Abstract

An important step in the biosynthesis of many proteins is their partial or complete translocation across the plasma membrane in prokaryotes or the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in eukaryotes 1. In bacteria, secretory proteins are generally translocated after completion of their synthesis by the interplay of the cytoplasmic ATPase SecA and a protein-conducting channel formed by the SecY complex 2. How SecA moves substrates through the SecY channel is unclear. However, a recent structure of a SecA-SecY complex raises the possibility that the polypeptide chain is moved by a two-helix finger domain of SecA that is inserted into the cytoplasmic opening of the SecY channel 3. Here, we have used disulfide-bridge crosslinking to show that the loop at the tip of the two-helix finger interacts with a polypeptide chain right at the entrance into the SecY pore. Mutagenesis demonstrates that a tyrosine in the loop is particularly important for translocation, but can be replaced by some other bulky, hydrophobic residues. We propose that the two-helix finger of SecA moves a polypeptide chain into the SecY channel with the tyrosine providing the major contact with the substrate, a mechanism analogous to that suggested for hexameric, protein-translocating ATPases.

SecA uses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to “push” polypeptides through the SecY channel 4. The channel has an hourglass-shaped pore that consists of funnels on the cytoplasmic and external sides of the membrane 5, 6. The constriction of the pore is located near the middle of the membrane and is formed from a “pore ring” of hydrophobic amino acids that project their side chains radially inward. A short helix plugs the external funnel in the closed state of the channel 5 and is displaced during translocation 7, 8. The channel-interacting SecA ATPase contains two RecA-like nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) that bind the nucleotide at their interface and move relative to one another during the ATP hydrolysis cycle. In addition, SecA contains a polypeptide-crosslinking domain (PPXD), a helical wing domain (HWD), and a helical scaffold domain (HSD) 9. In a recent structure of the SecA-SecY complex 3, two helices of SecA’s HSD form a “two-helix finger” that is inserted into the cytoplasmic funnel of the SecY channel. The loop connecting the two helices is located right above the SecY pore, suggesting that it interacts with a polypeptide chain and pushes it into the SecY pore 3.

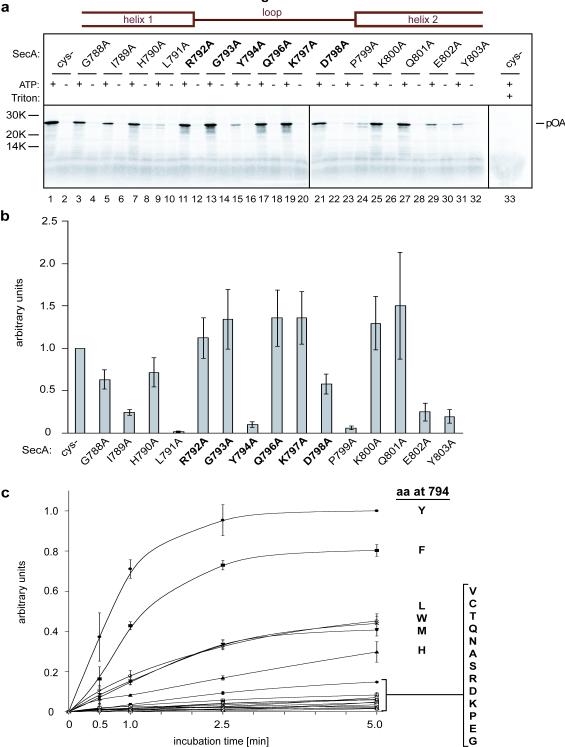

To test these ideas, we first investigated which residues of SecA’s two-helix finger are important for translocation. Because mutations in this region compromise translocation 10-12, we performed a systematic analysis by changing residues 788 to 803 individually to alanines. These residues span the C-terminus of the first helix of the finger domain (residues 788-791), the entire loop between the helices (residues 792-798), and the N-terminus of the second helix (residues 799 to 803). The SecA mutants were purified and tested for translocation of the substrate proOmpA (pOA). In vitro synthesized 35S-labeled pOA was incubated with SecA, ATP, and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex, and translocation of pOA was determined by protease digestion (Fig. 1a; quantification in Fig. 1b). The results show that two residues in the helices are particularly important for translocation: Leu791 at the end of the first helix (Fig. 1a, lane 9 versus lane 1), which probably interacts with the SecY loop between trans-membrane (TM) segments 6 and 7 (ref. 3), and Pro799 at the beginning of the second helix (lane 23), which may serve to cap the helix. Glu802 and Tyr803 in the second helix are also required for full activity (lanes 29 and 31), perhaps because they stabilize the structure of the two-helix finger 13. Within the loop, the only important residue is Tyr794 (Fig. 1a, lane 15; Fig. 1b). Similar results were obtained with cysteine mutations in the loop region (Supplementary Fig. S1). We then mutated the tyrosine residue to different amino acids. The translocation rates obtained with purified SecA mutants show that the tyrosine can be replaced by a few other amino acids with bulky, hydrophobic side chains (Tyr>Phe>Leu≅Trp≅Met>His>Val), whereas all amino acids with small or charged side chains have very low activity (Fig. 1c). The tyrosine residue is found in 80.3% of all SecAs (601 out of 748 SecAs listed in the database), but other bulky, hydrophobic residues are occasionally observed (Supplementary Tables 1, 2; the infrequently found histidines might be uncharged at appropriate pH). Interestingly, 18 listed SecAs have small or hydrophilic amino acids at the critical position that would be expected to cause low translocation activity, but in all but one case (a SecA with an arginine), there is another SecA in the same organism with a conventional bulky, hydrophobic residue (Supplementary Table 3). In Streptococcus gordonii, the non-conventional SecA (SecA2) has a threonine and cooperates with a specialized SecY channel and other factors to export just one substrate, a 3072 residue, serine-rich cell surface adhesin that is glycosylated in the cytosol before secretion; the conventional SecA1 has a tyrosine and is responsible for the export of all other substrates 14. A similar situation may apply to other bacteria that contain both a conventional and non-conventional SecA 15.

Figure 1. An essential tyrosine at the tip of the two-helix finger.

a, Residues in SecA’s two-helix finger were individually mutated to alanines. Position 795 is an alanine in the wild type and cysteine-lacking (Cys-) proteins and therefore remained unchanged. Residues in the helices and loops are indicated in the scheme on top and loop residues are also highlighted in bold. The mutants were purified and tested for translocation activity by incubation for 5 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of ATP with in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled pOA and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex. After treatment with proteinase K, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. The Cys- mutant served as positive control. For each mutant, samples were also treated with protease in the presence of Triton X-100 to disrupt the membrane (shown here in lane 33 for the Cys- mutant). b, Quantification of three experiments performed as in a (mean and standard errors). The data were normalized with respect to the Cys- mutant. c, Translocation kinetics of SecA mutants in which Tyr794 was replaced with other residues (in one-letter code). Shown are the mean and standard deviation of three experiments, normalized to the 5-min data point of the Cys- mutant, which has the wild type tyrosine (Y) in the loop.

Next we used disulfide crosslinking to investigate whether the loop at the tip of the two-helix finger of SecA interacts with a polypeptide chain during translocation. Because SecA interacts rather promiscuously with polypeptide chains in solution (unpublished results), we developed a strategy that allowed us to study interactions of a truly translocating polypeptide chain. We introduced two cysteines into the substrate pOA, one that would crosslink to the SecY channel, and another one that would crosslink to SecA (Fig. 2a). Double-crosslinks of pOA to both SecY and SecA would indicate interactions of a polypeptide chain that has engaged both translocation components.

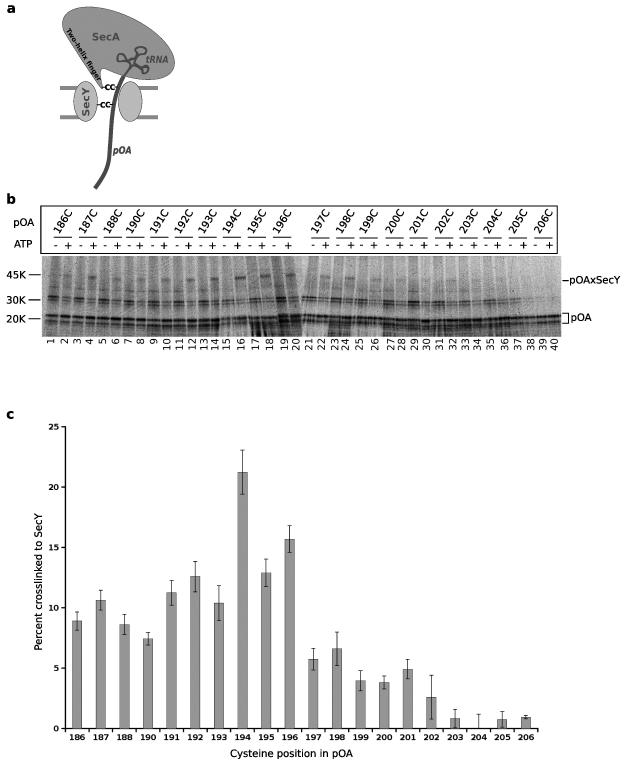

Figure 2. Contact of a translocation intermediate with the pore of SecY.

a, Scheme of the crosslinking strategy. A tRNA-associated fragment of 35S-proOmpA (pOA) was synthesized in vitro and translocated by SecA into the SecY channel. The bulky tRNA prevents complete translocation. Two cysteines (C) were introduced into pOA, one for crosslinking to a cysteine in the two-helix finger of SecA and one for crosslinking to a cysteine in SecY. b, Translocation substrates (pOA:tRNA) of 206 residues containing single cysteines at the indicated positions were incubated in the absence or presence of ATP with a cysteine-free SecA and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex. SecY carried a single cysteine in the pore ring at position 282. After oxidation with Cu2+-phenanthroline, the samples were treated with NEM and RNase A, and analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The positions of free and crosslinked pOA (pOA and pOAxSecY) are indicated. c, Quantification of three experiments performed as in b (mean and standard deviation).

We first determined the positions at which cysteines in pOA would crosslink to a cysteine introduced into the pore ring of E. coli SecY (position 282). pOA fragments of 206 amino acids, each containing a single cysteine, were synthesized by in vitro translation of a truncated mRNA in the presence of 35S-methionine. With no stop codon in the mRNA, the nascent polypeptide chain remains associated with the ribosome as peptidyl-tRNA, and can be released from the ribosome by treatment with urea (pOA:tRNA) 16. These pOA:tRNA substrates were then incubated with E. coli SecA lacking the endogenous cysteines 17, 18, ATP, and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex. The bulky tRNA at the C-terminus of the substrates prevents their complete translocation into the vesicles, thus generating translocation intermediates (Fig. 2a) 19. An oxidant was added and the formation of a disulfide bridge was analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 2b). Crosslinks between pOA and the pore residue of SecY were only seen in the presence of ATP, when the polypeptide chain was translocated by SecA into the channel (Fig. 2b). The strongest crosslinks were seen with cysteines at positions 186-196 of pOA (lanes 1-20; see quantification in Fig. 2c); residues that were closer than ten residues from the C-terminus gave only weak or no crosslinks, consistent with the idea that the tRNA moiety prevents the final residues from moving into the pore.

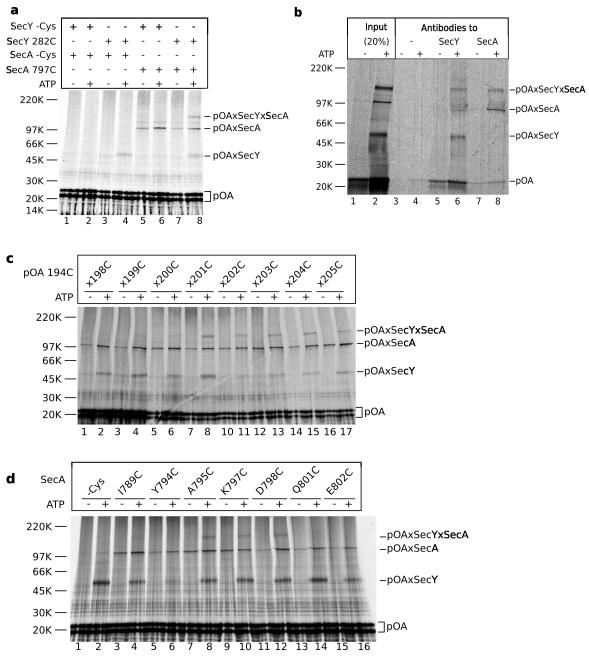

pOA residues not yet translocated into the SecY pore may be expected to interact with the two-helix finger of SecA, which is located right above the pore entrance 3 (Fig. 2a). We therefore used a pOA:tRNA substrate that contained a cysteine at position 194 for crosslinking to the pore position 282 in SecY (see Fig. 2b), and a cysteine at position 201 for crosslinking to position 797 near the tip of the two-helix finger of SecA. After incubation in the presence or absence of ATP, disulfide bridge formation was induced with an oxidant. A prominent double-crosslink was generated (Fig. 3a, lane 8), in addition to the single crosslinks to SecY and SecA. The double-crosslinks to SecY and SecA and the single crosslinks to SecY were dependent on the presence of ATP, whereas crosslinks to SecA were nucleotide-independent (Fig. 3a, lane 8 versus 7), reflecting the promiscuous interaction of SecA with non-translocating substrate. Double-crosslinks to SecY and SecA were not observed when either SecY or SecA lacked a cysteine (Fig. 3a, lanes 1-6). The identity of the crosslinked band was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation experiments; the high-molecular weight band could be precipitated with either SecA or SecY antibodies (Fig. 3b, lanes 6 and 8).

Figure 3. The two-helix finger of SecA interacts with a translocating substrate.

a, Translocation substrates (pOA:tRNA) of 206 residues containing cysteines at positions 194 and 201 were incubated with SecA and proteoliposomes containing SecY complex in the absence or presence of ATP. The SecA proteins either lacked a cysteine or contained a cysteine at the tip of the two-helix finger (position 797). SecY lacked a cysteine or contained a cysteine in the pore ring (position 282). After oxidation with Cu2+-phenanthroline, the samples were treated with NEM and RNase A, and analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The positions of free and crosslinked pOA (pOA, pOAxSecY, pOAxSecA, and pOAxSecYxSecA) are indicated. b, As in a, but the proteoliposomes were sedimented before addition of the oxidant. SecA contained a cysteine at position 797. After solubilization in DDM, 20% of each sample was analyzed directly (lanes 1 and 2), while the remainder was incubated with protein G beads either without antibody or with SecA- or SecY- antibodies (lanes 3-8). c, As in a, but the proteoliposomes containing SecY with a cysteine at position 282 were incubated with a SecA mutant containing a single cysteine at position 797 and pOA:tRNA with a cysteine at position 194 and a second cysteine at the indicated position. The samples were sedimented before addition of the oxidant. d, As in c, but the proteoliposomes containing SecY with a cysteine at position 282 were incubated with pOA:tRNA containing cysteines at positions 194 and 201 and SecA mutants containing single cysteines at the indicated positions.

To confirm that the N- and C-terminal cysteines of pOA contact SecY and SecA, respectively, we varied the spacing between the two cysteines in pOA (Fig. 3c). We used a SecA mutant with a cysteine at position 797 in the two-helix finger, and pOA substrates with a cysteine at position 194 and a second, more C-terminal cysteine. The samples were incubated in the absence or presence of ATP, the membranes were sedimented, and disulfide bridge formation was induced with an oxidant. Double-crosslinks were observed when the second cysteine was placed at positions 201 to 205 (Fig. 3c, lanes 7-17), indicating that the final residues of pOA contact SecA’s two-helix finger. Positions further towards the N-terminus did not give double-crosslinks (positions 198-200; lanes 1-6), consistent with the expectation that they have already passed the two-helix finger of SecA and are located further inside the SecY channel.

Next, we determined the region of the two-helix finger that contacts the pOA substrate. We placed single cysteines at various positions in the finger of SecA and used a pOA substrate with cysteines at positions 194 and 201. The most prominent double-crosslinks were observed with positions 795, 797, and 798 (Fig. 3d, lanes 8, 10, and 12). These positions are located at the tip of the two-helix finger, precisely where a polypeptide chain is predicted to pass according to the SecA-SecY structure 3. Positions in the two helices, which are further away from the fingertip, did not give crosslinks (Fig. 3d, lanes 4, 14, 16). Although some of the SecA mutants translocated pOA more slowly than wild type SecA (Supplementary Fig. S1), the incubation time was sufficient to generate translocation intermediates, as indicated by the appearance of ATP-dependent SecY crosslinks (Fig. 3d). Replacement of the tyrosine at the fingertip with cysteine severely compromised translocation (Fig. S1), and therefore only weak SecY and no SecY-SecA double crosslinks were observed (Fig. 3d, lane 6). However, because the mutant is not entirely inactive, in some experiments weak SecY and double crosslinks were seen (data not shown), indicating that this position also contacts the polypeptide chain. Taken together, these results indicate that a translocating polypeptide chain passes from the tip of the two-helix finger into the SecY pore. Because the double-crosslinks could be generated when the two cysteines in pOA were only seven residues apart (Fig. 3c; residues 201 and 194), the translocating polypeptide chain must be in an extended conformation to span the distance of 20-25Å between the fingertip of SecA and the pore ring of SecY. Given that even the most C-terminal residues of pOA can crosslink to the two-helix finger, it appears that most of the polypeptide chain has been pushed into the channel.

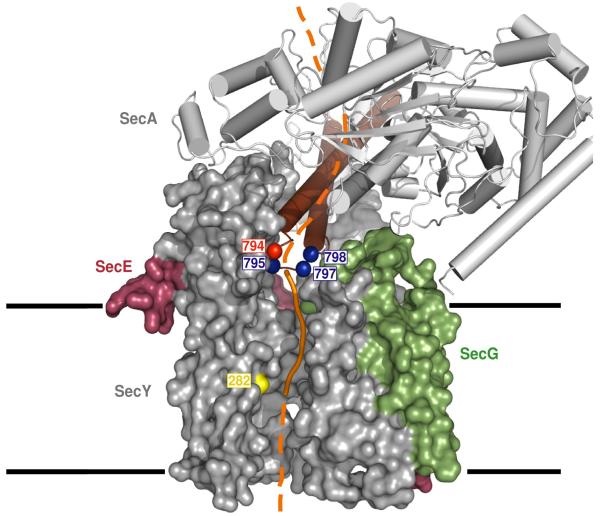

Our crosslinking experiments show that a translocating polypeptide chain passes directly from the tip of the two-helix finger into the SecY pore (Fig. 4). The polypeptide chain is probably positioned above the pore entrance by a clamp generated by the PPXD, the NBD2, and the HSD 3 (Fig. 4). We propose that the finger domain moves up and down during the ATP hydrolysis cycle and pushes the polypeptide into the SecY channel. The finger could interact with the polypeptide chain upon ATP-binding to SecA, and release the chain and reset following ATP-hydrolysis. In support of this mechanism, the ADP-bound state of SecA allows a polypeptide chain to slide back into the cytosol 20. We propose that the essential tyrosine (or other bulky, hydrophobic residue) in the loop at the tip of the finger domain contacts and drags the polypeptide chain, probably by interacting with amino acid side chains in the substrate. In the case of non-conventional SecAs (SecA2s), a small or hydrophilic amino acid might make specific contact with special features in their unique substrates, while at the same time preventing the transport of ordinary substrates. The proposed mechanism of SecA function is analogous to the one postulated for hexameric RecA-like ATPases, such as ClpX, ClpA, HslU, the 19S subunit of the proteasome, FtsH, and p97 21-25. In these cases, each monomer has a loop with a conserved tyrosine at its tip (tryptophan or phenylalanine in the case of p97 and FtsH, respectively), which contacts the polypeptide and transports it by moving up and down inside the central pore. As in the case of SecA, the aromatic residue in the loop can be changed to other bulky, hydrophobic residues, but not to small amino acids 22, 23, 26, 27. These similarities suggest that polypeptide movement occurs by a conserved, general mechanism.

Figure 4. Model of SecA translocating a polypeptide into the SecY channel.

A segment of a translocation substrate was modeled in orange in the T. maritima SecA-SecY complex structure (TM2b and residues 72-76 were removed for clarity) 3. The segment from the tip of the two-helix finger of SecA to the pore ring of SecY is shown as a solid line, the other segments as broken lines. Translocating proOmpA containing two cysteines could be double-crosslinked to position 282 of SecY (yellow) and to SecA positions in blue at the tip of the two-helix finger (brown). The essential tyrosine in the loop between the two helices is shown in red. SecY is shown as a space-filling model and SecA as a cartoon. The numbers correspond to the positions in E.coli SecA and SecY. The membrane boundaries are indicated.

METHODS SUMMARY

Point mutants of the N95 fragment of E. coli SecA, which lacks the non-essential C-terminus, were generated by PCR mutagenesis. The proteins were C-terminally His-tagged and purified by Ni2+-chelating chromatography. SecY complexes were purified 19 and reconstituted with E. coli polar lipids into phospholipid vesicles19, 28. Cysteine mutants were generated in a proOmpA fragment that lacked residues 175-296 and all endogenous cysteines. Fragments of 206 amino acids in length (numbering for the deletion construct) were synthesized by in vitro translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of 35S-methionine. The substrates (pOA:tRNA) were precipitated and dissolved in 8 M urea. For crosslinking, pOA:tRNA was incubated for 15 min at 37°C with SecY reconstituted into proteoliposomes, SecA, and ATP 19. In indicated cases, the membranes were sedimented before adding the oxidant. Oxidation was performed with Cu2+-phenanthroline, followed by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and RNaseA treatment. After solubilization in 1% dodecylmaltoside (DDM), the samples were subjected to non-reducing SDS-PAGE. For immunoprecipitation, the solubilized samples were incubated with protein G- beads containing pre-bound SecY- or SecA- antibodies 6. Translocation assays were performed as described 20.

METHODS

Mutagenesis and protein purification

Point mutants of E. coli SecA were generated by using the cysteine-lacking N95 fragment with a C-terminal His-tag (pET30b, Novagen) as the template for QuickChange (Stratagene) site-directed mutagenesis. SecA expression in BL21 (DE3) cells was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37°C. The proteins were purified with a Ni2+-chelating column, and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) 13. SecY complexes were purified as before 19 and reconstituted with E. coli polar lipids into phospholipid vesicles, as described 19, 28.

All endogenous cysteines of proOmpA were mutated and an internal fragment encoding residues 175-296 was deleted. For crosslinking, a fragment of 206 amino acids in length (numbering for the deletion construct) was generated by PCR with a 5’ primer containing the SP6 promoter sequence and a 3’ primer lacking a stop codon. After in vitro transcription, pOA fragments were translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of 35S-methionine (Promega). The proteins were precipitated with 3 volumes of 80% saturated ammonium sulfate (pH 7.5), pelleted at 22,000 x g for 15 min, and resuspended in the original volume with 8 M urea buffered with 50 mM Hepes/KOH pH 7.0.

Crosslinking

Crosslinking was performed in 25µl reactions containing 50 mM Hepes/KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, and 2.5 mM ATP in the presence of 27 µg/ml of SecY proteoliposomes, 40 µg/ml of SecA, and 1 µl of pOA:tRNA 19. The samples were incubated for 15 min at 37°C to form a translocation intermediate. For the indicated double-crosslinking experiments, the membranes were sedimented for 15 min at 14,000 rpm at 4°C. Crosslinking was performed with 50 μM Cu2+-phenanthroline for 10 min at 37°C, and the samples were treated with NEM and RNaseA and solubilized in 1% dodecylmaltoside (DDM). After centrifugation for 3 min at 14,000 rpm at room temperature, SDS sample buffer was added and the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 4-20% Tris-HCl gels (Bio-Rad). For immunoprecipitation, the DDM-solubilized samples were mixed with 20 µl of protein G-agarose beads pre-bound to SecY- or SecA- antibodies 6. Bound material was eluted in sample buffer.

Translocation assays

A proOmpA fragment, lacking both endogenous cysteines and an internal fragment encoding residues 175-296 but containing the natural stop codon, was synthesized in vitro. The substrate was precipitated by ammonium sulfate and dissolved in urea. Translocation assays of 50 μl contained 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 20 μg/ml SecA, 36 μg/ml SecY proteoliposomes, and 1 μl of pOA. For the experiments in the absence of ATP, 22 μg/ml hexokinase and 20 mM glucose were added. After incubation for different time periods at 37°C, the samples were incubated with 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K for 40 min on ice. The samples were treated with 2 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid before SDS-PAGE.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 | The effect of cysteine mutations in the two-helix finger of SecA on translocation. Residues in SecA’s two-helix finger were individually mutated to cysteines. The mutants were purified and tested for translocation activity by incubation for 15 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of ATP with in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled pOA and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex. After treatment with proteinase K, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. A cysteine-lacking SecA mutant served as positive control. Shown is the quantification of three experiments (mean and standard error of the mean). The data were normalized with respect to the Cys- mutant.

Table S2 | Amino acids that can substitute the critical tyrosine in SecA.

A BLAST search of all currently completed bacterial genomes was performed with Escherichia coli K12 SecA as the query. Alignments of the 748 results were used to identify substitutions of the tyrosine at position 794 of E. coli K12. Amino acids (in one letter code) are shown ranked by order of occurrence. Residues in italics are shown to give SecAs with low translocation activity (see main text, Fig. 1c).

Table S1 | Conservation of the tyrosine at the tip of the two-helix finger.

SecA proteins (COG0653) 1 from 50 diverse species representing 10 bacterial phyla (shown in bold) were aligned. SecA regions corresponding to residues 782-838 of Escherichia coli K12 are shown. Tyrosines are shown in red, other large hydrophobic residues are shown in blue.

Table S3 | Bacterial species with conventional and non-conventional SecAs.

All species listed possess a non-conventional SecA (SecA2) with a small or hydrophilic amino acid in place of tyrosine at the tip of the loop of the two-helix finger, as well as a conventional SecA (SecA1) with a tyrosine or methionine at this position. The SecA2 loci are characterized by the presence of known neighboring genes2,3, including SecY2, carbohydrate modification proteins, such as glycosyl transferases (gtfs), and accessory secretory proteins (asp1-3). The substrate for SecA2 is often a serine- or serine/threonine-rich protein, and its gene is also found in the locus. Accession numbers for SecA1 and SecA2 are shown.

Acknowledgements

We thank Byron DeLaBarre and Briana Burton for critical reading of the manuscript, and R. Sauer, T. Baker, and A. Horwich for discussion. The work was supported by an NIH grant. T.A.R. is a HHMI investigator. Y. N. was supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-#1953-07).

References

- 1.Rapoport TA. Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature. 2007;450:663–669. doi: 10.1038/nature06384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brundage L, Hendrick JP, Schiebel E, Driessen AJM, Wickner W. The purified E. coli integral membrane protein SecY/E Is sufficient for reconstitution of SecA-dependent precursor proteintranslocation. Cell. 1990;62:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90111-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmer J, Nam Y, Rapoport TA. Crystal structure of the protein-translocation complex formed by the SecY channel and the SecA ATPase. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07335. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Economou A, Wickner W. SecA promotes preprotein translocation by undergoing ATP-driven cycles of membrane insertion and deinsertion. Cell. 1994;78:835–843. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Berg B, et al. X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature. 2004;427:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon KS, Or E, Clemons WM, Jr., Shibata Y, Rapoport TA. Disulfide bridge formation between SecY and a translocating polypeptide localizes the translocation pore to the center of SecY. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:219–225. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris CR, Silhavy TJ. Mapping an interface of SecY (PrlA) and SecE (PrlG) by using synthetic phenotypes and in vivo cross-linking. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:3438–3444. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3438-3444.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam PC, Maillard AP, Chan KK, Duong F. Investigating the SecY plug movement at the SecYEG translocation channel. EMBO J. 2005;24:3380–3388. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt JF, et al. Nucleotide control of interdomain interactions in the conformational reaction cycle of SecA. Science. 2002;297:2018–2026. doi: 10.1126/science.1074424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarosik GP, Oliver DB. Isolation and Analysis of Dominant secA Mutations in Escherichia-Coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:860–868. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.860-868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karamanou S, et al. A molecular switch in SecA protein couples ATP hydrolysis to protein translocation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1133–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrontou E, Karamanou S, Baud C, Sianidis G, Economou A. Global co-ordination of protein translocation by the SecA IRA1 switch. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22490–22497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborne AR, Clemons WM, Jr., Rapoport TA. A large conformational change of the translocation ATPase SecA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10937–10942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401742101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bensing BA, Takamatsu D, Sullam PM. Determinants of the streptococcal surface glycoprotein GspB that facilitate export by the accessory Sec system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1468–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siboo IR, Chaffin DO, Rubens CE, Sullam PM. Characterization of the Accessory Sec System of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol . 2008 doi: 10.1128/JB.00300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matlack KES, Plath K, Rapoport TA. Protein transport by purified yeast Sec complex and Kar2p without membranes. Science. 1997;277:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.938. B., M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuyama S, Kimura E, Mizushima S. Complementation of two overlapping fragments of SecA, a protein translocation ATPase of Escherichia coli, allows ATP binding to its amino-terminal region. J Biol chem. 1990;265:8760–8765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Or E, Navon A, Rapoport T. Dissociation of the dimeric SecA ATPase during protein translocation across the bacterial membrane. EMBO J. 2002;21:4470–4479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborne AR, Rapoport TA. Protein translocation is mediated by oligomers of the SecY complex with one SecY copy forming the channel. Cell. 2007;129:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlandson KJ, Or E, Osborne AR, Rapoport TA. Analysis of polypeptide movement in the SecY channel during SecA-mediated protein translocation. J Biol Chem . 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710356200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, et al. Crystal structures of the HslVU peptidase-ATPase complex reveal an ATP-dependent proteolysis mechanism. Structure. 2001;9:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui SM, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Role of the processing pore of the ClpX AAA+ ATPase in the recognition and engagement of specific protein substrates. Genes Dev. 2004;18:369–374. doi: 10.1101/gad.1170304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinnerwisch J, Fenton WA, Furtak KJ, Farr GW, Horwich AL. Loops in the central channel of ClpA chaperone mediate protein binding, unfolding, and translocation. Cell. 2005;121:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLaBarre B, Christianson JC, Kopito RR, Brunger AT. Central pore residues mediate the p97/VCP activity required for ERAD. Mol Cell. 2006;22:451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Diverse pore loops of the AAA+ ClpX machine mediate unassisted and adaptor-dependent recognition of ssrA-tagged substrates. Mol Cell. 2008;29:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada-Inagawa T, Okuno T, Karata K, Yamanaka K, Ogura T. Conserved pore residues in the AAA protease FtsH are important for proteolysis and its coupling to ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50182–50187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park E, et al. Role of the GYVG pore motif of HslU ATPase in protein unfolding and translocation for degradation by HslV peptidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22892–22898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collinson I, et al. Projection structure and oligomeric properties of a bacterial core protein translocase. EMBO J. 2001;20:2462–2471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 | The effect of cysteine mutations in the two-helix finger of SecA on translocation. Residues in SecA’s two-helix finger were individually mutated to cysteines. The mutants were purified and tested for translocation activity by incubation for 15 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of ATP with in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled pOA and proteoliposomes containing purified SecY complex. After treatment with proteinase K, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. A cysteine-lacking SecA mutant served as positive control. Shown is the quantification of three experiments (mean and standard error of the mean). The data were normalized with respect to the Cys- mutant.

Table S2 | Amino acids that can substitute the critical tyrosine in SecA.

A BLAST search of all currently completed bacterial genomes was performed with Escherichia coli K12 SecA as the query. Alignments of the 748 results were used to identify substitutions of the tyrosine at position 794 of E. coli K12. Amino acids (in one letter code) are shown ranked by order of occurrence. Residues in italics are shown to give SecAs with low translocation activity (see main text, Fig. 1c).

Table S1 | Conservation of the tyrosine at the tip of the two-helix finger.

SecA proteins (COG0653) 1 from 50 diverse species representing 10 bacterial phyla (shown in bold) were aligned. SecA regions corresponding to residues 782-838 of Escherichia coli K12 are shown. Tyrosines are shown in red, other large hydrophobic residues are shown in blue.

Table S3 | Bacterial species with conventional and non-conventional SecAs.

All species listed possess a non-conventional SecA (SecA2) with a small or hydrophilic amino acid in place of tyrosine at the tip of the loop of the two-helix finger, as well as a conventional SecA (SecA1) with a tyrosine or methionine at this position. The SecA2 loci are characterized by the presence of known neighboring genes2,3, including SecY2, carbohydrate modification proteins, such as glycosyl transferases (gtfs), and accessory secretory proteins (asp1-3). The substrate for SecA2 is often a serine- or serine/threonine-rich protein, and its gene is also found in the locus. Accession numbers for SecA1 and SecA2 are shown.