Abstract

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is a chronic lung disease of preterm infants characterized by arrested microvascularization and alveolarization. Studies show the importance of proangiogenic factors for alveolarization, but the importance of antiangiogenic factors is unknown. We proposed that hyperoxia increases the potent angiostatin, pigment epithelium–derived factor (PEDF), in neonatal lungs, inhibiting alveolarization and microvascularization. Wild-type (WT) and PEDF−/− mice were exposed to room air (RA) or 0.9 fraction of inspired oxygen from Postnatal Day 5 to 13. PEDF protein was increased in hyperoxic lungs compared with RA-exposed lungs (P < 0.05). In situ hybridization and immunofluorescence identified PEDF production primarily in alveolar epithelium. Hyperoxia reduced alveolarization in WT mice (P < 0.05) but not in PEDF−/− mice. WT hyperoxic mice had fewer platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-positive cells per alveolus (1.4 ± 0.4) than RA-exposed mice (4.3 ± 0.3; P < 0.05); this reduction was absent in hyperoxic PEDF−/− mice. The interactive regulation of lung microvascularization by vascular endothelial growth factor and PEDF was studied in vitro using MFLM-91U cells, a fetal mouse lung endothelial cell line. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulation of proliferation, migration, and capillary tube formation was inhibited by PEDF. MFLM-91U cells exposed to conditioned medium (CM) from E17 fetal mouse lung type II (T2) cells cultured in 0.9 fraction of inspired oxygen formed fewer capillary tubes than CM from T2 cells cultured in RA (hyperoxia CM, 51 ± 10% of RA CM, P < 0.05), an effect abolished by PEDF antibody. We conclude that PEDF mediates reduced vasculogenesis and alveolarization in neonatal hyperoxia. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia likely results from an altered balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors.

Keywords: angiogenesis, pigment epithelium–derived factor, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, vascular endothelial growth factor

Clinical Relevance

This study details the importance of angiostatic factors, specifically pigment epithelium–derived factor, in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Identification of a primary role of angiostatic factors in the pathogenesis of BPD is an important mechanistic concept that has previously received minimal attention. This work should impact basic and translational studies aimed at developing preventive therapy against the development and progression of BPD.

Studies have emphasized abnormalities of alveolarization and the pulmonary microvasculature in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (1, 2) or in animal models of BPD (3–5). This information is partially derived from knowledge that infants dying with BPD have arrested alveolarization and reduced alveolar microvessels, consistent with disrupted alveolar development. Recent work shows a relationship between interrupted alveolarization in BPD and impaired expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors, leading to the conclusion that the mechanisms of development of BPD involves loss of proangiogenic signaling (1, 6, 7).

Although intensely studied in microvascular injury in several organs, the role of angiostatins in the impairment of alveolarization and microvascular development in neonatal lung injury has received very little attention. Recently, increased levels of the angiostatic molecule, endostatin, were found in the tracheal aspirates and in the lung tissue of preterm infants who developed BPD, but a direct mechanistic relationship with the development of BPD was not explored (8). We proposed that impaired development of the alveolar unit (defined as the alveolar structure, including the underlying microvascular bed) in neonatal lung oxygen injury is mediated by an altered balance of pro- and antiangiogenic signaling.

Pigment epithelium–derived factor (PEDF) is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis (9–11). PEDF inhibits VEGF-induced vascular permeability and angiogenesis in diabetic retinopathy, in which PEDF and VEGF have reciprocal relationships in the control of microvascular remodeling (12, 13). Because of its role in regulating angiogenesis, we hypothesized that, during hyperoxia, PEDF is overexpressed in the developing lung, causing impaired alveolarization and microvascularization.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Reagents and their sources are described in the online supplement.

Methods

Neonatal CD1 mice and neonatal offspring of PEDF+/− breedings (C57Bl/6J background) were used. The sources of these strains and the breeding strategy for PEDF mice are given in the online supplement. PEDF+/− and PEDF−/− animals appear healthy, with normal growth. They have no reported gross congenital anomalies (14, 15) (see also the online supplement). Animals were housed and cared for by the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at Tufts Medical Center (see the online supplement). The animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hyperoxia Exposure of Neonatal Mice

Pups (Postnatal Day 5 [P5]) were exposed to room air (RA) or hyperoxia for 8 days (P13), as described in detail in the online supplement (16). On P13, pups were killed and the lungs harvested for study (see the online supplement).

Western Blot Analysis of PEDF and VEGF

Western blots for PEDF and VEGF were performed using lung homogenates from RA- and hyperoxia-exposed P13 mice (see the online supplement).

PEDF Localization by In Situ Hybridization

Cell-specific PEDF messenger RNA (mRNA) expression was determined by in situ hybridization in 5-μm lung sections from paraffin-embedded lungs of P13 mice after RA or hyperoxia exposure (see the online supplement).

Lung Morphometry

Lungs from RA- and hyperoxia-exposed wild-type (WT), PEDF−/−, and PEDF+/− mouse pups were used for morphometry studies. The lungs were inflation fixed at 20 cm water pressure (17) and the number of alveolar units and the mean linear intercepts (MLIs) measured (see the online supplement) (18).

Cell Cultures

Endothelial cell studies used the fetal mouse lung–derived MLFM-91U cell line (see the online supplement). Primary cultures of E17 T2 cells were prepared (see the online supplement).

Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Angiogenesis

The effects of PEDF and VEGF on MFLM-91U cell proliferation (assayed by cell counts and by [3H] thymidine incorporation) (19), cell migration (20, 21), and angiogenesis were determined. Angiogenesis was also measured in response to conditioned medium (CM) from fetal T2 cells (see the online supplement).

Immunofluorescence

Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) immunofluorescence was performed to identify endothelial cell numbers in the microvascular regions. β-galactosidase (β-Gal) immunofluorescence was performed to identify the cells expressing the PEDF transgene (see the online supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Results were evaluated by t test for comparison of two conditions, or ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Instat; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

PEDF Protein in Neonatal Mouse Lungs

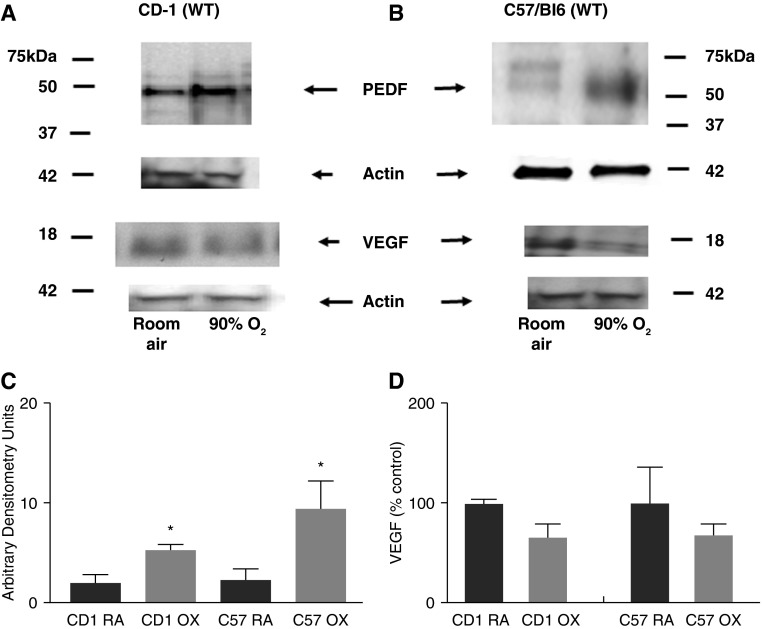

PEDF protein levels were determined in lungs from RA- and hyperoxia-exposed WT mice of two mouse strains: CD1 background, and C57Bl/6J (C57) background (WT littermates from PEDF+/− matings). RA PEDF levels were similar in the two strains (CD1:C57 = 1:1.1). PEDF in oxygen-exposed pups (both CD1 and C57) was significantly increased by approximately three- to fourfold (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

Effect of hyperoxia on pigment epithelium–derived factor (PEDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression in wild-type (WT) neonatal CD1 and C57Bl/6J (C57) mouse lungs. Representative Western blots of PEDF and VEGF in the lungs from Postnatal Day 13 (P13) CD1 mice exposed to room air (RA) or 90% oxygen (OX) for 8 days (A) and from the lungs from C57Bl/6J mice exposed to RA or 90% oxygen for 8 days (B). (C) Mean ± SEM of densitometry of PEDF in CD1 mice (*P < 0.03; n = 3) and C57Bl/6J mice (*P < 0.02; n ≥ 6) after exposure to RA or hyperoxia, using actin as an internal control. (D) Mean ± SEM of densitometry of VEGF in CD1 and in C57Bl/6J mice exposed to RA or hyperoxia using actin as an internal control (n ≥ 3).

Previous reports document decreased VEGF with hyperoxia (22). VEFG protein levels were decreased by 35% in our hyperoxia-exposed CD1 and C57 lungs (Figure 1D). These results show that the dramatic increase in PEDF after hyperoxia treatment was accompanied by decreased VEGF, albeit not as dramatic. These data indicate an altered balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors in this BPD model.

Cellular Localization of PEDF Expression

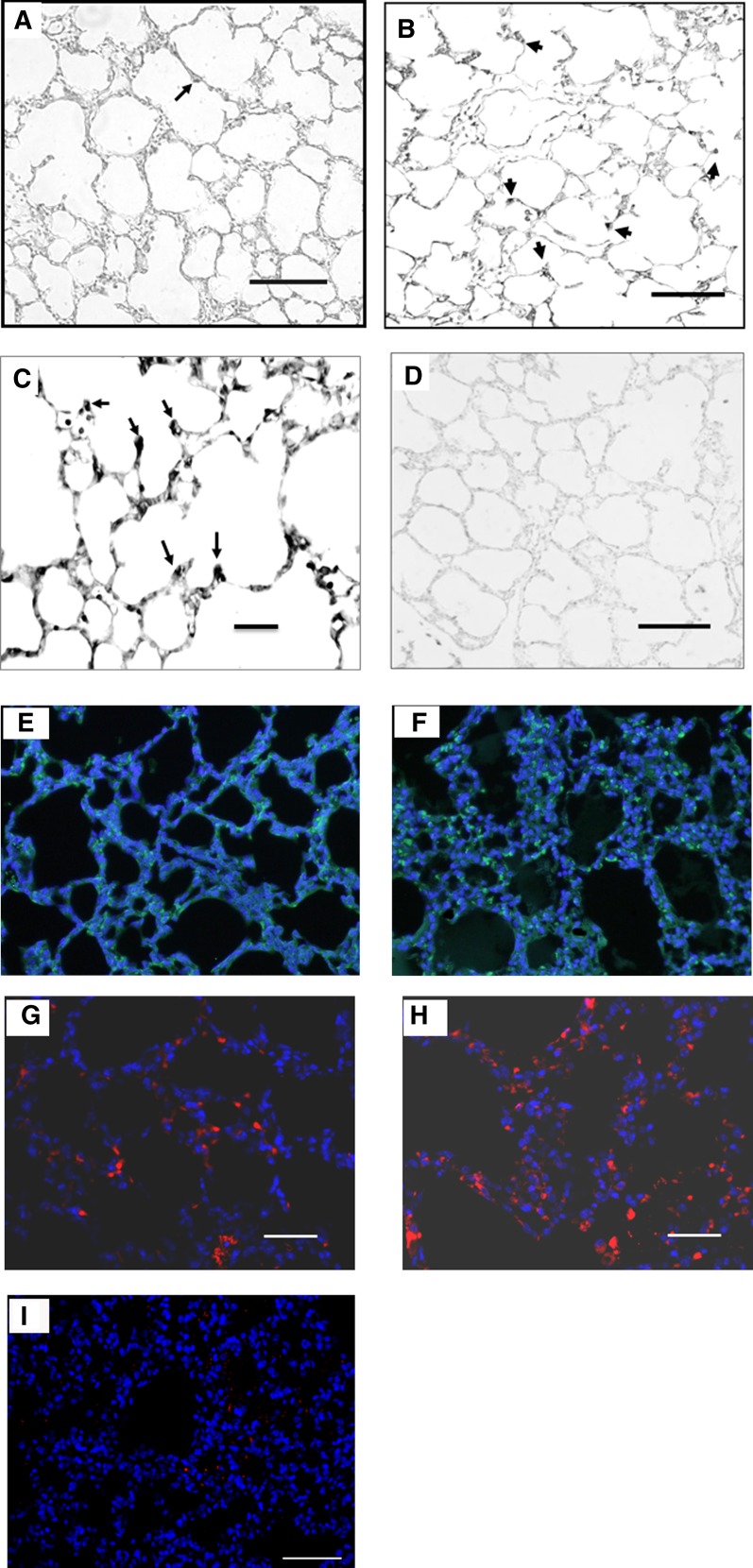

We used in situ hybridization to identify the murine pulmonary cells expressing PEDF mRNA (23). RA lungs showed low-intensity labeling of some alveolar epithelial cells. Hyperoxia-exposed lungs had increased intensity of labeling compared with RA. The enhanced PEDF mRNA expression was seen in the alveolar septal tips and in rounded alveolar epithelial cells, suggestive of T2 cells. It is interesting to note the strong PEDF mRNA expression in the blunted or shortened septal tips of hyperoxic lungs, whereas PEDF expression was not apparent in septal tips of RA-exposed lungs. No mesenchymal expression of PEDF mRNA was apparent (Figures 2A–2C; Figure 2D shows sense control). We next used immunofluorescence for β-Gal to identify PEDF-expressing cells. β-Gal staining was primarily noted in alveolar epithelial cells, and appeared increased in hyperoxic lungs (Figures 2E and 2F). Finally, we used PEDF immunofluorescence in WT lungs (Figures 2G and 2H). PEDF protein was present in alveolar epithelia in both RA and hyperoxia lungs. PEDF was present in relatively few cells in RA lungs. With oxygen exposure, cells expressing PEDF appeared increased. Positive staining was not detected when the primary antibody for PEDF (Figure 2I) or β-Gal (data not shown) was omitted.

Figure 2.

Expression of PEDF messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein in RA- and hyperoxia-exposed WT mouse lungs. In situ hybridization for PEDF mRNA was performed in 5-μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded lungs from mice exposed to either RA or 90% oxygen from P5 through P13. PEDF mRNA was localized using digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense probes. (A) RA: low intensity of PEDF expression is seen in some alveolar epithelial cells. (B) Hyperoxia: increased expression of PEDF (arrows) is seen in alveolar epithelial cells and in blunted alveolar septal tips). (C) Higher magnification of the hyperoxia condition; arrows point to PEDF-expressing cells. (D) RA: sense probe showing minimal background. Scale bars represent 100 μM (A, B, and D) or 50 μM (C). (E and F) β-galactosidase (β-Gal) immunofluorescence staining (green) from P13 mouse PEDF+/− lungs after exposure to RA (E) or hyperoxia (F). Blue 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain shows cell nuclei. β-Gal–positive cells were primarily found in alveoli and were more prominent in hyperoxia-exposed lungs compared with RA-exposed lungs. Scale bars represent 50 μM. (G–I) Representative figures of PEDF immunofluorescence staining (red) from P13 mouse WT lungs after exposure to RA (G) or hyperoxia (H). PEDF-positive cells were more prominent in WT hyperoxia-exposed compared with RA-exposed lungs. (I) A representative control in which the PEDF primary antibody was omitted. Blue DAPI stain shows cell nuclei. Scale bars represent 50 μM.

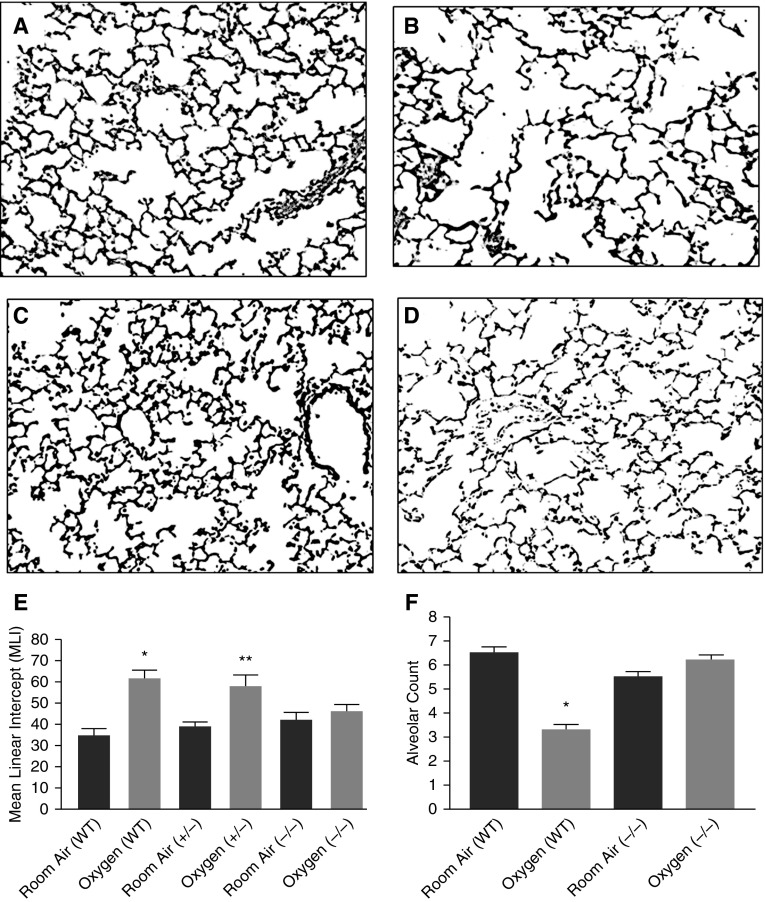

PEDF Expression in Hyperoxia Causes Impaired Alveolarization

Morphometry studies were done in the lungs from P13 offspring of PEDF heterozygote matings that produced WT (+/+), heterozygote (+/−), and homozygote (−/−) littermates. These littermates were exposed to RA or hyperoxia. Alveolar simplification with larger and fewer air spaces was apparent in oxygen-exposed WT lungs compared with RA-exposed WT lungs (Figures 3A and 3B) (23). Hyperoxia-induced alveolar simplification was significantly attenuated in PEDF−/− mice (Figures 3C and 3D). Measurements of the MLI, which is inversely proportional to alveolar surface area, confirmed the observed changes in alveolar structure. In WT mice, the MLI was 61.6 (± 3.7) after hyperoxia compared with 34.6 (± 3) after RA (mean [±SEM]; P < 0.05). The MLI in PEDF−/− mice remained unchanged by hyperoxia, and was not significantly different from that of RA-exposed WT mice (42 ± 3.6 in RA and 46 ± 3 in hyperoxia PEDF−/− mice; mean ± SEM; P < 0.05 compared with WT hyperoxia; Figures 3E). Radial alveolar counts were done to confirm alveolar simplification. Hyperoxia-exposed WT mice had lower alveolar counts compared with RA-exposed mice (P = 0.0001). The decrease after hyperoxia was not seen in PEDF−/− mouse lungs (Figures 3F). Thus, the alveolar surface area and numbers were unaffected by hyperoxia in the absence of PEDF.

Figure 3.

PEDF knockout (KO) prevents loss of alveolarization with hyperoxia. (A–D) Representative photomicrographs of lungs from RA- and hyperoxia-exposed P13 WT and PEDF−/− mice. Scale bars represent 100 μM. (E) Mean linear intercept (MLI) measured in lungs from WT, PEDF+/−, and PEDF−/− P13 mice after 8 days of exposure to either RA or hyperoxia. WT mice exposed to hyperoxia have less gas exchange surface area (i.e., higher MLI) compared with RA-exposed mice. Lungs from PEDF−/− mice exposed to hyperoxia have a larger gas exchange surface area (i.e., lower MLI) compared with the lungs from hyperoxia-exposed WT mice. Data presented are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 6. *P < 0.05 compared with RA WT; **P < 0.05 compared with hyperoxia-exposed WT. (F) Radial alveolar counts measured in lungs from WT and PEDF−/− P13 mice after 8-day exposure to either RA or hyperoxia. WT mice exposed to hyperoxia had a significantly lower alveolar count compared with RA-exposed mice (*P = 0.0001). This decrease after hyperoxia exposure was not seen in lungs from PEDF−/− mouse lungs.

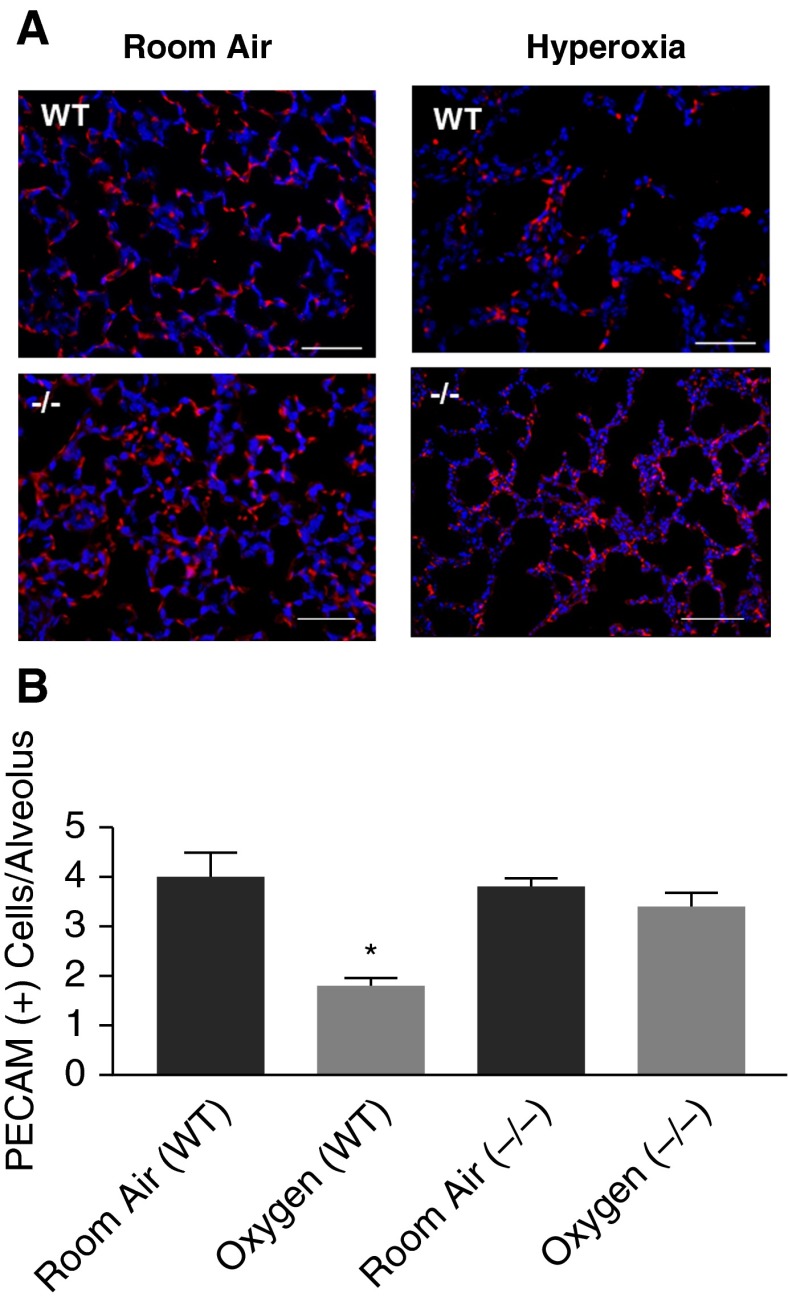

Immunofluorescence for Lung Endothelial Cells

We studied PECAM expression in RA or hyperoxia lungs as an indirect evaluation of microvascular changes. PECAM expression was similar by Western blot in WT and PEDF−/− mouse lungs exposed to RA. However, in both conditions, oxygen exposure resulted in a similar decrease in PECAM (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). The effect of hyperoxia on PECAM protein levels in WT lungs agrees with the results of Yee and colleagues (24), who reported that neonatal hyperoxia decreased PECAM mRNA on P4 and P10. In contrast, Shin and colleagues (25) reported that PECAM protein levels in endothelial cells isolated from adult PEDF−/− lungs was less than that of endothelial cells isolated from WT lungs, but the total area of PECAM staining was not different, suggesting less PECAM protein per endothelial cell. To help resolve these contrasting results, we examined immunofluorescence of PECAM in WT and PEDF−/− lungs after RA or hyperoxia. PECAM-positive cells appeared fewer in hyperoxia-exposed compared with RA-exposed WT mice (Figure 4A); this decrease was not seen in PEDF−/− hyperoxic lungs. We then counted PECAM-positive cells per alveolar structure (see the online supplement). Hyperoxia reduced the number of PECAM-positive cells per alveolus in WT mice, but not in PEDF−/− mice (Figure 4B). These data suggest the possibility that hyperoxic WT lungs have fewer microvessels, and that this is reversed by PEDF−/−. However, this result is not a direct measure of microvessel numbers. To further evaluate this possibility, we used in vitro studies of the effects of PEDF and VEGF on endothelial cell function.

Figure 4.

PEDF KO prevents loss of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-positive cells in hyperoxia. (A) Representative images of PECAM immunofluorescence staining (red) from P13 mouse lungs after exposure to RA or hyperoxia. WT, WT lungs; (−/−), PEDF KO lungs. Blue DAPI stain shows cell nuclei. Hyperoxia dramatically reduces the number of PECAM-positive cells in WT lungs. This reduction is less prominent in PEDF−/− lungs exposed to hyperoxia. Scale bars represent 50 μM. (B) Quantification of PECAM-positive cells per alveolus. Hyperoxia significantly reduced the number of PECAM-positive cells per alveolus. This reduction was absent in hyperoxia-exposed PEDF−/− lungs. Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = ≥3. *P < 0.05 compared with WT RA.

Effect of PEDF on Endothelial Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Tube Formation

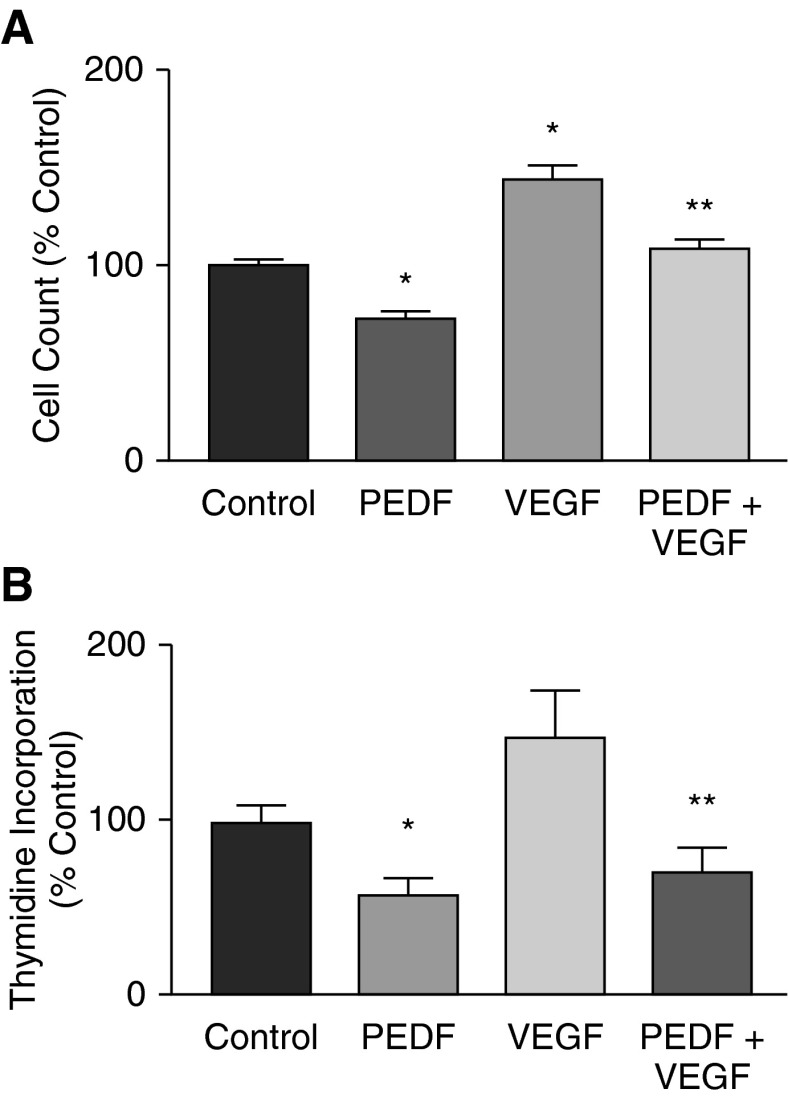

A prominent feature of BPD is arrested microvascular development. It is important to identify how pro- and antiangiogenic signals interact to produce this component of BPD. We therefore further evaluated our hypothesis that arrested microvascular development in neonatal hyperoxic lung injury is a product of altered balance of pro- and antiangiogenic factors by evaluating the combined effects of VEGF and PEDF on developing lung endothelial cell behavior in vitro. Proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis by endothelial cells are important components of microvascular development. VEGF is a prominent promoter of endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation in vitro. We proposed that PEDF would reverse these actions of VEGF. We first determined the effect of PEDF without and with VEGF on developing lung endothelial cell proliferation and migration (MFLM-91U cells; see the online supplement). Dose–response experiments showed that a minimum dose of 20 ng/ml PEDF was sufficient to affect proliferation, and that inhibition was maximal at 50 ng/ml (data not shown). MFLM-91U cells were treated with PEDF alone or with a combination of PEDF (50 ng/ml) and VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 24 hours. PEDF alone decreased cell numbers by 27% (control, 100 ± 2.3%; PEDF, 73 ± 3%). VEGF increased cell numbers and PEDF reversed the VEGF-induced increase in cell numbers to baseline (VEGF, 143 ± 8.3%; VEGF + PEDF, 108 ± 5%; P < 0.05; Figure 5A). We also measured thymidine incorporation. [3H]-thymidine incorporation was inhibited by PEDF (control, 100 ± 1.2%; PEDF, 58 ± 9.5%; P = 0.002), even in the presence of VEGF (VEGF, 149 ± 24.9%; VEGF + PEDF, 71 ± 13%; P = 0.01; n = 4) (Figure 5B). These results show that PEDF inhibits MFLM-91U cell proliferation and overcomes the stimulatory effect of VEGF.

Figure 5.

Effect of PEDF and VEGF on endothelial cell proliferation. (A) Cell count. MFLM-91U cells (3 × 105) were cultured in serum-free medium in 12-well plates without or with 100 ng of PEDF/ml, 50 ng of VEGF/ml, or both for 16 hours. Cell counts were performed using a hemocytometer. Graph shows mean ± SEM of n = 4 experiments of three replicates each. PEDF significantly reduced, and VEGF significantly increased, cell numbers compared with control; PEDF also significantly blocked the VEGF stimulation. *P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with VEGF alone. (B) Thymidine incorporation. MFLM-91U cells (2.5 × 104/well) were cultured in 24-well plates without or with PEDF (200 ng/ml), VEGF (100 ng/ml), or both, with 1 μCi [3H] thymidine per ml of media for 16 hours. Incorporated [3H] thymidine was measured in a β scintillation counter. Graph shows mean ± SEM of n = 3 experiments of three replicates each. *P = 0.001 compared with control; **P = 0.02 compared with VEGF alone.

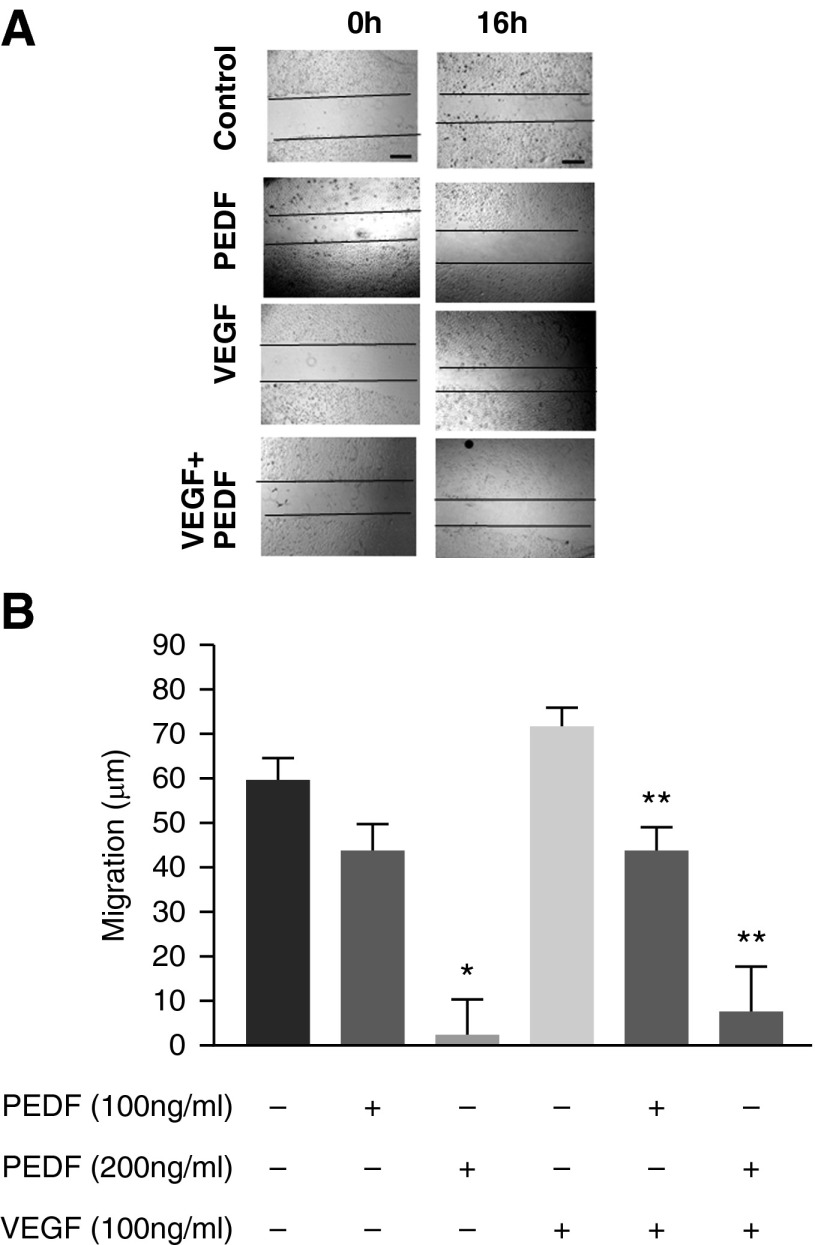

Fetal pulmonary endothelial cell migration was evaluated using a scratch assay (see the online supplement). Migration was increased in the presence of VEGF (50 ng/ml). PEDF (100 ng/ml) alone or with 50 ng/ml of VEGF produced a migratory delay (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PEDF inhibits VEGF-induced cell migration. (A) A scratch gap in confluent monolayers of MFLM-91U cells was made and gap closure measured using microphotographs at 0 and 16 hours. The figures show representative gap closures for untreated, PEDF treated (100 ng/ml), VEGF treated (50ng/ml), and PEDF + VEGF treated. Scale bars represent 100 μM. (B) Quantitative measurement of cell migration measured as microns covered by the cell fronts. VEGF treatment increased endothelial cell migration to close the gap compared with control. PEDF significantly reduced migration in a dose-dependent fashion and inhibited VEGF stimulation also in a dose-dependent manner. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 4 experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with VEGF alone.

Angiogenesis is vital during embryogenesis and organ development. It is an important component of alveolarization, and is inhibited with the development of BPD (1). We analyzed the effect of unbalanced pro- and antiangiogenic factors on angiogenesis in vitro using the well described Matrigel endothelial tube formation assay (26). VEGF (50 and 100 ng/ml) significantly increased tube formation on Matrigel in a dose-dependent manner. The stimulatory effect of VEGF was completely blocked by PEDF (Figure E2).

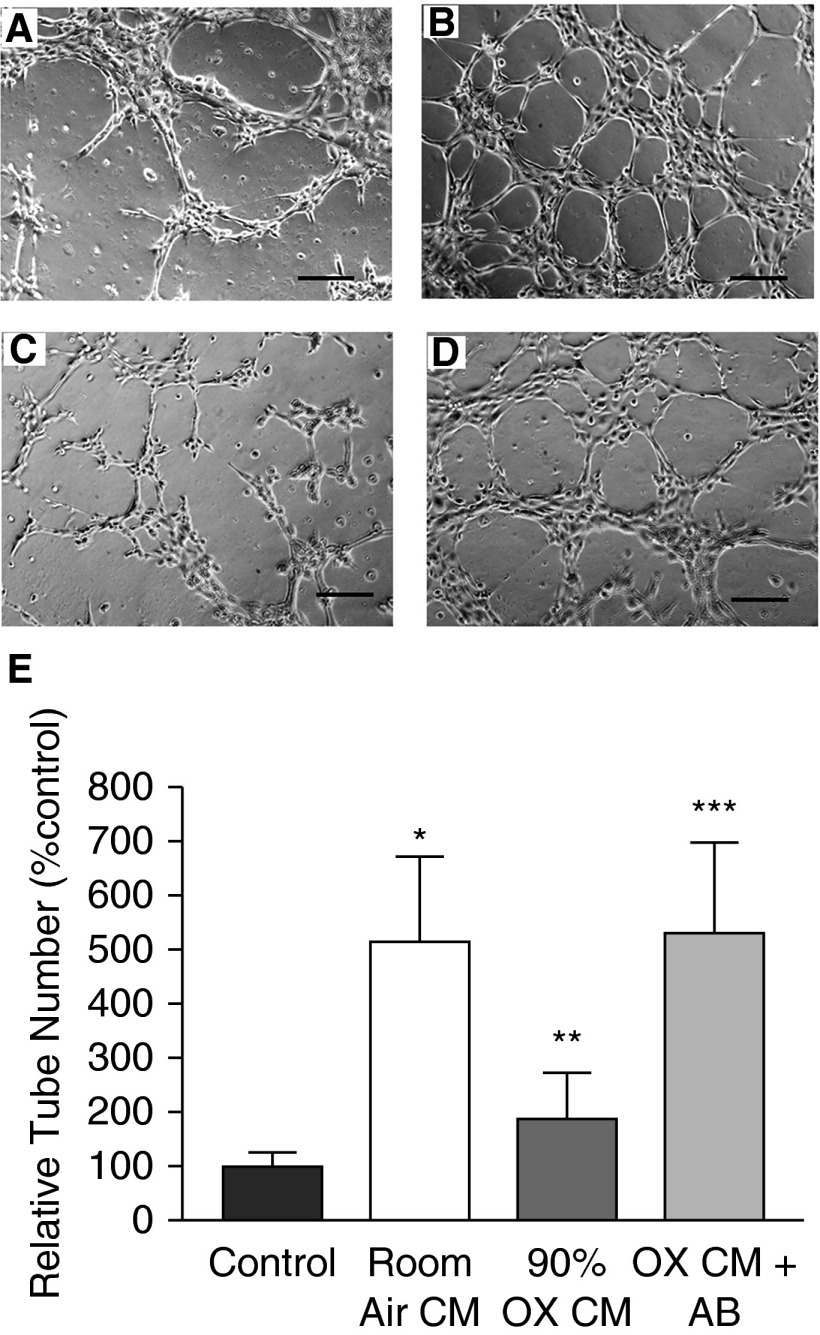

We determined the ability of hyperoxia to promote an antiangiogenic activity mediated by cell–cell communication. Because in situ hybridization, β-Gal staining, and PEDF staining all suggested that alveolar epithelial cells were the major source of PEDF in hyperoxic neonatal lungs, we investigated whether developing T2 cells secreted factors that inhibited endothelial tube formation and if this included PEDF. CM from RA-exposed E17 mouse T2 cells stimulated MFLM-91U cells to form well organized tubes in a dose-dependent manner. Tube formation increased fourfold in 75% RA CM plus 25% culture medium. CM from O2-exposed T2 cells caused a dose-dependent decrease in tube formation (75% CM plus 25% culture medium reduced tube formation to 25% of control; P < 0.05; Figures E3A and E3B). When PEDF antibody was added to the cultures treated with CM from oxygen-exposed T2 cells, tube formation returned to baseline (Figures 7A–7E). PEDF protein was increased in oxygen-exposed E17 T2 cells, as documented by Western blot (data not shown). These results suggest that fetal T2 cells cultured in RA release proangiogenic factor(s), whereas PEDF production and release is increased in fetal T2 cells cultured in hyperoxia. In contrast, CM from oxygen-exposed MLE-12 cells and oxygen-exposed MFLM-91U cells did not inhibit tube formation (Figures E4 and E5).

Figure 7.

Conditioned medium (CM) from oxygen-exposed E17 mouse T2 cells inhibits angiogenesis. Representative figures of vascular tube formation by MFLM-91U cells cultured on Matrigel and treated with (A) control culture medium, (B) CM from E17 T2 cells grown in RA, (C) CM from E17 T2 cells exposed to 90% O2, and (D) CM from E17 T2 cells exposed to 90% O2 + added anti-PEDF antibody. Scale bars represent 100 μM (10×). (E) Bar graph shows mean relative tube counts for each treatment condition. The control culture medium was set as 100%. Data are mean ± SEM of relative tube counts from n = 4 experiments. *P = 0.01 compared with control culture medium; **P = 0.008 compared with RA CM; ***P = 0.007 compared with hyperoxia (OX) CM.

Discussion

In this study, we show that PEDF is markedly increased during hyperoxic lung injury in developing lung, perturbing the important balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors. Our in vitro data show that PEDF has a significant effect on lung microvascular formation and on cell proliferation and migration. In vivo studies indicate that PEDF has a mechanistic function in arrested alveolarization and reduced vascularization with neonatal oxygen injury. These studies suggest that PEDF likely plays a major role in the changes in development of the alveolar unit in neonatal hyperoxic lung injury.

The processes of alveolarization and of microvascular development in the lung appear mechanistically connected, such that disruption of one is associated with disruption of the other. Abnormal microvascular development is present in infants with BPD (1) and in animal models of BPD (27). We and others have shown previously that the lungs of neonatal rodents exposed to hyperoxia exhibited simplified alveoli, with an increased alveolar diameter and impaired septal development (23). In 1959, Liebow observed that the alveolar septae in emphysema are thin and almost avascular (28). He postulated that the reduction in blood supply of the precapillary vessels may explain the disappearance of alveolar septae in emphysema. In this study, we found enhanced PEDF gene and protein expression in alveolar septae and alveolar epithelial cells in hyperoxia-exposed mouse lungs in comparison to RA-exposed lungs. This increased PEDF expression in the alveolar crests and septae was associated with impaired alveolar development and fewer PECAM-positive cells, suggesting impaired microvascular development. Together with our data demonstrating reduced angiogenesis in vitro, these results suggest that Liebow’s hypothesis may apply to neonatal hyperoxic lung injury.

Neonatal mice are particularly well suited for studying the effects of oxygen injury on alveolarization, as alveolar development in mice begins on P3 and is completed on P14. Models of hyperoxic exposure of neonatal mice have been commonly used to study the effects of oxygen on lung alveolarization (23, 29, 30). Investigators have used different oxygen concentrations (commonly 70–90%) and different exposure intervals (beginning on P1–P5, ending on P10–P14). It is important to recognize that these are models of oxygen injury on lung alveolarization, not actual BPD models, which would include degrees of mechanical ventilation and possibly lower oxygen concentrations without or with surfactant replacement (5, 31). However, the neonatal rodent hyperoxia models used by us and others are useful in identifying specific molecular regulatory mechanisms during normal and injury-affected alveolarization. Although most neonates who develop BPD no longer are exposed to prolonged oxygen concentrations in the range of 70–90%, models such as ours remain valuable and relevant because of their ability to probe potential regulatory mechanisms. Further studies in human infants are important to establish the true impact of factors such as PEDF in the development of BPD.

In neonates, changes in ambient oxygen concentration can regulate lung vascular density. This is commonly attributed to reduced levels of angiogenic inducers, such as VEGF, in high-oxygen environments (32, 33). We identified reduced lung VEGF protein levels with hyperoxic exposure, as have all models of neonatal hyperoxic exposure (32, 34). However, antiangiogenic drugs impaired both pulmonary vascular and alveolar development in rats, demonstrating that active blockade of angiogenesis and arrested alveolar septation are closely related (35). PEDF, also known as EPC-1, was first reported in retinal pigment epithelial cells (36). Its antiangiogenic activity was first described by Park and others (15). Although much is known about the importance of this angiostatic factor in ischemic vascular retinopathies and macular degeneration, information on its role in developing lung is lacking.

To determine if PEDF is regulated in neonatal mouse lungs by hyperoxic lung injury, we exposed neonatal mice to RA or 90% oxygen from P5 to P13. We found a significant increase in PEDF protein in the lungs exposed to hyperoxia. This effect does not appear to be unique to one specific strain of mice. Using in situ hybridization, we found that both airway and alveolar epithelial cells showed higher expression of PEDF. It is significant that this is also the major site of VEGF production in developing lung (37).

To test the interactive balance between VEGF and PEDF on developing lung endothelial cell behaviors, we used a fetal mouse lung cell line (MFLM-91U) commonly used to model endothelial cells (38). These cells were developed from a stage in fetal mouse lung development that corresponds to the saccular stage of human lung development, the stage at which prematurely born infants are at a greater risk of developing BPD. PEDF significantly reduced the proliferation of MFLM-91U cells by 27% and blocked VEGF-induced proliferation.

These results were corroborated using a scratch model assay of wound healing, in which a fixed-width scratch in a cell monolayer was created and the advancement of the migrating front was measured in the presence of VEGF and PEDF alone or in combination. Cell proliferation and migration in response to this injury was reduced in the presence of PEDF in a dose-dependent fashion. This reduction was seen even in the presence of VEGF. In organs undergoing repair, including developing organs, such as the lung, cell proliferation and migration are important (39). Unbalanced control of these events may lead to inappropriate repair. Taken together, our studies indicate that PEDF inhibits cell proliferation and migration in developing lung endothelial cells, suggesting that unbalanced control of endothelial cell proliferation and migration may exist in hyperoxic neonatal lungs.

Angiogenesis is important and functionally relevant in physiological events such as embryonic development and in tissue repair and injury. Reduced angiogenesis at the alveolar level is an important feature of BPD. We found that PEDF inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenesis in MFLM-91U cells, similar to the reduction seen after exposure of these cells to hyperoxia. There are several potential mechanisms that have been described by which PEDF may antagonize vascular development (40). One mechanism by which PEDF acts is by interfering with VEGF signaling; however, different pathways by which this occurs, including competition for the VEGF receptor, metabolism of the VEGF receptor, and stimulation of apoptosis, have been described. We were unable to identify any effect of PEDF on VEGF receptor, VEGF receptor phosphorylation, or on apoptosis in the MFLM-91U cells (data not shown). Other signaling pathways not directly interacting with VEGF signaling have been identified (40), and our results may indicate activation of such pathways. In the current study, the combination of the interactive effect of markedly increased PEDF with a less profound decrease in VEGF levels in the lung, plus the in vitro studies of endothelial cell behavior in response to VEGF, PEDF, and VEGF plus PEDF suggest that mechanistic competition for control of endothelial cell behavior may explain the observed changes in lung alveolarization and microvascularization in hyperoxic injury to the development of the alveolar unit. Further studies are needed to identify the molecular mechanisms by which PEDF interferes with lung alveolarization and microvascular development.

As our in situ hybridization and β-Gal immunofluorescence results indicated that PEDF is produced in neonatal T2 cells in response to oxygen, we further investigated the nature of T2 cell–mediated inhibition of angiogenesis. We exposed fetal T2 cells to RA or hyperoxia and collected conditioned media, which were used to test for antiangiogenic properties. MFLM-91U cells exposed to RA-exposed T2 cell CM formed an organized tubular network. However, CM from hyperoxia-exposed T2 cells inhibited the formation of this tubular network in a dose-dependent manner. This inhibitory effect was abolished by added PEDF antibody, indicating that the secreted angiostatic product from the hyperoxia-exposed fetal T2 cells is PEDF. This angiostatic effect of conditioned media was specific to developing T2 cells, as conditioned media from neither oxygen-exposed MFLM-91U cells nor MLE12 cells inhibited tube formation.

Because PEDF is an antiangiogenic factor, and significantly increased PEDF levels are associated with arrested alveolarization in hyperoxia-exposed WT neonatal mice, we used PEDF knockout mice to directly test the role of PEDF in hyperoxia-induced arrested alveolarization and vascularization. We documented that both WT and PEDF+/− heterozygote pups exposed to hyperoxia exhibited impaired alveolarization. This impairment was not seen in PEDF−/− mouse lungs, indicating that loss of PEDF expression rescued the mice from oxygen-induced alveolar arrest. Furthermore, vascular development was impaired in WT and PEDF+/− hyperoxic mice (fewer PECAM-positive cells per alveolar structure compared with RA-exposed mouse lungs). Again, hyperoxia-exposed PEDF−/− mouse lungs had a similar level of PECAM-positive cells per alveolus as the WT mice exposed to RA.

Recently, Shin and colleagues (25) described the behavior of endothelial cells isolated from adult PEDF−/− lungs, as well as the effect of PEDF knockout on lung vascularization. Their findings differ from ours in some important ways. They identified PEDF expression in WT endothelial cells, but did not evaluate other lung cells. We also found PEDF expression in MFLM-91U cells, but at much lower levels than cultured fetal T2 cells (data not shown), and used several methods to show the major source of PEDF in developing lung is the alveolar epithelium. Second, they found that endothelial cell PECAM expression was reduced in the PEDF−/− cells compared with WT, whereas we found no difference in total lung PECAM protein in RA. On the other hand, they reported that the pulmonary vascular bed was not affected in PEDF−/− mice, as assessed by the total area of PECAM immunofluorescence–labeled lung tissue. They did not identify vessel numbers, vessel density, or endothelial cell density. These results would suggest that PECAM content per endothelial cell was reduced in PEDF−/− endothelial cells. As we found that total PECAM levels were not different between WT and RA lungs, but that PECAM levels were reduced in oxygen-exposed lungs of WT and PEDF−/− lungs, it was important for us to show that there were indeed fewer PECAM+ cells in our oxygen-exposed WT lungs, but not in PEDF−/− lungs, to provide better insight into the potential role of PEDF on microvascular development during hyperoxia. Next, Shin and colleagues found that, in the Matrigel angiogenesis assay, the PEDF−/− endothelial cells did not organize to initiate tube formation, and concluded that PEDF is necessary for initial endothelial cell organization. Although we found that PEDF actively inhibits both baseline and VEGF-induced tube formation, these results do not necessarily contradict those of Shin and colleagues. Rather, our results demonstrate the interactive tension between proangiogenic VEGF and antiangiogenic PEDF. Our results are also consistent with the known function of PEDF as a potent inhibitor of retinal endothelial cell microvascularization in vivo (14). Finally, Shin and colleagues did not examine the response to hyperoxic stress, did not evaluate lung structure, and did not examine PEDF–VEGF interactive effects. Importantly, the differences between these two studies of PEDF in lung microvascular development emphasize the need for further understanding of the significance of PEDF for normal development, and the importance of a dysregulated pro- and antiangiogenic balance in the development of BPD.

In conclusion, studies indicate that microvascular angiogenesis is necessary for normal alveolarization during lung development, and that oxygen injury of the developing lung arrests both alveolarization and development of the microvascular bed. We have shown that PEDF is up-regulated in the developing alveolar unit during hyperoxic exposure. The sites of up-regulation are consistent with structures the development of which is restricted in neonatal lung hyperoxia. In vitro studies indicate that PEDF impairs capillary and alveolar development. Our in vivo results show, for the first time, that PEDF regulates arrested development of the alveolar unit in neonatal hyperoxic lung injury. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that there is a reciprocal regulation between PEDF and VEGF in the mouse lung after hyperoxic exposure. This may represent an important mechanism for development of BPD (i.e., interruption of a balance that is important for normal angiogenesis and microvascular remodeling during alveolarization). The increase in PEDF levels is, at least partially, responsible for inhibition of angiogenesis and alveolar formation in oxygen-exposed developing lungs. We propose that the angiogenic stimulator and angiogenic inhibitor systems have complex interactions that represent an important mechanism for maintaining the homeostasis of alveologenesis and associated angiogenesis. The detailed mechanisms responsible for these interactions remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stanley J. Wiegand (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) for supplying the pigment epithelium–derived factor (PEDF) transgenic mice, and Dr. Janis Lem of the Tufts Transgenic Animal Core facility for rederivation of the PEDF transgenic animals.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 HL037930, RO1 HL085648, and R21 HL 097231, and by a grant from the Peabody Foundation.

Author Contributions: A.C. contributed toward conception, design, and analysis of experiments, and preparation of the manuscript; M.B. contributed toward design and conducting of experiments and data analysis; S.P.B. contributed toward analysis of the results and writing of the manuscript; D.N., G.-j.C., L.D., and S.M. contributed toward design and conducting of experiments; M.V. and I.H. contributed toward design of the experiments; H.C.N. contributed toward conception, experimental design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0229OC on July 23, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coalson JJ. Pathology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:179–184. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coalson JJ, Winter VT, Siler-Khodr T, Yoder BA. Neonatal chronic lung disease in extremely immature baboons. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1333–1346. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9810071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maniscalco W, Watkins RH, Pryhuber G, Bhatt A, Shea C, Huyck H. Angiogenic factors and alveolar vasculature: development and alterations by injury in very premature baboons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L811–L823. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00325.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albertine KH, Jones GP, Starcher BC, Bohnsack JF, Davis PL, Cho SC, Carlton DP, Bland RD. Chronic lung injury in preterm lambs: disordered respiratory tract development. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:945–958. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tambunting F, Beharry KD, Waltzman J, Modanlou HD. Impaired lung vascular endothelial growth factor in extremely premature baboons developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease. J Investig Med. 2005;53:253–262. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albertine KH, Dahl MJ, Gonzales LW, Wang ZM, Metcalfe D, Hyde DM, Plopper CG, Starcher BC, Carlton DP, Bland RD. Chronic lung disease in preterm lambs: effect of daily vitamin A treatment on alveolarization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L59–L72. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00380.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janer J, Andersson S, Haglund C, Lassus P. Pulmonary endostatin perinatally and in lung injury of the newborn infant. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e241–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becerra SP. Structure–function studies on PEDF: a noninhibitory Serpin with neurotrophic activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;425:223–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yabe T, Sanagi T, Yamada H. The neuroprotective role of PEDF: implication for the therapy of neurological disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:259–266. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becerra SP. Focus on molecules: pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:739–740. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikpranbabu S, Ravinarayanan H, Elayappan B, Jongsun P, Gurunathan S. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor- and interleukin-1beta–induced vascular permeability and angiogenesis in retinal endothelial cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;52:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SX, Wang JJ, Gao G, Parke K, Ma JX. Pigment epithelium-derived factor downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression and inhibits VEGF–VEGF receptor 2 binding in diabetic retinopathy. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37:1–12. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Q, Wang S, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. PEDF-deficient mice exhibit an enhanced rate of retinal vascular expansion and are more sensitive to hyperoxia-mediated vessel obliteration. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park K, Lee K, Zhang B, Zhou T, He X, Gao G, Murray AR, Ma JX. Identification of a novel inhibitor of the canonical Wnt pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3038–3051. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01211-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce MC, Bruce EN, Janiga K, Chetty A. Hyperoxic exposure of developing rat lung decreases tropoelastin mRNA levels that rebound postexposure. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:L293–L300. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.3.L293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zosky GR, Janosi TZ, Adamicza A, Bozanich EM, Cannizzaro V, Larcombe AN, Turner DJ, Sly PD, Hantos Z. The bimodal quasi-static and dynamic elastance of the murine lung. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:685–692. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90328.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. ATS/ERS Joint Task Force on Quantitative Assessment of Lung Structure: an official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:394–418. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zscheppang K, Liu W, Volpe MV, Nielsen HC, Dammann CE. ErbB4 regulates fetal surfactant phospholipid synthesis in primary fetal rat type II cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L429–L435. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00451.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mujahid S, Nielsen HC, Volpe MV. MiR-221 and MiR-130a regulate lung airway and vascular development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durham JT, Herman IM. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro: a central role for beta-actin dependent cytoskeletal remodeling. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balasubramaniam V, Mervis CF, Maxey AM, Markham NE, Abman SH. Hyperoxia reduces bone marrow, circulating, and lung endothelial progenitor cells in the developing lung: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;92:L1073–L1084. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00347.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chetty A, Cao GJ, Severgnini M, Simon A, Warburton R, Nielsen HC. Role of matrix metalloprotease-9 in hyperoxic injury in developing lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L584–L592. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00441.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee M, Buczynski BW, O' Reilly MA. Neonatal hyperoxia stimulates the expansion of alveolar epithelial type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:757–766. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0207OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin ES, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. PEDF expression regulates the proangiogenic and proinflammatory phenotype of the lung endothelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L620–L634. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00188.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard A, Gao-Li J, Franco CA, Bouceba T, Huet A, Li Z. Laminin receptor involvement in the anti-angiogenic activity of pigment epithelium-derived factor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10480–10490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809259200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coalson JJ. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebow AA. Pulmonary emphysema with special reference to vascular changes. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1959;80:67–93. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1959.80.1P2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warner BB, Stuart LA, Papes RA, Wispe JR. Functional and pathological effects of prolonged hyperoxia in neonatal mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L110–L117. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.1.L110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGrath-Morrow SA, Stahl J. Apoptosis in neonatal murine lung exposed to hyperoxia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:150–155. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.2.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coalson JJ, Kuehl TJ, Escobeda MB. Babboon model of BPD.II: pathologic features. Exp Mol Pathol. 1982;37:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(82)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thebaud B, Ladha F, Michelakis ED, Sawicka M, Thurston G, Eaton F, Hashimoto K, Harry G, Haromy A, Korbutt G, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy increases survival, promotes lung angiogenesis, and prevents alveolar damage in hyperoxia-induced lung injury: evidence that angiogenesis participates in alveolarization. Circulation. 2005;112:2477–2486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esquibies AE, Bazzy-Asaad A, Ghassemi F, Nishio H, Karihaloo A, Cantley LG. VEGF attenuates hyperoxic injury through decreased apoptosis in explanted rat embryonic lung. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:20–25. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815b4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGrath-Morrow SA, Cho C, Cho C, Zhen L, Hicklin DJ, Tuder RM. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade disrupts postnatal lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:420–427. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0287OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jakkula M, Le Cras TD, Gebb S, Hirth KP, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Inhibition of angiogenesis decreases alveolarization in the developing rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L600–L607. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tombran-Tink J, Chader GG, Johnson LV. PEDF: a pigment epithelium-derived factor with potent neuronal differentiative activity. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53:411–414. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90248-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassus P, Ristimaki AR, Ylikorkala O, Viinikka L, Anderson S. Vascular endothelial growth factor in human preterm lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1429–1433. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9806073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akeson AL, Wetzel B, Thompson FY, Brooks SK, Paradis H, Gendron RL, Greenberg JM. Embryonic vasculogenesis by endothelial precursor cells derived from lung mesenchyme. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:11–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200001)217:1<11::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen HC, Martin A, Volpe MV, Hatzis D, Vosatka RJ. Growth factor control of growth and epithelial differentiation in embryonic lungs. Biochem Mol Med. 1997;60:38–48. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1996.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becerra SP, Notario V. The effects of PEDF on cancer biology: mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;2013:258–271. doi: 10.1038/nrc3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]