Abstract

Differences in sex pheromone component can lead to reproductive isolation. The sibling noctuid species, Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta, share the same two sex pheromone components, Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald, but in opposite ratios, providing an typical example of such reproductive isolation. To investigate how the ratios of the pheromone components are differently regulated in the two species, we sequenced cDNA libraries from the pheromone glands of H. armigera and H. assulta. After assembly and annotation, we identified 108 and 93 transcripts putatively involved in pheromone biosynthesis, transport, and degradation in H. armigera and H. assulta, respectively. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, phylogenetic, and mRNA abundance analyses suggested that some of these transcripts involved in the sex pheromone biosynthesis pathways perform. Based on these results, we postulate that the regulation of desaturases, KPSE and LPAQ, might be key factor regulating the opposite component ratios in the two sibling moths. In addition, our study has yielded large-scale sequence information for further studies and can be used to identify potential targets for the bio-control of these species by disrupting their sexual communication.

In insects, species-specific behaviours elicited by sex pheromones play a key role in reproduction and are associated with reproductive isolation1. The regulation of sex pheromone-related enzymes lead to speciation by changing mate recognition systems. In moths, most sex pheromones components are C10–C18 long-chain unsaturated alcohols, aldehydes or acetate esters that are produced de novo via a modified fatty-acid biosynthesis pathway in the sex pheromone glands (PGs) by acetylation, desaturation, chain shortening, reduction, and oxidation either separately or in combination2,3. Different combinations of these reactions produce unique species-specific pheromone blends in different species.

Sex pheromone biosynthesis in moths starts with the production of the saturated fatty-acid precursor, malonyl-CoA, from acetyl-CoA and is catalysed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FAS)4. Then, the fatty chain is modified to introduce a double bond by specific desaturases (DESs), and shorted by β-oxidation5. Thus far, six types of DES have been functionally characterized, including Δ56, Δ67, Δ98, Δ119, Δ10–1210, and Δ1411. After the production and release of the sex pheromone components by females, the pheromone molecules are captured by odorant binding proteins (OBPs)12,13,14 or chemosensory proteins (CSPs)15 and transported to membrane-bound olfactory receptors (ORs)16,17,18. After OR activation, the pheromone molecules are rapidly removed by odorant degrading enzymes (ODEs), such as carboxylesterase19 and aldehyde oxidases (AOXs)20 to restore the sensitivity of the sensory neuron. Analysing these genes involved in the production of specific pheromone components will provide insights into the regulation of the pheromone component and thereby the evolution of moth sexual communication.

The lepidopterans, Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta are two sympatric sibling species that are morphologically indistinguishable in the egg, larval, and pupal stages21. Furthermore, these two species share the common sex pheromone components, Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald, but the ratios between the two components is completely reversed22,23, 100:7 in H. armigera and 7:100 in H. assulta. It is plausible that this difference likely contributes to the reproductive isolation of the two species. Some studies have been carried out to explore the regulatory mechanisms that determine these species-specific ratios22, but the mechanisms remains not well known especially from the molecular perspective. Therefore, we constructed and sequenced cDNA libraries from the PGs isolated from H. armigera and H. assulta to investigate the genetic factors associated with sex pheromone biosynthesis in these two species.

After analysis, we identified 108 and 93 putative pheromone biosynthesis, transport, and degradation transcripts in the PGs of H. armigera and H. assulta, respectively. Our results together with previous studies22,24 support the conjecture that the regulation of DESs is likely to play an important role in determining the opposite sex pheromone components ratios in the two species. In addition, our results also provide large-scale sequence information for further studies and identification of potential targets to disrupt sexual communication in H. armigera and H. assulta for the control of these lepidopterans.

Results

Overview of the PG transcriptomes

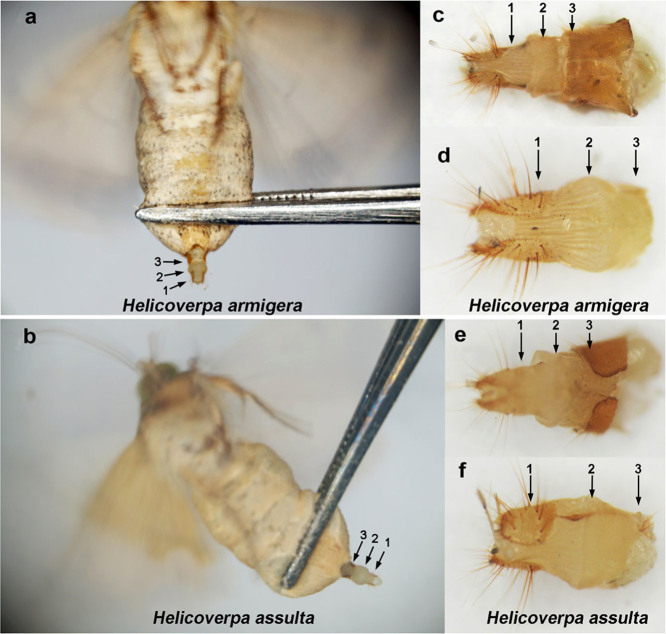

PGs from H. armigera and H. assulta were collected as previously described for the Heliothis virescens PG transcriptome25 (Fig. 1) followed by construction of the corresponding cDNA libraries. Large-scale transcripts were assembled and annotated in the PG transcriptomes from H. armigera and H. assulta (Supplementary Table S1 online).

Figure 1. Dissection of Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta sex pheromone glands.

The pheromone glands in H. armigera (a) and H. assulta (b) were squeezed out from the abdomen using forceps (the gland is similarly inflated when the female calls). The abdomen of H. armigera (c) and H. assulta (e) were cut at the sclerotized cuticle from the 8th abdominal segment, and the sclerotized cuticle was removed (H. armigera (d) and H. assulta (f)) before immersing the glands in liquid nitrogen. 1: Sclerotized ovipositor valves; 2: Pheromone gland; 3: Sclerotized cuticle that was removed.

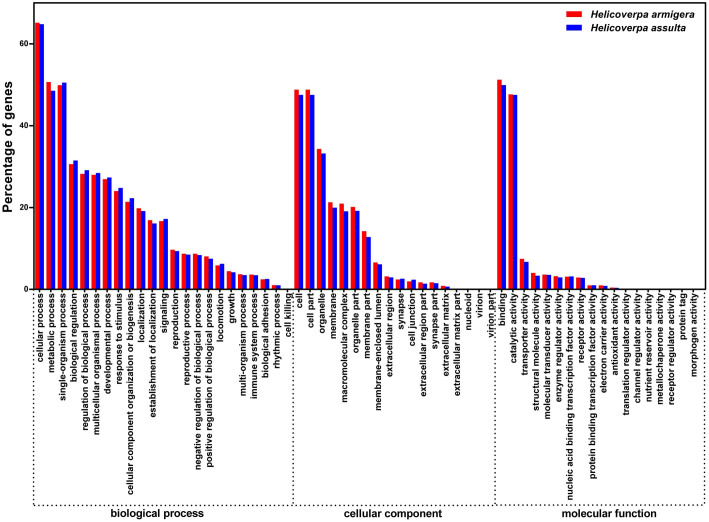

GO annotation was used to classify the PG transcripts into functional categories. GO terms were represented in all three major GO categories: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. The most represented sub-category in the biological process category was cellular process, in the cellular component category it was cell and cell part, and in the molecular functions category, binding and catalytic activity were the most represented (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of transcripts in Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta pheromone glands.

All transcripts were annotated using Gene Ontology and their distribution in the three major GO categories is shown. The analysis was at level 3.

Identification of putative genes involved in pheromone biosynthesis, transport, and degradation in the two Helicoverpa species

After removal of repetitive sequences following blastX against the NCBI Nr database and alignment with ClustalX 2.0, we identified a total of 108 and 93 putative transcripts involved in the pheromone biosynthesis, transport, and degradation in H. armigera and H. assulta PGs, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). These transcripts belonged to gene families represented by multiple transcripts in these two moth species. For example, ACC had 2 members in the 2 species each, alcohol dehydrogenase (ALR) was represented by 17 and 18 sequences in H. armigera and H. assulta, DES with 7 and 8, FAS with 3 and 3, FAR with 18 and 13, CSP with 19 and 16, OBP with 26 and 23, aldehyde dehydrogenase (AD) with 9 and 6, and AOX with 7 and 4 members respectively, in H. armigera and H. assulta (Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Tables S2–S5 online).

Table 1. BLASTX results for candidate sex pheromone biosynthesis transcripts in Helicoverpa armigera pheromone glands.

| Transcript | Best Blastp Match | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | ID | ORF | RPKM | Name | Species | E-value | Identity | Acc. number |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) | ||||||||

| ACC1 | CL1009-1 | 1356 | 0.4 | acetyl-CoA carboxylase-like | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 88% | XP_004930758 |

| ACC2 | CL1295-1 | 5211 | 40.9 | acetyl-coA carboxylase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 95% | AGR49308 |

| Aldo-Ketose Reductase (ALR) | ||||||||

| ALR1 | CL2516-1 | 1077 | 10.5 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Aedes aegypti | 1E-173 | 67% | XP_001655101 |

| ALR2 | CL3786-1 | 420 | 323.6 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 1E-38 | 57% | XP_004922743 |

| ALR3 | CL4692-1 | 918 | 23.2 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 5E-165 | 71% | XP_004922743 |

| ALR4 | CL5008-1 | 312 | 8.9 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 5E-26 | 55% | AGQ45607 |

| ALR5 | CL5271-5 | 1002 | 41.2 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 1E-73 | 52% | AGQ45607 |

| ALR6 | CL5277-1 | 682 | 112.4 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 3E-102 | 66% | EHJ65258 |

| ALR7 | CL5878-1 | 306 | 8.8 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 5E-50 | 79% | AGQ45610 |

| ALR8 | CL6326-1 | 360 | 9.9 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 3E-48 | 68% | EHJ73729.1 |

| ALR9 | U10235 | 426 | 3.1 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 6E-81 | 84% | EHJ71310.1 |

| ALR10 | U11986 | 306 | 3.3 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-10 | 41% | EHJ68420 |

| ALR11 | U12541 | 231 | 6.3 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 2E-19 | 59% | AGQ45607.1 |

| ALR12 | U13468 | 289 | 2.8 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-37 | 73% | EHJ68420.1 |

| ALR13 | U13469 | 358 | 7.2 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 7E-27 | 60% | EHJ68420.1 |

| ALR14 | U17782 | 663 | 10.9 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 1E-130 | 79% | EHJ73729.1 |

| ALR15 | U19886 | 975 | 34.4 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 78% | XP_004921850.1 |

| ALR16 | U21480 | 750 | 11.4 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 8E-81 | 52% | AGQ45608.1 |

| ALR17 | U21731 | 1131 | 52.5 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 95% | NP_001040507.1 |

| Desaturase (DES) | ||||||||

| KPSE | CL1090-3 | 1062 | 16.6 | acyl-CoA delta-9 desaturase | Helicoverpa zea | 2E-171 | 100% | AAF81788.1 |

| NPVE | CL1090-4 | 1062 | 4364.0 | acyl-CoA delta-9 desaturase | Helicoverpa zea | 0E+00 | 100% | AAF81790.2 |

| MPVE | CL1931-1 | 900 | 13.4 | acyl-CoA Delta(11) desaturase | Bombyx mori | 2E-09 | 72% | XP_004925564.1 |

| GATD | U23856 | 1119 | 41.5 | acyl-CoA desaturase HassGATD | Helicoverpa assulta | 0E+00 | 98% | AAM28480.2 |

| LPAQ | U23789 | 1017 | 3975.6 | acyl-CoA delta-11 desaturase | Helicoverpa zea | 0E+00 | 99% | AAF81787.1 |

| KSVE | U21458 | 1119 | 64.0 | acyl-CoA desaturase HvirKSVE | Heliothis virescens | 0E+00 | 98% | AGO45842.1 |

| NRPE | U27960 | 822 | 3.5 | acyl-CoA Delta(11) desaturase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 92% | XP_004932163.1 |

| Fatty acid synthase (FAS) | ||||||||

| FAS1 | CL2920-1 | 3843 | 4.3 | fatty acid synthase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 92% | AGR49310.1 |

| FAS2 | U17719 | 2798 | 237.5 | fatty acid synthase | Agrotis segetum | 0E+00 | 92% | AID66645.1 |

| FAS3 | U17720 | 1177 | 65.8 | fatty acid synthase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 91% | AGR49310.1 |

| Fatty acyl-CoA reductase (FAR) | ||||||||

| FAR1 | CL1521-1 | 516 | 46.3 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 8E-109 | 91% | AGR49318.1 |

| FAR2 | CL1525-1 | 1572 | 58.4 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 6, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 72% | AGR49316.1 |

| FAR3 | CL1589-2 | 501 | 1.6 | fatty acid reductase | Helicoverpa assulta | 4E-35 | 38% | AFD04727.1 |

| FAR4 | CL1835-1 | 1270 | 17.4 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 2 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 0E+00 | 81% | ADI82775.1 |

| FAR5 | CL3768-1 | 1614 | 69.7 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 75% | XP_004926017.1 |

| FAR6 | CL4218-1 | 366 | 14.4 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 6 | Agrotis ipsilon | 5E-57 | 89% | AGR49326.1 |

| FAR7 | CL4398-1 | 909 | 4.0 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 5 | Danaus plexippus | 3E-129 | 76% | EHJ72233.1 |

| FAR8 | CL5981-1 | 1266 | 45.5 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 6 | Danaus plexippus | 0E+00 | 64% | EHJ76493.1 |

| FAR9 | CL6073-1 | 1557 | 39.2 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 81% | XP_004929961.1 |

| FAR10 | CL6322-1 | 861 | 87.9 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 6E-175 | 85% | AGR49318.1 |

| FAR11 | CL6616-1 | 1424 | 59.9 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 83% | XP_004925992.1 |

| FAR12 | CL7377-1 | 1371 | 414.2 | fatty acid reductase | Helicoverpa assulta | 0E+00 | 99% | AFD04727.1 |

| FAR13 | U2195 | 1497 | 22.0 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 4 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 0E+00 | 68% | ADI82777.1 |

| FAR14 | U24540 | 417 | 23.4 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 1E-86 | 95% | AGR49319.1 |

| FAR15 | U24542 | 936 | 22.2 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 94% | AGR49319.1 |

| FAR16 | U25481 | 201 | 40.3 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 5 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 3E-22 | 63% | ADI82778.1 |

| FAR17 | U25568 | 405 | 22.7 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 2 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 7E-68 | 74% | ADI82775.1 |

| FAR18 | U32 | 564 | 18.1 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 5 | Danaus plexippus | 2E-94 | 75% | EHJ72233.1 |

Table 2. BLASTX results for putative sex pheromone biosynthesis transcripts in Helicoverpa assulta pheromone glands.

| Transcript | Best Blastp Match | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | ID | ORF | RPKM | Name | Species | E-value | Identity | Acc. number |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) | ||||||||

| ACC1 | U22914 | 510 | 7.7 | cetyl-coA carboxylase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 1E-80 | 79% | AGR49309.1 |

| ACC2 | CL1044-1 | 4983 | 41.5 | acetyl-coA carboxylase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 95% | AGR49308.1 |

| Aldo-Ketose Reductase (ALR) | ||||||||

| ALR1 | U4829 | 320 | 4.0 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Culex quinquefasciatus | 2E-17 | 86% | XP_001848848 |

| ALR2 | CL3549-1 | 483 | 8.8 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 3E-44 | 55% | AGQ45608.1 |

| ALR3 | CL3700-1 | 813 | 7.2 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 3E-62 | 47% | EHJ68420.1 |

| ALR4 | U1366 | 198 | 5.7 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 6E-18 | 59% | AGQ45607.1 |

| ALR5 | CL2456-2 | 1002 | 10.7 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 79% | AGQ45607.1 |

| ALR6 | U18627 | 753 | 521.2 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 7E-142 | 78% | AGQ45608.1 |

| ALR7 | U6810 | 975 | 14.9 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 5E-133 | 64% | EHJ73729.1 |

| ALR8 | U4937 | 342 | 5.5 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-21 | 59% | EHJ68420.1 |

| ALR9 | U12805 | 1017 | 9.6 | aldose reductase-like | Bombyx mori | 4E-176 | 71% | XP_004921845 |

| ALR10 | U7365 | 305 | 2.9 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-25 | 54% | EHJ71310.1 |

| ALR11 | U8744 | 813 | 3.3 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-117 | 62% | EHJ70606.1 |

| ALR12 | U23789 | 483 | 3.8 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 1E-69 | 65% | NP_001037610 |

| ALR13 | CL115-1 | 759 | 0.0 | alcohol dehydrogenase, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 2E-118 | 62% | AGQ45606.1 |

| ALR14 | U9712 | 1071 | 9.0 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 0E+00 | 74% | EHJ73729.1 |

| ALR15 | U19322 | 975 | 66.1 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 77% | XP_004921850 |

| ALR16 | U4138 | 694 | 4.2 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Danaus plexippus | 2E-49 | 82% | EHJ71310.1 |

| ALR17 | U1545 | 1131 | 106.3 | alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 95% | NP_001040507 |

| ALR18 | U24329 | 366 | 3.2 | putative alcohol dehydrogenase | Bombyx mori | 7E-36 | 78% | NP_001037610 |

| Desaturase (DES) | ||||||||

| KPSE | U18841 | 1062 | 659.9 | acyl-CoA delta-9 desaturase | Helicoverpa zea | 0E+00 | 100% | AAF81788.1 |

| NPVE | U21938 | 1062 | 949.2 | acyl-CoA desaturase HassNPVE | Helicoverpa assulta | 0E+00 | 99% | AAM28484.2 |

| MPVE | U1020 | 1104 | 16.8 | acyl-CoA Delta(11) desaturase-like | Bombyx mori | 1E-173 | 65% | XP_004925564 |

| GATD | U18038 | 1119 | 40.0 | acyl-CoA desaturase HassGATD | Helicoverpa assulta | 0E+00 | 99% | AAM28480.2 |

| LPAQ | U21077 | 1017 | 132.9 | acyl-CoA desaturase HassLPAQ | Helicoverpa assulta | 0E+00 | 99% | AAM28483.2 |

| KSVE | U21918 | 1119 | 26.9 | acyl-CoA desaturase HvirKSVE | Heliothis virescens | 0E+00 | 98% | AGO45842.1 |

| KSPP | U12152 | 892 | 6.5 | acyl-CoA Delta(11) desaturase-like | Bombyx mori | 1E-160 | 75% | NP_001274329 |

| TYSY | CL2025-1 | 966 | 20.3 | desaturase | Agrotis segetum | 0E+00 | 94% | AID66658.1 |

| Fatty acid synthase (FAS) | ||||||||

| FAS1 | U13060 | 910 | 4.2 | fatty acid synthase-like | Bombyx mori | 4E-82 | 48% | XP_004927661 |

| FAS2 | U22164 | 7170 | 345.7 | fatty acid synthase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 92% | AGR49310.1 |

| FAS3 | U2985 | 271 | 3.7 | fatty acid synthase-like | Bombyx mori | 8E-24 | 73% | XP_004922804 |

| Fatty acyl-CoA reductase (FAR) | ||||||||

| FAR1 | CL3772-1 | 1614 | 7.8 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 75% | XP_004926017 |

| FAR2 | U795 | 1497 | 30.4 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 4 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 0E+00 | 69% | ADI82777.1 |

| FAR3 | U1030 | 1488 | 101.1 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 94% | AGR49319.1 |

| FAR4 | U1584 | 1575 | 55.6 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 6 | Danaus plexippus | 0E+00 | 63% | EHJ76493.1 |

| FAR5 | U18296 | 1557 | 26.0 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 0E+00 | 80% | XP_004929961 |

| FAR6 | U20971 | 1371 | 960.1 | fatty acid reductase | Helicoverpa assulta | 6E-108 | 100% | AFD04727.1 |

| FAR7 | U22269 | 1569 | 94.4 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 3 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 0E+00 | 80% | ADI82776.1 |

| FAR8 | CL283-1 | 1533 | 14.7 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 87% | AGR49318.1 |

| FAR9 | U25153 | 244 | 2.7 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 1E-25 | 64% | XP_004925987 |

| FAR10 | U25265 | 305 | 2.0 | putative fatty acyl-CoA reductase | Bombyx mori | 2E-51 | 91% | XP_004930776 |

| FAR11 | CL598-1 | 1572 | 0.3 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 6, partial | Agrotis ipsilon | 0E+00 | 71% | AGR49316.1 |

| FAR12 | CL1250-1 | 1617 | 0.1 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 5 | Danaus plexippus | 0E+00 | 74% | EHJ72233.1 |

| FAR13 | CL1309-1 | 488 | 16.7 | fatty-acyl CoA reductase 2 | Ostrinia nubilalis | 0E+00 | 81% | ADI82775.1 |

Tissue expression profile and mRNA abundance of the sex pheromone biosynthesis putative genes

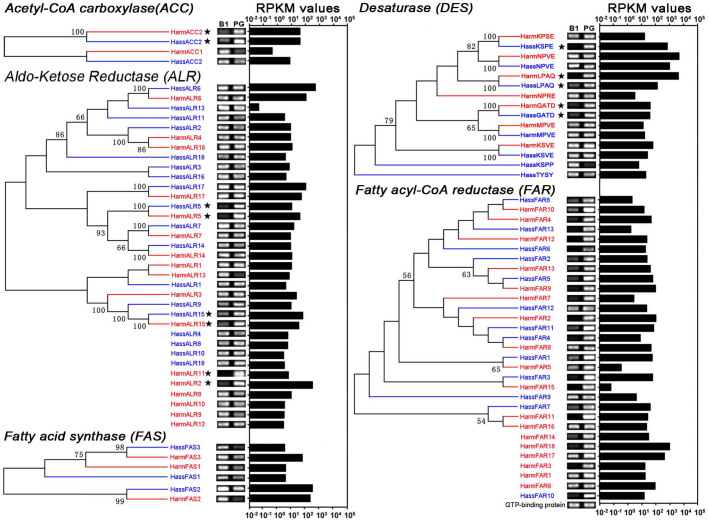

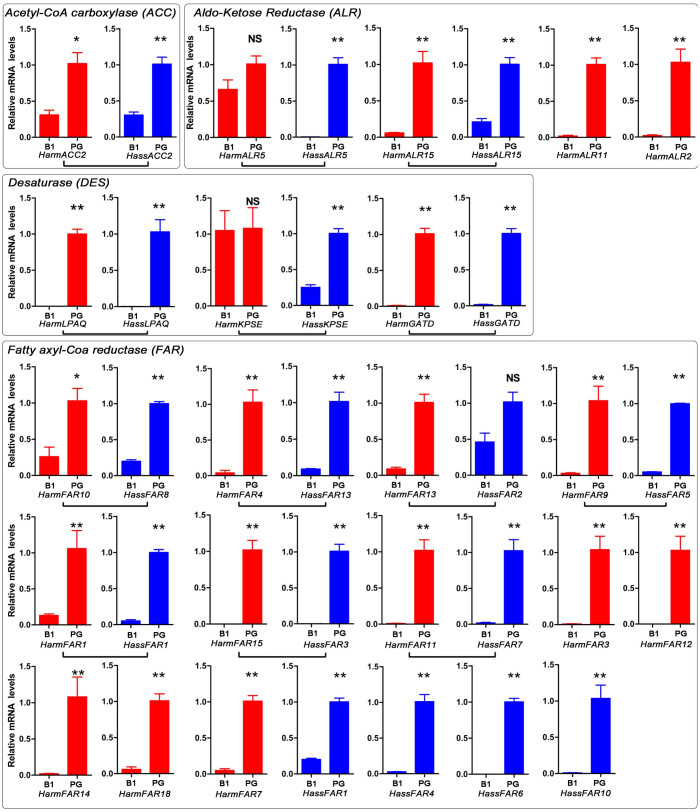

We further characterized the expression levels and tissue expression pattern of the transcripts putatively involved in pheromone biosynthesis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. Transcript abundance in the PG was also calculated as RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads). For this analysis, H. armigera sequences had the prefix Harm and H. assulta sequences had the prefix Hass followed by the gene name. The results showed that all the analysed transcripts had different expression patterns and most orthologous transcripts had similar expression profiles (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Phylogenetic analysis, expression profiles and abundances of pheromone biosynthesis-related transcripts in Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA6.0 using the neighbour-joining method. Bootstrap values >50% (1000 replicates) are indicated at the nodes. Transcripts that were too short for phylogenetic analysis are listed under the respective trees. Expression levels of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, aldo-Ketose Reductase, desaturase and fatty acyl-CoA related transcripts were determined in female bodies without pheromone glands (B1) and PGs by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Transcripts from H. armigera are labelled in red and H. assulta in blue. Transcript expression abundance is indicated as RPKM values. The PG-biased ACC, ALR, FAS, and DESs are labelled with pentagrams in the phylogenetic tree. The gene for GTP-binding protein was used as the positive control.

Figure 4. Relative expression levels of Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta transcripts with PG-biased expression in different female tissues.

Expression levels of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, aldo-Ketose Reductase, desaturase and fatty acyl-CoA related transcripts were determined in female bodies without pheromone glands (B1) and PGs by qRT-PCR. Transcripts from H. armigera are labelled in red and H. assulta in blue. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between the expression levels in female body and PGs (P < 0.05, Student's t-test). “NS” indicates no significant difference (P > 0.05).

We identified two ACCs from the PGs of both H. armigera and H. assulta (Tables 1 and 2). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR results revealed that HarmACC2 and HassACC2 were highly expressed in PGs compared to the female body without the PGs (Figs. 3 and 4). Their transcript abundance was also markedly higher (40.9 and 41.5 RPKM) than HarmACC1 and HassACC1 (0.4 and 7.7 RPKM) in the transcriptomes.

Three FASs were identified in the PGs from H. armigera and H. assulta (Tables 1 and 2). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that all three transcripts were expressed at higher levels in the female body when compared to the PGs (Figs. 3 and 4). However, the RPKM values indicated that both HarmFAS2 (237.5) and HassFAS2 (345.7) were abundant in the PG transcriptomes. The RPKM values of HarmFAS2 and HassFAS2 were 3- and 82-fold higher than the other transcripts in the PG transcriptomes.

Seven and eight DESs were identified in the PGs of H. armigera and H. assulta, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR results showed that HarmLPAQ, HarmGATD, HassLPAQ, HassGATD, and HassKPSE had robust expression in the PGs when compared to the female body (Figs. 3 and 4).

To evaluate transcript expression abundances, the RKPM values of DESs, HarmKPSE (16.6 RPKM), HarmGATD (41.5 RPKM), HarmLPAQ (3975.6 RPKM), HassKPSE (659.9 RPKM), HassGATD (40.0 RPKM), and HassLPAQ (132.8 RPKM), were calculated (Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 3). In comparison, HarmLPAQ (Δ11) was highly abundant in the H. armigera PG transcriptome, HassLPAQ and HassKPSE were highly abundant in the H. assulta PG transcriptome. The abundance of HassKPSE (Δ9) was 7-fold higher in the H. assulta PG transcriptome than HassLPAQ (Δ11), and HarmLPAQ (Δ11) was 239-fold higher in the H. armigera PG transcriptome than HassKPSE (Δ9). In addition, the abundance of HassKPSE in the H. assulta was 39-fold higher than HarmKPSE in H. armigera, while HassLAPQ was 30-fold lower than HarmLPAQ. HarmGATD and HassGATD had lower abundances in PG transcriptomes compared to HarmLPAQ, HassKPSE and HassLPAQ.

There were 18 and 13 fatty acyl-CoA reductases (FAR) in the H. armigera and H. assulta PG transcriptomes, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Among the 18 FARs in H. armigera, HarmFAR12 (FKPM = 414.1) was more abundant in the PG transcriptome than the other 11 PG-biased FARs (RPKM < 70) (Table 1, and Figs. 3 and 4). In H. assulta, HassFAR6 (RPKM 960.1) was more abundant in the PG transcriptome than the other PG-biased FARs (RPKM < 102) (Table 2, and Figs. 3 and 4).

ALR is involved in converting an alcohol to an aldehyde. We identified 17 and 18 ALRs in the H. armigera and H. assulta PG transcriptomes, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR results indicated that HarmALR15, HarmALR11, and HarmALR2 in H. armigera, and HassALR5 and HassALR15 in H. assulta had PG-biased expression (Figs. 3 and 4). In H. armigera, HarmALR2 was highly abundant (RPKM = 323.6) in the PG transcriptome than the other PG-biased ALRs (RPKM < 35) (Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 3). In H. assulta, HassALR15 had a higher RPKM (66.1) value than HassALR5 (10.7).

Phylogenetic analyses of the DESs

To further investigate the function of the DESs from H. armigera and H. assulta, 15 candidate DESs from these two species were phylogenetically analysed with other lepidopteran DESs (Fig. 5). In the resulting phylogenetic tree, we observed three well-supported clades including Δ9-desaturases (16C > 18C), Δ9-desaturases (16C < 18C), and Δ11-desaturases. The five PG-biased transcripts from H. armigera and H. assulta were well separated from each other, with many other lepidopteran DESs interspersed among them. HarmLPAQ was very close to HassLPAQ in the Δ11-desaturases clade, and HassKPSE was a member of the Δ9-desaturases (16C > 18C) group. Interestingly, HarmKPSE, did not show PG-biased expression (Figs. 3 and 4) although it was present in the same clade as HassKPSE and the two proteins shared high amino acid identity (99.72%). Similarly, HarmLPAQ and HassLPAQ also shared high amino acid identity (99.70%). It is notable that two transcripts with PG-biased expression, HarmGATD and HassGATD, did not belong to any of the three main clades.

Figure 5. Phylogenetic tree of putative DES from Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta and other known DESs from lepidopterans.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6.0 using the neighbour-joining method. Bootstrap values >50% (1000 replicates) are indicated at the nodes. Transcripts from H. armigera are labelled in red and H. assulta in blue. DESs with PG-bias are indicated with pentagrams.

Tissue expression profiles of the sex pheromone transport putative genes

We identified 19 and 16 CSPs, and 26 and 23 OBPs in H. armigera and H. assulta, respectively (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 online). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR results indicated that the orthologous transcripts had similar expression profiles (Fig. 6). Most of the OBPs were highly expressed in antennae and/or PGs, indicating their function in the detection and protection of plant volatiles, oviposition-deterring pheromones, and sex pheromones. Most CSPs were expressed in a range of tissues, suggesting common functions. Similar to OBPs, several CSPs in the Helicoverpa species were highly expressed in antennae and/or PGs (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Phylogenetic analysis, expression profiles and abundances of pheromone transport- and degradation-related transcripts in Helicoverpa armigera and Helicoverpa assulta.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6.0 using the neighbour-joining method. Bootstrap values >50% (1000 replicates) are indicated at the nodes. Transcripts that were too short for phylogenetic analysis are listed under the respective phylogenetic trees. Expression levels of odorant-binding proteins, chemosensory proteins, aldehyde dehydrogenase and aldehyde oxidase were determined in female antennae (FA), male antennae (MA), female bodies without pheromone glands and antennae (B2) and PGs by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Transcripts from H. armigera are labelled in red and H. assulta in blue. Transcript expression abundance is indicated by RPKM values. The gene for GTP-binding protein was used as the positive control.

Tissue expression profiles of sex pheromone degradation putative genes

We identified nine and six ADs, and seven and four AOXs in H. armigera and H. assulta, respectively (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 online). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that HarmAD4, HarmAOX7, HarmAOX2, HarmAOX3, HarmAOX4, HarmAOX5, and HarmAOX6 in H. armigera and HassAD9, HassAOX3, and HassAOX5 in H. assulta were mainly expressed in antennae and PGs (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Speciation in insects is often associated with changes in mate recognition systems. Particularly, sex pheromone-induced behaviours play crucial roles in insect reproduction and contribute significantly to reproductive isolation26. In moths, sex pheromones are synthesized in the PGs. Both H. armigera and H. assulta, which are sibling noctuid species, use the sex-pheromone components, Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald. However, the components are present in opposite ratios in the two species. Intrigued by this, we investigated differences in the transcripts related to sex pheromone biosynthesis, transport and degradation in the two sibling species by sequencing the transcriptomes from the PGs of the two Helicoverpa species.

A total of 108 and 93 putative pheromone biosynthesis, transport, and degradation transcripts were respectively identified in H. armigera and H. assulta PGs. Further characterization of these transcripts by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, phylogenetic, and mRNA abundance analyses revealed that some of the transcripts had three characteristics: 1) transcripts that are distinctly or highly expressed in PGs than female body (without PG), 2) transcripts that are more abundant than the other transcripts in the PGs, and 3) transcripts that are homologous to other insect genes with demonstrated function in sex pheromone biosynthesis.

Generally, the pheromone biosynthesis pathway in moths begins with the ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA catalysed by ACC27. Compared to other ACCs, HarmACC2 and HassACC2 were highly expressed in PGs and were highly abundant than the other ACCs. In pheromone biosynthesis, FAS has been shown to use malonyl-CoA and NADPH to produce fatty acids4. In this study, none of the FASs displayed PG-biased expression, although HarmFAS2 and HassFAS2 were highly abundant in the PG transcriptomes with high RPKM values compared to other FASs. Future studies on the functional characterization of the Helicoverpa ACCs and FASs may reveal their specific roles in pheromone biosynthesis.

During sex pheromone biosynthesis, DESs introduces double bonds at specific positions in fatty acid chains28,29. Previous studies with labelled fatty acids demonstrated that different pathways are used in the pheromone biosynthesis in H. armigera and H. assulta22 to achieve the markedly different ratios in the sex pheromone components, Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald. Among the DESs identified in our study, HarmGATD, HarmLPAQ, HassKPSE, HassGATD, and HassLPAQ displayed PG-biased expression compared with the adult female body. However, phylogenetic analyses showed that HarmGATD and HassGATD were not clustered into groups that were previously demonstrated to function in sex pheromone biosynthesis. On the other hand, HarmLPAQ and HassLPAQ were the members of Δ11-desaturases group, and HarmKPSE was closely related to HassKPSE in the Δ9-desaturases (16C > 18C) group. These two groups of desaturases share a conserved biological function in sex pheromone biosynthesis30. Previous studies on desaturases from H. assulta24,31, Helicoverpa zea32 and Trichoplusia ni9,33 showed that HassKPSE encodes a Δ9-desaturase. The action of this Δ9-desaturase results in the production of higher amounts of Z9-16:Acid than Z9-18:Acid24. HassLPAQ shown to encode a Δ11-desaturase that specifically produced Z11-16:Acid. HzPGDs232, TniKPSE33 and HassKPSE24 have high amino acid identity, sharing the similar function. In addition, the function of HassLPAQ24, HzPGDs132 and TniLPAQ9 were similar to each other. Considering the amino acid high identity (about 99.7% with only one amino acid difference) between HarmKPSE and HassKPSE, and HarmLPAQ and HassLPAQ, it is likely that HarmKPSE and HassKPSE encode Δ9-desaturases, HarmLPAQ and HassLPAQ encode Δ11-desaturases in H. armigera and H. assulta.

Interestingly, HarmKPSE did not show PG-biased expression, suggesting that this gene is not involved in the sex pheromone biosynthesis. This results is well consistent with the previous labelling study22 with D3-16:Acid and D3-18:Acid showed that Z11-16:Ald is produced by Δ11 desaturation of 16:Acid in both H. armigera and H. assulta. However, Z9-16:Ald is produced by Δ11 desaturation of 18:Acid and one cycle of two-carbon chain shortening in H. armigera, while Z9-16:Ald is mainly produced by Δ9 desaturation of 16:Acid and by Δ11 desaturation of 18:Acid and one cycle of two-carbon chain shortening in H. assulta22.Therefore, unlike the HassKPSE, HarmKPSE that encodes a Δ9-desaturase is not likely to be involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis.

On the other hand, PG abundance is another characteristic feature of the genes involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis. The high abundance of HarmLPAQ, HassKPSE and HassLPAQ in the PG transcriptomes suggest that these high abundance and PG biased transcripts may have a role in sex pheromone biosynthesis in the two Helicoverpa species. Furthermore, the abundance of HassKPSE (Δ9) was 7-fold higher than HassLPAQ (Δ11) in the H. assulta PG transcriptome was consistent with the major pheromone component being Z9-16:Ald in H. assulta. As compared with HarmLPAQ, the lower abundance of HarmKPSE (about 239-fold) is consistent with that HarmKPSE is not likely to be involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis. Together our data along with others reported previously24,22 suggest that among the DESs identified in our study, only HarmLPAQ (Δ11) is likely involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis in H. armigera, while both HassLPAQ (Δ11) and HassKPSE (Δ9) may be involved in this process in H. assulta.

Mutations that affect gene regulation could be more important in evolution than those changing the amino acid sequence of a protein34. In our study, HarmKPSE and HassKPSE had high amino acid identity (99.72%) indicating similar function. But, their expression patterns were different, and the mRNA abundance of HassKPSE was 39-fold higher in the H. assulta PG than HarmKPSE in H. armigera PG, while HassLPAQ was 30-fold lower than HarmLPAQ. Therefore, we presume that the regulation of DESs in these two Helicoverpa species likely resulted in the evolution of different pathways in the sex pheromone biosynthesis resulting in the final opposite ratios between two sex pheromone components. Further studies on regulation of DESs and its function are needed to determine their specific roles in the biosynthesis pathways of these two Helicoverpa species.

After the introduction of a specific double bond in the sex pheromone biosynthesis pathway, the fatty acyl CoA pheromone precursors are further reduced to the corresponding alcohols by FAR35,36,37 and then catalysed by ALR. Among the FARs and ALRs identified in this study, HarmFAR12, HassFAR6, HarmALR2, and HassALR15 not only showed PG-biased expressions but also displayed a higher abundance than the others in the PGs suggesting their role in sex pheromone biosynthesis.

Some olfactory sensilla are distributed on the ovipositor38,39, which may function in the olfactory detection of plant odours, ovipositor-deterring pheromones, and sex pheromones. OBPs and CSPs are thought to be responsible for the binding and transport of hydrophobic molecules, including pheromones and plant volatiles13,15. After sex pheromones have stimulated the olfactory receptor neurons, they must be rapidly removed by AD and/or AOX to restore the sensitivity of the sensory neuron16. The OBPs and CSPs that are mainly expressed in antennae and PGs could play important roles in the binding and transport of plant volatiles, oviposition-deterring pheromones, and sex pheromones. On the other hand, antennae and PGs highly expressed ADs, and AOXs, which could be involved in degrading sex pheromone and aldehyde odorants16,40.

In conclusion, we sequenced the PG transcriptomes in the two noctuid sibling species, H. armigera and H. assulta to identify the mechanisms regulating the opposite ratios of the sex pheromone components, Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald in the two species. Our analyses based on phylogeny, transcript expression, and transcript abundance indicates that a number of transcripts with PG-biased expression could be involved in the sex pheromone biosynthesis in the two species. Particularly, DESs seem to play a prominent role in the regulation of the component ratio in H. armigera and H. assulta. Additional functional analyses are needed to verify this conjecture in future.

Methods

Insect samples

Helicoverpa armigera were collected from cotton fields in the Institute of Cotton Research at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Helicoverpa assulta were provided by the Henan University of Science and Technology in China. Both species were reared in the laboratory on an artificial diet41 at 25 ± 1°C, 14:10 L:D light cycle, and 65 ± 5% relative humidity. Pupae were sexed and kept separately in cages for eclosion. The pupae were checked daily for emergence and supplied with 10% honey solution as food for the emerging adults.

Tissue collection

To construct cDNA libraries, 15 PGs from 3-day-old virgin females from each of the two species were collected at 5 h in scotophase (Fig. 1), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further use. In addition, for semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR, female antennae (FA), male antennae (MA), pheromone glands (PGs), whole insect body without pheromone glands (B1), and whole insect body without pheromone glands and antennae (B2) were also collected from three-day-old virgin insects. These tissues were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation.

cDNA library construction and Illumina sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the PGs of H. armigera and H. assulta using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and cDNA library construction and Illumina sequencing of the samples were performed at the Beijing Genomics Institute, Shenzhen, China42. For each species, poly-adenylated RNA were isolated from 20 μg of pooled total RNA using oligo (dT) magnetic beads. Then, the mRNA from each species were fragmented into short pieces in the presence of divalent cations in fragmentation buffer at 94°C for 5 min. Using the cleaved fragments as templates, random hexamer primers were used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using the. Second-strand cDNA was generated using the buffer, dNTPs, RNAseH, and DNA polymerase I. Following end repair and adaptor ligation, short sequences were amplified by PCR and purified with a QIAquick® PCR extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands), and sequenced on a HisSeq™ 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The clean reads obtained in this study are available at the NCBI/SRA database under accession numbers SRR1565435 and SRR1570898.

Assembly and annotation

The PG transcriptomes of H. armigera and H. assulta were assembled de novo using the short-read assembly program Trinity43, which generated two classes of transcripts: clusters (prefix CL) and singletons (prefix U). Transcripts larger than 150 bp were compared to existing sequences in the protein databases, including NCBI Nr, Swiss-Prot, KEGG44, and COG, using blastX. We then used the Blast2GO program45 for GO annotation of the transcripts and WEGO software46 to plot the GO annotation results.

Analysis of transcript expression in the pheromone glands

Transcript expression abundances were calculated by the RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) method47, which can eliminate the influence of different transcript lengths and sequencing discrepancies in calculating expression abundance47. RPKM was calculated from the equation (1):

|

where RPKM (A) is the expression of transcript A; C is the number of reads uniquely aligned to transcript A; N is the total number of fragments uniquely aligned to all transcripts; and L is the number of bases in transcript A.

Phylogenetic analysis

To investigate the phylogenetic relationships between the two Helicoverpa species, we compared all putative transcripts involved in the pheromone biosynthesis, reception, and degradation in each of the two species using ClustalX2.0 with default settings48. Since desaturases are the most extensively studied class of enzymes involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis, we imported 67 lepidopteran desaturases28 sequences from NCBI Nr and those from H. armigera and H. assulta. All phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbour-joining method implemented in MEGA6 with default settings and 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Semi-quantitative RT–PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the SV Total Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Single-stranded cDNA templates were synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA from various samples (FA, MA, PGs, B1 and B2) using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega) following the instructions in the manual.

Specific primers for the transcripts putatively involved in pheromone biosynthesis, reception, and degradation were designed using Beacon Designer 7.7 (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA) (Supplementary Table S6 online). Semi-quantitative PCR experiments with negative controls (no cDNA template) were performed as follows: 94°C for 2 min; followed by 28 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec. The reactions were performed in 20 μL PCR reactions containing 2.0 μL of 10× Ex-Taq PCR buffer, 1.6 μL of dNTPs (10 mM), 0.8 μL of forward primer (10 μM), 0.8 μL of reverse primer (10 μM), 15 ng of single-stranded cDNA, and 0.2 μL Ex-Taq (5 U/μL). PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis on 2.0% w/v agarose gel in TAE buffer and the resulting bands were visualized with GluRed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The GTP-binding protein (GenBank No. AY957405) from H. armigera was used as an endogenous control. Each reaction had three independent biological replicates.

Quantitative real time PCR and data analysis

Total RNA and cDNA synthesis were performed as described for semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis. qRT-PCR was performed in a Mastercycler® ep realplex (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with primers designed based on the Helicoverpa nucleotide sequences from the Illumina data using Beacon Designer 7.7 (Supplementary Table S7 online). The H. armigera GTP-binding protein (AY957405) and GAPDH (JF417983) were used as reference genes. Expression levels of the tested mRNA were determined using the GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A blank control without template cDNA (replacing cDNA with H2O) served as the negative control. Each reaction had three independent biological replicates and was repeated three times (technical replicates). Relative expression levels were calculated using the comparative 2−δδCT method49.

Statistical Analysis of data

Data (mean ± SE) from various samples were subjected to one-way nested analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a least significant difference test (LSD) for mean comparison. Two-sample analysis was performed by Student's t-test using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Author Contributions

J.C. and S.Z. conceived and designed the experiments; Z.L. performed the experiments; Z.L., S.D., J.L., L.L. and C.W. analysed the data; and Z.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Dataset 1

Supplementary Dataset 2

Supplementary Dataset 3

Supplementary Dataset 4

Supplementary Dataset 5

Supplementary Dataset 6

Supplementary Dataset 7

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by research grants from the Ministry of Agriculture in China (2014ZX08011-002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071978).

References

- Wyatt T. D. Fifty years of pheromones. Nature 457, 262–263 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S. P. Lipid analysis of the sex pheromone gland of the moth Heliothis virescens. Archives of insect biochemistry and physiology 59, 80–90 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurenka R. Insect pheromone biosynthesis. Topics in current chemistry 239, 97–132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe J. J. & Vagelos P. R. Saturated fatty acid biosynthesis and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 42, 21–60 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskovec M., Luxová A., Svatoš A. & Boland W. Biosynthesis of sex pheromones in moths: stereochemistry of fatty alcohol oxidation in Manduca sexta. Tetrahedron 58, 9193–9201 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom A. K. et al. A novel fatty acyl desaturase from the pheromone glands of Ctenopseustis obliquana and C. herana with specific Z5-desaturase activity on myristic acid. J. Chem. Ecol. 40, 63–70 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. L., Lienard M. A., Zhao C. H., Wang C. Z. & Lofstedt C. Neofunctionalization in an ancestral insect desaturase lineage led to rare Delta6 pheromone signals in the Chinese tussah silkworm. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 742–751 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. Y., Kim M. S., Paek A., Jeong S. E. & Knipple D. C. An abundant acyl-CoA (Delta9) desaturase transcript in pheromone glands of the cabbage moth, Mamestra brassicae, encodes a catalytically inactive protein. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 581–595 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipple D. C. et al. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a pheromone gland-specific acyl-CoA Delta11-desaturase of the cabbage looper moth, Trichoplusia ni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 15287–15292 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moto K. et al. Involvement of a bifunctional fatty-acyl desaturase in the biosynthesis of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori, sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 8631–8636 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs W. L. & Rooney A. P. Molecular genetics and evolution of pheromone biosynthesis in Lepidoptera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 14599 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. J. Odorant-binding proteins in insects. Vitamins and hormones 83, 241–272 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Q. et al. Two Minus-C odorant binding proteins from Helicoverpa armigera display higher ligand binding affinity at acidic pH than neutral pH. J. Insect Physiol. 59, 263–272 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund S. S. et al. Daily rhythms in antennal protein and olfactory sensitivity in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Sci Rep 3, 2494 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P., Zhou J. J., Ban L. P. & Calvello M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 63, 1658–1676 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal W. S. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors,binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–463 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan A. et al. The CCHamide 1 receptor modulates sensory perception and olfactory behavior in starved Drosophila. Sci Rep 3, 2765 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck K. et al. A high-throughput behavioral paradigm for Drosophila olfaction - The Flywalk. Sci Rep 2, 361 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin C. et al. Antennal esterase cDNAs from two pest moths, Spodoptera littoralis and Sesamia nonagrioides, potentially involved in odourant degradation. Insect Mol. Biol. 16, 73–81 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal W. S. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annual review of entomology 58, 373–391 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhang H., Guan R. & Miao X. Identification of differential expression genes associated with host selection and adaptation between two sibling insect species by transcriptional profile analysis. BMC Genomics 14, 582 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. L., Zhao C. H. & Wang C. Z. Comparative study of sex pheromone composition and biosynthesis in Helicoverpa armigera, H. assulta and their hybrid. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35, 575–583 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Hou C., Huang L. Q., Yan F. S. & Wang C. Z. Peripheral coding of sex pheromone blends with reverse ratios in two helicoverpa species. PLoS One 8, e70078 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. E., Rosenfield C. L., Marsella-Herrick P., Man You K. & Knipple D. C. Multiple acyl-CoA desaturase-encoding transcripts in pheromone glands of Helicoverpa assulta, the oriental tobacco budworm. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 609–622 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel H., Heidel A. J., Heckel D. G. & Groot A. T. Transcriptome analysis of the sex pheromone gland of the noctuid moth Heliothis virescens. BMC Genomics 11, 29 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smadja C. & Butlin R. K. On the scent of speciation: the chemosensory system and its role in premating isolation. Heredity (Edinb) 102, 77–97 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape M. E., Lopez-Casillas F. & Kim K. H. Physiological regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase gene expression: effects of diet, diabetes, and lactation on acetyl-CoA carboxylase mRNA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 267, 104–109 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albre J. et al. Sex Pheromone Evolution Is Associated with Differential Regulation of the Same Desaturase Gene in Two Genera of Leafroller Moths. PLoS Genet 8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T. et al. Sex pheromone desaturase functioning in a primitive Ostrinia moth is cryptically conserved in congeners' genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 7102–7106 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao G., Liu W., O'Connor M. & Roelofs W. Acyl-CoA Z9- and Z10-desaturase genes from a New Zealand leafroller moth species, Planotortrix octo. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 961–966 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipple D. C., Rosenfield C. L., Nielsen R., You K. M. & Jeong S. E. Evolution of the integral membrane desaturase gene family in moths and flies. Genetics 162, 1737–1752 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield C. L., You K. M., Marsella-Herrick P., Roelofs W. L. & Knipple D. C. Structural and functional conservation and divergence among acyl-CoA desaturases of two noctuid species, the corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea, and the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31, 949–964 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. et al. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a metabolic acyl-CoA delta 9-desaturase of the cabbage looper moth, Trichoplusia ni. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 435–443 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M. C. & Wilson A. C. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188, 107–116 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom A. K., Lienard M. A., Groot A. T., Hedenstrom E. & Lofstedt C. Semi-selective fatty acyl reductases from four heliothine moths influence the specific pheromone composition. PLoS One 7, e37230 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienard M. A., Hagstrom A. K., Lassance J. M. & Lofstedt C. Evolution of multicomponent pheromone signals in small ermine moths involves a single fatty-acyl reductase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 10955–10960 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienard M. A. & Lofstedt C. Functional flexibility as a prelude to signal diversity? Role of a fatty acyl reductase in moth pheromone evolution. Commun Integr Biol 3, 586–588 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucheux M. J. Multiporous sensilla on the ovipositor of Monopis crocicapitella Clem. (Lepidoptera: Tineidae). Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 17, 473–475 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. & Hallberg E. Structure and distribution of tactile and bimodal taste/tactile sensilla on the ovipositor, tarsi and antennae of the flour moth, Ephestia kuehniella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 19, 13–23 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Choo Y. M., Pelletier J., Atungulu E. & Leal W. S. Identification and characterization of an antennae-specific aldehyde oxidase from the navel orangeworm. PLoS One 8, e67794 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Z. & Dong J. F. Interspecific hybridization of Helicoverpa armigera and H. assulta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Chin. Sci. Bull. 46, 489–491 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. J. et al. Deep RNA sequencing at single base-pair resolution reveals high complexity of the rice transcriptome. Genome Res. 20, 646–654 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–U130 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D480–484 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J. et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W293–297 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L. & Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5, 621–628 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F. & Higgins D. G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Dataset 1

Supplementary Dataset 2

Supplementary Dataset 3

Supplementary Dataset 4

Supplementary Dataset 5

Supplementary Dataset 6

Supplementary Dataset 7