Abstract

Objective To investigate relation between inpatient length of stay after hip fracture and risk of death after hospital discharge.

Setting Population ≥50 years old living in Sweden as of 31 December 2005 with a first hip fracture the years 2006-12.

Participants 116 111 patients with an incident hip fracture from a closed nationwide cohort.

Main outcome measure Death within 30 days of hospital discharge in relation to hospital length of stay after adjustment for multiple covariates.

Results Mean inpatient length of stay after a hip fracture decreased from 14.2 days in 2006 to 11.6 days in 2012 (P<0.001). The association between length of stay and risk of death after discharge was non-linear (P<0.001), with a threshold for this non-linear effect of about 10 days. Thus, for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days (n=59 154), each 1-day reduction in length of stay increased the odds of death within 30 days of discharge by 8% in 2006 (odds ratio 1.08 (95% confidence interval 1.04 to 1.12)), which increased to16% in 2012 (odds ratio 1.16 (1.12 to 1.20)). In contrast, for patients with a length of stay of ≥11 days (n=56 957), a 1-day reduction in length of stay was not associated with an increased risk of death after discharge during any of the years of follow up.

Limitations No accurate evaluation of the underlying cause of death could be performed.

Conclusion Shorter length of stay in hospital after hip fracture is associated with increased risk of death after hospital discharge, but only among patients with length of stay of 10 days or less. This association remained robust over consecutive years.

Introduction

The number of elderly people is expected to rise rapidly in Europe and worldwide in the next 30 years.1 Increasingly large frail aging populations will pose enormous costs on healthcare systems because of the need to treat and manage conditions ranging from fractures to cardiovascular disease and mental disorders.2 Healthcare spending in the United States is projected to increase by 6% from 2012 through 2022, exceeding expected growth of the gross domestic product.3 Constraints on health service expenditure have led to the streamlining of healthcare systems in many countries, reducing the numbers of available public hospital beds and lengths of stay in hospital.4 5 Strategies to reduce length of stay include earlier discharge to care in community settings or at home, with support from home care or mobile rehabilitation units.6 An important question, however, is whether early discharge increases the risk of complications and ultimately death, since the number of adequately educated staff is lower outside the hospital setting.7 Shorter length of stay may also reduce the time available for proper rehabilitation, which may be important for regaining mobility and reducing the risk of long term sequelae after events such as fragility fractures.8

Hip fracture is the most severe and common fracture in elderly women and men; it is associated with high morbidity and mortality,9 especially in older men.10 Hip fracture has also been considered to be useful as a “tracer condition” to monitor healthcare response when designing clinical and organizational improvements in the quality and effectiveness of care for the elderly.11

In Sweden, the population aged more than 50 years increased 16% from 2006 to 2012 while the number of hospital beds decreased about 8%,12 13 necessitating shorter length of stay in hospitals. In this study, we investigated the impact of changes in length of stay after hip fracture in relation to the risk of death after hospital discharge in all Swedish citizens aged at least 50 years on 31 December 2005 and who experienced such fractures between 2006 and 2012.

Methods

Study cohort

According to national population registers, a total of 3 329 400 men and women aged 50 years or more lived in Sweden as of 31 December 2005. For the present study, we identified all patients from this closed nationwide cohort who experienced hip fracture between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2012. No exclusion criterion was applied.

Diagnoses and other covariates of interest in the cohort

Data on diagnoses used in this study were obtained from the Swedish National Patient Register, which covers all inpatient care provided in Sweden since 1987 and all specialist outpatient visits since 2001. The register was searched to identify diagnoses made since 1997 using appropriate ICD-10 codes (international classification of diseases, 10th revision). Patients were included in our study based on diagnoses of incident hip fracture (ICD-10 codes S720 to S722) registered after 31 December 2005.

Other diagnoses were collected through the date of hospital discharge and were selected based on previously documented associations with fracture or death. These included dementia (ICD-10 F00, F01, F039) stroke (ICD-10 I63), myocardial infarction (ICD-10 I21), cancer (all diagnoses from the Swedish National Cancer Register), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-10 J44), renal failure (ICD-10 N17, N18) and diabetes (ICD-10 E10, E11). The National Patient Register has been validated in detail, with positive predictive values of 85% to 95%.14 15 16 Notably, the positive predictive value for hip fracture in this register is higher than 95%.17

We also collected information from the National Patient Register about types of operation for hip fracture and whether blood transfusions were given during hospitalization. Using the National Prescription Database, we linked use of antidepressants (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification code N06A) and neuroleptics (ATC code N05) at the time of hip fracture to each subject in the cohort. Date of death and underlying causes of death were obtained through record linkage with the National Cause of Death Register. Finally, information about civil status and highest education level at the time of hip fracture was collected from the Statistics Sweden database. All data were linked to cohort subjects using the unique personal identification number assigned to each Swedish citizen.

Statistical models

Baseline differences between two groups were tested using Student’s t test or the χ2 test for categorical variables. A Kaplan-Meier curve is presented for different categories of length of stay with the outcome of death within 30 days of discharge. To evaluate any interactions between length of stay and year of fracture for the outcome of death within 30 days of discharge, the total cohort was used after excluding those who died during hospital stay (110 248 patients remained).

A product interaction term was computed between length of stay and year of fracture. This product interaction term was added to a logistic regression model, together with all other variables according to table 2 (including year of fracture and length of stay). The differences of minus twice the log-likelihood (−2lnL) for a model with the interaction term and that of the model without the interaction term is approximately χ2 distributed with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in number of estimated parameters in the models. A statistically significant interaction was assumed if the difference in −2lnL between the models was significant (P<0.05). Based on a statistically significant interaction (P<0.05), we evaluated length of stay and the risk of death for each year of follow up separately, and the risk of death for those with length of stay of ≤10 days and the rest of the cohort separately.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study cohort at time of hip fracture (excluding the 5863 who died during hospital stay) by different length of stay at hospital (n=110 248). All variables had a significantly different distribution (P<0.001) for the different lengths of stay. Values are number (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Length of stay (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 (n=19 964) | 6–10 (n=34 915) | 11–14 (n=21 056) | >15 (n=34 313) | |

| Female | 13216 (66.2) | 24604 (70.5) | 14765 (70.1) | 23748 (69.2) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 79.5 (11.0) | 81.5 (9.4) | 82.8 (8.4) | 83.4 (8.0) |

| Civil status: | ||||

| Married | 6906 (34.6) | 11532 (33.0) | 6518 (31.0) | 10272 (29.9) |

| Unmarried | 2163 (10.8) | 3329 (9.5) | 2001 (9.5) | 3057 (8.9) |

| Single | 2945 (14.8) | 4628 (13.3) | 2738 (13.0) | 4619 (13.5) |

| Widow/widower | 7944 (39.8) | 15418 (44.2) | 9799 (46.5) | 16356 (47.7) |

| Education: | ||||

| ≤9 years of school | 10426 (54.0) | 20116 (59.4) | 12319 (60.5) | 19151 (57.8) |

| 2 years of upper school | 4883 (25.3) | 8107 (23.9) | 4769 (23.4) | 7970 (24.1) |

| ≥3 years of upper school | 1371 (7.1) | 1943 (5.7) | 1170 (5.7) | 2225 (6.7) |

| University education | 2629 (13.6) | 3689 (10.9) | 2117 (10.4) | 3759 (11.4) |

| Main diagnosis (%): | ||||

| Collum femoris fracture | 11756 (58.9) | 18795 (53.8) | 10558 (50.1) | 15347 (44.7) |

| Pertrochanteric fracture | 6481 (32.5) | 13008 (37.3) | 8170 (38.8) | 13728 (40.0) |

| Subtrochanteric fracture | 1097 (5.5) | 2389 (6.8) | 1708 (8.1) | 3178 (9.3) |

| Other | 630 (3.2) | 723 (2.1) | 620 (2.9) | 2060 (6.0) |

| Type of operation: | ||||

| Nailing | 2610 (13.1) | 3639 (10.4) | 1520 (7.2) | 1548 (4.5) |

| Intermedullary nailing | 2105 (10.5) | 4150 (11.9) | 2513 (11.9) | 5433 (15.8) |

| Hip screws | 6139 (30.8) | 8106 (23.2) | 4559 (21.7) | 7397 (21.6) |

| Total or partial hip replacement | 2473 (12.4) | 6855 (19.6) | 4629 (22.0) | 7291 (21.2) |

| Primary hip arthroplasty | 755 (3.8) | 2343 (6.7) | 1154 (5.5) | 1484 (4.3) |

| Other | 5882 (29.5) | 9822 (28.1) | 6681 (31.7) | 11160 (32.5) |

| Blood transfusion | 1118 (5.6) | 2985 (8.5) | 2148 (10.2) | 3395 (9.9) |

| Diagnosis at baseline: | ||||

| Dementia | 5570 (27.9) | 6347 (18.2) | 2320 (11.0) | 3476 (10.1) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1846 (9.2) | 2990 (8.6) | 2038 (9.7) | 3858 (11.2) |

| Stroke | 2216 (11.1) | 3969 (11.4) | 2704 (12.8) | 5088 (14.8) |

| Obstructive pulmonary disorder | 1241 (6.2) | 2173 (6.2) | 1527 (7.3) | 2972 (8.7) |

| Diabetes | 2451 (12.3) | 4541 (13.0) | 3107 (14.8) | 5590 (16.3) |

| Renal failure | 618 (3.1) | 876 (2.5) | 685 (3.3) | 1560 (4.5) |

| Cancer | 4508 (22.6) | 8128 (23.5) | 5325 (25.3) | 9175 (26.7) |

| Drug treatments: | ||||

| Antidepressants | 5800 (29.1) | 9409 (26.9) | 5014 (23.8) | 7915 (23.1) |

| Neuroleptics | 2423 (12.1) | 3088 (8.8) | 1203 (5.7) | 1649 (4.8) |

To test whether the increased risk of death for those with length of stay of ≤10 days compared with length of stay of ≥11 days was time dependent, we evaluated Schoenfeld’s residuals using estat phtest command (Stata software). Given that the test indicated that the proportional hazard assumption was violated (χ2 = 108.2, P<0.001), the independent association between length of stay (per day decrease) and the risk of death within 30 days of discharge was analyzed using binary logistic regression in four models. The first model was adjusted for age (continuous) and sex (male/female), the second also included civil status (four categories) and education (four categories), the third model additionally included types of hip fracture (four categories) and surgery (six categories), and the final model was extended to include comorbidities up to the date of discharge (seven categories), drug use (two categories), and blood transfusion (yes/no). The outcome for these models was death within 30 days of discharge.

To test whether the odds ratio for length of stay and risk of death was significantly different in 2006 compared with the later years, a test of heterogeneity was used (“metan” command in the Stata software), based on the odds ratio and the 95% confidence intervals.

To formally test whether the association between length of stay and death within 30 days of discharge was linear, we also included length of stay as squared term in the fully adjusted statistical model. Since this model indicated a non-linear relationship, we further evaluated this association using a proportional hazards model, restricted cubic splines with five knots (5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th centiles as suggested by Harrell).18 A length of stay of 12 days (mean length of stay in 2012) was used as the reference in these models.

In a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the effects of categorized length of stay (≤10 v ≥11 days) on the risk of death with increasing follow-up duration, using a flexible parametric model with time dependent effects and three degrees of freedom.19

The Stata software (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) and SPSS (version 21; IBM, New York, United States) were used to fit the statistical models and graphically illustrate the results.

Results

During 20.9 million person-years of observation in 3.3 million individuals at risk, 116 111 (3.5%) patients sustained a hip fracture at a mean age of 82.2 years.

Among the individuals with hip fracture, table 1 shows the risk of death during hospital stay, within 30 days of admission, and within 30 days of discharge. In total 5863 patients died during hospital stay, 6377 died within 30 days of discharge, and 30052 (25.9%) died within one year after admission for fracture. Age was the overall strongest predictor of the risk of death within one year of admission (odds ratio 1.072 (95% confidence interval 1.071 to 1.074) per year).

Table 1.

The risk of death during hospital stay, within 30 days of admission, and 30 days of discharge and mean length of stay for 116 111 people aged ≥50 years admitted to hospital with hip fracture. Data are presented separately for the years of follow-up

| Year of hip fracture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 (n=18 142) | 2007 (n=17 108) | 2008 (n=17 121) | 2009 (n=16 500) | 2010 (n=16 251) | 2011 (n=16 021) | 2012 (n=14 968) | |

| Total No of individuals at risk | 3 329 400 | 3 228 238 | 3 129 866 | 3 033 778 | 2 941 390 | 2 850 423 | 2 761 529 |

| No (%) of deaths: | |||||||

| During hospital stay | 879 (4.8) | 846 (4.9) | 862 (5.0) | 777 (4.7) | 862 (5.3) | 798 (5.0) | 839 (5.6) |

| Within 30 days of admission | 1412 (7.8) | 1447 (8.5) | 1457 (8.5) | 1389 (8.4) | 1433 (8.8) | 1341 (8.4) | 1479 (9.9) |

| Within 30 days of discharge | 935 (5.2) | 964 (5.6) | 940 (5.5) | 924 (5.6) | 859 (5.3) | 856 (5.3) | 899 (6.0) |

| Mean (SD) length of stay (days) | 14.2 (12.6) | 14.0 (11.50) | 13.2 (10.4) | 12.8 (10.2) | 12.6 (10.0) | 12.2 (9.2) | 11.6 (8.7) |

The mean length of stay in hospital after hip fracture was 14.2 (range 0–343) days in 2006, and decreased to 11.6 (0–137) days in 2012 (P<0.001) (table 1). Table 2 shows the basic characteristics of the cohort for length of stay of 0–5 days, 6–10 days, 11–14 days, and ≥15 days, including patients who did not die during hospital time (n=110 248). Early discharge was associated with more femoral neck fractures and dementia.

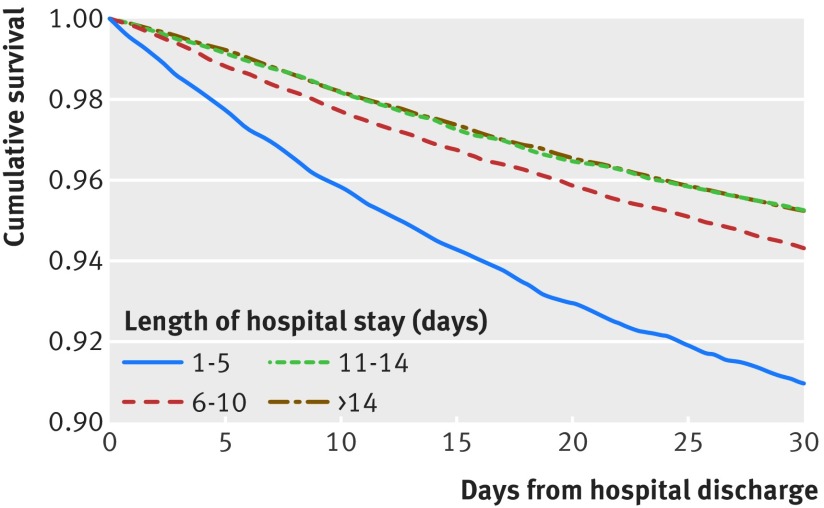

Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for the risk of death within 30 days of discharge for categories of length of stay (n=110 248). After adjusting for all covariates according to table 2 and excluding those who died during hospital stay, we found that patients with a length of stay of 1–5 days had twice the risk of death within 30 days of discharge compared with patients with a length of stay of ≥15 days (odds ratio 1.97 (95% CI 1.83 to 2.13)).

Fig 1 Cumulative risk of death within 30 days of discharge for patients with a length of stay of 0–5 days, 6–10 days, 11–14 days, and ≥15 days. Patients who died during hospital stay were excluded

Inpatient length of stay and risk of death within 30 days of discharge

Given the observed strong interaction between length of stay and year of hip fracture with respect to the risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge (P<0.001 for interaction in a model including all covariates), data were analyzed separately for each year. After adjustment for all covariates (according to table 2) and exclusion of subjects who died before hospital discharge, a 1-day reduction in length of stay was marginally significantly associated with death within 30 days of hospital discharge in 2006 (odds ratio 1.007 (1.000 to 1.013)). Based on heterogeneity test, this association was significantly higher in 2007, 2009, 2010, and 2012 (table 3).

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge for a 1-day decrease in length of hospital stay after a hip fracture for each year during follow-up. Patients who died during hospital stay were excluded from all analyses

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Year of follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Adjusted for age and sex | 1.011 (1.005 to 1.018) | 1.025 (1.017 to 1.032) | 1.022 (1.014 to 1.030) | 1.031 1.022 to 1.040) | 1.031 (1.021 to 1.040) | 1.020 (1.011 to 1.029) | 1.050 (1.038 to 1.061) |

| Adjusted as above + civil status and education | 1.010 (1.004 to 1.017) | 1.023 (1.016 to 1.031) | 1.021 (1.013 to 1.030) | 1.031 (1.022 to 1.040) | 1.029 (1.020 to 1.039) | 1.019 (1.010 to 1.028) | 1.049 (1.038 to 1.060) |

| Adjusted as above + type of hip fracture and operation | 1.011 (1.005 to 1.018) | 1.025 (1.017 to 1.033) | 1.023 (1.015 to 1.031) | 1.033 (1.024 to 1.043) | 1.032 (1.022 to 1.042) | 1.021 (1.012 to 1.031) | 1.051 (1.040 to 1.062) |

| Adjusted for all covariates* | 1.007 (1.000 to 1.013) | 1.019 (1.011 to 1.027) | 1.017 (1.009 to 1.026) | 1.027 (1.018 to 1.037) | 1.022 (1.013 to 1.032) | 1.013 (1.004 to 1.022) | 1.038 (1.026 to 1.049) |

*All variables according to table 2 were included in these analyses.

Non-linear association between length of stay and short term mortality

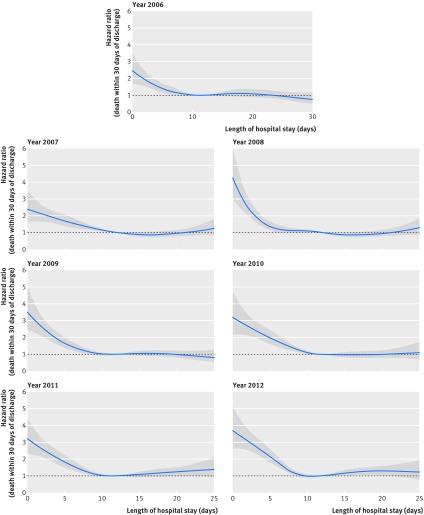

However, as presented in figure 2, the association between length of stay and risk of death after discharge was non-linear (P<0.001). The threshold for this non-linear effect was about 10 days. Thus, for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days, each day’s reduction in length of stay increased the risk of death within 30 days of discharge by 8% in 2006 (odds ratio 1.076 (1.033 to 1.121)). This association increased to 16% more deaths for each day’s reduction in length of stay in 2012 (odds ratio 1.164 (1.122 to 1.208), P=0.007 for interaction). In contrast, for patients with length of stay of ≥11 days, each day shorter length of stay was not associated with an increased risk of death for any year in the study period (table 4).

Fig 2 Association between length of stay and risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge for the years of follow-up. Patients who died during hospital stay were excluded. To model the effects of length of stay, restricted cubic splines with five knots were used (giving 4 degrees of freedom), followed by fitting a proportional hazards model with a length of stay of 12 days as reference.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge for a 1-day decrease in length of hospital stay after a hip fracture for subgroups with lengths of stay of ≤10 days or ≥11 days for each year during follow-up. Patients who died during hospital stay were excluded from all analyses

| Year of follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Length of stay of ≤10 days | |||||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI)* | 1.076 (1.033 to 1.121) | 1.083 (1.042 to 1.127) | 1.121 (1.078 to 1.167) | 1.130 (1.087 to 1.175) | 1.117 (1.073 to 1.162) | 1.120 (1.078 to 1.163) | 1.164 (1.122 to 1.208) |

| No of subjects at risk | 8220 | 7683 | 7933 | 7931 | 7806 | 7748 | 7558 |

| No (%) of deaths | 495 (6.0) | 556 (7.2) | 527 (6.6) | 550 (6.9) | 542 (6.9) | 509 (6.6) | 576 (7.6) |

| Length of stay of ≥11 days | |||||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI)* | 1.000 (0.993 to 1.007) | 1.003 (0.994 to 1.012) | 1.002 (0.993 to 1.012) | 1.005 (0.994 to 1.017) | 0.993 (0.982 to 1.003) | 0.987 (0.976 to 0.997) | 1.009 (0.994 to 1.024) |

| No of subjects at risk | 9043 | 8579 | 8326 | 7792 | 7583 | 7475 | 6571 |

| No (%) of deaths | 440 (4.9) | 408 (4.8) | 413 (5.0) | 374 (4.8) | 317 (4.2) | 347 (4.6) | 323 (4.9) |

*Adjusted for all covariates according to table 2.

Next, we found that a short length of stay, tested by comparing patients with a length of stay of ≤10 against patients with a length of stay of ≥11 days, was associated with an especially increased risk of death within 30 days of discharge for some subgroups (online supplemental fig 1). Highest risks were noted for men, patients with trochanteric fractures, and subjects with certain comorbidities (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, and cardiovascular disease).

Causes of death within 30 days of discharge

The most common underlying cause of death within 30 days of hospital discharge, according to the National Cause of Death Register, was “expos[ure] to non-specified factor - home” (ICD-10 code X590), recorded on the death certificates of 1371 (21.5%) subjects. Other common underlying causes of death were ischaemic heart disease, including myocardial infarction (845 (13.2%) subjects); any form of cancer (710 (10.0%) subjects); dementia (467 (7.2%) subjects); falls (381 (5.9%) subjects); and stroke (245 (3.7%) subjects). Other causes of death included smaller miscellaneous diagnostic groups.

Sensitivity analyses

In a first sensitivity analysis, we found that the increased risk of death after discharge associated with a short length of stay (comparing length of stay of ≤10 v ≥11 days) decreased with increasing follow-up (supplemental fig 2). Therefore, we evaluated the risk of death between 11 and 30 days of hospital admission for patients alive at day 10 and with a length of stay of ≤10 days (supplemental table). Each 1-day reduction in length of stay increased the risk of death during 11–30 days of hospital admission by 4% in 2006 (odds ratio 1.04 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.09)). This association increased to 12% more deaths for each 1-day reduction in length of stay in 2012 (odds ratio 1.12 (1.07 to 1.17), P=0.03 for interaction).

Discussion

The present study showed that a shorter length of hospital stay after hip fracture was associated with an increased risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge in the Swedish population. This association seemed to increase over the seven years of follow-up as mean length of stay decreased by about 20%. The increased risk of death associated with short length of stay was not linear and was confined to patients with length of stay of 10 days or less throughout the study period. Our results suggest that the continuous efforts to decrease length of stay after major surgery in many countries is associated with higher mortality after hospital discharge.

Clinical implications of the results

The results may seem surprising given that length of hospital stay after a hip fracture should be adapted to the patient’s general condition and therefore not associated with death after hospital discharge. In a recent study, Kaboli and others evaluated length of stay in all medical conditions in relation to re-admission rates in all 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals in the United States during the period 1997-2010.20 Mean length of stay decreased from 5.4 to 4 days during follow-up, with a concomitant decrease in re-admission rates of 2.7%. The results show that shorter length of stay could be accompanied by improved or stable re-admission rates, especially for medical conditions where the treatment has improved, such as myocardial infarctions.21 Important differences in relation to our study include the mean age of the patients of 65 years (compared with 82 years in our study), the main exposure of medical conditions associated with a short length of stay, and the primary outcome (re-admission to hospital v mortality).

Our results are supported by a previous study that examined the association between length of stay after hip fracture and death after discharge among 492 subjects from three hospitals in Japan and two in the US.22 Mean postoperative length of stay was 5 days in the US and 34 days in Japan, and the risk of death after hospital discharge was doubled in the US in comparison with Japan. In the total cohort, a 1-day reduction in length of stay increased the risk of death after discharge by 2.6%. In our study, however, the association between length of stay and death after discharge was not linear. Thus, length of stay was not associated with the risk of death within 30 days of discharge for patients with a length of stay of at least 11 days. In contrast, for patients with length of stay of 10 days or less in 2006, each 1-day reduction in length of stay was associated with an 8% increase in the risk of death after discharge. The strength of the association increased twice during the seven years of observation. The overall reduction of length of stay during the follow-up period may have contributed to these time-dependent effects.

The mechanism underlying the increased risk of death after discharge is of interest. Strategies to reduce length of stay include early discharge to rehabilitation in community settings,6 22 which results in patients’ exposure to fewer care providers with adequate education in the early postoperative period. European and North American studies have shown that care provision by more nurses with at least bachelor’s degrees is associated with lower mortality after surgery.7 23 24 Shorter length of stay also reduces the time available for comprehensive evaluation of medical conditions during hospitalization, often referred to as comprehensive geriatric assessment. A growing body of evidence suggests that comprehensive geriatric assessment decreases the risks of complications after hip fracture25 26 and death after discharge in elderly patients.27 Elderly patients with hip fracture, who often have multiple comorbidities and high risks of complications,28 29 may be at particularly high risk. This was confirmed in the present study, as men with several different diagnoses and trochanteric fractures at baseline were at especially high risk of post-discharge death after shorter length of stay.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The present study has potential limitations. The risk of death was highest immediately after admission to hospital and, by definition, was related to fracture and inpatient hospital care. Yet, no proper evaluation of the underlying cause of death was performed in many cases, and the most common cause of death according to the National Cause of Death Register was “expos[ure] to non-specified factor.” This low accuracy may relate to the current low frequency of autopsy in Sweden.30 An evaluation of specific causes of death in this population would clearly provide important information useful for implementing measures with the aim of reducing the risk of complications and risk of death after hip fracture.

The fact that the highest rates of death occur early after a hip fracture would mean that, if length of stay decreases in a population, the risk of death after discharge would automatically increase. In the present study this could bias the association between length of stay and death during follow-up as length of stay decreased. In the final sensitivity analysis we therefore evaluated length of stay and the risk of death within 11–30 days of admission for patients with a length of stay of 10 days or fewer. The significant association between death and shorter length of stay in this model confirmed the main results of our study. None the less, given the relative short observation period (2006–12) and the closed cohort studied, the stronger association between length of stay and death after discharge during the years of follow-up should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, we lacked information about whether subjects were discharged to home or to community based living facilities such as nursing homes. It would be of interest to evaluate whether certain type of living after discharge is associated with a more favourable outcome.

Strengths of the present study include the large, well characterized, nationwide cohort of hip fracture patients; no exclusions; and the use of the individual personal registration number, rendering virtually no loss to follow-up and enabling linkage to national registries. Therefore, we had the opportunity to reduce the potential influence of a reverse causation phenomenon in our study by adjusting our estimates for comorbid conditions, medications, socioeconomic status, hip fracture subcategory, and type of surgery.

Conclusion

Shorter length of hospital stay was associated with an increased risk of death after discharge in Swedish patients with hip fractures. This increased risk was confined to patients with length of stay of 10 days or fewer. In addition to evaluation of other diagnoses than hip fractures, further research should seek to gain a better understanding of the underlying cause of the increased risk of death after discharge in surgical patients, and evaluate whether early discharge to rehabilitation centers or nursing homes is associated with a worse outcome.

What is already known on this topic

Patients’ length of stay at hospital has decreased for many conditions, including hip fractures

A shorter length of stay may influence the time for proper rehabilitation and could increase the risk for complications.

What this study adds

Shorter length of hospital stay after hip fracture was associated with an increased risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge in the Swedish population

This increased risk was confined to patients with length of stay of 10 days or fewer

Contributors: KM and PN contributed equally to the paper. PN conceived the idea for the study. PN compiled and analyzed the study estimates with the help and input of AN and KM. PN made initial drafts of tables and figures with input from all other authors. PN led the writing of the paper with contributions from all other authors.

Funding: The present study was funded by the Swedish research council. The researchers conducted this study totally independent of the funding bodies.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical considerations: This study was approved by the regional ethics board in Umeå and by the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h696

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary fig 1: Subgroup analysis of risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days v ≥11 days. Supplementary fig 2: Risk of death up to 365 days after hospital discharge for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days v ≥11 days. Supplemental table: Risk of death between 11 and 30 days of hospital admission for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days.

References

- 1.United Nations. World population prospects. The 2012 revision. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2013.

- 2.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. World Economic Forum, 2011.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2012-2022. 2013. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/proj2012.pdf.

- 4.OECD. Health at a glance: Europe 2012. OECD Publishing, 2012:154.

- 5.Clarke A, Rosen R. Length of stay. How short should hospital care be? Eur J Public Health 2001;11:166-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingworth W, Todd C, Parker M, Roberts JA, Williams R. Cost analysis of early discharge after hip fracture. BMJ 1993;307:903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Griffiths P, Busse R, et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014;383:1824-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karinkanta S, Piirtola M, Sievanen H, Uusi-Rasi K, Kannus P. Physical therapy approaches to reduce fall and fracture risk among older adults. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010;6:396-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. BMJ 2006;333:27-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaelsson K, Nordstrom P, Nordstrom A, Garmo H, Byberg L, Pedersen NL, et al. Impact of hip fracture on mortality: a cohort study in hip fracture discordant identical twins. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:424-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qureshi A, Gwyn Seymour D. Growing knowledge about hip fracture in older people. Age Ageing 2003;32:8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Sweden Database. Official population statistics. 2014. www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/.

- 13.Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Quality and efficiency in Swedish health care: regional comparisons 2012. 2013. http://www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2407448/open_comparison.pdf.

- 14.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koster M, Asplund K, Johansson A, Stegmayr B. Refinement of Swedish administrative registers to monitor stroke events on the national level. Neuroepidemiology 2013;40:240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammar N, Alfredsson L, Rosen M, Spetz CL, Kahan T, Ysberg AS. A national record linkage to study acute myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(suppl 1):S30-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michaelsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, Johnell O, Magnusson C, Persson PG, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of hip fracture: population based case-control study. The Swedish Hip Fracture Study Group. BMJ 1998;316:1858-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrell F. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer-Verlag, 2001.

- 19.Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med 2002;21:2175-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaboli PJ, Go JT, Hockenberry J, Glasgow JM, Johnson SR, Rosenthal GE, et al. Associations between reduced hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rate and mortality: 14-year experience in 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals. Ann Intern Med 2012;157(12):837-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358:527-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo A, Zierler BK, Isokawa Y, Hagino H, Ito Y, Richerson M. Comparison of lengths of hospital stay after surgery and mortality in elderly hip fracture patients between Japan and the United States—the relationship between the lengths of hospital stay after surgery and mortality. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:826-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002;288:1987-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rafferty AM, Clarke SP, Coles J, Ball J, James P, McKee M, et al. Outcomes of variation in hospital nurse staffing in English hospitals: cross-sectional analysis of survey data and discharge records. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44:175-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundstrom M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, Brannstrom B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:622-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidan M, Serra JA, Moreno C, Riquelme G, Ortiz J. Efficacy of a comprehensive geriatric intervention in older patients hospitalized for hip fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1476-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O’Neill D, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2005;331:1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence VA, Hilsenbeck SG, Noveck H, Poses RM, Carson JL. Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gedeborg R, Thiblin I, Byberg L, Wernroth L, Michaelsson K. The impact of clinically undiagnosed injuries on survival estimates. Crit Care Med 2009;37:449-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary fig 1: Subgroup analysis of risk of death within 30 days of hospital discharge for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days v ≥11 days. Supplementary fig 2: Risk of death up to 365 days after hospital discharge for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days v ≥11 days. Supplemental table: Risk of death between 11 and 30 days of hospital admission for patients with length of stay of ≤10 days.