Abstract

Our recent studies have demonstrated that the CD22 exon 12 deletion (CD22ΔE12) is a characteristic genetic defect of therapy-refractory clones in pediatric B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BPL) and implicated the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in the aggressive biology of relapsed or therapy-refractory pediatric BPL. The purpose of the present study was to further evaluate the biologic significance of the CD22ΔE12 molecular lesion and determine if it could serve as a molecular target for corrective repair using RNA trans-splicing therapy. We show that both pediatric and adult B-lineage lymphoid malignancies are characterized by a very high incidence of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect. We provide experimental evidence that the correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in human CD22ΔE12+ BPL cells using a rationally designed CD22 RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM) caused a pronounced reduction of their clonogenicity. The RTM-mediated correction replaced the downstream mutation-rich segment of Intron 12 and remaining segments of the mutant CD22 pre-mRNA with wildtype CD22 Exons 10-14, thereby preventing the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product. The anti-leukemic activity of this RTM against BPL xenograft clones derived from CD22ΔE12+ leukemia patients provides the preclinical proof-of-concept that correcting the CD22ΔE12 defect with rationally designed CD22 RTMs may provide the foundation for therapeutic innovations that are needed for successful treatment of high-risk and relapsed BPL patients.

Introduction

CD22, a member of the Siglec (sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectins) family of regulators of the immune system, is a negative regulator of multiple signal transduction pathways critical for proliferation and survival of B-lineage lymphoid cells1-3. B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BPL) is the most common form of cancer in children and adolescents.4 BPL cells express a dysfunctional CD22 due to deletion of Exon 12 (CD22ΔE12) arising from a splicing defect associated with homozygous intronic mutations.5 CD22ΔE12 results in a truncating frame shift mutation yielding a mutant CD22ΔE12 protein that lacks most of the intracellular domain including the key regulatory signal transduction elements.5 Our recent studies have demonstrated that CD22ΔE12 is a characteristic genetic defect of therapy-refractory clones in pediatric BPL and implicated the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in the aggressive biology of relapsed or therapy-refractory pediatric BPL.6 We also identified a previously unrecognized causal link between CD22ΔE12 and aggressive biology of BPL cells by demonstrating that siRNA-mediated knockdown of CD22ΔE12 in primary BPL cells is associated with a marked inhibition of their clonogenicity.7

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the biologic significance of the CD22ΔE12 molecular lesion in BPL and determine if it could serve as a molecular target for corrective repair using RNA trans-splicing therapy. We show that both pediatric and adult B-lineage lymphoid malignancies are characterized by a very high incidence of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect. We provide experimental evidence that the correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in human CD22ΔE12+ BPL cells using a rationally designed CD22 RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM) caused a pronounced reduction of their clonogenicity. The RTM-mediated correction replaced the downstream mutation-rich segment of Intron 12 and remaining segments of the mutant CD22 pre-mRNA with wildtype CD22 Exons 10-14, thereby effectively preventing the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product. The anti-leukemic activity of this RTM against BPL xenograft clones derived from CD22ΔE12+ leukemia patients provides the preclinical proof-of-concept that correcting the CD22ΔE12 defect with rationally designed CD22 RTM may provide the foundation for therapeutic innovations that are needed for successful treatment of high-risk and relapsed BPL patients.

Materials and Methods

Genomic PCR Analysis of the CD22 Gene for the Presence of CD22ΔE12-Associated Intronic Mutations

Total genomic DNA was extracted from primary ALL cells using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Catalog No. 6950) according to the manufacturer's specifications, as reported5. Genomic PCR was employed to amplify specific regions of the CD22 gene using the New England BioLabs Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Kit (Catalog No. F-553S) with 3-step thermal cycling conditions in a 50 µL reaction volume: Initial denaturation at 98°C × 30 sec followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98°C × 10 sec, annealing at 60°C × 30 sec and extension 72°C × 30 sec. A 905-bp PCR product encompassing the CD22 exons 12, 13, and their exon-intron junctions and the entire 132-bp mutational hotspot region of the intron between Exons 12 and 13 was amplified using the genomic PCR primer set P1 (Forward: 5′-GGCATGAGGCAGACTGTGAA-3′; Reverse: 5′-AACCTCTGCCACCACGGATG-3′). In some cases, a 471-bp PCR product encompassing Exon 12 and the mutation rich region of the intron between Exons 12 and 13 was amplified using the genomic PCR primer set P6 (Forward: 5′-AGCACTTCATCCTCGTCTCC-3′, Reverse: 5′-TGTAAAACCTGTGGCCTC-3′)5. PCR products were separated on 1% or 1.5% agarose gels and sized using the 1 Kb Plus DNA ladder from InVitrogen (Cat. No. 10787-018). The PCR products were cleaned using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Cat No. 28104) and submitted to the DNA Sequencing Core Facility of the University of Southern California for sequencing using the corresponding forward primer and the Applied Biosystems' dye-based (BigDye V3.1™) DNA sequencing method. In this procedure, 3′-fluorescent-labeled dideoxynucleotides (dye terminators) are incorporated into DNA extension products (cycle sequencing). DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer, using a long read protocol. The sequence obtained from each genomic PCR product was analyzed and aligned using SeqMan II contiguous alignment software in the LaserGene suite from DNASTAR Inc. and the MegAlign multisequence alignment software in comparison with the wild-type CD22 sequence (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000019.9. Homo sapiens chromosome 19, Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) primary reference assembly, www.ncbi.nih.gov5.

RT-PCR analysis of human leukemia cells for CD22ΔE12 mRNA expression

Reverse transcription (RT) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were used to examine expression levels of wildtype CD22 and CD22ΔE12 transcripts in human leukemia cells, as previously described.6 Total cellular RNA was extracted from ALL cells using the QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (Catalog No. 52304) (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, San Diego, CA, USA). The P7 primer set (5′-GCCAGAGCTTCTTTGTGAGG-3′ and 5′-GGGAGGTCTCTGCATCTCTG-3′) amplifies a 182-bp region of the CD22 cDNA extending from Exon 11 to Exon 13 and deletion of Exon 12 results in a smaller CD22ΔE12-specific PCR product of 63-bp size using this primer set. The P10 primer set was used as a positive control to amplify a 213-bp region of the CD22 cDNA in both wildtype CD22 and CD22 with ΔE12 (5′-ATCCAGCTCCCTCCAGAAAT-3′ and 5′-CTTCCCATGGTGACTCCACT-3′). QIAGEN One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Catalog No. 210212) (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA, USA) was used following manufacturer's instructions to amplify the target PCR product. The conditions were 1 cycle (30 min 50°C, 15 min 95°C); 35 cycles (45 sec 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C). PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Gel images were taken with an UVP digital camera and UV light in an Epi Chemi II Darkroom using the LabWorks Analysis software (UVP, Upland, CA).

Leukemia cells

We used (i) BPL xenograft clones (N=5) that were derived from spleen specimens of xenografted NOD/SCID mice inoculated with human BPL cells from deidentified left-over fresh bone marrow specimens from pediatric BPL patients, (ii) primary leukemia cells from previously cryopreserved deidentified leukemic bone marrow/blood specimens of leukemia cells of 128 newly diagnosed pediatric ALL patients, including 14 with infant ALL (Age<1 y), 62 with high-risk BPL (Age ≥10 years or Age 1-9 years with presenting WBC ≥50,000/µL), 36 with standard-risk BPL (Age 1-9 years and WBC<50,000/µL), and 16 with T-lineage ALL, and (iii) bone marrow hematopoietic cells from previously cryopreserved and deidentified matched pair (initial diagnosis and post-induction 1st remission) bone marrow specimen sets of 5 BPL patients. The secondary use of leukemic cells for subsequent laboratory studies did not meet the definition of human subject research per 45 CFR 46.102 (d and f) since it did not include identifiable private information, and it was approved by the IRB (CCI) at the Children's Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) (Protocol #′ CCI-09-00304 approved on 12-16-2009 and CCI-10-00141 approved on 7-27-2010); Human Subject Assurance Number: FWA0001914. We also used the ALL-1 (Ph+ adult BPL), REH (BPL), RAJI (Burkitt's lymphoma/leukemia), MAVER (MCL), JaKo1 (MCL), and Z-138 (CLL) cell lines.

Gene expression profiling of primary human leukemia cells

Expression values for CD22 and CD7 genes were compared for a subset of newly diagnosed BPL (GSE1187, N=207; GSE13159, N=575; GSE13351, N=92), newly diagnosed T-lineage ALL (GSE13159, N=174; GSE13351, N=15) and normal bone marrow hematopoietic cells (GSE13159, N=74). A more targeted comparison was also performed comparing high-risk BPL subsets with MLL gene rearrangements (MLL-R+) (GSE11877, N=21; GSE13159, N=70; GSE13351, N=4), E2A-PBX1 fusion transcript expression/t(1;19) translocation (GSE11877, N=23; GSE13159, N=36), GSE13351, N=2), BCR-ABL fusion transcript expression/Philadelphia chromosome(Ph)+(GSE13159, N=122; GSE13351, N=1) and normal hematopoietic cells (GSE13159, N=74). Significance was assessed for pairwise comparisons of BPL, T-lineage ALL and high-risk BPL with Normal samples using Student's T-tests (Unequal Variances). P-values less than 5% were deemed significant. We used a one-way agglomerative hierarchical clustering technique to organize expression patterns using the average distance linkage method such that genes (rows) having similar expression across patients were grouped together (average distance metric). Dendrograms were drawn to illustrate similar gene-expression profiles from joining pairs of closely related gene expression profiles, whereby genes joined by short branch lengths showed the most similarity in expression profile across all samples.

We compiled archived transcriptome profiling datasets in the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array platform regarding gene expression levels in primary leukemia cells from (i) pediatric BPL patients (GSE11877, N=207; GSE13159 N=823; GSE13351 N=107; GSE18497, N=82, GSE28460, N=98; GSE7440, N=99; Total N in 6 datasets =1416), and (ii) adult leukemia/lymphoma patients (with a focus on patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL], mantle cell leukemia/lymphoma [MCL], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL], and follicular lymphoma [FL]) (GSE10846 (N=420), GSE12195 (N=136), GSE12453 (N=67), GSE13159 (N=522), GSE35348 (N=27), GSE36000 (N=38), GSE39671 (N=130) and GSE53820 (N=81); Total N in 8 datasets =1421). To enable comparison of samples across studies, 2 sets of normalization procedures were performed that merged the raw data from the 6 datasets (CEL files) for the pediatric patients and 8 datasets for the adult patients. Perfect Match (PM) signal values for probesets were extracted utilizing raw CEL files matched with probe identifiers obtained from the Affymetrix provided CDF file (HG-U133_Plus _ 2.cdf) implemented by Aroma Affymetrix statistical packages run in R-studio environment (Version 0.97.551, R-studio Inc., running with R 3.01). The PM signals were quantified using Robust Multiarray Analysis (RMA) in a 3-step process including RMA background correction, quantile normalization, and summarization by Median Polish of probes in a probeset across 1416 pediatric and 1421 adult patients (RMA method adapted in Aroma Affymetrix). RMA background correction estimates the background by a mixture model whereby the background signals were assumed to be normally distributed and the true signals are exponentially distributed. Normalization was achieved using a two-pass procedure. First the empirical target distribution was estimated by averaging the (ordered) signals over all arrays, followed by normalization of each array toward this target distribution.

BLAT analysis of CD22 probe sequences for probeset 217422_s_at (covering exons 10-14) deposited in the Affymetrix NetAffx™ Analysis Center (http://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/index.affx) was mapped onto specific CD22 exons and visualized using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgBlat?command=start). This analysis was designed to locate ≥25-bp long sequences with ≥95% similarity in the entire genome. The BLAT-based exon designations according to 3 reference sequences (viz.: UCSC genes, Ensembl gene predictions, Human mRNA Genbank) were as follows: HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_11 aligned to chr19: 35837525-35837549 (Exon 14); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_10 aligned to chr19: 35837478-35837502 (Exon 14); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_8 aligned to chr19: 35837100-35837124 (Exon 13); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_9 aligned to chr19: 35837117-35837139 (Exon 13); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_7 aligned to chr19:35836590-35836614 (Exon12); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_6 aligned to chr19:35836566-35836590(Exon12); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_5 aligned to chr19:35836535-35836559(Exon12); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_4 aligned to chr19:35835979-35836003 (Exon 11); HG-U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_3 aligned to chr19:35835811-35835960 (Exon 11); HG- U133_PLUS_2:217422_S_AT_2 aligned to chr19:35835741-35835765 (Exon 10). Background corrected and RMA-normalized signal values for each probe in each sample were log2 transformed and median centered across 11 probes per sample. A CD22ΔE12-index was calculated by subtracting the average of the expression values for 7 probes interrogating non-exon 12 regions of the gene from the average expression of the 3 probes that interrogated CD22 Exon 12. The expression values were normalized to the median expression value across all the probes in the probeset for CD22 receptor, 217422_s_at, to compare the relative expression of the CD22 Exon 12 probes to non-exon12 probes and minimizing the effect of outlier probes on the calculation of the CD22ΔE12-index. The CD22ΔE12 index values were calculated and compared for (i) BPL (N=874; GSE11877, GSE13159 and GSE13351) vs. T-lineage ALL (N=189; GSE13159 and GSE13351) vs. normal bone marrow hematopoietic cells (N=74; GSE13159), (ii) normal bone marrow hematopoietic cells vs. MLL-R+ (N=95; GSE11877, GSE13159, GSE13351), BCR-ABL+ (N=123; GSE13159, GSE13351) and E2A-PBX1+ (N=61; GSE11877, GSE13159, GSE13351) subsets of BPL, (iii) and CLL (N=578; GSE13159, GSE39671) vs. DLBCL (N=498; GSE10846, GSE12195, GSE12453) vs. FL (N=124; GSE12195, GSE12453, GSE53820) vs. MCL (N=38; GSE36000) vs. normal lymphoid cells (N=130; GSE10846, GSE12195, GSE12453, GSE13159). We also used the archived gene expression profiling (GEP) data on primary leukemia cells in relapse specimens from pediatric BPL patients (GSE18497: 27 patients and GSE28460: 49 patients) in order to compare the gene expression profiles and CD22ΔE12 index values of initial diagnostic vs. relapse clones from 76 BPL patients. The matched-pair T-test was used to compare the gene expression values and the CD22ΔE12 indices of primary leukemia cells from diagnostic vs. relapse specimens of BPL patients (JMP v7, SAS, Cary, NC). To compare the incidence of CD22ΔE12 in subsets of patients the proportion of leukemic samples below the lower 95% Confidence interval for normal non-leukemic cells vs. leukemia/lymphoma cells for each patient sub-population was determined. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc method was utilized to calculate P-values of the comparisons.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR for detection of CD22ΔE12 mRNA

All assays were conducted in 96-well plates with a 50 uL reaction/sample volume using the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System housed in the CHLA Stem Cell Core Facility. Controls included splenocytes from homoyzgous CD22ΔE12-stop-excised KIhomo,Cre- mice. In brief, total cellular RNA was extracted from the cells (∼5×106 cells/sample) using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Cat# 74104, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's specifications and the RNA concentration in each sample was adjusted to 40 ng/µl using RNAse-free water. The qRT-PCR reaction was carried out using 5-µl (∼200-ng) total RNA in a 50-μL reaction volume/sample with a 2-step thermal cycling program, which included (i) reverse transcription reaction at 48°C × 30 min, (ii) initial Taq polymerase activation at 95°C × 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C × 30 sec, annealing/extension at 60°C × 1 min with a forward primer (E11-F2) 5′-CAGCGGCCAGAGCTTCTT-3′ (100 nM) and a reverse primer (E13-R2) 5′-GCGCTTGTGCAATGCTGAA -3′(100 nM). This primer set amplified a 113-bp fragment from Exon 11 to 13 of the human CD22ΔE12 cDNA. The amplified fragment was then specifically annealed to a pre-mixed oligo DNA probe (5′-TGTGAGGAATAAAAAGAGATGCAGAGTCC-3′) conjugated with a 5′FAM reporter and a 3′BHQ Quencher on the junction region between Exon 11 and Exon 13. Quantification was based on the increased intensity of the FAM reporter fluorescence, which was measured and recorded using the sequence detection system of the real-time qPCR system (SDS2.3) and expressed on the threshold cycle value Ct. To ensure the quality and the quantity of RNA for each patient sample and human leukemia cell lines, we also simultaneously ran a qRT-PCR reaction for β-actin with a forward primer 5′-GGACTTCGAGCAAGAGATGG-3′, and a reverse primer 5′- AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3′. This primer set amplifies a 234-bp region at the junction between Exon 4 and Exon 5 of the human beta actin gene. Likewise, we ran a qRT-PCR reaction for mouse β-actin with a forward primer 5′- CCTCTATGCCAACACAGTGC-3′ and a reverse primer 5′- CCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATC-3′ to evaluate the quality of RNA from CD22ΔE12-KI mouse splenocytes. This primer set amplifies a 206-bp region at the junction between Exon 4 and Exon 5 of the mouse beta actin gene. These qRT-PCR reactions employed the Power SYBR®Green One-Step PCR Master Mix Kit (Cat #4367659, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Each reaction comprised 25 μl 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, forward and reverse primer at 100 nM, ∼200 ng total RNA template and sterile water up to a final volume of 50 µl. The quantification was based on the increased reporter fluorescence, which was measured and recorded using the sequence detection system. Results were expressed in terms of the threshold cycle value Ct; the cycle at which the change in fluorescence of the amplicon for the SYBR dye passes a significance threshold automatically determined by the real-time PCR system software (SDS2.3) based on the fluorescence of the fixed threshold no template control sample. In both PCR assays, the Ct value was identified as the intersection of the fluorescent intensity curve and threshold line and used as a relative measurement of the concentration of the CD22ΔE12 cDNA template in the PCR reaction. The Ct-values for the housekeeping gene β-actin were used as a reference to normalize the Ct value of each leukemic sample for comparative analysis. To visualize the CD22ΔE12 band, selected patient samples were also used to perform one-step RT-PCR reaction (Qiagen, Cat# 210210) with the same primer set (or in some cases with the P7 primer set E11-F1 and E13-R1). The P10 primer set was also included to confirm expression of the CD22 gene in all samples. The cycling conditions are: 30 min reverse-transcription reaction at 50°C immediately followed by 15 min initial PCR activation step, and 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C × 1 min, annealing at 60°C × 1 min, and extension at 72°C × 1 min. RT-PCR products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Gel images were taken with an UVP digital camera and UV light in an Epi Chemi II Darkroom using the LabWorks Analysis software (UVP, Upland, CA).

Colony assays

The effects of the indicated transfections with CD22 RTM on the clonogenic survival of immature human BPL cell line ALL-1 and mature Burkitt's lymphoma cell line RAJI were examined using in vitro colony assays as described.5 RAJI is a radiation-resistant Burkitt's leukemia/B-ALL cell line. ALL-1 is a chemotherapy-resistant BCR-ABL+ t(9; 22)/ Ph+ pre-pre-B ALL cell line. Both cells lines are CD22ΔE12-positive.5-7 After transfection with control RTM or CD22 RTM, cells (0.5×106 cells/mL) were suspended in RPMI supplemented with 0.9% methylcellulose, 30% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine7. Controls included untreated cells. Duplicate 1 mL samples containing 0.5×106 cells/sample were cultured in 35 mm Petri dishes for 7 d at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. On d7, colonies containing ≥20 cells were counted using an inverted Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope.

In vitro assays

Reverse transcription (RT) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were used to examine the expression levels of wildtype CD22 and CD22ΔE12 transcripts in human leukemia cells, as previously described.6 One-step real-time quantitative (q) RT-PCR was performed using the One-Step PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Cat. # RR064B, Takara/Clontech, Mountain View, CA) to compare the expression levels of the CD22ΔE12 mRNA in BPL xenograft clones and primary BPL cells from newly diagnosed pediatric BPL patients. PCR, RT-PCR, and qRT-PCR assays as well as Western blots and colony assays were also performed according to standard procedures.5-8

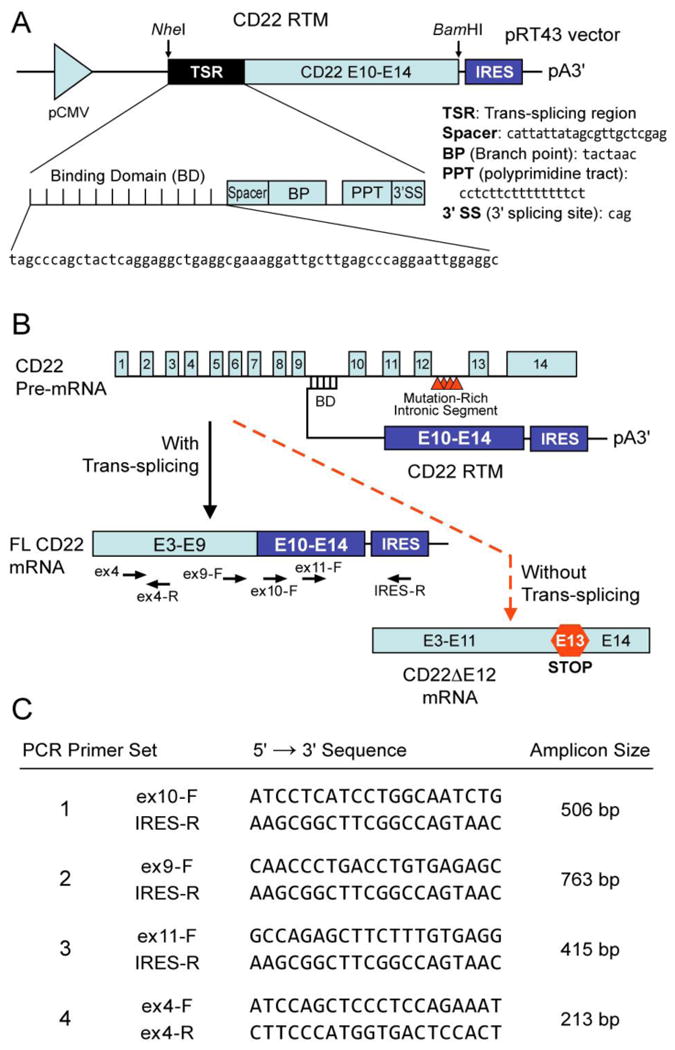

Construction of the CD22 RNA-trans-splicing molecule (RTM) and transfection of ALL cells

We have constructed a plasmid that expresses an RTM with a rationally designed anti-sense binding domain targeting a 60-nt complementary non-coding region close to the 5′ splice site of CD22 Intron 9 that confers specificity by tethering the RTM to its target pre-mRNA (Figure 1). This RTM was designed to bind to the CD22 pre-mRNA via conventional Watson-Crick base pairing and replace the downstream mutation-rich segment of intron 12 and remaining segments in leukemia cells with CD22ΔE12 with wildtype CD22 Exons 10-14. This trans-splicing process would thereby prevent the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product. The trans-splicing RTM vector was created by cloning CD22 Exons 10-14 as the coding sequence to be trans-spliced and the elements of the 3′ trans-splicing arm into a pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector (Clontech) followed by replacing the AcGFP sequence from the vector with mCherry (EMBL, Accession # LM652706). ALL cell lines ALL-1 (BPL) and RAJI (Burkitt's leukemia/B-cell ALL) and ALL xenograft cells were transfected with 8 μg of RTM plasmid DNA using the Amaxa Nucleofector Kit (Catalog No. VPA-1010) (Lonza, Cologne, Germany). 500,000 cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 100 μl nucleofector solution and 8 μg RTM plasmid DNA. This cell+DNA suspension was transferred into a certified cuvette and inserted into a nucleofector cuvette holder and the Nucleofector Program Z-001 was applied. 500 μl of pre-equilibrated culture medium were gently added to the cuvette upon program completion and the cell suspension was transferred into a 6-well tissue culture plate (final volume 1.5 ml media per well). Controls included cells transfected with a control plasmid that does not contain any binding domain or CD22 Exons 10-14, as well as cells transfected with an irrelevant control RTM plasmid specific for the dystrophin gene (EMBL, Accession # LM652708). Both control plasmids were derived from the same pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector as the CD22 RTM plasmid. For colony assays, cells were immediately cultured for 7 days at 37°C/5% CO2 in alpha-MEM supplemented with 33% calf bovine serum and 0.8% methylcelluose (100,000 cells/35 mm Petri dish, in duplicate). For RT-PCR assays, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum for 48 hours prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from RTM-transfected cells using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit from Qiagen (Cat No 74134; Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). One μg total RNA per sample was used to generate the first-strand cDNA with oligo (dT) primers using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The PCR reaction was performed with thermal conditions: initial activation 98°C × 30s, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation 98°C × 10 s, annealing 60°C × 10 s, extension 72°C × 30 s using 2 sets of primers (Figure 1 B&C): set 1: hCD22E10-Fwd.: 5′-ATCCTCATCCTGGCAATCTG-3′ /IRES-R: 5′- AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′, set 2: hCD22E9-Fwd 5′-CAACCCTGACCTGTGAGAGC-3′/IRES-R: 5′-AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′. The PCR reaction with the primer set 1 produces a unique 506-bp band demonstrating a successful transfection. The PCR reaction with the primer set 2 generates a unique 763-bp band showing that trans-splicing has occurred between the native CD22DE12 pre-mRNA and the GUESS1-CD22E10-14-IRES-mCherry vector followed by integration. Additional RT-PCR reactions were performed following Qiagen OneStep RT-PCR (Qiagen, Cat# 210210) guidelines with approximately 100 ng RNA per reaction. The sequences of oligonucleotides were: 1) Forward 5′- GCCAGAGCTTCTTTGTGAGG (CD22 Exon 11) and Reverse 5′- AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′ (RTM1-4494-5263), which was used to amplify a ∼415-bp to confirm a successful transfection; 2) previously reported P10 primer set6, Forward: 5′-ATCCAGCTCCCTCCAGAAAT-3′, Rev.: 5′- CTTCCCATGGTGACTCCACT-3′) which amplifies a 213-bp region spanning Exon 4; 3) previously reported P7 primer set, Forward: 5′-GCCAGAGCTTCTTTGTGAGG-3′, Reverse: 5′- GGGAGGTCTCTGCATCTCTG-3′, which was used to amplify a 182-bp region from Exon 11 to 13. The cycling conditions were: 30 min reverse-transcription reaction at 50°C immediately followed by 15 min initial PCR activation step, and 35 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 94°C, 1 min annealing at 58°C, and 1 min extension at 72°C.

Figure 1. CD22 Trans-splicing with an RNA Trans-splicing Molecule (RTM).

[A] RTMs have 3 main elements, 1) an anti-sense binding domain (BD) within a trans-splicing region (TSR) which serves as a “targeting moiety” that confers specificity by tethering the RTM to its target pre-mRNA; 2) a 3′ and/or 5′ splice site; and 3) a coding sequence to be trans-spliced, which can re-write most of the targeted pre-mRNA by replacing one or numerous exons anywhere in a message. Depicted is a schematic representation of the CD22 RTM that contains a BD targeting sequence complementary to a 60 nucleotide region close to the 5′ splice site of CD22 Intron 9 of the human CD22 gene, a 3′ Splice Site (3′SS) and the coding regions of the human CD22 exons 10-14. [B] Spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing to replace the deleted CD22 exon 12 (E12) using a CD22 RTM. This RTM was designed to bind to the CD22 pre-mRNA via conventional Watson-Crick base pairing and replace via trans-splicing the downstream mutation-rich segment of intron 12 and remaining segments in leukemia cells with CD22ΔE12 with wildtype CD22 exons 10-14 and thereby prevent the generation of the Cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product. The trans-splicing RTM vector was created by cloning CD22 exons 10-14 as the coding sequence to be trans-spliced and the elements of the 3′ trans-splicing arm into a pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector (Clontech) followed by removal the IRES/GFP sequences from the vector. When trans-splicing occurs, a corrected full-length CD22 mRNA is created from the natural CD22ΔE12 gene, which contains intronic mutations that are associated with Exon 12 deletion. The corrected mRNA would be expressed under the endogenous regulation of the cell.

Results

CD22 expression and Incidence of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in B-lineage lymphoid malignancies

Using archived datasets for BPL, we sought to determine the incidence of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect. Two probesets on the Affymetrix genechip detected the expression of the CD22 receptor gene by hybridizing to the 3′ region of the gene (204581_at and 38521_at) and one probeset detected expression of Exon 12 relative to Exons 10, 11, 13 and 14 of the CD22 gene (217422_s_at). These Affymetrix probesets enabled the comparison of the expression of CD22 gene in normal vs. leukemic cells (or leukemia cells from different patient populations) as well as expression levels of CD22 Exon12 relative to other CD22 exons. We predicted an overall increase in CD22 gene expression in BPL cells and a reduction in expression of CD22 Exon12 as a result of CD22ΔE12. Transcripts detected by 2 CD22-specific probesets that did not contain any probes for exon 12 of the CD22 gene exhibited highly significant increases across 874 primary leukemia samples from newly diagnosed pediatric BPL (but not T-lineage ALL) patients and these probesets were strongly correlated with each other (Figure S1A; 204581_at: Fold Difference = 3.90, P<0.0001), 38521_at : Fold Difference = 3.50, P < 0.0001). Conversely, transcripts detected by 2 CD7-specific probesets for the gene encoding the T-lineage surface antigen CD7 (214049_x_at: Fold Difference = 6.21, P<0.0001, 214551_s_at : Fold Difference = 4.89, P<0.0001) were significantly upregulated in primary samples from pediatric T-lineage ALL (but not BPL) patients. One probeset, 217422_s_at, that contained probes for the CD22 Exon 12 was also used to compare the exon-specific CD22 transcript levels for Exon 12 vs. Exons 13-14 in primary leukemia cells from 874 BPL and 189 T-lineage ALL patients vs. normal hematopoietic cells in non-leukemic control samples (N=74). A significant reduction in expression for Exon 12 (1.74 fold decrease) with a concomitant significant increase in expression for Exons 13-14 probes (1.38 fold increase) was observed in BPL (Figure S1B; Dunnett's post-hoc, P<0.0001). A CD22ΔE12-index was calculated by subtracting the median centered expression values of the 7 probes for CD22 Exons 10-11 and CD22 Exons 13-14 in the 217422_s_at probeset from the median centered expression values of the 3 CD22 Exon 12 probes. We found highly significant reductions in Exon12 index for primary leukemia cells in newly diagnosed pediatric B-precursor ALL patients (N=1416) vs. normal hematopoietic cells in non-leukemic control specimens (N=74), consistent with a high incidence of CD22ΔE12 (Fold Difference = 1.73 decrease, Dunnet's Post-hoc, P<0.0001) (Figure S1C). Three high-risk BPL subsets (E2A-PBX1+, Fold Difference = 1.9 fold decrease; MLL-R+, 1.4 fold decrease; BCR-ABL+, 1.4 fold decrease) all exhibited significant reductions in CD22ΔE12 index (Figure S1C; P<0.0001 for all leukemic vs normal specimen comparisons). Analysis of the gene expression profiles of primary leukemia cells in matched pair relapse vs. initial diagnosis samples of 76 pediatric relapsed BPL patients showed a significant and selective reduction of Exon 12 transcript levels at relapse (Figure S2A; Paired T-test, T-value = 5.33, DF = 75, P < 0.0001). Comparison of the CD22ΔE12-index values for these 76 matched-pair specimens revealed consistent and significant reduction of the CD22ΔE12-index at relapse for both studies (Paired T-test, Df = 75, T value = -5.33, P <0.0001). In 78% of the cases, the CD22ΔE12-index values were lower at relapse than at initial diagnosis (21/27 paired samples for GSE18497, Paired T-test, P = 0.0007; 38/49 paired samples for GSE28460, Paired T-test, P = 0.0002; Figure S2B). Examination of CD22ΔE12 index values for high-risk pediatric BPL subsets compiled from 3 studies (GSE11877, GSE13159, GSE13351) revealed significant differences for all comparisons against normal samples (ANOVA, F3,349 = 36.6, P<0.0001; Dunnett's post hoc P<0.0001 for all comparisons with normal). There was a high incidence of CD22ΔE12 in genetically defined high-risk BPL subsets, whereby 97% of E2A-PBX1+ (N=61, P<0.0001), 82% of MLL-R+ (N = 95, P<0.0001) and 85% of BCR-ABL+ BPL cases (N=123, P<0.0001) exhibited CD22ΔE12-index values below the lower 95% confidence value for normal samples (N=74) (Figure S3A). Taken together these results suggest that there is a loss of CD22 Exon 12 in E2A-PBX1+, MLL-R+, BCR-ABL1+ and relapsed BPL cases.

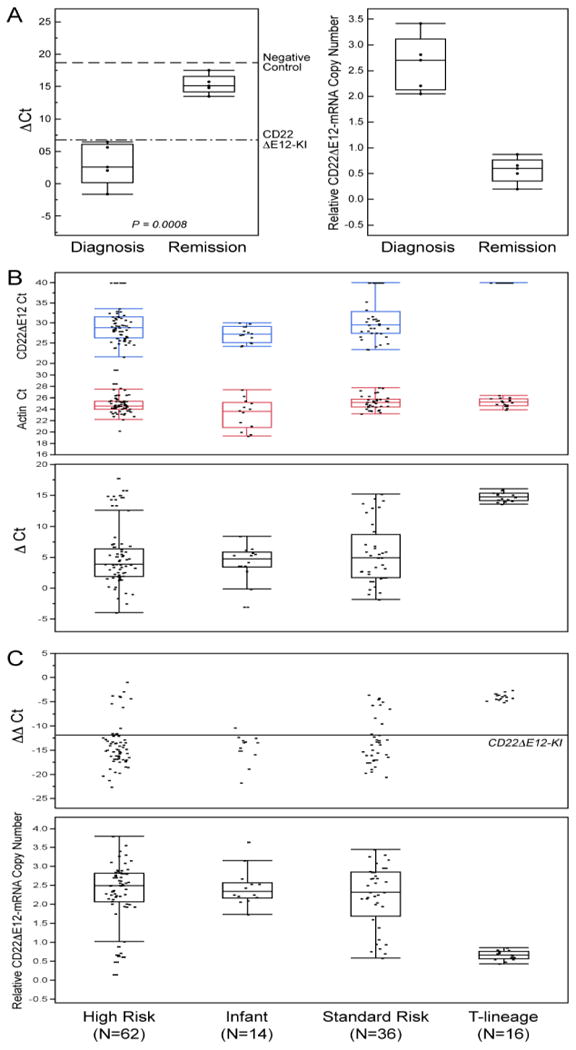

Detection of CD22ΔE12 in Primary Leukemia Cells from Newly Diagnosed Pediatric ALL Patients Using Quantitative RT-PCR

CD22ΔE12 mRNA was detected by standard qualitative RT-PCR in RNA isolated from primary leukemia cells of infants with ALL, pediatric BPL patients in relapse, as well as newly diagnosed BPL patients (Figure S4). We next used a quantitative RT-PCR assay for detection of CD22ΔE12 in primary BPL cells. We first performed quantitative qRT-PCR analyses of primary leukemia cells from 10 patients with newly diagnosed BPL with or without intronic mutations of the CD22 gene that are associated with the CD22ΔE12-genetic defect. The qRT-PCR test was positive for each of the 9 cases where the PCR-based genomic sequence analysis of the CD22 gene revealed mutations within a mutation-rich hotspot region of the intronic sequence between CD22 exons 12 and 13, but not in one case (UPN121) with no intronic mutations (Table S1). We then used qRT-PCR to evaluate 5 matched pair diagnosis vs. post-treatment remission bone marrow specimens from one standard-risk and 4 high-risk BPL patients to compare their cellular CD22ΔE12-mRNA levels. These analyses demonstrated a marked reduction of the CD22ΔE12 mRNA levels after chemotherapy. There was a significant increase in ΔCt values (Paired T-test, P = 0.0008) comparing remission (15.3 ± 0.65) to diagnosis (3.02 ± 1.44) and a corresponding decrease in the relative copy numbers in these samples (Diagnosis = 2.64 ± 0.24 versus Remission = 0.57 ± 0.11) (Figure 2A). These findings demonstrate that normal hematopoietic cells in the remission bone marrow of CD22ΔE12+ BPL patients do not express the aberrant CD22ΔE12 mRNA associated with the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect.

Figure 2. Detection of CD22ΔE12 mRNA in ALL Cells Using Quantitative RT-PCR.

[A] Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of 5 matched pair diagnosis vs. post-treatment remission bone marrow specimens from one standard-risk and 4 high-risk BPL patients demonstrated a marked reduction of the CD22ΔE12 mRNA levels after chemotherapy. Upper subpanel: Depicted are the ΔCt values for the paired samples at diagnosis and remission referenced to both negative (dashed line: CD22ΔE12-negative 293T cell line, mean ΔCt = 18.7 ± 2.8) and positive controls (Dotted/dashed line: splenocytes from CD22ΔE12-KI mice, mean ΔCt = 6.8 ± 3.3). There was a significant increase in ΔCt values (Paired T-test, P = 0.0008) comparing remission (15.3 ± 0.65) to diagnosis (3.02 ± 1.44) and a corresponding decrease in the relative copy numbers in these samples (Diagnosis = 2.64 ± 0.24 versus Remission = 0.57 ± 0.11). These findings indicate that CD22ΔE12 (at the transcript level detected by qRT-PCR) is a somatic defect that is unique to B-lineage leukemia cells. Lower subpanel: CD22ΔE12-mRNA copy number estimations were performed by comparing the ΔΔCt values of the samples to the CD22KI positive controls and depicted using dot plots. A decrease in the relative CD22ΔE12-mRNA copy number was observed at remission (Relative copy number at diagnosis = 2.64 ± 0.24 (Median = 2.71, Range = 2.05-3.41)) vs. Relative copy number at remission = 0.57 ± 0.11 (Median = 0.61, Range = 0.20-0.87). [B & C] We used the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System. The PCR primer pair was designed to amplify a 113-bp fragment spanning from Exon 11 to Exon 13 of the human CD22 cDNA. The amplified fragment was then specifically annealed to a pre-mixed oligo DNA probe (5′-TGTGAGGAATAAAAAGAGATGCAGAGTCC-3′) conjugated with 5′ FAM reporter and 3′BHQ Quencher on the CD22ΔE12-specific unique junction region between Exon 11 and Exon 13. A normalization procedure employing actin RT-PCR results was utilized to calculate the delta (Δ)Ct values. The ΔΔCt values were determined by subtracting the mean ΔCt value for negative controls (viz., 293-T human kidney cell line; mean delta Ct = 18.7 ± 1.6) from the ΔCt values for each sample. The mean ΔΔCt for the homozygous CD22ΔE12-KI splenocytes (positive control) was -11.9 ± 3.3. Depicted are dot plots overlaid with Box-whisker plots (median, inter-quartile range boxes (IQ), 1.5 × IQ whiskers) to visualize distribution of Ct values for CD22ΔE12 and actin transcripts as well as ΔCt values (Panel B), ΔΔCt values (Panel C) in primary leukemia cells from newly diagnosed patients with high-risk BPL (N=62), infant ALL (N=14), standard-risk BPL (N=36), and T-lineage ALL (N=16). Significant differences in ΔΔCt values were observed across the ALL sub-types (ANOVA, F3,124 = 25.1, P<0.0001) and all 3 BPL subtypes expressed significantly higher levels of CD22ΔE12 than the T-precursor subtype (Dunnett's post-hoc, P<0.0001 for High Risk, Standard Risk and Infant ALL versus T-precursor ALL). The positive control cells contained 2 copies of CD22 Δ E12 enabling copy number calculations for each sample using the formula, Copy number = ΔΔCt sample/-11.9 × 2, and depicted using the dot plot overlaid with the Box-Whisker plot (Panel C, lower subpanel). Median and inter-quartile copy number ranges for high-risk BPL, Infant ALL, standard-risk BPL and T-lineage ALL were 2.5 (2.07-2.82), 2.34 (2.16-2.57), 2.32 (1.68-2.86) and 0.66 (0.56-0.76) respectively. [A-C] Distribution of the data are depicted using an outlier Box-Whisker plot (JMP v10, SAS, Cary, NC). The vertical line within the box represents the median sample value, the boxes represent the 75th and 25th quantiles, and the whiskers represent the 3rd quartile + 1.5*(interquartile range) and 1st quartile - 1.5*(interquartile range) if outliers are observed, or upper and lower data point values if outliers are not observed.

We next examined the incidence of CD22ΔE12 in newly diagnosed pediatric ALL using quantitative RT-PCR. Our studies using quantitative real time RT-PCR on samples obtained from newly diagnosed 114 pediatric ALL patients (62 high-risk BPL, 36 standard risk BPL, 16 T-lineage ALL) and 14 infant B-precursor ALL patients demonstrated a very high incidence of CD22ΔE12 in both high-risk (89%; 55/62) and standard-risk (81%; 29/36) subsets of pediatric BPL and confirmed the presence of this genetic defect in 100% (14/14) of infant ALL cases (Figure 2B & C, Figure S5). By comparison, CD22ΔE12 was not detected in any of the 16 T-lineage ALL cases. Likewise,

Incidence of CD22ΔE12 in Adult B-lineage Lymphoid Malignancies

We then sought to determine if in the primary neoplastic cells from adult patients with lymphoid maligagncies, the CD22ΔE12-index values are lower than in normal B-cells. Notably, reductions in CD22ΔE12-index values were observed for 79% of CLL patients (N=578, P<0.0001) and 97% of MCL patients (N=38, P<0.0001). ANOVA of the these patient groups also yielded significant differences between groups (F4,1363 = 114.4, P<0.0001; Dunnett's post hoc P<0.0001 for CLL and MCL comparisons with normal, P=0.026 for FL versus normal and P=0.46 for DLBCL versus normal) (Figure S3B). We also used RT-PCR for detection and measurement of the abnormal CD22ΔE12-mRNA in CLL and MCL cells. As shown in Figure S6A&B, Z-138 CLL cells as well as MAVER MCL cells expressed CD22ΔE12-mRNA at levels comparable to those of BPL xenograft clones and the BPL cell line REH. These cells were also characterized by abundant expression of the truncated CD22ΔE12 protein (Figure S6C).

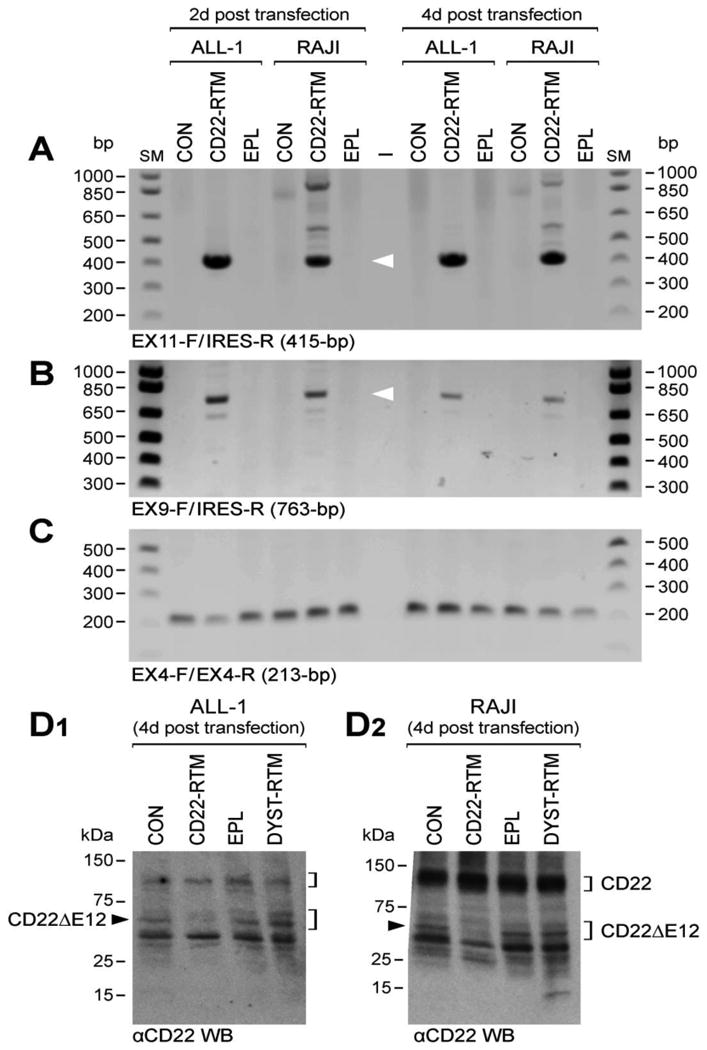

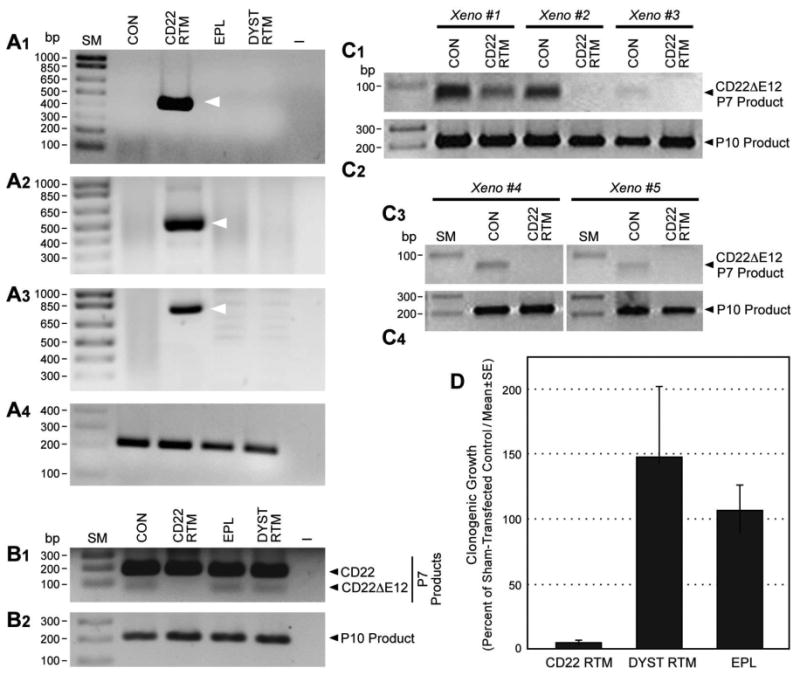

Correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect with a rationally designed unique CD22 RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM)

Gene-specific RTM plasmids have been shown to repair genetic defects by effecting sequence-specific trans-splicing between a naturally occurring mutated pre-mRNA target and RTM RNA9-19. We have constructed a CD22 RTM with a rationally designed anti-sense binding domain targeting a 60 nt complementary non-coding region close to the 5′ splice site of CD22 intron 9 that confers specificity by tethering the RTM to its target CD22 pre-mRNA (Figure 1, Figure 3, Figure 4). This RTM was first used to replace via trans-splicing the downstream mutation-rich segment of intron 12 and remaining segments of the mutant pre-mRNA in CD22ΔE12+ BCR-ABL+ BPL cell line ALL-1 and Burkitt's leukemia/B-ALL cell line RAJI with wildtype CD22 Exons 10-14. Trans-splicing would thereby prevent the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product and thereby prevent the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product (Figure 1). Successful transfection of ALL-1 cells (Figure 3A, Figure 4A.1) and RAJI cells (Figure 3A) was confirmed by RT-PCR amplification of a 415-bp RTM-specific RNA-segment. Figure 4A.2 depicts an agarose gel that shows the RT-PCR amplification of another 506-bp RTM-specific RNA-segment amplified by RT-PCR using a CD22 Exon 10 primer as forward primer and an RTM IRES primer as the reverse primer as a further confirmation of transfection shown in Figure 4A1. Successful completion of selective CD22 RTM-induced trans-splicing in ALL-1 cells (Figure 3B, Figure 4A3) and RAJI cells (Figure 3B) was confirmed by specifically amplifying a 763-bp trans-spliced mRNA segment that includes segments of both ALL1-derived Exon 9 and RTM-derived sequences. This was accomplished using RT-PCR with an Exon 9 forward primer and a reverse primer in the IRES sequence of the RTM, which is just downstream of Exon 14 (Figure 1). Neither PCR reaction yielded products in untransfected ALL-1/RAJI cells or ALL-1/RAJI cells transfected with control plasmids. In contrast, RT-PCR using the P10 primer set as a positive control of RNA integrity to amplify a 213-bp region (c.433–c.645) within Exon 4 of the CD22 cDNA that was present in both wildtype CD22 and CD22ΔE12 mRNA species and would not be affected by trans-splicing yielded PCR products in all ALL1 RNA samples examined (Figure 3C, Figure 4A.4). ALL-1 cells express both intact CD22 mRNA (major 182-bp RT-PCR product obtained with the P7 primer set) as well as truncated CD22ΔE12 mRNA (minor 63-bp RT-PCR product obtained with the P7 primer set). Transfection of ALL-1 cells with CD22 RTM (but not with 2 control plasmids) resulted in a selective depletion of truncated CD22ΔE12 transcript, as evidenced by disappearance of the CD22ΔE12-specific 63-bp RT-PCR product without depletion of the 213-bp PCR product obtained with the P10 primer set (Figure 4B1 & B2). Similar results were obtained using ALL xenograft cells derived from 5 different BPL cases in RTM transfection experiments (Figure 4 C1-C4): Transfection with CD22 RTM resulted in a significant decrease in CD22ΔE12 transcript levels in each case, as determined by RT-PCR using the P7 primer set to amplify a 182-bp region from Exon 11 to 13, without a decrease of the 213-bp PCR product obtained with the P10 primer set. Transfection of ALL-1 and RAJI cells with the CD22-RTM (but not EPL) also resulted in a selective depletion of the truncated CD22DE12 protein (but not the full-length CD22 protein), as determined by anti-CD22 Western blot analysis of protein samples extracted from lysates of transfected cells on d4 post transfection (Figure 3D1 and D2). Colony assays showed abrogation of clonogenic growth in RTM-transfected ALL-1 cells (CON: 1144± 44 colonies/250,000 cells; CD22-RTM: 0±0 colonies/250,000 cells; EPL: 1011±60 colonies/250,000 cells; P<0.0001). We next examined the effects of CD22 RTM on CD22ΔE12 transcript levels and in vitro clonogenicity of ALL xenograft cells derived from primary bone marrow specimens of 5 patients with BPL. Notably, blast colony formation by CD22 RTM-transfected ALL xenograft cells was reduced by 95% (T-test P value [CD22 RTM vs. Sham transfection] =1.0×10-11): The mean colony numbers in cultures of CD22 RTM transfected xenograft cells were reduced to 5.0±1.9% level when compared to the colony numbers in cultures of sham-transfected xenograft cells (Figure 4D). Neither the empty plasmid nor the dystrophin RTM caused a reduction of the clonogenicity of ALL xenograft cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 3. Correcting Aberrant Splicing of the Human CD22 Gene Using Splicesome-mediated RNA Trans-splicing Technology.

[A-C] RT-PCR analyses of ALL-1 and RAJI cells transfected with CD22 RTM vs. empty plasmid (EPL). Total RNA for the PCR was extracted 2d or 4 d after transfection with the CD22 RTM or EPL. [A] depicts an agarose gel that shows the RT-PCR amplification of a 415-bp RTM-specific RNA-segment amplified by RT-PCR using a CD22 exon 11 primer as forward primer (EX11-F) and the RTM IRES primer RTM-4494-5263 as a reverse primer (IRES-R), thereby confirming successful transfection of ALL-1 and RAJI cells with the CD22 RTM. [B] Successful completion of selective CD22 RTM-induced trans-splicing in ALL-1 cells was confirmed by specifically amplifying a 763-bp trans-spliced mRNA segment that includes segments of both ALL1-derived exon 9 and RTM-derived sequences via RT-PCR with an exon 9 forward primer (EX9-F) and a reverse primer in the IRES sequence of the RTM (IRES-R), which is just downstream of exon 14. hCD22E9-Fwd 5′-CAACCCTGACCTGTGAGAGC-3′/IRES-R 5′-AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′. Depicted is an agarose gel showing the RT-PCR products. [C] shows an agarose gel of the RT-PCR products obtained with the P10 primer set (EX4-F/EX4-R) that was used as a positive control of RNA integrity to amplify a 213-bp region (c.433–c.645) within Exon 4 of the CD22 cDNA. [D] Western blot analyses of ALL-1 and RAJI cells transfected with CD22 RTM vs. empty plasmid (EPL). [D1] and [D2] depict the anti-CD22 Western blots of proteins extracted from ALL-1 and RAJI cells 4d after transfection with CD22-RTM or EPL. In A-D, untransfected ALL-1 and RAJI cells also served as controls. CD22ΔE12 depletion causes cell death via apoptosis. Therefore, accurate RT-PCR and Western blot assays are not feasible beyond 4 d post transfection with the CD22-RTM.

Figure 4. Effects of Correcting Aberrant Splicing of the Human CD22 Gene Using Splicesome-mediated RNA Trans-splicing Technology.

[A & B] RT-PCR analyses of ALL1 cells transfected with CD22 RTM vs. control plasmids (i.e., EPL: empty plasmid; DYST RTM: an RTM targeting the dystrophin gene unrelated to CD22). Total RNA for the PCR was extracted 48 h after transfection with the CD22 RTM or control plasmids. A1 depicts an agarose gel that shows the RT-PCR amplification of a 415-bp RTM-specific RNA-segment amplified by RT-PCR using a CD22 exon 11 primer as forward primer and the RTM IRES primer RTM-4494-5263 as a reverse primer, thereby confirming successful transfection of ALL1 cells with the CD22 RTM. A2 depicts an agarose gel that shows the RT-PCR amplification of a 506-bp RTM-specific RNA-segment amplified by RT-PCR using a CD22 Exon 10 primer as forward primer and an RTM IRES primer as the reverse primer (hCD22E10-Fwd 5′-ATCCTCATCCTGGCAATCTG-3′ /IRES-R 5′- AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′) as a further confirmation of transfection shown in A1. Successful completion of selective CD22 RTM-induced trans-splicing in ALL-1 cells was confirmed by specifically amplifying a 763-bp trans-spliced mRNA segment that includes segments of both ALL1-derived exon 9 and RTM-derived sequences via RT-PCR with an exon 9 forward primer and a reverse primer in the IRES sequence of the RTM, which is just downstream of exon 14. hCD22E9-Fwd 5′-CAACCCTGACCTGTGAGAGC-3′/IRES-R 5′-AAGCGGCTTCGGCCAGTAAC-3′. A3 depicts an agarose gel showing the RT-PCR product. A4 shows an agarose gel of the RT-PCR products obtained with the P10 primer set that was used as a positive control of RNA integrity to amplify a 213-bp region (c.433–c.645) within Exon 4 of the CD22 cDNA. B1 depicts the RT-PCR products obtained with the P7 primer set to amplify a 182-bp region spanning from Exon 11 to 13 for detection of truncated CD22ΔE12 mRNA. B2 depicts the RT-PCR products obtained from the same RNA used in the experiment depicted in B1 upper panel with the P10 primer set that was used as a positive control of RNA integrity. ALL-1 cells express both intact CD22 mRNA (major 182-bp RT-PCR product obtained with the P7 primer set) as well as truncated CD22ΔE12 mRNA (minor 63-bp RT-PCR product obtained with the P7 primer set). Transfection with CD22 RTM depletes the 63-bp truncated CD22ΔE12 PCR product without affecting the P10 product levels. [C] Depicted are the RT-PCR products obtained using P7 and P10 primer sets from ALL xenograft cells derived from 5 different BPL cases transfected with CD22 RTM. [D] Depicted are bar graphs illustrating the effects of transfection with CD22 RTM vs. control plasmids on the clonogenic growth of ALL xenograft cells derived from 5 BPL patients.

Discussion

Our recent findings have implicated CD22ΔE12 arising from a splicing defect associated with homozygous intronic mutations as a previously undescribed pathogenic mechanism in human BPL5. CD22ΔE12 is the first reported genetic defect implicating a B-cell co-receptor in a human lymphoid malignancy and linking homozygous mutations of the CD22 gene to a human disease and also the first genetic defect implicating intronic mutations in the pathogenesis of leukemia. The abnormal CD22ΔE12 protein is encoded by a profoundly aberrant mRNA arising from a splicing defect that causes the deletion of exon 12 (c.2208-c.2327) (CD22ΔE12) and results in a truncating frameshift mutation. The splicing defect is associated with multiple homozygous mutations within a 132-bp segment of the intronic sequence between exons 12 and 13. These mutations cause marked changes in the predicted secondary structures of the mutant CD22 pre-mRNA sequences that affect the target motifs for the splicing factors hnRNP-L, PTB, and PCBP5,6. A number of pathogenic intronic mutations, including single point mutations have been linked to aberrant splicing and human disease19,20. Splicing is required for the expression of nearly all genes and is mediated by a complex of numerous interacting RNA-binding proteins. The splicing machinery can also be co-opted to effect repair or completely change the encoded sequence of a disease associated pre-mRNA by providing it with an alternative substrate, an RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM), to splice in trans-9-13 RTMs have 3 main elements, 1) an anti-sense binding domain (BD) which is the only feature that confers specificity by tethering the RTM to it's target pre-mRNA; 2) a 3′ and/or 5′ splice site; and 3) a coding sequence to be trans-spliced, which can re-write most of the targeted pre-mRNA by replacing one or numerous exons anywhere in a message. RNA trans-splicing molecules have achieved efficiencies exceeding 50% in trans-splicing endogenously expressed human papilloma virus sequences in SiHa cells (derived from a cervical cancer patient)21. Trans- splicing has restored 22% of normal chloride channel activity in cystic fibrosis patient cell/xenograft mice. This is ∼3 times the level of CFTR function found in some phenotypically normal humans12. All coding mutations within this 3-kb region of the human CFTR gene would have been corrected. Trans-splicing has restored factor VIII expression in a hemophilia A knock out mouse model, generating F8 levels above 20% of normal13. We and others have shown that RNA trans-splicing can rewrite genes that cause a wide range of diseases including spinal motor atrophy14, myotonic dystrophy15, epidermolysis bullosa16,22, cancer17,18 and sickle cell anemia23. More recently, mRNA and protein expression were corrected in the brains of a mouse model of tau mis-splicing by RNA trans-splicing24. These results validated the potential of RNA trans-splicing to correct tau mis-splicing and provide a framework for its therapeutic application to neurodegenerative conditions as well as other diseases linked to aberrant RNA processing. In the present study, we have identified a novel RTM that efficiently and specifically repairs CD22ΔE12 and generates potent anti-neoplastic activity against the aggressive human BCR-ABL+ BPL cell line ALL-1 as well as the Burkitt's lymphoma cell line RAJI5,6. The rationally designed unique BD of this RTM was capable of promoting the trans-splicing with the relatively large CD22 Intron 9 in both cell lines.

Notably, the described CD22-RTM exhibited potent anti-neoplastic activity not only against human CD22ΔE12+ leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, but also against very aggressive in vivo clonogenic leukemia xenograft cells derived from patients with BPL. The observation that a CD22-RTM can be used to effectively prevent the generation of the cis-spliced aberrant CD22ΔE12 product in human BPL cells and thereby abrogate the CD22ΔE12-endowed clonogenicity suggests that the correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect with a trans-splicing strategy may also have potential to prevent or treat BPL before the development of overt leukemia.

The described trans-splicing strategy with a rationally designed CD22-RTM offers several advantages over “traditional” gene therapy approaches (reviewed in Mitchell)9: (i) Size: Several thousand base pairs can be repaired with one trans-splicing construct. This is smaller and easier to deliver than a complete cDNA with appropriate regulatory elements; (ii) Regulation: A corrected mRNA is created from the natural gene, which is under the endogenous regulation of the cell. Thus, the corrected protein should be produced in the right place, time and amount. If stem cells are transduced, the recapitulation of endogenous regulation may be critical because stem cells do not normally express proteins, such as CD22 that are made in a lineage- specific and developmentally-regulated manner. The importance of well-regulated gene expression was highlighted by a study using RNA trans-splicing to correct a CD40 ligand (hyper-IgM X-linked immunodeficiency) knock out mouse model14. Previous reports had shown the feasibility of using CD40 ligand cDNA transfer in bone marrow cells to correct the immunodeficiency; however, treated mice developed lymphomas33. Furthermore, in the case of disorders caused by gain-of-function mutations, such as CD22ΔE12, trans-splicing converts the expression of a mutant mRNA to wild-type, which should produce a greater benefit than just blocking expression of the mutant.

The expression of CD22 on leukemic B-cell precursors has motivated the development and clinical testing of CD22-directed MoAb, recombinant fusion toxins, and antibody-drug conjugates as therapeutic agents against BPL in children.25-27 However, these therapeutic modalities all target the surface epitopes of CD22 and do not discriminate between normal B-cells expressing intact CD22 and BPL cells expressing CD22ΔE12. Due to the presence of CD22 on normal human B-cells and B-cell precursors, lymphotoxicity with reduced B-cell numbers and possible hypogammaglobulinemia with an increased risk of infections would be anticipated side effects of CD22 directed MoAb and MoAb based therapeutics in clinical settings. In contrast, RNA therapeutics, such as the CD22-RTM reported here, targeting CD22ΔE12 would only kill BPL cells while leaving normal B-cell precursors and B-cells with an intact CD22 encoded by a wildtype CD22 mRNA unharmed.

Supplementary Material

Insight, Innovation, Integration.

CD22 exon 12 deletion (CD22ΔE12) is a characteristic genetic defect of therapy-refractory clones in pediatric B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BPL), the most common form of childhood cancer. We provide experimental evidence that the correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in human CD22ΔE12+ BPL cells using a rationally designed CD22 RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM) caused a pronounced reduction of their clonogenicity. The potent anti-leukemic activity of this RTM against ALL xenograft clones derived from CD22ΔE12+ leukemia patients provides the preclinical proof-of-concept that correcting the CD22ΔE12 defect with rationally designed CD22 RTMs may help develop successful treatments for high-risk and relapsed BPL patients who are in need for therapeutic innovations.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported in part by DHHS grants R43CA177067 (L.M., F.M.U) P30CA014089 (F.M.U) from the National Cancer Institute and the Keck School of Medicine Regenerative Medicine Initiative Award (F.M.U). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by Nautica Triathalon and its producer Michael Epstein (F.M.U), Couples Against Leukemia Foundation (F.M.U) and Saban Research Institute Merit Awards (F.M.U). We thank the technicians of the Uckun lab, including Rita Ishkhanian, Anoush Shahidzadeh, Ingrid Cely, and Martha Arellano for their assistance throughout the study. We also thank Mrs. Parvin Izadi of the CHLA Bone Marrow Laboratory, for her assistance.

Footnotes

Insight, Innovation, Integration. CD22 exon 12 deletion (CD22ΔE12) is a characteristic genetic defect of therapy-refractory clones in pediatric B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BPL), the most common form of childhood cancer. We provide experimental evidence that the correction of the CD22ΔE12 genetic defect in human CD22ΔE12+ BPL cells using a rationally designed CD22 RNA trans-splicing molecule (RTM) caused a pronounced reduction of their clonogenicity. The potent anti-leukemic activity of this RTM against ALL xenograft clones derived from CD22ΔE12+ leukemia patients provides the preclinical proof-of-concept that correcting the CD22ΔE12 defect with rationally designed CD22 RTMs may help develop successful treatments for high-risk and relapsed BPL patients who are in need for therapeutic innovations.

Contribution: All authors have made significant and substantive contributions to the study. All authors reviewed and revised the paper. F.M.U performed the biological studies. S.Q. performed the bioinformatics and statistical analyses. H.M performed the PCR tests. G.H.R. participated in the design of the study and provided deidentified patient specimens. L.M. designed and constructed the CD22-RTM.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no current competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tedder TF, Poe JC, Haas KM. CD22: a multifunctional receptor that regulates B lymphocyte survival and signal transduction. Adv Immunol. 2005;88:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)88001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poe JC, Tedder TF. CD22 and Siglec-G in B cell function and tolerance. Trends in Immunology. 2012;33(8):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller J, Nitschke L. The role of CD22 and Siglec-G in B-cell tolerance and autoimmune disease. Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2014) 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pui CH, Mullighan CG, Evans WE, Relling MV. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: where are we going and how do we get there? Blood. 2012;120:1165–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-378943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uckun FM, Goodman P, Ma H, Dibirdik I, Qazi S. CD22 Exon 12 Deletion as a Novel Pathogenic Mechanism of Human B-Precursor Leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16852–16857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007896107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma H, Qazi S, Ozer Z, Gaynon P, Reaman GH, Uckun FM. CD22 Exon 12 deletion is a characteristic genetic defect of therapy-refractory clones in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(1):89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uckun FM, Qazi S, Ma H, Yin L, Cheng JJ. A rationally designed nanoparticle for RNA interference therapy in B-lineage lymphoid maligancies. EBioMedicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.10.013. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uckun FM, Ma H, Zhang J, Ozer Z, Dovat S, Mao C, Ishkhanian R, Goodman P, Qazi S. Serine phosphorylation by SYK is critical for nuclear localization and transcription factor function of Ikaros. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18072–18077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209828109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell LG, McGarrity G. Progress & Prospects: Reprograming Gene Expression by Trans- splicing. Gene Therapy. 2005;12(20):1477–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302596. PMID: 16121205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahara M, Pergolizzi RG, Kobayashi H, Krause A, Luettich K, Lesser ML, Crystal RG. Trans- splicing repair of CD40 ligand deficiency results in naturally regulated correction of a mouse model of hyper- IgM X-linked immunodeficiency. Nat Med. 2004;10:835–41. doi: 10.1038/nm1086. PMID: 15273748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wally V, Klausegger A, Koller U, Lochmüller H, Krause S, Wiche G, Mitchell LG, Hintner H, Bauer JW. 5′ Trans-Splicing Repair of the PLEC1 Gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(3):568–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701152. PMID: 17989727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Jiang Q, Mansfield SG, Puttaraju M, Zhang Y, Zhou W, Garcia-Blanco MA, Mitchell LG, Engelhardt JF. Functional Restoration of CFTR Chloride Conductance in Human CF Epithelia by Spliceosome-mediated RNA. Trans-splicing Nat Biotech. 2002;20(1):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-47. PMID: 11753361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao H, Mansfield SG, Bartel RC, Hiriyanna S, Mitchell LG, Garcia-Blanco MA, Walsh CE. Phenotype correction of hemophilia A mice by spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing. Nat Med. 2003;9:1015–1019. doi: 10.1038/nm900. PMID: 12847523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coady TH, Shababi M, Tullis GE, Lorson CL. Restoration of SMN function: Delivery of a trans-splicing RNA re-directs SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Ther. 2007;15(8):1471–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen HY, Kathirvel P, Yee WC, Lai PS. Correction of dystrophia myotonica type 1 pre-mRNA transcripts by artificial trans-splicing. Gene Therapy. 2009;16(2):211–7. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.150. PMID: 18923454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallinger G, Puttaraju M, Mitchell LG, Yancey KB, Yee C, Klausegger A, Hintner H, Bauer JW. Development of spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT) for the correction of inherited skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12(1):37–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2003.120105.x. PMID: 12631245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puttaraju M, Jamison SF, Mansfield SG, Garcia-Blanco MA, Mitchell LG. Spliceosome mediated targeted Trans- splicing, a new tool for gene therapy and RNA repair. Nat Biotech. 1999;17(3):246–252. doi: 10.1038/6986. PMID: 10096291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koller U, Wally V, Bauer JW, Murauer EM. Considerations for a Successful RNA Trans-splicing Repair of Genetic Disorders. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2014 Apr 8;3:e157. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venables JP. Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7647–7654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1910. PMID:15520162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baralle D, Baralle M. Splicing in action: assessing disease causing sequence changes. J Med Genet. 2005;42:737–748. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029538. PMID: 16199547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng ZM, Baker CC. Papilloma genome structure, expression and post-transcriptional regulation. Front Biosci. 2006 Sep 1;11:2286–2302. doi: 10.2741/1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murauer EM, Gache Y, Gratz IK, Klausegger A, Muss W, Gruber C, Meneguzzi G, Hintner H, Bauer JW. Functional Correction of Type VII Collagen Expression in Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2011 Jan;131(1):74–83. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.249. PMID: 20720561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kierlin-Duncan MN, Sullenger BA. Using 5′ PTMs to repair mutant μ-globin transcripts. RNA. 2007;13:1–11. doi: 10.1261/rna.525607. PMID: 17556711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avale ME, Rodríguez-Martín T, Gallo JM. Trans-splicing correction of tau isoform imbalance in a mouse model of tau mis-splicing. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Mar 25; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt108. [Epub ahead of print] PMID:23459933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raetz EA, Cairo MS, Borowitz MJ, Lu X, Devidas M, Reid JM, et al. Reinduction chemoimmunotherapy with epratuzumab in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children, adolescents and young adults: results from Children's Oncology Group (COG) study ADVL04P2. Blood. 2013;122:355. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, Jorgensen J, Jabbour E, Kebriaei P, Rytting M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin, an anti-CD22-calecheamicin conjugate, for refractory and relapsed acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Cruz OJ, Uckun FM. Novel mAb-based therapies for leukemia. In: “Monoclonal Antibodies in Oncology”. In: Uckun FM, editor. Future Medicine. Future Medicine Ltd; London: 2013. pp. 54–77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.