Abstract

Dinucleoside polyphosphates exert their physiological effects via P2 receptors (P2Rs). They are attractive drug candidates, as they offer better stability and specificity compared to nucleotides, the most common P2 receptor ligands. The activation of pancreatic P2Y receptors by nucleotides increases insulin secretion. Therefore, in the current study, dinucleoside polyphosphate analogues (di-(2-MeS)-adenosine-5′,5″-P1,P4,α,β-methylene-tetraphosphate), 8, (di-(2-MeS)-adenosine-5′,5″-P1,P4,β,γ-methylene-tetraphosphate), 9, and di-(2-MeS)-adenosine-5′,5″-P1,P3,α,β-methylene triphosphate, 10, were developed as potential insulin secretagogues. Analogues 8 and 9 were found to be agonists of the P2Y1R with EC50 values of 0.42 and 0.46 μM, respectively, whereas analogue 10 had no activity. Analogues 8–10 were found to be completely resistant to hydrolysis by alkaline phosphatase over 3 h at 37°C. Analogue 8 also was found to be 2.5-fold more stable in human blood serum than ATP, with a half-life of 12.1 h. Analogue 8 administration in rats caused a decrease in a blood glucose load from 155 mg/dL to ca. 100 mg/dL and increased blood insulin levels 4-fold as compared to basal levels. In addition, analogue 8 reduced a blood glucose load to normal values (80–110 mg/dL), unlike the commonly prescribed glibenclamide, which reduced glucose levels below normal values (60 mg/dL). These findings suggest that analogue 8 may prove to be an effective and safe treatment for type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases in the Western world, affecting up to 5% of the population.2 It is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by a chronic hyperglycemia with additional abnormalities in lipid and protein metabolism. The hyperglycemia results from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or a combination of both.3 In addition to its chronic metabolic abnormalities, diabetes is associated with long-term complications involving various organs, especially the eyes, nerves, blood vessels, heart, and kidney, which may result in blindness, amputations, cardiovascular disease, and end stage renal disease. The development of diabetic complications appears to be related to the chronic elevation of blood glucose. There is no current cure for diabetes, however, effective glycemic control can lower the incidence of diabetic complications and reduce their severity. Thus, improvement of insulin secretion is a major therapeutic goal. Approximately half of the patients with type 2 diabetes are treated with various oral agents, a considerable proportion of them with agents that stimulate insulin secretion.4,5 The choice of insulin secretagogues is limited to the sulfonylureas and related compounds (“glinides”), which elicit insulin secretion by binding to a regulatory subunit of membrane ATP-sensitive potassium channel, inducing its closure.6

Sulfonylureas have several undesired effects in addition to possible long-term adverse effects on their specific target, the pancreatic β-cell. These side effects include the risk of hypoglycemia due to stimulation of insulin secretion at low glucose concentrations, the difficulty of achieving normal glycemia in a significant number of patients, the 5–10% per year secondary failure rate of adequate glycemic control, and possible negative effects on the cardiovascular system.6,7 A growing body of evidence suggests that P2 receptors (P2Ra) for extracellular nucleotides may be involved in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Pancreatic β-cells express a variety of P2 receptors, including the P2Y1R subtype.8 P2 receptors on pancreatic β-cells respond to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) coreleased with insulin during glucose-induced exocytosis of secretory granules.9 In response to ATP, P2Y receptor activation has been shown to enhance glucose-induced insulin release from β-cells, in part due to increases in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and protein kinase A activity.9 In human pancreatic islets and isolated insulin-secreting cells, extracellular ATP also increases the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i.10 A role for P2Y1 receptor activation has been implicated in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion in mice.11

Thus, the use of P2Y1 receptor-selective ligands may represent a novel and effective approach for regulating glucose homeostasis in type 2 diabetes via increased insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells.

Indeed, structural analogues of ATP with high stability and selectivity have been shown to increase insulin secretion through activation of P2Y receptors in isolated rat pancreas12 and human islets.13 Moreover, stable analogues of ATP and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) have been shown to increase insulin secretion in vivo.14,15 Likewise, a substitution at the adenine C-2 position and modifications of the polyphosphate chain of ATP have been reported to enhance insulin secretion.16 We have reported that a C-2-thioether substitution on ATP and substitution of the nonbridging oxygen at Pα by a sulfur atom, such as 2-benzylthio-ATP-α-S, 1 (A and B isomers),17 or 2-hexylthio-ATP-α-S, 2 (A and B isomers)18 (Figure 1), generated highly specific, potent, and stable agonists of the P2Y1 receptor (e.g., EC50 values were 17 and 21 nM for 2-hexylthio-ATP-α-S, 2, A and B isomers, respectively).18 Furthermore, these ATP derivatives increased insulin secretion from rat pancreas by 100-fold, as compared to ATP.18

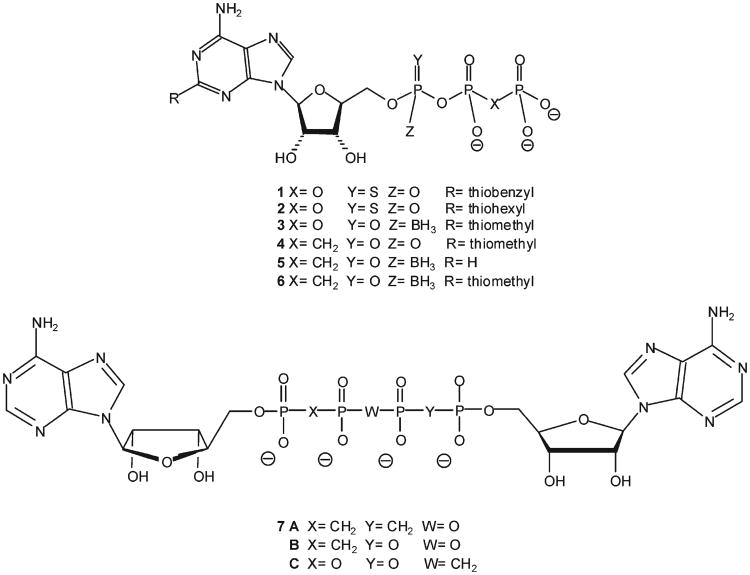

Figure 1.

P2Y1 receptor agonists.

Recently, we found that α-borano-2-MeS-ATP, 3, A isomer (Figure 1), is a potent and selective agonist of the P2Y1R, with an EC50 of 2.6 nM in HEK 293 cells overexpressing the receptor (compared with an EC50 of 0.2 μM for ATP).19 Furthermore, analogue 3A was shown to be a very potent insulin secretagogue in isolated rat pancreas, in a glucose-dependent manner, being active only at stimulating glucose concentrations,20,21 as opposed to sulfonylureas, thereby reducing the risk of hypoglycemia. The maximal efficacy of analogue 3A was 9-fold above basal secretion, with an EC50 of 28.1 nM.20 Moreover, analogue 3A exhibited high stability at physiological and gastric pH at 37 °C, with half-lives of 1395 and 5.9 h, respectively.19 In addition, analogue 3A was only weakly hydrolyzed by spleen ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (NTPDase), with only 5% degradation after 7 min at 37 °C as compared to ATP.19 Yet, analogue 3A was hydrolyzed almost completely by alkaline phosphatase over 100 min at 37 °C.22 Attempts to improve the stability of 3 by synthesizing the corresponding methylene analogues 4–6 (Figure 1), resulted in compounds highly stable to alkaline phosphatase, yet these analogues were weak P2Y1R agonists.22

Our preliminary findings, on one hand, and the side-effects of sulfonylurea-based insulin secretagogues, especially the risk of hypoglycemia, on the other hand, encouraged us to develop alternative and safe drug candidates acting via a novel mechanism. Specifically, we targeted the enhancement of insulin secretion via the activation of the P2Y1R expressed in pancreatic β-cells instead of the ATP-sensitive K+-channel activated by sulfonylureas.

In addition, we utilized a different scaffold than ATP for the design of insulin secretagogues, namely a dinucleoside polyphosphate scaffold.

Dinucleoside polyphosphates, such as Ap3A and Ap4A, induce physiological effects via activation of P2 receptors.23–27 These compounds are more stable and specific than endogenous nucleotide agonists of P2Rs and, therefore, make attractive drug candidates.28 The stability of dinucleoside polyphosphates can be further improved. Thus, the Ap4A analogues Ap(CH2)pp(CH2)pA, Ap(CH2)pppA, and App-(CH2)ppA, 7A–C (Figure 1), were synthesized with a methylene group replacing a bridging oxygen in the phosphate chain, thereby enhancing enzymatic stability.29

The enhanced metabolic stability offered by methylene bioisosters of dinucleoside polyphosphates30 encouraged us to design a novel series of stable compounds that act as insulin secretagogues via P2YR activation. Here, we report on the synthesis and characterization of dinucleoside polyphosphate analogues 8–10 (Figure 2), their resistance to hydrolysis by alkaline phosphatase, their activity at the P2Y1R, the stability of 8 (the most promising analogue) in human blood serum, and the modulation of blood glucose and insulin levels in vivo by analogue 8.

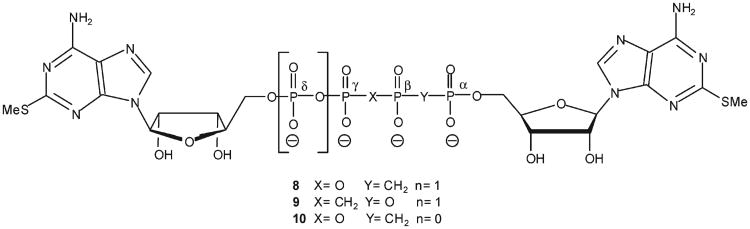

Figure 2.

A series of novel dinucleoside polyphosphate analogues.

Results

Because dinucleoside polyphosphates generally show enhanced enzymatic stability, as compared to nucleotides, and bind with high affinity to P2Y receptors,28 we designed analogues 8–10 as potential P2Y1R agonists based on dinucleoside tri- or tetra-phosphate scaffolds. To further enhance stability, we replaced the α,β or β,γ-bridging oxygen with a methylene group. To confer agonist potency and selectivity at the P2Y1R, we included a methylthio group at the adenine C2 position.31 This modification is based on our previous findings showing that incorporation of a MeS group at the C2 position of adenine nucleotides or nucleotide-methylene isosters, induces selectivity at the P2Y1R.22

Synthesis of Analogues 8–10

Dinucleoside polyphosphates are conventionally prepared via the activation of the 5′ terminal phosphate of a nucleotide with carbonyl diimidazole (CDI),32 thereby forming a phosphoryl donor (P-donor) that reacts with a nonactivated nucleotide (i.e., phosphoryl (P-acceptor)). We attempted two different approaches to synthesize analogues 8–10. In the first approach, analogue 15 was activated with CDI to generate the P-donor33 and analogue 17 was the P-acceptor (Scheme 1). In the second approach, CDI-activated analogue 17 was the P-donor and analogue 15 was the P-acceptor. The activation of 15 and 17 with CDI was monitored by TLC, which showed that analogue 15 reacted completely with CDI after 3 h, whereas the activation of analogue 17 was incomplete over this time period, likely due to the low nucleophilicity of the phosphonate in analogue 17. To overcome the low nucleophilicity of the phosphonate group in analogue 17 (Scheme 1), MgCl2 was added to the reactions because phosphoroimidazolide was reported to be most reactive in the presence of divalent metal ions.30

Scheme 1a.

aReaction conditions: (a) CH2Cl2, DMAP, TsCl, RT, 12 h. (b) Analogue 13: tetra-(n-butylammonium)methylenediphosphonate in dry DMF, RT, 48 h. (c) Analogue 14: tetra-(n-butylammonium)pyrophosphate in dry DMF, RT, 48 h. (d) 18% HCl, pH 2.3, RT for 3 h followed by 24% NH4OH, pH9, RT for 45 min. (e) CDI, DMF, RT, 3 h; f) MgCl2, RT, 12 h.

Briefly, the synthesis of analogues 8–10 involved the activation of the 2-MeS-ADP(Bu3NH)2 or 2-MeS-AMP-((octyl)3NH)2 salts with CDI in dry DMF at RT for 3 h, followed by the addition of nonactivated nucleotides, i.e., the bis/tris(Bu3NH) salts of α, β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP, 17, or β,γ-methylene-2-MeS-ATP (Scheme 1, above, Schemes 1 and 2, Supporting Information), respectively, in the presence of MgCl2 with stirring at room temperature for 12 h. Analogues 8–10 were formed as the exclusive product at good to high yields (up to 85% after LC separation). The reaction proceeded equally well with 2-MeS-AMP, 18, or 2-MeS-ADP, 15. Yet, formation of analogues 8 or 9 (Np4N) was more efficient than analogue 10 (Np3N). Analogues 8–10 were characterized by 31P NMR spectrometry and high resolution mass spectrometry. The formation of analogue 8 was confirmed by four characteristic peaks: δ 19.49 (d, Pα), 12.60 (dd, Pβ), −8.40 (d, Pγ), and –18.51 (dd, Pδ) ppm. The symmetrical analogue 9 was characterized by two peaks at 10.35 (d, Pβ) and −7.97 (d, Pα) ppm, whereas analogue 10 showed three peaks at 17.13 (d, Pα), 9.45 (dd, Pβ), and −9.93 (d, Pγ) ppm (Figure 1, Supporting Information).

Activity of Analogues 8–10 at the P2Y1 Receptor

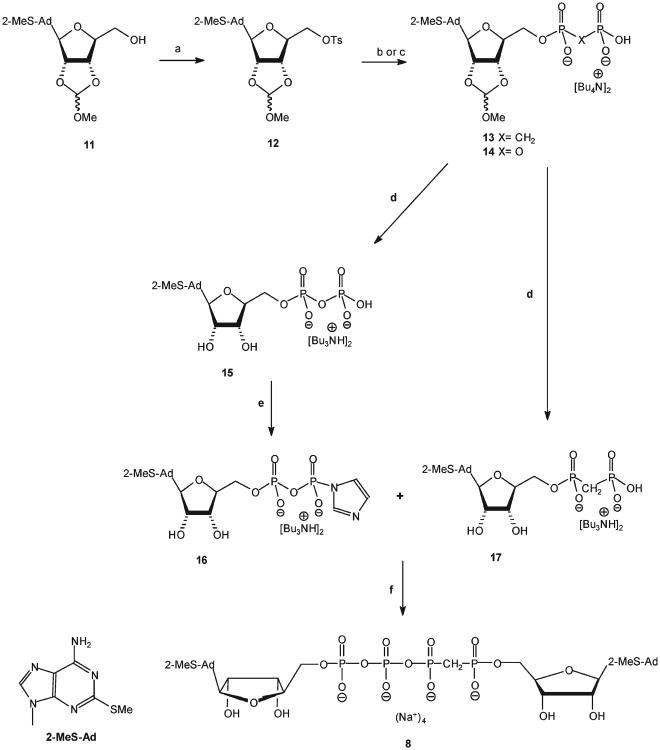

The activities of analogues 8–10 were examined at the G protein-coupled P2Y1 receptor expressed in human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells that are devoid of endogenous P2Y receptors.34 P2Y1R activity was evaluated by monitoring increases in [Ca2+]i induced by the analogues in 1321N1 cell transfectants expressing the P2Y1R. Analogues 8 and 9 activated the P2Y1R with EC50 values of 0.42 and 0.46 μM, respectively, as compared to 2-MeS-ADP (EC50 = 0.0025 μM), Figure 3. Surprisingly, analogue 10 had no activity, although the related compound Ap3A had an EC50 value of 0.011 μM.27 The different positions of the methylene groups in the phosphate chain (either between the α,β or β,γ phosphates) had practically no effect on the EC50 values of analogues 8 and 9.

Figure 3.

Agonist potency profile of compounds 8, 9, and 2-MeS-ADP for the increase in [Ca2+]i in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells expressing recombinant P2Y1 receptors. Cells loaded with Fura-2 as described in Experimental Section were exposed to 8, 9, and 2-MeS-ADP at the indicated concentrations. Each value shown is a mean ± SE of three experiments.

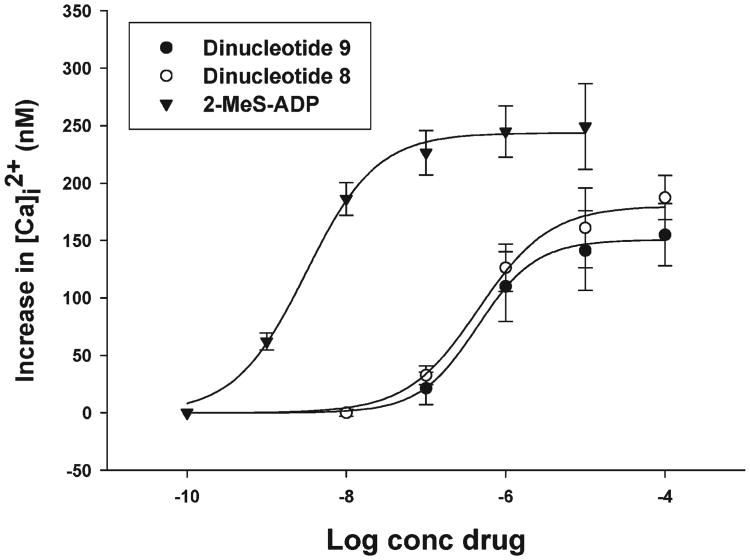

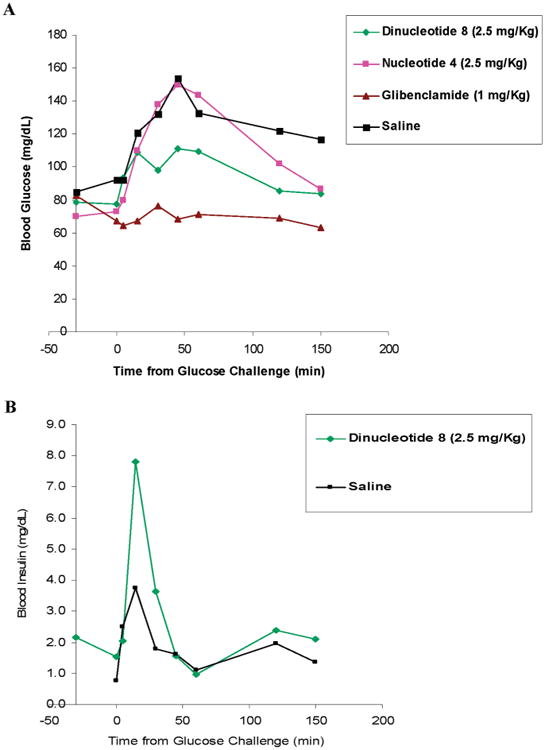

Effects of Analogues 4 and 8 on Blood Glucose Levels in Rat

Analogues 4 (a potent P2Y1R agonist22) and 8 were evaluated for in vivo efficacy in the regulation of glucose homeostasis using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in rats. Blood glucose levels of overnight-fasted Wistar Han male rats rose quickly after oral administration of a glucose challenge. However, this increase in blood glucose levels was significantly reduced when the animals were administered analogue 8 (2.5 mg/kg body weight) or glibenclamide (1 mg/kg body weight), a well-known sulfonylurea insulin secretagogue35 (Figure 4A). When rats were exposed to analogue 4, there was a reduction in blood glucose only after 150 min to ca. 85 mg/dL. In contrast, analogue 8 reduced the glucose load within 45 min from 155 to 100 mg/dL, whereas glibenclamide reduced glucose levels to ca. 63 mg/dL, a level lower than normal.

Figure 4.

Overnight fasting Wistar Han rats (5 per group) were administered (iv) 2.5 mg/kg bodyweight of analogue 4 or analogue 8, 10 min postglucose challenge. Glibenclamide was administered orally at −30 min. (A) The effect of analogues 4 or 8 (2.5 mg/kg body weight) on blood glucose levels over time were compared to glibenclamide (1 mg/kg body weight) or saline administration. (B) The effect of analogue 8 (2.5 mg/kg body weight) or saline on blood insulin concentrations over time.

Analogue 8 is a Potent Insulin Secretagogue in Rat

Insulin secretagogues act by promoting the physiological release of insulin from intracellular granulae in pancreatic β-cells. Blood insulin concentrations in male Wistar Han rats administered a glucose load were markedly increased 5 min after injection of analogue 8 (2.5 mg/kg body weight) as compared with saline (Figure 4B). Analogue 8 greatly increased blood insulin levels, i.e., 4-fold as compared to basal levels.

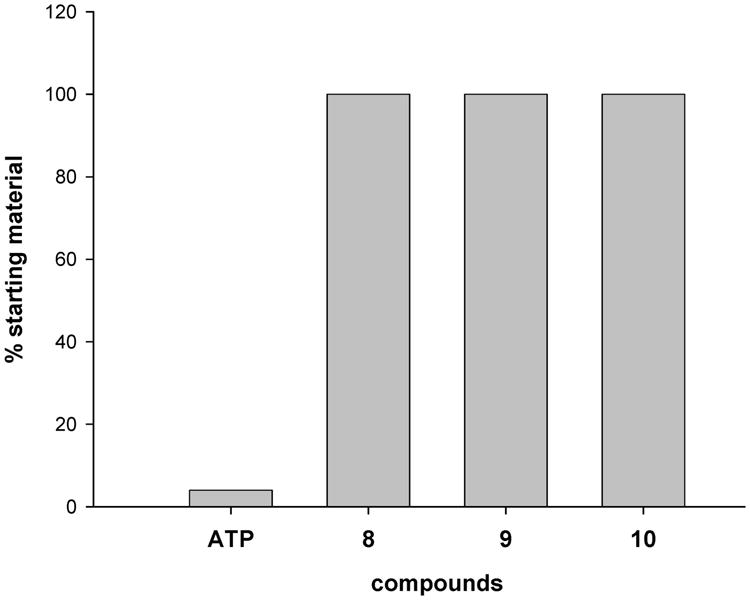

Resistance of Analogues 8–10 to Alkaline Phosphatase

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) is a hydrolase that catalyzes the removal of phosphate groups from nucleotides, proteins, and alkaloids to generate Pi and the corresponding alcohol.36 AP catalyzes the stepwise production of Pi by ATP hydrolysis to ADP and subsequently AMP.37 In humans, AP is present in all tissues.38

We found that AP hydrolyzed ATP with a half-life of 1.4 h at 37 °C. ATP was 96% degraded to ADP (4%) and AMP (92%) after 3 h, whereas analogues 8–10 remained unhydrolyzed by AP over this time course, as measured by HPLC (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hydrolysis of analogues 8−10 and ATP by alkaline phosphatase monitored by HPLC. Hydrolysis of 4 mM nucleotide by alkaline phosphatase (12.5 units) at 37 °C was monitored for 3 h.

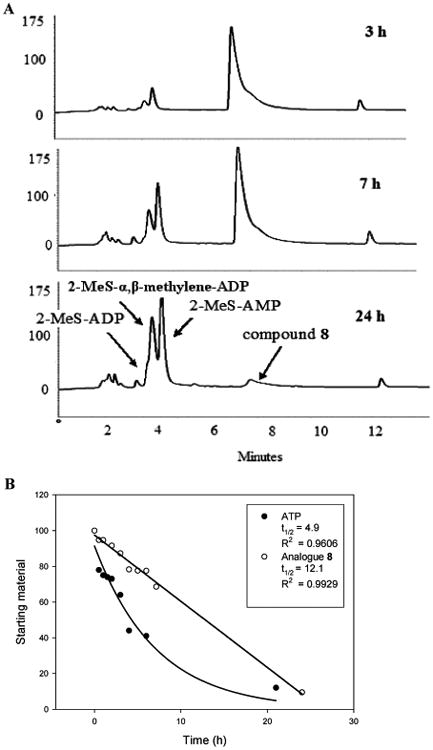

Resistance of Analogue 8 to Hydrolysis in Human Blood Serum

Blood serum contains ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatases (e-NPPs) and, therefore, provides a good model system to study the stability of dinucleoside polyphosphate analogues.

The half-life of several dinucleoside polyphosphates in human whole blood and plasma has been reported. Gp4G has a half-life in blood of ∼5 min,39 and Ap4A has half-lives of 2 and 4.4 min in whole blood and plasma, respectively, whereas the half-lives of ATP in whole blood and plasma were 3.6 and 2.2 min, respectively.40

Analogue 8, the potent P2Y1R agonist and insulin secretagogue, was hydrolyzed by human blood serum to 2-MeS-AMP, 2-MeS-ADP, and α,β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP (Figure 6A) with a half-life of 12.1 h (Figure 6B) as monitored by HPLC. In contrast, ATP was hydrolyzed to ADP and AMP with a half-life of 4.9 h under the same conditions (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of analogue 8 and ATP in human blood serum monitored by HPLC. Hydrolysis of 0.25 mM analogue 8 or ATP in human blood serum (180 μL) and RPMI-1640 (540 μL) at 37 °C was monitored for 24 h. (A) HPLC chromatograms of analogue 8 hydrolysates at 3, 7, and 24 h. The location of the peaks was determined in comparison to nucleotide standards. (B) Percentage of analogue 8 and ATP in human blood serum over time (hydrolysis t1/2 = 12.1 and 4.9 h, respectively).

Discussion

Sulfonylurea-based insulin secretagogues used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes suffer from various limitations, especially the risk of hypoglycemia. These limitations justify the search for novel insulin secretagogues acting via a protein other than the ATP-sensitive K+-channel, which is activated by sulfonylureas.

In the past years, we have attempted to develop novel insulin secretagogues targeting P2YRs present in pancreatic β-cells that are activated by extracellular nucleotides to induce insulin secretion. We focused on designing modified nucleotides as drug candidates for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.17,18 The goal of the modifications made to both the adenine (i.e., thioether at C-2) and phosphate moieties (i.e., phosphorothioate18 or boranophosphate19) was to improve the potency and selectivity of the nucleotide at P2Y1Rs that mediate insulin secretion and to improve the chemical and metabolic stability of these agonists.

Indeed, 2-hexylthio-ATP-α-S, 2, proved to be a stable and potent insulin secretagogue at isolated and perfused rat pancreas by increasing insulin secretion 100-fold, as compared to ATP.18 Yet, this compound induced a transient vasoconstriction at all concentrations tested.18

Another promising candidate was 2-thiomethyl-ATP-α-B, 3A, which induced insulin secretion 9-fold above the basal level with an EC50 of 28 nM in isolated rat pancreas.20 Yet, this analogue was hydrolyzed almost completely by AP over 100 min at 37 °C.22

Therefore, our approach in the current study was to synthesize hydrolysis-resistant P2Y1R agonists with high potency and selectivity using a diadenosine polyphosphate scaffold. Diadenosine polyphosphates are known to be more resistant to enzyme-induced hydrolysis than the corresponding mononucleotides.28 We conferred additional stability to the diadenosine polyphosphates by replacing the α,β or β,γ-bridging oxygen with a methylene group.22 In addition, we enhanced selectivity of the analogues for the P2Y1R by modifying the adenine C2-position by addition of a MeS group to form analogues 8–10 (Figure 2).

Shaver et al. reported that diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) has a similar activity and specificity to ATP at P2Y1R, in 1321N1 human astrocytoma cells. Likewise, diadenosine triphosphate (Ap3A), a structural analogue of ADP, is a potent P2Y1R agonist.27

We found that the methylene isoster of Ap3A, compound 10, was completely inactive at the P2Y1R, whereas either the α,β- or β,γ-CH2 isosters of Ap4A, 8 and 9, respectively, were moderate P2Y1R agonists. The methylene substitution reduces the potencies of analogues 8 and 9 (EC50 ∼ 0.4 μM vs 0.025 μM for 2-MeS-ADP), as compared to the parent compound Ap4A (EC50 0.011 μM vs 0.014 μM for ADP).27 Yet, both analogues 8 and 9 are structurally similar to 2-MeS-β,γ-CH2-ATP, analogue 4, which we have shown to be a potent P2Y1R agonist (EC50 80 nM vs 4 nM for 2-MeS-ADP).22 Analogues 8 and 9 activated the P2Y1R with EC50 values of 0.42 and 0.46 μM, respectively, suggesting that the position of the methylene group in the polyphosphate chain has no significant effect on agonist affinity for the P2Y1R.

Although analogue 8 has a moderate affinity for the P2Y1R, it significantly enhances insulin secretion compared to a control (saline administration; Figure 4B). Consequently, analogue 8 administration reduces a glucose load to normal levels, unlike glibenclamide, which promotes subnormal levels (Figure 4A).

No correlation was observed between the potency of analogues 4 and 8 at the P2Y1R and their in vivo activity as insulin secretagogues. In contrast to analogue 8 (EC50 420 nM at the P2Y1R), analogue 4 (EC50 80 nM at the P2Y1R) lowered blood glucose concentration only after 150 min to ca. 85 mg/dL (Figure 4A).

Summary

The diadenosine polyphosphate analogue 8 (i.e., di-(2-MeS)-adenosine 5′,5″-P1,P4,α,β-methylene-tetraphosphate) was shown to be a P2Y1R agonist with moderate affinity (i.e., EC50 0.42 μM). Analogue 8 is resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis by AP and is only slowly hydrolyzed in human serum, as compared to ATP, which is a prerequisite for P2YR agonist-based drug candidates. Furthermore, analogue 8 increased insulin release in Wistar Han rats in response to a glucose load, as compared to the saline-treated control, and subsequently blood glucose levels decreased to normal in comparison to subnormal levels induced by glibenclamide administration, a common therapy for type 2 diabetes. Therefore, analogue 8 is an attractive drug candidate for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in that it may promote insulin secretion without hypoglycemia.

Experimental Section

General

All air- and moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out in flame-dried, nitrogen-flushed, two-neck flasks sealed with rubber septa, and the reagents were introduced with a syringe. Progress of reactions was monitored by TLC on precoated Merck silica gel plates (60F-254). Visualization of reactants and products was accomplished with UV light. Nucleotides and dinucleoside polyphosphates were characterized by 1H NMR spectrometry at 200 or 300 MHz or by 31P NMR spectrometry in D2O, using 85% H3PO4 as an external reference on a Bruker AC-200 or DPX-300 spectrometer. High resolution mass spectra of nucleotides and dinucleoside polyphosphates were recorded on an AutoSpec-E FISION VG mass spectrometer using ESI (electron spray ionization) and a Q-TOF microinstrument (Waters, UK). Primary purification of the dinucleoside polyphosphates was achieved on a LC (Isco UA-6) system using a column of Sephadex DEAE-A25 swollen in 1 M NaHCO3 at 4 °C for 1 day. The resin was washed with deionized water before use. The LC separation was monitored by UV detection at 280 nm. Final purification of the dinucleoside polyphosphates was achieved by HPLC (Elite Lachrom, Merck-Hitachi) using a semipreparative reverse-phase column (Gemini 5u C-18 110A, 250 mm × 10.00 mm; 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The purity of the dinucleoside polyphosphates was evaluated by analytical reverse-phase column chromatography (Gemini 5u C-18 110A, 150 mm × 4.60 mm; 5 μm) with two solvent systems: solvent system I, (A) 100 mM triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), pH 7, and (B) CH3CN; solvent system II, (A) 0.01 M KH2PO4, pH 4.5, and (B) CH3CN. The details of the solvent system gradients used for the separation of each product are given below. In addition, novel dinucleotides were characterized by HRMS-ESI (negative). The purity of the dinucleotides was generally ≥95%. All commercial reagents were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. All reactants in moisture-sensitive reactions were dried overnight in a vacuum oven. RPMI 1640 medium was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 2′,3′-O-Methoxymethylidene-2-MeS-adenosine, 11,19 2-MeS-AMP, 18,14 β,γ-methylene-2-MeS-ATP, 20,22 α,β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP, 17, and 2-MeS-ADP, 15,42 were prepared, as previously described. α,β-Methylene-2-MeS-ADP, 17, was prepared from 12 (216 mg, 0.42 mmol), using dry DMF (1 mL) and was obtained at a 88% yield (250 mg, 0.37 mmol) after medium pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC; Biotage, Kungsgatan, Uppsala, Sweden). The spectral data for 17 were consistent with the literature.43 2-MeS-ADP, 15, was prepared from 12 (260 mg, 0.51 mmol) using dry DMF (2 mL) and was obtained at a 77% yield (206 mg, 0.39 mmol) after LC. The spectral data for 15 were consistent with the literature.41 2′,3′-O-Methoxymethylidene-2-MeS-adenosine, 11, was separated by MPLC using a silica gel (25+M) column and the following gradient scheme: 3 column volumes (CV) of 100:0 (I) CHCl3:(II) EtOH, 5 CV of a gradient from 100:0 to 90:10 I:II and 4 CV of 90:10 I:II at a flow rate of 12.5 mL/min and was obtained at a 60% yield. α,β-Methylene-2-MeS-ADP, 17, was separated by MPLC using a C-18 (12+M) column and the following gradient scheme: 5 column volumes (CV) of 100:0 (A) TEAA:(B) MeOH, 7.5 CV of a gradient from 100:0 to 60:40 A:B and 3 CV of 60:40 A:B at a flow rate of 12 mL/min. pH measurements were performed with an Orion microcombination pH electrode and a Hanna Instruments pH meter. For preparation of human blood serum, whole blood taken from healthy volunteers was obtained from a blood bank (Tel-Hashomer Hospital, Israel). Blood was stored for 12 h at 4 °C and centrifuged in plastic tubes at 1500g for 15 min at RT. The serum was separated and stored at −80 °C.

Typical Procedure for the Preparation of Dinucleoside Polyphosphates 8–10

2-MeS-AMP(Oct3NH+)2 was prepared from 2-MeS-AMP(NH4+)2 salt. α,β-Methylene-2-MeS-ADP(Bu3-NH+)2, 2-MeS-ADP(Bu3NH+)2, and β,γ-methylene-2-MeS-ATP-(Bu3NH+)2 salts were prepared from α,β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP(Et3NH+)2, 2-MeS-ADP(NH4+)3, and β,γ-methylene-2-MeS-ATP(NH4+)4 salts, respectively. All salts were passed through a column of activated Dowex 50WX-8 200 mesh, H+ form. The column eluates were collected in ice-cooled flasks containing 2 equiv of tributylamine in EtOH. The resulting solutions were freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C until use.

Bis(tributylammonium) 2-MeS-ADP salt, 15 (110 mg, 0.15 mmol), was dissolved in dry DMF (3 mL) and CDI (121 mg, 0.75 mmol) was added. The resulting solution was stirred at RT for 3 h. Dry MeOH (61 μL, 9 mmol) was added. After 30 min, a solution of bis(tributylammonium) α,β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP, 17 (112 mg, 0.15 mmol), in dry DMF (3 mL) and MgCl2 (113 mg, 8 equiv) was added. A clear solution was attained after a few minutes. The resulting solution was stirred at RT overnight. Deionized water was added, and the resulting mixture was freeze-dried. The resulting solid residue was dissolved in deionized water and separated on an activated Sephadex DEAE-A25 column. A buffer gradient of water (1 L) to 0.5 M NH4H-CO3 (1 L) was applied. The relevant fractions were collected, freeze-dried, and excess NH4HCO3 was removed by repeated freeze-drying cycles with deionized water to obtain the product as a white powder. The final dinucleoside polyphosphate purification was achieved with a semipreparative reverse-phase column and isocratic elution [CH3CN/100 mM triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), pH 7] at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The fraction containing the product was freeze-dried. The excess buffer was removed by repeated freeze-drying cycles, with the solid residue dissolved each time in deionized water. The triethylammonium counterions were finally exchanged for Na+ by passing the pure dinucleoside polyphosphate analogue through a Sephadex-CM C-25 (Na+ form) column. Analogue 8 was obtained at a 75% yield (113 mg) after LC. Analogue 9 was obtained from 2-MeS-AMP(NH4+)2, 18 (39 mg, 0.09 mmol), and β,γ-methylene-2-MeS-ATP(NH4+)4, 20 (58 mg, 0.09 mmol), at a 85% yield (78 mg) after LC. Analogue 10 was obtained from 2-MeS-AMP(NH4+)2, 18 (50 mg, 0.18 mmol), and α,β-methylene-2-MeS-ADP(Et3NH+)3, 17 (80 mg, 0.18 mmol), at a 51% yield (83 mg) after LC. The identity and purity of the products were established by 1H and 31P NMR spectrometry, MALDI mass spectrometry, and HPLC with two solvent systems.

Di-(2-MeS)-adenosine 5′,5″-P1,P4,α,β-Methylene-tetraphosphate, 8: Separation and Characterization

Analogue 8 was purified by HPLC on a semipreparative reverse-phase column using solvent system I with a gradient from 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 15 min at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. Retention time: 8.58 min. 1H NMR (D2O; 300 MHz): δ 8.22 (s; H-8; 1H), 8.21 (s; H-8; 1H), 6.00 (d; J = 3.30 Hz; H-1′; 1H), 5.98 (d; J = 3.60 Hz; H-1′; 1H), 4.78 (H2′ signals are hidden by the water signal), 4.54 (m; H-3′; 2H), 4.32 (m; H-4′, 2H), 4.22 (m; H-5′; 1H), 4.16 (m; H-5″; 1H), 2.52 (s; CH3; 3H), 2.50 (s; CH3; 3H), and 2.44 (t; J = 20.70 Hz; CH2; 2H) ppm. 31P NMR (D2O; 81 MHz): δ 19.49 (d; Jαβ =7.04 Hz; Pα), 12.60 (dd; Jαβ = 7.04 Hz, Jγβ = 24.46 Hz; Pβ), −8.40 (d; Jγδ = 18.63 Hz; Pδ), and −18.51 (dd; Jβγ = 24.46 Hz, Jδγ = 18.63 Hz; Pγ) ppm. TLC (NH4OH:H2O:isopropanol 2:8:11), Rf 0.35. HRMS MALDI (negative) m/z C23H30N10Na5O18P4S2:calculated: 1036.9620; found: 1036.9614 [M4– + (Na+)5]. Purification on an analytical column, retention time: 4.58 min(98.5% purity), using solvent system I with a gradient from 85:15 to 60:40 A:B over 15 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min;retention time: 7.72 min (97.0% purity), using solvent system II with a gradient from 95:5 to 70:30 A:B over 10 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Di-(2-MeS)-adenosine 5′,5″-P1,P4,β,γ-Methylene-tetraphosphate, 9: Separation and Characterization

Analogue 9 was purified by HPLC on a semipreparative reverse-phase column using solvent system I with a gradient from 80:20 to 74:26 A:B over 6 min at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. Retention time: 3.45 min. 1H NMR(D2O; 300 MHz): δ 8.23 (s; H-8;2H), 6.01 (d;J= 5.10 Hz; H-1′; 2H), 4.78 (H2′ signals are hidden by the water signal), 4.53 (m; H-3′; 2H), 4.34 (m; H-4′, 2H), 4.23 (m; H-5′, 5″; 4H), 2.54 (s; CH3; 6H), and 2.53 (t; J= 21.31 Hz; CH2; 2H) ppm. 31P NMR (D2O; 81 MHz): δ 10.35 (d; J = 24.94 Hz; Pβ), and −7.97 (d; J = 7.04 Hz, Jγβ = 24.94 Hz; Pα) ppm. TLC (NH4OH:H2O: isopropanol 2:8:11), Rf 0.35. HRMS MALDI (negative) m/z C23H30N10Na5O18P4S2: calculated: 1036.9610; found: 1036.9614 [M4- + (Na+)5]. Purification on an analytical column, retention time: 3.99 min (94.8% purity), using solvent system I with a gradient from 85:15 to 60:40 A:B over 15 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min; retention time: 7.84 min (91.2% purity), using solvent system II with a gradient from 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 10 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Di-(2-MeS)-adenosine 5′,5′-P1,P3,α,β-Methylene-triphosphate, 10: Separation and Characterization

Analogue 10 was purified by HPLC on a semipreparative reverse-phase column using solvent system I with a gradient from 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 15 min at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. Retention time: 8.58 min. 1H NMR(D2O; 300 MHz): δ 8.15 (s;H-8;2H), 5.96 (d; J= 4.50 Hz; H-1′; 2H), 5.94 (d; J = 4.80 Hz; H-1′; 2H), 4.68 (m; H-2′; 2H), 4.49 (m; H-3′; 2H), 4.31 (m; H-4′, 2H), 4.24 (m; H-5′; 2H), 4.15 (m; H-5″; 2H), 2.50 (s; CH3; 3H), 2.48 (s; CH3; 3H), and 2.37 (m; CH2;4H)ppm. 31P NMR(D2O; 81 MHz): δ17.13 (d; Jβα = 8.66 Hz; Pα), 9.45 (dd; Jαβ = 8.66 Hz, Jγβ = 25.92 Hz; Pβ), and –9.93 (d; Jβγ = 25.92 Hz; Pγ) ppm. TLC (NH4OH:H2O: isopropanol 2:8:11), Rf 0.61. HRMS MALDI (negative) m/z C23H27D3N10O15P3S2: calculated: 846.0734; found: 846.0729 (M-3-deuterium). Purification on an analytical column, retention time: 5.20 min (99.7% purity), using solvent system I with a gradient from 85:15 to 60:40 A:B over 15 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min; retention time: 5.33 min (99.1% purity), using solvent system II with a gradient from 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 10 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

2′,3′-O-Methoxymethylidene-5′-O-Tosyl-2-MeS-adenosine, 12

A solution of 4-DMAP (132 mg, 1.07 mmol, 4 equiv)in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) and a solution of TsCl (130 mg, 0.67 mmol, 2.5 equiv) in dry CH2Cl2 (1 mL) were added to a suspension of 2′,3′-O-methoxymethylidene 2-MeS-adenosine, 11 (95 mg, 0.27 mmol), in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) in a flame-dried two-neck flask under N2 at RT. The suspension turned clear, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. CH2Cl2 (30 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, which was extracted with saturated NaHCO3 solution (3 × 30 mL). The organic phase was treated with Na2SO4 and filtered. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was separated by MPLC using a silica gel (25+M) column and the following gradient scheme: 3 column volumes (CV) of 100:0 (A) CH2Cl2:(B) EtOH, 5 CV of a gradient from 100:0 to 90:10 A:B and 4 CV of 90:10 A:B at a flow rate of 25 mL/min. The relevant fraction was collected and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to obtain analogue 12 at a 85% yield (115 mg) as a white solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3; 200 MHz): δ 7.83 (s; H-8; 2H), 7.69, 7.23 (2 m, 2H), 6.34, 6.29 (2 br s, NH2, 2H), 6.17, 6.05 (2d; J = 2.60 Hz; H-1′, 1H), 6.07, 6.01 (2s, CH–OMe, 1H), 5.56, 5.53 (2dd; J = 2.60 Hz; H-2′; 1H, J = 7.20 Hz; H-2′, 1H), 5.21, 5.06 (2dd, J = 7.20 Hz; H-3′; 1H, J = 3.20 Hz; H-3′, 1H), 4.66, 4.52 (2 m, H-4′, 1H), and 4.31 (m, H5′, H5″, 4H) ppm. MS-ESI m/z 584 (M–). TLC(CHCl3:EtOH9:1), Rf 0.64.

Evaluation of the Stability of Analogues 8–10 with Alkaline Phosphatase

Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined by the release of p-nitrophenol from p-nitrophenyl phosphate measured by a UV–vis spectrophotometer at 405 nm.44 Relative enzymatic hydrolysis and resistance to hydrolysis of analogues 8–10 were determined at 37 °C. A solution of 0.2 mg of the analogue in 77.5 μL deionized water, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, and 0.1 M MgCl2 containing calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (Fermentas Inc., Glen Burnie, MD; 10 unit/μL; 1.25 μL, 12.5 units) was incubated at 37 °C. The final pH was 9.8. After 3 h, the reaction was stopped by incubation of the sample at 80 °C for 15 min. Samples were loaded onto an activated starta X-AW weak anion exchange cartridge, washed with H2O (1 mL) and MeOH:H2O (1:1, 1 mL), eluted with NH4OH:MeOH:H2O (2:25:73, 1 mL), and then freeze-dried. The resulting residue was analyzed by HPLC on a Gemini analytical column (5μ C-18 110A; 150 mm × 4.60 mm), using gradient elution with solvent system I at 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 12 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The hydrolysis rates of analogues 8–10 with alkaline phosphatase were determined by measuring the change in the integration of the HPLC peaks for each analogue over time.

Evaluation of the Stability of Analogue 8 in Human Blood Serum

The assay mixture containing 40 mM analogue 8 in deionized water (4.5 μL), human blood serum (180 μL), and RPMI-1640 medium (540 μL)22 was incubated at 37 °C for 0–24 h and aliquots were withdrawn at 0.5-12 h intervals. Each sample was then heated to 80 °C for 30 min, treated with CM Sephadex (1–2 mg), stirred for 2 h using a magnetic stirrer, centrifuged for 6 min (13000 rpm; 17900 rcf), and the aqueous layer was collected and extracted with chloroform (2 × 500 μL). The aqueous layer was freeze-dried and then dissolved in 100 μL of deionized water. Samples were loaded onto an activated start a X-AW weak anion exchange cartridge, washed with H2O (1 mL) and MeOH:H2O (1:1, 1 mL), eluted with NH4OH:MeOH:H2O (2:25:73,1 mL), and then freeze-dried. The resulting residue was analyzed by HPLC on a Gemini analytical column (5u C-18 110A; 150 mm × 4.60 mm) using gradient elution with solvent system I at 90:10 to 70:30 A:B over 12 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The hydrolysis rate of analogue 8 in human blood serum was determined by measuring the change in the integration of the HPLC peak for analogue 8 over time.

Intracellular Calcium Measurements

Human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells stably expressing the turkey P2Y1 receptor were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 500 μg/mL Geneticin (G-418; Life Technologies, Inc.). Changes in the intracellular free calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i, were detected by dual-excitation spectrofluorometric analysis of cell suspensions loaded with fura-2, as described previously.45,46 Cells were treated with the indicated nucleotide or analogue at 37 °C in 10 mM Hepes-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2, and the maximal increase in [Ca2+]i was determined at various nucleotide or analogue concentrations to calculate the EC50. Concentration-response data were analyzed with the Prism curve fitting program (GraphPAD Software, San Diego, CA). Three experiments were conducted on separate days to evaluate P2Y1 receptor activity.

In Vivo Study. Animals

All animal studies were performed by Vetgenerics Ltd. (Rehovot, Israel). Wistar Han male rats, 10-11 weeks old, were supplied by Harlan Laboratories (Israel). All rats were acclimatized for 6 days prior to commencement of the study. Rats were inspected daily for health and welfare throughout the study. The animals were weighed, and those most uniform in weight were surgically cannulated. Cannulated rats were examined for approximately 48 h following the surgical cannulation to ensure recovery.

Surgical Cannulation Procedure

Animals were anesthetized with 2.5% isofluran and 97.5% dry air inhalation. Anesthetized rats were secured in the supine position, and a 2 cm midline neck incision was fashioned to access the jugular vein and carotid artery. A P52 cannula was surgically inserted and fixed in the jugular vein and flushed with 0.3–0.5 mL of 5% (v/v) heparinized saline after cannulation and also immediately after each blood collection.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

The function of each cannula was checked in the morning of each experiment. Overnight fasting Wistar Han rats with functional cannulae were weighed and their peripheral tail vein blood glucose levels were measured (Abbott Glucometer FreeStyle and/or FreeStyle Lite), and animals with similar weights and blood glucose levels were assigned to the same group. Then rats were left untouched in individual cages for approximately 2 h. Glibenclamide (1 mg/kg body weight, per os) was administrated at t = − 30 min, and then a glucose challenge of 2 g/kg body weight in a volume of 3 mL/kg body weight was orally administered to each rat at t = 0 min. Administration of analogues 4 or 8 (2.5 mg/kg body weight, iv) and saline control to rats (5 per group) was performed at t = 10 min. Analogues 4 or 8 or saline were injected intravenously via an iv catheter in volumes of 1 mL saline/kg body weight. Blood glucose levels were measured immediately following tail-vein puncture by placing a blood droplet on a glucometer stick inserted into a glucometer (Abbott FreeStyle and/or FreeStyle Lite).

For measurements of insulin concentration, blood samples (150 μL) were withdrawn via the jugular vein cannula and collected in 0.8 mL tubes containing Z serum/Gel (Mini Collect, Greiner-bio-one, Austria). Blood was allowed to clot at RT for at least 30 min. Postclotting, the blood was centrifuged (3000g, 15 min) in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4 °C. Serum was harvested, divided into 25 μL aliquots in 0.2 mL flat cap PCR tubes (Neptune, USA cat. no. 3423), and stored frozen at −20 °C for 5-7 days pending analysis. Serum insulin concentration was determined using a Rat/Mouse Insulin kit from Smart Assays, QBI Laboratories, Nes-Ziona, Israel.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: P2R, P2 receptor; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; NpnN′, dinucleoside polyphosphate; e-NTPDase, ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase; e-NPPs, ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatases; MPLC, medium pressure liquid chromatography; TEAA, triethylammonium acetate; CDI, carbonyldiimidazole; HRMS MALDI, high resolution mass spectrometry matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization; MS-ESI, electron spray ionization mass spectrometry

Supporting Information Available: Characterization of analogues 8–10 by 31P NMR and syntheses of analogues 9–10. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fischer B, Nahum V. U.S. Patent 7,368,439. Dinucleoside poly(borano)phosphate derivatives and uses thereof. 2008

- 2.Ashcroft F, Rorsman P. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: not quite exciting enough? Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:R21–R31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365:1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UPDSU Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishida H. Mechanism of action of antidiabetic sulfonylureas. Diabetes Front. 1999;10:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebovitz H. Oral Antidiabetic Agents. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1994. pp. 508–529. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibowitz G, Cerasi E. Sulfonylurea treatment of NIDDM patients with cardiovascular disease: A mixed blessing? Diabetologia. 1996;39:503–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00403296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutinho-Silva R, Parsons M, Robson T, Burnstock G. Changes in expression of P2 receptors in rat and mouse pancreas during development and ageing. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s004410100458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farret A, Lugo-Garcia L, Galtier F, Gross R, Petit P. Pharmacological interventions that directly stimulate or modulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cell: Implications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19:647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kindmark H, Kohler M, Nilsson T, Arkhammar P, Wiechel KL, Rorsman P, Efendic S, Berggren PO. Measurements of cytoplasmic free Ca2+concentration in human pancreatic islets and insulinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81309-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leon C, Freund M, Latchoumanin O, Farret A, Petit P, Cazenave JP, Gachet C. The P2Y1 receptor is involved in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and in insulin secretion in mice. Purinergic Signalling. 2005;1:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertrand G, Chapal J, Loubatieres-Mariani MM, Roye M. Evidence for two different P2-purinoceptors on beta cell and pancreatic vascular bed. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;91:783–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Alvarez J, Hillaire-Buys D, Loubatieres-Mariani MM, Gomis R, Petit P. P2 receptor agonists stimulate insulin release from human pancreatic islets. Pancreas. 2001;22:69–71. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abracchio MP, Williams M. Purinergic and Pyrimidinergic Signaling. Vol. 151. Springer; Berlin: 2001. pp. 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farret A, Vignaud M, Dietz S, Vignon J, Petit P, Gross R. P2Y purinergic potentiation of glucose-induced insulin secretion and pancreatic beta-cell metabolism. Diabetes. 2004;53:S63–S66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapal J, Hillaire-Buys D, Bertrand G, Pujalte D, Petit P, Loubatieres-Mariani MM. Comparative effects of adenosine-5′-triphosphate and related analogs on insulin secretion from the rat pancreas. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1997;11:537–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1997.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillaire-Buys D, Shahar L, Fischer B, Chulkin A, Linck N, Chapal J, Loubatieres-Mariani MM, Petit P. Pharmacological evaluation and chemical stability of 2-benzylthioether-5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate)-adenosine, a new insulin secretagogue acting through P2Y receptors. Drug Dev Res. 2001;53:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer B, Chulkin A, Boyer JL, Harden KT, Gendron FP, Beaudoin AR, Chapal J, Hillaire-Buys D, Petit P. 2-Thioether 5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate)adenosine derivatives as new insulin secretagogues acting through P2Y-receptors. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3636–3646. doi: 10.1021/jm990158y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahum V, Zuendorf G, Levesque SA, Beaudoin AR, Reiser G, Fischer B. Adenosine 5′-O-(1-boranotriphosphate) derivatives as novel P2Y1 receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2002;45:5384–5396. doi: 10.1021/jm020251d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farret A, Filhol R, Linck N, Manteghetti M, Vignon J, Gross R, Petit P. P2Y receptor mediated modulation of insulin release by a novel generation of 2-substituted-5′-O-(1-boranotriphosphate)-adenosine analogues. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2665–2671. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevassus H, Roig A, Belloc C, Lajoix AD, Broca C, Manteghetti M, Petit P. P2Y receptor activation enhances insulin release from pancreatic beta-cells by triggering the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathway. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:464–469. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliahu SE, Camden J, Lecka J, Weisman GA, Sevigny J, Gelinas S, Fischer B. Identification of hydrolytically stable and selective P2Y1 receptor agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyle CHV, Hilderman RH, Pintor JJ, Schluter H, King BF. Diadenosine polyphosphates as extracellular signal molecules. Drug Dev Res. 2001;52:260–273. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pintor J, Peral A, Hoyle CHV, Redick C, Douglass J, Sims I, Yerxa B. Effects of diadenosine polyphosphates on tear secretion in New Zealand white rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:291–297. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mediero A, Peral A, Pintor J. Dual roles of diadenosine polyphosphates in corneal epithelial cell migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4500–4506. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzman-Aranguez A, Crooke A, Peral A, Hoyle CHV, Pintor J. Dinucleoside polyphosphates in the eye: from physiology to therapeutics. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2007;26:674–687. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaver SR, Rideout JL, Pendergast W, Douglass JG, Brown EG, Boyer JL, Patel RI, Redick CC, Jones AC, Picher M, Yerxa BR. Structure-activity relationships of dinucleotides: potent and selective agonists of P2Y receptors. Purinergic Signalling. 2005;1:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yerxa BR, Sabater JR, Davis CW, Stutts MJ, Lang-Furr M, Picher M, Jones AC, Cowlen M, Dougherty R, Boyer J, Abraham WM, Boucher RC. Pharmacology of INS37217 [P1-(uridine 5′)-P4-(2′-deoxycytidine 5′)tetraphosphate, tetrasodium salt], a next-generation P2Y2 receptor agonist for the treatment of cystic fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:871–880. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guranowski A, Biryukov A, Tarussova NB, Khomutov RM, Jakubowski H. Phosphonate analogs of diadenosine 5′,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate as substrates or inhibitors of prokaryotic and eukaryotic enzymes degrading dinucleoside tetraphosphates. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3425–3429. doi: 10.1021/bi00386a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nahum V, Tulapurkar M, Levesque SA, Sevigny J, Reiser G, Fischer B. Diadenosine and diuridine poly(borano)phosphate analogs: synthesis, chemical and enzymatic stability, and activity at P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1980–1990. doi: 10.1021/jm050955y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer B, Boyer JL, Hoyle CHV, Ziganshin AU, Brizzolara AL, Knight GE, Zimmet J, Burnstock G, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Identification of potent, selective P2Y-purinoceptor agonists: structure-activity relationships for 2-thioether derivatives of adenosine 5′-triphosphate. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3937–3946. doi: 10.1021/jm00076a023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zatorski A, Goldstein BM, Colby TD, Jones JP, Pankiewicz KW. Potent inhibitors of human inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase type II. fluorine-substituted analogs of thiazole-4-carboxamide adenine dinucleotide. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1098–1105. doi: 10.1021/jm00007a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoard DE, Ott DG. Conversion of mono- and oligodeoxyribonucleotides to 5′-triphosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:1785–1788. doi: 10.1021/ja01086a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parr CE, Sullivan DM, Paradiso AM, Lazarowski ER, Burch LH, Olsen JC, Erb L, Weisman GA, Boucher RC, Turner JT. Cloning and expression of a human P2U nucleotide receptor, a target for cystic fibrosis pharmacotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3275–3279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostergard T, Degn KB, Gall MA, Carr RD, Veldhuis JD, Thomsen MK, Rizza RA, Schmitz O. The insulin secretagogues glibenclamide and repaglinide do not influence growth hormone secretion in humans but stimulate glucagon secretion during profound insulin deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:297–302. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hull WE, Halford SE, Gutfreund H, Sykes BD. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance study of alkaline phosphatase: the role of inorganic phosphate in limiting the enzyme turnover rate at alkaline pH. Biochemistry. 1976;15:1547–1561. doi: 10.1021/bi00652a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moss DW, Walli AK. Intermediates in the hydrolysis of ATP by human alkaline phosphatase. Biochim Biophys Acta, Enzymol. 1969;191:476–477. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harada M, Udagawa N, Fukasawa K, Hiraoka BY, Mogi M. Inorganic pyrophosphatase activity of purified bovine pulp alkaline phosphatase at physiological pH. J Dent Res. 1986;65:125–127. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grau V. Union de diguanosin tetrafosfato a cerebro de rata. Universidad de Extremadura; Badajoz, Spain: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luethje J, Ogilvie A. Catabolism of Ap4A and Ap3A in whole blood. The dinucleotides are long-lived signal molecules in the blood ending up as intracellular ATP in the erythrocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skoblov MY, Yas'ko MV, Skoblov YS. The preparation of 32P-labeled 2-methylthioadenosine di- and triphosphates. Bioorg Khim. 1999;25:702–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davisson VJ, Davis DR, Dixit VM, Poulter CD. Synthesis of nucleotide 5′-diphosphates from 5′-O-tosyl nucleosides. J Org Chem. 1987;52:1794–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boeynaems JM, Goldman M, Marteau F, Communi D. Use of purinergic and pyrimidinergic receptor agonists for dendritic cell-based immunotherapies. 2006-EP7966 2007020018, 20060811. 2007

- 44.Brandenberger H, Hanson R. Spectrophotometric determination of acid and alkaline phosphatases. Helv Chim Acta. 1953;36:900–906. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrad RC, Otero MA, Erb L, Theiss PM, Clarke LL, Gonzalez FA, Turner JT, Weisman GA. Structural basis of agonist-induced desensitization and sequestration of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Consequences of truncation of the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29437–29444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.