Abstract

Objective To characterize the absolute risks for older patients of readmission to hospital and death in the year after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia.

Design Retrospective cohort study.

Setting 4767 hospitals caring for Medicare fee for service beneficiaries in the United States, 2008-10.

Participants More than 3 million Medicare fee for service beneficiaries, aged 65 years or more, surviving hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia.

Main outcome measures Daily absolute risks of first readmission to hospital and death for one year after discharge. To illustrate risk trajectories, we identified the time required for risks of readmission to hospital and death to decline 50% from maximum values after discharge; the time required for risks to approach plateau periods of minimal day to day change, defined as 95% reductions in daily changes in risk from maximum daily declines after discharge; and the extent to which risks are higher among patients recently discharged from hospital compared with the general elderly population.

Results Within one year of hospital discharge, readmission to hospital and death, respectively, occurred following 67.4% and 35.8% of hospitalizations for heart failure, 49.9% and 25.1% for acute myocardial infarction, and 55.6% and 31.1% for pneumonia. Risk of first readmission had declined 50% by day 38 after hospitalization for heart failure, day 13 after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, and day 25 after hospitalization for pneumonia; risk of death declined 50% by day 11, 6, and 10, respectively. Daily change in risk of first readmission to hospital declined 95% by day 45, 38, and 45; daily change in risk of death declined 95% by day 21, 19, and 21. After hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia, the magnitude of the relative risk for hospital admission over the first 90 days was 8, 6, and 6 times greater than that of the general older population; the relative risk of death was 11, 8, and 10 times greater.

Conclusions Risk declines slowly for older patients after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia and is increased for months. Specific risk trajectories vary by discharge diagnosis and outcome. Patients should remain vigilant for deterioration in health for an extended time after discharge. Health providers can use knowledge of absolute risks and their changes over time to better align interventions designed to reduce adverse outcomes after discharge with the highest risk periods for patients.

Introduction

Patients are vulnerable to major adverse outcomes after hospital stay. Readmissions are common: nearly one in five adults aged more than 65 is readmitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge.1 Death is also common in this first month, during which rates of post-discharge mortality may exceed initial inpatient mortality.2 3 The range of illnesses to which patients are susceptible is extremely broad.4 This period of heightened and generalized vulnerability to a broad spectrum of conditions has been called the post-hospital syndrome.5

Yet risk after discharge from hospital remains incompletely characterized. Previous research has largely focused on calculating rates of readmission and death within the first month after discharge (for example, 30 day readmission rates).2 6 7 8 In contrast, a few studies have compared relative differences in risk after hospital stay among different patient groups admitted with the same condition.9 10 11 Yet none of these studies have characterized patients’ absolute risks of readmission and death or the extent to which these risks change with time over the full year after hospital discharge. We therefore do not know when these risks are highest after discharge; when they become stable over time, with minimal day to day change; and the extent to which they are increased compared with a general elderly population. We also do not know if risk varies by admitting condition or outcome. This knowledge of absolute risks and their changes over time is critical to defining the period in which post-hospital syndrome persists and can help inform patients and their healthcare professionals about the timing of vulnerability after hospital discharge. This information is needed to set realistic expectations and goals for recovery after discharge. These data can also help hospitals to more efficiently align interventions designed to reduce adverse outcomes after hospital stay to the highest risk periods for patients.

Several specific questions need to be addressed. Firstly, are the absolute risks of hospital readmission and death increased beyond 30 days after discharge, indicating that patients and providers should maintain high vigilance for deterioration in health beyond the initial month after hospitalization? Secondly, do the risks of readmission to hospital and death decline at different rates over time, suggesting that these outcomes result from different factors and therefore require different interventions to be most effectively reduced? Thirdly, does the period of increased risk differ by the initial condition triggering admission to hospital, implying a potential benefit of tailoring the duration and intensity of follow-up to the index diagnosis? Fourthly, do risks of readmission to hospital and death eventually approach plateau periods of relative stability, suggesting that patients may have entered a new phase of recovery with reduced vulnerability? Finally, is the risk of hospital admission and death after discharge noticeably higher than among the general elderly population for the full year after discharge from hospital, indicating that acute illness and hospital stay have longstanding affects on major adverse outcomes?

Accordingly, we define absolute risks of first readmission to hospital and death and their changes in the year after discharge among a national cohort of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries surviving hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. These three conditions are common reasons for hospital admission among older adults12 and have been the focus of public reporting.13 Knowledge of explicit risk trajectories can help patients and physicians set realistic goals and can help hospitals to more efficiently align the duration and intensity of follow-up care with each patient’s condition specific risk for readmission to hospital and death.

Methods

Study sample

We used Medicare standard analytic and denominator files to identify all admissions to acute care hospitals from 2008-10 with a principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. Cohorts were defined using international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) codes identical to those used in the publicly reported readmission and mortality measures14 15 16 17 18 from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (see supplementary table 1). We included admissions to hospital among patients aged 65 years or older. We excluded patients with in-hospital death, less than one year post-discharge enrolment in Medicare fee for service in the absence of death, transfer to another acute care facility, discharge against medical advice, and uncertain vital status. As with the federal readmission measures,14 15 16 17 18 we used all index hospital hospitalizations across three years of study for analyses of readmissions to hospital. We restricted analyses of death to one random hospitalization per patient over the three year period to avoid repeated measurement of patients who died within one year of multiple admissions for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia.

Study endpoints

For the year after hospitalization, we identified the occurrence of first readmission to hospital and death on each day after discharge. As with the federal readmission measures,15 16 18 we only included readmissions to short term acute care hospitals and excluded all planned readmission to hospitals based on the presence of specific ICD-9-CM procedure and principal diagnosis codes.19 We did not consider transfers to other hospitals on the day of discharge or the next day after discharge to be readmission to hospitals.15 16 18

Comparator population

To compare the risks of readmission and death after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia with the risks of hospital admission and death in the general elderly population, we constructed a comparator population using the 2009 Medicare denominator and provider analysis and review files. The Medicare denominator file contains information on beneficiaries’ enrolment status in Medicare fee for service, date of birth, and date of death. The Medicare provider analysis and review file contains information on inpatient hospital admissions for enrolled Medicare fee for service beneficiaries, including the principal discharge diagnosis, date of admission, and date of discharge. Our comparator population included all Medicare fee for service beneficiaries aged 65 years or older on 1 January 2009 with at least 12 months of enrolment in fee for service Medicare in the absence of death.

Outcomes

Daily risks of readmission and death

We estimated the daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death by day (1-365) after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. To illustrate risk trajectories, we identified the length of time required for daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death to each decline 50% from its maximum value after discharge. We also characterized the length of time required for daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death to approach plateau periods of minimal day to day change by calculating the number of days required for the daily change in risk of each to decline 95% from its maximum daily decline after discharge.

Relative risks of admission and death

We characterized the extent to which the risks of hospital admission and death are higher among patients recently discharged from hospital compared with the general elderly population. This was done by calculating the cumulative incidence of readmission to hospital and death after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia and comparing these results with the cumulative incidence of hospital admission and death among all beneficiaries in the Medicare fee for service comparator population.

Statistical analyses

Daily risks of readmission and death

We fit separate survival models for the risk of first readmission to hospital and death after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. The analytic approach differed based on the presence or absence of competing risk. In models that estimated the daily risk of first readmission to hospital, we considered death before first readmission to hospital as a competing risk and therefore calculated the subdistribution hazard—an unconditional hazard—that was derived from the cumulative incidence function by Fine and Gray and corrects for competing risk.20 This approach allows the estimation of unconditional risk after consideration of competing risks. We censored data at planned readmission19 or at one year after the index hospitalization, whichever occurred first. In models that estimated the daily risk of death, there was no competing risk and we censored data at one year after the index hospitalization. In the absence of competing risk, we calculated hazard estimates for death using the life table method.

We used Gray’s test to compare the cumulative incidence of first readmission to hospital and its corresponding hazard across cohorts with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia.21 To compare the cumulative incidence of death and its corresponding hazard across the cohorts, we used the log rank test. We used the bootstrap method with 2000 iterations to construct 95% confidence intervals for the time required for the daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death to decline 50% from their maximum hazards after discharge for each of the three index conditions.

To characterize the daily change in risk of first readmission to hospital and death with time after hospital discharge, we calculated differences in kernel-smoothed hazard estimates22 between each day and the preceding day. For each day after the maximum hazard, we divided the daily change in risk by its maximum daily decline after discharge. We used the bootstrap method with 2000 iterations to construct 95% confidence intervals for the number of days required for the daily change in risk to decline 95% from its maximum daily decline after discharge.

Relative risks of admission and death

We calculated the one year cumulative incidence of hospital admission and one year cumulative incidence of death among all beneficiaries in the Medicare fee for service comparator population in 2009. We prorated these results by day and compared them with the cumulative incidence of hospital readmission and cumulative incidence of death by day (1-365) after discharge from index hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. We did this by calculating the relative risk of hospital admission and death between study cohorts and the Medicare fee for service comparator population over the first 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days after discharge.

To make study and comparator populations more similar, we directly standardized cumulative incidence by age, sex, and race. We used three age categories (65-74, 75-84, ≥85), two sex categories, and three race categories (white, black, other). We used the Fine and Gray method to derive the cumulative incidence function of first readmission to hospital for each age-sex-race stratum in the heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia cohorts.20 We derived the cumulative incidence of death for each age-sex-race stratum using the life table method. We directly standardized the study populations to the Medicare fee for service comparator population to calculate the age-sex-race standardized cumulative incidence of hospital admission and death.

AFH, ZL, and HL conducted analyses using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

For readmission analyses, we included 1 462 453 hospitalizations for heart failure (4735 hospitals), 561 926 for acute myocardial infarction (4423 hospitals), and 1 125 234 for pneumonia (4767 hospitals). Supplementary figure 1 shows the reasons for excluding hospitalizations. The cohorts were comprised, respectively, of 972 339, 516 380, and 951 084 unique patients who were used in mortality analyses. The comparator population of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries included 27 764 699 people. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the cohorts.

Table 1.

Personal characteristics of study cohorts and comparator population. Values are percentages unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Study cohorts | Medicare fee for service population (n=27 764 699) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | Acute myocardial infarction | Pneumonia | |||||||

| Readmission (n=1 462 453) | Death (n=972 339) | Readmission (n=561 926) | Death (n=516 380) | Readmission (n=1 125 234) | Death (n=951 084) | ||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 80.5 (8.2) | 80.7 (8.2) | 78.7 (8.4) | 78.6 (8.4) | 80.3 (8.2) | 80.3 (8.2) | 75.5 (7.9) | ||

| Women | 55.9 (n=817 059) | 56.2 (n=545 923) | 50.0 (n=280 986) | 50.1 (n=258 883) | 55.1 (n=620 015) | 55.7 (n=529 504) | 56.7 (n=15 731 675) | ||

| Race: | |||||||||

| White | 83.0 (n=1 213 963) | 84.9 (n=825 341) | 88.0 (n=494 226) | 88.2 (n=455 462) | 88.8 (n=998 925) | 88.7 (n=843 191) | 86.7 (n=24 074 306) | ||

| Black | 12.5 (n=182 593) | 10.8 (n=105 173) | 7.7 (n=43 033) |

7.5 (n=38 612) | 6.7 (n=74 854) | 6.8 (n=64 694) | 7.6 (n=2 118 292) | ||

| Other | 4.5 (n=65 897) | 4.3 (n=41 825) | 4.4 (n=24 667) | 4.3 (n=22 306) | 4.6 (n=51 455) | 4.5 (n=43 199) | 5.7 (n=1 572 101) | ||

Within one year of discharge, readmission to hospital and death, respectively, occurred following 67.4% and 35.8% of hospitalizations for heart failure, 49.9% and 25.1% for acute myocardial infarction, and 55.6% and 31.1% for pneumonia. The daily risk of first readmission to hospital 30 days after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia was 0.7%, 0.4%, and 0.4%, respectively. The daily risk of death 30 days after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia was 0.2%, 0.2%, and 0.2%, respectively. Table 2 presents the daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death at 7, 15, 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days after discharge.

Table 2.

Daily risk of first readmission to hospital and death after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia

| Discharge diagnosis and outcome | % Experiencing outcome on specific day after hospital discharge (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 90 | Day 180 | Day 365 | |

| Heart failure: | |||||||

| First readmission | 1.17 (1.16 to 1.18) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.93) | 0.67 (0.66 to 0.68) | 0.47 (0.46 to 0.48) | 0.36 (0.35 to 0.37) | 0.22 (0.22 to 0.23) | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.13) |

| Death | 0.34 (0.34 to 0.35) | 0.29 (0.28 to 0.30) | 0.23 (0.22 to 0.24) | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.17) | 0.14 (0.13 to 0.14) | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.09) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.08) |

| Acute myocardial infarction: | |||||||

| First readmission | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.60 (0.59 to 0.62) | 0.41 (0.39 to 0.42) | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 0.21 (0.20 to 0.22) | 0.13 (0.12 to 0.14) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.08) |

| Death | 0.33 (0.32 to 0.34) | 0.22 (0.21 to 0.23) | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.17) | 0.11 (0.10 to 0.12) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.08) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.06) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Pneumonia: | |||||||

| First readmission | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.87) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) | 0.44 (0.43 to 0.45) | 0.30 (0.30 to 0.31) | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 0.17 (0.16 to 0.17) | 0.11 (0.10 to 0.12) |

| Death | 0.34 (0.33 to 0.35) | 0.28 (0.27 to 0.29) | 0.21 (0.20 to 0.22) | 0.12 (0.12 to 0.13) | 0.10 (0.10 to 0.11) | 0.08 (0.08 to 0.09) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.05) |

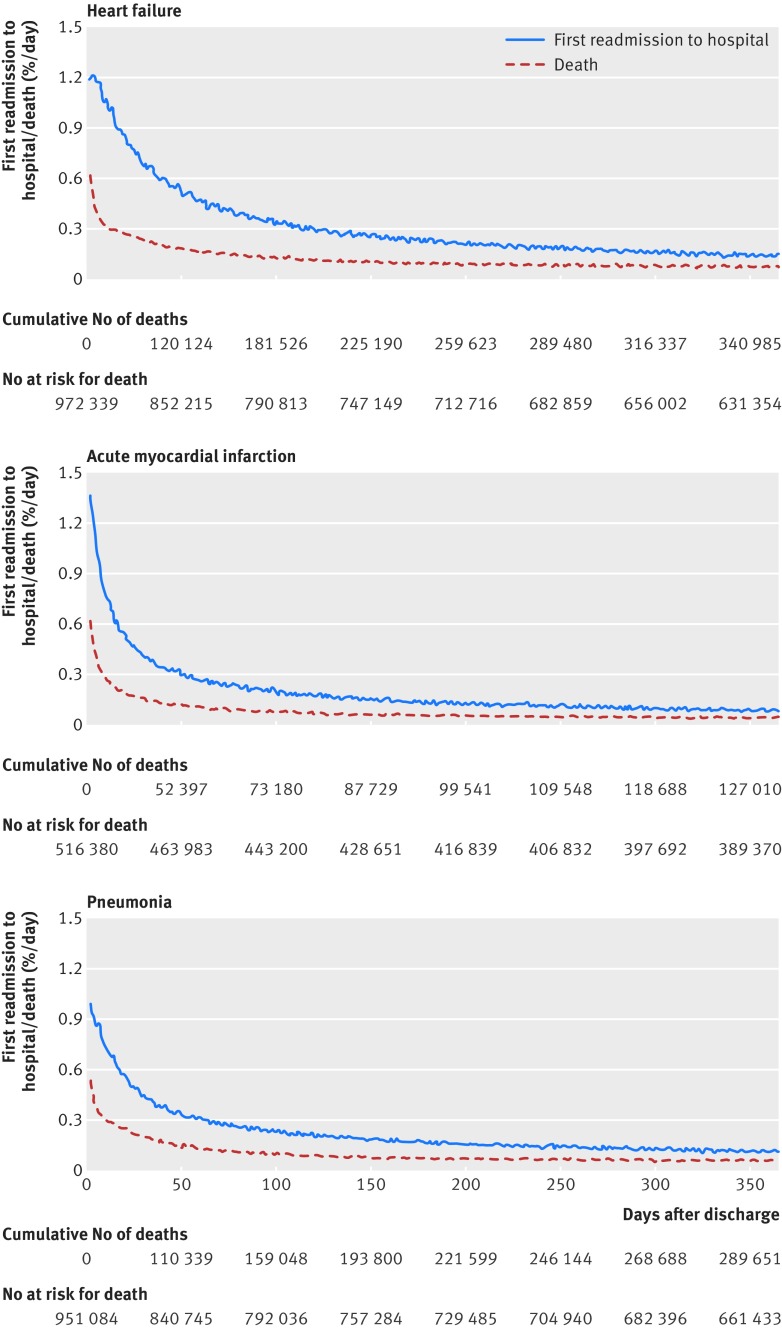

Although daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death both declined with time, the decline was relatively slower for first readmission to hospital for all three conditions (fig 1 ). After hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia, risk of first readmission to hospital was highest on day 3, day 2, and day 2 after discharge, respectively, and declined 50% after day 38, day 13, and day 25 (table 3). Risk of death was highest on day 1 for patients with all three conditions and declined 50% after day 11, day 6, and day 10 after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia, respectively.

Fig 1 Risks (hazard ratios) of first readmission to hospital and death for one year after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia

Table 3.

Representative time points describing trajectories of risk after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia

| Discharge diagnosis and outcome | Days for risk level to decline 50% (95% CI) | Days for daily change in risk to decline 95% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure: | ||

| First readmission | 38 (36 to 39) | 45 (33 to 80) |

| Death | 11 (10 to 12) | 21 (15 to 35) |

| Acute myocardial infarction: | ||

| First readmission | 13 (13 to 15) | 38 (33 to 46) |

| Death | 6 (6 to 7) | 19 (17 to 27) |

| Pneumonia: | ||

| First readmission | 25 (23 to 27) | 45 (39 to 66) |

| Death | 10 (9 to 10) | 21 (14 to 29) |

Daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death were different across the three index conditions (P<0.001) and declined most quickly for acute myocardial infarction and most slowly for heart failure (see supplementary figure 2). Supplementary figure 3 presents the cumulative incidence function of first readmission to hospital and its competing risk of death.

Daily risks of first readmission to hospital and death approached plateau periods of minimal day to day change by seven weeks after hospitalization for all three conditions (table 3). After hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia, the number of days required for the daily change in risk of first readmission to decline 95% from its maximum daily decline after discharge was 45, 38, and 45, respectively (table 3). The number of days required for the daily change in risk of death to decline 95% was 21, 19, and 21, respectively.

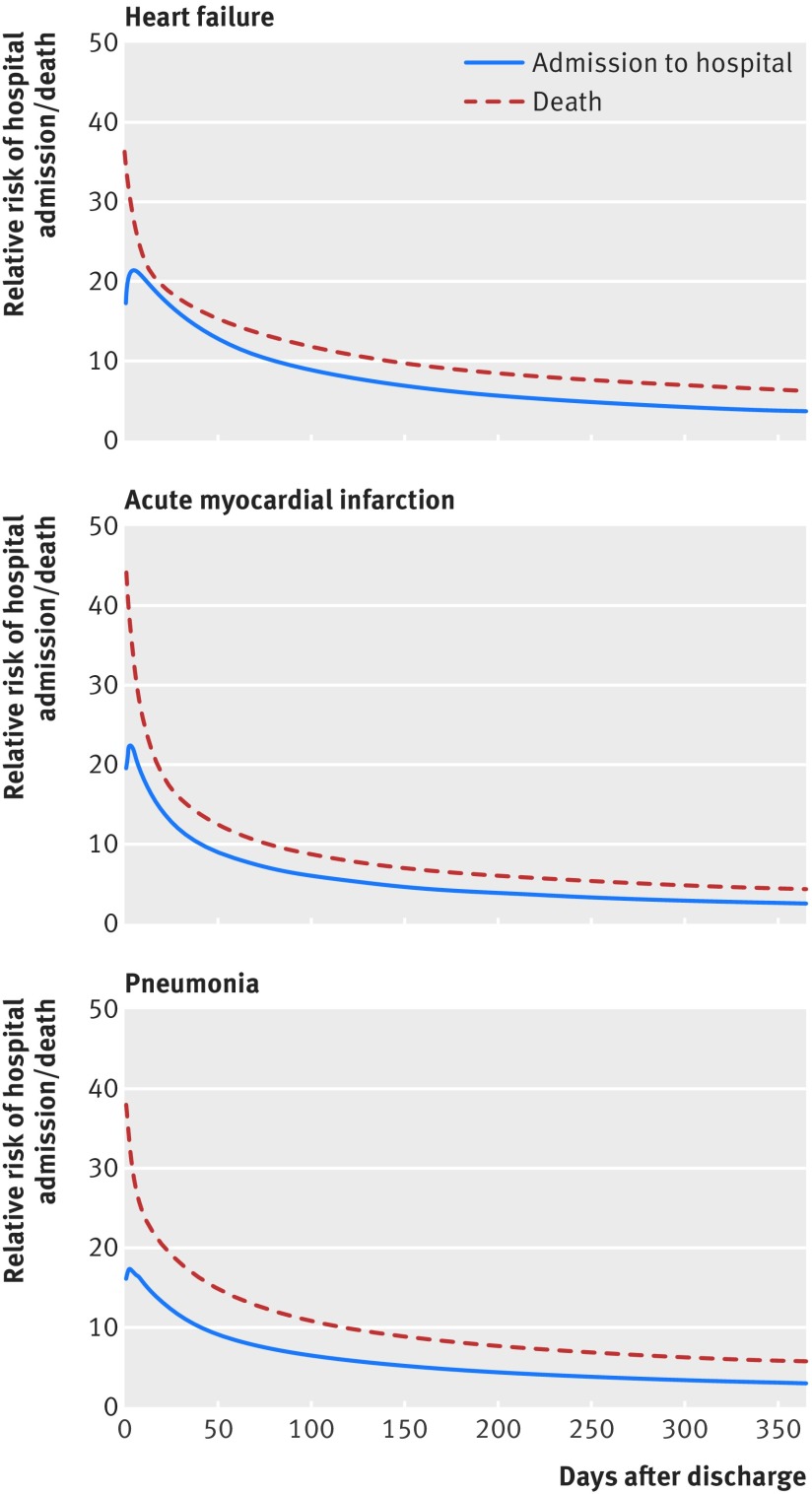

Risk after hospitalization was noticeably higher than among the comparator population of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries throughout the year after hospital discharge (fig 2 ). For example, after hospitalization for heart failure, the age-sex-race standardized relative risk of hospital admission was greater by a factor of 16, 12, 9, 6, and 4 over the first 30, 60, 90, 180, and 365 days after discharge. Relative risks were larger for the endpoint of death (see supplementary table 2).

Fig 2 Relative risk of hospital admission and death in post-discharge population compared with Medicare fee for service comparator population for one year after hospital discharge for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. In 2009, the 30 day and one year cumulative incidence of hospital admission in the Medicare fee for service comparator population was 1.58% and 19.3%, respectively. The 30 day and one year cumulative incidence of death was 0.5% and 5.9%, respectively

Discussion

Through study of a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries initially hospitalized with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia, we have defined explicit trajectories of risk for the full year after hospital discharge. Unlike rates of readmission and mortality, these trajectories convey how absolute risks change over time. Our major finding is that patients remain at increased risk of acute health events necessitating readmission to hospital for an extended time after hospital discharge that is longer than the period in which they are at increased risk of death. We also found that risk trajectories vary by admitting diagnosis. For example, risk of first readmission to hospital takes 38 days to decline by 50% after hospitalization for heart failure and 13 days to decline by 50% after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Yet within seven weeks of hospitalization, the risks of both first readmission to hospital and death were significantly lower than at discharge and were no longer rapidly changing for all three conditions, suggesting that patients surviving to this time while avoiding readmission to hospital may have progressed to a new phase of recovery with reduced vulnerability. As the US health system increasingly focuses on improving long term health13 23 and personalizing interventions, explicit descriptions of the time dependent nature of risk after hospitalization can enhance patients’ understanding of recovery from acute illness and better align interventions designed to reduce adverse outcomes with the periods of greatest risk for patients.

Our findings suggest that the risks of readmission to hospital and death are increased well beyond the initial month after hospital discharge. For example, after hospitalization for heart failure, the absolute risk of first readmission to hospital on day 30 after hospital discharge is 0.7%. For perspective, the daily risk of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 score of 2, a group traditionally thought to benefit from oral anticoagulation, is only 0.01%.24 Moreover, the relative risks of hospital admission and death were considerably higher after hospital discharge than among the general elderly population for the full year after hospitalization, likely due to the combined effects of chronic disease, acute illness, the hospital environment, and the social and environmental settings to which patients return. These findings suggest that patients should remain vigilant for deterioration in health well beyond the first month after hospital discharge and should expeditiously report any concerns to their healthcare providers. Findings also suggest that physicians and hospitals should provide follow-up care that is timely,25 longitudinal,26 and comprehensive,27 28 29 with special attention to the completion of advanced care directives, rates of which are low even among patients admitted to hospital.30

Our findings may also illuminate different stages of recovery after hospitalization for patients who neither die nor are readmitted. The initial period of extended risk may relate to a post-hospital syndrome5 derived from the synergistic effects of acute illness, comorbidities,31 32 and potential toxicities of hospitalization, such as immobility,33 34 sleep deprivation,35 poor nutrition,36 pain,37 secondary illnesses,38 and iatrogenic events.39 This first phase of recovery may last up to seven weeks, after which the risks of first readmission to hospital and death have significantly declined and are no longer rapidly changing. Patients surviving to this time without a major adverse event may have therefore progressed to a new stage of recovery with improved physiologic function and reduced vulnerability to deterioration. The serial assessment after hospitalization of specific biomarkers, physiologic variables, and physical performance measures may further explain empiric trajectories of risk.

Our demonstration that the daily risks of readmission to hospital and death decline at different rates over time additionally suggests that these adverse outcomes result from different factors and may require different interventions to be most effectively reduced. Depending on diagnosis, we found that risk of readmission to hospital declined 50% within 13-39 days after hospital discharge, whereas the risk of death required only 6-12 days for a similar relative decline. These differences may explain why models predicting short term mortality among patients admitted to hospital have generally been more successful than models predicting short term readmission. As death is more likely to occur relatively soon after discharge, models that include markers for illness severity at the time of hospital presentation11 40 have shown excellent ability to predict short term mortality. In contrast, models for predicting short term readmission to hospital, when restricted to similar markers of illness acuity, have performed substantially worse.41 42 43 This may not be surprising in light of our findings, as the relatively prolonged period of increased risk of readmission to hospital may be more sensitive to factors with effects beyond the acute period of illness, such as cognitive impairment,44 medication compliance,45 social factors,46 and follow-up care.25 In contrast, the relatively short period of increased mortality risk may relate primarily to the effects of acute illness as well as to available interventions provided in the inpatient setting. The particularly high mortality risk immediately after acute myocardial infarction may specifically relate to its pathophysiologic association with sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia and acute structural complications of the heart muscle.47

Ultimately, our findings can help align post-discharge interventions with the periods of greatest risk for patients. Absolute risks may be used to guide the intensity of post-discharge care, whereas the rate of decline in risk with time may be used to guide the duration of follow-up. Organizations with scarce resources for preventing adverse events after hospital admission, such as accountable care organizations, may therefore dynamically alter the duration and intensity of follow-up to match each patient’s condition specific risk for death and readmission to hospital by using data derived from the electronic health record. Predicted risk trajectories can be fine tuned as additional data are generated during outpatient follow-up. This more nuanced approach to post-discharge care may grow in importance as health providers seek efficient strategies that minimize patient risk for extended periods after hospitalization. Future models with more granular clinical information can show if risk trajectories are modified by particular patient characteristics.

Strengths of this study

Our study is the first to characterize risk as it dynamically changes on a day by day basis in the year after hospitalization. Although previous work has accurately characterized rates of adverse outcomes in the year after hospital discharge,1 11 the calculation of rates obscures how absolute risk changes in dynamic ways for different conditions and outcomes over time. In addition, we calculated and compared trajectories of risk for both readmission to hospital and death using a competing risk methodology. In contrast, previous work has largely been restricted to analyzing only one of these outcomes,1 11 thereby precluding their comparison. Finally, we provide patients, providers, and policy makers with an alternative way to comprehend the magnitude and duration of risk after hospitalization by comparing risk among patients recently discharged from hospital with people in the general elderly population matched for age, sex, and race. The results from these analyses can help patients, clinicians, and health systems set realistic goals and plan for appropriate care.

Additional factors need to be considered when interpreting this study. Firstly, data were limited to Medicare fee for service beneficiaries, so findings may not apply to other populations. Nevertheless, our study includes most elderly patients in the United States, who are the focus of current federal policies.13 Secondly, we relied on administrative data and were unable to incorporate clinical variables into our models. However, our goal was to identify general trends in risk, and claims data are ideal for this purpose. Thirdly, we used administrative codes to identify index hospital admissions. However, claims data have been shown to be accurate for cardiovascular and pulmonary diagnoses.48 49 Fourthly, we could have chosen an alternate threshold other than a 95% reduction in rate to define the period after which risk exhibits minimal day to day change. However, as our goal was to identify the time after which risk is largely invariant from a clinical perspective, we believe that a 95% reduction in rate of decline would reasonably meet this standard. In addition, we were not certain a priori that risk would ever become totally invariant, with a slope of zero in the risk trajectory curve. Fifthly, we did not define risk trajectories separately for patients receiving or not receiving hospice care. As our aim was to generate generalizable estimates of risk among patients recently discharged from hospital, the exclusion of patients expected to have the worst outcomes would bias results towards inappropriately low overall estimates of population risk.

Conclusions

We defined trajectories of risk for the full year after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia and found that absolute risk is noticeably increased after hospitalization and variably declines over time by discharge diagnosis and outcome. Risk of death declines relatively rapidly, whereas the risk of readmission to hospital remains increased for longer. Although prolongation of risk is most pronounced after hospitalization for heart failure, patients admitted with any of the three conditions are at considerably higher risk of adverse outcomes than the general elderly population for the full year after hospital discharge. Yet risk ultimately plateaus by seven weeks after discharge, suggesting that patients reaching this point without having been readmitted may have entered a new and less vulnerable stage of recovery. Patients should therefore remain vigilant for deterioration in health well beyond the first month after hospitalization and maintain extended ties with their healthcare providers. Physicians and hospitals should use knowledge of absolute risk to align interventions designed to reduce adverse outcomes after hospital discharge with the highest risk periods for patients.

What is already known on this topic

Patients are at high risk for readmission to hospital and death in the month after discharge

However, little is known about how these risks dynamically change over time for the full year after hospitalization

Accurate information on risk is needed for patients and hospitals to set realistic goals and plan for appropriate care

What this study adds

Risk declines slowly after discharge from hospital and is increased for months compared with people who have not been hospitalized

Specific risk trajectories vary by discharge diagnosis and outcome

Patients should remain vigilant for deterioration in health for an extended time after discharge from hospital

Health providers can use knowledge of absolute risks and their changes over time to better align interventions designed to reduce adverse outcomes after discharge from hospital with the highest risk periods for patients

Contributors: KD and HMK devised the study concept and design, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the paper; they are the guarantors. AFH performed all statistical analyses. AFH, VTK, ZL, JSR, LIH, NK, LGS, HL, and S-LTN analyzed and interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HMK obtained funding, acquired the data, and supervised the study. KD and HMK had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Funding: KD, JSR, and LIH are supported by grants K23AG048331, K08AG032886, and K08AG038336, respectively, from the National Institute on Aging and American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B Beeson career development award program. HMK is supported by grant 1U01HL105270-04 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the American Federation for Aging Research.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for the submitted work; VTK and HL have no financial relationships in the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work; KD, AFH, ZL, JSR, LIH, NK, LGS, S-LTN, and HMK work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the United States to develop and maintain performance measures; JSR is a member of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health; HMK is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth; JSR and HMK are the recipients of research grants from Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson through Yale University;.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee (institutional review board) at Yale University.

Data sharing: No additional data available owing to data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Policy.

Transparency: The lead authors (KD and HMK) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h411

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary information

References

- 1.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, Chen J, Vidan MT, Normand SL, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993-2006. JAMA 2010;303:2141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drye EE, Normand SL, Wang Y, Ross JS, Schreiner GC, Han L, et al. Comparison of hospital risk-standardized mortality rates calculated by using in-hospital and 30-day models: an observational study with implications for hospital profiling. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, Vaccarino V, Wang Y, Radford MJ, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:99-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JS, Chen J, Lin Z, Bueno H, Curtis JP, Keenan PS, et al. Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:97-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernheim SM, Grady JN, Lin Z, Wang Y, Wang Y, Savage SV, et al. National patterns of risk-standardized mortality and readmission for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Update on publicly reported outcomes measures based on the 2010 release. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:459-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun S, Tu JV, Wijeysundera HC, Austin PC, Wang X, Levy D, et al. Lifetime analysis of hospitalizations and survival of patients newly admitted with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:414-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng TH, Hung J, Knuiman M, Stewart S, Arnolda L, Jacobs I, et al. Trends in long-term cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in men and women with heart failure of ischemic versus non-ischemic aetiology in Western Australia between 1990 and 2005. Int J Cardiol 2012;158:405-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA 2003;290:2581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), statistical brief 66. AHRQ, 2009. 2014. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb66.jsp. [PubMed]

- 13.Kocher RP, Adashi EY. Hospital readmissions and the Affordable Care Act: paying for coordinated quality care. JAMA 2011;306:1794-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Han LF, Ingber MJ, Roman S, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation 2006;113:1693-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, Drye EE, Bhat KR, Ross JS, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2008;1:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, Desai MM, Han LF, Rapp MT, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:243-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bratzler DW, Normand SL, Wang Y, O’Donnell WJ, Metersky M, Han LF, et al. An administrative claims model for profiling hospital 30-day mortality rates for pneumonia patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e17401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenauer PK, Normand SL, Drye EE, Lin Z, Goodrich K, Desai MM, et al. Development, validation, and results of a measure of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. J Hosp Med 2011;6:142-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Planned readmission algorithm. Version 2.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Mar 2013.

- 20.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Statist Assoc 1999;94:496-509. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat 1988;16:1141-54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasser T, Müller HG. Kernel estimation of regression functions. Smoothing techniques for curve estimation. Lect Notes Math 1979;757:23-68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutler DM, Ghosh K. The potential for cost savings through bundled episode payments. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001;285:2864-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2010;303:1716-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sochalski J, Jaarsma T, Krumholz HM, Laramee A, McMurray JJ, Naylor MD, et al. What works in chronic care management: the case of heart failure. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:179-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno J, Lynn J, Wenger N, Phillips RS, Murphy DP, Connors AF, et al. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: effectiveness with the patient self-determination act and the SUPPORT intervention. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:500-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, Weller W, Niefeld M, Herbert R, et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1226-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McManus DD, Nguyen HL, Saczynski JS, Tisminetzky M, Bourell P, Goldberg RJ. Multiple cardiovascular comorbidities and acute myocardial infarction: temporal trends (1990-2007) and impact on death rates at 30 days and 1 year. Clin Epidemiol 2012;4:115-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, Wolfe R, Evans WJ. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA 2007;297:1772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA 2004;292:2115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoder JC, Staisiunas PG, Meltzer DO, Knutson KL, Arora VM. Noise and sleep among adult medical inpatients: far from a quiet night. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:68-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan DH, Sun S, Walls RC. Protein-energy undernutrition among elderly hospitalized patients: a prospective study. JAMA 1999;281:2013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donovan M, Dillon P, McGuire L. Incidence and characteristics of pain in a sample of medical-surgical inpatients. Pain 1987;30:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loo VG, Bourgault AM, Poirier L, Lamothe F, Michaud S, Turgeon N, et al. Host and pathogen factors for Clostridium difficile infection and colonization. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1693-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med 1991;324:370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306:1688-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amarasingham R, Moore BJ, Tabak YP, Drazner MH, Clark CA, Zhang S, et al. An automated model to identify heart failure patients at risk for 30-day readmission or death using electronic medical record data. Med Care 2010;48:981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capelastegui A, Espana Yandiola PP, Quintana JM, Bilbao A, Diez R, Pascual S, et al. Predictors of short-term rehospitalization following discharge of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2009;136:1079-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dodson JA, Truong TT, Towle VR, Kerins G, Chaudhry SI. Cognitive impairment in older adults with heart failure: prevalence, documentation, and impact on outcomes. Am J Med 2013;126:120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Network for Excellence in Health Innovation. Improving medication adherence and reducing readmissions. NEHI issue brief. October 2012. 2015. www.nacds.org/pdfs/pr/2012/nehi-readmissions.pdf.

- 46.Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, Lo M, Yunyongying P, Stieglitz H, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson WG, Linssen GC, Havenith MG, Brugada P, Wellens HJ. The spectrum of death after myocardial infarction: a necropsy study. Am Heart J 1989;118:1182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care 2005;43:480-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skull SA, Andrews RM, Byrnes GB, Campbell DA, Nolan TM, Brown GV, et al. ICD-10 codes are a valid tool for identification of pneumonia in hospitalized patients aged > or = 65 years. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:232-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information