Abstract

The head direction (HD) system functions as a compass with member neurons robustly increasing their firing rates when the animal’s head points in a specific direction. HD neurons may be driven by peripheral sensors or, as computational models postulate, internally-generated (‘attractor’) mechanisms. We addressed the contributions of stimulus-driven and internally-generated activity by recording ensembles of HD neurons in the antero-dorsal thalamic nucleus and the postsubiculum of mice by comparing their activity in various brain states. The temporal correlation structure of HD neurons is preserved during sleep, characterized by a 60°-wide correlated neuronal firing (‘activity packet’), both within as well as across these two brain structures. During REM, the spontaneous drift of the activity packet was similar to that observed during waking and accelerated tenfold during slow wave sleep. These findings demonstrate that peripheral inputs impinge upon an internally-organized network, which provides amplification and enhanced precision of the head-direction signal.

Introduction

The relationship between stimulus-driven and internally generated activity is a recurring topic in neuroscience. Yet, how feed-forward sensory signals in subcortical, thalamic and cortical networks interact with internally organized (self-generated or ‘spontaneous’) activity is not well-understood, due largely to the high dimensionality of sensory signal attributes1–4. In contrast, the one-dimensional head-direction (HD) sense offers an opportunity to explore such interactions experimentally. HD neurons fire robustly when the animal’s head points in a specific direction5–8. The HD system encompasses multiple, serially-connected brain networks, including the brainstem, mammillary bodies, anterodorsal thalamic nucleus (ADn), post-subiculum (PoS) and entorhinal cortex6–13. Neurons in the PoS provide feedback projections to neurons in the ADn and mammillary bodies7.

Similar to other sensory systems that pass through the thalamus, the HD sense has been tacitly assumed to be largely controlled by peripheral inputs, mainly the vestibular and ancillary afferents7,8, since firing rates of HD cells are affected both by head direction and the angular velocity of head rotation in the exploring rodent9,14. Visual inputs can also influence the HD signal6,9,10 via reciprocal connections of the PoS with visual areas7,8 but visual inputs are not sufficient to drive HD cells in the PoS after lesioning the ADn14. The HD network is a key part of the brain’s navigational system and HD information is believed to be critical for the emergence of grid cells in the entorhinal cortex12,13,15–17.

Computational models have assumed that HD cells with similar preferred directions fire together and the temporally correlated group of HD neurons (called ‘activity packet’) moves on a virtual ring as the animal turns its head (Movie 1). While members of the activity packet rotate on the ring, neighboring neurons are suppressed by lateral inhibition18–23. Experimental demonstration of the existence of internally organized neuronal populations endowed with such properties, often referred to as ‘attractor networks’ 22,24–26, requires monitoring populations of HD neurons simultaneously and demonstrating that the activity packet remains temporally organized even in the absence of vestibular and other peripheral signals. We therefore reasoned that the postulated attractor dynamic can be revealed by comparing the population activity of HD cells during sleep and in the waking brain27,28.

Results

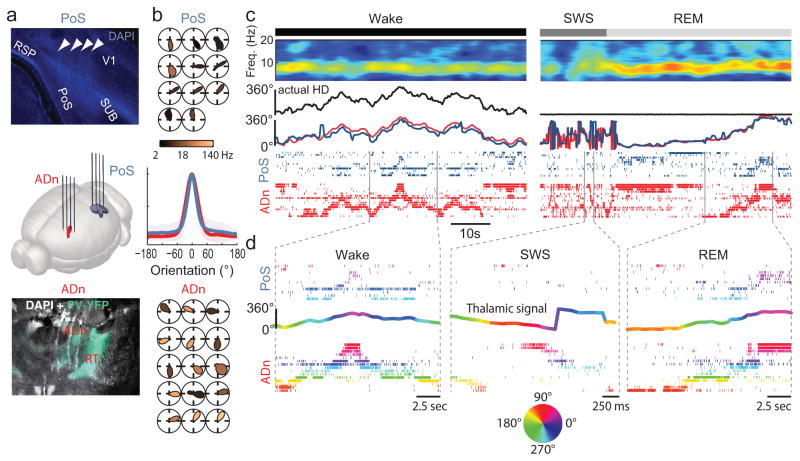

Ensembles of HD neurons from ADn (8.4 ± 5.1 s.d. units per session) and PoS (5 ± 2.8 s.d.) were recorded by multi-site silicon probes (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1) in 7 mice foraging for food in an open environment (42 sessions) and in their home cages during sleep (Supplementary Table 1). In 3 mice (21 sessions) ADn and PoS recordings were performed simultaneously. HD cell ensembles covered the full span of head-directions (Fig. 1b–d). ADn and HD cells were characterized by a uniform bell-shaped tuning curve (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 2a). ADn neurons exhibited peak rates almost three times higher than PoS cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b; p < 10–10, Mann-Whitney U-test, n = 242 ADn and n = 111 PoS HD cells) and conveyed 30% more head-direction information than PoS cells (1.44 bit per spike vs. 1.11 bit per spike; see Methods; Supplementary Fig. 2c; p < 10–6, Mann-Whitney U-test), firing more consistently with the head-direction.

Figure 1. Persistence of information content during wake and sleep in the thalamo-cortical HD circuit.

a: Dual site recording of cell ensembles in the Antero-Dorsal nucleus of the thalamus (ADn) and the post-subiculum (PoS). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI) staining of a coronal section through the PoS (top; arrowheads indicate tracks) and ADn (bottom; DAPI combined with parvalbumin yellow fluorescent protein, PV-YFP). RT, reticular nucleus. b: Tuning curves of simultaneously recorded HD cells in the ADn and the PoS. Polar plots indicate average firing rates as a function of the animals’ HD. Colors code for peak firing rate. Middle panel displays average tuning curves (± s.d.) in Cartesian coordinates. c: Activity of HD cell ensembles during wake, SWS and REM sleep. Top: PoS LFP spectrograms; middle: actual (dashed line) and reconstructed HD signal using Bayesian decoding of ADn (red) or PoS (blue) cells; bottom: raster plots of PoS (blue) and ADn (red) cell spike times. Cells were ordered according to their preferred HD during waking. d: Magnified samples from c. Raster plots of neurons are colored according to their preferred HD during waking. Curves show the reconstructed HD signal from ADn HD cells. Circular y-values are shifted for the sake of visibility but color indicates true decoded HD information.

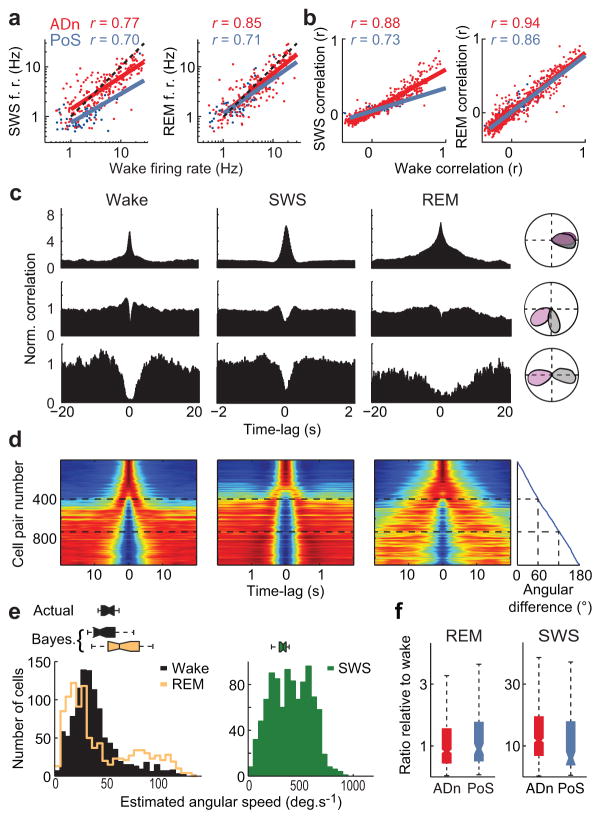

Under the hypothesis of an internally-organized HD system, one expects that the temporal relationship of HD cells should persist in different brain states. To this end, neuronal ensembles were monitored during sleep sessions (5 hours ±1 s.d.), before and/or after active exploration in the open field. Sleep stages were classified as Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS) or Rapid Eye Movement Sleep (REM) based on the animal’s movement and time-resolved spectra of the local field potential recorded from the hippocampus or the PoS (Fig. 1c, see Methods). During sleep, individual neurons formed robustly similar sequential patterns as in the waking state. Using a Bayesian-based decoding of the HD signal from the population of HD cells (see Methods) and the animal’s actual head orientation (Fig. 1c), we could infer a ‘virtual gaze’ — i.e., which direction the mouse was ‘looking’ — during sleep (Fig. 1c,d; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Movie 1). Quantitative brain state comparisons of firing patterns revealed three important features of the ongoing network dynamics. First, the firing rates of HD neurons remained strongly correlated across brain states (Fig. 2a). Second, the pairwise correlations between HD neuron pairs both within and across structures were robustly similar across states (Fig. 2b), indicating the preservation of a coherent representation. Third, the rate of change of the virtual gaze differed between brain states. The angular velocity of the internal HD signal, either estimated by a Bayesian decoder or from the temporal profile of pairwise cross-correlograms (Fig. 2c–e, see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4), was approximately tenfold faster during SWS than during waking (Fig. 2e,f), similar to the temporal “compression” of unit correlations observed in the hippocampus29–31 and neocortex32,33. Angular velocity of the internal HD signal was similar during waking and REM (Fig. 2e,f).

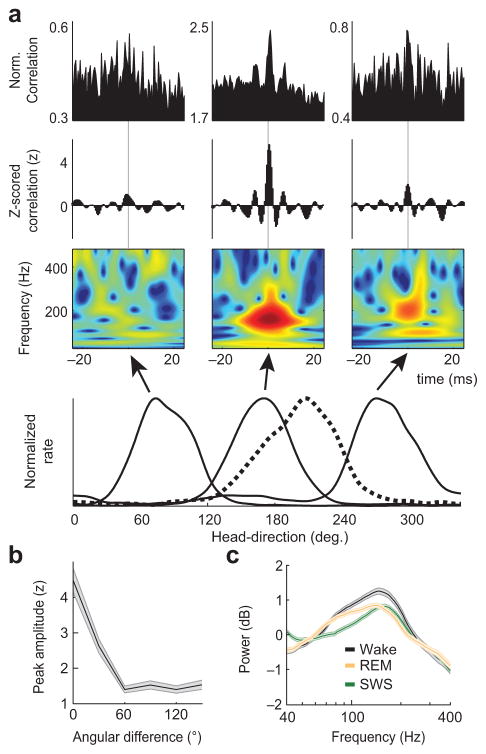

Figure 2. Brain-state dependent dynamics of the HD signal.

a: Firing rates during SWS (left) and REM (right) plotted against waking firing rates for ADn cells (red, n = 215) and PoS cells (blue, n = 62). Insets: Pearson correlation r values. b: Same as a for pairwise correlations (ADn pairs, n = 970; PoS pairs, n = 92). c: Examples of cross-correlations for three HD cell pairs during waking, SWS and REM. Normalized histograms with 1 representing chance. Polar plots display HD fields of the pairs. d: Same as a for all ADn HD cell pairs, sorted by the magnitude of difference between waking preferred directions (shown in right most panel). Each cross-correlogram was normalized between their minimum (dark blue) and maximum (dark red) values. Cell identity order is the same in each panel. e: Left: histogram of average angular velocity estimated from individual cross-correlograms during wake (black) and REM (yellow). Higher angular speed results in more “compressed” cross-correlograms. Their temporal profiles were thus used to quantify the average drifting speed (see Methods). Top: distribution of actual or Bayesian estimates of HD angular speed. Right: same for SWS. f: Distribution of ratios between sleep and wake-estimated angular velocities for ADN-ADN and PoS-PoS HD cell pairs. Boxplot in e and f show median and quartiles.

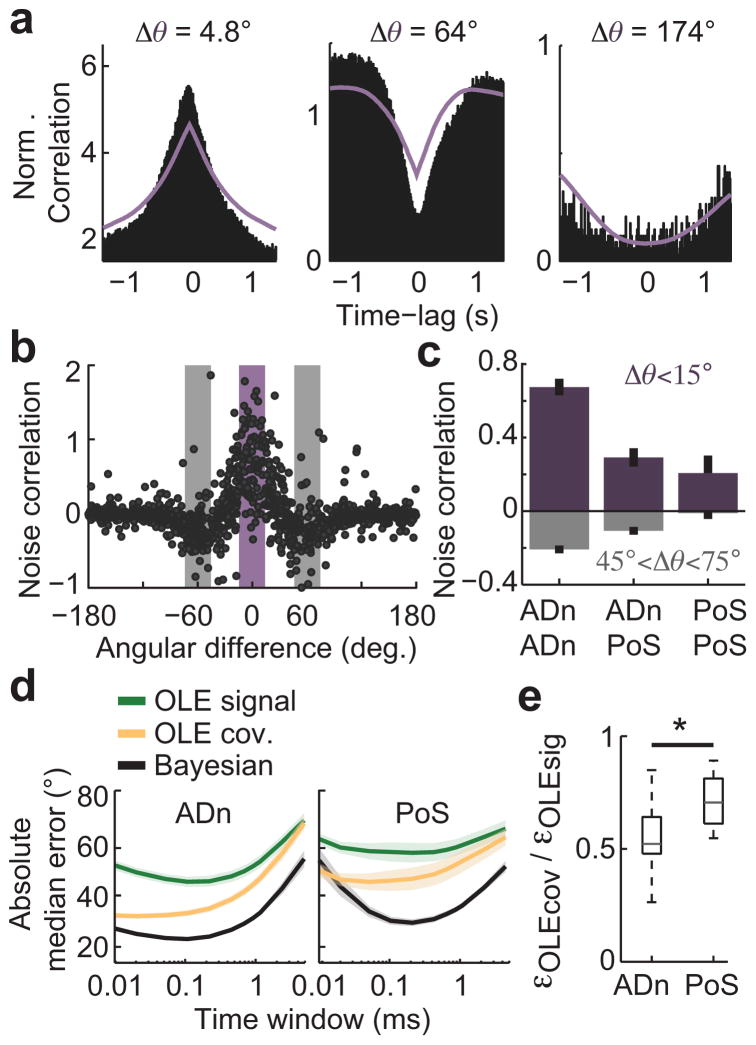

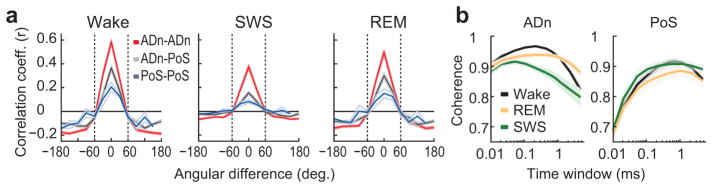

Models of attractor networks suggest that only a subset of cells fire at any given time, referred to as the activity packet and the subset shifts at a predictable velocity8,12,18,19,23,25,26. The distribution of the magnitude of temporal correlations between discharge activities of HD cell pairs at time zero revealed a bell-shaped packet. Pairs of neurons with <60° offset showed positive correlations, pairs with >60° offset showed negative correlations, and pairs with approximately 60° offset were uncorrelated (Fig. 3a). The relationship between the 0-lag correlation and the preferred angular direction was preserved across brain states for cell pairs recorded within a structure (ADn-ADn; PoS-PoS) and between structures (ADn-PoS) (Fig. 3a; p < 10–6 for all brain states and conditions, Pearson’s test, n = 907 ADn-ADn pairs, n = 512 ADn-PoS pairs, n = 92 PoS-PoS pairs). HD signal was more strongly preserved in the ADn than in the PoS as shown by the stronger pairwise correlations in any brain state (p < 10–5, Mann-Whitney U-test for all pairs closer than 60° in all brain states, n = 345 ADn-ADn pairs; n = 55 PoS-PoS pairs), and this difference was independent of firing rate differences between the two structures (Supplementary Fig. 5). The actual activity packets, both in the ADn and the PoS, and across brain states, were highly similar to the predictions given by the signal decoded from a Bayesian estimator (Fig. 3b) in waking, REM and SWS, thus demonstrating the self-consistency of HD representations34. Hence, at any time, the activity packet corresponded to a bounded probabilistic representation of the head direction (Supplementary Movie 1).

Figure 3. Width and coherence of the correlated population activity packet.

a: Pearson’s correlation coefficients of binned spike trains as a function of HD preferred direction offset for ADn-ADn (red), ADn-PoS (gray) and PoS-PoS (blue) cell pairs (300 ms bins during wake and REM, 50 ms bins during SWS). Note 0 correlation at ±60° (dashed lines). b: Ensemble coherence of the activity packet (see Methods) in the ADn (left) and the PoS (right) as a function of the smoothing time window. Activity packets were computed as the sum of tuning curves weighted by instantaneous firing rates and were compared to the expected activity packets at the HD reconstructed with a Bayesian decoder. The coherence was defined as the probability that the two packets were similar (as compared to a bootstrap distribution).

In the waking animal, HD cell dynamic can be explained by inputs arriving from the peripheral sensors7,8. Under this hypothesis, HD neurons in ADn and PoS ‘inherit’ their directional information from upstream neurons and respond independently of each other. However, correlations expected from independent rate-coded neurons could not fully account for the observed pairwise correlations of HD cells (Fig. 4a). ‘Noise’ correlations35 were observed for neuron pairs with overlapping fields (0±15°), with a marked negative signal correlation at 60±15° offset (Fig. 4b,c) and the expected correlations became similar to the observed ones only for pairs with larger angular differences. These signal correlations were stronger for ADn than PoS neurons (p < 10–9, Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance; ADn-ADn pairs: n = 96 and 200, for 0° and 60° signal correlation values respectively; ADn-PoS pairs: n = 77 and 157; PoS-PoS pairs: n = 29 and 57). Importantly, noise correlations could further improve the decoding of the HD signal. Optimal linear estimates (OLE, see Methods) of the head-direction were enhanced when using spike train covariances (i.e., including noise correlation) instead of the tuning curve covariances (i.e., signal correlation only). Estimate of HD based solely on the actual covariance of the spike trains almost reached the performance of a non-linear Bayesian decoder (Fig. 4d). In the ADn, where noise correlations were highest for overlapping HD cells, the covariance-based OLE was approximately 50% better than the signal-based OLE (Fig. 4d,e), and significantly stronger than in the PoS (Fig. 4e; p < 0.05; Mann-Whitney’s U-test; n = 20 ADn and 8 PoS cell ensembles, respectively).

Figure 4. Noise correlation of HD cells improves linear decoding.

a: Further analysis of the waking cross-correlograms shown in Fig. 2c. Superimposed purple curves display expected cross-correlation for independent, rate coding cells. b: Difference between actual and expected pairwise cross-correlations (noise correlation35) at 0-timelag as a function of difference between preferred head directions. Note excess at 0° (purple area) and dip at 60° (gray areas). c: Signal correlation (± s.e.m.) for ADn-ADn pairs, ADn-PoS pairs and PoS-PoS pairs for angular difference at 0°±15° (purple) and at 60°±15° (gray). d: Cross-validated median absolute error (± s.e.m.) of HD reconstruction from signal correlations in the ADn (left) and the PoS (right) using three different decoders. Optimal Linear Estimator (OLE) is based on tuning curve signal correlations (signal, green) or actual pairwise correlations (covariance, cov, yellow) and compared with a non-linear Bayesian Decoder (black) as a function of smoothing time window. e: Ratio of OLE absolute median error based on covariance (εOLEcov) or on tuning curves correlations (εOLEsig) taken at their minimal values (across temporal windows) in the ADn and the PoS (p = 0.009).

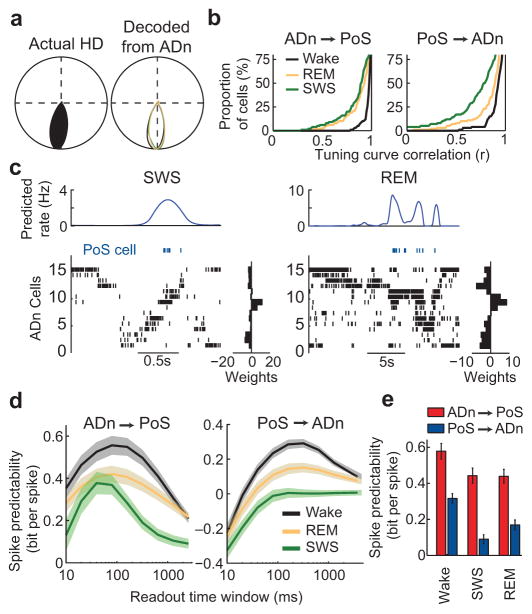

To gain insight into the direction of the interactions between the ADn and PoS components of this thalamo-cortical loop, we examined whether HD cells preserved their tuning curves during sleep based on the internal HD signal of the reciprocal area. To this end, we used the decoded HD signals during sleep from either the ADn or PoS assemblies to compute the HD tuning curves in their target PoS or ADn neurons, respectively. In agreement with the preservation of the activity packet across brain states (Fig. 3a,b), tuning curves were remarkably similar during sleep to that of waking (Fig. 5a,b; Supplementary Movie 1). However, the HD signal extracted from ADn assemblies resulted in tuning curves more similar to actual HD fields than the HD signal decoded from PoS assemblies, in all brain states (Fig. 5b; Mann-Whitney U test; wake: p < 10–10; SWS: p = 0.018; REM: p = 3×10−6; n = 86, 92 PoS and ADn HD cells respectively). Finally, to quantify how well ADn or PoS assemblies could predict the firing probability and timing of target cells in the PoS or ADn, respectively, we estimated the predictability of spike trains based on a Generalized Linear Model of cell ensemble activity36 (see Methods), at different time-scales (Fig. 5c–e). ADn assemblies predicted PoS spike trains reliably in all brain states (Fig. 5d,e; p < 10–10 in all brain states, Wilcoxon’s signed rank test, n = 86). Optimal readout windows were similar between waking and REM (median: 123 ms and 133 ms respectively) and shorter during SWS (median: 79 ms). In the reverse direction, PoS cell assemblies predicted spike trains of ADn neurons more weakly, especially during SWS (Fig. 5d,e; wake: p = 3×10−5, SWS: p < 10–10; REM: p = 1.1×10−6; Mann-Whitney U test; n = 86 and 62 PoS and ADn neurons respectively).

Figure 5. Transmission of HD information from the thalamus to the cortex.

a: Left: Tuning curve of an example PoS HD cell. Right, Tuning curves of the same PoS HD cell obtained from the Bayesian decoded HD signal from the ADn cell assembly during waking (black), REM (yellow) and SWS (green). b: Cumulative histogram of the correlation values between measured tuning curves and ADn decoded HD signal across brain states. c–d: Cross-validated prediction of cell spiking from population activity, independent of HD tuning curves across brain states. c: Examples of predicted firing rate of one PoS cell from ADn population activity learned during SWS (left) and REM (right) show high fidelity to actual spike train. Weights indicate the relative contribution of each ADn cell to the prediction. d: Left: Average PoS spike trains (n = 86) prediction (± s.e.m.) by cell assembly activity in the ADn for different readout time windows during waking, REM and SWS. Right: ADn spike trains (n = 62) predicted by PoS HD cell assembly. e: Maximal prediction average (at optimal readout windows) of PoS cells relative to ADn HD cell assemblies during waking, SWS and REM (red bars) and information content of ADn HD cells extracted from PoS HD cell assemblies (blue bars). Note that ADn to PoS predictions are higher than PoS to ADn predictions in all brain states (p < 10–5). Error bars display s.e.m.

Finally, we examined the fine timescale dynamics of HD neurons within and across structures. Spectral analysis of cross-correlation functions between pairs of HD cells in the ADn revealed strong oscillatory spiking dynamics activity in windows of approximately 1–5 ms (Fig. 6a). The degree of synchrony decreased with the magnitude of difference between the preferred head directions of the neurons (Fig. 6b; p < 10–10; Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 970 ADn HD cell pairs) in all brain states (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 7a). The high degree of synchrony displayed by ADn neurons can contribute to the effective discharge of their target neurons in PoS. In support of this hypothesis, cross-correlation analyses between pairs of ADn-PoS neurons revealed putative synaptic connections in a fraction of the pairs (4.45% of 6960 pairs from ADn to PoS, 0.35% from PoS to ADn; see Methods, Fig. 7a,b, Supplementary Fig. 7b), which included both putative PoS pyramidal cells and interneurons (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. 6). When only ADn and PoS pyramidal cell pairs were considered (3394 pairs), we found putative synaptic connections in both directions (Supplementary Fig. 7b) but the probability of feed-forward connections from the ADn to the PoS was twice as high as the PoS to ADn feedback direction (0.41% ADn-PoS pairs versus 0.18% PoS-ADn pairs; p = 0.014, binomial test). ADn cell spiking was associated with high frequency LFP oscillations in the PoS (Fig. 7c), indicating that the fast synchronous oscillation of ADn assemblies was also transmitted to PoS. Furthermore, PoS HD cells that were post-synaptic to ADn HD cells shared the same preferred direction as their presynaptic neuron (Fig. 7d, p = 0.68, Rayleigh test followed by Wilcoxon’s signed rank test, n = 12), suggesting direct forwarding of a ‘copy’ of the thalamic HD signal. Pyramidal neurons in PoS that were synaptically driven by ADn HD cells conveyed more HD information than PoS neurons for which a presynaptic cell could not be identified (Fig. 7e; p = 0.011, Mann-Whitney U-test). No such difference in HD information was observed between ADn neurons and putative interneurons in PoS (Fig. 7e; p = 0.38). These findings demonstrate that ADn and PoS cell assemblies are strongly synchronized and establish effective reciprocal communication.

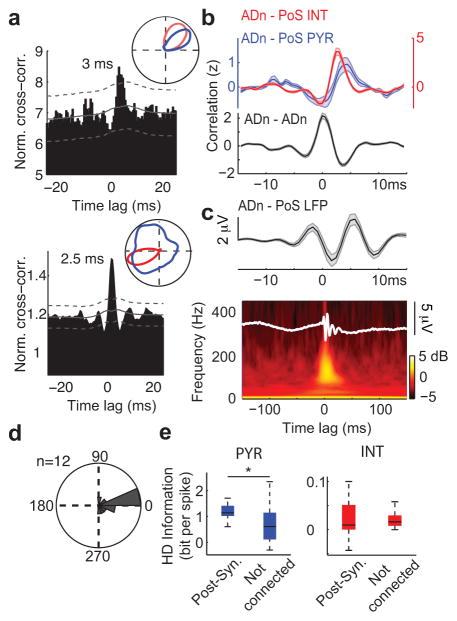

Figure 6. Fast synchronous oscillations in ADn HD cells.

a: Bottom, HD fields of the reference cell (dashed curve) and three other HD cells recorded on a different shank. Top: Examples of spike cross-correlogram between the three ADn cell pairs and their normalized (equal to 1 when independent) and z-scored cross-correlograms (number of s.d. from baseline obtained from 100 correlograms of spike trains jittered uniformly in ±10ms windows). Middle, wavelet transforms of z-scored cross-correlograms, all normalized to the same scale. b: Amplitude of pairwise synchrony (in z-values from baseline ± s.e.m., as in panel a) as a function of preferred direction difference (p < 10–10). c: Average power (± s.e.m.) of wavelet-transformed z-scored cross-correlograms across brain states.

Figure 7. ADn to PoS transmission of the HD signal.

a: Top, example cross-correlogram (black) between spikes of an ADn neuron (time 0) and a putative pyramidal PoS HD cell shows a sharp peak at positive time-lag, indicating a putative mono-synaptic connection. Solid gray line indicates expected firing rate after jittering the spikes by ±10ms. Dashed lines show the 99.9% interval of confidence. Inset: HD fields of the ADn (red) and PoS (blue) neurons. Bottom, same as top panel for an ADn neuron-PoS putative interneuron pair. b: Top, average cross-correlogram (± s.e.m.) of ADn HD cells mono-synaptically connected to putative pyramidal cells (blue) and interneurons (red). Bottom, average cross-correlograms between ADn HD cells. c: High frequency neuronal oscillations in the PoS. Bottom, average wideband (0 – 1250 Hz, ± s.e.m.) LFP trace triggered by ADn HD cell spikes (white trace) and color-coded average spectrum (in dB) of the LFP (based on all spikes of ADn HD cells in each session). Top: zoomed trace of the band-pass filtered LFP (80 – 250Hz). d: Distribution of the difference between preferred HD of individual ADn HD cells and their putative post-synaptic target neuron in PoS (p > 0.5). e: Left, distribution of HD information content of PoS pyramidal cells synaptically connected to recorded ADn HD cells (left) or not (right). * p = 0.011. Right, putative interneuron HD information content (p = 0.38).

Discussion

We report that correlated activity of thalamic ADn and PoS HD neurons are preserved across different brain states. These empirical observations demonstrate similarities to HD models of one-dimensional attractors where the activity packet moves on a ring8,18,19,22,25. We hypothesize that in the exploring animal, the exact tuning curves of HD neurons result from a combination of internal and external processes19,20,25,26,37 and can quickly rotate in response to environmental manipulations9,10 conveyed by vestibular and other peripheral inputs7,8.

Our findings provide experimental support for the postulated ring-attractor hypothesis of HD system organization18–20,24,26, although it remains to be clarified whether the HD attractor mechanism resides in the thalamus or is ‘inherited’ from more upstream structures. We found that during sleep the drift of the attractor can be independent of sensory inputs38 and the speed of the activity packet is determined by brain state dynamics. An expected advantage of the internally-organized HD attractor is that in the exploring animal sensory inputs7,8 can be combined with the prediction of the internally generated HD sense25,26 and rapidly adapt to reconfigured environments9,10. In case of ambiguous signals, the internally organized HD attractor mechanisms may substitute or improve the precision of HD information by interpolating across input signals and help resolve conflicts during navigation19,20,26. Overall, our observations demonstrate that coordinated neuronal activity in the HD system is shaped not only by the nature of incoming sensory HD signals but also strongly influenced by internal self-organized mechanisms. Importantly, the HD system may have analogous counterparts in other thalamus-mediated sensory systems as well.

The internally-organized HD system is ‘embedded’ in the internal global brain dynamics during sleep, including an ~10-fold time acceleration during SWS29–33 compared with waking and REM, reminiscent of the temporally ‘compressed’ replay of waking hippocampal and neocortical activity29–33,39. However, the magnitude of the persistent representation in the HD system is an order of magnitude higher than those previously reported in hippocampus and neocortex. A possible explanation for this robust effect is that the HD system processes a simple one-dimensional signal (i.e., the head angle), whereas neurons in cortical systems likely represent intersections of multiple representations (e.g., place, context, goals, speed and other idiothetic information). It should also be mentioned that, strictly speaking, replay refers to the increased correlations of neuronal coactivation after waking experience compared with the pre-experience control sleep31–33. In contrast to the robust wake-sleep correlations of firing rates, co-activation of neuron pairs and neuronal sequences during both SWS and REM sleep reported here, a previous report failed to find ‘replay’ in the PoS28. Potential explanations for such discrepancy include the rather large time window for Bayesian reconstruction (500ms) in that previous study28, which may have ‘filtered out’ the replay effect and/or the limited number of neuronal pairs that were available for statistical comparisons.

Similar to previous findings in visual40 and somatosensory41 systems, we observed highly reliable spike transmission between thalamic ADn and its cortical PoS target. Both putative interneurons and pyramidal cells of PoS were driven reliably at short latency by the ADn neurons, most of which were HD cells. The effectiveness of the ADn-PoS transmission was enhanced by a fast (130—160 Hz) oscillation synchrony of coherent HD cell assemblies in ADn in all brain states, which was also reflected in the ADn spike-triggered LFP in the PoS. Similar prominent oscillations have been described in the optic tectum of birds which have been shown to reflect synchronous co-firing of neighboring neurons to flashing or visual motion stimulation42. Importantly, firing patterns of PoS neurons could be reliably predicted from the population activity of ADn neurons. In the reversed direction, the prediction was poorer. Furthermore, HD prediction could be more reliably reconstructed from ADn than from PoS populations, especially during SWS28. These findings are compatible with a feed-forward labeled line transmission of sensory information from the periphery to cortex43. Yet, unexpectedly, the magnitude and reliability of internal prediction was higher in ADn than in PoS, at least when the same total number of neurons was used for HD reconstruction. One possible explanation for such difference is that neurons of ADn are dedicated specifically to HD information, whereas PoS neurons respond to a variety of other inputs as well, making them appear ‘noisier’. It is possible, however, that if a much larger fraction of PoS were to be recorded, PoS activity could be equally predictive.

Although the exact anatomical substrate of the hypothetical self-organized attractor remains to be identified, three findings are in favor of the involvement of the thalamocortical circuits. First, the ‘noise’ correlations between ADn neuron pairs are in support of locally-organized mechanisms. Second, the speed of rotation of the HD neurons varied with the thalamocortical state, indicating direct cortical influence on the substrate of the attractor29–33. Third, processing of the HD signal was embedded within fast oscillations that coordinated HD cell assemblies within and across ADn and PoS. Thus, the ADn-PoS-ADn excitatory loop may also contribute to the postulated attractor. Finally, although ADn neurons do not excite each other or other thalamic nuclei44 they can communicate with each other via the inhibitory neurons of the reticular nucleus45,46. Recent work has demonstrated that such recurrent inhibitory connectivity can also give rise to internally-organized activity47,48. We note that several models assume that HD information is critical for the integrity of entorhinal grid cells12,49, which tessellate the explored space with equilateral triangles50. Notably, the structural requirements of a prominent grid model is identical to the recurrent inhibitory loops of the ADn-reticular nucleus circuit47,48. How the internally-organized HD system is related to the formation of grid cells remains to be determined.

Methods

Electrodes, surgery and data acquisition

All experiments were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of New York University Medical Center. Five adult male and two female mice (27 – 50 g) were implanted with recording electrodes under isoflurane anesthesia, as described earlier51. Silicon probes (Neuronexus Inc. Ann Arbor, MI) were mounted on movable drives for recording of neuronal activity and local field potentials (LFP) in the anterior thalamus (n = 7 mice) and, in addition in the post-subiculum (n = 3 out of 7 mice). In the four animals implanted only in the anterior thalamus, electrodes were also implanted in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal layer for accurate sleep scoring: three to six 50 μm tungsten wires (Tungsten 99.95%, California Wire Company) were inserted in silicate tubes and attached to a micromanipulator. Thalamic probes were implanted in the left hemisphere, perpendicularly to the midline, (AP: –0.6 mm; ML:–0.5 to –1.9 mm; DV: 2.2 mm), with a 10 – 15° angle, the shanks pointing toward midline (see Supplementary Fig. 1a–f). Post-subicular probes were inserted at the following coordinates: AP: –4.25 mm: ML: –1 to –2 mm; DV: 0.75 mm (Supplementary Fig. 1g,h). Hippocampal wire bundles were implanted above CA1 (AP: –2.2 mm; –1 to –1.6 mm ML; 1 mm DV). The probes consisted of 4, 6 or 8 shanks (200-μm shank separation) and each shank had 8 (4 or 8 shank probes; Buz32 or Buz64 Neuronexus) or 10 recording (6-shank probes; Buz64s) sites (160 μm2 each site; 1–3 M impedance), staggered to provide a two-dimensional arrangement (20 μm vertical separation). In all experiments ground and reference screws or 100-μm diameter tungsten wires were implanted in the bone above the cerebellum.

During the recording session, neurophysiological signals were acquired continuously at 20 kHz on a 256-channel Amplipex system (Szeged, Hungary; 16-bit resolution; analog multiplexing)52. The wide-band signal was downsampled to 1.25 kHz and used as the LFP signal. For tracking the position of the animals on the open maze and in its home cage during rest epochs, two small light-emitting diodes (5 cm separation), mounted above the headstage, were recorded by a digital video camera at 30 frames per second. The LED locations were detected online and resampled at 39 Hz by the acquisition system (note that the absolute time of the first video frame was randomly misaligned by 0–60ms but the sampling rate was accurate thereafter). Spike sorting was performed semi-automatically, using KlustaKwik53 (available at: http://klustakwik.sourceforge.net). This was followed by manual adjustment of the waveform clusters using the software Klusters54. Examples of simultaneously recorded neurons and quantification of isolation quality are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

After 4–7 days of recovery, the thalamic probes were lowered until the first thalamic units could be detected on at least 2–3 shanks. At the same time, hippocampal wires were slowly lowered until reaching the CA1 pyramidal layer, characterized by high amplitude ripple oscillations. The probe was then lowered by 70–140 μm at the end of each session.

In the animals implanted in both the thalamus and in the PoS, the subicular probe was moved everyday once large HD cell ensembles were recorded from the thalamus. Thereafter, the thalamic probes were left at the same position as long as the quality of the recordings remained. They were subsequently adjusted to optimize the yield of HD cells. To prevent statistical bias of neuron sampling, we discarded from analysis sessions separated by less than three days during which the thalamic probe was not moved.

Three animals had channelrhodopsin conditionally expressed in parvalbumin (one animal) or CamKII (two animals) positive neurons but these aspects of the experiments are not part of the present study.

Recording sessions and behavioral paradigm

Recording sessions were composed of exploration of an open environment (‘wake’ phase) during which the animals were foraging for food for 30 to 45 minutes. The environment was a 53 × 46 cm rectangular arena surrounded by 21-cm high, black-painted walls on which were displayed two salient visual cues. The exploration phase was (in 41 out of 42 sessions) preceded and followed by sleep sessions of about 2 hours duration. In one session, the exploration of a radial maze following the second sleep phase was considered as the ‘wake’ period and no sleep was recorded subsequently. All experiments were carried out during daylight in normal light-dark cycle.

Data analysis and statistics

Head direction cells

The animal’s head direction was calculated by the relative orientation of a blue and red LEDs located on top of the head (see above). The head direction fields were computed as the ratio between histograms of spike count and total time spent in each direction in bins of 1 degree and smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 6° s.d.. Times when one of the LEDs was not detected were excluded from the analysis. The distributions of angular values making the HD fields were fitted with von Mises distributions defined by their circular mean (preferred HD), concentration (equivalent to the inverse of the variance for angular value variables) and peak firing rates. The probability of the null hypothesis of uniformly distributed firing in all directions was evaluated with a Rayleigh test. Neurons were classified as HD cells for concentration parameter exceeding 1, peak firing rates greater than 1Hz and probability of non-uniform distribution smaller than 0.001. In all cross-correlation analyses, only cells firing at least at 0.5 Hz in any of the three brain states were included.

242 out of 720 recorded cells (41% on average) in the anterior thalamus, and 111 out of 357 (31%) cells in the PoS were classified as HD cells. In the thalamus, when considering only cell ensembles recorded on silicon probe shanks where at least one HD cell was detected, the average proportion of HD cells was 71%, a number close to the previous estimation of HD cell density in this structure.

Sleep scoring

Sleep stage scoring was assessed on the basis of time-resolved spectrograms of the CA1 pyramidal layer or PoS LFPs, and of the movement of the animal. Behavioral stages were first detected by automatic software based on a Bayesian hierarchical clustering method, whose relative weights were learned from hand-scored data. Stages were then visually inspected and manually adjusted55.

Bayesian reconstruction of Head-Direction

Following Zhang et al.56, the ‘internal’ head-direction (as displayed in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2) was reconstructed using a Bayesian framework. In short, at each time bin (10ms, smoothed in 300 ms s.d. Gaussian windows for wake and REM, 50 ms windows for SWS), based on cells’ tuning curves from waking spike data, the population vectors were converted into a probabilistic map under the hypothesis that HD cells fire as a Poisson process. The instantaneous ‘internal’ head-directions were taken as the maxima of these probabilistic maps. Bayesian reconstruction was used only when at least 6 HD cells were recorded in one given structure (ADn or PoS). These estimates faithfully tracked the head position in the waking mouse.

Estimation of angular velocity

Under the hypothesis of independent rate-coded cells, temporal cross-correlograms between two HD neurons depend primarily on two parameters: the tuning curves of the neurons and timecourse of the angular velocity of the animal’s head. Specifically, the cross-correlogram depends on the angular correlation ρ(θ) between the two tuning curves, determined as the correlation of firing rates as a function of angular offset.

One way to interpret a temporal cross-correlogram is the following: at angular velocity υ, it takes a time τ to cover a angular distance θ=υτ; thus, at time lag τ, the temporal correlation can be approximated by the average angular correlation: 〈ρ(θ)〉v = 〈ρ(vτ)〉v (〈.〉v denotes average over all possible angular velocities). Therefore, we hypothesized that the temporal cross-correlation estimates the average angular speed, assuming a model of angular velocity distribution and knowing the angular correlation between the two tuning curves. To this end, we searched for the average velocity which best predicted the observed cross-correlograms. First, the angular speed distribution is assumed to be a Chi-squared distribution with 3 degrees of freedom, but the final results held for other non-normal (i.e. skewed) and positive random variables. Next, an expected temporal cross-correlogram is built and compared to the observed correlation. An unconstrained, derivative-free optimization algorithm searches for the average velocity υ minimizing the sum of squared difference between the estimated and observed cross-correlograms (the cost function). A first coarse-grained estimation of the cost function on a broad range of possible velocities gives a first approximation of υ. It is used as an initial condition for the fine search of the optimal value to improve the accuracy and computation speed of the algorithm. See Supplementary Fig. 4 for an illustration of this algorithm.

Cross-correlation under the hypothesis of independent firing rate coding scheme

To further understand if an animal’s behavior could fully account for the observed correlations during waking, (i.e. if the correlation was simply the result of first order interactions), we computed the expected correlations under the hypothesis of independent firing rates. To this end, we constructed for each neuron an ‘intensity’ function f(t) based on the animal’s instantaneous head direction and the cell’s tuning curve. Therefore, for neuron i, fi(t) = hi(θ(t)), where θ(t) is the orientation of the animal at time t and hi the head-direction field of cell i.

The cross-correlations Cij(t) (red lines in Fig. 3b) of the discretized intensity functions fi(t) and fj(t) were computed as follows:

where N is the length of the vectors fi and fj.

Head-direction and neuronal data were binned in 10 ms windows. To ensure a valid comparison, correlations of the binned spike trains were computed the same way as the intensity functions. The difference between the intensity function and binned spike train correlations averaged between –50 and +50 ms was referred to as ‘noise’ correlations35 (see Fig. 3c,d).

Information measures

These methods aim to quantify the predictability of a spike train relatively to a given behavioral or physiological observable36. In short, as described in the previous section, a spike train can be predicted by an intensity function f. It can be shown57 that the log-likelihood Lf of a spike train {ts}, given a given intensity function, is:

This log-likelihood, measuring the predictability of the spike train, was compared with the log-likelihood L0 of a homogeneously firing neuron, at the average firing rate observed during the training epoch. Thus, the predictability of the spike train was defined as the difference (or log-likelihood ratio) L=Lf − L0.

This predictability can be interpreted as an information rate about the variable used to generate the intensity function. It is thus expressed in bit per second. Throughout the paper, these rates were normalized by the cell’s firing rate during the epochs of interest and were thus given in bit per spike.

To quantify the predictability of a spike train, we used a cross-validation procedure. The log-likelihood ratio was thus computed on a different epoch, the test set, than the one used to train the intensity function, the training set. Each epoch of interest was divided in 10 segments: spike train from one segment was tested against the intensity function estimated from the training set made from the remaining 9 other segments.

The simplest case is the estimation of the head-direction information content as shown in Fig. 1e. The head direction field Htraining(θ) of a cell is generated on the training set, that is 90% of the wake epoch. Knowing the behavior of the animal (i.e. its head direction θ(t)) during the test epoch (the remaining 10% of the waking period), the spike trains were tested against the intensity function f(t) = Htraining (θ(t)).

To quantify the extent to which a cell ensemble can predict the spiking of a given neuron (as in Fig. 4f), the intensity function was derived from a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) of the ensemble spiking activity. More specifically, a rate r(t) was defined, for each time, as a linear combination of the activity of the cells belonging to the ensemble:

where ωi is the weights associated with the neuron i in the predictive ensemble, and qi(t) its activity at time t.

The associated intensity function was then defined as:

where the link function g is a modified exponential function (linear for positive arguments), a necessary modification to avoid excessively high predicted intensities36.

The spiking activity of the cells was binned in 10 ms windows. It was then convolved with Gaussian kernels of variable width, referred to as “readout windows” in Fig. 4.

The weights were determined by minimizing for each training set the log-likelihood ratio using a multivariate, unconstrained and derivative-free search algorithm. To improve computation speed, the weights of the first training set were used as initial conditions for the nine others.

Only the neurons that were positively predicted for at least one readout time window were included in the final analysis in Fig. 4f,g (ADn from PoS assemblies: n = 62; PoS from ADn assemblies: n = 86).

Ensemble coherence

To examine the coherence of the activity packet we applied the measure as described in ref34: the actual activity packet (the sum of the normalized tuning curves weighted by the instantaneous firing rates) was compared to the expected activity packet given the estimated HD by a Bayesian decoding of the population. To build proper statistics (and normalize between 0 and 1 the coherence measure), for each degree of the HD, 5,000 population vectors were randomly chosen from the wake recordings and compared to the expected packet at the decoded angle. Next, the actual packets during each brain state were tested under the null hypothesis that they are similar to the expected packets at the decoded HD. A coherence measure close to 1 (and, statistically speaking whenever it is greater than 0.05) indicates significant similarity.

Detection of mono-synaptic connections

The spike train cross-correlogram of two neurons can reveal synaptic contacts between each other58,59. This takes the form in the cross-correlogram of short time-lag (1 – 10 ms) positive or negative deviations from baseline indicating putative excitatory or inhibitory connections, respectively. Such detection is based on statistics testing the null hypothesis of a homogeneous baseline at short time-scale58. To this end, cross-correlograms binned in 0.5 ms windows were convolved with a 10 ms s.d. Gaussian window resulting in a predictor of the baseline rate. At each time bin, the 99.9th percentile of the cumulative Poisson distribution (at the predicted rate) was used at the statistical threshold for significant detection of outliers from baseline. In this study, we focused on excitatory connections for two reasons: (i) all thalamo-cortical and cortico-thalamic connections are expected to be excitatory and (ii) all candidates for inhibitory connections resulted from short timescale oscillatory processes associated with a excitatory connection in the other direction. A putative connection was considered significant when at least two consecutive bins in the cross-correlograms passed the statistical test.

Classification of PoS neurons as putative interneurons or pyramidal cells

Cortical pyramidal cells and the majority of cortical GABAergic interneurons were classified on the basis of their waveform features60,61. Putative pyramidal were characterized by broad waveforms whereas putative interneurons had narrow spikes. To separate between the two classes of cells, we used two waveform features: (i) total duration of the spike, defined as the inverse of the maximum power associated frequency in its power spectrum (obtained from a wavelet transform) and (ii) the trough-to-peak duration (Supplementary Fig. 6). Putative interneurons were defined as cells with narrow waveform (duration <0.9ms) and short trough to peak (< 0.42 ms). Conversely, cells with broad waveforms (duration >0.95 ms) and long trough-to-peak (> 0.42 ms) were classified as putative pyramidal cells.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Matlab (MathWorks). Number of animals and number of recorded cells were similar to those generally employed in the field6,10,11,28. All tests were two-tailed. For all tests, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test, Wilkinson’s signed rank test and Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance were used. Correlations were computed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute of Health Grants NS34994, MH54671 and NS074015, the Human Frontier Science Program and the J.D. McDonnell Foundation. AP was supported by EMBO Fellowship ALTF 1345-2010, Human Frontier Science Program Fellowship LT000160/2011-L and National Institute of Health Award K99 NS086915-01.

Footnotes

Author contribution:

AP and GB designed experiments; AP, ML and PP conducted experiments; AP designed and performed analyses; AP and GB wrote the paper with input from other authors.

References

- 1.Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J. The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:229–239. doi: 10.1038/35067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel AK, Singer W. Temporal binding and the neural correlates of sensory awareness. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:16–25. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buzsáki G. Rhythms of the brain. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao RP, Ballard DH. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:79–87. doi: 10.1038/4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranck J. In: Electrical Activity of Archicortex. Buzsáki G, Vanderwolf CH, editors. Akademiai Kiado; 1985. pp. 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taube JS, Muller RU, Ranck JB., Jr Head-direction cells recorded from the postsubiculum in freely moving rats II Effects of environmental manipulations. J Neurosci. 1990;10:436–447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-02-00436.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taube JS. The head direction signal: origins and sensory-motor integration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:181–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp PE, Blair HT, Cho J. The anatomical and computational basis of the rat head-direction cell signal. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taube JS. Head direction cells recorded in the anterior thalamic nuclei of freely moving rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:70–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00070.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zugaro MB, Arleo A, Berthoz A, Wiener SI. Rapid spatial reorientation and head direction cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3478–3482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03478.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti HS, McNaughton BL. Place cells, head direction cells, and the learning of landmark stability. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1648–1659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01648.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNaughton BL, Battaglia FP, Jensen O, Moser EI, Moser MB. Path integration and the neural basis of the ‘cognitive map’. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:663–678. doi: 10.1038/nrn1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargolini F, et al. Conjunctive representation of position, direction, and velocity in entorhinal cortex. Science. 2006;312:758–762. doi: 10.1126/science.1125572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodridge JP, Taube JS. Interaction between the postsubiculum and anterior thalamus in the generation of head direction cell activity. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9315–9330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09315.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandon MP, et al. Reduction of Theta Rhythm Dissociates Grid Cell Spatial Periodicity from Directional Tuning. Science. 2011;332:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.1201652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langston RF, et al. Development of the spatial representation system in the rat. Science. 2010;328:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1188210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wills TJ, Cacucci F, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Development of the hippocampal cognitive map in preweanling rats. Science. 2010;328:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1188224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skaggs WE, Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti HS, McNaughton BL. A model of the neural basis of the rat’s sense of direction. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 1995;7:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang K. Representation of spatial orientation by the intrinsic dynamics of the head-direction cell ensemble: a theory. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2112–2126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02112.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redish AD, Elga AN, Touretzky DS. A coupled attractor model of the rodent head direction system. Netw Comput Neural Syst. 1996;7:671–685. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burak Y, Fiete IR. Fundamental limits on persistent activity in networks of noisy neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:17645–17650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117386109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knierim JJ, Zhang K. Attractor Dynamics of Spatially Correlated Neural Activity in the Limbic System. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:267–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blair HT. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 8. Touretzky DS, Mozer MC, Hasselmo ME, editors. MIT Press; 1996. pp. 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amari DS. Dynamics of pattern formation in lateral-inhibition type neural fields. Biol Cybern. 1977;27:77–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00337259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song P, Wang WJ. Angular path integration by moving “hill of activity”: a spiking neuron model without recurrent excitation of the head-direction system. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1002–1014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4172-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Yishai R, Bar-Or RL, Sompolinsky H. Theory of orientation tuning in visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3844–3848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buzsaki G. Two-stage model of memory trace formation: a role for ‘noisy’ brain states. Neuroscience. 1989;31:551–570. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandon MP, Bogaard AR, Andrews CM, Hasselmo ME. Head direction cells in the postsubiculum do not show replay of prior waking sequences during sleep. Hippocampus. 2012;22:604–618. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science. 1996;271:1870–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nádasdy Z, Hirase H, Czurkó A, Csicsvari J, Buzsáki G. Replay and time compression of recurring spike sequences in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9497–9507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09497.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002;36:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Euston DR, Tatsuno M, McNaughton BL. Fast-forward playback of recent memory sequences in prefrontal cortex during sleep. Science. 2007;318:1147–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1148979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peyrache A, Khamassi M, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, Battaglia FP. Replay of rule-learning related neural patterns in the prefrontal cortex during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:919–926. doi: 10.1038/nn.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson A, Seeland K, Redish AD. Reconstruction of the postsubiculum head direction signal from neural ensembles. Hippocampus. 2005;15:86–96. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Averbeck BB, Latham PE, Pouget A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrn1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris KD, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Dragoi G, Buzsaki G. Organization of cell assemblies in the hippocampus. Nature. 2003;424:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature01834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta MR, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Experience-dependent, asymmetric expansion of hippocampal place fields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muir GM, et al. Disruption of the Head Direction Cell Signal after Occlusion of the Semicircular Canals in the Freely Moving Chinchilla. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14521–14533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3450-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science. 1994;265:676. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clay Reid R, Alonso JM. Specificity of monosynaptic connections from thalamus to visual cortex. Nature. 1995;378:281–284. doi: 10.1038/378281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruno RM, Sakmann B. Cortex Is Driven by Weak but Synchronously Active Thalamocortical Synapses. Science. 2006;312:1622–1627. doi: 10.1126/science.1124593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuenschwander S, Varela FJ. Visually Triggered Neuronal Oscillations in the Pigeon: An Autocorrelation Study of Tectal Activity. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:870–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craig AD. Pain mechanisms: labeled lines versus convergence in central processing. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131022. Bud. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones EG. The Thalamus. Cambridge Univ Pr; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shibata H. Topographic organization of subcortical projections to the anterior thalamic nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:117–127. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalo-Ruiz A, Lieberman AR. Topographic organization of projections from the thalamic reticular nucleus to the anterior thalamic nuclei in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:17–35. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Couey JJ, et al. Recurrent inhibitory circuitry as a mechanism for grid formation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nn.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moser EI, Moser MB, Roudi Y. Network mechanisms of grid cells. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20120511. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burgess N, Barry C, O’Keefe J. An oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing. Hippocampus. 2007;17:801–812. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moser EI, Kropff E, Moser MB. Place cells, grid cells, and the brain’s spatial representation system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stark E, Koos T, Buzsáki G. Diode probes for spatiotemporal optical control of multiple neurons in freely moving animals. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:349–363. doi: 10.1152/jn.00153.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berényi A, et al. Large-scale, high-density (up to 512 channels) recording of local circuits in behaving animals. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:1132–1149. doi: 10.1152/jn.00785.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris KD, Henze DA, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Buzsáki G. Accuracy of tetrode spike separation as determined by simultaneous intracellular and extracellular measurements. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:401–414. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hazan L, Zugaro M, Buzsáki G. Klusters, NeuroScope, NDManager: A free software suite for neurophysiological data processing and visualization. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;155:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grosmark AD, Mizuseki K, Pastalkova E, Diba K, Buzsáki G. REM sleep reorganizes hippocampal excitability. Neuron. 2012;75:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang K, Ginzburg I, McNaughton BL, Sejnowski TJ. Interpreting Neuronal Population Activity by Reconstruction: Unified Framework With Application to Hippocampal Place Cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1017–1044. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown Emery N, Barbieri Riccardo, Eden Uri T, Frank Loren M. In: Computational Neuroscience. Feng Jianfeng., editor. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stark E, Abeles M. Unbiased estimation of precise temporal correlations between spike trains. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;179:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujisawa S, Amarasingham A, Harrison MT, Buzsáki G. Behavior-dependent short-term assembly dynamics in the medial prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nn.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCormick DA, Connors BW, Lighthall JW, Prince DA. Comparative electrophysiology of pyramidal and sparsely spiny stellate neurons of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:782–806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bartho P. Characterization of Neocortical Principal Cells and Interneurons by Network Interactions and Extracellular Features. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:600–608. doi: 10.1152/jn.01170.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.