Abstract

Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are composed of abnormal aggregates of the cytoskeletal protein tau. Together with amyloid β (Aβ) plaques and neuronal and synaptic loss, NFTs constitute the primary pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease (AD). Recent evidence also suggests that caspases are activated early in the progression of AD and may play a role in neuronal loss and NFT pathology. Here we demonstrate that tau is cleaved at D421 (ΔTau) by executioner caspases. Following caspase-cleavage, ΔTau facilitates nucleation-dependent filament formation and readily adopts a conformational change recognized by the early pathological tau marker MC1. ΔTau can be phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3β and subsequently recognized by the NFT antibody PHF-1. In transgenic mice and AD brains, ΔTau associates with both early and late markers of NFTs and is correlated with cognitive decline. Additionally, ΔTau colocalizes with Aβ1–42 and is induced by Aβ1–42 in vitro. Collectively, our data imply that Aβ accumulation triggers caspase activation, leading to caspase-cleavage of tau, and that this is an early event that may precede hyperphosphorylation in the evolution of AD tangle pathology. These results suggest that therapeutics aimed at inhibiting tau caspase-cleavage may prove beneficial not only in preventing NFT formation, but also in slowing cognitive decline.

Introduction

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that stabilizes the neuronal cytoskeleton and participates in vesicular transport and axonal polarity (1–4). In the brain, there are six isoforms of tau, produced by alternative mRNA splicing of a single gene located on chromosome 17. Pathological alterations in tau occur in several neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer disease (AD), supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (5).

In AD, insoluble neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of hyperphosphorylated forms of tau accumulate initially within the entorhinal cortex and CA1 subfield of the hippocampus (6–8). Recent studies have begun to clarify the sequence of tau alterations that lead to neurodegeneration, including conformational changes and hyperphosphorylation. Antibodies developed against pathological tau have helped to identify these changes. An aberrant folded conformational change in tau, recognized with antibody MC1, appears to be one of the earliest tau pathological events (9–12). The antibody AT8 recognizes tau phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205, which are the first residues to be hyperphosphorylated, whereas the antibody PHF-1 recognizes phosphorylation at serines 396 and 404 and reacts with more mature hyperphosphorylated forms of tau found primarily within late-stage tangles (13–15). Such alterations in tau may reduce its binding affinity for microtubules, thereby leading to depolymerization of microtubules and contributing to the neuronal loss observed in AD (16–18).

Caspases are cysteine aspartate proteases that are critically involved in apoptosis. These enzymes can be broadly divided into initiator and executioner caspases, with the former functioning to initiate apoptosis by activating executioner caspases and the latter acting on downstream effector substrates that result in the progression of apoptosis and the appearance of hallmark morphological changes such as cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, and membrane blebbing (19). Increasing evidence suggests that caspases are activated in the AD brain (20–26). Furthermore, components of the neuronal cytoskeleton, including tau, are targeted by caspases following apoptotic stimuli (23, 27–34). Although the role of tau caspase-cleavage in AD pathology remains unresolved, recent evidence now implicates the caspase-cleavage of tau in tangle pathology (34). However, in AD, it is unclear whether hallmark pathological lesions induce caspases, whether caspases contribute to these lesions, or whether both occur.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in tangle formation in both AD and a transgenic model of this disorder. We found that caspase-cleaved tau catalyzes filament formation, adopts a conformation found in early-stage tangles, and can be hyperphosphorylated. Caspase-cleavage of tau also colocalizes with amyloid β (Aβ) and developing tangles in both transgenic mice and the AD brain. In primary cortical neurons, Aβ-induced caspase activation leads to tau cleavage and generates tangle-like morphology. Thus, our data suggest that caspase activation is an early event in NFT formation that can be triggered by Aβ, and that caspase activation may contribute to an important hallmark lesion of AD.

Results

Tau is cleaved at D421 by executioner caspases.

To determine which caspases cleave tau, recombinant human tau40 was treated with several active caspases. Incubation of tau with caspase-3 or -7, but not with caspase-1, -4, -5, -8, or -10, resulted in a 2-kDa electrophoretic shift by SDS-PAGE (Figure 1A, arrowhead). Analysis of the cleavage products by electrospray mass spectroscopy revealed two tau fragments with molecular weights of 45,900.00 Da (ΔTau) and 1,997.99 Da (C-terminus), corresponding to the theoretical molecular weights of tau cleaved after amino acid residue D421 (45,900.80 Da and 1,999.29 Da) (see supplemental data; available at http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/full/114/1/121/DC1). Cleavage after D421 was also confirmed by primary amino acid sequencing of the small fragment (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Executioner caspases cleave tau at D421. (A) Recombinant human tau40 (Calbiochem) treated with various caspases was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Treatment with caspase-3 (C3) and caspase-7 (C7) resulted in a 2-kDa shift (arrowhead) relative to full-length tau (FL), while treatment with caspase-1 (C1), -4 (C4), -5 (C5), -8 (C8), or -10 (C10) did not (arrow). (B) Western blot analysis confirmed the specificity of polyclonal antibody (α-ΔTau) to D421 caspase-cleaved tau. α-ΔTau recognized caspase-3– and caspase-7–cleaved tau, but not uncleaved tau. (C) Executioner caspases remove the C-terminal epitope of tau that is recognized by antibody T46. Full-length and caspase-cleaved tau was probed with mAb T46.

To examine the role of ΔTau in NFT pathology, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody (α-ΔTau) directed against the caspase-cleaved carboxy-terminus of tau. The specificity of α-ΔTau was confirmed by Western blot analysis and was found to selectively recognize the D421-cleaved fragment generated by caspase-3 or -7 but not full-length tau (Figure 1B). In contrast, a previously generated antibody that recognizes the C-terminus of tau (T46; ref. 35, 36) detects full-length tau but not ΔTau (Figure 1C).

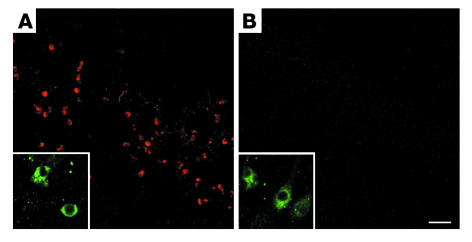

Specificity of the α-ΔTau antibody was further assessed, in vivo, using traumatic brain injury (TBI), a model that leads to neuronal caspase activation (37). Forty-eight hours after injury, immunohistochemical analysis confirmed caspase-3 activation within both wild-type (Figure 2A, inset) and Tau–/– brains (Figure 2B, inset). However, ΔTau immunoreactivity was observed within wild-type (Figure 2A) but not Tau–/– (Figure 2B) mice following TBI. In contrast, caspase-cleaved fodrin, another cytoskeletal target of caspases, was observed within both wild-type and tau knockout brains (see supplemental data). Therefore, the α-ΔTau antibody specifically detects caspase-cleaved tau and does not cross-react with other caspase-cleaved substrates in vivo.

Figure 2.

The α-ΔTau antibody specifically recognizes caspase-cleaved tau in vivo. Wild-type (A) and Tau–/– (B) mice were subjected to TBI to induce caspase activation. Immunofluorescent labeling with an antibody to active caspase-3 confirmed caspase activation within both wild-type (A, inset) and tau knockout (B, inset) brains. ΔTau immunoreactivity was also detected within wild-type brains (A). In contrast, ΔTau immunoreactivity was not observed within tau knockout mice following TBI (B), which further confirms the specificity of the α-ΔTau antibody in vivo. Scale bar: 80 μm (A and B), 20 μm (insets).

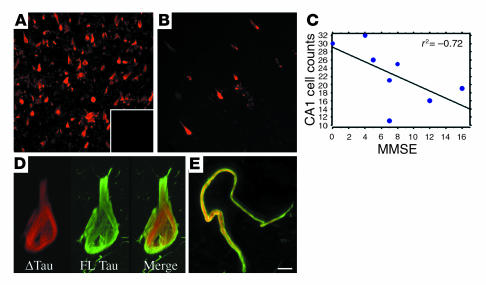

ΔTau is prevalent within the AD brain and is inversely correlated with cognitive function. To determine whether ΔTau is associated with AD neuropathology, AD and control hippocampal sections were immunolabeled with the α-ΔTau antibody. We observed extensive α-ΔTau labeling within AD hippocampus (Figure 3A). In contrast, only occasional ΔTau-positive cells were observed in controls (Figure 3B). Preadsorption of the α-ΔTau antibody with immunizing peptide led to a loss of all immunoreactivity (Figure 3A, inset).

Figure 3.

ΔTau is found predominantly within AD brain and is inversely correlated with cognitive function. Large numbers of ΔTau-immunoreactive neurons (red) were observed in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of AD brains (A). In contrast, only occasional ΔTau-immunoreactive cells were observed in age-matched control cases (B). Preadsorption of the α-ΔTau antibody with immunizing peptide resulted in no immunofluorescence (A, inset). Regression analysis of the number of hippocampal CA1 cells labeled with α-ΔTau versus AD Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores revealed a significant inverse correlation between ΔTau and cognitive function (P = 0.05, r2 = –0.72; (C). High-power confocal microscopy demonstrated distinct subcellular localization of ΔTau (red) and the C-terminal–specific antibody T46 (green) within cell bodies (D) and dystrophic neurites (E). Scale bar: 65 μm (A and B), 8 μm (D), 5 μm (E).

Next, we performed light-level immunohistochemistry to quantify the number of ΔTau-immunoreactive cells within CA1 of AD versus control hippocampus (data not shown). Significantly more ΔTau-immunoreactive cells were observed in AD than in control brains (AD, 28.2 ± 1.65; control, 4.25 ± 0.85; P < 0.05). Furthermore, the number of ΔTau-immunoreactive cells within CA1 of AD cases inversely correlated with cognitive function (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score) (Figure 3C). Thus, ΔTau may contribute to cognitive decline in AD.

To assess the relationship between caspase-cleaved tau and full-length tau pathology, fluorescent double labeling for ΔTau and the C-terminal–specific antibody T46 was performed (36). High-power confocal imaging revealed an intriguing difference in subcellular distribution between these two markers, suggesting that both full-length tau (T46, green) and cleaved tau (α-ΔTau, red) are present within the same NFTs (Figure 3, D and E). T46 immunoreactivity was frequently observed surrounding ΔTau immunofluorescence in both cell bodies (Figure 3D) and dystrophic neurites (Figure 3E). The C-terminal epitope recognized by T46 (35) is liberated by executioner caspases (Figure 1C). Therefore, the minimal subcellular colocalization of ΔTau and T46 further confirms the cleavage site specificity of α-ΔTau.

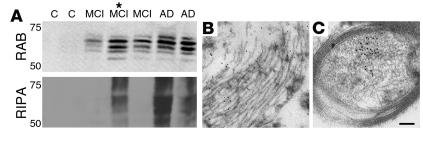

Tau becomes increasingly insoluble as AD progresses. Therefore, we performed sequential fractionation of control, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and AD brain lysates into high-salt reassembly buffer (RAB) and detergent-soluble radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA) fractions to examine the solubility of ΔTau as AD progresses. We found that ΔTau recognized multiple caspase-cleaved tau isoforms in both MCI and AD cases but not controls within the high-salt soluble RAB fraction (Figure 4A). In the detergent-soluble RIPA fraction, ΔTau was present within AD cases and also in a more advanced MCI-AD transitional case (Figure 4A, asterisk), but not within MCI or control cases (Figure 4A). In addition, ΔTau appeared to be post-transationally modified (hyperphosphorylation or ubiquitination) within the RIPA fraction, as evidenced by smeared signal (Figure 4A). Therefore, ΔTau appears to become increasingly insoluble as AD advances.

Figure 4.

ΔTau becomes increasingly insoluble with disease progression and is associated with tangle-like pathology at the ultrastructural level. Control (C), MCI, and AD temporal cortex samples were subjected to sequential fractionation into high-salt RAB and detergent-soluble RIPA fractions as previously described (50, 78) (A). ΔTau was detected in the soluble RAB fraction of MCI and AD but not control cases, suggesting that ΔTau production coincides with the early stages of cognitive decline in AD. In detergent-soluble RIPA fractions, ΔTau was only detected in higher-pathology MCI and AD cases, which suggests that ΔTau becomes more insoluble as AD progresses. *This patient was considered transitional between MCI and AD (see Methods). Immunogold electron microscopy demonstrated ΔTau at the ultrastructural level in association with early tangle-like pathology within a neuronal cell body (B) and a myelinated axon (C). Scale bar: 0.4 μm (B), 0.3 μm (C).

To further elucidate the subcellular distribution of ΔTau in the AD brain, immunogold electron microscopy was performed using the α-ΔTau antibody. A diffuse distribution of α-ΔTau conjugated gold particles was observed in association with tangle-like structures within neuronal somata (Figure 4B). In addition, gold particles were observed within structurally intact axons (Figure 4C), which indicates that caspase-cleavage of tau may precede neuritic pathology.

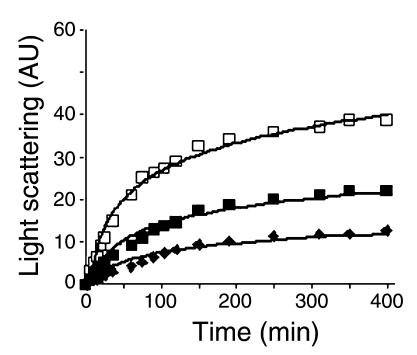

ΔTau induces filament formation. To determine whether ΔTau contributes to tangle pathology by promoting filament formation, we measured light scattering, which has previously been shown to be an effective means of monitoring tau filamentous aggregates (38). Tau was incubated in the presence of heparin, which accelerates tau aggregation in vitro, so that we could assay filament formation in real time (39). We found that caspase-3–cleaved tau (filled squares) demonstrated increased light scattering over time (indicative of filament formation) and aggregated more rapidly than full-length tau (filled diamonds, Figure 5). In addition, ΔTau accelerated filament formation of full-length tau, as the incubation of full-length tau in the presence of ΔTau resulted in a dramatic increase in the rate of scattered light (open squares, Figure 5). These results show not only that caspase-cleavage of tau leads to increased filament formation, but that ΔTau may also act to seed filament formation of full-length tau. These data further support a nucleation-dependent mechanism of tau filament assembly (40).

Figure 5.

Caspase-cleavage of tau drives filament formation of full-length tau in vitro. Laser light scattering was used to assess tau filament formation in vitro. Equimolar (4 μM) amounts of ΔTau (filled squares), full-length tau (filled diamonds), or a 3:1 ratio of full-length tau to ΔTau (open squares) were monitored over 400 minutes. ΔTau (filled squares) scattered light (arbitrary units [AU]) more rapidly and to a greater degree than full-length tau (filled diamonds), indicating increased filament formation. Most interestingly, a 3:1 ratio of full-length tau to ΔTau (open squares) dramatically accelerated light scattering, suggesting that ΔTau may nucleate the assembly of full-length tau filaments.

Caspase-cleavage induces a conformational change in tau, which can be hyperphosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3

β. The increased propensity of ΔTau to induce filament formation may ensue from a conformational change that follows liberation of the C-terminus. One of the earliest pathological alterations in tau during AD is a conformational change that is recognized by the antibody MC1 (12). Because the formation of the MC1 epitope occurs prior to paired helical filament (PHF) assembly (12), we hypothesized that ΔTau may likewise adopt this conformation. Immunoprecipitation with MC1 preferentially recognized ΔTau over full-length tau in three separate experiments (Figure 6A). Therefore, our results show that caspase-cleavage of tau induces an early conformational change recognized by MC1.

Figure 6.

Caspase-cleavage of tau induces a conformational epitope that is recognized by the antibody MC1 and can be phosphorylated by GSK3-β. (A) MC1, a mAb that recognizes an early tau conformational change, was coupled to protein G and used to immunoprecipitate either full-length (lane 1) or caspase-3–cleaved recombinant tau (lane 2). Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated proteins probed with an anti-tau polyclonal antibody revealed an increased affinity of the MC1 antibody for ΔTau over full-length tau. (B) In vitro phosphorylation of ΔTau: Either full-length or caspase-3–cleaved tau was phosphorylated with the kinase GSK-3β and then analyzed by Western blot with the phosphorylation-dependent antibody PHF-1. Immunoreactivity for PHF-1 demonstrates that, like full-length tau (FL), caspase-cleaved tau (ΔTau) can be hyperphosphorylated and suggests that caspase-cleavage of tau does not preclude subsequent hyperphosphorylation. Numbers over each lane indicate the number of hours that tau species were incubated with GSK-3β. MC1 and PHF-1 experiments were replicated three times, and representative immunoblots are shown.

Besides a conformational change, phosphorylation of specific residues is another important stage in the pathology of tau. Accordingly, we tested whether caspase-cleaved tau can be hyperphosphorylated in vitro. Recombinant full-length tau and caspase-cleaved tau were incubated at 37°C in the presence of ATP and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), a kinase implicated in the hyperphosphorylation of tau (41). Western blot analysis with the tau phospho-epitope antibody PHF-1 revealed that both ΔTau and full-length tau were hyperphosphorylated in vitro by GSK-3β (Figure 6B). Although we assayed kinase activity over a 4-hour period, phosphorylation of ΔTau occurred rapidly within 1 hour. Therefore, caspase-cleavage does not preclude subsequent hyperphosphorylation of tau, which further supports the notion that ΔTau may occur early in the development of NFT pathology.

ΔTau is observed throughout the evolution of NFT pathology in the AD brain. Because ΔTau adopts a conformation that is recognized by the MC1 antibody and can be phosphorylated to form the PHF-1 epitope, we performed triple-labeling experiments with α-ΔTau (red), MC1 (green), and fluorescently labeled PHF-1 (blue) to determine whether ΔTau colocalized with early (MC1) or late (PHF-1) tau pathological alterations in AD (Figure 7). In the AD hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, we found both neurons (Figure 7, A–D) and dystrophic neurites (Figure 7, E and F) that labeled with ΔTau, MC1, and PHF-1. We observed all three labels in pretangle (Figure 7A), diffuse tangle–bearing (Figure 7B), and mature tangle–bearing neurons (Figure 7, C and D). Interestingly, we did not observe any cells that expressed MC1 and PHF-1 without ΔTau, which strengthens our assertion that ΔTau is important in tangle formation. Finally, triple labeling of plaque-associated dystrophic neurites revealed numerous permutations of the three tangle markers, suggesting that dystrophic neurites also show varying degrees of AD pathological progression (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

ΔTau is present throughout the evolution of NFT pathology. Triple immunofluorescence was used to examine the association of ΔTau (red) with the conformation-sensitive tau antibody MC1 (green) and the tau phosphoepitope antibody PHF-1 (blue) in hippocampal NFT pathology. ΔTau (red) was coincident with MC1 and PHF-1 throughout the evolution of NFT pathology within pretangle neurons (A), diffuse tangle–bearing neurons (B), mature tangle–bearing neurons (C and D), and dystrophic neurites (E and F). Scale bar: 8 μm (A, C, and D), 12 μm (B), 4 μm (E), 10 μm (F).

Active caspase-3 colocalizes withΔTau within pretangle neurons and dystrophic neurites of the AD brain.

To further examine whether caspase activation and caspase-cleavage of tau occur early in the formation of tangles, we performed fluorescent double labeling for active caspase-3 and ΔTau. We observed colocalization of active caspase-3 with ΔTau, specifically within pretangle neurons of CA1 (Figure 8A) and dystrophic neurites (Figure 8B). In contrast, within mature extracellular tangles, active caspase-3 was not observed, possibly because of loss of membrane integrity and cell death (Figure 8C). Taken together, these data suggest that caspase activation and caspase-cleavage of tau occur early in tangle development. However, caspase activation appears to be lost with cell death, while ΔTau persists within extracellular NFTs, perhaps as insoluble accumulations.

Figure 8.

Caspase activation and intracellular Aβ colocalize with ΔTau in the AD brain. Fluorescent confocal imaging demonstrated that ΔTau (red) and active caspase-3 (green) colocalized within pretangle neurons (A) and dystrophic neurites (B) of the AD hippocampus. In contrast, mature extracellular tangles contained ΔTau without evidence of caspase activation (C). Intracellular Aβ (green), a known initiator of caspases, colocalizes with ΔTau (red) within AD neurons (D and E). In addition, ΔTau-immunoreactive dystrophic neurites (red) were frequently associated with extracellular amyloid plaques (F). Scale bar: 5 μm (A), 1.5 μm (B), 6 μm (C), 3 μm (D and E), 25 μm (F).

Evidence thatΔTau is induced by A

β. Aβ activates caspases in vitro (42–44). Therefore, we sought to examine whether ΔTau colocalized with Aβ in the AD brain. We found that ΔTau (red) colocalized with granular intraneuronal Aβ deposits (green) within CA1 (Figure 8, D and E). Similar results were observed with two different Aβ-specific antibodies (Aβ1–42 and 4G8). ΔTau-immunoreactive dystrophic neurites were also frequently observed in association with Aβ-immunoreactive plaques (Figure 8F). Combined, these data suggest that both intracellular and extracellular Aβ may induce caspase-cleavage of tau.

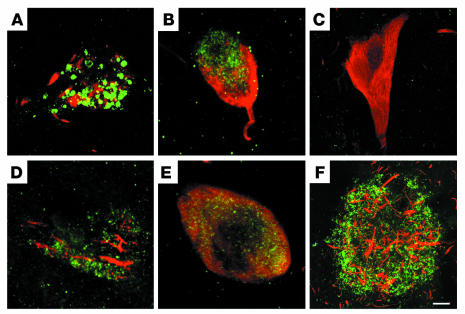

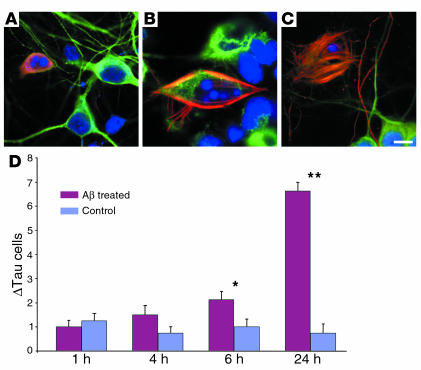

Because we found that Aβ colocalized with ΔTau in the AD brain, we determined whether Aβ might induce caspase-cleavage of tau in cultured rat primary cortical neurons. Using immunofluorescent triple labeling for ΔTau (red), the neuronal marker MAP-2 (green), and DAPI (blue), we found a significant increase in ΔTau-positive neurons following fibrillar Αβ1–42 treatment (Figure 9). Quantification of cell number (see Methods) revealed a significant increase in ΔTau-positive cells following Αβ1–42 treatment (F (7, 31) = 43.28, P < 0.0001). After 6 hours of treatment, a twofold increase in ΔTau-immunoreactive cells was observed (control, 1.0 ± 0.33 cells; treated, 2.13 ± 0.35 cells; P = 0.012). However, by 24 hours, the number of ΔTau-immunoreactive cells was increased almost ninefold over that of untreated cells (control, 0.75 ± 0.37 cells; treated, 6.63 ± 0.38 cells; P < 0.0001) (Figure 9D). The number of ΔTau-immunoreactive cells was not significantly affected after only 1 hour (P = 0.560) or 4 hours (P = 0.086) of Αβ1–42 treatment. The majority of ΔTau-bearing neurons (91.5%) in control and Αβ1–42-treated cultures contained apoptotic nuclei, as assessed by DAPI (Figure 9, A–C, blue). Furthermore, we discovered that ΔTau labeled striking tangle-like structures in dying neurons (Figure 9, B and C). Therefore, Aβ1–42 triggers the production of ΔTau in vitro.

Figure 9.

Treatment of cortical neurons with Aβ leads to increased ΔTau immunoreactivity. Fluorescent triple labeling of rat primary cortical neurons for ΔTau (red), MAP-2 (green), and DAPI (blue) following Aβ treatment (A–C). A significant increase in ΔTau-positive cells (red) was observed after 6 hours (*P = 0.012) and 24 hours (**P < 0.0001) of Aβ treatment (D). The great majority of ΔTau-positive cells (91.5%) contained apoptotic nuclei as revealed by DAPI (A–C). In addition, ΔTau immunolabeling also revealed striate tangle-like morphology in association with apoptotic nuclei (B and C). Scale bar: 9 μm (A), 5 μm (B), 7.5 μm (C).

ΔTau is detected early in the progression of tangle pathology in a triple-transgenic model of AD. To better assess the role of caspase-cleaved ΔTau in the pathogenesis of AD, we determined whether ΔTau was present in the brains of transgenic mice. We used a recently characterized triple-transgenic mouse (3xTg-AD) that recapitulates many salient features of AD: progressively developing intraneuronal Aβ, deficits in long-term potentiation, amyloid plaques, and, subsequently, NFTs (45). We examined brains from 6- (with only Aβ deposits but no NFT pathology), 12- (in the initial stages of NFT pathology), and 18-month-old mice (in which both plaque and NFT were well established). At 6 months of age, we detected intracellular Aβ, but not ΔTau immunoreactivity (data not shown). By 12 months of age, we found that ΔTau (red) colocalized with intraneuronal Aβ immunoreactivity within CA1 neurons of the hippocampus (Figure 10A). In older mice (18 months), Aβ and ΔTau colocalized within both CA1 neurons (Figure 10B) and the neocortex (Figure 10C). This finding closely mimics the progression of NFT pathology that has previously been reported in 3xTg-AD mice (45). Next, we investigated whether ΔTau colocalized with MC1 in this transgenic model. Colocalization of ΔTau (red) and MC1 (green) was first observed within CA1 pyramidal neurons at 12 months of age (Figure 10D) and persisted in 18-month-old mice (Figure 10, E and F). Interestingly, the subcellular distribution of ΔTau evolved with increasing age. At 12 months, the great majority of ΔTau-immunoreactive cells displayed punctate cleavage product within the soma and proximal dendrites of neurons (Figure 10, A and D). However, by 18 months of age, many ΔTau-bearing neurons exhibited aggregated filamentous structures that appeared strikingly similar to AD tangle pathology (Figure 10, C and F).

Figure 10.

ΔTau colocalizes with pathological features of a triple-transgenic model of AD. Fluorescent double labeling of 3xTg-AD mice demonstrates that intraneuronal Aβ (green) colocalizes with ΔTau (red) within CA1 pyramidal neurons of 12-month-old (A) and 18-month-old (B) 3xTg-AD mice and within 18-month-old neocortex (C). ΔTau immunoreactivity (red) also colocalizes with an early tangle marker, MC1 (green), within CA1 pyramidal neurons at both 12-month (D) and 18-month time points (E and F). Scale bar: 30 μm (A, D, and E), 20 μm (B), 4 μm (C and F).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that caspase-cleavage of tau near the carboxy-terminus leads to a conformational change that is preferentially recognized by the early tangle marker MC1. ΔTau also accelerates the aggregation of full-length tau filaments and can be hyperphosphorylated in vitro. Since ΔTau colocalizes with MC1 within neurons of subjects with AD and 3xTg-AD mice, we postulate that caspase-cleavage of tau occurs early in NFT formation. This hypothesis is further supported by the presence of ΔTau in brain extracts from patients with MCI and the detection of ΔTau within pretangle-like structures by electron microscopy. However, the fact that ΔTau colocalizes with PHF-1 in the AD brain suggests that although ΔTau may occur early in NFT formation, it persists throughout the evolution of NFTs.

The kinetics data support a role for ΔTau in seeding tau pathology via a nucleation-dependent mechanism. Tau dimerization and subsequent nucleation events are proposed to be the rate-limiting step in filament formation (40). Because caspase-cleaved tau enhanced the rate of full-length tau filament formation, we speculate that caspase-cleavage of tau may either increase the propensity for tau to dimerize and/or affect nucleation-dependent filament assembly. Because MC1-immunoreactive tau aggregates more readily than recombinant tau (12), the adopted MC1 conformation may explain why ΔTau enhances filament formation. The MC1 conformation may involve the intramolecular interaction between the N- and C-termini of tau (folded conformation). Caspase-cleavage of tau may initiate the MC1 conformation by removing a portion of the C-terminus that inhibits tau aggregation in vitro (46), and allowing tau to adopt this conformation.

Although isolated PHFs contain truncated tau species (e.g., truncation at Glu391) that may play a role in NFT formation (47, 48), the mechanism(s) that gives rise to tau truncation is currently unknown. The presence of ΔTau throughout the progression of tangle pathology suggests that truncated tau species may arise from further proteolysis of ΔTau. However, the presence of both full-length tau (T46) and ΔTau in NFTs implicates a role for both full-length and caspase-cleaved tau in tangle formation. Although ΔTau colocalized with several NFT markers in the AD brain, we have not yet demonstrated the presence of ΔTau within PHFs at the ultrastructural level. Future experiments aim to address this caveat.

Hyperphosphorylation of tau is the prevailing hypothesis in the development of tangle pathology, since hyperphosphorylation can promote PHF self-assembly (49). Transgenic animal models (mice, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila) strengthen this hypothesis (50–54). Although no previous mechanism has been described linking caspase-cleavage and the hyperphosphorylation of tau, the appearance of hyperphosphorylated tau following the activation of apoptosis suggests that the two events may be closely connected (55). Our data show that ΔTau can be hyperphosphorylated after caspase-cleavage, therefore suggesting that production of ΔTau does not preclude subsequent hyperphosphorylation.

Recent evidence suggests that Aβ accumulation precedes NFT formation in the AD brain and can potentiate NFTs in transgenic mice (45, 51, 52, 56–58). Furthermore, Aβ-induced neurodegeneration requires tau expression and may involve the intracellular assembly of pathological tau filaments (59, 60). The colocalization of ΔTau with both intraneuronal and extracellular Aβ deposits suggests that Aβ accumulation may initiate caspase-cleavage of tau. The granular appearance of intracellular Aβ is also observed in Down syndrome patients with AD (61), indicating that intraneuronal Aβ may be a common feature of AD subtypes. It has been proposed that intraneuronal Aβ accumulation may precede extracellular-plaque pathology in both AD and transgenic mouse models (45, 57, 61–63), further suggesting that caspase-cleavage of tau may occur early in AD pathology. However, the notion that intracellular Aβ precedes extracellular-plaque deposition remains controversial.

Functional decline in AD correlates with increasing tangle pathology (56, 64–66). The production of ΔTau correlated with the clinical progression of AD. In addition to possibly initiating NFT pathology, caspase-cleavage of tau may contribute to neuronal dysfunction. 3xTg-AD mice develop synaptic dysfunction that coincides with intracellular Aβ accumulation (45). Because intracellular Aβ colocalized with caspase-cleaved tau in the brains of both subjects with AD and 3xTg-AD mice, ΔTau may contribute to further synaptic dysfunction and loss, in vivo. In a C. elegans model of tau neurodegenerative disease that displays defects in cholinergic transmission, Kraemer et al. detected a truncated tau species (50). It is interesting to speculate that this truncation may be due to caspase-cleavage and may contribute to the observed synaptic dysfunction.

AD is also characterized by the activation of apoptotic pathways. Although the hypothesis that apoptosis plays a role in AD neurodegeneration remains controversial, recent evidence suggests that caspase activation can occur independent of cell death and may be neuroprotective (67–69). In addition, caspase activation is implicated in long-term potentiation and neurite extension (70). However, caspase-cleaved tau leads to neurite retraction in vitro (71) and thus may contribute to synaptic deficits and cellular demise. Although the mechanisms that trigger caspases in the AD brain are currently unknown, Aβ, which accumulates in the AD brain, is one of many known activators of apoptosis (42, 72). Because caspase activation is associated with NFT pathology (20–23, 25, 29), our data support the idea that Aβ-induced caspase activation may lead to pathological tau (34, 73). Thus, in AD, Aβ and tau pathologies may be closely linked through a common pathway, caspase-mediated proteolysis. Furthermore, we observed that ΔTau immunoreactivity defined striking tangle-like structures in degenerating neurons, which is suggestive of Aβ contributing to tangle pathology (51, 52, 58, 74). Interestingly, in tau transgenic Drosophila, inhibitors of apoptosis suppressed tau-induced neurodegeneration (53). Although tau is also hyperphosphorylated in this model, the inhibition of neurodegeneration underlies the importance of caspase activation and possibly tau caspase-cleavage in this animal model.

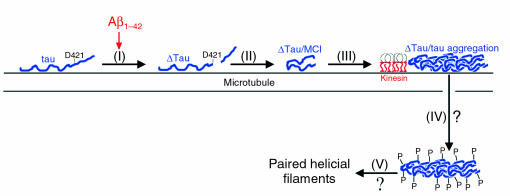

Finally, our results are in agreement with a recent study demonstrating that Aβ leads to caspase-cleavage of tau (34). The authors’ findings and ours support a model in which any stimuli capable of activating caspases (e.g., oxidative damage, neurotrophic factor deprivation, low energy metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction) can initiate NFT pathology. Our preliminary data indicate that 4-hydroxynonenal, an inducer of oxidative stress and activator of caspases, leads to the production of ΔTau in rat primary neurons (data not shown). Thus, we have proposed a model describing the role of caspase-cleavage of tau in the development of tangle pathology (Figure 11). Following any stimulus that results in caspase activation (e.g., Aβ1–42), tau is cleaved at D421 (step 1). Upon caspase-cleavage, tau adopts an MC1-immunoreactive conformation (step 2), which leads to increased filament formation that may occur on microtubules (where tau binds in vivo) (step 3) (75). Although we do not specifically examine whether caspase-cleaved tau results in deficits in kinesin-mediated transport, we speculate that ΔTau may block kinesin-mediated anterograde transport akin to the overexpression of tau (2, 3). As a protective mechanism in order to compensate (relieve the blockage), phosphorylation of tau occurs to dissociate it from microtubules (step 4) (16–18). Finally, dissociation of phosphorylated tau species leads to destabilization of the microtubule network and PHF formation (step 5). Although destabilization of microtubules may initially be neuroprotective (59), it will eventually lead to the demise of the cell. Our mechanism does not exclude other reported mechanisms leading to tau hyperphosphorylation but suggests that caspase-cleavage of tau contributes to tau hyperphosphorylation in AD.

Figure 11.

Proposed model for the evolution of NFTs. Apoptotic stimuli such as Aβ1–42 exposure result in caspase-cleavage of tau after D421 (I). Caspase-cleaved tau rapidly adopts the MC1 conformational epitope (II), which leads to increased filament formation and tau aggregation (III). To compensate for tau aggregation, tau may subsequently be hyperphosphorylated and disassociate from the microtubule (IV). As a result, caspase-cleavage of tau may lead to PHF formation (V).

Thus, in neurodegenerative diseases where tau pathology occurs in the absence of Aβ (e.g., Pick disease and supranuclear palsy), other stimuli known to activate caspases may be involved in the initiation of NFT pathology. Therefore, caspase-cleavage of tau may play an important role not only in AD, but also in other tauopathies, and may serve as a key target for the development of novel therapeutics.

Methods

In vitro caspase-cleavage of tau.

To examine the specificity of caspase-cleavage of tau, 25 μg of recombinant human tau40 (Calbiochem, San Diego, California, USA) was incubated with active human recombinant caspase-1, -3, -4, -5, -7, -8, or -10 (Calbiochem; and AG Scientific Inc., San Diego, California, USA). The caspase-specific activity was adjusted so that all caspases would cleave 1 nmol of substrate per hour at 37°C. Caspase digestion was performed (4 hours, 37°C), and cleavage reactions were terminated by addition of 10% formic acid (1 μl). Full-length or caspase-treated recombinant tau (30 ng) was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie blue or analyzed by Western blot, as described below.

Electrospray mass spectrometry.

Samples were analyzed using an HPLC-Micromass Q-TOF 2 (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) using a hand-packed C8 silica column. The flow rate was split from 100 μl to 400 nl/min over a 60-minute gradient (3–70% acetonitrile). Deconvolution of the spectra was performed to identify protein masses (MaxEnt 1 software; Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom).

Generation ofα-ΔTau polyclonal antibody.

The peptide SSTGSIDMVD corresponding to the carboxy-terminus of tau following caspase-cleavage was conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin and injected into rabbits. Research Genetics Inc. (Huntsville, Alabama, USA) performed the synthesis of peptides, injections of immunogens, and collection of antisera. The peptide CSTGSIDMVD was covalently linked to a gel column (SulfoLink kit; Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, Illinois, USA) and used to affinity-purify antisera from individual rabbits.

Transgenic mice.

All rodent experiments were performed in accordance with animal protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at either the University of California, Irvine (UCI), or Duke University (TBI experiments). The triple-transgenic mice (3xTg-AD) have been described previously (45). Briefly, these mice harbor a knock-in mutation of presenilin 1 (PS1M146V), the Swedish double mutation of amyloid precursor protein (APPKM670/671NL), and a frontotemporal dementia mutation in tau (tauP301L) on a 129/C57BL/6 background. Homozygous mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation at 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month time points, and brains were rapidly removed and immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. Coronal sections were cut on a Vibratome (Technical Products International, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) (50 μm) and stored in PBS, 0.02% NaN3 (4°C), until use. Tau–/– mice (129/C57BL/6 background) have been previously described (76). Closed-head injury was performed in male tau knockout and wild-type mice (age 12–14 weeks) with a pneumatic impactor as previously described (77). Forty-eight hours after injury, mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused (4% paraformaldehyde). Following postfixation, brains were cut and stored as detailed above. All mice used in this study were maintained and housed in accordance with NIH and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines.

Human subjects.

Postmortem human brain tissues were obtained from the Institute for Brain Aging and Dementia Tissue Repository at UCI. A total of 12 neuropathologically confirmed AD cases, three cases with MCI, and 11 nondemented control cases, matched for both mean age and postmortem interval, were examined. Case demographics are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Brain sections fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and containing the midregion of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex were cut as described above. For Western analysis, superior temporal gyri from control, MCI, and AD cases underwent sequential fractionation, as described below. We also included a transitional AD case (*MCI). This patient fell outside the normal range of MCI but did not meet the criteria for AD dementia.

Clinical diagnoses.

Control cases exhibited no memory impairment and were normal on tests of functional ability. MCI was diagnosed by neuropsychological and neurological examination (at the Institute for Brain Aging and Dementia, UCI) as previously described (78). MCI individuals were not demented but had memory decline and scored at least 1.5 SD below the mean of their age-matched peers on objective tests of episodic memory (e.g., Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease [CERAD]; Word list test, Logical memory test). In addition, these individuals performed within normal limits on all other tests of cognitive functioning and had no significant deficits in measures of functional ability (e.g., Dementia Rating Severity Scale and Functional Activity Questionnaire).QuestionnaireAD cases were severely impaired in memory tasks and measures of functional ability and daily living.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy.

Light-level immunohistochemistry was performed using an avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, California, USA) and was visualized with diaminobenzidine as previously described (22). Fluorescent immunolabeling followed either a standard two-way technique (primary antibody followed by fluorescent secondary antibody) or a three-way protocol (primary antibody, biotinylated secondary antibody, and then streptavidin-conjugated fluorophore). Free-floating sections were rinsed in PBS (pH 7.4) and then blocked (0.25% Triton X-100, 5% normal goat serum in PBS) for 1 hour. Sections were incubated in primary antibody overnight (4°C), rinsed in PBS, and incubated (1 hour) in either fluorescently labeled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Alexa 488 or 568, 1:200; Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oregon, USA) or biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:150; Vector Laboratories Inc.) followed by streptavidin–Alexa 488 (1:200). When two monoclonal or two polyclonal antibodies were used in combination (e.g., MC1 and PHF-1), one antibody was detected using a standard fluorescent secondary antibody. The second epitope was detected by direct conjugation of a fluorophore to the primary antibody (Zenon kit; Molecular Probes Inc.). Antibodies were diluted as follows: ΔTau, 1:1,000; T46, 1:1,000 (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA); active caspase-3, 1:100 (Promega Corp., Madison, Wisconsin, USA); caspase-cleaved fodrin, 1:100 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, Massachusetts, USA); MC1 and PHF-1, 1:500 (gifts of P. Davies, Yeshiva University, Bronx, New York, USA); Aβ1–42, 1:100 (Biosource International Inc., Camarillo, California, USA); Aβ17–24 (clone 4G8), 1:100 (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, California, USA); MAP-2, 1:2,000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). DAPI (1:400; Molecular Probes Inc.) was used to assess apoptotic nuclei in vitro. Omission of primary antibody or use of preimmune IgG eliminated all labeling (data not shown). In addition, preadsorption of α-ΔTau antibody with an excess of immunizing peptide resulted in no immunoreactivity (Figure 3A, inset). Confocal images were captured on FluoView (Olympus America Inc., Melville, New York, USA) or MRC 1024 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) confocal systems. In some cases images were pseudocolored to maintain consistent use of color for a given antigen throughout all figures. To prevent signal bleed-through, all fluorophores were excited and scanned separately using appropriate laser lines and filter sets.

Quantification ofΔTau and correlation with MMSE score.

Using the human postmortem tissues described above, the relationship between ΔTau-immunoreactive cell number and cognitive function was examined. Sections from AD and control cases (n = 8) were immunolabeled for ΔTau using a standard avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique. The number of ΔTau-positive cells within control and AD sections was counted from ∞20 photographs of two randomly chosen regions of CA1. Cell counts were averaged and statistically compared by Student’s t test. The relationship between ΔTau-positive cell number and MMSE score was then determined by Spearman’s correlation test. Only AD cases were included in the analysis, since control cases can act as ordinate values and artificially increase correlation strength and significance. All statistical analyses were performed using StatView 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Analysis ofΔTau solubility.

Superior temporal gyri of control, MCI, and AD cases were processed to isolate RAB and RIPA fractions using previously described protocols (50, 79). Briefly, frozen tissue was homogenized in 2 ml/g of RAB-HS (0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino) [MES], 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.75 M NaCl, 0.02 M NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail [P8340; Sigma-Aldrich]) and centrifuged at 40,000 g for 40 minutes, and the supernatant (RAB fraction) was collected. The RAB-HS pellets were rehomogenized in RAB-HS containing 1 M sucrose and centrifuged at 40,000 g for 20 minutes. The pellets were subsequently resuspended in RIPA (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin) at 1 ml/g and centrifuged at 40,000 g for 20 minutes, and the resulting RIPA-soluble supernatant was collected. BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.) was performed to determine protein concentration, and equal protein amounts of RAB and RIPA fractions were then analyzed by Western blot.

Western blot analysis.

Recombinant tau proteins and brain lysates were processed for Western blot. Briefly, proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose (0.2 μm; Schleicher & Schuell BioScience Inc., Keene, New Hampshire, USA). Membranes were incubated in either α-ΔTau (1:1,000) or T46 (1:1,000). Primary antibody was visualized using either goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP-linked secondary antibody (1:1,000; Calbiochem), followed by ECL detection (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.).

Electron microscopy.

Tissue from AD cases was embedded in Lowicryl (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, California, USA), and ultrathin sections were immunolabeled using a post-embedding procedure (80) with ΔTau primary antibody (1:300), followed goat anti-rabbit IgG that was previously conjugated to 10 nm gold particles (1:20; Ted Pella Inc.). Following incubation in secondary antibody, the sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Philips CM 10 electron microscope (Phillips Electronic Instruments, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA).

Laser light scattering.

Laser light scattering (LLS) was performed as previously described with slight modifications (38, 40, 47). Briefly, tau (4 μM) was resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 16 μM heparin, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1% NaN3, and the amount of scattered light was assessed. The degree of light scattering was monitored (room temperature, 400 minutes) in a Fluorometer Micro Cell (3 mm; Starna Cells Inc.) illuminated by a He-Ne laser (632 nm). Light scattering was recorded with a charged coupled device (CCD) digital video camera (PL-A641; PixeLINK, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) attached to a microscope objective (∞4) positioned at 90° to the direction of the incident laser beam. Resultant scatter signal intensities were subtracted from signal adjacent to the nonilluminated area (background subtraction). LLS recording software was written by W.E. van der Veer (UCI Chemistry Core Facility) using LabView (National Instruments, Austin, Texas, USA).

MC1 immunoprecipitation.

Full-length and caspase-3–cleaved recombinant tau was immunoprecipitated overnight (4°C) with mAb MC1 coupled to protein G (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.). Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot using a rabbit polyclonal anti-tau primary antibody (1:1,000; gift of L.I. Binder). Membranes were then incubated with HRP-linked anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000; Calbiochem) and detected with chromogen 4CN (PerkinElmer Inc., Massachusetts, USA).

In vitro phosphorylation assay.

Full-length or caspase-3–cleaved recombinant tau was purified using TALON metal affinity resin (BD Biosciences — Clontech, Palo Alto, California, USA) to remove active caspase-3 prior to in vitro phosphorylation assays. All reactions were carried out at 37°C in 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 2 mM ATP. Fresh ATP was added immediately before GSK-3β (Calbiochem). Aliquots were removed at various time points, and reactions were stopped by the addition of sample buffer, boiled at 100°C (10 minutes), and analyzed by Western blot.

Aβtreatment of rat cortical neurons.

Primary cortical neurons (E18) were plated on poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips (1.5 ∞ 105 cells per coverslip). After 7 days in culture, cells were treated with 25 μM fibrillar Aβ1–42 (Biosource International Inc.) for 1, 4, 6, or 24 hours. Fibrillar Aβ1–42 was prepared by freeze-thawing (three times) followed by incubation at room temperature overnight. Following treatment, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for immunocytochemistry as described above. The number of ΔTau, MAP-2, and ΔTau cells with DNA fragmentation (DAPI) within a defined counting frame (500 μm2) were quantified with a ∞20 objective under epifluorescence illumination by a blinded observer. Four randomly chosen regions were counted from two coverslips per treatment. Data were analyzed using ANOVA for a split-plot design followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using StatView 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH/National Institute on Aging grants AG000096 (to R.A. Rissman, W.W. Poon, and M. Blurton-Jones), AG023433 (to R.A. Rissman), AG000538 and P50 AG016573 (to C.W. Cotman), AG17968 (to F.M. LaFerla), AG19386 (to T.T. Rohn), and AG19780 (to M.P. Vitek). We thank P.A. Adlard, E. Head, and D.H. Cribbs (Institute for Brain Aging and Dementia, UCI) for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to J.P. Kesslak and W.E. van der Veer (Department of Chemistry, UCI) for statistical advice and LLS assistance, respectively. We would also like to thank Matthew D.E. Loper for his invaluable contributions.

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 23.

Robert A. Rissman, Wayne W. Poon, and Mathew Blurton-Jones contributed equally to this work.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: Alzheimer disease (AD); amyloid β (Aβ); glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β); laser light scattering (LLS); mild cognitive impairment (MCI); Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); neurofibrillary tangle (NFT); paired helical filament (PHF); radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA); reassembly buffer (RAB); traumatic brain injury (TBI); triple-transgenic mouse model (3xTg-AD).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Caceres A, Kosik KS. Inhibition of neurite polarity by tau antisense oligonucleotides in primary cerebellar neurons. Nature. 1990;343:461–463. doi: 10.1038/343461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebneth A, et al. Overexpression of tau protein inhibits kinesin-dependent trafficking of vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:777–794. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:1051–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wischik CM, et al. Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:4884–4888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997;48:128–132. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970415)48:2<128::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jicha GA, Berenfeld B, Davies P. Sequence requirements for formation of conformational variants of tau similar to those found in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;55:713–723. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990315)55:6<713::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uboga NV, Price JL. Formation of diffuse and fibrillar tangles in aging and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goedert M, et al. The abnormal phosphorylation of tau protein at Ser-202 in Alzheimer disease recapitulates phosphorylation during development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5066–5070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg SG, Davies P, Schein JD, Binder LI. Hydrofluoric acid-treated tau PHF proteins display the same biochemical properties as normal tau. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:1141–1154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biernat J, Gustke N, Drewes G, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: distinction between PHF-like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;11:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramblett GT, et al. Abnormal tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in Alzheimer’s disease recapitulates development and contributes to reduced microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;10:1089–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gervais FG, et al. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta precursor protein and amyloidogenic A beta peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stadelmann C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 in single neurons and autophagic granules of granulovacuolar degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence for apoptotic cell death. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohn TT, Head E, Nesse WH, Cotman CW, Cribbs DH. Activation of caspase-8 in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8:1006–1016. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohn TT, et al. Correlation between caspase activation and neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:189–198. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su JH, Zhao M, Anderson AJ, Srinivasan A, Cotman CW. Activated caspase-3 expression in Alzheimer’s and aged control brain: correlation with Alzheimer pathology. Brain Res. 2001;898:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohn TT, et al. Caspase-9 activation and caspase cleavage of tau in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;11:341–354. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gastard MC, Troncoso JC, Koliatsos VE. Caspase activation in the limbic cortex of subjects with early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:393–398. doi: 10.1002/ana.10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin SJ, et al. Proteolysis of fodrin (non-erythroid spectrin) during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:6425–6428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canu N, et al. Tau cleavage and dephosphorylation in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7061–7074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07061.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang F, et al. Antibody to caspase-cleaved actin detects apoptosis in differentiated neuroblastoma and plaque-associated neurons and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:379–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fasulo L, et al. The neuronal microtubule-associated protein tau is a substrate for caspase-3 and an effector of apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:624–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung CW, et al. Proapoptotic effects of tau cleavage product generated by caspase-3. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8:162–172. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JC, et al. DEDD regulates degradation of intermediate filaments during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:1051–1066. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utsumi T, Sakurai N, Nakano K, Ishisaka R. C-terminal 15 kDa fragment of cytoskeletal actin is posttranslationally N-myristoylated upon caspase-mediated cleavage and targeted to mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2003;539:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamblin TC, et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmel G, Mager EM, Binder LI, Kuret J. The structural basis of monoclonal antibody Alz50’s selectivity for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32789–32795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosik KS, et al. Epitopes that span the tau molecule are shared with paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knoblach SM, et al. Multiple caspases are activated after traumatic brain injury: evidence for involvement in functional outcome. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1155–1170. doi: 10.1089/08977150260337967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamblin TC, King ME, Kuret J, Berry RW, Binder LI. Oxidative regulation of fatty acid-induced tau polymerization. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14203–14210. doi: 10.1021/bi001876l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barghorn S, Mandelkow E. Toward a unified scheme for the aggregation of tau into Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14885–14896. doi: 10.1021/bi026469j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedhoff P, von Bergen M, Mandelkow EM, Davies P, Mandelkow E. A nucleated assembly mechanism of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:15712–15717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovestone S, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-like phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3 in transfected mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loo DT, et al. Apoptosis is induced by beta-amyloid in cultured central nervous system neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivins KJ, Ivins JK, Sharp JP, Cotman CW. Multiple pathways of apoptosis in PC12 cells. CrmA inhibits apoptosis induced by beta-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2107–2112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivins KJ, Thornton PL, Rohn TT, Cotman CW. Neuronal apoptosis induced by beta-amyloid is mediated by caspase-8. Neurobiol. Dis. 1999;6:440–449. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oddo S, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berry RW, et al. Inhibition of tau polymerization by its carboxy-terminal caspase cleavage fragment. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8325–8331. doi: 10.1021/bi027348m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abraha A, et al. C-terminal inhibition of tau assembly in vitro and in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:3737–3745. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novak M, Kabat J, Wischik CM. Molecular characterization of the minimal protease resistant tau unit of the Alzheimer’s disease paired helical filament. EMBO J. 1993;12:365–370. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alonso A, Zaidi T, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation induces self-assembly of tau into tangles of paired helical filaments/straight filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:6923–6928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121119298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kraemer BC, et al. Neurodegeneration and defective neurotransmission in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:9980–9985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533448100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis J, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293:1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson GR, et al. Human wild-type tau interacts with wingless pathway components and produces neurofibrillary pathology in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;34:509–519. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andorfer C, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mookherjee P, Johnson GV. Tau phosphorylation during apoptosis of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2001;921:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, et al. Staging of cytoskeletal and beta-amyloid changes in human isocortex reveals biphasic synaptic protein response during progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;157:623–636. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gouras GK, et al. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Tseng BP, LaFerla FM. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rapoport M, Dawson HN, Binder LI, Vitek MP, Ferreira A. Tau is essential to beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sponne I, et al. Apoptotic neuronal cell death induced by the non-fibrillar amyloid-beta peptide proceeds through an early reactive oxygen species-dependent cytoskeleton perturbation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3437–3445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Busciglio J, et al. Altered metabolism of the amyloid beta precursor protein is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in Down’s syndrome. Neuron. 2002;33:677–688. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi RH, et al. Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wirths O, et al. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation precedes plaque formation in beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;306:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKee AC, Kosik KS, Kowall NW. Neuritic pathology and dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1991;30:156–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cummings BJ, Pike CJ, Shankle R, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid deposition and other measures of neuropathology predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1996;17:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grober E, et al. Memory and mental status correlates of modified Braak staging. Neurobiol. Aging. 1999;20:573–579. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mattson MP, Keller JN, Begley JG. Evidence for synaptic apoptosis. Exp. Neurol. 1998;153:35–48. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mattson MP, Partin J, Begley JG. Amyloid beta-peptide induces apoptosis-related events in synapses and dendrites. Brain Res. 1998;807:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McLaughlin B, et al. Caspase 3 activation is essential for neuroprotection in preconditioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0232966100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McLaughlin B. The kinder side of killer proteases: caspase activation contributes to neuroprotection and CNS remodeling. Apoptosis. 2004;9:111–121. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000018793.10779.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung CW, et al. Atypical role of proximal caspase-8 in truncated Tau-indued neurite regression and neuron cell death. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003;14:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y, McLaughlin R, Goodyer C, LeBlanc A. Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid beta peptide1-42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:519–529. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rohn TT, Rissman RA, Head E, Cotman CW. Caspase activation in the Alzheimer’s disease brain: tortuous and torturous. Drug News Perspect. 2002;15:549–557. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2002.15.9.740233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferrari A, Hoerndli F, Baechi T, Nitsch RM, Gotz J. beta-Amyloid induces paired helical filament-like tau filaments in tissue culture. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40162–40168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ackmann M, Wiech H, Mandelkow E. Nonsaturable binding indicates clustering of tau on the microtubule surface in a paired helical filament-like conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:30335–30343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dawson HN, et al. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1179–1187. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lynch JR, et al. Apolipoprotein E affects the central nervous system response to injury and the development of cerebral edema. Ann. Neurol. 2002;51:113–117. doi: 10.1002/ana.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petersen RC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Higuchi M, et al. Transgenic mouse model of tauopathies with glial pathology and nervous system degeneration. Neuron. 2002;35:433–446. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Torp R, et al. Ultrastructural evidence of fibrillar beta-amyloid associated with neuronal membranes in behaviorally characterized aged dog brains. Neuroscience. 2000;96:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.