Background: The mode of action of insect repellents on odorant receptor (OR) function remains unclear.

Results: Anopheles gambiae OR function in vitro is inhibited by specific repellents.

Conclusion: The identified inhibitory effects are due to functional blocking of Orco, the common subunit of OR heteromers.

Significance: The specific mechanism of action is distinct from the proposed modes of DEET function.

Keywords: Biosensor, Chemical Biology, High-throughput Screening (HTS), Insect, Recombinant Protein Expression, Orco Co-receptor Antagonism, Lepidopteran Insect Cells, Mosquito Olfaction, Olfactory Receptors

Abstract

The identification of molecular targets of insect repellents has been a challenging task, with their effects on odorant receptors (ORs) remaining a debatable issue. Here, we describe a study on the effects of selected mosquito repellents, including the widely used repellent N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET), on the function of specific ORs of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. This study, which has been based on quantitative measurements of a Ca2+-activated photoprotein biosensor of recombinant OR function in an insect cell-based expression platform and a sequential compound addition protocol, revealed that heteromeric OR (ORx/Orco) function was susceptible to strong inhibition by all tested mosquito repellents except DEET. Moreover, our results demonstrated that the observed inhibition was due to efficient blocking of Orco (olfactory receptor coreceptor) function. This mechanism of repellent action, which is reported for the first time, is distinct from the mode of action of other characterized insect repellents including DEET.

Introduction

Insect odorant receptors (ORs),2 which constitute a novel family of heteromeric ligand-gated cation channels (1–3), have been traditionally regarded as the main if not sole molecular targets for insect repellents. The great progress made recently in our understanding of the molecular mechanism(s) of insect olfactory function (4–6) has thus created hope for rational development of improved repellents and/or attractants that could effect a significant reduction in the rate of transmission of malaria and other infectious diseases transmitted by different insect and other arthropod vectors (4, 7).

Prominent among the insect repellents is DEET. This was one of the first to be tested for effects on various insect ORs, with the relevant studies yielding rather contradictory results. Specifically, different mechanisms of DEET action on ORs have been suggested (summarized in Refs. 8 and 9), which include activation of specific ORs, inhibition of specific ORs responding to attractants, and/or modulation of multiple ORs causing olfactory “confusion.” In addition, the effects of a small number of other repellents, such as IR3535, picaridin, and others whose action on insect ORs has been characterized in a more limited fashion, have also been reported (10, 11).

More recently, the modulation of ORs by a number of other compounds, such as amiloride derivatives (12, 13), trace amines (14), and synthetic Orco agonists and antagonists (15–18), has suggested that, because Orco ligands and modulators affect OR function and Orco is highly conserved across insect species, Orco might be a potential target for broadly active insect repellents. Despite their importance for the pharmacological characterization of the receptors, however, most synthetic compounds are expected to have limited usefulness in field application tests due to their low solubility and lack of volatility (15–18). Consequently, more studies are needed to understand the modulation of insect olfactory function by physiologically active compounds, especially repelling compounds, and develop new classes of repellents that may work effectively in the field.

The functional characterization and deorphanization of insect ORs, including most of the Anopheles gambiae repertoire, has been largely achieved through the use of two major test systems, functional receptor expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes (19) or an “empty neuron” of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (20), in conjunction with electrophysiological methods. Besides these assay systems, a number of insect odorant receptors, including pheromone receptors, have also been expressed in mammalian or insect cells (17, 21–28), which employed as main reporter probes fluorescent calcium indicators and were coupled to imaging of individual cells or measurements of fluorescence changes in multiple well formats. Although rather complex preparation, instrumentation, and handling requirements are needed in the case of the Xenopus and Drosophila systems, the assays involving tissue culture cells with fluorescent probes impose other types of limitations including susceptibility to photobleaching, narrow dynamic range, and potential for interference by some compounds that either quench the fluorescent signals or autofluoresce, thus causing low signal-to-noise ratios. Consequently, the development and use of alternative cell-based systems employing reporting tools that may provide more robust and quantitative readouts of insect odorant receptor activity while being amenable to miniaturization are highly desirable.

Here we are reporting on an alternative, lepidopteran insect cell-based assay system for functional expression of mosquito ORs that we have used for characterizing the effects of specific mosquito repellents on receptor function. By reconstituting A. gambiae odorant receptors in the specific heterologous expression system together with a Ca2+-activated photoprotein biosensor allowing quantitative assessments of receptor function, we were able to characterize the effects of specific mosquito repellents including DEET on the function of specific ORx/Orco heteromer combinations. We show that the specific repellents we tested but not DEET block the function of multiple ORs by inhibiting the function of the common co-receptor subunit Orco.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Odorants, Orco agonists, repellents, and OR inhibitors used in the current study are summarized in Table 1. Specifically, benzaldehyde, 2-, 3-, and 4-methylphenol, ethyl butyrate, 2-ethylphenol, cyclohexanone, DEET, and ethyl trans-cinnamate were from Sigma-Aldrich, indole and cuminic alcohol were from Acros Organics, isopropyl cinnamate was from Alfa Aesar, and carvacrol from Beauvilliers Flavors SAS (Peynier, France). VUAA1 (17) was generously provided by Dr. Richard Newcomb (New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research, Auckland, New Zealand), while OrcoRAM2 (11) was obtained from Hit2lead (ChemBridge Corp., San Diego, CA) and Vitas-M Laboratory, Ltd. (Apeldoorn, the Netherlands). OX3a (16) was purchased from Vitas-M Laboratory. Coelenterazine was from Promega, BIOMOL GmbH (Hamburg, Germany) and Biosynth (Staad, Switzerland), while [d-Pen2,d-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE) was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Ruthenium red was a gift of Dr. Dimitrios Kontogiannatos (Agricultural University of Athens, Greece). Initial stock solutions and dilutions for OrcoRAM2 and OX3a (50 mm), as well as for all repellents, were prepared in DMSO, with subsequent working dilutions prepared freshly in Ringer's solution, such that the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed the range of 0.2–0.35%. For all remaining odorants, initial stock solutions were prepared in methanol or ethanol (Table 1).

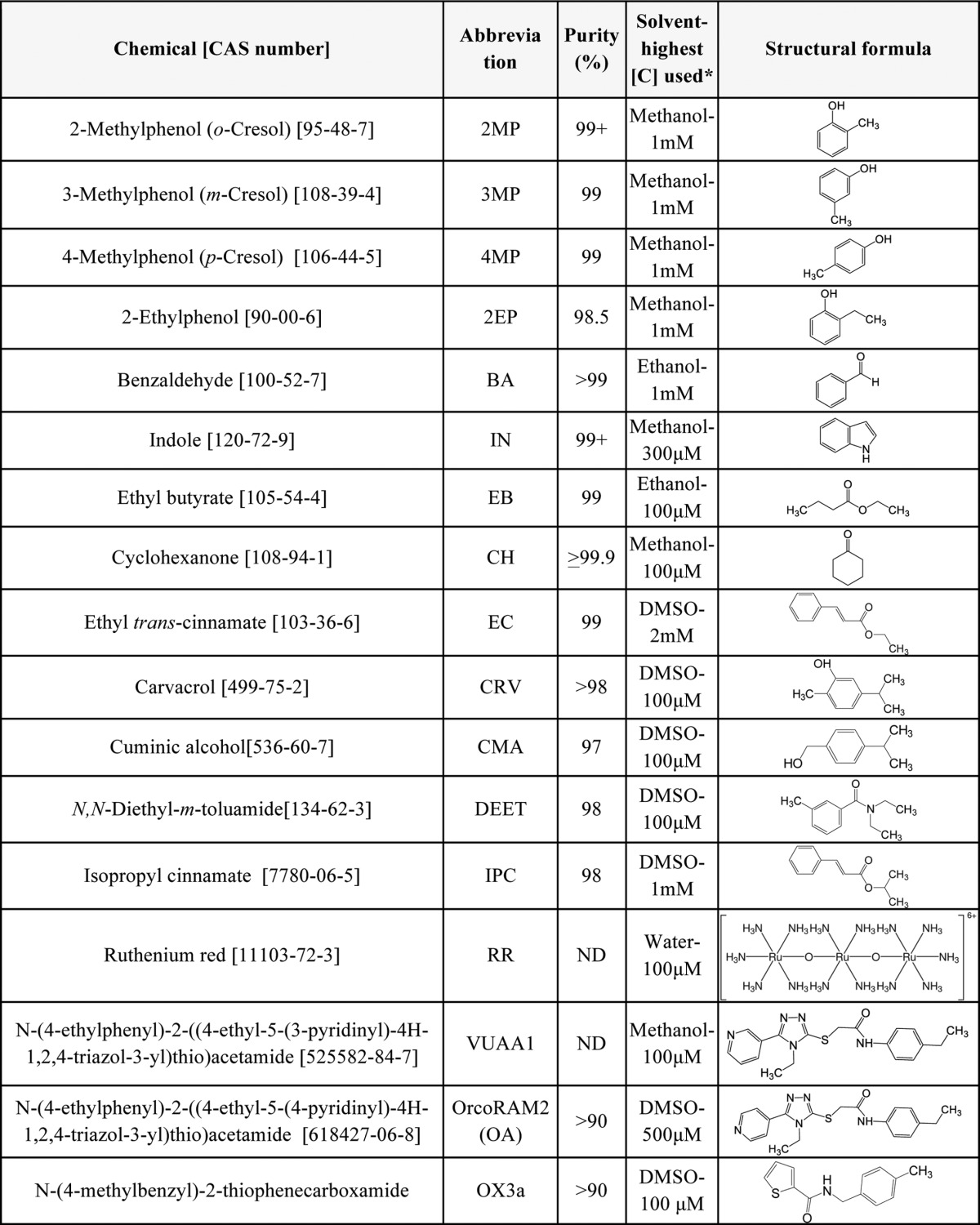

TABLE 1.

Structural formulae of odorants and other chemicals tested in the present study

CAS numbers are in brackets, common names are in parethenses; the corresponding abbreviations used throughout in the figures or in the text are presented in the middle. ND, not determined; [C], concentration; *, mm doses employed for dose-response curve derivation.

Plasmids

The plasmid vector pIE1/153A (henceforth pEIA, see Fig. 1A) was used for expression of A. gambiae ORs, thereafter termed ORx and Orco (for AgamOR7) (29), and the reporter calcium photoprotein in lepidopteran insect cells. This vector ensures high levels of expression by double-enhancing the silkworm cytoplasmic actin promoter with two baculovirus-derived elements, the hr3 enhancer and the IE1 trans-activator (30–32). The construction of plasmids pEIA.OR1, pEIA.OR2, and pEIA.Orco, as well as pEA.Gα16 and pEA.DOR used for expression of human Gα16 and murine δ-opioid receptor, respectively, has been reported (33–35). For expression of the Ca2+-activated luminescent photoprotein, the mito i-Photina® ORF (36) was excised from pcDNA3neo-mito i-Photina® K16 (AXXAM SpA, Milan, Italy) with HindIII-XhoI as a 702-bp fragment and subcloned in the SmaI site of pEIA (30) after blunt-ending. For expression of OR9, PCR amplification and subcloning in the pEIA vector were as described (34) using primers OR9-FA/C (GAATGGATCCCACCATGGTTAGGCTTTTCTTCAGC) and OR9-RA/N (GATAGGATCCCTAATCCGTCATCGATCTC) (BamHI restriction sites are underlined; initiation and termination codons are in bold and italics, respectively).

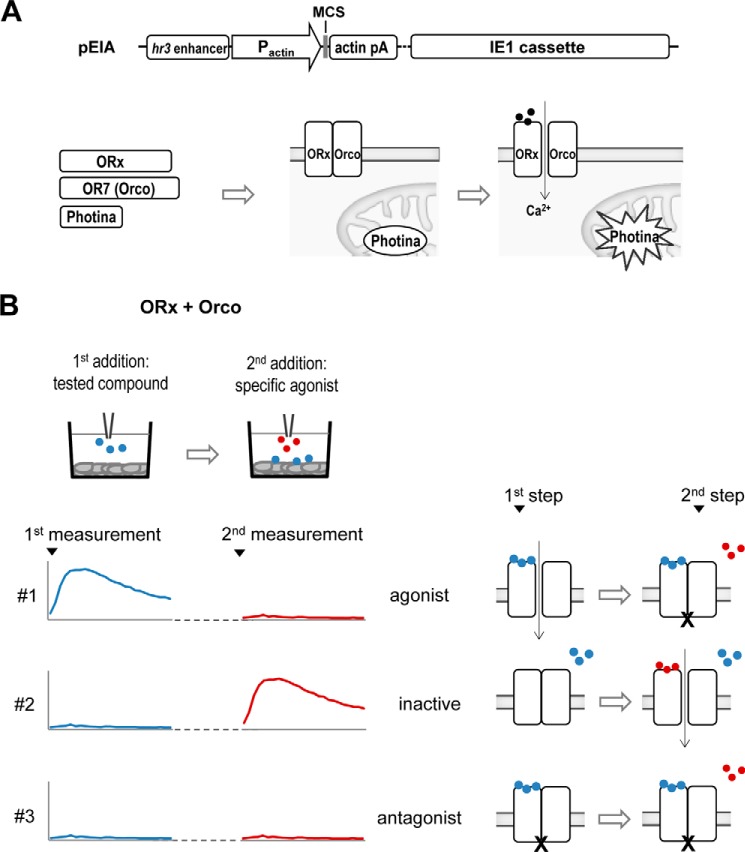

FIGURE 1.

Assays for functional analysis of mosquito ORs and analysis of compound effects on OR function. A, the pEIA vector is used for the heterologous expression of ORx, Orco, and Photina® in lepidopteran insect cells. Upon the addition of specific ligands (solid circles) to cells expressing the two subunits of the ion channel complex (depicted is an oversimplified consensus model based on current knowledge) and the photoprotein, increased luminescence is measured. MCS, multiple cloning sites (as per Refs. 30–32). B, the two-step addition protocol. In the first addition cycle, different compounds (in blue) are added to each well containing cells expressing specific ORs, while in the second cycle, the specific agonist (in red) of the receptor is applied. As exemplified here, compound #1 can be classified as agonist, compound #3 can be classified as antagonist, whereas #2 is not recognized by this particular OR heteromer.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Trichoplusia ni BTI-Tn 5B1-4 HighFiveTM cells (37) were used throughout this study. The cells were maintained at 28 °C and were grown in IPL-41 insect cell culture medium (Genaxxon Bioscience GmbH), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma or Biosera). Transfection was performed with the Escort IV reagent (Sigma) according to standard protocols.

Expression of Mosquito ORs and Bioluminescence Assays

To monitor olfactory receptor activation, HighFiveTM cells were transfected with pEIA plasmids expressing Orco, ORx, and Photina® at ratios of 1:1:2, with 2 μg of total plasmid DNA per 106 cells. In experiments involving analyses of single subunits (Orco or ORx), the ratio of plasmids expressing Orco or ORx and Photina® was 1:1. The functional assay was performed 2–4 days after transfection. Briefly, the cells were washed and resuspended in Ringer's solution (140 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm glucose, pH 7.2), and native coelenterazine was added at a concentration of 5 μm. This was followed by transfer of the cell suspension to a white 96-well plate (200,000–300,000 cells/well) and further incubation at room temperature in the dark for at least 2 h. Luminescence was measured in an Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd). The addition of chemicals was either by using the autoinjector, allowing rapid injection and simultaneous reading, or manually outside the plate reader. In the latter case, baseline luminescence was usually recorded for 20 s, after which the compounds were added with the change in luminescence recorded every 3–7 s for a further period of up to 120 s.

To test the suitability of the expression system for use as screening platform for olfactory receptor agonists and antagonists in a single compound screen, as was previously reported for other ion channels (38), olfactory receptors (28), and nuclear receptors (39), cells co-expressing selected A. gambiae ORs with Orco and Photina® were transferred to 96-well plates. Following coelenterazine loading, the cells were subjected to two cycles of compound additions (see Fig. 1B). In the first cycle, compounds screened for effects on olfactory receptors were added to the cells, while in a second application, the cognate ligand for each receptor (odorant for ORx-Orco and Orco agonist for Orco alone) was added to all wells. Between the two applications, cells were allowed to return to baseline luminescence levels (15–20 min). The same design was used for testing the effects of the selected repellents.

Data Analysis and Curve Fitting

Initial data acquisition and analyses were performed using i-Control 1.3 (Tecan), while curve fitting and EC50/IC50 calculations were done using GraphPad Prism 4.0 for Windows. Specifically, concentration-response data were fitted to the equation for non-linear regression, sigmoidal dose response: Y = Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1 + 10∧(LogEC50 − X)), where Y is percentage of response at a given concentration for a given odorant; X is logarithm of concentration, with Top and Bottom values being the maximal and minimal percentage of responses for the given odorant, as normalized to 100%, set for the maximal response for a specific OR against all tested odorants, and the EC50 is the odorant concentration yielding a half-maximal response.

Luminescence value comparisons between independent experiments were made relative to normalization standards with cognate ligands (i.e. 100 μm 4-methylphenol and indole for OR1 and OR2, respectively) applied in every given experiment and considered to provide 100% of maximal response for the specific set of experiments. Unless otherwise stated, results represent the means of 2–3 independent experiments.

RESULTS

Mosquito ORs Produce Orco-dependent and Odorant-specific Ionotropic Responses in Lepidopteran Cells

We have previously reported on the expression of A. gambiae ORs in a lepidopteran insect cell-based system that directs efficient synthesis and correct localization of recombinant receptors in the expressing cells (34). To establish the functionality of the expressed receptors in this system and develop a platform suitable for quantitative assessments of receptor activity, we introduced into the cells a reporter construct for a Ca2+-activated photoprotein, Photina® (36) (Fig. 1A), which functions similarly to aequorin, but has enhanced quantum yield (36, 40). Upon activation of OR ligand-gated cation channels, which cause Ca2+ influx into the cells, Photina® undergoes a conformational change leading to oxidation of coelenterazine and emission of blue light proportional to the Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1A).

Following co-expression of OR1 and OR2 with Orco and Photina®, cellular luminescence responses were monitored after the addition of specific ligands known to activate each OR (19, 20, 41, 42). As shown in Fig. 2A, specific responses could be detected in cells expressing OR1+Orco upon administration of 4-methylphenol, whereas cells expressing OR2+Orco responded, as expected, to indole. On the other hand, cells expressing OR9+Orco responded, as expected, to the addition of 2-ethylphenol (data not shown). The presence of Orco was obligatory for functional responses to occur as no responses were obtained in its absence (Fig. 2A). Co-expression of Gα16 was also not able to substitute for a functional Orco in stimulating agonist-dependent activity of OR2 and OR1 to any appreciable degree (Fig. 2, B and C).

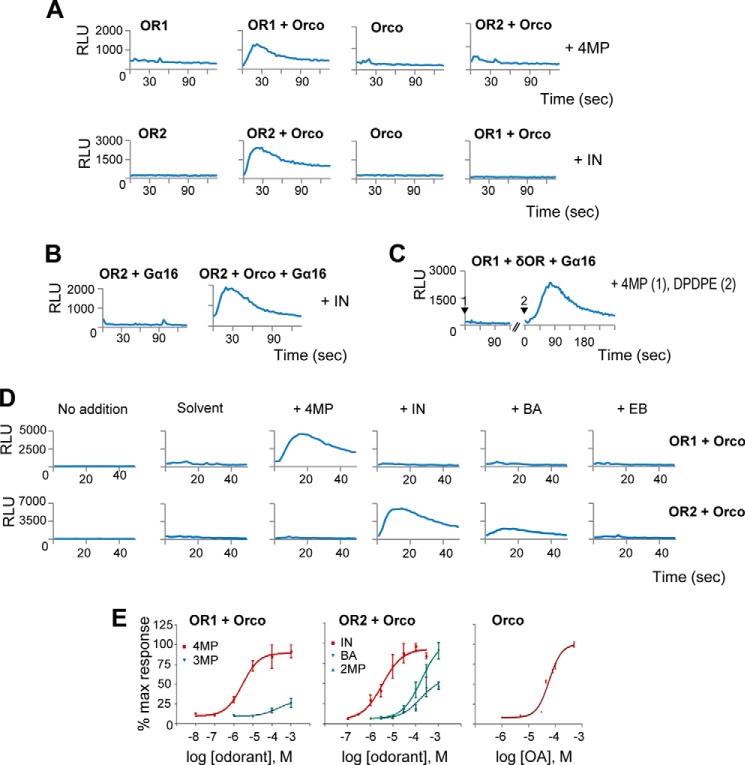

FIGURE 2.

Functional expression and characterization of mosquito ORs. A, selective responses to 4-methylphenol (4MP) and indole (IN) can be monitored from cells expressing OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco, respectively, upon challenging with the cognate ligand at 10 μm concentration (shown are time course of luminescence changes over time; RLU, relative light units). No responses are measured from ORx alone- or Orco alone-expressing cells, even at higher agonist concentration, showing that coexpression of ORx and Orco is required. B, the presence of Gα16 protein does not stimulate agonist-dependent activity of OR2 to any appreciable degree in cells expressing OR2/Gα16 challenged with indole at 10 μm. C, responses of cells expressing OR1/δOR/Gα16 to sequential administration of 4-methylphenol at 100 μm (arrowhead 1) and the δ-opioid receptor ligand DPDPE at 1 μm (arrowhead 2) are shown. In the latter case, Gα16-dependent phospholipase C coupling of the co-expressed murine δ-opioid receptor was clearly observed, as expected. The later calcium response is also much slower than direct calcium ion flux through ion channels, as expected for G-protein-coupled receptor downstream signaling, whereas lower concentrations of agonist, in the nm range (data not shown), were sufficient for activation of the G-protein-coupled receptor relative to those required for OR activation. D, responses are ORx-specific and odorant-selective. Cells expressing OR1/Orco or OR2/Orco were challenged with 4-methylphenol, indole, benzaldehyde (BA), and ethyl butyrate (EB) at 100 μm concentration. E, dose-response curves for OR1, OR2, and Orco. The red curves correspond to the most potent ligands, 4-methylphenol for OR1 (EC50 = 2.8 × 10−6, n = 2) and indole for OR2 (EC50 = 3.4 × 10−6, n = 2). The maximal response of each receptor to the administration of its cognate agonist was used for normalization of all other responses for the same receptor. 3MP denotes 3-methylphenol; 2MP denotes 2-methylphenol; OA denotes Orco agonist (OrcoRAM2). % max response, percentage of maximum response. Error bars indicate mean ± S.D.

To further deduce OR response specificity and potency differences, luminescence responses were monitored after the addition of selected compounds known to activate each OR (19, 20, 41, 42). As shown by the examples presented in Fig. 2D and further quantified in Fig. 2E, specific responses could be detected in cells expressing OR1+Orco upon administration of 4-methylphenol (and to a lesser extent 3-methylphenol), whereas cells expressing OR2+Orco responded, as expected, to indole and, to a lesser extent, benzaldehyde. In contrast, no responses could be detected in cells expressing either OR1+Orco or OR2+Orco following administration of ethyl butyrate (Fig. 2D). With a higher concentration of 4-methylphenol, a small response could also be detected in OR2+Orco-expressing cells (data not shown and Fig. 3A). Besides the specific odorants discussed here, other chemicals have also been tested with comparable results relative to previously reported studies (19, 20, 41, 42).

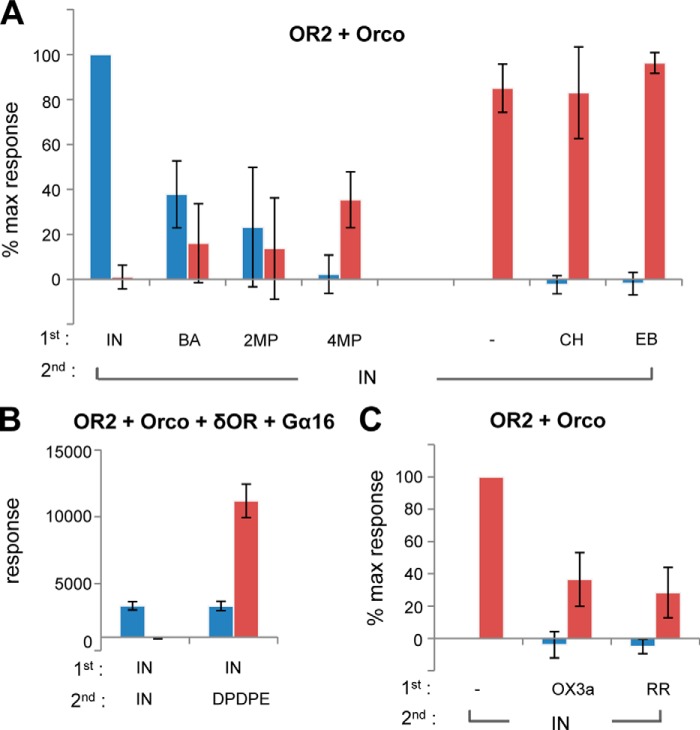

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of compound effects on Anopheles OR function. A, responses of cells expressing OR2/Orco to two applications of compounds, as described for Fig. 1B. In the first application (blue bars), cells in different wells were challenged with solvent, indole (IN), benzaldehyde (BA), 2-methylphenol (2MP), 4-methylphenol (4MP), cyclohexanone (CH), and ethyl butyrate (EB), each at a concentration of 100 μm. The second addition (red bars; specific agonist indole at 100 μm added to same cells) was performed after the luminescence had returned to baseline levels (n = 3). B, cells expressing OR2, Orco, δOR, and Gα16 were initially challenged with indole (100 μm), and subsequently, in the second cycle, with either 100 μm indole or 1 μm of the δ-opioid receptor agonist DPDPE. The secondary response was only abolished in the former but not the latter case (n = 3). C, partial inhibition of responses to indole of OR2/Orco-expressing cells by 100 μm of ruthenium red (RR) or OX3a could be demonstrated with this design (n = 3 and 5, respectively). % max response, percentage of maximum response. Error bars indicate mean ± S.D.

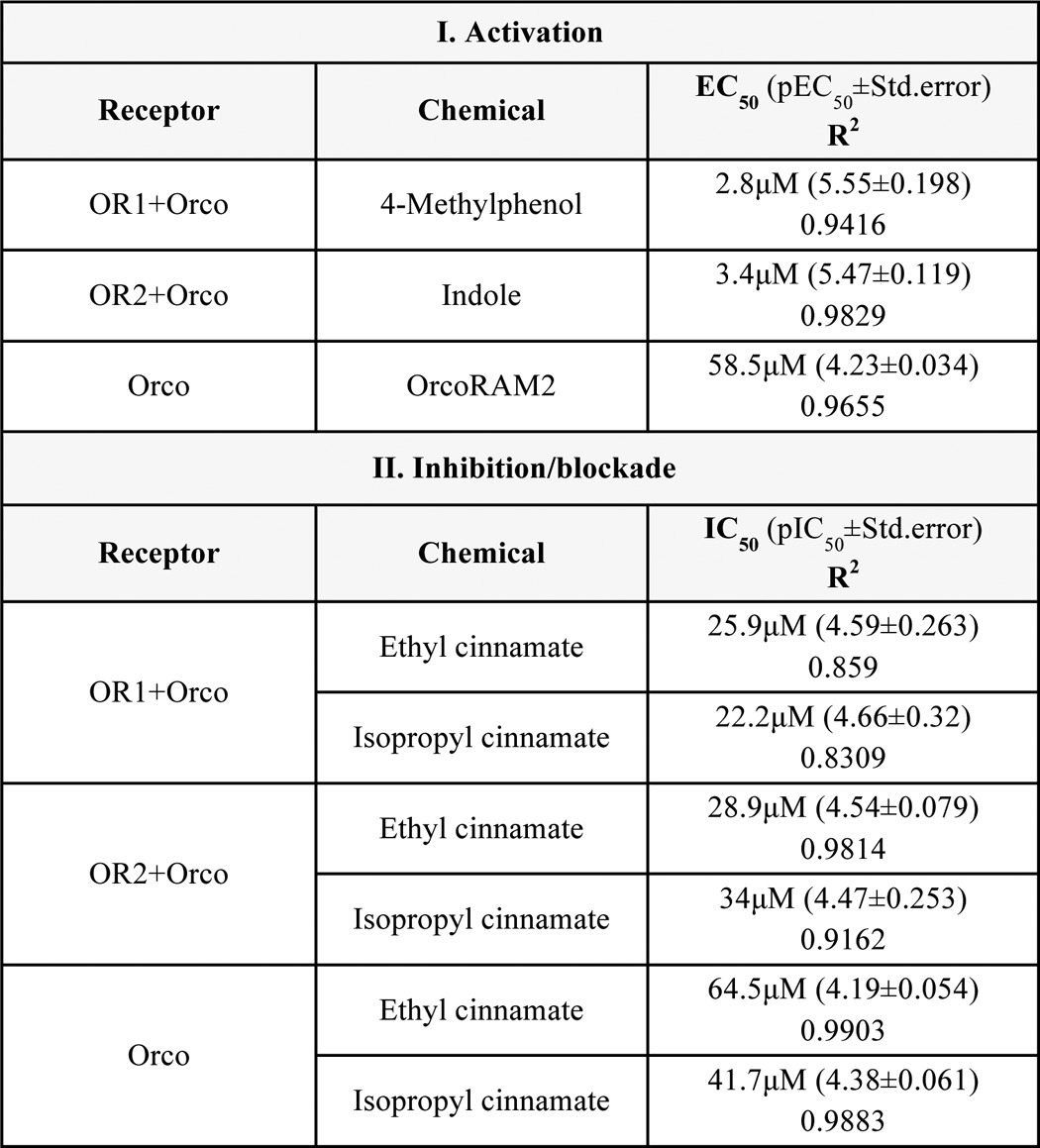

The dose-response curves and derived EC50 values from the agonist-induced luminescence for OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco heteromers distinguish agonists of varying efficacies and potencies (Fig. 2E). Thus, EC50 values of 2.8 and 3.4 μm were determined for OR1/Orco against 4-methyl phenol and for OR2/Orco against indole, respectively (Fig. 2E and Table 2). Additionally, the dose-response curves of Orco to Orco agonists such as OrcoRAM2 revealed values in the order of 60 μm (Fig. 2E and Table 2). In general, when expressed in lepidopteran cells, all tested mosquito receptors were found to be functional and display the same basic specificities as those determined using the Xenopus oocyte and Drosophila empty neuron systems (19, 20, 41). Specifically, OR1 was found to respond to 4- and 3-methylphenol, and OR2 was found to respond to indole, benzaldehyde, and 2-methylphenol, with the overall response patterns and dose-response profiles for the examined ligands and receptors (4MP > 3MP for OR1, and IN > BA > 2MP for OR2 (see Table 1 for definitions and structures)) being in good general agreement with those obtained for the same receptors from frog oocytes with two-electrode voltage clamp (19).

TABLE 2.

EC50 and IC50 values from concentration-dependent response curves

Summarized are values from curves presented in Figs. 2E, 4C, and 5B. EC50, half maximal effective concentration; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; pEC50, negative logarithm of the EC50 (−logEC50); pIC50, negative logarithm of the IC50 (−logIC50); Std. error, S.E. reported by GraphPad Prism for calculated logEC50/logIC50; R2, measure of goodness of fit.

A Convenient Assay for Initial Assessment of Specific Chemical Compound Effects on the Functionality of Olfactory Receptors

To investigate the effects of specific chemical compounds on the functionality of olfactory receptors, we employed an assay that permitted the easy classification of examined compounds into agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, or inert, i.e. not displaying any activity against the tested receptors, in one round of compound testing. The assay, which is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1B, relies on two sequential additions of compounds to cells expressing specific receptor heteromers and the reporter Photina® construct, and recordings of the differential luminescence responses obtained after each addition, which depend on the nature of the chemical of the first addition. Specifically, the compound of unknown function under examination is added first at a relatively high concentration (100 μm), and this is followed 10–20 min later by the addition of the specific agonist at the same concentration of 100 μm, which usually corresponds to an EC90 or greater, in the same microtiter well. This assay, performed in 96-well format with no wash steps in between, allows the distinction of compounds under investigation into receptor agonists (+/− for primary/secondary receptor responses, respectively; Fig. 1B, #1), non-active (−/+ responses; Fig. 1B, #2), or antagonists (−/− responses; Fig. 1B, #3). It should be noted that following a maximal primary response triggered by a receptor-specific agonist in cells expressing the corresponding receptor heteromer, the cells do not respond to a second addition of the same or a different agonist of similar specificity and potency (Fig. 1B, #1 and Fig. 3A), presumably due to temporary receptor inactivation that is gradually reversed over time following removal of the agonist (data not shown). On the other hand, partial agonists producing a lower than maximal primary response, produce a significantly lower secondary response upon the addition of the receptor-specific agonist ((+)/(+) responses; Fig. 3A), apparently because of partial receptor occupancy and correspondingly reduced receptor inactivation.

Typical system validation examples employing the OR2/Orco heteromer are presented in Fig. 3A. Indole, the specific OR2 agonist, triggers a primary response but no secondary functional response upon a new addition of indole to the cells. This effect appears to be specific for the cognate pair of OR heteromer/ligand used rather than being caused by exhaustion of the photoprotein as cells co-transfected with OR2+Orco and δ-opioid receptor respond positively to the addition of DPDPE, the specific δ-opioid receptor ligand, following the primary indole addition (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, benzaldehyde, 2-methylphenol, and 4-methylphenol, partial OR2 agonists (Fig. 2E and data not shown), trigger partial agonist primary and secondary responses (Fig. 3A), whereas ethyl butyrate and cyclohexanone, which do not represent ligands for the specific receptor, do not trigger a primary functional response but allow the opening of the olfactory channel upon a secondary addition of indole (Fig. 3A). Controls were included both at the beginning and at the end of each set of experiments to ascertain the stability of OR2 responses to indole during the course of the experiments (Fig. 3A).

Given the absence of known antagonists for any ORx receptors, the case of inhibition in the context of a receptor heteromer was tested through the use of one of the recently reported synthetic phenyl-thiophene-carboxamide Orco antagonists, OX3a (16), and ruthenium red (43). OX3a has been shown to inhibit non-competitively odorant activation of a heteromeric OR of Culex quinquefasciatus and was assumed to block general odorant-dependent OR activation as the originally characterized chemical of this class of Orco antagonists (16). On the other hand, ruthenium red, a nonspecific cation channel blocker, inhibits the function of many insect odorant receptors (1, 44, 45). In the case of these inhibitors, their addition to the cells did not induce any functional responses, but did reduce receptor activation upon a secondary addition of indole (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained from other tested ORx/Orco heteromers involving ORx subunits of known ligand specificities (data not shown).

Olfactory Receptor Inhibition by Specific Mosquito Repellents

A number of repellents previously reported to be active against different Anopheles and Aedes species were subsequently examined for their possible effects on various olfactory receptors of A. gambiae. Prominent among the initially examined repellents were DEET (46, 47), ethyl cinnamate (EC (47, 48)), isopropyl cinnamate (IPC (47–49)), cuminic alcohol (CMA (47, 50)), and carvacrol (CRV (47, 51)) (Table 1). Except for DEET, which has been studied extensively, to the best of our knowledge, no information concerning the molecular mechanism of action has been available for these repellents.

The chosen repellents were tested initially at a concentration of 100 μm on cells expressing OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco heteromers. As is shown in Fig. 4A, none of the tested repellents displayed agonist activity upon addition to the cells. Judging from the results of the secondary addition of 4-methylphenol or indole to the cells expressing OR1+Orco or OR2+Orco, respectively, EC, CRV, and IPC caused essentially complete inhibition of OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco receptor function at this concentration (Fig. 4A). The effect of CMA on both receptor heteromers was considerably less pronounced with the inhibition amounting to 30–40%, whereas no noticeable inhibitory action was exerted by DEET on the tested receptors. Similar inhibitory effects were also recorded with other mosquito receptor heteromers examined (data not shown).

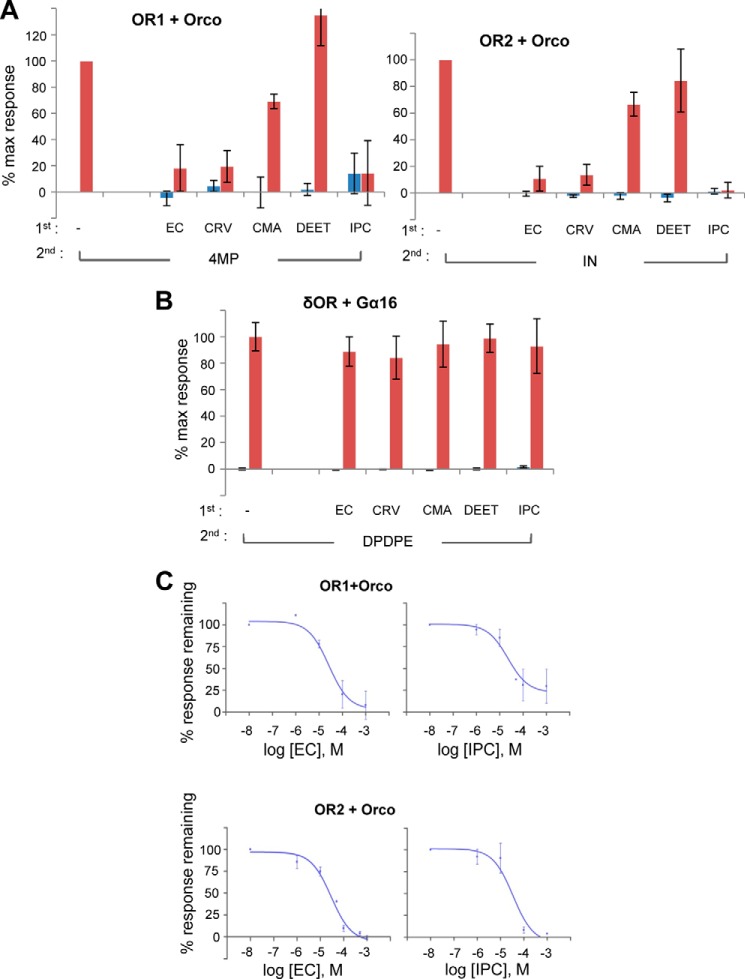

FIGURE 4.

Screening for effects of selected mosquito repellents on A. gambiae ORs. A, OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco heteromer-expressing cells were tested for primary responses to 100 μm of each repellent (ethyl cinnamate (EC), carvacrol (CRV), cumin alcohol (CMA), DEET, and isopropyl cinnamate (IPC)) (blue bars), and inhibition of secondary responses to the cognate agonists 4-methylphenol (4MP) and indole (IN), respectively, added in the same wells at 100 μm (red bars). Responses are presented as the percentages of the response of each receptor heteromer to the cognate ligand in the absence of any candidate antagonist (n = 2–8).% max response, percentage of maximum response. B, the effects of the same repellents at 100 μm on the functionality of the δ-opioid receptor and its downstream phospholipase C-coupled signaling responses to 10 μm DPDPE (n = 2). C, dose-response inhibition curves for ethyl cinnamate and isopropyl cinnamate against OR1/Orco- and OR2/Orco-expressing cells following stimulation with 100 μm of the respective cognate agonists, 4-methylphenol and indole. (n = 2 and 3, respectively). Error bars indicate mean ± S.D.

To ensure that the observed inhibition in Ca2+ influx into the cells was due to specific inhibition of olfactory receptor function, rather than general off-target effects, e.g. at the level of the cellular membranes or the calcium photoprotein, the same compounds were examined for their effects on cells transfected with the murine δ-opioid receptor (52, 53) along with the human Gα16 (54) (presented in Figs. 2C and 3B). As shown in Fig. 4B, administration of the δ-opioid agonist DPDPE to cells expressing the specific receptor in the presence of a high concentration of the tested repellents did not affect plasma membrane-anchored opioid receptor signaling and the ensuing Ca2+ release from intracellular endoplasmic reticulum membrane stores (Fig. 4B).

Dose-response curves for the inhibition exerted by two of the repellents displaying highly inhibitory actions, ethyl cinnamate and isopropyl cinnamate, against OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco heteromers were constructed using 100 μm concentrations (>EC90) of the cognate ligands 4-methylphenol and indole, respectively, as agonists for the secondary additions. For ethyl cinnamate, the rates of inhibition (IC50 values) of the two heteromers were found to be very similar, 25.9 and 28.9 μm, respectively (Fig. 4C). Inhibition by isopropyl cinnamate was also found to be in the same order of magnitude, with IC50 values of 22.2 and 34 μm, respectively, for OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco (Fig. 4C).

Orco Antagonism Is a Cause of Interference with Mosquito Olfactory Receptor Function

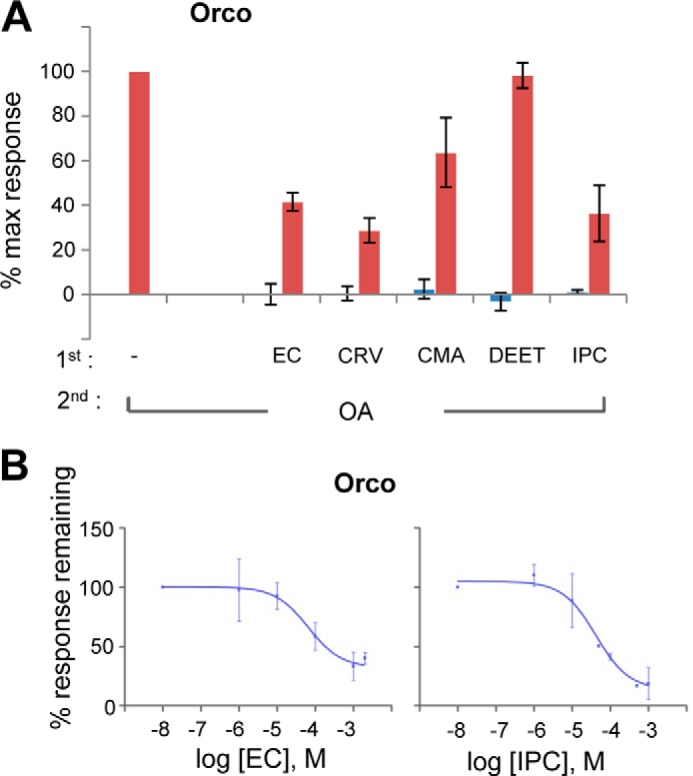

Given the similarity of the inhibitory effects of the tested repellents on different olfactory receptor heteromers, we examined the possibility that the inhibition may be exerted at the level of Orco, the common subunit of olfactory receptor heteromers. Although we found Orco to be similarly responsive to both Orco agonists tested, VUAA1 (17) and OrcoRAM2 (11) (data not shown), the latter was used for detailed investigations (shown also in Fig. 2E). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 5A, when 100 μm of each repellent was added to cells expressing Orco, all examined repellents, except DEET, exerted some level of inhibitory effect on Orco function as the responses to the secondary addition of 100 μm of the Orco agonist OrcoRAM2 to the cells were considerably reduced (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of selected mosquito repellents on A. gambiae Orco. A, responses of Orco homomer-expressing cells to 100 μm of the tested repellents, ethyl cinnamate (EC), carvacrol (CRV), cumin alcohol (CMA), DEET, and isopropyl cinnamate (IPC) (blue bars), and 100 μm OrcoRAM2 (OA) as secondary addition in the same wells (red bars). Responses are presented as the percentages of the response to the Orco agonist in the absence of any candidate antagonist (n = 2). % max response, percentage of maximum response. B, dose-dependent inhibition curves for Orco-expressing cells, in the presence of increasing concentrations of ethyl cinnamate and isopropyl cinnamate, to 100 μm of the Orco agonist OrcoRAM2 (n = 3 and 4, respectively). Error bars indicate mean ± S.D.

The dose-response curves for the inhibition exerted on Orco homomers by the tested repellents (Fig. 5B) revealed IC50 values of 64.5 and 41.7 μm for ethyl cinnamate and isopropyl cinnamate, respectively, somewhat higher than those exerted on the function of OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco heteromers (Fig. 4C). This finding suggests that the repellent action observed in the context of the heteromer (Fig. 4) likely originates from interference with Orco function. Interestingly, DEET did not conform to the behavior of the rest of the repellents at the tested concentration.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we present the use of a lepidopteran insect cell-based assay for quantitative assessments of the functional properties of A. gambiae olfactory receptors. Besides high levels of receptor expression achieved in the insect cells (30, 34) through the use of plasmid-based expression vectors employing genetic control elements of the silkmoth and its baculovirus (31, 32), the major functional component of the assay system is a construct directing robust expression of Photina®, a Ca2+-activated photoprotein (36). The activation of this photoprotein provides a luminescence-based readout reporting quantitatively on increases of intracellular Ca2+ ions; hence, in this study, ion channel activity upon administration of cognate olfactory receptor agonists could be studied.

Our system may be considered as an effective alternative to the two major systems used for studying insect olfactory receptor function, the Drosophila empty neuron (20) and Xenopus oocytes (19), as well as other heterologous cell-based expression systems employing cultured insect (21, 24–26) or mammalian cells (22, 23, 27, 28) in conjunction with fluorescent calcium indicator dyes. In contrast to these systems, which have some important drawbacks (see the Introduction), the new system combines the simplicity of handling with a reporter photoprotein that only luminesces when the levels of intracellular Ca2+ increase as a result of olfactory channel activation. Because it allows automated luminescence measurements of total cell populations seeded in microtiter plates in a mix-and-measure fashion and with high signal-to-noise ratios in the absence of wash steps, this system is very suitable for functional screens for ligand discovery at a medium-to-high throughput scale.

As already mentioned, a version of Photina® targeted to the mitochondria via a specific leader sequence (36) was employed in our optical cell-based assay. The reasons for choosing the mitochondrially targeted version of Photina® over the cytoplasmic were, first, the ∼10-fold higher responses reported for the mitochondrial photoprotein over the cytoplasmic one, at least for the case of studied G-protein-coupled receptors and, secondly, the slower, and thus more accurate, detection of channel activation reaction kinetics due to the longer time assumed to be needed for the Ca2+ wave to reach the mitochondria-localized Photina®. Moreover, we have not noticed any artifactual responses related to metabolic stress in our system as functional responses from cells expressing specific receptors were obtained only after administration of cognate ligands at functionally relevant concentrations.

The specificities of OR responses determined in the lepidopteran insect cell system have been in good agreement with those determined using the Drosophila empty neuron and Xenopus oocytes expression systems (19, 20). As far as relevant potencies and efficacies are concerned, our results can be compared directly with those determined using the frog oocyte system (19), which can be considered as more accurate and quantitative descriptors of receptor pharmacology, as in the Drosophila system only one very high, and thus not physiologically relevant, concentration was applied. Briefly, the tested ORs were found to recognize the same ligands, from the panel of chemicals used for confirmation, with similar dose-dependent responses, 4MP > 3MP for OR1 and IN > BA > 2MP for OR2, respectively (Fig. 2E) (see Table 1 for definitions and structures). The calculated EC50 values (Table 2) were somewhat higher than the ones reported with the electrophysiological methods, which were in the high nanomolar range (19). The Orco homomer was also found to respond to Orco agonists, as expected.

The sequential addition protocol employed in this study, initially validated using known odorants, ruthenium red and an Orco antagonist, made possible the classification of compounds added in the first instance to cells expressing specific receptors into partial or full receptor agonists, antagonists, or inert in terms of ligand activities (Figs. 1B and 3A). Using this assay, it has been possible to deduce that all but one of several examined compounds known to represent powerful mosquito repellents act as olfactory receptor inhibitors reducing receptor activation upon subsequent agonist addition (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the exception has been the most widely used repellent DEET, which was not found to act as an agonist or antagonist for any of the examined A. gambiae olfactory receptors in the tested concentration of 100 μm (Fig. 4A).

The fact that the tested repellents were found to inhibit the function of all receptors examined in this study led to the examination of the possibility and demonstration that Orco, the common receptor subunit of the functional receptor complex, was a target of inhibition (Fig. 5, A and B). Although further studies are warranted, this finding and, most importantly, the dose-response curves for the inhibition, suggest that the inhibitory action of the tested repellents on the receptor heteromers under examination is likely due to Orco inhibition, with the ORx constituents contributing little, if any, to it. Whether the somewhat lower IC50 values of the repellents for the receptor heteromers (Table 2) indeed reflect enhanced affinities for Orco because of structural changes of the latter in the context of the heteromers should be investigated further.

It should be noted further that although the synthesis of several compounds acting as Orco antagonists has been reported recently (15, 16, 18), to our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating antagonist action on an anopheline Orco associated with powerful repellency on anopheline and other mosquitoes. Likely important factors that contribute to the repelling capacity of the Orco antagonists reported here are their physical properties, such as volatility and efficient recognition by several mosquito odorant-binding proteins (55), at least in vitro, which has been demonstrated for some of these compounds in the A. gambiae system.3 The fact that a highly conserved protein such as Orco is a major target of the tested repellent compounds may also explain why the specific repellents are effective against mosquito species other than A. gambiae, as well as other insects (47, 48, 50, 51). The demonstrated Orco involvement also leads us to postulate that, at least in the case of the two repellents studied in more detail here, their mosquito “repellence” action should probably be interpreted as a passive disorientation effect, which reflects an essential anosmia caused by the blocking of a large complement of olfactory receptors rather than an active one causing repulsion to the approaching mosquitoes.

Finally, the finding that DEET behaves differently than the remaining repellents tested in this study was not unexpected, as a number of studies have suggested different modes of function for this repellent. These include: activation of specific ORs (the excito-repellent hypothesis (56–58)); inhibition of specific ORs responding to attractants (59, 60); and/or modulation of many ORs causing an olfactory confusion similar in effect but not in molecular terms to the one postulated above for the repellents tested in this study (10, 61). In addition, the involvement of ionotropic (62) and gustatory receptors (63) in Drosophila was also demonstrated. Therefore it seems that, in contrast to the case of the Orco function-inhibiting repellents presented in this study, the molecular targets for DEET are fundamentally different. In fact, no inhibition of Aedes aegypti Orco could be observed even at 10 mm DEET (11). Nevertheless, the inhibitory effects of DEET on a Drosophila OR heteromer, OR47a/OR83b, with a calculated IC50 value of 929 μm in the Xenopus oocyte system have been reported (13). In the same assay system, some inhibitory effects of DEET were also documented for a number of insect olfactory receptors including A. gambiae OR1/Orco and OR2/Orco (59). In these latter cases, the inhibition ranged from a low of 30% to a maximum of ∼55% at a DEET concentration of 1 mm (59).

In view of the fact that the effects of repellents with secondary (allosteric) recognition sites may be observed at high repellent concentrations (9), we consider questionable whether modulations of odorant receptor activity by high concentrations of DEET are physiologically relevant. Such reservations notwithstanding, however, it should also be of interest to investigate whether the repellents studied here have additional sensory targets, in analogy to DEET or citronellal, which has been reported to target both TRPA1 and Orco-dependent pathways in Drosophila (64).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sabrina Corazza (AXXAM SpA, Milan, Italy) for provision of Photina® plasmid, Prof. Richard D. Newcomb (The New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Limited, Auckland, New Zealand) for the generous gift of a sample of VUAA1, used in initial studies, Dr. Dimitrios Kontogiannatos (Agricultural University of Athens) for the gift of ruthenium red, and Dr. Maria Konstantopoulou (Chemical Ecology and Natural Products Laboratory, National Centre for Scientific Research (NCSR) “Demokritos”) for provision of carvacrol. We also thank Alexandra Amaral-Psarris for expert technical assistance, our laboratory colleagues Drs. Luc Swevers and Vassiliki Labropoulou for their constructive comments, Dr. Zafiroula Georgoussi (Signal Transduction and Molecular Pharmacology Group, IB-A, NCSR “Demokritos”) for the long and helpful discussions and suggestions, and Dr. Spyros Zographos (National Hellenic Research Foundation) for useful suggestions.

This work was supported by a grant from the European Union (FP7-222927, ENAROMaTIC – European Network for Advanced Research on Olfaction for Malaria Transmitting Insect Control).

K. Iatrou, K. Koussis, M. Konstantopoulou, S. E. Zographos, and G. Kythreoti, unpublished data.

- OR

- odorant receptor

- DEET

- N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide

- DPDPE

- [d-Pen2,d-Pen5]enkephalin

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- Orco

- olfactory receptor coreceptor

- OX3a

- Orco antagonist 3a

- OrcoRAM2

- Orco receptor activator molecule 2

REFERENCES

- 1. Nakagawa T., Sakurai T., Nishioka T., Touhara K. (2005) Insect sex-pheromone signals mediated by specific combinations of olfactory receptors. Science 307, 1638–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sato K., Pellegrino M., Nakagawa T., Nakagawa T., Vosshall L. B., Touhara K. (2008) Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature 452, 1002–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wicher D., Schäfer R., Bauernfeind R., Stensmyr M. C., Heller R., Heinemann S. H., Hansson B. S. (2008) Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature 452, 1007–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carey A. F., Carlson J. R. (2011) Insect olfaction from model systems to disease control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12987–12995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leal W. S. (2013) Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suh E., Bohbot J. D., Zwiebel L. J. (2014) Peripheral olfactory signaling in insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 6, 86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leal W. S. (2010) Behavioural neurobiology: the treacherous scent of a human. Nature 464, 37–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeGennaro M., McBride C. S., Seeholzer L., Nakagawa T., Dennis E. J., Goldman C., Jasinskiene N., James A. A., Vosshall L. B. (2013) orco mutant mosquitoes lose strong preference for humans and are not repelled by volatile DEET. Nature 498, 487–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dickens J. C., Bohbot J. D. (2013) Mini review: Mode of action of mosquito repellents. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 106, 149–155 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bohbot J. D., Dickens J. C. (2010) Insect repellents: modulators of mosquito odorant receptor activity. PLoS One 5, e12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bohbot J. D., Dickens J. C. (2012) Odorant receptor modulation: ternary paradigm for mode of action of insect repellents. Neuropharmacology 62, 2086–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pask G. M., Bobkov Y. V., Corey E. A., Ache B. W., Zwiebel L. J. (2013) Blockade of insect odorant receptor currents by amiloride derivatives. Chem. Senses 38, 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Röllecke K., Werner M., Ziemba P. M., Neuhaus E. M., Hatt H., Gisselmann G. (2013) Amiloride derivatives are effective blockers of insect odorant receptors. Chem. Senses 38, 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen S., Luetje C. W. (2014) Trace amines inhibit insect odorant receptor function through antagonism of the co-receptor subunit. F1000Res 3, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen S., Luetje C. W. (2012) Identification of new agonists and antagonists of the insect odorant receptor co-receptor subunit. PLoS One 7, e36784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen S., Luetje C. W. (2013) Phenylthiophenecarboxamide antagonists of the olfactory receptor co-receptor subunit from a mosquito. PLoS One 8, e84575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones P. L., Pask G. M., Rinker D. C., Zwiebel L. J. (2011) Functional agonism of insect odorant receptor ion channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8821–8825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones P. L., Pask G. M., Romaine I. M., Taylor R. W., Reid P. R., Waterson A. G., Sulikowski G. A., Zwiebel L. J. (2012) Allosteric antagonism of insect odorant receptor ion channels. PLoS One 7, e30304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang G., Carey A. F., Carlson J. R., Zwiebel L. J. (2010) Molecular basis of odor coding in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4418–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carey A. F., Wang G., Su C. Y., Zwiebel L. J., Carlson J. R. (2010) Odorant reception in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Nature 464, 66–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson A. R., Wanner K. W., Trowell S. C., Warr C. G., Jaquin-Joly E., Zagatti P., Robertson H., Newcomb R. D. (2009) Molecular basis of female-specific odorant responses in Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forstner M., Breer H., Krieger J. (2009) A receptor and binding protein interplay in the detection of a distinct pheromone component in the silkmoth Antheraea polyphemus. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5, 745–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grosse-Wilde E., Svatos A., Krieger J. (2006) A pheromone-binding protein mediates the bombykol-induced activation of a pheromone receptor in vitro. Chem. Senses 31, 547–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jordan M. D., Anderson A., Begum D., Carraher C., Authier A., Marshall S. D., Kiely A., Gatehouse L. N., Greenwood D. R., Christie D. L., Kralicek A. V., Trowell S. C., Newcomb R. D. (2009) Odorant receptors from the light brown apple moth (Epiphyas postvittana) recognize important volatile compounds produced by plants. Chem. Senses 34, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kiely A., Authier A., Kralicek A. V., Warr C. G., Newcomb R. D. (2007) Functional analysis of a Drosophila melanogaster olfactory receptor expressed in Sf9 cells. J. Neurosci. Methods 159, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smart R., Kiely A., Beale M., Vargas E., Carraher C., Kralicek A. V., Christie D. L., Chen C., Newcomb R. D., Warr C. G. (2008) Drosophila odorant receptors are novel seven transmembrane domain proteins that can signal independently of heterotrimeric G proteins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 770–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corcoran J. A., Jordan M. D., Carraher C., Newcomb R. D. (2014) A novel method to study insect olfactory receptor function using HEK293 cells. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 54, 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rinker D. C., Jones P. L., Pitts R. J., Rutzler M., Camp G., Sun L. J., Xu P. X., Dorset D. C., Weaver D., Zwiebel L. J. (2012) Novel high-throughput screens of Anopheles gambiae odorant receptors reveal candidate behaviour-modifying chemicals for mosquitoes. Physiol Entomol. 37, 33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vosshall L. B., Hansson B. S. (2011) A unified nomenclature system for the insect olfactory coreceptor. Chem. Senses 36, 497–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Douris V., Swevers L., Labropoulou V., Andronopoulou E., Georgoussi Z., Iatrou K. (2006) Stably transformed insect cell lines: tools for expression of secreted and membrane-anchored proteins and high-throughput screening platforms for drug and insecticide discovery. Adv. Virus Res. 68, 113–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu M., Farrell P. J., Johnson R., Iatrou K. (1997) A baculovirus (Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus) repeat element functions as a powerful constitutive enhancer in transfected insect cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30724–30728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu M., Johnson R. R., Iatrou K. (1996) Trans-activation of a cell housekeeping gene promoter by the IE1 gene product of baculoviruses. Virology 218, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swevers L., Morou E., Balatsos N., Iatrou K., Georgoussi Z. (2005) Functional expression of mammalian opioid receptors in insect cells and high-throughput screening platforms for receptor ligand mimetics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 919–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tsitoura P., Andronopoulou E., Tsikou D., Agalou A., Papakonstantinou M. P., Kotzia G. A., Labropoulou V., Swevers L., Georgoussi Z., Iatrou K. (2010) Expression and membrane topology of Anopheles gambiae odorant receptors in lepidopteran insect cells. PLoS One 5, e15428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iatrou K., Biessmann H. (2008) Sex-biased expression of odorant receptors in antennae and palps of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 268–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bovolenta S., Foti M., Lohmer S., Corazza S. (2007) Development of a Ca2+-activated photoprotein, Photina, and its application to high-throughput screening. J. Biomol. Screen. 12, 694–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wickham T. J., Davis T., Granados R. R., Shuler M. L., Wood H. A. (1992) Screening of insect cell lines for the production of recombinant proteins and infectious virus in the baculovirus expression system. Biotechnol. Prog. 8, 391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thompson A. J., Verheij M. H., Leurs R., De Esch I. J., Lummis S. C. (2010) An efficient and information-rich biochemical method design for fragment library screening on ion channels. BioTechniques 49, 822–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Swevers L., Kravariti L., Ciolfi S., Xenou-Kokoletsi M., Ragoussis N., Smagghe G., Nakagawa Y., Mazomenos B., Iatrou K. (2004) A cell-based high-throughput screening system for detecting ecdysteroid agonists and antagonists in plant extracts and libraries of synthetic compounds. FASEB J. 18, 134–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Molokanova E., Savchenko A. (2008) Bright future of optical assays for ion channel drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 13, 14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hallem E. A., Nicole Fox A., Zwiebel L. J., Carlson J. R. (2004) Olfaction: mosquito receptor for human-sweat odorant. Nature 427, 212–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xia Y., Wang G., Buscariollo D., Pitts R. J., Wenger H., Zwiebel L. J. (2008) The molecular and cellular basis of olfactory-driven behavior in Anopheles gambiae larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6433–6438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amann R., Maggi C. A. (1991) Ruthenium Red as a capsaicin antagonist. Life Sci. 49, 849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nichols A. S., Chen S., Luetje C. W. (2011) Subunit contributions to insect olfactory receptor function: channel block and odorant recognition. Chem. Senses 36, 781–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pask G. M., Jones P. L., Rützler M., Rinker D. C., Zwiebel L. J. (2011) Heteromeric Anopheline odorant receptors exhibit distinct channel properties. PLoS One 6, e28774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kröber T., Kessler S., Frei J., Bourquin M., Guerin P. M. (2010) An in vitro assay for testing mosquito repellents employing a warm body and carbon dioxide as a behavioral activator. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 26, 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. King W. V. (1954) Chemicals Evaluated as Insecticides and Repellents at Orlando, Fla, Entomology Research Branch, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Entomology Research Branch, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hall S. A., Travis B. V., Jones H. A. (December 4, 1945) Insect-repellent composition. U. S. Patent 2,390,249 A

- 49. Christophers S. R. (1947) Mosquito repellents; being a report of the work of the mosquito repellent inquiry, Cambridge, 1943–5. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 45, 176–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kwon H. W., Kim S. I., Chang K. S., Clark J. M., Ahn Y. J. (2011) Enhanced repellency of binary mixtures of Zanthoxylum armatum seed oil, vanillin, and their aerosols to mosquitoes under laboratory and field conditions. J. Med. Entomol. 48, 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tabanca N., Bernier U. R., Ali A., Wang M., Demirci B., Blythe E. K., Khan S. I., Baser K. H., Khan I. A. (2013) Bioassay-guided investigation of two Monarda essential oils as repellents of yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 8573–8580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kieffer B. L., Befort K., Gaveriaux-Ruff C., Hirth C. G. (1992) The δ-opioid receptor: isolation of a cDNA by expression cloning and pharmacological characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 12048–12052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yasuda K., Raynor K., Kong H., Breder C. D., Takeda J., Reisine T., Bell G. I. (1993) Cloning and functional comparison of κ- and δ-opioid receptors from mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6736–6740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Amatruda T. T., 3rd, Steele D. A., Slepak V. Z., Simon M. I. (1991) Gα16, a G protein α subunit specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 5587–5591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Biessmann H., Andronopoulou E., Biessmann M. R., Douris V., Dimitratos S. D., Eliopoulos E., Guerin P. M., Iatrou K., Justice R. W., Kröber T., Marinotti O., Tsitoura P., Woods D. F., Walter M. F. (2010) The Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein 1 (AgamOBP1) mediates indole recognition in the antennae of female mosquitoes. PLoS One 5, e9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Syed Z., Leal W. S. (2008) Mosquitoes smell and avoid the insect repellent DEET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13598–13603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu P., Choo Y. M., De La Rosa A., Leal W. S. (2014) Mosquito odorant receptor for DEET and methyl jasmonate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 16592–16597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu C., Pitts R. J., Bohbot J. D., Jones P. L., Wang G., Zwiebel L. J. (2010) Distinct olfactory signaling mechanisms in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biol 8, e1000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ditzen M., Pellegrino M., Vosshall L. B. (2008) Insect odorant receptors are molecular targets of the insect repellent DEET. Science 319, 1838–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dogan E. B., Ayres J. W., Rossignol P. A. (1999) Behavioural mode of action of deet: inhibition of lactic acid attraction. Med. Vet. Entomol. 13, 97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pellegrino M., Steinbach N., Stensmyr M. C., Hansson B. S., Vosshall L. B. (2011) A natural polymorphism alters odour and DEET sensitivity in an insect odorant receptor. Nature 478, 511–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kain P., Boyle S. M., Tharadra S. K., Guda T., Pham C., Dahanukar A., Ray A. (2013) Odour receptors and neurons for DEET and new insect repellents. Nature 502, 507–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63. Lee Y., Kim S. H., Montell C. (2010) Avoiding DEET through insect gustatory receptors. Neuron 67, 555–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kwon Y., Kim S. H., Ronderos D. S., Lee Y., Akitake B., Woodward O. M., Guggino W. B., Smith D. P., Montell C. (2010) Drosophila TRPA1 channel is required to avoid the naturally occurring insect repellent citronellal. Curr. Biol. 20, 1672–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]