Abstract

α,α-Difluoroketones possess unique physicochemical properties that are useful for developing therapeutics and probes for chemical biology. In order to access the α-allyl-α,α-difluoroketone substructure, complementary Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation reactions were developed to provide linear and branched α-allyl-α,α-difluoroketones. For these orthogonal processes, the regioselectivity was uniquely controlled by fluorination of the substrate and the structure of ligand.

Keywords: allylation, regioselectivity, synthetic methods, P ligands, palladium

Decarboxylative coupling is a powerful method for the construction of C—C bonds that generates reactive organometallic intermediates under mild conditions and releases CO2 as the only byproduct.[1] Moreover, this strategy enables the formation of reactive intermediates and regioselective coupling to provide products that might be difficult to access otherwise.[2] While Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation reactions of soft C-based (e.g. malonates, β -diketones, β -ketoestsers) and heteroatom-based nucleophiles can provide both branched[3] and linear[4] products, Pd-catalyzed allylation reactions of hard enolate-nucleophiles with monosubstituted allylic substrates almost exclusively provide linear products.[1b,5] In a rare example, a Pd-catalyzed allylation of a ketone enolate employed stoichiometric Li additives to provide this uncommon branched product.[6, 7] However, the ability of a ligand to control the regioselectivity for Pd-catalyzed allylation reactions of ketone enolates has not been demonstrated. Herein, we report complementary Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation reactions of hard α,α-difluoroketones that generate both linear and branched products. Notably in these reactions, the fluorination pattern of the substrate enables the ligands to dictate the regioselectivity of the transformations.

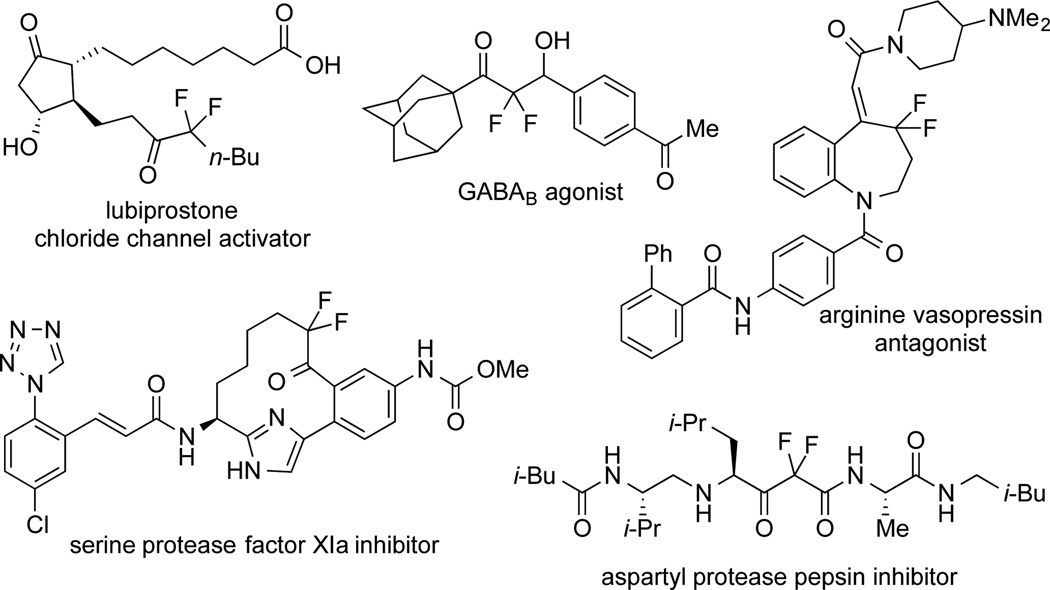

α,α-Difluoroketones represent a unique substructure in medicinal chemistry that inhibits serine and aspartyl proteases via interaction with the nucleophilic residue of a protease or a water molecule in the active site of the protease to form stable tetrahedral adducts.[8,9] In addition, this substructure can enhance bioactivities for alternate therapeutic targets,[10] and can serve as an intermediate for further functionalization (Figure 1).[11] Thus, strategies for accessing α,α-difluoroketones should be useful for the development of biological probes.

Figure 1.

α,α-Difluoroketones serve as drugs, biological probes, and synthetic intermediates.

Based on our ongoing studies aimed at accessing privileged fluorinated functional groups using decarboxylative strategies,[12] we envisioned that a decarboxylative strategy should afford α-allyl-α,α-difluoroketones from allylic alcohols. Decarboxylative allylation reactions of F-containing of nucleophiles are restricted to α-fluoroketones,[13] and decarboxylative reactions of α,α-difluoroketones have not been realized. Additionally, even simple allylation reactions of α,α-difluoroketone enolates remain restricted to a single reaction that uses stoichiometric Cu,[14] and no catalytic allylation reactions generate this substructure.

|

(1) |

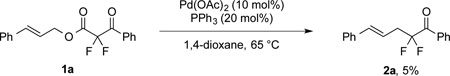

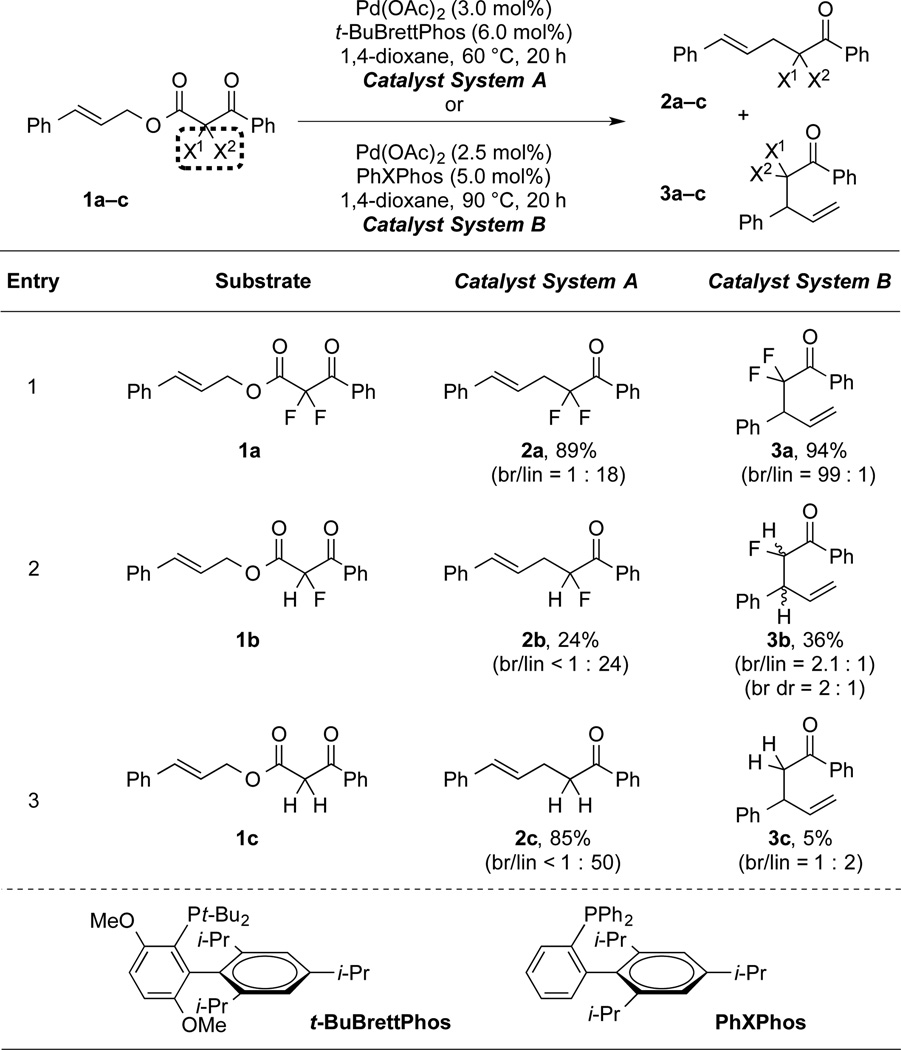

Initial attempts to develop a catalytic decarboxylative allylation reaction to generate α-allyl-α,α-difluoroketones revealed that a Pd-based catalyst could promote the desired transformation (eq. 1). A broad screen of P-based ligands identified biarylmonophosphines[15] as privileged ligands for the present reaction, and in fact, these ligands enabled access to both linear and branched products with high regioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Specifically, t-BuBrettPhos,[16] an electron-rich and bulky ligand generated linear product 2a in good yield and regioselectivity, and PhXPhos,[17] a smaller and more electron-deficient ligand, provided an uncommon branched product (3a) in excellent selectivity and yield (entry 1).[18] In the present reaction, the ligand-controlled regioselectivity was only observed for the α,α-difluorinated substrate, and the analogous mono- and non-fluorinated substrates did not provide branched products in good yield and regioselectivity (entries 2–3). Thus, the physicochemical perturbation resulting from fluorination of the substrate facilitated formation of the branched product.

Table 1.

Fluorination and Ligands Enable Regioselective Allylation Reactions.[a]

|

Catalyst System A: substrate (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (3.0 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (6.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.50 M), 60 °C, 20 h; Catalyst System B: substrate (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (2.5 mol%), PhXPhos (5.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.10 M), 90 °C, 20 h. For fluorinated products, yields and selectivities were determined by 19F NMR using PhCF3 or PhF as an internal standard, respectively. For non-fluorinated products, yields and selectivities were determined by 1H NMR using CH2Br2 as an internal standard.

Based on classical reactivity patterns, the ability of α,α-difluoracetophenone to provide both branched and linear products is unexpected. Traditionally for Pd-catalyzed allylation reactions, “hard” and “soft” nucleophiles have been identified by pKa, with hard nucleophiles (pKa > 25) being less acidic than soft nucleophiles (pKa < 25).[19] However for most pronucleophiles, the presence of a resonance-stabilizing group lowers the pKa and increases polarizability of molecular orbitals (e.g. ketone vs. β-ketoester or β-diketone).[1b, 20] In contrast for α,α-difluoroketones (pKa = 20.2),[21] the lower pKa results from an inductive effect that makes anions harder (negative fluorine effect).[22] Thus for the present allylation reaction, the α,α-difluoroketone enolates should be harder than acetophenone (pKa = 24.7),[21] which typically provides linear products.[1b,5] Thus based on classic hard/soft reactivity trends, the α,α-difluoroketones would not provide the uniquely observed branched product.

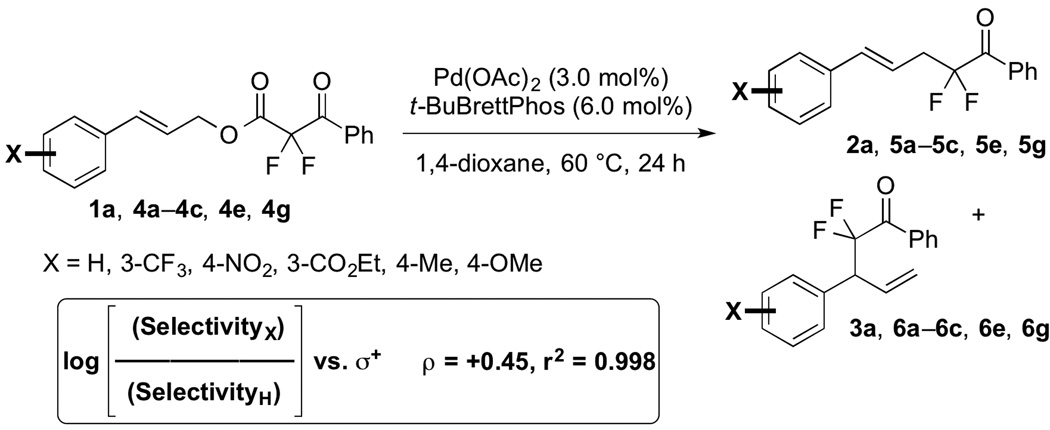

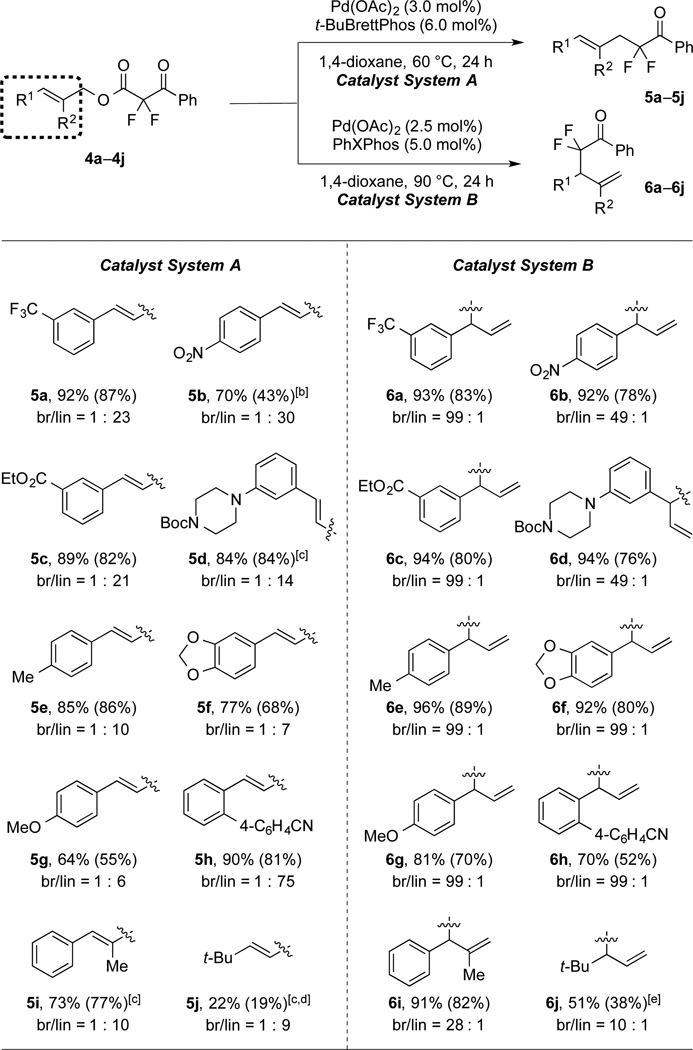

Utilizing the optimized conditions, a variety of substrates bearing electron-donating and -withdrawing functional groups on the cinnamyl component underwent regioselective coupling to provide both linear and branched products (Table 2). Notably, with catalyst system A [Pd(OAc)2/t-BuBrettPhos/1,4-dioxane/60 °C], electron-deficient allylic moieties (5a–c) provided better selectivity than neutral (5d–e) and electron-rich (5f–g) substrates. In addition, an ortho-substituted cinnamyl substrate provided linear product (5h) in excellent yield and selectivity. In contrast, catalyst system B [Pd(OAc)2/PhXPhos/1,4-dioxane/90 °C] showed excellent selectivity for branched products (generally > 49 : 1), regardless of electronic properties of the cinnamyl fragment (6a–h). Both catalyst systems tolerated substitution at the C-2 position of the allyl fragment (5i and 6i). However, the reaction of t-butyl-derived substrate (4j) provided low-to-modest yields of both linear and branched products (5j and 6j). Moreover, substrates bearing β-hydrogens on the allyl fragment underwent elimination to generate dienes instead of coupling products.

Table 2.

Reactions of Substrates Bearing Distinct Allyl Moieties.[a]

|

Catalyst System A: 4a–j (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (3.0 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (6.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.50 M), 60 °C, 24 h; Catalyst System B: 4a–j (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (2.5 mol%), PhXPhos (5.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.10 M), 90 °C, 24 h. 19F NMR yields for the major isomers were determined using PhCF3 as an internal standard (average of two runs). The values in parentheses represent the yields of the major products. The regioselectivities were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixtures.

70 °C.

Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (10 mol%).

100 °C.

130 °C, o-Xylene, the regioselectivities were determined by GC and 19F NMR of the crude reaction mixtures.

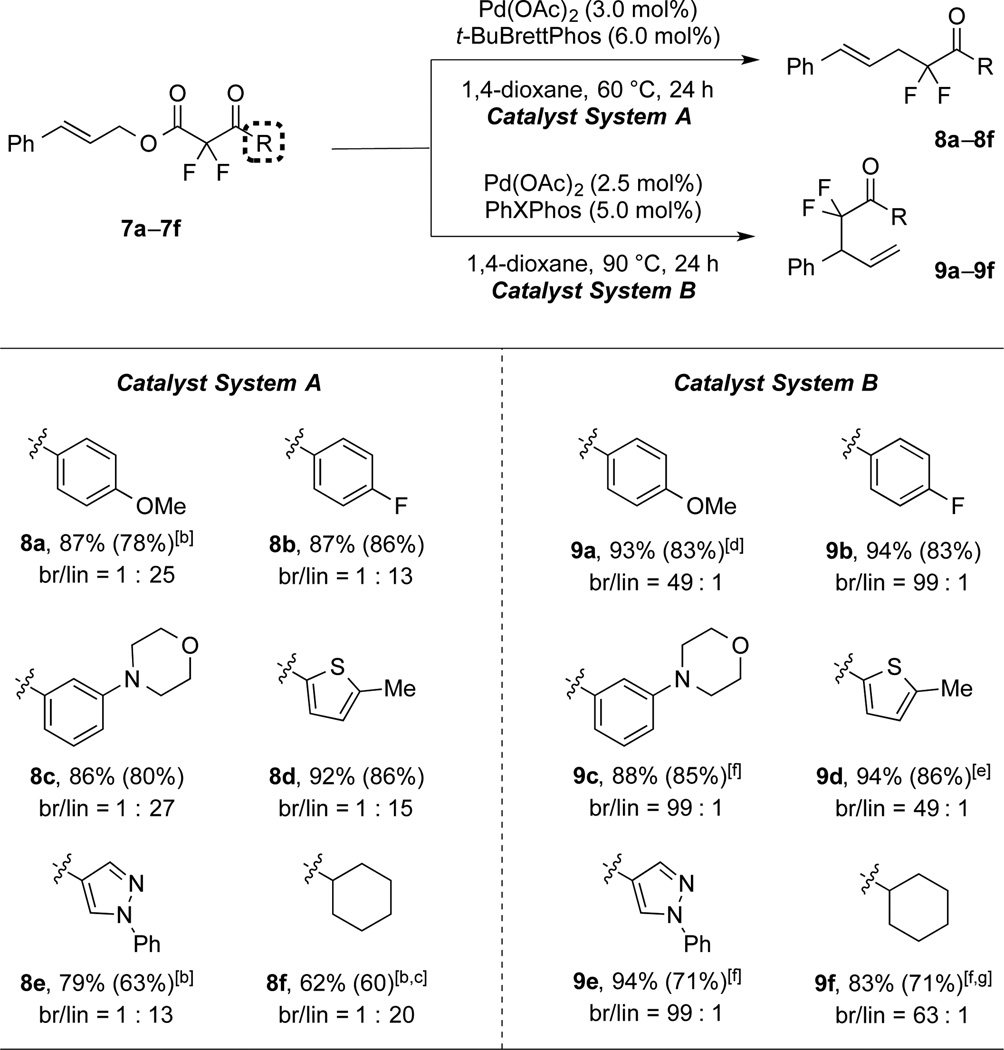

Both catalyst systems also transformed substrates bearing distinct aryl and alkyl α,α-difluoroketone moieties (Table 3). Reactions of electron-rich and neutral aryl α,α-difluoroketone substrates afforded good selectivities and yields for linear (8a–8c) and branched (9a–9c) products under both conditions. Even heteroaryl α,α-difluoroketone substrates (7d–7e) generated linear (8d–8e) and branched (9d–9e) products in good selectivities and yields. Using the standard reaction conditions, an aliphatic α,α-difluoroketone was less reactive; however, improved yields and high selectivities were obtained by increasing the catalyst loading [5 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 10 mol% ligands] and reaction time (8f and 9f). Thus, both catalyst systems enabled access to a variety of unique α,α-difluoroketone products that would be challenging to prepare otherwise.

Table 3.

Reactions of Substrates Bearing Distinct Ketone Moieties.[a]

|

Catalyst System A: 7a–f (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (3.0 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (6.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.50 M), 60 °C, 24 h; Catalyst System B: 7a–f (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (2.5 mol%), PhXPhos (5.0 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (0.10 M), 90 °C, 24 h. 19F NMR yields for the major isomers were determined by using PhCF3 as an internal standard (average of two runs). The values in parentheses represent the yields of the major products. The regioselectivities were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixtures.

Pd(OAc)2 (5.0 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (10 mol%).

70 °C, 36 h.

Pd(OAc)2 (3.5 mol%), PhXPhos (7.0 mol%).

18 h.

Pd(OAc)2 (5.0 mol%), PhXPhos (10 mol%).

90 °C, 36 h.

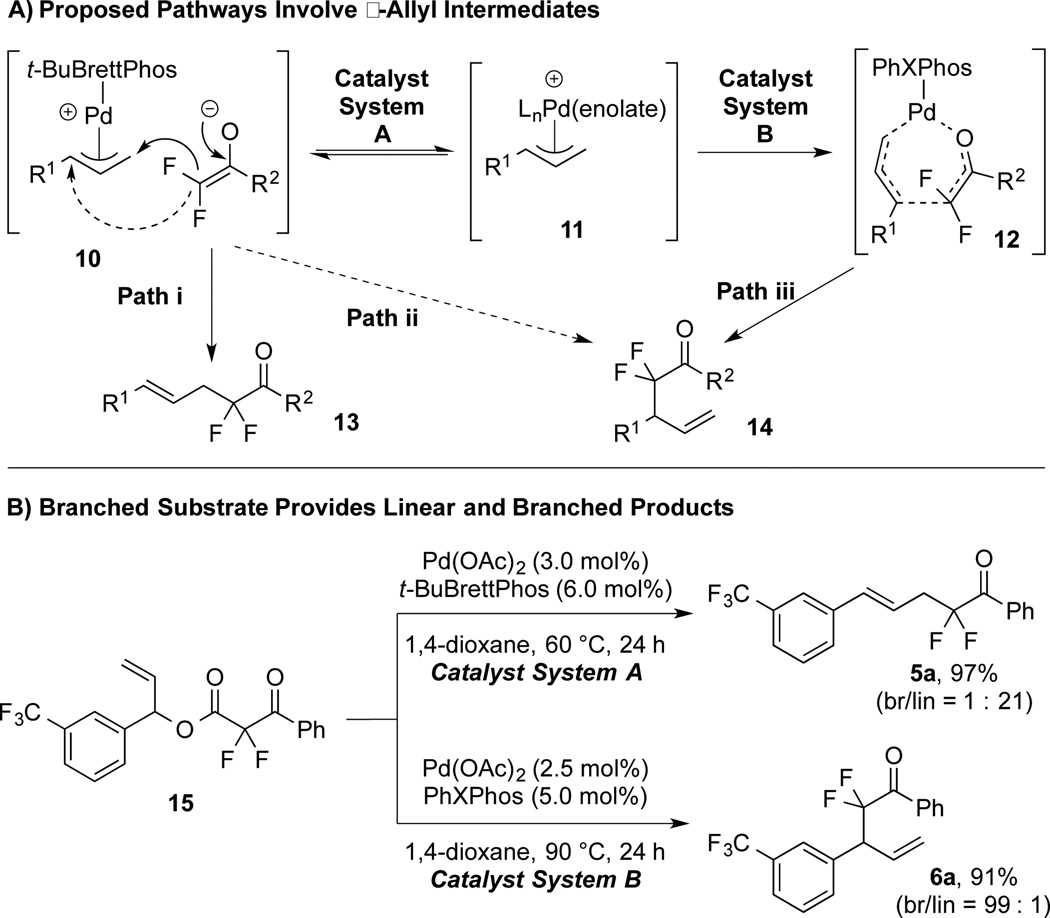

The complementary products may derive from a common Ln–Pd(π-allyl)(enolate) intermediate (11) via distinct ligand-controlled regioselective C–C bond-forming events (Figure 2A). To establish the intermediacy of a π-allyl complex, secondary ester 15 was subjected to both conditions A and B (Figure 2B), and the results were compared to reactions of the corresponding linear substrates (Table 2). System A transformed both linear and branched substrates (4a, 15) into linear product 5a in comparable selectivity (br/lin = 1 : 23 vs. 1 : 21), while system B transformed both linear and branched substrates (4a, 15) into branched product 6a in high selectivity (br/lin = 99 : 1). Combined, these data: 1) implicate the existence of π-allyl 11 in both reaction pathways; 2) discount memory effects controlling the regioselecivity for either system; 3) confirm that ligands ultimately control the regiochemical fate of the reaction.

Figure 2.

Formation of Linear and Branched Products May Involve a Common π-Allyl Intermediate.

Evaluation of the relationship between the electronic structures of cinnamyl-derived substrates and regioselectivities of catalytic reactions suggests that the branched and linear products derive from distinct pathways. For outer-sphere processes, the electronic structure of cinnamyl-derived substrates can perturb the regiochemical outcome of the reaction. Specifically, electron-rich substrates provide linear products in lower selectivity than electron-deficient substrates,[3a, 23] because SN1-like attack at the stabilized 2° position of the π-allyl intermediates (path ii) competes with SN2-like the attack at the unhindered 1° position (path i). For system A, a similar trend was observed, as confirmed by a linear free-energy correlation (Figure 3). Thus, system A may proceed predominantly via an analogous outer-sphere mechanism (path i).

Figure 3.

Catalyst System A: Improved Linear Selectivity for Electron-deficient Substrates.

In contrast, system B notably generates branched products that are less commonly observed in Pd-catalyzed allylation reactions of hard ketone enolates.[1b,5] If SN1-like attack of intermediate 10 would predominantly occur at the 2° position (path ii), the electronic properties of cinnamyl-derived substrates (1a, 4a–4c, 4e and 4g) would likely allow path i to compete and influence the regioselectivity of the reactions.[3a,23] However for system B, substrates bearing electron-rich, -neutral, and -deficient cinnamyl moieties all underwent coupling to afford branched products in high selectivities (3a, 6a–6c, 6e and 6g). This lack of a correlation between the electronic properties of cinnamyl-derived substrates and regioselectivity may discount outer-sphere path ii.

An alternate explanation for the unique regioselectivity involves the sigmatropic rearrangement of an η1-allyl intermediate (path iii).[24,25] Although this mechanism has been computationally predicted, experimental evidence for palladacyclic transition state 12 has not been established. In support of this rearrangement mechanism, non-metal-catalyzed 3,3-sigmatropic rearrangements of allyl α,α-difluoroenolethers similarly react more rapidly than the non-fluorinated counterparts.[26] Thus in the present case, the fluorine atoms might also provide unique physical properties that facilitate an analogous Pd-catalyzed rearrangement to provide the branched product.

In conclusion, both fluorination of a substrate and the selection of appropriate ligands facilitated a pair of orthogonal Pd-catalyzed regioselective decarboxylative allylation reactions to afford α,α-difluoroketone products. Computational studies should provide insight into the physicochemical basis by which fluorination enables formation of the branched product, and the relationship the between structures of the ligands and regioselectivities of the transformations. Ongoing work aims to exploit this reaction pathway to generate other unique fluorinated substructures, including enantioenriched products. We envision that these strategies should be useful for accessing α,α-difluoroketone-based probes that would otherwise be challenging to prepare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (5207h–DNI1) and the Herman Frasch Foundation for Chemical Research (701–HF12) for support of this research. Additional financial support from the University of Kansas Office of the Provost, Department of Medicinal Chemistry, and General Research Fund (2301795) is gratefully acknowledged. Support for the NMR instrumentation was provided by the NSF Academic Research Infrastructure Grant (9512331), the NSF Major Research Instrumentation Grant (9977422), and the NIH Center Grant (P20 GM103418).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) Baudoin O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1373. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604494. Angew. Chem.2007, 119, 1395; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weaver JD, Recio A, III, Grenning AJ, Tunge JA. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1846. doi: 10.1021/cr1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. Top Organomet Chem. 2013;44:281. [Google Scholar]; d) Arseniyadis S, Fournier J, Thangavelu S, Lozano O, Prevost S, Archambeau A, Menozzi C, Cossy J. Synlett. 2013;24:2350. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Recio A, III, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5630. doi: 10.1021/ol902065p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jana R, Partridge JJ, Tunge JA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5157. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100765. Angew. Chem.2011, 123, 5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Prétôt R, Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<323::AID-ANIE323>3.0.CO;2-T. Angew. Chem.1998, 110, 337; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) You S-L, Zhu X-Z, Luo Y-M, Hou X-L, Dai L-X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7471. doi: 10.1021/ja016121w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng W-H, Sun N, Hou X-L. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5151. doi: 10.1021/ol051882f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yang X-F, Yu W-H, Ding C-H, Ding Q-P, Wan S-L, Hou X-L, Dai L-X, Wang P-J. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:6503. doi: 10.1021/jo400663d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hayashi T, Kishi K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1743. [Google Scholar]; f) Johns AM, Liu Z, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7259. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701899. Angew. Chem.2007, 119, 7397; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Dubovyk I, Watson IDG, Yudin AK. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:1559. doi: 10.1021/jo3025253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Zheng B-H, Ding C-H, Hou X-L. Synlett. 2011:2262. [Google Scholar]; i) Fang P, Ding C-H, Hou X-L, Dai L-X. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:1176. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Trost BM, Weber L, Strege PE, Fullerton TJ, Dietsche TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:3416. [Google Scholar]; b) Kawatsura M, Uozumi Y, Hayashi T. Chem. Commun. 1998:217. [Google Scholar]; c) Boele MDK, Kamer PCJ, Lutz M, Spek AL, de Vries JG, Van Leeuwen PWNM, Van Strijdonck GPF. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:6232. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Weaver JD, Ka BJ, Morris DK, Thompson W, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12179. doi: 10.1021/ja104196x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Oliver S, Evans PA. Synthesis. 2013;45:3179. [Google Scholar]; b) Tsuji J, Yamada T, Minami I, Yuhara M, Nisar M, Shimizu I. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:2988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng W-H, Zheng B-H, Zhang Y, Hou X-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7718. doi: 10.1021/ja071098l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen P-P, Peng Q, Lei B-L, Hou X-L, Wu Y-D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14180. doi: 10.1021/ja2039503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bégué J-P, Bonnet-Delpon D. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine. Vol. 7. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2008. Inhibition of Enzymes by Fluorinated Compounds; pp. 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Gelb MH, Svaren JP, Abeles RH. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1813. doi: 10.1021/bi00329a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Corte JR, Fang T, Decicco CP, Pinto DJP, Rossi KA, Hu Z, Jeon Y, Quan ML, Smallheer JM, Wang Y, Yang W. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2011. WO 2011/100401 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Ginzburg R, Ambizas EM. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1091. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.8.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Han C, Salyer AE, Kim EH, Jiang X, Jarrard RE, Powers MS, Kirchhoff AM, Salvador TK, Chester JA, Hockerman GH, Colby DA. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:2456. doi: 10.1021/jm301805e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada Y, Taniguchi N, Matsuhisa A, Sakamoto K, Yatsu T, Tanaka A. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000;48:1644. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Ambler BR, Altman RA. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5578. doi: 10.1021/ol402780k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ambler BR, Peddi S, Altman RA. Synlett. 2014;25:1938. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1339128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Qiao Y, Si T, Yang M-H, Altman RA. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:7122. doi: 10.1021/jo501289v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Shimizu I, Ishii H. Tetrahedron. 1991;50:487. [Google Scholar]; b) Shimizu I, Ishii H, Tasaka A. Chem. Lett. 1989;18:1127. [Google Scholar]; c) Nakamura M, Hajra A, Endo K, Nakamira E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7248. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502703. Angew. Chem., 2005, 117, 7414; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Burger EC, Barron BR, Tunge JA. Synlett. 2006:2824. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi S, Tanaka H, Amii H, Uneyama K. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:1547. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Walker SD, Barder TE, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1871. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353615. Angew. Chem.2004, 116, 1907; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:27. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Ikawa T, Barder TE, Biscoe MR, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13001. doi: 10.1021/ja0717414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fors BP, Dooleweerdt K, Zeng Q, Buchwald SL. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:6576. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.For additional data regarding the selectivity imparted by the use of alternate biarylmonophosphine ligands, see the Supporting Information.

- 19.a) Trost BM. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Thaisrivongs DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14092. doi: 10.1021/ja806781u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norsikian S, Chang C-W. Advances in Organic Synthesis. 2013;3:81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bordwell FG. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:456. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Ni C, Zhang L, Hu J. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:5699. doi: 10.1021/jo702479z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang W, Ni C, Hu J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2012;308:25. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi T, Kawatsura M, Uozumi Y. Chem. Commun. 1997:561. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Keith JA, Behenna DC, Mohr JT, Ma S, Marinescu SC, Oxgaard J, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11876. doi: 10.1021/ja070516j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keith JA, Behenna DC, Sherden N, Mohr JT, Ma S, Marinescu SC, Nielsen RJ, Oxgaard J, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19050. doi: 10.1021/ja306860n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Méndez M, Cuerva JM, Gómez-Bengoa E, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:3620. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020816)8:16<3620::AID-CHEM3620>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Cresson P. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1964:2618. [Google Scholar]; b) Metcalf BW, Jarvi ET, Burkhart JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:2861. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.