Summary

Background

Standard treatments for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (iNHLs) are frequently toxic, and most patients ultimately relapse. Lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory agent, is effective as monotherapy for relapsed iNHL. The aim of this phase 2 trial (NCT00695786) was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide plus rituximab in untreated, advanced-stage iNHL and determine the combinaton’s effect on the immune system and tumour microenvironment. The primary objective was to determine the number of complete and partial responses.

Methods

For follicular lymphoma (FL) and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), lenalidomide was given orally at 20 mg/day on days 1–21 of all 28-day cycles. Dosing for small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) began at 10 mg/day to avoid tumour flare. Rituximab was given at 375 mg/m2 body surface area on day 1 of each cycle. Patients responding after 6 cycles could continue therapy for up to 12 cycles. Patients were evaluated for response analysis if they had any post-baseline tumor assessment.

Findings

The study enrolled 110 patients, and 103 were evaluable for efficacy analysis. All patients were eligible for safety analysis. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were neutropenia (35%), muscle pain (9%), rash (7%), cough/dyspnea (7%), fatigue (5%), thrombosis (5%), and thrombocytopenia (4%). The overall response rate was 90% (93/103) (95% confidence interval [CI] 83–95%). Complete and partial response rates were 63% (95% CI 53–72%) and 27% (95% CI 19–37%), respectively. Eighty-seven percent (95% CI 74–95%) and 11% (95% CI 4–24%) of FL patients achieved complete and partial responses, respectively. Seventy-nine percent of evaluable FL patients remained in remission at 36 months.

Interpretation

Lenalidomide plus rituximab is well tolerated and highly effective as initial treatment for iNHL. Durable response rates obtained without cytotoxic agents suggest this regimen could replace chemotherapy as the frontline treatment of iNHL. An international phase 3 study (NCT01476787) is ongoing comparing this regimen to chemotherapy in untreated follicular lymphoma.

Funding

The study was funded by Celgene Corporation and the Richard Spencer Lewis Memorial Foundation.

Introduction

Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (iNHLs), including follicular lymphoma (FL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)/chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), are a group of slow-growing B-cell malignancies with heterogeneous outcomes following standard frontline therapy.1 Current therapeutic approaches range from “watchful waiting” to treatment with options that include rituximab with or without chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and radioimmunotherapy.2,3 Treatment selection for an individual patient depends on a multitude of factors, including disease stage and iNHL category.

Despite advances in therapy, most iNHLs are currently considered incurable,2 treatment toxicity is common, and most patients relapse. Therefore, novel therapeutic non-chemotherapy options, that combine improved response rates and remission duration with low toxicity, are needed. Toward this goal, we tested a combination of biologic agents with lenalidomide and rituximab in subjects with iNHL.

Lenalidomide (Revlimid®), a thalidomide derivative, is a second-generation immunomodulatory drug. Lenalidomide monotherapy has shown efficacy in both relapsed and untreated iNHL,4–6 as well as in aggressive lymphomas such as mantle cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.7–9 At a cell-biological level, lenalidomide exerts therapeutic effects on both the tumour and its microenvironment. It enhances the proliferative and functional capacity of T cells, repairs effector T-cell synapses, increases natural killer (NK) cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC),10–14 upregulates co-stimulatory molecules on the tumour cell surface,13 and has non-immunomodulatory actions that include inhibition of angiogenesis.15 The effects of lenalidomide on tumour cells include modulation of essential and/or oncogenically activated signalling pathways involving transcription factors IRF4, NFκB, Ikaros, and Aiolos.16–19 The molecular action of lenalidomide, and the related development of resistance, involve its binding to protein targets cereblon, Ikaros, and Aiolos, and subsequent effects on protein ubiquitination and degradation.20

The combination of lenalidomide plus rituximab demonstrates synergistic effects against lymphoma in vitro and in animal models, by enhancing rituximab-induced apoptosis and rituximab-dependent NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11,12,15,21 In view of the proven efficacy of rituximab in iNHL,22–24 the observed efficacy of lenalidomide combined with rituximab inrelapsed/refractory iNHL,25 and the expectation of synergy between these agents, we undertook a phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide plus rituximab in patients with untreated, advanced-stage iNHL, and to examine the effects of lenalidomide on the immune system and tumour microenvironment.

Methods

Patients

After providing informed consent, patients were enrolled into this institutional review board-approved study from June, 2008 through August, 2011. Eligibility criteria included: untreated stage III or IV FL, MZL (nodal or extranodal), or SLL; age ≥ 18 years (no upper limit); and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status <2, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1·5 × 109/L, platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L, and adequate organ function. Patients were ineligible if they had any malignancy within the last 5 years, an uncontrolled serious medical condition, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or active hepatitis B or C. The study was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines.

Study therapy

In this open label, phase 2 single-arm, single institution study, patients with FL and MZL received lenalidomide 20 mg/day on days 1–21 of each 28-day cycle. Dosing of lenalidomide and rituximab was based upon our findings in our previously reported phase I study of this combination in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma.26 To avoid tumour flare, patients with SLL started at lenalidomide 10 mg/day, with a monthly 5 mg escalation to 20 mg/day. All patients received rituximab at 375 mg/m2 on day 1. Patients with tumour response after 6 cycles could continue therapy for up to 12 cycles. Prophylactic growth factors were not used. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT00695786.

Study oversight

In this investigator-initiated study, the investigators collected and compiled the data, and were responsible for statistical analyses and interpretation. The authors vouch for the completeness and veracity of the data, as well as the fidelity of the report to the trial protocol. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Response assessment

The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) according to the International Working Group Criteria for Non-Hodgkins Lymphomas.27 Patients were evaluable for efficacy analysis if they had one response assessment. Response was determined by computed tomography (CT) scans, and bone marrow biopsy was performed where indicated to confirm CR. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scans were conducted pre- and post-treatment in FL patients, and were interpreted according to the International Harmonization Project recommendations.28 Two independent nuclear medicine physicians reviewed equivocal or indeterminate findings. Tumour assessment (CT scan and physical exam) was performed at study entry, every 3 months for 2 years, every 6 months in year 3, and then annually. Bone marrow biopsy was performed at 3 months and 6 months to confirm response. Molecular response in FL was evaluated in bone marrow and/or peripheral blood samples by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect t(14;18) IGH-BCL2 fusion DNA sequences.

Secondary endpoints included: CR and PR rates; progression-free survival (PFS), measured from study drug administration until lymphoma progression or death from any cause; overall survival (OS), measured from study drug administration until death; safety; and effects of treatment on the tumour and immune cells (see appendix [Methods]). Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (version 3.0).

Statistical analysis

The trial was initially designed as a 30-patient, phase 2, pilot study, but was expanded following preliminary analysis demonstrated significant activity in the study population. The planned sample size of the expanded study was 110 patients: 50 FL, 30 MZL, and 30 SLL. Efficacy and toxicity were monitored simultaneously in each of the iNHL subgroups, using the Bayesian approach of Thall, Simon, and Estey.29–31 For MZL and FL cohorts, the null hypothesis predicted an ORR of ≤ 70%. We expected to improve the ORR to ≥80% with the current regimen. The proposed sample sizes for FL and MZL were expected to achieve a width of 0·19 and 0·23, respectively, for the posterior 90% credibility interval under the assumption of an ORR of 80%. For the SLL cohort, we expected to improve the ORR from 50% to ≥ 60%, and 30 patients were planned to achieve a width of 0.28 for the posterior 90% credibility interval under the assumption of a 60% ORR.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used for time-to-event analyses. For PFS analysis, patients were censored at the last follow-up date if neither progression nor death occurred. For OS analysis, patients were censored at the last follow-up date if death did not occur. Seven unevaluable patients (see Results section below) were excluded from the PFS analysis; all patients were included in the OS analysis. Median time to event, in months, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), was calculated. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test whether the percentage change in a biomarker from baseline to post-therapy was different from zero. The association between response status and other patient characteristics was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical software SAS 9.1.3 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and S-PLUS® 8.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) were used for all analyses.

Role of the funding source

This was an investigator-initiated study. The sponsors played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing. NF, RED, SR, FS, and SSN had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Patients

Of the 110 patients enrolled, 50 (45·4%) had FL, 30 (27·3%) had MZL, and 30 (27·3%) had SLL. Baseline characteristics are summarised in table 1. Thirty-nine (78%) FL patients had a Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score of ≥ 2.32 All patients had stage III/IV disease, and 57 (52%) met the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria for high tumour burden.33 Seven patients were not evaluable for response: five due to AEs in cycle 1 without response assessment, one due to non-compliance, and one due to withdrawal of consent.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | FL (n=50) | MZL (n=30) | SLL (n=30) | All (n=110) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 56 | 59 | 59 | 58 |

| Range | 35–84 | 36–77 | 34–76 | 34–84 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 22 (44) | 18 (60) | 12 (40) | 52 (47) |

| Stage, n (%) | ||||

| III | 23 (46) | 9 (30) | 0 (0) | 32 (29) |

| IV | 27 (54) | 21 (70) | 30 (100) | 78 (71) |

| High tumour burden (per GELF), n (%) | 27 (54) | 13 (43) | 14 (47) | 57 (52) |

| FLIPI score, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 11 (22) | - | - | |

| 2 | 25 (50) | - | - | |

| 3–5 | 14 (28) | - | - | |

FL=follicular lymphoma. MZL=marginal zone lymphoma. SLL=small lymphocytic lymphoma. GELF=Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes Folliculaires. FLIPI=follicular lymphoma international prognostic index.

Safety

The most frequent non-haematologic AEs (all grades, occurring in >50% of patients) were fatigue, pain/myalgia, nausea, irritation of the eyes, rash, and constipation (table 2). Most events were of grade 1 or 2 severity. Rash was observed in 58% of patients, and was generally mild and self-limiting. The most common grade 3 or 4 non-haematologic AEs, occurring in >2% of patients, were pain/myalgia (9%), rash (7%), cough/dyspnea (7%), and fatigue and thrombosis (5% each) (table 1 in the appendix). Thirty one patients (28%) required dose reduction. Consistent with prior reports,34 we observed thyroid abnormalities in 23% of patients; although most cases were associated with an asymptomatic rise in thyroid-stimulating hormone and normal free tri-iodothyronine and thyroxine, five cases required hormone replacement therapy.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events occurring in >10% of patients

| Adverse events | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | All grades |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematologic, n (%) | |||||

| Anaemia | 61 (55) | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 69 (63) |

| Neutropenia | 14 (13) | 32 (29) | 27 (25) | 11 (10) | 84 (76) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 48 (44) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 56 (51) |

| Non-haematologic, n (%) | |||||

| Constipation | 31 (28) | 26 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 57 (52) |

| Cough/dyspnoea | 33 (30) | 15 (14) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 55 (50) |

| Infusion reaction | 6 (5) | 9 (8) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 17 (15) |

| Diarrhoea | 35 (32) | 20 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 55 (50) |

| Dizziness | 33 (30) | 14 (13) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 48 (40) |

| Oedema | 39 (35) | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 48 (44) |

| Eye irritation | 54 (49) | 11 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 65 (59) |

| Fatigue | 45 (41) | 49 (45) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 99 (90) |

| Fever | 34 (31) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 40 (36) |

| Memory impairment | 27 (25) | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 37 (34) |

| Mucositis | 36 (33) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 37 (34) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 40 (36) | 27 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 67 (61) |

| Pain/myalgia | 38 (35) | 40 (36) | 10 (9) | 0 (0) | 90 (82) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 32 (29) | 8 (7) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 41 (37) |

| Rash | 33 (30) | 23 (21) | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | 64 (58) |

| Thyroid abnormalities | 15 (14) | 10 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (23) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 0 (0) | 23 (21) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 25 (23) |

Regarding haematologic toxicity, 38 patients (35%) experienced grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, and neutropenic fever occurred in five patients. Grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in four patients (4%). Second malignancies were reported in five patients aged >53 years after initiation of lenalidomide, with one case each of localised melanoma, ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast, multiple myeloma, localised prostate cancer, and recurrent bladder cancer. Six patients stopped treatment due to AEs: two due to rituximab infusion reaction, one due to rash, one due to thrombotic events, one due to grade 3 myalgia, and one following an episode of transient respiratory distress. There were no treatment-related fatalities.

Efficacy

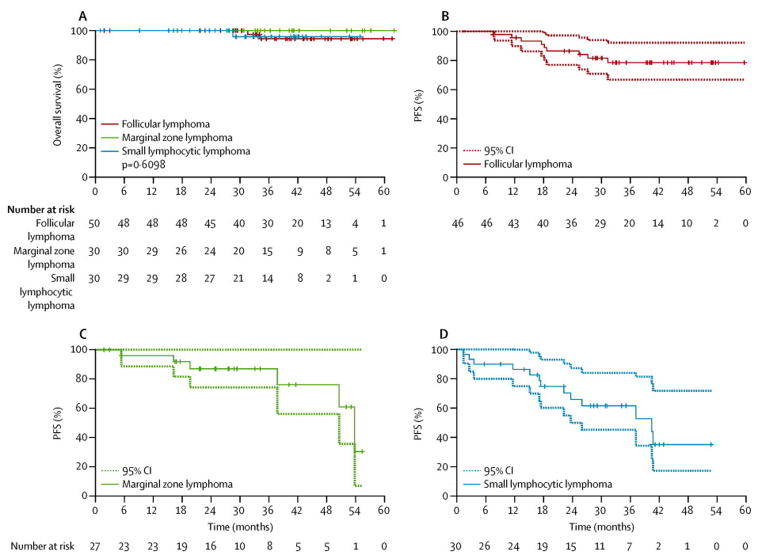

The ORR of all evaluable patients was 90% (93/103), and was high in all iNHL types (table 3). Sixty-five patients (63%) achieved a CR, and 28 (27%) achieved a PR. After a median follow-up of 38.2 months (range 1·0–62·0 months), there were 28 events (progression or death). The observed median PFS for the entire cohort was 53·8 months (95% CI 50·6–not available [NA]), and the estimated 3-year OS was 96.1% (95% CI 91·9–100%; figure 1A).

Table 3.

Clinical outcome after therapy

| Variable | FL (n=46) | MZL (n=27) | SLL (n=30) | All evaluable patients (n=103) | ITT population (n=110) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response, n (%;95% CI) | |||||

| Overall | 45 (98; 88–100) | 24 (89; 71–98) | 24 (80; 61–92) | 93 (90; 83–95) | 93 (85;76–91) |

| Complete | 40 (87; 74–95) | 18 (67; 46–83) | 7 (23; 10–42) | 65 (63; 53–72) | 65 (59; 49–68) |

| Partial | 5 (11; 4–24) | 6 (22; 9–42) | 17 (57; 37–75) | 28 (27; 19–37) | 28 (25; 18–35) |

| Progression-free survival* | |||||

| 3-year, % | 78·5 | 87·0 | 61·6 | 75·3 | |

| 95% CI | 66·8–92·2 | 74·2–100·0 | 45·2–83·9 | 66·7–85·0 | |

| Median, months | NR | 53·8 | 40·4 | 53·8 | |

| 95% CI | 50·6–NA | 23·6–NA | 50·6–NA | ||

| Overall survival** | |||||

| 3-year % | 94 | 100 | 96 | 96 | |

| 95% CI | 87·2–100·0 | 100·0–100·0 | 88·2–100·0 | 91·8–100·0 | |

FL=follicular lymphoma. ITT=intent to treat. MZL=marginal zone lymphoma. SLL=small lymphocytic lymphoma. CI=confidence interval. NA=not available. NR=not reached.

Progression-free survival analysis was based on the 103 evaluable patients.

Overall survival analysis was based on the ITT population of 110 patients.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival and PFS in patients with indolent lymphoma receiving lenalidomide plus rituximab.

Lenalidomide plus rituximab was administered to 110 patients with untreated iNHL. At a median follow-up of 38 months, the 3-year overall survival for the entire group was 96% (A). Three patients died during follow-up: 2/50 in the FL group, and 1/30 in the SLL group. In patients with FL, the 3-year PFS was 78·5% (B). The median PFS for patients with marginal zone lymphoma and SLL was 53·8 months (C) and 40·4 months (D), respectively. FL=follicular lymphoma. iNHL=indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. PFS=progression-free survival. SLL=small lymphocytic lymphoma.

FL

An objective response was observed in 45 (98%) of the 46 evaluable FL patients. Forty (87%) achieved a CR/unconfirmed CR (CRu) (76% CR/11% CRu) and 5 (11%) achieved a PR. Nearly all patients attained maximum response by the end of cycle 6, with two patients demonstrating an improved response with extended follow-up. As part of an exploratory analysis, pre- and post-treatment PET scans were obtained and were available for 45 patients, of whom 44 (98%) were PET-positive prior to therapy. After treatment, 42 (93%) patients were PET-negative. Responses were observed irrespective of FLIPI score, GELF criteria, and tumour bulk. The median PFS had not been reached at a median follow-up of 40·6 months (range 1·8–61·6 months). The PFS rate at 3 years was 78·5% (95% CI 66·8–92·2%) (figure 1B). Of the 44 patients evaluated for molecular response, 18 (41%) had detectable IGH-BCL2 fusion by PCR at baseline and, of these, 95% achieved molecular remission after 6 cycles (table 2 in the appendix).

MZL and SLL

Among 27 evaluable MZL patients, the best ORR was 89%, with 18 (67%) achieving a CR and 6 (22%) achieving a PR. Five and two patients in the SLL and MZL subgroups, respectively, demonstrated an improved response (PR to CR) during extended follow-up. The median PFS was 53·8 months (95% CI 50·6–NA) (figure 1C). The ORR in the 30 evaluable SLL patients was 80%, including CRs in 8 (27%) and PRs in 16 (53%). The median PFS in this subgroup was 40·4 months (95% CI 23·6–NA), with 13 patients experiencing an event (figure 1D).

Immunological effects

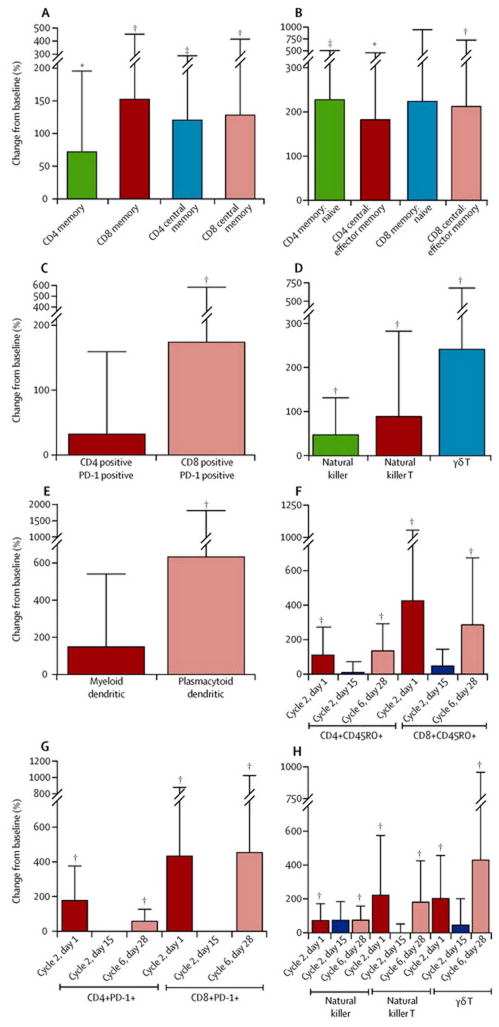

We assessed immune cell subsets in the peripheral blood of FL patients at baseline and during therapy. Of the 27 FL patients tested, 22 achieved a CR/CRu and 5 achieved a PR. Absolute numbers of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells were comparable at baseline and at the end of 6 cycles (data not shown). However, numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells – in particular, central memory T cells, and the ratios of memory to naïve T cells, and central memory to effector memory T cells – markedly increased after therapy (figures 2A and 2B, table 3 in the appendix). Numbers of CD8+PD-1+ T, NK, NKT, γδ T, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells also increased significantly (figures 2C–E, table 3 in the appendix). Changes in these subsets were observed at the earliest time point assessed after initiation of therapy (cycle 2, day 1), and were still evident at the end of 6 cycles. Interestingly, immune cell ratios had returned to baseline when patients were assessed mid-cycle (cycle 2, day 15; figures 2F–H, table 4 in the appendix), perhaps reflecting acute effects of actively receiving lenalidomide.

Figure 2. Changes in immune cell subsets in peripheral blood after rituximab and lenalidomide therapy.

(A–E) Immune cell subsets were determined by flow cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in 27 FL patients. Percentage change from baseline in absolute numbers or their ratios at cycle 6, day 28 (C6D28) of rituximab and lenalidomide therapy is shown. (F–H) Percentage change from baseline in immune cell subsets at C2D1, C2D15, and C6D28 of rituximab plus lenalidomide therapy was analysed in 13 FL patients. Percentage change in absolute numbers of immune cell subsets in on-therapy or post-therapy samples relative to baseline was calculated to enable normalisation of the data using the following formula: [(on therapy or post-therapy absolute value – baseline absolute value) × 100/ baseline absolute value]. Paired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate differences in immune cell subsets between the time points. *p<0·05; **p<0·01; ***p<0·001. The immunophenotype used to determine each immune cell subset was as follows: CD4/CD8 Mem (CD4+/CD8+CD45RO+); CD4/CD8 CM (CD4+/CD8+CD45RA−CD27+); CD4/CD8 EM (CD4+/CD8+CD45RA−CD27−); CD4/CD8 naïve (CD4+/CD8+CD45RA+ CD27+); NK cells (CD3−CD56+); NKT cells (CD3+CD1D+); γδ T cells (CD3+TCRγδ+); MDC (Lin−CD11c+CD4+); PDC (Lin− BDCA2+BDCA4+). CM=central memory. EM=effector memory. MDC=myeloid dendritic cells. Mem=memory. NK=natural killer. NKT=natural killer T. PDC=plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

To evaluate lenalidomide-induced effects on the immune system at a molecular level, we performed gene expression profiling (GEP) on 7 pairs of peripheral blood samples from patients with FL. All 7 patients tested achieved a CR. Using a paired t test in the Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) method,35 we identified 1748 differentially expressed genes (713 up, 1035 down) at cycle 2 day 15 compared with baseline (figure 1A in the appendix). Most downregulated genes were attributable to rituximab-induced depletion of B cells, but many upregulated genes indicated activation of immune cells (figure 1B in the appendix). To understand GEP changes on a pathway level, we used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis,36 based on ranking all genes by their paired SAM z-score value. Among significantly enriched upregulated gene sets, many were consistent with activation of multiple immune cell subsets, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells (table 5 in the appendix and figures 1C–L in the appendix), or with changes occurring during immune responses, such as increases in ribosomal protein genes and oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondrial electron transport chain genes; table 5 in the appendix and figures 1M–P in the appendix).

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumour biopsies showed that infiltration of CD4+ T cells decreased, and infiltration of CD8+ T cells increased, with lenalidomide treatment (cycle 1, day 18; table 6 in the appendix). We also observed increased infiltration of PD-1+ cells and increased expression of the co-stimulatory molecule CD80 while patients were on therapy (table 6 in the appendix). The difference in cells expressing CD56 (NK cells) or CD68 (macrophages; data not shown) was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

As initial treatment for iNHL, the combination of rituximab and lenalidomide was much more effective than previously reported for rituximab monotherapy.37,38 The responses were durable in the majority of patients, with a projected median PFS of over 4 years. The combination was particularly effective in FL, in which a 98% ORR was observed and 87% of patients achieved a CR. These findings compare favourably with the 72–73% ORR and 27–36% CR rate reported for rituximab monotherapy.37,38 Responses, confirmed by both CT and PET imaging, were independent of prognostic indicators such as the FLIPI, GELF criteria, and tumour bulk. High rates of clinical response were also associated with molecular remissions in FL patients. Although the study was not designed or powered to compare the effect of rituximab plus lenalidomide across histologies, CR rates and PFS appeared shorter in patients with SLL. These results mirror similar findings from studies with this regimen in CLL, and may reflect a differential impact on the microenvironment in patients with SLL.

These high rates of durable response are comparable to those observed previously with standard chemotherapy plus rituximab.2 With a similar median follow-up, a large randomised study of bendamustine plus rituximab vs cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone plus rituximab (R-CHOP) reported a median PFS of 69·5 months vs 31·2 months.39

The randomised FOLL05 study reported 3-year PFS rates of 52% for rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone, 68% for R-CHOP, and 63% for rituximab plus fludarabine and mitoxantrone.40 Our results suggest that, when combined with rituximab as initial treatment for iNHL, lenalidomide may be substituted for standard chemotherapy without diminishing efficacy. Although similar outcomes were observed regardless of tumour bulk or GELF criteria, high tumour burden was not a requirement for study entry. In addition, we acknowledge the limitations of a single-arm phase 2 study, and suggest that randomised studies are warranted to enable a true comparison of this regimen with chemotherapy.

The toxicity of lenalidomide plus rituximab was generally mild, with mostly grade 1 or 2 AEs that resolved with supportive care. Rash was common but self-limiting, and rarely resulted in therapy discontinuation. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were the most common haematologic toxicities, occurring at rates that compared favourably with those reported with chemoimmunotherapy.

Accumulating evidence points to the importance of the immune response and tumour microenvironment in the development of iNHLs and their response to therapy. Lenalidomide is known to enhance ADCC by NK cells and monocytes,21 but it may also have additional immunomodulatory effects in vivo. We found increases in the memory T, NK, NKT, γδ T, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the peripheral blood on day 28 of cycles 1 and 6, suggesting that lenalidomide may activate many different immune cell subsets. However, trafficking of the activated immune cells to the tumour site is necessary to induce a clinical response. The drop in these immune cell subsets in the peripheral blood while patients were actively receiving lenalidomide (cycle 2, day 15, figures 2F–H) raises the intriguing possibility that lenalidomide may increase the trafficking of activated immune cells to the tumour site, as has been suggested previously.15,41 Consistent with these observations, we found increased numbers of CD8+ T cells in the tumour during lenalidomide therapy, and the increased numbers of PD-1+ cells suggest activation of infiltrating CD8+ T cells. The decrease in intratumoural CD4+ T cells was unexpected; it is possible that lenalidomide therapy reduced the numbers of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells or protumour T-follicular helper cells. Together, these findings indicate that antitumour T cells may be increased in the tumour during lenalidomide therapy, and protumour T cells decreased, consistent with previous reports of lenalidomide activating or suppressing T-cell populations.11,12

Results from GEP studies, showing the upregulation of genes involved with T, NK, and dendritic cell activation, and pathways associated with an immune response, further support the ability of lenalidomide plus rituximab to expand and activate T and NK cells in the tumour environment.15 Collectively, these data add to the body of evidence supporting multiple synergistic mechanisms of action of lenalidomide on various immune cell subsets in the tumour. We did not observe a correlation between immune cell subset changes and clinical outcome, but this was likely due to high rates of response and prolonged PFS, and the modest number of patients. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether these changes can serve as surrogate biomarkers of response, as well as PFS and OS.

Supplementary Material

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

Our study was initiated based on strong evidence from in vitro and animals studies showing synergistic effects against B-cell lymphomas when lenalidomide and rituximab were used in combination. Furthermore, prior studies showed efficacy of this combination in relapsed/refractory iNHL. We carried out a comprehensive literature search of PubMed when writing our report in June 2014. We placed no date or language restrictions on the following search terms: “lymphoma” AND “lenalidomide” AND “rituximab” AND “clinical trial”. Although there were reports of clinical trials with the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab in relapsed/refractory lymphomas, we did not identify any other full papers reporting the use of this combination in untreated iNHL. Recent presentations of data from ongoing US cooperative group trials of lenalidomide and rituximab report significant activity in iNHL, and confirm the potential of this combination in untreated patients.42

Interpretation

The results of our study show that the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab is safe and provides high OR and CR rates, and durable remissions, in patients with untreated SLL, MZL and FL. CR rates and PFS were most impressive in FL. The encouraging results of this trial have laid the foundation for an international phase 3 registration study (RELEVANCE; NCT01476787) to investigate this promising non-chemotherapy treatment approach in a larger number of patients with untreated FL.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the patients who made this study possible, the authors would like to thank the following individuals for their contribution to the study: MD Anderson Cancer Center, Nuclear Medicine: Hubert Chuang MD, Beth Chasen MD; Research Staff: Kathleen Nelson RN, Denise Davis, Shanna White; MD Anderson Cancer Center Biostatistics: Nusrat Harun MS; Celgene: Ken Takeshita MD, Dennis Pietronigo MD. Blood samples were collected and processed by the Lymphoma Tissue Bank, with financial support from Lymphoma SPORE P50CA136411, The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA16672 (National Institutes of Health), and the Fredrick B. Hagemeister Research Fund.

Funding for the study was provided by Celgene Corporation and the Richard Spencer Lewis Memorial Foundation. Assistance with content editing and data verification was provided by Sandralee Lewis of the Investigator Initiated Research Writing Group (part of the KnowledgePoint 360 Group, an Ashfield Company), and was funded by Celgene Corporation.

Footnotes

Contributions

NHF and FS designed the study. NHF, LN, FBH, PM, LWK, JER, MAF, LEF, JRW, JS, RZO, MW, FT, YO, LCC, FS, and SSN participated in patient enrollment, treatment of patients, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. NHF, RED, SR, TM, KYT, and SSN participated in performing correlative studies and analyzing and interpreting the data obtained. LF and VB performed statistical analysis. NHF, RED, LN, and SSN wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Fowler - Celgene: Research Funding, Honoraria (Scientific Advisory Board). Roche: Research Funding. McLaughlin - Celgene: Data Monitoring Committee for a different lenalidomide study. Gilead: Data Monitoring Committee for an idelalisib study. Fanale - Celgene: Research Funding, Honoraria (Speaker). Shah - Celgene: Research Funding, Honoraria (Scientific Advisory Board). Orlowski – Celgene: Research Grant, Advisory Board. Wang - Celgene: Research Funding. Oki – Celgene: Research Grant. Samaniego - Celgene: Research Funding. Neelapu - Celgene: Research Funding.

Davis, Rawal, Nastoupil, Hagemeister, Kwak, Romaguera, Fayad, Westin, Turturro, Claret, Feng, Baladandayuthapani, Muzzafar, and Tsai have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1997;89:3909–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zelenetz A, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. [accessed 3 July 2014];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Version 1.2013. http://wwwnccnorg/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhlpdf.

- 3.Freedman A. Follicular lymphoma: 2012 update on diagnosis and management. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:988–95. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badoux XC, Keating MJ, Wen S, et al. Lenalidomide as initial therapy of elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3489–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CI, Bergsagel PL, Paul H, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in the treatment of previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1175–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiesewetter B, Troch M, Dolak W, et al. A phase II study of lenalidomide in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Haematologica. 2013;98:353–6. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiernik PH, Lossos IS, Tuscano JM, et al. Lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4952–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habermann TM, Lossos IS, Justice G, et al. Lenalidomide oral monotherapy produces a high response rate in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:344–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witzig TE, Vose JM, Zinzani PL, et al. An international phase II trial of single-agent lenalidomide for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1622–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang DH, Liu N, Klimek V, et al. Enhancement of ligand-dependent activation of human natural killer T cells by lenalidomide: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2006;108:618–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Adams M, Carter T, et al. Lenalidomide enhances natural killer cell and monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of rituximab-treated CD20+ tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4650–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsay AG, Clear AJ, Kelly G, et al. Follicular lymphoma cells induce T-cell immunologic synapse dysfunction that can be repaired with lenalidomide: implications for the tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. Blood. 2009;114:4713–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanan-Khan AA, Chitta K, Ersing N, et al. Biological effects and clinical significance of lenalidomide-induced tumour flare reaction in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: in vivo evidence of immune activation and antitumour response. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:457–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDaniel JM, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Epling-Burnette PK. Molecular action of lenalidomide in lymphocytes and hematologic malignancies. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012:513702. doi: 10.1155/2012/513702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy N, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Deeb G, et al. Immunomodulatory drugs stimulate natural killer-cell function, alter cytokine production by dendritic cells, and inhibit angiogenesis enhancing the anti-tumour activity of rituximab in vivo. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Shaffer AL, 3rd, Emre NC, et al. Exploiting synthetic lethality for the therapy of ABC diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:723–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi AK, Kang J, Havens CG, et al. Immunomodulatory agents lenalidomide and pomalidomide co-stimulate T cells by inducing degradation of T cell repressors Ikaros and Aiolos via modulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4(CRBN) Br J Haematol. 2014;164:811–21. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kronke J, Udeshi ND, Narla A, et al. Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science. 2014;343:301–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1244851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu G, Middleton RE, Sun H, et al. The myeloma drug lenalidomide promotes the cereblon-dependent destruction of Ikaros proteins. Science. 2014;343:305–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1244917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart AK. Medicine. How thalidomide works against cancer. Science. 2014;343:256–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1249543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Qian Z, Cai Z, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of lenalidomide and rituximab on mantle cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:553–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal-Celigny P, et al. Phase III study of R-CVP compared with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106:3725–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheson BD, Leonard JP. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:613–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Fowler N, Wagner-Bartak N, et al. Oral lenalidomide with rituximab in relapsed or refractory diffuse large cell, follicular and transformed lymphoma: a phase II clinical trial. Leukemia. 2013;27:1902–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang M, Fayad L, Wagner-Bartak N, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:716–23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, et al. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:571–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thall PF, Simon RM, Estey EH. Bayesian sequential monitoring designs for single-arm clinical trials with multiple outcomes. Stat Med. 1995;14:357–79. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thall PF, Simon RM, Estey EH. New statistical strategy for monitoring safety and efficacy in single-arm clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:296–303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thall PF, Sung HG. Some extensions and applications of a Bayesian strategy for monitoring multiple outcomes in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998;17:1563–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1563::aid-sim873>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solal-Celigny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brice P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1110–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Figaro MK, Clayton W, Jr, Usoh C, et al. Thyroid abnormalities in patients treated with lenalidomide for hematological malignancies: results of a retrospective case review. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:467–70. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colombat C, Salles G, Brousse N, et al. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) as single first-line therapy for patients with follicular lymphoma with a low tumor burden: clinical and molecular evaluation. Blood. 2001;97:101–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witzig TE, Vukov AM, Habermann TM, et al. Rituximab therapy for patients with newly diagnosed, advanced-stage, follicular grade I non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a phase II trial in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1103–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1203–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federico M, Luminari S, Dondi A, et al. R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: results of the FOLL05 trial conducted by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1506–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eve HE, Carey S, Richardson SJ, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: results from a UK phase II study suggest activity and possible gender differences. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:154–63. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin P, Jung S, Johnson J, et al. CALGB 50803(Alliance): a phase 2 trial of lenalidomide plus rituximab in patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31 (suppl 1):063. (abstr) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.