Abstract

Exposure to toxicants leads to cumulative molecular changes that overtime increase a subject’s risk of developing urothelial carcinoma (UC). To assess the impact of arsenic exposure at a time progressive manner, we developed and characterized a cell culture model and tested a panel of miRNAs in urine samples from arsenic exposed subjects, UC patients and controls. To prepare an in vitro model, we chronically exposed an immortalized normal human bladder cell line (HUC1) to arsenic. Growth of the HUC1 cells was increased in a time dependent manner after arsenic treatment and cellular morphology was changed. In soft agar assay, colonies were observed only in arsenic treated cells and the number of colonies gradually increased with longer periods of treatment. Similarly, invaded cells in invasion assay were observed only in arsenic treated cells. Withdrawal of arsenic treatment for 2.5 months did not reverse the tumorigenic properties of arsenic treated cells. Western blot analysis demonstrated decreased PTEN and increased AKT and mTOR in arsenic treated HUC1 cells. Levels of miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c were down-regulated in arsenic exposed HUC1 cells by quantitative RT-PCR. Furthermore, in human urine, miR-200c and miR-205 were inversely associated with arsenic exposure (P=0.005 and 0.009, respectively). Expression of miR-205 discriminated cancer cases from controls with high sensitivity and specificity (AUC=0.845). Our study suggests that exposure to arsenic rapidly induces a multifaceted dedifferentiation program and miR-205 has potential to be used as a marker of arsenic exposure as well as a maker of early UC detection.

Keywords: Urothelial cancer, Urine, Biomarkers, Arsenic exposure

Introduction

Arsenic-induced carcinogenesis emerged as an international environmental health issue in the late 1960s when arsenic contaminated drinking water was found to cause cancer. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated the pleiotropic nature of arsenic toxicity in humans at exposure levels that are relevant to environmental health hazards frequently experienced by human populations throughout the world (1). Previous studies suggest that arsenic causes the promotion and progression of several diseases, including cancer and non-cancer illnesses (2–5). Additionally, individual genetic variation, nutrition factors and other environmental factors (such as smoking) appear to contribute to the severity of toxicities induced by arsenic (2).

Based on epidemiologic evidence from southwestern Taiwan, arsenic in drinking water was associated with the development of multiple cancers, including urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the bladder, in a dose-dependent manner (6). Recent studies from both Chile and northeastern Taiwan provide further support for the association between arsenic exposure in drinking supplies and increased incidence of cancers (7). As urine excretion is the primary route for arsenic elimination, the bladder epithelium may thus be exposed to higher concentrations of arsenic due to the bioconcentration of urine by the kidneys. In addition to inorganic arsenic (arsenite and arsenate), the human bladder is exposed to mono and di-methylated arsenic metabolites systematically or urinary filtrate. Accumulated evidence, therefore, suggests that the bladder epithelium may be one of the primary targets of arsenic induced carcinogenesis.

The etiology of urothelial carcinoma (UC) is not fully understood at this time. Large scale epidemiological studies have found no association between UC incidence within first degree relatives and have therefore argued strongly against a germline genetic mechanism (8). On the other hand, several environmental risk factors such as tobacco-related carcinogens, arsenic, aromatic amines, polycyclic aromatic or halogenated hydrocarbons and ionizing radiation have been linked to UC incidence (9). Recently, arsenic exposure to humans has become a significant public health concern. Consequently, in-depth study is needed to make public health policy decisions and to identify underlying pathogenic molecular events related to arsenic induced carcinogenesis. Although there is extensive epidemiologic evidence of increased risk for the development of UC associated with arsenic exposure (10), the mechanisms by which arsenic participates in tumorigenesis are not well understood. To gain mechanistic insights, in vitro and in vivo models can be used. Arsenic-induced cancer animal models have been difficult to develop due to significant species-specific differences in arsenic metabolism. Thus suitable in vitro human-originated models that replicate arsenic exposure in humans are needed in order to investigate arsenic carcinogenesis (10). In vitro models of human origin need to be extensively characterized and tested to ensure adequate representation of the effects seen in humans chronically exposed to arsenic. Although the lack of a fully differentiated urothelium presents a limitation, an in vitro system provides an easily handled model to work suitable for identification of progressive genetic and epigenetic changes. Here we report the establishment of an arsenic exposed in vitro UC carcinogenesis model. We further characterize critical cell signaling pathways (such as NOTCH pathway, PI3K–AKT pathway) and miRNAs related to epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). Understanding these biological effects of arsenic at the molecular level will facilitate the identification of appropriate non-invasive markers of arsenic exposure and assess promising drugs for prevention and therapeutic strategies for UC.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Normal human urothelial cell line HUC1 [Simian Virus 40 (SV40) Immortalized Normal Human Urinary Tract Epithelial Cells] was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HUC1 cells were cultured in F12K medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) and 1% Penicillin-streptomycin solution (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) under a 5 % CO2 atmosphere at 95% relative humidity. As2O3 (Arsenic trioxide), DMSO was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Qiazol reagent for RNA extraction was purchased from Qiagen. BFTC 905 and BFTC 909 cell lines which were established from arsenic exposed UC subjects (11) were cultured in Dulbecco’s MEM medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) and 1% Penicillin-streptomycin solution (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA). All the cell lines were authenticated.

Arsenic Treatment

To prepare in vitro model, we chronically exposed HUC1 to arsenic. Briefly HUC1 cells were exposed to varying concentrations of AS2O3 to determine the lethal concentration in 50% of the cells (LC50) over 72 hrs. The LC50 for AS2O3 in HUC1 cells was determined to be 1 µM. Thus, 1 µM was selected for chronic testing, which was non-toxic to cells. HUC1 cells were cultured in a 25cm flask in F12K complete medium with or without 1µM AS2O3. Medium and arsenic was changed every two days. Cells were sub-cultured as necessary and frozen down each month for future studies. To determine the arsenic withdrawal effect, we cultured the 8 months and 10 months arsenic treated HUC1 cells without arsenic for 2.5 months and performed MTT, soft agar and invasion assay.

Cellular Viability Assay (MTT Assay)

We performed MTT assay at 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 months of arsenic treated and mock treated cells. Cell proliferation was measured by the 3-(4, 5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) proliferation assay kit from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously (12, 13).

Immunoblotting Analysis

UC tumors comprise a heterogeneous group with respect to both histopathology and clinical behavior. Alterations of different molecular pathways have been proposed and the MAPK/PI3K/AKT pathway has been reported to play a principal role in UC carcinogenesis (14). Deregulation of genes included in this pathway has been reported in both non-muscle invasive and muscle invasive UC; and we recently reported that several PI3K–AKT pathway genes have been altered in HUC1 cells after exposure to cigarette smokes (CS) (12). As arsenic is a constituent of CS, we tested the expression of PI3K–AKT pathway genes (PI3K, AKT and mTOR) in our arsenic treated and untreated cell lines. Briefly, arsenic-treated and untreated (6,8,10 months) cells were lysed on ice for 30 min in RIPA (radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer) buffer [150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, and 10 mM NaF], supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was harvested as the total cellular protein extract. The protein concentration was determined using Lowry protein assay (Bio-rad Laboratories, California, USA). Equal amounts of protein (40 µg each) were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1 M DTT and 0.01% bromophenol blue), run on 4–12% NuPAGE and electroblotted onto Nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-rad Laboratories). The membrane was blocked with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk or 5% BSA (bovine serum albumin) for 1 h at room temperature, and probed with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated appropriate secondary antibody for 1h at room temperature followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). All the immunoblotting experiments were performed at least 2 times. Antibodies for p16, phosphor and total ERK1/2, phosphor and total EGFR, phosphor and total PI3K, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) (at 1:500 dilution), and β-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (at 1:5000 dilution). Total and phosphor (S473) AKT, mTOR, Cyclin D3, E-cadherin, Vimentin and others were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) and used at 1:1000 dilution). Densitometry analysis was performed by GS-800 Calibrated Densitometer (Bio-rad laboratories).

Soft Agar Assay

Soft agar plates were made with Agar Select (Invitrogen, NY, USA) at 0.8% (bottom layer) and 0.3% (top layer). Five thousand arsenic treated and untreated cells [6 months (M), 8M, and 10M, 8M treated and 2.5M arsenic withdrawal, 10M treated and 2.5M arsenic withdrawal] were counted and seeded in the top layer of agar mixed with F12K medium supplement with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution in 6-well plates and incubated in 37°C. Complete medium was added every 2 days (500 µL/well). The cells were allowed to grow for two weeks and colonies were photographed and counted using a light microscope. Each experiment was performed in triplicate wells and repeated three times.

Invasion Assay

Invasion assay was performed using individual inserts coated with Matrigel (catalogue #354480,BD Biosciences, California, USA) as directed by manufacturer. Briefly, 1×104 arsenic treated and untreated (6M, 8M and 10M, 8M treated and 2.5M arsenic withdrawal, 10M treated and 2.5M arsenic withdrawal) cells were plated in triplicates in serum free media. Cells were allowed to attach and grow for 48 hrs. Invaded cells were fixed using 100% methanol and stained with hematooxylin and eosin (H&E). Invaded cells were counted under a microscope in 10 randomly selected fields (magnification x100) per well and averaged. To normalize for cell invasion differences, each cell line was also grown on an uncoated insert. Number of invaded cells was divided by the number of cell counted on the uncoated inserts.

DNA Extraction

Total genomic DNA was extracted by digestion with 50 µg/ml proteinase K (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) in the presence of 1% SDS at 48°C overnight, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Genomic DNA was eluted in low-salt Tris-EDTA (LoTE) buffer and stored at −20°C.

RNA and miRNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted after cell lysis with Qiazol (Qiagen, Germany) followed by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Total RNA was eluted in DEPC treated water and stored at −80°C. Micro RNA (miRNA) extraction was performed using the MirVana miRNA Isolation Kit, (Ambion, Cat # AM 1560) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Real Time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for Quantification of miRNAs

Total RNA (20 ng), isolated from cells was reverse transcribed using TaqMan reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and RNA-specific primers provided with TaqMan microRNA assays (Applied Biosystems) in 15 µL reaction volume that contains 3µL of RT Primer Mix, 0.15 µL of 100mM dNTPs, 1µL of Reverse Transcriptase enzyme 50U/µL, 0.19 µL of RNase inhibitor 20 U/µL, 4.16 µL of Nuclease Free water and 5µL of RNA (20ng). Reverse transcription (RT) reaction was carried out with annealing at 16°C for 30 min followed by extension at 42°C for 30 min. 1.5 µL of the RT reaction was then used with 1 µL specific primers for each of the miR-222, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c and miR-205 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in triplicate wells for 40-cycle PCR on a 7900HT thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10min, followed by a third step for denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C was for 1 min repeated for 40 cycles. SDS software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to determine cycle threshold (Ct) values of the fluorescence measured during PCR. Results of miRNA were normalized to miR-222 relative expression using the ΔCt method and then the tested miRNAs in the arsenic treated periods were normalized using the ΔΔCt method to the expression levels of their untreated matching period. Selection of endogenous control miRNA for normalization is not yet established. Most prior reports used RNAU6 (RNU6B) and RNU48 for normalization. However, neither of these was expressed in all the urine supernatants and the expression levels were variable. We tested three miRNA (RUN6B, mir-222 and miR-16) in a subset of our urine supernatants from controls and cancer cases. Among these three molecules, miR-222 was found to be almost equally expressed in all the samples tested (data not shown). Therefore we used miR-222 for normalization.

Methylation profiling of arsenic treated and untreated HUC1 cells by NOTCH Signaling Pathway DNA Methylation PCR Array

Due to the growing interest of NOTCH signaling pathway in human carcinogenesis and reports of epigenetic alterations related to environmental exposure, we performed Notch Signaling Pathway DNA Methylation PCR Array analyses utilizing the EpiTect Methyl II PCR System (SABiosciences, Cat # EAHS-611ZE). The Human Notch Signaling Pathway EpiTect Methyl II Signature PCR Array (SABiosciences, Cat # EAHS-611Z) profiles the promoter methylation status of a panel of 22 genes central to NOTCH signal transduction. The spreadsheets, gene tables and template formulas included with the PCR array package were used to calculate relative changes in promoter methylation status of each of the gene. The method employed by the EpiTect Methyl II PCR System (SABiosciences) is based on detection of remaining input DNA after cleavage with a methylation-sensitive and/or a methylation-dependent restriction enzyme (15). These enzymes will digest unmethylated and methylated DNA, respectively. Following digestion, the remaining DNA in each individual enzyme reaction is quantified by real-time PCR using primers that flank a promoter (gene) region of interest. The relative fractions of methylated and unmethylated DNA are subsequently determined by comparing the amount in each digest with that of a mock (no enzymes added) digest using a ΔCT method. Briefly, 0.4µg of DNA after digestion with Mo, Ms, Md, and Msd enzymes were placed in each well of a 384-well PCR array plate (SABiosciences,, Cat # EAHS-611ZE) that contained a panel of primer sets for a thoroughly researched set of 22 Notch pathway genes, plus 2 positive/negative controls to determine assay performance. The methylation PCR reaction was performed in Applied Biosystem 7900HT sequence detector with 10 µL total volume. The amplification conditions were the following: 10 min at 95 °C, a 3 cycle step at 99 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min and a 40 cycle step at 97 °C for 15 s and 72°C for 1 min. The relative quantity of methylated and unmethylated DNA in each sample in the PCR array was calculated using the following formula as instructed by the manufacturer:

Quantitative Methylation Specific PCR (QMSP) for Selected Genes

Representative candidate genes (NFKB2 and NCSTN) with significant promoter methylation changes identified by NOTCH Signaling Pathway DNA Methylation PCR Array were chosen for technical validation by QMSP analysis. DNA was bisulfite treated (Epitect Kit, Qiagen) and analyzed with QMSP. Fluorogenic PCR reactions were carried out in a reaction volume of 20 µL consisting of 600 nmol/L of each primer; 200 µmol/L probe; 0.75 units platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen); 200 µmol/L of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 200 nmol/L ROX dye reference (Invitrogen); 16.6 mmol/L ammonium sulfate; 67 mmol/L Trizma (Sigma-Aldrich); 6.7 mmol/L magnesium chloride; 10 mmol/L mercaptoethanol; and 0.1% DMSO. Triplicates of three microliters (3 µL) of bisulfite-modified DNA solution were used in each QMSP amplification reaction. Primers and probes were designed to specifically amplify the promoters of the two genes of interest and the promoter of a reference gene, β-actin (ACTB). Primer and probe sequences and annealing temperatures are provided in Supplementary Table 1A.

cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

In order to validate the expression of differentially methylated genes due to arsenic exposure as identified by NOTCH Methylation Array, we performed RT-PCR using commercially available TaqMan Expression assays (Life Technologies). 1 µg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction is catalyzed by SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (RT). This enzyme has been engineered to reduce the RNase H activity that degrades mRNA during the first-strand reaction, resulting in a greater full-length cDNA synthesis and higher yields of first-strand cDNA than obtained with RNase H+ RTs. 40 ng of cDNA was used as a template in PCR reaction that contain 1 µL of each of the forward and reverse primer of the genes of interest (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in triplicate wells for 40-cycle PCR on a 7900HT thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by a third step for denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. SDS software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to determine cycle threshold (Ct) values of the fluorescence measured during PCR. Expression level of gene of interest was normalized with GAPDH using the ΔCt method. RT-PCR assay information for CTBP1, ERBB2, NCSTN, NFKB2 and GAPDH were provided in Supplementary Table 1B.

Sample sources

To determine the consequences of arsenic exposure on miRNA associated with Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), we utilized a human miRNA panel to test 110 urine samples from subjects who were exposed to different levels of arsenic. To confirm the arsenic exposure specific miRNA alterations, we also tested 67 urine samples collected from the Baltimore area with safe levels of arsenic utilizing the same miRNA panel. Control patients were randomly chosen from the Johns Hopkins Urology patients with no history of genitourinary malignancy and whose urine samples were evaluated by the Cytopathology Division of the department of pathology. Approval for research on human subjects was obtained from The Johns Hopkins University institutional review boards. This study qualified for exemption under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services policy for protection of human subjects [45 CFR 46.101(b)]. A summary of arsenic exposed and non-exposed sample information is detailed in Table 1A. To assess a potential causative relationship between the four uniquely identified arsenic exposure related miRNA alterations, we quantitatively measured concentrations of each of the four candidate miRNAs in urine samples from 32 UC cases. Detailed information of UC cases are shown in Table 1B. Urine samples from subjects with low and high exposure to environmental arsenic were identified through the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study (HEALS) cohort, an ongoing population-based prospective cohort study in Araihazar, Bangladesh (16). Arsenic levels in drinking water in Araihazar range from 0.1 µg/L to >100 µg/L. The cohort includes about 42,000 members, of whom 50% are exposed to arsenic >10 µg/L and 25% are exposed to >50 µg/L and approximately 10–12% >100 µg/L. Arsenic exposure status of subjects was determined through drinking water arsenic concentrations measured in the subject’s primary tube-well used for water consumption. Arsenic concentrations in drinking water >10 µg/L were considered exposed and concentrations <10 µg/L were considered as unexposed. This cohort has been extensively used in previous epidemiologic studies on arsenic determinants and health effects in Bangladesh (16–22). Within all studies, extensive clinicopathological information including smoking history was recorded.

Table 1.

Characteristics of human urine samples tested for miRNA expression

| A. Arsenic exposed and unexposed normal urine samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Arsenic Exposed (n=110) |

Arsenic unexposed | ||

| Smokers (n=11) | Non-smokers (n=46) | Total (n=67*) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 36.8 | 59.4 | 68.2 | 66.5 |

| Range | 20–65 | 50–73 | 39–94 | 39–94 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 54 | 8 | 37 | 45 |

| Female | 56 | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Never | Not available | N/A | N/A | 46 |

| 0–20pack years | Not available | 5 | N/A | 5 |

| >20–35 pack years | Not available | 1 | N/A | 1 |

| >35 pack years | Not available | 5 | N/A | 5 |

| Unknown | Not available | N/A | N/A | 10 |

| Water arsenic, µg/L | ||||

| <10 | 28 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 10–50 | 22 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| >50 | 21 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Unknown | 39 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Creatinine adjusted urine arsenic, µg/g | ||||

| <100 | 35 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 100–200 | 38 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| >200 | 37 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| B. UC and Arsenic unexposed normal urine samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Cancer (n=32) |

Arsenic unexposed | ||

| Smokers (n=11) | Non-smokers (n=46) | Total (n=67*) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 65.4 | 59.4 | 68.2 | 66.5 |

| Range | 36–84 | 50–73 | 39–94 | 39–94 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 26 | 8 | 37 | 45 |

| Female | 6 | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Stage | ||||

| CIS | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| pTa | 16 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| T1 | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ≥pT2 | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Included 10 unexposed samples with unknown smoking history, N/A: not applicable

Urine analysis for miRNA expression

1–2 ml of randomly collected urine sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 rpm and the supernatant was used for miRNA extraction. Detailed rationales are provided in the discussion section for considering supernatant for miRNA extraction. miRNA extraction was performed using the MirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Cat # AM1560) according to manufacturer’s instructions. To remove any associated debris and nucleoprotein, the supernatant sample is first lysed in a denaturing lysis solution which stabilizes RNA and inactivates RNases. The lysate is then extracted once with Acid-Phenol: Chloroform which removes most of the other cellular components, leaving a semi-pure RNA sample. By using this kit we obtained approximately 400 ng of total RNA. A total of 20 ng RNA was reverse transcribed using TaqMan reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and RNA-specific primers provided with TaqMan microRNA assays (Applied Biosystems) in 15 µL reaction volume containing 3µL of reverse-transcriptase (RT) Primer Mix, 0.15 µL of 100mM dNTPs, 1µL of RT enzyme 50U/µL, 0.19 µL of RNase inhibitor 20 U/µL, 4.16 µL of Nuclease Free water and 5µL of RNA (20ng) RT reaction was carried out with annealing at 16°C for 30 min followed by extension at 42°C for 30 min. PCR reaction was then carried out for specific miRNA in a total volume of 20 µL that contain 2µL of the RT reaction, 10 µL of TaqMan Universal Master Mix, 7µL water and 1 µL of specific primers for each of the miR-16, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c and miR-205 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in triplicate wells for 40-cycle PCR on a 7900HT thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10min, followed by a third step for denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C was for 1 min repeated for 40 cycles. SDS software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to determine cycle threshold (Ct) values of the fluorescence measured during PCR. Each of the miRNA of interest was normalized to miR-222 using the ΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

The data represent mean ± SD from independent experiments done for 3 to 5 times. Continuous variables were basically analyzed by student’s t-test, two-tailed. As for micro RNA expression analysis in urine samples, Mann-Whitney U test was applied to continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of HUC1 cells after chronic arsenic exposure

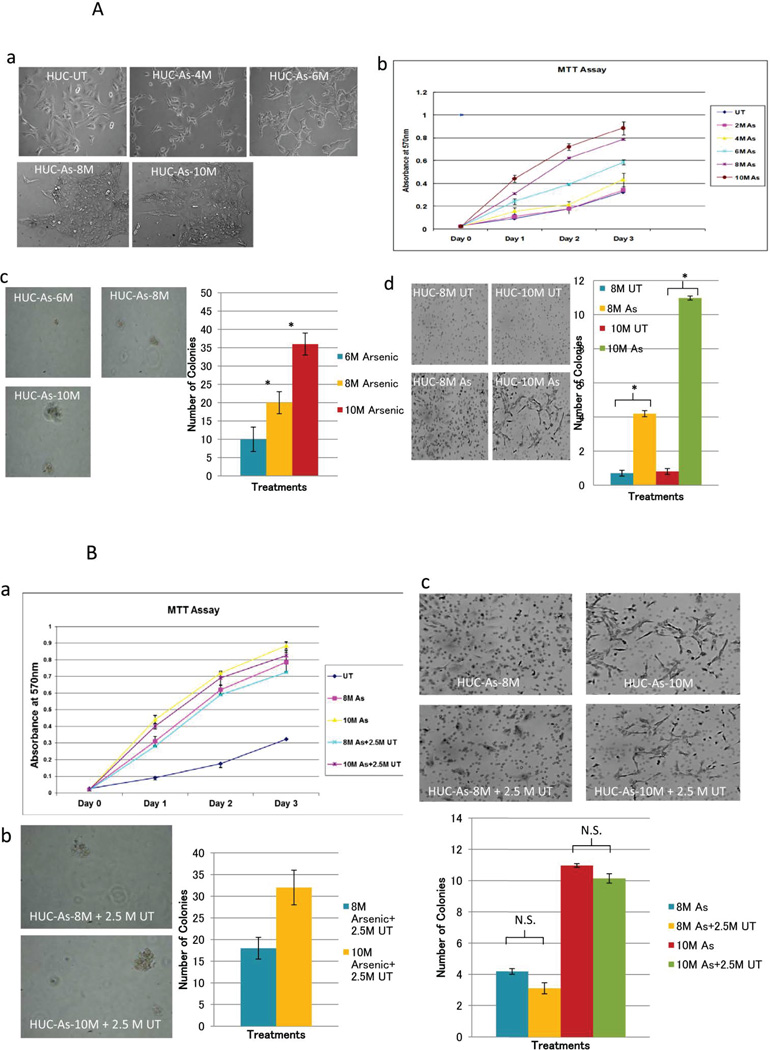

The morphological changes of cells due to chronic arsenic treatment are shown in Fig 1A a. We found that the growth of the HUC1 cells was increased in a time dependent manner after arsenic treatment (Fig 1A b). To determine whether the increased number of cells is due to cell proliferation, we performed BrdU assay using arsenic untreated and treated cell lines at various time points. We found that the increased cell numbers in arsenic treated cells was partially related to increased cellular proliferation (data not shown). Additionally, transformation analyses including soft agar and invasion assays showed that arsenic increases both size and number of colonies on soft agar, and also increases the number of invasive cells (Fig 1A, c,d; P<0.05 in all 8 and 10 months arsenic-treated cells in comparison with untreated cells; Student t test). Upon withdrawal of arsenic for 2.5 months in 8- and 10-month treated HUC1 cells, no changes in morphology and tumorigenic properties of the cells were observed (Figure 1B a, b and c). In conclusion, the observed inducible and irreversible phenotypic characteristic of HUC1 cells after arsenic treatment defines a suitable in vitro model for studying the effect of arsenic exposure on the molecular alterations in UC.

Figure 1.

A Transformation of HUC1 cells with long term arsenic exposure: a) Morphogical Changes-Morphology differences were monitored over the entire treatment schedule, using a light microscope (20X). Mock treated cells and arsenic treated cells were plated on 6cm dishes at a density of 200,000 per plate. At 6 months, arsenic treated HUC1 started to become more rounded and had a tendency to pile on to one another. b) MTT assay: MTT assay was performed for each month of treatment in order to determine if changes in cell proliferation occurred because of arsenic treatment. This figure depicts 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 months of treated and mock treated cells for simplicity reasons. Mean and standard deviation were calculated using sample replicate values. c) Soft Agar Assay: Anchorage independent growth was evaluated using soft agar assay. Cell were embedded in agar in triplicates and allowed to grow for 3 weeks. Cell colonies were counted using a light microscope in 4 different fields and averaged. Cell colonies were then stained with 0.05% ethidium bromide for 24 hrs. UV transilluminator was used to determine the number of colonies per well greater than 50µm in size. Left panels show colonies in arsenic treated cells. No colony was observed in arsenic untreated cells (picture not shown). Pictures were taken at random using a digital camera attached to a high resolution light microscope; Right side shows bar graphs of colonies in different time periods. Statistical differences between 6, 8 and 10 months treated samples and untreated samples were calculated using Student’s t-test. (* indicates P<0.05). d) Invasion assay: Left side shows invaded cells after arsenic treatment for 8 and 10 months. Right side shows graphical representation for the invasion assays performed at 8 and 10 months (UT=untreated, M=month). Invaded cells were counted using a light microscope at 10 different fields and a 20X objective. Pictures were taken at random. The number of colonies was significantly increased in arsenic treated samples (* indicates P<0.05, student t-test). B: Phenotypic observation after withdrawal of arsenic for 2.5M from 8M and 10M arsenic treated HUC1 cells. a) As determined by MTT assay, no significant difference of cell viability was observed in 8M and 10M arsenic treated and 2.5 M untreated cells. b) While no colony was observed in arsenic untreated HUC cells, 8M and 10M arsenic treated HUC1 cells retained the properties of anchorage-independent growth even after 2.5M untreated period; c) Similarly 8M and 10M arsenic treated HUC1 cells maintained invasive properties even after culturing these cell for 2.5M without As. N.S.: not significant, As: arsenic

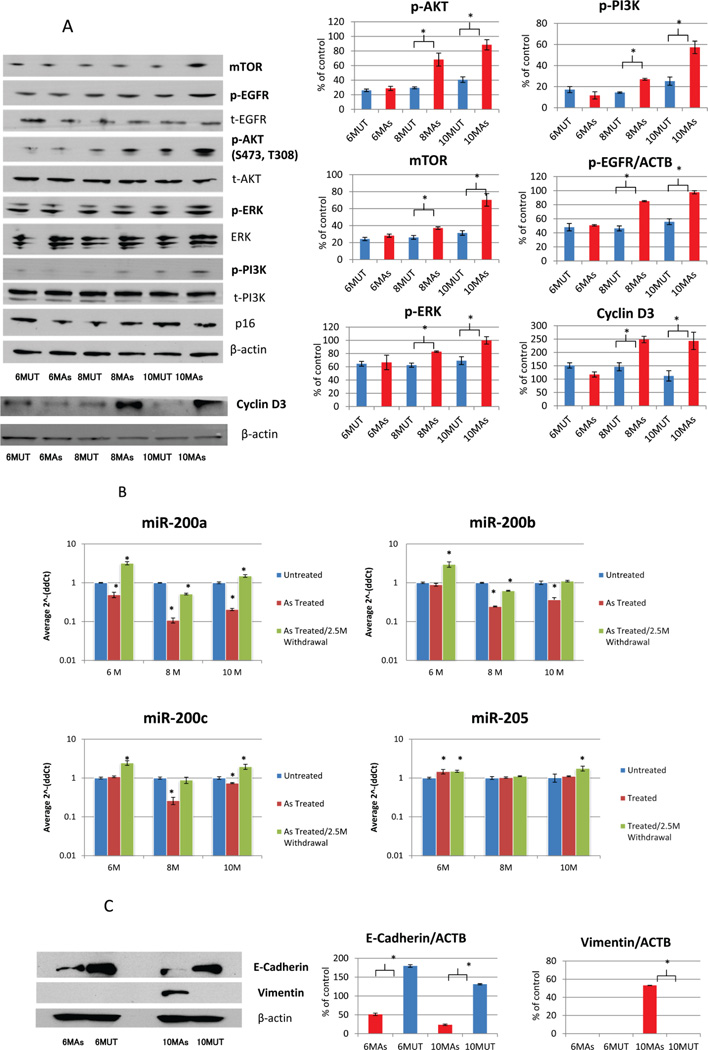

Alteration of expression of some key molecules including PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathway by arsenic exposure

As shown in Figure 2A, p-AKT was highly expressed in the arsenic treated cells compared to the untreated ones. Similarly, m-TOR and p-PI3K demonstrate dramatically increased expression in arsenic treated cells, specifically after 8 and 10 months. To further characterize our arsenic treated HUC1 cells, we performed western blot analysis for several other proteins that are known to be altered in oncogenic process. As has been seen in carcinogenesis studies in other malignancies (23, 24), p-EGFR, ERK and cyclin D3 expression were increased in arsenic treated cells in comparison with arsenic untreated cells. In summary, in addition to the morphological and other phenotypic alterations as shown in Figure 1A, this cell model was also altered at molecular level due to chronic arsenic exposure.

Figure 2.

A: Western Blot analysis of AKT pathway and EMT related proteins. Bar graphs showed the results of densitomatric analysis (mean ± standard deviation) (* indicates P<0.05, student t-test). Phosphorylated and total protein for EGFR, AKT, ERK, PI3K were increased in arsenic treated HUC1 cells. CyclinD3 and mTOR were also increased in arsenic treated HUC1 cells. The molecules that showed significant alterations due to arsenic treatment were bolded. As: arsenic; B: Expression levels of miR-200 family in arsenic exposed HUC1 cell culture model. HUC1 cell line was cultured in the presence of 1µM As2O3 for 6, 8 and 10 months. In order to study the reversibility of the arsenic exposal effect to the cells, we withdraw the drug for 2.5 months. Using the 2^−ΔΔCT method, the data are presented as the fold change in each miRNA expression normalized to mir-222 and relative to the untreated control (HUC1 cell line cultured in the presence of PBS for the same time course). Statistical difference between arsenic treated and untreated cells were calculated using Student’s t-test. * indicates P<0.05. C: Western blot analysis of two EMT associated protein: E-cadherin and Vimentin expression were analyzed using arsenic treated and untreated HUC1 cells for 6 months and 10 months. E-cadherin was significantly decreased in Arsenic treated cells of both 6 and 10 months (P<0.001 for both 6 and 10 months, Student’s t-test); No changes of expression was observed for Vimentin at 6 months arsenic treated cells, however, Vimentin expression dramatically increased at 10 months Arsenic treated cells (P<0.001, Student’s t-test).

Exposure of HUC1 cells to arsenic affects the expression of miRNAs associated with EMT and tumorigenesis

We observed morphologic differences between the arsenic treated and untreated HUC1 cell line using a light microscope. The round shape of the arsenic treated HUC1 cells changed to a spindle form, suggesting that EMT-like changes might have occurred (Figure 1A a). To confirm the induction of EMT in arsenic treated HUC1 cells, we analyzed the expression of the miRNAs regulating EMT (miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c and miR-205). At the molecular level, we generally observed significantly reduced expression of miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c in the arsenic treated HUC1 cell line (Figure 2B) (P<0.05, student’s t-test) in comparison with arsenic untreated cell line. However, no change or slight overexpression was observed for miR-205 after arsenic treatment. Interestingly, withdrawal of arsenic from media for 2.5 months resulted in expression recovery of the dysregulated miRNAs (miR-200a, miR200b and miR-200c) (Figure 2B) (P<0.05, student’s t-test). However, no reversal of cells morphology was observed (data not shown). In order to confirm EMT association, E-cadherin and vimentin protein expression were analyzed using Arsenic treated/untreated HUC1 cells for 6 months and 10 months. E-cadherin was significantly decreased in Arsenic treated cells of both 6 and 10 months while Vimentin expression appeared in 10 months Arsenic treated cells (Figure 2C).

Identification of differentially methylated genes using Human Notch Signaling Pathway DNA Methylation PCR Array

By array analysis, we found general reduction of promoter methylation of 2 genes (CTBP1 and NCSTN) and induction of promoter methylation of 2 genes (ERBB2 and NFKB2) in arsenic treated HUC1 cells (Supplementary Table 2). No significant promoter methylation changes were observed in 17 genes, and 1 gene was failed in the analysis. Technical validation of promoter methylation was performed for two representative genes (NFKB2 and NCSTN) by QMSP assay (Supplementary Figure 1 A and B). From the viewpoint of dichotomization (methylation positive or negative), only 2 samples (8MAs/2.5MUT and 10MAs) for NKFB2, and 1 sample (BFTC909) for NCSTN showed different results. So the consistency between array and QMSP based assay for NFkB2 and NCSTN were 78% and 89% respectively. These discrepancies may be due to different sensitivity of the assay. Overall QMSP results were generally consistent with beta-values obtained from Notch methylation array data.

Promoter methylation of differentially methylated genes determined by Notch methylation array in arsenic treated and untreated HUC1 cells are inversely associated with expression

To determine whether changes in promoter methylation due to arsenic exposure had any effect on gene expression, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (Q-RT-PCR) for all the 4 differentially methylated genes (CTBP1, NCSTN, ERBB2 and NFKB2) in arsenic treated and untreated HUC1 cells. Q-RT-PCR showed increase of the expression levels of CTBP1 and NCSTN genes in arsenic treated HUC1 cells, which was an expected observation of the demethylated pattern in arsenic treated HUC1 cells (Supplementary Figure 2A). On the contrary, NFKB2 was found to be methylated in arsenic treated HUC1 cells and exhibited lower expression levels compared to the untreated HUC1 cell line (Supplementary Figure 2B). As for ERBB2 gene, 8 months As treated cells showed relatively high expression, although promoter methylation was detected. It may be due to incomplete occupation of the methylated promoter region by other associated molecules for silencing of this gene. For further confirmation of association of ERRB2 promoter methylation with expression, we tested promoter methylation of ERBB2 in BFCT 905 and BFCT 909 cell lines. These cell lines were established from arsenic exposed bladder cancer patients. As expected, we observed promoter methylation of ERBB2 in these two cell lines, and very low expression of ERBB2 were detected in these two cell lines. In general, promoter methylations of these genes seemed to be inversely associated with gene expression. However, these findings need to be confirmed in future studies.

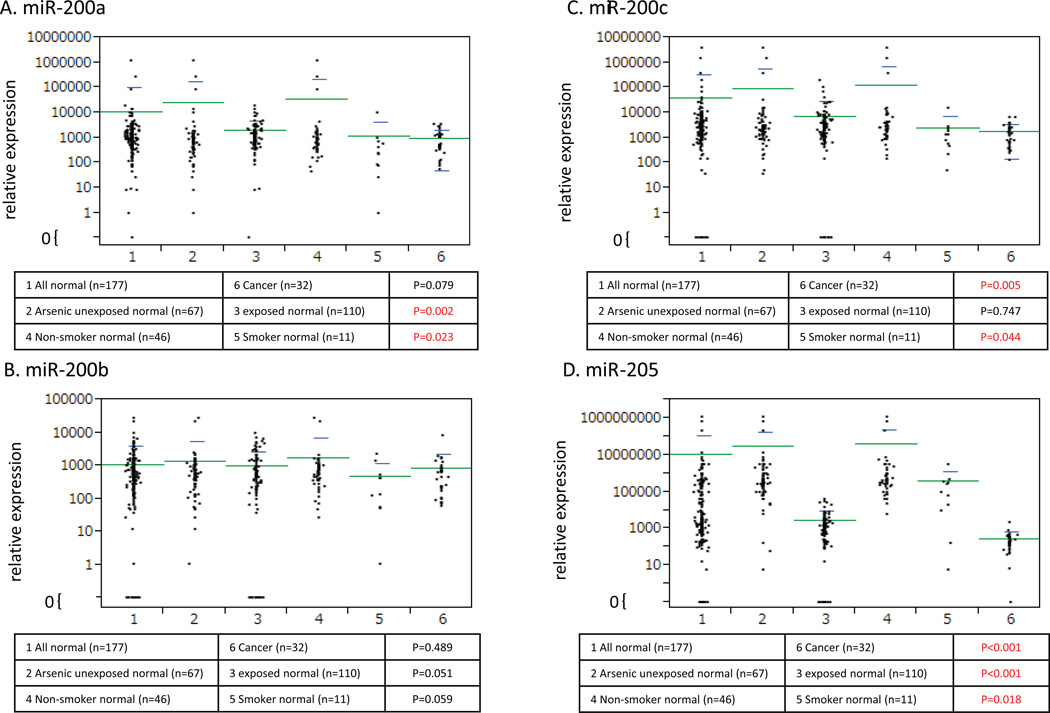

miRNAs in urine from arsenic exposed population and controls

In general, low levels of urine miRNA expression were observed in the arsenic exposed population for all four miRNA (miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c and miR-205) tested (Figure 3, A, B, C and D). Interestingly, expression of miR-205 was significantly decreased in the arsenic exposed population (P<0.001, Mann–Whitney U test) (Figure 3 D). Furthermore, we also analyzed miRNA expression patterns according to different levels of water arsenic concentration (Supplementary Figure 3 a, b and c) and creatinine adjusted urine arsenic concentration (Supplementary Figure 3 d, e and f). Although not conclusive, our data showed that increased levels of arsenic exposure were associated with low levels of miR-200c (P=0.005 between creatinine adjusted urine arsenic <100 µg/g and >200 µg/g, Mann–Whitney U test) and miR-205 (P=0.009 between creatinine adjusted urine arsenic <100 µg/g and >200 µg/g, Mann–Whitney U test).

Figure 3.

Average 2^−ΔCt of each micro RNA expression (A: miR-200a, B: miR-200b, C: miR-200c, D: miR-205) in urine sample was calculated and plotted after normalization with miR-222. Six groups of samples were listed. All normal urines (1: n=177) were compared with cancer urines (6: n=32). As subgroup analyses in normal urines, arsenic unexposed normal urines (2: n=67) were compared with arsenic exposed urines (3: n=110), and non-smoker normal urines (4: n=46) were compared with smoker normal urines (5: n=11). Mann–Whitney U test was performed and a P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. As for normal versus cancer, miR-200c and 205 expression were significantly down-regulated in cancer (P=0.005 and P<0.001, respectively). As for arsenic unexposed versus exposed, miR-200a and miR-205 were significantly down-regulated in cancer (P=0.002 and P<0.001, respectively). As for non-smoker versus smoker, miR-200c and 205 expression were significantly down-regulated in cancer (P=0.044 and P<0.018, respectively). Notably, the expression of miR-205 was consistently down-regulated in arsenic exposed, smoker and cancer urines.

Validation of miRNA candidates in the urine of UCC patients and controls

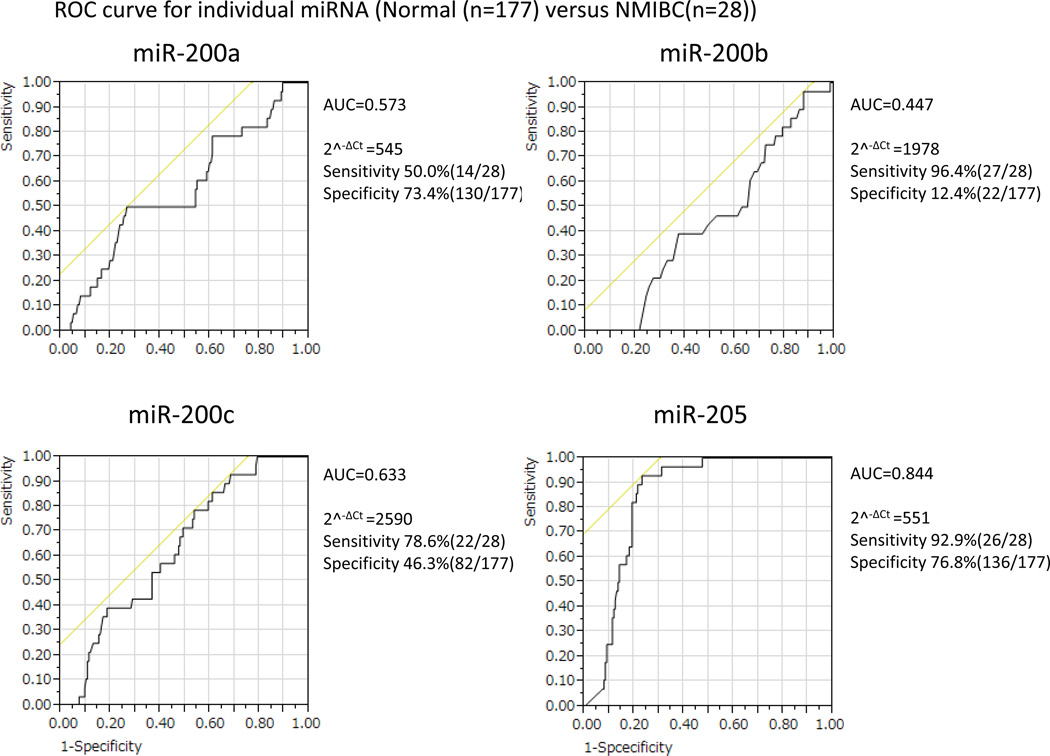

To determine the relationship of altered miRNA due to arsenic exposure and cancer, we subsequently tested all four miRNAs in urine samples from 32 UC patients and compared the expression levels with the urine miRNA level from 177 people without cancer. Among 177 people, we also compared 67 arsenic unexposed people and 110 exposed people. Besides, we compared 46 non-smokers with 11 smokers in 67 arsenic unexposed people. Scatter plots in Figure 3 showed the distribution of expression levels of all the four miRNA in urine of cancer cases in different comparison groups. The diagnostic potential of urine miRNAs was evaluated by ROC curve analysis for individual miRNA and the discriminatory accuracy presented by area under the curve (AUC) values (Supplementary Figure 4). The urine miRNAs level detected UC with high sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, we also performed ROC curve analysis for NIMBC (non-muscle invasive bladder cancer) (Figure 4) and the sensitivity and accuracy was similar to previous ROC that include samples of muscle-invasive and non-muscle invasive tumors (Supplementary Figure 4). In particular, the threshold of miR-205 (2^−ΔCt=551) in the NIMBC cohort was the same as shown in the all bladder cancer cohort. The ROC analysis support that miR-205 may be a potentail early detection marker of non muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Figure 4.

ROC curves for individual micro RNA expression in 177 normal and 28 non muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) urine samples were shown. y axis and x axis denote sensitivity and 1-specificity respectively. AUC for each of the miRNAs were calculated. The curve of miR-205 showed the high AUC value (0.844) and promising sensitivity (92.9%) and specificity (76.8%).

Discussion

Arsenic is a highly toxic element and a known human carcinogen involved in the etiology of various malignancies including bladder cancer. However, relatively little is known about the key mechanisms underlying arsenic-induced carcinogenicity. We developed an in vitro model for arsenic induced transformation in human normal urothelial cells that can be used to identify the molecular events that lead to urothelial carcinogenesis and progression after exposure to arsenic. At present, there is no suitable in vitro and in vivo model to study the stepwise molecular alterations by arsenic exposure in this cancer type. Studying stepwise progression will allow developing appropriate chemo-preventive strategy in a timely fashion that will also facilitate molecular marker development for risk assessment, diagnosis and prognosis. The bladder epithelium is one of the most affected tissues, as it is exposed to the carcinogen for several hours before it is expelled. In the present study we show that chronic arsenic exposure can promote cell proliferation of normal bladder epithelial cells within 6 months. However, significant changes in invasiveness and non-adherent growth in soft agar were observed after 8 months of treatment. These findings support the notion for a strong link between arsenic exposure and the risk for UC development.

Although humans are exposed to many forms of arsenic in the workplace or environment, inorganic arsenic exposure has the greatest impact on human health. In the general population, the main sources of inorganic arsenic are drinking water and food (e.g. rice, flour). As noted before, there is extensive epidemiologic evidence of increased risk for the development of UC associated with arsenic in drinking water (10). Recently, Waalkes et al. (25–29) demonstrated multi-organ carcinogenesis following transplacental exposure to 0, 42.5, or 85ppm (parts per million) arsenic during gestation days 8–18. Urinary bladder tumors (papilloma and carcinoma; 13% increased) were formed in the offspring of the females exposed to arsenic. The metabolism of arsenic in humans and animals is not well characterized and could be different. Therefore, our in vitro model is useful for identification of candidate stepwise molecular alterations critical for the genesis of human UC.

Oxidative stress and deregulation in MAPK and NF-kB pathways have been reported in skin cancer cases related to arsenic exposure (30) and also have been recently evaluated in UC cases (31, 32). By candidate gene approach, we identified deregulated expression of some genes involved in MAPK/PI3K/AKT signaling, a pathway that has been implicated even in early stages of urothelial carcinogenesis (33, 34). p-AKT, Cyclin D3, and m-TOR were overexpressed in the arsenic exposed cell lines which is consistent with the previous findings that alterations in these molecules play a notable role in UC oncogenesis (35, 36). Cyclin D3 was overexpressed in BFTC 909 cells, a cell line established from a donor who was exposed to high arsenic levels (11). The EGFR pathway has been reported to be activated in UC (37). Our results showed high expression of the p-EGFR in the arsenic treated cells compared to the untreated controls. It was previously reported that arsenic exposure disrupts cellular control over intermediates in the EGFR signaling pathway (including Src and ERK) (38–41), however a direct biochemical link between deregulated signaling and arsenic-induced transformation is yet to be fully established. Recently it has been reported that arsenic activates EGFR pathway signaling in the lung (24) which is consistent with our findings.

EMT, a de-differentiation program that converts adherent epithelial cells into individual migratory cells, is associated with the stemness and metastatic properties of cancer cells (42). Enhanced EMT characteristics as determined by the expression level of EMT related genes are associated with poor overall and metastasis-free survival in other solid tumor patients (43). miRNAs—highly conserved small RNA molecules that regulate gene expression—can act as cancer signatures, and as oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on their main target genes (44). A recent study has shown that miRNAs are involved in regulating cancer stem cells (CSCs) and EMT properties (45). For example, the miR-200 family members (miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429), which are tumor suppressive miRNAs, can reverse the EMT process and induce mesenchymal–epithelial transition via regulation of zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox (ZEB) 1 and ZEB2 (46). Additionally, the miR-200 family is required for the maintenance of CSCs properties of breast and oral cancer stem cells by directly targeting Bmi1 (47). And loss of miR-200 family (miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429) expression has been reported in several types of advanced carcinoma, including UC (48, 49). Recently, it was reported that arsenic exposure facilitates the initiation of a stem-like cell population in skin cancer oncogenesis (50–52); and EMT (53); and reduction in the levels of miR-200 family members (53). In our cell model, we observed morphological changes characterizing EMT and we found down-regulation of miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c in arsenic treated cells. These changes were associated with a decrease in E-cadherin levels, an increase in vimentin (Figure 2C), loss of cell adhesion with subsequent tumor invasion, and alterations of novel molecules related to stemness of cells. Interestingly, we did not observe morphological and phenotypic changes after 2.5 months withdrawal of arsenic, but did see overexpression of miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c following arsenic withdrawal. Thus, to develop miRNA based therapeutic and preventive strategies, future studies are needed to investigate the regulation of these EMT/MET related key miRNAs and their relationship to the EMT process and CSCs in UC. For example, while miR-205 was overexpressed in endometrial cancer (54) and non-small cell lung cancer (55–57), it’s expression was down-regulated in prostate cancer (58), melanoma (59–61) and breast cancers (62, 63). The claimed tumor suppressive functions of miR-205 in breast cancer is due to direct targeting of several oncogenes such as VEGFA, E2F1, E2F5, PKC epsilon and HER3(64) as well as offsetting EMT by suppressing ZEB1 and ZEB2 (64–66). Reduced expression of miR-205 has been reported in primary UC by different groups (67–69). However, the precise mechanisms of deregulated miR-205 in the initiation and progression of UC have not been elucidated. It is plausible that miR-205 plays a dual role in UC; for the initiation of UC miR-205 needs to be down-regulated while after a certain stage of tumor development it may play a role in tumor progression. Although a very small number of urine samples were tested from muscle invasive UC, the median value of miR-205 expression was 241, while it was 174 in non-muscle invasive UC.

From a DNA Methylation PCR Array panel of 22 genes in the Notch signaling pathway, we identified 4 differentially methylated genes after arsenic treatment. CTBP1 and NCSTN exhibited low methylation levels in the treated cells, whereas ERBB2 and NFKB2 showed high methylation levels in the arsenic treated cells. Expression levels determined by RT-PCR for all these 4 genes generally inversely associated with methylation status (Supplemetary Figure 2 A, B). It was previously reported by our group and others that gene-specific promoter hypomethylation and hypermethylation occur in cancers (70, 71). Furthermore, endogenous and exogenous exposures are related to promoter methylation (12, 72). For CTBP1 and NCSTN, we confirmed our array-based data by QMSP, however, we have not tested the promoter methylation status of these two genes in arsenic exposed human samples. IRB and subjects will not allow us to obtain primary urothelial tissues directly from the bladder wall from arsenic exposed population without any symptomatic condition. As urothelial cells directly shed into urine, we are in the process of testing methylation status of these genes in urine samples of arsenic exposed populations and appropriate controls.

Identification of causative agents can be challenging as exposures may occur by inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact both in occupational and non-occupational settings (73). As noted above, the urothelium is one of the most affected tissues, as it is exposed to carcinogens for several hours before they are expelled (12). Discovering new risk factors and confirming suspicions is difficult as there is typically a long latency period from time of exposure to the development of cancer and environmental carcinogens may occur together, limiting the ability to identify the risk posed by each individual exposure. Arsenic contamination in drinking water is a worldwide concern and remains a considerable cancer risk factor in many countries including Bangladesh, Taiwan, India, Mexico, China, Chile, Argentina and the USA (74). By far, arsenic in drinking water poses the greatest threat to human health (17, 75). Recent studies revealing high levels of arsenic in food such as poultry, rice and apple juices also highlight the importance of understanding arsenic’s carcinogenic mechanisms of action (76). Armed with such knowledge, effective preventive and therapeutic strategies for UC can be developed.

Unique expression patterns of miRNAs are observed in individual tissues and differ between cancer and normal tissues (57, 77). Furthermore, miRNAs are deregulated by carcinogeneic environmental exposure (78). Some miRNAs are overexpressed or down-regulated exclusively or preferentially in certain cancer types and due to exposure to certain carcinogens (79). In our in vitro study, we found that some of EMT related micro RNAs (miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c) were deregulated after arsenic treatment. Also, these in vitro data were consistent with our findings in human urine cohort. It could be due to the presence of molecularly altered mesenchymal cells in the urine of UC patients. Interestingly, miR-205 decreases in urine samples of arsenic exposed subjects compared to unexposed controls. Most notably, lower level of expression of miR205 was observed in the urine of UC cases in comparison with controls without any cancer. As no change or slight overexpression of miR-205 was observed in arsenic treated HUC1 cell lines, it might be the result of the dual role of miR-205 in tumor initiation and progression, or depend on cell line specific molecular characteristics. The UC specificity together with the remarkable stability, robustness, and reproducibility of miRNAs in urine warrant a larger appropriately powered investigation of miRNAs as biomarkers for cancer detection and risk assessment of different solid tumors including UC. Previous reports also suggest that the assessment of multiple miRNA expression levels, also referred to as miRNA signatures, can accurately predict prognosis in various types of cancers (80, 81).

Urine sediment generally consists of different cell types, including renal tubular cells, lymphocytes, red blood cells, normal urothelial cells, and tumor cells. As the proportion of non-tumor cells may differ between subjects, the obtained results could be influenced by varying expression of studied targets in different cell types. miRNAs in urine sediment reflect the level of intracellular expression, whereas miRNAs in supernatant are cell free and originate mainly from microvesicles (MVs) secreted into extracellular space. In a subset of samples we separated three fractions: 1) 600 µl taken directly from voided urine without any centrifugation; 2) 600 µl after centrifugation and 3) urine sediment after centrifugation. For the selected miRNAs we found essentially same patterns of expression (data not shown). We decided to use supernatant for our study as miRNAs in supernatant arise from MVs from urothelial cells secreted into the urine (82).

In summary, a) We established and characterized an urothelial cell model that will allow the scientific community to molecularly understand the stepwise carcinogenesis process of UC due to arsenic exposure. Further understanding of this model at the molecular level will allow development of preventive strategies in subjects who were exposed to arsenic or cigarette smoking; b) We demonstrated that arsenic exposure was related to miRNA deregulation that was reported roles in EMT, an emerging area of interest for cancer researchers; c) Our initial analysis of miR-200 family members and miR-205 indicated that deregulated miRNAs were potential biomarkers of arsenic exposure, and diagnostic markers of UC in urine. However, as UC is extremely heterogeneous, perhaps a cadre of miRNAs may synergistically improve the non-invasive detection of arsenic exposure and presence of UC. Further studies including a larger panel of UC related miRNAs should be tested for optimal selection of markers of arsenic exposure and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Young Clinical Scientist Award, Career Development award from SPORE in Cervical Cancer Grants P50 CA098252 (M.O. Hoque) and R01CA163594 (D.Sidransky and M.O. Hoque).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Martinez VD, Vucic EA, Becker-Santos DD, Gil L, Lam WL. Arsenic exposure and the induction of human cancers. J Toxicol. 2011;2011:431287. doi: 10.1155/2011/431287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CJ, Kuo TL, Wu MM. Arsenic and cancers. Lancet. 1988;1:414–415. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H, Li S, Liu J, Diwan BA, Barrett JC, Waalkes MP. Chronic inorganic arsenic exposure induces hepatic global and individual gene hypomethylation: implications for arsenic hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1779–1786. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Factor-Litvak P, Howe GR, Graziano JH, Brandt-Rauf P, Parvez F, et al. Arsenic exposure from drinking water, dietary intakes of B vitamins and folate, and risk of high blood pressure in Bangladesh: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:541–552. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen TJ, Novak P, Eblin KE, Gandolfi AJ, Futscher BW. Epigenetic remodeling during arsenical-induced malignant transformation. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1500–1508. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council. Arsenic in Drinking Water. The National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Research Council. Arsenic in Drinking Water. The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mousavi SM, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Risk of transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder in first- and second-generation immigrants to Sweden. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2010;19:275–279. doi: 10.1097/cej.0b013e3283387728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letasiova S, Medve’ova A, Sovcikova A, Dusinska M, Volkovova K, Mosoiu C, et al. Bladder cancer, a review of the environmental risk factors. Environ Health. 2012;11(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IARC. Some Drinking-Water Disinfectants and Contaminants, Including Arsenic. Vol. 84. IARC Press; 2004. Arsenic in drinking water. International agency for research on cancer monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risk to humans; pp. 269–477. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzeng CC, Liu HS, Li C, Jin YT, Chen RM, Yang WH, et al. Characterization of two urothelium cancer cell lines derived from a blackfoot disease endemic area in Taiwan. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1797–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brait M, Munari E, LeBron C, Noordhuis MG, Begum S, Michailidi C, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling and the PI3K–AKT pathway analysis associated with smoking in urothelial cell carcinoma. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1058–1070. doi: 10.4161/cc.24050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen T, Sen N, Noordhuis MG, Ravi R, Wu TC, Ha PK, et al. OGDHL is a modifier of AKT-dependent signaling and NF-kappaB function. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goebell PJ, Knowles MA. Bladder cancer or bladder cancers? Genetically distinct malignant conditions of the urothelium. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:409–428. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordway JM, Bedell JA, Citek RW, Nunberg A, Garrido A, Kendall R, et al. Comprehensive DNA methylation profiling in a human cancer genome identifies novel epigenetic targets. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2409–2423. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahsan H, Chen Y, Parvez F, Argos M, Hussain AI, Momotaj H, et al. Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study (HEALS): description of a multidisciplinary epidemiologic investigation. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2006;16:191–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahsan H, Chen Y, Kibriya MG, Slavkovich V, Parvez F, Jasmine F, et al. Arsenic metabolism, genetic susceptibility, and risk of premalignant skin lesions in Bangladesh. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1270–1278. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahsan H, Chen Y, Parvez F, Zablotska L, Argos M, Hussain I, et al. Arsenic exposure from drinking water and risk of premalignant skin lesions in Bangladesh: baseline results from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1138–1148. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahsan H, Chen Y, Wang Q, Slavkovich V, Graziano JH, Santella RM. DNA repair gene XPD and susceptibility to arsenic-induced hyperkeratosis. Toxicol Lett. 2003;143:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahsan H, Perrin M, Rahman A, Parvez F, Stute M, Zheng Y, et al. Associations between drinking water and urinary arsenic levels and skin lesions in Bangladesh. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1195–1201. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200012000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argos M, Parvez F, Rahman M, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Ahmed A, Hore SK, et al. Arsenic and lung disease mortality in bangladeshi adults. Epidemiology. 2014;25:536–543. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClintock TR, Chen Y, Parvez F, Makarov DV, Ge W, Islam T, et al. Association between arsenic exposure from drinking water and hematuria: results from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;276:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey KA, Wallace K, Smeester L, Thai SF, Wolf DC, Edwards SW, et al. Transcriptional Modulation of the ERK1/2 MAPK and NF-kappaB Pathways in Human Urothelial Cells After Trivalent Arsenical Exposure: Implications for Urinary Bladder Cancer. J Can Res Updates. 2012;1:57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrew AS, Mason RA, Memoli V, Duell EJ. Arsenic activates EGFR pathway signaling in the lung. Toxicol Sci. 2009;109:350–357. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waalkes MP, Liu J, Diwan BA. Transplacental arsenic carcinogenesis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waalkes MP, Liu J, Ward JM, Diwan BA. Enhanced urinary bladder and liver carcinogenesis in male CD1 mice exposed to transplacental inorganic arsenic and postnatal diethylstilbestrol or tamoxifen. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;215:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waalkes MP, Liu J, Ward JM, Powell DA, Diwan BA. Urogenital carcinogenesis in female CD1 mice induced by in utero arsenic exposure is exacerbated by postnatal diethylstilbestrol treatment. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1337–1345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waalkes MP, Ward JM, Diwan BA. Induction of tumors of the liver, lung, ovary and adrenal in adult mice after brief maternal gestational exposure to inorganic arsenic: promotional effects of postnatal phorbol ester exposure on hepatic and pulmonary, but not dermal cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:133–141. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waalkes MP, Ward JM, Liu J, Diwan BA. Transplacental carcinogenicity of inorganic arsenic in the drinking water: induction of hepatic, ovarian, pulmonary, and adrenal tumors in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;186:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(02)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An Y, Gao Z, Wang Z, Yang S, Liang J, Feng Y, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of oxidative DNA damage in arsenic-related human skin samples from arsenic-contaminated area of China. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Qu W, Cheng Y, Sun Y, Jiang Y, Zou T, et al. The Inhibitory Effect of Intravesical Fisetin against Bladder Cancer by Induction of p53 and Down-Regulation of NF-kappa B Pathways in a Rat Bladder Carcinogenesis Model. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SJ, Cho SC, Lee EJ, Kim S, Lee SB, Lim JH, et al. Interleukin-20 promotes migration of bladder cancer cells through extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mediated MMP-9 protein expression leading to nuclear factor (NF-kappaB) activation by inducing the up-regulation of p21(WAF1) protein expression. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5539–5552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.410233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sfakianos JP, Lin Gellert L, Maschino A, Gotto GT, Kim PH, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. The role of PTEN tumor suppressor pathway staining in carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Urol Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bambury RM, Rosenberg JE. Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma: Overcoming Treatment Resistance through Novel Treatment Approaches. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:3. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beltran AL, Ordonez JL, Otero AP, Blanca A, Sevillano V, Sanchez-Carbayo M, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of CCND3 gene as marker of progression in bladder carcinoma. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2013;27:559–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houede N, Pourquier P. Targeting the genetic alterations of the PI3K–AKT-mTOR pathway: Its potential use in the treatment of bladder cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim WT, Kim J, Yan C, Jeong P, Choi SY, Lee OJ, et al. S100A9 and EGFR gene signatures predict disease progression in muscle invasive bladder cancer patients after chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:974–979. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludwig S, Hoffmeyer A, Goebeler M, Kilian K, Hafner H, Neufeld B, et al. The stress inducer arsenite activates mitogen-activated protein kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 via a MAPK kinase 6/p38-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1917–1922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simeonova PP, Luster MI. Arsenic carcinogenicity: relevance of c-Src activation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234–235:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simeonova PP, Wang S, Hulderman T, Luster MI. c-Src-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by arsenic. Role in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2945–2950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka-Kagawa T, Hanioka N, Yoshida H, Jinno H, Ando M. Arsenite and arsenate activate extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 by an epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated pathway in normal human keratinocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1116–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang MH, Wu MZ, Chiou SH, Chen PM, Chang SY, Liu CJ, et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1alpha promotes metastasis. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:295–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicoloso MS, Spizzo R, Shimizu M, Rossi S, Calin GA. MicroRNAs--the micro steering wheel of tumour metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrc2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu CC, Chen YW, Chiou GY, Tsai LL, Huang PI, Chang CY, et al. MicroRNA let-7a represses chemoresistance and tumourigenicity in head and neck cancer via stem-like properties ablation. Oral Oncol. 47:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wellner U, Schubert J, Burk UC, Schmalhofer O, Zhu F, Sonntag A, et al. The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/ncb1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lo WL, Yu CC, Chiou GY, Chen YW, Huang PI, Chien CS, et al. MicroRNA-200c attenuates tumour growth and metastasis of presumptive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma stem cells. J Pathol. 223:482–495. doi: 10.1002/path.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gottardo F, Liu CG, Ferracin M, Calin GA, Fassan M, Bassi P, et al. Micro-RNA profiling in kidney and bladder cancers. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dyrskjot L, Ostenfeld MS, Bramsen JB, Silahtaroglu AN, Lamy P, Ramanathan R, et al. Genomic profiling of microRNAs in bladder cancer: miR-129 is associated with poor outcome and promotes cell death in vitro. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4851–4860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Y, Tokar EJ, Waalkes MP. Overabundance of putative cancer stem cells in human skin keratinocyte cells malignantly transformed by arsenic. Toxicol Sci. 125:20–29. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tokar EJ, Qu W, Waalkes MP. Arsenic, stem cells, and the developmental basis of adult cancer. Toxicol Sci. 120(Suppl 1):S192–S203. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong HP, Yu L, Lam EK, Tai EK, Wu WK, Cho CH. Nicotine promotes colon tumor growth and angiogenesis through beta-adrenergic activation. Toxicol Sci. 2007;97:279–287. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Zhao Y, Smith E, Goodall GJ, Drew PA, Brabletz T, et al. Reversal and prevention of arsenic-induced human bronchial epithelial cell malignant transformation by microRNA-200b. Toxicol Sci. 121:110–122. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung TK, Cheung TH, Huen NY, Wong KW, Lo KW, Yim SF, et al. Dysregulated microRNAs and their predicted targets associated with endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma in Hong Kong women. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1358–1365. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lebanony D, Benjamin H, Gilad S, Ezagouri M, Dov A, Ashkenazi K, et al. Diagnostic assay based on hsa-miR-205 expression distinguishes squamous from nonsquamous non-small-cell lung carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2030–2037. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markou A, Tsaroucha EG, Kaklamanis L, Fotinou M, Georgoulias V, Lianidou ES. Prognostic value of mature microRNA-21 and microRNA-205 overexpression in non-small cell lung cancer by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1696–1704. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.101741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hulf T, Sibbritt T, Wiklund ED, Bert S, Strbenac D, Statham AL, et al. Discovery pipeline for epigenetically deregulated miRNAs in cancer: integration of primary miRNA transcription. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dar AA, Majid S, de Semir D, Nosrati M, Bezrookove V, Kashani-Sabet M. miRNA-205 suppresses melanoma cell proliferation and induces senescence via regulation of E2F1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16606–16614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Philippidou D, Schmitt M, Moser D, Margue C, Nazarov PV, Muller A, et al. Signatures of microRNAs and selected microRNA target genes in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4163–4173. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y, Brenn T, Brown ER, Doherty V, Melton DW. Differential expression of microRNAs during melanoma progression: miR-200c, miR-205 and miR-211 are downregulated in melanoma and act as tumour suppressors. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:553–561. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iorio MV, Casalini P, Piovan C, Di Leva G, Merlo A, Triulzi T, et al. microRNA-205 regulates HER3 in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2195–2200. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu H, Zhu S, Mo YY. Suppression of cell growth and invasion by miR-205 in breast cancer. Cell Res. 2009;19:439–448. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greene SB, Herschkowitz JI, Rosen JM. The ups and downs of miR-205: identifying the roles of miR-205 in mammary gland development and breast cancer. RNA Biol. 2010;7:300–304. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.3.11837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu H, Mo YY. Targeting miR-205 in breast cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1439–1448. doi: 10.1517/14728220903338777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wszolek MF, Rieger-Christ KM, Kenney PA, Gould JJ, Silva Neto B, Lavoie AK, et al. A MicroRNA expression profile defining the invasive bladder tumor phenotype. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:794–801. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiklund ED, Bramsen JB, Hulf T, Dyrskjot L, Ramanathan R, Hansen TB, et al. Coordinated epigenetic repression of the miR-200 family and miR-205 in invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1327–1334. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee H, Jun SY, Lee YS, Lee HJ, Lee WS, Park CS. Expression of miRNAs and ZEB1 and ZEB2 correlates with histopathological grade in papillary urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoque MO, Kim MS, Ostrow KL, Liu J, Wisman GB, Park HL, et al. Genome-wide promoter analysis uncovers portions of the cancer methylome. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2661–2670. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shao C, Sun W, Tan M, Glazer CA, Bhan S, Zhong X, et al. Integrated, genome-wide screening for hypomethylated oncogenes in salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4320–4330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brait M, Ford JG, Papaiahgari S, Garza MA, Lee JI, Loyo M, et al. Association between lifestyle factors and CpG island methylation in a cancer-free population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2984–2991. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kiriluk KJ, Prasad SM, Patel AR, Steinberg GD, Smith ND. Bladder cancer risk from occupational and environmental exposures. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh AP, Goel RK, Kaur T. Mechanisms pertaining to arsenic toxicity. Toxicol Int. 2011;18:87–93. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.84258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferreccio C, Smith AH, Duran V, Barlaro T, Benitez H, Valdes R, et al. Case-Control Study of Arsenic in Drinking Water and Kidney Cancer in Uniquely Exposed Northern Chile. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nachman KE, Baron PA, Raber G, Francesconi KA, Navas-Acien A, Love DC. Roxarsone, inorganic arsenic, and other arsenic species in chicken: a u.s.-Based market basket sample. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:818–824. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Valencia-Quintana R, Sanchez-Alarcon J, Tenorio-Arvide MG, Deng Y, Montiel-Gonzalez JM, Gomez-Arroyo S, et al. The microRNAs as potential biomarkers for predicting the onset of aflatoxin exposure in human beings: a review. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:102. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Izzotti A, Pulliero A. The effects of environmental chemical carcinogens on the microRNA machinery. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yu SL, Chen HY, Chang GC, Chen CY, Chen HW, Singh S, et al. MicroRNA signature predicts survival and relapse in lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dvinge H, Git A, Graf S, Salmon-Divon M, Curtis C, Sottoriva A, et al. The shaping and functional consequences of the microRNA landscape in breast cancer. Nature. 2013;497:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang G, Chan ES, Kwan BC, Li PK, Yip SK, Szeto CC, et al. Expression of microRNAs in the urine of patients with bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.