Abstract

Objective

High level of homocysteine (Hcy) is a recognized risk factor for developing Alzheimer disease (AD). However, the mechanisms involved are unknown. Previously, it was shown that high Hcy increases brain b-amyloid (Ab) levels in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice, but no data are available on the effect that it may have on the other main pathologic features of AD such as tau.

Methods

3xTg mice with diet-induced high Hcy were compared with mice having normal Hcy. Neuronal cells were incubated with and without Hcy.

Results

Diet-induced high Hcy resulted in an exacerbation of the entire AD-like phenotype of the 3xTg mice. In particular, we found that compared with controls, mice with high Hcy developed significant memory and learning deficits, and had elevated Ab levels and deposition, which was mediated by an activation of the γ-secretase pathway. In addition, the same mice had a significant increase in the insoluble fraction of tau and its phosphorylation at specific epitopes, which was mediated by the cdk5 pathway. In vitro studies confirmed these observations and provided evidence that the effects of Hcy on Ab and tau are independent from each other.

Interpretation

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that a dietary condition that leads to an elevation of Hcy levels results in an exacerbation of all 3 major pathological features of the AD phenotype: memory deficits, and Ab and tau neuropathology. They support the concept that this dietary lifestyle can act as a risk factor and actively contribute to the development of the disease.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder with dementia, which in its sporadic form is considered the result of an interaction of both genetic and environmental risk factors. Among the latter, epidemiological and clinical studies have revealed that elevated homocysteine (Hcy) level is a modifiable risk factor for developing AD.1,2 Hcy is a sulfurcontaining amino acid and intermediate product of the methionine cycle, whose normal levels in the body are maintained by its remethylation to methionine in a reaction that requires the availability of dietary folate, vitamin B6, and B12.3 A diet with excessive methionine, or with a deficit in folate, or genetic alterations in certain enzymes of the methionine cycle increases Hcy levels in vivo.4,5

The understanding of the molecular relationship between Hcy and AD pathogenesis is important, because it could reveal clues for the treatment or prevention of AD. Several potential mechanisms underlying the deleterious effect of this amino acid in the brain have been proposed. These include oxidative stress, DNA damage, and activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.6–9 Another potential link between high Hcy and AD is an alteration of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolic pathway(s). Thus, we and others have shown that genetic and diet-induced chronic high Hcy both result in a significant increase in brain b-amyloid (Ab) levels and deposition in transgenic mouse models of AD-like amyloidosis.10–12 However, because these mice mainly model only 1 of the 2 major pathological features of the AD phenotype, it would be of great scientific interest to investigate the role that Hcy may have on the other hallmark lesion, tau neuropathology, and whether the 2 effects are linked.

With this goal in mind, in the present paper we evaluated the biologic consequences of diet-induced high Hcy in triple transgenic mice (3xTg), which develop amyloid plaques and tau tangles together with significant memory and learning deficits.13

At the end of the study, we observed that compared with controls, mice having high Hcy manifested an exacerbation of their behavioral deficits, and a significant increase in the amount of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The changes in Aβ were associated with an upregulation of the γ-secretase pathway, whereas the hyperphosphorylation of tau was secondary to a selective activation of the kinase cdk5. In vitro data corroborated these findings, because they showed that Hcy directly modulates γ-secretase and cdk5 pathways, and that these effects are independent from each other.

Taken together, our findings show for the first time the pleiotropic effect of Hcy on all 3 major AD pathological features: behavior, Aβ, and tau. They provide critical preclinical evidence that reducing this risk factor should be beneficial in individuals bearing it to prevent AD onset.

Materials and Methods

Animal and Treatments

Animal procedures were approved by the Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee and in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The 3xTg mice harboring a mutant APP (KM670/671NL), a human mutant PS1 (M146V) knockin, and tau (P301L) transgenes were used in this study. All animals were kept in a pathogen-free environment on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and had access to food and water ad libitum. The mice were randomized to 2 groups. The control group mice (n = 6; 3 males, 3 females) were given the standard rodent chow, whereas the Hcy-diet group mice (n = 7; 2 males, = females) were given a standard rodent chow deficient in folate (<0.2mg/kg), vitamin B6 (<0.1mg/kg), and B12 (<0.001mg/kg), which is known to induce HHcy in mice.14 The diet was custom-made, prepared by a commercial vendor (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and matched for calories.

Starting at = months of age, mice received the diet for 7 months until they were 12 months old. At this age time point, they underwent behavioral testing and 2 weeks later were sacrificed. During the study, mice in both groups gained weight regularly, and no significant differences in weight were detected between the 2 groups (data not shown). No macroscopic effect on the overall general health was observed in the animals receiving the diet. No macroscopic differences were observed when at sacrifice we compared major organs such as liver, spleen, heart, and kidneys between the 2 groups. After sacrifice, animals were perfused with ice-cold 0.9% phosphate-buffered saline containing 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.4. Brain was removed and dissected into 2 hemibrains by midsagittal dissection. One half was immediately stored at 280°C for biochemistry assays, the other immediately immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight for immunohistochemistry studies.

Behavioral Tests

All animals were prehandled for 3 days prior to testing, they were tested in a randomized order, and all tests were conducted by an experimenter blinded to the treatments.

Y-MAZE

The Y-maze apparatus consisted of 3 arms 32cm long × 610cm wide with 26cm walls (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). Testing was always performed in the same room and at the same time to ensure environmental consistency as previously described.15,16 Briefly, each mouse was placed in the center of the Y-maze and allowed to explore freely through the maze during a 5-minute session. The sequence and total number of arms entered were video recorded. An entry into an arm was considered valid if all 4 paws entered the arm. An alternation was defined as 3 consecutive entries in 3 different arms (ie, 1, 2, 3 or 2, 3, 1, etc). The percentage alternation score was calculated using the following formula: total alternation number/(total number of entries − 2) × 100.

FEAR CONDITIONING

The fear conditioning test paradigm was performed following methods previously described.15,16 Briefly, the test was conducted in a conditioning chamber (19 × 25 × 19 cm) equipped with black methacrylate walls, a transparent front door, a speaker, and a grid floor (Start Fear System; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). On day 1, mice were placed into the conditioning chamber and allowed free exploration for 2 minutes in the presence of white noise (65dB) before the delivery of the conditioned stimulus (CS) tone (30 seconds, 90dB, 2,000Hz) paired with a foot-shock unconditioned stimulus (US; 2 seconds, 0.6mA) through a grid floor at the end of the tone. A total of 3 CS–US pairs with a 30-second intertrial interval (ITI) were presented to each animal in the training stage. The mouse was removed from the chamber 1 minute after the last foot-shock and placed back in its home cage. The contextual fear conditioning stage started 24 hours after the training phase, when the animal was put back inside the conditioning chamber for = minutes with white noise only (65dB). The animal’s freezing responses to the environmental context were recorded. The tone fear conditioning stage started 2 hours after the contextual stage. The animal was placed back into the same chamber with different contextual cues, including white wall, smooth metal floor, lemon extract drops, and red light condition. After 3 minutes of free exploration, the mouse was exposed to the exact same 3-CS tones with 30-second ITI in the training stage without the foot-shock, and its freezing responses to the tones were recorded.

MORRIS WATER MAZE

Morris water maze was performed with the ANY-maze System (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) as previously described.15,16 The apparatus used was a white circular plastic tank (122cm in diameter) with walls 76cm high, filled with water maintained at room temperature, which was made opaque by the addition of a nontoxic white paint, and inside had a removable, square (10cm in side length) Plexiglas plat form. The tank was located in a test room containing various prominent visual cues. Mice were trained to swim to the plat form submerged 1.5cm beneath the surface of the water and invisible to the mice while swimming. The platform was located in a fixed position, equidistant from the center and the wall of the tank. Mice were subjected to 4 training trials per day (ITI515 minutes). During each trial, mice were placed into the tank at 1 of 4 designated start points in a random order. Mice were allowed to find and escape onto the submerged platform. If they failed to find the platform within 60 seconds, they were manually guided to the platform and allowed to remain there for 10 seconds. Mice were trained to reach the training criterion of 20 seconds (escape latency). They were assessed in the probe trial 24 hours after the last training session, which consisted of a 60-second free swim in the pool without the platform. Each animal’s performance was recorded for the acquisition parameters (latency to find the platform) and the probe trial parameters (number of entries to the platform and time in quadrants).

Cell Line and Treatment

Neuro-2A neuroblastoma (N2A) cells stably expressing human APP carrying the K670N/M671L Swedish mutation (N2A-APPswe) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/mL streptomycin (Cellgro, Herdon, VA), and 400mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The cells were cultured to 80 to 90% confluence in 6-well plates and then changed to fresh medium containing 50μM DL-Hcy (Sigma, St Louis, MO) with 40μM adenosine (Sigma) and 10μM erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)-adenine hydrochloride (Sigma), as previously described.10,17 Cell toxicity was monitored by measuring the amount of the lactate dehydrogenase enzyme released in the supernatant at the end of the incubation time by a colorimetric assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). After 24 hours of treatment, media were collected for Aβ1–40 measurement, and cell lysates were harvested after treatment with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer for Western blotting analyses.

Biochemical Analyses

Brain tissues were homogenized and sequentially extracted in RIPA and then formic acid (FA), where the RIPA fraction contains the soluble, whereas the FA fraction contains the insoluble forms of the Aβ peptides, as previously described.15,16 Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels were assayed by a sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Analyses were performed in duplicate and in a coded fashion.

For the analysis of Hcy levels in the brain, tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and reduced into a fine powder using mortar and pestle. The powder was resuspended in 100μl of NKPD buffer (2.68mM KCl, 1.47mM KH2PO4, 51.10mM Na2HPO4, 7.43mM NaH2PO4, 62mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, and 1mM dithiothreitol) and sonicated at 40W and 70% duty cycle for about 2 minutes, then clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes. Measurements were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis using Waters AccQ.Fluor derivitizing reagents (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) as previously described.18,19 For brain samples, the limit of detection is 0.02nmol, and linearity extends to 5,000nmol. All of the samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the amount of Hcy in the samples was normalized by milligrams of protein. For precolumn derivatization of samples and HPLC analysis, an internal standard (10μl of 2μM 1,7-diaminoheptane) was added to 10 to 60μl of mixtures of deproteinized biological extracts, and borate buffer (0.2M sodium borate, 1mM EDTA, pH 8.8) was added to produce final volumes of 80μl. The AccQ-Fluor reagent (20μl) was added, and the sample was mixed by vortexing and analyzed within 24 hours.

Western Blot Analyses

RIPA fractions of brain homogenates were used for Western blot analyses as previously described.10, 15, 16 Briefly, samples were elec trophoresed on 10% Bis–Tris gels or 3 to 8% Tris–acetate gel (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA), transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), and then incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies as indicated in the Table. After 3 washings with T-TBS (pH 7.4), membranes were incubated with IRDye 800CW-labeled secondary antibodies (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) at room temperature for 1 hour. Signals were developed with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Bioscience). β-Actin was used as internal loading control.

TABLE.

Antibodies Used in the Study

| Antibody | Immunogen | Host | Application | Source | Catalog No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4G8 | aa 18–22 of human beta amyloid (VFFAE) | Mouse | IHC | Covance, Princeton, NJ | SIG-39220 |

| APP | aa 66–81 of APP (N-terminus) | Mouse | WB | Millipore, Billerica, MA | MAB348 |

| BACE1 | aa human BACE (CLRQQHDDFADDISLLK) | Rabbit | WB | IBL, Minneapolis, MN | 18711 |

| ADAM10 | aa 732–748 of human ADAM 10 | Rabbit | WB | Millipore | AB19026 |

| PS1 | aa around valine 293 of human presenilin 1 | Rabbit | WB | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA | 3622S |

| Nicastrin | aa carboxy-terminus of human nicastrin | Rabbit | WB | Cell Signaling Technology | 3632 |

| APH1 | Synthetic peptide from hAPH-1a | Rabbit | WB | Millipore | AB9214 |

| Pen2 | aa N-terminal of human and mouse Pen2 | Rabbit | WB | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA | 36–7100 |

| sAPPα | Synthetic peptide of the C-terminal part of human sAPPα (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK) |

Mouse | WB | IBL | 11088 |

| sAPPβ | Synthetic peptide of the C-terminal part of human sAPPβ-sw (ISEVNL) |

Mouse | WB | IBL | 10321 |

| CTFs | Carboxyl fragment of APP 643–695 | Mouse | WB | Millipore | MAB343 |

| IDE | aa N-terminal of human IDE | Goat | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA | Sc-27265 |

| Neprilysin | aa 230–550 of human neprilysin | Rabbit | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Sc-9149 |

| HT7 | aa 159–163 of human tau | Mouse | WB, IHC | Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA | MN1000 |

| mTau | Purified denatured bovine microtubule- associated proteins |

Mouse | WB | Millipore | MAB3420 |

| AT8 | Peptide containing phospho-S202/T205 | Mouse | WB, IHC | Thermo Scientific | MN1020 |

| AT180 | Peptide containing phospho-T231/S235 | Mouse | WB, IHC | Thermo Scientific | P10636 |

| AT270 | Peptide containing phospho-T181 | Mouse | WB, IHC | Thermo Scientific | MN1050 |

| PHF13 | Peptide containing phospho-Ser396 | Mouse | WB, IHC | Cell Signaling Technology | 9632 |

| PHF1 | Peptide containing phospho-Ser396/S404 | Mouse | WB, IHC | Dr P. Davies | Gift |

| Actin | aa C-terminus of actin of human origin | Goat | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Sc-1616 |

IHC = immunohistochemistry; WB = Western blot.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed as described in our previous studies.15,16 Briefly, serial coronal sections were mounted on 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane–coated slides. Every eighth section from the habenular to the posterior commissure (6–8 sections per animal) was examined using unbiased stereological principles. The sections for testing Aβ were deparaffinized, hydrated, and pretreated with FA (88%) and subsequently with 3% H2O2 in methanol. The sections used for testing HT7, PHF1, PHF13, AT8, AT180, AT270, synaptophysin, PSD95, and MAP2 were deparaffinized, hydrated, and subsequently treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol, and then antigen retrieved with 10mM sodium citrate buffer. Sections were blocked in 2% fetal bovine serum before incubation with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing, sections were incubated with biotinylated antimouse immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and then developed by using the avidin–biotin complex method (Vector Laboratories) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Light microscopic images were captured using the software QCapture 2.9.13 (Quantitation Imaging Corporation, Surrey, BC, Canada) with the auto-exposure option. These images were used to calculate the area occupied by the immunoreactivities using the software Image-ProPlus (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD).

Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SigmaStat for Windows version 3.00. Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student t test or the Mann–Whitney rank sum test when a normal distribution could not be assumed. Values in all figures and the Table represent mean 6 standard error of the mean. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Diet-Induced High Hcy Impairs Cognition in 3xTg Mice

To investigate the effect of a diet deficient in folate and B vitamins on cognition in the 3xTg mice, we used 3 different paradigms. In the Y-maze test, we found that compared with controls the diet did not change the total number of arm entries of the mice (Fig 1). By contrast, we observed that treated 3xTg mice had a significant reduction in the percentage of alternation. In the fear conditioning test, 3xTg mice receiving the special diet had a significantly lower freezing time in both the contextual and the cued recall paradigm than the control group. Finally, we examined the effect of the diet on the reference spatial memory function of the mice by using the Morris water maze. In the study, we performed visible platform cued test followed by hidden platform testing with 4 training trials per day. All mice in both groups were able to reach the training criterion within 4 days and were similarly proficient swimmers (data not shown). However, in the probe test after 24 hours of last training trial, we found that diet-treated 3xTg mice had a significant decrease in the number of platform location crosses and time spent in the platform quadrant, and an increase in time spent in the opposite quadrant, without any changes in the average swimming speed.

FIGURE 1.

Diet-induced high homocysteine brain levels worsen behavioral deficits. (A) Number of total arm entries for 3xTg mice receiving supplemented diet (Diet) or vehicle (Ctrl). (B) Percentage of alternations between 3xTg mice receiving the diet or vehicle treatment. (C) Contextual fear memory response in 3xTg mice treated with the special diet and controls. (D) Cued fear memory response in the same 3xTg mice. (E) Number of entries to the target platform zone for 3xTg mice treated with the supplemented diet or control vehicle. (F) Time in the target platform zone for the same 2 groups of 3xTg mice. (G) Time in the opposite zone for the same 2 groups of 3xTg mice. (H) Average swimming speed for the same 2 groups of 3xTg mice. Values represent mean 6 standard error of the mean (n = 6 control, n = 7 diet); *p < 0.05.

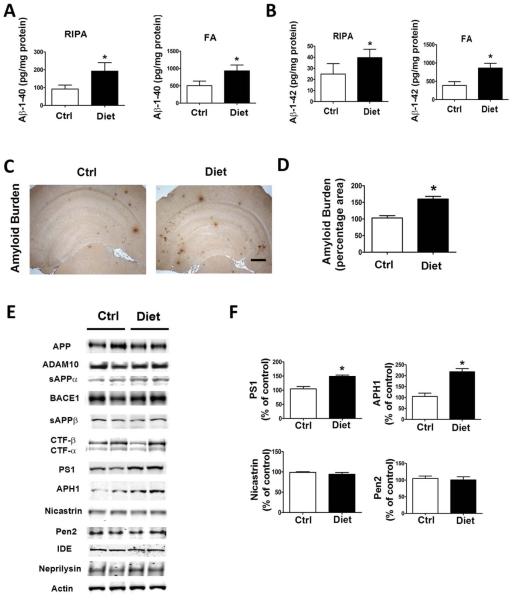

High Brain Hcy Increases Aβ Levels and Deposition via the γ-Secretase Pathway

First, we wanted to check whether the diet administered to the mice had resulted in an elevation of Hcy levels in the organ target, the central nervous system. Confirming compliance of the animals with the chronic dietary regimen, brain Hcy levels in the treated mice were significant higher than in the control group (296 ± 12 vs 160 ± 11pg/mg protein, p < 0.01). Next, we investigated whether diet-induced high Hcy in the brain altered Aβ levels and deposition in the 3xTg mice by using biochemical and immunohistochemical analyses. As shown in Figure 2A and B, we found that mice with high Hcy had a significant increase in brain levels of both soluble (RIPA extractable) and insoluble (FA extractable) Aβ1– 40 and Aβ1–42 when compared with the control group. Brain Aβ deposition studies by immunohistochemistry confirmed this observation, showing that the Aβ immunopositive areas occupied by 4G8 immunoreactions were significantly higher in the diet-treated mice than in the control group (see Fig 2C, D).

FIGURE 2.

Diet-induced high homocysteine brain levels affect β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide levels and deposition. (A, B) Radioimmunoprecipitation assay–soluble (RIPA) and formic acid extractable (FA) Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels in brain cortex of 3xTg mice receiving supplemented diet (Diet, n = 7) or vehicle (Ctrl, n = 6) were measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (C) Representative images of brains from 3xTg mice receiving the diet or placebo immunostained with 4G8 antibody. Scale bar = 500μM. (D) Quantification of the area occupied by Aβ immunoreactivity in brains of diet-treated 3xTg mice and mice receiving vehicle. (E) Representative Western blots of the antibodies APP, ADAM10, sAPPαa, BACE1, sAPPβ, CTFs, PS1, APH1, nicastrin, Pen2, IDE, neprilysin, and actin in brain cortex homogenates from 3xTg mice receiving the diet or vehicle. (F) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. Values represent mean 6 standard error of the mean (n = 6 control, n = 7 diet); *p < 0.05. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.annalsofneurology.org.]

To investigate the mechanism responsible for the effect on Aβ, we examined the metabolism of its precursor, the Aβ precursor protein (APP) using Western blot analyses. A shown in Figure 2E, we observed that diet-treated mice had a significant increase in the steady state levels of 2 of the 4 components of the γ-secretase complex, PS1 and APH1, whereas steady state levels of APP, α-secretase (ADAM10), sAPPα, β-secretase (BACE1), and sAPPβ were unchanged. We also analyzed 2 of the major proteases involved in Aβ degradation, insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) and neprilysin, and found that their steady state levels were similar between the 2 groups of animals.

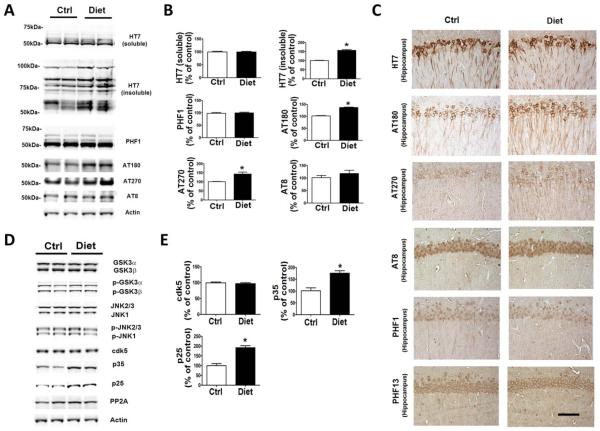

High Hcy Increases Tau Phosphorylation via cdk5 Kinase

To examine the effect of diet-induced high Hcy on tau phosphorylation, we investigated tau levels and metabolism in the same mice. Compared with the controls, diet-treated mice had a significant increase in the insoluble tau fraction, whereas there was no change in the total soluble tau level (Fig 3). In addition, we found that the same mice had higher levels of tau phosphorylated isoforms at specific epitopes: at T231/S235, as recognized by the antibody AT180, and at T181, as recognized by the antibody AT270. By contrast, no significant differences in phosphorylation were observed at other epitopes: S396, as recognized by the antibody PHF13, S396/404, as recognized by the antibody PHF1, and S202/T205, as recognized by the antibody AT8. Consistent with these results, immunohistochemical staining showed increased dendritic accumulations of the same tau phosphorylated isoforms in the brains of treated mice, whereas there were no significance differences between the 2 groups for total tau immunoreactivity.

FIGURE 3.

Diet-induced high homocysteine brain levels affect tau phosphorylation and metabolism. (A) Representative Western blots of soluble and insoluble total tau (HT7), phosphorylated tau at residues S396/S404 (PHF1), T231/S235 (AT180), T181 (AT270), and S202/T205 (AT8), and actin in brain cortex homogenates from 3xTg mice receiving the supplemented diet (Diet, n = 7) or vehicle (Ctrl, n = 6). (B) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. (C) Representative images of brain sections from diet-treated 3xTg mice or vehicle-treated control mice immunostained with HT7, AT180, AT270, AT8, PHF1, and PHF13 antibodies. Scale bar = 100μM. (D) Representative Western blots of GSK3α, GSK3β, pGSK3α, pGSK3β, JNK2/3, JNK1, p-JNK2/3, p-JNK1, cdk5, p35, p25, PP2A, and actin in brain cortex homogenates from 3xTg mice treated with supplemented diet or vehicle. (E) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. Values represent mean 6 standard error of the mean (n = 6 control, n = 7 diet); *p < 0.05. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.annalsofneurology.org.]

To study the mechanism underlying the effect on tau phosphorylation, we next examined some of the kinases that are considered major regulators of its posttranslational modifications. As shown in Figure 3D, we observed that brains of 3xTg mice with high Hcy, although they did not manifest any changes in the steady state protein levels of cdk5, had a significant increase in both the p25 and p35 fragments and activators of this kinase. By contrast, no differences were found in the levels of total or phosphorylated GSK3α, GSK3β, and SAPK/JNK pathways when the 2 groups were compared. Similarly, no changes were observed in the steady state levels of phosphatase PP2A when the diet group was compared with the controls.

Diet-Induced High Hcy Effect on Synaptic Integrity and Neuroinflammation

Because tau pathology has been correlated with the severity of dementia and memory impairments for which synaptic integrity is an important factor, we investigated whether diet-induced high Hcy had any effect on this aspect of the AD-like phenotype. As shown in Figure 4, we observed that compared with controls, steady state levels of 2 distinct synaptic proteins, synaptophysin and postsynaptic protein-95 (PDS95), but not MAP2, were significantly decreased in the mice with high Hcy. Immunohistochemical staining results were consistent with this observation. In addition, we observed that compared with controls, the same mice had a significant increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein and CD45 immunoreactivities, suggesting an activation of astrocytes and microglia cells, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Diet-induced high homocysteine brain level affects synaptic integrity and neuroinflammation. (A) Representative Western blot analyses of synaptophysin (SYP), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), and actin in brain cortex homogenates of diet-treated 3xTg mice (Diet, n = 6) or control mice (Ctrl, n = 7). (B) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. (C) Representative images of brain sections from 3xTg mice receiving the supplemented diet or vehicle immunostained with SYP, PDS95, and MAP2 antibodies. Scale bar = 100μM. (D) Representative Western blots of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and CD45 in brain cortex homogenates from diet-treated 3xTg mice and the vehicle-treated control group. (E) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. Values represent mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 6 control, n = 7 diet); *p < 0.05. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.annalsofneurology.org.]

In Vitro Study

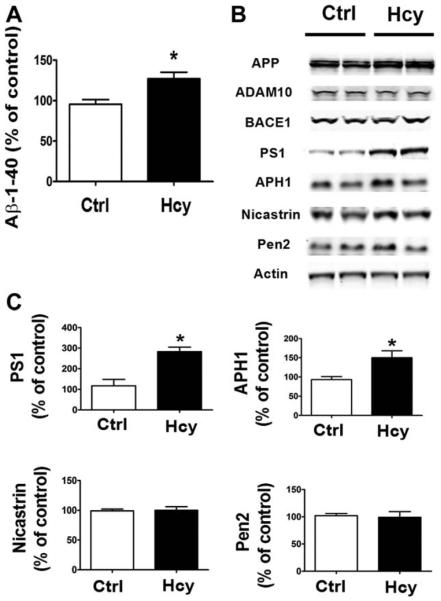

Hcy Effect on Aβ Formation and APP Processing

To further investigate the effect of Hcy on Aβ formation and APP metabolism, we treated the NA2-APPswe cells with 50μM DL-Hcy for 24 hours; supernatants were collected and assayed for Aβb1–40, and cells lysates were used to investigate APP processing. As shown in Figure 5, we found that compared with vehicle controls, conditioned media from cells incubated with Hcy had higher Ab1–40 levels. In addition, we observed that the treatment was accompanied by a significant increase in the steady state levels of PS1 and APH1. By contrast, we did not observe any changes in steady state levels of APP, ADAM10, and BACE1.

FIGURE 5.

In vitro effect of homocysteine (Hcy)-treated N2A cells on β-amyloid (Aβ) and amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolism. (A) Levels of Aβ1–40 in conditioned media from N2A cells incubated with 50μM Hcy for 24 hours. (B) Representative Western blots of antibodies APP, ADAM10, BACE1, PS1, APH1, nicastrin, Pen2, and actin in lysates from cells incubated with Hcy or vehicle (Ctrl) for 24 hours. (C) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. *p < 0.05.

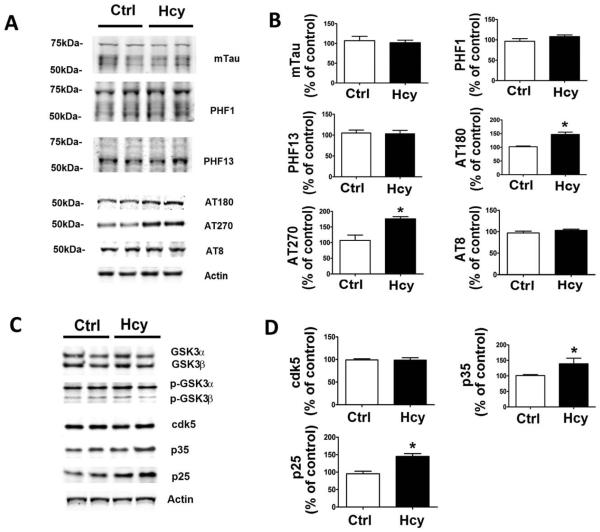

Hcy Effect on Tau Phosphorylation and Metabolism

Compared with controls, we observed that the same cells treated with Hcy had a significant increase in tau phosphorylation at T231/S235 as recognized by the antibody AT180, and at T181 as recognized by the antibody AT270 (Fig 6). By contrast, no significant changes were observed in steady state levels of total endogenous tau and other phosphorylated tau isoforms, such as tau phosphorylated at Ser202/Thr205 (recognized by AT8), at S396/ 404 (recognized by the antibody PHF1), and at Ser396 (recognized by PHF13). Moreover, immunoblot analyses showed that compared with controls, the cells treated with Hcy, although they did not manifest any changes in the steady state protein level of cdk5, had a significant elevation in the levels of its 2 coactivators, p35 and p25. By contrast, no differences were observed for another kinase also implicated in tau phosphorylation, GSK3, for both isoforms GSK3α and GSK3β in their total as well as in their phosphorylated state levels.

FIGURE 6.

In vitro effect of homocysteine (Hcy)-treated N2A cells on tau metabolism. (A) Representative Western blots of total tau (mTau), phosphorylated tau at residues S396/S404 (PHF1), S396 (PHF13), T231/S235 (AT180), T181 (AT270), and S202/ T205 (AT8), and actin in lysates from cells incubated with Hcy or vehicle (Ctrl) for 24 hours. (B) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. (C) Representative Western blots of antibodies GSK3α, GSK3β, p-GSK3α, p-GSK3β, cdk5, p35, p25, and actin in lysates from cells incubated with Hcy or vehicle (Ctrl). (D) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. *p < 0.05.

Hcy Effect on Tau Is Independent of Aβ Effect

Previously it has been reported that levels of tau and its metabolism can also be modulated by Aβ production.20 For this reason, it was important for us to investigate whether the observed Hcy effect on tau was secondary to its effect on Aβ or independent from it. To this end, we incubated N2A-APPswe cells with a specific γ-secretase inhibitor, L685,458, and investigated tau phosphorylation modifications. As shown in Figure 7, whereas as expected the drug completely suppressed the formation of Aβ, it did not influence the effect of Hcy on tau phosphorylation.

FIGURE 7.

Homocysteine (Hcy) effect on tau phosphorylation is β-amyloid (Aβ) independent. (A) Levels of Aβ1–40 in conditioned media from N2A cells incubated with 50μM Hcy alone or in the presence of L685,458 (1μM) for 24 hrs. (B) Representative Western blots of total tau (mTau), phosphorylated tau at residues T231/S235 (AT180), at T181 (AT270), and S202/T205 (AT8), and actin in lysates from cells incubated with Hcy or vehicle (Ctrl), or with Hcy in the presence of L685,458. (C) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to antibodies shown in the previous panel. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

In the current article, we provide experimental evidence that diet-induced high levels of Hcy in the central nervous system modulate all 3 major pathological aspects of the AD-like phenotype in a transgenic mouse model of the disease: behavior, Aβ pathology, and tau pathology.

Numerous studies have reported the association between high circulating levels of Hcy and AD, and longitudinal observations have found that the effect of Hcy on AD is independent of other confounders.3,21,22 However, conflicting results have also been reported.23–25 Although several potential mechanisms responsible for the deleterious effect of Hcy in the central nervous system have been proposed, its role in AD pathogenesis and the development of its different pathological features remain to be fully investigated. Previously, it was shown that crossing heterozygous cystathionine–β-synthase mutant mice, which spontaneously develop high Hcy, with APP mice resulted in higher levels of brain Aβ peptides.11 Our group and others have reported that a diet low in folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 produces high circulating Hcy levels and results also in an exacerbation of AD-like brain amyloidosis.10,12 However, due to the limitations of the APP mice, which develop only 1 of the 2 major hallmark lesions of AD (ie, amyloidosis), no data are available on whether high Hcy levels also influence the development of tau neuropathology, and importantly, whether these effects are independent from each other. With this knowledge in mind, for this study we used the 3xTg mice, which develop both amyloid plaques and tau fibrillary tangles, and fed them a folate-, B6-, and B12-deficient diet, which is a well-established model to induce high levels of Hcy.26 Because under our experimental conditions, the organ target of this diet was the central nervous system, initially we were interested to see the actual levels of this amino acid in the brain at the end of the treatment. Confirming compliance with the diet, we observed that compared with the control group, chronic administration of the special diet doubled the brain levels of Hcy in the mice. This increase resulted in worsening of their memory and learning performances, as demonstrated in 3 different experimental paradigms. Thus, compared with controls, mice with high Hcy had a significant reduction in the percentage of alternation in the Y-maze, which reflects their immediate working memory. By contrast, the same dietary treatment did not alter the number of entries, which reflects the general motor activity. The dietinduced high Hcy levels also altered their learning and memory ability, as assessed by the fear conditioning paradigm, where we observed impairments in both the cued and the contextual recall for the treated group. In a similar manner, when reference spatial memory function was assessed by the Morris water maze test, compared with controls, mice with high Hcy spent less time in the target platform quadrant, and traveled a longer distance until they reached the target platform, despite no difference in swimming speed between the 2 groups. Interestingly, a previous paper showed that diet-induced high Hcy in wild-type mice resulted in significant impairments in spatial memory and was associated with significant microhemorrhage occurrence.27 Unfortunately, our study lacks this type of control group, and further studies are warranted to assess whether cerebrovascular abnormalities also occur in transgenic mice exposed to this diet.

Consistent with the behavioral studies, we observed that brains from the diet-treated 3xTg mice had a significant elevation in the amount and deposition of Aβ peptides compared with controls. In particular, we observed that both soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 fractions were much higher in the brains of the diettreated mice than in the control group. This increase was also confirmed by an immunohistochemical approach, where we found significantly more Aβ deposition in the brain of diet-treated mice. In search of possible mechanisms of this biological effect, we investigated both the APP proteolytic and Aβ catalytic pathways in the mice’s brains. Protein levels of total APP showed no difference between the 2 groups, and both a- and β-secretase meta-bolic pathways remained unaltered. However, when we looked at the γ-secretase pathway, we found that the levels of PS1 and APH1, 2 major components of the complex, were significantly increased in the diet-treated group, suggesting an involvement of this pathway in the proamyloidotic effect of Hcy. This observation is in line with a previous report showing that elevated Hcy upregulates PS1 protein levels via demethylation of its promoter.26 To rule out other possible mechanisms responsible for the Aβ changes observed, we analyzed the protein levels of insulin-degrading enzyme and neprilysin, and found no differences between the 2 groups in any of these proteins, which are involved in Aβ clearance.28 Given the widespread expression of the APP metabolic pathway in the body, it is reasonable to hypothesize that peripheral modulation of Aβ formation by high Hcy could contribute to some of its known deleterious effects to other systems such as the cardiovascular system.29

Next, we assessed how tau levels and metabolism were affected by the high levels of Hcy. Although we did not observe any significant changes for total soluble tau, we found a significant increase in its insoluble fraction, suggesting a possible effect of Hcy on its conformation and phosphorylation. This hypothesis was corroborated by immunoblot and immunohistochemistry analyses showing a significant elevation in the phosphorylation of specific tau epitopes in the brains of diet-treated mice. To elucidate the molecular mechanism for the Hcy-induced selective tau phosphorylation, we assayed several putative tau kinases. In our study, we found no differences between the 2 groups when total and activated forms of GSK3, JNK2/3, and JNK1 were assayed. Interestingly, although we did not find any changes in the steady state levels of the cdk5 protein kinase, we detected a significant increase in the levels of p25 and p35 in the diet-treated mice, suggesting that this kinase activation is responsible for the changes in tau phosphorylation.

To further corroborate the role of Hcy in Aβ and tau metabolism, we embarked on a series of in vitro experiments. Conditioned media from neuronal cells incubated with Hcy had a significant increase in Aβ levels, which was associated with an elevation of PS1 and APH1. Additionally, immunoblot analyses showed that these cells had a significant increase in tau phosphorylation at the same epitopes as for the brain tissues from the diet mice and a selective activation of the cdk5 pathway. Because recent data from transgenic mice support the hypothesis that Aβ can modulate cellular metabolic events leading to phosphorylation-specific changes in tau,20 and considering that Hcy can act on Aβ metabolism per se,10–12 it was possible that in our study the effect on tau was secondary to that on Ab. However, based on our results we conclude that the effect of Hcy on tau phosphorylation is independent from Ab, because suppression of Aβ formation did not alter the Hcydependent tau phosphorylation.

In conclusion, our studies establish for the first time to our knowledge an active role of Hcy in all 3 key pathological changes found in AD (cognition, amyloid deposition, and neurofibrillary tangles). The elucidation of the pleiotropic role of this risk factor in AD pathogenesis and development of its phenotype provide strong biologic support for the hypothesis that its correction is a valid approach for individuals bearing this risk factor to prevent AD.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH/ NHLB1 (HL112966) (to D.P.).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Gandy S. Lifelong management of amyloid beta metabolism to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:864–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1207995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris MS. Homocysteine and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:476–483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selhub J. Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dam F, Van Gool WA. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seshadri S. Elevated plasma homocysteine levels: risk factor or risk marker for the development of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:393–398. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perna AF, Ingrosso D, De Santo NG. Homocysteine and oxidative stress. Amino Acids. 2003;25:409–417. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuszczyk M, Gordon-Krajcer W, Lazarewicz JW. Homocysteine-induced acute excitotoxicity in cerebellar granule cells in vitro is accompanied by PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of tau. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boldyrev AA, Johnson P. Homocysteine and its derivatives as possible modulators of neuronal and non-neuronal cell glutamate receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:219–228. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuo JM, Portugal GS, Kruger WD, et al. Diet-induced hyperho-mocysteinemia increases amyloid-beta formation and deposition in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:140–149. doi: 10.2174/156720510790691326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacheco-Quinto J, Rodriguez de Turco EB, DeRosa S, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemic Alzheimer’s mouse model of amyloidosis shows increased brain amyloid beta peptide levels. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuso A, Seminara L, Cavallaro RA, et al. S-Adenosylmethionine/ homocysteine cycle alterations modify DNA methylation status with consequent deregulation of PS1 and BCAE and beta-amyloid production. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oddo A, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, et al. Triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuo JM, Praticó D. Acceleration of brain amyloidosis in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model by a folate, vitamin B6 and B12-deficient diet. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu J, Li J-G, Praticó D. Zileuton improves memory deficits, amyloid and tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannopoulos PF, Chu J, Joshi YB, et al. Gene knockout of 5-lipoxygenase rescues synaptic dysfunction and improves memory in the triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:511–518. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Jamaluddin MS, Chen I, Yang F, et al. Homocysteine inhibits endothelial cell growth via DNA hypomethylation of the cyclin A gene. Blood. 2007;110:3648–3655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skelly M, Hoffman J, Fabbri M, et al. S-adenosylmethionine concentrations in diagnosis of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Lancet. 2003;361:1267–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12984-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moncada CA, Clarkson A, Perez-Leal O, Merali S. Mechanism and tissue specificity of nicotine-mediated lung S-adenosylmethionine reduction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7690–7696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Tseng B, et al. Blocking Abeta 42 accumulation delays the onset and progression of tau pathology via the C-terminus of the heat shock protein 70-interacting protein: a mechanistic link between Abeta and tau pathology. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12163–12175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2464-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quadri P, Fragiacomo C, Pezzati R, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:114–122. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, et al. Homocysteine and folate as risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:636–643. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Miller J, et al. Relation of plasma homo-cysteine to plasma amyloid beta levels. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:775–781. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aisen P, Schneider LS, Sano M, et al. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1774–1783. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhuo JM, Wang H, Praticó D. Is hyperhomocysteinemia an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk factor, an AD marker, or neither? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuso A, Nicolia V, Cavallaro RA, et al. B-vitamin deprivation induces hyperhomocysteinemia and brain S-adenosylhomocysteine, depletes brain S-adenosylmethionine, and enhances PS1 and BACE expression and amyloid-beta deposition in mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:731–746. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudduth TL, Powell DK, Smith CD, et al. Induction of hyperhomo-cysteinemia models vascular dementia by induction of cerebral microhemorrhages and neuroinflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:708–715. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guenette SY. Mechanisms of Abeta clearance and catabolism. Neuromol Med. 2003;4:147–160. doi: 10.1385/NMM:4:3:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCully KS. Homocysteine, vitamins, and vascular disease prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:S1563–S1568. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1563S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]