may miss single phosphorylations and that the fast migrating bands in Fig. 1 and Fig. 4A may retain some degree of phosphorylation. This notion does not alter our main conclusion: the S94A and S515A mutations recapitulate the effect of Cdc28p inactivation. In contrast, S238A, S501A or S503A do not abolish the presence of the slowly migrating forms of Cac1p.

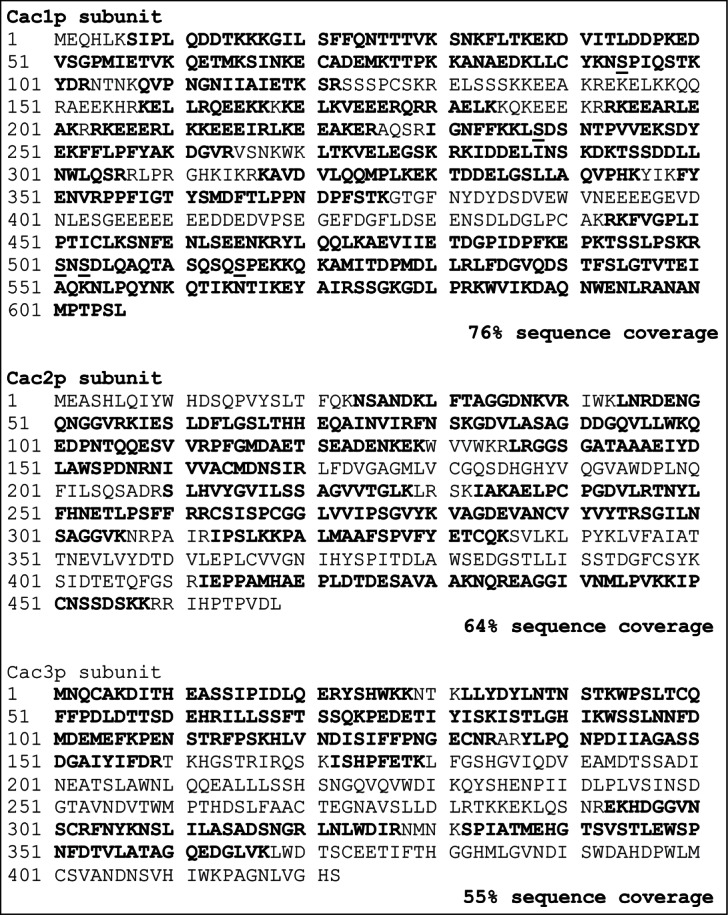

Figure 4.

Cac1p-S94A and Cac1p-S515A reduce the association of Cac1p with chromatin. (A) Cells with a MYC-tagged genomic copy of CAC1 (lanes 1–3) or cac1Δ cells with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged Cac1p with no mutation (CAC1), lane 4, the indicated point mutations (lanes 5–9) or empty plasmid (lane 10) were analyzed by the PhosTagTM retardation assay as inFig. 1. “P” and arrows indicate the mobility of the phosphorylated Cac1p-MYC (left) and Cac1p-FLAG (right). A parallel Western blot without PhosTagTM is shown beneath. One of 2 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown. (B) Spheroplasts from cac1Δ cells with plasmids for the expression of FLAG-tagged Cac1p were lysed and spun to obtain the cytoplasm fractions (lanes 1–6) and chromatin pellets (lanes 7–12). All samples were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG, anti-PCNA, anti-Utp8p and anti-Adh1p antibodies. Utp8p and Adh1p represent the purity of the chromatin and cytoplasm fractions, respectively. One of 2 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown.

We also tested the role of these residues in the association of Cac1p with chromatin. We used a modified routine protocol for preparation of chromatin.24,25 Briefly, spheroplasts from cells expressing Cac1p-FLAG mutants were gently lysed and centrifuged. The supernatant was designated as “cytoplasm.” The pellet was washed, re-spun through a cushion of 30% sucrose and designated as “chromatin.” The purity of these 2 fractions was confirmed with anti-Utp8p (a nucleolar protein) and anti-Adh1p (a cytosolic protein). The abundance of Cac1p-FLAG in chromatin relative to PCNA was assessed by Western blotting. These assays demonstrated that Cac1p-S94A and Cac1p-S515A poorly bind to chromatin while Cac1p-S501A and Cac1p-S503A had no effect (Fig. 4B). In these chromatin fractionation experiments the S238A mutant showed some level of instability that led to irreproducible results. Therefore we could not assess the contribution of this mutation to the binding of CAF-I to chromatin. Nevertheless, we can conclude that the mutations that preclude the phosphorylation of Cac1p by CDK also strongly reduce its association with chromatin.

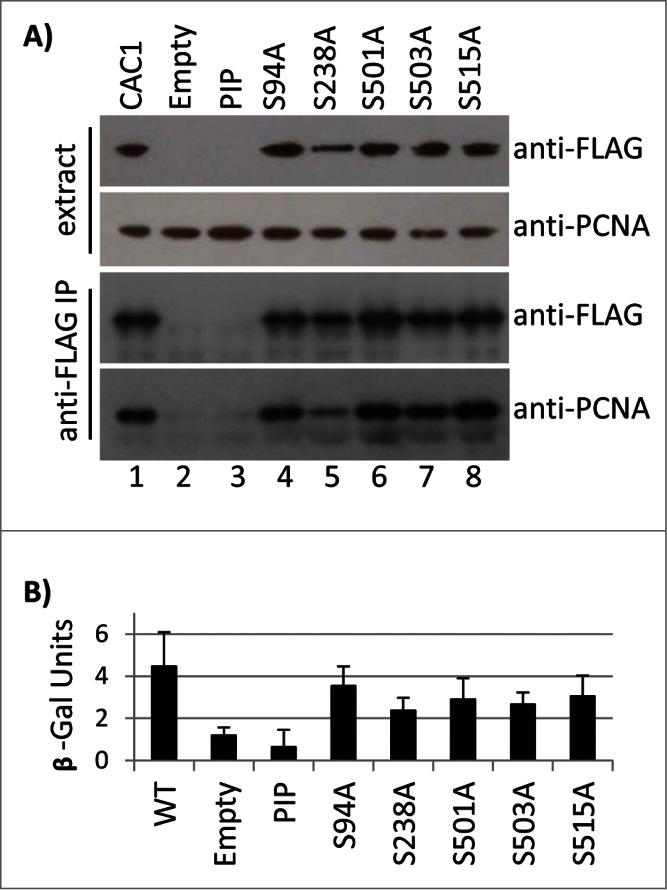

Phosphorylation of Cac1p by CDK does not affect its binding to PCNA

We also tested the effects of these Cac1p mutations on its association with PCNA. Total cell extracts were prepared by bead beating and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies. None of the S→A mutations abolished the interaction with PCNA (Fig. 5A). The S238A mutation slightly decreased the amount of the immunoprecipitated PCNA, but the key Cac1p-PIPΔ control turned out to be unstable in vivo and did not provide the necessary baseline for comparison (Fig. 5A). For this reason we employed an alternative in vivo assay for PCNA-interacting proteins.26 Briefly, PCNA-GAL4 and wild type or mutant LexA-Cac1p proteins were expressed in cac1Δ cells that harbor a LexAop-driven β-galactosidase reporter. The β-galactosidase activity in extracts represents the strength of the PCNA-Cac1p binding. As shown in Figure 5B, the S→A mutations failed to significantly alter the PCNA-Cac1p binding, while the removal of PIP abolished this interaction. Again, the S238A mutation displayed a modest but statistically significant decline as compared to the other mutations. Importantly, we saw no correlation between the loss of Cac1p phosphorylation, its association with chromatin (Fig. 4) and its reduced association with PCNA (Fig. 5). Thus, it is conceivable that CDK does not regulate the interaction of PCNA and Cac1p, but regulates some other pathway by which Cac1p is recruited to chromatin.

Figure 5.

The Cac1p S→A mutations do not reduce the binding of Cac1p to PCNA. (A) Total cell extracts from cac1Δ cells expressing FLAG-tagged Cac1p plasmids with no mutation (CAC1, lane 1), empty vector (lane 2) or the indicated point mutations (lanes 3–8) were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies (labeled as anti-FLAG IP). The samples were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG and anti-PCNA antibodies. One of 2 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown. (B) A LexAop-driven β-galactosidase reporter plasmid was co-transformed in cac1Δ cells with plasmids expressing LexA-Cac1p with no mutation (CAC1) or the indicated point mutations and a plasmid expressing PCNA-Gal4AD. Average β-galactosidase activity in total cell extracts from 2 independent experiments (3 biological replicates each) was measured and plotted.

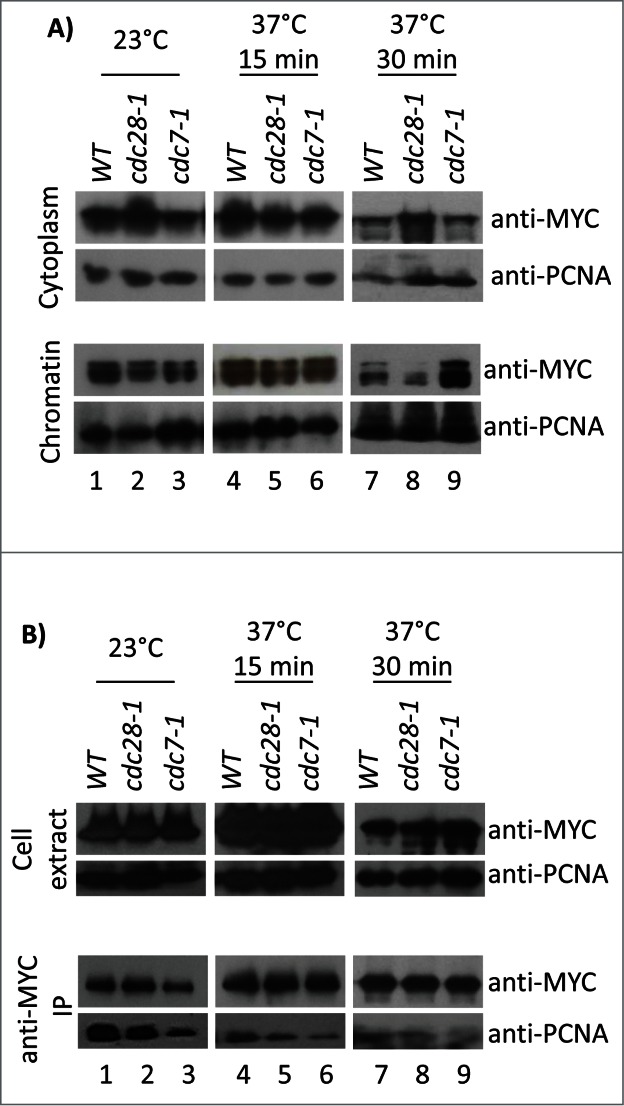

Association of Cac1p with chromatin or PCNA in conditional cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 mutants

At present, Cac1p-S503 is the only confirmed target of DDK in S.cerevisiae. At the same time, in human cell extracts DDK promotes the association of p150 (Cac1p) with PCNA.6 The fact that the S503A did not impair the binding of Cac1p to chromatin or PCNA raises an intriguing question. Our results could reflect the inability of the employed assays to detect in vivo effects by DDK. Alternatively, the prevention of phosphorylation at S503 may not preclude the binding of Cac1p to chromatin or PCNA. Also, other serines (for example S238) could be transiently targeted by DDK, but are not revealed in these assays. Finally, it is possible that the yeast DDK is not involved in the regulation of CAF-I.

We addressed these uncertainties by testing the binding of Cac1p to chromatin and PCNA in conditional cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 mutants. The strains were grown at 23°C and then shifted for 15 or 30 min to 37°C. Cytoplasm and chromatin fractions were prepared as in Fig. 4B and the abundance of Cac1p-MYC relative to PCNA was assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 6A) followed by densitometry analysis (Supplemental Fig. 2). After 15 min at 37°C wild type, cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 displayed comparable amounts of chromatin-associated Cac1p (Fig. 6A, lanes 4–6). However, after 30 min at 37°C a 2.6-fold decrease (relative to wild type) of chromatin-associated Cac1p and a corresponding increase in the cytoplasm fraction were seen in cdc28–1 cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 7–9). In contrast, in cdc7–1 cells there was actually a modest 1.6-fold increase in chromatin-associated Cac1p (Fig. 6A, lane 18). We have shown that short exposures to restrictive temperature do not cause major cell cycle redistribution in these mutants (Fig. 1C). Therefore, it seems unlikely that cell cycle effects cause the specific loss or gain of chromatin-bound Cac1p in cdc28–1 or cdc7–1 cells, respectively.

Figure 6.

Association of Cac1p with chromatin and PCNA in cdc7–1 and cdc28–1 cells. (A) Cells were grown at 23°C and then shifted to 37°C for 15 min or 30 min. Cytoplasm and chromatin fractions were prepared as in Figure 3B. One of 4 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown. (B) Cell cultures were grown as in A) and disrupted with glass beads to obtain cell extracts that were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC antibodies. One of 3 independent experiments with reproducible outcomes is shown. All samples were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-MYC and anti-PCNA antibodies as indicated. Equal loading was confirmed by staining the membranes with India ink.

For the analysis of the Cac1p-PCNA interaction, cells were shifted to 23°C or 37°C, as in Fig. 6A, disrupted with glass beads and spun to obtain total cell extracts. Co-immunoprecipitation assays reproducibly showed 1.7 to 2.2-fold decrease (relative to wild type) in PCNA bound to Cac1p in the cdc7–1 strain at both permissive and restrictive temperatures (Fig. 6B, lanes 3, 6, 9). In the cdc28–1 strain, the PCNA-Cac1p interaction was not altered at 23°C, but at 37°C the Cac1p-bound PCNA decreased to about 1.5-fold (Fig. 6B, lanes 2, 5, 8). These results indicate that both CDC7 and CDC28 affect the interaction between Cac1p and PCNA in vivo. However, they do not address if this regulation is direct or indirect. Again, the data in Figures 4–6 show little correlation in the association of Cac1p with chromatin and PCNA, which supports the notion that the recruitment of CAF-I to chromatin involves a process that is partially independent of PCNA.

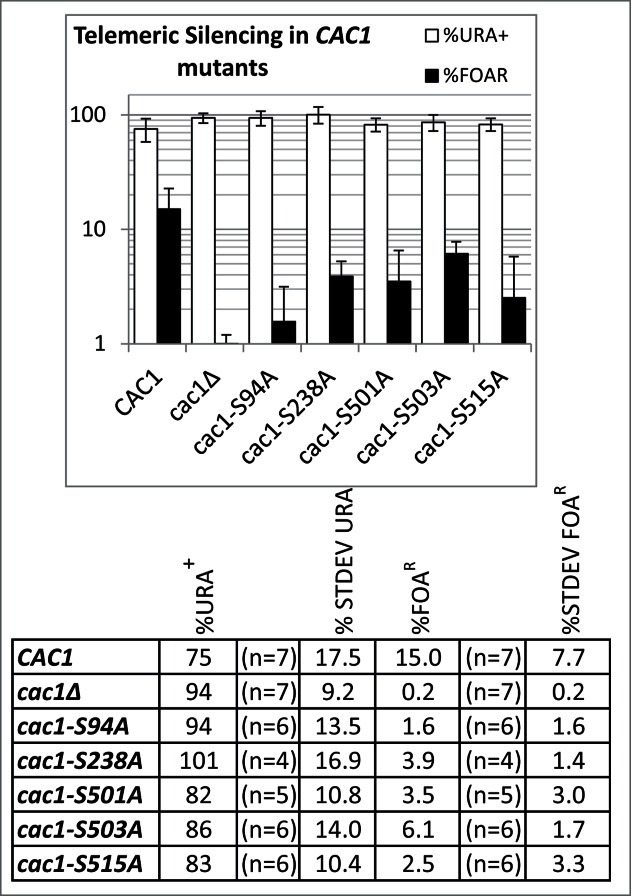

Mutations of the serines targeted by CDK and DDK reduce telomeric gene silencing

The deletion of CAC1 is known to cause sensitivity to DNA damaging agents,7,27 loss of telomeric gene silencing,4,5 decrease in the frequency of epigenetic conversions at telomeres28 and impaired in vitro replication-coupled nucleosome assembly.5,29 However, point mutations in Cac1p that affect its interaction with PCNA do not phenocopy the loss of CAC1.7 We sought to determine how the mutations in Cac1p phosphorylation sites affect the outcome in these functional assays.

The analysis of Telomere Position Effect (TPE) and the frequency of epigenetic conversions were conducted exactly as in.28 These assays showed the all S→A mutants reduced the repression of a telomeric URA3 reporter 2- to 9-fold relative to wild type cells (Fig. 7) with S503A and S94A showing the weakest and strongest effect, respectively. However, none of the mutations reproduced the 100 fold reduction of gene silencing observed in the cells without CAC1 (Fig. 7). None of the mutations altered the frequency of epigenetic conversions (not shown). The plasmids expressing wild type or mutant Cac1p were also introduced in cac1Δhir1Δ cells (these display an increased sensitivity to DNA damage as compared to single cac1Δ mutants30) and sensitivity to UV (100 J/m2) or methyl methane sulphonate (MMS, 0.01%) was assessed. These experiments indicated that the mutations did not increase the sensitivity to DNA damage (not shown). We have also tested the nucleosome assembly activity of CAF-I in whole cell extracts. In agreement with earlier studies31 the deletion of cac1 alone or in combination with the deletion of hir1 or asf1 had little effect on the capacity of such extracts to assemble nucleosomes (not shown). While these results were in agreement with the notion of a redundancy of nucleosome assembly in vitro,28,32,33 they precluded the analysis of the Cac1p S→A mutants.

Figure 7.

Telomere Position Effect in cac1(S→A) mutants. URA3 was inserted in the VIIL telomeres of cac1Δ cells supplemented with the plasmids shown underneath the graphs. The cells were selected on SC/-ura-leu. Single colonies were transferred to liquid SC/-leu medium and grown for about 15–20 generations. The cultures were serially (1:10) diluted and spotted on SC/-leu, SC/-leu-ura and SC/-leu+FOA plates. The colonies were counted and the average percent of URA+ (open columns) and FOAR (black columns) cells were calculated for the number of colonies shown in the table below and plotted. Error bars reflect the standard deviations shown in the table.

In summary, mutations in the sites of phosphorylation by CDC7 and CDC28 displayed moderate TPE phenotypes. Hence, each of these phosphorylation events is necessary, but not sufficient to support the function of CAF-I in gene silencing. The lack of effect in the DNA damage assays and the in vitro chromatin assembly assays could indicate that these 2 kinases are not involved in this aspect of the activity of CAF-I or that the assays are not sensitive enough to detect moderate loss of function.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that CDK phosphorylates Cac1p on S94 and S515. These phosphorylation events take place during the G1/S transition and/or early S phase and regulate the association of Cac1p, and presumably CAF-I, with chromatin. Although this timing coincides with the activation of early origins of DNA replication, the phosphorylation of S94 and S515 does not seem to directly regulate the interaction of CAF-I with PCNA and presumably with the replication forks. We postulate that there is a CDK-dependent step in the recruitment of CAF-I to chromatin that is distinct from the PCNA-controlled step. In support of this idea, we and others have reported an incomplete overlap in the in vivo effects of mutations that impair the interaction between PCNA and Cac1p, and the deletion of CAC1 itself.5,7,28

While this study highlights the role of CDC28 as a direct regulator of CAF-I, it sheds some uncertainty on the role of CDC7. In human cell extracts DDK acts as a regulator of the PCNA-CAF-I association.6 We did not obtain strong support for this model by our in vivo studies in S.cerevisiae. We have confirmed that DDK phosphorylates Cac1p in vitro and have identified S503 as a target of this kinase, but we failed to show a functional consequence of this phosphorylation. Hence, the question of whether and how DDK regulates CAF-I in S.cerevisiae remains unanswered. Genome-wide proteome studies have pointed to 13 phosphorylation sites on this peptide.11 Some of these sites conform to the preferred DDK targets of S/T residues adjacent to D.37-36 In particular, the serine at position 238 could be such a target. Because of technical issues we could not fully assess the contribution of the S238A mutation to the control of CAF-I. It is possible that DDK transiently phosphorylates S238 and in conjunction with S503 could influence its activity or stability. Even more, in addition to the largest subunit of CAF-I, DDK phosphorylates many other substrates. These are involved in the regulation of the cell cycle, of replication fork stalling, of DNA damage and of meiosis.13,23,37–41 Some of these processes could directly or indirectly affect the activity, the association partners and/or the turnover of CAF-I. In summary, our data does not contradict the model that DDK regulates the PCNA-Cac1p interaction.6 However, we believe that this model only partially depicts the complex relationship between CAF-I and DDK.

What are the consequences of the phosphorylation of Cac1p by CDK and DDK? The answer to this question is hampered by the moderate phenotypes caused by the destruction of histone chaperones.9,28,32,42 For example, our experiments could not reveal if CDK affects the nucleosome assembly activity of CAF-I because the destruction of CAF-I alone or in conjunction with other histone chaperones seems to have little effect. Therefore, the issue of whether CAF-I is regulated by activation or simply by recruitment remains to be addressed. Similarly, the redundancy of chaperone function is also likely to contribute to the lack of effects of the S→A mutations on sensitivity to DNA damage. At present we do not rule out a link between CAF-I phosphorylation and its function in DNA repair. In particular, CDC7 is known to be involved in DNA repair.43 It is possible that a temporal phosphorylation of Cac1p by CDC7 could contribute to the response to DNA damage, but this effect is tied to other CDC7 regulated events. The only detectable consequence of the mutations in the kinase target sites was a reduction in telomeric gene silencing (Fig. 7). Although the effects do not phenocopy the deletion of CAC1, the experiments clearly point to the involvement of both CDC7 and CDC28, with the CDC28 phosphorylation sites having a more prominent role. It is apparent that the phosphorylations by CDK and DDK are necessary, but not sufficient to confer strong TPE phenotypes. Hence, the 2 kinases are true regulators of the activity of CAF-I.

It is well established that the ablation of CAC1 causes de-repression of sub-telomeric genes. However, an earlier study has pointed out that mutations in CAC1 that affect its binding to PCNA (cac1–13 and cac1–20) only mildly disturb the telomere position effects.7 Now we add that mutations that affect the binding of CAF-I to chromatin also have minor consequences. Together, these observations show a level of complexity in the control of telomere position effects by CAF-I that we do not understand. It is tempting to speculate that the undisturbed telomere position effects are a result of a redundancy in the recruitment of CAF-I by a PCNA-dependent mechanism driven by DDK and a PCNA-independent mechanism driven by CDK. The investigation of this possibility is beyond the scope of this study.

In this study we point to a direct role of CDC28 in the phosphorylation of the Cac1p subunit of CAF-I and its loading to chromatin. We implicate CDC28 in the regulation of chromatin assembly during DNA replication. This novel role for CDK broadens the scope of its effects as a master-regulator of the cell cycle. We also point to a possible redundancy of a DDK/PCNA-regulated and a CDK-regulated steps for the association of CAF-I with chromatin.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The experiments with W303 and the isogenic cdc7–1 or cdc28–1 strains were routinely conducted in YPD at 23ºC. For temperature shift assays, cell cultures were grown to OD600 = 1.0, split in halves, centrifuged and resuspended in pre-warmed YPD medium for the lengths of time indicated in the Figure legends. The cultures then received 0.1% NaN3 to prevent cell growth. The cac1Δ cells (BY4742) carrying plasmids for the expression of Cac1p-FLAG point mutants were routinely grown at 30°C in synthetic complete media lacking Leucine (SC-Leu).

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source of strains |

|---|---|---|

| W303 | MATa cac1::MYC18::KanMX ade2–1 his3–11,15 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 ura3–1 can1–100 | Open Biosystems |

| cdc7–1 | MATa cdc7–1 cac1::MYC18::KanMX ade2–1 his3–11,15 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 ura3–1 can1–100 TS at 37°C | YB55647, |

| cdc28–1 | MATa cdc28–1 cac1::MYC18::KanMX ade2–1 his3–11,15 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 ura3–1 can1–100 TS at 37°C | DBY25718 |

| BY4742 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

| cac1Δ | MATa cac1::KanMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

Plasmids

The plasmids for the expression of GST-Cac1p and GST-Rtt106p were generated by amplifying the open reading frames of CAC1 and Rtt106 from W303 genomic DNA and cloning them in pGEX2T. The plasmid for the expression of Cac1p226–607-His6 was created by inserting a PCR fragment between the NcoI and NotI sites of pET28b. The plasmids for ectopic expression of Cac1p were created by amplifying a 2.1 kb fragment containing the CAC1 promoter and the open reading frame fused to 3 FLAG epitopes and cloning it in pRS315(ARS CEN6 LEU2) plasmid. The plasmid expressing LexA-Cac1p was made by cloning of the CAC1 ORF in frame to LexA in pEG202 (HIS3, 2 μm, LexABD). The GAL4AD-PCNA expressing plasmid pBL240 (LEU2, 2 μm, Gal4AD::POL30) and the reporter pSH18–34 (URA3, 2 μm, 8xLexAop-lacZ) have been described in.44 The cac1(S→A) and PIP mutant plasmids were generated using the protocol of.45 All plasmids were sequenced to verify that there were no PCR-induced mutations.

Expression of recombinant proteins

The GST-Cac1p and GST-Rtt106p substrates were expressed in BL21(DE) cells. The cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors (Sigma) and the extracts were loaded on Glutathione-Sepharose columns. Elution was with 10 mM Glutathione. The proteins were moved to Kinase Buffer using PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare) and aliquots were frozen and stored at −80°C. The Cac1p226–606-His6 and Hst3-His6 substrates were expressed from pET28 vectors in ArcticExpress (DE3)RIL cells and extracts were directly used in kinase assays. For LC-MS/MS analyses Cac1p226–607-His6 was bound to Ni-NTA Agarose, washed and recovered for in-solution trypsin digestion. The kinase complexes (GST-Cdc28p/Clb5p and His6-Cdc7p/Dbf4p) were expressed in Sf9 cells co-infected with baculoviruses expressing each polypeptide subunit and were purified on Glutathione-Sepharose or Ni-NTA Agarose columns, respectively, as in.46

PhosTagTM gel retardation assays

The experiments in Figure 1A were conducted as follows: 50 ml of W303 cac1::MYC18::KanMX cells were grown to OD600 = 1, then washed and disrupted with glass beads in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 50 mM KAc, 5 mM Mg(COO−)2, 0.1 M sorbitol, 0.1% Triton-X100, 2 mM DTT and protease inhibitors (Sigma). The extract was immunoprecipitated with 15 μl Dynabeads-protein G coated with anti-MYC (mouse) antibody at 4°C for 1.5 hours. Beads were washed with phosphatase buffer (NEB) and one third was incubated for 30 min at 30°C with 2 U/μl Lambda Protein Phosphatase (NEB). The rest of the sample was incubated with buffer alone. Beads were boiled in 4% SDS/8 M Urea and run on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 60 μM PhosTagTM and 100 μM MnCl2.16 The proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-MYC (rabbit) antibodies. In Figures 1B, D and 3A the cell pellets were boiled in 4% SDS/8M Urea, disrupted with glass beads and loaded on PhosTagTM 100 μM MnCl2 containing gels.

Kinase assays and LC-MS/MS analyses

0.5 μg of GST-Cac1p or GST-Rtt106p substrates were incubated for 45 min at 30°C with 50 ng of Cdc7p-Dbf4p or 150 ng of Cdc28p-Clb5p in 40 mM Hepes-KOH pH7.6, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 2 mM DTT, 8 mM Mg(COO−)2, 0.1 mM ATP, 1 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP. The reactions were resolved on 5–20% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels and exposed to a Phosphorimager® screen. Equal loading was confirmed by Coomassie staining of the gels.

The kinase assays in Figure 2C were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM ATP, 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP for 30 min at 37°C with extracts from bacterial cells expressing Cac1(226–607)-His6 or Hst3-His6. The kinase assays for the LC-MS/MS analysis of the in vitro phosphorylation of Cac1(226–607)-His6 by Cdk7p-Dbf4p (Fig. 2C) were performed with 50 μM cold ATP for 30 min at 37°C and the substrate was purified on Ni-NTA beads before being processed for in-solution trypsin digestion. Analysis of the in vivo phosphorylation of Cac1p, Cac2p and Cac3p was conducted by purification of CAF-I via TAP-tagged Cac2p followed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel separation and in-gel trypsin digestion. Details on the LS-MS/MS procedure are available upon request.

Chromatin fractionation

50 ml cultures at OD600 = 1.0 were harvested in the presence of 0.1% NaN3 treated with 0.25 μg zymolyase until 95% spheroplasting was visible and washed in ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.8 M sorbitol. Cells were lysed in 150 μl of Extraction Buffer (EB: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton-X100, 5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate plus protease inhibitors (Sigma)). Lysates were spun 10 min at 12000 rpm and supernatants were collected as cytoplasmic fractions. Pellets were resuspended in 150 μl EB and cushions of 50 μl EB containing 30% sucrose were under-layered. The samples were spun again at 12000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatants were discarded. The pellets and aliquots of the cytoplasmic fractions were boiled in Laemmli loading buffer and analyzed in SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells harvested in the presence of 0.1% NaN3 were disrupted with glass beads in ice-cold IP Buffer (IPB: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 80 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM b-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM Na3VO4 with protease inhibitors (Sigma)). The lysates were spun 10 min at 12000 rpm and the supernatants were immunoprecipitated overnight with 15 μl of anti-MYC beads (Sigma). The beads were washed 3 times in IPB plus 0.2% Triton-X100, 0.03% Deoxycholic acid, once with IPB plus 420 mM NaCl, and once with IPB. Samples were boiled in Laemmli loading buffer and analyzed in SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Cac1p-FLAG proteins were immunoprecipitated with 15 μl Protein-G beads (Sigma) and 6 μg of anti-FLAG (mouse) antibody.

Quantifying of Western Blot signals

Signals from blots with equal chemiluminescent exposures were acquired by ImageJ software and converted to 8 bit (grayscale), background was subtracted and signals were analyzed as mean gray value of the blot relative to the India Ink stain. In the chromatin fractionation experiments the cytoplasm signals were amplified by 6.875 to reflect the lower proportion of extract loaded.

Two-hybrid interaction assay

cac1Δ cells were co-transformed with pSH18–34, pEG202 bait plasmids expressing wild type or mutant LexA-Cac1p proteins, and the prey pBL240 expressing Gal4AD-PCNA. The cells were grown in SC/-Leu/-Ura/-His at 30ºC to OD600 = 0.8–1.0, then pelleted and resuspended in SC/-Leu/-Ura/-His with 2% Galactose and 1% Raffinose and then incubated at 30ºC for 4 hours. Cells were harvested, resuspended in Buffer P (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.7, 300 mM sodium acetate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 500 nM DTT plus protease inhibitors (Sigma), split into 4 equal parts and lysed with glass beads. Total protein levels were measured and used to normalize the protein concentrations for the β-galactosidase assay. The extracts were then incubated with 4 mg/ml ortho-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside at 30ºC until the production of a yellow color was observed. Absorbance readings were taken at OD420 and OD550. The units of β-galactosidase were calculated using the following formula:

Telomere position effect experiments were conducted as described in.28

In vitro nucleosome assembly assay

100 ml yeast cell cultures at OD600 = 1 were harvested and broken with glass beads in 300 μl of ice-cold YEB (100 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9, 245 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)). The extracts were spun for 10 min at 18000 g. The supernatant was exchanged to YDBI buffer (20 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 0.05 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol plus protease inhibitors) in Biospin P-6 columns (Biorad). Nucleosome assembly reactions were conducted at 30°C with various amounts of cell extracts in 100 μl YDBI plus 7.5 mM MgCl2, 3 mM ATP and 0.1 pmoles of relaxed pBluescript plasmid. The plasmid was then extracted and analyzed on 1.5% agarose/TAE gels.

pBluescript was produced in E.coli and preparations that contained at least 80% of supercoiled plasmid were treated for 3–4 hours with Topoisomerase I (NEB). The level of relaxation was confirmed by running the sample in 1.5% agarose/TAE gels and washing with 2X RedSafeTM nucleic acid staining solution (FroggaBio).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Brikner for the cdc28–1 strain; Dr. B. Stillman for the cdc7–1 strain and anti-scPCNA antibody; Dr. A. Bielinsky, Dr. Kolodner for the 2-hybrid plasmids; Dr. G. van der Merwe for the anti-Utp8p and anti-Adh1p antibodies.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from NSERC to KY (#217548); a joint grant from JSPS/CIHR to KY and HM (#JOH 410–90177–08); a grant from CIHR to AV (#FRN 89928); a grant from NSERC to AV and PT (#311598). AV and PT hold Canada Research Chairs in Chromosome Biogenesis, and Proteomics and Bioanalytical Spectrometry, respectively.

References

- 1. Ransom M, Dennehey BK, Tyler JK. Chaperoning histones during DNA replication and repair. Cell 2010; 140:183-95; PMID:20141833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alabert C, Groth A. Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13:153-67; PMID:22358331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Castillo AG, Osborne MJ, Borden KL, Kornblatt J, Verreault A. Two fundamentally distinct PCNA interaction peptides contribute to chromatin assembly factor 1 function. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:6353-65; PMID:19822659; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01051-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shibahara K, Stillman B. Replication-dependent marking of DNA by PCNA facilitates CAF-1-coupled inheritance of chromatin. Cell 1999; 96:575-85; PMID:10052459; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80661-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Z, Shibahara K, Stillman B. PCNA connects DNA replication to epigenetic inheritance in yeast. Nature 2000; 408:221-5; PMID:11089978; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35048530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerard A, Koundrioukoff S, Ramillon V, Sergere JC, Mailand N, Quivy JP, Almouzni G. The replication kinase Cdc7-Dbf4 promotes the interaction of the p150 subunit of chromatin assembly factor 1 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. EMBO Rep 2006; 7:817-23; PMID:16826239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krawitz DC, Kama T, Kaufman PD. Chromatin assembly factor I mutants defective for PCNA binding require Asf1/Hir proteins for silencing. Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22:614-25; PMID:11756556; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.22.2.614-625.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monson EK, de Bruin D, Zakian VA. The yeast Cac1 protein is required for the stable inheritance of transcriptionally repressed chromatin at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:13081-6; PMID:9371803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Ultraviolet radiation sensitivity and reduction of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking chromatin assembly factor-I. Genes Dev 1997; 11:345-57; PMID:9030687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.3.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Enomoto S, McCune-Zierath PD, Gerami-Nejad M, Sanders MA, Berman J. RLF2, a subunit of yeast chromatin assembly factor-I, is required for telomeric chromatin function in vivo. Genes Dev 1997; 11:358-70; PMID:9030688; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.3.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sadowski I, Breitkreutz BJ, Stark C, Su TC, Dahabieh M, Raithatha S, Bernhard W, Oughtred R, Dolinski K, Barreto K, et al. The PhosphoGRID Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein phosphorylation site database: version 2.0 update. Database 2013; 2013:bat026; PMID:23674503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/database/bat026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keller C, Krude T. Requirement of Cyclin/Cdk2 and protein phosphatase 1 activity for chromatin assembly factor 1-dependent chromatin assembly during DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:35512-21; PMID:10938080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M003073200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Masai H, Matsumoto S, You Z, Yoshizawa-Sugata N, Oda M. Eukaryotic chromosome DNA replication: where, when, and how? Annu Rev Biochem 2010; 79:89-130; PMID:20373915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.103205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nougarede R, Della Seta F, Zarzov P, Schwob E. Hierarchy of S-phase-promoting factors: yeast Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase requires prior S-phase cyclin-dependent kinase activation. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20:3795-806; PMID:10805723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.20.11.3795-3806.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Koike T. Separation and detection of large phosphoproteins using Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. Nat Protoc 2009; 4:1513-21; PMID:19798084; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2009.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics : MCP 2006; 5:749-57; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bousset K, Diffley JF. The Cdc7 protein kinase is required for origin firing during S phase. Genes Dev 1998; 12:480-90; PMID:9472017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.12.4.480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brickner DG, Brickner JH. Cdk phosphorylation of a nucleoporin controls localization of active genes through the cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21:3421-32; PMID:20702586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou H, Madden BJ, Muddiman DC, Zhang Z. Chromatin assembly factor 1 interacts with histone H3 methylated at lysine 79 in the processes of epigenetic silencing and DNA repair. Biochemistry 2006; 45:2852-61; PMID:16503640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi0521083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith S, Stillman B. Immunological characterization of chromatin assembly factor I, a human cell factor required for chromatin assembly during DNA replication in vitro. J Biol Chem 1991; 266:12041-7; PMID:2050697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koivomagi M, Valk E, Venta R, Iofik A, Lepiku M, Morgan DO, Loog M. Dynamics of Cdk1 substrate specificity during the cell cycle. Mol Cell 2011; 42:610-23; PMID:21658602; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Masai H, Matsui E, You Z, Ishimi Y, Tamai K, Arai K. Human Cdc7-related kinase complex. In vitro phosphorylation of MCM by concerted actions of Cdks and Cdc7 and that of a criticial threonine residue of Cdc7 bY Cdks. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:29042-52; PMID:10846177; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M002713200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sasanuma H, Hirota K, Fukuda T, Kakusho N, Kugou K, Kawasaki Y, Shibata T, Masai H, Ohta K. Cdc7-dependent phosphorylation of Mer2 facilitates initiation of yeast meiotic recombination. Genes Dev 2008; 22:398-410; PMID:18245451; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1626608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liang C, Stillman B. Persistent initiation of DNA replication and chromatin-bound MCM proteins during the cell cycle in cdc6 mutants. Genes Dev 1997; 11:3375-86; PMID:9407030; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.24.3375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donovan S, Harwood J, Drury LS, Diffley JF. Cdc6p-dependent loading of Mcm proteins onto pre-replicative chromatin in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:5611-6; PMID:9159120; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schmidt KH, Derry KL, Kolodner RD. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RRM3, a 5’ to 3’ DNA helicase, physically interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:45331-7; PMID:12239216; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M207263200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tyler JK, Adams CR, Chen SR, Kobayashi R, Kamakaka RT, Kadonaga JT. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature 1999; 402:555-60; PMID:10591219; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/990147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jeffery DC, Wyse BA, Rehman MA, Brown GW, You Z, Oshidari R, Masai H, Yankulov KY. Analysis of epigenetic stability and conversions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a novel role of CAF-I in position-effect variegation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:8475-88; PMID:23863839; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tyler JK, Collins KA, Prasad-Sinha J, Amiott E, Bulger M, Harte PJ, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. Interaction between the Drosophila CAF-1 and ASF1 chromatin assembly factors. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21:6574-84; PMID:11533245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6574-6584.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaufman PD, Cohen JL, Osley MA. Hir proteins are required for position-dependent gene silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the absence of chromatin assembly factor I. Mol Cell Biol 1998; 18:4793-806; PMID:9671489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Q, Zhou H, Wurtele H, Davies B, Horazdovsky B, Verreault A, Zhang Z. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell 2008; 134:244-55; PMID:18662540; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang S, Zhou H, Katzmann D, Hochstrasser M, Atanasova E, Zhang Z. Rtt106p is a histone chaperone involved in heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:13410-5; PMID:16157874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0506176102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franco AA, Kaufman PD. Histone deposition proteins: links between the DNA replication machinery and epigenetic gene silencing. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2004; 69:201-8; PMID:16117650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Masai H, Taniyama C, Ogino K, Matsui E, Kakusho N, Matsumoto S, Kim JM, Ishii A, Tanaka T, Kobayashi T, et al. Phosphorylation of MCM4 by Cdc7 kinase facilitates its interaction with Cdc45 on the chromatin. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:39249-61; PMID:17046832; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M608935200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Montagnoli A, Valsasina B, Brotherton D, Troiani S, Rainoldi S, Tenca P, Molinari A, Santocanale C. Identification of Mcm2 phosphorylation sites by S-phase-regulating kinases. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:10281-90; PMID:16446360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M512921200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cho WH, Lee YJ, Kong SI, Hurwitz J, Lee JK. CDC7 kinase phosphorylates serine residues adjacent to acidic amino acids in the minichromosome maintenance 2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:11521-6; PMID:16864800; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0604990103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matos J, Lipp JJ, Bogdanova A, Guillot S, Okaz E, Junqueira M, Shevchenko A, Zachariae W. Dbf4-dependent CDC7 kinase links DNA replication to the segregation of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I. Cell 2008; 135:662-78; PMID:19013276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ogino K, Hirota K, Matsumoto S, Takeda T, Ohta K, Arai K, Masai H. Hsk1 kinase is required for induction of meiotic dsDNA breaks without involving checkpoint kinases in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:8131-6; PMID:16698922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0602498103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shimmoto M, Matsumoto S, Odagiri Y, Noguchi E, Russell P, Masai H. Interactions between Swi1-Swi3, Mrc1 and S phase kinase, Hsk1 may regulate cellular responses to stalled replication forks in fission yeast. Genes Cells 2009; 14:669-82; PMID:19422421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01300.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matsumoto S, Shimmoto M, Kakusho N, Yokoyama M, Kanoh Y, Hayano M, Russell P, Masai H. Hsk1 kinase and Cdc45 regulate replication stress-induced checkpoint responses in fission yeast. Cell Cycle 2010; 9:4627-37; PMID:21099360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.9.23.13937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tanaka T, Yokoyama M, Matsumoto S, Fukatsu R, You Z, Masai H. Fission yeast Swi1-Swi3 complex facilitates DNA binding of Mrc1. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:39609-22; PMID:20924116; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.173344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang S, Zhou H, Tarara J, Zhang Z. A novel role for histone chaperones CAF-1 and Rtt106p in heterochromatin silencing. EMBO J 2007; 26:2274-83; PMID:17410207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matsumoto S, Masai H. Regulation of chromosome dynamics by Hsk1/Cdc7 kinase. Biochem Society Trans 2013; 41:1712-9; PMID:24256280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Das-Bradoo S, Ricke RM, Bielinsky AK. Interaction between PCNA and diubiquitinated Mcm10 is essential for cell growth in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:4806-17; PMID:16782870; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02062-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:e115; PMID:15304544; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gnh110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weinreich M, Stillman B. Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase binds to chromatin during S phase and is regulated by both the APC and the RAD53 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J 1999; 18:5334-46; PMID:10508166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zou L, Stillman B. Assembly of a complex containing Cdc45p, replication protein A, and Mcm2p at replication origins controlled by S-phase cyclin-dependent kinases and Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20:3086-96; PMID:10757793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3086-3096.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.