Abstract

Objective

To present methods and baseline data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE), the only clinical trial designed to specifically test the timing hypothesis of postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT). The timing hypothesis posits that HT effects depend on the temporal initiation of HT relative to time-since-menopause.

Methods

ELITE is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with a 2x2 factorial design. 643 healthy postmenopausal women without cardiovascular disease were randomized to oral estradiol or placebo for up to 6-7 years according to number of years-since-menopause, <6 years or ≥10 years. Carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) and cardiac computed tomography were conducted to determine HT effects on subclinical atherosclerosis across menopause strata.

Results

Participants in the early and late postmenopausal strata were well-separated by mean age, 55.4 versus 65.4 years and median time-since-menopause, 3.5 versus 14.3 years, respectively. The expected risk factors were associated with CIMT at baseline in both strata (age, blood pressure and body mass index). In the early but not in the late postmenopausal group, there were significant associations between CIMT and factors that may play a role in responsiveness of atherosclerosis progression according to timing of HT initiation. These include LDL-C, HDLC, sex hormone binding globulin and serum total estradiol.

Conclusion

The ELITE randomized controlled trial is timely and unique. Baseline data indicate that ELITE is well-positioned to test the HT timing hypothesis in relation to atherosclerosis progression and coronary artery disease. (NCT00114517; www.clinicaltrials.gov)

Keywords: menopause, postmenopause, women, hormone therapy, estrogen, randomized trials, cardiovascular disease, cognition, timing hypothesis

INTRODUCTION

The “timing,” “critical window” or “window of opportunity” hypothesis of hormone therapy (HT) was proposed to explain the difference in outcomes between randomized clinical event trials and observational studies of coronary heart disease (1,2), cognition and dementia (3,4). The timing hypothesis posits that HT benefits and risks depend on the temporal initiation of HT relative to time-since-menopause, age or both, which are in turn related to the health of the underlying tissue (i.e., healthy vascular endothelium and extent of atherosclerosis burden) or to some other factor such as age-related reduction in estrogen receptors or receptor down-regulation (5,6). The divergent results between the atherosclerosis progression sister trials Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial (EPAT) (5) and the Women's Estrogen Lipid-Lowering Hormone Atherosclerosis Regression Trial (WELL-HART) (6) provided early clinical trial support for this hypothesis. While EPAT demonstrated a reduction of subclinical atherosclerosis progression with HT in postmenopausal women without demonstrable atherosclerosis, WELL-HART demonstrated a null effect in postmenopausal women with documented coronary artery atherosclerosis (5,6). Experimental animal studies (7-9) replicate the divergent effects of HT on atherosclerosis as shown in EPAT and WELL-HART, findings later complemented by clinical outcome trials such as the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) (10). With completion of EPAT and WELL-HART, a new randomized controlled trial to test the timing hypothesis was proposed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in early 2002 entitled the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE).

Data supporting the timing hypothesis has grown considerably over the past decade since initiation of ELITE (1). ELITE remains unique and timely as the only randomized controlled trial specifically designed to test the timing hypothesis of HT in relation to atherosclerosis progression and cognitive change in postmenopausal women. The primary ELITE hypothesis is that postmenopausal HT will reduce the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease (CAD) and cognitive change in postmenopausal women without clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) when initiated soon after menopause (<6 years) relative to initiation of HT when distant from menopause (≥10 years). The subclinical atherosclerosis baseline data are detailed in this publication; the cognitive baseline data are detailed elsewhere (11).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

ELITE is a single-center, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, non-invasive serial arterial imaging, prospective trial with a 2x2 factorial design (NCT00114517). Healthy postmenopausal women without clinical evidence of CVD were randomized to active HT or to placebo according to the number of years-since-menopause, <6 years (early postmenopause) or ≥10 years (late postmenopause). Recruitment was initially based on a 5-year trial (3-year recruitment period and 2 to 5 years of randomized treatment). In the fifth year of randomized follow-up, the trial was extended for an additional 2.5 years of randomized intervention. As part of the ELITE extension, a third cognitive assessment was added (11) and measurements of subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis were obtained as participants completed the trial.

Treatment

Women with a uterus were randomized to oral micronized 17β-estradiol 1 mg/day with vaginal micronized progesterone gel 4% (45 mg) per day for 10 days each month or to double matched placebos. Women without a uterus were randomized to oral micronized 17β-estradiol 1 mg/day alone or to placebo.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible participants were postmenopausal women without clinical evidence of CVD, with a serum estradiol level <25 pg/ml and cessation of regular menses for a minimum of 6 months who were <6 years or ≥10 years-since-menopause at the time of randomization. Exclusion criteria included: women in whom time-since-menopause could not be determined; fasting plasma triglyceride level ≥500 mg/dl; diabetes mellitus or fasting serum blood glucose >140 mg/dl; serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL; uncontrolled hypertension (systolic/diastolic blood pressure >160/110 mmHg); untreated thyroid disease; life threatening disease with prognosis <5 years; history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or breast cancer; current postmenopausal HT (within past 1 month of screening).

Randomization

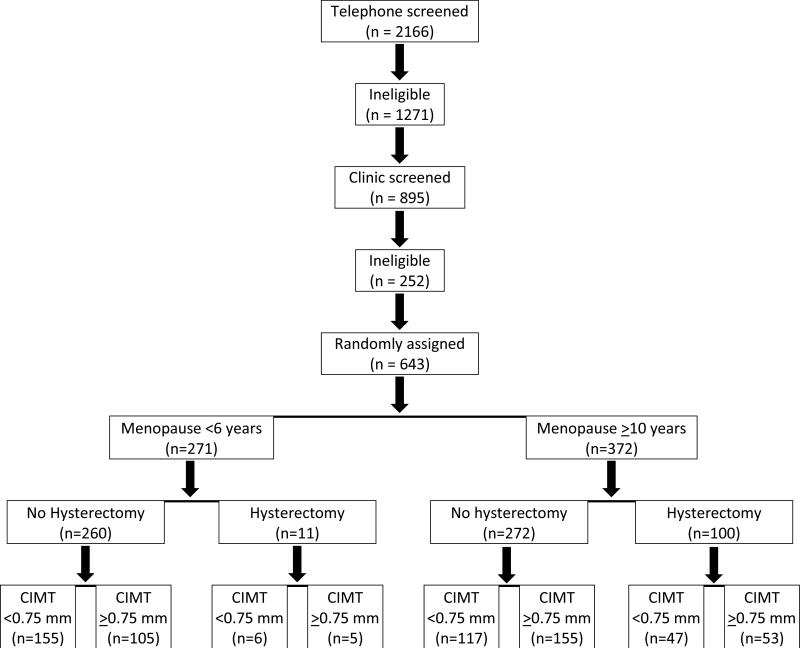

Participants were randomized to active HT or to placebo in strata defined by number of years since menopause, <6 years or >10 years. Additional randomization stratification factors included hysterectomy (yes, no) and baseline carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) (<0.75 mm or >0.75 mm) (Figure 1). Trial eligibility was assessed at the screening and baseline visits and confirmed at the data coordinating center. Assignment to HT or to placebo in a 1:1 ratio used stratified blocked randomization not identified to study personnel. Randomization lists for each of 8 strata were prepared prior to trial initiation by the trial statistician; blinded study product was prepared based on the stratified randomization lists. Upon determination of trial eligibility and stratum for a given participant, clinic staff pulled the next study product in sequence from the appropriate stratum and recorded the product identification number. The fidelity of the randomization process was monitored at the data coordination center. Participants, investigators, staff, imaging specialists and data monitors were masked to treatment assignment.

Figure.

CONSORT flowchart for the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol summarizing the recruitment and randomization process.

Follow-up

Following randomization, participant evaluations were conducted in a specialized research clinic every month for the first 6 months of the trial and then every other month until trial completion. All baseline evaluations were conducted prior to randomization. Every 6 months, fasting blood was obtained for the following analyses: plasma estradiol was quantified by radioimmunoassay with preceding organic solvent extract and Celite column partition chromatography steps (12); sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) was measured on the Immunlite analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfiled, IL); plasma lipids and lipoproteins (total cholesterol (C), total triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-C, LDL-TG, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-C, VLDL-TG, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-C and HDL-TG) were measured by preparative ultracentrifugation and enzymatic assays standardized to the CDC using Lipid Research Clinic protocol (5); and, plasma hemoglobin A1c was determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography-ion exchange chromatography (DCCT approved method) (13). Complete blood count and chemistry panel were completed yearly by Quest Diagnostics.

Following clinical assessment at baseline prior to randomization, blood pressure, pulse rate and weight were determined at each visit. Waist and hip circumferences were obtained every 6 months and height was obtained at baseline. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained yearly. Questionnaires covering medical history, angina, claudication, physical activity and smoking and alcohol use were administered every 6 months. Study product compliance, clinical events (MedDRA-coded) and non-study medication and nutritional supplement use were ascertained at every clinic visit. Participants completed 3-day dietary booklets (Nutrition Scientific) prior to the baseline visit and prior to each subsequent clinic visit.

A reproductive history was obtained at baseline and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale and the Women's Health Questionnaire (14) covering physical and emotional health were administered at baseline prior to randomization and every 6 months. Participants completed flushing, vaginal bleeding and cramping and breast pain diaries that were collected at baseline and at each clinic visit. Baseline, annually and as indicated, mammography, gynecological examinations including a Pap smear, transvaginal uterine ultrasound and endometrial biopsy (if indicated) were performed.

Primary endpoint

All women meeting trial inclusion criteria underwent 2 baseline B-mode carotid artery ultrasound examinations to acquire standardized images for CIMT measurements. The first CIMT was assessed at the screening visit and was used to determine randomization stratum. The second CIMT was conducted at the baseline visit prior to randomization in the women meeting the final trial inclusion criteria. The time interval between the first and second CIMT was 2-4 weeks. The primary trial endpoint is the rate of change of the right distal common carotid artery (CCA) far wall intima-media thickness (IMT) in computer image processed B-mode ultrasonograms over the 2 baseline examinations and serial examinations completed every 6 months over trial follow-up (5). High resolution B-mode ultrasound imaging and measurement of far wall CIMT was conducted using standardized procedures and technology specifically developed for longitudinal measurements of atherosclerosis change (Patents 2005, 2006, 2011). Details of the ultrasound acquisition and CIMT measurement procedures are described elsewhere (5,15-17) and in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Secondary endpoints

The secondary endpoints include measurement of cognition and coronary artery atherosclerosis. Details of the neuropsychological tests, procedures and statistical analyses are described elsewhere (11,18). Subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis was assessed with cardiac computed tomography (CT) scanning for coronary artery calcium (CAC) and cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) for measurement of coronary artery stenoses in a single session using a dedicated cardiac GE 64 slice multi-detector computed tomography (64 MDCT) scanner as participants completed randomized treatment. The CT end points represent a comprehensive assessment of coronary artery atherosclerosis across all of the coronary artery segments of total CAC, total stenosis score, total plaque score and composition of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Details of the CAC and CCTA methods are described elsewhere (19,20) and in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Sample size

The sample size was based on a projected mean treatment group difference in the CIMT change rate among women <6 and >10 years-since-menopause (placebo-treated rate minus estradiol-treated rate) of 0.0144 and 0.0021 mm/year, respectively, and standard deviation (SD) of CIMT change rate of 0.02 mm/year. Sample size based on CIMT progression required 83 participants in each cell (126 participants per cell including an anticipated 25% dropout) to detect treatment-by-time-since-menopause interaction in the 2x2 factorial design with 80% power, testing at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. This sample size was also projected to yield a power of 96% to detect a significant treatment group difference in the CIMT progression rates in the early postmenopausal group.

Statistical analysis

Baseline comparisons will be made between treatment arms (within time-since-menopause strata) with respect to demographic, medical history, baseline risk factors (blood pressure, smoking, lipids), previous hormone use, estradiol and progesterone levels and baseline CIMT. Analytical methods will include two-sample t-tests (or a non-parametric analog) for continuous variables and chi-square procedures for categorical variables. All treatment group comparisons on baseline variables will be performed for the entire randomized study sample and for the group of participants with repeat (post-randomization) carotid ultrasounds.

Evaluation of potential biases introduced by differential dropout (comparing participants with and without post-randomization ultrasound by treatment group) will be determined. Analytic methods will utilize standard univariate procedures for the total sample and by time-since-menopause strata to compare these participant groups on baseline demographics and baseline levels of laboratory and lifestyle variables.

On-trial levels of laboratory variables (plasma lipids, lipoproteins, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and estradiol and progesterone levels) will be compared between treatment groups using marginal models with generalized estimating equations. Independent factors will be treatment group, time-since-menopause and randomization stratification factors; the baseline levels of the on-trial dependent variables will be included as a covariate. The primary tests of interest are the overall treatment group comparisons. Differences in the randomized treatment effect by menopause strata will also be tested with addition of a product interaction term. Statistical evaluations will report the overall test for treatment group difference, the overall test for differences between the time-since-menopause groups as well as the interaction p-value. Treatment group comparisons will be performed for the group of participants with any post-randomization carotid ultrasound and for the adherent participants (adherent analysis) defined as >80% compliance with estrogen therapy.

The primary endpoint will be the per-participant rate of change in the right distal CCA far wall IMT. Statistical analyses will use linear mixed effects linear models; treatment group and time-since-menopause group will be included as indicator variables, with the randomization stratification variables (type of menopause and dichotomous baseline CIMT) included as covariates. Random effects will be specified for the participant-specific intercept (baseline CIMT) and slope (CIMT rate of change). The overall treatment group difference in the mean CIMT rate will be tested with a 2-way treatment group by time-on-study interaction. A 2-way time-since-menopause group-by-time on-study interaction term will test whether the mean CIMT progression rate differs among the 2 menopause groups. The hypothesis that the treatment group effects on the CIMT rate differs by time-since-menopause will be tested with a time-since-menopause-by-treatment-by-time on-study interaction term. Treatment group comparisons will be performed for the group of participants with any post-randomization carotid ultrasound and for the adherent participants (>80% compliance with estrogen therapy).

CAC and CCTA outcomes obtained at the end-of-study (secondary trial endpoints) will be compared between treatment groups: 1) primary CCTA measures – total stenosis score and total plaque score; and, 2) secondary CCTA measures -- number of coronary artery segments with calcified, non-calcified and mixed plaque. CAC measures will include presence of any CAC (dichotomous variable) and CAC score. General linear models (GLM) will be used, specifying these CAC and CCTA measures as dependent variables. The 2 randomization stratification variables (type of menopause and dichotomous baseline CIMT) will be included as covariates. To account for the fact that the end-of-study visit will differ across participants, indicator variables for the study visit at which the CAC and CCTA measures were obtained will also be included as covariates. The primary independent variables of interest will be indicator variables for each of the study design factors, testing for differences in the end-of-study CAC and CCTA measure by treatment group and menopause stratum. A treatment-by-menopause stratum interaction will test whether the treatment group differences differ by time-since-menopause. Treatment group comparisons will be performed for all participants who have the CAC and/or CCTA end points and for the estradiol adherent (>80% compliant) participants.

Safety analysis and evaluation of adverse events will be performed on all randomized participants using exact methods, comparing events among the four study groups [early postmenopausal-estradiol treated; early postmenopausal-placebo treated; late postmenopausalestradiol treated; late postmenopausal-placebo treated]) since the primary question is whether any given group shows an elevated risk for adverse events. The following major clinical events will be evaluated and compared: 1) cardiovascular events, including fatal/nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), silent MI and sudden death, hospitalization for unstable angina and coronary revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty); 2) stroke; 3) venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism); 4) cancer (breast, uterine, ovarian, gastrointestinal, lung); 5) bone fractures; and, 6) all-cause mortality and noncoronary mortality.

ELITE was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California. All participants provided written informed consent before trial-related procedures were conducted. Participant safety and trial conduct were overseen by an External Data Safety Monitoring Board appointed by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health with expertise in women's health, menopausal health, hormone replacement therapy, cardiovascular disease, clinical trials and biostatistics.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Screening

Recruitment for ELITE commenced in May 2005. The first participant was randomized on July 13, 2005; the last participant was randomized on September 30, 2008. A total of 643 participants were randomized. The original sample size estimates required randomization of 504 participants. Since the response and recruitment to ELITE was large, it was decided to randomize a higher number of participants to the trial, in particular women in the late postmenopausal group since previous HT use was high in this group, and to compensate for any higher than anticipated dropout rate in this older group.

To obtain the 643 participants, 2166 candidates were telephone prescreened with a series of questions from a standard interview form. Of these 2166 telephone prescreened candidates, 1271 were ineligible. The remaining 895 candidates were further screened during a clinic visit from which the 643 participants were randomized. In total, 1523 (70%) candidates were ineligible or refused enrollment. The primary reasons for ineligibility or refusal included: current HT (171 women), 6-9 years postmenopausal (142 women), clinical signs or symptoms of CVD (81 women), diabetic or serum glucose >140 mg/dl (21 women), history of breast cancer (37 women), and not postmenopausal by trial criteria (104 women).

Baseline Results

Table 1 contrasts demographic factors and the results of the baseline examinations between the <6 years-since-menopause and >10 years-since-menopause strata. In the early postmenopausal stratum, participant mean age was 55.4 years and the median time-from-menopause was 3.5 years. In the late postmenopausal stratum, participant mean age was 65.4 years and the median time-from-menopause was 14.3 years. Overall, 32% of the women were from a minority racial or ethnic group and 99% of the participants had a high school or greater education. Smoking history was similar between strata; 3.4% of the participants were active smokers and 37% were former smokers. As expected, hot flashes were more common in the early postmenopausal group relative to the late postmenopausal group. A major difference between strata was that more women in the late postmenopausal group previously used HT and were currently using antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications than the women in the early postmenopausal group. More women in the late postmenopausal group underwent surgical menopause than the women in the early postmenopausal group (16.1% versus 3.3%, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics at baseline

| Characteristic | <6 Years-Since-Menopause (n=271) | ≥10 Years-Since-Menopause (n=372) | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 55.4 (4.1)2 | 65.4 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Median time since menopause, years (269,344) | 3.5 (1.9,5.0)3 | 14.3 (11.5,18.7) | <0.001 |

| Race or ethnicity | 0.03 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 174 (64.2%) | 266 (71.5%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 24 (8.9%) | 36 (9.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 41 (15.1%) | 49 (13.2%) | |

| Asian | 32 (11.8%) | 21 (5.7%) | |

| Education | 0.05 | ||

| College graduate | 195 (72.0%) | 233 (62.6%) | |

| High school or some college | 75 (27.7%) | 137 (36.8%) | |

| Less than high school | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Smoking History | 0.2 | ||

| Current | 11 (4.1%) | 11 (3.0%) | |

| Former | 89 (32.8%) | 147 (39.5%) | |

| Never | 171 (63.1%) | 214 (57.5%) | |

| Moderate or vigorous physical activity, hours during past week4 | 7.0 (8.4) | 5.5 (6.2) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol consumption, weekly estimate | 0.6 | ||

| None | 135 (49.8%) | 194 (52.2%) | |

| >0 to 1 unit (15 g)/d | 105 (38.8%) | 127 (34.1%) | |

| ≥1 to 2 units (30 g)/d | 23 (8.5%) | 39 (10.5%) | |

| >2 units (>30 g)/d | 8 (3.0%) | 12 (3.2%) | |

| Type of menopause | <0.001 | ||

| Natural | 262 (96.7%) | 312 (83.9%) | |

| Surgical | 9 (3.3%) | 60 (16.1%) | |

| Hot flashes, any within previous month5 (243, 324) | 173 (71.2%) | 157 (48.5%) | <0.001 |

| Mean number per day for women with any hot flashes | |||

| Mild | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.3 |

| Moderate | 1.1 (2.0) | 1.2 (2.0) | 0.8 |

| Severe | 0.62 (2.4) | 0.55 (1.6) | 0.7 |

| Past use of hormone therapy | 138 (50.9%) | 321 (86.3%) | <0.001 |

| Current hypertension medications | 50 (18.5%) | 107 (28.8%) | 0.003 |

| Current lipid-lowering medications | 40 (14.8%) | 88 (23.7%) | 0.005 |

Statistical tests utilized the student two-sample t-test for continuous variables, chi-square test for discrete variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for median time-since-menopause.

Mean (SD)

Median (interquartile range)

Hours of moderate or vigorous physical activity (3 or more standard metabolic equivalents) during the past 7 days

By flushing diaries

Table 2 contrasts clinical, laboratory and CIMT variables between years-since-menopause strata. The average CIMT was greater in the women in the late postmenopausal stratum than the women in the early postmenopausal stratum, 0.787 versus 0.748 mm, respectively. The average baseline systolic blood pressure was slightly greater and the average diastolic blood pressure was slightly lower in the women in the late postmenopausal stratum relative to the women in the early postmenopausal stratum. These average blood pressure differences between the women in the 2 strata likely reflect the greater baseline use of anti-hypertension medications by the women in the late postmenopausal stratum relative to the women in the early postmenopausal stratum, 28.8% versus 18.5%, respectively (Table 1). The slightly lower average baseline fasting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in the women in the late postmenopausal stratum relative to the women in the early postmenopausal stratum, as well as the equivalence in baseline fasting plasma cholesterol and triglycerides between strata (Table 2) is likely a reflection of the greater baseline use of lipid-lowering medications (the majority (96%) of which were from the statin class) by the women in the late postmenopausal stratum relative to the women in the early postmenopausal stratum, 23.7% versus 14.8%, respectively (Table 1). Although the hemoglobin A1c value was slightly lower among the women randomized to the early postmenopausal stratum relative to the women randomized to the late postmenopausal stratum, the fasting serum glucose level and body mass index were equivalent between strata (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics at baseline1

| Variable | <6 Years-Since-Menopause (n=271) | ≥10 Years-Since-Menopause (n=372) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid artery intima-media thickness, mm | 0.748 (0.095) | 0.787 (0.109) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.2 (5.4) | 27.4 (5.4) | 0.7 |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 65.5 (5.1) | 66.1 (5.2) | 0.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 116.8 (12.9) | 118.7 (11.9) | 0.06 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 76.1 (7.1) | 74.3 (7.0) | 0.001 |

| Serum lipids | |||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 139.4 (32.1) | 134.3 (30.8) | 0.04 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 64.4 (16.0) | 67.1 (18.6) | 0.06 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 224.8 (33.9) | 223.0 (33.4) | 0.5 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 105.1 (53.7) | 108.0 (55.7) | 0.5 |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.0) | 0.07 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 95.5 (10.4) | 94.5 (10.2) | 0.2 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % (269,369) | 5.5 (0.5) | 5.7 (0.4) | 0.002 |

| Serum concentrations, median (IQR) | |||

| Total estradiol, pg/mL (271,372) | 8.0 (5.8,11.4) | 7.7 (5.8,10.5) | 0.2 |

| Free estradiol, pg/mL (268,370) | 0.20 (0.14,0.31) | 0.18 (0.13,0.26) | 0.04 |

| Estrone, pg/ml (269,372) | 29.1 (22.7,38.1) | 27.7 (20.2, 37.1) | 0.08 |

| Progesterone, ng/mL (271,370) | 0.2 (<0.2,0.3) | 0.2 (<0.2,0.3) | 0.1 |

| Total testosterone, ng/dL (269,372) | 20.5 (15.5,27.9) | 21.6 (14.1,30.6) | 0.4 |

| Free testosterone, pg/dL (268,370) | 3.8 (2.9,5.5) | 3.9 (2.8,5.7) | 0.9 |

| Sex hormone binding globulin, nmol/L (268,370) | 46.1 (32.5,61.1) | 51.1 (37.7,66.9) | 0.01 |

All variables are summarized as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated. Comparison of means between postmenopausal strata utilized the student two-sample t-test; comparison of medians utilized the Wilcoxon rank sum test

LDL=low-density lipoprotein

HDL=high-density lipoprotein

IQR=Inter-quartile range

Table 3 shows the age- and race-adjusted linear associations of CIMT with baseline characteristics according to postmenopausal strata. Mean (SE) CIMT increased by 0.026 (0.003) mm per 5 years of age (p<0.001). As expected, cardiovascular risk factors of blood pressure and body mass index (BMI) were positively associated with CIMT in both strata. Mean (SE) CIMT increased by 0.002 (0.0004) mm per mmHg of systolic blood pressure in the early and by 0.002 (0.0005) mm per mmHg of systolic blood pressure in the late postmenopausal stratum and by 0.002 (0.0008) mm per mmHg of diastolic blood pressure in the early and by 0.002 (0.0008) mm per mmHg of diastolic blood pressure in the late postmenopausal stratum. Mean (SE) CIMT increased by 0.002 (0.001) mm per kg/m2 BMI in the early and by 0.003 (0.001) mm per kg/m2 BMI in the late postmenopausal stratum. Type of menopause (surgical versus natural), LDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol (TC)/HDL-C ratio, HDL-C (inverse), total testosterone (inverse) and SHBG (inverse) were associated with CIMT in the early postmenopausal stratum but not in the late postmenopausal stratum, although the interaction between strata for these variables was not statistically significant. In the early postmenopausal stratum, mean (SE) CIMT increased by 0.073 (0.030) mm for surgical versus natural menopause, 0.0004 (0.0002) mm per mg/dl of LDL-C and by 0.066 (0.028) mm per mg/dl of triglycerides and by 0.018 (0.005) mm per TC/HDL-C ratio; mean CIMT decreased by 0.001 (0.0003) mm per mg/dl of HDL-C, by 0.054 (0.027) mm per ng/dl of total testosterone and by 0.082 (0.027) mm per nmol/L of SHBG. CIMT associations with pulse rate and the serum levels of total estradiol differed across strata (interaction p-value = 0.02). Serum total estradiol was negatively associated with CIMT (mean (SE) CIMT decrease of 0.032 (0.019) mm per pg/ml of total estradiol, p = 0.09) among the women randomized to the early postmenopausal stratum but not among the women randomized to the late postmenopausal stratum. A higher pulse rate was positively associated with CIMT in the early postmenopausal stratum (mean CIMT increase by 0.003 (0.001) mm per beats/min, p=0.002) but not in the late postmenopausal stratum.

Table 3.

Baseline associations with carotid artery intima-media thickness1

| Characteristic | <6 Years-Since-Menopause (n=271) | ≥10 Years-Since-Menopause (n=372) | P-value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | p-value | Beta (SE) | p-value | ||

| Education | |||||

| College graduate | Ref | 0.9 | Ref | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| High school or some college | −0.003 (0.012) | −0.007 (0.011) | |||

| Less than high school | −0.011 (0.089) | 0.080 (0.075) | |||

| Current smoking | −0.007 (0.027) | 0.8 | 0.003 (0.032) | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Moderate or vigorous physical activity2 | |||||

| None | Ref | 0.4 | Ref | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 0.1 to 2.9 hours/week | 0.033 (0.021) | −0.030 (0.019) | |||

| 3.0 to 6.9 hours/week | 0.014 (0.021) | −0.023 (0.019) | |||

| 7.0+ hours/week | 0.020 (0.021) | −0.008 (0.019) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| None | Ref | 0.9 | Ref | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| >0 to 1 unit (15 g)/d | −0.006 (0.12) | −0.023 (0.012) | |||

| >1 to 2 units (30 g)/d | 0.003 (0.020) | 0.007 (0.018) | |||

| >2 units (>30 g)/d | −0.021 (0.032) | −0.024 (0.031) | |||

| Type of menopause | |||||

| Natural | Ref | Ref | 0.06 | ||

| Surgical | 0.073 (0.030) | 0.02 | −0.011 (0.015) | 0.5 | |

| Hot flashes, any within previous month3 | 0.0006 (0.013) | 0.9 | −0.002 (0.012) | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Past use of hormone therapy | −0.007 (0.011) | 0.5 | −0.026 (0.016) | 0.09 | 0.3 |

| Current hypertension medications | 0.005 (0.014) | 0.7 | 0.004 (0.012) | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Current lipid-lowering medications | 0.017 (0.015) | 0.3 | 0.0003 (0.013) | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.02 | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.007 | 0.4 |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.002 | −0.0003 (0.001) | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.002 (0.0004) | <.001 | 0.002 (0.0005) | <.001 | 0.7 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.002 (0.0008) | 0.02 | 0.002 (0.0008) | 0.05 | 0.8 |

| Serum lipids | |||||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 0.0004 (0.0002) | 0.02 | 0.0003 (0.0002) | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | −0.001 (0.0003) | 0.005 | −0.0004 (0.0003) | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.1 | 0.0001 (0.0002) | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl4 | 0.066 (0.028) | 0.02 | 0.0009 (0.030) | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio | 0.018 (0.005) | <0.001 | 0.010 (0.005) | 0.06 | 0.4 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 0.0006 (0.0005) | 0.2 | 0.0007 (0.0005) | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % (269,369) | 0.006 (0.011) | 0.6 | −0.010 (0.014) | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Total estradiol, pg/ml (271,372)4 | −0.032 (0.019) | 0.09 | 0.037 (0.026) | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Free estradiol, pg/ml (268,370)4 | −0.014 (0.018) | 0.4 | 0.032 (0.023) | 0.2 | 0.06 |

| Estrone, pg/ml (269,372)4 | −0.039 (0.030) | 0.2 | 0.004 (0.030) | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Progesterone, ng/ml (271,370) | |||||

| < 0.2 | Ref | 0.9 | Ref | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| 0.2 | 0.007 (0.015) | 0.013 (0.014) | |||

| 0.3 | 0.002 (0.015) | 0.0007 (0.016) | |||

| >0.3 | 0.003 (0.016) | 0.021 (0.016) | |||

| Total testosterone, ng/dl (269,372)4 | −0.054 (0.027) | 0.05 | 0.0008 (0.023) | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Free testosterone, ng/dl (268,370)4 | −0.014 (0.026) | 0.6 | 0.009 (0.023) | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Sex hormone binding globulin, nmol/L (268,370)4 | −0.082 (0.027) | 0.002 | −0.010 (0.028) | 0.7 | 0.1 |

Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted for each variable, adjusting for age and race. For categorical variables, Beta = mean difference in carotid artery intima-media thickness from specified referent group. For continuous variables, Beta = mean difference in carotid artery intima-media thickness per unit change of the relevant variable.

Hours of moderate or vigorous physical activity (3 or more standard metabolic equivalents) during the past 7 days

By flushing diaries

Log transformed

DISCUSSION

Results of the recruitment, screening and randomization phase of ELITE indicate that the design and implementation produced baseline conditions well-suited for a randomized controlled trial for the test of the timing hypothesis of HT on vascular disease and cognition. By design, there is excellent separation without overlap in the time from menopause between the group of women <6 years-since-menopause (median, 3.5 years) and >10 years-since-menopause (median, 14.3 years). This outcome provides an optimal setting in which we will be able to determine the effects of HT on atherosclerosis progression, CAD and cognitive change in strata of women with characteristics similar to those described in key studies. The early postmenopausal group is representative of postmenopausal women initiating HT in clinical practice near the time of menopause. Demographic and health risk factors are similar to those in most observational studies of HT use (21,22) and in the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS) randomized trial (23). The late postmenopausal group is more comparable to the entire cohort of women in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), in which participants were on average 64 years old and 12 years-since-menopause when randomized (1). Baseline CVD risk factors across postmenopausal strata such as smoking, BMI, blood pressure, lipids, glucose and hemoglobin A1c are similar while the baseline CIMT value is lower in the early postmenopausal group relative to the late postmenopausal group. Baseline usage of lipid-lowering and anti-hypertensive medications was greater in the late postmenopausal group than in the early postmenopausal group.

Although traditional and expected risk factor associations with CIMT (age, blood pressure and BMI) are present at baseline in both the <6 and >10 years-since-menopause strata, several important associations evident in the early but not in the late postmenopausal group may have relevance to the timing hypothesis and may play a role in the responsiveness of atherosclerosis progression to HT. Of these differences, perhaps the most important are the significant positive LDL-C and inverse HDL-C and SHBG associations with baseline CIMT in the early postmenopausal group. We have previously shown that the LDL-C lowering and HDL-C raising effects of HT account for 30% of the effect of randomized HT in reducing atherosclerosis progression (24). The highly significant inverse association of SHBG with CIMT in the early postmenopausal group may be of particular importance, as we have previously shown that the HT-related reduction in atherosclerosis progression occurs in women with an increase in SHBG in response to HT (25). The significant interaction across postmenopausal strata for total serum estradiol levels and CIMT appears consistent with the timing hypothesis. Although not statistically significant, the inverse association of total serum estradiol levels (in the relatively restricted range of postmenopausal levels) with CIMT in the early postmenopausal group supports our prediction that raising estradiol levels may decrease progression of atherosclerosis in this group of women. In the late postmenopausal group, there is no association of total serum estradiol levels with CIMT suggesting that raising estradiol levels may have no effect on atherosclerosis progression in this group of women. Whether these differential risk factor associations with CIMT at baseline according to strata play a role in determining whether HT reduces atherosclerosis progression in women who are <6 years-since-menopause relative to women who are >10 years-since-menopause remains to be determined. Although the strata are sufficiently separated according to time-since-menopause, certain baseline factors could obscure our results and the timing hypothesis for this trial. One possible variable is age; age and time-since-menopause tend to co-vary and it has not been determined which variable may be a stronger factor in determining the potential responsiveness of atherosclerosis progression to HT. Although there is a baseline mean 10-year difference in age between postmenopausal strata, there is substantial overlap in age across strata.

With the beneficial effects of HT in reducing the progression of atherosclerosis in EPAT reported in 2001, we hypothesized that intervention early in the atherosclerosis process at the start of menopause may be the key to cardiovascular disease prevention with HT (5). This led to the hypothesis that HT may be more effective as primary prevention when initiated in the early stages of atherosclerosis rather than as secondary prevention when atherosclerosis is established (6). In other words, HT may be effective in the prevention but not in the treatment of vascular disease (6). With publication of EPAT's sister study WELL-HART, where the effect of HT on established atherosclerosis was null, we concluded that the difference in outcomes between the two trials (EPAT and WELL-HART) may have resulted from the timing of the intervention relative to the stage of atherosclerosis as measured by the different imaging methods used in these trials (6) (carotid artery wall thickness in EPAT as a measure of early, asymptomatic, subclinical atherosclerosis and quantitative coronary angiography in WELL-HART used to evaluate late-stage, symptomatic atherosclerosis) (5,6). In support of these human trial findings is an accumulating literature from animal studies showing that estrogen has little effect in reversing atherosclerosis once it is established, whereas it significantly reduces the extent of atherosclerosis if therapy is initiated at an early stage of atherosclerosis development (7-9).

Since 2001, there has been a large accumulation of data from randomized trials strongly supporting the timing hypothesis (Table 4) suggesting that women respond differentially to HT according to timing of HT initiation relative to age and/or time-since-menopause, particularly with regard to coronary heart disease (CHD) outcomes (1). Meta-analyses of the cumulated data show that the effect of HT on CHD and total mortality is null when HT is initiated in women >60 years of age and/or >10 years-since-menopause whereas, in women who initiate HT when <60 years of age and/or <10 years-since-menopause, there is a 32% reduction in CHD and 39% reduction in total mortality relative to placebo (26-29). The magnitude of CHD and total mortality reduction for women <60 years of age and/or <10 years-since-menopause when randomized to HT is similar to observational studies of populations of women who initiated HT at or near the time of menopause (21,22).

Table 4.

Coronary heart disease and total mortality in women initiating hormone or selective estrogen receptor modifier (SERM) therapy before age 60 years and/or within 10 years-since-menopause

| Studies | Age, years | Time-Since-Menopause | Hormone Therapy | Coronary Heart Disease % Reduction (Risk Ratio; 95% Confidence Interval) | Total Mortality % Reduction (Risk Ratio; 95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis26 | <60 | <10 yrs | ↓ 32% (0.68; 0.48-0.96) | ||

| Meta-analysis27 | 54 | ↓ 39% (0.61; 0.39-0.95) | |||

| Bayesian meta-analysis28 | 55 | ↓ 27% (0.73; 0.52-0.96) | |||

| Observational studies21,22 | 30-55 | <5 yrs | ↓ 30-50% | ↓ 20-60% | |

| DOPS, 10 year23 | 50 | 7 mo | E2 alone and E2 + NETA sequential | ↓ 52% (0.48; 0.27-0.89) | ↓ 43% (0.57; 0.30-1.08) |

| DOPS, 16 year23 | ↓ 39% (0.61; 0.39-0.94) | ↓ 34% (0.66; 0.41-1.08) | |||

| WHI-E, 11 year30 | <60 | CEE alone | ↓ 41% (0.59; 0.38-0.90) | ↓ 27% (0.73; 0.53-1.00) | |

| WHI-E10 | <10 yrs | CEE alone | ↓ 52% (0.48; 0.20-1.17) | ↓ 35% (0.65; 0.33-1.29) | |

| WHI-E+P10 | <10 yrs | CEE+MPA continuous combined | ↓ 12% (0.88; 0.54-1.43) | ↓ 19% (0.81; 0.52-1.24) | |

| WHI-E10 | <60 | CEE alone | ↓ 37% (0.63; 0.36-1.09) | ↓ 29% (0.71; 0.46-1.11) | |

| WHI-E+P10 | <60 | CEE+MPA continuous combined | ↑ 29% (1.29; 0.79-2.12) | ↓ 31% (0.69; 0.44-1.07) | |

| RUTH32 | <60 | Raloxifene | ↓ 41% (0.59; 0.41-0.83) |

DOPS = Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study

WHI-E = Women's Health Initiative-estrogen alone trial

WHI-E+P = Women's Health Initiative-estrogen + progestin continuous combined trial

RUTH = Raloxifene Use for the Heart trial

E2 = estradiol

NETA = Norethisterone acetate

CEE = Conjugated equine estrogens

MPA = Medroxyprogesterone acetate

In a more recent randomized trial with a PROBE (prospectively, randomized, open with blinded endpoint evaluation) design, the DOPS provides data for long-term use of oral estradiol alone and estradiol with sequential norethisterone acetate when initiated in healthy young perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women (23). DOPS included 1,006 postmenopausal women who were on average 50 years old and 7 months postmenopausal. The composite primary trial end point of mortality, MI or heart failure was significantly reduced by 52% (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.27-0.89) and by 39% (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.39-0.94) after 10 years of randomized treatment and 16 years of total follow-up (10 years of randomized treatment and 6 years of post-intervention follow-up), respectively. Total mortality was reduced by 43% (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.30-1.08) after 10 years of randomized treatment and by 34% (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.41-1.08) after 16 years of total follow-up. Similar to DOPS are the 11-year WHI trial follow-up (7 years of randomized treatment and 4 years of post-intervention follow-up) data. In WHI, women without a uterus who were 50-59 years of age when randomized to conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) had significant reductions relative to placebo in CHD by 41% (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90), total MI by 46% (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.34-0.86) and total mortality by 27% (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.53-1.00) (30). These treatment outcomes significantly differed by age, being better among younger postmenopausal women and worse among older postmenopausal women (p-value for interaction, p=0.05 for CHD, p=0.007 for myocardial infraction and p=0.04 for total mortality, respectively). Findings, thus indicate that the CEE effect on these outcomes differed by age of HT initiation (30).

Other evidence that HT initiation in young postmenopausal women in close proximity to menopause may reduce CHD derives from 1,064 women who participated in the WHI CAC sub-study in which 50-59 year old women who were randomized to CEE had significantly less CAC at year 7 of the trial compared with women randomized to placebo (31). There was no older age group in this sub-study to evaluate whether HT influenced CAC when initiated in women >60 years old. Results of ELITE will provide the necessary data to determine the effect of HT on CAC in younger postmenopausal women with HT initiation in close proximity to menopause relative to older postmenopausal women with HT initiation distant from menopause. In addition, for the first time, the effects of HT on CAD will be determined with CCTA in an asymptomatic population of women under the same circumstances in ELITE. The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) will provide data for low-dose HT on CIMT and CAC in a select group of low-risk women (CAC <50 at baseline) randomized within 3 years of menopause.

In addition to mammalian hormones, other agents that bind to the estrogen receptor exert similar CHD beneficial effects in young postmenopausal women as HT. Among women <60 years of age when randomized to raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, CHD was significantly reduced by 41% (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41-0.83) relative to placebo (32). Women older than 60 years of age showed no benefit from raloxifene. In the Women's Isoflavone Soy Health (WISH) study, a randomized controlled trial in which the effects of high-dose isoflavone soy protein supplementation (plant estrogens that preferentially bind to estrogen receptor-beta) on the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis were determined, women who were randomized within 5 years of menopause to isoflavone soy protein supplementation had a significant reduction in progression of subclinical atherosclerosis relative to placebo whereas isoflavone supplementation among women more than 5 years beyond menopause when randomized had no significant effect (33).

CONCLUSION

The randomized trial data show that HT reduces the incidence of CHD and total mortality in young postmenopausal women (<60 years old) who initiate HT in close proximity to menopause (<10 years-since-menopause) (Table 4) (1). These findings are consistent with reductions in CHD and total mortality reported from observational studies, where the majority of women initiated HT within 6 years of menopause (21,22). Although the cumulative literature is more than suggestive of this conclusion, no clinical trial has specifically tested the timing hypothesis with regard to CHD or cognitive outcomes. In this respect, ELITE is both timely and unique. Over the past decade, the timing hypothesis pertaining to CHD has matured into a well-supported hypothesis awaiting more definitive study. For cognitive decline in the absence of dementia, the timing hypothesis remains of critical concern (34), although supportive data are less fully developed than for CHD. As post-randomization baseline data indicate, ELITE is well-positioned to test the timing hypothesis of HT in relation to atherosclerosis progression, CAD and cognitive change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-AG024154-01-05, R01-AG024154-06-08 and R01-AG024154-S2 from the National Institute on Aging. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Watson Laboratories, Inc. and Abbott Laboratories provided the hormone products gratis.

Footnotes

ELITE Research Group Members

Study Chairman: Howard N. Hodis MD*; Clinical Center Staff: Liny Zurbrugg RN (Clinic Coordinator), Esther Bhimani MA, Martha Charlson RD, Irma Flores MA, Martha Huerta, Thelma LaBree MA, Sonia Lavender MA, Violetta McElreath RN, Janie Teran, Philip Zurbrugg; Ultrasound Image Acquisition and Processing Laboratory: Robert H. Selzer MS* (Director), Yanjie Li MD (Technical Director), Mei Feng MD, Lora Whitfield-Maxwell RN, Ming Yan MD, PhD; Data Coordinating Center: Wendy J. Mack PhD* (Director), Stanley P. Azen PhD*, Farzana Choudhury MS, Carlos Carballo, Laurie Dustin MS, Adrian Herbert, Naoko Kono MPH, George Martinez, Olga Morales; Atherosclerosis Research Unit Core Lipid/Lipoprotein Laboratory: Juliana Hwang-Levine PharmD* (Director), Gail Izumi CLS, Arletta Ramirez CLS, Luci Rodriguez; Gynecology and Mammography: Donna Shoupe MD*, Juan C. Felix MD, Pulin Sheth, Mary Yamashita; USC Endocrinology Laboratory: Carole Spencer; Neurocognition: Victor W. Henderson MD*, Carol A. McCleary, PhD, Jan A. St. John MPH; Kaiser Permanente Medical Center Recruitment Site: Malcolm G. Munro, MD; Cardiac Computed Tomography Core Center: Matthew J. Budoff MD (Director), Lily Honoris MD, Chris Dailing, Sivi Carson; Data Safety Monitoring Board: Leon Speroff MD (Chairman), Robert Knopp MD (deceased), Richard Karas MD, Joan Hilton PhD; Judy Hannah (NIA ex-officio). *Primary trial investigators

Frank Z. Stanczyk is on the advisory board for Merck & Company and Agile Therapeutics. He has no conflicts of interest. Matthew J. Budoff receives grant support from General Electric. He has no conflicts of interest. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

Supplemental Digital Content: Word text providing details of the carotid artery ultrasound and coronary computerized tomography procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. The timing hypothesis and hormone replacement therapy: a paradigm shift in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women. Part 1: comparison of therapeutic efficacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1005–10. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. The timing hypothesis and hormone replacement therapy: a paradigm shift in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women. Part 2: comparative risks. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1011–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson VW. Estrogen-containing hormone therapy and Alzheimer's disease risk: understanding discrepant inferences from observational and experimental research. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1031–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLennan AH, Henderson VW, Paine BJ, Mathias J, Ramsay EN, Ryan P, et al. Hormone therapy, timing of initiation, and cognition in women aged older than 60 years: the REMEMBER pilot study. Menopause. 2006;13:28–36. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000191204.38664.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, Shoupe D, Sevanian A, Mahrer PR, et al. Estrogen in the prevention of atherosclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:939–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, Shoupe D, Mahrer PR, Faxon DP, et al. Hormone therapy and progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. N Eng J Med. 2003;349:535–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarkson TB. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2007;14:373–84. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31803c764d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenfeld ME, Kauser K, Martin-McNulty B, Polinsky P, Schwartz SM, Rubanyi GM. Estrogen inhibits the initiation of fatty streaks throughout the vasculature but does not inhibit intra-plaque hemorrhage and the progression of established lesions in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:251–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarhouni K, Guihot AL, Vessieres E, Toutain B, Procaccio V, Grimaud L, et al. Determinants of flow-mediated outward remodeling in female rodents: respective roles of age, estrogens, and timing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1281–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu LL, Barad D, Barnabei VM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297:1465–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, McCLeary CA, Stanczyk FZ, Karim R, et al. Cognition, mood, and physiological concentrations of sex hormones in the early and late postmenopause. PNAS. 2013;110:20290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312353110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Probst-Hensh NM, Ingles SA, Diep AT, Halle RW, Stanczyk FZ, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE. Aromatase and breast cancer susceptibility. Endorine-Related Cancer. 6:165–73. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060165. 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Sacks DB. National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) Steering Committee. Status of hemoglobin A1c measurement and goals for improvement: from chaos to order for improving diabetes care. Clin Chem. 2011;57:205–14. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter MS. The womens's health questionnaire (WHQ): frequently asked questions (FAQ). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2013;1:41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, Mahrer PR, Sevanian A, Liu CR, et al. Alpha tocopherol supplementation in healthy individuals reduces low-density lipoprotein oxidation but not atherosclerosis: the Vitamin E Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (VEAPS). Circulation. 2002;106:1453–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029092.99946.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selzer RH, Hodis HN, Kwong-Fu H, Mack WJ, Lee PL, Liu CR, et al. Evaluation of computerized edge tracking for quantifying intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery from B-mode ultrasound images. Atherosclerosis. 1994;111:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selzer RH, Mack WJ, Lee PL, Kwong-Fu H, Hodis HN. Improved common carotid elasticity and intima-media thickness measurement from computer analysis of sequential ultrasound frames. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:185–93. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, Kono N, McCLeary CA, Franke AA, et al. Long-term soy isoflavone supplementation and cognition in women: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2012;78:1841–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr., et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grodstein F, Stampfer M. The epidemiology of coronary heart disease and estrogen replacement in postmenopausal women. Prog Cardiol Dis. 1995;38:199–210. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(95)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grodstein F, Stampfer M. Estrogen for women at varying risk of coronary disease. Maturitas. 1998;30:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, Stilgren L, Eiken P, Mosekilde L, et al. Effect of hormone replacement treatment on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomized trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e6409. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karim R, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, Hwang J, Liu CR, Liu CH, et al. Determinants of the effect of estrogen on the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial. Menopause. 2005;12:366–73. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000153934.76086.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karim R, Hodis HN, Stanczyk FZ, Lobo RA, Mack WJ. Relationship between serum levels of sex hormones and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:131–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Greyber E, Salpeter EE. Coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:363–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Greyber E, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Mortality associated with hormone replacement therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;12:1016–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Liu H, Salpeter EE. The cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy in younger and older postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Johnson KC, Martin L, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1305–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, Carr JJ, Langer RD, Hsia J, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins P, Mosca L, Geiger MJ, Grady D, Kornitzer M, Amewou-Atisso MG, et al. Effects of the selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene on coronary outcomes in the raloxifene use for the heart trial: results of subgroup analyses by age and other factors. Circulation. 2009;119:922–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.817577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Kono N, Azen SP, Shoupe D, Hwang-Levine J, et al. Isoflavone soy protein supplementation and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2011;42:3168–75. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.620831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherwin BB. Estrogen therapy: is time of initiation critical for neuroprotection? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:620–7. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.