Abstract

Background

An Internet safety decision aid was developed to help abused women understand their risk for repeat and near-lethal intimate partner violence, clarify priorities related to safety, and develop an action plan customized to these priorities.

Purpose

The overall purpose of this study was to test the effectiveness of a safety decision aid compared with usual safety planning (control) delivered through a secure website, using a multi-state randomized controlled trial design. The paper evaluated the effectiveness of the safety decision aid in reducing decisional conflict after a single use by abused women.

Design

Randomized controlled trial referred to as IRIS, Internet Resource for Intervention and Safety

Participants

Abused women who spoke English (N = 708) were enrolled in a four-state, randomized controlled trial.

Intervention and Control

The intervention was an interactive safety decision aid with personalized safety plan; the control condition was usual safety planning resources. Both were delivered to participants through the secure study website.

Main Outcome Measures

This paper compared women’s decisional conflict about safety: total decisional conflict and the four subscales of this measure (feeling: uninformed, uncertain, unclear about safety priorities; and sensing lack of support) between intervention/control conditions. Data were collected 3/2011–5/2013 and analyzed 1/2014–3/2014.

Results

Immediately following the first use of the interactive safety decision aid, intervention women had significantly lower total decisional conflict than control women, controlling for baseline value of decisional conflict (p=0.002, effect size=.12). After controlling for baseline values, the safety decision aid group had significantly greater reduction in feeling uncertain (p=0.006, effect size=.07), and in feeling unsupported (p=0.008, effect size=.07) about safety than the usual safety planning group.

Conclusions

Abused women randomized to the safety decision aid reported less decisional conflict about their safety in the abusive intimate relationship after one use compared to women randomized to the usual safety planning condition.

Keywords: decision aid, intimate partner violence, decisional conflict, computer-assisted decision making, safety, risk assessment

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a widespread and serious public health problem, with at least 6.9 million U.S. women raped, physically hit and/or stalked by a partner/ex-partner yearly.1 Nearly half of abused women report injury;1 well-documented sequelae of IPV including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, suicidality, chronic fatigue, difficulty sleeping, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, breathing problems, traumatic brain injury and gynecological problems.2–5 IPV is the most significant risk factor for intimate partner homicide; on average, more than three U.S. women are murdered every day by a partner/ex-partner.6–8

Abused women face complex, dangerous, and difficult safety decisions.9, 10 The cornerstone for IPV interventions is safety planning, a dialogic process supporting abused women’s decision-making. Safety planning ideally is individualized, attending to women’s priorities for safety decisions, plans (e.g., leaving or remaining in the relationship), available resources, and the dangerousness of the relationship (likelihood of severe and/or lethal violence) using evidence-based risk assessment.10 Safety planning is typically accessed through formal services, i.e., crisis services, advocacy (in health, social service and legal settings), support groups, and individual counseling.11 However, abused women are often unaware of IPV resources, how to find them, or what services they offer,12 and the majority do not access formal services, representing missed opportunities to reduce exposure to IPV and its negative health consequences.13–15

High-quality evidence suggests clinical decision aids effectively support patients’ informed decision-making regarding treatment options in varied situations (e.g., management of chronic conditions, end-of-life choices).16 Decision aids, which complement (not replace) professional services, provide information and help patients clarify personal values.17 Decision aids reduce decisional conflict, which stems from feeling uninformed/unclear about personal priorities (or values) around a decision.16 Therefore, the team developed the first-ever safety decision aid (SDA) for IPV survivors, based on existing violence prevention and decisional conflict research. The SDA is individualized, helping abused women assess danger, set safety priorities and plan for safety.18 IPV survivors in shelters (N=90) who tested the SDA via laptop had significantly reduced decisional conflict after just one use.18

Although abused women are commonly isolated by their partners, many have safe Internet access and actively search online for IPV help and information.19 Therefore, the SDA was adapted to be deployed via a secure study website. The ongoing randomized controlled trial, referred to as IRIS (Internet Resource for Intervention and Safety), is testing the effectiveness of the SDA compared with usual safety planning (i.e., IPV information typically available online) on abused women’s health and safety. This paper presents findings from testing the hypothesis that women who accessed the interactive SDA would have significantly less decisional conflict about safety after a single use than those provided usual safety planning information online. The paper also examines whether women’s priorities for safety decisions are related to relationship intentions (remaining in or ending the relationship).

Method

Trial Design: Four academic centers conducted this parallel RCT with a one-to-one allocation ratio (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier #NCT01312103). The protocol was consistent across sites and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Johns Hopkins University, Oregon Health & Science University, Arizona State University, and University of Missouri.

Study Setting, Participants and Recruitment

Women were recruited from four racially/ethnically diverse US States (Arizona, Maryland, Missouri, Oregon). Inclusion criteria were: 1) English speaking; 2) adult (≥18 years); 3) female, 4) currently (within past 6 months) experiencing physical violence, sexual violence, emotional abuse and/or threats of physical/sexual violence by a current-male or female intimate partner; and 5) resident of a participating state. Additionally, eligible women: 1) reported safe access to and comfort with using a computer with Internet access; and 2) had or created a safe email address (safe computer/email being one an abusive partner did not have access to). Recruitment efforts were focused on reaching women in the general community rather than through formal IPV services, and reaching women currently being abused. Additionally, as computer access was required, most recruitment strategies were web based, including online classified ads (e.g., Craigslist), postings on social media (e.g. Facebook ads), online newspaper ads, community listservs, and university research listings. Additionally flyers were posted in community-based locations (e.g., health clinics, university campuses, cafes, women’s bathrooms in bars, libraries, programs serving women/children). Recruitment materials provided an email and toll-free study number for the study. For safety, recruitment materials referred to a “woman’s health and safety study” rather than referring to IPV or domestic violence. No participants were turned away if they met eligibility requirements. Participants were followed for 12 months from baseline.

Sample Size and Randomization

Sample size was based on the primary outcome of the trial, increasing safety-seeking behaviors, using a medium effect size of 0.58 calculated from a previous IPV intervention.20, 21 Assuming up to 20% attrition, the desired sample size was 720 (360/group, 180 women per site). This sample size was expected to be sufficient for measuring immediate change in decisional conflict based on prior work.18

Computerized blocked randomization was created, with stratification within each state and for whether the participant had children (˂18 years) living with her, ensuring the proportion of women in each state assigned to each group remained relatively balanced. The study programmer (who had no participant contact) programmed the randomization sequence, which was concealed from the research assistants (RAs), into a secure study tracking database. Participants were blinded to group assignment.

Ethical and Safety Considerations

RAs received standardized training before recruitment, including study protocols for: IPV advocacy training including safety assessment, safe use of computers, internet, smartphones, IPV resource referrals, and suicidality protocols. A telephone safety protocol was developed from previous research in the event that a woman indicated immediate danger from the partner.18 At the time of screening, RAs conducted a verbal informed consent process via telephone. Each participant was provided written consent information when logging into the study website, and were required to indicate consent prior to proceeding.

Procedures

RAs screened potential participants, who contacted them via email or phone. Following informed consent, RAs entered participants’ safe contact information into a tracking database, separate from the study website. The database automatically randomized women to intervention/control groups, and immediately sent the study website URL, assigned study ID/password, RA contact information, and guidance on computer and internet safety to the participant’s safe email address.

Participants logged into the secure study website to complete study-related activities when convenient and safe. The website also provided strategies for safety during and after the session. Data were entered by participants, eliminating error due to misread hand-written forms/data input.22, 23

Participants were encouraged to log in and complete study activities on the day of enrollment. Women who did not complete within three days received an automated reminder email. The RA checked in with women who did not complete by day 7, using their safe contact information, to assess whether she received the password, had problems with the website, or had questions. The RA continued to follow-up with participants until study activities were completed, they declined to participate, or the 6-week enrollment window expired.

Intervention: The Safety Decision Aid

The SDA has three main components: 1) safety priority-setting activity with feedback; 2) Danger Assessment with feedback; and 3) safety planning strategies and resource information tailored to a woman’s responses to the first two components, considering her previous use of protective strategies.18, 24 The development of the SDA is described previously.18 National experts, advocates and survivors provided feedback on content and face validity as the SDA was developed.18

Priority-Setting Activity

In designing the priority-setting activity, several decision-making theories derived from descriptive analyses about how people acquire and make use of information to make difficult decisions were reviewed.25 These theories are derived from descriptive analyses about how people acquire and make use of information to make difficult decisions.25 The SDA drew heavily from decisional conflict theory,25 which recognizes the competing gains and losses to self/significant others when considering safety options. To address this underlying conflict, intervention group women set priorities among important drivers of abused women’s safety decisions, identified through literature review and validated with IPV advocates, survivors, and researchers.18 These are:

Having resources: employment, housing, health insurance, legal advice, and safe childcare;

Keeping my privacy: keeping relationship issues private from family, friends, work, and/or others;

My feelings for my partner: feelings of love and concern for partner;

My concern for safety: physical, emotional and spiritual safety;

My child’s well-being (for those with children living in the home): concern for children’s custody and physical, emotional, spiritual safety and well-being.

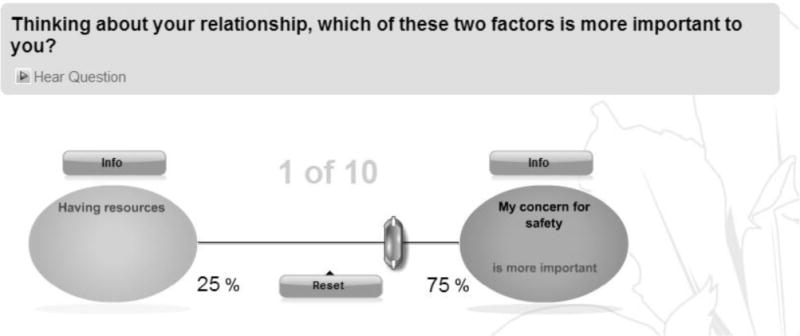

Each participant compared pairs of factors for relative importance to her via sliding bar, described previously.18 For example, a woman might compare importance of, “Having resources” against “My concern for safety”. In Figure 1, the sliding bar is pushed toward “My concern for safety” (75%), suggesting this factor is three times more important than having resources (home, insurance, etc.), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screen shot of priority setting activity.

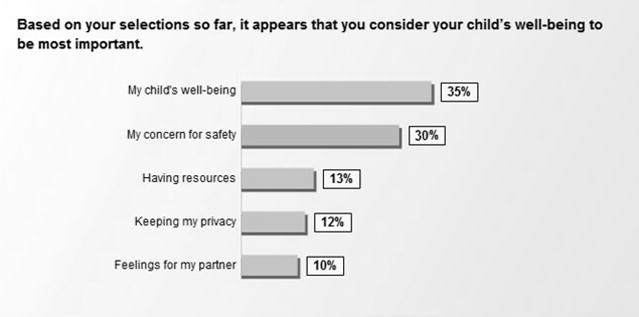

Each participant made similar pairwise comparisons among all factors. Behind the user interface, each pairwise comparison was entered in a matrix that was used to compute priority weights for each factor, described previously.26 At the end of the priority setting activity, each woman received feedback about her safety priorities (the computed weights, see Figure 2), and could make changes to priorities if desired. Weights assigned by the women for each factor could vary between 0 and 100, and summed to 100.

Figure 2.

Feedback on safety priority weights.

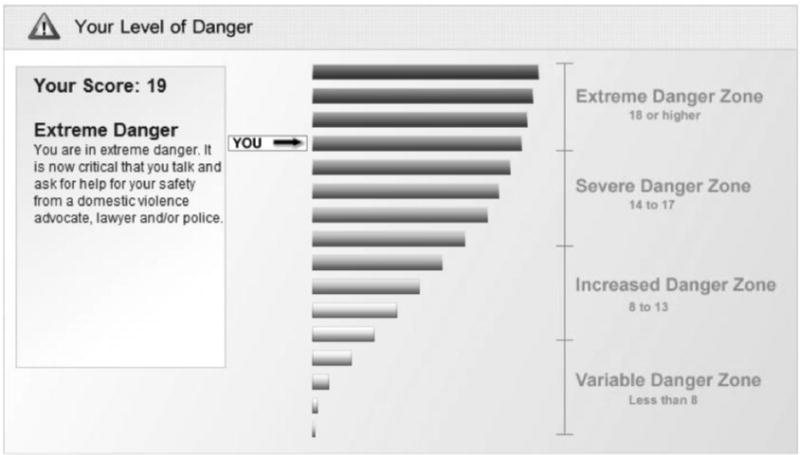

The Danger Assessment

To help women understand their risk for severe repeat, near-lethal or lethal violence they completed either the Danger Assessment (DA) or the DA-Revised (DA-R; if abused by a female partner). Both include questions to assess the severity and frequency of violence, whether violence was increasing, extreme controlling behavior, extreme jealousy, threats to kill, forced sex and other risk factors associated with lethality or near lethality in abusive relationships.6, 10, 27, 28 A weighted scoring algorithm provided an instant score (DA range 0–38; DA-R 0–26), along with a level of danger (e.g., “variable danger” to “extreme danger”), shown graphically to the user (see Figure 3), with validated messages about the level of danger and safety.6, 8, 10, 28, 29, 30 A similar graphic of DA results used in a prior study was shown to be memorable to abused women and to help them understand their level of danger.31

Figure 3.

Feedback from danger assessment

Participants completed the priority setting activity before completing the DA/DA-R. After seeing their DA/DA-R score, they had the option to reset their priorities. For example, if her danger level was higher than she expected, she might want to make changes in her safety priorities. The SDA tracked all changes to evaluate how the DA/DA-R feedback was utilized in the prioritization process.

Safety Plan

Finally, the SDA provided a personalized safety action plan, written at an average reading level of 7th grade for accessibility. This provided recommended strategies for the participant and her children (as appropriate) based on her input (demographics, relationship characteristics, previous protective actions, safety priorities and DA/DA-R score). This plan included websites and phone numbers for national, state and local resources, with local resources linked to her county of residence. Participants were also provided with multiple safety strategies to choose from that included information and links to domestic violence services, legal services, affordable housing, employment and education information, drug and alcohol treatment, child custody resources, child health, batterer intervention programs, and/or health and welfare services. Each participant had the option to print a copy of her DA/DA-R feedback, safety priority feedback, and her individualized safety plan or could access it anytime online using her password-protected login.

Control Group: Usual Safety Planning

When control group women logged in to their secure site, they received safety planning resources like those usually provided by DV advocates, through national or local domestic violence hotlines or websites. They were not provided with immediate and visual feedback to their DA/DA-R score, and did not complete the safety priority setting activity. All control group women received the same emergency safety plan, modeled from national and state IPV online resources, and could access the plan online through the study website using her password-protected login anytime.

Measures

Demographics and other measures were collected through the study website, including:

Decisional Conflict

Questions from the low-literacy version of the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS)32 were adapted to measure the effect of the SDA compared to usual safety planning on the participants’ overall conflict about their safety decisions. This scale measures the constructs underlying overall decisional conflict, with four subscales: feeling uncertain, uninformed, unclear about priorities or values, and unsupported) (see Table 1).16 The DCS discriminates between people who make decisions and those who delay them, and has demonstrated psychometric soundness (Cronbach α=0.86).32 The DCS was administered to both groups at baseline (pre) and end of the first use of the SDA/ usual safety planning websites (post). Questions were scored as “Yes”= 0, “Unsure”= 2 and “No”=4. The mean DCS score was multiplied by 25 to create an overall conflict score, ranging from 0 (no decisional conflict) to 100 (extremely high decisional conflict).32

Table 1.

Decisional Conflict Questions

| Decisional Conflict Questions (Yes, No, Unsure) | Subscale |

|---|---|

| 1. Do you know your options for keeping yourself (and your children) safe? | Uninformed |

| 2. Do you know the benefits of (or reasons for) remaining in the relationship? | Uninformed |

| 3. Do you know the benefits of (or reasons for) ending the relationship? | Uninformed |

| 4. Do you know the risks of (or reasons for) remaining in the relationship? | Uninformed |

| 5. Do you know the risks of (or reasons for) ending the relationship? | Uninformed |

| 6. Are you clear about what benefits matter most to you? | Unclear valuesa |

| 7. Are you clear about which risks are most important to you to avoid? | Unclear valuesa |

| 8. Do you have enough support from others to make a decision about your safety? | Lack of support |

| 9. Do you have enough advice to make a decision about your safety? | Lack of support |

| 10. Can you make a decision about your safety without pressure from others? | Lack of support |

| 11. Are you clear about the best option for your safety? | Uncertainty |

| 12. Do you feel sure about the best choice for your safety? | Uncertainty |

Also referred to as safety priorities

Danger Assessment

The DA and DA-R scores described above were also recorded as a study variable.

Priority Weights

For intervention group women, priority weights were recorded for each factor after the completion of the SDA.26

Relationship Intention

Relationship intention was measured with one item, asked pre and post: “What plans do you have for the future of your relationship?” Response options included end relationship (coded 0), remain in relationship (coded 1), or unsure (coded 2).

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 22.0. Baseline data were initially analyzed with chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent samples t-tests for continuous variables using. Baseline demographics were compared to ensure randomization effectively delivered similar groups. The planned analysis used an intent-to-treat approach, however all women remained in their originally assigned group. Multiple regression was used to test the effect of the SDA vs. usual safety planning on change in decisional conflict from pre- to post, controlling for pre-test decisional conflict score and length of relationship. A Bonferroni correction was used to account for the multiple decisional conflict subscales, setting α = .013 for these analyses. Analyses of variance were used to explore whether priority weights differed for intervention group women who intended to end the relationship, stay in the relationship, and women who were unsure about their intentions. These analyses were conducted separately for participants with and without children.

Results

Participants

Although the SDA and usual safety planning website was available in Spanish, this analysis excludes 12 women who completed in a Spanish version, as sample size was insufficient to determine psychometric equivalence of English/Spanish versions. Of women who contacted the RA and were screened for eligibility, 182 (17.6%) did not meet eligibility requirements (e.g., no longer in a relationship with an abusive partner, did not reside in a study state, no safe access to a computer with internet). Eligibility was confirmed for 850 women, 826 (97.2%) of whom completed informed consent and were randomized (409 intervention group, 417 control). Baseline data collection was completed by 87% of intervention women and 85% of control women Figure 4. Data on age and children were collected at consent; those who consented and were randomized but did not complete baseline data collection (N=118) were slightly older (37.19 vs. 33.34) than women who did (N=708), but did not differ in the percent who had children (42.37% versus 42.83%). In total, 708 women participated (179 from Maryland, 177 Oregon, 173 Arizona, 179 Missouri) between 3/2011–5/2013. Data were analyzed between 1/2014–3/2014. No adverse events were reported during data collection.

Figure 4.

Participant flow

Table 2 displays participant demographics. Less than half (44.13%) were employed. The majority were White (63.42%), followed by Black (25.22%), and multi-racial (5.16%); 9.77% were Hispanic/Latina but used the English version of the SDA. Abusers were described as their boyfriend/girlfriend (53.90%), husband (17.87%), or ex-boyfriend/girlfriend (12.06%); 88.94% of abusive partners were male. The average DA score fell into the severe danger category with means of 14.36 (SD=7.73) and 15.85 (SD=4.77) for participants with a male and female partner, respectively. Over half (57.49%) currently lived with their abuser. Less than half (42.86%) had children younger than 18 at home. The only significant difference between intervention and control groups was that intervention participants were in the relationship longer (6.08 years, SD=6.64, vs. 4.84 years, SD=4.54). Length of relationship was used as a covariate in all analyses testing the intervention effect.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics by Intervention Group*

| Total | Control | Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | N | p | ||||

| M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | |||||

| Age | 706 | 33.34(10.63) | 352 | 33.50(10.79) | 354 | 33.17(10.48) | .682 |

| Length of relationship (years) | 705 | 5.46(5.72) | 351 | 4.84(4.54) | 354 | 6.08(6.64) | .004 |

| Danger assessment (z-score) | 705 | .00(1.00) | 352 | −0.05(1.00) | 353 | 0.05(0.99) | .201 |

| Danger assessment (raw scores) | |||||||

| Male partner | 627 | 14.36(7.73) | 317 | 13.94(7.73) | 310 | 14.67(7.71) | .173 |

| Female partner | 78 | 15.85(4.77) | 35 | 15.87(5.03) | 43 | 15.83(4.60) | .967 |

| N | % | N | N | p | |||

| Race | 678 | 335 | 343 | .678 | |||

| White | 63.42 | 65.97 | 60.93 | ||||

| Black | 25.22 | 22.39 | 27.99 | ||||

| Asian | 3.54 | 3.28 | 3.79 | ||||

| Native American | 1.62 | 1.49 | 1.75 | ||||

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.29 | ||||

| Other | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.87 | ||||

| Multi-racial | 5.16 | 5.97 | 4.37 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latina | 706 | 352 | 354 | .510 | |||

| No | 90.23 | 89.49 | 90.96 | ||||

| Yes | 9.77 | 10.51 | 9.04 | ||||

| Relationship | 705 | 351 | 354 | .835 | |||

| Husband/Wife | 17.87 | 16.52 | 19.21 | ||||

| Ex-husband/ex-wife | 2.55 | 2.28 | 2.82 | ||||

| Separated/Estranged spouse | 4.11 | 4.27 | 3.95 | ||||

| Boyfriend/Girlfriend | 53.90 | 56.98 | 50.85 | ||||

| Ex-boyfriend/ex-girlfriend | 12.06 | 10.83 | 13.28 | ||||

| Common law ex | 4.54 | 4.27 | 4.80 | ||||

| Common law | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.56 | ||||

| Other | 4.26 | 3.99 | 4.52 | ||||

| Partner’s gender | 705 | 352 | 353 | .344 | |||

| Female | 11.06 | 9.94 | 12.18 | ||||

| Male | 88.94 | 90.06 | 87.82 | ||||

| Live with partner | 701 | 349 | 352 | .802 | |||

| No | 42.51 | 42.98 | 42.05 | ||||

| Yes | 57.49 | 57.02 | 57.95 | ||||

| Live with children under 18 | 707 | 353 | 354 | .728 | |||

| No | 57.14 | 57.79 | 56.50 | ||||

| Yes | 42.86 | 42.21 | 43.50 | ||||

| Employed | 707 | 353 | 354 | .102 | |||

| No | 55.87 | 58.92 | 52.82 | ||||

| Yes | 44.13 | 41.08 | 47.18 | ||||

| Education | 703 | 350 | 353 | .641 | |||

| No high school diploma | 4.98 | 4.57 | 5.38 | ||||

| Diploma or GED | 14.94 | 16.00 | 13.88 | ||||

| Some college | 40.97 | 41.14 | 40.79 | ||||

| Associate’s degree | 14.65 | 15.14 | 14.16 | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 17.78 | 18.00 | 17.56 | ||||

| Graduate degree | 6.69 | 5.14 | 8.22 | ||||

Statistical significance (p≤0.05) is noted with a bolded p.

Reduction in Decisional Conflict

Intervention group women had a greater reduction in total decisional conflict than control participants (β=−.10, p=.002, Table 3; effect size=.12, Table 4) after controlling for baseline scores. Compared to the control group, intervention participants also had a greater reduction in uncertainty (β=−.08, p=.006; effect size=.07), and lack of support (β=−.03, p=.008; effect size=.07). Lack of values clarity (β=−.07, p=.014; effect size=.09) was not significant using the conservative Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .013. There was no statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups on changes in feeling uninformed. In conservative sensitivity analyses including all women and replacing missing post-test scores with baseline scores the results were unchanged, with the exception of support which had a higher p-value (total decision conflict p=.003; uncertainty, p=.007; support p=.092, values clarity p=.014). Although the improvement was significantly greater in the intervention group, in general, decisional conflict scores improved between pre and post-testing for both groups. At pretest, both groups were consistent in where they had the most and least decisional conflict (Table 4): feeling unsupported was the highest (42.78 control, 38.02 intervention), and feeling uninformed was lowest (18.95 control, 19.79 intervention).

Table 3.

Regressions examining the effect of the intervention on change in decisional conflict*

| Decisional conflict: total (N=700) |

Decisional conflict: uninformed (N=701) |

Decisional conflict: uncertainty (N=699) |

Decisional conflict: unclear values (N=697) |

Decisional conflict: Unsupported (N=687) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Length of relationship | .02 | .515 | .03 | .368 | .04 | .202 | −.01 | .622 | .01 | .569 |

| Pre-test score | −.54 | <.001 | −.56 | <.001 | −.67 | <.001 | −.64 | <.001 | −.96 | <.001 |

| Intervention | −.10 | .002 | −.03 | .305 | −.08 | .006 | −.07 | .014 | −.03 | .008 |

Note: β is the standardized regression coefficient. Statistical significance (p≤0.01) is noted with a bolded p. These analyses controlled for pre-test score and length of relationship.

Table 4.

Means for the Decisional Conflict Scales at Pre-test and Post-test by Intervention Groupa

| Pre-test | Post-test | Effect Size d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | ||

| M (95% CI) | M (95% CI) | M (95% CI) | M (95% CI) | ||

| Decisional conflict: Total | 30.07 (28.02–32.11) |

28.36 (26.44–30.28) |

18.87 (17.01–20.74) |

14.88 (13.16–16.59) |

.12 |

| Decisional conflict: Uninformed | 18.95 (17.08–20.82) |

19.79 (18.04–21.55) |

11.89 (10.18–13.60) |

11.30 (9.64–12.96) |

.08 |

| Decisional conflict: Uncertainty | 38.89 (35.47–42.31) |

35.19 (31.68–38.69) |

22.08 (19.06–25.10) |

15.95 (13.30–18.61) |

.07 |

| Decisional conflict: Unclear values | 30.30 (27.08–33.52) |

27.85 (24.74–30.96) |

19.27 (16.45–22.09) |

14.03 (11.59–16.47) |

.09 |

| Decisional conflict: Unsupported | 42.78 (39.25–46.31) |

38.02 (34.63–41.41) |

9.43 (8.34–10.53) |

6.99 (6.01–7.97) |

.07 |

Scores range from 0–100, with higher score meaning more decisional conflict.

Priorities for Safety

All intervention-group women set priorities for safety, but women with children under age 18 living at home had one extra factor (child well-being) to prioritize. For those with children, protection of children’s well-being dominated safety priorities (Table 5), with this factor rated 3–4 times more important than other factors. For women without children, priority weights were split fairly evenly among all four safety factors.

Table 5.

Average Priority Weights for Safety Factors (Intervention Participants Only)a

| N | M (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| With Children: | ||

| Priority: My child’s wellbeing | 153 | 46.88(44.61–49.15) |

| Priority: Having resources | 153 | 16.47(15.10–17.84) |

| Priority: My concern for safety | 153 | 15.35(14.14–16.57) |

| Priority: Feelings for my partner | 153 | 10.82(9.51–12.12) |

| Priority: Keeping my privacy | 153 | 10.48(9.54–11.42) |

| Without Children: | ||

| Priority: My concern for safety | 200 | 26.98(25.20–28.75) |

| Priority: Having resources | 200 | 26.97(25.43–28.51) |

| Priority: Feelings for my partner | 200 | 24.18(22.34–26.01) |

| Priority: Keeping my privacy | 200 | 21.88(20.42–23.33) |

Scores for each priority range from 0–100, with higher scores reflecting higher priorities, and summing to 100 across all priorities.

Priority weights were examined to see if they related to a woman’s relationship intention (end current abusive relationship, remain in relationship, or unsure) measured at post-test (Table 6). The pattern was the same for women with and without children. Priority weights for Having resources, Keeping my privacy, and My child’s wellbeing did not significantly differ by relationship intention. Participants who planned to end the relationship placed lower priority on My feelings for my partner and greater priority on My concern for safety than those who were staying or unsure.

Table 6.

Differences in Priority weights for the Safety Factors by Intention for Relationship at Post-Test*

| With Children | Without Children | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention for Relationship | Intention for Relationship | |||||||

| End relationship M (95% CI) |

Remain in relationship M (95% CI) |

Unsure M (95% CI) |

p | End relationship M (95% CI) |

Remain in relationship M (95% CI) |

Unsure M (95% CI) |

p | |

| Priority: Having resources | 16.75 (15.01–18.49) |

14.95 (10.07–19.83) |

16.73 (14.31–19.16) |

.677 | 26.60 (24.39–28.81) |

25.59 (21.34–29.84) |

27.66 (25.20–30.11) |

.643 |

| Priority: Keeping my privacy | 9.63 (8.43–10.82) |

10.80 (7.54–14.06) |

11.45 (9.79–13.11) |

.208 | 22.16 (19.89–24.43) |

21.72 (16.49–26.96) |

21.70 (19.70–23.70) |

.956 |

| Priority: My child’s wellbeing | 47.94 (44.87–51.00) |

45.50 (38.85–52.16) |

46.00 (41.87–50.13) |

.677 | ||||

| Priority**: Feelings for my partner | 7.92a,b (6.36–9.48) |

16.00a (11.84–20.16) |

12.62b (10.42–14.82) |

<.001 | 20.11e,f (17.26–22.96) |

30.09e (24.79–35.38) |

25.67f (23.10–28.25) |

.001 |

| Priority**: My concern for safety | 17.76c,d (15.95–19.57) |

12.75c (9.29–16.21) |

13.20d (11.49–14.90) |

.001 | 31.12g,h (28.36–33.88) |

22.60g (16.74–28.45) |

24.97h (22.59–27.35) |

.001 |

Statistical significance (p≤0.05) is noted with a bolded p.

Means with the same lettered superscript (a–h) are statistically different from one another at the p<.05 level.

Discussion

Decisional conflict declined significantly for abused women after one use of the personalized internet-based SDA, with greater reduction in overall decisional conflict compared to the control group who accessed usual safety planning information online. These findings support the hypothesis that providing usual safety planning information (emergency safety plans, phone numbers and websites) is not as useful at reducing decisional conflict about safety as providing a personalized assessment of safety priorities, danger, relationship characteristics, and previous protective actions. Participants in both groups received safety information, so it is unsurprising that on average all women felt more informed immediately after using the SDA and control websites. The longitudinal trial, IRIS, is designed to examine change over time on decisional conflict about safety with repeat use of the SDA.

These findings are consistent with underlying decisional conflict theory used to create the SDA and contribute to the current IPV literature by describing how women process decisional conflict when setting safety priorities. One of the strengths of this study is that the intervention (providing an explicit priority-setting activity) was compared to standardized safety planning information widely available to the many abused women who search for information and help online. Intuitively, women weigh various risks and benefits as they plan for safety, knowing her decisions not only affect her safety but that of children, other family members, friends and co-workers, potentially creating decisional conflict about the risk and benefits of her actions.

Women with children at home prioritized the safety of their children over their own safety, having resources, feelings for partner, and privacy. For mothers, decisions to seek services, disclose abuse, remain in or leave a relationship are often based on balancing perceived risks and benefits to her children.33, 34 In this study, prioritizing children was not related to intention to leave the relationship, reflecting the complexity of decisions when children are involved. For mothers, leaving is not always perceived as the safest option for children; abusers may threaten to harm children or seek custody if she leaves or she may fear child protective services becoming involved if she discloses abuse when attempting to leave.33, 34 Additionally, women are often considering their ability to safely house and financially support children if they leave.35 By having women compare potentially competing priorities (e.g., having resources and protection of children), they acknowledge the conflict. They can then integrate this information into their thinking about using community resources, which may help resolve barriers to safety.

Women who intended to end their relationship had a lower priority related to feelings for partner and a stronger priority for safety. Safety planning is critically important when ending the relationship with an abuser, who may perceive he/she is losing control over their partner and may increase the severity of violence or controlling behavior to regain control. Leaving an abusive relationship is a well-known risk factor for intimate partner homicide and homicide-suicide.6, 36 Relationships are dynamic; abused women make daily decisions for safety. An online interactive SDA allows women 24/7 access to revise safety priorities, re-assess danger and receive a tailored safety plan based on new relationship realities, including plans to leave. Although control women also had access to their safety planning information 24/7, the safety strategies are standardized and do not vary based on individual input (e.g., a changing safety situation, priorities), likely limiting the usefulness as decisions for safety are being made over time.

Abused women must often make difficult decisions about their own safety and that of their loved ones, including children. As the majority of abused women do not access traditional DV services,13–15 they are often left to make these difficult decisions with little or no safety information specific to their situation. The SDA provides a private space for women to consider their priorities, understand their danger, safety plan, and learn about available resources. Reducing decisional conflict may promote engagement in safety planning which may, in turn, increase safety for abused women. Rather than supplant in-person DV services, this intervention compliments them by engaging women who are unaware of community resources or unready to access them. By providing personalized safety strategies including referral to services, the SDA may help women become violence free.

Limitations

Presenting pre-post data from one use of the SDA/control website assesses baseline pre-post decisional conflict for safety, but does not address patterns of change over time in decisional conflict. These immediate results do not yet provide evidence that reduced decisional conflict leads to enhanced safety. Given the longitudinal design of the trial, this will be addressed with future analyses.

Participants needed to have safe email and access to the Internet, likely excluding some abused women from participation. Most participants reported accessing the study website from home, while others reported access at the workplace, friend/family home, public library, and community-based organizations. This information is critical for two reasons: 1) it reduces the potential bias of requiring a safe computer with Internet access at home to participate; and 2) it demonstrates women do know how and where to safely access the Internet to obtain resources.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that just one session using an Internet-based safety decision aid was effective at reducing decisional conflict, thereby supporting the decision-making process of IPV survivors, with no adverse events. This represents an important and promising innovation to connect abused women – who most often do not access safety planning through formal services – with the tools they need to assess their level of danger, establish priorities, and develop a safety plan tailored to their needs.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH085641. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The research team would like to acknowledge the study participants for their time and expertise.

Karen B. Eden’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Nancy A. Perrin’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Ginger Hanson’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Jill T. Messing’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Tina Bloom’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Jacquelyn Campbell’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Andrea Gielen’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Amber Clough’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Jamie Barnes-Hoyt’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Nancy Glass’s work was supported by grant, R01MH085641, from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Clinical Trial Registration

The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01312103 on 3/9/2011. The study is funded by NIMH R01MH085641, Co-PIs, Eden K and Glass N, 2010–2015, with IRB approval on 2/15/11.

Footnotes

The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Contributor Information

Karen B. Eden, Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland Oregon.

Nancy A. Perrin, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Oregon.

Ginger C. Hanson, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Oregon.

Jill T. Messing, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona.

Tina L. Bloom, Sinclair School of Nursing at the University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, Missouri.

Jacquelyn C. Campbell, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland.

Andrea C. Gielen, Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

Amber S. Clough, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland.

Jamie S. Barnes-Hoyt, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland.

Nancy E. Glass, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black MC. Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: implications for clinicians. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011 Sep 1;5(5):428–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002 Apr 13;359(9314):1331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavanaugh C, Messing J, Del-Colle M, O’ Sullivan C, Campbell J. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among adult female victims of intimate partner violence. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(4):372–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, Zonderman AB. Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Sep;75(6):959–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA, et al. Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. Am J Public Health. 2003 Jul;93(7):1089–97. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JC, Glass N, Sharps PW, Laughon K, Bloom T. Intimate partner homicide: review and implications of research and policy. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007 Jul;8(3):246–69. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharps PW, Koziol-McLain J, Campbell J, McFarlane J, Sachs C, Xu X. Health care providers’ missed opportunities for preventing femicide. Prev Med. 2001 Nov;33(5):373–80. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JC, Sharps P, Glass NE. Risk Assessment for intimate partner homicide. In: Pinard GF, Pagani L, editors. Clinical assessment of dangerousness: empirical contributions. London: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell JC, Glass N. Safety planning, danger, and lethality assessment. In: Mitchell CE, editor. Intimate Partner Violence: A Health-Based Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macy RJ, Nurius PS, Kernic MA, Holt VL. Battered women’s profiles associated with service help-seeking efforts: illuminating opportunities for intervention. Soc Work Res. 2005;29(3):137–50. doi: 10.1093/swr/29.3.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westbrook L. Crisis information concerns: Information needs of domestic violence survivors. Inf Process Manag. 2009;45(1):98–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker AL, Derrick C, Lumpkin JL, Aldrich TE, Oldendick R. Help-seeking for intimate partner violence and forced sex in South Carolina. Am J Prev Med. 2000 Nov;19(4):316–20. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shannon L, Logan TK, Cole J. Help-seeking and coping strategies for intimate partner violence in rural and urban women. Violence Vict. 2006;21(2):167–81. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:Cd001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. 2013 [cited 2014 February 16]; Available from: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/

- 18.Glass N, Eden KB, Bloom T, Perrin N. Computerized aid improves safety decision process for survivors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2010 Nov;25(11):1947–64. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westbrook L. Understanding crisis information needs in context: The case of intimate partner violence survivors. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 2008;78(3):237–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Watson K, Batten E, Hall I, et al. Increasing the safety- promoting behaviors of abused women. Am J Nurs. 2004 Mar;104(3):40–50. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200403000-00019. quiz -1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Eribaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes SD, Bowie DA, Hergenrather KC. Collecting behavioural data using the world wide web: considerations for researchers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Jan;57(1):68–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AM, Copas AJ, Erens B, Mandalia S, Fenton K, Korovessis C, et al. Effect of computer-assisted self-interviews on reporting of sexual HIV risk behaviours in a general population sample: a methodological experiment. AIDS (London, England) 2001 Jan 5;15(1):111–5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell JC, Webster DW, Glass N. The danger assessment: validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. J Interpers Violence. 2009 Apr;24(4):653–74. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwyn G, Stiel M, Durand MA, Boivin J. The design of patient decision support interventions: addressing the theory-practice gap. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011 Aug;17(4):565–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eden KB, Dolan JG, Perrin NA, Kocaoglu D, Anderson N, Case J, et al. Patients were more consistent in randomized trial at prioritizing childbirth preferences using graphic- numeric than verbal formats. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Apr;62(4):415–24. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass N, Perrin N, Hanson G, Bloom T, Gardner E, Campbell JC. Risk for reassault in abusive female same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health. 2008 Jun;98(6):1021–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roehl J, O’Sullivan C, Webster DW, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence risk assessment validation study: The RAVE study Final Report to the. US Department of Justice; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolaidis C, Curry MA, Ulrich Y, Sharps P, McFarlane J, Campbell D, et al. Could we have known? A qualitative analysis of data from women who survived an attempted homicide by an intimate partner. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Oct;18(10):788–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell JC. Helping women understand their risk in situations of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2004 Dec;19(12):1464–77. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghanbarpour SA. Understanding factors that influence the practice of safety strategies by victims of intimate partner violence. Johns Hopkins University; 2011. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor A. User Manual-Decisional Conflict Scale (ten item question format) [document on the internet] Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 1993. updated 2010. Available from: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decisional_Conflict.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly UA. “I’m a mother first”: The influence of mothering in the decision-making processes of battered immigrant Latino women. Res Nurs Health. 2009 Jun;32(3):286–97. doi: 10.1002/nur.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irwin LG, Thorne S, Varcoe C. Strength in adversity: motherhood for women who have been battered. Can J Nurs Res. 2002 Dec;34(4):47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson DK, Saunders DG. Leaving an abusive partner: an empirical review of predictors, the process of leaving, and psychological well-being. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2003 Apr;4(2):163–91. doi: 10.1177/1524838002250769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koziol-McLain J, Webster D, McFarlane J, Block CR, Ulrich Y, Glass N, et al. Risk factors for femicide-suicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. Violence Vict. 2006 Feb;21(1):3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]