Abstract

Background

Trauma is the most common cause of mortality among people between the ages of 1 and 45 years, costing Canadians 19.8 billion dollars a year (2004 data), yet half of all patients with major traumatic injuries do not receive evidence-based care, and significant regional variation in the quality of care across Canada exists. Accordingly, our goal is to lead a research project in which stakeholders themselves will adapt evidence-based trauma care knowledge tools to their own varied institutional contexts and cultures. We will do this by developing and assessing the combined impact of WikiTrauma, a free collaborative database of clinical decision support tools, and Wiki101, a training course teaching participants how to use WikiTrauma. WikiTrauma has the potential to ensure that all stakeholders (eg, patients, clinicians, and decision makers) can all contribute to, and benefit from, evidence-based clinical knowledge about trauma care that is tailored to their own needs and clinical setting.

Objective

Our main objective will be to study the combined effect of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 on the quality of care in four trauma centers in Quebec.

Methods

First, we will pilot-test the wiki with potential users to create a version ready to test in practice. A rapid, iterative prototyping process with 15 health professionals from nonparticipating centers will allow us to identify and resolve usability issues prior to finalizing the definitive version for the interrupted time series. Second, we will conduct an interrupted time series to measure the impact of our combined intervention on the quality of care in four trauma centers that will be selected—one level I, one level II, and two level III centers. Participants will be health care professionals working in the selected trauma centers. Also, five patient representatives will be recruited to participate in the creation of knowledge tools destined for their use (eg, handouts). All participants will be invited to complete the Wiki101 training and then use, and contribute to, WikiTrauma for 12 months. The primary outcome will be the change over time of a validated, composite, performance indicator score based on 15 process performance indicators found in the Quebec Trauma Registry.

Results

This project was funded in November 2014 by the Canadian Medical Protective Association. We expect to start this trial in early 2015 and preliminary results should be available in June 2016. Two trauma centers have already agreed to participate and two more will be recruited in the next months.

Conclusions

We expect that this study will add important and unique evidence about the effectiveness, safety, and cost savings of using collaborative platforms to adapt knowledge implementation tools across jurisdictions.

Keywords: interrupted time series, wiki, quality improvement, knowledge translation, trauma care, stakeholder engagement, adapting knowledge tools

Introduction

The Research Question

What Is the Problem to Be Addressed?

Injuries represent a major health and economic burden for Canadians. They are the most common cause of mortality for people between the ages of 1 and 45 years [1], costing Canadians 19.8 billion dollars in 2004 in direct and indirect costs [2,3]. Up to half of all patients with major traumatic injuries do not receive evidence-based recommended care [4-8]. A recent study conducted in partnership with the Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux (INESSS) and funded by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation [5] determined that many trauma practices in Quebec’s trauma centers are substandard because they underuse proven therapies [4,5]. Studies in several other countries have identified adverse events, including death, that occur in trauma centers because of their failure to adopt best practices [9-13]. Aside from underusing proven therapies, there is also evidence of overuse of diagnostic procedures with known side effects, such as full-body computerized tomography (CT) scanning that exposes patients to unnecessary ionizing radiation that may increase the risk of cancer [14,15]. An estimated one million children every year in the US are unnecessarily imaged with CT [16].

Promoting best practices in trauma care has become an urgent and strategic investment for the health of Canadians and others [17,18]. Unfortunately, the implementation of best practices in the chaotic, acute trauma care environment is a difficult task because of three main factors, which are (1) macroenvironmental (eg, lack of financial resources), (2) organizational (eg, unclear definition of responsibilities within trauma team), and (3) professional (eg, resistance to clinical guidelines) [19]. Studying strategies used to implement best practices in trauma care, the Commonwealth Fund study [19] identified that trauma systems needed better knowledge management and coordination of care through well-implemented guidelines (ie, recommendations about what to do), protocols (ie, detailed procedures for how to administer care), and pathways (ie, frameworks for organizing who administers care and why). Moreover, these tools must be flexible and responsive to individual patients and to accumulating bodies of evidence. Many different health organizations have, therefore, started using wikis to manage knowledge and coordinate care [20-28]. Increasingly popular among health professionals [29-32], wikis are websites based on a novel technology that allow people to view and edit the website’s content, with viewing and editing privileges determined by different levels of access. Wikipedia—the best-known wiki—has 365 million visitors per month, is the sixth-most popular website in the world and its medical articles, available in 271 languages, are viewed about 150 million times per month [33].

In partnership with our team of researchers, the INESSS in Quebec is exploring how wikis could be used to improve the delivery of care to trauma patients. The INESSS oversees the quality of trauma care in the province of Quebec, Canada. It is also the accreditation body that designates different trauma center levels. This organization has expressed the need to explore wikis as a solution to improve the quality of care in trauma. To this end, we have conducted a scoping review that found that wikis could be effective in supporting the implementation of best practices in health care [34-39]. We also conducted a survey that identified that trauma professionals are willing to use wikis and that they share many positive beliefs about using them [40]. Specifically, wikis could serve as centralized knowledge management systems helping clinicians and decision makers coordinate the implementation of best practices by collaboratively building knowledge translation (KT) tools (eg, guidelines, protocols, pathways, and patient decision aids) that meet their needs [41-45] and monitor their use using novel Web metrics [46,47]. Wikis’ other interesting features included their low cost [40,48-51], their broad and global availability [33], their adaptability to local practices, and their capacity to empower stakeholders [52-54]. Wikis were perceived to facilitate the sharing and updating of KT tools by different professionals and to help clinicians working in rural areas where access to specialized care is limited [55,56].

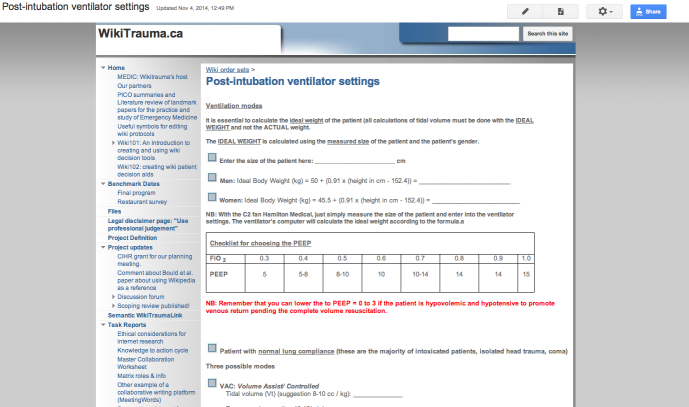

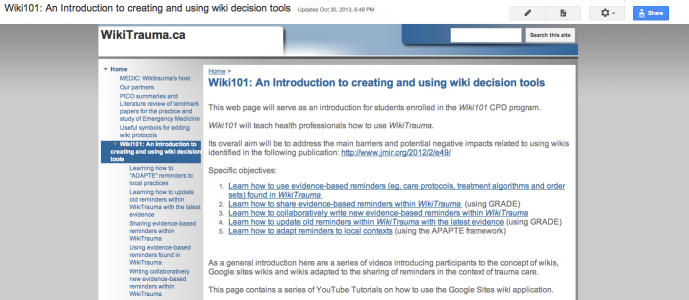

Building on these results, we held a meeting funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) in May 2014 in partnership with the INESSS, the Trauma Association of Canada, and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada to plan a study to evaluate WikiTrauma (see Figure 1), a wiki we created to promote best practices in trauma care. At this planning meeting we decided to study its implementation in a limited number of Quebec trauma centers as a first trial for this novel intervention. We also decided to create Wiki101 (see Figure 2), a theory-based continuing professional development (CPD) program, that will train participants at the selected trauma centers to use WikiTrauma effectively and safely in order to create and share different types of KT tools (eg, care protocols, order sets, and patient decision aids).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of WikiTrauma order set.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Wiki101 training program.

Thus, in partnership with the INESSS and in collaboration with our other WikiTrauma partners, we propose an interrupted time series to measure the combined effect of Wiki101 and WikiTrauma on the quality of trauma care in four trauma centers in Quebec. We also propose to conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation in parallel with this trial to explore possible causal mechanisms about how our combined intervention succeeds—or fails—to lead to improved quality of trauma care.

What Are the Principal Research Questions to Be Addressed?

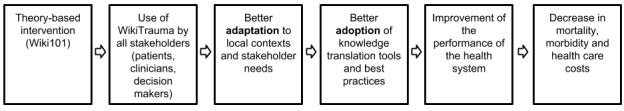

Ultimately, we seek to test our hypothesis that our theory-based intervention (Wiki101) in combination with the use of WikiTrauma will result in better adoption of best practices in trauma care in Canada (see the conceptual framework in Figure 3), safer care (ie, fewer complications), improved patient outcomes, and less costly care.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework underlying the proposed mechanism of action for the intervention.

Why Is This Project Needed Now?

Getting new evidence into health care practice is a slow and challenging process [57-65]. There is an ongoing and urgent need to find effective and low-cost methods of promoting best practices in all areas of health care [65-67] and, particularly, into interprofessional settings such as trauma care [17,68-72]. Recognizing that wikis capitalize on the free and open access to information, scientists, opinion leaders, and patient advocates have called for more research to determine whether wikis can equip decision-making constituencies to improve the delivery of health care [33,73], decrease its cost [49,74], and improve access to knowledge within developing countries [33,75-77]. Moreover, wikis are increasingly being used in health care by different academic institutions [32,41,78-81], health organizations [20,22,25,82,83], and health professionals [84-86] to share and disseminate information. As well, the principal knowledge user involved in our project (INESSS) is planning to use a wiki to promote best practices in trauma care, but would like to have more evidence about their use. Our CIHR-funded scoping review [34] confirmed that wikis have tremendous potential for improving the delivery of health care, but that a rigorous prospective trial to evaluate their effectiveness at implementing best practices is outstanding. Both our review and our survey identified an important need to test a theory-based approach addressing the main barriers that are preventing wikis from widely benefiting our health care system. The barriers most frequently mentioned, in order of frequency, were unfamiliarity with wikis, time constraints, lack of self-efficacy (ie, belief in one’s competence to use a wiki), and lack of access to a useful wiki containing reliable information for bedside decision making. For these reasons, we have designed WikiTrauma—a wiki promoting best practices—and Wiki101—a theory-based intervention—to maximize the potential benefits, to address the main barriers, and prevent any potential negative impacts of using a wiki to promote best practices in trauma care. In summary, there is sufficient evidence to support the conduct of this prospective interrupted time series for testing our novel intervention, which will combine a wiki to promote best practices in trauma care and a theory-based implementation strategy designed to maximize its benefit. This trial will inform our knowledge users about the impact of the combined effect of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 on the implementation of best practices in trauma care.

Best Practices in Trauma Care

Barriers to Implementing Best Practices in Trauma Care

Various aspects of trauma care can impede best practices [13]. Trauma professionals must often make quick decisions, mostly based on intuitive reasoning [87], which is fast, impulsive, effortless, and reflexive. While this serves trauma care well, it is also prone to error. Reminders (eg, care protocols) are knowledge tools [88] that improve intuitive decision making [87]. A recent systematic review indicated that noncomputerized reminders had the potential to improve practices in critical care [70]. Computerized reminders and clinical decision support systems, which were excluded from the previous review, offer different KT opportunities in trauma centers' hectic environments [89-91].

Systematic Reviews About Computerized Decision Support Systems and Barriers to Their Adoption

Systematic reviews indicate that computer-based reminders are effective interventions for fostering best practices in a variety of clinical areas [26,92-100], including in acute care [89]. Such reminders range from simple prescribing alerts to more sophisticated computer systems that support decision making. This said, health professionals have rejected many computer-based reminder systems on the grounds that they are slow, incompatible with work processes, unable to adapt to local practices, difficult to access, and/or are costly to implement [90,91,101-105]. Finding innovative ways to involve end users in designing, implementing, and evaluating reminder systems is key to increasing their use and their impact on health outcomes. Novel collaborative applications like wikis offer an easy and inexpensive solution [31].

Theoretical Framework Supporting the Use of Wikis as a Driver for Change in Health Systems

According to behavior-change theories, self-efficacy—roughly defined as an individual’s belief in his/her own competence—is one of the most important cognitive determinants of behavior [106-109]. By involving health professionals in sharing, updating, and creating practical reminders, wikis—highly accessible, interactive vehicles of communication—have the potential to increase professionals’ self-efficacy in using reminders [29,30,74].

Rising Use of Wikis in the Health Care System

Studies have found that 70% of junior physicians (mostly residents) use Wikipedia weekly [84], that 50-70% of physicians use it as a source of information in providing care [33], and that 35% of pharmacists refer to it for drug information [85]. Different large health care organizations (eg, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health [110-112], US National Institutes of Health [20,113], The Cochrane Collaboration [22], World Health Organization [83], and several universities [32,41,78-81,114]) are exploring the use of wikis and/or Wikipedia for different purposes. There is a rising use of wikis in health care and, consequently, increased potential safety risks involved with using nonvalidated information for the care of patients. Therefore, we believe there is an urgent need to evaluate the positive benefits wikis could provide in improving the quality of care, while limiting the potential negative effects. We intend to do this by conducting a rigorous and well-planned prospective trial in the controlled setting of a closed wiki (WikiTrauma) managed by strong central leadership (INESSS).

Objectives

Our main objective will be to study the combined effect of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 on the quality of care in four trauma centers in Quebec using an interrupted time series design. Our secondary objectives will be (1) to evaluate the impact of our intervention on mortality, rate of complications, length of stay, and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), (2) to evaluate participants' opinions about the combined intervention—Wiki101 and WikiTrauma, (3) to evaluate the quality of the different knowledge tools developed in WikiTrauma, and (4) to estimate the costs saved by sharing the different knowledge tools within WikiTrauma.

Methods

Pilot-Testing of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 Before the Prospective Trial

In consultation with two human factors specialists (HW, ST) and using the versions of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 developed at the planning meeting, we will further refine WikiTrauma and Wiki101 by employing user-centered design methods focused on our users' needs [115,116]. A rapid, iterative prototyping process with 15 health professionals from nonparticipating centers will allow us to efficiently identify and resolve usability issues prior to finalizing the definitive version of WikiTrauma and Wiki101 for the interrupted time series [117,118].

What Is the Proposed Trial Design?

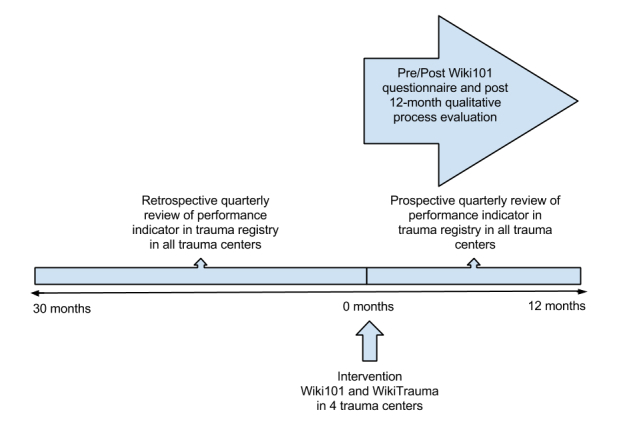

This study will be an interrupted time series with a parallel, theory-based process evaluation alongside the trial (see Figure 4). In the context of quality improvement, the interrupted time series is a simple but powerful tool used for evaluating the impact of a quality improvement program [119]. Our time series—repeated observations of the quality of care collected over time—will be divided into two segments. The first segment will comprise 10 retrospective, quarterly measurements of the quality of care measured before our intervention (a period of 30 months), and the second segment will be four prospective, quarterly quality of care measurements after our intervention (12 months). There are 57 adult-designated trauma centers of varying levels in Quebec—three level I, 26 level II, and 28 level III trauma centers. Four trauma centers will be selected in Université Laval's trauma network. We already identified one level I trauma center and a level II trauma center as participants. We will recruit two level III centers to complete our targeted sample of participating centers. Participants will not be blinded to their study assignment, however, all analyses will be blinded. The control group will comprise all of the 53 remaining adult trauma centers in the province.

Figure 4.

Diagram representing the interrupted times series design.

What Are the Planned Trial Interventions?

Experimental Group

Participants from trauma centers assigned to the experimental group will receive a password to access and complete the Wiki101 course and to use WikiTrauma. They will receive three reminders at 2-week intervals to complete Wiki101. Before and after each Wiki101 course, participants will be administered a validated questionnaire to measure changes in opinion and beliefs about using WikiTrauma. Questionnaires will also be repeated after the prospective 12-month period. After each course, participants will also receive a 2-week reminder about skills taught during the course.

Control Group

Participants in the control group will receive an email promoting access to the regular INESSS webpage and will also receive three reminders at 2-week intervals to access the website. They will not have access to view or edit WikiTrauma.

Management of WikiTrauma During the Trial

For the purpose of this trial, to monitor its use, and ensure its quality, access to WikiTrauma will be protected by password.

Quality of Information Monitoring

Since the wiki content can be constantly changed by the participants, the quality of information and the strength of evidence will be assessed weekly by a medical expert (JL) and monthly by the steering committee using a standardized evaluation form. This committee will edit any serious deviations from recognized standards of care and will flag controversial topics to stimulate discussion within the wiki community.

What Are the Proposed Practical Arrangements for Allocating Participants to Trial Groups?

All professionals and decision makers working in the four participating trauma centers will be eligible to participate. With the help of the local leaders on the trauma committee, we will recruit as many clinicians (eg, physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists) and decision makers (eg, heads of Emergency Department, Surgery Department, and Critical Care Department) as possible. All participating trauma committees will also be asked to designate five patient representatives to take part in the construction of various tools designed for their use (eg, decision aids and patient handouts). In each center, we will present the project to the local representatives of each trauma committee. We will provide a hands-on Wiki101 session to all the members of the local trauma committee and the five patient representatives, who will then become the local leaders able to teach their colleagues how to access the wiki and contribute to its content. An online version of Wiki101 will be available to all clinicians and patient representatives for future consultation.

What Are the Proposed Methods for Protecting Against Sources of Bias?

Although blinding of the participants and randomization are not feasible in this small trial, we will mobilize all efforts to minimize any other sources of bias. All data collectors (medical archivists) will be blinded to the allocation group. Throughout our study, we will prevent contamination by protecting Wiki101 and WikiTrauma by password and note any potential competing intervention. We will also identify any professional working in more than one participating trauma center to consider the impact of this potential source of bias. Wiki101 will be a standardized online training program. We will encourage all participants to complete all 12 months of the study. To minimize a potential Hawthorne effect, our control group will receive an invitation to consult the INESSS website at the beginning of the study. Moreover, our proposed study design of an interrupted time series provides the advantage of controlling for secular trends in the data.

What Are the Planned Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria?

Inclusion Criteria

We will select four trauma centers—one level I, one level II, and two level III trauma centers. The two level III centers will be identified by the authors based on their willingness to participate and collaborate with the other trauma centers for the 12-month project. At the individual level, study participants must be decision makers (eg, trauma program coordinators) or health care professionals (eg, emergency physicians, critical care physicians, trauma surgeons, nurses, respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, or pharmacists). Patient representatives will be selected without any restrictions or limitations with regard to their qualifications. These patient representatives could also be caregivers to existing trauma patients. Health care professional students and trainees (eg, residents, medical students, and nursing students) will have the same access to WikiTrauma and Wiki101 as fully certified professionals.

Exclusion Criteria

At the cluster level, a trauma center will not be eligible to participate if more than 50% of the members of the local trauma committee refuse to participate. Reasons for exclusion or refusal to participate will be documented. Pediatric trauma centers will be excluded.

What Is the Proposed Duration of the Treatment Period?

Wiki101 will take 3 hours to complete for each participant and they will have access to use Wiki101 and WikiTrauma for 12 months.

What Is the Proposed Frequency and Duration of Follow-Up?

Aside from our pre- and post-Wiki101 questionnaire and the 2-week reminder after completing Wiki101, we will only administer a final questionnaire after the 12-month treatment period.

What Are the Proposed Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures?

The primary outcome measure will be the change over time in a validated, composite performance indicator score based on 15 process performance indicators found in the Quebec Trauma Registry [4]. The secondary outcome measures will be rates of complications, length of stay, mortality, and the FIM. These will also be found in the Quebec Trauma Registry. Other secondary outcome measures will be the following: (1) intention to use WikiTrauma and the sociocognitive determinants of this intention, (2) the self-reported use of WikiTrauma in clinical practice, (3) the actual frequency of WikiTrauma use—number of visits, length of visits, number of visitors, and number of unique visitors, (4) the quality of information contained within WikiTrauma, (5) the frequency of content modifications—number of visitors having modified content, number of pages modified, number of new pages created, and number of pages having generated an edit war, (6) participants’ comments about what worked and improvements suggested, (7) the estimated annual cost of maintaining WikiTrauma, (8) the cost of delivering Wiki101, (9) the estimated cost of creating new knowledge-decision tools, and (10) the estimated cost of updating old knowledge-decision tools.

How Will the Outcome Measures Be Measured at Follow-Up?

We will measure quarterly composite performance scores from the Quebec Trauma Registry for all 57 adult trauma centers. Data in the Quebec Trauma Registry is routinely collected in all Quebec trauma centers every 3 months. The composite performance score is calculated as the average of 15 other indicators routinely collected in the Quebec Trauma Registry [4]. This score has good discrimination, construct validity, criterion predictive validity, and forecasting properties [120]. Mortality rates, complication rates (for delirium, pneumonia, and deep venous thrombosis), length of stay, and FIM will also be measured on a quarterly basis for all 57 trauma centers from routinely collected data in the Quebec Trauma Registry. The intention to use WikiTrauma will be measured by a validated questionnaire [40]. The actual wiki use and the frequency of content modification will be measured on a quarterly basis using a Google Analytics account linked to WikiTrauma.

Safety Monitoring and Quality Assurance

Since participants can change wiki content, the quality of information and the strength of evidence will be assessed weekly by an INESSS medical expert, and monthly by the scientific committee using a standardized evaluation form. This committee will edit any serious deviations from recognized standards of care and will flag controversial topics to stimulate discussion within the wiki community. The quality of different KT tools will be evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations [121]. To estimate the amount of supervision that was needed by the medical supervisor at INESSS, we will document the number of pages modified and created, and the number of edit wars. In order to ensure that only high-quality and officially approved knowledge tools will be used in clinical practice, wiki pages that are not approved for clinical use by local trauma committees will be color-coded in RED with a warning message to say that the page is currently under construction. Pages that are approved by local trauma committees will be color-coded in GREEN for use only in the trauma center that approved the page. To estimate activity that was generated by our wiki and the amount of supervision that was needed during this trial by the medical supervisor at INESSS, we will study the wiki’s revision history page to document the number of visitors having modified the content, the number of pages modified, the number of new pages created, and the number of pages having generated an edit war [122] on a quarterly basis. An edit war will be defined as more than three reverts by a single editor on a single page within a 24-hour period. An edit that undoes other editors' actions will count as a revert. All cases of potential patient harm reported by any quality assurance committee or participant will be described and declared.

Sample Size

As a rule of thumb for an interrupted time series, 10 measurement points before and 10 measurements after an intervention provides 80% power to detect a change in level of 5 standard deviations (of the predata) only if the autocorrelation is greater than .4 (ie, extent to which data collected close together in time are correlated with each other) [123]. In our case, we will be able to measure 10 measurement points before (30 months), but the period of observation after our intervention will be limited to 12 months—4 quarters is equal to 4 measurement points. This will decrease our power, but we are currently applying for funding from other sources to collect data for a total of 32 postintervention months (10 quarters).

Data Analysis

Segmented regression will be used to measure, statistically, the changes in level and slope in the postintervention period compared to the preintervention period [119]. Thus, we will present a regression model with different intercept and slope coefficients for the pre- and postintervention time periods. We will compare the changes in quality of care measured at our four intervention trauma centers to the changes in quality of care measured at the other 53 trauma centers where no experimental intervention occurred. During the implementation period of WikiTrauma, we will continue to measure the impact on the quality of care. However, we will only proceed to compare the change in slope in the postintervention period once WikiTrauma has been fully implemented. We will use a Durbin-Watson test to verify the presence of autocorrelation and use an autoregressive error model to correct for this serial correlation.

Qualitative Content Analysis

We plan to enlist two researchers experienced in qualitative content analysis who will review participants' written questionnaire answers to identify the barriers in using our intervention. They will also try to understand how our combined intervention succeeded—or failed—to lead to improved quality of trauma care. When consensus between the two reviewers is not possible, a third reviewer will be consulted.

Study Duration

This project is planned to last 18 months. We have planned 3 months to implement the trial, including ethics approval in the four designated trauma centers and for delivering Wiki101 to the four local trauma committees. We will analyze all retrospective data obtained from the Quebec Trauma Registry in the first 3 months of our study and every 3 months thereafter for a total of 12 months. The last 3 months will be used to prepare our datasets, conduct our various analyses, and write our final report.

Ethical Considerations

We will apply for ethical approval to conduct this trial in all four participating trauma centers. All participants will be asked to consent before accessing the wiki for the first time and before any questionnaire administration. Local trauma committees will be consulted and we will obtain approval and support from each trauma center's chief executive officer. Patient participants will also be asked to complete a consent form before participating in any phase of this trial.

A legal disclaimer will also be posted on the wiki site asking participants to always use their clinical judgement first. Clinical judgement should never be replaced by any information found in a protocol based in WikiTrauma. In addition, clinicians should only use the wiki pages that have been approved by their local trauma committee.

All personal information on study participants will remain anonymous and we will not publish the names of any of the participating trauma centers. All sensitive information will be kept in a locked filing cabinet at the principal investigator’s (PI) research center or in a password-protected computer at the research center.

Results

This project was funded in November 2014 by the Canadian Medical Protective Association. We expect to start this trial in early 2015 and preliminary results should be available in June 2016. Two trauma centers have already agreed to participate and two more will be recruited in the next months.

Discussion

We expect that this study will yield important and unique evidence about the effectiveness, safety, and cost savings of using collaborative platforms to adapt knowledge-implementation tools across jurisdictions. A recent scoping review had not identified any prospective studies analyzing the impact of a wiki intervention on the quality of care in any field of health care [34]. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this will be the first interrupted time series evaluating the impact of a wiki on the implementation of best practices in trauma care. Patient safety science will gain from this project because we will investigate how WikiTrauma can help standardize care across our trauma system. This will be done by providing a unique collaborative tool that allows centers to learn from others in the implementation of evidence-based knowledge translation tools (eg, care protocols, order sets, and patient decision aids). WikiTrauma will also offer a unique knowledge-management platform to support the central leadership provided by provincial decision makers, such as the Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux. This study will also provide a new platform for effective local collaboration between professionals, decision makers, and patients. Public- and patient-involvement programs will gain insight about using wikis to engage patients and the public in the implementation of best practices. Interprofessional education and quality-improvement programs will also learn about how these novel platforms can support collaboration and coordination in the implementation of novel best practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following agencies for funding this project: the Canadian Medical Protective Association, Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé (Career Scientist Award, 24856 and Establishment of young researchers—Junior 1 grant, 24856), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Planning Grant, RN201023 - 309271), and the CSSS Alphonse-Desjardins—Centre hospitalier affilié universitaire (CHAU) de Lévis. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group for supporting the development of this protocol and Dr Shane English for having peer-reviewed our manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Louisa Blair and Sandra Owens for editing the manuscript. In addition, the authors would like to thank Marie Robert from the Fondation NeuroTrauma Marie-Robert, François Belleau, Jacob Orlowitz, Patrice Di Marcantonio, Mathieu Vézina, Marcel Rheault, Sylvain Croteau, Jean-Luc Morin, Saileth Ramirez, Yves Daigle, Susie Gagnon, Claudine Blanchet, Amina Belcaïd, Charles Lacroix, Jean-Michel Garro, Amélie Bujold, Rémi Blanchette, Jean-Daniel Boutin, Dr Richard Boisvert, Dr Nelson Piché and Dr Stéphane Panic for participating in the development of this project.

Abbreviations

- CHAU

Centre hospitalier affilié universitaire

- CHU

Centre hospitalier universitaire

- CIHR

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CPD

continuing professional development

- CSSS

Centre de santé et services sociaux

- CT

computerized tomography

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- INESSS

Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux

- KT

knowledge translation

- PI

principal investigator

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Christian Chabot works for Telus Health. Telus Health offers many different health information technology solutions, including electronic medical records. Telus has not had any role in influencing the content of this protocol. None of the other authors have received any honorariums for the conduct of this trial from Telus. Richard Grenier works for Thales Canada as Director of Research and Technology. Thales has provided in-kind financial support for the development of the wiki, but has not had any role in influencing the content of this protocol. None of the other authors have received any honorariums for the conduct of this trial from Thales.

References

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. [2015-01-11]. Leading causes of death and hospitalization in Canada http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/lcd-pcd97/table1-eng.php.

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. 1998. [2015-01-11]. The economic burden of injury in Canada http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/injury-bles/ebuic-febnc/index-eng.php.

- 3.The Economic Burden of Injury in Canada. Toronto, Ontario: SMARTRISK; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore L, Lavoie A, Sirois MJ, Amini R, Belcaïd A, Sampalis JS. Evaluating trauma center process performance in an integrated trauma system with registry data. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013 Apr;6(2):95–105. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110754. http://www.onlinejets.org/article.asp?issn=0974-2700;year=2013;volume=6;issue=2;spage=95;epage=105;aulast=Moore. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavoie A, Moore L, Lapointe J, Bourgeois G, Fréchette P. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. 2010. Sep 01, [2015-01-11]. Performance d'un continuum de services en traumatologie http://www.fcass-cfhi.ca/SearchResultsNews/09-04-22/8f0a9595-e93b-4678-a2d7-a3bfb20cfba4.aspx.

- 6.Simons R, Eliopoulos V, Laflamme D, Brown DR. Impact on process of trauma care delivery 1 year after the introduction of a trauma program in a provincial trauma center. J Trauma. 1999 May;46(5):811–815. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kortbeek JB, Buckley R. Trauma-care systems in Canada. Injury. 2003 Sep;34(9):658–663. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons R, Kirkpatrick A. Assuring optimal trauma care: the role of trauma centre accreditation. Can J Surg. 2002 Aug;45(4):288–295. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0036324042&partnerID=40&md5=11492ba5b7de02f0e6fb1747575fa7a9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Famularo G, Salvini P, Terranova A, Gerace C. Clinical errors in emergency medicine: experience at the emergency department of an Italian teaching hospital. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Nov;7(11):1278–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamilton JD. The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust. 1995 Nov 6;163(9):458–471. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt HH. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7;324(6):370–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Barnes BA, Hebert L, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt H. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7;324(6):377–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruen RL, Jurkovich GJ, McIntyre LK, Foy HM, Maier RV. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006 Sep;244(3):371–380. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234655.83517.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez RM, Anglin D, Langdorf MI, Baumann BM, Hendey GW, Bradley RN, Medak AJ, Raja AS, Juhn P, Fortman J, Mulkerin W, Mower WR. NEXUS chest: validation of a decision instrument for selective chest imaging in blunt trauma. JAMA Surg. 2013 Oct;148(10):940–946. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakorafas LU, Rogers FB. Pan-computed tomography for blunt trauma patients may be overused. J Trauma. 2010 May;68(5):1266. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d9d7d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 29;357(22):2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green SE, Bosch M, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA, Tavender EJ, Bragge P, Chau M, Pitt V, Rosenfeld JV, Gruen RL. Improving the care of people with traumatic brain injury through the Neurotrauma Evidence Translation (NET) program: protocol for a program of research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-74. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/7//74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brain and Spinal Injury Center. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco General Hospital, University of California at San Francisco; [2015-01-11]. http://www.brainandspinalinjury.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.March A. The Commonwealth Fund. 2006. Jun, [2015-01-28]. Facilitating implementation of evidence-based guidelines in hospital settings: learning from trauma centers http://www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/930_March_facilitating_implementation_final_web_02.pdf.

- 20.PubMed Health Blog. 2013. Jul 13, [2015-01-11]. Wikipedia visits the National Library of Medicine and NIH http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/blog/2013/07/Wikipedia-visits-National-Library-of-Medicine-NIH/

- 21.Wiki Urgence HDL Informatisation. [2015-01-11]. Urgence HDL informatisation https://sites.google.com/site/urgencehdlinformatisation/

- 22.Bastian H, Heilman J, Tharyan P. 21st Cochrane Colloquium. 2013. [2015-01-11]. Wikipedia meets Cochrane: working to get better evidence into mass use http://abstracts.cochrane.org/2013-québec-city/wikipedia-meets-cochrane-working-get-better-evidence-mass-use.

- 23.National Institutes of Health. [2015-01-11]. Guidelines for participating in Wikipedia from NIH http://www.nih.gov/icd/od/ocpl/resources/wikipedia/

- 24.Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux, Quebec. [2015-01-11]. Healthcare professionals’ intentions to use wiki-based reminders to promote best practices in trauma care: a survey protocol http://fecst.inesss.qc.ca/fr/archives/nouvelle/article/new-study-healthcare-professionals-intentions-to-use-wiki-based-reminders-to-promote-best-practi-1.html.

- 25.The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) 2011. Mar 02, [2015-01-11]. CADTH systematic review published as wiki http://www.cadth.ca/en/media-centre/2011/3/2/cadth-systematic-review-published-as-wiki.

- 26.Berner ES. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2009. Jun, [2015-01-11]. Clinical decision support systems: State of the Art http://healthit.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/page/09-0069-EF_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erinoff E. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2009. [2015-01-11]. Feasibility study of a wiki collaboration platform for systematic review http://archive.ahrq.gov/news/events/conference/2009/erinoff/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Network for International Surgery. [2015-01-11]. Primary surgery wiki http://www.cnis.ca/what-we-do/african-information-program/primary-surgery-wiki/

- 29.McLean R, Richards BH, Wardman JI. The effect of Web 2.0 on the future of medical practice and education: Darwikinian evolution or folksonomic revolution? Med J Aust. 2007 Aug 6;187(3):174–177. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tapscott D, Williams AD. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything. New York, NY: Portfolio; 2007. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright A, Bates DW, Middleton B, Hongsermeier T, Kashyap V, Thomas SM, Sittig DF. Creating and sharing clinical decision support content with Web 2.0: Issues and examples. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu LF, Young C, Zamora A, Kurup V, Macario A. Anesthesia 2.0: Internet-based information resources and Web 2.0 applications in anesthesia education. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010 Apr;23(2):218–227. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328337339c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heilman JM, Kemmann E, Bonert M, Chatterjee A, Ragar B, Beards GM, Iberri DJ, Harvey M, Thomas B, Stomp W, Martone MF, Lodge DJ, Vondracek A, de Wolff JF, Liber C, Grover SC, Vickers TJ, Meskó B, Laurent MR. Wikipedia: a key tool for global public health promotion. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1589. http://www.jmir.org/2011/1/e14/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Archambault PM, van de Belt TH, Grajales FJ 3rd, Faber MJ, Kuziemsky CE, Gagnon S, Bilodeau A, Rioux S, Nelen WL, Gagnon MP, Turgeon AF, Aubin K, Gold I, Poitras J, Eysenbach G, Kremer JA, Légaré F. Wikis and collaborative writing applications in health care: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(10):e210. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2787. http://www.jmir.org/2013/10/e210/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Archambault PM, van de Belt TH, Grajales FJ 3rd, Eysenbach G, Aubin K, Gold I, Gagnon MP, Kuziemsky CE, Turgeon AF, Poitras J, Faber MJ, Kremer JA, Heldoorn M, Bilodeau A, Légaré F. Wikis and collaborative writing applications in health care: a scoping review protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012;1(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/resprot.1993. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2012/1/e1/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phadtare A, Bahmani A, Shah A, Pietrobon R. Scientific writing: a randomized controlled trial comparing standard and on-line instruction. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-27. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/9/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moeller S, Spitzer K, Spreckelsen C. How to configure blended problem based learning-results of a randomized trial. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):e328–e346. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.490860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ioannis Chiotelis I, Giannakopoulos A, Kalafati M, Koutsouradi M, Kallistratos M, Manolis AJ. Secondary prevention with internet support after an acute coronary syndrome in greek patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18(1):S11. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stutsky BJ. PQDT Open. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest LLC; 2009. [2015-01-12]. Empowerment and leadership development in an online story-based learning community http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/305149816.html?FMT=AI. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Archambault PM, Bilodeau A, Gagnon MP, Aubin K, Lavoie A, Lapointe J, Poitras J, Croteau S, Pham-Dinh M, Légaré F. Health care professionals' beliefs about using wiki-based reminders to promote best practices in trauma care. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e49. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1983. http://www.jmir.org/2012/2/e49/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohli MD, Bradshaw JK. What is a wiki, and how can it be used in resident education? J Digit Imaging. 2011 Feb;24(1):170–175. doi: 10.1007/s10278-010-9292-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20386950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yates D, Paquette S. Emergency knowledge management and social media technologies: A case study of the 2010 Haitian Earthquake. Int J Inf Manage. 2011;31(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu R, Crotty B. Wikis to better manage shared information in a hospitalist group. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2011 Abstracts: Research, Innovations, Clinical Vignettes Competition; Hospital Medicine 2011; May 10–13, 2011; Grapevine, TX. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. May 10, pp. S140–S141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown T, Findlay M, von Dincklage J, Davidson W, Hill J, Isenring E, Talwar B, Bell K, Kiss N, Kurmis R, Loeliger J, Sandison A, Taylor K, Bauer J. Using a wiki platform to promote guidelines internationally and maintain their currency: evidence-based guidelines for the nutritional management of adult patients with head and neck cancer. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013 Apr;26(2):182–190. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.den Breejen EM, Nelen WL, Knijnenburg JM, Burgers JS, Hermens RP, Kremer JA. Feasibility of a wiki as a participatory tool for patients in clinical guideline development. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e138. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2080. http://www.jmir.org/2012/5/e138/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varga-Atkins T, Prescott D, Dangerfield P. Encyclopedia of Cyber Behavior. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2012. Cyber behavior with wikis; pp. 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morose T. University of Waterloo. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo; 2007. Sep 21, [2015-01-11]. Using an interactive website to disseminate participatory ergonomics research findings: An exploratory study https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/3274. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giustini D. How Web 2.0 is changing medicine. BMJ. 2006 Dec 23;333(7582):1283–1284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39062.555405.80. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17185707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandl KD, Kohane IS. Tectonic shifts in the health information economy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 17;358(16):1732–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0800220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Archambault PM, Blouin D, Poitras J, Fountain RM, Fleet R, Bilodeau A, Légaré F. Emergency medicine residents' beliefs about contributing to a Google Docs presentation: a survey protocol. Inform Prim Care. 2011;19(4):207–216. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v19i4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JY, Gudewicz TM, Dighe AS, Gilbertson JR. The pathology informatics curriculum wiki: Harnessing the power of user-generated content. J Pathol Inform. 2010;1 doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.65428. http://www.jpathinformatics.org/article.asp?issn=2153-3539;year=2010;volume=1;issue=1;spage=10;epage=10;aulast=Kim. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyrkjebø JM, Brattebø G, Smith-Strøm H. Improving patient safety by using interprofessional simulation training in health professional education. J Interprof Care. 2006 Oct;20(5):507–516. doi: 10.1080/13561820600918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cole E, Crichton N. The culture of a trauma team in relation to human factors. J Clin Nurs. 2006 Oct;15(10):1257–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Perrier L. Effectiveness of pre-licensure interprofessional education and post-licensure collaborative interventions. J Interprof Care. 2005 May;19 Suppl 1:148–165. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hameed SM, Schuurman N, Razek T, Boone D, Van Heest R, Taulu T, Lakha N, Evans DC, Brown DR, Kirkpatrick AW, Stelfox HT, Dyer D, van Wijngaarden-Stephens M, Logsetty S, Nathens AB, Charyk-Stewart T, Rizoli S, Tremblay LN, Brenneman F, Ahmed N, Galbraith E, Parry N, Girotti MJ, Pagliarello G, Tze N, Khwaja K, Yanchar N, Tallon JM, Trenholm JA, Tegart C, Amram O, Berube M, Hameed U, Simons RK, Research Committee of the Trauma Association of Canada Access to trauma systems in Canada. J Trauma. 2010 Dec;69(6):1350–1361. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e751f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleet R, Archambault P, Plant J, Poitras J. Access to emergency care in rural Canada: should we be concerned? CJEM. 2013 Jul;15(4):191–193. doi: 10.2310/8000.121008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F, Davis D, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L, Wensing M, Dijkstra R, Donaldson C. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004 Feb;8(6):1–84. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/volume-8/issue-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ. 1998 Aug 15;317(7156):465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/9703533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995 Nov 15;153(10):1423–1431. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=reprint&pmid=7585368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Colquhoun HL, Brehaut JC, Sales A, Ivers N, Grimshaw J, Michie S, Carroll K, Chalifoux M, Eva KW. A systematic review of the use of theory in randomized controlled trials of audit and feedback. Implement Sci. 2013;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-66. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/8//66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O'Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jan;6:CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flodgren G, Rojas-Reyes MX, Cole N, Foxcroft DR. Effectiveness of organisational infrastructures to promote evidence-based nursing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD002212. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002212.pub2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22336783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S, Moore K, Wallin L. Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-15. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/2//15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Feb;58(2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization Bridging the “Know–Do” gap. Meeting on Knowledge Translation in Global Health; October 10-12, 2005; Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. http://www.who.int/kms/WHO_EIP_KMS_2006_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Archambault PM, Bilodeau A, Gagnon MP, Aubin K, Lavoie A, Lapointe J, Poitras J, Croteau S, Pham-Dinh M, Légaré F. Health care professionals' beliefs about using wiki-based reminders to promote best practices in trauma care. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e49. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1983. http://www.jmir.org/2012/2/e49/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deneckere S, Euwema M, Lodewijckx C, Panella M, Mutsvari T, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K. Better interprofessional teamwork, higher level of organized care, and lower risk of burnout in acute health care teams using care pathways: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 2013 Jan;51(1):99–107. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182763312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sinuff T, Muscedere J, Adhikari NK, Stelfox HT, Dodek P, Heyland DK, Rubenfeld GD, Cook DJ, Pinto R, Manoharan V, Currie J, Cahill N, Friedrich JO, Amaral A, Piquette D, Scales DC, Dhanani S, Garland A, KRITICAL Working Group‚ the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group‚ the Canadian Critical Care Society Knowledge translation interventions for critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2013 Nov;41(11):2627–2640. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182982b03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S. Knowledge translation and interprofessional collaboration: Where the rubber of evidence-based care hits the road of teamwork. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):46–54. doi: 10.1002/chp.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD002213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Czarnecka-Kujawa K, Abdalian R, Grover SC. The quality of open access and open source Internet material in gastroenterology: Is Wikipedia appropriate for knowledge transfer to patients? Gastroenterology. 2008 Apr;134(4):A-325–A-326. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(08)61518-8. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6WFX-4T3XF3T-1X6/2/5a7ba49a99f8c0dd3dc7c69dd48a3245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eysenbach G. Medicine 2.0: social networking, collaboration, participation, apomediation, and openness. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(3):e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1030. http://www.jmir.org/2008/3/e22/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Silva V, Hanwella R. Why are we copyrighting science? BMJ. 2010;341:c4738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Godlee F, Pakenham-Walsh N, Ncayiyana D, Cohen B, Packer A. Can we achieve health information for all by 2015? Lancet. 2004;364(9430):295–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trevena L. WikiProject medicine. BMJ. 2011;342:d3387. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boulos MN, Maramba I, Wheeler S. Wikis, blogs and podcasts: a new generation of Web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical practice and education. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-41. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/6/41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sandars J, Schroter S. Web 2.0 technologies for undergraduate and postgraduate medical education: an online survey. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Dec;83(986):759–762. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.063123. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18057175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sandars J, Haythornthwaite C. New horizons for e-learning in medical education: ecological and Web 2.0 perspectives. Med Teach. 2007 May;29(4):307–310. doi: 10.1080/01421590601176406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McGee JB, Begg M. What medical educators need to know about Web 2.0. Med Teach. 2008;30(2):164–169. doi: 10.1080/01421590701881673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caputo I. The Washington Post. 2009. Jul 28, [2013-06-11]. NIH refers to 'Wikipedians' for help: scientists learn online etiquette http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/27/AR2009072701912.html.

- 83.ICD11 Beta Draft. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [2013-04-18]. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hughes B, Joshi I, Lemonde H, Wareham J. Junior physician's use of Web 2.0 for information seeking and medical education: a qualitative study. Int J Med Inform. 2009 Oct;78(10):645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brokowski L, Sheehan AH. Evaluation of pharmacist use and perception of Wikipedia as a drug information resource. Ann Pharmacother. 2009 Nov;43(11):1912–1913. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McGowan BS, Wasko M, Vartabedian BS, Miller RS, Freiherr DD, Abdolrasulnia M. Understanding the factors that influence the adoption and meaningful use of social media by physicians to share medical information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e117. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2138. http://www.jmir.org/2012/5/e117/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Croskerry P, Nimmo GR. Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011 Jun;41(2):155–162. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2011.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge Translation in Health Care : Moving From Evidence to Practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell/BMJ; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sahota N, Lloyd R, Ramakrishna A, Mackay JA, Prorok JC, Weise-Kelly L, Navarro T, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, CCDSS Systematic Review Team Computerized clinical decision support systems for acute care management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011;6:91. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-91. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/6//91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lang ES, Wyer PC, Haynes RB. Knowledge translation: closing the evidence-to-practice gap. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Mar;49(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holroyd BR, Bullard MJ, Graham TA, Rowe BH. Decision support technology in knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007 Nov;14(11):942–948. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Feb 14;160(3):301–308. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Buntinx F, Winkens R, Grol R, Knottnerus JA. Influencing diagnostic and preventive performance in ambulatory care by feedback and reminders. A review. Fam Pract. 1993 Jun;10(2):219–228. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wensing M, Grol R. Single and combined strategies for implementing changes in primary care: a literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994 Jun;6(2):115–132. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/6.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mandelblatt J, Kanetsky PA. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance physician screening for breast cancer. J Fam Pract. 1995 Feb;40(2):162–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, Sam J, Haynes RB. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005 Mar 9;293(10):1223–1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998 Oct 21;280(15):1339–1346. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johnston ME, Langton KB, Haynes RB, Mathieu A. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on clinician performance and patient outcome. A critical appraisal of research. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Jan 15;120(2):135–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-2-199401150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005 Apr 2;330(7494):765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15767266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001096.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weingart SN, Toth M, Sands DZ, Aronson MD, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Physicians' decisions to override computerized drug alerts in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Nov 24;163(21):2625–2631. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.21.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stiell IG, Bennett C. Implementation of clinical decision rules in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007 Nov;14(11):955–959. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chan J, Shojania KG, Easty AC, Etchells EE. Does user-centred design affect the efficiency, usability and safety of CPOE order sets? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011 May 1;18(3):276–281. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000026. http://jamia.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21486886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wright A, Sittig DF, Carpenter JD, Krall MA, Pang JE, Middleton B. Order sets in computerized physician order entry systems: an analysis of seven sites. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:892–896. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21347107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, Anandan C, Cresswell K, Bokun T, McKinstry B, Procter R, Majeed A, Sheikh A. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000387. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004 Apr;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;3:36. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-36. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/3//36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005 Feb;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. http://qhc.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15692000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol Internet. 2008;57(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Deshpande A, Khoja S, Lorca J, McKibbon A, Rizo C, Husereau D, Jadad AR. Asynchronous telehealth: a scoping review of analytic studies. Open Med. 2009;3(2):e69–e91. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19946396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Murray S, Giustini D, Loubani T, Choi S, Palepu A. Medical research and social media: Can wikis be used as a publishing platform in medicine? Open Med. 2009;3(3):e121–e122. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21603044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McIntosh B, Cameron C, Singh S, Yu C, Ahuja T, Welton NJ, Dahl M. Second-line therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy: a systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison meta-analysis. Open Med. 2011;5(1):e35–e48. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22046219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.National Institutes of Health. 2011. Mar 02, [2015-01-11]. Guidelines for participating in Wikipedia from NIH http://www.nih.gov/icd/od/ocpl/resources/wikipedia/

- 114.Sandars J, Haythornthwaite C. New horizons for e-learning in medical education: ecological and Web 2.0 perspectives. Med Teach. 2007 May;29(4):307–310. doi: 10.1080/01421590601176406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D, Preece J. Berkshire Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing Group; 2004. User-centered design; pp. 764–768. [Google Scholar]

- 116.usability.gov. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; [2015-01-12]. Research-based Web design and usability guidelines http://www.usability.gov/sites/default/files/documents/guidelines_book.pdf?post=yes. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Faulkner L. Beyond the five-user assumption: benefits of increased sample sizes in usability testing. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2003 Aug;35(3):379–383. doi: 10.3758/bf03195514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lindgaard G, Chattratichart J. Usability testing: what have we overlooked?. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; April 28 - May 3, 2007; San Jose, CA. New York, NY: ACM Press; 2007. pp. 1415–1424. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1240624.1240839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013 Dec;13(6 Suppl):S38–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moore L, Lavoie A, Sirois MJ, Belcaid A, Bourgeois G, Lapointe J, Sampalis JS, Le Sage N, Émond M. A comparison of methods to obtain a composite performance indicator for evaluating clinical processes in trauma care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 May;74(5):1344–1350. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828c32f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008 Apr 26;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18436948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yasseri T, Sumi R, Rung A, Kornai A, Kertész J. Dynamics of conflicts in Wikipedia. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038869. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ramsay C, Matowe L, Grilli R, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(4):613–623. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]