Background: Parathyroid hormone (PTH) stimulates MMP13 in osteoblasts.

Results: Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activation suppresses PTH stimulation of Mmp13 expression, and this process is mediated by the AP-1 complex.

Conclusion: SIRT1 is a novel suppressor of PTH stimulation of MMP13 expression.

Significance: Activation of SIRT1 and suppression of MMP13 may prolong the anabolic bone-forming period of PTH treatment in osteoporotic patients.

Keywords: AP1 Transcription Factor (AP-1), Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP), Osteoblast, Parathyroid Hormone, Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), PTH

Abstract

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is the only current anabolic treatment for osteoporosis in the United States. PTH stimulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) in bone. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), an NAD-dependent deacetylase, participates in a variety of human diseases. Here we identify a role for SIRT1 in the action of PTH in osteoblasts. We observed increased Mmp13 mRNA expression and protein levels in bone from Sirt1 knock-out mice compared with wild type mice. PTH-induced Mmp13 expression was significantly blocked by the SIRT1 activator, resveratrol, in osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells. In contrast, the SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527, significantly enhanced PTH-induced Mmp13 expression. Two h of PTH treatment augmented SIRT1 association with c-Jun, a component of the transcription factor complex, activator protein 1 (AP-1), and promoted SIRT1 association with the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter. This binding was further increased by resveratrol, implicating SIRT1 as a feedback inhibitor regulating Mmp13 transcription. The AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter is required for PTH stimulation of Mmp13 transcriptional activity. When the AP-1 site was mutated, EX527 was unable to increase PTH-stimulated Mmp13 promoter activity, indicating a role for the AP-1 site in SIRT1 inhibition. We further showed that SIRT1 deacetylates c-Jun and that the cAMP pathway participates in this deacetylation process. These data indicate that SIRT1 is a negative regulator of MMP13 expression, SIRT1 activation inhibits PTH stimulation of Mmp13 expression, and this regulation is mediated by SIRT1 association with c-Jun at the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter.

Introduction

Parathyroid hormone (PTH)2 is a polypeptide hormone that is produced by the parathyroid gland. It is an essential regulator of calcium homeostasis and a major regulator of bone remodeling (1) in both normal and pathological conditions. Daily intermittent injections of PTH promote bone formation in osteoporotic patients (2). On the other hand, excessive PTH, as seen in patients with hyperparathyroidism, causes bone loss (3).

PTH stimulates bone formation by binding to its receptors on osteoblasts (4). Additionally, PTH increases transcription and secretion of the collagenase, MMP13, in osteoblasts (5, 6).

MMP13 is a key enzyme that degrades type I collagen in bone matrix. It is critical for endochondral ossification and bone formation because Mmp13 knock-out mice have delayed endochondral bone formation, vascularization of their primary ossification centers, and ossification (7). However, excess MMP13 is associated with pathological conditions. MMP13 is highly expressed in osteoarthritis (8), rheumatoid arthritis (9), and tumor metastasis (10).

PTH stimulates MMP13 expression in bone tissue in vivo (5) as well as in osteoblastic cells in vitro (6, 11). Upon PTH treatment of UMR 106-01 cells, an initial increase of Mmp13 mRNA was observed at 2 h, and maximal induction was seen at 4 h, which declined to ∼30% of maximum by 8 h (6).

We and others found that the AP-1 transcription complex is essential to the process of PTH stimulation of Mmp13 gene expression. In response to PTH, Mmp13 gene transcription was significantly attenuated by mutation of AP-1 binding sites (12). We have previously shown that PTH stimulation of MMP13 expression is regulated by histone acetylases p300, p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF), and histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) (13–15).

HDACs are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups from an ϵ-N-acetyl lysine amino acid on a histone, thus regulating gene expression. SIRT1 is one of the class III HDACs, being an NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase. Mammals have seven sirtuins (SIRT1–7) (16). Of the seven sirtuins, SIRT1 has been the most investigated. SIRT1 targets not only histones but also a variety of other proteins.

Sirtuins have been identified as a family of antiaging genes and have been shown to increase lifespan in lower organisms. SIRT1 activity declines with age (17), suggesting the association of SIRT1 with age-related diseases. One of the age-related diseases is bone loss. Therefore, it is likely that SIRT1 functions in bone.

Indeed, SIRT1 is expressed in osteoblasts (18), and global Sirt1−/− mice have delayed bone mineralization (19). Osteoblast-specific (18) or mesenchymal-stem cell-specific (20) Sirt1 deletion results in loss of bone mass. On the other hand, SIRT1 overexpression protects against age-induced bone loss in mice (21), and SIRT1 activation prevents bone loss (22–24). These observations are the compelling systematic biological rationale for our focus on SIRT1 in bone.

In the present study, we determined the function of SIRT1 in the action of PTH stimulation of MMP13 transcription in osteoblasts. We propose that SIRT1 negatively regulates this process. Indeed, we found that SIRT1 activation blocked, whereas SIRT1 inhibition or deletion enhanced, PTH stimulation of Mmp13 mRNA. This regulation is in part mediated by SIRT1 association with Jun at the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of New York University and Ottawa Health Research Center Institute. One-month-old wild type C57BL/6 mice were utilized to isolate primary osteoblasts from cortical bone chips, and nine mice were utilized in these experiments.

Sirt1-deficient mice on C57BL/6 genetic background were kindly provided by Dr. Michael W. McBurney at Ottawa Health Research Center Institute. RNA extractions were from frozen femurs of 2.5–7-month-old Sirt1+/+ and Sirt1−/− male and female mice (25). Four Sirt1+/+ and 10 Sirt1−/− mice were utilized for RNA analysis. Two mice per group were utilized for histology and protein extraction, respectively. Histology sections and protein extractions were from femora and tibiae of 3-month-old female Sirt1+/+ and Sirt1−/− mice.

Primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were isolated from 1-month-old Sirt1 osteoblast-specific knock-out (Sirt1Ob−/−) and control Sirt1flox/flox (Sirt1fl/fl) male mice. Sirt1Ob−/− and Sirt1fl/fl mice for experiments are offspring from a breeding unit of Sirt1fl/fl (female) and Col1a12.3kb-CreTg/−;Sirt1fl/fl (male) transgenic mice. Col1a12.3kb-CreTg/−;Sirt1fl/fl were offspring from a breeding pair of Col1a12.3kb-CreTg/−;Sirt1fl/+ (male) and Sirt1fl/fl (female); Col1a12.3kb-CreTg/−;Sirt1fl/+ were from a breeding pair of Col1a12.3kb-CreTg/Tg (male) and Sirt1fl/fl (female). The Col1a12.3kb-Cre mice were kindly provided by Dr. Jennifer Westendorf (Mayo Clinic), and the 2.3-kb Col1a1 promoter is selectively expressed in committed osteoblasts (26). The Sirt1fl/fl mice were kindly provided by Dr. David Sinclair (Harvard University) (27). All mice were on a C57BL/6 genetic background.

Genotyping was performed using tail DNA with three primers: flox, 5′-GGT TGA CTT AGG TCT TGT CTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGT CCC TTG TAA TGT TTC CC-3′ (reverse); Sirt1, 5′-GCCCATTAAAGCAGTATGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATGTAATCTCAACCTTGAG-3′ (reverse); and Cre, 5′-AAC CTG AAG ATG TTC GCG AT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACC GTC AGT ACG TGA GAT ATC-3′ (reverse).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the metaphyseal region of the femurs or from cultured cells utilizing TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA (0.3 μg) was reverse transcribed with TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents (Life Technologies, Inc.). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using the SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix in a Mastercycler® ep realplex instrument (Eppendorf). Relative mRNA expression was calculated using a formula reported previously (28). The levels of mRNAs were normalized to β-actin and then expressed as relative mRNA values. The mouse-specific primers were as follows: β-actin, 5′-TCC TCC TGA GCG CAA GTA CTC T-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGG ACT CAT CGT ACT CCT GCT T-3′ (reverse); Mmp13, 5′-GCC CTG ATG TTT CCC ATC TA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTT TGG GAT GCT TAG GGT TG-3′ (reverse); osteocalcin, 5′-TAGTGAACAGACTCCGGCGCTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTAGGCGGTCTTCAAGCCAT-3′ (reverse); bone sialoprotein, 5′-ACACCCCAAGCACAGACTTTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCTCGTCGCTTTCCTTCACT-3′ (reverse).

Cell Culture

The rat osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 25 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Primary osteoblasts were isolated from bone chips of femora/tibiae of 1-month-old male wild type mice and were cultured in α-MEM plus 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in 100-mm dishes. At confluence, the cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well of 6-well plates. After reaching 90% confluence, cells were changed to medium with 0% FBS and treated with 10 μm EX527 or vehicle overnight. The next day, cells were treated with 10−8 m PTH or vehicle for 2 h before total protein was extracted or 4 h before RNA extraction. Resveratrol was added to the cells alone or together with PTH post-serum starvation. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum.

BMSCs isolated from 1-month-old male Sirt1Ob−/− and control Sirt1flox/flox (Sirt1fl/fl) mice were plated in 6-well plates at 107 cells/well. BMSCs were grown in proliferation medium (α-MEM plus 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) for 12 days and then switched to osteoblast differentiation medium (α-MEM plus 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10−8 m dexamethasone, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 8 mm β-glycerophosphate) for 10 days. Cells were changed to medium with 0% FBS overnight before EX527 (1 μm) and PTH (10−8 m) treatment. After 4 h of treatment, RNAs were extracted and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR.

Luciferase Assay

For luciferase assays, UMR 106-01 cells were plated in 12-well plates overnight before transfecting with either wild type Mmp13 promoter construct (100 ng/well in 12-well plates) or Mmp13 promoter construct with mutation of the AP-1 site (12). Two days after transfection, cells were serum-deprived overnight. Cells were then either pretreated with resveratrol for 2 h or with EX527 overnight before PTH (10−8 m for resveratrol experiments, 10−9 m for EX527 experiments, rat PTH(1–34); Sigma) treatment for 6 h. Our previous studies have shown that 10−8 m PTH elicits the maximal stimulation of Mmp13 gene expression (6). Because we expected an enhancement of Mmp13 gene expression after co-treatment with PTH and SIRT1 inhibitor, we decided to use 10−9 m PTH in the EX527 experiment. The cell lysates were harvested and analyzed immediately for luciferase activity with the luciferase assay reagent (Promega) and an OptiCompII luminometer (MGM Instruments, Inc., Hamden, CT). Luciferase activity was normalized to the amount of protein, which was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

UMR 106-01 cells were treated with medium (control) or PTH (10−8 m) and/or resveratrol (4.5 μm) for 4 h. The cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature with medium containing 0.8% formaldehyde solution. The cells were then washed with ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitors and 1 mm formaldehyde and resuspended in SDS lysis buffer for 10 min on ice. The samples were then sonicated to reduce the DNA length to 0.5–1 kbp. The cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was diluted 10-fold in buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mm EDTA, 16.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 167 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitors). For PCR analysis, aliquots (1:100) of total chromatin were saved before immunoprecipitation. Prior to chromatin precipitation, the samples were precleared with 80 μl of a 25% (v/v) suspension of DNA-coated protein A/G-agarose for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation with the appropriate antibody (anti-SIRT1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-c-Jun (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-c-Fos (Santa Cruz Biotechnology)) or with IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a negative control for ChIP analysis overnight at 4 °C. For ChIP-reChIP assays, the immunoprecipitated complexes obtained by ChIP with anti-c-Jun antibody (Cell Signaling) were eluted in ChIP elution buffer and then diluted 5-fold and subjected to the ChIP procedure with anti-SIRT1 (Abcam) or IgG as negative control. Then the DNA was subjected to PCR with primers −84/−2 that amplified the AP-1 site of the rat Mmp13 promoter, 5′-ACTCACTAGGAAGTGAACAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCCAGGGCAAGCATTCTCTA-3′ (reverse) (13). Input DNA (1:100) is a positive control for the assay. Data are shown as -fold change compared with the IgG control samples.

Protein Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analyses

For protein immunoprecipitation, UMR 106-01 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes. After reaching 90% confluence, cells were serum-deprived overnight. The cells were then treated with 10−8 m PTH for 4 h. At the end of the culture, whole cell lysates were harvested with RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors) and were incubated in RIPA buffer for 15 min at 4 °C before centrifuging for 15 min at 14,000 rpm. Protein concentrations were measured in the supernatants by the Bio-Rad protein assay. The lysates were precleared with IgG for 30 min at 4 °C, and then equal amounts of protein lysates were incubated with anti-c-Jun antibody (0.5 μg of antibody/1 mg of total protein; BD Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C. The lysates were then incubated with protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h before centrifugation at 2,500 rpm at 4 °C to pull down the immunoprecipitation complexes. The beads were washed with RIPA buffer three times and were then boiled in SDS loading buffer for 5 min. Samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dried milk and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-SIRT1 (1:2,000; Abcam) or anti-c-Jun (1:2,000; BD Biosciences). Membranes were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 45 min at room temperature. Blots were developed with Super Signal reagents (Thermo Scientific).

For c-Jun acetylation experiments, HEK293 cells were plated overnight and then transfected with c-Jun with Sirt1 or vector FLAG plasmids. p300 plasmids were co-transfected to increase c-Jun acetylation (29). To detect c-Jun acetylation in UMR osteoblastic cells, cells were transfected with c-Jun together with p300 on the second day of cell plating. Two hundred ng of each plasmid was transfected in 10-mm culture dishes. All transfections were facilitated with GeneJammer Transfection Reagent (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Sirt1 and vector FLAG plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Paolo Sassone-Corsi (University of California). p300 plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Deyu Fang (Northwestern University) and c-Jun was from Dr. Michael J. Birrer (Massachusetts General Hospital). Seventy-two h post-transfection, cells were changed to serum-free medium, which additionally contained the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (Sigma) at 400 nm and the SIRT1 inhibitor nicotinamide (Sigma) at 20 mm. The next day, cells were treated with 8-bromo-cAMP (0.2 mm; Sigma) for 2 h for HEK cells or 10−8 m PTH or vehicle for 2 h for UMR cells, and whole cell lysates were harvested with RIPA buffer. RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors) was freshly made and had 1 mm DTT (Sigma), 400 nm trichostatin A, and 10 mm nicotinamide. Supernatants were precleared with IgG at 4 °C for 15 min and then incubated with anti-c-Jun antibody (0.5 μg of antibody/1 mg of total protein; BD Biosciences) for 1 h, followed by incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads for an additional 2 h. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, dissolved with 4× Laemmli's buffer, and boiled for 5 min. After SDS-PAGE fractionation and transfer to PVDF membranes, they were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dried milk and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with acetylated lysine antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling). Blots were developed with SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). Membranes were then blotted with anti-c-Jun (1:2000; BD Biosciences). To detect MMP13 protein in bone, Western blots were performed with protein extracted from the whole bones of femur and tibia (including marrow) from 3-month-old female mice (n = 2). Membranes were first blotted with the MMP13 antibody (Abcam), and then blots were reprobed with β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling). Western blot bands were analyzed by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

For histological analysis, femora and tibiae were harvested from 3-month-old female Sirt1+/+ and Sirt1−/− mice. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and decalcified in 10% EDTA, pH 7.5, for 4 weeks at 4 °C. Samples were soaked in 10% sucrose for 2 h, 20% sucrose for 6 h, and then 30% sucrose overnight; embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound; and frozen. The sections (10 μm) were cut longitudinally to the femur and tibia. To evaluate the localization and protein levels of MMP13, we performed immunohistochemical staining by the ABC staining system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The sections were washed with PBS and then immersed in methanol containing 1% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were then blocked with 2% blocking serum and then with anti-MMP13 rabbit antibody (Abcam) at 4 °C overnight. Sections were then washed three times and incubated with biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG at room temperature for 30 min. Control reactions were performed by omitting primary antibody. Sections were mounted with Cytoseal 60 (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as the means ± S.E. Differences were analyzed using a Mann and Whitney U test for analysis between two groups or one-way analysis of variance using the Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) test for three or more groups, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

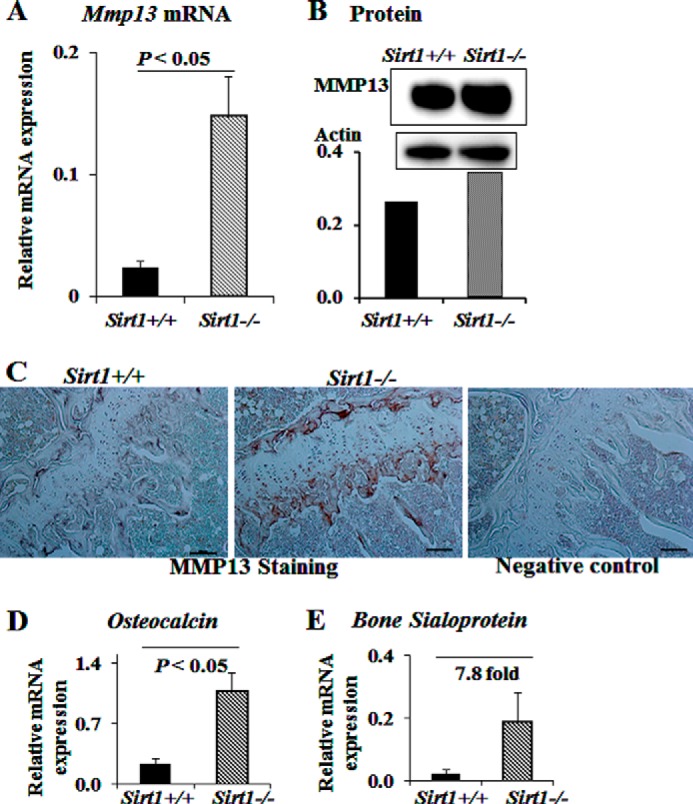

Increased Mmp13 mRNA and Protein Level in Sirt1 Knock-out Mice

To test our hypothesis that SIRT1 is a negative regulator of MMP13, we first examined the mRNA expression of Mmp13 in bones of wild type and Sirt1−/− mice. Total RNA was extracted from the metaphyseal region of the femurs of Sirt1+/+ or Sirt1−/− mice. We observed that Mmp13 mRNA expression was significantly increased in Sirt1−/− mice (Fig. 1A), indicating that SIRT1 is a negative regulator of MMP13 expression in bone. We did not observe a significant difference in Mmp13 mRNA expression by gender, or from age 2.5 to 7 months. We next determined MMP13 protein levels in whole bones from 3-month-old female mice. We found MMP13 protein increased in bones from Sirt1−/− mice compared with wild type mice (Fig. 1B). To determine the localization of MMP13, we performed immunohistochemistry. MMP13 was detected mainly in the growth plate region (Fig. 1C). We observed increased MMP13 staining in both the tibia and femoral growth plate region in Sirt1−/− mice compared with wild type mice.

FIGURE 1.

Sirt1 knock-out mice have increased Mmp13 mRNA and protein in bone. A, total RNA was extracted from the distal metaphyseal region of the femurs of 2.5–7-month-old Sirt1+/+ or Sirt1−/− mice. RNAs were measured using real-time RT-PCR. The levels of mRNAs were normalized to β-actin and then expressed as relative mRNA value. For Sirt1+/+, n = 4; for Sirt1−/−, n = 10. Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars). B, Western blots were performed with protein extracted from the whole bones of femur and tibia of 3-month-old female mice (n = 2). The numbers at the sides of Western blots represent molecular mass markers. The bands of MMP13 by Western blot are normalized to β-actin and quantified by ImageJ software. C, immunostaining of MMP13 protein at tibial growth plate of Sirt1+/+ and Sirt1−/− mice. Scale bar, 250 μm. Shown are osteocalcin (D) and bone sialoprotein (E) mRNA expression in Sirt1+/+ and Sirt1−/− mice. RNA was processed in the same way as in A.

In Sirt1−/− mice, we also observed significantly increased femoral mRNA expression of osteocalcin and a 7.8-fold increase of bone sialoprotein compared with wild type (Fig. 1, D and E). In separate studies with Sirt1 osteoblast-specific knock-out mice, we have also found that SIRT1 regulates extracellular matrix proteins, including type I collagen, and bone sialoprotein (data not shown).3

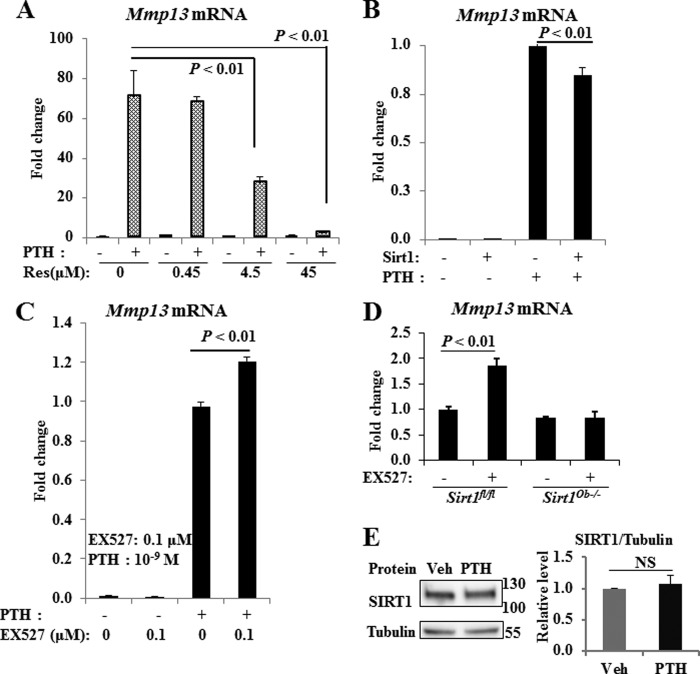

SIRT1 Activator Blocked and SIRT1 Inhibitor Enhanced Mmp13 Expression Induced by PTH

We next determined the effects of pharmacological modulation of SIRT1 on PTH stimulation of Mmp13 expression in osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells. Consistent with our previous findings, PTH highly stimulated Mmp13 mRNA expression (Fig. 2). The SIRT1 activator, resveratrol, significantly blocked Mmp13 expression stimulated by PTH in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). In support of these data, SIRT1 overexpression decreased PTH stimulation of Mmp13 mRNA (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, the SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527, enhanced Mmp13 mRNA expression induced by PTH (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Modulation of SIRT1 regulates Mmp13 expression induced by PTH. The SIRT1 activator, resveratrol (Res) (A), and SIRT1 overexpression (B) decreased Mmp13 mRNA induction by PTH, whereas the SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527 (EX), enhanced Mmp13 expression induced by PTH (C). D, SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 enhanced Mmp13 mRNA stimulated in control cells; this enhancement was abolished in Sirt1 osteoblast-specific knock-out BMSCs. Total RNA was extracted from UMR 106-01 cells or mouse BMSCs treated with control medium, PTH (10−8 or 10−9 m), and/or resveratrol or EX527 at the concentrations indicated for 4 h. RNAs were measured using real-time RT-PCR. The relative levels of Mmp13 mRNA were normalized to β-actin and then expressed as -fold stimulation over control. Error bars, S.E. of three independent experiments; n = 6–9 samples. E, protein levels of SIRT1 upon PTH stimulation. UMR cells were plated in 6-well plates, and, upon confluence, cells were treated with 10−8 m PTH or vehicle for 2 h. Whole cell lysates were harvested for Western blots for SIRT1 and tubulin. Western blots were quantified with ImageJ. Data are from six separate experiments. NS, not significant.

We further examined the effect of EX527 on BMSCs from Sirt1 osteoblast-specific knock-out (Sirt1Ob−/−) mice. EX527 enhanced Mmp13 mRNA expression in control cells, whereas we did not observe enhancement with EX527 treatment in Sirt1Ob−/− cells (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that EX527 is specific for SIRT1.

Of note, protein levels of SIRT1 did not change with PTH stimulation (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that SIRT1 is a suppressor of PTH stimulation of Mmp13 transcription.

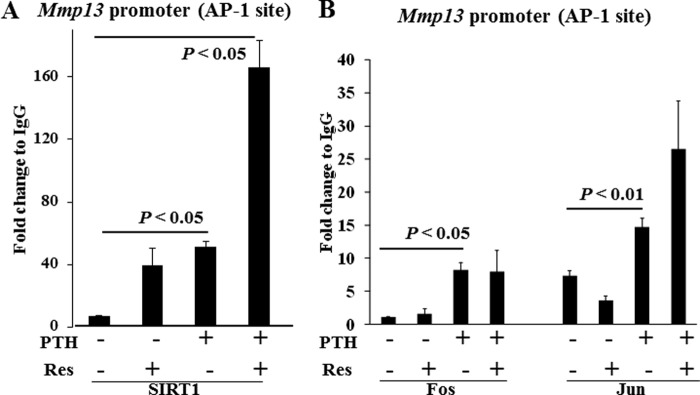

SIRT1 Associates with the AP-1 Site of the Mmp13 Promoter

To dissect the molecular mechanisms by which SIRT1 regulates Mmp13 expression, we performed ChIP assays of the rat Mmp13 promoter. We postulated that the AP-1 site is critical for SIRT1 to regulate Mmp13 expression. Notably, PTH treatment for 4 h significantly increased SIRT1 binding to the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter (Fig. 3A). This is after maximal transcription of Mmp13 has been induced at 2 h (6). The SIRT1 activator, resveratrol, further enhanced SIRT1 binding to the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter (Fig. 3A), which may be why it is a such a potent inhibitor of Mmp13 transcription. Additionally, we observed that PTH treatment enhanced the AP-1 components, c-Fos and c-Jun, binding to the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

SIRT1 associates with the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter. UMR 106-01 cells were treated with control medium or PTH (10−8 m) and/or resveratrol (4.5 μm) for 4 h. After immunoprecipitation of the cross-linked lysates with anti-SIRT1 (A), anti-c-Jun (B), or anti-c-Fos (B) or with rabbit IgG as a negative control for ChIP analysis, the DNA was subjected to PCR with primers −84/−2 that amplify the AP-1 site of the rat MMP-13 promoter. Input DNA (1:100) is a positive control for the assay. Data are shown as -fold change compared with the IgG control samples. Error bars, S.E. of two independent experiments.

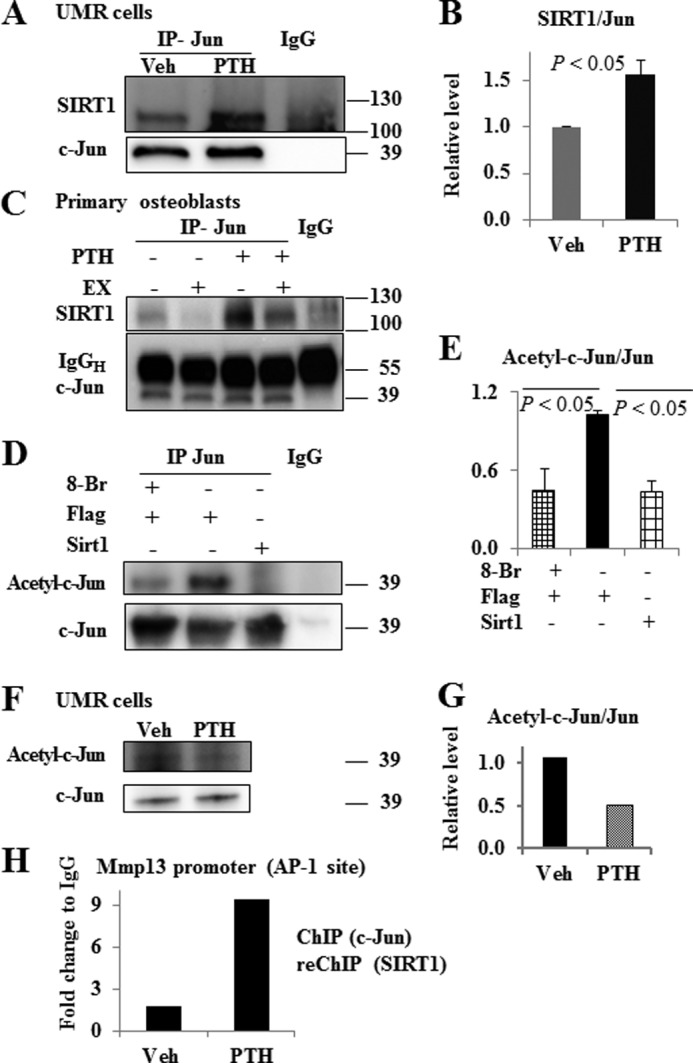

SIRT1 Associates with c-Jun in Osteoblasts and PTH Treatment Enhances the Association between These Proteins

Based on our ChIP assay data indicating that PTH promoted SIRT1 association with the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter, we then performed immunoprecipitation assays to determine the protein association of SIRT1 with c-Jun in osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells. It should be noted that SIRT1 does not associate with c-Fos (data not shown). We found that SIRT1 interacts with c-Jun in these cells and that PTH treatment significantly stimulates SIRT1 binding to c-Jun (Fig. 4, A and B). It should be noted that SIRT1 protein level does not change following PTH treatment (Fig. 2D). We confirmed the finding of PTH stimulation of SIRT1 interaction with c-Jun in primary osteoblasts, which were isolated from mouse femoral bone chips (Fig. 4C). In addition, we observed that the SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527, attenuated the interaction between SIRT1 and c-Jun (Fig. 4C) in primary osteoblasts.

FIGURE 4.

SIRT1 interacts with c-Jun on the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter in osteoblasts, and PTH treatment increases the association of SIRT1 with c-Jun. A, SIRT1 association with c-Jun in UMR 106-01 cells; B, quantification of three independent experiments. Osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells were cultured in MEM with 5% FBS to 90% confluence. After serum deprivation overnight, cells were treated with PTH (10−8 m) or vehicle for 2 h. C, SIRT1 association with c-Jun in primary osteoblasts. Quantification of SIRT1 association with c-Jun. Primary osteoblasts were isolated from bone chips of 1-month-old mice and were plated in 100-mm dishes in α-MEM plus 10% FBS. After confluence, the cells were plated in 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. Upon reaching 90% confluence, the cells were serum-deprived and treated with 10 μm EX527 or vehicle overnight. The next day, the cells were treated with PTH 10−8 m for 2 h before total protein extraction. D, SIRT1 deacetylates c-Jun, and 8-bromo-cAMP treatment reduces c-Jun acetylation. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with c-Jun and Sirt1 or vector FLAG plasmids. Seventy-two h after transfection, the cells were treated with 8-bromo-cAMP for 2 h, and whole cell lysates were harvested for analysis. E, quantification of c-Jun acetylation from three independent experiments. The value of the FLAG control group was set as 1. F, PTH treatment down-regulated c-Jun acetylation in UMR cells. UMR cells were transfected with c-Jun and p300 plasmids. After 72 h, cells were treated with 10−8 m PTH or vehicle for 2 h. One representative image of four independent experiments is shown; G, quantification of this image. The numbers at the sides of Western blots are molecular mass markers. H, PTH treatment increased SIRT1 and c-Jun association with the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter. UMR 106-01 cells were treated with control medium or PTH (10−8 m) for 2 h. The cross-linked lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Jun and then treated with anti-SIRT1 or IgG as a negative control for ChIP-reChIP analysis. The DNA was subjected to PCR with primers −84/−2, which amplify the AP-1 site of the rat Mmp13 promoter. Data are shown as -fold change compared with the IgG control samples. Error bars, S.E.

SIRT1 Deacetylates c-Jun and 8-Bromo-cAMP Stimulates Jun Deacetylation

Because we observed that SIRT1 associated with c-Jun and SIRT1 is a protein deacetylase, we next determined the acetylation of c-Jun with anti-acetyllysine antibody. We found that co-transfection of Sirt1 with c-Jun significantly reduced c-Jun acetylation (Fig. 4, D and E) in HEK293 cells. Additionally, 8-bromo-cAMP treatment decreased c-Jun acetylation (Fig. 4, D and E) as well, suggesting that the cAMP pathway is involved in this process. Further, we observed that PTH treatment down-regulated c-Jun acetylation in UMR cells (Fig. 4, F and G).

PTH Treatment Increased SIRT1 and c-Jun Association with the AP-1 Site of the Mmp13 Promoter

We further performed ChIP-reChIP analysis of SIRT1 and c-Jun, and we found that PTH treatment increased the association of SIRT1 and c-Jun to the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter (−84/−2) (Fig. 4H).

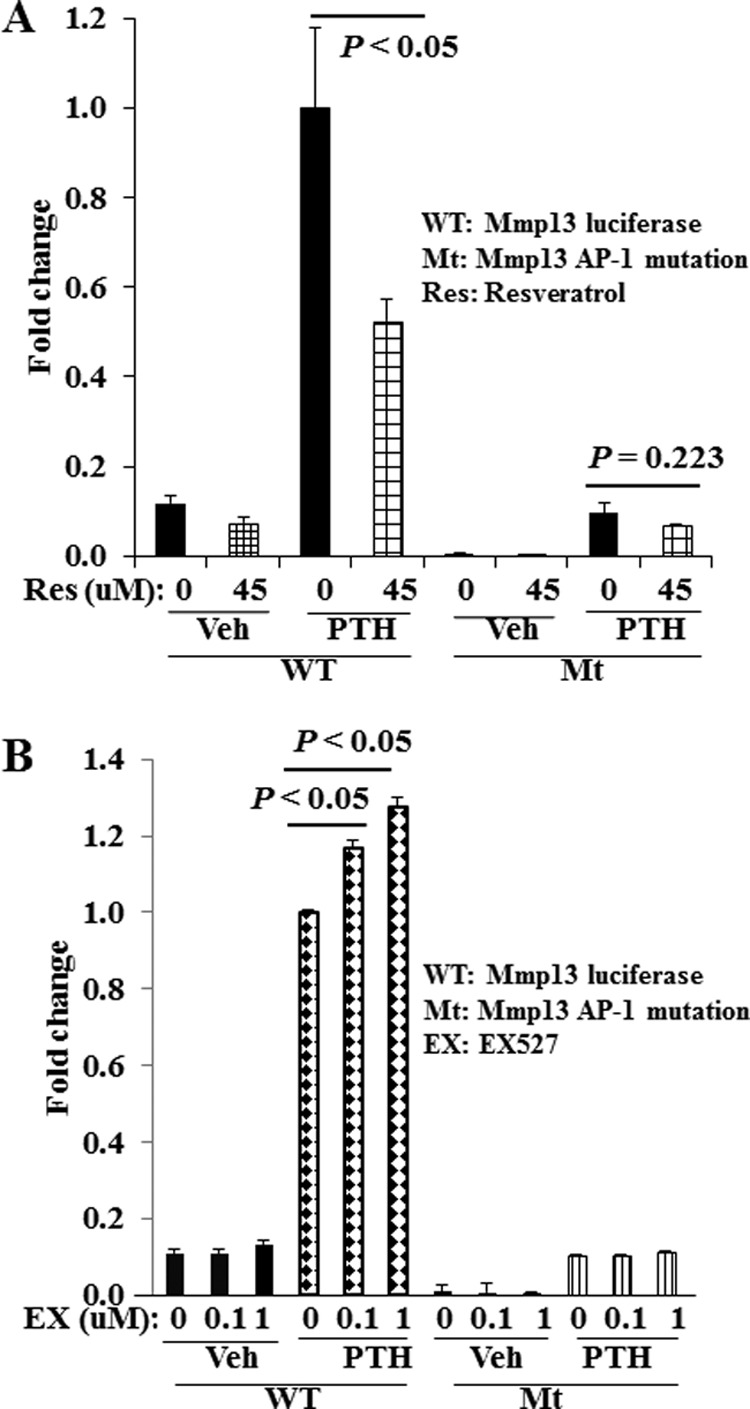

The AP-1 Site of the Mmp13 Promoter Is Essential for SIRT1 Modulation of PTH Stimulation of Mmp13 Promoter Activity

We next determined the effect of pharmacological modulation of SIRT1 on Mmp13 promoter activity stimulated by PTH. The hormone at 10−8 m maximally stimulates Mmp13 promoter activity in osteoblastic UMR 106-01 cells. Two h of pretreatment with resveratrol (45 μm) significantly blocked the PTH stimulation of Mmp13 promoter activity (Fig. 5A). To determine the importance of the AP-1 site in the role of SIRT1 action, we transfected UMR 106-01 cells with an Mmp13 promoter luciferase construct with the AP-1 site mutated. As we have reported previously (12), this Mmp13 promoter construct is not able to bind the AP-1 factors c-Jun and c-Fos. Transcriptional activity of the Mmp13 promoter with the AP-1 site mutation was reduced. PTH treatment was still able to stimulate its transcriptional activity significantly (p < 0.01); however, pretreatment with the SIRT1 activator, resveratrol (45 μm), did not inhibit Mmp13 promoter activity (Fig. 5A). Conversely, we examined the effect of the SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527, on Mmp13 transcriptional activity stimulated by PTH (10−9 m). EX527 at both 0.1 and 1 μm significantly enhanced Mmp13 transcriptional activity stimulated by PTH, but this enhancement was not observed with the AP-1 mutant promoter (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that activation of SIRT1 down-regulates and inhibition of SIRT1 enhances PTH-stimulated Mmp13 promoter activity in osteoblastic cells. These data also indicate that the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter is essential for SIRT1 modulation of Mmp13 transcriptional activity stimulated by PTH.

FIGURE 5.

The AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter is required for SIRT1 modulation of PTH-stimulated Mmp13 transcriptional activity. A, SIRT1 activation by resveratrol suppresses PTH (10−8 m) stimulation of Mmp13 promoter activity. B, SIRT1 inhibitor, EX527, enhances PTH (10−9 m) stimulation of Mmp13 promoter activity. UMR 106-01 cells were plated in 12-well plates overnight before transfecting with either wild type Mmp13 promoter construct or Mmp13 promoter construct with the AP-1 site mutated. Two days after transfection, cells were serum-deprived overnight. The cells were then pretreated with resveratrol for 2 h or with EX527 overnight before PTH (10−8 m for resveratrol experiments, 10−9 m for EX527 experiments) treatment for 6 h. The cell lysates were harvested and analyzed immediately for luciferase activity. Error bars, S.E. of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

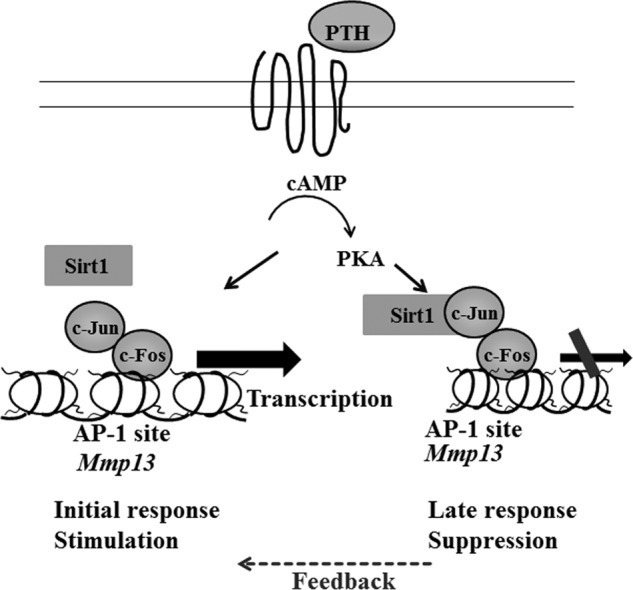

Our current study demonstrates that SIRT1 is a critical factor suppressing Mmp13 expression stimulated by PTH (Fig. 6). In the initial response, PTH stimulation recruits the AP-1 transcription factor complex to the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter and enhances transcription of Mmp13. We speculate that there is negative feedback at later stages of PTH treatment; SIRT1 is recruited to the AP-1 site, interacts with c-Jun, and suppresses Mmp13 expression. Our data present a novel mechanism, by which PTH stimulation of MMP13 expression in osteoblastic cells is modulated by SIRT1. According to this model, activation of SIRT1 and suppression of MMP13 may prolong the anabolic bone-forming period of PTH treatment in osteoporotic patients. Here, we report for the first time that SIRT1 negatively regulates MMP13 expression stimulated by PTH, and this process requires the AP-1 site in osteoblastic cells.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic model; SIRT1 is a negative regulator of MMP13, and SIRT1 activation inhibits PTH stimulation of Mmp13 gene expression in osteoblasts. The initial response to PTH stimulation in osteoblastic cells is to recruit the AP-1 transcription complex and enhance Mmp13 gene expression. Later, there is feedback by SIRT1. This enzyme is recruited to the AP-1 site of the promoter and then suppresses Mmp13 transcription stimulated by PTH.

In the present study, we have shown that activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol significantly down-regulates Mmp13 gene expression, stimulated by PTH, in osteoblastic cells. EX527, a potent SIRT1 inhibitor, is widely utilized in physiological studies. Inhibition of SIRT1 by EX527 significantly enhanced Mmp13 gene expression stimulated by PTH. Further, we observed that Sirt1 knock-out mice display a significant increase in Mmp13 gene expression and protein abundance in bone. In separate studies, we have specifically deleted Sirt1 in osteoblasts in vivo. We observed that Mmp13 mRNA expression increased in bones of osteoblast-specific knock-out mice compared with controls.3 Therefore, these data suggest that SIRT1 alone has the capacity to regulate Mmp13 expression.

Protein levels of MMP13 do not always match the mRNA expression. We have established that MMP13 is a highly regulated secreted extracellular protein. We have previously shown that osteoblastic cells respond to PTH treatment. We observed an initial increase of Mmp13 mRNA at 2 h, a maximal induction at 4 h, and ∼30% reduction of the maximum by 8 h (6).

At the protein level, we showed that UMR cells respond to PTH by secreting MMP13. This reaches a maximal concentration extracellularly 12–24 h after PTH stimulation but then declines to undetectable levels by 96 h (30). Neither spontaneous nor cell-mediated extracellular degradation could account for this disappearance because the enzyme maintained stability in both fresh and conditioned media (30).

We have identified that a specific receptor in osteoblastic cells functions to eliminate extracellular MMP13 (30). Binding of MMP13 to this receptor and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 is coupled to the internalization and eventual degradation of the enzyme.

We also showed decreased binding, internalization, and degradation of MMP13 after 24 h of PTH treatment; these activities returned to control values after 48 h and were increased substantially after 96 h of treatment of PTH. We further demonstrated that degradation of MMP13 required receptor-mediated endocytosis and sequential processing by endosomes and lysosomes (31). The subsequent internalization and degradation of MMP13 requires the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein, LRP1 (32).

Therefore, PTH regulates the expression and synthesis of Mmp13 mRNA and MMP13 protein as well as the abundance and functioning of the MMP13 receptor and the intracellular degradation of its ligand. The coordinate changes in the secretion of MMP13 and expression of the receptor determine the net abundance of the enzyme in the extracellular space (30, 31). Thus, protein levels of MMP13 do not always match mRNA expression. The data in this report indicate that SIRT1 is a repressor of Mmp13 gene expression in bone and osteoblastic cells.

In addition to MMP13, SIRT1 also targets other extracellular proteins, including osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein, in global SIRT1 knock-out and in SIRT1 osteoblast-specific knock-out mice. Our current study focuses on the function of SIRT1 in the action of PTH stimulation of Mmp13 transcription in the osteoblast.

Aging is tightly associated with osteoporosis in both women and men. Recent research into the science of aging has identified one family of antiaging genes, the sirtuins. The sirtuins are a highly conserved family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases that have been shown to increase lifespan in lower organisms. Mammals have seven sirtuins (SIRT1–7) (16). Of the seven sirtuins, SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT6, and SIRT7 are located in the nucleus (33). In addition to SIRT1, to our knowledge, SIRT6 is the only other sirtuin that has been reported to function in bone or cartilage (34, 35). We did not detect a significant difference in Sirt6 mRNA in osteoblasts of Sirt1Ob−/− and control Sirt1flox/flox mice (data not shown), suggesting that there was no compensation by SIRT6. SIRT1 is involved in a variety of human diseases (33, 36, 37), including bone diseases. SIRT1 has many functions in bone; global Sirt1 deletion (19, 38, 39) and osteoblast-specific Sirt1 deletion (18, 20, 38) lead to reduced bone formation. Potentially, SIRT1 regulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation through regulation of the transcription factor Runx2 (40, 41). Others have reported that SIRT1 associates with Runx2 and reduces its acetylation status (40). SIRT1 activation with resveratrol promotes osteoblast differentiation in vitro (40–43) and prevents bone loss in vivo (44). These observations are the compelling systematic biological rationale for our focus on SIRT1 in bone.

We understand that there are controversial reports on resveratrol activating SIRT1 (45). However, there is a growing body of studies that have shown that the effects of resveratrol depend on SIRT1. Effects of resveratrol are lost after knocking down or inhibiting SIRT1 in cell culture studies (46–48). The benefits of resveratrol require SIRT1 in vivo. The ability of resveratrol to improve glucose homeostasis is impaired when hypothalamic SIRT1 is inhibited (49). The ability of resveratrol to activate AMP-activated protein kinase and increase mitochondrial function is lost in SIRT1 knock-out mice; further, overexpression of SIRT1 mimics the effects of resveratrol on mitochondria and AMP-activated protein kinase activation (27).

Moreover, recent studies provide direct evidence of SIRT1 activation by resveratrol and other sirtuin-activating compounds (42, 50). Interaction of SIRT1 with certain substrates allows activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol and other sirtuin-activating compounds. Hubbard et al. (50) identified a critical amino acid, Glu-230, in SIRT1 required for these effects. Mouse myoblasts reconstituted with SIRT1 mutated at this amino acid lost their responsiveness to resveratrol and other SIRT1 activators (50). These studies provide strong evidence that resveratrol is a SIRT1 activator, and the effects of resveratrol depend on SIRT1 both in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, there is strong evidence that resveratrol can directly activate SIRT1 (50), although it is possible that resveratrol may indirectly activate SIRT1 through the AMP-activated protein kinase (51).

Activation of the cAMP pathway is one key means by which PTH modulates gene transcription in osteoblasts (1). We observed that 8-bromo-cAMP stimulates c-Jun deacetylation by SIRT1. In addition, PTH has been shown to increase NAD+ production in vivo (52), which is required for SIRT1 activity. SIRT1 associates with c-Jun and decreases its acetylation, thereby reducing AP-1 transcriptional activity and decreasing Mmp13 gene transcription. SIRT1 has been reported to repress MMP13 expression in chondrocytes. Sirt1 overexpression significantly inhibited the up-regulation of MMP13 caused by IL-1β (53). Conversely, reduced SIRT1 protein levels are associated with increased protein levels of MMP13 in osteoarthritic cartilage (53–56). MMP13 preferentially degrades type II collagen in cartilage but also degrades type I collagen in bone.

Previous studies in our group have reported that PTH potently induced MMP13 expression in osteoblastic cells (6). PTH regulates MMP13 gene transcription through a protein kinase A-dependent pathway (57). Under basal conditions, gene transcription of Mmp13 is repressed by the presence of HDAC4, which binds to Runx2 at the runt domain binding site (15). PTH treatment causes HDAC4 to dissociate from Runx2 on the Mmp13 promoter, and Runx2 then recruits the histone acetyltransferases, p300 and PCAF (13, 14). Newly synthesized c-Fos/c-Jun subsequently bind to the AP-1 site and interact with CBP and with proteins bound to Runx2, allowing maximal transcription of Mmp13 (58).

Our previous studies showed that c-Fos and c-Jun are the most physiologically relevant AP-1 members in regulating Mmp13 mRNA expression in osteoblasts (11). Mmp13 mRNA is initially detectable when osteoblasts cease proliferation, increasing during differentiation and mineralization. We showed that the AP-1 and runt domain binding sites are responsible for Mmp13 gene transcription. The AP-1 and runt domain binding sites bind members of the AP-1 family and Runx2 transcription factors. We have identified Runx2 binding to the runt domain binding site. We have also investigated various members of the AP-1 family: Fra-1, Fra-2, FosB, c-Fos, c-Jun, JunB, and JunD. We identified JunD in addition to a Fos-related antigen binding to the AP-1 site. Our studies showed that JunD expression remains fairly constant during osteoblast differentiation. Overexpressing Fra-2 and JunD repressed Runx2-induced Mmp13 promoter activity. Overexpression of both c-Fos and c-Jun in osteoblasts or Runx2 increased Mmp13 promoter activity. Furthermore, overexpression of c-Fos, c-Jun, and Runx2 synergistically increased Mmp13 promoter activity (11). Based on these studies, we focused on c-Fos and c-Jun in the present project.

SIRT1 has been shown to associate with c-Jun and suppress the transcriptional activity of the AP-1 factor in other cell systems: maintaining T cell tolerance (29), inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages (59), and inhibiting MMP9 expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (60). Here we report that SIRT1 suppresses MMP13 expression stimulated by PTH in osteoblastic cells, and this process is mediated through the AP-1 site of the Mmp13 promoter.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01DK047420-20 (to N. C. P.).

Y. Fei, T. Nakatani, and N. C. Partridge, manuscript in preparation.

- PTH

- parathyroid hormone

- PCAF

- p300/CBP-associated factor

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- BMSC

- bone marrow stromal cell

- MEM

- minimum essential medium

- RIPA

- radioimmune precipitation assay buffer

- AP-1

- activator protein 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Swarthout J. T., D'Alonzo R. C., Selvamurugan N., Partridge N. C. (2002) Parathyroid hormone-dependent signaling pathways regulating genes in bone cells. Gene 282, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delmas P. D. (2002) Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet 359, 2018–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan A., Bilezikian J. (2000) Primary hyperparathyroidism: pathophysiology and impact on bone. CMAJ 163, 184–187 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teitelbaum S. L. (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289, 1504–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uchida M., Yamato H., Nagai Y., Yamagiwa H., Hayami T., Tokunaga K., Endo N., Suzuki H., Obara K., Fujieda A., Murayama H., Fukumoto S. (2001) Parathyroid hormone increases the expression level of matrix metalloproteinase-13 in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 19, 207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott D. K., Brakenhoff K. D., Clohisy J. C., Quinn C. O., Partridge N. C. (1992) Parathyroid hormone induces transcription of collagenase in rat osteoblastic cells by a mechanism using cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and requiring protein synthesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 6, 2153–2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inada M., Wang Y., Byrne M. H., Rahman M. U., Miyaura C., López-Otín C., Krane S. M. (2004) Critical roles for collagenase-3 (Mmp13) in development of growth plate cartilage and in endochondral ossification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17192–17197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Billinghurst R. C., Dahlberg L., Ionescu M., Reiner A., Bourne R., Rorabeck C., Mitchell P., Hambor J., Diekmann O., Tschesche H., Chen J., Van Wart H., Poole A. R. (1997) Enhanced cleavage of type II collagen by collagenases in osteoarthritic articular cartilage. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 1534–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andereya S., Streich N., Schmidt-Rohlfing B., Mumme T., Müller-Rath R., Schneider U. (2006) Comparison of modern marker proteins in serum and synovial fluid in patients with advanced osteoarthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 26, 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Westermarck J., Kähäri V. M. (1999) Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in tumor invasion. FASEB J. 13, 781–792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Winchester S. K., Selvamurugan N., D'Alonzo R. C., Partridge N. C. (2000) Developmental regulation of collagenase-3 mRNA in normal, differentiating osteoblasts through the activator protein-1 and the runt domain binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23310–23318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Selvamurugan N., Chou W. Y., Pearman A. T., Pulumati M. R., Partridge N. C. (1998) Parathyroid hormone regulates the rat collagenase-3 promoter in osteoblastic cells through the cooperative interaction of the activator protein-1 site and the runt domain binding sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10647–10657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boumah C. E., Lee M., Selvamurugan N., Shimizu E., Partridge N. C. (2009) Runx2 recruits p300 to mediate parathyroid hormone's effects on histone acetylation and transcriptional activation of the matrix metalloproteinase-13 gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1255–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee M., Partridge N. C. (2010) Parathyroid hormone activation of matrix metalloproteinase-13 transcription requires the histone acetyltransferase activity of p300 and PCAF and p300-dependent acetylation of PCAF. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38014–38022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimizu E., Selvamurugan N., Westendorf J. J., Olson E. N., Partridge N. C. (2010) HDAC4 represses matrix metalloproteinase-13 transcription in osteoblastic cells, and parathyroid hormone controls this repression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9616–9626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guarente L. (2011) Sirtuins, aging, and medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2235–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Massudi H., Grant R., Braidy N., Guest J., Farnsworth B., Guillemin G. J. (2012) Age-associated changes in oxidative stress and NAD+ metabolism in human tissue. PLoS One 7, e42357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edwards J. R., Perrien D. S., Fleming N., Nyman J. S., Ono K., Connelly L., Moore M. M., Lwin S. T., Yull F. E., Mundy G. R., Elefteriou F. (2013) Silent information regulator (Sir)T1 inhibits NFκB signaling to maintain normal skeletal remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 960–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lemieux M. E., Yang X., Jardine K., He X., Jacobsen K. X., Staines W. A., Harper M. E., McBurney M. W. (2005) The Sirt1 deacetylase modulates the insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway in mammals. Mech. Ageing Dev. 126, 1097–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simic P., Zainabadi K., Bell E., Sykes D. B., Saez B., Lotinun S., Baron R., Scadden D., Schipani E., Guarente L. (2013) SIRT1 regulates differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by deacetylating β-catenin. EMBO Mol. Med. 5, 430–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herranz D., Muñoz-Martin M., Cañamero M., Mulero F., Martinez-Pastor B., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Serrano M. (2010) Sirt1 improves healthy ageing and protects from metabolic syndrome-associated cancer. Nat. Commun. 1, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mizutani K., Ikeda K., Kawai Y., Yamori Y. (2000) Resveratrol attenuates ovariectomy-induced hypertension and bone loss in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 46, 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Z. P., Li W. X., Yu B., Huang J., Sun J., Huo J. S., Liu C. X. (2005) Effects of trans-resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum on bone loss using the ovariectomized rat model. J. Med. Food. 8, 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pearson K. J., Baur J. A., Lewis K. N., Peshkin L., Price N. L., Labinskyy N., Swindell W. R., Kamara D., Minor R. K., Perez E., Jamieson H. A., Zhang Y., Dunn S. R., Sharma K., Pleshko N., Woollett L. A., Csiszar A., Ikeno Y., Le Couteur D., Elliott P. J., Becker K. G., Navas P., Ingram D. K., Wolf N. S., Ungvari Z., Sinclair D. A., de Cabo R. (2008) Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab. 8, 157–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McBurney M. W., Yang X., Jardine K., Hixon M., Boekelheide K., Webb J. R., Lansdorp P. M., Lemieux M. (2003) The mammalian SIR2α protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 38–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu F., Woitge H. W., Braut A., Kronenberg M. S., Lichtler A. C., Mina M., Kream B. E. (2004) Expression and activity of osteoblast-targeted Cre recombinase transgenes in murine skeletal tissues. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Price N. L., Gomes A. P., Ling A. J. Y., Duarte F. V., Martin-Montalvo A., North B. J., Agarwal B., Ye L., Ramadori G., Teodoro J. S., Hubbard B. P., Varela A. T., Davis J. G., Varamini B., Hafner A., Moaddel R., Rolo A. P., Coppari R., Palmeira C. M., de Cabo R., Baur J. A., Sinclair D. A. (2012) SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 15, 675–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pfaffl M. (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J., Lee S.-M., Shannon S., Gao B., Chen W., Chen A., Divekar R., McBurney M. W., Braley-Mullen H., Zaghouani H., Fang D. (2009) The type III histone deacetylase Sirt1 is essential for maintenance of T cell tolerance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3048–3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Omura T. H., Noguchi A., Johanns C. A., Jeffrey J. J., Partridge N. C. (1994) Identification of a specific receptor for interstitial collagenase on osteoblastic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 24994–24998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walling H. W., Chan P. T., Omura T. H., Barmina O. Y., Fiacco G. J., Jeffrey J. J., Partridge N. C. (1998) Regulation of the collagenase-3 receptor and its role in intracellular ligand processing in rat osteoblastic cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 177, 563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barmina O. Y., Walling H. W., Fiacco G. J., Freije J. M. P., López-Otín C., Jeffrey J. J., Partridge N. C. (1999) Collagenase-3 binds to a specific receptor and requires the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein for internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30087–30093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Imai S.-I., Guarente L. (2010) Ten years of NAD-dependent SIR2 family deacetylases: implications for metabolic diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 212–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piao J., Tsuji K., Ochi H., Iwata M., Koga D., Okawa A., Morita S., Takeda S., Asou Y. (2013) Sirt6 regulates postnatal growth plate differentiation and proliferation via Ihh signaling. Sci. Rep. 3, 3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee H. S., Ka S. O., Lee S.-M., Lee S. I., Park J.-W., Park B. H. (2013) Overexpression of Sirtuin 6 suppresses inflammatory responses and bone destruction in mice with collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 65, 1776–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sebastián C., Satterstrom F. K., Haigis M. C., Mostoslavsky R. (2012) From Sirtuin biology to human diseases: an update. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42444–42452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yamamoto H., Schoonjans K., Auwerx J. (2007) Sirtuin functions in health and disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1745–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zainabadi K. (2009) SirT1 regulates bone mass in vivo through regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cohen-Kfir E., Artsi H., Levin A., Abramowitz E., Bajayo A., Gurt I., Zhong L., D'Urso A., Toiber D., Mostoslavsky R., Dresner-Pollak R. (2011) Sirt1 is a regulator of bone mass and a repressor of Sost encoding for sclerostin, a bone formation inhibitor. Endocrinology 152, 4514–4524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shakibaei M., Shayan P., Busch F., Aldinger C., Buhrmann C., Lueders C., Mobasheri A. (2012) Resveratrol mediated modulation of Sirt-1/Runx2 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: potential role of Runx2 deacetylation. PLoS One 7, e35712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tseng P.-C., Hou S.-M., Chen R.-J., Peng H.-W., Hsieh C.-F., Kuo M.-L., Yen M.-L. (2011) Resveratrol promotes osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells by upregulating RUNX2 gene expression via the SIRT1/FOXO3A axis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2552–2563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dai Z., Li Y., Quarles L. D., Song T., Pan W., Zhou H., Xiao Z. (2007) Resveratrol enhances proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells via ER-dependent ERK1/2 activation. Phytomedicine 14, 806–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bäckesjö C.-M., Li Y., Lindgren U., Haldosén L.-A. (2006) Activation of Sirt1 decreases adipocyte formation during osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elmali N., Esenkaya I., Harma A., Ertem K., Turkoz Y., Mizrak B. (2005) Effect of resveratrol in experimental osteoarthritis in rabbits. Inflamm. Res. 54, 158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pacholec M., Bleasdale J. E., Chrunyk B., Cunningham D., Flynn D., Garofalo R. S., Griffith D., Griffor M., Loulakis P., Pabst B., Qiu X., Stockman B., Thanabal V., Varghese A., Ward J., Withka J., Ahn K. (2010) SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8340–8351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yoshizaki T., Schenk S., Imamura T., Babendure J. L., Sonoda N., Bae E. J., Oh D. Y., Lu M., Milne J. C., Westphal C., Bandyopadhyay G., Olefsky J. M. (2010) SIRT1 inhibits inflammatory pathways in macrophages and modulates insulin sensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E419–E428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang J., Wang N., Li J., Zhang J., Feng P. (2010) Effects of resveratrol on NO secretion stimulated by insulin and its dependence on SIRT1 in high glucose cultured endothelial cells. Endocrine 37, 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Breen D. M., Sanli T., Giacca A., Tsiani E. (2008) Stimulation of muscle cell glucose uptake by resveratrol through sirtuins and AMPK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374, 117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knight C. M., Gutierrez-Juarez R., Lam T. K. T., Arrieta-Cruz I., Huang L., Schwartz G., Barzilai N., Rossetti L. (2011) Mediobasal hypothalamic SIRT1 is essential for resveratrol's effects on insulin action in rats. Diabetes 60, 2691–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hubbard B. P., Gomes A. P., Dai H., Li J., Case A. W., Considine T., Riera T. V., Lee J. E., E S. Y., Lamming D. W., Pentelute B. L., Schuman E. R., Stevens L. A., Ling A. J. Y., Armour S. M., Michan S., Zhao H., Jiang Y., Sweitzer S. M., Blum C. A., Disch J. S., Ng P. Y., Howitz K. T., Rolo A. P., Hamuro Y., Moss J., Perni R. B., Ellis J. L., Vlasuk G. P., Sinclair D. A. (2013) Evidence for a common mechanism of SIRT1 regulation by allosteric activators. Science 339, 1216–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fulco M., Cen Y., Zhao P., Hoffman E. P., McBurney M. W., Sauve A. A., Sartorelli V. (2008) Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev. Cell. 14, 661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berndt T. J., Knox F. G., Kempson S. A., Dousa T. P. (1981) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and renal response to parathyroid hormone. Endocrinology 108, 2005–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matsushita T., Sasaki H., Takayama K., Ishida K., Matsumoto T., Kubo S., Matsuzaki T., Nishida K., Kurosaka M., Kuroda R. (2013) The overexpression of SIRT1 inhibited osteoarthritic gene expression changes induced by interleukin-1β in human chondrocytes. J. Orthop. Res. 31, 531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takayama K., Ishida K., Matsushita T., Fujita N., Hayashi S., Sasaki K., Tei K., Kubo S., Matsumoto T., Fujioka H., Kurosaka M., Kuroda R. (2009) SIRT1 regulation of apoptosis of human chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 2731–2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Niederer F., Ospelt C., Brentano F., Hottiger M. O., Gay R. E., Gay S., Detmar M., Kyburz D. (2011) SIRT1 overexpression in the rheumatoid arthritis synovium contributes to proinflammatory cytokine production and apoptosis resistance. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 1866–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gagarina V., Gabay O., Dvir-Ginzberg M., Lee E. J., Brady J. K., Quon M. J., Hall D. J. (2010) SirT1 enhances survival of human osteoarthritic chondrocytes by repressing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B and activating the insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 1383–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Selvamurugan N., Pulumati M. R., Tyson D. R., Partridge N. C. (2000) Parathyroid hormone regulation of the rat collagenase-3 promoter by protein kinase A-dependent transactivation of core binding factor α1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5037–5042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. D'Alonzo R. C., Selvamurugan N., Karsenty G., Partridge N. C. (2002) Physical interaction of the activator protein-1 factors c-Fos and c-Jun with Cbfa1 for collagenase-3 promoter activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 816–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang R., Chen H. Z., Liu J. J., Jia Y. Y., Zhang Z. Q., Yang R. F., Zhang Y., Xu J., Wei Y. S., Liu D. P., Liang C. C. (2010) SIRT1 suppresses activator protein-1 transcriptional activity and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7097–7110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gao Z., Ye J. (2008) Inhibition of transcriptional activity of c-JUN by SIRT1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 376, 793–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]