Abstract

Allele sharing between modern and archaic hominin genomes has been variously interpreted to have originated from ancestral genetic structure or through non-African introgression from archaic hominins. However, evolution of polymorphic human deletions that are shared with archaic hominin genomes has yet to be studied. We identified 427 polymorphic human deletions that are shared with archaic hominin genomes, approximately 87% of which originated before the Human–Neandertal divergence (ancient) and only approximately 9% of which have been introgressed from Neandertals (introgressed). Recurrence, incomplete lineage sorting between human and chimp lineages, and hominid-specific insertions constitute the remaining approximately 4% of allele sharing between humans and archaic hominins. We observed that ancient deletions correspond to more than 13% of all common (>5% allele frequency) deletion variation among modern humans. Our analyses indicate that the genomic landscapes of both ancient and introgressed deletion variants were primarily shaped by purifying selection, eliminating large and exonic variants. We found 17 exonic deletions that are shared with archaic hominin genomes, including those leading to three fusion transcripts. The affected genes are involved in metabolism of external and internal compounds, growth and sperm formation, as well as susceptibility to psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Our analyses suggest that these “exonic” deletion variants have evolved through different adaptive forces, including balancing and population-specific positive selection. Our findings reveal that genomic structural variants that are shared between humans and archaic hominin genomes are common among modern humans and can influence biomedically and evolutionarily important phenotypes.

Keywords: Neandertal, Denisovan, copy number variation (CNV), DMBT1, LCE3C, GHR, ACOT1, GSTT1

Introduction

The release of ancient Neandertal and Denisovan genomes allowed us to study the relationship between genomes of ancient hominids and modern humans. Neandertal and Denisovan genomes are more closely related to each other than they are to modern human genomes and they diverged from modern human ancestors approximately 500,000 years ago (Prüfer et al. 2014). Recent studies have shown that archaic hominins, including but not limited to Neandertals and Denisovans, contributed genetic material to modern humans (Veeramah and Hammer 2014). The origin and impact of these introgressions vary geographically and involve different species (Green et al. 2010; Reich et al. 2010; Hammer et al. 2011; Lazaridis et al. 2013). The exact timing and geographical origin of these introgressions have been the focus of several recent studies (Green et al. 2010; Currat and Excoffier 2011; Wall et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2014). In 2014, two studies documented the genome-wide distribution of Neandertal alleles across modern human genomes (Sankararaman et al. 2014; Vernot and Akey 2014). These studies found that regions in modern human genomes that carry Neandertal introgressed sequences overlap with genes less than expected by chance. This implies that purifying (i.e., negative selection against deleterious phenotypes) removed some Neandertal alleles after the introgression event.

Archaic admixture is not the only source of ancient variation in human genome. Previous studies identified highly divergent haplotypes in the human genome, potentially indicating the presence of ancient structure in Africa that has been maintained since before the expected coalescent date for modern human genetic variation (e.g., Barreiro et al. 2005; Cagliani et al. 2008; Teixeira et al. 2014). One hypothesis for preservation of these haplotypes is that they may have been under polymorphism-conserving balancing selection (e.g., heterozygote adaptive fitness advantage).

Genomic structural variants, that is, deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations of genomic segments, have recently been recognized as a major part of human genomic variation (Conrad et al. 2009). It has been an ongoing challenge to discover and genotype genomic structural variants (Alkan et al. 2011). However, in the last 5 years, there has been major progress in discovery and genotyping of deletion polymorphisms (1000 Genomes Project Consortium 2012).

We previously described a common deletion polymorphism in modern humans that is shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes (Gokcumen et al. 2013). We reasoned that this deletion has evolved before Human–Neandertal/Denisovan divergence in Africa and has been maintained through balancing selection. Herein, we extend our analyses to the entire genome to identify deletion variants observed among modern humans that are shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes.

Results

Identification of Polymorphic Human Deletions that Are Shared with Archaic Hominins

To identify the deletion polymorphisms that are also present in the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, we started with high-confidence deletion polymorphisms documented by the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 1 data release (1000 Genomes Project Consortium 2012). Briefly, this data set (referred to as “1KG deletions”) includes 14,422 deletion polymorphisms detected among 1,092 human genomes across 14 populations. The deletions were identified by comparing genome resequencing data to the human reference genome (Hg19) and to each other using multiple discovery tools. Furthermore, the breakpoints of these polymorphisms are well characterized, and an extensive validation effort was made to ensure the accuracy of these deletion polymorphisms (see 1000 Genomes Project Consortium 2012). It is important to note that because of the emphasis on accuracy, most complex regions of the genome (e.g., telomeric regions) that could lead to false-positive genotyping may be underrepresented in 1KG deletions. As such, this data set provides an accurate and straightforward starting point for genotyping polymorphic human deletions in Neandertal and Denisovan genomes.

Recent Neandertal (Prüfer et al. 2014) and Denisovan (Meyer et al. 2012) sequences provide high-depth coverage (∼30×) aligned to the human reference genome, the same assembly against which 1KG deletions were compiled. As such, to detect human deletion variants that are shared with archaic hominins, we simply “genotyped” the 1KG deletions using read-depth data from high-coverage Neandertal and Denisovan genomes. Briefly, we calculated the number of Denisovan and Neandertal reads mapping to a given interval in the human reference genome where a deletion polymorphism was previously detected among modern humans. As expected the number of reads of these regions correlate well with size for both Neandertal and Denisovan sequences (R2 = 0.8582 and 0.8713, respectively). However, there are intervals with obviously less than expected read depth as compared with their size (supplementary fig. S1A and B, Supplementary Material online). These outliers suggest potential deletions in the available archaic genomes.

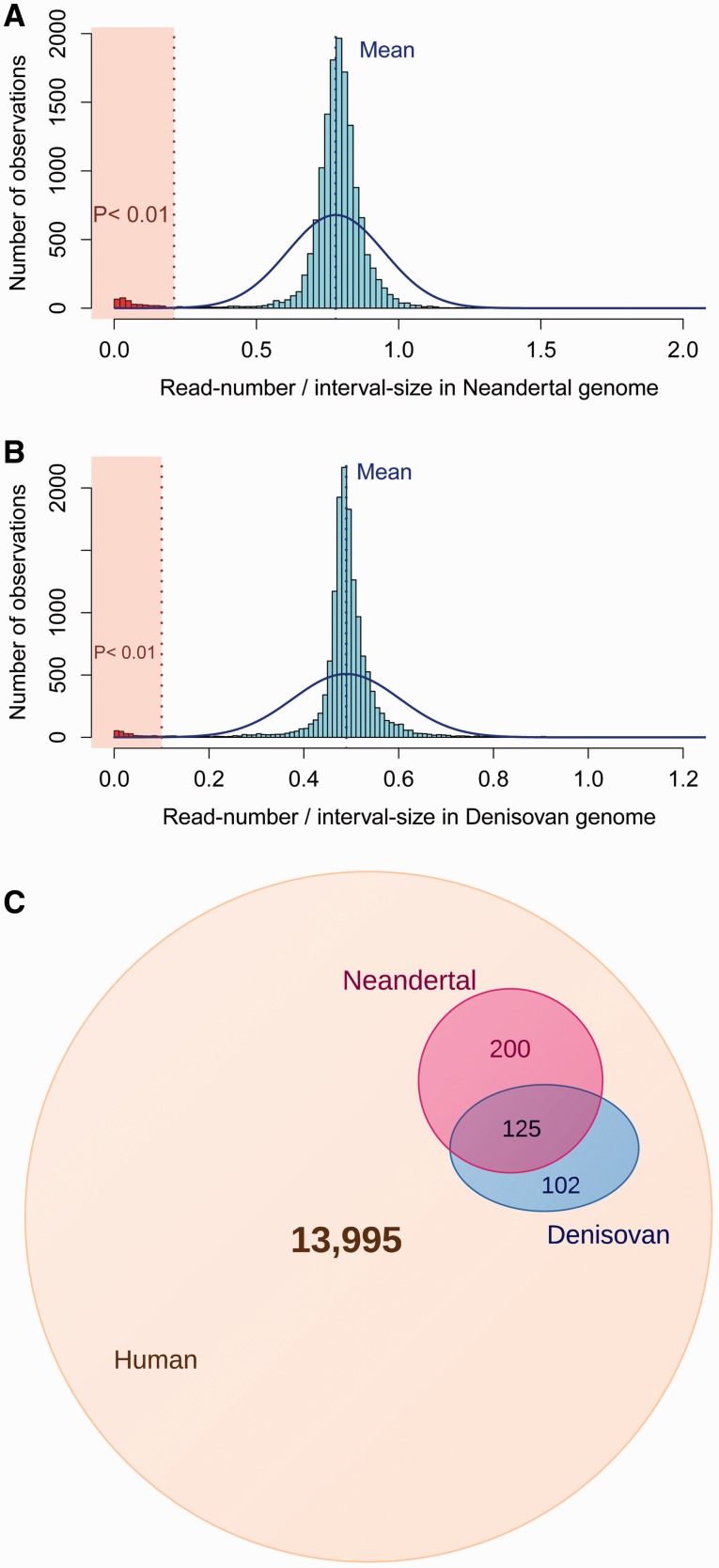

To rigorously identify these outliers, we assumed that the read-depth/size ratio in Neandertal and Denisovan genomes across these intervals follows a normal distribution (fig. 1A and B) with the observed mean and standard deviation. We then identify outliers that do not fit into this distribution (P < 0.01). Using this conservative estimate, we identified 325 and 227 polymorphic 1KG deletions that are shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Identification of deletions shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes. (A) We counted the number of Neandertal sequence reads mapping to the genomic intervals where the human deletions were reported by 1000 Genomes Project. The histogram shows on the x axis the distribution of number of reads in each interval divided by the size of the interval and on the y axis the frequency of the intervals observed. The dotted blue vertical line indicates the mean of this distribution. The solid blue line shows the normal distribution with the mean and the standard deviation of the observed distribution. The dotted red vertical line indicates the read-depth/size ratio, where the probability of observing a smaller ratio under normal distribution is 0.01. For the intervals that fall into the red transparent box, the read-depth in Neandertal resequencing is lower than expected by chance/noise, and consequently we assumed that these are deleted in the Neandertal genome. These deletions were indicated by red histogram bars. (B) The read depth/size ratio distribution analysis for the Denisovan genome. (C) Venn diagram showing the number of human deletions that are found only in humans (light brown), shared with Neandertal genome (pink), shared with Denisovan genome (blue), or shared with both (purple).

To ensure the accuracy of our genotyping pipeline, we conducted multiple checks. First, to avoid any GC bias that may affect mapping, we investigated the GC content of all the human deletions and those that we found to be shared with archaic hominins. We found no significant difference (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). Second, we have manually checked all calls in both the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes using Integrative Genome Browser (Nicol et al. 2009) (e.g., supplementary fig. S3A, Supplementary Material online). Third, we were also able to take advantage of recently published exome sequences of three Neandertal genomes (including the Altai Neandertal used in this study) to verify the presence of 16 exonic deletions in other Neandertal genomes (supplementary fig. S3B, Supplementary Material online). These exome sequences also verified the accuracy of our observation for one human deletion that we found to be deleted in Denisovan, but not in Altai Neandertal genome.

Last but not least, we used the software SPLITREAD (http://splitread.sourceforge.net/, last accessed December 10, 2014) to remap Neandertal and Denisovan reads to junctions of the deletion breakpoints as defined in 1KG deletion data set (supplementary fig. S3C and table S1, Supplementary Material online). We were able to provide strong split-read support for all of the 220 nonrecurrent deletions we observed in Denisovan genome (please see below for discussion of the recurrent, ancient, and introgressed deletions), with at least 20 reads mapping to the breakpoint junctions. Potentially due to differences in sequence lengths and whole-genome amplification artifacts, Neandertal sequences performed worse than Denisovan sequences for this analysis, with overall distribution of number of split-reads, are an order of magnitude smaller than those observed for Denisovans. Even then, we were able to show that at least two split-reads overlap the breakpoint junctions for approximately 89% (280 of 315) of the nonrecurrent Neandertal deletions. Note that we found strong split-read support from Denisovan reads for all of the 123 nonrecurrent deletions that we found in both Neandertal and Denisovans. Based on these observations, we argue that the reduced split-read support from Neandertals is due to lower power, rather than false positives in our deletion data set. Regardless, we were able to provide split-read support either from Neandertals or Denisovans for approximately 95% of the nonrecurrent deletions.

To further quantify our accuracy, we applied the same procedure for genotyping deletions on a set of random intervals that match the size distribution of 1KG deletion data set. Based on this analysis, we found seven Neandertal and nine Denisovan deletions, corresponding to a false discovery rate of 0.02 and 0.04 for Neandertal and Denisovan deletions, respectively. Overall, we conservatively estimate that at least 427 (∼3%) of all polymorphic human deletions are shared with either Neandertals and Denisovans or both (fig. 1C).

Ancient Genetic Structure, not Introgression, Explains the Majority of Polymorphic Deletions among Humans that Are Shared with Archaic Hominins

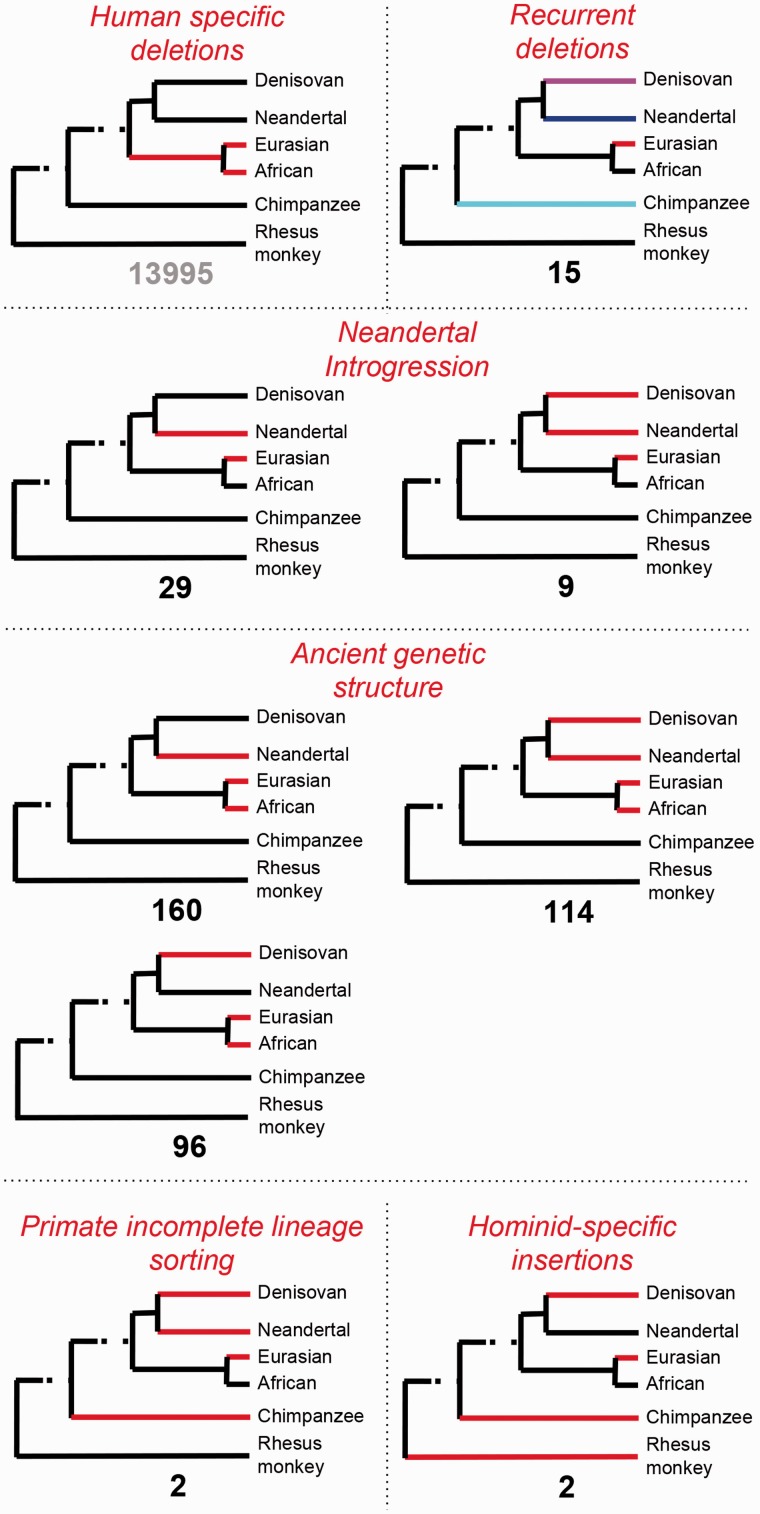

We considered several scenarios to explain the origins of polymorphic deletions among modern humans with respect to the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes (fig. 2). For the majority of human deletions, we found no evidence of allele sharing with archaic hominins. We will refer to these as “human-specific deletions.” It is important to note that our genotyping strategy in archaic hominin genomes is highly conservative and would not be able to pick up deletions that varied among archaic hominins at low frequencies. As such, the human-specific deletion data set may include several variants that are actually shared with other hominin genomes. First, we considered recurrence of the deletion polymorphisms in humans, Neandertals and/or Denisovans. Under this scenario, we expect that the breakpoints of the deletions differ between species. Indeed, we found evidence for 15 recurrent deletions in our manual inspection for different breakpoints (e.g., supplementary fig. S3D, Supplementary Material online), explaining approximately 3.5% of the deletions shared with archaic human genomes. We will refer to these deletions as “recurrent deletions.” With the high-quality Denisovan split-read support, we found no evidence for similar, but not exact breakpoints that we missed in our manual inspection. It is unlikely, but still possible for the deletions to be recurrent even if they share exact breakpoints. The 1KG deletion data set was compiled with accuracy as a main priority. As such, evolutionarily complex regions of the genome that show high levels of recurrence (e.g., Gokcumen et al. 2011) may have been underrepresented and further studies may uncover important recurrent deletions in these regions. Therefore, our estimate of 15 recurrent events is a lower bound for the recurrence of deletions among Human/Neandertal lineage.

Fig. 2.

Possible evolutionary scenarios explaining allele sharing (or lack thereof) between modern and archaic hominins. This figure shows possible evolutionary scenarios, in the form of cartoon phylogenetic trees, explaining the deletion polymorphisms across different lineages. Red color designates branches where the deletion was observed. The number shown under each tree is the number of polymorphic deletions corresponding to the observation. The red headers indicate the likely mechanisms, which were separated from each other by dotted lines, through which the allele sharing has evolved. The “human-specific deletion” scenario covers polymorphic deletions which are shared neither with Neandertal nor with Denisovan genomes. The “recurrent” scenario covers Neandertal- or Denisovan-shared human deletions, breakpoints of which vary among different lineages. The “Neandertal introgression” scenario indicates allele sharing due to Neandertal gene flow into non-African human populations. The “ancient genetic structure” scenario indicates deletions that were evolved in the Human–Neandertal ancestral population and have been maintained since then. The “primate incomplete lineage sorting” scenario indicates deletion polymorphisms that have potentially been maintained since before the Human–Chimpanzee divergence. The “hominid-specific insertion” scenario covers polymorphic deletions that are genotyped as deletions in chimpanzee and rhesus monkey, and show polymorphism in hominid genomes. This scenario represents likely novel sequences that evolved in the ancestral population of Neandertals and humans.

Second, we considered the possibility that these deletion polymorphisms may actually be hominid-specific sequences (e.g., novel insertions or duplications) that evolved in the modern human lineage and remain polymorphic within the species. Under this scenario, these regions then should be observed as deletions in nonhuman outgroups, including chimpanzees and rhesus macaques. We found only two regions that may fit this pattern, as all other deletion regions that we have investigated had an orthologous sequence in chimpanzee or rhesus macaque reference genomes (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). In addition, we found two deletions, for which rhesus macaque but not the chimpanzee reference genome has an orthologous sequence. The most likely explanation of this is incomplete lineage sorting in human–chimpanzee lineage for these variants (Caswell et al. 2008). Albeit interesting, deletions that are explained by these two scenarios constitute less than 1% of the deletions that are shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes and will be referred to as the “other deletions.”

Third, we considered previously reported introgression from Neandertals into ancestors of modern Eurasians as a potential source of the observed allele sharing. Under this scenario, the Neandertals contributed genetic material to ancestors of all non-African populations. One challenge was that we could not merely depend on the frequency distribution of deletions in African and non-Eurasian populations to distinguish an introgression scenario from the ancient structure scenario. The frequency distribution of any genetic variant is highly susceptible to drift and recent migrations. As such, we further evaluated the overlap of deletion polymorphisms with Neandertal-introgressed regions that were identified based on single-nucleotide variation-based haplotype construction (Vernot and Akey 2014). Overall, we expect that 1) most polymorphic deletions that introgressed from Neandertals would have breakpoints precisely shared between the Neandertal genome and modern human deletions (i.e., nonrecurrent), 2) the chimpanzee genome will have the sequence that is deleted in the human genome, 3) these deletions fall into previously reported regions where introgression was detected (Vernot and Akey 2014), 4) such deletions do not exist or have lower frequency in Africa as compared with Eurasia, and 5) if they exist in Africa, the haplotypes that carry them have lower nucleotide diversity than Eurasian haplotypes carrying the deletions. As Denisovans contributed genetic materials mostly to the Melanesian populations (Skoglund and Jakobsson 2011; but see for low level Denisovan ancestry in Asia Huerta-Sánchez et al. 2014), we only assumed Neandertal introgression for the present purpose as 1KG deletions do not include Melanesians. In summary, we found that 38 (∼9%) of human deletions that are shared with archaic hominin genomes can be explained by Neandertal introgression. We will refer to these as “introgressed deletions” from now on.

To independently estimate potential miscategorization of low-frequency ancient deletions as introgressed, we used the polymorphic human deletions that are shared with the Denisovan genome, but not with the Neandertal genome. As 1KG deletions do not include sample from Melanesian or any other South East Asian populations, which were reported to have Denisovan introgression, we expect no Denisovan introgression in the 1KG deletions. As such, the proportion of polymorphic deletions that are shared with only Denisovans and categorized as “introgressed” with our pipeline will give us an indirect estimate of miscategorization. Based on this, we estimate that only 5 of 102 deletions to be miscategorized as introgressed with our pipeline.

Fourth, we considered the scenario where the age of polymorphic deletion variants we observed in humans actually predates the Human–Neandertal divergence. It has been argued previously that some of the ancient variation that exists in the Human–Neandertal ancestral population has been maintained in humans. As such, the polymorphic deletions among modern humans that also exist in archaic hominins that cannot be explained by introgression should have originated before the Human–Neandertal divergence and been maintained since then in extant humans. Overall, 370 (∼87%) of the polymorphic human deletions that are shared with archaic hominins can be traced back to ancient genetic structure predating Human–Neandertal divergence. We will refer to these as “ancient deletions” from here on.

Our observations, taken as a whole, support the conclusion that the vast majority of allele sharing between humans and archaic hominins affecting deletion variation is due to ancient genetic structure, rather than introgression. In other words, our findings are consistent with the notion that most deletion polymorphisms shared with archaic genomes evolved prior to the Human–Neandertal divergence and have been maintained ever since.

Deletions that Are Shared with Archaic Hominins Constitute More than 13% of Common Deletion Variation in Humans, but Are Smaller and Rarely Overlap with Functional Regions of the Genome

We found that the allele frequencies of the deletion variants that are shared with archaic hominin genomes are significantly higher than human-specific deletion variants (P < 2.2 × 10−16, Wilcoxon rank test; fig. 3B and supplementary fig. S4A, Supplementary Material online). We also found that the deletions that we detected in both Neandertal and Denisovan genomes have significantly higher frequency in humans than those we detected only in one of the archaic hominin genomes (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank test). Although ancient deletion variants correspond to only 2.5% of “all” polymorphic human deletions, they constitute approximately 13% of all “common” (allele frequency >5%) deletion polymorphisms reported among 1KG deletions.

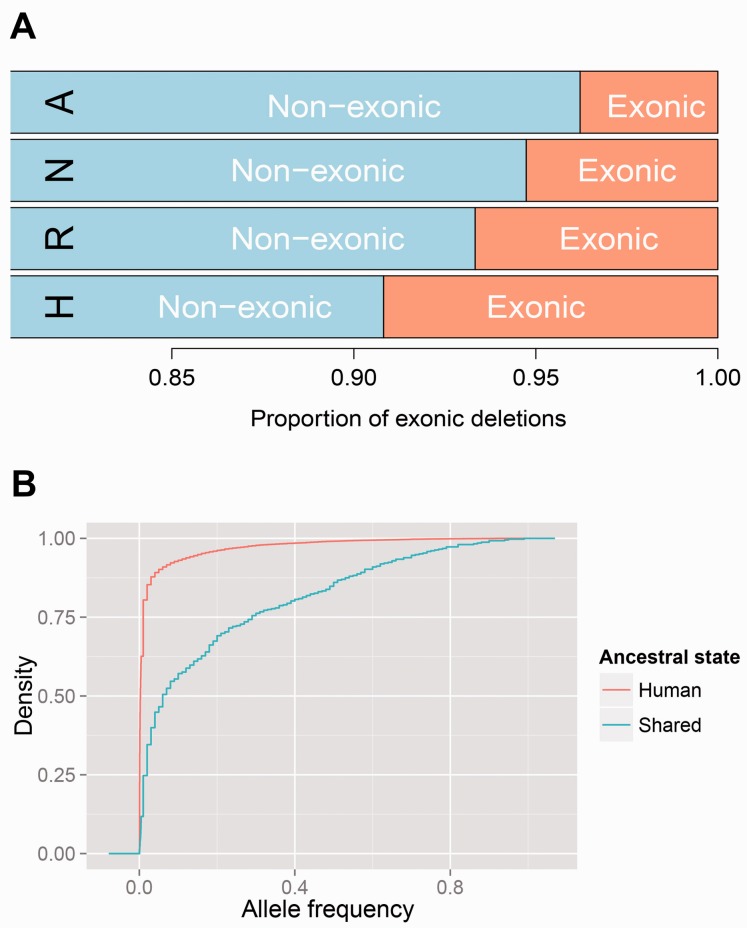

Fig. 3.

Characterization of ancient deletion variants. (A) This figure shows the proportions of Neandertal introgressed deletions, maintained ancient deletions, recurrent deletions, and human-specific deletions that overlap with exonic regions. H, human-specific deletions; R, recurrent deletions; A, deletions maintained from ancient genetic structure; N, Neandertal-introgressed deletions. The orange-colored section indicates the fraction of deletions that overlaps with exons. Deletion polymorphisms are known to be depleted for exonic content. However, the ancient deletion variants are even less exonic than human-specific deletion variants (P = 0.0011, Chi-square test). (B) Cumulative fraction plot of allele frequency in modern humans for deletion variants shared with Neandertals and/or Denisovans (Shared—light blue), and human-specific (Human—red) deletions. The x axis indicates the frequency of the deletion variants and y axis indicates the cumulative fraction of the deletions of all the deletions at a given or lower frequency. The steep slope toward the left end of the human-specific deletions curve shows that the majority of these polymorphic deletions have allele frequencies smaller than 0.1. As for deletions common to Neandertals/Denisovans, about 43% of them have allele frequencies over 0.1. Overall, “Shared” deletions are significantly more common than Human-specific deletions (P < 2.2 × 10−16, Wilcoxon rank test).

These observations would imply that the ancestral population that gave rise to the Human, Neandertal, and Denisova lineages harbored a considerable number of common deletion variants that have been inherited by all three species, and remain polymorphic in extant humans. To investigate whether these deletions are also polymorphic in Neandertals, we manually checked 17 exonic deletions that humans and archaic hominins share among recently released exome sequencing data for three Neandertal genomes, including the Altaian individual that we used in this study (Castellano et al. 2014) (supplementary fig. S3B, Supplementary Material online). We verified the 16 regions where we previously observed deletions in the Altai Neandertal whole-genome sequence. Furthermore, we observed that these regions are homozygously deleted in the other two Neandertal genomes as well. The likelihood of not detecting any within species variation across the 16 deleted loci among two additional individuals is infinitesimally small, unless the allele frequencies of these deletions are extremely high (supplementary fig. S4B, Supplementary Material online). As such, we conclude that the majority of shared deletions described in our study are indeed fixed and not necessarily polymorphic within Neandertals. This is probably due to high inbreeding reported for Neandertals (Castellano et al. 2014; Prüfer et al. 2014). Using the same data set, we found no evidence for a deletion in the three Neandertal exomes for one exonic human deletion where we previously observed a deletion in Denisovan, but not for the Altai Neandertal.

Deletion variants have already been shown to be significantly biased away from exonic sequences, indicating the effect of purifying selection (Conrad et al. 2009). We found that the deletions that are shared with archaic genomes have even less overlap with exonic regions in the genome than other deletion variants (P = 0.0004, Chi-square test, fig. 3A). Taking the heterogeneous nature of genome into consideration, we have simulated genomic intervals using a genome structure correction (Bickel et al. 2010). Our results showed approximately 3.4- (P = 0.0003) and 5.3-fold (P = 6.6 × 10−8) depletion of the exonic deletions in ancient and introgressed deletions as compared with random expectation, respectively. We also found that ancient deletions are smaller than human-specific deletions (P < 2.2 × 10−16, Wilcoxon rank test, supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online).

Together, these observations are consistent with recent studies that highlight purifying selection as a major force in shaping the genomic distribution of Neandertal-introgressed single-nucleotide variation in the human genome (Sankararaman et al. 2014; Vernot and Akey 2014). Our results furthered these observations for ancient and introgressed genomic structural variants.

The Majority of Ancient Deletion Polymorphisms Have Evolved under Neutral Conditions

The most likely evolutionary scenario to explain the lack of exonic overlap observed among ancient deletions is that purifying selection eliminated most ancient variation. Then, since before the Human–Neandertal divergence, the deletions that were not affected by the initial filtering through purifying selection evolved largely under neutral conditions. According to this hypothesis, we expect that demographic changes and not selective forces operating on ancient deletions are the main processes that would affect neutrality tests.

Ancient deletions provide an especially interesting case. These variants are by definition old, often older than the variation observed in other parts of the genome. We expect that surrounding haplotypes, depending on the recombination rate in that region, are as old as these ancient deletions. Thus, we expect, under neutrality, to observe higher values for Watterson’s θ estimator (θW) and for Tajima’s θ estimator (measured by the average number of pairwise differences, π) as compared with haplotypes harboring nonancient deletions. Tajima’s D measures the normalized difference between θW and π. Deviations from 0 indicate either nonneutral evolution or demographic changes. Recent expansions generate negative values for Tajima’s D because most of the polymorphisms are recent and are characterized by low allele frequency (Tajima 1989). Human demographic history is characterized by a recent expansion, thus generating negative values for Tajima’s D. However, for old regions surrounding ancient deletions, we expect that Tajima’s D values will be shifted toward higher values as a proportion of polymorphisms will be as old as the region itself.

To test these expectations, we calculated basic population statistics for ancient and nonancient deletions including the 10-kb sequence immediately flanking them. We performed these analyses in sub-Saharan African populations, which have higher effective populations sizes than Eurasian populations and consequently less prone to effects of genetic drift. Our results showed that regions harboring ancient deletion variants indeed yield significantly higher θ and π values as compared with regions harboring nonancient deletions (P < 10−4 for both measures for both YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria) and LWK (Luhya in Webuye, Kenya) populations, Student’s t-test, supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). This observation is consistent with older coalescent times for regions harboring ancient deletions. Our analysis also showed that Tajima’s D values for regions harboring ancient deletions do not significantly deviate from zero with means of −0.14 and −0.31 for YRI and LWK, respectively. However, these regions have significantly less negative Tajima’s D values, when compared with regions harboring nonancient deletions (P < 10−5, one-tail Student’s t-test for both YRI and LWK, supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). The most plausible explanation for this observation is that regions harboring ancient deletions have been affected to a lesser extent by recent human demography than other genomic regions with a more recent common ancestor. Most of the genomic regions contain polymorphisms affected by the joint effect of bottleneck and recent expansion. These regions in African populations will be characterized by slightly negative Tajima’s D as previously shown (e.g., Garrigan and Hammer 2006). On the other hand, we observed that polymorphisms on old regions surrounding ancient deletions are characterized by significantly greater values of Tajima’s D. These observations are consistent with the scenario that the majority of ancient deletions and their surrounding haplotypes are indeed older than the genome-wide average and were not subject to major adaptive pressures.

Identifying Potentially Adaptive Ancient Deletions among the Exonic Deletions

As mentioned above, deletions that are shared with archaic hominins are depleted for exonic sequences, indicating the effect of purifying selection. However, we found 17 instances where these deletions overlap with exonic sequences (table 1 and fig. 4A–C). We reasoned that these exonic deletions, which lead to whole gene deletions, fusion transcripts and loss-of-function alleles, are unlikely to evolve under neutrality in contrast to other, nonexonic ancient alleles.

Table 1.

List of Exonic Deletions Shared with Archaic Hominin Genomes.

| Chromosome | Start | End | Gene | Comment | Ancestral State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr11 | 60,228,164 | 60,229,386 | MS4A1 | UTR | Introgressed |

| chr1 | 213,002,368 | 213,013,665 | SPATA45 | Loss-of-function | Introgressed |

| chr13 | 20,077,974 | 20,080,405 | TPTE2 | UTR | Ancient |

| chr17 | 79,285,360 | 79,286,612 | TMEM105 | UTR | Ancient |

| chr19 | 41,355,733 | 41,387,636 | CYP2A6, CYP2A7 | Fusion | Ancient |

| chr10 | 124,369,735 | 124,377,838 | DMBT1 | Partial-CDS | Recurrent |

| chr11 | 3,238,738 | 3,244,086 | MRGPRG | UTR | Ancient |

| chr8 | 144,634,064 | 144,636,239 | GSDMD | UTR | Ancient |

| chr15 | 25,436,588 | 25,438,493 | SNORD115-12, SNORD115-13 | Fusion | Ancient |

| chr12 | 27,648,142 | 27,655,163 | SMCO2 | Partial-CDS | Ancient |

| chr11 | 128,682,716 | 128,683,410 | FLI1 | UTR | Ancient |

| chr7 | 99,461,389 | 99,463,562 | CYP3A43 | UTR | Ancient |

| chr14 | 73,997,051 | 74,024,450 | ACOT1 | Loss-of-function | Ancient |

| chr4 | 70,124,301 | 70,230,600 | UGT2B28 | Loss-of-function | Ancient |

| chr1 | 152,555,542 | 152,587,742 | LCE3C | Loss-of-function | Ancient |

| chr5 | 42,628,311 | 42,630,990 | GHR | Partial-CDS | Ancient |

| chr22 | 24,343,050 | 24,397,301 | GSTTP1, GSTT1 | Fusion | Ancient |

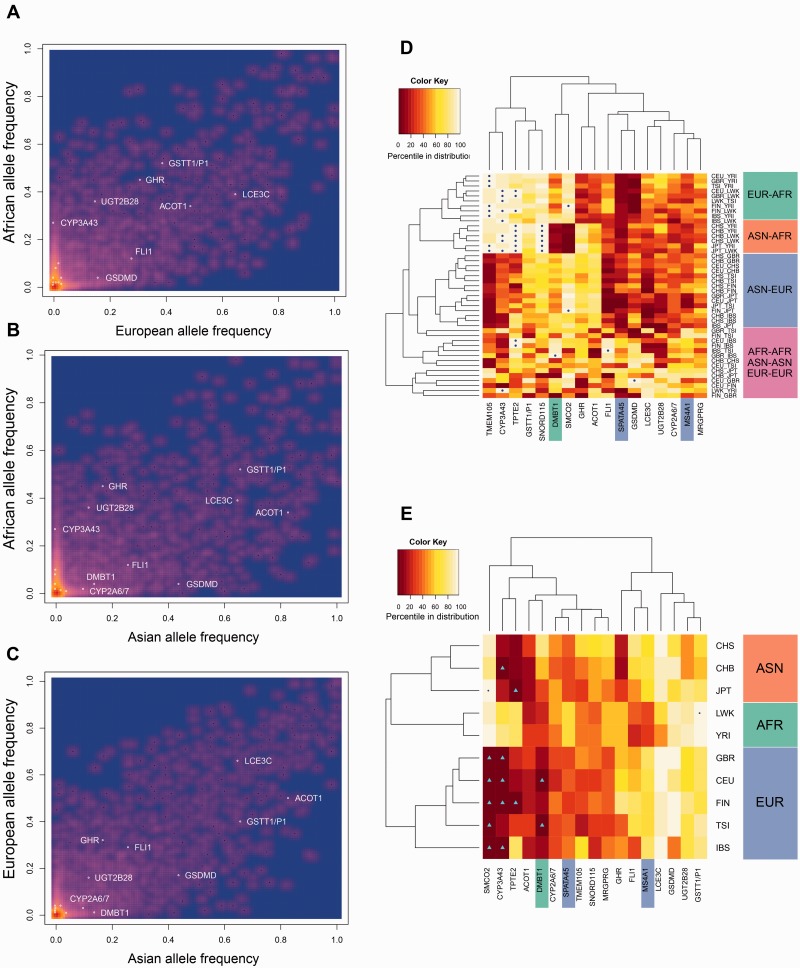

Fig. 4.

Analysis of exonic variants. (A–C) The allele frequency of exonic deletion variants. The x- and y axes indicate the allele frequencies in a given continent. The heatmap colors represent number of observations. The red to dark blue gradient corresponds to decreased density of observed deletions. Here, we plot allele frequencies of all 14,422 1KG deletion variants. As such, red spots designate thousands of observations decreasing to hundreds of observations for yellow pixels and single observations for purple dots. A vast majority of deletions have very low allele frequencies. The exonic variants shared with Neandertal/Denisovan genomes are shown with white-colored circles. (D) Heatmap of the percentiles of pairwise FST values measured for the flanking regions of the ancient exonic deletion variants between ten nonadmixed populations using clustering without a priori input. The colors in the heatmap correspond to the percentile of the FST values as compared with the distribution of all exonic human deletions, with light-yellow/white being the highest values observed (1 indicating the highest percentile) and dark red corresponding to lower values (0 indicating the lowest possible percentile). Exact values to generate this map can be found in supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online. On the x axis are the exonic deletion variants, represented by the names of the genes that they affect. The ones highlighted in blue are introgressed deletions, the one highlighted in green is a recurrent deletion, and those that are not highlighted are ancient deletions. On y axis are population pairs used in the analysis. AFR, African; ASN, Asian; EUR, European; CEU, Utah residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European ancestry; CHB, Han Chinese in Beijing; CHS, Southern Han Chinese; FIN, Finish in Finland; GBR, British in England and Scotland; IBS, Iberian population in Spain; JPT, Japanese in Tokyo; LWK, Luhya in Webuye, Kenya; TSI, Toscani in Italia; YRI, Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria. (E) Heatmap of the percentiles of Tajima’s D values observed for ancient exonic deletion variants within the Tajima’s D distribution of all exonic human deletions. The colors in the heatmap correspond to the percentile of the Tajima’s D values as compared with Tajima’s D values calculated for all exonic human deletions, with light-yellow/white being the highest values observed (1 indicating the highest percentile) and dark red corresponding to lower values (0 indicating the lowest possible percentile). Exact values to generate this map can be found in supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online. On the x axis are the exonic deletion variants, represented by the names of the genes that they affect. The ones highlighted in blue are introgressed deletions, the one highlighted in green is a recurrent deletion, and those that are not highlighted are ancient deletions. On the y axis are the populations for which Tajima’s D values were measured. The population designations can be found above, in the legend of figure 4D.

To further investigate the evolution of these exonic deletions, we calculated population differentiation based on the variations in allele frequency within and among populations (FST) (Hudson et al. 1992) for all 1000 Genomes deletions (fig. 4D). We also used polymorphisms immediately upstream regions of these deletions to calculate Tajima’s D (Tajima 1989) (fig. 4E). We then analyzed the human exonic deletions that are shared with Neandertals or Denisovans within the context of all polymorphic human exonic deletions across the genome.

Our analysis highlighted several highly interesting exonic loci (e.g., supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online) and below we will discuss several of these genes individually. However, it is important to note that 1) demographic expansions and bottlenecks introduce high levels of noise, increasing the threshold for significance (e.g., false negatives for detecting balancing selection), 2) recombination that broke the haplotypes between the deletions and flanking regions may have introduced noise into our calculations (e.g., by decreasing otherwise higher Tajima’s D), and 3) that there are multiple (e.g., in contrast to a single external pressure) and complex (e.g., dependent on time, geography, frequency in population, etc.) evolutionary forces that complicate the interpretation of both FST and Tajima’s D.

Ancient and Introgressed Exonic, Loss-of-Function Deletions Are Associated with Xenobiotic and Lipid Metabolism, Psoriasis, and Spermatogenesis

We found that four of the nonrecurrent exonic deletions that are shared with archaic hominin genomes likely lead to loss-of-function alleles, where either the entire gene or entire coding sequences were deleted (table 1). One such deletion overlaps with the LCE3C gene, which has been strongly associated with psoriasis (de Cid et al. 2009). The allele frequency of LCE3C gene deletion is extremely high among Eurasians, reaching to over 70% allele frequency in some European and Asian populations (fig. 4A–C). We found consistently positive Tajima’s D values across all eight nonadmixed Eurasian populations analyzed as calculated for the variation in the region harboring the deletion (fig. 4E). When compared with other exonic human deletions, the Tajima’s D values reach to 95th percentile in five populations. In contrast, differentiation as measured by FST between continental populations shows relatively low overall differentiation between continental populations as compared with other exonic deletion variants in humans (fig. 4D). Positive Tajima’s D values and low population differentiation are hallmarks of classical balancing selection (e.g., Cagliani et al. 2008). This observation, in parallel with our understanding that this deletion has been maintained in high allele frequencies since before Human–Neandertal divergence, is consistent with balancing selection acting on the LCE3C deletion variant.

The UGT2B genes comprise evolutionary dynamic genes that are involved in metabolism of external and internal compounds, including several hormones and steroids. Adaptive deletion variants have already been reported for some members of this family, including deletion of UGT2B17 gene (Xue et al. 2008). Moreover, UGT2B17 and UGT2B28, both of which are involved in steroid metabolism, have been found to be commonly deleted and the functional impact of these deletions may have cumulative effects (Ménard et al. 2009). Indeed, we found that the deletion that encompasses UGT2B28 deletion is to be ancient. This deletion is very common in Africa, reaching to almost 40% allele frequency. Similar to what we observed for LCE3C, Tajima’s D was consistently higher than genome-wide distribution for other exonic deletion variants (fig. 4E), whereas FST was consistently low among populations (fig. 4D). These observations are consistent with balancing selection acting on UGT2B28.

Another ancient loss-of-function deletion with very high global frequency overlaps with ACOT1 gene. This gene is involved in lipid biosynthetic pathways and has been argued to play a role in regulation of milk fat synthesis in mammals (Rudolph et al. 2007), which is critical in neonatal development. Interestingly, this whole-gene deletion is shared with the Neandertal genome. The allele frequency of this deletion shows considerable differences between continents, almost reaching fixation among Asian populations, but remains as the minor allele in other continents (fig. 4B and C). Unlike the aforementioned LCE3C and UGT2B28 gene variation, the haplotypic variation around ACOT1 is characterized by consistently negative Tajima’s D values in human populations when compared with values calculated for other exonic human deletions (fig. 4E). However, as expected from high frequency differences, the FST is consistently higher between Asian and non-Asian populations. This finding may indicate ongoing positive selection pressure on the ACOT1 deletion, specifically favoring the deletion allele in Asian populations.

We found that only one of the loss-of-function deletions was introgressed from Neandertals. This deletion includes all of the coding sequences of the spermatogenesis-associated gene SPATA45. Several evolutionarily important phenotypic trends, such as reproductive efficacy and success, responses to sexual selection pressures or apoptotic pathways that regulate sperm selection, are linked to spermatogenesis. As such, the loss of function of SPATA45 due to the introgressed deletion mentioned above is a prime candidate for adaptive forces to acting after introgression from Neandertals. Indeed, Vernot and Akey (2014) described a Neandertal-derived haplotype for the functionally similar gene, SPATA18. Unlike the SPATA18 haplotype however, the deletion variant affecting SPATA45 is relatively rare, found in less than 5% of human genomes.

Incomplete Gene Deletions Lead to Novel Transcripts, Including Gene Fusions

Nine of the 17 exonic deletions shared with archaic hominins overlap with parts of genes. These deletions potentially lead to alternative protein products, rather than deleting the entire coding sequences. One such deletion overlaps with the exon 3 of growth hormone receptor gene (GHR). This well-studied deletion variant leads to a transcript that misses exon 3 (d3). The d3 haplotype was associated with smaller birth size (Sørensen et al. 2010; Padidela et al. 2012). The d3 haplotype was also linked to a 1.7–2 times increase in growth acceleration in children that are treated with growth hormone and, consequently is a major target for pharmacogenomics research (Dos Santos et al. 2004). The allele frequency of this deletion is approximately 44% in Africa, approximately 31% in Europe, but only 17% in Asia. Not surprisingly, the FST between Asian and non-Asian populations is consistently higher than genome-wide average (fig. 4D), potentially indicating geography dependent positive selection similar to ACOT1.

We identified only one recurrent exonic deletion that is shared with archaic hominins overlapping with DMBT1. Unlike the other exonic deletions which are shared among hominin genomes because of common descent or introgression, DMBT1 deletion sharing is most likely due to recurrent deletions in this region. DMBT1 also got somatically deleted in malignant brain tumors and likely contributed to cancer progression (Mollenhauer et al. 1997). Indeed, the region harboring DMBT1 was discussed within the context of genomic instability (Mollenhauer et al. 1999). Based on our results, we can conclude that it is likely that the genomic instability of this genetic region along chromosome 10q has likely been maintained since Human–Neandertal divergence. Moreover, the deletion variant has been associated with Crohn’s disease (Renner et al. 2007). We found that the Tajima’s D calculated based on the haplotypic variation upstream of the DMBT1 deletion is highly negative and in the 5th percentile for two European populations when compared with Tajima’s D values calculated similarly for all human exonic deletions in these populations (fig. 4E). Moreover, a recent comprehensive analysis for balancing selection among human genomes identified DMBT1 as one of the top candidates for balancing selection in both CEU and YRI populations for which the analysis was conducted (DeGiorgio et al. 2014). The low Tajima’s D values and the balancing selection reported recently seem to be in conflict. However, as mentioned before, it is plausible that complex mutational and adaptive mechanisms may have shaped the haplotypes carrying some of the deletion variants, leaving complicated signatures of adaptation. It is safe to argue, based on our results and those of previous publications that DMBT1 deletion variation likely evolved under nonneutral pressures.

One unexpected observation was that three of the ancient deletions led to fusion transcripts, whereby coding sequences of two separate genes are fused. These deletions combine the transcripts of SNORD115-12 and SNORD115-13, as well as CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 genes. Another such deletion variant, which is very common (>35%) in all human populations, fuses GSTT1 and GSTTP1 genes. GSTT1 is also involved in metabolizing external compounds. The haplotype surrounding this gene shows one of the highest Tajima’s D values measured for exonic deletions in humans (fig. 4E). In addition, there is relatively high population differentiation as measured by FST between continental populations, especially between African and Eurasian populations (fig. 4D). This observation may be explained by a scenario similar to that is often put forward for sickle cell trait in malaria-stricken geographies. In essence, the variation that leads to sickle-cell trait has been maintained in the population through geography-specific balancing selection (reviewed in Dean et al. 2002). A similar scenario would explain the extremely high Tajima’s D in African populations observed for GSTT1–GSTTP1 fusion deletion, as well as the high FST values between African and non-African populations observed for this polymorphism.

Conclusion

Deletion variants, the best characterized of all genomic structural variants, have been shown to play an important role in human evolution (McLean et al. 2011). However, the evolutionary role of these variants within species has not been well-established. High-quality sequences and, more importantly, highly improved discovery and genotyping tools primarily developed within the context of the 1000 Genomes Project have recently allowed for study of human deletion variation in a population genetics framework. We used these exciting resources to assess deletion variants in humans that are shared with the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes. In so doing, we were able to 1) identify hundreds of ancient and introgressed deletion variants in humans, 2) investigate deletion variation within their haplotypic backgrounds, and 3) shed light on the evolution of individual deletion variants that may have phenotypic effects. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to document and characterize deletion variation in humans that are shared with Neandertal and Denisovan genomes in a genome-wide context.

Our results suggest that the majority of allele sharing involving deletion variants between modern humans and archaic hominins is due to ancestral structure and, not due to introgression. This observation does not conflict with the recent reports regarding Neandertal and Denisovan introgression to modern humans, but rather highlights a largely unexplored deep ancestry for a considerable portion (∼13%) of common deletion variation in humans. Moreover, the genomic distribution of these variants shows signatures of ancient purifying selection, eliminating all but a few exonic variants. This observation complements similar observations made for deletion variants in general (Mills et al. 2011), and further suggests the potential role of recent, rare deletion variants in detrimental phenotypes and disease (Itsara et al. 2009).

Only a very small percentage (∼4%) of these maintained ancient and introgressed deletions are exonic; however, the genes involved affect evolutionarily relevant phenotypes, such as growth, immunity and metabolism of external and internal compounds. Some of these deletions were also associated with common human diseases, including Crohn’s disease and psoriasis. Exonic deletions are functionally drastic events that are comparable to frameshift, or stop-codon introducing mutations, or if a gene still functions, to multiple nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants. As such, we argue that unlike the majority of ancient deletions, those that overlap with exons that have been maintained since Human–Neandertal divergence are unlikely to have evolved under neutral conditions. Instead, these ancient exonic deletions may have been maintained through a combination of 1) geographically different, potentially frequency-dependent, adaptive forces and 2) balancing selection. We argue that pathways that involve in these important phenotypes are viable targets for some form of complex adaptive selection that helped maintain the genetic structural variation at these loci for hundreds of thousands of years.

Materials and Methods

Genotyping of Neandertal and Denisovan Genomes

We used 1000 Genomes data set Phase 1 data set (http://www.1000genomes.org/data, last accessed December 10, 2014) (1000 Genomes Project Consortium 2012), as well as the high-coverage genome-wide sequencing data for Neandertal (Prüfer et al. 2014) and Denisovan (Meyer et al. 2012) (available at http://cdna.eva.mpg.de, last accessed December 10, 2014) as our main starting point. The sequencing data from both Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, as well as the 1KG deletions are aligned to the same version of the human reference genome (Hg19). As such, we were able to directly measure the number of reads mapping to the intervals where 14,422 polymorphic human deletions were reported. To accomplish this, we used a custom bedtools (http://bedtools.readthedocs.org/, last accessed December 10, 2014) script.

We then constructed a normal distribution of the read-depth (as normalized by size) for Neandertal and Denisovan data set where the mean and standard deviation were equal to the observed mean and standard deviation. We then established a threshold value that corresponds to 0.01 quantile in the normal distribution, below which we assumed the intervals have lower than expected read-depth/size ratio indicating a deletion in the respective genome.

To determine the false discovery rate, we used the shuffleBed function of bedtools to generate a set of 14,422 random intervals that matches the size distribution of 1KG deletions. We then followed the genotyping workflow described above to identify deletions. We found less than ten deletions in those random regions in both Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, indicating that a false discovery rate is essentially lower than 5% for both genomes.

We used a modified version of SPLITREAD approach (http://splitread.sourceforge.net/, last accessed December 10, 2014) to remap the Neandertal and Denisovan reads to the junctions of the breakpoints of deletions as defined in 1KG deletion data set, rather than applying it to the whole genome. Specifically, we extended the deletion breakpoints 50,000 bases to the upstream and downstream to generate out mappable reference contigs. The mappings to these reference contigs were performed using BWA-MEM method (Li and Durbin 2009). The polymerase chain reaction duplicates, identified by the reads that are mapping exactly to the same positions, were removed from the downstream analysis. Due to the fact that short reads are single ended, there is an increased rate of support for the regions that are repetitive or in segmental duplication regions. SPLITREAD method also relies on the consistent mapping of the splits at the breakpoints with base pair resolution. The deletions that are recurrent with different breakpoints are expected to have less support overall. We observed significantly reduced number of split-read mapping with the Neandertal genome sequences as compared with what was observed for Denisovan genome sequences. We think this is due to inherent read-length variation and differential impact of whole-genome amplification between these two genome sequences.

Categorization of the Origin of Deletions that Are Shared with Neandertal and Denisovan Genomes

We assessed all of the 14,422 1KG deletions for their occurrence in different lineages. The occurrence of these deletions in Neandertal and Denisovan genomes was determined by genotyping described above. Introgressed deletions in humans were defined based on allele frequency distribution, overlap with introgressed regions in human genome described by Vernot and Akey (2014). Specifically, we assumed that those deletions that have lower than 0.01 allele frequency in Africa, accommodating a certain level of possible back migration, is Eurasia specific. To determine whether these deletions are present in chimpanzee lineage, we mapped them onto chimpanzee reference genome panTro4 using Liftover tool (available through USCS Genome Browser; Kent et al. 2002) with minimum ratio of bases remap = 0.95. Then, we manually examined those that failed to map using chain and net tracks in USCS genome browser for both chimpanzees and rhesus macaques. The breakpoints of all the Neandertal/Denisovan shared deletions are checked on integrative genome viewer (Nicol et al. 2009) to determine whether they are recurrent.

Exon Content Analysis

We used Galaxy software tools (Goecks et al. 2010) to identify 1KG deletions that overlap with RefSeq exon track (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/, last accessed December 10, 2014). We assessed the significance of the depletion of exonic deletion we observed using Genome Structure Correction software (https://www.encodeproject.org/software/gsc/, last accessed December 10, 2014). Briefly, this software uses a subsampling approach to avoid confounding factors in the localization of genomic elements for which the analysis is being conducted.

Population Genetics Analysis

We calculated Tajima’s D (Tajima 1989) in 10-kb genomic regions located 500 bp upstream each deletion (i.e., the genomic region from 500 to 10,500 bp upstream each deletion). We included the phased deletion variant as a single variant to this analysis. Polymorphic data were downloaded from the 1000 Genomes project (www.1000genomes.org; phase1, v3.20101123). Polymorphic data were converted to FASTA alignments using the human reference genome (hg19). Calculations of FST and Tajima’s D were performed by CoMuStats (http://pop-gen.eu/wordpress/software/comus-coalescent-of-multiple-species, last accessed December 10, 2014). FST (Hudson et al. 1992) was calculated for the total sample as well as for all demes pairs using the allele frequencies of the deletions. We calculated the FST and Tajima’s D values for all exonic sequences. Based on the distribution of these statistics, we calculated the percentile for each of the “shared” exonic deletions and for each “nonadmixed” population. All source codes used for the calculations are available from http://gokcumenlab.org/data-and-codes/ (last accessed December 10, 2014).

Statistical Tests and Graphs

All other statistical tests and graphs were conducted using base statistical and ggplot2 (http://ggplot2.org/, last accessed December 10, 2014) packages available through R statistical environment (http://www.r-project.org/, last accessed December 10, 2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables S1 and S2 and figures S1–S8 are available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online (http://www.mbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Radke, Qihui Zhu, Mehmet Somel, and Rebecca Iskow for helpful discussions and insights that lead to conception of this study. They thank Can Alkan for providing helpful advice on SPLITREAD analysis. They also thank their colleagues at University at Buffalo, especially to Victor Albert for critical readings of previous versions of this manuscript. This study is primarily funded by OG’s start-up funds from University at Buffalo Research Foundation. P.P. was funded by the grant FP7 REGPOT-InnovCrete (Νο. 316223) grant, as well as by the FP7-PEOPLE-2013-IEF EVOGREN (625057). The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with organization regarding to the materials discussed in this article.

References

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkan C, Coe BP, Eichler EE. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:363–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Patin E, Neyrolles O, Cann HM, Gicquel B, Quintana-Murci L. The heritage of pathogen pressures and ancient demography in the human innate-immunity CD209/CD209L region. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:869–886. doi: 10.1086/497613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel PJ, Boley N, Brown JB, Huang H, Zhang NR. Subsampling methods for genomic inference. Ann Appl Stat. 2010;4:1660–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Cagliani R, Fumagalli M, Riva S, Pozzoli U, Comi G, Menozzi G, Bresolin N, Sironi M. The signature of long-standing balancing selection at the human defensin beta-1 promoter. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R143. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano S, Parra G, Sánchez-Quinto FA, Racimo F, Kuhlwilm M, Kircher M, Sawyer S, Fu Q, Heinze A, Nickel B, et al. Patterns of coding variation in the complete exomes of three Neandertals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:6666–6671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405138111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell JL, Mallick S, Richter DJ, Neubauer J, Schirmer C, Gnerre S, Reich D. Analysis of chimpanzee history based on genome sequence alignments. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DF, Pinto D, Redon R, Feuk L, Gokcumen O, Zhang Y, Aerts J, Andrews TD, Barnes C, Campbell P, et al. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature. 2009;464:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature08516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currat M, Excoffier L. Strong reproductive isolation between humans and Neanderthals inferred from observed patterns of introgression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:15129–15134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107450108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cid R, Riveira-Munoz E, Zeeuwen PL, Robarge J, Liao W, Dannhauser EN, Giardina E, Stuart PE, Nair R, Helms C, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:211–215. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Carrington M, O’Brien SJ. Balanced polymorphism selected by genetic versus infectious human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2002;3:263–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.022502.103149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgio M, Lohmueller KE, Nielsen R. A model-based approach for identifying signatures of ancient balancing selection in genetic data. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos C, Essioux L, Teinturier C, Tauber M, Goffin V, Bougnères P. A common polymorphism of the growth hormone receptor is associated with increased responsiveness to growth hormone. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:720–724. doi: 10.1038/ng1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D, Hammer MF. Reconstructing human origins in the genomic era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, Galaxy Team Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokcumen O, Babb PL, Iskow RC, Zhu Q, Shi X, Mills RE, Ionita-Laza I, Vallender EJ, Clark AG, Johnson WE, et al. Refinement of primate copy number variation hotspots identifies candidate genomic regions evolving under positive selection. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R52. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokcumen O, Zhu Q, Mulder LC, Iskow RC, Austermann C, Scharer CD, Raj T, Boss JM, Sunyaev S, Price A, et al. Balancing selection on a regulatory region exhibiting ancient variation that predates human–Neandertal divergence. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, Patterson N, Li H, Zhai W, Fritz MH, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MF, Woerner AE, Mendez FL, Watkins JC, Wall JD. Genetic evidence for archaic admixture in Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:15123–15128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Wang Y, Ding Q, He Y, Wang M, Wang J, Xu S, Jin L. unpublished data, http://arxiv.org/abs/1404.7766, last accessed December 12, 2014.

- Hudson RR, Boos DD, Kaplan NL. A statistical test for detecting geographic subdivision. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:138–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Sánchez E, Jin X, Asan, Bianba Z, Peter BM, Vinckenbosch N, Liang Y, Yi X, He M, Somel M, et al. Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature. 2014;512:194–197. doi: 10.1038/nature13408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itsara A, Cooper GM, Baker C, Girirajan S, Li J, Absher D, Krauss RM, Myers RM, Ridker PM, Chasman DI, et al. Population analysis of large copy number variants and hotspots of human genetic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause J, Fu Q, Good JM, Viola B, Shunkov MV, Derevianko AP, Pääbo S. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature. 2014;505:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Mittnik A, Renaud G, Mallick S, Kirsanow K, Sudmant PH, Schraiber JG, Castellano S, Lipson M, et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature. 2014;513:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CY, Reno PL, Pollen AA, Bassan AI, Capellini TD, Guenther C, Indjeian VB, Lim X, Menke DB, Schaar BT, et al. Human-specific loss of regulatory DNA and the evolution of human-specific traits. Nature. 2011;471:216–219. doi: 10.1038/nature09774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard V, Eap O, Harvey M, Guillemette C, Lévesque E. Copy-number variations (CNVs) of the human sex steroid metabolizing genes UGT2B17 and UGT2B28 and their associations with a UGT2B15 functional polymorphism. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1310–1319. doi: 10.1002/humu.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, Kircher M, Gansauge MT, Li H, Racimo F, Mallick S, Schraiber JG, Jay F, Prüfer K, de Filippo C, et al. A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science. 2012;338:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1224344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RE, Walter K, Stewart C, Handsaker RE, Chen K, Alkan C, Abyzov A, Yoon SC, Ye K, Cheetham RK, et al. Mapping copy number variation by population-scale genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;470:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer J, Holmskov U, Wiemann S, Krebs I, Herbertz S, Madsen J, Kioschis P, Coy JF, Poustka A. The genomic structure of the DMBT1 gene: evidence for a region with susceptibility to genomic instability. Oncogene. 1999;18:6233–6240. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer J, Wiemann S, Scheurlen W, Korn B. DMBT1, a new member of the SRCR superfamily, on chromosome 10q25. 3–26.1 is deleted in malignant brain tumours. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:32–39. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol JW, Helt GA, Blanchard SG, Jr, Raja A, Loraine AE. The Integrated Genome Browser: free software for distribution and exploration of genome-scale datasets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2730–2731. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padidela R, Bryan SM, Abu-Amero S, Hudson-Davies RE, Achermann JC, Moore GE, Hindmarsh PC. The growth hormone receptor gene deleted for exon three (GHRd3) polymorphism is associated with birth and placental weight. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;76:236–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M, Krause J, Patterson N, Durand EY, Viola B, Briggs AW, Stenzel U, Johnson PL, et al. Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature. 2010;468:1053–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature09710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M, Bergmann G, Krebs I, End C, Lyer S, Hilberg F, Helmke B, Gassler N, Autschbach F, Bikker F, et al. DMBT1 confers mucosal protection in vivo and a deletion variant is associated with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1499–1509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph MC, Neville MC, Anderson SM. Lipid synthesis in lactation: diet and the fatty acid switch. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:269–281. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S, Mallick S, Dannemann M, Prüfer K, Kelso J, Pääbo S, Patterson N, Reich D. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature. 2014;507:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nature12961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoglund P, Jakobsson M. Archaic human ancestry in East Asia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:18301–18306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108181108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K, Aksglaede L, Petersen JH, Leffers H, Juul A. The exon 3 deleted growth hormone receptor gene is associated with small birth size and early pubertal onset in healthy boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2819–2826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira JC, de Filippo C, Weihmann A, Meneu JR, Racimo F, Dannemann M, Nickel B, Fischer A, Halbwax M, Andre C, Atencia R, Meyer M, Parra G, Pääbo S, Andrés AM. unpublished data, http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2014/06/27/006684, last accessed December 12, 2014.

- Veeramah KR, Hammer MF. The impact of whole-genome sequencing on the reconstruction of human population history. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:149–162. doi: 10.1038/nrg3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernot B, Akey JM. Resurrecting surviving Neandertal lineages from modern human genomes. Science. 2014;343:1017–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1245938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall JD, Yang MA, Jay F, Kim SK, Durand EY, Stevison LS, Gignoux C, Woerner A, Hammer MF, Slatkin M. Higher levels of Neanderthal ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans. Genetics. 2013;194:199–209. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.148213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Sun D, Daly A, Yang F, Zhou X, Zhao M, Huang N, Zerjal T, Lee C, Carter NP, et al. Adaptive evolution of UGT2B17 copy-number variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.