Abstract

Objective To assess the waste of research related to inadequate methods in trials included in Cochrane reviews and to examine to what extent this waste could be avoided. A secondary objective was to perform a simulation study to re-estimate this avoidable waste if all trials were adequately reported.

Design Methodological review and simulation study.

Data sources Trials included in the meta-analysis of the primary outcome of Cochrane reviews published between April 2012 and March 2013.

Data extraction and synthesis We collected the risk of bias assessment made by the review authors for each trial. For a random sample of 200 trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias, we re-assessed risk of bias and identified all related methodological problems. For each problem, possible adjustments were proposed that were then validated by an expert panel also evaluating their feasibility (easy or not) and cost. Avoidable waste was defined as trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias for which easy adjustments with no or minor cost could change all domains to low risk. In the simulation study, after extrapolating our re-assessment of risk of bias to all trials, we considered each domain rated as unclear risk of bias as missing data and used multiple imputations to determine whether they were at high or low risk.

Results Of 1286 trials from 205 meta-analyses, 556 (43%) had at least one domain at high risk of bias. Among the sample of 200 of these trials, 142 were confirmed as high risk; in these, we identified 25 types of methodological problem. Adjustments were possible in 136 trials (96%). Easy adjustments with no or minor cost could be applied in 71 trials (50%), resulting in 17 trials (12%) changing to low risk for all domains. So the avoidable waste represented 12% (95% CI 7% to 18%) of trials with at least one domain at high risk. After correcting for incomplete reporting, avoidable waste due to inadequate methods was estimated at 42% (95% CI 36% to 49%).

Conclusions An important burden of wasted research is related to inadequate methods. This waste could be partly avoided by simple and inexpensive adjustments.

Introduction

In 2009, Chalmers and Glasziou raised an important concern about the extent of research that is wasted, estimating the loss to be as much as 85% of research investment.1 This waste concerns all types of research and occurs at all stages of the production of research evidence, from the choice of questions that are not relevant to patients and their physicians to under-reporting of trial methods and results.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Such a situation is ethically, scientifically, and economically indefensible.9 10 It necessitates rethinking the whole system of clinical research to increase the value of research and reduce waste, as recently outlined in a series in the Lancet.2 3 4 5 6 7

A large part of waste is related to inadequate methods.1 6 Flaws in design, conduct, and analysis can bias results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and the systematic reviews that include them, thus leading to potentially erroneous conclusions6 with serious consequences for patients. Empirical evidence found exaggerated estimates of intervention effect in trials with inadequate sequence generation or allocation concealment,11 12 13 lack of blinding,11 14 or exclusion of patients from analyses.15 16 On the basis of this empirical evidence, the Cochrane Collaboration developed a tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs, the Risk of Bias (RoB) tool, and recommended excluding trials at high risk of bias from the meta-analysis or presenting the meta-analysis stratified by risk of bias.17 Risk of bias is assessed from the final RCT report, when it is no longer possible to change anything. However, a part of the waste related to inadequate methods could have been avoided by modifying the design, conduct, and analysis of these trials during the planning stage of the trial.

We aimed to assess the waste of research due to inadequate methods in clinical trials and to examine to what extent that waste could be reduced. A secondary objective was to perform a simulation study to re-estimate the avoidable waste if all trials were adequately reported.

Methods

We identified all trials included in recent Cochrane reviews. For a random sample of the trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias according to the review authors, we reassessed risk of bias. Then, for trials confirmed at high risk, we identified all methodological problems and proposed adjustments. An expert panel validated these adjustments and assessed their feasibility and cost. Avoidable waste was defined as trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias for which easy adjustments with no or minor cost could change all domains to low risk of bias. Finally, we performed a simulation study to re-estimate the avoidable waste related to inadequate methods if all trials were adequately reported.

Selection of trials included in recent Cochrane reviews

Identification and selection of Cochrane reviews

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews between 1 April 2012 and 31 March 2013 and included new systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials, with at least one meta-analysis, examining the effects of healthcare interventions. We selected reviews that had used the RoB tool for assessing risk of bias in included trials, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook.17 Updates of systematic reviews were excluded because their risk of bias was frequently not entirely reassessed. We also excluded reviews of diagnostic test accuracy, prognosis, or economic evaluations.

Meta-analysis selection

For each included review, we selected the meta-analysis for the primary outcome defined by the review authors. In cases of several primary outcomes, we selected the meta-analysis with the largest number of trials. We assessed whether the outcome was objective or subjective according to the classification by Savovic et al.12 Objective outcomes were defined as all cause mortality, other objectively assessed outcomes (for example, pregnancy, live births, and laboratory outcomes), or objectively measured but potentially influenced by clinicians’ or patients’ judgment (for example, hospitalisations, total dropouts, operative delivery, additional treatments administered). Clinician assessed outcomes and patient reported outcomes were considered subjective outcomes.

Trial selection

All trials included in the meta-analyses defined above were selected.

Review authors’ assessment of risk of bias

For each trial, one of us (YY) collected, from the Cochrane report, the review authors’ assessment of risk of bias for the following key domains of the RoB tool: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data. We did not consider the domains “selective outcome reporting” and “other risk of bias,” because these two domains are difficult to assess,18 19 particularly for selective outcome reporting when the protocol is not available.

Identification of a random sample of trials at high risk of bias

Among all trials with at least one domain at high risk, we randomly selected a sample of 200 trials and retrieved the full text for each of these trials. When the full text was not available (n=6) or was in a language other than English, French, or Spanish (n=19), we retrieved the English abstract and the study summary available in the “Characteristics of included studies” section of every Cochrane review.

Reassessment of risk of bias for the random sample of trials considered at high risk

For each trial of the random sample of 200 trials the review authors considered at high risk of bias, two trained reviewers (CR, YY) independently re-evaluated the risk of bias for each key domain, using the RoB tool, from the individual published trial reports. Definitions used for each domain to reassess the risk of bias were based on the Cochrane Handbook17 and are detailed in appendix 1. Blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data domains were assessed at the outcome level and corresponded to the primary outcome assessed in the meta-analysis. We compared our re-assessment to the initial assessment by the review authors including their support for judgment to determine any discrepancies and if review authors obtained additional information from the trial authors that could explain the discrepancies. All discrepancies were discussed and a final consensus on risk of bias was achieved with the help of a third reviewer (AD) if needed. The 95% confidence intervals of the proportion of agreement between the review authors’ assessment and our re-assessment were estimated using logistic regression models fitted with the generalised estimating equation (GEE) to account for within trial correlation.20

Identification of all methodological problems responsible for the high risk of bias

For each trial confirmed at high risk of bias after reassessment, two authors (AD, YY) independently identified, from the individual reports, the methodological problem(s) for each domain with high risk. They organised all methodological problems by domain and by type. For each type of methodological problem, they suggested possible adjustments from their experience and from relevant literature.11 15 21 22

Feasibility and costs of methodological adjustments

We used an expert consensus approach to evaluate the proposed adjustments. During a meeting, methodological problems and possible adjustments were discussed by an expert panel including four internationally recognised methodologists (DA, IB, PR, SH) who have been involved in numerous clinical trials of various fields. Two are experts in the evaluation of non-pharmacological treatments. One of us (YY) presented, domain by domain, each type of methodological problem and proposed adjustments, with detailed examples from the trials in the sample. The expert panel was not informed of the proportion of methodological problems in included trials. For each problem, the expert panel was asked to validate the proposed adjustments by answering the following questions: “Do you agree with the proposed adjustment?” and “Do you have another suggestion?” Then, experts were asked to estimate the feasibility and cost of the adjustments in light of their experience: “According to you and based on your experience, would you consider that the proposed adjustment is easy to implement, moderately easy, difficult, or impossible in most cases.” “According to you and based on your experience, what would be the approximate cost of this adjustment: no cost defined as ≤ 1% of the total amount of the trial; minor cost, defined as ≤5%; moderate cost, defined as 5% to 15%; or major cost, if 15% or more.” These percentages were indicative. Two authors (AD, YY) facilitated the meeting to ensure that all experts first gave their opinion and then discussed together, to avoid the opinion of one leading person influencing the others.

The final feasibility and cost evaluation of every proposed adjustment was based on group consensus.

As a quality assurance measure, we also discussed feasibility and cost of proposed adjustments for blinding and practical issues with experts in the field. For pharmacological treatments, we contacted the senior pharmacist in charge of the pharmaceutical services for all pharmacological clinical trials sponsored by Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, a network of all teaching hospitals in Paris and its suburbs. For non-pharmacological treatments, we contacted two surgeons: one orthopaedic surgeon and one obstetrician involved in clinical trials. These three experts were blinded to the experts’ consensus.

Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods

For each trial in our random sample confirmed at high risk of bias, we assessed whether the identified methodological problems could be corrected by easy adjustments, at no or minor additional cost as determined by the expert panel. Avoidable waste was defined as trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias for which easy adjustments with no or minor cost could change all domains to low risk of bias. As a sensitivity analysis, we also assessed the avoidable waste after applying all possible adjustments (that is, adjustments considered by the expert panel as easy, moderately easy, or difficult), whatever their cost.

Correction of incomplete reporting in the whole sample of trials and re-estimation of avoidable waste

We performed a simulation study to re-estimate avoidable waste due to inadequate methods if all trials were adequately reported. Firstly, we extrapolated our reassessment of risk of bias to the trials for which risk of bias was not reassessed (whole sample minus the 200 trials already reassessed) using the observed agreement by domain between the review authors’ initial assessment and our reassessment of the 200 trials for which we had both evaluations. Then, we considered each domain rated as unclear as missing data and used multiple imputations to attribute a risk-of-bias assessment of high or low to these domains. Finally, we re-estimated the avoidable waste in the whole sample of trials after applying easy adjustments with no or minor additional cost to each domain imputed at high risk of bias. Imputation and statistical analysis are detailed in appendix 2. Statistical analyses involved use of R v3.0.2 (2013-09-25) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Selection and characteristics of trials

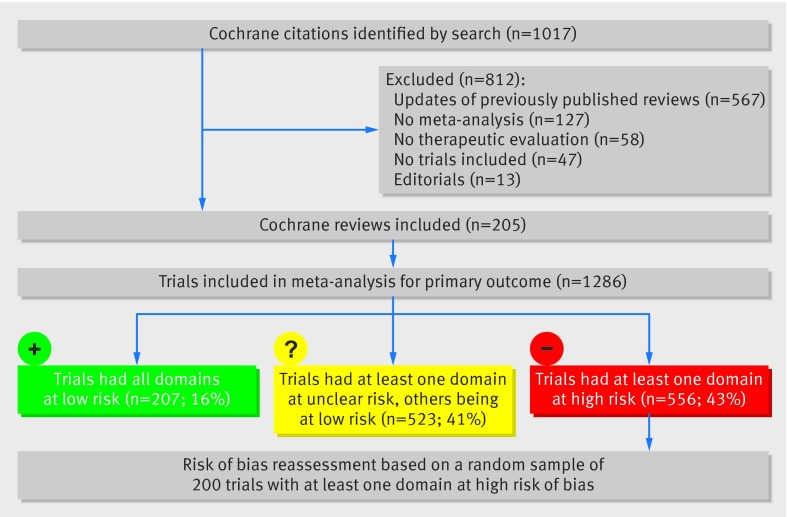

Figure 1 shows the study profile. Briefly, of the 1017 Cochrane citations retrieved by searching, we selected 205 Cochrane reviews including 1286 trials in the meta-analysis of the primary outcome. General characteristics of the 1286 trials are given in table 1. The most common medical fields were psychiatry (18%), obstetrics and gynaecology (10%), and oncology (8%). Trials were published between 1957 and 2012 (median year of publication 2004). In 1003 trials (78%), the outcome of interest included a non-fatal event and in 302 (23%), mortality. The outcome was considered objective in 500 trials (39%).

Fig 1 Flow diagram of the selection of trials

Table 1.

General characteristics of the trials included in the meta-analysis of the primary outcome of recent Cochrane reviews

| No (%) n=1286 | |

|---|---|

| Medical fields: | |

| Psychiatry/psychology | 232 (18) |

| Obstetrics/gynaecology | 124 (10) |

| Oncology | 100 (8) |

| Infectious diseases | 91 (7) |

| Gastroenterology | 73 (6) |

| Paediatrics | 71 (6) |

| Others | 595 (46) |

| Type of intervention: | |

| Drug | 826 (64) |

| Counselling/lifestyle | 258 (20) |

| Surgical/procedure | 165 (13) |

| Equipment | 37 (3) |

| Year of publication, median (min–max) | 2004 (1957-2012) |

| Design of included trials: | |

| Parallel design | 1229 (96) |

| Crossover | 25 (2) |

| Cluster | 21 (2) |

| Factorial | 7 (0.5) |

| Non-inferiority | 4 (0.3) |

| Primary outcome: | |

| Non-fatal events | 1003 (78) |

| Physician driven data | 649 (50) |

| Mortality | 302 (23) |

| Patient reported outcomes | 240 (19) |

| Biological test | 186 (14) |

| Radiology exam | 58 (5) |

| Subjective outcome | 786 (61) |

| Objective outcome | 500 (39) |

Risk of bias of trials

Review authors’ assessment of risk of bias

Overall, 207 trials (16%) had all domains at low risk of bias, 556 (43%) at least one domain at high risk of bias, and another 523 (41%) at least one domain at unclear risk. For sequence generation, 36 trials (3%) were considered at high risk of bias and 612 (48%) at unclear risk. For allocation concealment, 64 (5%) were considered at high risk of bias and 661 (51%) at unclear risk. For blinding of patients and personnel, 379 (29%) were considered at high risk of bias and 310 (24%) at unclear risk. For blinding of outcome assessment, 249 (19%) were considered at high risk of bias and 356 (28%) at unclear risk. For incomplete outcome data, 220 (17%) were at high risk of bias and 243 (19%) at unclear risk (table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias for each key domain of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool . Values are number (percentage) of trials

| Level of bias in key domains of the Risk of Bias tool | All trials (n=1286) | Trials with ≥1 domain at high risk of bias according to the review authors (n=556) | Trials confirmed to be at high risk of bias from a random sample of 200 trials with ≥1 domain at high risk according to the review authors (n=142) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation (selection bias): | |||

| Low | 634 (49) | 235 (42) | 66 (46) |

| Unclear | 612 (48) | 285 (51) | 62 (44) |

| High | 36 (3) | 36 (6) | 14 (10) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias): | |||

| Low | 555 (43) | 177 (32) | 49 (35) |

| Unclear | 661 (51) | 312 (56) | 76 (54) |

| High | 64 (5) | 64 (12) | 17 (12) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias): | |||

| Low | 553 (24) | 95 (17) | 50 (35) |

| Unclear | 310 (24) | 80 (14) | 10 (7) |

| High | 379 (29) | 373 (67) | 82 (58) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): | |||

| Low | 631 (49) | 169 (30) | 64 (45) |

| Unclear | 356 (28) | 130 (23) | 23 (16) |

| High | 249 (19) | 249 (45) | 55 (39) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): | |||

| Low | 782 (61) | 240 (43) | 57 (40) |

| Unclear | 243 (19) | 82 (15) | 17 (12) |

| High | 220 (17) | 220 (40) | 68 (48) |

Risk of bias reassessment for a random sample of 200 trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias

For the random sample of 200 trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias according to the review authors, we confirmed high risk of bias for 142 trials (71%). Appendix 3 presents the agreement between review authors’ assessment and our re-evaluation for each domain. Disagreements with review authors’ assessments mainly concerned blinding of outcome assessment. Of the 82 trials that the review authors considered at high risk for blinding of outcome assessment, 30 concerned an objective outcome so the risk of bias was judged as low. Risk of bias assessment for the 142 trials confirmed at high risk is shown in table 2.

Methodological problems identified in the trials confirmed at high risk of bias and possible adjustments

We identified 25 different types of methodological problems in the 142 trials with at least one domain confirmed at high risk. The most frequently encountered were exclusion of patients from analysis in 50 trials (35%), lack of blinding with a patient reported outcome in 27 (19%), lack of blinding when comparing a non-pharmacological intervention versus nothing in 23 (16%), and an inadequate method to deal with missing data in 22 (15%) (table 3). Table 3 describes, for each type of methodological problem, the proposed adjustments, their feasibility, and costs according to the experts. Appendix 4 gives some examples of methodological problems that could not be corrected.

Table 3.

Methodological problems identified in trials confirmed to be at high risk of bias after reassessment and proposed adjustments with their feasibility and cost determined by the expert panel

| Domain | Type of problem identified in the original articles | No (%) n=142 | Proposition of methodological adjustments | Feasibility of adjustment (easy, medium, difficult, or impossible) | Cost (no cost, minor, moderate, or major) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation | Inappropriate sequence generation | 15 (11) | Computer sequence generation | Easy | No cost |

| Allocation concealment | No allocation concealment or according to patients characteristics | 14 (10) | Central randomisation, internet based | Easy | Minor |

| Unsealed envelopes | 1 (1) | Sealed opaque envelopes | Easy | No cost | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel: | |||||

| Pharmacological interventions | No blinding, active treatment v active treatment, both pharmacological treatments have the same physical characteristics (eg, powder, infusion) and the same route. Procedures and monitoring are similar. | 2 (1) | Preparation by the pharmacist of indistinguishable containers with experimental treatment and control ± reconstitution by an independent nurse | Easy | Minor |

| No blinding, pharmacological treatments v nothing. Pharmacological treatment with no noticeable side effects, shape, colour or taste. | 7 (5) | Preparation by the pharmacist of indistinguishable containers with experimental treatment and placebo | Easy | Moderate | |

| No blinding, pharmacological treatments with different route of administration and appearance. | 13 (9) | Double dummy | Medium | Major | |

| No blinding due to different surveillance and adaptation (eg, adaptation of dose of treatment) | 3 (2) | Sham adapted surveillance and dosage in the control group | Difficult | Major | |

| No blinding. Treatments with noticeable elements (colour, shape, etc) | 2 (1) | Blinding of the noticeable elements of the treatments | Difficult | Major | |

| Treatments with very frequent and clinically specific side effects | 4 (3) | Impossible in most cases | Impossible in most cases | ||

| Non-pharmacological interventions | No blinding, surgical interventions with similar scars, perioperative and postoperative care | 10 (7) | Blinding of patients, no more contact with the unblinded care providers during the trial follow-up | Medium | Minor |

| No blinding, surgical interventions with different scars | 2 (1) | Blinding of patients with masking of scars, no more contact with the unblinded care providers during the trial follow-up | Medium | Minor | |

| No blinding, non-pharmacological intervention v nothing | 23 (16) | Use of an attention placebo control group, with patients blinded to the hypothesis | Medium | Major | |

| No blinding, non-pharmacological intervention v minimal intervention | 12 (8) | Blinding of patients by a simulated interventions | Difficult | Major | |

| No blinding, non-pharmacological intervention (surgery) v pharmacological intervention | 2 (1) | Blinding of patients and personnel by a simulated intervention and a placebo | Difficult | Major | |

| No blinding, non-pharmacological intervention (surgery) v another non-pharmacological intervention | 7 (5) | Double sham strategies | Difficult | Major | |

| Blinding of outcome assessor | Outcome is a clinical measure performed by an unblinded physician | 10 (7) | Blinded measurement by an independent clinician | Medium | Moderate |

| Outcome is a non-fatal event evaluated by the investigators following patients, no blinding | 11 (8) | Blinded central evaluation of events by independent clinicians (adjudication committee) | Medium | Major | |

| Outcome is a patient reported outcome, treatment blinding is possible | 27 (19) | Participants and personnel blinding implemented | Depends on blinding | ||

| Outcome is a patient reported outcome, no blinding possible | 0 | Outcome is a patient reported outcome, no blinding possible | Impossible in most cases | ||

| Outcome is evaluated by imagery without blinding | 4 (3) | Blinded central evaluation of imagery | Medium | Major | |

| Outcome is a specific biological test requiring interpretation | 2 (1) | Blinded central evaluation by an independent clinician | Medium | Major | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Exclusion of patients from the analysis | 50 (35) | Intention to treat analysis | Easy | No |

| Intention to treat analysis but inadequate missing data imputation | 22 (15) | Intention to treat analysis with a multiple imputation method | Easy | Minor | |

| Important lost to follow-up rates ≥30% | 16 (11) | Better patient monitoring | Difficult | Major | |

| Major imbalance in the number of withdrawals | 2 (1) | Impossible in most cases | Impossible in most cases |

Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods

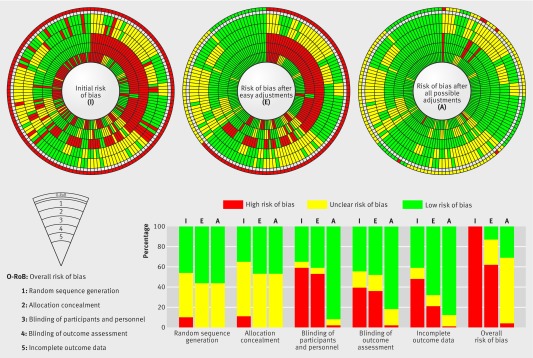

From the experts’ evaluation, at least one adjustment could be made in 136 trials (96%). Applying easy methodological adjustments with no or minor additional cost to trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias could have reduced the number of domains at high risk in 71 trials (50%). These adjustments could correct all trials at high risk of bias for sequence generation (n=14) and allocation concealment (n=17). Of the 82 trials at high risk for blinding of patients and personnel, seven (8%) could be corrected. Of the 55 trials at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment, one (2%) could be corrected. Of the 68 trials at high risk for incomplete outcome data, 37 (54%) could be corrected.

These adjustments resulted in all domains becoming at low risk for 17 trials (12%). So the avoidable waste related to inadequate methods represented 12% (95% CI 7% to 18%) of trials. In another 34 trials (24%; 95% CI 17% to 31%), there was no domain at high risk but at least one domain was at unclear risk. With all adjustments considered possible by the experts, regardless of difficulty or cost, avoidable waste of research represented 31% (n=44) (95 CI 23% to 39%) of trials (figure 2).

Fig 2 Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods in trials with at least one domain confirmed at high risk of bias (n=142). This figure summarises the evolution in risk of bias assessment per domain for each trial, initially (I), after easy (E) methodological adjustments, or after all (A) possible methodological adjustments. Each spoke represents one of the 142 trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias. The bricks are a visual representation of the risk of bias assessment per domain, red indicating high risk of bias; yellow, unclear risk; and green, low risk for each trial. Every concentric circle represents one of the key domains of the risk of bias tool with “sequence generation” being the furthest circle from the centre, and “incomplete outcome data”, the central circle. The most external circle represents a quick overview of the risk of bias for each trial (red if at least one domain is at high risk, yellow if at least one domain is at unclear risk, and green if all domains are at low risk). The histogram is a representation of the risk of bias, per domain, across the 142 high risk trials, initially (I), after easy (E) methodological adjustments, or after all (A) possible methodological adjustments.

Correction of incomplete reporting in the whole sample of trials and re-estimation of avoidable waste

After imputation of domains at unclear risk of bias in the 1286 trials, 43% of trials (95% CI 39% to 47%) would have all their domains at low risk and 57% (95% CI 53% to 61%) would have at least one domain at high risk. Applying easy adjustments at no or minor cost would change risk of bias to low risk for all domains in 42% of the trials with at least one domain at high risk (95% CI 36 to 49%), so the avoidable waste related to inadequate methods would represent 42% (95% CI 36 to 49%). This results in a 24% decrease of the percentage of trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias from 57% (95% CI 53% to 61%) to 33% (95% CI 29% to 37%).

Discussion

Here we assessed the avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods in a large sample of clinical trials included in recent systematic reviews. Overall, 43% of these trials had at least one domain at high risk of bias and another 41% had at least one domain at unclear risk because of incomplete reporting. Applying easy methodological adjustments with no or minor additional cost could have limited the number of domains at high risk of bias in 50% of trials with at least one domain at high risk, with all domains changing to low risk in 12%. After correcting incomplete reporting, this avoidable waste could represent 42% of all trials with at least one domain at high risk (95% CI 36% to 49%).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

There is a pressing need to improve the quality of research to minimise biases.6 Our study involved an original approach moving from an a posteriori assessment of risk of bias to limiting the methodological problems responsible for high risk of bias during the planning stage of the trials. Our approach takes into account that, for some trials, it is not possible to do better, for example, in assessing non-pharmacological treatments for which blinding is not possible. In fact, our definition of avoidable waste is based on problems that could have been easily avoided with no additional cost at the planning stage of the trial. We used an expert panel consensus to validate proposed methodological adjustments and to determine their feasibility and cost. The experts involved are internationally recognised in the field of RCT methods and assessment of risk of bias. To ensure that they were not influenced during their assessment, they were not informed of the proportion of methodological problems in the sample.

Our study focused on waste related to inadequate methods and did not consider other important sources of waste such as lack of relevance of the study question. Our sample of trials is from Cochrane reviews, which may have excluded trials not meeting certain methodological criteria. To identify methodological problems, we reassessed risk of bias for a random sample of 200 trials at high risk of bias, which may lead to a possible underestimation of the number of methodological problems. In fact, some of the trials the review authors considered at low or unclear risk could be at high risk. We disagreed with the review authors’ assessment for 29% of trials. Disagreements mainly concerned the domains related to blinding, which is consistent with previous studies showing low reproducibility for that domain.23 24 Although we attempted to provide a classification of all methodological problems in as much detail as possible, feasibility and costs of adjustments may vary across trials for the same methodological problem. We accounted for the correlation between the different adjustments but we did not fully take into account that for blinding; a single adjustment could simultaneously correct two domains (blinding of patients/personnel and blinding of outcome assessment). Finally, our analysis is based on the assumption that conduct and reporting are unrelated.

Possible explanations and implications for researchers

Our results highlight that with simple adjustments, the number of domains at high risk could have been reduced for half of trials with at least one domain at high risk of bias. These results may be explained by the lack of involvement of methodologists and statisticians at the planning stage of the trials and by authors’ insufficient knowledge of research methods.6 25 In many countries, specific training in research methodology is unavailable, other than a short introduction to biostatistics early in medical school.6 Teaching research methods to all medical students is crucial. Not all students will be involved in research, but all will have to critically appraise research articles and make medical decisions using the results. In addition, communication between methodologists and health researchers should be enhanced by the involvement of methodologists from the planning stage of the study onwards.6 Access to methodologists is not always feasible for all physicians, so developing online tools allowing for diagnosis of methodological problems and proposing simple adjustments such as those we proposed would be helpful.

Our results showed that methodological adjustments led to limited improvement in terms of all domains because of the issue of incomplete reporting. Half of the trials in our study were affected by reporting issues, which confirms the poor reporting found in numerous publications.26 27 28 Although poor reporting does not mean poor methods,29 30 it represents another source of waste5 because we cannot adequately assess the validity of methods used and consequently the results and conclusions of the trial. Waste related to incomplete reporting could be completely avoided if all relevant elements were adequately noted in trial reports. In this study, when we corrected both reporting and inadequate methods, the proportion of trials with at least one domain at high or unclear risk decreased from 84% (41% with at least one domain at unclear risk and 43% with at least one domain at high risk) to 33% in the imputed dataset. This finding outlines the need to further improve reporting. Many efforts have been made to improve the reporting of research with the development and large diffusion of reporting guidelines31 32 adapted to the type of trial and interventions and with the creation of the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) network33 to promote transparency in research. However, according to recent publications,34 35 36 adherence to these recommendations is still suboptimal. Many journals adhere to the CONSORT statement and other reporting guidelines, but actual implementation varies greatly from one journal to another.35 37 38 More active implementation of the CONSORT statement and other reporting guidelines is needed to substantially improve the reporting of health related research.

Conclusions

Our study shows that an important burden of waste is related to inadequate methods in clinical trials. This waste could be avoided in part by simple and inexpensive methodological adjustments during the planning stage. Greater involvement of methodologists at the planning stage could help reduce this avoidable waste.

What is already known on this topic

In 2009, Chalmers and Glasziou made the claim that up to 85% of research could be considered as wasted

A large part of that waste is related to inadequate methods

Flaws in design, conduct, and analysis can bias results of randomised controlled trials and the systematic reviews that include them and lead to potentially erroneous conclusions with serious consequences for patients

What this study adds

We found that part of the waste related to inadequate methods could have been avoided by simple and inexpensive methodological adjustments

Such adjustments could decrease the risk of bias in half of trials at high risk of bias and could transform all domains at high risk to low risk in 12% trials (95% CI 7% to 18%)

In a simulation study correcting for incomplete reporting, this avoidable waste represented 42% (95% CI 36% to 49%).

We thank Carolina Riveros for help with the risk of bias assessment, Sally Hopewell for participating to the expert panel, and Ali Al Khafaji for help with data extraction. We also thank Annick Tibi, pharmacist in charge of the pharmaceutical services for all clinical trials sponsored by Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris; Patrick Boyer, orthopaedic surgeon at Bichat Hospital, Paris; and Patrick Rozenberg, obstetrician at Poissy hospital for discussing feasibility and cost of methodological adjustments for blinding in pharmacological and non-pharmacological trials, respectively.

Contributors: YY was involved in the study conception, selection of trials, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript; AD was involved in the study conception, selection of trials, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript; RP was involved in the data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript; IB was involved in the study conception, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript; DA was involved in the interpretation of results and drafting the manuscript; PR was involved in the study conception, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. AD is the guarantor.

Funding: This study did not receive any specific funding. The team Centre d’Epidemiologie Clinique is supported by an academic grant from the programme “Equipe espoir de la Recherche”, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), Paris, France (No DEQ20101221475). AD is funded by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM). DGA is supported by Cancer Research UK (C5529). These funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Transparency: AD affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Data sharing: Data available upon request for academic researchers.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h809

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Definitions used for assessing the risk of bias in individual randomised controlled trials

Appendix 2: Details of the simulation analysis to correct incomplete reporting in the whole sample of trials and re-estimate the avoidable waste

Appendix 3: Agreement by domain between risk of bias assessment made by review authors and our re-assessment

Appendix 4: Examples of methodological problems that could not be corrected

References

- 1.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Shahi Salman R, Beller E, Kagan J, Hemminki E, Phillips RS, Savulescu J, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet 2014;383:176-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014;383:156-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014;383:257-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet 2014;383:166-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, Dirnagl U, Chalmers I, Ioannidis JP, et al. Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014;383:101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott IA, Glasziou PP. Improving the effectiveness of clinical medicine: the need for better science. Med J Aust 2012;196:304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A. An unfinished trip through uncertainties. BMJ 2004;328:531. [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK health, science, and overseas aid: not what they seem. Lancet 2010;376:1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuesch E, Reichenbach S, Trelle S, Rutjes AW, Liewald K, Sterchi R, et al. The importance of allocation concealment and patient blinding in osteoarthritis trials: a meta-epidemiologic study. Arthritis and rheumatism 2009;61:1633-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savovic J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Jüni P, Pildal J, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:429-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Jüni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Psaty BM, Prentice RL. Minimizing bias in randomized trials: the importance of blinding. JAMA 2010;304:793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Rutjes AWS, Bürgi E, Scherer M, et al. The effects of excluding patients from the analysis in randomised controlled trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2009;339:b3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tierney JF, Stewart LA. Investigating patient exclusion bias in meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartling L, Bond K, Vandermeer B, Seida J, Dryden DM, Rowe BH, et al. Applying the risk of bias tool in a systematic review of combination long-acting beta-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids for persistent asthma. PLoS One 2011;6:e17242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartling L, Hamm MP, Milne A, Vandermeer B, Santaguida PL, Ansari M, et al. Testing the risk of bias tool showed low reliability between individual reviewers and across consensus assessments of reviewer pairs. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:973-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boutron I, Estellat C, Guittet L, Dechartres A, Sackett DL, Hróbjartsson A, et al. Methods of blinding in reports of randomized controlled trials assessing pharmacologic treatments: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2006;3:e425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boutron I, Tubach F, Giraudeau B, Ravaud P. Blinding was judged more difficult to achieve and maintain in nonpharmacologic than pharmacologic trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:543-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartling L, Ospina M, Liang Y, Dryden DM, Hooton N, Seida JK, et al. Risk of bias versus quality assessment of randomised controlled trials: cross sectional study. BMJ 2009;339:b4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vale CL, Tierney JF, Burdett S. Can trial quality be reliably assessed from published reports of cancer trials: evaluation of risk of bias assessments in systematic reviews. BMJ 2013;346:f1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman DG, Goodman SN, Schroter S. How statistical expertise is used in medical research. JAMA 2002;287:2817-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Weeks L, Peters J, Kober T, et al. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:MR000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann TC, Erueti C, Glasziou PP. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. BMJ 2013;347:f3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, Chan A-W, Altman DG. The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010;340:c723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mhaskar R, Djulbegovic B, Magazin A, Soares HP, Kumar A. Published methodological quality of randomized controlled trials does not reflect the actual quality assessed in protocols. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:602-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares HP, Daniels S, Kumar A, Clarke M, Scott C, Swannet S, et al. Bad reporting does not mean bad methods for randomised trials: observational study of randomised controlled trials performed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. BMJ 2004;328:22-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Weeks L, Ocampo M, Seely D, Sampson M, Altman DG, et al. Describing reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:718-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simera I. EQUATOR Network collates resources for good research. BMJ 2008;337:a2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larson EL, Cortazal M. Publication guidelines need widespread adoption. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:239-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa D, Borg Debono V, Dillenburg R, Zhang S, et al. A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare 2013;6:169-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev 2012;1:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hopewell S, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF. Endorsement of the CONSORT Statement by high impact factor medical journals: a survey of journal editors and journal ’Instructions to Authors’. Trials 2008;9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, Boutron I. Effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Definitions used for assessing the risk of bias in individual randomised controlled trials

Appendix 2: Details of the simulation analysis to correct incomplete reporting in the whole sample of trials and re-estimate the avoidable waste

Appendix 3: Agreement by domain between risk of bias assessment made by review authors and our re-assessment

Appendix 4: Examples of methodological problems that could not be corrected