Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) patrol the interstitial space of peripheral tissues. The mechanisms that regulate their migration in such constrained environment remain unknown. We here investigated the role of calcium in immature DCs migrating in confinement. We found that they displayed calcium oscillations that were independent of extracellular calcium and more frequently observed in DCs undergoing strong speed fluctuations. In these cells, calcium spikes were associated with fast motility phases. IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) channels, which allow calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum, were identified as required for immature DCs to migrate at fast speed. The IP3R1 isoform was further shown to specifically regulate the locomotion persistence of immature DCs, that is, their capacity to maintain directional migration. This function of IP3R1 results from its ability to control the phosphorylation levels of myosin II regulatory light chain (MLC) and the back/front polarization of the motor protein. We propose that by upholding myosin II activity, constitutive calcium release from the ER through IP3R1 maintains DC polarity during migration in confinement, facilitating the exploration of their environment.

Keywords: calcium, cell migration, dendritic cells, IP3 receptors, myosin II

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) present antigens onto MHC molecules to T lymphocytes and are therefore strictly required for the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Immature DCs are found in most peripheral tissues, where they patrol their environment by internalizing extracellular antigens. Although in some tissues DCs appear to be rather sessile, patrolling of the ear skin and of the gut was shown to be associated with sustained DC migration (Ng et al, 2008; Tal et al, 2011; Lelouard et al, 2012). Whether these differences are due to tissue-intrinsic properties, to the involvement of distinct DC subsets, or result from tissue manipulation during experimentation is unclear. Nonetheless, the capacity of DCs to migrate in the confined environment of peripheral tissues is likely to be essential for them to efficiently carry out their immune sentinel function.

The molecular mechanisms that control DC migration have started to be addressed. Mature DCs, which are in charge of transporting antigens to lymph nodes for presentation to T cells, do not need integrin-based adhesion to migrate in 3-dimensional (3D) environments. Indeed, these cells can migrate by the force of actin polymerization at the leading edge, while the contraction of their rear by myosin II allows nucleus transport through narrow gaps (Lammermann et al, 2008; Renkawitz et al, 2009). Less is known on the mechanisms that control the migration of immature DCs. This is mainly due to the fact that (i) intra-vital imaging does not provide enough resolution to analyze intracellular protein dynamics in DCs migrating in vivo, (ii) immature DCs purified from peripheral tissues rapidly become activated in culture and therefore cannot be used for mRNA silencing and cell biological studies, and (iii) bone marrow-derived DCs, which maintain their immature phenotype in vivo, migrate poorly when plated on 2D surfaces. To circumvent these problems, we have built 1D (micro-channels) and 2D micro-fabricated devices that mimic the interstitial space of peripheral tissues to unravel the cell biological mechanisms involved in the migration of bone marrow-derived immature DCs. Using these tools, we showed that immature DC fast migration is facilitated by cell confinement and requires myosin II activity (Faure-Andre et al, 2008; Heuze et al, 2013). In addition, we observed that immature DCs migrating in confined micro-channels display important velocity fluctuations, alternating between fast and slow motility phases (Faure-Andre et al, 2008). Whether and how velocity fluctuations are regulated during DC migration in confinement is the aim of the present study.

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous intracellular signal that controls cell polarity and migration although the effector mechanisms involved are not fully understood (Brundage et al, 1991). Front-to-back Ca2+ gradients have been observed within cells migrating on 2D substrates and proposed to promote traction stress distribution and front/back coupling for persistent locomotion (Brundage et al, 1991; Lee et al, 1999). Recently, local Ca2+ increments named “Ca2+ flickers” were identified at the leading edge of keratocytes migrating in 2D as involved in directional migration in response to chemokine gradients (Wei et al, 2009, 2012). Their formation relies on the activity of the stretch-activated Ca2+ channel TRPM7 that triggers intracellular Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through IP3 receptor (IP3R) channels as well as on myosin II activity. In addition, discrete Ca2+ pulses were shown to induce local lamellipodia retraction at the front of endothelial cells migrating on 2D surfaces (Tsai & Meyer, 2012). Lamellipodia retraction results from the activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain (MLC) kinase (MLCK) that phosphorylates MLC and thereby triggers local actin contraction. However, the role of intracellular calcium dynamics in cells migrating in confinement has not been addressed.

In DCs, the role of Ca2+ signaling has mainly been investigated in the context of chemotaxis, implicating the activation of G-coupled receptors through the PtdIns(4,5)P2 (PIP2)/phospho-lipase C(PLC) pathway and the surface molecule CD38 (Lee, 2001; Partida-Sanchez et al, 2004). The Ca2+-activated non-selective channel TRPM4 and the lysosomal Ca2+ channel TRPM2 were also highlighted as essential for chemokine-dependent migration of activated DCs (Barbet et al, 2008; Guinamard et al, 2010; Knowles et al, 2013). However, whether and how Ca2+ intracellular stores regulate the homeostatic migration of immature DCs in the context of tissue patrolling has not been investigated so far.

Here, we analyzed the role of Ca2+ signaling in immature DC migration in confinement. We observed that speed-fluctuating DCs exhibited intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations that were associated with fast motility phases and did not rely on extracellular Ca2+ influx. IP3Rs were found to be required for maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ levels and fast locomotion of immature DCs. We further identified IP3R1 as a specific regulator of their speed fluctuations and migration persistence. IP3R1 maintains the intracellular gradient of myosin II in migrating DCs, allowing efficient space exploration. IP3R1 and ER Ca2+ stores therefore emerge as key regulators of sustained myosin II activity and polarity in amoeboid-like confined cell migration.

Results

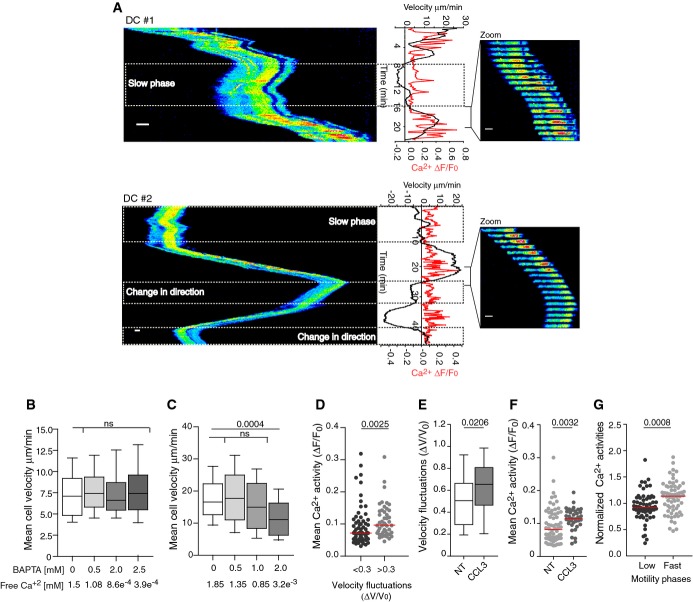

Ca2+ oscillations are predominantly observed in immature DCs that undergo significant speed fluctuations and changes of direction

We aimed at unraveling the role of Ca2+ signaling in migration of immature DCs evolving in a confined environment. To address this question, we monitored intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in mouse bone marrow-derived DCs migrating in fibronectin-coated 5 × 5 μm micro-fabricated channels. Although it is not clear to which DC subset these cells correspond to, they provide a unique model to analyze molecular mechanisms that can be addressed neither in vivo nor in tissue-isolated DCs. Beyond mimicking the confined space of tissues, micro-channels are compatible with high-resolution time-lapse microscopy and further impose to DCs an elongated well-defined shape that facilitates mechanistic studies (Supplementary Fig S1A) (Faure-Andre et al, 2008; Heuze et al, 2011). Analysis of cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics in immature DCs loaded with the Ca2+ dye Oregon Green BAPTA showed that intracellular Ca2+ spikes were observed in ∽70% of migrating cells although at variable frequencies (n = 45, examples on Fig1A and Supplementary Videos S1 and S2). Surprisingly, neither the percentage of cells displaying Ca2+ spikes nor spike frequency were significantly affected when adding extracellular BAPTA (71% ± 11 versus 55% ± 7, n = 67 and Supplementary Fig S1B), even though Ca2+ influx into DCs was abolished in the presence of this extracellular Ca2+ chelator (Supplementary Fig S1C). These data indicate that the intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations observed in migrating DCs do not result from extracellular Ca2+ influx but rather from Ca2+ released from intracellular stores. Accordingly, we found that chelation of extracellular Ca2+ did not impair immature DC migration in micro-channels, collagen-coated transwells, or collagen gels (Fig1B, Supplementary Fig S1D and E). Noticeably, the migration of T lymphocytes in micro-channels was strongly altered by addition of BAPTA into the milieu (Fig1C), indicating that the ability to move independently of extracellular Ca2+ does not apply to all leukocytes but might rather represent a peculiarity of DCs.

Figure 1.

- A Left, kymograph from sequential epifluorescence (20×) images showing cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in speed-fluctuating immature DC after slow motility phases (upper and lower panel) and a change in direction (lower panel). DCs were loaded with the Ca2+ dye Oregon Green BAPTA 1-AM, introduced in micro-channels, and imaged every 10 s. Right, sequential epifluorescence (20×) images (1 image/20 s is shown). Instantaneous velocities and intracellular calcium oscillations were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- B, C Mean cell velocity of immature DCs (n > 125 cells from two independent experiments) (B) or CD8+ T lymphocytes (n > 40 cells from one experiment) (C) migrating in micro-channels with or without BAPTA. Boxes illustrate 10–90 percentiles of values, and whiskers represent the range of values. P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test.

- D Mean intracellular calcium concentration in speed-fluctuating (ΔV/V0 > 0.3; ΔV/V0 relative speed variation divided by the global median velocity) and non-speed-fluctuating (ΔV/V0 < 0.3) immature DCs (n = 187 cells from more than three independent experiments). P-values were calculated using a Mann–Whitney test.

- E, F Velocity fluctuations (ΔV/V0) (E) or mean Ca2+ activities (F) displayed by DCs migrating in micro-channels in the presence of 100 ng/ml CCL3. P-values were calculated using a Mann–Whitney test, with respect to non-treated DCs (NT).

- G Mean Ca2+ activities during phases of fast (> 50% of max velocity) and slow (< 50% of max velocity) motility in speed-fluctuating DCs (Supplementary Fig S2F) (n = 64 cells, from three independent experiments). Activities were normalized to the mean Ca2+ activity shown by each cell during the entire movie. The P-value was calculated using a Mann–Whitney test.

To investigate whether these intracellular Ca2+ oscillations play a role in DC migration, we monitored the mean Ca2+ activity, that is, the area under the Ca2+ fluctuation curve (Ca2+ ΔF/F0 versus time, Fig1A), together with cell speed. We did not detect a strong correlation between the amount of released Ca2+ and the mean speed of DCs (Supplementary Fig S2A). However, significant mean Ca2+ activities (ΔF/F0 > 0.1) were almost exclusively detected in DCs migrating at fast speed (mean speed > 5 μm/min) (Supplementary Fig S2A). This was observed in both fibronectin and PEG-coated micro-channels (Supplementary Fig S2B), indicating that neither Ca2+ oscillations nor DC velocity require the engagement of integrins.

Noticeably, we found that among fast-migrating DCs, cells undergoing significant velocity fluctuations during locomotion (instantaneous speed variance > 30% of the mean speed, Supplementary Fig S2C) exhibited increased levels of cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig1D). Supporting this result, we observed that addition of the chemokine CCL3, known to act on immature DCs (Sallusto et al, 1998), significantly increased both their speed fluctuations (Fig1E and ΔV/V0 > 0.3 in 72% of control versus 85% of CCL3-treated DCs) and mean Ca2+ activity (Fig1F). However, CCL3 did not compromise the migration speed of DCs nor induce their maturation (Supplementary Fig S2D and E). Noticeably, in speed-fluctuating DCs, Ca2+ release was predominantly associated with fast motility phases as compared to slow motility ones (Fig1A (upper panel) and G, and Supplementary Fig S2F). This association was observed in DCs that maintained their direction after undergoing a slow motility phase (Fig1A upper panel) as well as in cells that changed direction upon slowing down (Fig1A lower panel, and Supplementary Fig S2G). Altogether, these findings indicate that (i) Ca2+ oscillations might be specifically required for fast-migrating DCs to tune their instantaneous speed during locomotion and (ii) sustained Ca2+ activity may be needed for speed-fluctuating DCs to accelerate after a slow motility or an arrest phase.

Release of ER Ca2+ stores through IP3 receptors is required to maintain intracellular Ca2+ levels and fast dendritic cell migration

Our data indicate that intracellular Ca2+ oscillations are predominantly observed during fast motility phases in speed-fluctuating DCs and that they result from Ca2+ release from intracellular stores rather than from extracellular Ca2+ influx. We therefore investigated the nature of the Ca2+ store(s) involved. As the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a major source of intracellular Ca2+, we analyzed the role of IP3Rs, which control the release of Ca2+ from the ER into the cytosol. Treatment of DCs with the IP3R inhibitor xestospongin C (XestC) significantly reduced their ability to migrate in collagen-coated transwells (Supplementary Fig S3A). Similarly, the instantaneous speed of DCs crawling in micro-channels was decreased upon XestC treatment (Supplementary Fig S3B). XestC did not induce DC maturation (Supplementary Fig S3C). These data strongly suggest that IP3Rs are required for immature DCs to migrate at fast speed.

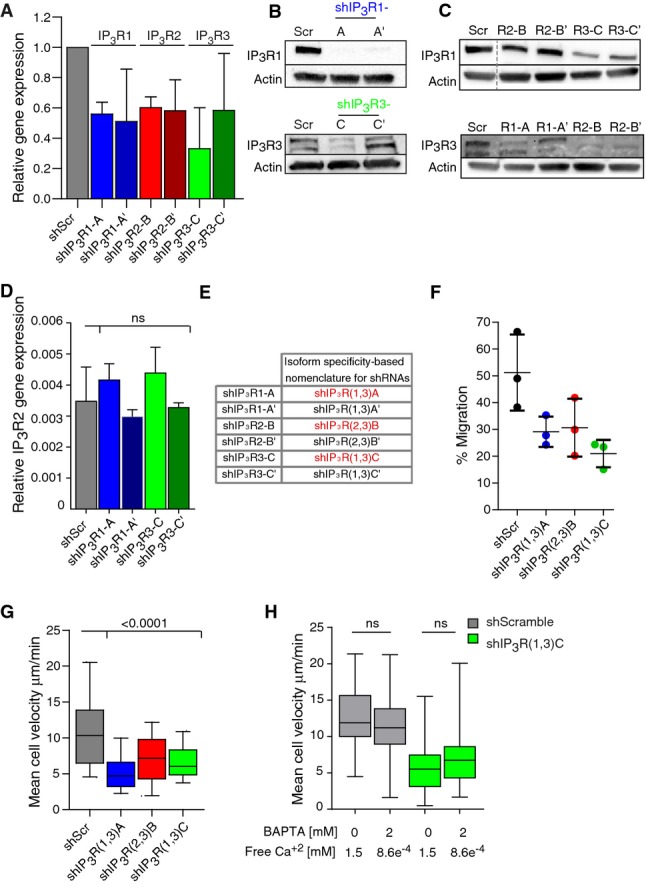

DCs express all three IP3R isoforms: 1, 2, and 3 (Stolk et al, 2006). To analyze their respective role in the migration of immature DCs, we silenced them individually using shRNA-encoded lentivirus. A significant reduction in IP3R mRNA intracellular levels was observed by quantitative PCR upon DC infection with two shRNA-containing lentiviral particles per isoform, showing that their expression can be reduced using such strategy (Fig2A). In the case of IP3R1 and IP3R3, for which specific antibodies are available, silencing was observed even more efficiently at the protein level (Fig2B). Immunoblot and quantitative PCR analysis showed that the two shRNAs directed against IP3R1 silenced both IP3R1 and IP3R3 isoforms, but not IP3R2 (Fig2C). The same result was obtained when using the shRNAs directed against IP3R3 (Fig2C). In contrast, the shRNAs directed against IP3R2 knocked down IP3R3 and IP3R2 but had only a minor effect on IP3R1 expression (Fig2D). We therefore renamed these shRNAs based on their silencing specificity as following: shRNA-IP3R1 = shIP3R(1,3)A, shRNA-IP3R2 = shIP3R(2,3)B, and shRNA-IP3R3 = shIP3R(1,3)C. The ones highlighted in red on Fig2E were used for the rest of our study.

Figure 2.

- Relative gene expression of IP3R1 (blue), IP3R2 (red), and IP3R3 (green) in IP3R-silenced DCs. DCs were infected with two lentiviruses encoding for different shRNAs for IP3R isoforms. ShScramble-infected DCs were used as a control. Gene expression was determined by a quantitative PCR. It was calculated with respect to GAPDH expression and normalized to the levels observed in the shScramble. The median plus standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown.

- Immunoblot for IP3R type 1 and IP3R type 3 in IP3R-silenced DCs. Actin was used as a control. IP3R3 appears as two bands as previously described (22).

- Immunoblot for IP3R type 1 (top) and IP3R type 3 (bottom) in DCs transduced with lentivirus encoding for different IP3R shRNAs. Actin was used as a control.

- Relative IP3R2 expression in ShScramble-infected DCs (gray), shIP3R1 (blue), and IP3R3 (green)-silenced DCs. The experiment was performed as described in (A).

- Table showing the nomenclature for shRNAs related to their isoform-specific silencing. The shRNAs chosen to pursuit this study are highlighted in red.

- Transmigration assay of shScramble-, IP3R(1,3)A (blue)-, IP3R(2,3)B (red)-, and IP3R(1,3)C (green)-expressing DCs. Cells were loaded in the upper chamber of a 5-μm pore collagen-coated transwell assay, recovered from the upper and lower chambers after 16 h, and counted. The median from three independent experiments is shown.

- Quantification of the mean cell velocity of shIP3R(1,3)A (blue)-, shIP3R(2,3)B (red)-, and shIP3R(1,3)C (green)-silenced immature DCs migrating in micro-channels. shScramble-infected DCs were used as a control (gray) (n > 100 cells from three independent experiments for shIP3R(1,3)A and shIP3R(1,3)C and two independent experiments for shIP3R(2,3)B). Boxes illustrate 10–90 percentiles of values, and whiskers represent the range of values. P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test.

- Quantification of the mean cell velocity of shIP3R(1,3)C (green)-silenced immature DCs migrating in micro-channels in the presence of 2 mM BAPTA. shScramble-infected DCs were used as a control (gray) (n > 70 cells from two independent experiments). P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test.

None of these shRNAs triggered the activation of immature DCs (Supplementary Fig S3D, upper panels). Flow cytometry analysis of IP3R-silenced DCs loaded with both Oregon Green BAPTA and FuraRed showed that they displayed strongly reduced intracellular Ca2+ levels as compared to control cells (Supplementary Fig S3D, lower panels). This result indicates that decreased expression of IP3Rs indeed dramatically reduced the concentration of intracellular Ca2+. Silencing of IP3R1, 2, or 3 in immature DCs compromised their migration in collagen-coated transwells and decreased their instantaneous velocity in micro-fabricated channels (Fig2F and G, Supplementary Fig S3E). Addition of BAPTA did not further decrease the speed of IP3R-silenced DCs, indicating that the residual migration of these cells is independent of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig2H). We conclude that inhibition or silencing of IP3Rs impairs the migration of immature DCs.

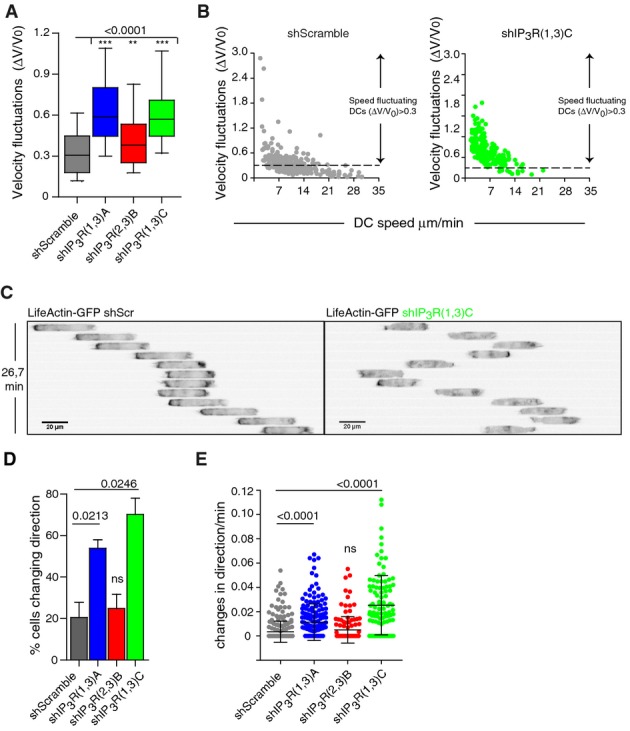

IP3 receptor 1 controls the migration persistence and space exploration capacity of immature DCs

We observed that shIP3R(1,3)A and shIP3R(1,3)C, which silenced both IP3R1 and IP3R3 but not IP3R2, strongly increased speed fluctuations in immature DCs migrating in micro-channels (Fig3A). In sharp contrast to control speed-fluctuating DCs that reached velocities below 5 μm/min, most speed-fluctuating shIP3R(1,3)-silenced DCs migrated at speeds below this value (Fig3B). This result, together with our data showing that intracellular Ca2+ released is mainly observed in DCs migrating at speed above 5 μm/min (Supplementary Fig S2A), supports the idea that in the absence of IP3R1 and/or 3, immature DCs cannot accelerate and therefore remain in phases of slow motility. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that the percentage of cells that changed direction during locomotion as well as the frequency of direction changes per cell were significantly enhanced in IP3R1- and IP3R3-silenced DCs (Fig3C–E). Similar results were obtained when generally inhibiting IP3R activity with XestC (Supplementary Fig S3F–H). Regrettably, the low intracellular Ca2+ levels of IP3R1- and IP3R3-silenced DCs did not allow us to analyze their Ca2+ dynamics while evolving in micro-channels (Supplementary Fig S3D, lower panels). Interestingly, no defect in DC persistence was observed when using shIP3R(2,3)B, which knocked down IP3R2 and IP3R3 but not IP3R1. Although IP3R2- and IP3R3-silenced DCs migrated at slower velocity (Fig2G), they did not change direction more often as compared to control cells (Fig3D and E). These findings suggest that IP3R1, but not IP3R2 and IP3R3, is specifically required for immature DCs to adopt a speed-fluctuating but persistent locomotion behavior. In the absence of this molecule, DCs cannot accelerate upon slow motility phases and therefore remain in a non-persistent slow migration mode characterized by frequent changes in direction.

Figure 3.

IP3R1 silencing favors frequent changes in direction in immature DCs migrating in micro-channels

- Velocity fluctuations (ΔV/V0) of immature DCs migrating in micro-channels. Boxes illustrate 10–90 percentiles of values, and whiskers represent the range of values. P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test.

- Dot plot showing velocity fluctuations and migration speeds of shScramble (gray)- and shIP3R(1,3)C (green)-expressing DCs.

- Inverted sequential epifluorescence images (20×) of a representative control DC (left) and an immature shIP3R(1,3)C-silenced DC (right) migrating in micro-channels. DCs were differentiated from LifeAct-GFP transgenic mice and imaged every 2.2 min.

- Percentage of DCs changing their direction of locomotion while migrating in micro-channels. P-values were calculated with a paired test with respect to the shScramble condition.

- Dot plot showing the frequency of changes in direction of immature DCs while migrating in micro-channels. Bars show the mean plus the standard deviation. A Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for statistical analysis.

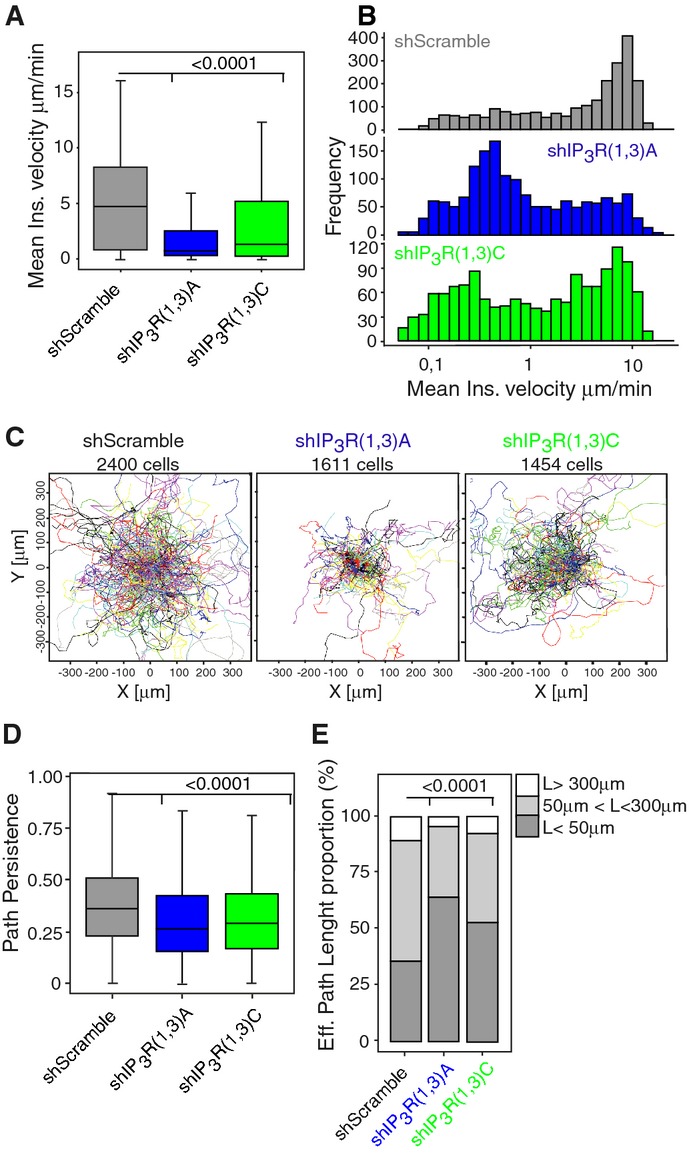

We therefore assessed the role of IP3R1 in the migration persistence of immature DCs. For this, the migration of shIP3R(1,3)A- and shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs was analyzed in a micro-fluidic device that confines the cells under a 5-μm-high ceiling but allows their free motion in 2D (Supplementary Fig S3I). As observed in micro-channels, both shRNAs decreased the migration speed of immature DCs in this confined 2D migration setup (Fig4A and B). Analysis of cell individual trajectories highlighted that shIP3R(1,3)A- and shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs exhibited constrained displacements rather than long trajectories (Fig4C). Accordingly, quantification of their “persistence path”, measured as the ratio between the effective length and the total length of the cell trajectory (Maiuri et al, 2012), showed that it was significantly decreased in these cells as compared to their control counterpart (Fig4D). Furthermore, calculation of the “effective displacement”, which corresponds to the distribution of 0- to 50-μm, 50- to 300-μm, and > 300-μm-long cell paths, indicated that shIP3R(1,3)A- and shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs displayed shorter paths during motion as compared to control cells (Fig4E). Equivalent results were obtained when monitoring the migration of DCs embedded in 3D collagen gels: both the migration speed and persistence were significantly decreased in IP3R1,3-silenced cells (Supplementary Fig S4A–C). Together, these data indicate that (i) IP3R1 controls the migration persistence of immature DCs and thus their ability to explore their surrounding space and (ii) this applies to 1D, 2D, and 3D environments. They further suggest that the velocity and persistence of DCs are two migration parameters that are differentially regulated and can be uncoupled by knocking down specific IP3R isoforms.

Figure 4.

IP3R1 controls the persistence of immature DCs migrating in a 2D-confined environment

- Graph showing the DC mean instantaneous speed. P-values were calculated with a t-test analysis.

- Mean instantaneous speed distribution of migrating DCs.

- Representation of individual DC trajectories.

- Path persistence (calculated as the ratio between the effective length and the total length of the cell trajectory) of migrating DCs. P-values were determined with a t-test analysis.

- Bars showing the proportion of the effective length displacement (L) of DCs. A Fisher's exact test (P-value < 2.2 × 10−16) was used for statistics.

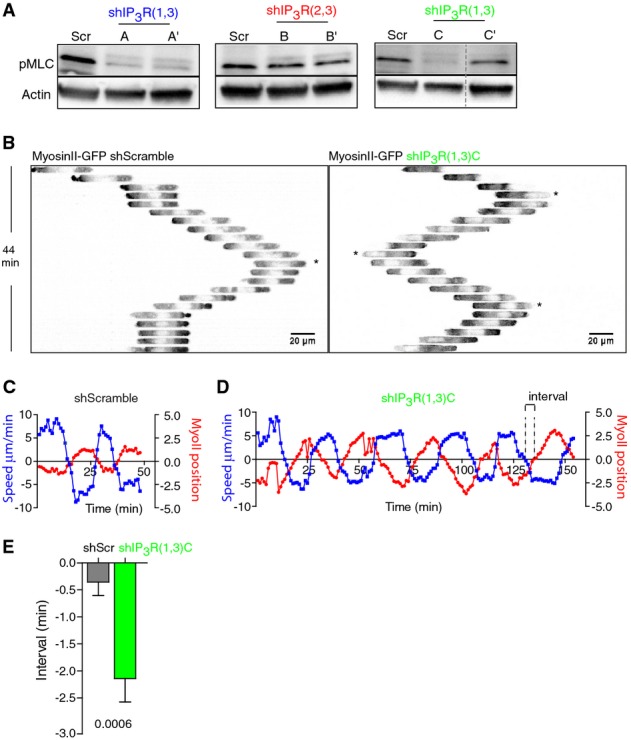

IP3 receptor 1 regulates the migration of immature DCs by controlling myosin II activity and dynamics

We next searched for the mechanism by which IP3R1 controls the migration persistence of immature DCs. Myosin II-mediated contractility is the main force-generating cellular component required for DC fast migration in confined environments (Faure-Andre et al, 2008; Lammermann et al, 2008). Furthermore, myosin IIA and IP3R1 were shown to physically interact in MDCK cells (Hours & Mery, 2010). We therefore investigated whether myosin II activity was altered in IP3R knockdown DCs by analyzing the phosphorylation levels of its regulatory light chain MLC. Indeed, it was shown that Ca2+ promotes the phosphorylation of MLC by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLCK, leading to motor activation and protrusion retraction in endothelial cells (Hours & Mery, 2010). MLC phosphorylation was significantly decreased in DCs transduced with the shRNAs that silenced IP3R1 and IP3R3 (including shIP3R(1,3)A′) (Fig5A). In contrast, no MLC phosphorylation reduction was observed in cells expressing the shRNAs that silenced IP3R2 and IP3R3 (including shIP3R(2,3)B′). This result is consistent with shIP3R(2,3)B not having any impact on DC velocity fluctuations and migration persistence. Of note, shIP3R(1,3)C′ did not significantly decrease the levels of phospho-MLC, in agreement with its low silencing efficiency (Fig2A and B). Hence, IP3R1 is required for myosin II activity in immature DCs migrating in confinement.

Figure 5.

- A Immunoblot showing the intracellular levels of phosphorylated MLC in DCs transduced with the shScramble or shRNAs for IP3Rs (shIP3R(1,3)A′, shIP3R(2,3)B′, and shIP3R(1,3)C′). Actin was used as a control.

- B Inverted sequential epifluorescence images (20×) showing myosin IIA-GFP localization of a representative shScramble (left)- and shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DC (right) migrating in micro-channels. Myosin IIA-GFP knock-in DCs were imaged every 1 min (1 out of 2 images is shown). Asterisks highlight changes of direction during locomotion.

- C,D Myosin IIA-GFP localization (red) versus velocity fluctuations (blue, ΔV/V0) in a representative shScramble-transduced DC (C) or shIP3R(1,3)C-silenced (D) migrating in micro-channels. DCs were recorded as in (B).

- E Quantification of the interval between curves (highlighted in D) obtained for myosin IIA positioning and velocity from shScramble- and shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs. Cells were recorded as in (B) (n = 20 cells from two experiments). The Mann–Whitney test was applied for statistical analysis.

To strengthen this finding, we investigated whether myosin IIA dynamics were altered in shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs. For this, immature DCs generated from myosin IIA-GFP knock-in mice (Zhang et al, 2012) (the main myosin II isoform in mouse DCs; Immunological Genome project http://www.immgen.org) were imaged while migrating in micro-channels (Fig5B and Supplementary Video S3). Myosin IIA was more abundant at the rear than at the front of migrating control DCs (Fig5B). Inversion of this myosin IIA gradient, that is, enrichment of myosin IIA at the cell front, was associated with changes in direction in these cells (Fig5B, star on left panel). Noticeably, myosin II dynamics were strongly altered in shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs, which changed direction even when the motor protein was mostly concentrated at the cell rear (Fig5B, stars on right panel and Supplementary Video S3). To quantify these observations, the total myosin IIA-GFP distribution was analyzed with respect to the geometrical center of the cell (Supplementary Fig S5A) and plotted in a graph together with the speed of DCs (Fig5C). As observed in Fig5B, this analysis showed that when control immature DCs were moving forward (positive speed value, blue line on Fig5C), myosin IIA was concentrated at their rear (negative value for myosin IIA distribution, red line in Fig5C). In contrast, when their speed decreased, for example, during a change of direction, myosin IIA was found to localize at both their cell rear and front. This phase of opposition between the speed of migration and myosin IIA front/back distribution indicates that changes of direction are likely to result from strong myosin IIA enrichment at the front of control immature DCs. Strikingly, this was not observed in shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing DCs, for which the myosin IIA distribution curve was significantly delayed with respect to the cell speed curve (Fig5D and E). We conclude that IP3R1 silencing alters myosin II activity and distribution so that cell directionality does not follow anymore the polarity gradient of the motor protein.

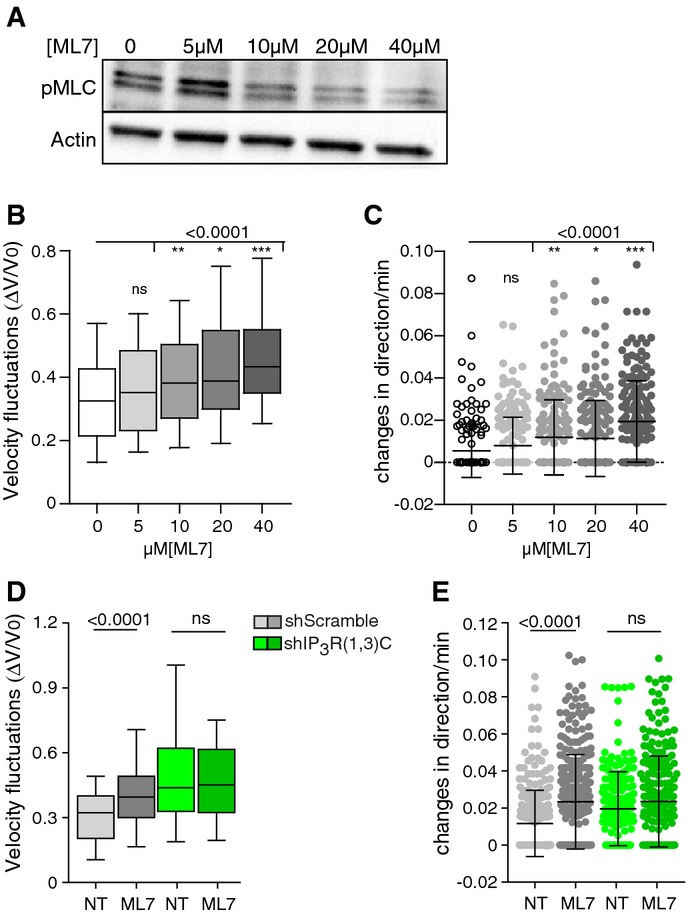

These data strongly suggest that IP3R1 regulates the motility of immature DCs at least in part by promoting myosin IIA activity. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed DC migration in the presence of increasing amounts of the MLCK inhibitor, ML7. We found that ML7 treatment decreased the intracellular levels of active MLC in immature DCs (Fig6A). More importantly, ML7 treatment reduced DC velocity and strongly increased their speed fluctuations and frequency of changes in direction (Fig6B and C, and Supplementary S5B). Thus, MLCK inhibition by ML7 mimics the migratory phenotype observed in IP3R1-silenced migrating DCs (Supplementary Fig S5C. ML7 had no effect on the migration persistence of shIP3R(1,3)C-expressing cells (Fig6D and E). From this result, we conclude that MLCK is most likely inactive in the absence of IP3R1,3 and does therefore not account for the residual migration observed in IP3R1,3-silenced DCs. Altogether, our data are consistent with a model where immature DCs use IP3R1 and ER Ca2+ stores to promote the activity of myosin II and thereby maintain cell polarity during locomotion.

Figure 6.

- A Immunoblot showing the intracellular levels of phosphorylated MLC in DCs treated overnight with increasing amounts of the MLCK inhibitor, ML7.

- B,C Analysis of immature DCs migrating in micro-channels in the presence of ML7 or DMSO as a control (n > 170 cells from two independent experiments). Velocity fluctuations (ΔV/V0) of immature DCs migrating in micro-channels (B). Whiskers show 10–90 percentiles plus the median. P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test. Frequency of changes (C) in direction of DCs migrating in micro-channels. Mean plus SD are shown. A Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for statistical analysis.

- D,E Analysis of shScramble (gray)- and shIP3R(1,3)C (green)-expressing DCs migrating in micro-channels in the presence of 20 μM ML7 (n > 70 cells per condition from 3 independent experiments). Velocity fluctuations (ΔV/V0) of immature DCs migrating in micro-channels (D). Boxes illustrate 10–90 percentiles of values, and whiskers represent the range of values. P-values were calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test. Frequency of changes (E) in direction observed in DCs migrating in micro-channels. Means plus SD are shown. A Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for statistical analysis.

Discussion

We here unraveled a new role for intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in the regulation of amoeboid-like cell migration in confinement. We found that periodic intracellular Ca2+ increments were associated with fast motility phases in immature DCs whose speed fluctuates during locomotion. We further identified the mechanism involved by showing that inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ release by silencing IP3R1 compromised the activity and intracellular distribution of myosin IIA, the main force-generating protein involved in fast DC migration in confinement. We propose that by maintaining an intracellular gradient of active myosin IIA, IP3R1 enables DCs to tune their speed without losing their migration persistence, thereby facilitating the exploration of their environment.

Surprisingly, we found that the Ca2+ spikes observed in speed-fluctuating DCs occurred independently of extracellular Ca2+, which was found to be dispensable for immature DC migration in micro-channels, collagen-coated transwells, and collagen gels. This unexpected result suggests that Ca2+ is being recycled from the cytoplasm or other intracellular stores to feed back the ER upon Ca2+ release. Our finding is in agreement with data showing that integrins, whose activity relies on extracellular Ca2+, are not needed for DC migration in 3D environments (Lammermann et al, 2008). It is further reminiscent of a previous report, indicating that human polymorphonuclear cells randomly move in the presence of the Ca2+ chelator EDTA when squeezed between two glass slides (Malawista & de Boisfleury Chevance, 1997). This peculiar migration mode might however not apply to mature DCs, which have been shown to require extracellular Ca2+ influx to crawl in response to chemokine gradients (Partida-Sanchez et al, 2004). We have observed that LPS-matured DCs display less velocity fluctuations as well as decreased Ca2+ activity (MB, PV, and AMLD, unpublished results). Whether the migration of mature DCs relies on different Ca2+ stores as compared to immature DCs is an interesting question that remains to be investigated.

We identified IP3Rs as required to maintain intracellular Ca2+ levels in immature DCs migrating in confined micro-channels. Consistent with our analysis showing an association between the raise of intracellular Ca2+ with an increased DC locomotion, silencing of IP3Rs was found to reduce their velocity, most likely by maintaining them in phases of slow motility. DCs were shown to express the three IP3R isoforms, however, their role in immature DC migration was unknown (Stolk et al, 2006). Our results show that both IP3R1,3- and IP3R2,3-silenced DCs display reduced speed of locomotion, suggesting that these channels regulate DC velocity in a non-redundant manner. However, residual migration was observed in IP3R1,3-silenced DCs, which might be calcium independent or involve other(s) calcium intracellular store(s). Among intracellular stores, mitochondria may be a good candidate given that these organelles were found to be polarized at the level of the uropod at the rear of amoeboid-like migrating cells (Campello et al, 2006), where they might promote myosin IIA contractility by locally releasing Ca2+. Lysosomes have also recently emerged as important Ca2+ intracellular stores (Shen et al, 2012) and, on another hand, have been involved in the migration of phagocytes by regulating the formation of podosomes (Cougoule et al, 2005). Whether lysosomes regulate cell migration by allowing the release of intracellular Ca2+ is an intriguing possibility that could now be addressed.

Interestingly, we observed that IP3R1,3-silenced DCs displayed increased velocity fluctuations and lost their migration persistence, that is, they were unable to travel over long distances for space exploration. In contrast, IP3R2,3-silenced DCs did not exhibit decreased persistent migration as compared to IP3R1,3-silenced DCs. In these cells, velocity fluctuations were slightly increased but most likely not enough to promote changes of migration. These results are consistent with IP3R1 specifically regulating the ability of immature DCs to tune their speed during motion and modify their direction of migration. However, because this conclusion is based on shRNAs that silenced IP3R1 as well as IP3R3, we cannot formally exclude that these molecules show some degree of redundancy, that is, migration persistence defects might be only observed in DCs silenced for both IP3R isoforms. Nonetheless, our data show that the speed and persistence of locomotion are two migration parameters that can be uncoupled in DCs. This finding is of particular interest in view of the results obtained in the first “world cell race”, which showed a strong correlation between the speed and persistence of movement in a variety of cell types (Maiuri et al, 2012). Our study therefore suggests that the coupling between the cell migration speed and persistence is regulated at least in part by intracellular Ca2+ dynamics.

IP3Rs work as hetero-tetramers and display different affinities for IP3 binding. However, whether IP3R isoforms differ in their Ca2+ release capacity has been a matter of debate (Patterson et al, 2004). Our results showing that IP3R1 is required to maintain the persistence of DC migration as well as myosin II polarization and activity suggest that they might display different effector functions. A possible explanation consists in proposing that IP3R1 is capable of triggering MLCK activity by releasing Ca2+ from the ER, whereas IP3R2 and IP3R3 are not, even though Ca2+ release is indeed reduced in IP3R2- and IP3R3-silenced cells. Accordingly, it was shown that IP3R1 associates with myosin IIA (Hours & Mery, 2010). IP3R1 might therefore control myosin IIA activity and polarized distribution in migrating DCs by interacting with the motor protein and allowing its activation through the local release of ER Ca2+ stores. Such mechanism might restrict Ca2+ release to specific cell areas, thereby allowing the precise spatial regulation of myosin II activation during DC locomotion. Of note, treatment of IP3R(1,3)-silenced DCs with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 did not further compromise their migration persistence, indicating that this kinase does not compensate the lack of MLCK activity in these cells (PS and AMLD, unpublished results).

A question raised by this study concerns the nature of the signal(s) that trigger(s) the Ca2+ fluctuations observed during DC fast and persistent migration. Mechanical stimulation due to DC confinement might trigger the intracellular production of IP3 and release of Ca2+ from the ER into the cytosol. Because DC migration ex vivo is strongly reduced in the absence of confinement (Heuze et al, 2013), it is difficult to address this question experimentally. Interestingly, myosin II itself has been involved in the generation of Ca2+ flickers by the stretch-activated channel TRPM7 during keratocyte chemotaxis, suggesting that mechanical forces exerted by this motor protein might be involved in intracellular Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs downstream of chemokine receptors (Wei et al, 2009). Importantly, TRPM7 was also shown to directly phosphorylate myosin IIA heavy chain and thereby regulate its association to actin filaments (Clark et al, 2008). It is tempting to speculate that activation of myosin II by confinement induces IP3Rs to release ER Ca2+, which in turn promotes the sustained activity of the motor protein to allow persistent DC migration through MLCK activation. Whether TRPM7 is also involved in the maintenance of myosin IIA polarized distribution and activity in migrating DCs is an opened question.

In conclusion, we here show that the release of Ca2+ stores from the ER through IP3R1 allows immature DCs to maintain their myosin II activity and front/back asymmetry during migration independently of extracellular Ca2+ influx. This mechanism might enable immature DCs to efficiently explore their environment using a persistent but intermittent mode of migration, thereby optimizing their chances to find rare target antigens. How Ca2+ and IP3 receptors regulate tissue patrolling by DCs in vivo shall now be addressed.

Materials and Methods

Mice and cells

Myosin IIA-GFP mice were provided by Zhang et al (2012). LifeAct-GFP mice were provided by M. Sixt (Riedl et al, 2010). Bone marrow dendritic cells were cultured during 10–12 days in medium supplemented with fetal calf serum and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-containing supernatant obtained from transfected J558 cells, as previously described (Faure-Andre et al, 2008). HEK293T cells were maintained in culture as recommended by the manufacturer (ATCC). For T lymphocyte purification and activation, mouse splenocytes were activated in the presence of 50 U recombinant interleukin-2 with 10 μl anti-CD3-/anti-CD28-coated beads every 5–8 million cells (Miltenyi T Cell Activation/Expansion kit, 130-093-627). After 5 days, CD8+ T lymphocytes were purified from mouse spleen using a CD8a+ T Cell Isolation kit II (Miltenyi, 130-095-236).

Antibodies and reagents

Micro-channels were coated with fibronectin (Sigma) or PLL(20)-g[3.5]-PEG(2) (SuSoS Chemical). For myosin light chain kinase inhibition, cells were incubated with different concentrations of ML7 from Calbiochem as indicated for 16 h. For Ca2+ experiments, Oregon Green BAPTA 1-AM, FuraRed, BAPTA (Invitrogen), and Thapsigargin from Calbiochem were used. For IP3R inhibition, 5 μM xestospongin C from Calbiochem was used. For dendritic cell maturation, we incubate the cells 24 h with 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma). For flow cytometry analysis, we used a homemade 24G2 anti-Fc Receptor antibodies, rabbit serum from Agro Bio as a control, and anti-CD11c (HL3 clone), anti-IAbb (AF6-120.1 clone), and anti-CD86 (GL1 clone). For immunoblot, we used anti-IP3R type 1 (Abcam ab5804), anti-IP3R type 3 (610313 BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-phospho-myosin light chain (Rockland 600-401-416), and anti-actin (Millipore). For lentivirus production, HEK cells were transfected using GeneJuice (Novagen).

Preparation of micro-channels and 2D-confined devices

Micro-channels were functionalized to facilitate the diffusion of dyes and drugs (Heuze et al, 2011) with a final section of 5 × 5 × 350 μm. They were incubated with 20 μg/ml fibronectin alone or, when indicated, with a mix of fibronectin 20 μg/ml and PLL-PEG 0.1 mg/ml at a ratio of 75/25 (vol/vol) for 1 h and washed with PBS. 2D-confined device consists of an Ø 18-mm round lamella functionalized with 5-μm-high PDMS pillars. The lamella is put over the cells plated in 12-well plates with pillars facing the cells plus a weight to squeeze them until 5 μm high. Acquisition was started after 5 h of squeezing. The lamella with micro-pillars was previously coated with 20 μg/ml fibronectin for 1 h and washed with PBS.

Analysis of intracellular Ca2+ levels by flow cytometry and of Ca2+ dynamics in migrating DCs

Free calcium concentrations were calculated using the WEBMAX Standard software (http://web.stanford.edu/∽cpatton/webmaxcS.htm). For flow cytometry analysis, dendritic cells were incubated in Ringer's solution 1% BSA (in mM: 140 NaCl, 4,8 KCl, 10 glucose, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 Na2HPO4, 1 KH2PO4) 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 with 5 μM Oregon Green BAPTA 1-AM plus 5 μM FuraRed-AM. Cells were then washed in Ringer's solution and resuspended in complete media for acquisition. A ratio between Oregon Green BAPTA 1-AM and FuraRed signals was used to determine intracellular Ca2+ levels. For Ca2+ dynamics studies during DC migration, DCs were incubated with 5 μM Oregon Green BAPTA I-AM in Ringer media for 30 min, then washed and loaded in micro-channels. 2 × 105 cells were loaded in micro-channels 1 h before imaging. Images were taken every 10 s during 1–2 h. Fluorescence microscopy was performed on a Nikon TiE video microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera (HQ2, Photometrics) using a 20× objective (NA 0.75). Image processing was performed with ImageJ software (Rasband WS. ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997—2012). Cells were segmented by automatic thresholding (Yen), fluorescence intensities, and spatial coordinates of each cell were measured using the Analyze Particle plugin. Mean Oregon Green BAPTA 1-AM signals from cells were corrected to obtain ΔF/F0 (ΔF = F−F0, F0 is the minimum signal recorded for the previous 30 frames). Velocities of cells were then estimated according to spatial coordinates. Velocity fluctuations were calculated and Ca2+ signal (ΔF/F0) maxima were detected. For each cell, mean Ca2+ signals were computed during slow (< 50% of max velocity) or fast motility phases (> 50% of max velocity). For spike frequency analysis, only calcium activities over 30% of ΔF/F0 were considered.

Velocity, changes in direction, and 2D-tracking

Cell migration analysis in micro-channels and 2D confinement was performed as described previously (Faure-Andre et al, 2008; Maiuri et al, 2012). For velocity quantification and path tracking in micro-channels, cells were loaded in micro-channels and imaged during 20 h every 1–2 min on an epifluorescence video microscope Nikon TiE microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera (HQ2, Photometrics) using a 10× objective. Kymograph extraction and instantaneous velocity analyses were performed using a homemade program as described previously (Faure-Andre et al, 2008). For velocity quantification and tracking in 2D confinement, cell nuclei were stained with 200 ng/ml of Hoechst for 15 min at 37°C and cells were imaged every 2 min using a Zeiss AxioObserver microscope equipped with a 10× objective. Trajectories were determined following the fluorescent signal of the nuclei. The mean cell instantaneous speed is the mean of all instantaneous speeds of a cell. The effective length of a trajectory corresponds to the diameter of a disk that contains all the time points of the track. The cell path persistence is defined as the ratio between the effective and the total path length. Accordingly, if a cell is persistent, this value is close to one and, to the opposite, it is close to zero for a non-persistent cell.

Migration in collagen gels

DCs were mixed at 4°C with 1.6% bovine collagen type I at basic pH. Forty microliters of the mix were deposited at the center of a 35-mm glass-bottom dish, covered with a 12-mm glass slide, and incubated at 37°C during 20 min to allow fast collagen polymerization. Cells were imaged during 16 h on a video microscope (phase contrast) at a frequency of 1 image every 2 min (10× objective). To extract cell tracks, the mean image of the complete movie was subtracted to every time point, generating white objects (cells) on a dark background. Movies were processed using the FIJI plugin Filter Mean (Intensity 3) and cells tracked using a custom-made software (Maiuri et al, 2012).

Myosin IIA-GFP imaging and localization

For myosin II live imaging, we used DCs generated from myosin IIA HC-GFP knock-in mice and infected or not with shRNA encoded in lentiviruses. Cells were loaded in micro-channels, and myosin II HC-GFP DCs were imaged at low resolution with an epifluorescence video microscope Nikon TiE equipped with a cooled CCD camera (HQ2, Photometrics) with a 20× (NA 0.75) objective. For each cell, myosin IIA-GFP localization was measured as a vector representing the total fluorescent intensity regarding the geometrical center of the cell. The cell velocity was calculated based on the position of the geometrical center of the cell.

Lentivirus infection

For protein silencing, purified pLKO.1 lentiviral plasmids carrying shRNA sequences for IP3R1, IP3R2, and IP3R3 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. For shIP3R1, shRNAs #1 = TRCN0000012438, #2 = TRCN0000012439, #3 = TRCN0000012440, #4 = TRCN0000012441, and #5 = TRCN0000012442 were used. For IP3R2, shRNAs #1 = TRCN0000097136, #2 = TRCN0000277497, #3 = TRCN0000277566, #4 = TRCN0000277567, and #5 = TRCN0000097135 were used. For IP3R3, shRNAs #1 = TRCN0000012443, #2 = TRCN0000012444, #3 = TRCN0000012445, #4 = TRCN0000012446, and #5 = TRCN0000012447 were used. As control, we used an shRNA containing a scramble sequence against GFP (Cebrian et al, 2011).

To generate lentiviral particles, plasmids encoding lentivirus-expressing shRNAs were purified with the NucleoSpin Plasmid DNA Purification kit (Macherey-Nagel). HEK293T packaging cells were co-transfected with the transfer plasmid (pLKO/ShRNA), the pPAX2 packaging plasmid, and the pMD2G envelope plasmid (kind gifts from D. Trono, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland), using the GeneJuice Transfection Reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Novagen). Virus supernatants were tittered using the QuickTiter p24 associated Lentivirus Titer kit (Cell Biolabs Inc) and used to infect day 3 DCs at a multiplicity of 0.03 pg of p24/cell by adding it directly to the culture. The medium was replaced at day 4, and infected cells were selected with 4 μg/ml puromycin from day 5 to day 7. Several washes were done during the selection process to eliminate dead cells. Infected DCs were used from day 10 to 12 for experiments.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed for 30 min at 4°C in a buffer containing 100 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 5% glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM glycerophosphate. 30–50 μg of soluble extracts was loaded onto a 4–20% TGX gradient gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto a Trans-Blot Turbo PVDF/Nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk for 30 min, incubated with the appropriate antibodies, and revealed with SuperSignal West Dura substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Quantitative PCR

RNA extraction was done using RNA NucleSpin kit from Macherey-Nagel, and cDNA was produced from 1 μg of RNA using the SuperScriptVILO cDNA Synthesis kit from Life Technologies. Quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay from Applied Biosystems. The following primers were used to analyze gene expression: Mm00439907_m1 (itpr1), Mm00444937_m1 (itpr2), Mm01306070_m1 (itpr3), and Mm99999915_g1 (gapdh) as a control.

Transmigration assays

Tissue culture-treated 96-well permeable supports (Corning 3385) were used for transmigration studies. Transwells with a 3-μm pore size membrane were coated 12 h with 5 μg/ml collagen-I and washed with PBS. 0.1 × 106 cells per well were used to perform experiments and were allowed to transmigrate during 16 h at 37°C 5% CO2. Cells from both chambers were detached using worm PBS 5 mM EDTA and counted by flow cytometry using 10-μm beads (BioValley). The percentage of migration was determined as: %Migration = (Number of cells low chamber × 100)/(total counted cells). Propidium iodide was used to remove dead cells from the analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank R. Adelstein for providing myosin IIA-GFP knock-in mice. The authors acknowledge the PICT IBiSA platform at Institut Curie (CNRS UMR144), especially V. Fraisier, the Institut Curie animal facility, D. Lankar and O. Malbec for their global support, F. Sepulveda for providing T lymphocytes, and F.X. Gobert and I. Cebrian for their help with lentiviral production. F.L. was supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship EMBO ALTF 1163-2010 and P.V. by a Foundation pour la recherche médicale fellowship. This work was funded by grants from: the Young Investigator Program from the City of Paris, the European Research Council (Strapacemi 243103), and the Institut National pour la Recherche contre le Cancer to A-M.L-D. (INCA-2012-1-PLBio-02), the Association Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-09-PIRI-0027-PCVI) and the InnaBiosanté Foundation (Micemico) to A-M.L-D. and M.P. and the ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL*, “ANR-11-LABX-0043”.

Author contributions

PS initiated the project on the role of IP3R calcium in DC migration, designed, performed, analyzed, interpreted experiments, and participated to manuscript writing. A-ML-D directed the experimental work and wrote the manuscript. MM developed the softwares, analyzed all calcium dynamics in migrating DCs, and participated to data discussion. MLH did the CCL3, PEG calcium analysis experiments, helped design shRNA silencing experiments, and participated to data interpretation. MB did some calcium measurement experiments, helped MM with their analysis, and calculated calcium concentrations in culture media. FL helped PS with cell migration experiments in the 2D confiner and cell tracking analysis. PM wrote the softwares required to segment and analyze cell trajectories in 2D and 3D. ET helped with micro-fabrication. M-IT participated to data discussion and financially supported PS during the revision process. PL helped setting up calcium measurement experiments and participated to data discussion. MP designed migration experiments, data interpretation, and analysis together with A-ML-D. PV initiated the project on the role of calcium in DC migration, performed calcium recording experiments in 2D, analyzed the role of calcium chelation in DC and T-cell migration, performed the migration assays in 3D collagen gels, and participated to data discussion.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figure S4

Supplementary Figure S5

Supplementary Video S1

Supplementary Video S2

Supplementary Video S3

Supplementary Video Legends

Review Process File

References

- Barbet G, Demion M, Moura IC, Serafini N, Leger T, Vrtovsnik F, Monteiro RC, Guinamard R, Kinet JP, Launay P. The calcium-activated nonselective cation channel TRPM4 is essential for the migration but not the maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1148–1156. doi: 10.1038/ni.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage RA, Fogarty KE, Tuft RA, Fay FS. Calcium gradients underlying polarization and chemotaxis of eosinophils. Science. 1991;254:703–706. doi: 10.1126/science.1948048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campello S, Lacalle RA, Bettella M, Manes S, Scorrano L, Viola A. Orchestration of lymphocyte chemotaxis by mitochondrial dynamics. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2879–2886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebrian I, Visentin G, Blanchard N, Jouve M, Bobard A, Moita C, Enninga J, Moita LF, Amigorena S, Savina A. Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2011;147:1355–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Middelbeek J, Lasonder E, Dulyaninova NG, Morrice NA, Ryazanov AG, Bresnick AR, Figdor CG, van Leeuwen FN. TRPM7 regulates myosin IIA filament stability and protein localization by heavy chain phosphorylation. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:790–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougoule C, Carreno S, Castandet J, Labrousse A, Astarie-Dequeker C, Poincloux R, Le Cabec V, Maridonneau-Parini I. Activation of the lysosome-associated p61Hck isoform triggers the biogenesis of podosomes. Traffic. 2005;6:682–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure-Andre G, Vargas P, Yuseff MI, Heuze M, Diaz J, Lankar D, Steri V, Manry J, Hugues S, Vascotto F, Boulanger J, Raposo G, Bono MR, Rosemblatt M, Piel M, Lennon-Dumenil AM. Regulation of dendritic cell migration by CD74, the MHC class II-associated invariant chain. Science. 2008;322:1705–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1159894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinamard R, Demion M, Launay P. Physiological roles of the TRPM4 channel extracted from background currents. Physiology. 2010;25:155–164. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuze ML, Collin O, Terriac E, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Piel M. Cell migration in confinement: a micro-channel-based assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;769:415–434. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-207-6_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuze ML, Vargas P, Chabaud M, Le Berre M, Liu YJ, Collin O, Solanes P, Voituriez R, Piel M, Lennon-Dumenil AM. Migration of dendritic cells: physical principles, molecular mechanisms, and functional implications. Immunol Rev. 2013;256:240–254. doi: 10.1111/imr.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hours MC, Mery L. The N-terminal domain of the type 1 Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor stably expressed in MDCK cells interacts with myosin IIA and alters epithelial cell morphology. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1449–1459. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles H, Li Y, Perraud AL. The TRPM2 ion channel, an oxidative stress and metabolic sensor regulating innate immunity and inflammation. Immunol Res. 2013;55:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T, Bader BL, Monkley SJ, Worbs T, Wedlich-Soldner R, Hirsch K, Keller M, Forster R, Critchley DR, Fassler R, Sixt M. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Ishihara A, Oxford G, Johnson B, Jacobson K. Regulation of cell movement is mediated by stretch-activated calcium channels. Nature. 1999;400:382–386. doi: 10.1038/22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC. Physiological functions of cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP as calcium messengers. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:317–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H, Fallet M, de Bovis B, Meresse S, Gorvel JP. Peyer's patch dendritic cells sample antigens by extending dendrites through M cell-specific transcellular pores. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:592–601. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.039. e593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri P, Terriac E, Paul-Gilloteaux P, Vignaud T, McNally K, Onuffer J, Thorn K, Nguyen PA, Georgoulia N, Soong D, Jayo A, Beil N, Beneke J, Lim JC, Sim CP, Chu YS, participants WCR, Jimenez-Dalmaroni A, Joanny JF, Thiery JP, et al. The first world cell race. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R673–R675. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista SE, de Boisfleury Chevance A. Random locomotion and chemotaxis of human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) in the presence of EDTA: PMN in close quarters require neither leukocyte integrins nor external divalent cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng LG, Hsu A, Mandell MA, Roediger B, Hoeller C, Mrass P, Iparraguirre A, Cavanagh LL, Triccas JA, Beverley SM, Scott P, Weninger W. Migratory dermal dendritic cells act as rapid sensors of protozoan parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000222. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partida-Sanchez S, Goodrich S, Kusser K, Oppenheimer N, Randall TD, Lund FE. Regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by the ADP-ribosyl cyclase CD38: impact on the development of humoral immunity. Immunity. 2004;20:279–291. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RL, Boehning D, Snyder SH. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors as signal integrators. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:437–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.071403.161303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkawitz J, Schumann K, Weber M, Lammermann T, Pflicke H, Piel M, Polleux J, Spatz JP, Sixt M. Adaptive force transmission in amoeboid cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1438–1443. doi: 10.1038/ncb1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Flynn KC, Raducanu A, Gartner F, Beck G, Bosl M, Bradke F, Massberg S, Aszodi A, Sixt M, Wedlich-Soldner R. Lifeact mice for studying F-actin dynamics. Nat Methods. 2010;7:168–169. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0310-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760::AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D, Wang X, Li X, Zhang X, Yao Z, Dibble S, Dong XP, Yu T, Lieberman AP, Showalter HD, Xu H. Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat Commun. 2012;3:731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk M, Leon-Ponte M, Merrill M, Ahern GP, O'Connell P. IP3Rs are sufficient for dendritic cell Ca2+ signaling in the absence of RyR1. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:651–658. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal O, Lim HY, Gurevich I, Milo I, Shipony Z, Ng LG, Angeli V, Shakhar G. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2141–2153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FC, Meyer T. Ca2+ pulses control local cycles of lamellipodia retraction and adhesion along the front of migrating cells. Curr Biol. 2012;22:837–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Wang X, Chen M, Ouyang K, Song LS, Cheng H. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature. 2009;457:901–905. doi: 10.1038/nature07577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Wang X, Zheng M, Cheng H. Calcium gradients underlying cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Conti MA, Malide D, Dong F, Wang A, Shmist YA, Liu C, Zerfas P, Daniels MP, Chan CC, Kozin E, Kachar B, Kelley MJ, Kopp JB, Adelstein RS. Mouse models of MYH9-related disease: mutations in nonmuscle myosin II-A. Blood. 2012;119:238–250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figure S4

Supplementary Figure S5

Supplementary Video S1

Supplementary Video S2

Supplementary Video S3

Supplementary Video Legends

Review Process File