Abstract

Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated human fungal pathogen and can cause a range of mucosal and systemic infections in immunocompromised individuals. Morphogenesis, the ability to undergo a reversible transition from budding yeast to elongated filaments, is an essential virulence trait. The yeast-to-filament transition is associated with expression of genes specifically important for filamentation as well as other virulence-related processes, and is controlled, in part, by the key transcriptional regulators Nrg1 and Ume6. Both of these regulators are themselves controlled at the transcriptional level by filament-inducing environmental cues, although little is known about how this process occurs. In order to address this question and determine whether environmental signals regulate transcription of UME6 and NRG1 via distinct and/or common promoter elements, we performed promoter deletion analyses. Strains bearing promoter deletion constructs were induced to form filaments in YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C, Spider medium (nitrogen and carbon starvation) and/or Lee’s medium pH 6.8 (neutral pH) and reporter gene expression was measured. In the NRG1 promoter we identified several distinct condition-specific response elements for YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C and Spider medium. In the UME6 promoter we also identified response elements for YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C. While a few of these elements are distinct, others overlap with those which respond to Lee’s pH 6.8 medium. Consistent with UME6 possessing a very long 5’ UTR, many response elements in the UME6 promoter are located significantly upstream from the coding sequence. Our data indicate that certain distinct condition-specific elements can control expression of C. albicans UME6 and NRG1 in response to key filament-inducing environmental cues. Because C. albicans encounters a variety of host microenvironments during infection, our results suggest that UME6 and NRG1 expression can be differentially modulated by multiple signaling pathways to control filamentation and virulence in vivo.

Introduction

Candida albicans is an opportunistic human fungal pathogen and a significant cause of disease in immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS patients, organ transplant recipients and cancer patients on chemotherapy [1–4]. It is estimated that 70% of women will experience at least one episode of vulvovaginal candidiasis in their lifetime [5, 6]. In addition to cutaneous and mucosal infections, C. albicans can disseminate and cause life-threatening, systemic infections [1, 7]. With a mortality rate of ~40%, Candida species are the fourth leading cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in the U.S. [8, 9].

While several traits contribute to the pathogenesis of C. albicans, morphogenesis, the ability to transition between oval-shaped budding yeast cells and filaments (elongated cells attached end-to-end), is an essential virulence property of this organism [1, 7, 10]. Filamentation plays an important role in tissue invasion, cell damage, biofilm formation, thigmotropism as well as the ability to escape from and lyse macrophages [11–17]. Furthermore, genes involved in the physical process of filamentous growth are co-regulated with genes important for other virulence processes, including adhesion and degradation of host cell membranes [18, 19]. Several previous studies have clearly demonstrated that the ability of C. albicans to undergo a reversible transition from yeast to filaments is required for virulence in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis [13, 15, 20–24].

A variety of host environmental cues are known to trigger the C. albicans yeast-to-filament transition, including 37°C, serum, human hormones, starvation and neutral pH [25–27]. These host conditions activate signal transduction pathways (eg: MAP kinase and cAMP-PKA pathways) resulting in the induction of filament-specific genes [28]. Several C. albicans transcriptional regulators are known to play critical roles in this process. Importantly, two of these regulators, Nrg1 and Ume6, are themselves controlled at the transcriptional level by filament-inducing conditions. Nrg1, a zinc finger DNA-binding protein, functions (via recruitment of the Tup1 corepressor) as a key transcriptional repressor of filament-specific genes under non-filament-inducing conditions [21, 22]. In the presence of certain filament-inducing conditions (eg: growth in serum at 37°C) the NRG1 transcript is down-regulated, causing the expression of filament-specific genes. In addition, the Nrg1 repressor is transiently displaced from hyphal-specific promoters via activation of the cAMP-PKA pathway in the presence of serum at 37°C [29]. The nrg1Δ/Δ mutant is avirulent and constitutive high-level expression of NRG1 has also been shown to block the yeast-to-filament transition, leading to highly attenuated virulence in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis [15, 21, 22].

Ume6, also a zinc finger DNA-binding protein, is a filament-specific transcriptional regulator that is required for hyphal extension [30]. A variety of different environmental filament-inducing conditions, including growth at 37°C in the presence of serum, Spider medium and Lee’s medium, pH 6.8 (neutral pH), are known to induce the UME6 transcript. UME6 is also a downstream target of multiple filamentous growth transcriptional regulators [31]. Both the level and duration of UME6 expression are important for determining C. albicans morphology and Ume6 protein stability is controlled by both oxygen- and CO2-sensing pathways [24, 32]. The ume6Δ/Δ mutant is attenuated for virulence and constitutive high-level expression of UME6 increases hyphal formation in vivo and is sufficient to promote virulence in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis [24, 30]. We have previously shown that both NRG1 and UME6 function together in a feedback loop to promote filament-specific gene expression in the presence of strong filament-inducing conditions [30].

While the critical roles that both UME6 and NRG1 play in regulating both the C. albicans yeast-filament transition and virulence have been well-characterized, considerably less is known about the exact mechanism(s) by which host environmental signals control expression of these key regulators at the transcriptional level. In this study we characterize the promoters of both NRG1 and UME6 and identify elements that respond to specific filament-inducing conditions. We also determine the extent to which these elements and, by inference, the upstream signaling pathways which target these elements, overlap. Overall, our results provide new and important information about how environmental cues, similar to those encountered in the host, regulate the expression of two key transcription factors that govern filamentation and virulence in the major human fungal pathogen C. albicans.

Materials and Methods

Media and growth conditions

YEPD (yeast-extract peptone dextrose) medium at 30°C was used as a standard non-filament-inducing condition [33]. Preparation of Spider and Lee’s media were performed as described previously [34, 35]. Induction of filamentation by growth in YEPD + 10% serum at 37°C, Spider medium at 30°C and Lee’s medium pH 6.8 at 30°C was conducted as described previously [30] with modifications. Strains were grown overnight in YEPD at 30°C to OD600 ~ 4.0 and then diluted 1:10 into pre-warmed YEPD + 10% serum at 37°C and 1:20 into Spider medium at 30°C. For Lee’s medium inductions, 10 mL of an overnight culture of cells grown in YEPD at 30°C was centrifuged, washed and resuspended in 5 mL 1X PBS. 2.5 mL of this cell suspension was inoculated into pre-warmed Lee’s pH 6.8 or Lee’s pH 4.5 medium at 30°C. Cells were harvested 30 minutes following induction in serum medium at 37°C, 6 hours following induction in Spider medium at 30°C and 1 hour following induction in Lee’s pH 6.8 medium for total RNA isolation. To determine the effect of farnesol on lacZ reporter gene expression, strains were grown overnight in YEPD medium at 30°C to OD600 ~ 4.0. Cells were then diluted 1:10 into pre-warmed YEPD at 30°C in the presence and absence of 40 μM farnesol (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Aliquots of cells were harvested from both the initial overnight culture as well as the diluted cultures (30 minutes following dilution) for RNA extraction.

Strain and DNA constructions

NRG1 promoter deletion strains were constructed as follows: varying regions of the NRG1 upstream intergenic region were amplified by PCR from C. albicans SC5314 genomic DNA using primers 1–16 (please see S1 Table and S2 Table for complete listings of strains and primers, respectively, used in this study). PCR products were digested with PstI-XhoI and cloned into plasmid placbasal [36]. The resulting promoter fragment-placbasal constructs were linearized at RPS1 by digestion with StuI and transformed into strain CAI4 to generate the NRG1 promoter deletion strains. The pUME64.9–7 kb UR—lac, pUME64.9–6 kb UR—lac, pUME64–6 kb UR—lac and pUME63–6 kb UR—lac plasmids were constructed as follows: each respective region of the UME6 upstream intergenic region was amplified by PCR using primers 20, 21, and 27–29. PCR products were digested with PstI-SphI and cloned into plasmid placbasal. To generate the 5.5 kb and 5 kb UME6 promoter deletion strains, regions from -1 bp to -2541 bp, -632 bp to -5494 bp and -632 bp to -4976 bp were amplified by PCR with primer sets 17/19, 24/25 and 25/26, respectively. All three fragments were digested with PstI-HindIII and cloned separately into pBS [37]. The -1 bp to -2077 bp fragment was released from pBS by digesting with HindIII-SphI and the -2077 bp to -5494 bp and -2077 bp to -4976 bp fragments were released from pBS by digesting with PstI-HindIII. A 3-piece ligation was used to clone the -1 bp to -2077 bp fragment and -2077 bp to -5495 bp fragment into plasmid placbasal to generate the pUME65.5 kb UR-lac plasmid. This method was also used to clone the -1 bp to -2077 bp fragment and -2077 bp to -4976 bp fragment into plasmid placbasal to generate the pUME65 kb UR—lac plasmid. The pUME67 kb UR—lac plasmid was constructed by amplifying the following fragments by PCR: -1801 bp to -5824 bp with primers 18/23 and -5491 bp to -7009 bp with primers 21/22. The -1 bp to -2077 bp fragment was prepared as described above. The fragment from -1801 bp to -5824 bp was digested with XhoI-HindIII and cloned into pBS and the fragment from -5491 bp to -7009 bp was digested with PstI-XhoI and cloned into pBS separately. The fragments from -2077 bp to -5808 bp and from -5808 bp to -7009 bp were released from pBS by XhoI-HindIII and PstI-XhoI digests, respectively. A 4-piece ligation was used to clone the three fragments generated above into placbasal to create plasmid pUME67 kb UR—lac. Plasmid pUME66kb UR—lac has been described previously [38]. All UME6 promoter deletion plasmids and the plac plasmid were linearized at RPS1 by digestion with StuI and transformed into strain CAI4 to generate the UME6 promoter deletion strains. All promoter fragments were sequenced prior to transformation into strain CAI4. Integration events were confirmed by whole-cell PCR using primers which flank the integration sites.

RNA preparation

RNA for qRT-PCR analysis was prepared as described previously [38].

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

cDNA for qRT-PCR analysis was prepared from total RNA as described previously [38], except that DNase from Life Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA) was used. qRT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously [38] using primer pairs 30/31 for lacZ and 32/33 for ACT1 with an annealing temperature of 57.4°C. The Pfaffl method was used to normalize expression levels of lacZ to those of an internal ACT1 control[39]. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in biological duplicate and technical duplicate. Values shown indicate mean ± SEM.

Results

Defining the NRG1 and UME6 promoter regions

In order to identify the NRG1 promoter, we cloned 902 bp, 2.1 kb and 2.9 kb fragments of the NRG1 upstream intergenic region in a Streptococcus thermophilus lacZ reporter construct [36] which was subsequently integrated at the C. albicans RPS1 locus. Each strain was grown under both non-filament-inducing (YEPD at 30°C) as well as strong filament-inducing (YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C) conditions. We observed the strongest level of lacZ down-regulation (8-fold) in response to filament induction with the strain containing the 2.9 kb NRG1 upstream intergenic region reporter construct (Fig. 1A). This level of NRG1 down-regulation was similar, if not slightly greater than, that observed with the natural transcript upon serum and temperature induction [18, 40]. In addition, an in silico analysis of the NRG1 3 kb upstream region using Transcription Element Search Software (www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess) (default parameters) [41] identified two putative binding sites each for Rim101, a pH-responsive transcriptional regulator of filamentous growth, and Cph1, a regulator of C. albicans mating and morphogenesis. Previous studies have also identified binding sites in this region for other transcriptional regulators of morphogenesis including Ndt80 and Efg1 [42, 43]. Taken together, these results suggest that the NRG1 promoter is located within the 2.9 kb upstream region.

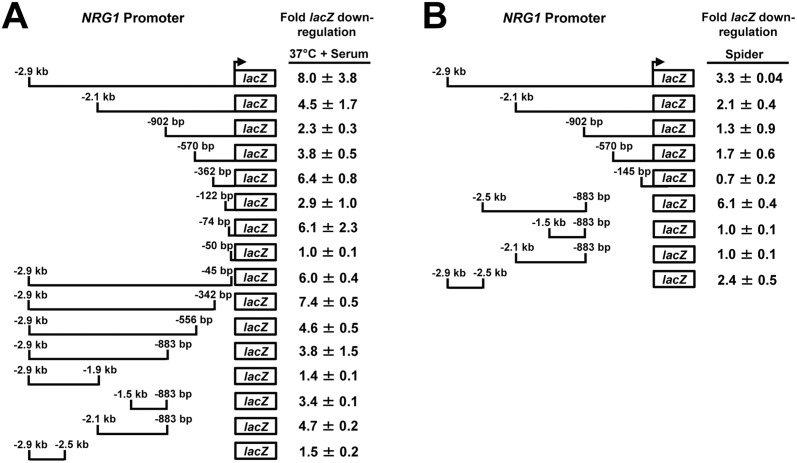

Fig 1. Deletion analysis of the NRG1 promoter identifies specific response elements for serum at 37°C and Spider.

Strains bearing the indicated NRG1 promoter-lacZ reporter constructs were grown under both non-filament-inducing (YEPD at 30°C) and filament-inducing (YEPD + 10% serum at 37°C or Spider at 30°C) conditions. Cells were harvested from both non-inducing and filament-inducing cultures for total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis. For the serum and temperature induction experiment (A) cells were harvested at the 30 minute post-induction time point and for the Spider induction experiment (B) cells were harvested at the 6 hr. post-induction time point. lacZ expression was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to ACT1 levels. Fold down-regulation of lacZ was determined by dividing normalized lacZ values obtained from cells grown under non-filament inducing conditions by normalized lacZ values obtained from cells induced to form filaments under each condition.

We have recently demonstrated that a 6 kb UME6 upstream region is required for C. albicans filamentation in response to serum at 37°C [38]. In addition, a fragment containing this region was sufficient to direct strong activation of the heterologous S. theromphilus lacZ reporter in response to growth in serum at 37°C. These results suggested that critical UME6 promoter elements are located in this region. However, to ensure that we did not overlook important, but non-essential UME6 promoter elements, we conducted an in silico analysis (as described above) for 7 kb of the UME6 upstream intergenic region and identified putative binding sites for a variety of key C. albicans filamentous growth transcriptional regulators including Rim101, Cph1 and Fkh2. Results of this analysis are consistent with those of a previous study showing that cph1Δ/Δ and fkh2Δ/Δ deletion strains are defective for UME6 induction in response to hyphal-inducing conditions [31]. Previous studies using ChIP-Chip and DNA tiling array analysis have also described binding sites for Ndt80, Efg1, Nrg1, Brg1 and Hms1 in the UME6 upstream region [42–45]. Importantly, several of the binding sites were located in the 6 to 7 kb UME6 upstream region. In addition, a number of the factors which bind to these sites have been shown to control UME6 expression [30, 31, 44, 45]. We have also recently demonstrated that the UME6 transcript has an exceptionally long 3 kb 5’ UTR which functions in translational inhibition [38]. These previous results, combined with our in silico analysis, suggest that the UME6 promoter is located in the 7 kb upstream region.

Identification of filament condition-specific response elements in the NRG1 promoter

In order to determine which elements in the NRG1 promoter are important for controlling expression in response to specific filament-inducing conditions, we conducted a promoter deletion analysis. Various deletions of the NRG1 promoter were fused to a S. thermophilus lacZ reporter [36] and integrated at the C. albicans RPS1 locus. lacZ expression was measured using qRT-PCR under both non-inducing conditions (YEPD at 30°C) as well as several known filament-inducing conditions. Time points used to harvest cells for each filament-inducing condition used in the deletion analyses described in this study were specifically chosen to observe maximal transcriptional effects (ie: NRG1 down-regulation and UME6 induction) based on pilot experiments.

To examine the response to serum and temperature, strains carrying NRG1 promoter deletions were induced to form filaments in YEPD + 10% serum at 37°C. As noted previously, we observed ~8-fold down-regulation of lacZ expression in the reporter strain carrying the full-length -2.9 kb NRG1 promoter fragment in response to growth in serum at 37°C (Fig. 1A). In general, 5’ deletions of the NRG1 promoter to the -122 bp position caused mild reductions in the level of down-regulation. Deletion of the -362 bp to -122 bp region led to a significant decline in lacZ down-regulation suggesting the presence of a serum and temperature responsive negative element. However, a deletion from -122 bp to -74 bp led to enhanced lacZ repression in response to 37°C + serum, indicating that the deleted sequence may contain a positive element. Importantly, -74 bp of the NRG1 promoter was the minimum region necessary to down-regulate the lacZ reporter in response to 37°C + serum. The -50 bp promoter did not drive basal lacZ expression under non-inducing conditions, which suggested that the region from -50 bp to -74 bp contains a negative response element. We also determined, using 5’ and 3’ NRG1 promoter deletion constructs, that the region between -883 bp and -1.5 kb contains another key temperature- and serum-responsive negative element (Fig. 1A).

In order to identify elements important for down-regulation of NRG1 in response to nitrogen and carbon starvation, strains bearing NRG1 promoter deletion constructs were induced to form filaments in Spider medium at 30°C. These strains were also grown under non-inducing conditions, YEPD at 30°C, as a control. We observed that the full-length 2.9 kb NRG1 promoter down-regulated lacZ expression ~3.3-fold in response to growth in Spider medium at 6 hrs. (Fig. 1B). Spider is a weaker filament-inducing condition and the 6 hr. time point was chosen for further analysis because the greatest NRG1 down-regulation was observed at this post-induction time point. While a 5’ deletion containing 2.1 kb of the NRG1 promoter directed ~2.1-fold lacZ down-regulation, additional 5’ promoter deletions were unable to significantly reduce lacZ expression. We next used 3’ NRG1 promoter deletion strains to further localize elements important for NRG1 down-regulation in response to Spider medium (Fig. 1B). The region from -883 bp to -2.5 kb down-regulated lacZ expression ~6.1-fold. However, other promoter deletion constructs in that region (-883 bp to -2.1 kb and -883 bp to -1.5 kb) did not significantly down-regulate lacZ expression. Interestingly, we also observed that the -2.5 kb to -2.9 kb region was sufficient to direct > 2-fold lacZ down-regulation. Taken together, these results suggest that the NRG1 promoter region from -2.1 kb to -2.9 kb contains two Spider condition-specific negative elements; the first element is located between -2.1 kb and -2.5 kb and the second element is between -2.5 kb and -2.9 kb.

Response of the NRG1 promoter to hyphal shock

We have previously described a “hyphal shock” phenomenon whereby C. albicans cells can be induced to form filaments when diluted from a saturated overnight culture into non-inducing media, such as YEPD at 30°C [18]. In our reporter assays we routinely harvest cells for RNA preparation prior to induction at the zero hour time point to examine for this effect. Interestingly, while the full-length NRG1 promoter did not show down-regulation in response to dilution in YEPD at 30°C, we did observe that certain NRG1 promoter deletion constructs showed down-regulation of lacZ expression at 30 minutes growth in YEPD at 30°C following dilution from the zero time point overnight culture (Fig. 2). Because hyphal shock is believed to be mediated by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule that has specifically been shown to control Nrg1 protein stability [46], we decided to further investigate this phenomenon and define “hyphal shock”-sensitive regions within the NRG1 promoter. Unlike the full-length 2.9 kb NRG1 promoter reporter, we observed that the -883 bp to -2.9 kb NRG1 promoter deletion reporter was particularly sensitive to dilution into fresh YEPD, resulting in ~7-fold down-regulation of lacZ. This finding suggested that the -1 bp to -883 bp region is important for activation of NRG1 in response to hyphal shock. In contrast, both the -1.9 kb to -2.9 kb and -2.5 kb to -2.9 kb fragments directed ~2–4-fold lacZ down-regulation when cells were diluted in fresh medium, suggesting that the -883 bp to -1.9 bp and -2.5 kb to -2.9 kb regions are important for repression of NRG1 in response to hyphal shock.

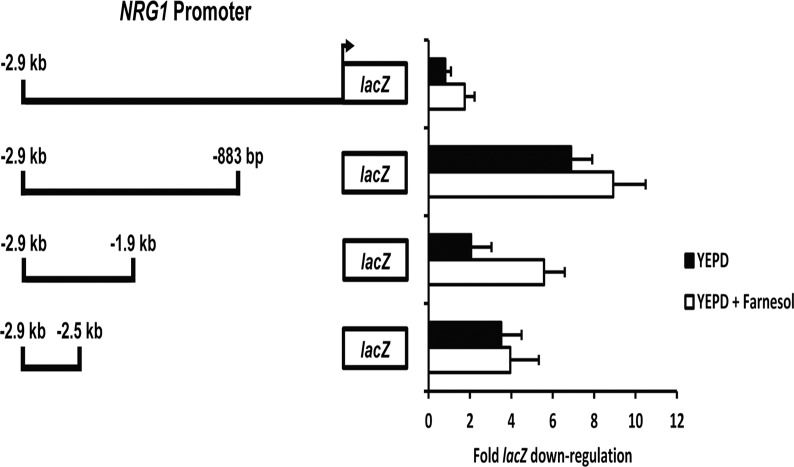

Fig 2. Identification of hyphal shock response elements in the NRG1 promoter.

Strains bearing the indicated NRG1 promoter-lacZ reporter constructs were grown overnight under non-inducing conditions (YEPD at 30°C) and diluted into fresh YEPD medium in the presence or absence of 40 μM farnesol at 30°C. Cells were harvested from both the overnight culture (zero time point) as well as at 30 minutes following dilution for total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis. lacZ expression values were determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to ACT1 levels. Fold down-regulation of lacZ was determined by dividing normalized lacZ values from cells grown overnight under non-filament inducing conditions (zero time point) by normalized lacZ values from cells diluted into fresh YEPD or YEPD plus 40 μM farnesol.

As discussed above, one hypothesis is that C. albicans filamentation which occurs during hyphal shock is the result of a rapid release from filament inhibition by quorum-sensing molecules, such as farnesol [47]. Farnesol inhibits cAMP signaling, thus favoring yeast growth [29, 48]. Dilution of cells at higher optical densities into fresh media would also dilute overall levels of farnesol and other small molecules. We speculated that the sudden loss of farnesol-mediated inhibition of the cAMP pathway might affect transcript levels directed by the NRG1 promoter. In order to test this hypothesis, strains carrying NRG1 promoter deletions were grown overnight in YEPD at 30°C and diluted into fresh YEPD at 30°C in the presence and absence of 40 μM farnesol. Cells were harvested following 30 minutes growth for total RNA isolation. Interestingly, we observed that growth in farnesol did not prevent down-regulation of lacZ expression directed by the NRG1 promoter deletion constructs (Fig. 2). These results suggest that farnesol-mediated inhibition of the cAMP pathway does not play an important role in regulating the NRG1 promoter response to hyphal shock.

Identification of filament condition-specific regulatory regions in the UME6 promoter

Similar to NRG1, UME6 also encodes a transcription factor which itself is controlled at the transcriptional level by filament-inducing conditions [30, 31]. In order to identify DNA elements in the UME6 promoter important for filament condition-specific control, various UME6 promoter deletions were fused to a lacZ reporter and integrated at the C. albicans RPS1 locus. We examined lacZ expression of these strains using qRT-PCR when cells were grown under several known filament-inducing conditions.

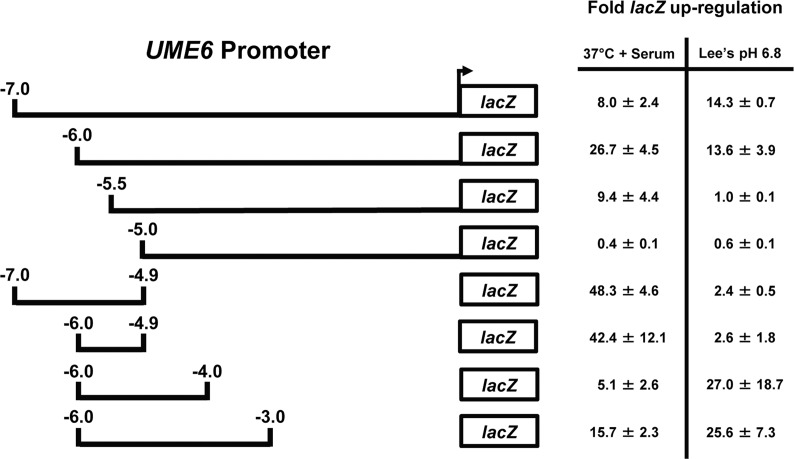

We first sought to identify UME6 promoter elements important for transcriptional induction in response to growth in 10% serum at 37°C. Cells were harvested 30 minutes following filament induction under these conditions and total RNA was prepared for qRT-PCR analysis. We previously observed that a 6 kb UME6 promoter fragment directed strong (~27-fold) induction of lacZ expression in response to serum and temperature [38]. Interestingly, increasing the UME6 promoter length to 7 kb reduced lacZ up-regulation to ~8-fold, suggesting that this region contains a serum and temperature-responsive negative element (Fig. 3). A 5’ UME6 promoter deletion analysis indicated that lacZ induction was abolished in the strain expressing the 5.0 kb, but not the 5.5 kb UME6 promoter construct, suggesting that this region is required for the serum and temperature response. In addition, induction was decreased in the strain expressing the 5.5 kb vs. 6.0 kb UME6 promoter indicating the presence of a positive response element in this region. We also examined the response of 3’ UME6 promoter deletions during a serum and temperature induction. A deletion strain bearing -4.0 kb to -6.0 kb of the UME6 promoter generated a low level induction of lacZ (~5-fold) (Fig. 3). An additional deletion of the -4 kb to -4.9 kb region resulted in ~40-fold up-regulation of lacZ expression. This result suggests that the -4 kb to -4.9 kb UME6 promoter region contains a negative element for serum and temperature. Finally, the -3.0 kb to -6.0 kb region showed greater induction compared to the -4.0 kb to -6.0 kb region suggesting the presence of a serum- and temperature-responsive positive element between -3.0 kb and -4.0 kb.

Fig 3. Deletion analysis of the UME6 promoter identifies condition-specific response elements.

Strains bearing the indicated UME6 promoter-lacZ reporter constructs were grown under non-inducing conditions (YEPD at 30°C for the serum and temperature induction experiment and Lee’s pH 4.5 medium for the neutral pH induction experiment) and the indicated filament-inducing conditions. Cells were harvested (at 30 minutes for the serum and temperature induction experiment and at 1 hour for the neutral pH induction experiment) for total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis. lacZ expression values were determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to ACT1 levels. Fold up-regulation of lacZ was determined by dividing normalized lacZ values from cells induced to form filaments under each filament-inducing condition by normalized lacZ values from cells grown under non-filament inducing conditions. Please note that the fold lacZ up-regulation value for the—6.0 kb UME6 promoter construct in 37°C + serum has been reported previously [38].

In order to identify neutral pH responsive UME6 promoter elements, strains carrying UME6 promoter deletions were induced to form filaments in Lee’s pH 6.8 at 30°C (Lee’s pH 4.5 at 30°C was used as a non-inducing control). Cells were harvested 1 hour following induction for total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis. We observed ~14-fold lacZ induction with both the 7 kb and 6 kb UME6 promoters (Fig. 3). Interestingly, lacZ was not induced by the 5.5 kb promoter, suggesting that the -5.5 kb to -6 kb region is necessary for lacZ up-regulation in response to neutral pH. We also observed mild lacZ induction with the -4.9 kb to -7 kb and -4.9 kb to -6 kb UME6 promoter deletions. In contrast to our previous observations regarding the UME6 promoter element response to serum and temperature, the -4.0 kb to -6.0 kb and -3.0 kb to -6.0 kb deletions led to significantly increased lacZ induction in response to neutral pH compared to the other 3’ UME6 promoter deletions. These results suggest the presence of a positive neutral pH response element in the -4.0 kb to -4.9 kb promoter region (Fig. 3). Overall, our results suggest that specific regions of the UME6 promoter control responses to serum at 37°C and neutral pH.

Discussion

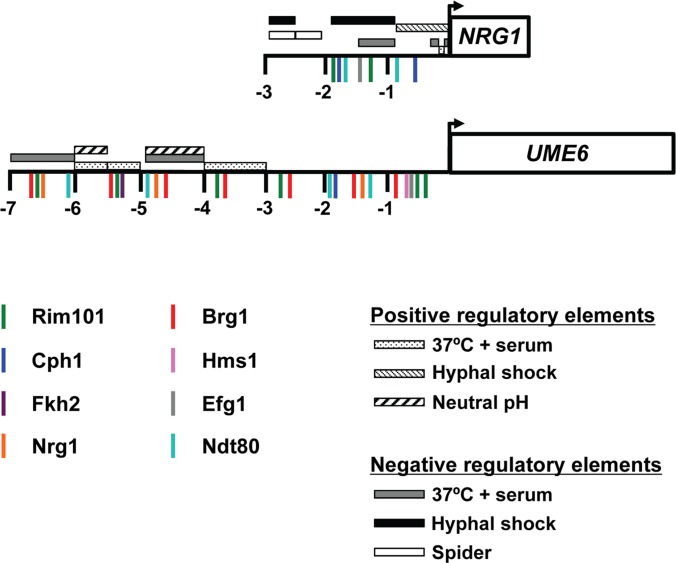

Nrg1 and Ume6 represent key transcriptional regulators of the C. albicans yeast-filament transition which function together in a feedback loop under filament-inducing conditions and are themselves transcriptionally controlled [21, 22, 30, 31]. Characterization of the NRG1 and UME6 promoter regions and identification of elements in these regions which respond to specific filament-inducing conditions (Fig. 4) therefore represents an important step in determining how various C. albicans filamentous growth signaling pathways ultimately control the yeast-filament transition and virulence at the transcriptional level. In the case of the NRG1 promoter, we have identified a key serum and temperature-responsive repressor element in the -883 bp and -1.5 kb region. This region also contains potential binding sites for Ndt80 and Efg1 (Fig. 4). Efg1, important for induction of filament-specific gene expression in response to serum and temperature, is a downstream target of the cAMP/PKA pathway [49–51]. Efg1 has also previously been shown to be specifically important for down-regulation of the NRG1 transcript under these conditions [21]. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that additional transcriptional regulators, which have not yet been identified, also function to down-regulate NRG1 via the -1.5 kb to -883 bp or -74 bp to -50 bp regions. This is especially the case for the later region since potential binding sites for known C. albicans transcription factors were not identified in this region by our in silico analysis (Fig. 4). Similarly, the in silico analysis did not identify potential binding sites for known transcription factors in the Spider responsive elements, suggesting that down-regulation of NRG1 under this condition most likely occurs via regulators which are currently uncharacterized.

Fig 4. Summary of filament condition-specific response regions in the NRG1 and UME6 promoters.

Schematic representation of the NRG1 and UME6 promoters showing specific regions important for responding to the indicated filament-inducing conditions. For each promoter, putative transcription factor binding sites identified by Transcription Element Search Software (TESS, (www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess, default parameters [41]) (Rim101, Cph1 and Fkh2) and by previous studies (Nrg1) [44] are shown. Transcription factor binding sites identified in previous studies by ChIP-Chip and DNA tiling array analysis (Brg1, Hms1, Efg1 and Ndt80) are also included [42–45]. Please note that S. cerevisiae consensus binding sequences for orthologs of Fkh2 and Cph1 were used in our analysis; Forkhead protein binding sites are well-conserved among eukaryotes[52]. Numbers indicate position (in kb) upstream from the start codon. Note: not drawn exactly to scale.

While numerous attempts were made to identify pH-responsive elements that control NRG1 expression, we were unable to detect down-regulation of the full-length NRG1 promoter-S. thermophilus lacZ reporter in α-MEM pH 7.4, as previously reported [53], or in Lee’s medium, pH 6.8 (data not shown). Although our in silico analysis identified two potential Rim101 binding sites within the NRG1 promoter (Fig. 4), previous work has suggested that NRG1 and RIM101 function in independent pathways [54]. One possible explanation is that additional elements located greater than 2.9 kb upstream of the start codon are required for NRG1 down-regulation in response to neutral pH. Alternatively, secondary structure of the native chromatin at the NRG1 locus, which our reporter does not replicate, may also play an important role in pH regulation of NRG1 transcription.

This study is the first to identify DNA elements important for the ability of C. albicans to regulate gene expression in response to hyphal shock which has previously been shown to induce filamentation [18, 47]. Our finding that farnesol fails to down-regulate the NRG1 promoter is consistent with previous studies indicating that NRG1 transcript expression and down-regulation are not affected by this quorum-sensing molecule [46, 55]. Interestingly, however, a recent study has shown that farnesol blocks degradation of the Nrg1 protein, leading to yeast growth [46]. At this point we cannot exclude the possibility that other quorum-sensing molecules may play an important role in the hyphal shock transcriptional response at the NRG1 promoter. In addition, since hyphal shock was induced by diluting late log phase cultures into fresh nutrient-rich medium, signaling pathways involved in nutrient sensing, such as Tor, might also be involved in this process.

Several of our findings regarding regulatory regions in the UME6 promoter are also consistent with the location of known filamentous growth transcriptional regulator binding sites. More specifically, we have identified the -4.0 kb to -4.9 kb region as containing a key serum and temperature responsive negative element and this region has multiple predicted Nrg1 binding sites at ~ -4800 bp that might contribute towards the observed transcriptional repression [44]. This observation is consistent with our previous finding that UME6 is under negative control by Nrg1 [30]. In addition, the -5 kb to -5.5 kb UME6 promoter region required for induction contains a Brg1 binding site at ~ -5.3 kb [44]. Brg1 has previously been shown to be required for UME6 expression during growth in YEPD at 37°C with rapamycin [44]. While there are several predicted Rim101 binding sites throughout the UME6 promoter, none of these sites are located in the -5.5 kb to -6 kb or -4.0 to -4.9 kb neutral pH response regions. It is possible that other pH-responsive transcription factors, which have not yet been identified, may be controlling UME6 expression through these elements.

One limitation of our study is that growth in YEPD at 30°C, a non-physiological temperature, was used as a non-filament-inducing condition. We chose to use YEPD at 30°C as the non-inducing condition because growth in YEPD at 37°C causes mild filamentation as well as transcriptional effects, such as induction of UME6, that could significantly blunt the sensitivity of our assay [18, 30]. However, a limitation of this approach is that we cannot exclude the possibility that our observed results are due to a temperature shift rather than specific changes in UME6 or NRG1 expression.

It is important to bear in mind that C. albicans filamentation and the expression of Nrg1 and Ume6 are controlled at multiple levels. As previously mentioned, Nrg1 is regulated at the level of protein stability in response to farnesol [46]. An anti-sense mRNA stability mechanism is also known to control NRG1 [56]. In addition, we have recently shown that UME6 expression is inhibited by a 5’ UTR-mediated translational efficiency mechanism [38] and another recent report indicates that Ume6 protein levels are synergistically stabilized by hypoxia and high CO2 [32]. In this study, we provide new information specifically regarding the transcriptional control of these important C. albicans filamentous growth regulators. Our identification of distinct filament condition-specific response elements in both the NRG1 and UME6 promoters suggests that a complex array of multiple filamentous growth signaling pathways either directly or indirectly target these key regulators. While several signaling pathways have been previously characterized, additional pathways remain unknown and it is hoped that future studies will shed more light in this area.

Conclusions

Nrg1 and Ume6 are key transcriptional regulators of filament-specific gene expression and virulence in C. albicans. However, mechanisms controlling the expression of these regulators in response to filament-inducing conditions are poorly understood. In this study, we have identified several condition-specific response elements within the NRG1 and UME6 promoters for some of the most commonly investigated filament-inducing conditions, including growth in serum at 37°C, Spider medium (nitrogen and carbon starvation) and neutral pH (summarized in Fig. 4). Several of these elements contain predicted binding sites for known transcriptional regulators of filamentation which have been shown to be important for controlling NRG1 and/or UME6 expression. Other response elements appear to be targeted by signaling pathways and/or transcriptional regulators which have not yet been fully characterized. Overall, because C. albicans encounters a variety of microenvironments during infection that can promote or inhibit filamentation, our results suggest that UME6 and NRG1 transcripts can be differentially modulated by multiple signaling pathways which respond to host environmental cues. This modulation, in turn, could potentially affect virulence and morphology determination in a niche-specific manner in vivo.

Supporting Information

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Wickes and other members of the San Antonio Center for Medical Mycology for fruitful discussions and advice during the course of the experiments. We are grateful to Alistair Brown (University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom) for plasmids and strains.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

D.S.C. was supported by a COSTAR fellowship (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant T32DE014318) in addition to a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Predoctoral Fellows (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant F31DE021930). D.K. was supported by Grant 5RO1AI083344 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases as well as a Voelcker Young Investigator Award from the Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research or the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Odds FC. Candida and Candidosis. 2nd ed London: Baillière Tindall; 1988. 468 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Filler SG, Kullberg BJ. Deep-seated candidal infections In: Calderone R, editor. Candida and candidiasis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2002. p. 341–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cannon RD, Chaffin WL. Oral colonization by Candida albicans . Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10(3):359–83. Epub 2000/04/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Wen K, Lamster IB. Candida albicans triggers interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 responses by oral fibroblasts in vitro. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1999;14(6):364–70. Epub 2000/07/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans . Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sobel JD. Pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14 Suppl 1:S148–53. Epub 1992/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calderone RA, Clancy CJ, editors. Candida and Candidiasis. 2nd ed Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edmond MB, Wallace SE, McClish DK, Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in United States hospitals: a three-year analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(2):239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):309–17. Epub 2004/08/13. doi: 10.1086/421946 CID32752 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown AJ. Expression of growth form-specific factors during morphogenesis in Candida albicans In: Calderone RA, editor. Candida and Candidiasis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2002. p. 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumamoto CA, Vinces MD. Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cellular microbiology. 2005;7(11):1546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korting HC, Hube B, Oberbauer S, Januschke E, Hamm G, Albrecht A, et al. Reduced expression of the hyphal-independent Candida albicans proteinase genes SAP1 and SAP3 in the efg1 mutant is associated with attenuated virulence during infection of oral epithelium. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52(Pt 8):623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink GR. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90(5):939–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gow NA, Brown AJ, Odds FC. Fungal morphogenesis and host invasion. Current opinion in microbiology. 2002;5(4):366–71. Epub 2002/08/06. doi: S1369527402003387 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2(5):1053–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalle F, Wachtler B, L'Ollivier C, Holland G, Bannert N, Wilson D, et al. Cellular interactions of Candida albicans with human oral epithelial cells and enterocytes. Cellular microbiology. 2010;12(2):248–71. Epub 2009/10/30. doi: CMI1394 [pii] 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorenz MC, Bender JA, Fink GR. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3(5):1076–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kadosh D, Johnson AD. Induction of the Candida albicans filamentous growth program by relief of transcriptional repression: a genome-wide analysis. Molecular biology of the cell. 2005;16(6):2903–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nantel A, Dignard D, Bachewich C, Harcus D, Marcil A, Bouin AP, et al. Transcription profiling of Candida albicans cells undergoing the yeast-to-hyphal transition. Molecular biology of the cell. 2002;13(10):3452–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun BR, Johnson AD. Control of filament formation in Candida albicans by the transcriptional repressor TUP1 Science. 1997;277(5322):105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braun BR, Kadosh D, Johnson AD. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C. albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 2001;20:4753–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murad AMA, Leng P, Straffon M, Wishart J, Macaskill S, MacCallum D, et al. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans . EMBO J. 2001;(20):4742–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zheng X, Wang Y, Wang Y. Hgc1, a novel hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein regulates Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis. EMBO J. 2004;23(8):1845–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carlisle PL, Banerjee M, Lazzell A, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. Expression levels of a filament-specific transcriptional regulator are sufficient to determine Candida albicans morphology and virulence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:599–604. 10.1073/pnas.0804061106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mitchell AP. Dimorphism and virulence in Candida albicans . Current opinion in microbiology. 1998;1(6):687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown AJ. Morphogenetic signaling pathways in Candida albicans In: Calderone RA, editor. Candida and Candidiasis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2002. p. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown AJ, Gow NA. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7(8):333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biswas S, Van Dijck P, Datta A. Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(2):348–76. Epub 2007/06/08. doi: 71/2/348 [pii] 10.1128/MMBR.00009-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lu Y, Su C, Wang A, Liu H. Hyphal development in Candida albicans requires two temporally linked changes in promoter chromatin for initiation and maintenance. PLoS biology. 2011;9(7):e1001105 Epub 2011/08/04. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001105 PBIOLOGY-D-10-01188 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Banerjee M, Thompson DS, Lazzell A, Carlisle PL, Pierce C, Monteagudo C, et al. UME6, a novel filament-specific regulator of Candida albicans hyphal extension and virulence Molecular biology of the cell. 2008;19(4):1354–65. 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeidler U, Lettner T, Lassnig C, Muller M, Lajko R, Hintner H, et al. UME6 is a crucial downstream target of other transcriptional regulators of true hyphal development in Candida albicans . FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9(1):126–42. Epub 2008/12/05. doi: FYR459 [pii] 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu Y, Su C, Solis NV, Filler SG, Liu H. Synergistic Regulation of Hyphal Elongation by Hypoxia, CO2, and Nutrient Conditions Controls the Virulence of Candida albicans . Cell host & microbe. 2013;14(5):499–509. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guthrie C, Fink GR. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. xxxvii, 933 p. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu H, Kohler J, Fink GR. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science. 1994;266(5191):1723–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee KL, Buckley HR, Campbell CC. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans . Sabouraudia. 1975;13(2):148–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia-Sanchez S, Mavor AL, Russell CL, Argimon S, Dennison P, Enjalbert B, et al. Global roles of Ssn6 in Tup1- and Nrg1-dependent gene regulation in the fungal pathogen, Candida albicans . Molecular biology of the cell. 2005;16(6):2913–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Short JM, Fernandez JM, Sorge JA, Huse WD. Lambda ZAP: a bacteriophage lambda expression vector with in vivo excision properties. Nucleic acids research. 1988;16(15):7583–600. Epub 1988/08/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Childers DS, Mundodi V, Banerjee M, Kadosh D. A 5' UTR-mediated translational efficiency mechanism inhibits the Candida albicans morphological transition. Molecular microbiology. 2014;92(3):570–85. 10.1111/mmi.12576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic acids research. 2001;29(9):e45 Epub 2001/05/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lackey E, Vipulanandan G, Childers DS, Kadosh D. Comparative evolution of morphological regulatory functions in Candida species. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12(10):1356–68. 10.1128/EC.00164-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schug J. Unit 2.6: Using TESS to Predict Transcription Factor Binding Sites in DNA Sequence Current Protocols in Bioinformatics: John Wiley and Sons; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sellam A, Askew C, Epp E, Tebbji F, Mullick A, Whiteway M, et al. Role of transcription factor CaNdt80p in cell separation, hyphal growth, and virulence in Candida albicans . Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9(4):634–44. 10.1128/EC.00325-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lassak T, Schneider E, Bussmann M, Kurtz D, Manak JR, Srikantha T, et al. Target specificity of the Candida albicans Efg1 regulator. Molecular microbiology. 2011;82(3):602–18. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lu Y, Su C, Liu H. A GATA transcription factor recruits Hda1 in response to reduced Tor1 signaling to establish a hyphal chromatin state in Candida albicans . PLoS pathogens. 2012;8(4):e1002663 Epub 2012/04/27. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002663 PPATHOGENS-D-11-02628 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shapiro RS, Sellam A, Tebbji F, Whiteway M, Nantel A, Cowen LE. Pho85, Pcl1, and Hms1 signaling governs Candida albicans morphogenesis induced by high temperature or Hsp90 compromise. Curr Biol. 2012;22(6):461–70. Epub 2012/03/01. doi: S0960-9822(12)00123-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu Y, Su C, Unoje O, Liu H. Quorum sensing controls hyphal initiation in Candida albicans through Ubr1-mediated protein degradation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(5):1975–80. 10.1073/pnas.1318690111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Enjalbert B, Whiteway M. Release from quorum-sensing molecules triggers hyphal formation during Candida albicans resumption of growth. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4(7):1203–10. 10.1128/EC.4.7.1203-1210.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lindsay AK, Deveau A, Piispanen AE, Hogan DA. Farnesol and cyclic AMP signaling effects on the hypha-to-yeast transition in Candida albicans . Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11(10):1219–25. 10.1128/EC.00144-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bockmuhl DP, Ernst JF. A potential phosphorylation site for an A-type kinase in the Efg1 regulator protein contributes to hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans . Genetics. 2001;157(4):1523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Braun BR, Johnson AD. TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans . Genetics. 2000;155(1):57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tebarth B, Doedt T, Krishnamurthy S, Weide M, Monterola F, Dominguez A, et al. Adaptation of the Efg1p morphogenetic pathway in Candida albicans by negative autoregulation and PKA-dependent repression of the EFG1 gene. Journal of molecular biology. 2003;329(5):949–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaufmann E, Muller D, Knochel W. DNA recognition site analysis of Xenopus winged helix proteins. Journal of molecular biology. 1995;248(2):239–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lotz H, Sohn K, Brunner H, Muhlschlegel FA, Rupp S. RBR1, a novel pH-regulated cell wall gene of Candida albicans, is repressed by RIM101 and activated by NRG1 . Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3(3):776–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bensen ES, Martin SJ, Li M, Berman J, Davis DA. Transcriptional profiling in Candida albicans reveals new adaptive responses to extracellular pH and functions for Rim101p. Molecular microbiology. 2004;54(5):1335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kebaara BW, Langford ML, Navarathna DH, Dumitru R, Nickerson KW, Atkin AL. Candida albicans Tup1 is involved in farnesol-mediated inhibition of filamentous-growth induction. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7(6):980–7. 10.1128/EC.00357-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cleary IA, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Thomas DP, Saville SP. BRG1 and NRG1 form a novel feedback circuit regulating Candida albicans hypha formation and virulence. Molecular microbiology. 2012;85(3):557–73. Epub 2012/07/05. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08127.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.