Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal neuromuscular disorder caused by mutations in the Dmd gene. In addition to skeletal muscle wasting, DMD patients develop cardiomyopathy, which significantly contributes to mortality. Antisense oligonucleotides (AOs) are a promising DMD therapy, restoring functional dystrophin protein by exon skipping. However, a major limitation with current AOs is the absence of dystrophin correction in heart. Pip peptide-AOs demonstrate high activity in cardiac muscle. To determine their therapeutic value, dystrophic mdx mice were subject to forced exercise to model the DMD cardiac phenotype. Repeated peptide-AO treatments resulted in high levels of cardiac dystrophin protein, which prevented the exercised induced progression of cardiomyopathy, normalising heart size as well as stabilising other cardiac parameters. Treated mice also exhibited significantly reduced cardiac fibrosis and improved sarcolemmal integrity. This work demonstrates that high levels of cardiac dystrophin restored by Pip peptide-AOs prevents further deterioration of cardiomyopathy and pathology following exercise in dystrophic DMD mice.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe, debilitating, muscle wasting disorder caused by mutations that disrupt the reading frame of dystrophin mRNA, thus preventing production of this essential structural protein1. Cardiomyopathy is prominent in DMD patients and manifests with left ventricular dilation and hypertrophy, decreased fractional shortening and electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities2,3,4,5. As the disease progresses, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) develops, a condition prevalent in all DMD patients by adulthood3. While respiratory complications are still the major cause of death amongst DMD patients6, cardiomyopathy contributes significantly to premature death7. A number of cardiac pharmacotherapies are in clinical use8, however, no therapy is currently capable of correcting the underlying genetic defect and restoring dystrophin protein in the heart.

A multitude of experimental therapies have been investigated in an effort to restore9,10,11 or substitute12,13 for dystrophin. Antisense oligonucleotides (AOs) act to modulate splicing of dystrophin pre-mRNA to generate a truncated, but functional dystrophin protein14,15,16. 2′ O-Methyl phosphorothioate (2OMePS) and phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) AO chemistries have shown great promise in recent clinical trials17,18,19,20, with the most recent study reporting encouraging improvements in the 6 minute walk test following continuous treatment with Drisapersen (2OMePS) for 48 weeks21. Despite this, both chemistries have demonstrated both limited and variable ability to restore dystrophin, with negligible activity in heart22,23.

A powerful approach to improve AO potency is the conjugation of cell penetrating peptides to uncharged AOs, such as PMO24,25,26,27. While early generation peptide-PMOs were weakly active in heart, they were shown to have an influence on heart function in mdx mice displaying a mild cardiac phenotype27,28. Recently we have developed a novel series of highly active peptides known as Pip's (PMO internalising peptides) for PMO delivery29. This series of peptides comprise a hydrophobic central core with 2 flanking arginine-rich domains. This combines the improved skeletal muscle delivery capacity observed with the arginine rich B-peptide, with a hydrophobic sequence that dramatically enhances efficacy to create a new innovative series of peptides30. Previous studies showed that the hydrophobic region is critical for the delivery to the heart tissue as other arginine-rich peptides with a shorter hydrophobic region failed to achieve this. Progressive evolution of this peptide series through structure-activity studies has identified novel peptides with dramatically enhanced cardiac dystrophin restoration30,31,32. Pip6-PMO is currently the most potent class of peptide-PMO, demonstrating high levels of dystrophin protein restoration following a single low intravenous dose, most notably in cardiac muscle.

Here we sought to determine the benefit on cardiac function and pathology offered by Pip6-PMO conjugates which restore high levels of dystrophin in heart. To do this we modelled the treatment of DMD cardiomyopathy by repeat treating dystrophic mdx mice in which a moderate cardiomyopathy was induced by forced exercise over a twelve week period. Using stringent statistical measures, our results demonstrate that restoring high levels of dystrophin in heart with Pip6-PMO was sufficient to prevent exercise-induced progression of cardiomyopathy and to improve multiple indices of cardiac pathology.

Results

Repeat doses of Pip6f-PMO restore high levels of dystrophin protein in mdx mouse hearts

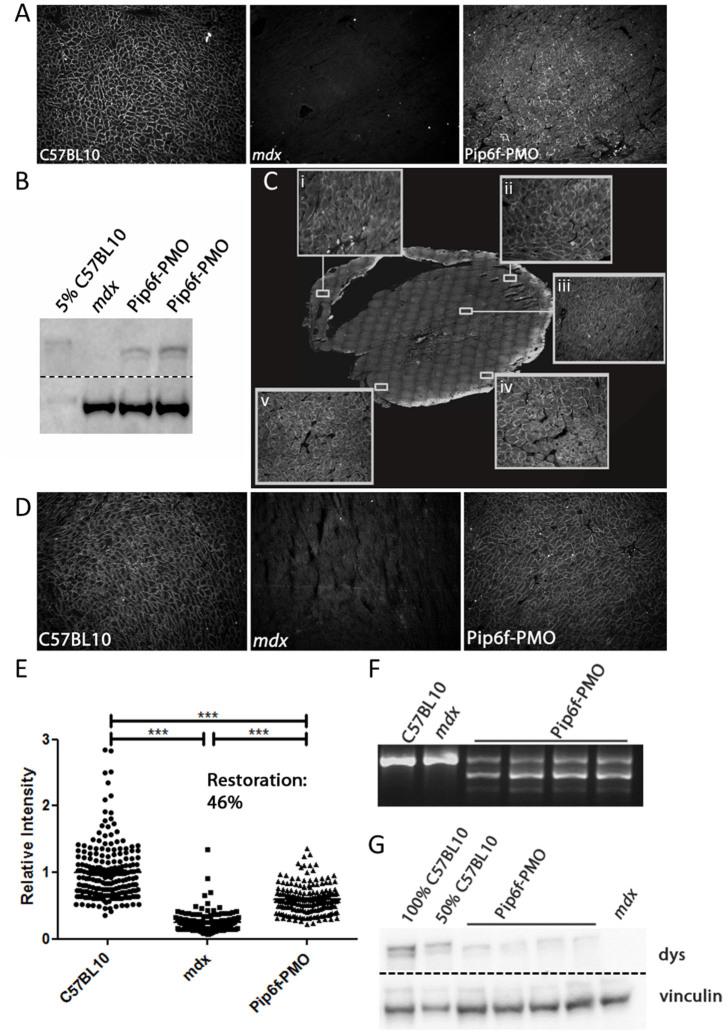

The widely used dystrophic mdx mouse model has a natural mutation in exon 23 of the Dmd gene which generates a premature termination codon. AOs directed towards exon 23 induce exon skipping and allow restoration of a shorter, but functional dystrophin protein. The most recent screen of Pip6-PMO conjugates revealed 2 lead candidates, Pip6a- and Pip6f-PMO, which were capable of restoring high dystrophin protein levels following a single administration. Pip6f-PMO was chosen for the purpose of this study and a single lower dose of 10 mg/kg, delivered intravenously (IV), was performed to confirm effective dystrophin restoration in heart. Figure 1 displays dystrophin protein restoration in mdx heart muscle fibres as measured by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1A) and western blotting (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1). The single, low dose treatment resulted in 5% dystrophin protein restoration in heart relative to C57BL/10 control. Therefore a longer treatment regimen was initiated whereby 12 week old mdx mice received IV administrations of 10 mg/kg on 4 consecutive days followed by 5 doses every 2 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical staining of the treated mdx hearts revealed widespread and homogenously distributed dystrophin protein restoration (Fig. 1C). This is indicated by the higher magnification inserts showing right ventricle (RV) wall (Fig. 1 C, i), outer left ventricle (LV) wall from apex (Fig. 1 C, ii) to base (Fig. 1 C iv and v) and inner myocardial dystrophin protein restoration (Fig. 1 C, iii). Representative images of dystrophin restoration in treated hearts relative to the C57BL/10 and mdx controls are also shown (Fig. 1D). Quantification of dystrophin staining was determined relative to a laminin co-stain. The dystrophin intensity values of multiple regions of interest, relative to the corresponding intensity value of laminin, were normalised to C57BL/10. This generated a recovery score of 46% in the hearts of the treated cohort (Fig. 1E). In addition, RT-qPCR revealed high levels of dystrophin transcript (32% of Dmd transcripts lacking exon 23, see Supplementary Fig. 3 B; RT-PCR also showed high Δ23 exon skipping, see Fig. 1F), and western blotting quantification indicated 28% protein restoration in heart tissue (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. 3 C).

Figure 1. Dystrophin restoration in heart following Pip6f-PMO treatment in mdx mice.

(A) Representative image of dystrophin immunohistochemical staining in heart following single 10 mg/kg Pip6f-PMO IV administration in mdx mice. (B) Dystrophin western blot of treated mdx hearts relative to 5% C57BL/10 following a single 10 mg/kg Pip6f-PMO administration. Approximately 5% dystrophin restoration observed. All samples run under the same experimental conditions and on the same SDS gel. Dotted line indicates where image was cropped. (C) Mice then underwent 4 daily injections followed by additional administrations every two weeks. Dystrophin immunohistochemical staining of treated heart with inserts indicating higher magnification of designated areas namely the right ventricle (RV) wall (C, i), outer left ventricle (LV) wall at apex (C, ii), inner myocardium (C, iii), and base (C iv and v) of heart. (D) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of dystrophin protein in exercised C57BL/10, mdx and Pip6f-treated mdx mouse hearts. (E) Quantification of immunohistochemical staining in hearts (from D) following multiple administrations. Dystrophin expression is determined relative to laminin co-stain. The scatter plots show the normalised relative intensity values for each region of interest. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Games-Howell post-hoc test to correct for variance heterogeneity (*** = P < 0.001, ** = P < 0.01, * = P < 0.05). (F) Representative images of reverse-transcriptase (RT) PCR illustrating Δ23 splicing in heart Pip6f-PMO treated cohort. All samples run under the same experimental conditions and on the same agarose gel. RT-qPCR was also performed (see Supplementary Fig. 3 B) which resulted in 32.3% Dmd transcripts lacking exon 23, following normalisation to exon 20–21 (SEM 3.1). (G) Representative images of western blots for Pip6f-PMO treated heart. For western blots, 10 μg of protein was loaded and dystrophin (dys) was quantified relative to vinculin loading control. All samples run under the same experimental conditions and on the same SDS gel. Dotted line indicates where image was cropped. For full agarose and SDS gels see Supplementary Fig. 1, 5&6.

Dystrophin was also restored in the diaphragm and other accessory respiratory muscles, intercostal (IM) and sternomastoid (SM) as well as tibialis anterior (TA) of the lower limb. Again immunohistological staining demonstrated extensive dystrophin protein restoration (Supplementary Fig. 3 A) with exceptionally high recovery scores between 74–104% (Supplementary Fig. 4). The RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 3 B) and western blot quantification (Supplementary Fig. 3 C&6) exhibited similar results with very high dystrophin transcript levels (77–86%) and between 58–101% restoration of dystrophin protein in the diaphragm, TA, IM and SM muscles. RT-PCR also showed complete skipping of exon 23 in these muscles (Supplementary Fig. 5). This demonstrates that the repeated low-dose Pip6f-PMO administration protocol successfully restored high levels of dystrophin in skeletal and cardiac muscles.

Exercised mdx mice exhibit dilated cardiomyopathy

The cardiac phenotype in 6 month old mdx mice is mild, but may be aggravated by exercise33,34. A forced exercise regimen was undertaken in control wild type C57BL/10 mice (n = 10) and mdx mice both untreated (n = 9) and treated with Pip6f-PMO (n = 10). From 12 weeks of age, mice were exercised on a treadmill 3 times every 2 weeks for 45 minutes (Supplementary Fig. 2). 10 mdx and 10 C57BL/10 unexercised mice were used as controls to monitor the effects of exercise alone. Mdx mice failed to run consistently, as they stopped intermittently and required constant encouragement (Supplementary Video 1). Indeed, 3 untreated mdx mice were removed from the study as they exhibited severe aversions to running, thereby reducing the sample size from 12 to 9 mice, which demonstrates their poor running capacity. C57BL/10 mice were markedly more active than their mdx counterparts (Supplementary Video 2).

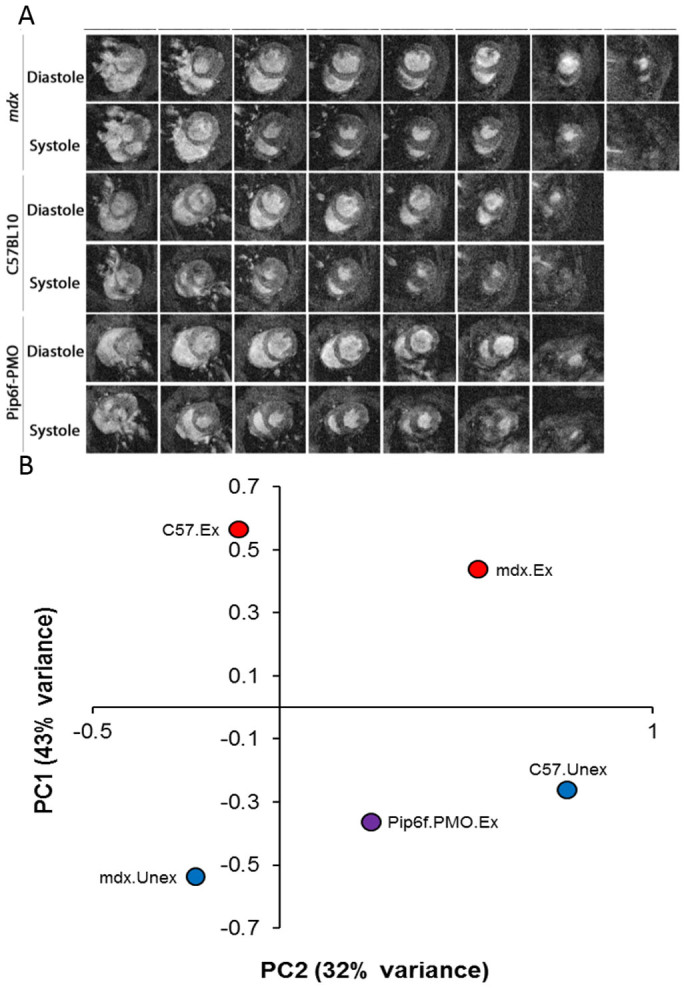

All groups of mice underwent cine-MRI at 24 weeks of age, 5 days after the last exercise event in the exercised groups. A range of cardiac parameters were determined and all normalised to body weight with the exception of ejection fraction (EF) (Table 1). Data was analysed using stringent statistical tests (two-way ANOVA and one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc and Games-Howell post-hoc). As previously described, most LV parameters were unchanged between the unexercised mdx and C57BL/10 cohorts at 24 weeks of age (with the exception of LV cardiac output; LV cardiac output (CO))28,35. The exercise regimen was developed to moderately increase the workload on the heart without causing damage to cardiac tissue. The exercise had a significant effect on the untreated mdx hearts for a number of cardiac measurements (increased average mass, end diastolic volume and end systolic volume with consequential decrease in LV EF; interaction effect between exercise and mouse groups determined by two-way ANOVA - see Table 1). These changes suggest reduced contractility of the heart and the onset of cardiac hypertrophy. This is complemented by Fig. 2 A which illustrates thicker LV walls of the mdx exercised cohort in scans 4–6 at systole. The heart rate was also elevated, with resultant increase in CO, suggesting compensatory mechanisms to increase cardiac contractility (Table 1).

Table 1. Cardiac function parameters measured by cine-MRI in all cohorts. Table listing the mean values for all left and right ventricle cardiac parameters and standard error of the mean (SEM). Parameters were normalised to body weight. Note: The exceptions to this is the ejection fraction which is represented as a percentage and heart rate calculated as beats per minute (BPM). Weights are in grams. Statistical significance values were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (TU), or Games-Howell (GH) post-hoc test to correct for variance heterogeneity. Each cohort is compared to all other cohorts.

| One-way ANOVA statistical significance | Two-way ANOVA | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57 Unex | SEM | C57 Ex | SEM | mdx Unex | SEM | mdx Ex | SEM | Pip6f-PMO Ex | SEM | Interaction effect between exercise and mouse group | ||

| Left ventricle/body weight | Average MassGH | 3.75 | ±0.20 | 3.45/ | ±0.07 | 3.43/ | ±0.08 | 3.91~#+ | ±0.11 | 3.45/ | ±0.05 | 0.002 |

| End Diastolic VolumeTU | 1.96 | ±0.14 | 1.67 | ±0.06 | 1.77 | ±0.05 | 2.10 | ±0.20 | 1.88 | ±0.03 | 0.007 | |

| End Systolic VolumeTU | 0.74 | ±0.12 | 0.50/ | ±0.04 | 0.65 | ±0.08 | 0.90+ | ±0.15 | 0.71 | ±0.04 | 0.02 | |

| Stroke VolumeGH | 1.22 | ±0.04 | 1.17 | ±0.05 | 1.12 | ±0.04 | 1.20 | ±0.06 | 1.17 | ±0.03 | N/S | |

| Cardiac outputTU | 0.52# | ±0.02 | 0.48 | ±0.02 | 0.42/* | ±0.03 | 0.52# | ±0.02 | 0.44 | ±0.01 | 0.003 | |

| Left ventricle% | Ejection FractionTU | 63.82 | ±2.65 | 70.08/ | ±2.26 | 63.98 | ±3.59 | 58.56+ | ±2.48 | 62.47 | ±1.93 | 0.04 |

| Right ventricle/body weight | End Diastolic VolumeTU | 1.64 | ±0.04 | 1.52/ | ±0.08 | 1.53/ | ±0.05 | 1.79+# | ±0.08 | 1.68 | ±0.06 | 0.004 |

| End Systolic VolumeTU | 0.45// | ±0.02 | 0.38 ##///~ | ±0.03 | 0.55++ | ±0.03 | 0.66**+++ | ±0.05 | 0.54+ | ±0.04 | 0.009 | |

| Stroke VolumeGH | 1.18# | ±0.04 | 1.14 | ±0.07 | 0.98* | ±0.04 | 1.13 | ±0.05 | 1.14 | ±0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Cardiac outputTU | 0.50### | ±0.02 | 0.47# | ±0.03 | 0.37***//+ | ±0.03 | 0.49## | ±0.02 | 0.43 | ±0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Right ventricle % | Ejection FractionTU | 72.23##// | ±1.01 | 74.87###///~ | ±1.65 | 64.36**+++ | ±1.74 | 63.34**+++ | ±1.65 | 68.35+ | ±1.24 | N/S |

| BPM | Heart RateTU | 427.02 | ±15.42 | 410.02 | ±11.04 | 373.64 | ±20.22 | 433.28 | ±12.42 | 376.72 | ±13.21 | 0.03 |

| Gram | Body weightGH | 32.40 | ±0.77 | 31.00/~~ | ±0.33 | 32.40 | ±1.20 | 33.33+ | ±0.62 | 33.90++ | ±0.53 | N/S |

*significantly different to C57 Unex, + significantly different to C57 Ex, # significantly different to mdx Unex, / significantly different to mdx Ex and ~ significantly different to Pip6f-PMO Ex. Number of symbols denotes significance i.e. *** = P < 0.001, ** = P < 0.01, * = P < 0.05. Two-way ANOVA was also performed to determine interaction effects between exercise and mouse groups.

Figure 2. Contiguous cine-MRI images and correlation plot of cardiac function parameters in exercised mdx mice following Pip6f-PMO treatment.

(A) Series of contiguous images at 1 mm increments throughout the entire hearts of C57BL/10, mdx and Pip6f-PMO treated mice during diastole and systole (exercised cohorts only). Images displays significantly larger hearts for mdx untreated cohort. (B) Correlation plot of cardiac function parameters measured by cine-MRI in exercised mdx mice following Pip6f-PMO treatment. Principal component analysis plot of all left and right ventricle cardiac function parameters. The two components demonstrate the highest percentage of variance on the Y-axis (component 1, 43%) and X-axis (component 2, 32%). This plot shows how treated mice tend to display values of the component 1 intermediate between C57BL/10 and mdx mice and values of the component 2 corresponding to unexercised mice.

These results are complemented by the one-way ANOVA analysis whereby the mdx and C57BL/10 exercised cohorts were directly compared (mdx mice: LV ESV larger, with reduced LV EF, RV EDV and ESV larger with consequential decrease in EF; Table 1).

Pip6f-PMO administration prevents onset of cardiomyopathy

While exercise induced a strong heart phenotype in the mdx mice, treatment with Pip6f-PMO stabilised cardiac function, as demonstrated by cine-MRI. Moreover, in contrast to the untreated exercised mdx cohort which required much encouragement, the Pip6f-PMO group ran very well (Supplementary Video 3). The most notable cine-MRI result was the significantly larger average mass of the heart for the exercised mdx cohort compared to the Pip6f-PMO treated group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2A and Table 1). All LV and most of the RV cardiac parameters of the Pip6f-PMO treated cohort were comparable to the C57BL/10 cohort (Table 1). In addition, the Pip6f-PMO treated cohort and the unexercised mdx cohort (Table 1) exhibited very similar cardiac parameter values. Indeed, when all LV and RV MRI parameters were correlated using a principal component plot, the treated cohort exhibits a similar profile to the C57BL/10 and mdx unexercised cohorts (Fig. 2B). Overall the untreated, exercised mdx mouse cohort developed a dilated and compensated cardiomyopathy; however Pip6f-PMO treatment prevented hypertrophy and prevented exercise induced deterioration of cardiac function in mdx hearts.

Reduction of cardiac damage markers and heart pathology in Pip6f-PMO treated mice

It was anticipated that the exercise-induced increase in cardiac workload combined with the absence of dystrophin in the mdx heart would result in an increase in tissue biomarkers of cardiac injury or damage.

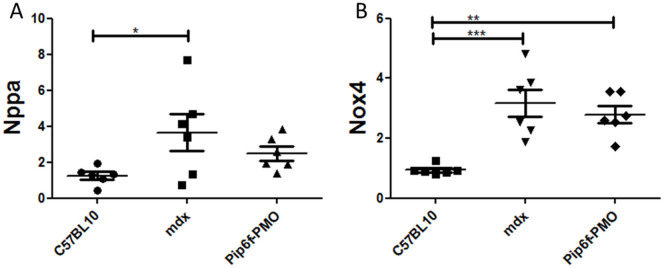

Two such markers, Nppa and Nox4, were measured 5 days following exercise in mdx mouse hearts. Atrial natriuretic peptide (Nppa) is secreted by the atria in response to haemodynamic overload or stress36. Its release results in the reduction of blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy and is therefore considered a compensatory mechanism36 but also serves as a diagnostic measure of heart failure37. Quantitative assessment (RT-qPCR) revealed elevated expression of this gene in the untreated exercised mdx group which was significantly higher than in the C57BL/10 cohort (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). The expression of Nppa in the Pip6f-PMO treated cohort was partially normalised.

Figure 3. Gene expression analysis for markers of cardiac injury in exercised mdx mice following Pip6f-PMO treatment.

RT-qPCR analysis of Nppa (A) and Nox4 (B) in heart tissue normalised to C57BL/10 cohort. The untreated mdx exercised cohort reveals elevated expression of these injury markers whereas there is partial normalisation for the Pip6f-PMO cohort. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (*** = P < 0.001, ** = P < 0.01, * = P < 0.05).

NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) has been associated with increases in oxidative stress38 and has previously been described in mdx mouse studies to be associated with cardiac dysfunction39. Nox4 expression in the mdx exercised cohort was markedly elevated compared to C57BL/10 mice (P < 0.001; Fig. 3B). Nox4 levels in the Pip6f-treated cohort remained elevated, but to a lesser extent than in the mdx group (P < 0.01).

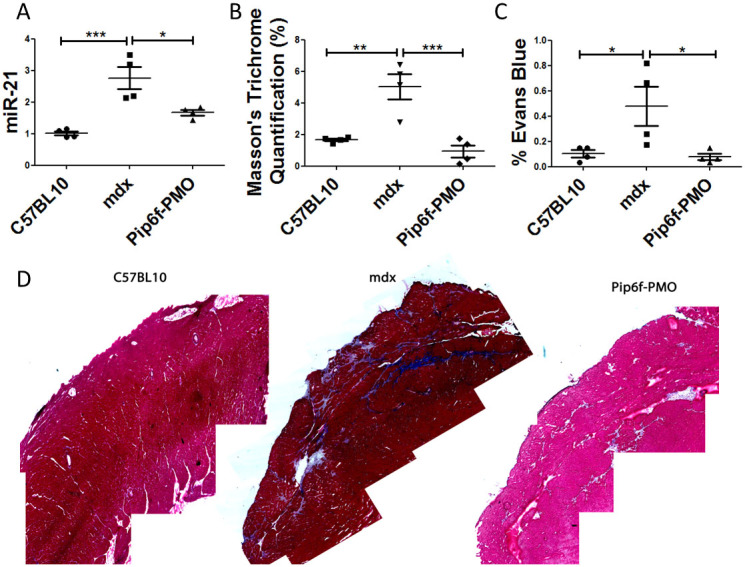

MicroRNA (miRNA) 21 is another biomarker of cardiac injury, specifically, it has been directly linked to myocardial fibrosis during hypertrophy40. Mdx mice showed an increase in miR-21 expression over wild type mice suggesting an increase in interstitial fibrosis (P < 0.001; Fig. 4A). Treatment with Pip6f-PMO partially normalised miR-21 expression (P < 0.05) over the untreated counterpart. The quantification of Masson's trichrome staining, which stains for collagen deposition, confirmed this observation of significantly reduced interstitial fibrosis in Pip6f-PMO treated mdx hearts (Fig. 4B). Again the untreated mdx hearts exhibited greater collagen deposition compared to C57BL/10 (P < 0.01) and Pip6f-PMO (P < 0.001) cohorts. Images of cardiac fibrosis strongly indicated the greater collagen deposition in untreated mdx hearts that was significantly reduced by treatment (Fig. 4D). Moreover, infiltration of Evans blue dye in the hearts of Pip6f-treated mice was also significantly reduced compared to untreated counterparts (P < 0.05; Fig. 4C). This showed that Pip6f-PMO treatment prevented sarcolemmal damage following exercise. These results denote a significant reduction in cardiac pathology in the treated mouse cohort.

Figure 4. Reduction in cardiac pathology as determined by the detection of fibrosis and sarcolemmal damage in the hearts of exercised mdx mice following Pip6f-PMO treatment.

(A) RT-qPCR analysis of miRNA-21 in heart tissue normalised to C57BL/10 cohort. (B) Quantification of Masson's trichrome staining in hearts of exercised cohorts. (C) Evans blue dye infiltration into heart following exercise. (D) Masson's trichrome images of worst areas of collagen deposition. miRNA-21 expression and Evans blue dye leakage of Pip6f-PMO hearts is normalised in contrast to untreated control. In addition Masson's trichrome staining is reduced and the representative images indicate less fibrosis then the untreated mdx cohort. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (*** = P < 0.001, ** = P < 0.01, * = P < 0.05).

Blood analyses of markers for toxicity were performed to determine the safety of the Pip6f-PMO treatment regimen. Plasma toxicity markers, including markers of hepatic and renal function, were unaffected by Pip6f-PMO treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Discussion

While AO exon skipping clinical trials appear promising for DMD17,18,20,41,42, the high incidence of cardiomyopathy in these patients, with associated high levels of mortality, indicate that restoring dystrophin protein in heart to modulate the cardiac phenotype is of high priority. Here we evaluated the therapeutic value of a highly potent peptide-PMO, Pip6f-PMO, which we previously demonstrated to be active in heart30. Using a forced exercise model we show that repeat treatment with Pip6f-PMO induced high levels of dystrophin restoration in heart which prevented cardiac hypertrophy and stabilised other cardiac parameters as determined by cine-MRI. Moreover, we also show that treatment ameliorates cardiac pathology as evidenced by reduced collagen and interstitial fibrosis and improved sarcolemmal integrity. These results suggest that high levels of dystrophin protein restoration in heart early in the course of DMD disease progression might have a significant clinical benefit.

A major limitation of the mdx mouse model of DMD is the mild cardiomyopathy which typically manifests only with advanced age35. Whilst previous peptide-PMO studies have shown dystrophin restoration in heart and some influence on cardiac function parameters, they either required dobutamine administration to stress the heart of young mdx mice27 or observed improvements predominantly in the RV of 6 month old mice28. Dobutamine administration is commonly used to exacerbate cardiac dysfunction in mdx mice, however this acute insult does not model the effect of progressive macro-structural changes to the myocardium typical of a degenerative cardiomyopathy. In order to induce a cardiomyopathy which recapitulates the DMD patient phenotype, mice were subjected to a moderate exercise protocol over a 12 week period. This exercise regimen was based on the ‘Treat NMD protocol and guidelines' for exercising mdx mice (http://www.treat-nmd.eu). As this protocol has only previously been utilised in assessing skeletal muscle pathology, the exercise regimen was modified. The established exercise regimen was designed so as to cause minimal damage to the heart while moderately increasing the cardiac workload in order to advance the stage of cardiomyopathy incrementally. This 12 week time-course was sufficient to yield significant functional changes in the untreated mdx heart (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Treadmill running was favoured over voluntary running, since wild-type mice are known to run further distances than mdx mice33,43,44.

Cine-MRI is considered the optimal technique for cardiac function assessment in small animals45. Cine-MRI demonstrated that moderate forced exercise was capable of inducing dilated cardiomyopathy in mdx mice, characterised by an enlarged heart and reduced contractility. This condition, dilated cardiomyopathy, is exhibited in all DMD patients by the age of 18 years3,46. However, treatment with Pip6f-PMO prevented these events. The low dose administration regimen of Pip6f-PMO induced high dystrophin protein restoration levels in skeletal muscle and approximately 28% dystrophin protein restoration in the heart. This level of dystrophin prevented hypertrophy, with left and right ventricular volumes in the normal range. In addition, LV CO and RV CO were stable. This study indicates that approximately 28% dystrophin restoration is sufficient to prevent the onset of exercised-induced dilated cardiomyopathy and maintain cardiac function.

In addition to MRI changes, the untreated exercised mdx cohort exhibited elevated markers of oxidative damage and injury, and fibrosis (collagen deposition) and sarcolemmal damage in the heart. This compares well with previous studies that show clear myocardial changes following exercise in mdx mice33,34,47. In contrast, the Pip6f-PMO treatment prevented injury in the mdx heart. It further reduced cardiac pathology as shown by significant reductions in cardiac fibrosis and sarcolemmal damage which demonstrated the protective capacity of a highly effective dystrophin restoration treatment. Cardiac fibrosis generally correlates with the decline in cardiac function48,49 and therefore the marked reduction of myocardial fibrosis would likely have had a beneficial effect on cardiac function.

Our data suggests that restoring high levels of dystrophin protein in heart is likely to prevent the progression of cardiomyopathy in DMD patients. This supports the idea that DMD patients should be treated as early as possible. It has been reported that mild molecular abnormalities in mdx heart manifest as early as 10–12 weeks of age and therefore it is likely that our treatment was not initiated prior to the onset of disease50,51. It is possible that an even greater degree of cardio-protection would have been observed if Pip6f-PMO treatment had been initiated earlier, in younger mdx mice. In addition, this work demonstrates ‘proof of principle' for the utilisation of Pip6-conjugated AOs for the correction of cardiac structural protein defects. Three genes encoding cardiac sarcomeric proteins, MYH7, MYBPC3 and TNNT2 have been implicated in over 70% of all familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathies52 and indeed exon skipping technology has already been demonstrated as a possible therapy for Mbpc3 mutations53. Thus Pip-PMO compounds could have wider application in the treatment of many familial cardiac defects.

Methods

Synthesis of Peptide-PMO Conjugates

Pip6f Ac-(RXRRBRRXRFQILYRXRBRXRB)-COOH, where X is aminohexanoic acid and B is β-alanine) was synthesized by standard solid phase Fmoc chemistry and purified by HPLC. The PMO sequence (5'-GGCCAAACCTCGGCTTACCTGAAAT-3') was purchased from Gene Tools LLC. Pip6f was conjugated to PMO through an amide linkage at the 3' end of the PMO, followed by purification by HPLC as previously described30. The final product was analysed by MALDI-TOF MS and HPLC. Peptide-PMO conjugates were dissolved in sterile water and filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate membrane before use.

Animals and Intravenous Injections

Male C57BL/10 mice were attained from Harlan Laboratories (Oxford, UK) and mdx mice were bred in house at the Biomedical Sciences Unit (University of Oxford, UK). All procedures were authorized and approved by the University of Oxford ethics committee and UK Home Office (project licence 30/2907). Procedures were carried out in the Biomedical Sciences Unit, University of Oxford, in accordance with ‘Laboratory Animal Handbooks NO.14; The Design of Animal Experiments (2010)'. For the treated cohort, 12 week old male mdx mice were injected via the tail vein with Pip6f-PMO prepared in 0.9% saline solution at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Mice were injected daily for 4 days followed by additional administrations every two weeks; 9 doses in total.

Exercise Regimen

This exercise regimen was modified from a Treat-NMD protocol (http://www.treat-nmd.eu/downloads/file/sops/dmd/MDX/DMD_M.2.1.001.pdf). The Exer 3/6 treadmill (Columbus Instruments, USA) was used for the exercised cohorts. Exercise commenced at 12 weeks of age and mice were exercised 3 times every 2 weeks for a 12 week period. Mice were allowed 2 minutes for familiarisation. The exercise regimen was started at 5 m/min and gradually increased in 1 m/min increments to 10 m/min for the first 2 exercise days. For the following 6 exercise sessions, mice were run for 45 minutes with the speed of the treadmill incrementally increased to 12 m/min. The mice were run at 12 m/min for 45 minutes for the remaining exercise sessions.

Cine-MRI

All mice underwent cardiac cine-MRI at 24 weeks of age, as previously described35. Mice were anaesthetised and placed in the supine position into a purpose built cradle. ECG electrodes were inserted into the forepaws of the mouse and the respiration loop was taped across the abdomen. Once the mouse was secured, with a stable ECG measurement, the cradle was lowered into a vertical-bore, 11.7 T MR system (Magnex Scientific, Oxon, UK) with a 40 mm birdcage coil (Rapid Biomedical, Wurzburg, Germany). Images were acquired using a Bruker console running Paravision 2.1.1 (Bruker Medical, Ettlingen, Germany). The entire left and right ventricles were imaged by taking a contiguous stack of cine images in 1 mm increments. Images were analysed using ImageJ software (NIH Image, Bethesda, MD). The epicardial and endocardial borders were outlined using the ImageJ free-hand tool at end-diastole and end-systole.

Following MRI, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation, and muscles and other tissues harvested and snap-frozen in cooled isopentane before storage at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry and Quantification

Transverse sections of tissue samples were sectioned (8 μm thick) and co-stained with rabbit-anti-dystrophin (Abcam) and rat anti-laminin (Sigma) as previously described30. Dystrophin was quantified relative to laminin co-stain using ImagePro software (MediaCybernetics) and normalised to C57CL/10. Briefly, 4 images of dystrophin and the corresponding laminin fields were taken for each section. Following the Arechavala-Gomeza approach54, 10 regions of interest were randomly placed on the laminin image which was overlaid on the corresponding dystrophin image to attain the minimum and maximum fluorescence intensity (Image-Pro, Media Cybernetics, Inc.). Data was normalised relative to C57BL/10. The percentage recovery score was calculated using the following equation: (dystrophin recovery of treated mdx mice-dystrophin recovery of untreated mdx mice)/(dystrophin recovery of C57BL/10 mice-dystrophin recovery of untreated mdx mice); as described on the TREAT-NMD website (http://www.treat-nmd.eu/downloads/file/sops/dmd/MDX/DMD_M.1.1_001.pdf).

RT-PCR and RT-qPCR for Mouse Tissues

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instructions. For the RT-PCR reaction, 400 ng of RNA template was used in a 50 μl reverse transcription reaction using One Step RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN) and gene specific primers as previously described30. Two microlitres of cDNA was amplified in a 50 μl nested PCR (QIAGEN PCR kit).

For RT-qPCR, 0.5–1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems). Gene specific primers sets (IDT) for markers of damage (Nppa- Assay Mm.PT.58.8820983 and Nox4- Assay MM.PT.58.12973594.g) were amplified using TaqMan Universal mastermix (Applied Biosystems) run on the StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The quantity mean values for each gene were normalised relative to the reference gene, Ywhaz (Assay Mm.PT.39a.22214831). For Dmd transcript levels, 25 ng of cDNA template was amplified using Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix. Levels of Dmd exon 23 skipping were determined by multiplex qPCR of FAM-labelled primers spanning Exon 20–21 (Assay Mm.PT.47.9564450, Integrated DNA Technologies) and HEX-labelled primers spanning Exon 23–24 (Mm.PT.47.7668824, Integrated DNA Technologies). The percentage of Dmd transcripts lacking exon 23 was determined by normalising Dmd exon 23–24 amplification levels to Dmd exon 20–21 levels.

miRNA qPCR was performed as previously described55. To quantify mature miRNA abundance, small RNA TaqMan Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used according to manufacturer's instructions. As described previously56, 5 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the TaqMan miRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). 1.33 μl of RT reaction were used in each qPCR and miR-16 was served as endogenous normalizer miRNA.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot

Samples were homogenised and quantified by Bradford assay (Sigma) as previously described30. Ten micrograms of untreated and treated mdx protein, and 5 μg and 2.5 μg of C57BL/10 protein (positive control) were loaded onto 3–8% Tris-Acetate gels (Invitrogen). Protein was blotted onto PVDF membrane and probed for dystrophin using DYS1 (Novocastra) and loading control, vinculin (Sigma). Primary antibodies were detected using IRDye 800 CW goat-anti mouse IgG (Licor). Western blots were imaged (LiCOR Biosciences) and analysed using the Odyssey imaging system. Western blots were quantified by calculating dystrophin protein expression relative to vinculin loading control.

Masson's Trichrome Staining

Longitudinal sections of heart samples were cut (8 μm thick) and stained with a Masson's trichrome kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). Whole sections were imaged and reassembled. Fibrosis was quantified as a percentage of surface area stained with Masson's trichrome measured using ImageJ.

Evans Blue Dye Administration

Between 3 and 4 mice from each cohort were injected intra-peritoneally with 1% Evans blue dye (10 μl/g of mouse; Sigma) and heart tissues were harvested 20 hours later. Hearts were sectioned (8 μm), placed in acetone for 10 minutes, washed with PBS and cover slipped. Evans blue infiltration was visualised using a Leitz DM RBE fluorescent microscope (Leica) and the entire section was imaged using Axiovision Rel 4.7 Software (Zeiss). The images were collated so that the entire section could be observed and the surface area of Evans blue staining was quantified using the threshold function of ImageJ software.

Clinical Biochemistry

Plasma samples were extracted from the jugular vein of mdx mice immediately after sacrifice by CO2 inhalation. Analysis of toxicity biomarkers was performed by a clinical pathology lab, Mary Lyon Centre, MRC, Harwell, UK.

Statistical Analysis

All values reported are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Regarding cine-MRI data, each cohort was directly compared using Students t-test. microRNA RT-qPCR of murine heart tissues. Statistical significance was calculated with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22.0) using one- way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (TU), or Games-Howell post-hoc test to correct for variance heterogeneity. Variance heterogeneity was assessed by Levene's tests. Two-way ANOVA was also performed to determine the interaction effect between exercise and the mouse groups (ie. mdx and C57BL/10). Principal component analysis was conducted on a correlation matrix using the function prcomp() in R (http://www.r-project.org/).

Author Contributions

C.A.B., A.F.S., M.J.G. and M.J.A.W. designed the research. C.A.B., C.A.C., S.M.H., A.M.L.C.S., C.G. and G.M. performed the research. C.A.B., C.A.C., M.A.V., T.C.R. and K.C. analysed the data and C.A.B. and M.J.A.W. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1

Supplementary Video 2

Supplementary Video 3

Acknowledgments

C.A.B. is supported by a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign and the British Heart Foundation (Grant PG/14/2/30595). A.F.S. is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust/DOH Health Innovation Challenge Fund. The work in the laboratory of M.J.G. was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC programme number U105178803).

Footnotes

A.F.S. and M.J.G. (MRC Technology) and C.A.B., S.M.H. and M.J.A.W. (University of Oxford) are named contributors and benefactors of a patent filed for Pip-PMO technologies described herein. C.A.C., A.M.L.C.S., C.G., G.M., M.A.V., T.C.R. and K.C. declare no competing financial interests

References

- Emery A. E. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases--a world survey. Neuromuscul Disord 1, 19–29 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmann C., Kececioglu D., Korinthenberg R. & Dittrich S. Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic findings of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne and Becker-Kiener muscular dystrophies. Pediatric cardiology 26, 66–72 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G., Comi L. I., Politano L. & Bain R. J. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Cardiol 26, 271–277 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushby K., Muntoni F. & Bourke J. P. 107th ENMC international workshop: the management of cardiac involvement in muscular dystrophy and myotonic dystrophy. 7th–9th June 2002, Naarden, the Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord 13, 166–172 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan A. & Fayaz M. Prevalence of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne and Becker's muscular dystrophy. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC 20, 7–13 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benditt J. O. & Boitano L. Respiratory support of individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: toward a standard of care. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America 16, 1125–1139 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connuck D. M. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of cardiomyopathy in children with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy: a comparative study from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Am Heart J 155, 998–1005 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goemans N. & Buyse G. Current treatment and management of dystrophinopathies. Current treatment options in neurology 16, 287 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton-Davis E. R., Cordier L., Shoturma D. I., Leland S. E. & Sweeney H. L. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest 104, 375–381 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac L. R. et al. Persistent expression of FLAG-tagged micro dystrophin in nonhuman primates following intramuscular and vascular delivery. Mol Ther 18, 109–117 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyenvalle A. et al. Rescue of severely affected dystrophin/utrophin-deficient mice through scAAV-U7snRNA-mediated exon skipping. Hum Mol Genet 21, 2559–2571 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei E. et al. Utrophin up-regulation by an artificial transcription factor in transgenic mice. PLoS One 2, e774 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley J. M. et al. Daily treatment with SMTC1100, a novel small molecule utrophin upregulator, dramatically reduces the dystrophic symptoms in the mdx mouse. PLoS One 6, e19189 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson G., Hill V. & Graham I. R. Screening for antisense modulation of dystrophin pre-mRNA splicing. Neuromuscul Disord 12 Suppl 1, S67–70 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter J. et al. Systemic delivery of morpholino oligonucleotide restores dystrophin expression bodywide and improves dystrophic pathology. Nat Med 12, 175–177 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunckley M. G., Manoharan M., Villiet P., Eperon I. C. & Dickson G. Modification of splicing in the dystrophin gene in cultured Mdx muscle cells by antisense oligoribonucleotides. Hum Mol Genet 7, 1083–1090 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goemans N. M. et al. Systemic administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med 364, 1513–1522 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deutekom J. C. et al. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med 357, 2677–2686 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirak S. et al. Restoration of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex after exon skipping therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther 20, 462–467 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinali M. et al. Local restoration of dystrophin expression with the morpholino oligomer AVI-4658 in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a single-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol 8, 918–928 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voit T. et al. Safety and efficacy of drisapersen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DEMAND II): an exploratory, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet Neurol 13 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malerba A. et al. Chronic systemic therapy with low-dose morpholino oligomers ameliorates the pathology and normalizes locomotor behavior in mdx mice. Mol Ther 19, 345–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q. L. et al. Systemic delivery of antisense oligoribonucleotide restores dystrophin expression in body-wide skeletal muscles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 198–203 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jearawiriyapaisarn N. et al. Sustained dystrophin expression induced by peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers in the muscles of mdx mice. Mol Ther 16, 1624–1629 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H. et al. A fusion peptide directs enhanced systemic dystrophin exon skipping and functional restoration in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet 18, 4405–4414 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H. et al. Functional rescue of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice by a chimeric peptide-PMO. Mol Ther 18, 1822–1829 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B. et al. Effective rescue of dystrophin improves cardiac function in dystrophin-deficient mice by a modified morpholino oligomer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 14814–14819 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A. et al. Diaphragm rescue alone prevents heart dysfunction in dystrophic mice. Hum Mol Genet 20, 413–421 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abes S. et al. Efficient splicing correction by PNA conjugation to an R6-Penetratin delivery peptide. Nucleic Acids Res 35, 4495–4502 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts C. et al. Pip6-PMO, A New Generation of Peptide-oligonucleotide Conjugates With Improved Cardiac Exon Skipping Activity for DMD Treatment. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids 1, e38 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H. et al. Pip5 transduction peptides direct high efficiency oligonucleotide-mediated dystrophin exon skipping in heart and phenotypic correction in mdx mice. Mol Ther 19, 1295–1303 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova G. D. et al. Improved cell-penetrating peptide-PNA conjugates for splicing redirection in HeLa cells and exon skipping in mdx mouse muscle. Nucleic Acids Res 36, 6418–6428 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costas J. M., Nye D. J., Henley J. B. & Plochocki J. H. Voluntary exercise induces structural remodeling in the hearts of dystrophin-deficient mice. Muscle Nerve 42, 881–885 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A., Yoshida K., Takeda S., Dohi N. & Ikeda S. Progression of dystrophic features and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and calcineurin by physical exercise, in hearts of mdx mice. FEBS letters 520, 18–24 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey D. J. et al. In vivo MRI Characterization of Progressive Cardiac Dysfunction in the mdx Mouse Model of Muscular Dystrophy. PLoS One 7, e28569 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter L. R., Yoder A. R., Flora D. R., Antos L. K. & Dickey D. M. Natriuretic peptides: their structures, receptors, physiologic functions and therapeutic applications. Handbook of experimental pharmacology 191, 341–366 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath M. F., de Bold M. L. & de Bold A. J. The endocrine function of the heart. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 16, 469–477 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Perino A., Ghigo A., Hirsch E. & Shah A. M. NADPH oxidases in heart failure: poachers or gamekeepers? Antioxidants & redox signaling 18, 1024–1041 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurney C. F. et al. Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy in mouse: expression of Nox4 and Lox are associated with fibrosis and altered functional parameters in the heart. Neuromuscul Disord 18, 371–381 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli G., Latronico M. V. & Cavarretta E. microRNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases: Current Knowledge and the Road Ahead. J Am Coll Cardiol 63, 2177–2187 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirak S. et al. Exon skipping and dystrophin restoration in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after systemic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer treatment: an open-label, phase 2, dose-escalation study. Lancet 378, 595–605 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk H. A. et al. In vivo comparison of 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate and morpholino antisense oligonucleotides for Duchenne muscular dystrophy exon skipping. J Gene Med 11, 257–266 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call J. A. et al. Endurance capacity in maturing mdx mice is markedly enhanced by combined voluntary wheel running and green tea extract. J Appl Physiol 105, 923–932 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyse G. M. et al. Long-term blinded placebo-controlled study of SNT-MC17/idebenone in the dystrophin deficient mdx mouse: cardiac protection and improved exercise performance. European heart journal 30, 116–124 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey D. J., Carr C. A., Tyler D. J. & Clarke K. Cine-MRI versus two-dimensional echocardiography to measure in vivo left ventricular function in rat heart. NMR Biomed 21 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies J. L. et al. Genetic predictors and remodeling of dilated cardiomyopathy in muscular dystrophy. Circulation 112, 2799–2804 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend D., Yasuda S., Li S., Chamberlain J. S. & Metzger J. M. Emergent dilated cardiomyopathy caused by targeted repair of dystrophic skeletal muscle. Mol Ther 16, 832–835 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S. K., Johnson W. W., Thapar M. K. & Pitner S. E. An ultrastructural basis for electrocardiographic alterations associated with Duchenne's progressive muscular dystrophy. Circulation 57, 1122–1129 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff J. K., Roberts W. C., de Leon A. C. Jr & O'Doherty D. The distinctive electrocardiogram of Duchenne's progressive muscular dystrophy. An electrocardiographic-pathologic correlative study. Am J Med 42, 179–188 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairallah M. et al. Metabolic and signaling alterations in dystrophin-deficient hearts precede overt cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43, 119–129 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burelle Y. et al. Alterations in mitochondrial function as a harbinger of cardiomyopathy: lessons from the dystrophic heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48, 310–321 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley M. D. & Wehrens X. H. Animal models of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Disease models & mechanisms 2, 563–570 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedicke-Hornung C. et al. Rescue of cardiomyopathy through U7snRNA-mediated exon skipping in Mybpc3-targeted knock-in mice. EMBO molecular medicine 5, 1128–1145 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arechavala-Gomeza V. et al. Immunohistological intensity measurements as a tool to assess sarcolemma-associated protein expression. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 36, 265–274 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T. C. et al. Extracellular microRNAs are dynamic non-vesicular biomarkers of muscle turnover. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 9500–9513 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T. C. et al. Expression Analysis in Multiple Muscle Groups and Serum Reveals Complexity in the MicroRNA Transcriptome of the mdx Mouse with Implications for Therapy. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids 1, e39 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1

Supplementary Video 2

Supplementary Video 3