Abstract

Background and Purpose

Neurodegenerative diseases are a major problem afflicting ageing populations; however, there are no effective treatments to stop their progression. Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are common factors in their pathogenesis. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) is the master regulator of oxidative stress, and melatonin is an endogenous hormone with antioxidative properties that reduces its levels with ageing. We have designed a new compound that combines the effects of melatonin with Nrf2 induction properties, with the idea of achieving improved neuroprotective properties.

Experimental Approach

Compound ITH12674 is a hybrid of melatonin and sulforaphane designed to exert a dual drug–prodrug mechanism of action. We obtained the proposed hybrid in a single step. To test its neuroprotective properties, we used different in vitro models of oxidative stress related to neurodegenerative diseases and brain ischaemia.

Key Results

ITH12674 showed an improved neuroprotective profile compared to that of melatonin and sulforaphane. ITH12674 (i) mediated a concentration-dependent protective effect in cortical neurons subjected to oxidative stress; (ii) decreased reactive oxygen species production; (iii) augmented GSH concentrations in cortical neurons; (iv) enhanced the Nrf2–antioxidant response element transcriptional response in transfected HEK293T cells; and (v) protected organotypic cultures of hippocampal slices subjected to oxygen and glucose deprivation and re-oxygenation from stress by increasing the expression of haem oxygenase-1 and reducing free radical production.

Conclusion and Implications

ITH12674 combines the signalling pathways of the parent compounds to improve its neuroprotective properties. This opens a new line of research for such hybrid compounds to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Glutathione S-transferase (GST) |

| Haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) |

| Papain |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Glutathione (GSH) |

| Melatonin |

| Tin-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP) |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Due to an increased ageing population, neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD) as well as ischaemic stroke are an increasing burden to society because of their cumulative morbidity and mortality. Common features of NDDs are cognitive and/or motor deficits, selective loss of neurons, the appearance of aberrant protein aggregates. In addition, there is abundant evidence of lipid peroxidation, protein nitration and nucleic acid oxidation (Di Carlo et al., 2012).

Oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction are thought to play a key role in the onset and development of NDD (Lin and Beal, 2006). For instance, the brains of AD patients are subjected to high oxidative stress, as demonstrated in post-mortem AD temporal cortex and hippocampus (Schipper et al., 2006), and in astrocytes and neurons (Ramsey et al., 2007). Similar results have been obtained for PD and other NDDs (Dasuri et al., 2013). In normal conditions, cells respond to oxidative stress through an endogenous mechanism regulated mainly by the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2). Nrf2 is a member of the Cap ‘n’ Collar family of transcription factors that bind to the antioxidant response element (ARE) to regulate the antioxidant response (Nguyen et al., 2010). It is sequestered in the cytosol by the Keap1 protein, which targets it for ubiquitination by CUL3–ROC1 ligase and subsequent degradation by the proteasome (Furukawa and Xiong, 2005). In the presence of oxidative stress, Nrf2 is released from Keap1, translocates into the nucleus and binds to the ARE sequences forming a complex with a small Maf protein to induce the ‘phase II antioxidant response’ (Zhang et al., 2013). Phase II genes induced by Nrf2 include, among others, haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and GSH synthetic enzymes (Zhang et al., 2013). Interestingly, despite abundant evidence for the occurrence of oxidative stress in NDDs, the Nrf2–ARE signalling pathway is attenuated or deleted in several neurodegenerative pathological conditions (Ramsey et al., 2007). Therefore, there is increasing evidence supporting the use of the Nrf2–ARE transcriptional pathway as a key target for the treatment of NDDs. For example, in animal models of AD, induction of the Nrf2–ARE transcriptional pathway has been demonstrated to improve spatial learning (Kanninen et al., 2009) and attenuate inflammation (Thimmulappa et al., 2006) and oxidative stress. In PD, several inducers of Nrf2 have been shown to have the ability to protect cells and ameliorate symptoms in vitro (Jakel et al., 2007) and in vivo (Chen et al., 2009). There is also evidence of the therapeutic potential of the Nrf2–ARE pathway in Huntington disease (Calkins et al., 2005; Ellrichmann et al., 2011), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Vargas et al., 2008) and brain ischaemic damage. Sulforaphane, a potent Nrf2 inducer isolated from sprouting broccoli, has been extensively studied in several NDD models. It has been found to have a wide neuroprotective profile (Tarozzi et al., 2013) in numerous in vitro and in vivo oxidative stress models of AD (Kim et al., 2013), PD (Jazwa et al., 2011; Morroni et al., 2013), cerebral ischaemia (Zhao et al., 2006) and inflammation (Innamorato et al., 2008); this effect is thought to be mediated by the induction of the Nrf2–ARE pathway.

Melatonin is a well-known multifunctional molecule that influences the circadian rhythms (Hardeland et al., 2012), the immune response (Mauriz et al., 2013), the cardiovascular (Dominguez-Rodriguez et al., 2012) and digestive systems (Palileo and Kaunitz, 2011). Additionally, over the last decade, it has been extensively investigated because of its benefits in the CNS (Wang, 2009). The neuroprotective profile of melatonin is related, in part, to its potent antioxidant and scavenger effect (Tan et al., 1993; Reiter et al., 2009; Kilic et al., 2012). As a scavenger, melatonin reacts with free radicals to form several metabolites that can also trap free radicals; this is known as the ‘scavenger cascade of melatonin’ (Tan et al., 2007). A single molecule of melatonin is able to trap up to 10 free radicals (Tan et al., 2001, 2007; Rosen et al., 2006). Furthermore, melatonin increases the activity of several antioxidant enzymes (Luchetti et al., 2010). Because of its antioxidant and neuroprotective activities, melatonin has been suggested as a possible treatment for oxidative stress-related disorders such as NDDs (Pandi-Perumal et al., 2013).

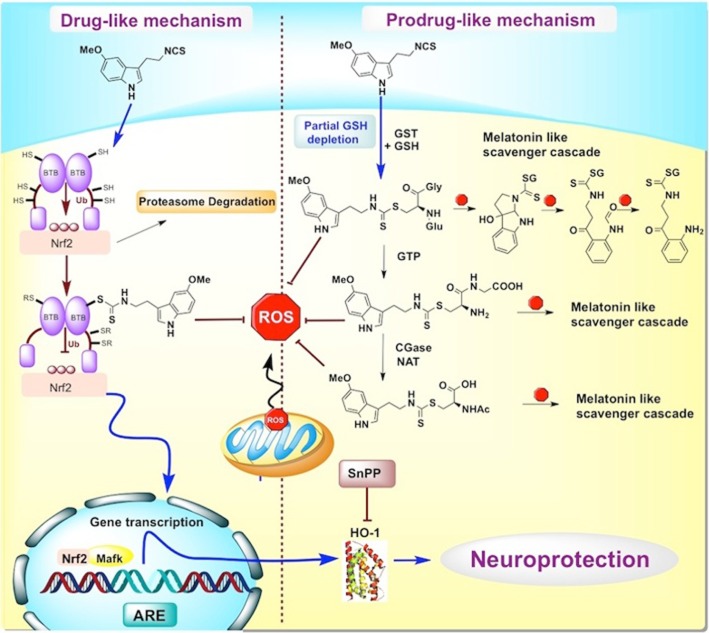

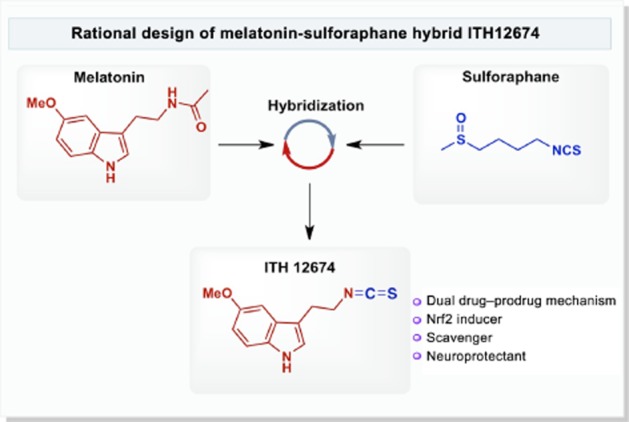

In the light of the pleiotropic profile of melatonin and the interesting neuroprotective results obtained with sulforaphane, we have hypothesized that the combination of these compounds in one molecule could eventually result in complementary, additive neuroprotective effects with a potential therapeutic application for NDDs. Hence, we have generated a melatonin–sulforaphane hybrid, ITH12674 (Figure 1), designed to react with cysteines present in Keap1 to liberate Nrf2, which then acts as a drug and also to be conjugated with GSH inside the cell to generate a potent melatonin-like antioxidant compound, a prodrug of this conjugate. This drug–prodrug mechanism resulted in an improved pharmacological profile with therapeutic potential for the treatment of NDDs.

Figure 1.

Rational design of melatonin–sulforaphane hybrid ITH12674.

Methods

Chemistry

Compound ITH12674 was synthesized in our laboratories using an optimized synthetic protocol. A solution of N,N′-thiocarbonyldiimidazole (0.26 mmol, 46.8 mg) in THF (2 mL) was added to a solution of 2-(5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethanamine (0.26 mmol, 50 mg) in dry tetrahydrofuran (3 mL) at 0°C for 10 min. The resulting solution was allowed to warm-up to room temperature and stirred for 3 h until completion. Thereafter, the solvent was eliminated under reduced pressure and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (hexane : CH2Cl2 0–60%) to yield the product (ITH12674) as a pale yellow oil (54.4 mg, 90% yield); Rf 0.87 (dichloromethane, 100%); 1H NMR and 13C NMR data were in agreement with previously reported findings (Singh et al., 2007); Rf 0.87 (DCM, 100%); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.91 (1H, bs, NH), 7.20 (1H, d, J = 8.6 Hz, H7), 7.01 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H4), 6.91 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H2), 6.81 (1H, dd, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz, H6), 3.81 (1H, s, OCH3), 3.69 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, OCH2CH2NCS ), 3.06 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, OCH2CH2NCS); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δC 154.2, 131.4, 127.3, 123.8, 112.5, 112.2, 110.9, 56.1, 45.7, 26.5; HRMS (ES+) mass calc'd. For C12H12N2SO 232.0670; found [(M + H)+] 233.0740, found [(M + Na)+] 255.0567; Anal. Calcd. For C12H12N2SO: C, 62.04; H, 5.21; N, 12.06, S, 13.80. Found: C, 62.26; H, 5.38; N, 11.88; S, 13.56.

Animal experiments

All experimental procedures were performed following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were previously approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain, according to the European Guidelines for the use and care of animals for research in accordance with the European Union Directive of 22 September 2010 (2010/63/UE) and with Spanish Royal Decree of 1 February 2013 (53/2013). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Isolation and culture of rat cortical neurons

Cortical neuron culture was performed as previously described (Lorrio et al., 2013). Briefly, pregnant rats (Sprague Dawley, SD) were decapitated and 18-day-old embryos were quickly removed. The cortex was dissected under a stereomicroscope in PBS at 4°C. The tissue was digested with 0.5 mg·mL−1 papain and 0.25 mg·mL−1 DNAse dissolved in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS containing 1 mg·mL−1 BSA and 6 mM glucose at 37°C for 20 min. The papain solution was replaced by 5 mL of neurobasal medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were resuspended in 5 mL neurobasal medium and plated at the desired density on plates coated with poly-D-lysine (0.1 mg·mL−1). After 2 h of culture in the presence of FBS, the medium was replaced by fresh serum-free medium containing B27 supplement with antioxidants. Under these conditions, standard cell survival was 4 weeks; experiments were performed after 7–10 days in culture.

Preparation of organotypic hippocampal slice cultures (OHCs)

Cultures were prepared according to the methods described by Stoppini et al. (1991) with some modifications. Briefly, 300 μM thick hippocampal slices were prepared from SD rats (8–10 days old) using a Mcilwain tissue chopper (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA, USA) and separated in ice-cold HBSS. Four to six slices were placed per Millicell 0.4 μM culture insert and placed on a 6-well culture tray with media where they remained for 7 days. The culture media consisted of 50% MEM, 25% HBSS and 25% heat-inactivated horse serum. The medium was supplemented with 3.7 mg·mL−1 D-glucose, 2 mmol·L−1 L-glutamine and 2% of B27 supplement minus antioxidants and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin. OHCs were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2, and the medium was changed twice a week.

Cell treatment with compound solutions

Stock solutions were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10−2 M. All solutions were stored in aliquots at −20°C. Once defrosted for a given experiment, the aliquot was discarded. The final concentrations of DMSO used (always <0.1%) did not cause neuronal toxicity.

Neuroprotection experiments

Toxicity elicited by rotenone/oligomycin A or TBH in cortical neurons

Rat cortical neurons were plated at a density of 60 000 cells per well in 96-well plates. The cells were treated with neuroprotective compounds at the desired concentrations for 24 h. Thereafter, the compounds were withdrawn and the toxins added: (i) 30 μM rotenone plus 10 μM oligomycin A or (ii) 30 μM TBH for another 24 h. Toxins were incubated in 10% B27 minus antioxidant medium. At the end of the experiments, cell death was assessed by following the MTT reduction method.

Quantification of cell viability by MTT reduction

MTT was added (5 mg·mL−1 per well) to the cell samples, which were then incubated in the dark at 37°C for 2 h. The formazan produced was dissolved by adding 100 μL of DMSO, resulting in a coloured compound; the optical density of this compound was measured in an elisa reader at 540 nm. All MTT assays were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as a percentage of MTT reduction, with the maximum control capability in each individual experiment taken as 100%.

Oxygen and glucose deprivation in OHCs

The inserts with OHCs were placed into 1 mL of the oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) solution composed of (in mM): NaCl 137.93, KCl 5.36, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1.19, NaHCO3 26, KH2PO4 1.18 and 2-deoxyglucose 11. The OHCs were then placed into an airtight chamber (Billups and Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA, USA) and were exposed to 95% N2/5% CO2 gas flow for 5 min to ensure oxygen deprivation. After that, the chamber was sealed for 15 min at 37°C. Control cultures were maintained for the same time under normoxic atmosphere in a solution with the same composition as that described above (OGD solution) but containing glucose (11 mM) instead of 2-deoxyglucose. After the OGD period, slice cultures were returned to their original culture conditions for 24 h (reoxygenation period).

Quantification of cell death in OHCs by PI and Hoechst 33342 staining

At the end of the experiment, the OHCs were loaded with 1 μg·mL−1 PI and Hoechst 33342 (Hoechst) during the last 30 min of incubation. Mean PI and Hoechst fluorescence in the CA1 region in each slice, after a given treatment, were analysed. Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescence inverted NIKON eclipse T2000-U microscope (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Wavelengths of excitation and emission for PI and Hoechst were 530 or 350 and 580 or 460 nm respectively. Fluorescence was analysed using the Metamorph programme version 7.0 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were normalized with respect to control values that were considered as 1.

Luciferase assays

To monitor the expression of Nrf2–ARE, HEK 293T cells were seeded on 24-well plates (100 000 cells per well), cultured for 16 h and transfected using calcium phosphate. Transient transfections of HEK293T cells were performed with the expression vectors pTK-Renilla and ARE-LUC (a gift from Dr J Alam, Department of Molecular Genetics, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, Baton Rouge, LA, USA). After transfection, cells were treated with ITH12674 at the indicated doses for 16 h. As a control, transfected cells were treated with sulforaphane (0.3 μM) for 16 h. Then, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity with the dual luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Relative light units were measured in a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer (Promega, Madrid, Spain) with dual injectors.

Immunocytochemistry

Cortical neurons were seeded in 6 multiwell plates (50 000 cells per well) on poly-D-Lys-covered slides. Neurons were incubated with treatments for 2 h and then were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde dissolved in PBS for 15 min and washed three times with PBS every 5 min. Later, they were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 min and washed three times with PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibody (anti-Nrf2, H-300, SC-13032, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight. Then, three consecutive washes with PBS were performed before the samples were incubated with secondary antibody (45 min). To visualize the nuclei, cells were counterstained with Hoechst (5 μg·mL−1) during the second wash (Invitrogen, Madrid, Spain). Finally, the slides were covered with coverslips, glycerol-PBS (1:1 v v−1) added and they were viewed with a confocal microscope (TCS SPE, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Intracellular GSH measurement

To quantify free GSH we used monochlorobimane (Kamencic et al., 2000). Cells were incubated with monochlorobimane (100 μM) at a final volume of 50 μL of neurobasal media without B27 for 1 h. Then, cells were washed twice with Krebs–HEPES solution and fluorescence intensity was measured in a Fluostar optima microplate reader (BMG Labtech Offenburg, Germany) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 410 and 485 nm respectively. All measurements were performed in triplicate in five different cell cultures.

In vitro GSH conjugation and LC-IT-MS analysis

Reactions were performed in vitro using a glutathione S-transferase (GST) enzyme. GSH (5 mM, final concentration), ITH12674 (1 mM, final concentration) and 10 U of GST were added to PBS (10 mM, pH 6.5) at a final volume of 500 μL. The reaction was maintained at 37°C for 1 h. As control, non-enzymatic reaction (mixture lacking GST) was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by adding 100 μL of 20% trifluoroacetic acid. Samples were prepared for analysis by adding 400 μL of a 50:50 mixture of MeOH : CH3CN. The reaction mixtures were analysed using an API QSTAR pulsar I LC-MS/MS system (Applied Biosystems, Madrid, Spain) equipped with an electrospray ionization source and connected to a LC system 1100 series (Agilent Technologies, Madrid, Spain). Sample components were separated in a 150 × 2.1 mm BetaBasic-18 C18 column using a linear gradient mobile phase of 80% water with 0.1% formic acid and 20% acetonitrile. The LC-IT-MS was operated in positive ion mode.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

To measure the generation of ROS, we used the molecular probe H2DCFDA (Ha et al., 1997). H2DCF reacts with intracellular ROS to form dichlorofluorescein, a green fluorescent dye. Neurons were seeded in 96-well clear bottom-black plates for 7–8 days. After the treatments, neurons were loaded with 10 μM H2DCFDA for 45 min. Subsequently, neurons were washed twice with Krebs solution and kept for 15 min before the beginning of the experiment. Then, neurons were exposed to the ROS generator (rotenone and oligomycin A combination, rot/olig) for 4 h. Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescence microplate reader (Fluostar optima; BMG Labtech). Wavelengths of excitation and emission were 485 and 520 nm respectively. The fluorescence of control was normalized as 100% and the increase in fluorescence induced by a 4 h exposure to the ROS generator (rot/olig) was expressed as % control cells.

Western blot analysis

Slices of each experimental group were lysed in 100 μL ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 μg·mL−1 leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 1 mM Na3VO4). Proteins (30 μg) from these lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corp.). Membranes were incubated with anti-HO-1 (1:1000) and anti-β-actin (1:50 000). Appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10 000) were used to detect proteins by enhanced chemiluminescence. Protein bands were scanned and density was analysed using the Scion Image analysis software (Scion Corporation, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Control value was considered as 1.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between experimental and control groups were performed by one-way anova followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05. All statistical procedures were carried out using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Chemicals

The fluorescent dyes propidium iodide (PI), Hoechst 33342 and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), neurobasal, FBS, B27 supplement, B27 minus antioxidants (AO), minimal essential medium (MEM), HBSS and heat-inactivated horse serum were from Life Technologies (Madrid, Spain). Anti-HO-1 was purchased from Millipore (Madrid, Spain). Rotenone, oligomycin A, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBH), SULF, anti-β-actin, monochlorobimane, GSH S-transferase (GST), melatonin, MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide), 2-deoxyglucose and poly-D-lysine were from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain). Tin-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP) dichloride was from Tocris (Biogen, Madrid, Spain). pTK-Renilla was from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Results

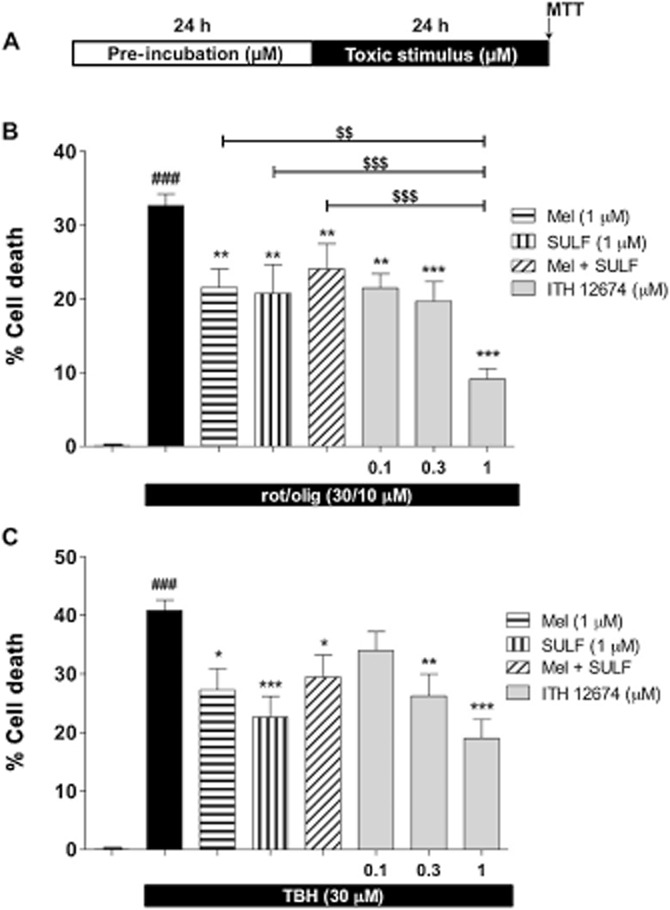

ITH12674 protects primary cortical neurons against oxidative stress

To evaluate the neuroprotective profile of ITH12674 we first used two different in vitro models of oxidative stress, the combination of rot/olig (Egea et al., 2007) and TBH (Kurz et al., 2004). Rotenone and oligomycin A block complexes I and V, respectively, of the mitochondrial electron transport chain generating free radicals. In this study, we selected a pre-incubation protocol in order to evaluate the potential neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 derivative depending on its Nrf2 induction capability. Cortical neurons were pre-incubated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of ITH12674 and reference compounds [melatonin (1 μM) and sulforaphane (1 μM)] before the addition of toxic stimuli. Thereafter, treatments were removed and the correspondent toxic stimuli were added in fresh medium, without any compound and maintained for another 24 h. Neuronal viability was measured by the MTT reduction method (Figure 2A). Exposure of cortical neurons to rot/olig (30/10 μM) for 24 h significantly increased cell death to 33% with respect to untreated control (Figure 2B). Melatonin and sulforaphane significantly increased neuronal viability eliciting 40 and 44% protection, respectively, and their combination resulted in a similar protection of 35%. ITH12674 reduced the toxicity of rot/olig in a concentration-dependent manner, inducing 20% protection at a concentration of 100 nM; at 0.3 μM this protection increased to 41%. The highest neuroprotective effect was reached at 1 μM (72%), which was more potent than reference compounds, either separately or combined.

Figure 2.

ITH12674 exhibits concentration-dependent protection in cortical neurons against neuronal toxicity elicited by oxidative stress. (A) Experimental protocol: cortical neurons were pre-incubated with different treatments at defined concentrations for 24 h. Thereafter, neurons were subjected to toxic stimuli for another 24 h in the absence of the protecting compounds. (B) Cell death induced by the combination of rotenone (30 μM) and oligomycin A (10 μM) (rot/olig) and protection mediated by melatonin (1 μM), sulforaphane (SULF, 1 μM) and increasing concentrations of ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM). (C) Cell death induced by TBH (30 μM) and its reduction induced by the previous compounds at the same concentrations. Data are expressed as cell death calculated as 100 minus % of viability assessed by the MTT technique and data were normalized as % basal. Data are mean ± SEM of triplicates of six independent experiments ###P < 0.001 comparing basal and toxic injured neurons; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 comparing toxic stimulus group in the absence of drugs; $$P < 0.01; $$$P < 0.001 comparing ITH12674 group with reference compounds.

TBH simulates the oxidative stress generated by complexed metals outside the cells (Kurz et al., 2004). We used the same protocol described earlier (see protocol in Figure 2A). Incubation of cortical neurons with TBH for 24 h increased cell death to 40% (Figure 2C). ITH12674 significantly reduced TBH toxicity at concentrations of 0.3 and 1 μM, but not at 0.1 μM. In contrast, melatonin and sulforaphane elicited 33 and 47% protection, respectively. When given in combination, the protection decreased to 29%. In contrast, ITH12674 at 1 μM increased cell viability by 57%, being more potent than melatonin and sulforaphane at the same concentration.

Short-term decrease in GSH levels by ITH12674 due to GST-mediated conjugation with GSH

To evaluate the mechanism of action of ITH12674, we first focused on the GSH content of the treated neurons. GSH is the most important antioxidant inside the cells and its concentration is dependent on the expression of phase II enzyme. Electrophilic compounds decrease the levels of GSH by direct conjugation, which is catalysed by GST. Then, the redox system of the cell detects the GSH depletion, liberates Nrf2 that then translocates to the nucleus inducing the phase II antioxidant response. This mechanism is well documented for sulforaphane which, after conjugating with GSH, accumulates inside the cells (Ye and Zhang, 2001).

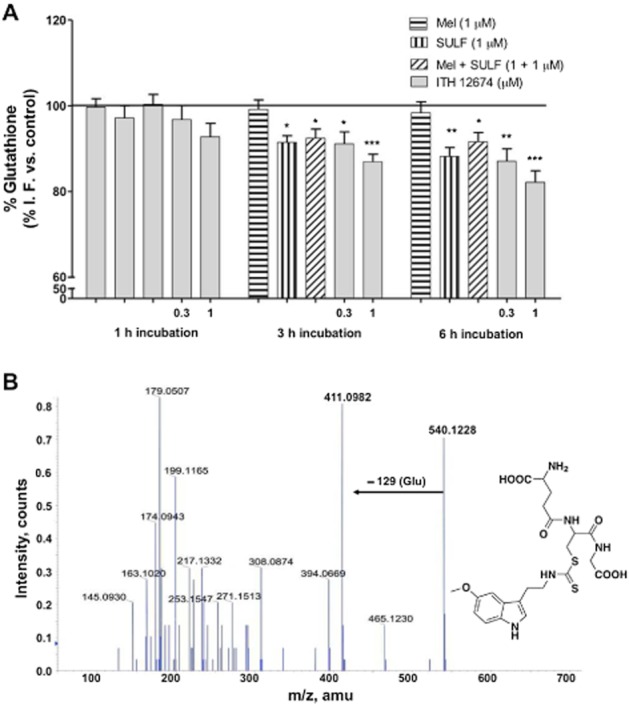

Thus, we were interested in measuring the time course for the changes in levels of GSH in response to, first, GSH depletion, and second, de novo synthesis of GSH due to phase II gene overexpression. Cortical neurons were incubated with increasing concentrations of ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3, 1.0 μM) and reference compounds melatonin or sulforaphane over three periods of time (1, 3 and 6 h). Following pre-incubation, treatments were removed and neurons were loaded with the dye monochlorobimane. As shown in Figure 3A, GSH concentrations after a 1 h pre-incubation with melatonin, sulforaphane or their combination were the same as those in untreated neurons. Incubation with each treatment over a period of 3 h resulted in a decreased GSH concentration in the presence of sulforaphane (8%) and more markedly in the presence of ITH12674, 15% decrease at 1 μM. Larger differences were observed with 6 h pre-incubation periods, where sulforaphane decreased the levels of GSH by 10%. ITH12674 decreased GSH levels in a concentration-dependent fashion showing a 20% decrease at 1 μM.

Figure 3.

ITH12674 decreased the levels of GSH in cortical neurons due to GST-mediated conjugation with GSH up to 6 h after incubation. (A) Cortical neurons were incubated with ITH12674 (0.3 and 1 μM) or reference compounds melatonin (1 μM), sulforaphane (SULF, 1 μM) or their mixture for 1, 3 and 6 h. Thereafter, treatments were removed and neurons were loaded with the fluorescent dye monochlorobimane for 1 h. Then, fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as % of fluorescence compared with vehicle control (DMSO). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicates of five independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with control conditions. (B) In vitro LC-MS/MS data for GST-mediated ITH12648–GSH conjugation, proposed chemical structure of the conjugate m/z 540 and its MS/MS fragmentation spectrum.

To demonstrate the conjugation of ITH12674 with GSH, we performed in vitro experiments in the presence of GST; the formation of the conjugate was analysed using LC-IT-MS. ITH12674 (1 mM) was mixed with reduced GSH (5 mM) in the presence of GST for 1 h at 37°C. The same conditions without GST were used as control reaction (data not shown). The expected molecular ion [M + 1]+ of ITH12674–GSH conjugate (m/z = 540) appears in the peak at 11.4 min (data not shown). The fragmentation pattern of this peak demonstrates its structure (Figure 3B) showing a characteristic peak of glutamate loss (−129) of the conjugate (m/z = 411).

Long-term induction of GSH levels by ITH12674 is due to Nrf2–ARE transcriptional regulation

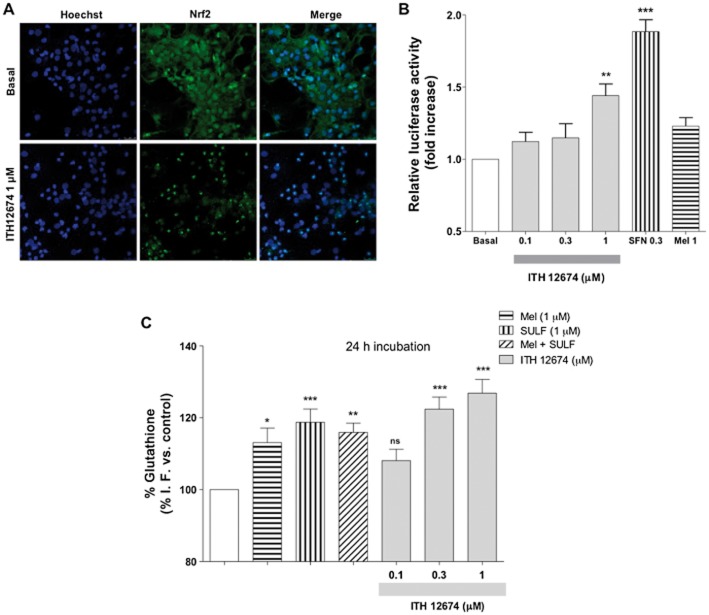

The melatonin–sulforaphane hybrid ITH12674 was designed with the intention of combining the pharmacological properties of melatonin and the Nrf2 inducer abilities of sulforaphane. To confirm the Nrf2 inducer activity of ITH12674, we first studied the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 in the presence of ITH12674. Cortical neurons were treated with the hybrid compound (1 μM) or culture media for 2 h, then neurons were fixed and double stained with anti-Nrf2 and Hoechst. As shown in Figure 4A, in untreated neurons the Nrf2 was predominantly present in the cytosol; however, in the presence of 1 μM ITH12674 Nrf2 was predominantly located in the nucleus. Next, we tested the relative potency of ITH12674 with respect to melatonin and sulforaphane. HEK293T cells were transfected with ARE–LUC, and after overnight recovery, cells were stimulated for 16 h with increasing concentrations of ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM), sulforaphane (0.3 μM) or melatonin (1 μM). ITH12674 increased reporter gene activity at the concentration of 1 μM, showing a 1.4-fold increase with respect to basal conditions (Figure 4B). sulforaphane, used as a control, almost doubled ARE expression at 0.3 μM and melatonin was not able to increase reporter gene activity in this model. As previously stated, de novo synthesis of GSH is regulated by phase II antioxidant genes as rate-limiting GSH synthetic enzymes are regulated by the ARE response. Thus, we measured GSH levels after 24 h. As shown in Figure 4C, a 24 h incubation of neurons with melatonin or sulforaphane increased the concentration of GSH by 17 and 20%, respectively, with respect to untreated controls. ITH12674, 0.3 and 1 μM, also increased the concentration of GSH after 24 h by 22 and 25%, respectively, with respect to control conditions (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

ITH12674 induced Nrf2–ARE transcriptional response by nuclear translocation of Nrf2, measured as increased luciferase activity in HEK293T cells and increased GSH levels after a 24 h pre-incubation period. (A) Cortical neurons were treated with ITH12674 (1 μM) or culture medium (Basal) for 2 h, then they were processed for immunocytochemistry and stained with anti-Nrf2 (green) and Hoechst (blue). (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with the ARE–LUC reporter and Renilla control vectors. After transfection, cells were treated with either ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM), sulforaphane (0.3 μM) or Mel (1 μM) for 16 h and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold induction of luciferase activity compared with vehicle control (DMSO). Data are mean ± SEM of quadruplicates (n = 4), **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with basal conditions. (C) Cortical neurons were incubated with ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM) or reference compounds melatonin (1 μM), sulforaphane (1 μM) or their mixture for 24 h. Thereafter, treatments were removed and neurons were loaded with the fluorescent dye monochlorobimane for 1 h. Then fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are expressed as % of fluorescence compared with vehicle control (DMSO). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicates of five independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with control conditions.

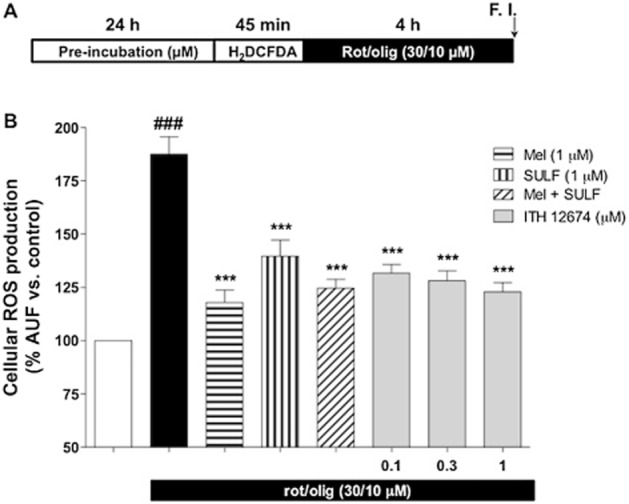

Antioxidant effect of ITH12674 in cortical neurons once conjugated with GSH

To correlate the neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 with its ability to induce Nrf2 and accumulation of the conjugate, we measured the mitochondrial ROS production induced by rot/olig, after 4 h, with the fluorescent dye H2DCFDA. Cortical neurons were treated with increasing concentrations of ITH12674 (0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 μM) or reference compounds for 24 h. Then, treatments were removed by washing and cells were loaded with the fluorescent dye for 45 min. After washing away the fluorescent dye, cells were incubated with rot/olig for 4 h (Figure 5A). Rot/olig incubation increased the production of ROS species by 87.5% with respect to untreated neurons. As shown in Figure 5B, ITH12674 and reference compounds reduced the production of ROS species. ITH12674 reduced ROS production to 31, 28 and 22% at the concentrations of 0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 μM respectively. Melatonin was the most potent, decreasing the production of ROS to only 17% over basal conditions. This reduction was similar to that produced by 1 μM ITH12674 and by the mixture of melatonin and sulforaphane. sulforaphane alone reduced ROS production to 39.7%.

Figure 5.

ITH12674 reduces ROS production in cortical neurons induced by the toxic combination of rot/olig after a 24 h pre-incubation. (A) Cortical neurons were pretreated with increasing concentrations of ITH12674 or reference compounds at 1 μM for 24 h. Then, treatments were removed and neurons were loaded with the fluorescent dye H2DCFDA (45 min). Thereafter, the dye was eliminated and neurons were treated with ROS generator (rot/olig) over a 4 h period and fluorescence intensity was measured. Untreated cells without ROS generator were used as control. (B) Bar diagram of ROS production for basal conditions, ROS generator and treatments. Data are expressed as % of fluorescence compared with vehicle control (DMSO). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicates of five independent experiments, ###P < 0.001 comparing control and rot/olig-treated neurons; ***P < 0.001 compared with rot/olig conditions.

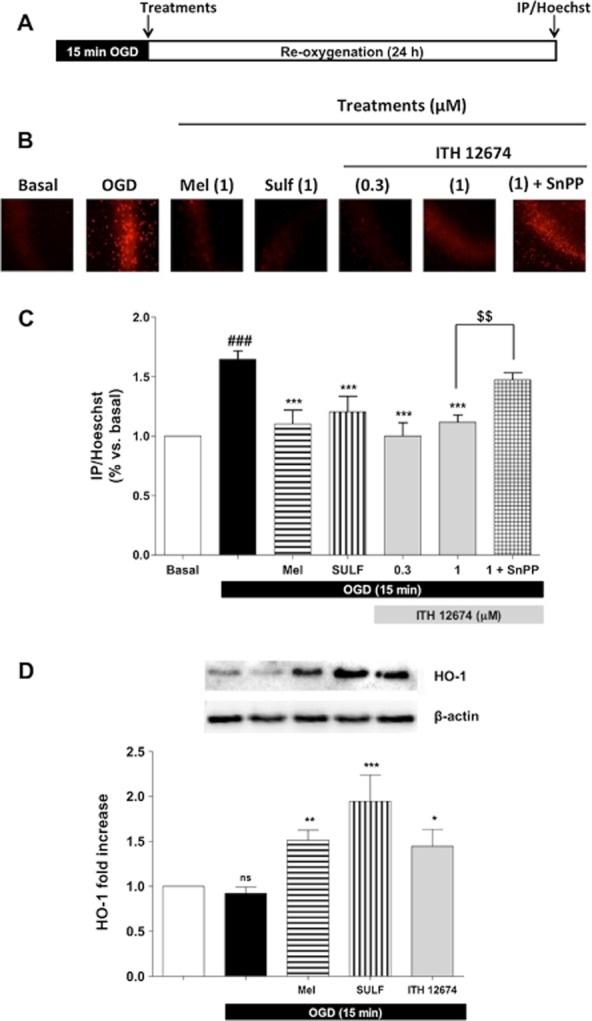

Participation of Nrf2/HO-1 in the neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 against OGD/reox

To further investigate the neuroprotective effect evoked by ITH12674, we selected the oxygen and glucose deprivation plus reoxygenation (OGD/reox) model in OHCs as an in vitro model of brain ischaemia. This model has been demonstrated to reduce hippocampal neuron viability by ROS production and excitotoxicity (Parada et al., 2013). After 15 min of OGD insult, OHCs were incubated with selected concentrations of ITH12674 (0.3 and 1 μM) and reference compounds, melatonin and sulforaphane (1 μM), for the 24 h re-oxygenation period (Figure 6A). OGD/reox increased cell death by 65% (1.65 ± 0.7) compared with control OHCs maintained in normoxia plus glucose conditions throughout the experiment (Figure 6C), as assessed by PI fluorescence in CA1 (Figure 6B). ITH12674 significantly reduced cell death at both concentrations, restoring OHCs to basal conditions at 0.3 μM (1.00 ± 0.13) and similarly at 1 μM (1.12 ± 0.06). ITH12674 was more potent than melatonin; it reduced toxicity to 10% (1.10 ± 0.13) and sulforaphane that reduced toxicity to 20% (1.20 ± 0.15) at the concentration of 0.3 μM where ITH12674 showed maximum protection.

Figure 6.

Post-OGD treatment with ITH12674 elicits neuroprotection in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures and this effect is linked to HO-1 overexpression. (A) Experimental protocol: OHCs were exposed to 15 min of OGD followed by 24 h in control solution (Reox). ITH12674 or reference compounds were present during the 24 h reox period. (B) Microphotographs (original magnification 10×) of the CA1 subfield loaded with PI for each treatment. (C) Bar diagram of cell viability for basal conditions, OGD and treatments measured as the relationship of PI/Hoechst fluorescence in the CA1 subfield. (D) Top part of the figure illustrates the representative bands showing the expression of HO-1 obtained from hippocampal slices subjected to 15 min OGD and 24 h reox. Expression of HO-1 is presented as densitometric quantification using β-actin for normalization (bottom). Data are mean ± SEM of six independent experiments ###P < 0.001 comparing basal and OGD-injured slices; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 comparing (C) OGD group in the absence of treatments (D) with control slices. $$P < 0.01 comparing OGD-injured slices treated with ITH12674 or ITH12674 plus SnPP (3 μM).

As shown before (Figure 4), ITH12674 was able to induce Nrf2 and to increase GSH. To corroborate the participation of phase II enzymes in the neuroprotection mediated by ITH12674, we analysed the participation of the enzyme HO-1, one of the most important enzymes of the phase II antioxidant and anti-inflammatory response (Cuadrado and Rojo, 2008). After 15 min in OGD, OHCs were treated with ITH12674 and SnPP (HO-1 inhibitor, 3 μM); this resulted in a partial reversal of its neuroprotective effect (1.47 ± 0.07) (Figure 6C). To verify the expression of HO-1, at the end of the experiment, OHCs were collected and cell lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE and analysed by immunoblot with anti-HO-1 (Figure 6D). Melatonin (1 μM) significantly increased, by 1.5-fold, the expression of HO-1 with post-OGD treatment. Sulforaphane was the most potent as, at 1 μM, it increased the expression of HO-1 by 1.9-fold. ITH12674, at 1 μM, also increased the expression of HO-1 in a statistically significant manner by 1.4-fold. Thus, ITH12674 exhibited similar potency to induce HO-1 as melatonin at the same concentration, but it was less potent than sulforaphane.

Discussion

This study focuses on the neuroprotective profile of compound ITH12674 as well as on the signalling pathways involved in such protection. ITH12674 is a hybrid of melatonin and sulforaphane designed to combine the broad pharmacological profile of melatonin and the Nrf2 inducer activity of sulforaphane in a single compound. We demonstrated that it has neuroprotective properties and characterized its mechanism of action, which was shown to involve (i) Nrf2 activation; (ii) reduction in ROS production; (iii) modulation of GSH levels; and, finally, (iv) overexpression of phase II enzymes including HO-1, a potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory enzyme.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are increasingly implicated in NDDs (Lin and Beal, 2006), and are thought to be the driving force of ageing. However, due to the participation of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the onset and development of NDDs and stroke, both hallmarks are increasingly used as key targets for the development of novel therapies for these pathologies. In this context, we focused our efforts to develop a new compound that is able to use both pathological hallmarks as targets. Thus, we first considered melatonin due to its neuroprotective profile in several models of oxidative stress related to neurodegeneration (Srinivasan et al., 2011). Melatonin is able to protect from oxidative stress in different models by increasing the levels of Nrf2 protein (Wang et al., 2012), and the subsequent activation of the Nrf2–ARE pathway and overexpression of phase II enzymes like HO-1 (Ding et al., 2014; Parada et al., 2014). Phase II enzyme induction by melatonin has been directly related to the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 rather than to an increase in its levels, but it depends on the model used (Ding et al., 2014). The circulating levels of melatonin in aged patients have been found to be one-half of those of younger controls (Hardeland, 2013). Moreover, the production of melatonin decreases in aged individuals (Bubenik and Konturek, 2011), which suggests that decreased levels of this hormone are primary contributing factor for the development of NDDs (Reiter, 1994; Karasek, 2007).

Sulforaphane has also been demonstrated to reduce oxidative stress and this protective effect is mediated by the expression of phase II genes (Han et al., 2007; Innamorato et al., 2008). Sulforaphane is also able to increase the protein levels of Nrf2 (Fan et al., 2013). Thus, ITH12674 might also increase Nrf2 protein levels. However, the induction of the Nrf2–ARE pathway has been directly related to the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 rather than to its levels in the cytosol. Sulforaphane is able to protect cells against oxidative stress by increasing the expression of phase II antioxidant enzymes (Danilov et al., 2009). Kassahun et al. (1997) described the conjugation of the isothiocyanate moiety of sulforaphane and GSH to induce Nrf2 (Kassahun et al., 1997). In that study, they demonstrated that the sulforaphane–GSH conjugate is metabolized by two peptidases that eliminate the γ-glutamyl (GTP) and the glycyl (C-glycyl peptidase) residues to generate a sulforaphane–Cys derivative. Finally, N-acetyl-transferase acetylates the sulforaphane–Cys derivative (Kassahun et al., 1997). Furthermore, Zhang (2000) demonstrated that isothiocyanates are accumulated in several cell lines upon exposure to these compounds, causing the activation of phase II enzymes by the generation of GSH conjugates. It was also demonstrated that the accumulation of isothiocyanates and induction of Nrf2 were dependent on GSH (Ye and Zhang, 2001).

As described in the Introduction, the inclusion of the isothiocyanate moiety in ITH12674 was designed to implement a ‘drug–prodrug’ mechanism for the new molecule. The isothiocyanate moiety could react with key cysteine residues present in Keap1 to release Nrf2 (Figure 7). On the other hand, the GST enzyme catalyses its conjugation with GSH to generate an ITH12674–GSH conjugate (Figure 3B) that might be a potent-free radical scavenger (prodrug mechanism), showing a similar scavenger cascade as described for melatonin (Figure 7) (Tan et al., 2007). The reaction of ITH12674 with GSH generates the conjugated compound with the dithiocarbamate functionality (Figure 7), which mimics the N-acetyl functionality present in melatonin. When the ITH12674–GSH conjugate is generated, it is accumulated inside the cell and it should be able to trap free radicals (Figure 7). This scavenger effect has been demonstrated for the dithiocarbamate analogue of melatonin (Pedras and Okanga, 1998). When this analogue was subjected to oxidative conditions, it was readily oxidized to the tricyclic analogue of cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin (Pedras and Okanga, 1998). Therefore, the ITH12674–GSH conjugate might generate several intermediates able to react again with free radicals, as does cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin, AFMK, AMK, AFM and melatonin (Tan et al., 2007).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed ‘drug–prodrug’ mechanism of action of compound ITH12674.

In support of this hypothesis (Figure 7), we demonstrated the improved neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 with respect to melatonin and sulforaphane. ITH12674 induced Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus at 1 μM (Figure 4A), and it was able to increase reporter gene activity at that concentration, being a better inducer than melatonin in this model (Figure 4B). However, sulforaphane is a better Nrf2 inducer than ITH12674 (Figure 4B), although sulforaphane and melatonin were less potent than ITH12674 at mediating neuroprotection against oxidative stress generated by rot/olig (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained with the TBH model of oxidative stress (Figure 2C). In line with these results, ITH12674 reduced the production of intracellular ROS in a concentration-dependent manner to a larger extent than sulforaphane (Figure 3B), and this reduction might be mediated by the accumulation of ITH12674 inside the neurons as a GSH conjugate. This hypothesis explains the different protection evoked by ITH12674 against the rot/olig combination and TBH. The rot/olig combination generates free radicals inside the cell, and, therefore, the ITH12674–GSH conjugate would be in place to trap these radicals. We also demonstrated a decrease in the GSH content over a time period of 24 h (Figures 3A and 4C). For the first 6 h, the GSH content was partially depleted by the incubation with sulforaphane or ITH12674, but not with melatonin. Finally, the GSH content was increased after a 24 h pre-incubation period with ITH12674 in accordance with the results obtained by Zhang et al. and others (Gao et al., 2001; Ye and Zhang, 2001).

There is compelling evidence to support the view that oxidative stress is enhanced after cerebral ischaemia and reperfusion, which in turn induces lipid peroxidation, protein and DNA oxidation, calcium overload, activation of intracellular signalling pathways, excitotoxicity and inflammation (Soane et al., 2007). Taking into account the neuroprotective profile of melatonin and sulforaphane against oxidative damage in in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischaemia via induction of Nrf2 (Reiter et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2006; Soane et al., 2010; Hall, 2011), we also studied the neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 in an in vitro model of brain ischaemia to elucidate the mechanism of action of this compound, that is, the free radical scavenger generated (prodrug mechanism, Figure 3B) and activation of Nrf2–ARE and phase II antioxidant enzymes (Figure 4A and B). Neuronal death was significantly reduced in OHC cultures treated with ITH12674 post-OGD (incubated during the 24 h reox period). Interestingly, ITH12674 evoked a slightly better neuroprotective effect than melatonin and sulforaphane at both concentrations tested. The protective effect of melatonin and sulforaphane in these models is, at least in part, associated with the expression of HO-1 (Parada et al., 2014). Compound ITH12674 increased the expression of this antioxidant and anti-inflammatory enzyme in the post-OGD incubation protocol (Figure 6). Furthermore, the neuroprotective effect of ITH12674 against OGD/reox depends, partially, on the expression of HO-1 as co-incubation of ITH12674 with the HO-1 inhibitor, SnPP, reversed by 35% the neuroprotective effect of this hybrid. The partial reversal of the neuroprotective effect upon co-incubation with SnPP is also in line with the hypothesis that ITH12674 generates a GSH conjugate with antioxidant properties. Hence, the protection evoked by ITH12674 might be related, first, to the overexpression of HO-1 (Figure 6D) and, second, to the scavenger effect of the conjugate accumulated inside the neurons.

In conclusion, we have designed a melatonin–sulforaphane hybrid that possesses a dual drug–prodrug mechanism of action (Figure 7), and has an improved neuroprotective profile compared to melatonin and sulforaphane in three different models of oxidative stress. Its neuroprotective action is dependent on its conjugation with GSH, the induction of Nrf2 and the overexpression of phase II enzymes as demonstrated by the overexpression of HO-1, a potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory enzyme.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from IS Carlos III, Programa Miguel Servet (CP11/00165) and European Commission, Marie Curie Actions FP7 (FP7-People-2012-CIG-322156) to R. L. and Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad ref. SAF2012-32223 and Spanish Ministry of Health (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) RETICS-RD06/0026 to M. G. L. I. B. thanks MECD for FPU fellowship (AP2010-1219) and E. N. thanks UAM for FPI fellowship. R. L. thanks IS Carlos III for research contract under Miguel Servet Program. We would also like to thank ‘Fundación Teófilo Hernando’ for its continued support.

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ARE

antioxidant response element

- GST

GSH S-transferase

- H2DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- HO-1

haem oxygenase-1

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide

- NDDs

neurodegenerative diseases

- Nrf2

nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- OGD/reox

oxygen and glucose deprivation plus re-oxygenation

- OHCs

organotypic hippocampal cultures

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PI

propidium iodide

- Rot/olig

rotenone and oligomycin A combination

- SnPP

tin-protoporphyrin IX

- SULF

sulforaphane

- TBH

tert-butyl hydroperoxide

Author contributions

J. E. contributed to data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. I. B. and E. N. contributed to data acquisition and data analysis/interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. E. P. and P. R. contributed to data acquisition and data analysis/interpretation. A. C., M. G. L. and A. G. G. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. R. L. contributed to concept/design, acquisition of data, data analysis/interpretation drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubenik GA, Konturek SJ. Melatonin and aging: prospects for human treatment. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Johnson DA, Chan K, Kan YW, Johnson JA. Protection from mitochondrial complex II inhibition in vitro and in vivo by Nrf2-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:244–249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408487101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PC, Vargas MR, Pani AK, Smeyne RJ, Johnson DA, Kan YW, et al. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: critical role for the astrocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Rojo AI. Heme oxygenase-1 as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases and brain infections. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:429–442. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilov CA, Chandrasekaran K, Racz J, Soane L, Zielke C, Fiskum G. Sulforaphane protects astrocytes against oxidative stress and delayed death caused by oxygen and glucose deprivation. Glia. 2009;57:645–656. doi: 10.1002/glia.20793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasuri K, Zhang L, Keller JN. Oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and the balance of protein degradation and protein synthesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:170–185. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo M, Giacomazza D, Picone P, Nuzzo D, San Biagio PL. Are oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction the key players in the neurodegenerative diseases? Free Radic Res. 2012;46:1327–1338. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.714466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding K, Wang H, Xu J, Li T, Zhang L, Ding Y, et al. Melatonin stimulates antioxidant enzymes and reduces oxidative stress in experimental traumatic brain injury: the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway as a potential mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Arroyo-Ucar E, Reiter RJ. Decreased level of melatonin in serum predicts left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction. J Pineal Res. 2012;53:319–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea J, Rosa AO, Cuadrado A, Garcia AG, Lopez MG. Nicotinic receptor activation by epibatidine induces heme oxygenase-1 and protects chromaffin cells against oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1842–1852. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellrichmann G, Petrasch-Parwez E, Lee DH, Reick C, Arning L, Saft C, et al. Efficacy of fumaric acid esters in the R6/2 and YAC128 models of Huntington's disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Staitieh BS, Jensen JS, Mould KJ, Greenberg JA, Joshi PC, et al. Activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response element restores barrier function in the alveolar epithelium of HIV-1 transgenic rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L267–L277. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa M, Xiong Y. BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:162–171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.162-171.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Powerful and prolonged protection of human retinal pigment epithelial cells, keratinocytes, and mouse leukemia cells against oxidative damage: the indirect antioxidant effects of sulforaphane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15221–15226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261572998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HC, Woster PM, Yager JD, Casero RA., Jr The role of polyamine catabolism in polyamine analogue-induced programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11557–11562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED. Antioxidant therapies for acute spinal cord injury. Neurother. 2011;8:152–167. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Lee YJ, Lee SY, Kim EM, Moon Y, Kim HW, et al. Protective effect of sulforaphane against dopaminergic cell death. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:249–256. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R. Melatonin and the theories of aging: a critical appraisal of melatonin's role in antiaging mechanisms. J Pineal Res. 2013;55:325–356. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R, Madrid JA, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin, the circadian multioscillator system and health: the need for detailed analyses of peripheral melatonin signaling. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:139–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorato NG, Rojo AI, Garcia-Yague AJ, Yamamoto M, de Ceballos ML, Cuadrado A. The transcription factor Nrf2 is a therapeutic target against brain inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;181:680–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakel RJ, Townsend JA, Kraft AD, Johnson JA. Nrf2-mediated protection against 6-hydroxydopamine. Brain Res. 2007;1144:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwa A, Rojo AI, Innamorato NG, Hesse M, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Cuadrado A. Pharmacological targeting of the transcription factor Nrf2 at the basal ganglia provides disease modifying therapy for experimental Parkinsonism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2347–2360. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamencic H, Lyon A, Paterson PG, Juurlink BH. Monochlorobimane fluorometric method to measure tissue glutathione. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:35–37. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanninen K, Heikkinen R, Malm T, Rolova T, Kuhmonen S, Leinonen H, et al. Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing Nrf2 improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16505–16510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908397106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek M. Does melatonin play a role in aging processes? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58(Suppl. 6):105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassahun K, Davis M, Hu P, Martin B, Baillie T. Biotransformation of the naturally occurring isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat: identification of phase I metabolites and glutathione conjugates. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1228–1233. doi: 10.1021/tx970080t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic U, Yilmaz B, Ugur M, Yuksel A, Reiter RJ, Hermann DM, et al. Evidence that membrane-bound G protein-coupled melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 are not involved in the neuroprotective effects of melatonin in focal cerebral ischemia. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HV, Kim HY, Ehrlich HY, Choi SY, Kim DJ, Kim Y. Amelioration of Alzheimer's disease by neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane in animal model. Amyloid. 2013;20:7–12. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.751367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz DJ, Decary S, Hong Y, Trivier E, Akhmedov A, Erusalimsky JD. Chronic oxidative stress compromises telomere integrity and accelerates the onset of senescence in human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 11):2417–2426. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorrio S, Gomez-Rangel V, Negredo P, Egea J, Leon R, Romero A, et al. Novel multitarget ligand ITH33/IQM9.21 provides neuroprotection in in vitro and in vivo models related to brain ischemia. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti F, Canonico B, Betti M, Arcangeletti M, Pilolli F, Piroddi M, et al. Melatonin signaling and cell protection function. FASEB J. 2010;24:3603–3624. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriz JL, Collado PS, Veneroso C, Reiter RJ, Gonzalez-Gallego J. A review of the molecular aspects of melatonin's anti-inflammatory actions: recent insights and new perspectives. J Pineal Res. 2013;54:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morroni F, Tarozzi A, Sita G, Bolondi C, Zolezzi Moraga JM, Cantelli-Forti G, et al. Neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 2013;36:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen CT, Nguyen JT, Rutledge S, Zhang J, Wang C, Walker GC. Detection of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell surface markers using surface enhanced Raman scattering gold nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2010;292:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palileo C, Kaunitz JD. Gastrointestinal defense mechanisms. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:543–548. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834b3fcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandi-Perumal SR, BaHammam AS, Brown GM, Spence DW, Bharti VK, Kaur C, et al. Melatonin antioxidative defense: therapeutical implications for aging and neurodegenerative processes. Neurotox Res. 2013;23:267–300. doi: 10.1007/s12640-012-9337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada E, Egea J, Buendia I, Negredo P, Cunha AC, Cardoso S, et al. The microglial alpha7-acetylcholine nicotinic receptor is a key element in promoting neuroprotection by inducing heme oxygenase-1 via nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1135–1148. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada E, Buendia I, Leon R, Negredo P, Romero A, Cuadrado A, et al. Neuroprotective effect of melatonin against ischemia is partially mediated by alpha-7 nicotinic receptor modulation and HO-1 overexpression. J Pineal Res. 2014;56:204–212. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedras MS, Okanga FI. Probing the phytopathogenic blackleg fungus with a phytoalexin homolog. J Org Chem. 1998;63:416–417. doi: 10.1021/jo971702i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey CP, Glass CA, Montgomery MB, Lindl KA, Ritson GP, Chia LA, et al. Expression of Nrf2 in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:75–85. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31802d6da9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ. Pineal function during aging: attenuation of the melatonin rhythm and its neurobiological consequences. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1994;54(Suppl):31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Leon J, Kilic U, Kilic E. When melatonin gets on your nerves: its beneficial actions in experimental models of stroke. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:104–117. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ, Paredes SD, Manchester LC, Tan DX. Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: a newly-discovered genre for melatonin. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44:175–200. doi: 10.1080/10409230903044914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J, Than NN, Koch D, Poeggeler B, Laatsch H, Hardeland R. Interactions of melatonin and its metabolites with the ABTS cation radical: extension of the radical scavenger cascade and formation of a novel class of oxidation products, C2-substituted 3-indolinones. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:374–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipper HM, Bennett DA, Liberman A, Bienias JL, Schneider JA, Kelly J, et al. Glial heme oxygenase-1 expression in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Lange TS, Kim K, Zou Y, Lieb C, Sholler GL, et al. Effect of indole ethyl isothiocyanates on proliferation, apoptosis, and MAPK signaling in neuroblastoma cell lines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:5846–5852. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soane L, Kahraman S, Kristian T, Fiskum G. Mechanisms of impaired mitochondrial energy metabolism in acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3407–3415. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soane L, Li Dai W, Fiskum G, Bambrick LL. Sulforaphane protects immature hippocampal neurons against death caused by exposure to hemin or to oxygen and glucose deprivation. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1355–1363. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Pandi-Perumal SR, Brown GM, Cardinali DP. Melatonin in mitochondrial dysfunction and related disorders. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:326320. doi: 10.4061/2011/326320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D, Chen L, Poeggeler B, Manchester L, Reiter RJ. Melatonin: a potent, endogenous hydroxyl radical scavenger. Endocr J. 1993;1:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Burkhardt S, Sainz RM, Mayo JC, Kohen R, et al. N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine, a biogenic amine and melatonin metabolite, functions as a potent antioxidant. FASEB J. 2001;15:2294–2296. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0309fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, Flores LJ, Reiter RJ. One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;42:28–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarozzi A, Angeloni C, Malaguti M, Morroni F, Hrelia S, Hrelia P. Sulforaphane as a potential protective phytochemical against neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:415078. doi: 10.1155/2013/415078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmulappa RK, Scollick C, Traore K, Yates M, Trush MA, Liby KT, et al. Nrf2-dependent protection from LPS induced inflammatory response and mortality by CDDO-Imidazolide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas MR, Johnson DA, Sirkis DW, Messing A, Johnson JA. Nrf2 activation in astrocytes protects against neurodegeneration in mouse models of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13574–13581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4099-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. The antiapoptotic activity of melatonin in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15:345–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ma C, Meng CJ, Zhu GQ, Sun XB, Huo L, et al. Melatonin activates the Nrf2-ARE pathway when it protects against early brain injury in a subarachnoid hemorrhage model. J Pineal Res. 2012;53:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Zhang Y. Total intracellular accumulation levels of dietary isothiocyanates determine their activity in elevation of cellular glutathione and induction of Phase 2 detoxification enzymes. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1987–1992. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, An C, Gao Y, Leak RK, Chen J, Zhang F. Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;100:30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Role of glutathione in the accumulation of anticarcinogenic isothiocyanates and their glutathione conjugates by murine hepatoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Kobori N, Aronowski J, Dash PK. Sulforaphane reduces infarct volume following focal cerebral ischemia in rodents. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]