Abstract

In fission yeast, Sty1 and Gcn2 are important protein kinases regulating gene expression in response to amino acid starvation. The translation factor subunit eIF3e/Int6 promotes the Sty1-dependent response by increasing the abundance of Atf1, a transcription factor targeted by Sty1. While Gcn2 promotes expression of amino acid biosynthesis enzymes, the mechanism and function for Sty1 activation and Int6/eIF3e involvement during this nutrient stress is not understood. Here we show that mutants lacking sty1+ or gcn2+ display reduced viabilities during histidine depletion stress in a manner suppressible by the antioxidant, N-acetyl cysteine, suggesting that these protein kinases function to alleviate endogenous oxidative damage generated during nutrient starvation. Int6/eIF3e also promotes cell viability by a mechanism involving stimulation of the Sty1 response to oxidative damage. In further support of these observations, microarray data suggests that, during histidine starvation, int6Δ increases the duration of Sty1-activated gene expression linked to oxidative stress due to the initial attenuation of Sty1-dependent transcription. Moreover, loss of gcn2 induces the expression of a new set of genes not activated in wild-type cells starved for histidine. These genes encode heatshock proteins, redox enzymes and proteins involved in mitochondrial maintenance, in agreement with the idea that oxidative stress is imposed onto gcn2Δ cells. Furthermore, the early Sty1 activation promotes a rapid Gcn2 activation on histidine starvation. These results suggest that Gcn2, Sty1, and Int6/eIF3e are functionally integrated and cooperate to respond to oxidative stress that is generated during histidine starvation.

Translation initiation is an important target of stress responsive pathways regulated by various physiological and environmental signals. Reduced translation allows cells to conserve energy coincident with an altered programme of gene expression which leads to the production of proteins that have the capacity to ameliorate stress-induced damage 1. Genetic alteration of eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIFs) can disrupt the appropriate responses to physiological signals and stresses, which can alter the etiology and treatment of many diseases, including cancer 2.

One of the key factors contributing to the onset of disease processes is oxidative stress, resulting from changes in metabolic activities or environmental stress 3. Malignant tumorigenesis can involve the altered activities of eIF2α kinases (eIF2Ks), which is thought to provide cancer cells with increased resistance to nutritional and hypoxic stresses 4; 5. Activation of eIF2Ks not only represses global protein synthesis, but preferentially enhances translation of key transcription factors, such as ATF4. ATF4 triggers the transcription of stress-related genes as part of the integrated stress response (ISR) and is involved in alleviating oxidative stress and in controlling nutrient uptake and metabolism, as well as apoptosis 6; 7; 8. The eIF2Ks are conserved throughout eukaryotes. The unicellular model organism, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, encodes three of the conserved eIF2Ks, Gcn2, Hri1 and Hri2, each of which is implicated in the response to oxidative stress 9; 10. Similar to the mammalian ISR, eIF2K activation in S. pombe and another yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, promotes transcription of a common set of genes termed the general amino acid control response (GAAC) 11; 12.

In conjunction with eIF2Ks, evolutionarily conserved stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including S. pombe Sty1 (also known as Spc1 or Phh1), also respond to oxidative stress. Sty1 is activated via a conserved MAPK cascade, including the MAPK kinase (MAP2K) Wis1 and the MAP2K kinases (MAP3K) Wis4 and Win1 13. Sty1 activation then leads to the enhanced stability of the Atf1 transcription factor via mechanisms involving Atf1 phosphorylation and increased Atf1 activity via a phosphorylation-independent process 14; 15. As a consequence, oxidative stress triggers the expression of a group of genes termed the core environmental stress response (CESR), most of which are dependent upon the Sty1/Atf1 pathway 16.

We recently found that both Sty1 and Gcn2 protein kinases are required for the response of S. pombe to histidine starvation elicited by the drug 3-aminotriazole (3AT), and that Gcn2 facilitates increased transcription of genes encoding amino acid biosynthetic enzymes in response to the nutritional deficiency 12. While the Sty1 MAPK pathway has been linked to oxidative, osmotic and DNA-damaging conditions 16, activation of Sty1 in the response to histidine starvation was somewhat surprising, given that amino acid starvation is not thought to cause oxidative damage and that Sty1 does not facilitate transcription of amino acid biosynthetic genes 12.

Interestingly, the Sty1-dependent response during nutrient starvation is promoted by Int6/eIF3e 12, whose mammalian homologue is encoded by a frequent integration site of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) termed int-6 17. int-6 encodes the e-subunit of eIF3 18. Mammalian eIF3 is composed of 13 subunits (eIF3a-m), and serves as the scaffold for eIF2 and the cap binding protein, eIF4F, which assists binding of the 40S ribosome to mRNA 19. Although truncated forms of Int-6/eIF3e found in MMTV-integrated tumors are known to be oncogenic both in vitro 20; 21 and in vivo 22, the mechanism of tumorigenesis caused by Int-6 misregulation remains elusive. S. pombe encodes 11 of the 13 subunits found in mammalian eIF3 23; 24; 25. int6+ is not essential in fission yeast, but its loss (int6Δ) reduces translation initiation in yeast cultured in minimal media 12; 23. This finding is in agreement with the important roles of eIF3e in translation initiation in mammalian cells 26; 27. S. pombe Int6/eIF3e promotes the Sty1-dependent response at least in part by stimulating expression of atf1+ by translational or posttranslational process 12.

In this study, we explored the integration between the Sty1/Atf1 MAPK pathway and key translational regulators - eIF2Ks and Int6/eIF3e in the control of gene expression and cell viability during nutrient stress. Our results suggest that during histidine starvation, Sty1 and Gcn2 cooperate to alleviate endogenous oxidative damage, which might be generated by a change in the nutrient status. Furthermore, evidence is provided that Int6/eIF3e modulates the Sty1 response to oxidative damage. Our results support the model that alleviating oxidative damage during canonical nutritional stress is an important function of the integrated Sty1, Int6/eIF3e, and eIF2K stress response pathways. These findings provide insight into the cellular roles of eIF2Ks during nutrient deprivation, and provide clues to understanding the mechanism by which MMTV integration at the murine int-6 locus can contribute to tumorigenesis.

Results

Histidine starvation, as induced by 3AT, directly promotes Sty1-directed transcription

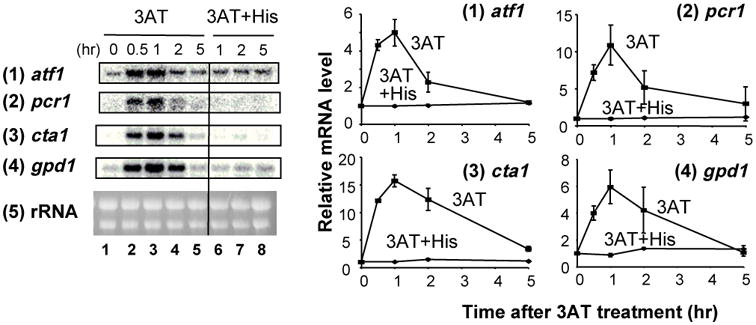

3AT is a potent inhibitor of the histidine biosynthesis enzyme, imidazoleglycerol-phosphate dehydratase (encoded by S. pombe His5), causing histidine starvation in an otherwise prototrophic strain. Because 3AT is also suggested to inhibit other enzymes, such as catalase 28, we wished to test if the CESR is induced specifically by histidine starvation. For this purpose, we treated cells with 3AT in the presence or absence of added histidine. We then measured accumulation of four representative CESR transcripts, atf1+, pcr1+, cta1+ and gpd1+ mRNAs by Northern blotting (Fig. 1). As described above, Atf1 is a basic leucine-zipper (bZIP) factor responsible for mediating many Sty1-dependent transcriptional events; Pcr1 is a second bZIP factor which forms heterodimers with Atf1 and is also required for the expression of a number of Sty1-dependent genes 14; 15; 29; 30; cta1+ encodes the major catalase activity induced by various Sty1-activating signals 16; and Gpd1 is a glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, producing glycerol in response to osmotic stress 31. The addition of histidine completely eliminated the accumulation of these four transcripts, which were induced with 30 mM 3AT in wild-type cells (Fig. 1). Together with our previous finding that 3AT sensitivity of the sty1 mutant is completely alleviated by addition of histidine 12, these results endorse the specific effect of 3AT on the His5 enzyme in this yeast, and further suggest that histidine starvation, rather than inhibition of catalase or other enzymes, directly promotes CESR transcription under 3AT-induced stress.

Fig. 1. Effect of histidine on 3AT-induced CESR transcription.

A wild-type strain (KAY641) was grown exponentially in the EMM-C-his medium and split into two cultures. One was starved for histidine by adding 30 mM 3AT (lanes 1-5) and the other was supplemented with 30 mM 3AT and 60 mM histidine simultaneously (lanes 6-8). Portions of the culture were withdrawn at indicated times and mRNA levels were analyzed by northern blot analysis using probes specific for genes listed to the left. EtBr-staining of rRNA was included as a loading control 12. Graphs to the right show the time course for the levels of indicated mRNAs compared to the value at time 0 as 1 (lanes 1), with bars indicating SD (n=2). In the graph for 3AT+His, error bars are smaller than the size of the symbols.

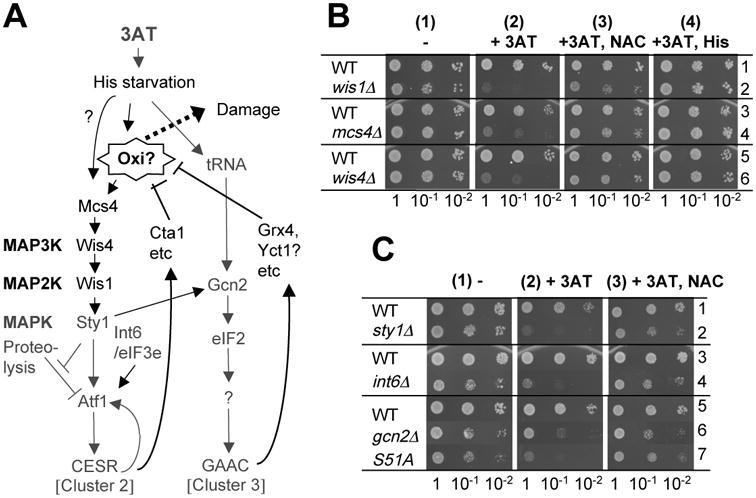

Sty1 MAPK cascade, Gcn2, and Int6/eIF3e appear to alleviate oxidative stress generated during 3AT-induced starvation

In order to gain insight into the mechanism whereby Sty1 is activated by 3AT-induced histidine starvation, we examined the involvement of other components of the Sty1 MAPK signaling pathway (see Fig. 2A), which were previously linked with oxidative stress. Thus, we tested the 3AT-sensitivity of mutant strains defective for Wis1 MAP2K, Wis4/Win1 MAP3K, Mpr1/Mcs4 phosphorelay proteins, Mak1/Mak2/Mak3 histidine kinases 13 and the glycolytic enzyme Tdh1 32 (Fig. 2B and TO and KA, unpublished data). Among these mutants, those deleted for mcs4+, wis1+ or wis4+ were 3AT-sensitive in a manner reversed by histidine (Fig. 2B). Therefore, a canonical MAPK cascade leading to Sty1 activation is required for survival upon 3AT exposure, as illustrated in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2. Genetic evidence that a canonical Sty1 pathway, Int6/eIF3e and Gcn2 specifically promote oxidative stress response during histidine starvation.

(A) Model of 3AT-induced Sty1 and Gcn2 pathways in fission yeast. 3AT-induced histidine (His) starvation activates not only the Gcn2-dependent pathway (cluster 3, right column) but also the Sty1-dependent pathway (cluster 2, left column). Here it is proposed that at least one of the Sty1 activating signals is endogenous oxidation (Oxi), which would cause cellular damage (Damage) if the products of both the pathways cannot antagonize the oxidative reagents (stopped bars towards Oxi?). This model was modified from the original model described in Ref. 12. Dark gray letters and lines indicate a part of the pathways suggested by previous studies 12. Black letters and lines indicate a part of the pathway suggested from this study. (B-C) Effect of NAC on the 3AT-sensitvity of different mutants. Cultures of the indicated mutants and their wild-type (WT) controls were diluted to A600=0.15, and 5 ml of this and 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto EMM plus adenine agar plates supplemented without (panels 1) or with 5 mM 3AT (panels 2), 5 mM 3AT and 20 mM NAC (panels 3), or 5 mM 3AT and 10 mM histidine (His) (panel 4 in A). However, for rows 5 and 6 in Fig. 2B, we used 8 mM 3AT, 40 mM NAC, and 16 mM histidine. Plates were incubated for 4 (panels 1 and 4) and 6-7 (panels 2 and 3) days. Here we used minimal medium without amino acid supplements to promote incorporation of NAC and histidine. Strains used in (B) are JP3 (row 1), JP260 (row 2), KAY793 (row 3), KAY794 (row 4), KAY456 (row 5), and KAY852 (row 6), whereas in (C), we used KAY641 (rows 1 and 3), KAY640 (row 2), KAY647 (row 4), WY764 (row 5), KAY406 (row 6), and JP436 (row 7) (Table 1).

Because a major function of the canonical Sty1 MAPK cascade is to ameliorate oxidative damage, we hypothesized that the 3AT-induced, Int6/eIF3e-assisted Sty1 pathway is also expressed to this end. In an effort to test this model, we used the antioxidant, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). As expected, NAC rescued the slow growth of the strains deleted for sty1+or int6+ in the presence of 3AT in a dilution assay (Fig. 2C, compare panels 2 and 3, rows 2 and 4). Likewise, NAC rescued the 3AT-sensitivity of the mutants deleted for mcs4+, wis1+ or wis4+ (Fig. 2B). We previously showed that sty1+ and int6+ do not simply increase expression of histidine biosynthesis enzymes 12; otherwise NAC would not rescue 3AT sensitivity of the cells deleted for these genes. Thus, the 3AT sensitivities of the sty1Δ and int6Δ cells, and most likely those of other Sty1 pathway mutants, could be due to a failure of these mutant strains to respond to endogenous oxidative stress that might accompany histidine starvation.

In light of these findings, we also examined if NAC rescues the 3AT sensitivity of gcn2Δ cells, and to our surprise, we found that it did, albeit partially (Fig. 2C, lane 6). This suggests that Gcn2 functions to ameliorate oxidative damage. In order to test if the sensitivity of gcn2Δ cells is due to a failure in Gcn2 phosphorylation of eIF2α, we tested the 3AT sensitivity of the mutant cells altering the eIF2α phosphorylation site, Ser-51, to alanine (sui2-S51A) 33. The sui2-S51A strain is also 3AT-sensitive in a manner suppressible by NAC (Fig. 2C). These findings suggest that phosphorylation of eIF2α by Gcn2 is also important for alleviating oxidative stress during amino acid starvation.

Sty1 MAPK suppresses cell death and genetic suppression during histidine starvation in a manner reversed by an antioxidant

While the major biological function of NAC is as an antioxidant, NAC or its cellular product, reduced glutathione, has other biological functions. To address if NAC rescues the 3AT sensitivity of tested mutants by ameliorating cellular (oxidative) damage, we examined whether 3AT directly reduces the viability of the mutant cells, and if so, whether NAC reverses this effect. For this purpose, we grew yeast in semi-exponential phase for several days by successive inoculation into fresh media in the presence or absence of 3AT (Fig. S1), and quantified cell viability at different times.

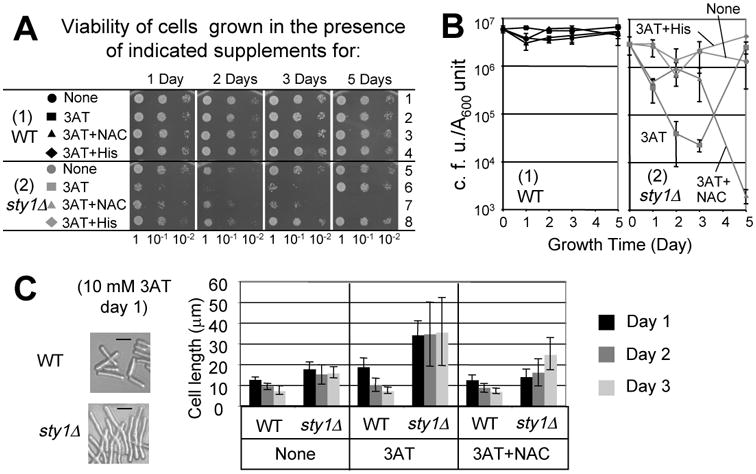

We first measured the survival of the wild-type and sty1Δ cells following culturing for 1 to 5 days in 10 mM 3AT medium supplemented with histidine or NAC. Following the culture period, the cells were spotted onto rich medium to measure cell viability (Fig. 3A). There was no significant loss of viability of the wild-type cells treated with 3AT for up to 5 days (Fig. 3A-B), even though 3AT substantially reduces the growth rate of these cells (Fig. S1). In contrast, only ∼1% of sty1Δ cells survived a two-day treatment with 3AT (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the reduced viability during this period was suppressed by the addition of histidine, emphasizing that starvation for this amino acid was central for the enhanced lethality accompanying the 3AT treatment of the sty1Δ strain. Interestingly, the viability of sty1Δ cells that was reduced after 2 days of starvation increased to ∼100% on day 5 (Fig. 3A). Illustrating this point, the sty1Δ cells that were recovered after 5 days of starvation grew faster on YES medium (Fig. 3A). This finding suggests that after 3 or more days of starvation, the sty1Δ culture generated genetic mutants resistant to 3AT (3ATR). Supporting this idea, a sensitivity assay using 3AT-containing plates confirmed that about 10% of the sty1Δ cells that were recovered following 2 days of starvation were 3ATR, whereas nearly 100 % of sty1Δ cells that survived after 3 and 5 days of starvation were 3ATR (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Sty1 MAPK suppresses stress-induced death and mutagenesis during histidine starvation.

(A) Viability assays in the presence of 10 mM 3AT. Fresh overnight cultures of KAY641 (wild-type, black symbols) and KAY640 (sty1Δ, gray symbols) were inoculated into ∼3 ml liquid EMM+Ade medium with 40 mM NAC, 20 mM histidine, and 10 mM 3AT, as indicated. The cultures were started at A600∼0.3 with constant agitation at 30°C, and the aliquots were periodically removed to measure the titer by spotting onto the YES agar plates, which were incubated at 30°C for 2 days, and photographed. Colonies formed on each spot was counted to determine the viability, as presented by colony forming units (CFU) per A600. If two or more serially diluted spots contained well-dispersed colonies, the CFU per A600 values obtained from each spot were averaged to determine the viability value for that condition. Three independent viability assays were performed. (B) Graphs show viability (CFU per A600 unit culture) of wild-type (panel 1) and sty1Δ (panel 2) cells exposed to starvation for the times indicated. Bars indicate SD (n = 3, except a single experiment was done with the control 3AT+His treatment). (C) Effect of 3AT and NAC on cell size. Photographs show the wild-type and sty1Δ cells under the designated growth condition, with bars indicating 10 μm. Portions of these cell cultures were withdrawn at indicated times (see legends to the right) and observed under a microscope after fixing with formaldehyde. The graph indicates the average sizes of 20 different cells in mm, which were measured with ImageJ software. The bars in the graph indicate the SD.

In an effort to examine if the reduced viability is due to oxidative stress, we tested the effect of the antioxidant, NAC. Its addition to the sty1Δ cells enhanced viability for up to 3 days of 3AT treatment (Fig. 3A). However, at day 5 there was reduced survival of the sty1Δ cells in the combined 3AT+NAC treatment (Fig. 3A). At this point the NAC addition to the 3AT liquid medium also suppressed the generation of 3ATR cells, which instead caused the extinction of the entire culture on day 5 (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that sty1+ function contributes to a significant delay in cell death induced by oxidative stress during histidine starvation. NAC can provide some protection to sty1Δ cells against 3AT exposure for up to 3 days, but this anti-oxidant is not sufficient for longer treatment periods. In this sense, this shorter-term protection comes with a price. The 3ATR revertants that accumulated in the sty1Δ cultures were absent when NAC was combined with 3AT in the medium (Fig. 3B).

sty1Δ cells were longer during the growth in the 10 mM 3AT medium (Fig. 3C), as observed under other stresses 34. Thus, the observed decrease in CFU per A600 unit culture measured in Fig. 3C was potentially due to increased mass per cell and as a consequence of plating fewer cells. However, this possibility was excluded by measuring the average size of wild type and sty1Δ cells. Within the first three days of starvation, the size of the sty1Δ cells was only 2- to 4-fold larger than that of wild-type cells in the 3AT medium, and NAC addition reduced the size of the sty1Δ cells only <2-fold at each growth time (Fig. 3C).

Together, these results suggest that 3AT-induced histidine starvation imposes oxidative stress, and sty1+ rescues the stress likely by expressing the CESR (Fig. 2A) (see Discussion also). In the absence of sty1+, the stress appears to damage the yeast cells, leading to reduced viability. The generation of 3ATR cells could be due to DNA mutations or epigenetic changes. While the mechanism of this observation requires further examination, it is consistent with the idea that the cells grown in the presence of 3AT experience some sort of damage to chromosomes (indicated as “Damage” in Fig. 2A). The fact that NAC rescues the reduced viability of sty1Δ cells for the first 3 days (Fig. 3A-B) suggests that the damage is due to oxidative stress, and more importantly, agrees with the idea that the major function of the Sty1 pathway, in this context, is to respond to oxidative stress.

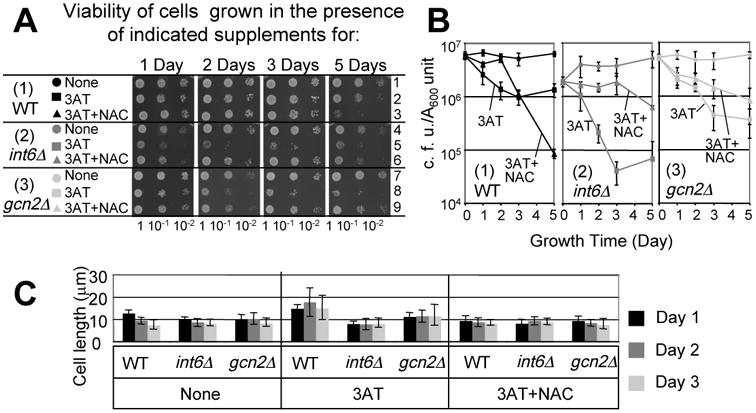

Int6/eIF3e and Gcn2 eIF2K also suppress cell death during histidine starvation

We next addressed whether Int6/eIF3e and Gcn2 suppress cell death during histidine starvation, as observed for Sty1. Initially we carried out the experiment using 10 mM 3AT in EMM medium, as performed previously (Fig. 3). However, the mutants deleted for int6+ or gcn2+ did not display a reduced viability even when incubated for up to 7 days (data not shown). Thus, we incubated the mutants in the medium containing 30 mM 3AT. Under these conditions, the wild-type yeast grew even more slowly than in the presence of 10 mM 3AT and after day 2, they almost stopped growing (Fig. S1B, panel 1). Coincidentally, the viability of wild-type cells dropped to ∼15% in the 3AT medium during this period (Fig. 4A-B, panels 1). In contrast, there was a significant reduction of viability of int6Δ cells (∼1% survival) after 3 days of 3AT exposure (Fig. 4A-B, panels 2). The viability of gcn2Δ cells also dropped more greatly (∼10% survival) than that for wild-type after 3(p=0.05, n=4) and 5 days (p=003, n=3) of 3AT exposure (Fig. 4A-B, panels 3). This minor effect is consistent with the partial suppression of 3AT sensitivity of gcn2Δ cells by NAC, as observed in the dilution assays (Fig. 2C). As with sty1Δ cells, NAC enhanced the viability of int6Δ and gcn2Δ cells. Neither deletion resulted in a dramatic alteration in cell size during the experiments (Fig. 4C), reinforcing the idea that the differences observed in the CFU are due to cell death. These results suggest that Int6/eIF3e and Gcn2 are also required for suppressing cell death caused by histidine starvation, which likely result from oxidative damage.

Fig. 4. Int6/eIF3e and Gcn2 promote viability during histidine starvation.

(A-B) Viability assays in the presence of 30 mM 3AT. KAY641 (WT, black symbols, panel 1), KAY647 (int6Δ, gray symbols, panel 2) and KAY406 (gcn2Δ, light gray symbols, panel 3) were grown exponentially with 120 mM NAC and 30 mM 3AT, as indicated, and assayed for viability, all as in Figs. 3A and B. (B) The time course of cell viability (n=3) was presented as in Fig. 3B. (C) Effect on cell size. Cultures of the cells used in (A) and (B) were withdrawn at the indicated day and measured for the cell sizes, as in Fig. 3C.

As before for the sty1Δ strain, we did find that, after 5 days of 3AT treatment, nearly all int6Δ cells were rendered 3ATR. By contrast, the gcn2Δ cells, defective for the eIF2K pathway, remained 3AT-sensitive (data not shown). These results suggest that histidine starvation induced cellular damage leading to genetic suppression, specifically in the absence of the Sty1 MAPK pathway or the suggested adjunct regulator, Int6 (Fig. 2A).

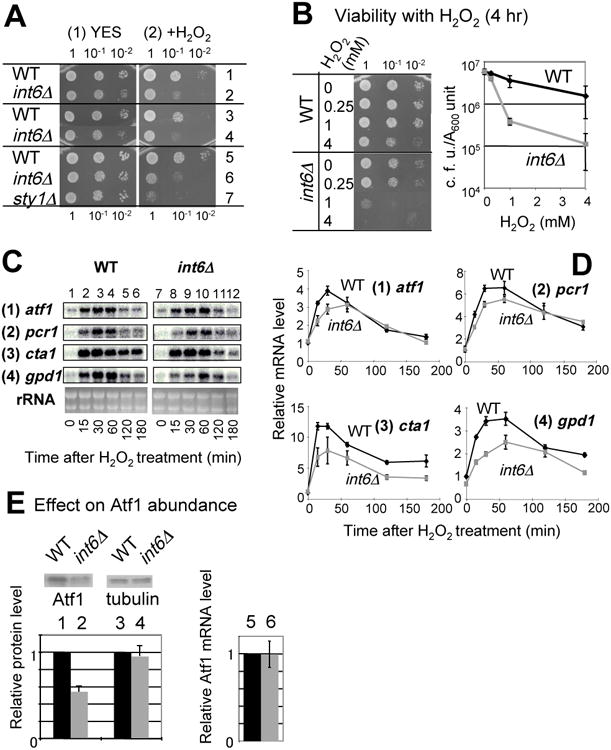

Int6/eIF3e is required for H2O2-induced oxidative stress

To strengthen the idea that Int6/eIF3e is involved in endogenous oxidative stress induced by histidine starvation, we wished to determine if Int6/eIF3e is involved in stimulating the Sty1 pathway directly under H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Dilution assays in Fig. 5A indicated that int6Δ substantially increased sensitivity to continuous H2O2 exposure in three different genetic backgrounds (rows 1-2, h90 ade6-M216; rows 3-4, h- ade6-M216; rows 5-7, h-), as sty1Δ did albeit more strongly (Fig. 5A). To directly test if int6Δ reduced viability during exposure to H2O2 for a defined period, we treated the strains to high levels of H2O2 (1-4 mM) for 4 hours and examined their viability after plating on YES medium agar plates. The int6Δ cells were sensitive to exposure to 1 mM H2O2, while the majority of wild-type cells tolerated this level of exposure (Fig. 5B). Thus, Int6/eIF3e is involved in the oxidative damage response.

Fig. 5. Int6/eIF3e stimulates H2O2-induced oxidative stress response.

(A) Sensitivity test: Cultures of wild type (WT), int6Δ or sty1Δ strains were diluted and spotted onto YES medium alone (panel 1) or with 1 mM H2O2 (panel 2), and grown for 2 days. Included in this sensitivity test are strains KAY456 (row 1), KAY508 (row 2), WY764 (row 3), KAY252 (row 4), KAY641 (row 5), KAY647 (row 6), and KAY640 (row 7). (B) Viability test: Strains KAY456 (WT) and KAY508 (int6Δ) were grown to A600=0.5 and then H2O2 was added at the indicated final concentrations. After incubation for 4 hrs, samples were taken, diluted and spotted onto YES agar plates, and the plate was incubated for 2 days. The graph describes the plot of viability (CFU per A600 culture) against exposed H2O2 dose with bars indicating SD (n=3). (C-D) Effect on CESR transcription: Strains WY764 (WT) and KAY252 (int6Δ) cells were cultured in YES medium with 2 mM H2O2 for the indicated times in min, and RNA was prepared and analyzed by northern blotting using specific probes for the genes indicated to the left of the panel. The bottom panels show EtBr-stained rRNA, which were included as loading controls. Graphs in (D) show the intensity of the transcript bands shown in (C), compared to the value for wild type at time 0 of H2O2 treatment. Graphs present the average from two independent experiments. (E) WY764 (WT) and KAY252 (int6Δ) were grown to an exponential phase in YES medium and analyzed by immunoblotting using affinity-purified anti-Atf1 15 and anti-tubulin (Sigma) antibodies, as indicated. The graph indicates the levels of Atf1 and Tubulin proteins (columns 1-4), averaged from 2 independent experiments, and atf1 mRNA (columns 5-6, average from n=4) in wild-type vs. int6Δ cells, with bars indicating SD.

To examine the effect of int6Δ on Atf1-dependent CESR transcription during H2O2-induced stress, a northern blot analysis was performed to determine the mRNA levels of several key CESR genes (atf1, pcr1, cta1 and gpd1) from wild-type or int6Δ strains following exposure to 2 mM H2O2 for up to 180 minutes. In wild-type cells exposed to H2O2 there was increased levels of each of the transcripts (Fig. 5C and D). For each CESR gene, int6Δ delayed and attenuated their accumulation. We also observed that int6Δ reduced the Atf1 protein abundance prior to applying the stress (Fig. 5E). The reduced Atf1 protein abundance was not accompanied by a change in atf1+ mRNA levels (Fig. 5E), suggesting that int6+ promotes atf1+ expression at the posttranscriptional level in a complex rich medium, as well as in a minimal medium 12. Thus, the diminished CESR transcription observed in int6Δ cells could at least partially result from lowered Atf1 protein abundance. These results indicate that int6+ is also required for the response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress by a mechanism involving regulation of atf1+ expression.

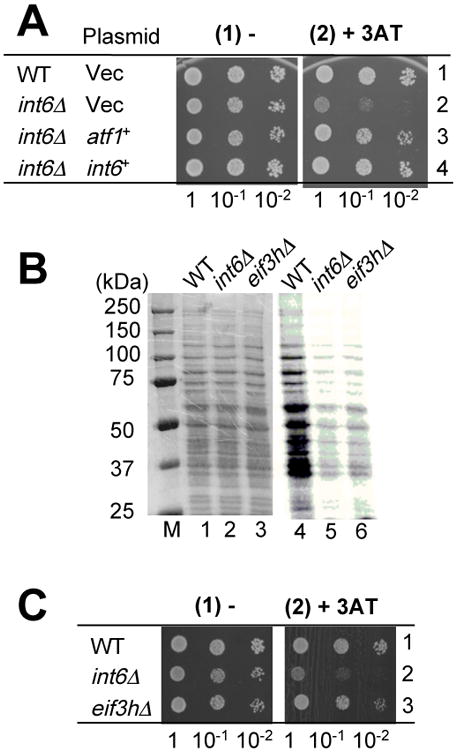

Int6/eIF3e, but not eIF3h, plays a role in rescuing histidine starvation by enhancing atf1+ expression

At this point, the evidence relating Int6/eIF3e and the Sty1 pathway was that they are commonly involved in oxidative stress and that Int6/eIF3e enhances expression of atf1+ encoding the transcription factor targeted by Sty1 12. To establish the genetic relationship between int6+ and atf1+ during histidine starvation, we performed a complementation assay. Fig. 6A indicates that the 3AT sensitivity of int6Δ mutant was partially suppressed by overexpression of Atf1 and, as expected, by that of Int6/eIF3e. These results reinforce the idea that the enhanced expression of atf1+ contributes to the resistance to histidine starvation conferred by int6+ (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 6. Int6/eIF3e, but not eIF3h, is involved in regulation of atf1+ expression.

(A) Complementation assay. Wild-type (WT, KAY586) or int6Δ (KAY587) transformed with pREP41X (Vec), pREP41X-atf1 (atf1+) 15, or pREP-int6 (int6+) 23 were spotted on EMM-C-his-leu medium alone (panel 1) or with 4 mM 3AT (panel 2), and grown for 4 or 6 days, respectively. (B-C) 3AT sensitivity and total protein synthesis of WT (KAY641), int6D (KAY647) and eif3hΔ mutant (KAY649). In (B), cells were grown exponentially in the EMM medium, cultured with 35S-Met for 20 min, and cells were collected and protein lysates prepared. 5 mg total proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, stained by Coomassie blue (lanes 1-3; M, size standards) and analyzed by the STORM phosphorimager (lanes 4-6). In (C), the 3AT sensitivity was assayed on plates containing EMM-C-his medium alone (panel 1) or supplemented with 5 mM 3AT (panel 2) and the plates were incubated for 4 and 6 days, respectively. Because int6Δ and eif3hΔ mutants grew slowly on the minimal agar plate, but less so on the complete agar plate, we used a complete defined medium EMM-C 12.

To determine if the 3AT sensitivity of int6Δ mutant is a general consequence of disruption of eIF3, we created and characterized a yeast mutant deleted for eif3h+ encoding the h subunit of eIF3. The eif3hΔ strain, like int6Δ, substantially reduced the total protein synthesis rate compared to wild-type, as measured by 35S-Met incorporation into total proteins (Fig. 6B and Table 1). Equal Coomassie staining of the total proteins indicates equal protein loading in this experiment (Fig. 6B, lanes 1-3). The reduction in protein synthesis was accompanied by an increase in the doubling time (Table 1). Despite this fact, the eif3hΔ strain did not confer 3AT sensitivity (Fig. 6C). Therefore, the 3AT sensitivity is a specific phenotype associated with loss of the Int6/eIF3e subunit (see Discussion).

Table 1. Effect of eif3hΔ and int6Δ on total protein synthesis and growth rate.

| Strain | Genotype | Total protein synthesis (%)a | Doubling time (min)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| KAY641 | Wild-type | (100) | 156 ± 4 |

| KAY647 | int6Δ | 18 ± 1 | 207 ± 35 |

| KAY649 | eif3hΔ | 29 ± 5 | 187 ± 23 |

35S-incorporation to proteins throughout each lane in the autoradiograph (examples shown in Fig. 6B, lanes 4-6) was determined by the STORM phosphorimager and compared to the value for wild-type (parenthesis). Average of 3 independent experiments.

Doubling time of each strain was measured in the liquid EMM medium at 30° C. Average of 4 independent experiments.

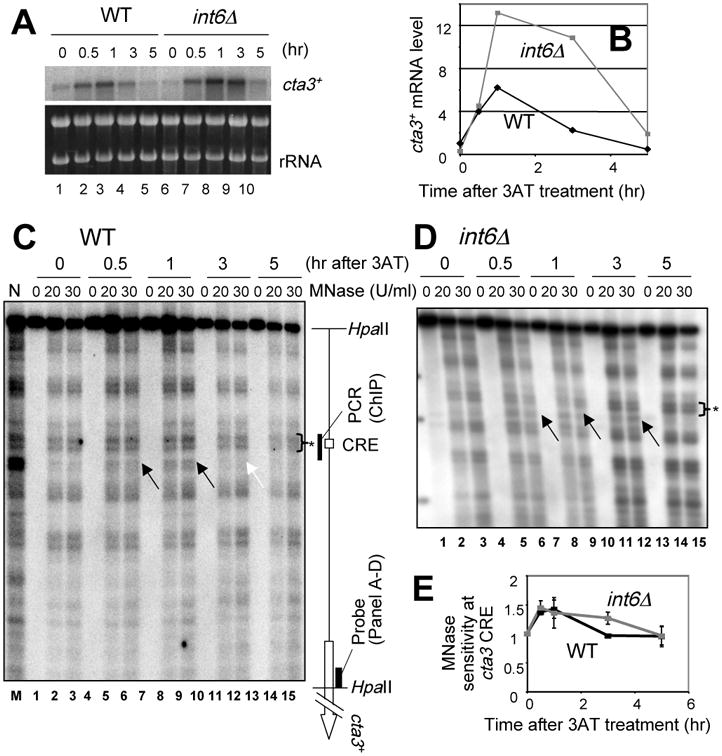

Transcriptional evidence for a feedback mechanism within Int6/eIF3e-assisted Sty1-dependent response caused by histidine starvation

Having gained evidence suggesting that Int6/eIF3e rescues oxidative damage during 3AT-induced starvation, we focused on our previous northern blot studies indicating that int6Δ not only decreases the initial rate of CESR transcript (atf1+, pcr1+, gpd1+, and cta1+, as used in Fig. 1) accumulation upon exposure to 30 mM 3AT, but also allowed extended accumulation of these transcripts, which peaks after 3 hrs of 3AT treatment 12 (also see Fig. S2 below). This extended transcriptional response was accompanied by the extended duration of Wis1-directed Sty1 activation 12. Thus, the delayed and extended CESR transcription appears to indicate an increasing oxidative signal that can activate Sty1 even in int6Δ cells and eventually damage the cells.

To verify these trends at a genome-wide level, we examined the transcriptional microarray data of 3AT-treated int6Δ cells. Of the 169 CESR transcripts induced by 30 mM 3AT (termed cluster 2 genes in 12), the abundance of 85 % of these mRNAs (144 genes) was lower in int6Δ cells than in wild-type after 1 hr of 3AT addition, in agreement with their slower accumulation. Conversely, the abundance of 51 % of these transcripts (87 genes) was higher in int6Δ cells than in wild-type after 3 hrs of 3AT addition. Again this is in agreement with the delayed accumulation. Together, expression of 61 CESR genes showed the combined lower expression at 1 hr and higher expression at 3 hr in int6Δ cells after 3AT addition. This pattern is in agreement with the delayed and extended CESR transcription suggested by our northern blot experiments 12.

To address if int6Δ extends the duration of Atf1 transcriptional activity rather than, for example, the stability of the transcripts, we examined changes in chromatin structure at a Atf1-binding site (CRE, cAMP-response element) 35. We chose cta3+, encoding a P-type ATPase cation pump, because its expression was strongly enhanced after 3 hrs of the stress application (Fig. 7A-B). As shown in Fig. 7C, micrococcal nuclease (MNase) sensitivity at a site near the cta3 CRE, indicative of the nucleosome remodeling therein, was increased at 0.5 to 1 hr after 3-AT treatment in wild-type cells (arrows in the gel), coincident with cta3 mRNA and other CESR mRNA accumulation (Fig. 7A-B). In int6Δ cells, the remodeling of the area near cta3 CRE lasted longer and could be observed after 3 hr of 3AT treatment (arrows in Fig. 7D, also see Fig. 6E for quantification of MNase sensitivity), again coinciding with the abundance of cta3 mRNA (Fig. 7A-B). Thus, int6Δ extends the duration of remodeling of an Atf1-dependent gene during histidine starvation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirmed that Atf1 actually binds the cta3 CRE, although Atf1 was bound to the CRE before the stress, as observed for other CREs 14, and the increase in Atf1 binding by 3AT treatment was minor though significant (KH, KA and KO, unpublished data; see Materials and methods).

Fig. 7. Direct effect of int6Δ on Atf1 activity at its binding site upstream of cta3+.

(A-B) Effect of int6Δ on 3AT-induced cta3+ mRNA levels. Strains WY764 (WT) and KAY252 (int6Δ) were grown in the presence of 3AT, withdrawn at the indicated times, and analyzed by northern blotting using a 32P-cta3 probe as described in Fig. 1. Autoradiography generated from the northern analysis is illustrated in the top panel (and EtBr staining of rRNA was included as a loading control - bottom panel). Graph in (B) presents the mRNA levels relative to wild-type at time 0. (C-D) Changes in the nucleosome structure at cta3+ CRE. Crude chromatin fractions from wild-type (C) and int6Δ (D) cells treated with 3AT for the indicated times were partially digested with MNase at the concentrations listed at the top of the panel. DNA was prepared and and analyzed by Southern blotting, as described in the Experimental Procedures. Black arrows indicate MNase cleavage sites enhanced by 3AT treatment. The White arrow indicates the cleavage site, which disappeared in wild-type DNA after 3 hrs of treatment. The schematic to the right of (C) describes the location of the CRE, the DNA fragments mentioned, and cta3+ ORF. N, naked DNA treated with MNase. (E) The graph indicates the time course of the intensity of MNase cleavage at the cta3 CRE (arrows in C-D), relative to that of the unchanged cleavage site (asterisks in C-D) in wild-type (black symbols) and int6Δ (gray symbols) cells. The intensity of cleavage was averaged from lanes with 20 and 30 U/ml MNase; bars indicate the SD from two independent measurements.

Together with our previous report 12, these results support the idea that a Sty1-activating signal, most likely oxidative stress, builds up within 3AT-treated int6Δ cells due to a failure to quickly antagonize the original (oxidative) stress and that the increased signal in turn activates Sty1. Thus, our results also suggest that a feedback loop operates within the 3AT-induced Sty1 pathway, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. However, we could not determine whether the original Sty1-activating signal, which quickly activated Sty1, within 15 min, on 3AT exposure 12, is also an oxidative stress (see Discussion).

Transcriptional evidence that Gcn2 reduces oxidative stress during histidine starvation

In agreement with the relationship of gcn2+-regulated genes with oxidative stress, our cDNA microarray analysis indicated that 3AT-induced genes requiring gcn2+ (cluster 3 12) include genes potentially ameliorating oxidative damage, as listed in Table 2. Grx4 is a nuclear glutaredoxin, antagonizing oxidative damage of the chromosomes 36. SPAC1F12.06c encodes a predicted DNA repair endonuclease V, whereas SPCC18.09c encodes the yeast homologue of Aprataxin, a human protein that binds damaged DNA and is involved in DNA repair 37. The expression of yct1, encoding a potential cysteine transporter 38, would favor glutathione synthesis. Furthermore, cluster 3 includes many predicted mitochondrial proteins, of which mmf1, gor1 and atm1 are likely to be involved in mitochondrial maintenance (Table 2), based on studies of the homologous S. cerevisiae genes 39; 40. In particular, the S. cerevisiae mutant deleted for ATM1, encoding a Fe/S cluster precursor transporter, increases the level of glutathione, which protects against oxidative stress 40. Thus, gcn2+ can promote expression of genes involved in mitochondrial maintenance and biogenesis, which can influence oxidative damage (Fig. 2A).

Table 2. 3AT-induced genes that are dependent on Gcn2 (cluster 3 in Ref 12) and potentially involved in oxidative stress response.

| Gene | Systematic Name | Fold up in wild-type cellsa | Fold up in gcn2Δ cellsb | Descriptionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair genes | ||||

| grx4 | SPAPB2B4.02 | 2.9 | 1.3 | Nuclear glutaredoxin essential for viability |

| C1F12.06c | SPAC1F12.06c | 2.7 | 1.0 | DNA repair endonuclease V (predicted) |

| C18.09c | SPCC18.09c | 3.0 | 1.2 | human aprataxin homolog |

| Cysteine transport | ||||

| yct1 | SPCPB1C11.03 | 4.2 | 0.3 | Cysteine transporter (predicted) |

| Mitochondrial genes | ||||

| mmf1 | SPBC2G2.04c | 3.9 | 0.8 | YjgF family protein similar to S. cerevisiae Mmf1p, which is involved in mitochondrial DNA stability |

| gor1 | SPBC1773.17c | 2.5 | 0.5 | glyoxylate reductase (predicted) |

| atm1 | SPAC15A10.01 | 4.7 | 0.9 | mitochondrial inner membrane component, ABC family iron transporter (predicted) |

| C3G6.05 | SPAC3G6.05 | 3.2 | 1.2 | Mvp17/PMP22 family protein 1, with a mitochondrial localization signal |

| C1235.11 | SPCC1235.11 | 2.0 | 0.9 | mitochondrial protein, human BRP44L ortholog |

| C1259.09c | SPCC1259.09c | 2.7 | 0.9 | Probable pyruvate dehydrogenase protein × component, mitochondrial |

| Homocysteine synthesis | ||||

| str3 | SPCC11E10.01 | 3.0 | 1.2 | cystathionine β-lyase (predicted) |

Fold increase in mRNA abundance after 3 hrs of 3AT treatment, compared to the value in wild-type at time 0.

Based on Gene Ontology (GO) database, with relevant information added from S. pombe Gene Database,

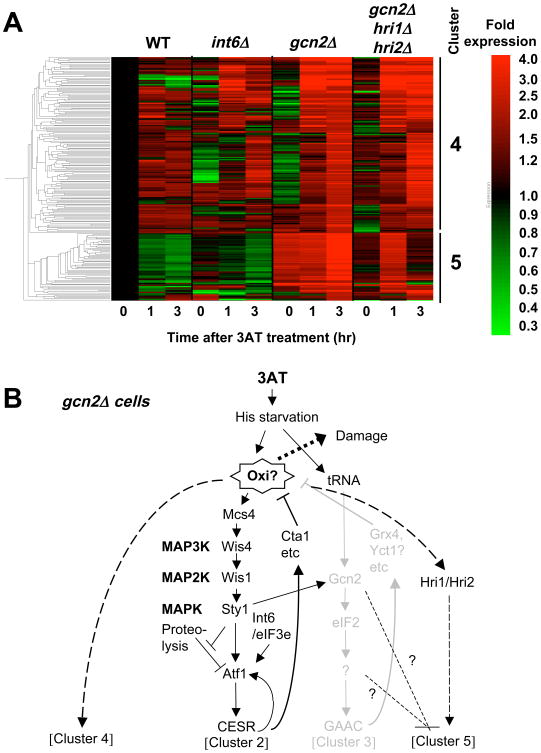

If Gcn2 alleviates oxidative damage, the lack of gcn2+ would cause oxidative stress in the presence of 3AT, which might in turn express a specific response. To test this idea, we analyzed genes that are specifically induced in 3AT-treated gcn2Δ cells. Indeed, our re-analysis of expression profiling data of 3AT-treated gcn2Δ cells 12 revealed 217 genes, which are induced less than 2-fold in wild-type cells, but induced more than 2-fold in gcn2Δ cells after 3 hr of 3AT treatment. As shown in Fig. 8A, cluster analysis divided these genes into two groups, clusters 4 and 5 following the cluster numbers described previously 12. Table S1 shows 121 genes belonging to clusters 4 and 5, not induced more than 2-fold in wild-type but induced by an even higher 2.4-fold in gcn2Δ cells treated with 30 mM 3AT. The genes in cluster 4 encode heatshock proteins, redox enzymes, and proteins involved in protein degradation and mitochondrial maintenance. Cluster 4 generally overlaps with stress genes, especially with oxidative stress genes (p=2 e-24). The genes in this cluster also strongly overlap with the cluster 7 genes (Fig. 2 in Ref 41) that are strongly induced by two oxidative compounds, menadione and t-butylhydroperoxide, but not by hydrogen peroxide (p= 3 e-12) and with a set of genes (Fig. 4A in Ref 41) whose transcription does not depend on a kinase or transcription factor known to drive the oxidative stress response, such as Sty1, Pmk1, Atf1, Pcr1, or Pap1 (p = 2 e-09). Thus, the observed expression of cluster 4 genes is consistent with the model that this novel set of genes respond to oxidative damage generated in gcn2Δ cells (Fig. 8B). Cluster 5 genes encode proteins involved in protein folding or degradation and mitochondrial maintenance, again consistent with the generation of oxidative stress (Table S1). However, this cluster does not overlap with any known gene list (see Fig. 8B and Discussion).

Fig. 8. Genes induced by 3AT specifically in the absence of gcn2+.

(A) Clustering of 217 genes induced <2-fold in wild-type and >2-fold by 30 mM 3AT in gcn2Δ cells 12, with the level of expression presented by the red/green scale bar to the right. Each column represents expression level of the genes in yeast carrying mutations indicated across the top after 3AT treatment for the time shown on the bottom. Bars and numbers to the right indicate the gene cluster identified. (B) Model of gene regulation within gcn2Δ cells. Black and gray drawings indicate the pathways proposed to operate or shut down, respectively, in the cells. The model states that the absence of Gcn2 generates oxidative damage (Oxi?), which in turn induces clusters 4 and 5, with the latter repressed by gcn2+ and stimulated by hri1+/hri2+.

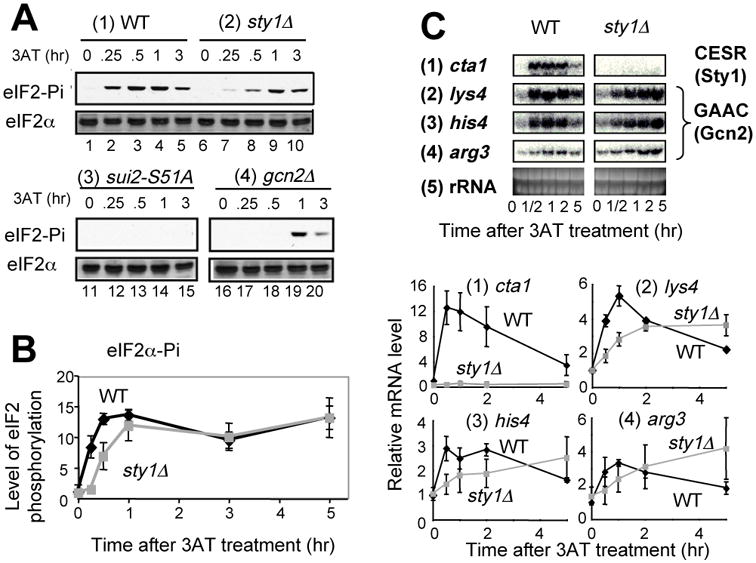

Sty1 MAPK stimulates Gcn2-dependent transcription by enhancing Gcn2 activation

We next examined the crosstalk between the Sty1 and Gcn2 pathways in the 3AT-induced stress response. Immunoblotting with anti-phospho eIF2α antibodies confirmed that Gcn2 phosphorylation of eIF2α peaks between 30 min and 1 hr of 3AT addition (Fig. 9A). Phosphorylation was absent when alanine was substituted for Ser-51 of eIF2α. Deletion of gcn2+ significantly delayed eIF2α phosphorylation, suggesting that alternative eIF2Ks, Hri1 and/or Hri2, can partially compensate in response to 3AT. Importantly, the maximal Gcn2 phosphorylation of eIF2α is preceded by Sty1 activation, which is at a maximum within the first 15 min of 3AT stress 12. To test whether the early Sty1 activation can contribute to Gcn2 function, we examined the effect of sty1Δ on 3AT-induced eIF2α phosphorylation and the attendant Gcn2-dependent transcription. We found that sty1Δ significantly delayed Gcn2 phosphorylation of eIF2α within the first 30 min of 3AT addition (Fig. 9A and B). Moreover, sty1Δ significantly delayed Gcn2-dependent gene transcription accordingly (Fig. 9C); in wild-type cells, the accumulation of the three Gcn2 target transcripts peaked at 1 hr of 3AT-induced starvation, the same time as for the CESR transcription. Loss of Sty1 diminished this early peak response, and rather enhanced Gcn2-dependent gene transcription later especially after 5 hr of starvation (Fig. 9C). These results indicate that sty1+ can promote rapid Gcn2-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation and the attendant GAAC transcription during histidine starvation (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 9. Sty1 MAPK stimulates Gcn2 phosphorylation of eIF2α.

(A) eIF2 phosphorylation: Strains KAY641 (panel 1), KAY640 (panel 2), JP436 (panel 3), and KAY406 (panel 4) were grown in EMM-C-his to an early exponential phase and then 30 mM 3AT was added. Cells were harvested, and protein lysates were prepared and analyzed immunoblotting with anti-phospho eIF2α (top panel) or total eIF2α (bottom panel) antibodies, as described 9. (B) The graph shows the relative levels of phospho-eIF2α, normalized for total eIF2α levels in the wild-type (black symbols) or sty1Δ (gray symbols) cells used in (A). The values are compared to the ratio calculated for wild-type at time 0. Bars indicate the SD (n=3 or more). (C) 3AT-induced transcript level changes were examined in strain KAY641 (wild-type) and KAY640 (sty1Δ) for the genes indicated to the left, as described in Fig. 1.

Because an increase in eIF2α phosphorylation was observed in a sty1 mutant 42, it was conceivable that the later enhancement of GAAC transcription in sty1Δ cells after 5 hrs of 3AT treatment was due to an increased level of eIF2α phosphorylation. To test this idea, we examined the eIF2α phosphorylation until 5 hrs of 3AT treatment. However, sty1Δ did not alter the level of eIF2α phosphorylation compared to wild-type after 3-5 hrs of 3AT treatment (Fig. 9B). Thus, an additional factor contributes to the sty1Δ-induced enhancement of GAAC transcription.

Discussion

The evidence presented here, suggesting that the oxidative stress response represents a major component of fission yeast response to 3AT-induced histidine starvation, is based on the viability assays of the mutants deleted for the sty1+, gcn2+ and int6+ genes, which are directly involved in the response to 3AT-induced starvation (Fig. 3-4), as well as transcriptional profiles (both northern blot and microarray) consistent with expression of potential antioxidant genes at the timing expected for individual mutations (Fig. 1, 7) 12. Although the addition of NAC complimented the reduced viability caused by 3AT-induced starvation (Fig. 3-4), NAC or its cellular product, reduced glutathione, can have functions other than anti-oxidation, so the experiments with NAC do not necessarily prove an anti-oxidation function. However, our ferric-xylenol orange assay 43 recently showed that the lipid fractions isolated from wild-type S. pombe, which had been treated for 3 – 24 hrs with 3AT in the same medium as we used here, was 2-3-fold more strongly peroxidized, and that NAC addition reduced this effect (NN, Kimberly Hall, Yuka Ikeda, Ruth Welti and KA, unpublished data), in agreement with the idea that the NAC indeed rescues oxidative damage within the 3AT-treated cells. Together with this finding and the transcriptional evidence indicating that int6Δ delays and extends the duration of Sty1-activation and the attendant transcription 12, we propose that a feedback mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 2A, operates within the Sty1 pathway, and that Int6/eIF3e plays an important role in this regulation.

The source of oxidative signals that leads to Sty1 activation under the feedback response is likely to be complex. An example of the internal source of oxidation would include oxidative degradation of metabolic compounds in the peroxisomes which requires high catalase activity for detoxifying generated H2O2, or a change of mitochondrial respiration status that can occur during a shift from anaerobic to aerobic conditions. In support of the mitochondria-derived oxidation, the importance of mitochondrial maintenance during histidine starvation is suggested by possible Gcn2 regulation of genes involved in this process, both positively (cluster 3, Table 2) and negatively (cluster 5, Fig. 8 and Table S1).

However, we could not obtain clues to help us understand the mechanism whereby the original starvation signal quickly promoted Sty1 activation and attendant transcription, as observed in Fig. 1. In order to address this question, we examined the effect of NAC on 3AT-induced CESR transcription, but NAC had only a marginal effect on this robust transcriptional response (Fig. S2). This negative result rather suggests that Sty1 is rapidly activated by a feed-forward mechanism, without being mediated by an oxidative signal (? in Fig. 2A). A feed-forward mechanism can evolve as a result of repeated changes in the environment 44. Shiozaki et al. previously showed that carbon source starvation also activates the Sty1 MAPK cascade, in this case directly via Mcs4 45. Thus, it would be important to determine whether the nutritional stress arrangements that lead to Sty1 activation commonly result in the generation of endogenous oxidative stress.

The role for Int6/eIF3e in regulation of atf1+ gene expression

Here we also showed that atf1+ expression can rescue the 3AT sensitivity of an int6Δ mutant (Fig. 3E), reinforcing that int6+ regulates atf1+. How does Int6/eIF3e regulate atf1+ expression? Int6/eIF3e is an important part of eIF3 23; 24, promoting general protein synthesis (Table 1 and Fig. 3) 12. The atf1+ mRNA has a relatively long 5′-UTR of ∼300 bp, devoide of any uORFs, which has been shown to be important for translational control for other mRNAs 46. Given that Int6/eIF3e forms an interface to eIF4F in humans 26, the intact eIF3 with this subunit might promote translation of capped mRNAs with a relatively long 5′-UTR, including atf1+ mRNA. An alternative model suggested by the specific effect of int6Δ on 3AT sensitivity, compared to that of eif3hΔ (Fig. 6B-C and Table 1), states that Int6/eIF3e more specifically interacts with a subset of mRNA including atf1+ mRNA. Mass spectrometry analysis of human eIF3 indicates that eIF3e is located in the proximity to the RNA-binding eIF3d subunit 47; 48, raising the possibility that the eIF3e/eIF3d module can serve as a mRNA regulatory unit of eIF3. Combined sty1Δ int6Δ strains show stronger sensitivity to 3AT compared to single mutants 12, suggesting that int6+ also regulates damage response pathway(s) other than the Sty1 pathway. Therefore, it would be important to address the molecular basis of the regulation of atf1+ expression by Int6/eIF3e and find additional targets regulated by this eIF3 subunit.

Potential role for Gcn2 in the response to endogenous oxidative stress during histidine starvation

Our suggestion that Gcn2 may play a role in anti-oxidation (Table 2, Fig. 8) is consistent with the finding that the mammalian ISR, governed by eIF2Ks, contributes to glutathione biosynthesis and resistance to oxidative stress 6. The expression of anti-oxidant clusters 4 and 5 in gcn2Δ cells (Fig. 8) provides additional evidence that the Gcn2-dependent response includes a response to oxidative stress during histidine starvation. Of interest were the cluster 5 genes whose expression is repressed by gcn2+ and induced in its absence in a manner dependent on hri1+ and hri2+ (Fig. 8). HRI eIF2 kinases possess a heme-binding site, which may be used to sense oxidative compounds 1. In the absence of gcn2+, eIF2α is partially phosphorylated by 3AT treatment in a manner dependent on hri1+ and hri2+ 12 (also see Fig. 9A, panel 4). Thus, Hri1/Hri2 appear to be activated by the oxidative stress, thereby stimulating the expression of cluster 5 by an unknown mechanism (Fig. 8B). As for the regulation of cluster 4, the gene induced most highly in gcn2Δ cells (by 12-fold) belongs to this cluster and encodes a potential transcription factor (Table S1), whose S. cerevisiae homolog, Mbf1p, is a co-activator of Gcn4p 49. Thus, it would be intriguing to test whether this protein and an unidentified Gcn2 target facilitate the transcription of this set of genes.

Sty1-mediated activation of Gcn2 (Fig. 9) would couple the major stress-activated MAPK pathway to translational control. Because exogenous H2O2 does not induce GAAC transcription (TU and KA, unpublished data), the coupling of Sty1 and Gcn2 appear to be restricted to specific stress arrangements, such as those involving nutrient starvation. Sty1 could activate Gcn2 directly or indirectly. The indirect mechanism may involve other signaling pathways, known to respond to nutritional stresses, such as TOR protein kinase pathways, which are proposed to regulate S. cerevisiae Gcn2p 50,51, and S. pombe Gcn2 specifically via Tor1 52. Extending the human relevance of this study, a coupling of ERK MAPK and Gcn2 pathways is reported to occur following amino acid limitation of human hepatoma cells 53.

Implication to cancer biology

Appropriate expression of anti-oxidation pathways is vital to tumor suppression 54. For example, cells expressing activated H-Ras produce H2O2, and the resulting oxidative damage is ameliorated by the human homologue of Sty1, p38, which suppresses H-Ras-activated tumorigenesis 55. If the oxidative damage that we propose to be present in the int6Δ yeast mutant, also occurs in mammalian cells with compromised Int-6/eIF3e activity, this might facilitate tumorigenesis by a process involving DNA mutations elicited during oxidative damage 54. In addition, nutrient limitation is suggested to occur with progression of solid tumors. Accordingly, recent studies highlight pro-oncogenic role for eIF2Ks and attendant ISR expression in securing sufficient nutrients and alleviating oxidative damage 7. However, oxidative damage, when untreated by the MAPK and/or eIF2K pathways, may also compound tumorigenesis, enhancing genetic diversity that could contribute to aggressiveness of tumors. Indeed, earlier studies implicated eIF2Ks in tumor suppression, and there is a strong correlation of up-regulation of protein synthesis with the progress of tumorigenesis 2. In light of this study, it would be intriguing to investigate the role of eIF2Ks and ISR-directed anti-oxidation in preventing tumor initiation.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast strains

Yeast S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. We used strains prototrophic for amino acid biosynthesis in order to address resistance to 3-amino triazole (3AT), an inhibitor of histidine synthesis. For this purpose we used transformation with leu1+ or his7+ -encoding plasmids, to convert leucine and/or histidine auxotrophy of previously constructed strains. Accordingly, strains KAY793 and KAY794, are transformants of KS2096 56 and CA220 57 respectively, carrying pREP41X (leu1+). KAY852 is a transformant of JM1505 58 carrying pREP41X (leu1+) and pEA500 (his7+).

KAY649 (eif3hD) was constructed by introducing the eif3h+ (SPAC821.05) disruption DNA, generated by PCR using oligos eIF3h-FW and eIF3h-RV (Table 2) and pKS-FA-ura4 (provided by Y. Watanabe, University of Tokyo) as a template. pKS-FA-ura4 is a derivative of pKS-ura4 59 carrying the same primer-binding site as those of pFA6a derivatives. The resulting disruption DNA carries ura4+ in the reverse orientation relative to eif3h+. The integration of the disruption DNA into eif3h+ was confirmed by PCR using a pair of oligonucleotides, one binding to a chromosomal site outside of the region present in the eif3h+ disruption DNA and the other binding to ura4+- coding region, namely eIF3h-up and ura4-midF and eIF3h-down and ura4-midR, respectively (Table 2).

KAY586 was prepared by converting the ura4-D18 locus of JY879 (h90 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18) (provided by M. Yamamoto, University of Tokyo) into ura4+ by transformation with the PCR-synthesized ura4+ fragment, as described 12. Then, KAY587 was created by introducing int6Δ by transformation with the PCR-synthesized int6Δ∷kanMX fragment, as described 23.

Yeast media

We used the complex rich medium YES and the defined medium EMM throughout our study 60. To study histidine starvation by the addition of 3AT, we omitted histidine in the media and used minimal EMM medium or complete EMM medium supplemented with amino acids and other nutrients but lacking histidine (EMM-C-his), as described 12. To study the effect of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (Fisher Chemical O1049), we used the minimal EMM supplemented with adenine (EMM+Ade) or EMM dropout with complete amino acids and other supplements, as described 12. We determined that NAC was effective when its concentration was 4 to 5 times higher than 3AT in the EMM+Ade medium. Thus, 40 mM NAC was supplemented with the EMM+Ade medium containing 10 mM 3AT. Likewise, 120 mM NAC was supplemented with the EMM+Ade medium containing 30 mM 3AT. To add these NAC concentrations to the EMM medium, a stock solution of NAC was prepared in EMM to a final concentration of 500 mM, which was then neutralized to pH5.6 by KOH, and filter-sterilized.

Yeast growth and viability assays

Yeast were grown at the permissive temperature of 30°C throughout the study. To determine the titer of yeast for both the drug sensitivity and viability assays, we spotted 5 ml 0.15 A600 units of culture, or 10-fold and 100-fold dilutions of this culture preparation, onto the agar plates and incubated the plates at 30°C. For 3AT sensitivity assays, spotted cultures were incubated in medium containing the indicated concentrations of 3AT, NAC, and histidine. For the viability assays following 3AT-induced histidine starvation, fresh overnight cultures of yeast were inoculated into ∼3 ml liquid EMM+Ade medium with the indicated concentrations of NAC, histidine, and 3AT. The cultures were initiated at A600∼0.3 with constant agitation at 30°C, and the aliquots were periodically removed to measure the absorbance at 600 nm, which was subsequently plotted against the growth time. Additionally, serially diluted cultures were spotted onto the YES agar plates, incubated at 30°C for 2 days, and photographed. Colonies formed on each spot were counted to determine the viability, as presented by colony forming units (CFU) per A600. If two or more serially diluted spots contained well-dispersed colonies, the CFU per A600 values obtained from each spot were averaged to determine the viability value for that condition. Three independent viability assays were performed.

For viability assays with H2O2, cells were grown to A600=0.5 and then H2O2 was added at the different final concentrations. After treatment for 4 hrs, the culture was withdrawn, diluted and spotted onto YES plates and the plate was incubated for 2 days.

Biochemical and molecular biology methods

Standard biochemical, genetic, and molecular biology techniques were used throughout the study. Northern and western blot assays were performed as described 12, using 32P-probes generated by PCR with the pair of primers as listed in Table 2 and affinity-purified anti-Atf1 antibodies 15, respectively. The total protein synthesis rate was measured by 35S-methionine incorporation, also as described 15. Statistical analyses used T test.

To perform the analysis of nucleosome structures, crude chromatin fractions from 3AT-treated cells were digested partially with 0, 20, or 30 U/ml MNase, and DNA was purified for complete HpaII digestion and gel electrophoresis 35. The position of MNase-cleavage was determined by Southern blot hybridization to the cleavage products using 32P-DNA probe specific to a part of the cta3+ coding region. Primers used to amplify the labeled probe are listed in Table 2. To confirm Atf1-binding to the cta3+ CRE, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation using a strain encoding Atf1-HA and anti-HA antibodies, as essentially described 14. Briefly, the area of cta3 CRE bound to Atf1-HA was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and detected by quantitative real-time PCR with the primers listed in Table 2.

Microarray analysis

Microarray data generated previously 12 was re-analyzed in GeneSpring (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). The significance of overlap between different gene lists was calculated in GeneSpring by using a standard Fisher's exact test, and the p values were adjusted with a Bonferroni multiple testing correction.

Supplementary Material

Table 3. Strains used in this study.

| Strains | Genotype (Reference if constructed previously) |

|---|---|

| SP223 derivatives | |

| WY764 | h- ade6-M216 leu1-32∷leu1+ ura4-D18∷ura4+ (1) |

| KAY252 | h- ade6-M216 leu1-32∷leu1+ ura4-D18∷ura4+ int6Δ∷kanMX (2) |

| KAY406 | h- ade6-M216 leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18 gcn2Δ∷ura4+(2) |

| JY878 derivatives | |

| KAY456 | h90 ade6-M216 leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18∷ura4+(2) |

| KAY508 | h90 ade6-M216 leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18∷ura4+ int6Δ∷kanMX (2) |

| JY879 derivatives | |

| KAY586 | h90 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 ura4+ |

| KAY587 | h90 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 ura4+ int6Δ∷kanMX |

| PR109 derivatives | |

| KAY641 | h- leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18∷ura4+(2) |

| KAY647 | h- leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18∷ura4+ int6Δ∷kanMX (2) |

| KAY640 | h- leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18 sty1Δ∷ura4+(2) |

| KAY649 | h- leu1-32∷leu1+ <pJK148> ura4-D18 eif3hΔ∷ ura4+ |

| KAY793 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 sty1-His6HA∷ura4+wis1-Myc∷ura4+ p(leu1+) |

| KAY794 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 sty1-His6HA∷ura4+mcs4∷ura4+ p(leu1+) |

| Miscellaneous | |

| JP3 | h- (3) |

| JP260 | h+ wis1∷ kanMX (3) |

| JP436 | h+ ade6-M210 ura4-D18 sui2-S51A∷ura4+(4) |

| KAY852 | h90 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his7-366 wis4∷ura4+ p(leu1+) p(his7+) |

Table 4. List of oligodeoxyribonucleotides used in this study.

| The following primers were designed to create and confirm the strains deleted for eif3h+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Nucleotide sequences (5′ to 3′) | Gene | |

| 1 | eIF3h-FW | TAGAAAAGGTTTAATAAAACTGGTAGG CTCCTCTATTCTATAACTTGTAATCGCC GACAGCCATGGCTTTAAAAAGTTGCCG GATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA TTAAGTAGATCCTTTTATTTTAATGCTAC GAGGTATAACTAGTGAGAGTGAAGAAGA ATGCTCCATTTTTTATAAACAAAGAATTC |

eif3h |

| 2 | eIF3h-RV | GAGCTCGTTTAAAC | eif3h |

| 3 | eIF3h-up | GAGCTTAAGGCCGAGAAAAC | eif3h |

| 4 | eIF3h-down | TATGCTGTATCAAGAAAACC | eif3h |

| 5 | ura4-midF | GTGTGTACTTTGAAAGTCTAGCTTTA | ura4 |

| 6 | ura4-midR | CCTTGTATAATACCCTCGCC | ura4 |

| The following primers were designed by the Bähler group in their microarray studies 61 | |||

| 7 | 2-A11_C418.01c_his4_F | TAGAGAACTCCTTTGGCGGA | his4 |

| 8 | 2-A11_C418.01c_his4_R | CAACTTCGACAGCAGGATGA | his4 |

| 9 | 20-G9_arg3_F | TCTCCAGGCGTTAGCAGATT | arg3 |

| 10 | 20-G9_arg3_R | TGCATGAATTTGCAGCTAGG | arg3 |

| 11 | 2-E7_C1105.02c_lys4_F | CAACCGTGTTGGTATTGCTG | lys4 |

| 12 | 2-E7_C1105.02c_lys4_R | GCGACAAGGTTTTCAAGCTC | lys4 |

| 13 | 53-F9_atf1 mts1 sss1 gad7_F | ACCCCTACTGGAGCTGGATT | atf1 |

| 14 | 53-F9_atf1 mts1 sss1 gad7_R | TACCTGTAACAGCTTGGGGG | atf1 |

| 15 | 27-H10_cr1 mts2 F | CGCTTCTAAATTTCGCCAGA | pcr1 |

| 16 | 27-H10_cr1 mts2_R | GGTGTTGATTTGGAGGGAGA | pcr1 |

| 17 | 33-G9_gpd1_F | GGTGTAGTTGGCTCCGGTAA | gpd1 |

| 18 | 33-G9_gpd1_R | TCTCACAGAATTGCTCACGG | gpd1 |

| 19 | 12-F1_cta1_F | TTCGTGATCCCGCTAAATTC | cta1 |

| 20 | 12-F1_cta1_R | AAGGTAAAGCGTCCAACCCT | cta1 |

| The following primers were designed by the group of K. Ohta (see Fig. 7C) | |||

| 21 | cta3 ORF-5′ | CGAACATTGGCTTCTCC | cta3 |

| 22 | cta3 ORF-3′ | GGTTGCGTAACAAATTCC | cta3 |

| 23 | cta3 CRE-5′ | TAACAACACTCCGCCATTCG | cta3 |

| 24 | cta3 CRE-3′ | TGACTCCGACATTGATTTCCT | cta3 |

Histidine-starved yeast loses viability likely due to oxidative damage.

Stress-activated Sty1 MAPK and Gcn2 eIF2K rescue this oxidative damage.

Int6/eIF3e assists the antioxidation function of the Sty1 pathway.

Int6/eIF3e does so by enhancing expression of Atf1 targeted by Sty1.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Boye, C. Hoffman, J. Millar, J. Petersen, K. Shiozaki, Y. Watanabe and M. Yamamoto for timely gift of materials, K. Hall, Y. Ikeda, and R. Welti for sharing results before publication and H. Masai for stimulating discussion. This work was supported by the NCRR K-INBRE pilot grant P20 RR016475, Innovative Award from KSU Terry Johnson Cancer Center and NIH GM67481 to KA, and by NIH GM49164 to RW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dever TE, Dar AC, Sicheri F. The eIF2α kinase. In: Mathews MB, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, editors. Translational Control in Biology and Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 319–344. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider RJ, Sonenberg N. Translational control in cancer development and progression. In: Mathews MB, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, editors. Translational Control in Biology and Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 401–431. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: Signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Phys. 2003;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi M, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, Fels D, Blais J, Hu N, Harding H, Novoa I, Varia M, Raleigh J, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Bell J, Ron D, Wouters BG, Koumenis C. ER stress-regulated tanslation increases tolerance to extreme hypoxia and promotes tumor growth. EMBO J. 2005;24:3470–3481. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Wise DR, Diehl JA, Simon MC. Hypoxic reactive oxygen species regulate the integrated stress response and cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31153–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R, Stojdl DF, Bell JC, Hettmann T, Leiden JM, Ron D. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Molecular Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye J, Koumenis C. ATF4, an ER stress and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor and its potential role in hypoxia tolerance and tumorigenesis. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:411–416. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blais JD, Addison CL, Edge R, Falls T, Zhao H, Wary K, Koumenis C, Harding H, Ron D, Holcik M, Bell JC. PERK-dependent translational regulation promotes tumor cell adaptation and angiogenesis in response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9519–9532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01145-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan K, Vattem KM, Bauer BN, Dever TE, Chen JJ, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 by heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-related protein kinases in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is important for resistance to environmental stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7134–7146. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7134-7146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhan K, Narasimhan J, Wek RC. Differential activation of eIF2 kinases in response to cellular stresses in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2004;168:1867–1875. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natarajan K, Meyer MR, Jackson BM, Slade D, Roberts C, Hinnebusch AG, Marton MJ. Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4347–4368. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4347-4368.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udagawa T, Nemoto N, Wilkinson C, Narashimhan J, Watt S, Jiang L, Zook A, Jones N, Wek RC, Bähler J, Asano K. Int6/eIF3e promotes general translation and Atf1 abundance to modulate Sty1 MAP kinase-dependent stree response in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22063–22075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710017200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikner A, Shiozaki K. Yeast signaling pathways in the oxidative stress response. Mut Res. 2005;569:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter W, Watt S, Dawson K, Lawrence CL, Bähler J, Jones N, Wilkinson CRM. Fission yeast MAP kinase Sty1 is recruited to stress-induced genes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9945–9956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710428200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence CL, Maekawa H, Worthington JL, Reiter W, Wilkinson CRM, Jones N. Regulation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Atf1 protein levels by Sty1-mdeiated phosphorylation and heterodimerrization with Pcr1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5160–5170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K, Brazma A, Jones N, Bähler J. Global transcriptional response of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:214–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Miyazaki S, Gallahan D, Smith GH, Callahan R. Int-6, a highly conserved, widely expressed gene, is mutated by mouse mammary tumor virus in mammary preneoplasia. J Virol. 1995;69:1932–1938. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1932-1938.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asano K, Merrick WC, Hershey JWB. The translation initiation factor eIF3-p48 subunit is encoded by int-6, a site of frequent integration by the mouse mammary tumor virus genome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23477–23480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinnebusch AG, Dever TE, Asano K. Mechanism of translation initiation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Mathews MB, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, editors. Translational Control in Biology and Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 225–268. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen SB, Kordon E, Callahan R, Smith GH. Evidence for the transforming activity of a truncated Int6 gene, in vitro. Oncogene. 2001;20 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayeur GL, Hershey JWB. Malignant transformation by the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit p48 (eIF3e) FEBS Letters. 2002;514:49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mack DL, Boulanger CA, Callahan R, Smith GH. Expression of truncted Int6/eIF3e in mammary alveolar epithelium leads to persistent hyperplasia and tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R42. doi: 10.1186/bcr1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiyoshi Y, Clayton J, Phan L, Yamamoto M, Hinnebusch AG, Watanabe Y, Asano K. Fission yeast homolog of murine Int-6 protein, encoded by mouse mammary tumor virus integration site, is associated with the conserved core subunits of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10056–10062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou C, Arslan F, Wee S, Krishnan S, Ivanov AR, Oliva A, Leatherwood J, Wolf DA. PCI proteins eIF3e and eIF3m define distinct translation initiation factor 3 complexes. BMC Biol. 2005;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sha Z, Brill LM, Cabrera R, Kleifeld O, Scheliga JS, Glickman MH, Chang EC, Wolf DA. The eIF3 Interactome reveals the translasome, a supercomplex linking protein synthesis and degradation machineries. Mol Cell. 2009;36:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeFebvre AK, Korneeva NL, Trutschl M, Cvek U, Duzan RD, Bradley CA, Hershey JWB, Rhoads RE. Translation initiation factor eIF4G-1 binds to eIF3 through the eIF3e subunit. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22917–22932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605418200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masutani M, Sonenberg N, Yokoyama S, Imataka H. Reconstitution reveals the functional core of mammalian eIF3. EMBO J. 2007;26:3373–3383. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueda M, Kinoshita H, Yoshida T, Kamasawa N, Osumi M, Tanaka A. Effect of catalase-specific inhibitor 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole on yeast peroxisomal catalase in vivo. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;219:93–98. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)01201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanoh J, Watanabe Y, Ohsugi M, Iino Y, Yamamoto M. Schizosaccharomyces pombe gad7+ encodes a phosphorpotein with a bZIP domain, which is required for proper G1 arreset and gene expression under nitrogen starvation. Genes Cells. 1996;1:391–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sansó M, Gogol M, Ayté J, Seidel C, Hidalgo E. Transcription factors Pcr1 and Atf1 have distinct roles in stress- and Sty1-dependent gene regulation. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:826–835. doi: 10.1128/EC.00465-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohmiya R, Yamada H, Nakashima K, Aiba H, Mizuno T. Osmoregulation of fission yeast: cloning of two distinc genes encoding glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, one of which is responsible for osmotolerance for growth. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:963–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morigasaki S, Shimada K, Ikner A, Yanagida M, Shiozaki K. Glycolytic enzyme GAPDH promotes peroxide stress signaling through multistep phosphorelay to a MAPK cascade. Mol Cell. 2008;30:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tvegård T, Soltani H, Skjølberg HC, Krohn M, Nilssen EA, Kearsey SE, Grallert B, Boye E. A novel checkpoint mechanism regulating the G1/S transition. Genes Dev. 2007;21:649–654. doi: 10.1101/gad.421807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiozaki K, Russell P. Cell-cycle control linked to extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature. 1995;378:739–743. doi: 10.1038/378739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirota K, Hasemi T, Yamada T, Mizuno Ki, Hoffman CS, Shibata T, Ohta K. Fission yeast global repressors regulate the specificity of chromatin alteration in response to distinct environmental stresses. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:855–862. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung WH, Kim KD, Roe JH. Localization and function of three monothiol glutaredoxins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deshpande GP, Hayles J, Hoe KL, Kim DU, Park HO, Hartsuiker E. Screening a genome wide S. pombe deletion library identifies novel genes and pathways involved in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair. 2009;8:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaur J, Bachhawat AK. Ycy1p, a novel, high-affinity, cysteine-specific transporter from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevsiae. Genetics. 2007;176:877–890. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oxelmark E, Marchini A, Malanchi I, Magherini F, Jaquet L, Hajibagheri MA, Blight KJ, Jauniaux JC, Tommasino M. Mmf1p, a novel yeast mitochondrial protein conserved throughout evolution and involved in maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7784–7797. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7784-7797.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kispal G, Csere P, Prohl C, Lill R. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 1999;14:3981–3989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen D, Wilkinson CRM, Watt S, Penkett CJ, Toone WM, Jones N, Bähler J. Multiple Pathways Differentially Regulate Global Oxidative Stress Responses in Fission Yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:308–317. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunand-Sauthier I, Walker CA, Narashimhan J, Pearce AK, Wek RC, Humphrey TC. Stress-activated protein kinase pathway functions to support protein synthesis and translational adaptation in response to environmental stress in fission yeast. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1785–1793. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1785-1793.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukuzawa K, Fujisaki A, Akai K, Tokumura A, Terao J, Gebicki JM. Measurement of phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides in solution and in intact membranes by the ferric-xylenol orange assay. Anal Biochem. 2006;359:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell A, Romano GH, Groisman B, Yona A, Dekel E, Kupiec M, Dahan O, Pilpel Y. Adaptive prediction of environmental changes by microorganisms. Nature. 2009;460:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature08112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiozaki K, Shiozaki M, Russell P. Mcs4 mitotic catastrophe suppressor regulates te fission yeast cell cycle through the Wik1-Wis1-spc1 kinase cascade. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:409–419. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilhelm B, Marguerat S, Watt S, Schubert F, Wood V, Goodhead I, Penkett CJ, Rogers J, Bähler J. Dynamic repertoire of a eukaryotic transcriptome surveyed at single-nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2008;453:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature07002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asano K, Vornlocher HP, Richter-Cook NJ, Merrick WC, Hinnebusch AG, Hershey JWB. Structure of cDNAs encoding human eukaryotic initiation factor 3 subunits: possible roles in RNA binding and macromolecular assembly. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27042–27052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou M, Sandercock AM, Fraser CS, Ridlova G, Stephens E, Schenauer MR, Yokoi-Fong T, Barsky D, Leary JA, Hershey JWB, Doudna JA, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry reveals modularity and a complete subunit interaction map of the eukaryotic translation factor eIF3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18139–18144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801313105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takemaru K, Harashima S, Ueda H, Hirose S. Yeast coactivator MBF1 mediates GCN4-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4971–4976. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cherkasova VA, Hinnebusch AG. Translational control by TOR and TAP42 through dephosphorylation of eIF2 kinase GCN2. Genes Dev. 2003;17:859–872. doi: 10.1101/gad.1069003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staschke KA, Dey S, Zaborske JM, Palam LR, McClintick JN, Pan T, Edenberg HJ, Wek RC. Integration of general amino acid control and TOR regulatory pathways in nitrogen assimilation in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16893–16911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petersen J, Nurse P. TOR signalling regulates mitotic commitment through the stress MAP kinase pathway and the Polo and Cdc2 kinases. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thiaville MM, Pan YX, Gjymishka A, Zhong C, Kaufman RJ, Kilberg MS. MEK signaling is required for phosphorylation of eIF2α following amino acid limitation of HepG2 human hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10848–10857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708320200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kennedy NJ, Cellurale C, Davis RJ. A radical role for p38 MAPK in tumor initiation. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dolado I, Swat A, Ajenjo N, De Vita G, Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. p38α MAP kinase as a sensor of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiozaki K, Shiozaki M, Russell P. Heat stress activates fission yeast Spc1/Sty1 MAPK by a MEKK-independent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1339–1349. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]