Abstract

Importance

Previous studies of checklist-based quality improvement interventions have reported mixed results.

Objective

To evaluate whether implementation of a checklist-based quality improvement intervention, Keystone Surgery, was associated with improved outcomes in patients undergoing general surgery in large statewide population.

Design, Setting and Exposure

Retrospective longitudinal study examining surgical outcomes in Michigan patients using Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative clinical registry data from the years 2006–2010 (n=64,891 patients in 29 hospitals). Multivariable logistic regression and difference-in-differences analytic approaches were used to evaluate whether Keystone Surgery program implementation was associated with improved surgical outcomes following general surgery procedures, apart from existing temporal trends toward improved outcomes during the study period.

Main Outcome Measures

Risk-adjusted rates of superficial surgical site infection, wound complications, any complication, and 30-day mortality.

Results

Implementation of Keystone Surgery in participating centers (n=14 hospitals) was not associated with improvements in surgical outcomes during the study period. Adjusted rates of superficial surgical site infection (3.2 vs. 3.2%, p=0.91), wound complications (5.9 vs. 6.5%, p=0.30), any complication (12.4 vs. 13.2%, p=0.26), and 30-day mortality (2.1 vs. 1.9%, p=0.32) at participating hospitals were similar before and after implementation. Difference-in-differences analysis accounting for trends in non-participating centers (n=15 hospitals), and sensitivity analysis excluding patients receiving surgery in the first 6- or 12-months after program implementation yielded similar results.

Conclusions and Relevance

Implementation of a checklist-based quality improvement intervention did not impact rates of adverse surgical outcomes among patients undergoing general surgery in participating Michigan hospitals. Additional research is needed to understand why this program was not successful prior to further dissemination and implementation of this model to other populations.

INTRODUCTION

There is widespread enthusiasm for the use of checklists to improve hospital outcomes.1–4 Perhaps one of the most widely known and successful examples is the Keystone ICU Patient Safety Program. This intervention utilized a checklist emphasizing evidence-based processes of care and a program to improve safety culture5 to dramatically decrease rates of catheter-related bloodstream infection6 and ventilator-associated pneumonia7 in Michigan. The program has since been implemented nationally,8 and similar programs have expanded to other patient populations. One such expansion was "Keystone Surgery", a Michigan program designed to reduce rates of surgical site infection and other adverse surgical outcomes.9

The effectiveness of checklist-based interventions to improve surgical outcomes is still unclear, however. Recent work by Urbach and colleagues failed to report an association between implementation of surgical safety checklists and improved outcomes in a large population.10 Previous evaluations of programs directed toward surgical site infection specifically have been limited to small cohorts and single institutions,11–15 and no studies have utilized a concurrent control group to assess effectiveness.16 Though previous studies have demonstrated that the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP) process measures used in Keystone Surgery are not associated with improved outcomes,17, 18 none have evaluated these processes when coupled with a program to improve safety culture. Given the substantial resources necessary to implement interventions like Keystone Surgery, establishing their effectiveness as part of efforts to advance the science and improve patient care is paramount.

In this study, we capitalize on a unique natural experiment to evaluate the effect of Keystone Surgery on general surgery outcomes in a large statewide population. We used five years of clinical registry data to examine outcomes before and after implementation of the Keystone Surgery program. To account for secular trends in the state, we compared this cohort to a control group of patients undergoing surgery during the same period at Michigan hospitals that did not implement the program.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Population

This study was completed using clinical registry data from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC), a regional consortium of 52 hospitals funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/The Blue Care Network. Details of data collection have been previously published.19, 20 Clinical nurse reviewers collect patient characteristic, intraoperative processes, and 30-day outcomes data for patients undergoing general and specialty surgery throughout the state, using a standard 8-day case sampling strategy.21 Annual nurse reviewer and data audits ensure data accuracy. For this study, we identified all patients undergoing general surgery procedures at MSQC hospitals from 2006 to 2010 using relevant Current Procedural Terminology codes. We chose inpatient procedures that account for the vast majority of postoperative infections: abdominal exploration and lysis of adhesions, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, colorectal resection, ventral hernia repair, bariatric surgery, pancreatic resection, esophagectomy, gastrectomy, fundoplication, peptic ulcer surgery, liver resection, biliary reconstruction, pelvic exenteration, small bowel operations, and splenectomy.

Keystone Surgery

The Keystone Surgery program was a prospective cohort intervention implemented within specialty-specific surgical teams at participating Michigan Health & Hospital Association (MHA) hospitals, with a goal of improving surgical care throughout the state. Hospitals volunteered to participate and did not receive financial support. Implementation occurred over a two-year period, using a stepped-wedge design.22 The majority of MHA hospitals (n=76) enrolled during April 2008, while a second group (n=25) enrolled in April 2009. Within each hospital, a surgeon, anesthesiologist, and operating room nurse were designated as operative team leaders. Throughout the program, monthly coaching calls and semi-annual collaborative meetings were used to support the implementation process.

Similar to the Keystone ICU program, the Keystone Surgery program utilized two principal components (Table 1): a novel model to translate evidence into practice,23 and the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) to improve safety culture.24 The evidence-based practice component utilized a checklist tool that focused on compliance with six Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services SCIP processes: appropriate prophylactic antibiotic use (selection, timing, and discontinuation), appropriate hair removal, maintenance of perioperative normothermia, and glucose control.25–28 At the start of implementation, operative teams were provided with supporting materials and references to educate staff. Throughout the program, teams were encouraged to implement the tool during briefings and debriefings surrounding every procedure, and to monitor compliance, adapt the tool based on local needs, and work together to resolve issues that surfaced during the process.29, 30

Table 1.

Brief Description of the Keystone Surgery Program.

| Intervention component | Content | Program Support |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence-based Practice23 Checklist tool describing Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP) processes |

Six SCIP processes: Appropriate Antibiotic Use:

|

Educational materials provided Routine briefings and debriefings among surgical teams encouraged Principles of safety science enforced |

|

Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP)5, 24 5-step iterative process to improve teamwork and safety culture |

|

Team leaders encouraged to participate in:

|

The CUSP is an iterative 5-step process previously validated to improve teamwork and safety culture (Table 1).5, 24 Through these steps, the program attempts to educate participants on the principles of safety science, identify defects, increase communication between frontline providers and senior leadership, encourage learning from identified defects, and implement tools to assist the quality improvement process. At initiation, and annually thereafter, a validated assessment of culture was performed to support and guide the program.31

Within the 34 MSQC study hospitals, 10 hospitals implemented the program before May 1st, 2008, two hospitals implemented the program on June 1st 2009, one on December 1st, 2009, and one on January 1st, 2010. Fifteen hospitals did not implement the program, and 5 hospitals that implemented Keystone Surgery prior to joining MSQC were excluded. For this analysis, hospitals were divided into two groups: hospitals that implemented the Keystone Surgery program (Keystone hospitals), and those that did not (Non-Keystone hospitals). Patients undergoing a procedure at Keystone hospitals prior to the specified date of implementation were considered "pre-implementation," while patients undergoing a procedure after that date were considered "post-implementation." Because the vast majority of Keystone hospitals implemented the program on or before May 1st, 2008, patients undergoing procedures at Non-Keystone hospitals were considered "post-implementation" if they received surgery after May 1st, 2008.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcomes of this analysis included superficial surgical site infection, any wound complication (superficial, deep, or organ-space surgical site infection, or wound disruption), any complication, and death within 30 days of operation. Additional complications recorded in the MSQC registry include: acute kidney injury, intraoperative or post-operative transfusion, cardiac arrest requiring resuscitation, coma lasting >24 hours, superficial or deep venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, prolonged ventilation lasting >48 hours, peripheral nerve injury, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, renal insufficiency, stroke, sepsis, septic shock, unplanned intubation, and urinary tract infection.

Statistical Analysis

We performed two distinct analyses to evaluate the impact of Keystone Surgery on surgical outcomes: a pre-post analysis and a difference-in-differences analysis. For the pre-post analysis, we assessed patients undergoing surgery at hospitals that implemented Keystone Surgery. We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the relationship between our primary outcomes and program implementation. Each model included a variable indicating whether patients at keystone hospitals had surgery before program implementation ("pre-implementation"), or after ("post-implementation"). To further evaluate the effect of the program on outcomes following specific procedures, we stratified analyses by the four most common operations: cholecystectomy, colorectal resection, appendectomy, and ventral hernia repair.

We then used a difference-in-differences analysis to account for coincident temporal trends towards improved outcomes among all study hospitals. This econometric technique, frequently used to evaluate the effect of policy changes,32–34 utilizes a control group to isolate changes in outcomes associated with an intervention apart from changes observed in the control. Our control group included MSQC hospitals that did not participate in Keystone Surgery, as they were exposed to all factors driving improved outcomes during the period except the intervention. In addition to the post-implementation variable, this model included a dichotomous variable indicating whether the hospital implemented Keystone Surgery, as well as the interaction of this variable and the post-implementation variable. The odds ratio from this interaction term (i.e. the difference-in-differences estimator) can be interpreted as the independent effect of Keystone Surgery implementation on surgical outcomes.35, 36

In all models, we adjusted for patient characteristics, comorbidities, and details of the procedure. Patient characteristics included age, gender, race, and their interactions. Comorbidities included American Society of Anesthesiologists class, diabetes, smoking status, dyspnea, do-not-resuscitate status, functional status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, hemodialysis, hemiplegia, transient ischemic attack, disseminated cancer, prior myocardial infarction, angina, hypertension requiring medication, peripheral vascular disease, prior operations and impaired sensorium. Procedure details included emergency status, operative approach, and procedure type. To account for within-hospital outcome correlation (clustering), we generated robust standard errors.

We performed sensitivity analyses to account for variability in program compliance during the initial phase of implementation. For the Keystone ICU Patient Safety program, investigators estimated that implementation would take less than 6 months.6 Therefore we performed two pre-post analyses after excluding patients who underwent surgery during the first 6- or 12-months following program implementation.

Risk-adjusted outcome rates were determined by calculating marginal effects for each model. C-statistics for the models ranged from 0.74 (SSI) to 0.95 (30-day mortality). For all statistical tests, p-values are two-tailed, and alpha is set at 0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was determined not regulated by the Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Our study cohort consisted of 64,891 patients in 29 hospitals. Fourteen hospitals implemented Keystone Surgery during the study period. In these hospitals, 14,005 patients underwent surgery before, and 14,801 patients underwent surgery after program implementation. A total of 36,085 patients underwent surgery at Non-Keystone hospitals. Patient and operative characteristics are shown in Table 2. In Keystone hospitals, patients undergoing surgery before and after implementation were generally similar in all characteristics and comorbidities. Small differences were present in the proportion of female patients, African-American patients, and emergency procedures. Patients undergoing surgery at Non-Keystone hospitals were also generally similar across categories (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients undergoing surgery at Keystone and Non-Keystone hospitals during the years 2006 to 2010 (All variables are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise noted).

| Patient Characteristics | Patients undergoing general surgery at Keystone hospitals |

Patients undergoing general surgery at Non-Keystone hospitals |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Implementation |

Post- Implementation |

|||

| Number of patients, N | 14,005 | 14,801 | 36,085 | |

| Age (Mean ± SD), y | 52.1 ± 17.6 | 53.7 ± 17.6 | 53.6 ± 17.9 | |

| Female | 8,731 (62.3) | 8,968 (60.6) | 21,996 (70.0) | |

| African-American race | 2,164 (15.4) | 1,905 (12.9) | 4,455 (12.4) | |

| Laparoscopic Approach | 7,397 (52.8) | 7,821 (52.8) | 17,834 (49.4) | |

| Emergent | 2,684 (19.2) | 3,149 (21.3) | 7,007 (19.4) | |

| ≥ 3 Comorbidities | 1,752 (12.5) | 1,974 (13.3) | 5,624 (15.6) | |

| ASA Class (Median) | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Procedure type | ||||

| Cholecystectomy | 3,786 (27.0) | 3,003 (20.3) | 8,668 (24.0) | |

| Colorectal Resections | 2,604 (18.6) | 3,119 (21.1) | 7,782 (21.5) | |

| Appendectomy | 1,924 (13.7) | 2,241 (15.1) | 5,176 (14.3) | |

| Bariatric Surgery | 2,055 (14.7) | 2,057 (13.9) | 3,627 (10.0) | |

| Ventral Hernia Repair | 1,609 (11.5) | 2,026 (13.7) | 4,999 (13.8) | |

| Other General Surgery | 2,027 (14.5) | 2,355 (15.9) | 5,833 (16.2) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 6,111 (43.6) | 6,904 (46.6) | 16,559 (45.9) | |

| Smoker | 3,133 (22.4) | 3,351 (22.6) | 8,250 (22.9) | |

| Diabetes | 2,030 (14.5) | 2,402 (16.2) | 5,669 (15.7) | |

| Dyspnea | 1,801 (12.9) | 2,033 (13.7) | 6,986 (19.4) | |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 1,158 (8.3) | 1,328 (9.0) | 3,565 (9.9) | |

| Dependent Functional Status | 718 (5.1) | 869 (5.9) | 2,190 (6.07) | |

| TIA or Cerebrovascular Accident | 718 (5.1) | 834 (5.6) | 1,991 (5.5) | |

| COPD | 626 (4.5) | 766 (5.2) | 1,862 (5.2) | |

| Prior Operations | 329 (2.4) | 297 (2.0) | 783 (2.2) | |

| Cancer | 300 (2.1) | 286 (1.9) | 709 (2.0) | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 191 (1.4) | 231 (1.6) | 516 (1.4) | |

| Renal Failure or Dialysis | 216 (1.5) | 247 (1.7) | 602 (1.7) | |

| CHF | 162 (1.2) | 113 (0.7) | 382 (1.1) | |

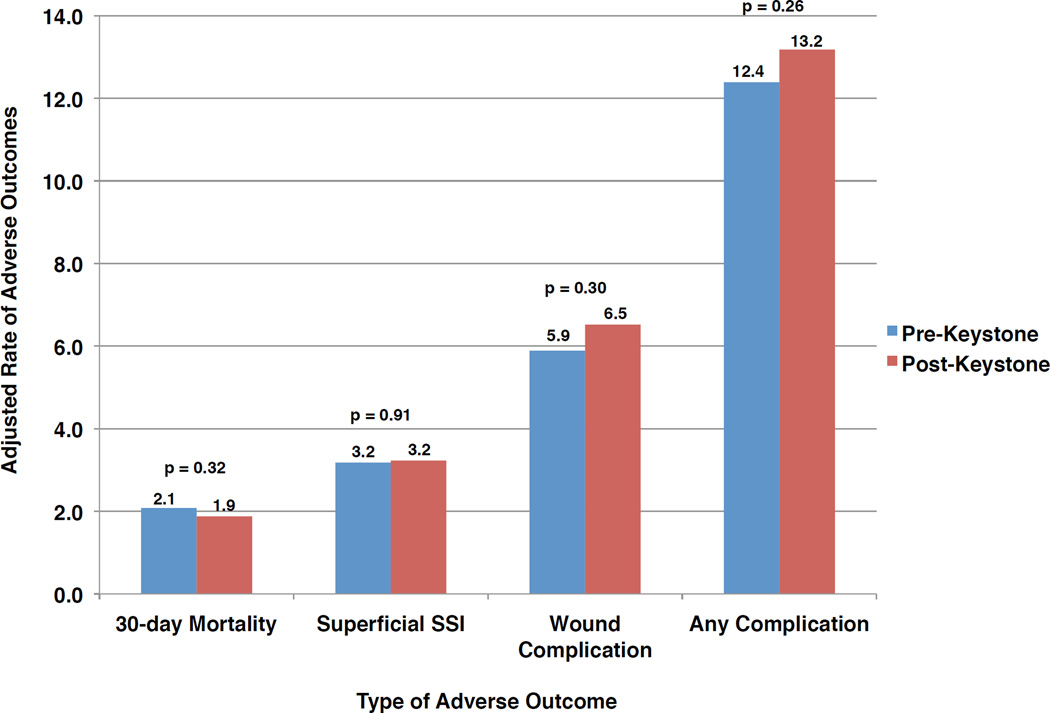

Risk-adjusted outcomes in the fourteen Keystone hospitals pre- and post-program implementation are shown in Figure 1. No significant differences were seen in adjusted rates of any adverse outcome before vs. after implementation of Keystone Surgery: 30-day mortality (2.1 vs. 1.9%, p=0.32); superficial surgical site infection (3.2 vs. 3.2%, p=0.91); wound complication (5.9 vs. 6.5%, p=0.30); and any complication (12.4 vs. 13.2%, p=0.26). Similarly, adjusted adverse outcome rates did not differ significantly before or after Keystone Surgery implementation when stratified by procedure type (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Adjusted rates of adverse outcomes in Keystone hospitals before and after implementation of Keystone Surgery (SSI: surgical site infection)

Table 3.

Adjusted rates of adverse outcomes in colorectal resection, ventral hernia repair, appendectomy, and cholecystectomy performed in Keystone hospitals before and after implementation of Keystone Surgery (SSI: surgical site infection).

| Adverse Outcome | Adjusted rate in Keystone hospitals | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Implementation | Post-Implementation | |||

| Colorectal Resection | ||||

| Superficial SSI (%) | 6.9 | 6.5 | 0.76 | |

| Wound Complication (%) | 12.0 | 13.4 | 0.42 | |

| Any Complication (%) | 25.3 | 26.8 | 0.42 | |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 4.5 | 4.1 | 0.38 | |

| Ventral Hernia Repair | ||||

| Superficial SSI (%) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.47 | |

| Wound Complication (%) | 4.7 | 4.8 | 0.91 | |

| Any Complication (%) | 7.0 | 8.2 | 0.43 | |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.16 | |

| Appendectomy | ||||

| Superficial SSI (%) | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.37 | |

| Wound Complication (%) | 3.2 | 4.3 | 0.25 | |

| Any Complication (%) | 5.2 | 6.0 | 0.38 | |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Cholecystectomy | ||||

| Superficial SSI (%) | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.31 | |

| Wound Complication (%) | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.20 | |

| Any Complication (%) | 4.3 0.8 |

4.4 0.5 |

0.84 | |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 0.079 | |||

Table 4 shows the odds of adverse outcomes pre- and post-implementation of the Keystone Surgery program in participating hospitals. No association was present between adjusted odds of adverse outcomes and Keystone Surgery implementation: 30-day mortality [OR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.68–1.14]; superficial surgical site infection [OR 1.02, 95% CI: 0.76–1.36]; wound complication [OR 1.12, 95% CI: 0.90–1.40]; or any complication [OR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.94–1.27]. Difference-in-differences models accounting for competing time trends during the study period did not change these results (Table 4). Sensitivity analysis excluding patients undergoing surgery within 6- or 12- months of the start of Keystone Surgery implementation also yielded similar results.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds of adverse outcomes at Keystone hospitals, and in the entire cohort, after Keystone Surgery implementation compared to before (SSI: surgical site infection; CI: confidence interval).

| Adverse Outcome | Pre-Post analysis (Keystone hospitals) |

Difference-in- differences analysis (Entire study cohort) |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Superficial SSI | 1.02 (0.76 – 1.36) | 1.06 (0.77 – 1.46) |

| Any Wound Complication | 1.12 (0.90 – 1.40) | 1.19 (0.95 – 1.50) |

| Any Complication | 1.09 (0.94 – 1.27) | 1.10 (0.89 – 1.36) |

| 30-day Mortality | 0.88 (0.68 – 1.14) | 0.84 (0.58 – 1.21) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we perform a controlled evaluation of a checklist-based quality improvement intervention — Keystone Surgery — that focused on reducing surgical site infections. We were unable to find a significant association between program implementation and adjusted rates of superficial surgical site infection, wound complication, any complication, and 30-day mortality in patients undergoing general surgery in participating hospitals. This finding was robust across multiple analyses, including a difference-in-differences analysis, stratified analyses of the most common operations, and sensitivity analyses excluding patients undergoing surgery in the first 6- or 12-months after program implementation.

Previous studies evaluating checklist-based interventions have reported mixed results.11–13, 15 For example, Hendrick et al. reported a decrease in surgical site infection rates at a single institution from 25.6% to 15.9% over two years following implementation of a checklist-based intervention in colorectal surgery patients,11 while Forbes and colleagues reported a non-significant decrease in rates following a similar intervention,12 and Anthony et al. reported an increase in rates following a single-center randomized trial.13 While a recent meta-analysis examining the effects of the World Health Organization surgical safety checklist reported a significant association with improved outcomes,16 the individual studies reviewed were heterogeneous and reported widely mixed results. Furthermore, no studies examined in the meta-analysis utilized a control group to isolate the effect of the checklist from coincident secular trends toward improved outcomes.

Our study goes beyond this current literature in several important ways. First, we evaluated a diverse statewide population of patients undergoing surgery in many hospitals representing diverse sizes, teaching statuses and affiliations. Second, our analysis included a control group of hospitals not participating in the program, to isolate the effect of the intervention from secular trends toward improved outcomes during the study period. When compared to previous work, these findings highlight the importance of accurate risk-adjustment and control cohorts when evaluating effectiveness, and are corroborated by similar evaluations of other programs. Benning and colleagues, for example, found that although care improved in United Kingdom hospitals during the Health Foundation's Safer Patients Initiative, there was no additional effect beyond that seen in control hospitals.37

This study has multiple limitations. First, use of data from the MSQC limits the study cohort to a subset of Michigan hospitals participating in a statewide organization collaborating for quality improvement. Though use of this clinical registry allowed rigorous adjustment of patient characteristics, it precluded evaluation of the Keystone Surgery program in other MHA hospitals not participating in the collaborative. Nevertheless, MSQC hospitals provide the vast majority of surgical care delivered in Michigan.38 Furthermore, no systematic prospective quality improvement initiatives targeting superficial surgical site infection beyond outcomes measurement and feedback were implemented during the study period. Second, because we lack detail regarding program compliance at individual hospitals, we cannot explain why the program did not improve outcomes in these hospitals. Finally, hospitals participating in Keystone Surgery volunteered to participate, which may have introduced selection bias. However, these latter imitations do not reduce the internal validity of this study, as this analysis was not designed to evaluate the details of implementation, but instead examine program effectiveness as it was implemented.

Ultimately a more comprehensive evaluation will be necessary to understand why Keystone Surgery failed to impact surgical outcomes. There are two possible reasons the program did not have its intended effect. First, Keystone Surgery may have failed because it encouraged adherence to processes that are not strongly associated with outcomes.17, 18, 39 However, this study adds to the current literature on SCIP measures by showing the addition of a previously-validated process to improve teamwork and safety culture (CUSP) to SCIP measure processes did not enhance their effectiveness.

A second possible explanation is a failure of the implementation process. Successful implementation of clinical interventions depends on not only high-quality evidence, but also a receptive environment and facilitation.40 The Keystone ICU program, for example, was implemented in intensive care units, utilized small teams of nurses and advanced providers, and focused on a single procedure. In contrast, the Keystone Surgery program was implemented in the operating room on a heterogeneous group of complex procedures, and engaged diverse teams that underwent frequent personnel changes. It would not be surprising if this increased complexity created an environment less conducive to successful implementation. Moreover, surgical site infections are diverse and complex complications, and it is less likely a single bundle of interventions can be successfully applied across organizations. Another notable difference between the Keystone Surgery and ICU programs was that for Keystone Surgery, many participating sites lacked infrastructure for data collection and outcome feedback to frontline teams — a key attribute of successful improvement efforts.41

Regardless of the underlying cause, the lack of effectiveness observed following Keystone Surgery implementation requires providers to reevaluate how such interventions are designed. Lessons learned from use of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program in Keystone Surgery were subsequently incorporated into the development of a similar program — Surgical Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program — that was successfully implemented at a single institution in July of 2011.42 First, instead of using SCIP process measures, researchers used input from providers to identify local defects with the greatest potential to prevent surgical site infections. Second, during the program, process measures were objectively audited (e.g. post-operative temperature was measured to ensure patients were normothermic), rather than giving credit for process compliance per se (e.g. the current SCIP temperature control measure gives credit for a warming blanket regardless of a patient’s temperature). Focused efforts to address and mitigate local defects were associated with reductions in surgical site infection rates following colorectal surgery from 27.3% to 18.2% over a two-year period.42

In this study, we report an evaluation of a checklist-based quality improvement intervention focused on a statewide population of surgery patients. We found that the Keystone Surgery program was not associated with improvements in adjusted rates of adverse outcomes, regardless of the cohort evaluated or the methodology used. It is unclear whether this was due to a failure of evidence or implementation. Though reasons are likely multifactorial, the experience gained through completion of Keystone Surgery resulted in valuable lessons for implementation of future programs. Going forward, evaluations of similar programs should incorporate both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to better understand how implementation influences outcomes.43 Given the resources necessary to widely implement programs like Keystone Surgery, it is essential that researchers assess clinical effectiveness prior to broad dissemination. This study illustrates that success of a program in one clinical context may not translate to others. Instead, each program must be evaluated individually to determine its true clinical effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Reames is supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (5T32CA009672-23). Dr. Dimick is supported by grant from Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding sponsors played no part in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The sponsors had no access to the data and did not perform any of the study analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Reames had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Dimick reports serving as consultant and having an equity interest in ArborMetrix Inc, which provided software and analytics for measuring hospital quality and efficiency. The company had no role in the study. Dr. Campbell is Program Director for the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative. Drs. Reames and Krell have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hales BM, Pronovost PJ. The checklist--a tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care. 2006 Sep;21(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 29;360(5):491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawande A. The Checklist: If something so simple can transform intensive care, what else can it do? The New Yorker. 2007:86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, et al. Association Between Implementation of a Medical Team Training Program and Surgical Mortality. Jama. 2010;304(15):1693. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sexton JB, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, et al. Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2011 May;39(5):934–939. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d26c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 28;355(26):2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, et al. Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011 Apr;32(4):305–314. doi: 10.1086/658938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ending Health Care-Associated Infections. [Accessed August 20th, 2013];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2010 Oct; http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/errorssafety/haicusp/index.html.

- 9.MHA Keystone: Surgery. [Accessed March 28th, 2014];MHA Keystone Center. http://www.mhakeystonecenter.org/collaboratives/surgery.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbach DR, Govindarajan A, Saskin R, Wilton AS, Baxter NN. Introduction of surgical safety checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 13;370(11):1029–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1308261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedrick TL, Heckman JA, Smith RL, Sawyer RG, Friel CM, Foley EF. Efficacy of protocol implementation on incidence of wound infection in colorectal operations. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 Sep;205(3):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forbes SS, Stephen WJ, Harper WL, et al. Implementation of evidence-based practices for surgical site infection prophylaxis: results of a pre- and postintervention study. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 Sep;207(3):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anthony T, Murray BW, Sum-Ping JT, et al. Evaluating an evidence-based bundle for preventing surgical site infection: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2011 Mar;146(3):263–269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crolla RM, van der Laan L, Veen EJ, Hendriks Y, van Schendel C, Kluytmans J. Reduction of surgical site infections after implementation of a bundle of care. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cima R, Dankbar E, Lovely J, et al. Colorectal surgery surgical site infection reduction program: a national surgical quality improvement program--driven multidisciplinary single-institution experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Jan;216(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergs J, Hellings J, Cleemput I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of the World Health Organization surgical safety checklist on postoperative complications. Br J Surg. 2014 Feb;101(3):150–158. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, et al. Association of surgical care improvement project infection-related process measure compliance with risk-adjusted outcomes: implications for quality measurement. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Dec;211(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawn MT, Vick CC, Richman J, et al. Surgical site infection prevention: time to move beyond the surgical care improvement program. Ann Surg. 2011 Sep;254(3):494–499. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c6929. discussion 499–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Englesbe MJ, Dimick JB, Sonnenday CJ, Share DA, Campbell DA., Jr The Michigan surgical quality collaborative: will a statewide quality improvement initiative pay for itself? Ann Surg. 2007 Dec;246(6):1100–1103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c3fe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell DA, Jr, Englesbe MJ, Kubus JJ, et al. Accelerating the pace of surgical quality improvement: the power of hospital collaboration. Arch Surg. 2010 Oct;145(10):985–991. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J, et al. The patient safety in surgery study: background, study design, and patient populations. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 Jun;204(6):1089–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmel J, Kent PS, Holzmueller CG, Paine L, Schulick RD, Pronovost PJ. Impact of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) on safety culture in a surgical inpatient unit. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010 Jun;36(6):252–260. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bratzler DW, Hunt DR. The surgical infection prevention and surgical care improvement projects: national initiatives to improve outcomes for patients having surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Aug 1;43(3):322–330. doi: 10.1086/505220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clancy CM. SCIP: making complications of surgery the exception rather than the rule. AORN J. 2008 Mar;87(3):621–624. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stulberg JJ. Adherence to Surgical Care Improvement Project Measures and the Association With Postoperative Infections. Jama. 2010;303(24):2479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Details for Demonstration Project Name: Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration. [Accessed November 14, 2013];Medicare Demonstration Projects & Evaluation reports. http://go.cms.gov/19oWDYZ.

- 29.Berenholtz SM, Schumacher K, Hayanga AJ, et al. Implementing standardized operating room briefings and debriefings at a large regional medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009 Aug;35(8):391–397. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandari J, Schumacher K, Simon M, et al. Surfacing safety hazards using standardized operating room briefings and debriefings at a large regional medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 Apr;38(4):154–160. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wooldridge JM. Introductory econometrics : a modern approach. 4th ed. Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colla CH, Wennberg DE, Meara E, et al. Spending differences associated with the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration. JAMA. 2012 Sep 12;308(10):1015–1023. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications before vs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013 Feb 27;309(8):792–799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donald SGLK. Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat. 2007;89:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan AM. Effects of the Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration on Medicare patient mortality and cost. Health Serv Res. 2009 Jun;44(3):821–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benning A, Ghaleb M, Suokas A, et al. Large scale organisational intervention to improve patient safety in four UK hospitals: mixed method evaluation. Bmj. 2011;342:d195–d195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d195. (feb03 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Member Hospitals. [Accessed December 1st, 2013];Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative Homepage. http://www.msqc.org/membership_hospitals.php. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pastor C, Artinyan A, Varma MG, Kim E, Gibbs L, Garcia-Aguilar J. An increase in compliance with the Surgical Care Improvement Project measures does not prevent surgical site infection in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Jan;53(1):24–30. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181ba782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2010;5:82. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011 Apr;30(4):636–645. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wick EC, Hobson DB, Bennett JL, et al. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Aug;215(2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012 Mar;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]