Stuart Pollack, MD, is a primary care internist and the medical director for Brigham and Women’s Advanced Primary Care Associates, South Huntington, in Boston, Massachusetts. The group was founded in 2011 as a demonstration project to test a team-based approach to primary care. The clinic, which currently serves over 7,000 patients, is designated as a Tier 3 patient-centered medical home by the National Committee for Quality Assurance. In this edition of Improvement Happens, JGIM contributor Michael Hochman, MD, MPH, talks with Dr. Pollack about his vision for primary care in the years ahead (Pictures 1 and 2).

Picture 1.

Stuart Pollack, MD, is the medical director of the South Huntington clinic.

Picture 2.

The South Huntington team discusses patient issues during a huddle.

JGIM: What is wrong with primary care in this country, and what could we do better?

Stuart Pollack: There’s a statistic that for the average primary care doctor with 2,500 patients, there is 21.7 hours of work a day. The work has slowly accumulated over the 23 years I’ve been practicing. Once upon a time, for a patient with diabetes, you had a choice between two pills and four kinds of insulin, and the only metric was whether there was sugar in your urine in the morning. Now, we track 15 metrics, and the patient is taking multiple medications to address not only glycemic control, but also blood pressure, cholesterol, and clotting.

I like to joke that when I was young, I could work 21.7 hours a day, but now that I’m getting old, I can’t do it. And these young docs, they don’t want to work 21.7 hours a day. (What in the world is wrong with them?) So the problem is that the amount of care required keeps getting larger and larger, yet we still see the patients in the same 15 minutes.

JGIM: What could make things better?

SP: One solution is we all become concierge doctors and only take care of 800 patients each. Then the job becomes doable. Of course, that means either accepting a world where many people don’t have access to primary care, or figuring out how to triple the number of primary care clinicians—which is just not going to happen, even if we factor physician assistants and nurse practitioners into the equation.

So the only ethical solution I can find is to distribute the work among a team. And that’s where South Huntington and the patient-centered medical home concept kicks in.

JGIM: What was the impetus for founding the South Huntington clinic? What did you hope to accomplish?

SP: The goal was always the triple aim—great patient experience, great population health, and great value—with a fourth aim being great staff and doctor experience. We also had secondary goals around learning to teach trainees to deliver care in a team-based environment, and serving as a learning lab for the Brigham.

JGIM: Can you give an overview of how the clinic runs?

SP: If you’re a fairly healthy person, it’s not a whole lot different compared to a typical office. If you’re sharp, you might notice that the medical assistants ask you more questions when you come in for a visit, and when you come in for a sick visit, we’re bugging you about your colonoscopy, not just today’s problems. And we’re probably going to bug you between visits a bit more too. And if you have a cough, we are happy to treat you by phone or e-mail, and if you want to be seen the day you call, it usually happens, and we are open until 7 p.m., so maybe you don’t have to leave work early. And we are open on Saturday also. But the differences really aren’t that dramatic.

On the other hand, if you’re really sick, the clinic is very different. You come in, you meet me for the first time, and by the time we’re done, the pharmacist has shown up in the room and maybe a social worker, and you have appointments with them. And we’re calling you every week, and then all of a sudden you realize the care isn’t being provided by the doctor alone. Our sickest patients probably have seven or eight people on their team.

JGIM: You have taken a team-based approach with your clinic. How have you done this?

SP: When building the team, we took a “form follows function” approach. So, instead of saying we’re going to have three doctors and two physician assistants and a nurse, we talked about what roles you need in primary care: who’s going to see patients with symptoms, who’s going to reconcile medications, who’s going to coordinate transitions out of the hospital? On the left of the spreadsheet, we had a list of 100 things that happen in primary care. On the top, we had every possible person you could hire for a primary care practice, starting with the doctor and ending with an exercise physiologist. And then we said, "who are the best people to serve in these roles? So the team is really designed to do all the work that needs to get done (see Table S1 for a summary of the South Huntington staffing model.)

JGIM: Many primary care clinics struggle with the team approach to care. How have you been able to promote a team approach at South Huntington?

SP: “Integrated team” is the hardest thing we’ve done, and it’s what I’m most proud of. It’s the difference between professionals playing soccer and kindergartners playing soccer. Kindergartners try really hard, but it’s a lot of parallel play—they’re just running up and down the field after the ball. In professional soccer, the players spend a lot of time just standing around—because they have clearly defined roles and plays. There is still that burst of improvisation when they’re heading for the goal, but overall, things are thought-out.

A lot of our success with team care has to do with co-location of team members from different disciplines. The team sits together: the doctors and physician assistants sit immediately next to the medical assistant they are working with, but the nurse and the social worker are in the team room also. And there’s a lot of huddling. I’m convinced that the single most important factor in creating an “integrated team” is just providing them with an environment where people naturally have multiple brief conversations throughout the course of the day.

We’ve gotten to the point where the team care routinely happens in real time while the doctor is in the room with the patient. If it’s a patient with diabetes who needs insulin titration, the doctor is paging the pharmacist for a warm handoff. If it’s a lifestyle change, the doctor is paging the nutritionist. And with each of these communications, we’re talking about the patient’s care in front of the patient and building trust. Then, when the pharmacist provides future care by phone and e-mail, the patient knows that the pharmacist and doctor are working together.

JGIM: Do you block out time for huddles, or do these conversations occur naturally?

SP: When we opened here, I mandated huddles. The team had to document them. It may have been a little over the top. But now we’re really good at it, and huddles and team conversations occur spontaneously throughout the day. All these little brief discussions create enough efficiency in how the practice runs that they save time. They also fundamentally change the relationships among the members of the team.

It is also worth noting that every other week we do what we call population huddles for 30 minutes. I think most of the world is now calling them roster reviews. Basically, we run our lists. During any given session, one team will be running a list of patients with diabetes, while another team is running a list of high-risk patients with the care manager, and a third team is sitting down with their social worker and going over the high-risk behavioral health patients. Doctors have been known to talk too much, so for our diabetes roster reviews, we have a medical assistant with a timer, and if we can’t agree on a care plan in 2 minutes, the group moves on.

JGIM: When we spoke before this interview, you talked a lot about your efforts at integrating mental health services with general primary care. What has worked well?

SP: Behavioral health is interesting. In medical home lingo, specialists are considered to be part of our medical neighborhood. What was not intuitive to me before we opened is that behavioral health is different. It’s not part of the medical neighborhood; it is part of the medical home. It always has been, and always will be, a core function of primary care.

To make this work, you need a social worker or a psychologist or a nurse with behavioral health background on site. And you need an hour or two a week of consulting psychiatrist time as well. Each of our teams has a social worker, and we also have four hours per week of a consulting psychiatrist’s time. Two of those hours are spent with her doing visits on patients where the diagnosis is unclear, and the other two hours, she works with our social workers. We do a structured assessment followed by a population huddle, where they go through 12 new patients with behavioral health problems in an hour. It’s a thing of beauty, and it’s not as crazy as it sounds. Imagine doing inpatient chart rounds with an attending and three good third-year residents who have worked together for two years, and no students, and a scribe. You can cover quite a bit of ground.

JGIM: Does your behavioral health team only focus on patients with depression and anxiety?

SP: Not just these issues—though we screen all patients at all visits for depression. We see a lot of bipolar, schizophrenia, substance abuse, and PTSD. We started with the classic IMPACT depression model (a collaborative care model in which the primary care provider co-manages depression with a care manager and a consulting psychiatrist: http://impact-uw.org/about/key.html), but it’s just not the population we serve, so we adapted it to other behavioral health issues. I just prepped for my Monday morning schedule. I’m seeing seven patients, and five have psychiatric issues: one with depression, two with bipolar disorder, one with polysubstance abuse and antisocial personality disorder, and one with opioid abuse and probably borderline personality disorder, but we are not sure. And notably, among the five patients with behavioral health disorders, there are five cancers. It’s an academic urban population.

The behavioral health team is key to the successful management of complex medical issues. When we do our diabetes population huddles, the person who leaves that huddle with the most work to do is not the pharmacist or the nutritionist; it’s usually the social worker. For a patient with a high hemoglobin A1c, it’s often a psychosocial problem. If you want to hit your pay for performance metrics for chronic disease care and keep people out of the hospital, you have to invest in behavioral health.

JGIM: Speaking of diabetes, can you talk a bit about the pharmacist in your clinic? What role does the pharmacist play?

SP: She does a bunch of things. She does difficult medication reconciliations. We have this wonderful post-hospital discharge visit, where the patient comes in, spends 20 minutes with the pharmacist, 20 minutes with the doctor, and 20 minutes with the care management nurse. Our pharmacist will also help when patients come in with three shopping bags’ worth of medications.

She is also starting to focus more on medication adherence—packaging meds, making sure they are in trays. She also supports the doctors and the physician assistants on medication questions, and lately she’s been doing a lot of training of the medical assistants so that they can do the refills and the medication reconciliation of the low-risk patients more accurately.

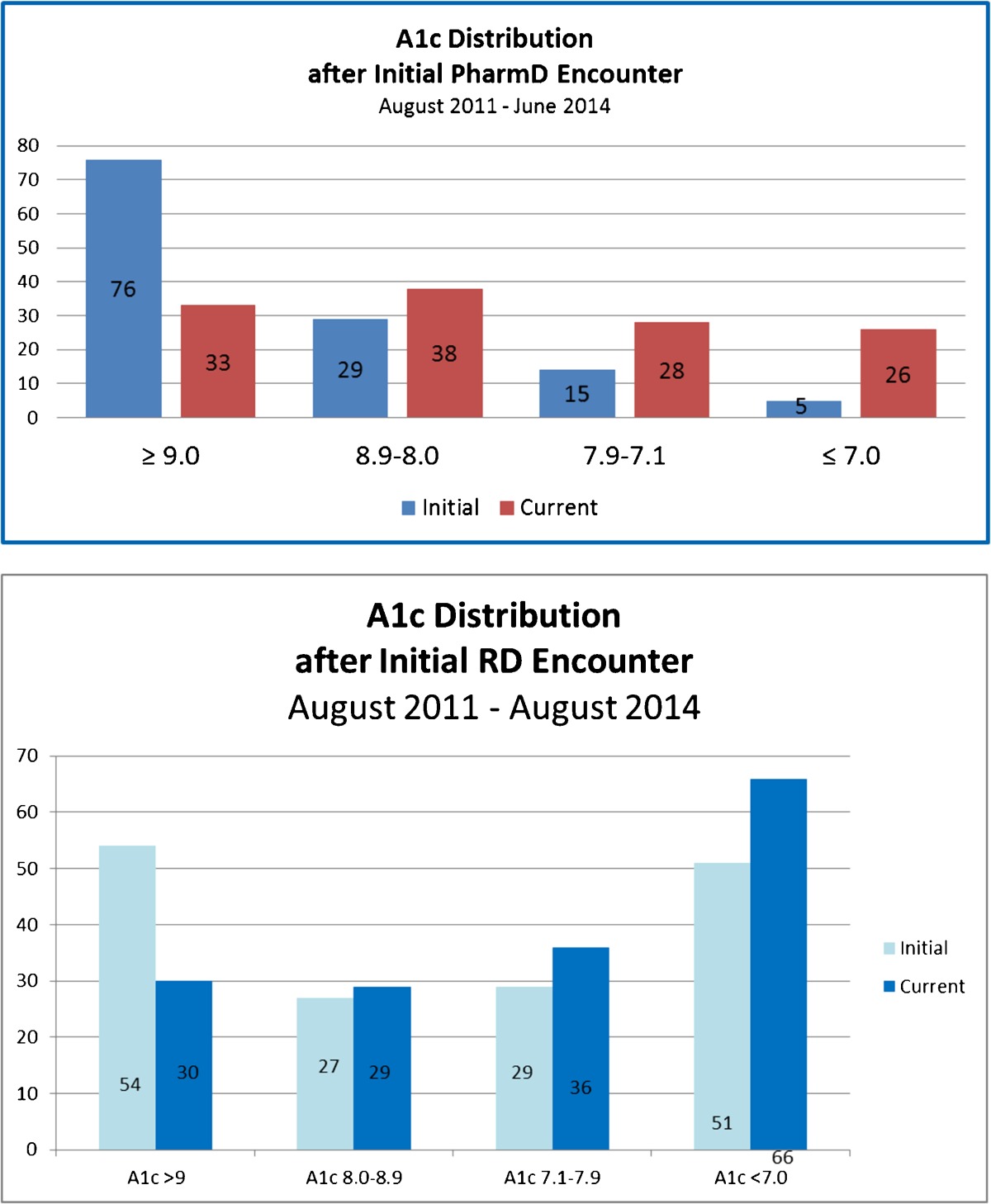

Also, along with the nutritionist, our pharmacist provides the vast majority of the type 2 diabetes care—a lot of it by e-mail. I actually got irritated when they showed me data for a group of patients whose hemoglobin A1c has been stuck at over 9 for years. They consistently fix about half those patients within six months (see Table 1). That’s way better than I have done. I don’t think I’m a slacker. I am capable of following a protocol just like they are. We talked it over, and our guess is that the reason the pharmacist and nutritionist do better than me is that when I ask the patient how they are doing, they start talking about their shoulder pain and their depression and everything else, but patients know not to talk to the pharmacist about their shoulder, so they can concentrate on the diabetes.

Table 1.

Impact of Clinical Pharmacist and Nutritionist on Diabetes Management

JGIM: Does your pharmacist initiate medications and make medication adjustments independently?

SP: Massachusetts is a collaborative drug therapy management state. Our pharmacist has a DEA number. She can write prescriptions and adjust medications, and prescriptions go out under her name as long as there’s an existing agreement with the physicians. And the protocols can be fairly broad. Our diabetes protocol is basically the American Diabetes Association guidelines plus the treat-to-target trial’s insulin titration protocol.

JGIM: You’ve mentioned a couple times that you have a nutritionist as part of the team. Tell us about how she helps you provide better care for your patients.

SP: She’s a registered dietician and a Certified Diabetes Educator. She’s another key person to help us work on this epidemic of diabetes. Interestingly, her numbers on hemoglobin A1c improvements are very similar to the pharmacist’s, which is not intuitive, given the pharmacist is titrating insulin whereas the nutritionist is focusing on lifestyle changes. Part of it is that the two of them—the nutritionist and pharmacist—work together; they sit next to each other, and they share many patients.

The other thing about having a nutritionist on the team is that it is our way of saying that medical home is not just about patients who already have complications from their chronic diseases, and hence are costing the system a lot of money now. If you are planning to be in your community in the long term, I do think it’s important to make a stand and say, we are also going to work with our patients to prevent diseases and prevent complications of those diseases, even if the return on investment is 10 or 20 years in the future.

JGIM: Interestingly, you only have one RN in your clinic. What’s her role?

SP: Because we only have one RN, we’re trying to learn how to do high-risk care coordination using a team led by an RN instead of having the RN do all the work. She leads a high-risk team, which also includes a part-time LVN, a part-time secretary, and a community health worker. Our RN is the intellectual heart of the high-risk team. She is really working at the top of her license.

JGIM: You’ve recently added a community health worker to your team to help manage complex patients. What does the community health worker do?

SP: Our community health worker has a longitudinal relationship with 16 high-risk patients, and we’re slowly increasing that number, though we don’t think it’s ever going to get above 20–25. The average patient assigned to our community health worker was in the ER every other week last year and in the hospital every two months. There was one patient who had 100 specialist visits in the six-month period before we did the intervention—close to one every weekday.

The patients that the community health worker follows have medical problems and psychiatric issues and chaotic lives. Our care manager says it’s the patients that, when you call them on the phone, there are people screaming in the background. The more people screaming in the background, the higher the risk.

Our community health worker engages these patients in a lot of ways—home visits, telephone conferences, accompanying to primary care and specialist appointments.

JGIM: How are the economics of this working out? Is the investment worth it?

SP: We’re still on a fairly steep part of the learning curve, but the early data are encouraging. For the 16 patients she’s been managing, we saw a 16 % decrease in hospitalizations in the first five months after she started. This translates into a savings of $109,000 in hospital costs, which more than offsets her salary. We can’t prove this reduction is a direct result of her efforts—there could be some regression to the mean—but it’s encouraging. We’re using a fairly inexpensive team member to intervene with the most expensive patients.

JGIM: When reviewing your staffing model (see Table S1) in preparation for this interview, I noticed a couple additional team members that we haven’t discussed yet but who seem intriguing: the population manager and the community resource specialist. Could you briefly tell us what they do?

SP: For the population manager and community resource specialist roles, we hired two people right out of college with no medical training.

When we first opened, we needed a population manger on site because our electronic health record didn’t have disease registries. Now we have system-wide registries, and our population manager is doing a more typical job: he downloads lists from the registry and makes outreach phone calls around chronic disease and prevention.

As for our community resource specialist, she offloads some of the bottom-of-the-license work for our social workers around transportation and housing, freeing them to do more of the behavioral health work. Essentially, our community resource specialist is to our social workers as medical assistants are to nurses.

JGIM: Does your team develop a shared care plan for each patient?

SP: We have finally completed shared care plans for all the uncontrolled diabetics. They are done during the population huddles. Many of the high-risk patients have care plans, though we struggle with keeping them up. We believe care plans are essential, but it’s very time-intensive. We’ve accepted the fact that low-risk patients will probably never have one.

JGIM: I want to talk a bit about mid-level providers—nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Do you think we could use mid-level providers more effectively in primary care?

SP: At South Huntington, we have three great physician assistants who are integrated into our teams. They do not have their own patients. They actually prefer it that way. When we first opened, the plan was for the physician assistants to have their own patient panels, but they asked to always be teamed with an MD. In reality, they all have many patients who think of them as their primary provider. But this is an inner city academic medical center, and we have a sick population, and our physician assistants feel the best way they can contribute is by being part of a team. And it has worked well for us.

JGIM: Perhaps this is the best model for physician assistants who are trained to work as part of teams, but what about for nurse practitioners who can practice independently? Could nurse practitioners be part of the solution for the primary care provider shortage?

SP: Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are going to be a huge part of the happy ending to the primary care crisis we are in. The interesting question is whether they will practice independently or belong to a team that includes physicians. Certainly, large numbers of independent nurse practitioner practices are possible, but my gut says this won’t be the punch line, for two reasons.

First, I’ve worked or supervised 20+ nurse practitioners, starting in 1988, and I still haven’t met one that hasn’t wanted physician backup. There is probably a small group of nurse practitioners who would really rather be completely independent, but just like most primary care physicians prefer to have built-in specialist backup—one of the reasons it’s hard to recruit in rural areas and that young doctors are drawn to big groups—I suspect most nurse practitioners like physician backup. Of course, by default, I’ve only worked with NPs who want to work with doctors, so maybe I have a skewed perspective.

Second, one of the underlying beliefs of South Huntington is that everyone does better work when they are integrated into a team. We believe that the pharmacists, RN care managers, social workers, nutritionists, physician assistants—and yes, even the physicians—are more effective when integrated into the primary care team. It has to do with collective intelligence and the fact that each profession has a different model of care, so when one model isn’t working for a patient, we can flip to another.

JGIM: So if I’m understanding you correctly, you think a team approach can help address the primary care shortage?

SP: That’s right. We don’t need every medical student—or nurse practitioner or physician assistant—in the United States to turn around and become a primary care provider. Rather, we need the best and brightest medical students to go into primary care, future doctors who have the medical knowledge and leadership skills to be part of these very sophisticated teams.

The good news is, that is what I see here at Harvard: while the number of students going into primary care is only going up by a few percentage points each year, we are now attracting the absolute best students. They recognize that many of the most interesting questions and greatest challenges in healthcare fall under primary care. It makes me very optimistic about the future of primary care in the United States.

JGIM: Conceptually, this makes sense, but have you actually been able to manage more patients because of the team approach? How many patients does each of your providers care for?

SP: I think this is actually the single most interesting thing about South Huntington. We have 3.75 FTE physicians, 1.25 FTE of whom have been here under a year. We are currently carrying 7,000+ complicated inner city academic medical center patients. Our patients are much sicker than any population I’ve managed before. And we are still taking new patients and maintaining same-day access. Based on the five doctors who have been at South Huntington over two years, it’s looking like the final panel size will be 2,400 patients per doctor. This is way higher than the 1,800 many experts have suggested as a reasonable panel size for a primary care physician. My guess is when we finally have the capability to adjust the patient load for sickness and psychosocial complexity, we will have shown that the team significantly increases the number of patients a primary care physician can effectively manage.

JGIM: A panel size of 2,400 is on the larger side, but it is still only modestly bigger than the a standard private practice panel. Do you think you could ever achieve a substantially larger panel size, say, 2,700 to 3,000?

SP: Even with a team-based approach, I don’t think a single physician can carry a panel of adults that large by themselves, while maintaining adequate access and doing a good job around prevention and chronic disease management. You run into the “I can’t work 21.7 hours a day like I used to” problem.

In 2011, the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) reported a median practice panel size of 1,906 and an average of 2,184. I’m really comfortable that our urban academic medical center panel is more complex than an average MGMA panel. Remember that to succeed in its medical home project, Group Health initially cut panels from 2,300 to 1,800.

JGIM: When we spoke before this interview, you told me that a key to your success was creating a high-functioning culture. I believe you told me that “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” How have you attempted to create a patient-centric culture at South Huntington?

SP: I’m never quite sure what patient-centric means, so I prefer to focus on patient activation and patient engagement, which is a little easier to define. I’m not sure we’re really that good in moving a patient who is not activated to activated. We certainly haven’t found the secret recipe, though we’re working on it.

But once you’re activated, I think we are very engaging. We’re very accessible: in person, by phone, by e-mail. We’re also very nice. If you look at the comments we get on our patient satisfaction surveys, the word nice appears several times a month. And “nice” has worked really well for us. Nobody feels bad that they’re bothering the doctor or the nurse when they call. I joke that “nice” may not be much of a differentiator in the Midwest, but in Boston it seems like a fairly radical concept.

Our efforts have paid off: we just got a new set of patient experience scores, and we’re 92nd percentile again.

JGIM: Do you have any tips for promoting a culture that is “nice”?

SP: If you’re hiring, you can hire for “nice.” You could say “nice” is a behavioral competency for us, and we’re going to develop a series of behavioral interviewing questions around “nice,” such as, "tell me about a difficult interaction with a patient (or customer if their previous job was at Dunkin’ Donuts)." They say that Southwest Airlines hires for a lack of pretension, which may be easier to interview for than for “nice.” Not quite the same, but it’s very close.

We’re really rigorous in hiring for soft skills for everyone—doctors to phlebotomist. It’s really about the right people.

JGIM: Have any of your hires not worked out?

SP: Of course. Not surprisingly, this occurred when we ignored the results of the behavioral interviewing questions, typically because we were desperate for someone’s hard competencies. We’ve also had some trouble with very part-time doctors who work just a couple sessions a week. We’ve made it work for the patients, but it’s hard on the team.

JGIM: Is your advice for promoting a positive culture different for a clinic starting from scratch versus an existing clinic? Many leaders will not have the luxury of being able to build their clinic from scratch as you did at South Huntington.

SP: I think with existing staff, getting to “nice” is getting past burnout. We’re lucky. We work in healthcare. Even for the secretaries, the reason they work in my office instead of a law office is because they want to help people. You can’t beat our mission. But the day-to-day pace in healthcare can be crazy, and there is a lot of pressure, and we burn people out and they’re not nice anymore.

The work we’ve done around team has helped us in this respect as well. Our staff satisfaction is high. Many of our trainees are choosing careers in primary care, and our staff are seeing primary care as a doable career.

Also, even in an existing clinic, people turn over, and you can still hire new staff for cultural fit. You can also do 360° evaluations (comprehensive feedback from an employee’s close contacts) for behaviors that fit your culture, and coach people who are struggling.

JGIM: What other things have you done to promote patient engagement?

SP: We had this idea that everybody was going to know motivational interviewing. Even our phlebotomist would be eliciting change talk while she drew blood. But it turns out that motivational interviewing is very hard to learn and do properly. Just telling patients to do things doesn’t work. We’re getting better at the spirit of motivational interviewing, learning to dance with the patients instead of wrestle with them. We get that it’s the patient’s decision what to do, and we’re here to work with that. It’s not quite as good as pure motivational interviewing, but it’s been working for us.

Another key to being engaging and activating with patients is time. In many ways, the purpose of the team approach is to generate the time needed to activate and engage patients.

JGIM: How have you promoted continuous improvement at South Huntington?

SP: I try to avoid the term “continuous improvement,” because I actually don’t believe improvement is continuous. I think the issue is continuous learning. We’ve made many mistakes along the way; we’ve failed many times. But that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is that we learned from the failure, so we’re more likely to succeed in the future.

JGIM: What about your clinic hasn’t worked well?

SP: There’s a long, long list! To begin with, information technology has not worked well. I find that electronic health records (EHRs) are very physician-centric, and I need the EHR to be team-centric. Likewise, they are visit-centric, which was fine when the unit of care was the fee-for-service visit. But when the unit of care becomes the lifetime of a patient with diabetes, then the shared care plan becomes the key documentation, which at the moment is an afterthought in our EHR.

Another struggle is that we’ve been much better at integrating nursing, social work, nutrition, and pharmacy into the team model than we have been at integrating the medical assistants. We’ve just started our third attempt at the medical assistants doing pre-visit preparation.

And there continues to be a population of patients who “fail” South Huntington. As I mentioned before, we still are consistently not fixing half of our patients whose hemoglobin A1c is over 9 (see Table 1). I can accept the fact that our track record with patients with borderline personality disorder isn’t that good. No one’s is. But for diabetes, it feels like we should be able to do better. We’ve just starting playing with shared medical appointments for diabetics and smart phone apps for patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Time will tell.

JGIM: Your clinic recently earned the designation of a patient-centered medical home from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). The NCQA’s certification criteria have taken some heat recently because research has questioned their usefulness. Do you have any recommendation on how the PCMH criteria could be revised so that they could better measure high-value primary care?

SP: I think to really figure out what’s going on in a practice, you are going to need to do more than a checklist of process measures. At a minimum, you need to survey patients and staff. There are a bunch of good staff surveys out there, and I think many of these help get at the culture of a practice, which my gut says is much more predictive of Triple Aim results than a practice’s processes.

JGIM: How did you convince Brigham and Women’s Hospital to fund this demonstration?

SP: I didn’t. Joe Frolkis, the head of primary care, did. But as best as I can tell, there are two reasons Brigham and Women’s decided to do this. First, Brigham and Women’s has a really great history of excellent primary care, and we wanted to honor that tradition by continuing to innovate.

The other answer is that Brigham had to grow primary care in order to take part in and succeed as an accountable care organization, and we can’t recruit PCP’s coming out of training if we don’t offer them a model where the job is doable.

I do give Brigham and Women’s a lot of credit. When we started planning this, Brigham was living in a fee-for-service world, and the institution was smart enough to realize that we’re not going to learn how to do this overnight, and we need to get ahead of payment reform.

JGIM: What support and other resources does Brigham provide to your clinic?

SP: They pay the salaries of our pharmacist, nutritionist, social workers, and other team members who don’t bring in any fee-for-service revenue.

I remember interviewing pharmacy candidates when we first started out and saying, you have two years during which two things need to happen. One is you need to show that you produce value. And two, the contracts that Brigham negotiates need to be negotiated differently or, no matter what, I can’t guarantee your job beyond two years. Within four months of our opening, Brigham and Women’s went into the Pioneer ACO and the Blue Cross Blue Shield alternative quality contract—which provided the business case for our team based approach.

JGIM: Is Brigham and Women’s still subsidizing your clinic?

SP: Many at Brigham believe we are still highly subsidized. I beg to differ. About half of our patients are in accountable care contracts. For patients in accountable care contracts, there’s a budget, and at the end of the year, if the total cost of care is less than the budget, then we share in the savings. But if the total cost of care is over budget, then we give some of that fee-for-service revenue back. By keeping our patients out of the emergency room and hospital, I believe we are making Brigham and Women’s lots of money. But because Brigham, like most health systems in the United States, lacks the ability to track total cost of care on an individual patient level, we may never know.

JGIM : I suspect some readers will be skeptical of the claim that you are profitable for the health system. Indeed, we have been tricked in the past. Is there a need for a formal controlled evaluation to test your claim?

SP: We tried but failed to get funding to study the practice when we were designing it. I’m not a researcher, but it’s been very hard to prove or disprove that medical home works. I have doubts this is answerable in a study, and suspect, in the end, capitalism will have to work this out.

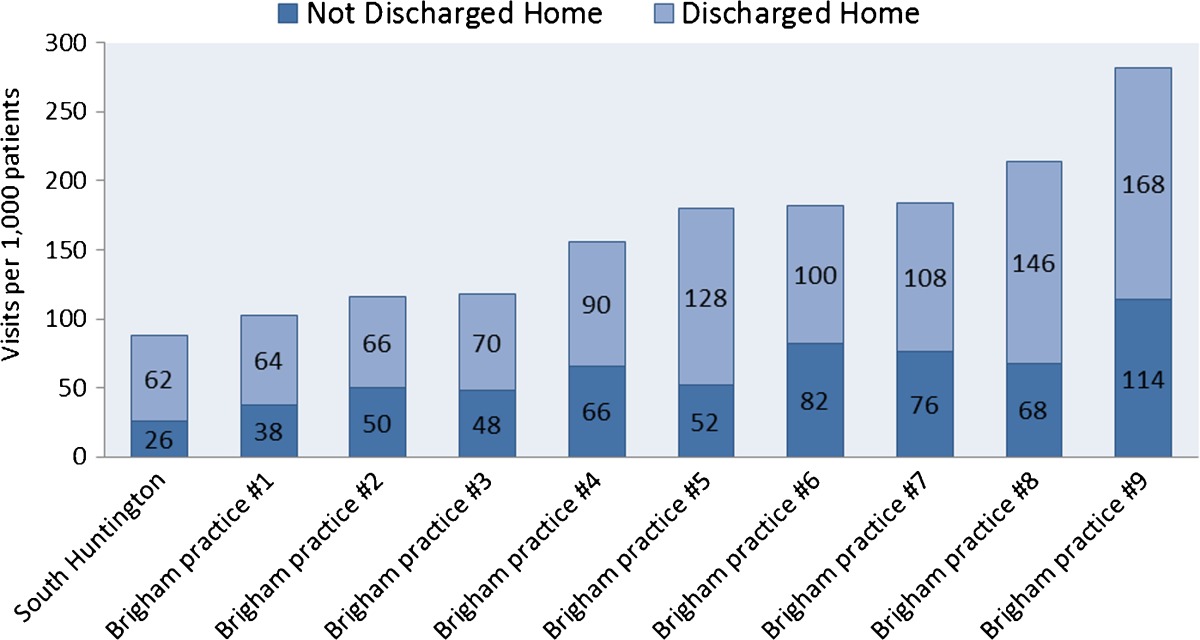

Can I prove on paper that we’re saving money? No. But I can show you some emergency room and hospital statistics suggesting that there’s an awful lot of money saved. Our emergency room utilization is lower than other Brigham and Women’s primary care clinics (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Emergency Department Utilization at South Huntington vs. Other Brigham and Women’s Primary Care Clinics

JGIM: Is Brigham and Women’s currently planning to sustain your model? What metrics do you need to hit for them to sustain it?

SP: As you have suggested, the key metric is whether or not we are profitable. Making money for the health system is not what gets me out of bed in the morning, but there’s nothing more scalable or sustainable then being profitable. This will depend a lot on how the ACO contracts get negotiated going forward. In the right reimbursement environment, I believe we can be both sustainable and scalable.

But I also want to emphasize that even in a fee-for-service environment, there are lots of arguments to be made for places like South Huntington. We are able to absorb large numbers of new patients that generate downstream revenue for the system. We prevent low-margin medical admissions, freeing up hospital beds for high-margin elective procedures. We take complex patients who are running amok through the system, and bring them under control, allowing specialists to concentrate on what they do best. And we take patients who can’t be discharged safely from the emergency room and inpatient floors because they lack a functioning primary care relationship, and see them within three days, freeing up beds and preventing readmissions.

The other question that always comes up is whether we want to scale South Huntington. Someone recently told me that South Huntington was a Ferrari, and not everyone is going to be able to have a Ferrari. But my gut says that South Huntington is a Toyota. If you take my wife’s new Toyota and compare it to the 1966 Dodge Monaco, which was my first car, that Toyota looks a lot like a Ferrari. Primary care has been so under-resourced for so long that we just don’t even know what it’s supposed to look like. I think these big teams are going to become standard.

JGIM: In Massachusetts, you are a bit ahead of the rest of the nation with respect to healthcare reform. Has coverage expansion and healthcare reform aided your practice transformation efforts?

Dr. Pollack: Pretty much every big system in eastern Massachusetts is now a pioneer ACO and part of the Blue Cross Blue Shield alternative quality contract. Let’s face it: South Huntington wouldn’t exist in a pure fee-for-service environment. No one would be stupid enough to build it. And how much we scale really depends on what these ACO contracts look like moving forward. Nothing is scalable if the incentives are not properly aligned.

JGIM: You’ve done a lot of things at South Huntington. What things were most important for developing the team-based approach?

SP: We refer to them as the Seven Habits of Highly Effective Medical Homes. We’ve covered a lot of them, but the full list is:

Co-location

Huddles

Warm handoffs

Dedicated meeting time

Hiring

Workforce development

Flattening the hierarchy

JGIM: Finally, do you have any advice for a primary care practice that wants to transform and deliver higher-value care?

SP: We all need to get out of victim mode. There are a lot of people rooting for primary care, not because we’re warm and fuzzy, but because we just make good economic sense. We need to run with that.

There’s a scene at the end of every action movie where the good guy is lying on the floor, beaten to a pulp, and the bad guy is coming in for the kill. And just beyond the good guy’s reach is some object, and he digs deep down inside and grabs that object, and uses it to creatively schmeiss the bad guy. I’ve been doing primary care for 23 years, and I don’t think it’s unfair to say that we have been hit and kicked for 23 years. But I actually think that society is offering us resources, and they’re lying just beyond our reach, and the question is whether we are going to dig deep down inside and grab those resources and do something creative that is right for us and our patients.

When I use this analogy, the question always comes up: what’s different this time? And I think the difference this time is that the world doesn’t have a choice. They need us. And they’re going to give us the opportunity. The question is, are we going to run with it?

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 447 kb)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 447 kb)