Abstract

We systematically reviewed randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of people during imprisonment or in the year after release. We searched 14 biomedical and social science databases in 2014, and identified 95 studies.

Most studies involved only men or a majority of men (70/83 studies in which gender was specified); only 16 studies focused on adolescents. Most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 57). The risk of bias for outcomes in almost all studies was unclear or high (n = 91). In 59 studies, interventions led to improved mental health, substance use, infectious diseases, or health service utilization outcomes; in 42 of these studies, outcomes were measured in the community after release.

Improving the health of people who experience imprisonment requires knowledge generation and knowledge translation, including implementation of effective interventions.

Worldwide, more than 11 million people are imprisoned at any given time, and the prison population continues to grow at a rate faster than that of the general population.1 Substantial evidence reveals that people who have experienced imprisonment have poor health compared with the general population, as indicated by the prevalence of mental illness, infectious diseases, chronic diseases, and mortality.2

There are several reasons to focus on improving the health of people who experience imprisonment.3 The burden of disease in this population affects the general population directly through increased health care costs and through the transmission of communicable diseases (e.g., HIV, HCV, and tuberculosis) after people are released from detention. Imprisonment has also been associated with worse health in family members of those who are detained, compared with the general population, including chronic diseases4 and poor mental health5,6 in adult relatives and mortality in male children.7 At the community level, higher rates of incarceration have been associated with adverse health outcomes, such as sexually transmitted infections and teen pregnancies.8 There is also evidence that poor health in persons who are released from detention, particularly those with inadequately treated mental illness and substance use disorders,3 may affect public safety and reincarceration rates,3 and that better access to health care is associated with less recidivism.9,10 Finally, the right to health and health care is enshrined in international human rights documents,11,12 and is a legislated responsibility of governments in many countries.

Intervening during imprisonment and at the time of release could improve the health of people who experience imprisonment and public health overall.13 Knowledge translation efforts, such as syntheses of effective interventions, could lead to the implementation and further evaluation of interventions,14 and identify areas where further research is needed. To date, only syntheses with a limited focus have been conducted in this population, for example, reviews of interventions related to HIV15 or for persons with serious mental illness.16 Decision makers, practitioners, and researchers in this field would benefit from a broader understanding of the state of evidence regarding interventions to improve health in people who experience imprisonment.

To address this gap, we systematically reviewed randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve health in persons during imprisonment and in the year after release. We chose this population because we view imprisonment as a unique opportunity to deliver and to link with interventions for this population, and to highlight interventions that could be implemented by those responsible for the administration of correctional facilities. We limited this study to randomized controlled trials, recognizing that randomized controlled trials provide the highest quality of evidence compared with other study designs.17

METHODS

We defined a research protocol and registered it in PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews, under registration number CRD42014007074.18

Search Strategy

We searched Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Social Sciences Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, Criminal Justice Abstracts, ERIC, Proquest Criminal Justice, Proquest Dissertations and Theses, Web of Science, and Scopus (see Appendix A for search strategy as data available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org) in January 2014. We did not use any language or date restrictions, although we used only English language search terms. We included studies published in other languages. We searched clinical trials registries in June 2014. We reviewed reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews. We contacted investigators to ask about the results of trials or studies identified in the search if the results had not yet been published.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Population.

The population of interest was adults and adolescents who had been detained in a prison or jail, whether they were remanded or sentenced, either during detention or in the year after release into the community. We also included persons detained in compulsory rehabilitation centers. Throughout this article, we refer to the period of detention as imprisonment. We included studies that included other populations if the studies presented stratified results for persons who met this population criterion.

Interventions.

We included all randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of people during imprisonment and in the year after release, with randomization at the individual or cluster level. We excluded studies that used a nonrandom component in the assignment of study group (e.g., that used a sequence generated by date of birth or date of admission).19 We excluded studies that were not focused in particular on improving the health of this population.

Outcomes.

We included studies that measured health outcomes,19 including mortality, clinical events, patient-reported outcomes (e.g., quality of life and symptoms), adverse events, health care utilization, and health-related economic outcomes. For feasibility reasons, we did not include outcomes such as housing, employment, and reincarceration, although we acknowledge that these factors affect and reflect health.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Any disagreements in reviewers’ decisions were resolved by discussion. Two reviewers independently reviewed each article to assess eligibility, and for eligible studies, to extract relevant data and assess risk of bias. Any disagreements regarding eligibility of full articles, extracted data, and risk of bias were resolved by discussion. We used a data extraction form, which we piloted and modified. We extracted data on study context, populations, design, intervention and comparator groups, period of follow-up, outcomes, results, and funding sources.

We categorized studies based on primary outcome into the following groups: substance abuse, mental health, infectious diseases, chronic diseases, and health service use. We extracted information on the statistical significance of comparisons, where available, as evidence of the effectiveness of interventions. We defined a P value of less than .05 as the cutoff for statistical significance, or the author’s indication of statistical significance if the P value was not specified.

Quality Appraisal

We assessed bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool,19 which is a domain-based evaluation, and assessed for bias in the domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. We classified the risk of bias for each outcome in each study as low, high, or unclear in each domain. We classified outcomes for each study as at low risk of bias overall if the risk of bias was low across all domains, high risk of bias if the risk of bias was high in any domain, and otherwise unclear risk of bias.19

Synthesis

We decided a priori not to undertake a quantitative synthesis of results, because we did not expect to identify multiple studies that assessed the effects of the same intervention on a given outcome.

RESULTS

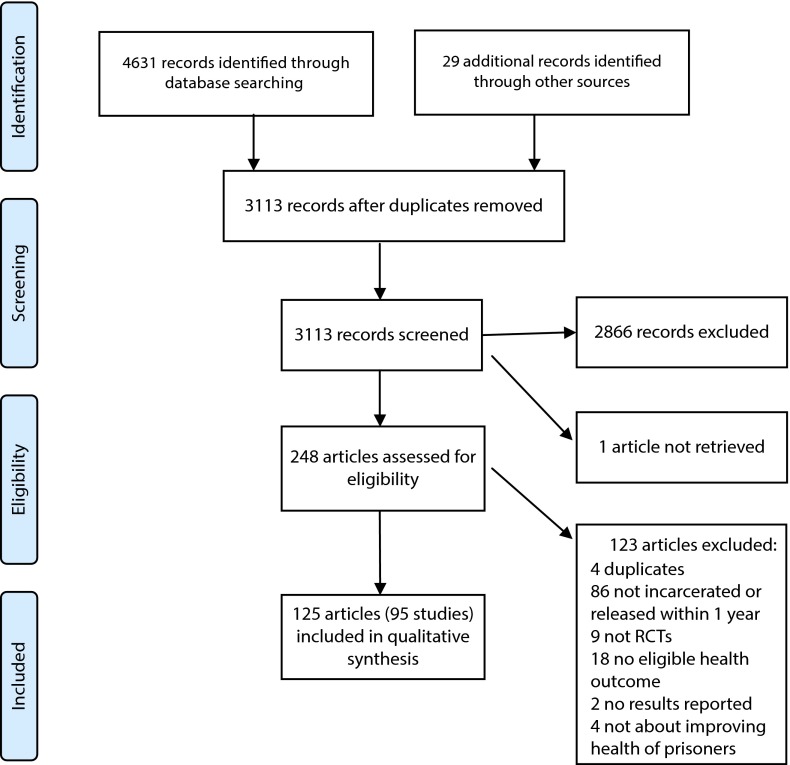

As shown in Figure 1, we identified 4631 records through database searches and an additional 29 through other sources. After eliminating duplicates, there were 3113 records for review, of which 248 met the criteria for full review. We were unable to retrieve 1 article.21 On full review, 125 articles were eligible for inclusion. Twenty-eight of these 125 articles were published abstracts, and 1 was the abstract of the full article that we were not able to retrieve. These 125 articles represented 95 unique studies.

FIGURE 1—

Flow diagram of studies included in this systematic review: 2014.

Note. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Source. Moher et al.20

Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Fifty-seven studies were conducted in the United States, 12 in the United Kingdom, 5 in Australia, 5 in Sweden, 3 in Iran, 2 in each of Canada, China, and Italy, and 1 in each of Denmark, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and Taiwan. Thirty-six studies included only men, and 13 studies included only women. Of the remaining 46 studies, the gender distribution of participants was not specified for 12 studies, and in the other 34 studies, more than half of participants were men. Sixteen studies focused on adolescents. The intervention was implemented during imprisonment for 63 studies, in the community after release for 13 studies, and spanning imprisonment and release for 19 studies.

TABLE 1—

Studies Included (n = 95) in a Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials to Improve the Health of Persons During Imprisonment or After Release, by Geographical Region: 2014

| Study | Dates | Location | Intervention Setting | No.a | Participant’s Age, Years, Mean (Range) or Mean ±SD (Range) | % Male | Population |

| Asia | |||||||

| Bahari et al. 201122 | 2009 | Zahedan City, Iran | Prison | 100 | Not specified | Not specified | General population |

| Chan et al. 201223 | 2008–2009 | Northern Taiwan | Prison | 373 | ≥ 18 | 100 | Adult men with latent tuberculosis infection |

| X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014 | 2012–2013 | China | Prison | 200 | 35.5 (18–57) | 100 | Adult men with anxiety or depression |

| Hser et al. 201324 | 2009–2010 | Shanghai, China | Community | 100 | 38.7 ±11.2 | 77 | Persons with heroin dependence |

| Khodayarifard et al. 201025 | Not specified | Tehran Province, Iran | Prison | 180 | 48.23 | 100 | Men |

| Nakaya et al. 200426 | Not specified | Fukuoka, Japan | Juvenile reformatory | 16 | 14–20 | 100 | Adolescent boys |

| Zolghadr Asli et al. 201127,28 | 2006–2007 | Shiraz, Iran | Prisons and correctional facilities | 161 | 34 ±9.37 | 100 | Men |

| Australia and New Zealand | |||||||

| Brown et al. 198029 | Not specified | New Zealand | Periodic detention | 60 | 31.95 | 100 | Adult men convicted of drunken driving |

| Cashin et al. 200830,31 | Not specified | New South Wales, Australia | Correctional facility | 20 | 51.1 | 100 | Men with chronic illness, risk factors for chronic illness, or aged ≥ 40 y |

| Dolan et al. 200332 and Warren et al. 200633 | 1997–1998 | Australia | Prison | 253 | 27 ±6 | 100 | Men with a heroin problem seeking drug treatment |

| Jones 201134 and 201335 | 2010–2011 | Sydney, Australia | Community | 136 | 32.4 | 83.8 | Persons participating in drug court |

| Kinner et al. 201336 and S.A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014 | 2008–2011 | Queensland, Australia | Prisons and community | 1325 | 32.7 ±11.1 | 79 | Adults |

| Richmond et al. 201237 | 2006–2009 | New South Wales and Queensland, Australia | Prisons | 425 | 33.5 | 100 | Adult men with nicotine dependence |

| Europe | |||||||

| Andersson et al. 201338 and 201439 | 2009–2010 | Sweden | Community | 108 | 36.2 (18–61) | 97.2 | Adults on parole |

| Battaglia et al. 201340 | Not specified | Larino, Italy | Prison | 58 | 32.3 | 100 | Adult men |

| Berman et al. 200121 and 200441 | 1997–1998 | Sweden | Prisons | 158 | 33.5 | 61 | Persons who use drugs |

| Biele et al. 200642 | 2003–2004 | Italy | National jails | 240 | 31 ±10 | 100 | Men with scabies infection |

| Biggam and Power 200243 | Not specified | Scotland | Youth facility | 46 | 19.3 ±1.3 (16–21) | Not specified | Adolescents at risk for suicide, under formal protection, or who were bullied |

| Bilderbeck et al. 201344 | Not specified | West Midlands, United Kingdom | Prisons | 100 | 36.08 ±12.14 (21–68) | 92.8 | Adults |

| Christensen et al. 200445 | 2000–2001 | Copenhagen, Denmark | Prisons | 34 | Not specified | Not specified | Persons who inject drugs |

| Craine et al. 201446 | 2011–2012 | United Kingdom | Prisons | 5 Prisons | Not specified | Not specified | General population |

| Cullen et al. 201247 | 2003–2008 | United Kingdom | Forensic hospitals | 84 | 35.4 | 100 | Men with a psychotic disorder and a history of violence |

| Forsberg et al. 201148 | 2004–2007 | Sweden | Prisons | 114 | 20–50 | Not specified | Adults who use heroin, cocaine, or amphetamines, or inject drugs |

| Frommann 201049 | 2005–2009 | Hessen, Germany | Forensic psychiatry hospital | 24 | Not specified | 100 | Men with schizophrenia |

| Ginsberg et al. 2012,50 Ginsberg,51 Ginsberg et al. 2013,52 and Grann et al. 201353 | 2007–2010 | Sweden | Prison | 30 | 34.4 ±10.67, (21–61) | 100 | Adult men with ADHD |

| Hickman et al. 200854 | 2004–2005 | England and Wales, United Kingdom | Prisons | 6 Prisons | Not specified | 100 | Men who inject drugs |

| Howells et al. 200255 | Not specified | Southern England, United Kingdom | Prisons | 68 | 30.2 (22–49) | 100 | Adult men with opioid dependence and opioid-induced withdrawal |

| Jarrett et al. 201256 | 2007–2008 | England, United Kingdom | Prison and community | 60 | 36.3 | Not specified | Persons with severe mental illness |

| Konstenius et al. 201357–59 | 2007–2011 | Stockholm County, Sweden | Prisons and community | 54 | 42 (18–65) | 100 | Adult men with ADHD and amphetamine dependence |

| Lobmaier et al. 201060,61 | Not specified | Norway | Prisons | 44 | 35.1 ±7.0 | 93.5 | Persons with heroin dependence |

| Maunder et al. 200962 | Not specified | North of England, United Kingdom | Prison | 38 | 35.22 ±11.45 | 100 | Adult men with symptoms of anxiety |

| Sheard et al. 200963 | 2004–2005 | North of England, United Kingdom | Prison | 90 | 29.3 (18–65) | 100 | Adult men using illicit opioids |

| Sleed et al. 201364 | Not specified | United Kingdom | Prisons | 163 mother-baby dyads | 26.8 (18–42) | 0 | Adult women with babies younger than 18 mo |

| Tyrer et al. 200965 | 2002–2004 | England, United Kingdom | Prisons | 70 | Not specified | Not specified | Persons with a dangerous and severe personality disorder |

| Villagra Lanza and Menéndez, 201366 | 2009–2012 | Asturias, Spain | State prison | 27 | 32 ±6.2 (21–46) | 0 | Adult women with substance use disorders |

| Wright et al. 201167 | 2006–2009 | North of England, United Kingdom | Remand prisons | 213 | Median = 30.8, IQR = 26.9–34.9 (21–65) | Both | Adults using illicit opioids |

| North America | |||||||

| Ahrens and Rexford 200268 | Not specified | Kansas, USA | Youth facility | 38 | 16.4 (15–18) | 100 | Adolescent boys with PTSD |

| Bradley and Follingstad 200369 | Not specified | Southeastern state, USA | Prison | 24 | 36.67 ±8.27 (34–54) | 0 | Adult women with a history of childhood abuse |

| Braithwaite et al. 200570 | 2000–2001 | Georgia, USA | Correctional institutions, transitional center | 116 | 35.3 ±8.87 (19–59) | 100 | Adult men |

| Bryan et al. 200971 and Schmiege et al. 200972 and 201173 | 2004–2006 | Colorado, USA | Juvenile detention facilities | 484 | 15.8 ±1.1 | 82.7 | Adolescents |

| Chandler and Spicer 200674 | 2001–2004 | California, USA | In-custody treatment unit and community | 182 | 18–78 | 71.8 | Adults with multiple admissions to detention and dual disorders |

| Clair et al. 201375 | 2001–2006 | Northeastern USA | Juvenile correctional facility | 147 | 17.12 ±1.10 (14–19) | 85.7 | Adolescents with past year substance use |

| Clarke et al. 201376 | Not specified | Northeastern USA | State Correctional facility | 247 | 35.6 | 65 | Adults who smoked before incarceration |

| Cosden et al. 200377 | Not specified | California, USA | Community | 235 | Not specified | 50.2 | Persons with serious and pervasive mental illness |

| Cusack et al. 201078 | 2000–2003 | California, USA | Community | 134 | 37 ±10 | 59 | Persons with a major mental disorder |

| Davis et al. 200379 | Not specified | USA | County jail system | 73 | 45.7 ±7.7 | 97.3 | Veterans with substance use disorders |

| Davis 201180 | 2009–2010 | North Carolina, USA | Community | 40 | 29 ±10.3 | 100 | Adult men with substance use disorders |

| Kamath et al. 201181 and Ehret et al. 201382 | 2007–2009 | Connecticut, USA | State correctional facility | 60 | 32.7 (18–48) | 0 | Adult women with bipolar type I or II |

| Eibner et al. 200683 and MacDonald et al. 200784 | 2000–2002 | California, USA | Jail and community | 236 | 35.1 | Not specified | Adults incarcerated for the second or third time for driving under the influence |

| El-Bassel et al. 199585 | Not specified | New York City, New York, USA | Jail | 145 | 18–55 | 0 | Adult women with a significant drug abuse history |

| Ford et al. 201386 | 2009–2010 | Connecticut, USA | State prison | 72 | 36.2 | 0 | Adult women with PTSD related to interpersonal victimization |

| Freudenberg et al. 201087 | 2003–2007 | New York, USA | Jail and community | 397 | 17.99 ±0.71 (16–18) | 100 | Adolescent boys |

| Friedmann et al. 201288 and Johnson et al. 201189 | 2005–2008 | USA | Parole offices | 569 | 34 | 83 | Adults with drug dependence |

| Gleser et al. 196590 | Not specified | USA | Juvenile detention center | 46 | 14–16 | 100 | Adolescent boys |

| Goldberg et al. 200991 | 2000–2003 | Ontario, Canada | Young offender custody facilities | 391 | 16.0 ±1.1 (12–18) | 73.7 | Adolescents |

| Gordon et al. 200797 and 2008,98 Kinlock et al. 200799 and 2009,100 and Wilson et al. 2012101 | 2003–2005 | Maryland, USA | Prerelease prison and community | 204 | 40.3 ±7.1 | 100 | Men with heroin dependence |

| Gottschalk et al. 197392 | Not specified | Maryland, USA | Treatment center | 42 | 25.36 ±6.15 | 100 | Men with a history of violating institutional discipline rules |

| Grommon et al. 201393 | Not specified | USA | Community | 511 | 34.68 ±9.00 | 100 | Men with substance dependence |

| Harrell et al. 200094 | 1994–1997 | Washington, D.C., USA | Community | 1022 | Median = 30–33 across groups | 85–89 across groups | Persons arrested on a felony drug charge |

| Johnson 201195 and 201296 | 2006–2009 | Rhode Island, USA | State prison and community | 38 | 35.0 ±9.2 | 0 | Women with depression and substance use disorder |

| Knudsen et al. 2014102 | 2007–2008 | USA | Prisons and community | 444 | 35.2 ± 9.1 | 0 | Women with weekly substance use before incarceration |

| Lee et al. 2014103 | 2010–2013 | New York, USA | Jail and community | 34 | 43.6 (26–58) | 100 | Adult men with opioid dependence |

| Awgu et al. 2010,104 Magura et al. 2009,105 and Lee et al. 2009106 | 2006–2007 | New York, USA | Jail | 116 | 39.5 | 100 | Men with heroin dependence |

| Martin et al. 2008107 and O'Connell et al. 2007108 | 2006–2008 | USA | Prison/jail | 343 | 33.9 ± 9.83 (19–68) | 85.7 | Adults |

| Martin et al. 2011109 | Not specified | USA | Not specified | 106 | Teens | Not specified | Adolescents who abuse substances |

| McKenzie et al. 2012110 | 2006–2009 | Rhode Island, USA | Prison and community | 60 | 40.7 | Not specified | Adults with a history of injection drug use and heroin dependence |

| Needels et al. 2005111 | 1997–2000 | New York, USA | Jail and community | 50 | Men: 17.3 16–18 women: 34.7 | 50.1 | Adolescent boys and adult women |

| Prendergast et al. 2011112 | 2004–2011 | USA | Correctional facilities and community | 812 | 33.6 | 76.0 | Substance-abusing adults on parole |

| Reznick et al. 2013113 | Not specified | California, USA | Prison and jail | 151 | 42 | 89.4 | Adults infected with HIV |

| Richards et al. 2000114 | Not specified | Midwestern USA | Psychiatric prison | 98 | 34.5 ±8.9 | 100 | Men with at least 1 DSM-III R disorder |

| Begun et al. 2010115 and Rose et al. 2013116 | Not specified | USA | Jail | 149 | Not specified | 0 | Women with alcohol or other drug abuse |

| Rosengard et al. 2007117 | 2001–2003 | Northeast USA | State juvenile correctional facility | 114 | 14–19 | 89.5 | Adolescents with past year alcohol or marijuana use |

| Saber-Tehrani et al. 2012118 and F. Altice, unpublished data, March 2014 | 2004–2009 | Connecticut, USA | Community | 154 | 45.6 | 81.3 | Adults infected with HIV on antiretroviral therapy |

| Sacks et al. 2012119 | 2002–2006 | Denver, Colorado, USA | Correctional facility | 427 | 35.1 | 0 | Women with substance use disorders |

| Savage and McCabe 1973120 | Not specified | Maryland, USA | Community | 78 | 21–50 | 100 | Adult men with a history of long-term heroin abuse on parole |

| Shelton et al. 2009121 | 2004–2006 | Connecticut, USA | Correctional facilities | 63 | 28 ±10.29 | 71.4 | Persons with impulsive behavior problems |

| Shivrattan 1988122 | Not specified | Ontario, Canada | Youth prison | 41 | (15–17) | 100 | Adolescent boys |

| Skipper et al. 1974123 | Not specified | Ohio, USA | Correctional institution | 119 | Not specified | 100 | Men with a history of alcohol abuse |

| Draine124 and Solomon and Draine 1995125 | Not specified | USA | Community | 94 | 35.2 ±9.4 | 84 | Persons with serious mental illness who are homeless |

| St. Lawrence et al. 1999126 | Not specified | Southern USA | State reformatory | 312 | 15.8 ±0.7 | 100 | Adolescent boys |

| Stein et al. 2006127 | Not specified | Northeast USA | State juvenile correctional facility | 105 | 17.06 ±1.08 | 89.5 | Adolescents with recent substance use |

| Clarke et al. 2011128 and Stein et al. 2010129 | 2004–2007 | Rhode Island, USA | Combined prison/jail | 210 | 34.1 ±8.9 | 0 | Women with risky sexual behavior and hazardous alcohol consumption |

| Stein et al. 2011130,131 | Not specified | Northeast USA | State juvenile correctional facility | 162 | 17.10 ±1.11 | 84 | Adolescents with recent substance use |

| Steiner et al. 2003132 | Not specified | California, USA | Youth facility | 58 | 15.9 ±1.1 (14–18) | 100 | Adolescent boys with conduct disorder |

| Sullivan et al. 2007133 | Not specified | Colorado, USA | Prison and community | 139 | 34.3 ±8.8 | 100 | Men with mental illness and substance abuse disorders |

| Valentine and Smith 2001134 | Not specified | Florida, USA | Federal prison | 123 | 23.9 | 0 | Women with a history of interpersonal violence |

| Wang et al. 2012135 and 2011136 | 2007–2010 | USA | Community | 200 | 43.2 | 93 | Persons with a chronic medical condition or older than 50 |

| Wheeler et al. 2004137 | Not specified | New Mexico, USA | Jail | 94 | ≥ 18 | 66.7 | Adults with first time driving while intoxicated convictions |

| White et al. 1998138 | 1996 | California, USA | Jail and community | 79 | 33 | 98.7 | Persons with latent tuberculosis infection |

| White et al. 2002139 | 1998–1999 | California, USA | Jail and community | 325 | Median = 28.5–29.7 across groups | 82.2 | Persons with latent tuberculosis infection |

| White et al. 2012140 | 2004–2007 | California, USA | Jail and community | 364 | 71% < 35 and 29% ≥ 35 | 93 | Persons with latent tuberculosis infection |

| Wilson 1990141 | Not specified | USA | Prison | 10 | 33.1 ±8.0 | Not specified | Persons with depression |

| Wohl et al. 2011142 | Not specified | North Carolina, USA | State prison system and community | 89 | ≥ 18 | 73 | Adults with HIV infection |

| Woodall et al. 2007143 | 2000–2003 | New Mexico, USA | Detention facility | 305 | 27.1 ±8.7 | 86.9 | Persons with first time driving while intoxicated convictions |

| Zlotnick et al. 2009144 | Not specified | USA | Prison | 44 | 34.6 ±7.4 | 0 | Women with substance dependence and PTSD |

Note. ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; DSM = Diagnostic Statistical Manual; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

If authors reported both number randomized and number included in analysis, we specified the number included in analysis.

Outcomes were measured in prison only in 30 studies, in the community after release only for 61 studies, and in both prison and the community for 4 studies, with follow-up periods as long as 2 years after release93 or from the start of the intervention.78,83,84 Thirty-five studies focused on substance abuse, 28 on mental health, 18 on infectious diseases, 12 on health service use, and 2 on chronic diseases, although some of these studies also reported outcomes in other categories. Details regarding interventions, outcomes, and results are provided as data available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org, categorized by the main outcome of interest. In the subsequent text, data are presented for all interventions categorized by the main outcome of interest, and further grouped by the type of intervention, population of interest, or intervention site. Within each group of studies, studies are ordered based on whether a statistically significant result was found, with those with only positive findings listed first, those with some positive and some null findings listed second, and those with only null findings listed third, if applicable.

Fifty-nine interventions had a positive impact on 1 or more health outcomes relative to a comparator group (Table 2). Outcomes were measured in the community after release in 42 of these studies. In 3 of these studies, outcomes were significantly worse for a primary outcome in the intervention group compared with a comparator group, in contrast to the study hypothesis.41,109,113

TABLE 2—

An Overview of Randomized Interventions That Improved One or More Health Outcomes in People During Imprisonment or at the Time of Release, by Population Group (n = 59): 2014

| Population Groupa | Intervention and Comparator Groups | Outcomes Impacted |

| General (n = 12) | ||

| General population | Accelerated double dose hepatitis B vaccination schedule vs standard vaccination schedule22 | Infectious diseases |

| Men | Individual and group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) vs individual CBT25 | Mental health |

| Individual and group CBT vs no intervention25 | Mental health | |

| Individual CBT vs no intervention25 | Mental health | |

| Accelerated hepatitis B vaccination schedule vs standard vaccination schedule27,28 | Infectious diseases | |

| Adults | Yoga vs no intervention44 | Mental health |

| Personalized health status and information booklet on release plus weekly contacts postrelease vs usual care36 (S. A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014) | Health service utilization | |

| DVD-based peer delivered intervention vs HIV educational video107,108 | Infectious diseases | |

| Adults on parole | Daily automated telephone assessment and feedback postrelease vs daily automated telephone assessment38,39 | Substance abuse, Mental health |

| Adult men | HIV-positive peer-delivered presentations on HIV and substance abuse vs facilitator-delivered presentations on HIV and substance abuse, HIV-negative peer-delivered presentations on HIV and substance abuse, or health promotion and disease prevention videos70 | Substance abuse |

| Adolescents | Sexual risk reduction intervention plus alcohol risk reduction motivational enhancement therapy vs information only71–73 | Infectious diseases |

| Adolescent boys | Jail and community-based intervention and referral to community-based organization vs jail-based discharge planning and referral to community-based organization87 | Substance abuse |

| Chlordiazepoxide vs placebo90 | Mental health | |

| Adolescent girls | HIV education intervention with booster vs no intervention91 | Infectious diseases |

| Persons with mental disorders (n = 9) | ||

| Persons with severe mental illness | Critical Time Intervention before release and support after release vs treatment as usual before release56 | Mental health, health service utilization |

| Persons with serious and pervasive mental illness | Mental health treatment court with assertive community treatment (ACT) case management vs treatment as usual77 | Mental health, substance abuse |

| Persons with a major mental disorder | Forensic ACT vs treatment as usual78 | Health service utilization |

| Adult men with anxiety or depression | Group music therapy vs standard care (X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014) | Mental health |

| Adult men with anxiety | Self-help booklet based on CBT principles vs waitlist control62 | Mental health |

| Adult men with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | Osmotic release methylphenidate treatment vs placebo50–53 | Mental health |

| Adult women with bipolar type I or II | Texas Implementation of medication algorithm for bipolar disease vs treatment as usual81,82 | Mental health |

| Adolescent boys with posttraumatic stress disorder | Short-term cognitive processing therapy vs no intervention68 | Mental health |

| Adolescent boys with conduct disorder | High-dose valproic acid vs low dose valproic acid132 | Mental health |

| Persons with substance use disorders or substance use histories (n = 24) | ||

| Persons convicted of driving while intoxicated | Treatment program incorporating motivational interviewing (MI) and detention vs detention143 | Substance abuse |

| Persons arrested on a felony drug charge | Court sanctions docket vs standard docket94 | Substance abuse |

| Court treatment docket vs court standard docket94 | Substance abuse | |

| Persons who abuse substances | Nonspecific auricular acupuncture vs NADA-Acudetox auricular acupuncture21,41 | Substance abuse |

| Persons who inject drugs | Accelerated hepatitis B vaccination plus booster vs standard hepatitis B vaccination plus booster45 | Infectious diseases |

| Persons participating in drug court | Intensive judicial supervision in a drug court with frequent drug testing and pharmacological treatment of heroin dependence vs supervision as usual34,35 | Substance abuse |

| Persons with heroin dependence | Naltrexone implants vs methadone60,61 | Substance abuse |

| Men with a heroin problem | Methadone vs waitlist32,33 | Substance abuse, infectious diseases |

| Men with heroin dependence | Counseling and methadone initiation in prison vs counseling in prison and transfer to methadone treatment on release97–101 | Substance abuse, Infectious diseases |

| Counseling and methadone initiation in prison vs counseling in prison97–101 | ||

| Counseling in prison and transfer to methadone treatment on release vs counseling in prison97–101 | ||

| Buprenorphine vs methadone104–106 | Substance abuse | |

| Men with substance dependence | Multimodal community-based reentry program vs traditional prerelease and community supervision plans93 | Substance abuse |

| Women with substance use disorders | Prison therapeutic program vs intensive cognitive-behavioral outpatient program119 | Substance abuse, mental health |

| Women with substance abuse | Motivational interviewing (MI) vs treatment as usual115,116 | Substance abuse |

| Adults with a history of injection drug use and heroin dependence | Methadone initiation in prison and short-term payment of treatment costs on release vs referral to methadone program on release110 | Substance abuse |

| Methadone initiation in prison and short-term payment of treatment costs on release vs referral to methadone program on release110 | Substance abuse | |

| Adults who smoked before incarceration | Smoking cessation sessions incorporating MI and CBT vs health education videos76 | Substance abuse |

| Adults with drug dependence | Collaborative behavioral management during parole vs standard parole88,89 | Substance abuse |

| Adults incarcerated for the second or third time for driving under the influence of alcohol | Therapeutic driving-under-the-influence court intervention vs standard sentence and conditions83,84 | Substance abuse |

| Adult men convicted of driving under the influence of alcohol | Conventional drunken driver education course vs education course on controlled drinking or no education29 | Substance abuse |

| Adult men with a history of chronic heroin abuse on parole | Psychedelic therapy with LSD during residency in halfway house vs outpatient clinic program with psychotherapy120 | Substance abuse |

| Adult men using illicit opioids | Buprenorphine vs dihydrocodeine63 | Substance abuse |

| Adult men with opioid dependence | Extended-release naltrexone and MI vs MI103 | Substance abuse |

| Adult women with substance use disorders | Acceptance and commitment therapy vs waitlist66 | Substance abuse |

| Adolescents who abuse substances | Relaxation training, plus group substance education training vs MI session plus group CBT109 | Infectious diseases |

| Adolescents with recent substance use | MI vs relaxation training130,131 | Substance abuse |

| Relaxation training vs MI127 | Substance abuse | |

| Persons with dual disorders (n = 3) | ||

| Men with mental illness and substance abuse disorders | Prison modified therapeutic community vs routine mental health treatment133 | Substance abuse |

| Adults with dual disorders and multiple admissions to detention | In custody treatment unit then integrated dual disorders treatment vs in custody treatment unit then service as usual74 | Health service utilization |

| Adult men with ADHD and amphetamine dependence | Osmotic release methylphenidate and CBT vs placebo and CBT57–59 | Mental health, Substance abuse |

| Persons with infectious diseases (n = 6) | ||

| Persons with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) | 4-mo rifampicin course vs 9-mo isoniazid course140 | Infectious diseases |

| Tuberculosis education vs usual care139 | Health service utilization, infectious diseases | |

| Incentive to go to tuberculosis clinic vs usual care139 | Health service utilization | |

| Adults infected with HIV | Ecosystem intervention vs individually focused intervention113 | Infectious diseases |

| Adults infected with HIV on antiretroviral therapy | Directly administered antiretroviral therapy vs self-administered ART118 (F. Altice, unpublished data, March 2014) | Infectious diseases |

| Adult men with LTBI | 4-mo rifampicin course vs 6-mo isoniazid course23 | Infectious diseases |

| Men with scabies infection | Synergized pyrethrins foam vs benzyl benzoate42 | Infectious diseases |

| Benzyl benzoate vs synergized pyrethrins foam42 | Infectious diseases | |

| Other (n = 5) | ||

| Persons with impulsive behavior problems | DBT group sessions and individual coaching vs DBT group sessions and weekly case management121 | Mental health |

| Persons with a chronic medical condition or older than 50 y | Primary care-based complex care management program vs expedited primary care at another clinic135,136 | Health service utilization |

| Adult women with a history of childhood abuse | Group trauma treatment therapy vs control69 | Mental health |

| Adult women with a history of interpersonal violence | Traumatic incident reduction therapy vs waitlist134 | Mental health |

| Adolescents at risk for suicide, under formal protection, or who were bullied | Social problem-solving therapy vs no intervention43 | Mental health |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; DBT = dialectical behavior therapy; NADA = National Acupuncture Detoxification Association.

Arranged by age and gender groups within each category. For studies in which either gender or age distribution was not specified, we assumed that both adolescents and adults and men and women, respectively, were included.

Substance Abuse

Motivational interviewing during imprisonment.

Eight studies assessed the impact of motivational interviewing,48,75,76,115,116,127–131,143 and of these, 5 produced a positive result.76,115,116,127,130,131,143 In adolescents with recent substance use, motivational interviewing was effective compared with relaxation training in reducing alcohol and marijuana use130,131 and driving under the influence of alcohol,127 but it did not reduce the frequency of driving under the influence of marijuana or being a passenger with a driver under the influence or alcohol or marijuana.127 Motivational interviewing reduced drug use compared with treatment as usual in women with alcohol and drug abuse histories.115,116 In adults who smoked before imprisonment, a 6-week smoking cessation intervention involving motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy led to lower smoking rates compared with health education videos.76 In persons convicted for the first time of driving under the influence of alcohol, a treatment program that incorporated motivational interviewing added to detention led to less alcohol use 2 years after release from custody, compared with detention alone.143

By contrast with these studies, motivational interviewing did not improve outcomes in 3 studies.48,75,128,129 In another study of adolescents with past year substance use, there was no difference in alcohol use between those randomized to motivational interviewing or relaxation therapy.75 In women with a history of risky sexual behavior and hazardous alcohol use, there was no difference in most indicators of alcohol use between those randomized to motivational interviewing and a control group, and no difference in entry to alcohol treatment programs.128,129 Adults who used drugs who were randomized to motivational interviewing delivered by workshop-trained correctional staff had the same drug and alcohol use as those adults randomized to the same intervention with additional supervision and coaching for the staff, and as those randomized to the control group.48

Psychotherapy.

Three studies found positive effects of psychotherapeutic interventions on substance use.66,119,133 In men with mental illness and substance abuse disorders, randomization to a 1-year modified therapeutic community in prison with the option to continue treatment of 6 months after release was associated with less alcohol and drug use at 1 year after release compared with routine care.133 A 6-month prison therapeutic program led to greater improvements in drug use in women with substance use disorders, overall symptom severity, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but not in depression compared with an intensive outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention.119 In adult women with a substance use disorder, acceptance and commitment therapy were associated with less drug and alcohol use, but there were no other differences in mental health compared with a waitlist control group.66

Educational and skills building programs during imprisonment.

Four studies examined educational and skills building programs during imprisonment,29,47,70,137 2 of which led to less substance use.29,70 In adult men, presentations on HIV and substance abuse delivered by an HIV-positive peer facilitator resulted in less drug and alcohol use than did presentations delivered by a nonpeer facilitator or an HIV-negative peer facilitator, or than health promotion and disease prevention videos.70 In adult men convicted of driving under the influence of alcohol who were attending periodic detention, an education course that focused on practical strategies to modify alcohol use was associated with fewer uncontrolled drinking days compared with no course, whereas a conventional didactic drunken driver education course did not affect drinking.29 A study of men with a psychotic disorder and history of violence found no effect on alcohol or drug use from a cognitive skills program compared with treatment as usual.47 In adults with a first conviction of drinking under the influence of alcohol, the addition of a victim panel did not improve alcohol use or alcohol-associated risk behaviors compared with the standard educational program.137

Pharmacological interventions.

Six studies assessed long-term opioid agonist or antagonist treatment in persons with opioid dependence, all of which found a positive impact on at least 1 of the substance use and treatment outcomes assessed.32,33,60,61,97–101,103–106,110 Extended-release naltrexone administered before release added to motivational interviewing led to less opioid use at 2 months.103 In men with heroin dependence, initiation of methadone in prison, in addition to counseling in prison, resulted in less opioid and cocaine use and fewer injection risk behaviors after release. Transfer to a methadone treatment program on release in addition to counseling in prison was associated with some decrease in sexual and drug use risk behaviors.97–101 A prison methadone program led to no difference in opioid use or incident HIV or HCV infection compared with a waitlist in men with a heroin problem, but did lead to less drug injection and syringe sharing.32,33 Initiation of methadone in prison with continuation of treatment on release with short-term payment of costs led to less heroin use and higher rates of methadone use at 6 months postrelease compared with referral to a methadone program at the time of release (with or without short-term payment of treatment costs). However, this was not associated with any difference in use of other drugs or in injecting drugs.110 There was no difference in heroin use at 6 months after release between persons randomized to naltrexone implants or methadone, although more people in the naltrexone group continued treatment.60,61 Men treated with buprenorphine or methadone had similar rates of opioid use at 3 months after release, but those who received buprenorphine were more likely to access their assigned treatment postrelease, and those who received methadone reported more side effects.104–106

Three studies assessed short-term opioid detoxification treatment during imprisonment,55,63,67 only 1 of which had a positive finding.63 In adult men who were randomized to buprenorphine or dihydrocodeine for up to 20 days, rates of opioid use were lower at 5 days postdetox for those treated with buprenorphine, but these rates were similar between groups at 6 months.63 Buprenorphine also had similar effects in adults compared with methadone on opioid use at 6 months.67 There was no difference between 10-day lofexidine treatment in prison compared with methadone treatment in terms of withdrawal symptoms in adult men with opioid dependence.55

Two studies assessed other pharmacological interventions,37,120 1 of which decreased substance use.120 Adult men on parole with a history of long-term heroin abuse who were randomized to psychedelic therapy with LSD and living in a residential halfway house had a higher rate of opioid abstinence at 1 year compared with those who underwent psychotherapy in an outpatient clinic program.120 Nortriptyline therapy added to cognitive-behavioral therapy and nicotine patches did not affect smoking in men at 1 year.37

Court-based interventions.

Three studies assessed court-based interventions,34,35,83,84,94 all of which resulted in some positive findings.34,35,83,84,94 Intensive judicial supervision in a drug court with frequent drug testing and pharmacological treatment of heroin dependence led to less drug use than supervision as usual at 4–5 months.34,35 Persons with a felony drug charge who were randomized to either a sanctions group with graduated sanctions for failed compulsory drug tests or to a treatment group that aimed to provide persons with skills and resources had less drug use than those randomized to standard handling in the pretrial release period, but this effect was not sustained in the year after sentencing.94 A therapeutic driving under the influence (DUI) court intervention did not decrease alcohol use or adverse consequences of alcohol use, but was associated with overall cost savings from societal and criminal justice perspectives.83,84

Services after release.

Six studies assessed interventions that enhanced support after release,24,80,87–89,93,111 3 of which had a positive impact on some substance abuse outcomes.87–89,93 An intensive intervention for adolescent boys involving educational sessions and case management delivered before and after release led to lower rates of substance dependence and use of drugs (other than marijuana) than did routine discharge planning and referral to a community service. However, daily marijuana use and sexual risk behaviors were not affected.87 For persons on parole with a history of drug dependence, a collaborative behavioral management intervention involving the parole officer, treatment counselor, and person on parole resulted in fewer months of use of the primary drug and of alcohol, and a lower rate of use of any alcohol after release, but there was no difference in the rate of any use of the primary drug or the number of episodes of heavy drinking.88,89 A community-based reentry program that prioritized substance abuse treatment led to a lower frequency of drug use and longer time to drug use compared with treatment as usual in men with substance dependence, but this program did not affect any drug use.93 A release program for persons with a history of heroin dependence to detect relapse and links to methadone maintenance (if needed) did not affect alcohol or drug use, mental health status, or HIV risk behaviors.24 A cognitive-behavioral social support intervention provided after release to adult men with substance use disorders and their chosen support person had no effect on alcohol or drug use compared with treatment as usual.80 Intensive discharge planning and community-based case management in adolescent boys and adult women did not affect drug use, drug consequences, or risk behaviors compared with less intensive discharge planning.111

Mental Health Interventions

Psychotherapy during imprisonment.

Six studies of various psychotherapies identified differences in mental health between randomized groups during imprisonment.25,43,68,69,121,134 Participants in 4 interventions experienced less anxiety and depression relative to those in control groups with no intervention: adolescent boys with PTSD in short-term cognitive processing therapy68; adult women with a history of interpersonal violence in group trauma treatment therapy69 and traumatic incident reduction therapy134; and vulnerable adolescents in group social problem-solving therapy.43 Individual cognitive-behavioral therapy and combined individual and group cognitive-behavioral therapy both led to greater improvements in overall mental health in men, with the combined group showing greater efficacy than the individual group for most outcomes.25 In persons with impulsive behavior problems, dialectical behavioral therapy group sessions and individual coaching resulted in some improvement in mental health compared with dialectical behavioral therapy group sessions and weekly case management.121

In contrast, 4 other studies of psychotherapies found no differences between intervention and control groups.86,95,96,141,144 In women with PTSD related to interpersonal victimization, there was no difference in PTSD or overall mental health status between persons randomized to group psychotherapy to enhance affect regulation without trauma memory processing or to supportive group therapy.86 There was no difference in depression or substance use outcomes in women with depression and a substance use disorder participating in interpersonal psychotherapy or psychoeducation before and after release.95,96 In a study of group cognitive therapy compared with individual supportive treatment and brief counseling in persons with depression, no significance testing was reported, but reductions in depression symptoms appeared to be similar in both groups.141 Cognitive-behavioral therapy added to a residential substance use treatment program did not improve mental health or substance use disorder outcomes in women with substance dependence and PTSD.144

Skills training during imprisonment.

Five studies measured the impact of skills training programs during imprisonment,26,49,62,64,122 only 1 of which had any positive findings.62 In adult men with anxiety, a self-help booklet based on cognitive-behavioral therapy principles led to greater improvements in anxiety and depression, but there were no changes in general mental health compared with waitlist controls.62 There was no difference in hypomania symptoms between adolescent boys randomized to a social interaction skills program, stress management training, or no treatment.122 Muscle relaxation also had no effect on anxiety or depression compared with usual care in adolescent boys.26 Training in decoding facial affect in men with schizophrenia did not affect schizophrenia symptoms compared with a waitlist.49 An attachment-based group intervention with mother and baby dyads did not affect maternal depression.64

Pharmacological interventions during imprisonment.

Six interventions assessed pharmacological interventions,50–53,57–59,81,82,90,92,132 5 of which positively affected some mental health outcomes.50–53,57–59,81,82,90,132 High-dose valproic acid treatment compared with low-dose treatment led to less illness severity in adolescent boys with conduct disorder.132 In adult women with bipolar disease, the use of an algorithm for the treatment of bipolar disease improved medication utilization and adherence compared with usual care.81,82 Osmotic release methylphenidate treatment in adult men with attention-deficit or hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) positively affected ADHD symptoms and psychosocial functioning compared with a placebo.50–53 The addition of osmotic release methylphenidate to cognitive-behavioral therapy led to fewer ADHD symptoms on most indicators and to less drug use in adult men with ADHD and amphetamine dependence.57–59 In adolescent boys, the administration of chlordiazepoxide compared with placebo was associated with less anxiety 40 minutes after administration, but this effect was not sustained at 100 minutes.90 In men with a history of violating institutional discipline rules, treatment with phenytoin compared with active placebo did not affect anxiety.92

Other interventions during imprisonment.

Of 4 studies of other interventions during imprisonment (X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014),41,44,65 2 affected mental health outcomes (X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014).44 A yoga course led to greater improvements in mental health than a waitlist.44 A group music therapy course in men with anxiety or depression had a greater effect on symptoms than standard care (X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014). In persons who used drugs, those randomized to the NADA (National Acupuncture Detoxification Association)-Acudetox auricular acupuncture protocol or to a nonspecific auricular acupuncture protocol were similar in mental health, but those in the nonspecific group had lower rates of drug use.41 A study compared assessment for treatment within 2 months of randomization with assessment after 6 months in inmates with “dangerous and severe personality disorder,” which was defined based on the predicted risk of the inmate committing an offense that would lead to serious physical or psychological harm and this risk being linked to the inmate’s personality disorder; no differences were identified between groups in quality of life at 1 year.65

Services after release.

Three interventions were implemented in the community after release,38,39,77,124,125 and 2 of these positively affected substance abuse outcomes.38,39,77 In adults on parole who received daily, automated phone assessment in the month after release, the addition of feedback and a recommendation led to greater improvements in mental health and drug and alcohol use.38,39 Persons with a serious and pervasive mental illness who were randomized to a mental health treatment court with an assertive community treatment model of case management experienced greater improvements in mental health status, functioning, and drug use, but not quality of life or alcohol use, compared with treatment as usual.77 In persons who were seriously mentally ill and homeless, there was no difference in mental health, alcohol and drug use, or quality of life at 1 year after release among those randomized to an assertive community treatment team, forensic specialist case managers based in community mental health agencies, or referral to a community mental health center.124,125

Infectious Diseases Interventions

Hepatitis B vaccination during imprisonment.

Three studies examined hepatitis B vaccination strategies during imprisonment,22,27,28,45 1 of which had a positive finding.45 An accelerated schedule of vaccination at 0, 1, and 3 weeks resulted in greater vaccination series completion compared with the routine vaccination schedule at 0, 1, and 6 months.45 The administration of double doses of vaccine separated by 1 month resulted in a similar rate of hepatitis B seroprotection compared with the routine vaccination schedule.22 A study of accelerated vaccination at 0, 1, and 8 weeks compared with the routine vaccination schedule identified no difference in seroprotection and a higher rate of vaccine series completion in men.27,28

HCV testing during imprisonment.

Two studies assessed the impact of introducing dried blood spot testing for HCV on testing rates in correctional facilities46,54; 1 study did not report significance testing,54 and the other had a null finding.46 One study conducted in men did not report significance testing specifically for the effect of the intervention in prison sites, but the difference in testing between intervention and control sites was positive across randomized pairs.54 A second study in men and women found no difference in testing rates.46

Scabies treatment during imprisonment.

A study comparing synergized pyrethrins foam with benzyl benzoate for the treatment of scabies in men found no difference in clinical cure rate or itching.42 Pyrethrins foam was tolerated overall, although it was associated with more burning and irritation after treatment.42

Latent tuberculosis infection management.

Two studies compared isoniazid and rifampicin in persons with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI),23,140 1 of which found a significant difference between groups.23 In adult men, a 4-month course of rifampicin led to a higher rate of treatment completion and fewer adverse events than 6 months of isoniazid.23 Another study in adults found no difference in treatment completion or adverse events other than elevated liver function tests when 4 months of rifampicin was compared with 9 months of isoniazid.140

HIV management after release.

A study of adults infected with HIV who were on antiretroviral therapy identified that directly administered antiretroviral therapy led to greater viral suppression and less decrease in CD4 cells in the 6 months after release than self-administered therapy (F. Altice, unpublished data, March 2014).118

Interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviors after release.

Five studies with adolescents targeted sexual risk behaviors after release,71–73,91,109,117,126 4 of which had some positive impact.71–73,91,109,117 A study in persons who abused substances found that relaxation and substance abuse education training were more effective than an individual motivational interviewing session plus group cognitive-behavioral therapy.109 A combined sexual risk reduction intervention and alcohol risk reduction motivational enhancement therapy led to more condom use compared with information only, but there was no difference between these 2 groups and a sexual risk reduction only group with respect to intercourse while drinking or problems related to alcohol use.71–73 In a trial conducted in adolescents, randomization to an HIV education intervention with a booster session was associated with more condom use compared with no intervention in girls only, and there was no difference in drug use among those randomized to the HIV education intervention with a booster, the same intervention without a booster, or no intervention.91 There was no difference in adolescents with past year alcohol or marijuana use who were randomized to relaxation training or motivational enhancement sessions of substance abuse treatment training, although in those with fewer depression symptoms, motivational enhancement sessions led to a greater reduction in some risk behaviors than did relaxation training.117 In boys, sexual risk reduction skills training was as effective as anger management training.126

Four studies assessed the effects of interventions on sexual risk behaviors in adults,85,102,107,108,113 only 1 of which had a positive finding.107,108 A study that compared a DVD-based peer-delivered intervention, a health provider-delivered National Institute of Drug Abuse standard HIV intervention, and an HIV educational video found that the peer-delivered intervention had a greater impact compared with the educational video.107,108 In persons infected with HIV, an ecosystem intervention had similar effects compared with an individually focused intervention, but was associated with worse HIV medication adherence in the 1-year follow-up period.113 In women with a history of substance abuse, skills building and social support enhancement was equivalent to the provision of standard AIDS information,85 and the effect of group sessions plus an HIV educational video was similar to that of an HIV educational video alone.102

Health Service Use Interventions

Persons with substance use disorders.

Three studies focused on improving health service use in persons with substance use disorders,74,79,123 and 2 of the interventions studied resulted in positive changes.74,79 In adults with serious mental illness and a current substance use disorder, a community-based Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment program in addition to an in-custody treatment unit increased use of outpatient medication services and reduced mean days of hospitalization, but did not affect rates of hospitalization over 18 months of follow-up.74 In veterans with a substance use disorder, a 1-hour feedback condition incorporating principles of motivational interviewing led to higher rates of scheduling an appointment at an addictions clinic, but it did not lead to higher rates of clinic attendance or treatment retention.79 Participation in a 1-month treatment program for men who used alcohol did not affect the number of attempts to obtain help for drinking problems in the year after release compared with receiving no treatment.123

Persons with mental disorders.

One study assessed the impact of a writing intervention on health care use in men with a mental disorder in a psychiatric prison.114 Writing about thoughts and feelings about traumatic events did not affect infirmary use compared with writing about trivial topics or not writing, but writing did lead to more physical symptoms at 6 weeks after the intervention.114 Writing about trivial topics was associated with greater anxiety than not writing.114

Case management.

Four studies assessed the impact of case management on health care use,56,78,112,142 2 of which had positive findings.56,78 A study of forensic assertive community treatment in persons with a major mental illness found that those who received assertive community treatment had more outpatient visits and fewer days of hospitalization over 2 years of follow-up compared with those who received treatment as usual, but there was no difference between groups in the rate of hospitalization.78 In persons with severe mental illness, a Critical Time Intervention to identify and manage priority problems before release and to continue support after release did not affect mental health or alcohol or substance abuse service use, but did increase primary care access and medication adherence.56 In adults infected with HIV, intensive case management before and after release compared with usual care did not affect clinic follow-up, hospitalization, or emergency room or urgent care visits in the year after release.142 In substance-abusing adult parolees, strengths-based case management during the transition from incarceration to the community had no greater effect than standard parole services on substance abuse treatment received, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors.112

Other.

Four other studies focused on health care use after release (S. A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014),36,135,136,138,139 3 of which had positive findings (S. A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014).36,135,136,139 In persons with LTBI, a financial incentive improved rates of follow-up at a tuberculosis clinic after release compared with usual care, and those who received tuberculosis education were more likely to attend a first tuberculosis clinic after release and to complete treatment than those who received usual care.139 In persons with a chronic medical condition or who were aged 50 years or older, randomization at release to a tailored primary care clinic staffed by community health workers and staff with experience with formerly incarcerated patients led to less emergency department use, but this program did not affect primary care use or hospitalization compared with referral to expedited primary care at another safety-net clinic.135,136 The provision of a personalized booklet summarizing health status and identifying appropriate community health services, as well as weekly contact after release by trained workers to identify health needs and facilitate health service use, led to greater primary care access and mental health service use, but there were no differences in alcohol and other drug treatment compared with usual care (S. A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014).36 In another study of persons with LTBI, a financial incentive did not improve follow-up rates when added to tuberculosis education.138

Chronic Disease Interventions

Two studies in men examined the effects of exercise programs during imprisonment, both of which found a positive effect in a minority of the outcomes studied.30,31,40 Persons randomized to a program of cardiovascular and resistance training or to high-intensity strength training had similar outcomes compared with those who received no treatment in terms of body mass index, blood pressure, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and forced expiratory volume in 1 second. However, participants in both programs improved more in oxygen saturation than those in the no treatment group, and those in the cardiovascular and resistance training group had a greater improvement in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol than those in the no treatment group.40 In persons with chronic disease, risk factors for chronic diseases, or in those aged 40 years or older, a 3-month exercise and educational intervention was associated with a lower heart rate at rest, no differences in obesity, lung function, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure at rest, or psychological distress, and had a higher diastolic blood pressure at rest compared with usual care.30,31

Risk of Bias

Table 3 shows the risk of bias for outcomes in each study by domain and overall. The risk of bias for all outcomes was low in 4 studies,50–53,63,67,135,136 high in 31 studies, and was unclear in 57 studies. In 3 studies, the risk of bias was unclear for some outcomes and high for other outcomes.24,66,111 In most cases, the overall risk of bias was classified as high because of a high risk of performance bias and detection bias. The high risk of bias in these domains was most often the result of the lack of blinding of participants and personnel, and of outcome assessment, respectively, in studies with no active comparator (e.g., that compared an intervention with no intervention) and in which the outcome was subjective (e.g., patient-reported symptoms of mental disorders).

TABLE 3—

Risk of Bias by Domain and Overall for Outcomes in Studies Included in a Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials to Improve the Health of Persons During Imprisonment or After Release (n = 95): 2014

| Study | Outcome | Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Participant and Personnel Blinding | Outcome Assessment Blinding | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Reporting | Overall Risk of Bias |

| Ahrens and Rexford 200268 | Mental health status | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Andersson et al.38 2013 and 201439 | Mental health status, substance use | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Awgu et al. 2010,104 Magura et al. 2009,105 and Lee et al. 2009106 | Substance use, medication effects | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Bahari et al. 201122 | HBV sAb sero-conversion rates | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Battaglia et al. 201340 | Blood pressure, BMI, cholesterol | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Begun et al. 2010,115 and Rose et al. 2013116 | Substance use | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Berman et al. 200121 and 200441 | Mental health status, drug use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Biele et al. 200642 | Scabies cure rate, treatment side effects | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Biggam et al. 200243 | Anxiety, depression | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| Bilderbeck et al. 201344 | Psychological distress | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Bradley et al. 200369 | Psychiatric symptoms | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Braithwaite et al. 200570 | Substance use, sexual risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Brown et al. 198029 | Alcohol use | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Bryan et al. 2009,71 Schmiege et al. 2009,72 and 201173 | Sexual and alcohol risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Cashin et al. 200830,31 | Weight, BMI, waist girth, blood glucose levels | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Psychological distress | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↑ | |

| Chan et al. 201223 | Treatment discontinuation | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Chandler and Spicer 200674 | Psychiatric hospitalization | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| X. J. Chen, unpublished data, March 2014 | Anxiety, depression | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Christensen et al. 200445 | Treatment completion | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Clarke et al. 2011128 and Stein et al. 2010129 | Alcohol use | ? | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↓ | ↑ |

| Clarke et al. 201376 | Smoking abstinence | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↓ | ↑ |

| Clair et al. 201375 | Marijuana and alcohol use | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Cosden et al. 200377 | Psychiatric status, alcohol use | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| Craine et al. 201446 | Prison HCV testing rate | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Cullen et al. 201247 | Substance use | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Cusack et al. 201078 | Behavioral health service use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Davis et al. 200379 | Treatment participation | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Davis 201180 | Substance use | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Dolan et al. 200332 and Warren et al. 200633 | Drug use, HCV, and HIV infections | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Draine124 and Solomon and Draine125 1995 | Quality of life, substance use, psychiatric symptoms | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Eibner et al. 200683 and MacDonald et al. 200784 | Alcohol use | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↓ | ↑ |

| El-Bassel et al. 199585 | Safer sex behaviors | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Ford et al. 201386 | Psychiatric symptoms | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Forsberg et al. 201148 | Drug and alcohol use | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Freudenberg et al. 201087 | Drug use, sexual risk behaviors | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Friedmann et al. 201288 and Johnson et al. 201189 | Substance use | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Frommann 201049 | Psychopathology | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| Ginsberg et al. 201250,51 and 201352 and Grann et al. 201353 | Mental health status | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Gleser et al. 196590 | Anxiety | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Goldberg et al. 200991 | Drug use, sexual risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Gordon et al. 200797 and 2008,98 Kinlock et al. 200799 and 2009,100 and Wilson et al. 2012101 | Health service utilization, drug use, HIV risk behaviors | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Gottschalk et al. 197392 | Anxiety | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Grommon et al. 201393 | Drug use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Harrell et al. 200094 | Drug use | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Hickman et al. 200854 | Prison HCV testing rate | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Howells et al. 200255 | Withdrawal symptoms | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Hser et al. 201324 | Drug use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Psychological symptoms | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ | |

| Jarrett et al. 201256 | Service engagement | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Johnson and Zlotnick 201195 and 201296 | Depression | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Alcohol and substance use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | |

| Jones et al. 201134 and 201335 | Drug use | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Kamath et al. 201181 and Ehret et al. 201382 | Medication adherence | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Khodayarifard et al. 201025 | Psychological status | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Kinner et al. 201336 and S. A. Kinner, unpublished data, June 2014 | Health service utilization | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Knudsen et al. 2014102 | Sexual risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Konstenius et al. 201357–59 | ADHD symptoms, drug use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Lee et al. 2014103 | Drug use | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Lobmaier et al. 201060,61 | Drug use | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Martin et al. 2008107 and O'Connell et al. 2007108 | Sexual risk behavior | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Martin et al. 2011109 | Sexual risk behavior | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Maunder et al. 200962 | Anxiety and depression | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ↑ | ↑ |

| McKenzie et al. 2012110 | Drug use | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Nakaya et al. 200426 | Psychological distress | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| Needels et al. 2005111 | Drug use | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| HIV risk behaviors | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ | |

| Prendergast et al. 2011112 | Substance abuse treatment, substance use, HIV risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? |

| Reznick et al. 2013113 | Sexual risk behavior, medication adherence | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Richards et al. 2000114 | Physical symptoms, anxiety, clinic visits | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Richmond et al. 201237 | Smoking | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Rosengard et al. 2007117 | Sexual risk behaviors | ↓ | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Saber-Tehrani et al. 2012118 and F. Altice, unpublished data, March 2014 | HIV disease status | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? |

| Sacks et al. 2012119 | Drug use, mental health | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Savage and McCabe 1973120 | Drug use | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↑ | ? | ↑ |

| Sheard et al. 200963 | Drug use | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Shelton et al. 2009121 | Psychopathology | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Shivrattan 1988122 | Mental health status | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Skipper et al. 1974123 | Attempts to access services | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Sleed et al. 201364 | Depression | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| St. Lawrence et al. 1999126 | Sexual risk behaviors | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Stein et al. 2006127 | Risk behaviors | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Stein et al. 2011130,131 | Substance use | ↓ | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Steiner et al. 2003132 | Mental health | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Sullivan et al. 2007133 | Substance use | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Tyrer et al. 200965 | Quality of life | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ? | ↑ |

| Valentine and Smith 2001134 | Mental health status | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Villagra Lanza and Mendéndez 201366 | Drug use | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Mental health status | ↓ | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ | |

| Wang et al. 2012135 and 2011136 | Health care utilization | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Wheeler et al. 2004137 | Alcohol use | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| White et al. 1998138 | Postrelease clinic visit | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| White et al. 2002139 | Clinic visit, treatment completion | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| White et al. 2012140 | Treatment adverse events and completion | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Wilson 1990141 | Depression | ? | ? | ? | ? | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Wohl et al. 2011142 | Access to medical care | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

| Woodall et al. 2007143 | Alcohol use | ? | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? | ? |

| Wright et al. 201167 | Drug use | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Zlotnick et al. 2009144 | Mental health status, substance use | ? | ? | ↑ | ↑ | ? | ? | ↑ |

| Zolghadr Asli et al. 201127,28 | Hepatitis B seroprotection | ↓ | ? | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ? | ? |

Note. ↑ = high; ↓ = low; ? = unclear; ADHD = attendtion-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BMI = body mass index; HBV = hepatitis B vaccine.

DISCUSSION

This review identified 95 studies of randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of people during imprisonment or in the year after release. Most studies were conducted in men, in adults, and in the United States. Most studies focused on specific health outcomes, especially substance abuse and mental health outcomes. In a majority of studies, the intervention was implemented during imprisonment, and in most studies, the outcome was assessed following release. The risk of bias was high or unclear for outcomes in almost all studies. Fifty-nine studies found a positive impact of an intervention on 1 or more health outcomes.

The number of randomized trials conducted in this population was surprisingly small, considering the large size and significant burden of disease in this population, as well as the defined role of the state in the provision of health care during imprisonment. In some cases, research with other populations and in other settings might provide evidence that is relevant to this population, such that specific trials would be redundant. Studies with other designs might also provide high quality evidence regarding interventions145 (e.g., non–randomized controlled trials). We focused on randomized controlled trials because they provided the highest quality of evidence compared with other study designs,17 and we did not include other study types in this review for feasibility reasons. These caveats notwithstanding, the small number of experimental studies in this field is remarkable.146–150

Research in prison settings and postrelease is undeniably challenging and complex,151 and remains shadowed by the legacy of ethically unacceptable research conducted during the 20th century.152,153 Contemporary challenges included ethical issues, such as ensuring voluntary consent to participation,152,153 restrictive regulations in many jurisdictions including in the United States,152 institutional barriers such as the need for and costs of security staff to supervise research activities, and logistical difficulties such as following research participants through transfers and postrelease. Nevertheless, this review demonstrates that it is possible to conduct high-quality research with prisoners and ex-prisoners. In an era of fiscal constraints and competing priorities facing government authorities, including those responsible for correctional facilities, we maintain that high-quality research is important to inform evidence-based decision-making, and might be more likely to lead to changes in policy and practice that could close the large gap between the actual and potential health of people who experience imprisonment.

Another important finding is that the evidence from randomized controlled trials did not align well with the population distribution and burden of disease. In light of the worldwide distribution of people who are imprisoned,1 there is a lack of research in low- and middle-income countries (e.g., China) and in some high-income countries (e.g., Russia). In the absence of data in the form of a common metric, such as the disability-adjusted life year or potential years of life lost, it is difficult to assess the burden of disease in this population attributable to 1 disease compared with another, or to 1 subgroup compared with another. That notwithstanding, the lack of evidence regarding interventions that addressed chronic diseases, injuries, and reproductive health is striking, as is the small number of studies conducted in adolescents and women. Furthermore, given the syndemic154 nature of disease in this population, the focus on disease-specific outcomes and interventions in most studies was clearly suboptimal.155 Interventions to strengthen health systems, including primary health care during imprisonment and at the time of release, might more effectively address the complex needs of this population. Although there is an imperative for the state to provide health care during imprisonment, the high burden of mortality, morbidity, and hospitalization postrelease suggested that a greater focus on improving health in this population during and after release is warranted.156–158

Limitations