Abstract

Here we report a scalable route to the polyhydroxylated steroid ouabagenin with an unusual spin on the age-old practice of steroid semi-synthesis. The incorporation of both redox and stereochemical relays during the design of this synthesis resulted in efficient access to more than 500 mg of a key precursor towards ouabagenin–and ultimately ouabagenin itself–and the discovery of innovative methods for C–H and C–C activation and C–O bond hemolysis. Given the medicinal relevance of the cardenolides in the treatment of congestive heart failure, a variety of ouabagenin analogs could potentially be generated from the key intermediate as a means of addressing the narrow therapeutic index of these molecules.

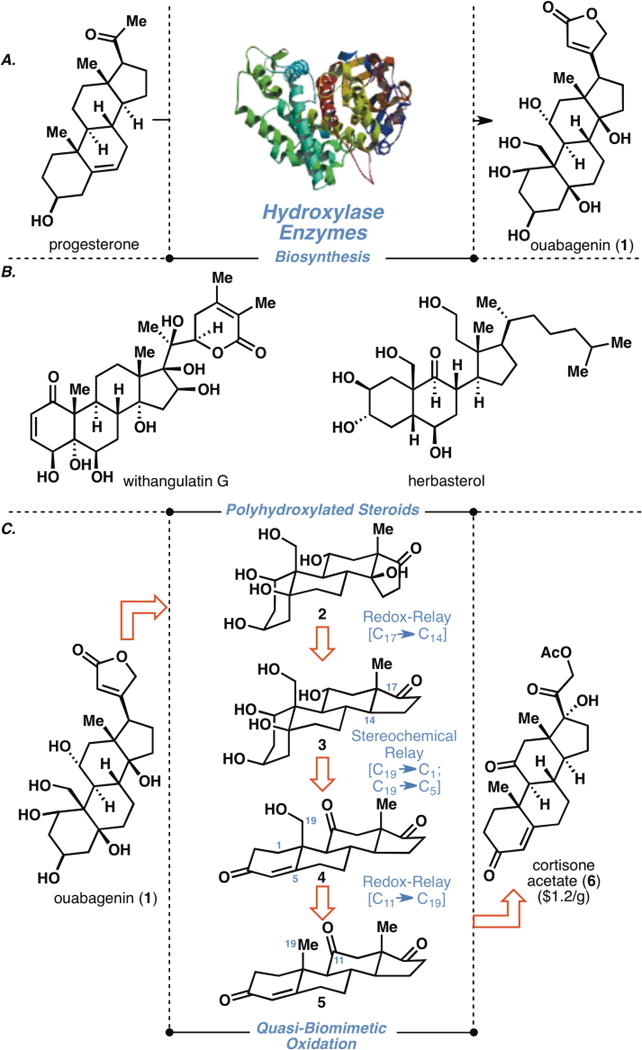

In the realm of terpene synthesis, nature has evolved a highly efficient biosynthetic system to achieve chemo and stereoselective oxidations far beyond the capabilities of chemical synthesis in the laboratory. For example, the complex steroid ouabagenin is thought to have arisen from progesterone (Figure 1A) through a series of direct, chemoselective oxidations employing a multitude of hydroxylase enzymes (1). A step-by-step emulation of this oxidation sequence is difficult, if not impossible, to execute in a laboratory setting. As a way to circumvent this direct oxidation problem, a plethora of directed oxidation methods have been invented (2), whereby a template is typically appended to effect site-selective oxidation(s) on a molecular framework. Historically, another approach, which relies on the innate reactivity profile of the framework in the absence of a directing template, has also been widely employed, as evidenced by the wealth of synthesis literature on terpene functionalizations (3, 4). Use of this approach has enabled semi-syntheses of highly complex steroids such as digitoxin (5), batrachotoxin (6), dihydroconessine (7), cyclopamine (8), cortistatin A (9), and withanolide A (10) and has laid a foundation for pharmaceutical research on commercial semi-synthetic steroid medicines such as finasteride, dexamethasone, and progestin. Despite these achievements, the scalable synthesis of polyhydroxylated steroids (more than five hydroxyl moieties on the tetracyclic skeleton, Figure 1B) is rare. Herein we report the accomplishment of such a feat using a quasi-biomimetic oxidation approach, which relies on the strategic interplay of two relay elements: (i) redox-relay, defined as transfer of redox information from one site to another within a framework, and (ii) oxidative stereochemical relay, defined as transfer of stereochemical information during an oxidative process.

Figure 1.

(A) Biosynthesis of highly complex steroid ouabagenin; (B) Selected examples of polyhydroxylated steroids; (C) Retrosynthetic analysis of ouabagenin.

Ouabagenin (1) was specifically chosen as a target molecule to showcase the application of this quasi-biomimetic oxidation strategy because of its highly oxidized molecular framework and its biological relevance as a positive inotrope (11). Ouabagenin belongs to a unique class of steroids known as cardenolides possessing both cis A/B and C/D ring fusions with an angular hydroxyl moiety at C14 as well as a β-oriented butenolide substituent at C17. The high oxidation level of its framework poses a formidable challenge for synthesis efforts, and in addition, the predominantly β-orientation of its polyhydroxylation pattern renders ouabagenin an able ligand to inorganic species (12), including borosilicate glassware. Its parent glycoside, ouabain, along with digoxin and digitoxin, is used as a treatment for congestive heart failure, a progressive condition that currently affects approximately two million people in America alone (13). The use of cardiotonic steroids, however, is complicated by an extremely narrow therapeutic index, and patients are often treated with 60% of the toxic dose. Although structure-activity relationship studies have been conducted on cardenolides and related bufadienolides (14, 15), they have been limited to hydroxylated analogs and no studies have been done on other heterocyclic analogs. Thus, a de novo synthesis that would allow versatile topological diversification could lead to the development of further analogs potentially possessing a wider therapeutic window as safer alternatives (16). A previous synthesis of ouabagenin by Deslongchamps, while an elegant accomplishment, proceeded in 41 steps from Hajos-Parrish ketone in 0.21% overall yield and relied on a relay synthesis from degradation of authentic ouabain (17). In addition, several synthetic studies on this molecule have been disclosed (18).

In our synthesis planning (Figure 1C), we envisioned that the butenolide moiety would be appended late in the synthesis, revealing the ouabagenin ketonic core, so-called ouabageninone (2) in a retrosynthetic sense. Three relay events, systematically applied during the planning stage, formed the basis of our approach. The first required installation of the tertiary alcohol at C14 on pentaol 3 through relay of the redox information coded in the C17 ketone. Oxidative stereochemical relay–another modality of this strategy–would leverage the primary alcohol at C19 to correctly install the requisite oxidation state at the C1 and C5 positions. Lastly, disconnection of the hydroxyl group at C19 inspired the invention of a redox-relay from the C11 ketone functionality of 5. The requisite hydroxyl moieties at C3 and C11 would be generated from stereocontrolled reductions of the respective carbonyl groups. In light of the affinity of the fully functionalized A ring for inorganic species and common laboratory glassware, strategic protection would be applied on the more advanced intermediates for their ease of handling. Given the need for a scalable and economically viable route to the cardenolides and derivatives thereof, cortisone acetate (6, ca. $1/gram) was chosen as an ideal starting material. The realization of this strategy enabled the scalable synthesis of ouabagenin where all steps up to step 1 have been conducted on a gram-scale.

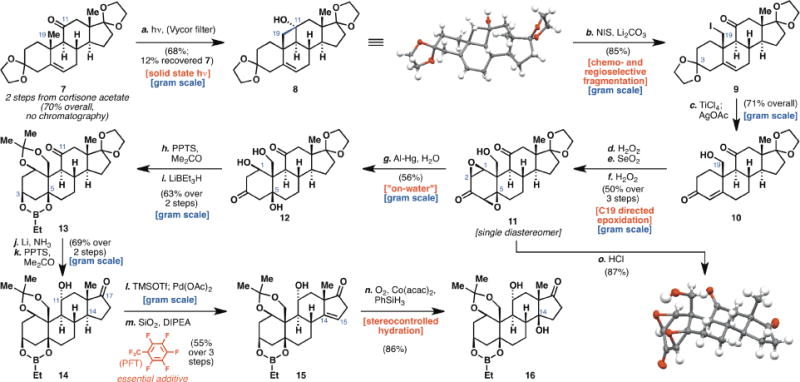

Cortisone acetate was converted to known diketal 7 employing a modified two-step sequence (19) that proceeded in 70% yield after recrystallization (Scheme 1). The first redox-relay event of the route was realized in the Norrish type II photochemical functionalization (20) of angular C19 methyl group by the C11 ketone moiety (21). Initial experimentation revealed that although desired cyclobutanol 8 could be obtained via conventional solution photochemistry, the reaction proceeded in only modest yield (See Supplementary Material) and was plagued by competitive formation of side-products, most notably from Norrish type I cleavage of C9–C11 bond of the steroidal framework. We therefore explored irradiation in the solid state–drawing inspiration from Garcia-Garibay’s work on synthesis using solid-state Norrish type I photochemistry (22, 23)–which to our delight, not only improved the yield for the cyclobutanol formation, but also led to significant suppression of side-products. Admittedly, this improvement in chemoselectivity comes with some trade-off in efficiency; the reaction took longer time to complete, presumably due to limited exposure of the solid surface area in a typical photoreaction vessel. We anticipate that the use of photochemistry in flow reactor would improve the reaction efficiency and allow this reaction to be conducted on even larger scale.

Scheme 1.

Construction of the ouabagenin core. Reagents and conditions: (a) hv, SDS solution, 120 h, 68%; (b) hv, NIS (3 equiv), Li2CO3 (3.5 equiv), MeOH, PhCH3, 23 °C, 20min, 85%; (c) TiCI4 (1 M in CH2CI2, 1 equiv), CH2CI2, −10 °C, 15 min; AgOAc (1.5 equiv), THF, 50 °C, 2 h (71% overall); (d) H2O2 (35 wt. % in H2O, 6 equiv), 3 NaOH (1 equiv), MeOH, 0 °C, 75 min; (e) SeO2 (1.1 equiv), PhCI, 90 °C, 10 h; (f) H2O2 (35 wt. % in H2O, 6 equiv), 3 M NaOH (1 equiv), MeOH, 0 °C, 75 min (50% over 3 steps); (g) Al-Hg, sat. NaHCO3, −5 °C, 1 h (56%); (h) PPTS (0.2 equiv), CaSO4 (2.5 equiv), Me2CO, 23 °C, 20 h; (i) LiBEt3H (1 M in THF, 1.1 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 30 min (63% over 2 steps); (j) Li (60 equiv), NH3, THF, −78 °C, 30 min; (k) PPTS (1.5 equiv), Me2CO, 70 °C, 16 h (69% over 2 steps); (I) TMSOTf (3 equiv), Et3N (4 equiv) CH2CI2, 0 °C to 23 °C, 30 min; Pd(OAc)2 (1.2 equiv), MeCN, 23 °C, 3 h, then FeCI3 (1 equiv), 0 °C, 10 min; (m) SiO2, DIPEA (55 equiv), C7F8, 45 min (55% over 3 steps) (n) Co(acac)2, PhSiH3 (3 equiv), O2, dioxane, 23 °C, 3 h, 86%; (o) conc. HCl (1 equiv), CH2CI2, 23 °C, 1 h, 87%.

Initial attempts to effect oxidative fragmentation (20, 24) of C11–C19 bond were met with failure and though iodide 9 could be obtained in excellent yield by the use of Barluenga’s reagent (25), the cost of the reagent proved to be a substantial drawback for large-scale operations. A more economical alternative was finally realized by employing N-iodosuccinimide as oxidant (26). This transformation is likely to proceed via the intermediacy of a transient hypoiodite species, which undergoes a chemoselective homolysis of the C11–C19 bond, followed by recombination with an iodine radical. Selective deketalization of C3 and hydrolysis of the C19 iodide moiety furnished enone alcohol 10 which was primed for the next series of relay events, where the C19 hydroxyl moiety would serve to facilitate the introduction of additional hydroxyl moieties on C1 and C5. In addition, we surmised that the angular disposition of the C19 hydroxyl moiety would also translate to a diastereoselective stereochemical relay to the β-face of the A ring. Success was eventually realized by epoxidation of the enone moiety that–in contrast to epoxidation literature on simpler C19 methyl substrates (27)–proceeded with complete facial selectivity, likely via the formation of a hydrogen-bonding network under the protic conditions of the reaction. Subjection of the resulting epoxide to dehydrogenation of the C1–C2 bond with selenium dioxide, followed by another iteration of directed epoxidation event provided diepoxide 11 in good yield. Facial selectivity of the two epoxidation events was confirmed by X-ray analysis after deketalization.

Reductive opening of diepoxide 11 proved to be the most difficult transformation to secure on scale. A gamut of conditions was surveyed (28), only to give a mixture of A ring enones as products. In our hands, triol 12 was only accessible via treatment with in situ generated aluminum amalgam (29). Preliminary trials of the use of this reagent in a mixture of organic solvent and water were beset by unsatisfactory conversion and observation of partial reduction of the epoxides (only one epoxide was cleaved and the other remained intact). After extensive optimization, we found that the use of ‘on-water’ conditions (30) was critical to obtaining satisfactory yield of triol 12. Specifically, a saturated NaHCO3 solution was found to be the optimal medium for this transformation. Following acetonide formation, the ketone moiety on C3 was reduced with LiBEt3H, which also effected a concomitant formation of the ethyl boronic ester of the two hydroxyl moieties on C1 and C5 respectively (31), thereby bypassing the need for an additional protection step. The desired α-configuration of the hydroxyl group on C11 could be accessed by employing a thermodynamic reduction (Li/NH3). Lastly, mild deketalization of C17 set the stage for the final redox-relay event.

The C17 ketone moiety so revealed rendered the C15–C16 methylene subunits amenable to dehydrogenation to furnish the conjugated enone. Initial attempts at olefin isomerization on this enone (32), however, were hampered by low conversion and significant epimerization of the C14 stereocenter which represented a dead-end as this epimer could not be converted to 15. Ultimately, we found that the use of fluorinated solvents, in particular perfluorotoluene, aided the conversion to 15 significantly, while suppressing the epimerization of the C14 center. Mukaiyama hydration (33) of the resulting olefin, while straightforward, necessitated the use of dioxane as solvent to obtain a satisfactory diastereomeric ratio of hydration products (dr = 8:1, in favor of 16). Success of this transformation marked the completion of strategically protected ouabageninone, the ketonic core of the target molecule that would enable not only the synthesis of ouabagenin, but also the versatile access to analogs varied at C17 as well as the related bufadienolide family of natural products. As a testament to the scalability of this 14-step sequence, >500 mg of this molecule has been synthesized to date.

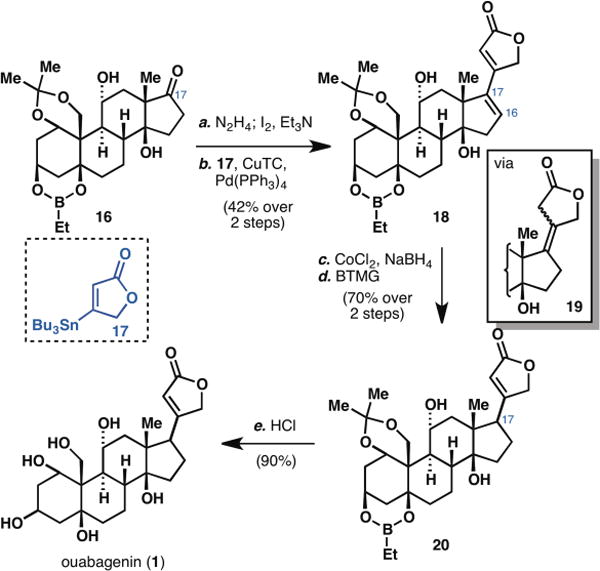

Attachment of the butenolide subunit (Scheme 2) was accomplished by first converting ketone 16 to the corresponding vinyl iodide employing Barton’s protocol (34) and then subjecting the product to a Stille cross-coupling with known stannane 17 (35). The use of Fürstner’s conditions (36) proved to be critical to deliver dienoate 18 in a synthetically useful yield. Direct reduction of the C16–C17 olefin of dienoate 18 turned out to be formidable as many conditions tried led to reduction from the convex face of the molecule. This problem was circumvented by first treating dienoate 18 with in situ generated Co2B (37) to afford exclusively tetrasubstituted olefin 19 (no reduction of C16–C17 or butenolide moiety was observed). A myriad of bases were tried to isomerize this olefin into conjugation, only to produce the wrong stereochemistry of the newly generated chiral center at C17. Ultimately, we found that heating 19 in the presence of Barton’s base delivered enoate 20 with a predominantly correct disposition of the butenolide moiety (dr = 3:1). Lastly, unmasking of all the hydroxyl groups under acidic condition delivered synthetic ouabagenin (1).

Scheme 2.

Completing the synthesis of ouabagenin. Reagents and conditions (a) N2H4 (10 equiv), Et3N (10 equiv), 4:1 CH2CI2:EtOH, 50 °C, 5 h; l2 (3 equiv), Et3N(4 equiv), THF, 10 min; (b) 17 (4 equiv), [Ph2PO2][NBu4] (4 equiv), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.15 equiv), CuTC (3 equiv), DMF, 23 °C, 2 h (42% over 2 steps); (c) CoCI2.6H2O (2.5 equiv), NaBH4 (5 equiv), EtOH, 0 to 23 °C, 20 min; (d) Barton’s base (1.5 equiv), C6H6, 100 °C, 10 min (70% over 2 steps); (e) conc. HCl (2 equiv), MeOH, 23 °C, 30 mir (90%).

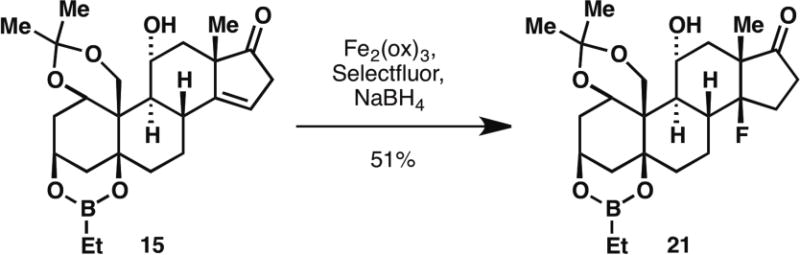

Salient features of the current route include: (i) the application of a solid-state Norrish type II photochemistry in natural product synthesis; (ii) chemoselective cyclobutanol fragmentation using an inexpensive reagent, N-iodosuccinimide; (iii) implementation of an ‘on-water’ epoxide fragmentation; (iv) a remarkably selective olefin isomerization promoted by fluorous media; (v) a highly-diastereoselective Mukaiyama hydration to furnish the requisite cis C/D ring junction; (vi) a chemoselective dienoate reduction with Co2B; and (vii) robustness and scalability of the route in an academic setting (19 steps from known compound 7, 77% average yield per step). In addition, this route is amenable to scaffold diversification: preliminary studies suggest that opposite stereochemistry of both the C3 and C11 centers is readily accessible in a controlled fashion; the isolated olefin on 15 affords a platform for versatile functionalizations, including the introduction of heteroatoms, such as fluorine, via radical-based methods (showcased in Scheme 3, 38); lastly, the late-stage Stille coupling represents yet another potential point of diversification by way of attachment of different heterocyclic domains at C17.

Scheme 3.

Late-stage functionalization of deconjugated enone. Reagents and conditions: Fe2(ox)3 (4 equiv), Selectfluor (4 equiv), NaBH4 (6.4 equiv), 3:4:2 MeCN:THF:H2O, 0 °C, 20 min (51%)

The synthesis of the highly oxidized natural product ouabagenin represented a proof of concept for the development of a retrosynthetic strategy centered solely upon the synergistic union of redox and stereochemical relays. In a similar vein to synthesis designs predicated on minimizing protecting group chemistry (39) or maximizing aspects of synthesis economy (40), the primary purpose of this work was to generate opportunities to innovate. Although the ouabagenin case study reported here is only a singular example, we anticipate that syntheses that incorporate such a strategic interplay will result in more efficient routes and inspire the invention of new methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by LEO Pharma. Bristol-Myers Squibb supported graduate fellowship to H.R., and the Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry supported a postdoctoral fellowship to Q.Z. We are grateful to Prof. Arnold Rheingold and Dr. Curtis E. Moore (UCSD) for X-ray crystallographic analysis and Dr. G. Siuzdak (TSRI) for mass spectrometry assistance.

References and Notes

- 1.Tschesche R. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1972;180:187–202. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1972.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rousseau G, Breit B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2450–2494. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson JR. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:104–110. doi: 10.1039/b415086b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishihara Y, Baran PS. Synlett. 2010;12:1733–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiesner K, Tsai TYR. Pure Appl Chem. 1986;58:799–810. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imhof R, Gössinger ME, Graf W, Berner H, Berner-Fenz Mrs L, Wehrli H. Helv Chim Acta. 1972;55:1151–1153. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19720550410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corey EJ, Hertler WR. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:5209–5212. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannis A, Heretsch P, Sarli V, Stöβel A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi J, Manolikakes G, Yeh CH, Guerrero CA, Shenvi RA, Shigehisa H, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8014–8027. doi: 10.1021/ja202103e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jana CK, Hoecker J, Woods TM, Jessen HJ, Neuburger M, Gademann K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:8407–8411. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szent-Gyorgyi A. Chemical Physiology of Contraction in Body and Heart Muscle. Academic Press; New York: 1953. pp. 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamura A, Guo J, Itagaki Y, Bell C, Wang Y, Haupert GT, Jr, Magil S, Gallagher RT, Berova N, Nakanishi K. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:6654–6659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong BC, Kim S, Kim TS, Corey EJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2711–2715. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye M, Qu G, Guo H, Guo D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;91:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Erhardt PW. J Med Chem. 1987;30:231–237. doi: 10.1021/jm00385a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) The Digitalis Investigation Group. N Eng J Med. 1997;336:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Reddy MS, Phoenix S, Deslongchamps P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1272–1275. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heasley B. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:3092–3120. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wüst F, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen JA. Steroids. 2003;68:177–191. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehrli H, Heller MS, Schaffner K, Jäger O. Helv Chim Acta. 1961;44:2162–2173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reported example of porphyrin-catalyzed, direct C19 methyl hydroxylation was found to be irreproducible in our hands:; Vijayarahavan B, Chauhan SMS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6223–6226. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng D, Yang Z, Garcia-Garibay MA. Org Lett. 2004;6:645–647. doi: 10.1021/ol0499250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selected reported examples of solid-state Norrish type II reaction:; (a) Gudmundsdottir AD, Lewis TJ, Randall LH, Scheffer JR, Rettig SJ, Trotter J, Wu C-H. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6167–6184. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuzmanich G, Vogelsberg CS, Maverick EF, Netto-Ferreira JC, Scaiano JC, Garcia-Garibay MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1115–1123. doi: 10.1021/ja2090004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wietzerbin K, Bernadou J, Meunier B. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2000;7:1391–1406. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barluenga J, González-Bobes F, Murguía MC, Ananthoju SR, González JM. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:4206–4213. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald CE, Holcomb H, Leathers T, Ampadu-Nyarko F, Frommer J., Jr Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6283–6286. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hrycko S, Morand P, Lee FL, Gabe EJ. J Org Chem. 1988;53:1515–1519. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larock RC. Comprehensive Organic Transformations. Wiley; New York: 1989. pp. 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hossain AMM, Kirk DN, Mitra G. Steroids. 1976;27:603–608. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(76)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayan S, Muldoon J, Finn MG, Fokin VV, Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3275–3279. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garlaschelli L, Mellerio G, Vidari G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Kelly RW, Sykes PJ. J Chem Soc (C) 1968:416–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Baranovskii AV, Bolibrukh DA, Gromak VV. Russ J Gen Chem. 2011;81:1877–1885. [Google Scholar]; (c) Egner U, Fritzmeier KH, Halfbrodt W, Heinrich N, Kuhnke J, Müller-Fahrnow A, Neef G, Schöllkopf K, Schwede W. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:11267–11274. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cleve A, Neef G, Ottow E, Scholz S, Schwede W. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:5563–5572. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isayama S, Mukaiyama T. Chem Lett. 1989;18:1071–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton DHR, O’Brian RE, Sternhell S. J Chem Soc. 1962:470–476. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollingworth GJ, Perkins G, Sweeney J. J Chem Soc Perkins Trans. 1996;1:1913–1919. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fürstner A, Funel JA, Tremblay M, Bouchez LC, Nevado C, Waser M, Ackerstaff J, Stimson CC. Chem Commun. 2008:2873–2875. doi: 10.1039/b805299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung SK. J Org Chem. 1979;44:1014–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barker TJ, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13588–13591. doi: 10.1021/ja3063716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baran PS, Maimone TJ, Richter JM. Nature. 2007;446:404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature05569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newhouse T, Baran PS, Hoffmann RW. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;39:3010–3021. doi: 10.1039/b821200g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.